Submitted:

26 December 2025

Posted:

29 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. The Biogeochemistry of Methanogens

1.1. Introduction

1.2. Methanogenic Habitats

1.3. Physicochemical Boundaries of Methanogenesis

| Environmental condition | Extremophile type (and growth definition(s)) | Growth limits for Methanogens | Examples of species found within extreme |

Geologic relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 1)Hyperthermophile (>80oC) 2)Thermophile (60-80oC) 3)Psychrophile (<15oC) |

1 & 2) 122oC [2,34]. 3) -2.5oC [47]. |

1 & 2) Methanopyrus kandleri strain 116, Methanopyrus genus, Methanocaldococcus jannaschii, and Methanothermococcus thermolithotrophicus [34]. 3) Candidatus Methanoflorens stordalenmirensis (freeze/thawing environments) [33], Methanococcoides burtonii [47]. |

1) Hydrothermal vents (modern day [34], potential vents of Europa and Enceladus [13], Hot springs/geothermal springs [20]. 2) Archean Oceans [48]. 3) Permafrost and ice; modern day and during glaciation events, like at the last glacial maxima; deep sediments [33,49], Terrestrial surface of Mars [36], Oceans of Europa and Enceladus [10,46]. |

| Radiation | 1) Exposure to UV 2) Ionizing radiation |

1) 24 hours of 254 nm UV radiation [50]. | 1) Methanococcus maripaludis and Methanobacterium formicicum [50]. 2) Methanoscarcina spp. [50]. |

1) High UV radiation during the Archean [46]; surface of Mars [39]. 2) Ionizing radiation from Ur decay in nuclear geysers, possible location for the origin of life [51]. |

| Light | 1) Exposure to visible light (380-750 nm) | 1) Unknown limit; growth inhibition, particularly in the blue region of the spectrum (≈370–430 nm) [52]. Reduced sensitivity in association with photosynthetic bacteria [53]. |

1) Methanosarcina and Methanocella spp. (observed in soil) [53]; Methanosarcina barkeri in a cocultured biofilm with Synechocystis spp. strain PCC6803 [23]. | 1) Surface environments on Earth (from ancient to modern day). |

| Salinity | 1) Halophile (2-5M NaCl) | 1) Moderate/extreme halophiles growth 2-3M [16]. |

1) Methanosarcinales spp., Methanohalobium, Methanohalophilus and Methanosalsum spp., Methanonatronarchaeum thermophilum and Candidatus Methanohalarchaeum thermophilum [16,38]. | 1) Archean oceans; 1.5–2 times modern salinity [54]; Saline lakes [16]. |

| Pressure | 1) Survivability to low pressure 2) Barophile (obligate high pressure)/ Piezophile (adaptation to high pressure) |

1) Low pressure 6mbar – 143 mbar [37]. 2 & 3) 200 bar [34], 500 bar [38]. |

1) Methanothermobacter wolfeii, Methanosarcina barkeri, Methanobacterium formicicum, Methanococcus maripaludis [31,36,37]. 2) Methanopyrus kandleri strain 116, Methanopyrus genus, Methanocaldococcus jannaschii, and Methanothermococcus thermolithotrophicus [34,37]. |

1) Terrestrial surface of Mars [37]. 2) Hydrothermal vents (modern day [34], and possible location for the origin of life [55]; Deep Marine Sediments [56]. |

| pH | 1) Alkaliphile 2) Acidophile |

1) pH > 10.2 [3,35]. 2) pH < 3 [3]. |

1) Methanohalobium, Methanohalophilus and Methanosalsum [35]. | 1) Soda lakes [35]. |

| Hydrogen concentration | 1) High pH2 2) Low pH2 3) Fluctuations in H2 concentration |

1) > 6x10-2 bar [57]*. 2 & 3) As low as 0.1 Pa pH2 [58]; fluctuating H2 (from low pH2 to overpressure) [14]. |

1) Species name unknown. Plausibly, early hydrogenotrophs. 2 & 3) Methanobacterium bryantii, Methanoculleus bourgensis MAB1, and Methanosarcina barkeri [58]; Methanobrevibacter spp., Methanomicrobium spp., and Methanosarcinales [14]. |

1) Earth’s secondary atmosphere [57]. 2) Titan [59]. 3) Cow rumen [14]; deep biosphere [58]. |

| Oxygen | 1) Aerotolerant (tolerates some (high to low) amount of O2) | 1) Unknown limit; exposure up to 300 μM O2 in lithifying microbial mat [60]. | 1) Methanosarcina barkeri [23]; Methanogens in microbial mats [24]. Class II methanogens [61]. | 1) Euxinic oceans of Proterozoic [48]; Modern day (and ancient) biofilms and microbial mats [23,24]. |

| Metals | 1) Arsenic 2) Cadmium |

1) Unknown limit; Methane production by methanogens observed under high arsenic concentrations (0.8-1.5 mM) in microbial mats [62,63]. 2) Unknown limit; 10 μM of CdCl2 activates the rate of methanogenesis. ≥ 100 μM of CdCl2 inhibits cell growth [64]. |

1) Methanomassiliicoccus spp. (Chen et al., 2023) 2) Methanosarcina acetivorans [64]. Other divalent metals (Co, Zn, Cu, Fe) also activate the rate of methanogenesis at 10 μM. |

1 & 2) Early oceans [65], rice paddies [66], modern day anoxic microbial mats in the Atacama, Chile [62,63]. |

1.3.1. Temperature Extremes

1.3.2. UV and Ionizing Radiation

1.3.3. Visible Light

1.3.4. Salinity

1.3.5. Pressure

1.3.6. Hydrogen Concentration

1.3.7. Oxygen Exposure

1.3.8. Metals

1.4. Evolution and Diversity of Methanogenic Pathways

1.4.1. Methanogenic Pathways

1.4.1.1. Aceticlastic Methanogenesis

1.4.1.2. Methylotrophic Methanogenesis

1.4.1.3. Lithotrophic Methanogenesis

2. Signatures of Methanogens Through Geologic Time

2.1. The Archean Eon (4-2.5 Gy)

2.1.1. Sulfur Cycling

2.1.2. Environmental Conditions and Photochemistry

2.1.3. Methanogens in Early Hydrothermal Vents

2.1.4. Microbial Mats of the Archean

2.2. The Proterozoic

2.2.1. The Great Oxygenation Event and the Paleoproterozoic (2.5 to 1.6 Gy)

2.2.2. The Boring Billion (1.8 to 0.8 Gy)

2.2.3. Methanogens Through Glaciations

2.2.3.1. The Ending of Marinoan “Snowball” Earth (650 – 635 Mya)

2.2.4. Methanogens Through Mass Extinctions

2.2.4.1. Resurgence of Methanogens and Microbialites Following Mass Extinctions

2.3. Past, Present, and Future – Methanogens in Climate Change

3. Methanogens in Microbial Mats as Biosignatures for Life

3.1. The Evolution of Microbial Mats and Stromatolites

3.2. The Conundrum of Methanogenesis and Oxygen in Mats

4. Methanogens in the Search for Extraterrestrial Life

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Megonigal, J.P.; Mines, M.E.; Visscher, P.T. Anaerobic Metabolism: Linkages to Trace Gases and Aerobic Processes. Biogeochemistry 2004, 8, 317–424.

- Conrad, R. Complexity of Temperature Dependence in Methanogenic Microbial Environments. Front Microbiol 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Buan, N.R. Methanogens: Pushing the Boundaries of Biology. Emerg Top Life Sci 2018, 2, 629–646. [CrossRef]

- Visscher, P.T.; Gallagher, K.L.; Bouton, A.; Vennin, E.; Thomazo, C.; Iii, R.A.W.; Burns, B.P. Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Part B, Vol. 2, Chapter 3: Microbial Mats. Kansas Univ Press 2022, 163, 24–56.

- Kadoya, S.; Catling, D.C. Constraints on Hydrogen Levels in the Archean Atmosphere Based on Detrital Magnetite. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2019, 262, 207–219. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.A.; Krissansen-Totton, J.; Wogan, N.; Telus, M.; Fortney, J.J. The Case and Context for Atmospheric Methane as an Exoplanet Biosignature. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119. [CrossRef]

- Battistuzzi, F.U.; Feijao, A.; Hedges, S.B. A Genomic Timescale of Prokaryote Evolution: Insights into the Origin of Methanogenesis, Phototrophy, and the Colonization of Land. BMC Evol Biol 2004, 4, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, L.; Nature, R.M.-; 2001, undefined Life in Extreme Environments. nature.com 2001.

- Lyons, T.W.; Tino, C.J.; Fournier, G.P.; Anderson, R.E.; Leavitt, W.D.; Konhauser, K.O.; Stüeken, E.E. Co-evolution of Early Earth Environments and Microbial Life. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2024 22:9 2024, 22, 572–586. [CrossRef]

- Taubner, R.-S.; Schleper, C.; Firneis, M.G.; K-M Rittmann, S.R.; Klenk, H.-P.; W Adams, M.W.; Garrett, R.A. Assessing the Ecophysiology of Methanogens in the Context of Recent Astrobiological and Planetological Studies. Life 2015, 5, 1652–1686. [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Yu, H.; Lee, C. Direct Interspecies Electron Transfer Enables Anaerobic Oxidation of Sulfide to Elemental Sulfur Coupled with CO2-Reducing Methanogenesis. iScience 2023, 26, 107504. [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Gu, M.; Hermanowicz, S.W.; Hu, H.; Wu, G. Potential Interactions between Syntrophic Bacteria and Methanogens via Type IV Pili and Quorum-Sensing Systems. Environ Int 2020, 138, 105650. [CrossRef]

- Taubner, R.; Pappenreiter, P.; Zwicker, J.; Bach, W.; Peckmann, J.; Paulik, C.; Firneis, M.; Schleper, C.; Rittman, S. Biological Methane Production under Putative Enceladus-like Conditions. Nat Commun 2018, 748. [CrossRef]

- Morgavi, D.P.; Forano, E.; Martin, C.; Newbold, C.J. Microbial Ecosystem and Methanogenesis in Ruminants. Animal 2010, 4, 1024–1036. [CrossRef]

- Ferry, J.G. Methanosarcina Acetivorans: A Model for Mechanistic Understanding of Aceticlastic and Reverse Methanogenesis. Front Microbiol 2020, 11, 545389. [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, Di.Y.; Makarova, K.S.; Abbas, B.; Ferrer, M.; Golyshin, P.N.; Galinski, E.A.; Ciordia, S.; Mena, M.C.; Merkel, A.Y.; Wolf, Y.I.; et al. Discovery of Extremely Halophilic, Methyl-Reducing Euryarchaea Provides Insights into the Evolutionary Origin of Methanogenesis. Nat Microbiol 2017, 2. [CrossRef]

- Protasov, E.; Nonoh, J.O.; Kästle Silva, J.M.; Mies, U.S.; Hervé, V.; Dietrich, C.; Lang, K.; Mikulski, L.; Platt, K.; Poehlein, A.; et al. Diversity and Taxonomic Revision of Methanogens and Other Archaea in the Intestinal Tract of Terrestrial Arthropods. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1281628. [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Yang, S.; Horn, F.; Winkel, M.; Wagner, D.; Liebner, S. Global Biogeographic Analysis of Methanogenic Archaea Identifies Community-Shaping Environmental Factors of Natural Environments. Front Microbiol 2017, 8, 280269. [CrossRef]

- Merkel, A.Y.; Podosokorskaya, O.A.; Sokolova, T.G.; Bonch-Osmolovskaya, E.A. Diversity of Methanogenic Archaea from the 2012 Terrestrial Hot Spring (Valley of Geysers, Kamchatka). Microbiology (Russian Federation) 2016, 85, 342–349. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qu, Y.N.; Evans, P.N.; Guo, Q.; Zhou, F.; Nie, M.; Jin, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhai, X.; Zhou, M.; et al. Evidence for Nontraditional Mcr-Containing Archaea Contributing to Biological Methanogenesis in Geothermal Springs. Sci Adv 2023, 9. doi:10.1126/SCIADV.ADG6004/SUPPL_FILE/SCIADV.ADG6004_SUPPLEMENTARY_DATA_S1_TO_S4.ZIP. [CrossRef]

- Schulz, S.; Conrad, R. Influence of Temperature on Pathways to Methane Production in the Permanently Cold Profundal Sediment of Lake Constance. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 1996, 20, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Simankova, M. V.; Kotsyurbenko, O.R.; Lueders, T.; Nozhevnikova, A.N.; Wagner, B.; Conrad, R.; Friedrich, M.W. Isolation and Characterization of New Strains of Methanogens from Cold Terrestrial Habitats. Syst Appl Microbiol 2003, 26, 312–318. [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Zhuang, M.; Hong, M.; Zhang, D.; Ren, G.; Hu, A.; Yang, C.; He, Z.; Zhou, S. Methanogenesis in the Presence of Oxygenic Photosynthetic Bacteria May Contribute to Global Methane Cycle. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Buckley, D.H.; Baumgartner, L.K.; Visscher, P.T. Vertical Distribution of Methane Metabolism in Microbial Mats of the Great Sippewissett Salt Marsh. Environ Microbiol 2008, 10, 967–977. [CrossRef]

- Bogard, M.J.; Del Giorgio, P.A.; Boutet, L.; Carolina, M.; Chaves, G.; Prairie, Y.T.; Merante, A.; Derry, A.M. Oxic Water Column Methanogenesis as a Major Component of Aquatic CH 4 Fluxes. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 5350. [CrossRef]

- Patel, L.; Singh, R.; Thottathil, S.D. Contribution of Photosynthesis-Driven Oxic Methane Production to the Methane Cycling of a Tropical River Network. ACS ES&T Water 2024, 4, 2836–2847. [CrossRef]

- Cynar, F.J.; Yayanos, A.A. Enrichment and Characterization of a Methanogenic Bacterium from the Oxic Upper Layer of the Ocean. Curr Microbiol 1991, 23, 89–96. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.J.; Zhang, C.J.; Pan, J.; Liu, Y.; Duan, C.H.; Duan, C.H.; Li, M. Genomic and Transcriptomic Insights into Methanogenesis Potential of Novel Methanogens from Mangrove Sediments. Microbiome 2020, 8, 1–12. doi:10.1186/S40168-020-00876-Z/FIGURES/4. [CrossRef]

- Angle, J.C.; Morin, T.H.; Solden, L.M.; Narrow, A.B.; Sith, G.J.; Borton, M.A.; Rey-Sanchez, C.; Daly, R.A.; Mirfenderesgi, G.; Hoyt, D.W.; et al. Methanogenesis in Oxygenated Soils Is a Substantial Fraction of Wetland Methane Emissions. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 1567. [CrossRef]

- Kendrick, M.G.; Kral, T.A. Survival of Methanogens during Desiccation: Implications for Life on Mars. Astrobiology 2006, 6, 546–551. [CrossRef]

- Kral, T.A.; Travis Aitheide, S. Methanogen Survival Following Exposure to Desiccation, Low Pressure and Martian Regolith Analogs. Planet Space Sci 2013, 89, 167–171. [CrossRef]

- Moissl-Eichinger, C. Archaea in Artificial Environments: Their Presence in Global Spacecraft Clean Rooms and Impact on Planetary Protection. ISME J 2011, 5, 209–219. [CrossRef]

- Mondav, R.; Woodcroft, B.J.; Kim, E.H.; Mccalley, C.K.; Hodgkins, S.B.; Crill, P.M.; Chanton, J.; Hurst, G.B.; Verberkmoes, N.C.; Saleska, S.R.; et al. Discovery of a Novel Methanogen Prevalent in Thawing Permafrost. Nature Communications 2014 5:1 2014, 5, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Takai, K.; Nakamura, K.; Toki, T.; Tsunogai, U.; Miyazaki, M.; Miyazaki, J.; Hirayama, H.; Nakagawa, S.; Nunoura, T.; Horikoshi, K. Cell Proliferation at 122 °C and Isotopically Heavy CH 4 Production by a Hyperthermophilic Methanogen under High-Pressure Cultivation. 2008. Epub2008Jul29. [CrossRef]

- Oremland, R.S.; Marsh, L.; DesMarais, D.J. Methanogenesis in Big Soda Lake, Nevada: An Alkaline, Moderately Hypersaline Desert Lake. Appl Environ Microbiol 1982, 43, 462. [CrossRef]

- Mickol, R.L.; Kral, T.A. Low Pressure Tolerance by Methanogens in an Aqueous Environment: Implications for Subsurface Life on Mars. Origins of Life and Evolution of Biospheres 2017, 47, 511–532. doi:10.1007/S11084- 016-9519-9/FIGURES/4. [CrossRef]

- Kral, T.A.; Altheide, T.S.; Lueders, A.E.; Schuerger, A.C. Low Pressure and Desiccation Effects on Methanogens: Implications for Life on Mars. Planet Space Sci 2011, 59, 264–270. [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, G.; Jaenicke, R.; Ludemann, H.; Konig, H. High Pressure Enhances the Growth Rate of the Thermophilic Archaebacterium Methanococcus Thermolithotrophicus without Extending Its Temperature Range. Appl Environ Microbiol 1988, 54, 1258–1261. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, N.; Kral, T.A. Effect of UVC Radiation on Hydrated and Desiccated Cultures of Slightly Halophilic and Non-Halophilic Methanogenic Archaea: Implications for Life on Mars. Microorganisms 2018, 6, 43. [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.L.; Schuerger, A.C. Hydrogenotrophic Methanogenesis at 7–12 Mbar by Methanosarcina Barkeri under Simulated Martian Atmospheric Conditions. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.L.; Visscher, P.T.; White, R.A.; Smith, D.L.; Patterson, M.M.; Burns, B.P. Dynamics of Archaea at Fine Spatial Scales in Shark Bay Mat Microbiomes. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 1–12. doi:10.1038/SREP46160;TECHMETA=23,45;SUBJMETA=158,26,326,631,704,855;KWRD=ARCHAEA,MICROBIAL+ECOLOGY. [CrossRef]

- Visscher, P.T.; Baumgartner, L.K.; Buckley, D.H.; Rogers, D.R.; Hogan, M.E.; Raleigh, C.D.; Turk, K.A.; Des Marais, D.J. Dimethyl Sulphide and Methanethiol Formation in Microbial Mats: Potential Pathways for Biogenic Signatures. Environ Microbiol 2003, 5, 296–308. [CrossRef]

- Visscher, P.T.; Quist, P.; Van Gemerden, H. Methylated Sulfur Compounds in Microbial Mats: In Situ Concentrations and Metabolism by a Colorless Sulfur Bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol 1991, 57, 1758–1763. [CrossRef]

- Timmers, P.H.A.; Welte, C.U.; Koehorst, J.J.; Plugge, C.M.; Jetten, M.S.M.; Stams, A.J.M. Reverse Methanogenesis and Respiration in Methanotrophic Archaea. Archaea 2017, 2017, 1654237. [CrossRef]

- Boetius, A.; Ravenschlag, K.; Schubert, C.J.; Rickert2, D.; Widdel, F.; Gieseke, A.; Amann, R.; Jùrgensen, B.B.; Witte, U.; Pfannkuche2, O. A Marine Microbial Consortium Apparently Mediating Anaerobic Oxidation of Methane. Nature 2000, 407. [CrossRef]

- Merino, N.; Aronson, H.S.; Bojanova, D.P.; Feyhl-Buska, J.; Wong, M.L.; Zhang, S.; Giovannelli, D. Living at the Extremes: Extremophiles and the Limits of Life in a Planetary Context. Front Microbiol 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T.; Kumar, N.; Cavicchioli, R. Effects of Ribosomes and Intracellular Solutes on Activities and Stabilities of Elongation Factor 2 Proteins from Psychrotolerant and Thermophilic Methanogens. J Bacteriol 2001, 183, 1974–1982. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Beer, L.L.; Whitman, W.B. Methanogens: A Window into Ancient Sulfur Metabolism. Trends Microbiol 2012, 20, 251–258. [CrossRef]

- Nozhevnikova, A.N.; Zepp, K.; Vazquez, F.; Zehnder, A.J.B.; Holliger, C. Evidence for the Existence of Psychrophilic Methanogenic Communities in Anoxic Sediments of Deep Lakes. Appl Environ Microbiol 2003, 69, 1832–1835. doi:10.1128/AEM.69.3.1832-1835.2003/ASSET/B7324751-4850-4993-95E5-369B8A71FD77/ASSETS/GRAPHIC/AM0331479004.JPEG.

- Anderson, K.L.; Apolinario, E.E.; Sowers, K.R. Desiccation as a Long-Term Survival Mechanism for the Archaeon Methanosarcina Barkeri. Appl Environ Microbiol 2012, 78, 1473. [CrossRef]

- Ebisuzaki, T.; Maruyama, S. Nuclear Geyser Model of the Origin of Life: Driving Force to Promote the Synthesis of Building Blocks of Life. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Olson, K.D.; McMahon, C.W.; Wolfe, R.S. Light Sensitivity of Methanogenic Archaebacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 1991, 57, 2683–2686. [CrossRef]

- Angel, R.; Matthies, D.; Conrad, R. Activation of Methanogenesis in Arid Biological Soil Crusts Despite the Presence of Oxygen. PLoS One 2011, 6, e20453. [CrossRef]

- Knauth, L.P. Temperature and Salinity History of the Precambrian Ocean: Implications for the Course of Microbial Evolution. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 2005, 219, 53–69. [CrossRef]

- Martin, W.; Baross, J.; Kelley, D.; Russell, M.J. Hydrothermal Vents and the Origin of Life. Nat Rev Microbiol 2008, 6, 805–814. [CrossRef]

- Horikochi, K. Barophiles: Deep-Sea Microorganisms Adapted to an Extreme Environment. Curr Opin Microbiol 1998, 1, 291–295. [CrossRef]

- Catling, D.C.; Zahnle, K.J. The Archean Atmosphere. Sci Adv 2020, 6. https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIADV.AAX1420/ASSET/6320EA09-4E49-402D-9855-C6D7C27118CD/ASSETS/GRAPHIC/AAX1420-F5.JPEG.

- Neubeck, A.; Sjöberg, S.; Price, A.; Callac, N.; Schnürer, A. Effect of Nickel Levels on Hydrogen Partial Pressure and Methane Production in Methanogens. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0168357. [CrossRef]

- Strobel, D.F. Photochemistry of the Reducing Atmospheres of Jupiter, Saturn and Titan. Int Rev Phys Chem 1983, 3, 145–176. [CrossRef]

- Visscher, P.T.; Dupraz, C.; Braissant, O.; Gallagher, K.L.; Glunk, C.; Casillas, L.; Reed, R.E.S. Biogeochemistry of Carbon Cycling in Hypersaline Mats: Linking the Present to the Past through Biosignatures. 2010, 443–468. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.; Lu, Y. Metabolic Shift at the Class Level Sheds Light on Adaptation of Methanogens to Oxidative Environments. ISME Journal 2018, 12, 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1038/ISMEJ.2017.173;TECHMETA=45;SUBJMETA=158,2526,26,326,631,855;KWRD=ARCHAEAL+GENOMICS,MICROBIAL+ECOLOGY. [CrossRef]

- Lepot, K. Signatures of Early Microbial Life from the Archean (4 to 2.5 Ga) Eon. Earth Sci Rev 2020, 209, 103296. [CrossRef]

- Visscher, P.T.; Gallagher, K.L.; Bouton, A.; Farias, M.E.; Kurth, D.; Sancho-Tomás, M.; Philippot, P.; Somogyi, A.; Medjoubi, K.; Vennin, E.; et al. Modern Arsenotrophic Microbial Mats Provide an Analogue for Life in the Anoxic Archean. Communications Earth & Environment 2020 1:1 2020, 1, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Lira-Silva, E.; Santiago-Martínez, M.G.; Hernández-Juárez, V.; García-Contreras, R.; Moreno-Sánchez, R.; Jasso-Chávez, R. Activation of Methanogenesis by Cadmium in the Marine Archaeon Methanosarcina Acetivorans. PLoS One 2012, 7, e48779. [CrossRef]

- Anbar, A.D.; Knoll, A.H. Proterozoic Ocean Chemistry and Evolution: A Bioinorganic Bridge? Science (1979) 2002, 297, 1137–1142. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, L.; Huang, K.; Zhang, J.; Xie, W.Y.; Lu, Y.; Dong, X.; Zhao, F.J. Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria and Methanogens Are Involved in Arsenic Methylation and Demethylation in Paddy Soils. ISME Journal 2019, 13, 2523–2535. [CrossRef]

- Karr, E.A.; Sattley, W.M.; Rice, M.R.; Jung, D.O.; Madigan, M.T.; Achenbach, L.A. Diversity and Distribution of Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria in Permanently Frozen Lake Fryxell, McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica. Appl Environ Microbiol 2005, 71, 6353–6359. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Jiang, N.; Liu, X.; Dong, X. Methanogenesis from Methanol at Low Temperatures by a Novel Psychrophilic Methanogen, “Methanolobus Psychrophilus” Sp. Nov., Prevalent in Zoige Wetland of the Tibetan Plateau. Appl Environ Microbiol 2008, 74, 6114–6120. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01146-08/SUPPL_FILE/SUPPLEMENT_MATERIAL.ZIP.

- Zhao, Z.; Shen, B.; Zhu, J.M.; Lang, X.; Wu, G.; Tan, D.; Pei, H.; Huang, T.; Ning, M.; Ma, H. Active Methanogenesis during the Melting of Marinoan Snowball Earth. Nat Commun 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Bao, H.; Jiang, G.; Crockford, P.; Feng, D.; Xiao, S.; Kaufman, A.J.; Wang, J. A Transient Peak in Marine Sulfate after the 635-Ma Snowball Earth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119. [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Kemp, D.B.; Tian, L.; Chu, D.; Song, H.; Dai, X. Thresholds of Temperature Change for Mass Extinctions. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41467-021-25019-2;SUBJMETA=158,181,2462,414,631,670,704;KWRD=BIODIVERSITY,PALAEOECOLOGY,PALAEONTOLOGY.

- Noon, K.R.; Guymon, R.; Crain, P.F.; McCloskey, J.A.; Thomm, M.; Lim, J.; Cavicchioli, R. Influence of Temperature on TRNA Modification in Archaea: Methanococcoides Burtonii (Optimum Growth Temperature [Topt], 23 °C) and Stetteria Hydrogenophila (Topt, 95 °C). J Bacteriol 2003, 185, 5483–5490. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.185.18.5483-5490.2003/ASSET/84D10F3D-7305-46A9-9F70-323BE4B94A4B/ASSETS/GRAPHIC/JB1830355003.JPEG.

- Lim, J.; Thomas, T.; Cavicchioli, R. Low Temperature Regulated DEAD-Box RNA Helicase from the Antarctic Archaeon, Methanococcoides Burtonii. J Mol Biol 2000, 297, 553–567. [CrossRef]

- Shimada, Y.; Fukuda, W.; Akada, Y.; Ishida, M.; Nakayama, J.; Imanaka, T.; Fujiwara, S. Property of Cold Inducible DEAD-Box RNA Helicase in Hyperthermophilic Archaea. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009, 389, 622–627. [CrossRef]

- Saunders, N.F.W.; Thomas, T.; Curmi, P.M.G.; Mattick, J.S.; Kuczek, E.; Slade, R.; Davis, J.; Franzmann, P.D.; Boone, D.; Rusterholtz, K.; et al. Mechanisms of Thermal Adaptation Revealed from the Genomes of the Antarctic. Genome Res 2003, 13, 1580–1588. [CrossRef]

- Nichols, D.S.; Miller, M.R.; Davies, N.W.; Goodchild, A.; Raftery, M.; Cavicchioli, R. Cold Adaptation in the Antarctic Archaeon Methanococcoides Burtonii Involves Membrane Lipid Unsaturation. J Bacteriol 2004, 186, 8508–8515. [CrossRef]

- Koga, Y. Thermal Adaptation of the Archaeal and Bacterial Lipid Membranes. Archaea 2012, 2012, 789652. [CrossRef]

- Cheptsov, V.S.; Vorobyova, E.A.; Osipov, G.A.; Manucharova, N.A.; Polyanskaya, L.M.; Gorlenko, M. V.; Pavlov, A.K.; Rosanova, M.S.; Lomasov, V.N. Microbial Activity in Martian Analog Soils after Ionizing Radiation: Implications for the Preservation of Subsurface Life on Mars. AIMS Microbiol 2018, 4, 541–562. [CrossRef]

- Cockell, C.S. Biological Effects of High Ultraviolet Radiation on Early Earth—a Theoretical Evaluation. J Theor Biol 1998, 193, 717–729. [CrossRef]

- Zahnle, K.J.; Walker, J.C.G. The Evolution of Solar Ultraviolet Luminosity. Reviews of Geophysics 1982, 20, 280–292. [CrossRef]

- Ohlendorf, R.; Möglich, A. Light-Regulated Gene Expression in Bacteria: Fundamentals, Advances, and Perspectives. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Elahi, Y.; Baker, M.A.B. Light Control in Microbial Systems. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, Vol. 25, Page 4001 2024, 25, 4001. [CrossRef]

- Katayama, T.; Kamagata, Y. Cultivation of Methanogens. 2015, 177–195. [CrossRef]

- Paula, F.S.; Chin, J.P.; Schnürer, A.; Müller, B.; Manesiotis, P.; Waters, N.; Macintosh, K.A.; Quinn, J.P.; Connolly, J.; Abram, F.; et al. The Potential for Polyphosphate Metabolism in Archaea and Anaerobic Polyphosphate Formation in Methanosarcina Mazei. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Mullaymeri, A.; Payr, M.; Wunderer, M.; Eva Maria, E.M.; Wagner, A.O. Shaken Not Stirred - Effect of Different Mixing Modes during the Cultivation of Methanogenic Pure Cultures. Curr Res Microb Sci 2025, 8, 100386. [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, L.C.; Maher, D.T.; Johnston, S.G.; Kelaher, B.P.; Steven, A.; Tait, D.R. Wetland Methane Emissions Dominated by Plant-Mediated Fluxes: Contrasting Emissions Pathways and Seasons within a Shallow Freshwater Subtropical Wetland. Limnol Oceanogr 2019, 64, 1895–1912. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xiao, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Pu, Y.; Wang, W.; Xiao, W.; Liu, S.; Lee, X. Methane Flux Dynamics in a Submerged Aquatic Vegetation Zone in a Subtropical Lake. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 672, 400–409. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Purdy, K.J.; Eyice, Ö.; Shen, L.; Harpenslager, S.F.; Yvon-Durocher, G.; Dumbrell, A.J.; Trimmer, M. Disproportionate Increase in Freshwater Methane Emissions Induced by Experimental Warming. Nat Clim Chang 2020, 10, 685–690. [CrossRef]

- Bolhuis, H.; Cretoiu, M.S.; Stal, L.J. Molecular Ecology of Microbial Mats. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2014, 90, 335–350. [CrossRef]

- Grossart, H.P.; Frindte, K.; Dziallas, C.; Eckert, W.; Tang, K.W. Microbial Methane Production in Oxygenated Water Column of an Oligotrophic Lake. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, 19657–19661. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sun, P.; Liu, J.; Xu, Y.; Dolfing, J.; Wu, Y. Distribution of Methanogenic and Methanotrophic Consortia at Soil-Water Interfaces in Rice Paddies across Climate Zones. iScience 2023, 26, 105851. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Liu, X.; Rensing, C.; Yuan, Y.; Zhou, S.; Nealson, K.H. Light-Independent Anaerobic Microbial Oxidation of Manganese Driven by an Electrosyntrophic Coculture. ISME Journal 2023, 17, 163–171. [CrossRef]

- Kalathil, S.; Rahaman, M.; Lam, E.; Augustin, T.L.; Greer, H.F.; Reisner, E. Solar-Driven Methanogenesis through Microbial Ecosystem Engineering on Carbon Nitride. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2024, 63, e202409192. [CrossRef]

- Olson, S.; Jansen, M.F.; Abbot, D.S.; Halevy, I.; Goldblatt, C. The Effect of Ocean Salinity on Climate and Its Implications for Earth’s Habitability. Geophys Res Lett 2022, 49, e2021GL095748. [CrossRef]

- Bardavid, R.E.; Oren, A. The Amino Acid Composition of Proteins from Anaerobic Halophilic Bacteria of the Order Halanaerobiales. Extremophiles 2012, 16, 567–572. [CrossRef]

- Welsh, D.T. Ecological Significance of Compatible Solute Accumulation by Micro- Organisms: From Single Cells to Global Climate. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2000, 24, 263–290. [CrossRef]

- Empadinhas, N.; da Costa, M.S. Osmoadaptation Mechanisms in Prokaryotes: Distribution of Compatible Solutes. Int Microbiol 2008, 11, 151–161. [CrossRef]

- Stüeken, E.E.; Buick, R.; Guy, B.M.; Koehler, M.C. Isotopic Evidence for Biological Nitrogen Fixation by Molybdenum-Nitrogenase from 3.2 Gyr. Nature 2015, 520, 666–669. https://doi.org/10.1038/NATURE14180;TECHMETA=140,58;SUBJMETA=158,181,47,631,704;KWRD=BIOGEOCHEMISTRY,EVOLUTION.

- Hoehler, T.M.; Bebout, B.M.; Des Marais, D.J. The Role of Microbial Mats in the Production of Reduced Gases on the Early Earth. Nature 2001, 412, 324–327. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ungerfeld, E.M.; Wang, R.; Zhou, C.S.; Basang, Z.Z.; Ao, S.M.; Tan, Z.L. Supersaturation of Dissolved Hydrogen and Methane in Rumen of Tibetan Sheep. Front Microbiol 2016, 7. [CrossRef]

- Catling, D.C. The Great Oxidation Event Transition. Treatise on Geochemistry: Second Edition 2014, 6, 177–195. [CrossRef]

- Jasso-Chávez, R.; Santiago-Martínez, M.G.; Lira-Silva, E.; Pineda, E.; Zepeda-Rodríguez, A.; Belmont-Díaz, J.; Encalada, R.; Saavedra, E.; Moreno-Sánchez, R. Air-Adapted Methanosarcina Acetivorans Shows High Methane Production and Develops Resistance against Oxygen Stress. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0117331. [CrossRef]

- Ernst, L.; Steinfeld, B.; Barayeu, U.; Klintzsch, T.; Kurth, M.; Grimm, D.; Dick, T.P.; Rebelein, J.G.; Bischofs, I.B.; Keppler, F. Methane Formation Driven by Reactive Oxygen Species across All Living Organisms. Nature 2022 603:7901 2022, 603, 482–487. [CrossRef]

- Eliani-Russak, E.; Tik, Z.; Uzi-Gavrilov, S.; Meijler, M.M.; Sivan, O. The Reduction of Environmentally Abundant Iron Oxides by the Methanogen Methanosarcina Barkeri. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1197299. [CrossRef]

- Glass, J.B.; Orphan, V.J. Trace Metal Requirements for Microbial Enzymes Involved in the Production and Consumption of Methane and Nitrous Oxide. Front Microbiol 2012, 3, 61. [CrossRef]

- Rossetto, D.; Mansy, S.S. Metals Are Integral to Life as We Know It. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 864830. [CrossRef]

- Capdevila, D.A.; Edmonds, K.A.; Giedroc, D.P. Metallochaperones and Metalloregulation in Bacteria. Essays Biochem 2017, 61, 177–200. [CrossRef]

- Summons, R.E.; Welander, P. V.; Gold, D.A. Lipid Biomarkers: Molecular Tools for Illuminating the History of Microbial Life. Nat Rev Microbiol 2022, 20, 174–185. [CrossRef]

- Mulkidjanian, A.Y.; Bychkov, A.Y.; Dibrova, D. V.; Galperin, M.Y.; Koonin, E. V. Origin of First Cells at Terrestrial, Anoxic Geothermal Fields. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, E821–E830. https://doi.org/10.1073/PNAS.1117774109/SUPPL_FILE/SAPP.PDF. [CrossRef]

- Ünal, B.; Perry, V.R.; Sheth, M.; Gomez-Alvarez, V.; Chin, K.J.; Nüsslein, K. Trace Elements Affect Methanogenic Activity and Diversity in Enrichments from Subsurface Coal Bed Produced Water. Front Microbiol 2012, 3, 175. [CrossRef]

- Abdel Azim, A.; Rittmann, S.K.M.R.; Fino, D.; Bochmann, G. The Physiological Effect of Heavy Metals and Volatile Fatty Acids on Methanococcus Maripaludis S2. Biotechnol Biofuels 2018, 11, 1–16. doi:10.1186/S13068-018-1302-X/TABLES/2. [CrossRef]

- Spietz, R.L.; Payne, D.; Boyd, E.S. Methanogens Acquire and Bioaccumulate Nickel during Reductive Dissolution of Nickelian Pyrite. Appl Environ Microbiol 2023, 89. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00991-23/SUPPL_FILE/AEM.00991-23-S0002.XLS.

- Glass, J.B.; Chen, S.; Dawson, K.S.; Horton, D.R.; Vogt, S.; Ingall, E.D.; Twining, B.S.; Orphan, V.J. Trace Metal Imaging of Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria and Methanogenic Archaea at Single-Cell Resolution by Synchrotron X-Ray Fluorescence Imaging. Geomicrobiol J 2018, 35, 81–89. [CrossRef]

- Holmes, D.E.; Tang, H.; Woodard, T.; Liang, D.; Zhou, J.; Liu, X.; Lovley, D.R. Cytochrome-Mediated Direct Electron Uptake from Metallic Iron by Methanosarcina Acetivorans. mLife 2022, 1, 443–447. https://doi.org/10.1002/MLF2.12044;JOURNAL:JOURNAL:2770100X;WGROUP:STRING:PUBLICATION.

- Wagner, T.; Ermler, U.; Shima, S. The Methanogenic CO2 Reducing-and-Fixing Enzyme Is Bifunctional and Contains 46 [4Fe-4S] Clusters. Science (1979) 2016, 354, 114–117. https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIENCE.AAF9284/SUPPL_FILE/WAGNER.SM.PDF.

- Demirel, B.; Scherer, P. Trace Element Requirements of Agricultural Biogas Digesters during Biological Conversion of Renewable Biomass to Methane. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 992–998. [CrossRef]

- Rother, M.; Krzycki, J.A. Selenocysteine, Pyrrolysine, and the Unique Energy Metabolism of Methanogenic Archaea. Archaea 2010, 2010, 453642. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.; England, A.; Munro-Ehrlich, M.; Colman, D.R.; DuBois, J.L.; Boyd, E.S. Pathways of Iron and Sulfur Acquisition, Cofactor Assembly, Destination, and Storage in Diverse Archaeal Methanogens and Alkanotrophs. J Bacteriol 2021, 203, 117–138. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00117-21/SUPPL_FILE/JB.00117-21-S0005.XLSX.

- Bini, E. Archaeal Transformation of Metals in the Environment. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2010, 73, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Konhauser, K.O.; Pecoits, E.; Lalonde, S. V.; Papineau, D.; Nisbet, E.G.; Barley, M.E.; Arndt, N.T.; Zahnle, K.; Kamber, B.S. Oceanic Nickel Depletion and a Methanogen Famine before the Great Oxidation Event. Nature 2009, 458, 750–753. https://doi.org/10.1038/NATURE07858;KWRD=SCIENCE.

- Gottschalk, G.; Thauer, R.K. The Na+-Translocating Methyltransferase Complex from Methanogenic Archaea. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 2001, 1505, 28–36. [CrossRef]

- Boone, D.R.; Mah, R.A. Effects of Calcium, Magnesium, PH, and Extent of Growth on the Morphology of Methanosarcina Mazei S-6. Appl Environ Microbiol 1987, 53, 1699–1700. [CrossRef]

- Vanček, M.; Vidová, M.; Majerník, A.I.; Šmigáň, P. Methanogenesis Is Ca2+ Dependent in Methanothermobacter Thermautotrophicus Strain DeltaH. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2006, 258, 269–273. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, F.; Ding, G.; Li, J.; Guo, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, L.; Cai, S.; Liu, X.; Luo, Y.; et al. Acyl Homoserine Lactone-Based Quorum Sensing in a Methanogenic Archaeon. ISME Journal 2012, 6, 1336–1344. https://doi.org/10.1038/ISMEJ.2011.203;SUBJMETA.

- Yepez-Ceron, O.D.; McCarthy, P.; Patterson, S.; Casey, E.; Dereli, R.K. The Role of Calcium in Anaerobic Treatment: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Water Res X 2025, 28, 100381. [CrossRef]

- Thauer, R.K.; Kaster, A.K.; Goenrich, M.; Schick, M.; Hiromoto, T.; Shima, S. Hydrogenases from Methanogenic Archaea, Nickel, a Novel Cofactor, and H2 Storage. Annu Rev Biochem 2010, 79, 507–536. [CrossRef]

- Leimkühler, S. Metal-Containing Formate Dehydrogenases, a Personal View. Molecules 2023, Vol. 28, Page 5338 2023, 28, 5338. [CrossRef]

- Mota, C.S.; Rivas, M.G.; Brondino, C.D.; Moura, I.; Moura, J.J.G.; González, P.J.; Cerqueira, N.M.F.S.A. The Mechanism of Formate Oxidation by Metal-Dependent Formate Dehydrogenases. J Biol Inorg Chem 2011, 16, 1255–1268. [CrossRef]

- Payne, D.; Keller, L.M.; Larson, J.; Bothner, B.; Colman, D.R.; Boyd, E.S. Alternative Sources of Molybdenum for Methanococcus Maripaludis and Their Implication for the Evolution of Molybdoenzymes. Communications Biology 2024 7:1 2024, 7, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Tchounwou, P.B.; Yedjou, C.G.; Patlolla, A.K.; Sutton, D.J. Heavy Metals Toxicity and the Environment. EXS 2012, 101, 133. [CrossRef]

- Marcovecchio JE, SE Botté, R.F. Heavy Metals, Major Metals, Trace Elements. In Handbook of Water AnalysisEdition; Nollet, L.M.L., Ed.; CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group LCC, Boca Ratón: Florida (USA), 2007; pp. 273–210.

- Slyemi, D.; Bonnefoy, V. How Prokaryotes Deal with Arsenic†. Environ Microbiol Rep 2011, 4, no-no. [CrossRef]

- Van Lis, R.; Nitschke, W.; Duval, S.; Schoepp-Cothenet, B. Arsenics as Bioenergetic Substrates. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 2013, 1827, 176–188.

- Fekih, I. Ben; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.P.; Zhao, Y.; Alwathnani, H.A.; Saquib, Q.; Rensing, C.; Cervantes, C. Distribution of Arsenic Resistance Genes in Prokaryotes. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 2473. [CrossRef]

- Fru, E.C.; Somogyi, A.; El Albani, A.; Medjoubi, K.; Aubineau, J.; Robbins, L.J.; Lalonde, S. V.; Konhauser, K.O. The Rise of Oxygen-Driven Arsenic Cycling at ca. 2.48 Ga. Geology 2019, 47, 243–246. [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Alvarez, R.; Cortinas, I.; Yenal, U.; Field, J.A. Methanogenic Inhibition by Arsenic Compounds. Appl Environ Microbiol 2004, 70, 5688. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Freire, L.; Moore, S.E.; Sierra-Alvarez, R.; Field, J.A. Adaptation of a Methanogenic Consortium to Arsenite Inhibition. Water Air Soil Pollut 2015, 226, 414. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Shi, L.; Wang, M.; Yuan, X.; Wang, S.; Ye, L.; Yan, Z. Molecular Basis of Thioredoxin-Dependent Arsenic Transformation in Methanogenic Archaea. Environ Sci Technol 2025, 59, 443–453. https://doi.org/10.1021/ACS.EST.4C06611/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/ES4C06611_0005.JPEG.

- Lira-Silva, E.; Santiago-Martínez, M.G.; Hernández-Juárez, V.; García-Contreras, R.; Moreno-Sánchez, R.; Jasso-Chávez, R. Activation of Methanogenesis by Cadmium in the Marine Archaeon Methanosarcina Acetivorans. PLoS One 2012, 7, e48779. [CrossRef]

- Lira-Silva, E.; Santiago-Martínez, M.G.; García-Contreras, R.; Zepeda-Rodríguez, A.; Marín-Hernández, A.; Moreno-Sánchez, R.; Jasso-Chávez, R. Cd2+ Resistance Mechanisms in Methanosarcina Acetivorans Involve the Increase in the Coenzyme M Content and Induction of Biofilm Synthesis. Environ Microbiol Rep 2013, 5, 799–808. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Dong, H.; Liu, D.; Zhao, L.; Marts, A.R.; Farquhar, E.; Tierney, D.L.; Almquist, C.B.; Briggs, B.R. Reduction of Hexavalent Chromium by the Thermophilic Methanogen Methanothermobacter Thermautotrophicus. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2014, 148, 442. [CrossRef]

- Ueno, Y.; Yamada, K.; Yoshida, N.; Maruyama, S.; Isozaki, Y. Evidence from Fluid Inclusions for Microbial Methanogenesis in the Early Archaean Era. Nature 2006 440:7083 2006, 440, 516–519. [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, J.M.; Fournier, G.P. Horizontal Gene Transfer Constrains the Timing of Methanogen Evolution. Nat Ecol Evol 2018, 2, 897–903. [CrossRef]

- Lowe, D.R.; Byerly, G.R. The Terrestrial Record of Late Heavy Bombardment. New Astronomy Reviews 2018, 81, 39–61. [CrossRef]

- Mißbach, H.; Duda, J.P.; van den Kerkhof, A.M.; Lüders, V.; Pack, A.; Reitner, J.; Thiel, V. Ingredients for Microbial Life Preserved in 3.5 Billion-Year-Old Fluid Inclusions. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41467-021-21323-Z;TECHMETA=133,140,58;SUBJMETA=209,213,2151,47,704;KWRD=BIOGEOCHEMISTRY,GEOCHEMISTRY,GEOLOGY.

- Hinrichs, K.U. Microbial Fixation of Methane Carbon at 2.7 Ga: Was an Anaerobic Mechanism Possible? Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 2002, 3, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Brocks, J.J.; Logan, G.A.; Buick, R.; Summons, R.E. Archean Molecular Fossils and the Early Rise of Eukaryotes. Science (1979) 1999, 285, 1033–1036. [CrossRef]

- Kohtz, A.J.; Petrosian, N.; Krukenberg, V.; Jay, Z.J.; Pilhofer, M.; Hatzenpichler, R. Cultivation and Visualization of a Methanogen of the Phylum Thermoproteota. Nature 2024 632:8027 2024, 632, 1118–1123. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Igarashi, K.; Liu, L.; Mayumi, D.; Ujiie, T.; Fu, L.; Yang, M.; Lu, Y.; Cheng, L.; Kato, S.; et al. Methanol Transfer Supports Metabolic Syntrophy between Bacteria and Archaea. Nature 2025, 639, 190–195. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41586-024-08491-W;TECHMETA.

- Cozannet, M.; Le Guellec, S.; Alain, K. A Variety of Substrates for Methanogenesis. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering 2023, 8, 100533. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.J.; Calixto Contreras, M.; Reed, J.L. Thermodynamics and H2 Transfer in a Methanogenic, Syntrophic Community. PLoS Comput Biol 2015, 11, e1004364. [CrossRef]

- Kato, S.; Hashimoto, K.; Watanabe, K. Methanogenesis Facilitated by Electric Syntrophy via (Semi)Conductive Iron-Oxide Minerals. Environ Microbiol 2012, 14, 1646–1654. [CrossRef]

- Ishii, ichi; Kosaka, T.; Hori, K.; Hotta, Y.; Watanabe, K. Coaggregation Facilitates Interspecies Hydrogen Transfer between Pelotomaculum Thermopropionicum and Methanothermobacter Thermautotrophicus. Appl Environ Microbiol 2005, 71, 7838–7845. [CrossRef]

- Meulepas, R.J.W.; Jagersma, C.G.; Khadem, A.F.; Stams, A.J.M.; Lens, P.N.L. Effect of Methanogenic Substrates on Anaerobic Oxidation of Methane and Sulfate Reduction by an Anaerobic Methanotrophic Enrichment. APPLIED MICROBIAL AND CELL PHYSIOLOGY 2010, 87, 1499–1506. [CrossRef]

- Stams, A.J.M.; Plugge, C.M. Electron Transfer in Syntrophic Communities of Anaerobic Bacteria and Archaea. Nat Rev Microbiol 2009, 7, 568–577. https://doi.org/10.1038/NRMICRO2166;KWRD.

- Oremland, R.S.; Marsh, L.M.; Polcin, S. Methane Production and Simultaneous Sulphate Reduction in Anoxic, Salt Marsh Sediments. Nature 1982, 296, 143–145. https://doi.org/10.1038/296143A0;KWRD.

- Cappenberg, T.E.; Prins, R.A. Interrelations between Sulfate-Reducing and Methane-Producing Bacteria in Bottom Deposits of a Fresh-Water Lake. III. Experiments with 14C-Labeled Substrates. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 1974, 40, 457–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00399358/METRICS.

- Ferry, J.G. Fundamentals of Methanogenic Pathways That Are Key to the Biomethanation of Complex Biomass. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2011, 22, 351. [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, D.Y.; Banciu, H.L.; Muyzer, G. Functional Microbiology of Soda Lakes. Curr Opin Microbiol 2015, 25, 88–96. [CrossRef]

- Wormald, R.M.; Hopwood, J.; Humphreys, P.N.; Mayes, W.; Gomes, H.I.; Rout, S.P. Methanogenesis from Mineral Carbonates, a Potential Indicator for Life on Mars. Geosciences (Switzerland) 2022, 12, 138. [CrossRef]

- Kral, T.A.; Birch, W.; Lavender, L.E.; Virden, B.T. Potential Use of Highly Insoluble Carbonates as Carbon Sources by Methanogens in the Subsurface of Mars. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Fiore, N.A.; Kohtz, A.J.; Miller, D.N.; Antony-Babu, S.; Pan, D.; Lahey, C.; Huang, X.; Lu, Y.; Buan, N.R.; Weber, K.A. Microbial Methane Production from Calcium Carbonate at Moderately Alkaline PH. Commun Earth Environ 2025, 6, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Toon, O.B.; Pavlov, A.A.; De Sterck, H. A Hydrogen-Rich Early Earth Atmosphere. Science (1979) 2005, 308, 1014–1017. [CrossRef]

- Novelli, P.C.; Lang, P.M.; Masarie, K.A.; Hurst, D.F.; Myers, R.; Elkins, J.W. Molecular Hydrogen in the Troposphere: Global Distribution and Budget. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 1999, 104, 30427–30444. [CrossRef]

- Mei, R.; Kaneko, M.; Imachi, H.; Nobu, M.K. The Origin and Evolution of Methanogenesis and Archaea Are Intertwined. PNAS Nexus 2023, 2, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.C.; Soussa, F.L.; Mrnjavac, N.; Neukirchen, S.; Roettger, M.; Nelson-Sathi, S.; Martin, W.F. The Physiology and Habitat of the Last Universal Common Ancestor. Nat Microbiol 2016, 1, 16116. [CrossRef]

- Schopf, J.W.; Kitajima, K.; Spicuzza, M.J.; Kudryavtsev, A.B.; Valley, J.W. SIMS Analyses of the Oldest Known Assemblage of Microfossils Document Their Taxon-Correlated Carbon Isotope Compositions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, 53–58. [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.S.; Mobberley, J.M. Past, Present, and Future: Microbial Mats as Models for Astrobiological Research. 2010, 563–582. [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Cao, J.; Hu, W.; Zhi, D.; Tang, Y.; Li, E.; He, W. Coupling of Paleoenvironment and Biogeochemistry of Deep-Time Alkaline Lakes: A Lipid Biomarker Perspective. Earth Sci Rev 2021, 213, 103499. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Feng, Q.; Lu, H.; Peng, P.; Zhang, T.; Hsu, C.S. Stable Carbon Isotopic Fractionation and Hydrocarbon Generation Mechanism of CO2 Fischer–Tropsch-Type Synthesis under Hydrothermal Conditions. Energy & Fuels 2021, 35, 11909–11919. [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, R. Quantifying Natural Hydrogen Generation Rates and Volumetric Potential in Onshore Serpentinization. Geosciences (Basel) 2025, 3, 112. [CrossRef]

- Kasting, J.F.; Siefert, J.L. Life and the Evolution of Earth’s Atmosphere. Science (1979) 2002, 296, 1066–1068. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Wang, M.; Du, X.; He, X.; Xu, T.; Liu, X.; Song, F. The Impact of Elevated CO2 on Methanogen Abundance and Methane Emissions in Terrestrial Ecosystems: A Meta-Analysis. iScience 2024, 27, 111504. [CrossRef]

- Olson, S.L.; Reinhard, C.T.; Lyons, T.W. Limited Role for Methane in the Mid-Proterozoic Greenhouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, 11447–11452. [CrossRef]

- Canfield, D.E.; Raiswell, R. The Evolution of the Sulfur Cycle. Am J Sci 1999, 299, 697–723. [CrossRef]

- Steward, K.F.; Payne, D.; Kincannon, W.; Johnson, C.; Lensing, M.; Fausset, H.; Németh, B.; Shepard, E.M.; Broderick, W.E.; Broderick, J.B.; et al. Proteomic Analysis of Methanococcus Voltae Grown in the Presence of Mineral and Nonmineral Sources of Iron and Sulfur. Microbiol Spectr 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Payne, D.; Spietz, R.L.; Boyd, E.S. Reductive Dissolution of Pyrite by Methanogenic Archaea. ISME J 2021, 15, 3498–3507. [CrossRef]

- Canfield, D.E. Biogeochemistry of Sulfur Isotopes. Rev Mineral Geochem 2001, 43, 607–636. [CrossRef]

- Canfield, D.E.; Habicht, K.S.; Thamdrup, B. The Archean Sulfur Cycle and the Early History of Atmospheric Oxygen. Science (1979) 2000, 288, 658–661. https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIENCE.288.5466.658/SUPPL_FILE/CANFIELD.XHTML.

- Fakhraee, M.; Crockford, P.W.; Bauer, K.W.; Pasquier, V.; Sugiyama, I.; Katsev, S.; Raven, M.R.; Gomes, M.; Philippot, P.; Crowe, S.A.; et al. The History of Earth’s Sulfur Cycle. Nat Rev Earth Environ 2025, 6, 106–125. [CrossRef]

- Fakhraee, M.; Katsev, S. Organic Sulfur Was Integral to the Archean Sulfur Cycle. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Reeves, E.P.; McDermott, J.M.; Seewald, J.S. The Origin of Methanethiol in Midocean Ridge Hydrothermal Fluids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 5474–5479. [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, R.J.; Van Kranendonk, M.J.; Caruso, S.; Campbell, K.A.; Dobson, M.J.; Teece, B.L.; Verrall, M.; Homann, M.; Lalonde, S.; Visscher, P.T. Pyritic Stromatolites from the Paleoarchean Dresser Formation, Pilbara Craton: Resolving Biogenicity and Hydrothermally Influenced Ecosystem Dynamics. Geobiology 2024, 22. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Wang, Y.; Huang, F.; Yang, Y.; Long, Y.; Fang, C.; Hu, L. Uncover Co-Evolution of Arsenic Transformation and Methanogens in Landfills. J Hazard Mater 2025, 497, 139623. [CrossRef]

- Moody, E.R.R.; Álvarez-Carretero, S.; Mahendrarajah, T.A.; Clark, J.W.; Betts, H.C.; Dombrowski, N.; Szánthó, L.L.; Boyle, R.A.; Daines, S.; Chen, X.; et al. The Nature of the Last Universal Common Ancestor and Its Impact on the Early Earth System. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2024 8:9 2024, 8, 1654–1666. [CrossRef]

- Hren, M.T.; Tice, M.M.; Chamberlain, C.P. Oxygen and Hydrogen Isotope Evidence for a Temperate Climate 3.42 Billion Years Ago. Nature 2009 462:7270 2009, 462, 205–208. [CrossRef]

- Blake, R.E.; Chang, S.J.; Lepland, A. Phosphate Oxygen Isotopic Evidence for a Temperate and Biologically Active Archaean Ocean. Nature 2010 464:7291 2010, 464, 1029–1032. [CrossRef]

- Penny, D.; Poole, A. The Nature of the Last Universal Common Ancestor. Current Opinions in Genetics & Development 1999, 9, 672–677.

- Liu, R.; Gong, H.; Xu, Y.; Cai, C.; Hua, Y.; Li, L.; Dai, L.; Dai, X. The Transition Temperature (42 °C) from Mesophilic to Thermophilic Micro-Organisms Enhances Biomethane Potential of Corn Stover. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 759, 143549. [CrossRef]

- Catling, D.C.; Zahnle, K.J.; McKay, C.P. Biogenic Methane, Hydrogen Escape, and the Irreversible Oxidation of Early Earth. Science (1979) 2001, 293, 839–843. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Lv, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Fan, Q.; Yanf, Z.; Boon, N.; Wang, F.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, Y. Genomic and Enzymatic Evidence of Acetogenesis by Anaerobic Methanotrophic Archaea. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 3941. [CrossRef]

- Ettwig, K.F.; Zhu, B.; Speth, D.; Keltjens, J.T.; Jetten, M.S.M.; Kartal, B. Archaea Catalyze Iron-Dependent Anaerobic Oxidation of Methane. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113, 12792–12796. [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, A.A.; Kasting, J.F.; Eigenbrode, J.L.; Freeman, K.H. Organic Haze in Earth’s Early Atmosphere: Source of Low-13C Late Archean Kerogens? | Geology | GeoScienceWorld. Geology 2001, 29, 1003–1006.

- Tian, F.; Kasting, J.F.; Zahnle, K. Revisiting HCN Formation in Earth’s Early Atmosphere. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2011, 308, 417–423. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E.T.; Toon, O.B. Fractal Organic Hazes Provided an Ultraviolet Shield for Early Earth. Science (1979) 2010, 328, 1266–1268. [CrossRef]

- Dupraz, C.; Visscher, P.T. Microbial Lithification in Marine Stromatolites and Hypersaline Mats. Trends Microbiol 2005, 13, 429–438. [CrossRef]

- Colman, D.R.; Templeton, A.S.; Spear, J.R.; Boyd, E.S. Microbial Ecology of Serpentinite-Hosted Ecosystems. ISME J 2025, 19, 29. [CrossRef]

- Shibuya, T.; Komiya, T.; Nakamura, K.; Takai, K.; Maruyama, S. Highly Alkaline, High-Temperature Hydrothermal Fluids in the Early Archean Ocean. Precambrian Res 2010, 182, 230–238. [CrossRef]

- Preiner, M.; Xavier, J.C.; Sousa, F.L.; Zimorski, V.; Neubeck, A.; Lang, S.Q.; Chris Greenwell, H.; Kleinermanns, K.; Tüysüz, H.; McCollom, T.M.; et al. Serpentinization: Connecting Geochemistry, Ancient Metabolism and Industrial Hydrogenation. Life (Basel) 2018, 8. [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, M.N.; Little, C.T.S.; Bailey, R.J.; Ball, A.D.; Glover, A.G. Microbial-Tubeworm Associations in a 440 Million Year Old Hydrothermal Vent Community. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 2018, 285. [CrossRef]

- Dodd, M.S.; Papineau, D.; Grenne, T.; Slack, J.F.; Rittner, M.; Pirajno, F.; O’Neil, J.; Little, C.T.S. Evidence for Early Life in Earth’s Oldest Hydrothermal Vent Precipitates. Nature 2017, 543, 60–64. [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, S.; Nishizawa, M.; Miyazaki, J.; Shibuya, T.; Ueno, Y.; Takai, K. Recycled Archean Sulfur in the Mantle Wedge of the Mariana Forearc and Microbial Sulfate Reduction within an Extremely Alkaline Serpentine Seamount. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2018, 491, 109–120. [CrossRef]

- Tosca, N.J.; Tutolo, B.M. Hydrothermal Vent Fluid-Seawater Mixing and the Origins of Archean Iron Formation. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2023, 352, 51–68. [CrossRef]

- Bjerrum, C.J.; Canfield, D.E. Ocean Productivity before about 1.9 Gyr Ago Limited by Phosphorus Adsorption onto Iron Oxides. Nature 2002, 417, 159–162. [CrossRef]

- Martin, W.; Russell, M.J. On the Origin of Biochemistry at an Alkaline Hydrothermal Vent. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2007, 362, 1887–1926. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, X.; Wang, J.; Wei, H.; Zeng, Y.; Ahmed, M.S.; Mansour, A. Methane Emissions during Marine Environmental Perturbations before the End-Triassic Mass Extinction. Facies 2025, 71, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Mrnjavac, N.; Schwander, L.; Brabender, M.; Martin, W.F. Chemical Antiquity in Metabolism. Acc Chem Res 2024, 57, 2267–2278. [CrossRef]

- Bae, H.S.; Morrison, E.; Chanton, J.P.; Ogram, A. Methanogens Are Major Contributors to Nitrogen Fixation in Soils of the Florida Everglades. Appl Environ Microbiol 2018, 84. [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.N.; Ji, S.; Kaçar, B.; Anbar, A.D.; Seyfried, W.E. Transition Metals in Alkaline Lost City Vent Fluids Are Sufficient for Early-Life Metabolisms. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2024, 385, 61–73. [CrossRef]

- Noffke, N.; Christian, D.; Wacey, D.; Hazen, R.M. Microbially Induced Sedimentary Structures Recording an Ancient Ecosystem in the ca. 3.48 Billion-Year-Old Dresser Formation, Pilbara, Western Australia. Astrobiology 2013, 13, 1103–1124. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Preciado, A.; Saghai, A.; Moreira, D.; Zivanovic, Y.; Dschamps, P.; Lopez-Garcia, P. Functional Shifts in Microbial Mats Recapitulate Early Earth Metabolic Transitions. Nat Ecol Evol 2018, 2, 1700–1708. [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.G.; Fowler, C.M.R. Archaean Metabolic Evolution of Microbial Mats. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 1999, 266, 2375–2382. [CrossRef]

- Blank, C.E.; SÁnchez-Baracaldo, P. Timing of Morphological and Ecological Innovations in the Cyanobacteria - A Key to Understanding the Rise in Atmospheric Oxygen. Geobiology 2010, 8, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Knoll, A.H.; Nowak, M.A. The Timetable of Evolution. Sci Adv 2017, 3. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, T.L.; Bryant, D.A.; Macalady, J.L. The Role of Biology in Planetary Evolution: Cyanobacterial Primary Production in Low-Oxygen Proterozoic Oceans. Environ Microbiol 2016, 18, 325–340. [CrossRef]

- Noffke, N.; Gerdes, G.; Klenke, T.; Krumbein, W.E. Microbially Induced Sedimentary Structures: A New Category within the Classification of Primary Sedimentary Structures. Journal of Sedimentary Research 2001, 71, 649–656. [CrossRef]

- Dupraz, C.; Reid, P.R.; Braissant, O.; Decho, A.W.; Normal, S.R.; Visscher, P.T. Processes of Carbonate Precipitation in Modern Microbial Mats. Earth Sci Rev 2009, 96, 141–162. [CrossRef]

- Allwood, A.C.; Walter, M.R.; Kamber, B.S.; Marshall, C.P.; Burch, I.W. Stromatolite Reef from the Early Archaean Era of Australia. Nature 2006, 441, 714–718. [CrossRef]

- Allwood, A.C.; Walter, M.R.; Burch, I.W.; Kamber, B.S. 3.43 Billion-Year-Old Stromatolite Reef from the Pilbara Craton of Western Australia: Ecosystem-Scale Insights to Early Life on Earth. Precambrian Res 2007, 158, 198–227. [CrossRef]

- Nutman, A.P.; Bennett, V.C.; Friend, C.R.L.; Van Kranendonk, M.J.; Chivas, A.R. Rapid Emergence of Life Shown by Discovery of 3,700-Million-Year-Old Microbial Structures. Nature 2016 537:7621 2016, 537, 535–538. [CrossRef]

- Van Kranendonk, M.J.; Nutman, A.P.; Friend, C.R.L.; Bennett, V.C. A Review of 3.7 Ga Stromatolites from the Isua Supracrustal Belt, West Greenland. Earth Sci Rev 2025, 262, 105034. [CrossRef]

- Allwood, A.C.; Rosing, M.T.; Flannery, D.T.; Hurowitz, J.A.; Heirwegh, C.M. Reassessing Evidence of Life in 3,700-Million-Year-Old Rocks of Greenland. Nature 2018, 563, 241–244. [CrossRef]

- Allwood, A.C.; Grotzinger, J.P.; Knoll, A.H.; Burch, I.W.; Anderson, M.S.; Coleman, M.L.; Kanik, I. Controls on Development and Diversity of Early Archean Stromatolites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106, 9548–9555. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Tajika, E.; Ozaki, K. Biogeochemical Transformations after the Emergence of Oxygenic Photosynthesis and Conditions for the First Rise of Atmospheric Oxygen. Geobiology 2023, 21, 537–555. [CrossRef]

- Anbar, A.D. Oceans. Elements and Evolution. 2008, 322, 1481–1483, doi:doi:10.1126/science.1163100.

- Mukherjee, I.; Large, R.R.; Corkrey, R.; Danyushevsky, L. V. The Boring Billion, a Slingshot for Complex Life on Earth. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Stott, L.D.; Harazin, K.M.; Quintana Krupinski, N.B. Hydrothermal Carbon Release to the Ocean and Atmosphere from the Eastern Equatorial Pacific during the Last Glacial Termination. Environmental Research Letters 2019, 14. [CrossRef]

- Buffett, B.A. Clathrate Hydrates. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 2000, 28, 477–507. [CrossRef]

- Huard, D.J.E.; Johnson, A.M.; Fan, Z.; Kenney, L.G.; Xu, M.; Drori, R.; Gumbart, J.C.; Dai, S.; Lieberman, R.L.; Glass, J.B. Molecular Basis for Inhibition of Methane Clathrate Growth by a Deep Subsurface Bacterial Protein. PNAS Nexus 2023, 2. [CrossRef]

- Weitemeyer, K.A.; Buffett, B.A. Accumulation and Release of Methane from Clathrates below the Laurentide and Cordilleran Ice Sheets. Glob Planet Change 2006, 53, 176–187. [CrossRef]

- Petryshyn, V.A.; Greene, S.E.; Farnsworth, A.; Lunt, D.J.; Kelley, A.; Gammariello, R.; Ibarra, Y.; Bottjer, D.J.; Tripati, A.; Corsetti, F.A. The Role of Temperature in the Initiation of the End-Triassic Mass Extinction. Earth Sci Rev 2020, 208, 103266. [CrossRef]

- Brand, U.; Blamey, N.; Garbelli, C.; Griesshaber, E.; Posenato, R.; Angiolini, L.; Azmy, K.; Farabegoli, E.; Came, R. Methane Hydrate: Killer Cause of Earth’s Greatest Mass Extinction. Palaeoworld 2016, 25, 496–507. [CrossRef]

- Burgess, S.D.; Black, B.A. The Anatomy and Lethality of the Siberian Traps Large Igneous Province. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 2025, 53, 567–594. doi:10.1146/ANNUREV-EARTH-040722-105544/CITE/REFWORKS. [CrossRef]

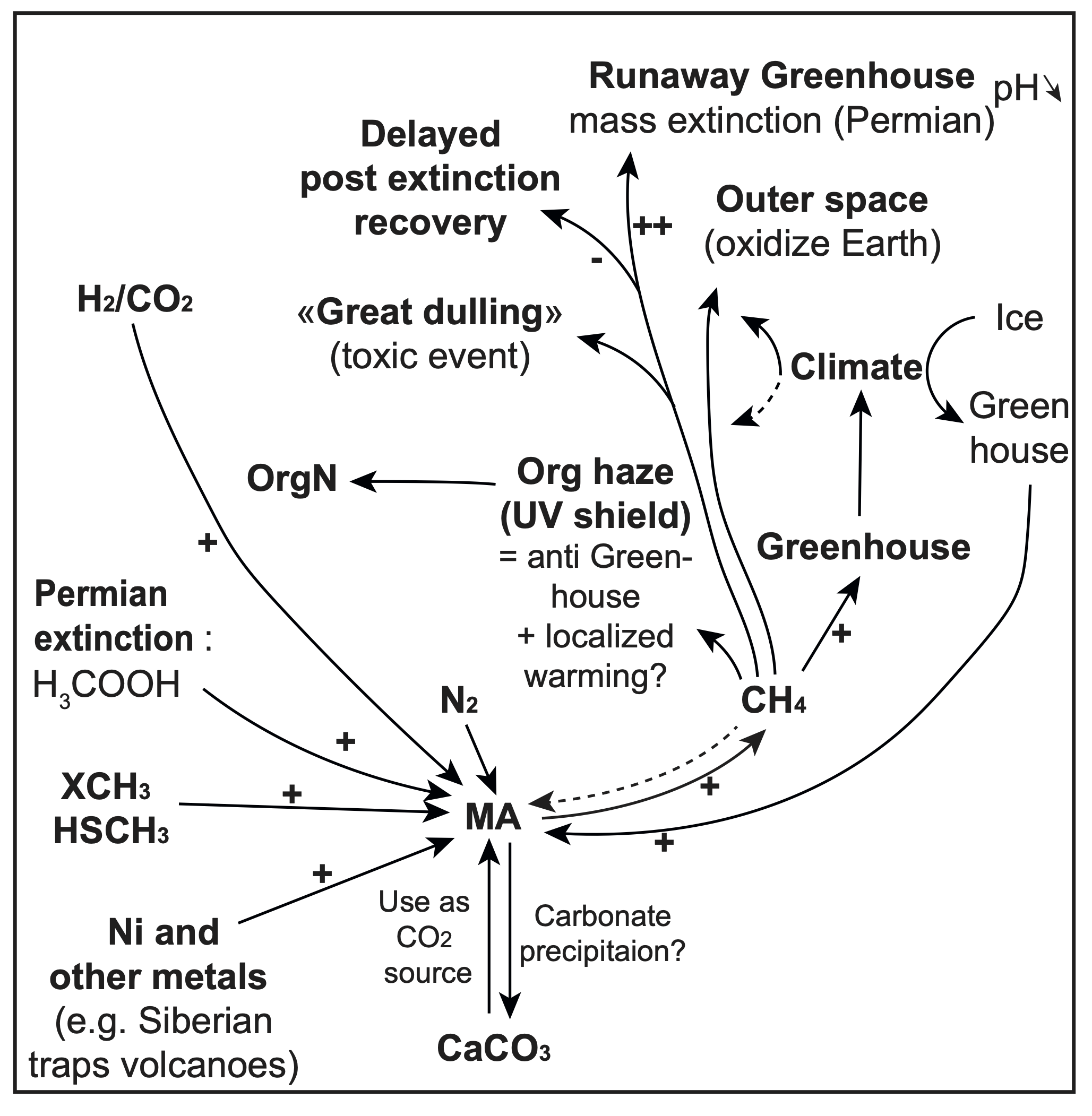

- Rothman, D.H.; Fournier, G.P.; French, K.L.; Alm, E.J.; Boyle, E.A.; Cao, C.; Summons, R.E. Methanogenic Burst in the End-Permian Carbon Cycle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 5462–5467. [CrossRef]

- Fournier, G.P.; Gogarten, J.P. Evolution of Acetoclastic Methanogenesis in Methanosarcina via Horizontal Gene Transfer from Cellulolytic Clostridia. J Bacteriol 2008, 190, 1124–1127. [CrossRef]

- Strock, K.E.; Krewson, R.B.; Hayes, N.M.; Deemer, B.R. Oxidation Is a Potentially Significant Methane Sink in Land-Terminating Glacial Runoff. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Liu, D.; Yang, H. Microbes in Mass Extinction: An Accomplice or a Savior? Natl Sci Rev 2023, 11, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lau, K. V.; Maher, K.; Altiner, D.; Kelley, B.M.; Kump, L.R.; Lehrmann, D.J.; Silva-Tamayo, J.C.; Weaver, K.L.; Yu, M.; Payne, J.L. Marine Anoxia and Delayed Earth System Recovery after the End-Permian Extinction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, 2360–2365. https://doi.org/10.1073/PNAS.1515080113;WEBSITE:WEBSITE:PNAS-SITE;WGROUP:STRING:PUBLICATION. [CrossRef]

- Mata, S.A.; Bottjer, D.J. Microbes and Mass Extinctions: Paleoenvironmental Distribution of Microbialites during Times of Biotic Crisis. Geobiology 2012, 10, 3–24. [CrossRef]

- Shubert, J.; Bottjer, D.J. Early Triassic Stromatolites as Post-Mass Extinction Disaster Forms | Geology | GeoScienceWorld. Geology 1992, 10, 883–886.

- Kirton, J.M.C.; Woods, A.D. Stromatolites from the Lower Triassic Virgin Limestone at Blue Diamond, NV USA: The Role of Dysoxia, Enhanced Calcification and Nutrient Availability in the Growth of Post-Extinction Microbialites. Glob Planet Change 2021, 198, 103429. [CrossRef]

- Baud, A.; Cirilli, S.; Marcoux, J. BIOTIC RESPONSE TO MASS EXTINCTION: THE LOWERMOST TRIASSIC MICROBIALITES.

- Vennin, E.; Olivier, N.; Brayard, A.; Bour, I.; Thomazo, C.; Escarguel, G.; Fara, E.; Bylund, K.G.; Jenks, J.F.; Stephen, D.A.; et al. Microbial Deposits in the Aftermath of the End-Permian Mass Extinction: A Diverging Case from the Mineral Mountains (Utah, USA). Sedimentology 2015, 62, 753–792. [CrossRef]

- Schobben, M.; Stebbins, A.; Ghaderi, A.; Strauss, H.; Korn, D.; Korte, C. Flourishing Ocean Drives the End-Permian Marine Mass Extinction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, 10298–10303. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Chen, Z.Q.; Fang, Y.; Pei, Y.; Yang, H.; Ogg, J. A Permian-Triassic Boundary Microbialite Deposit from the Eastern Yangtze Platform (Jiangxi Province, South China): Geobiologic Features, Ecosystem Composition and Redox Conditions. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 2017, 486, 58–73. [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Kump, L.R.; Wang, Y.; Tong, J.; Arthur, M.A.; Yang, H.; Huang, J.; Yin, H.; Xie, S. Isotopic Evidence for an Anomalously Low Oceanic Sulfate Concentration Following End-Permian Mass Extinction. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2010, 300, 101–111. [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, P.M.; Harris, M.T. Microbialite Resurgence after the Late Ordovician Extinction. Nature 2004, 430, 75–78. [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Aretz, M.; Chen, J.; Webb, G.E.; Wang, X. Global Microbial Carbonate Proliferation after the End-Devonian Mass Extinction: Mainly Controlled by Demise of Skeletal Bioconstructors. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Whitman, W.B. Metabolic, Phylogenetic, and Ecological Diversity of the Methanogenic Archaea. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008, 1125, 171–189. [CrossRef]

- Ehhalt, D.H. The Atmospheric Cycle of Methane. Tellus A: Dynamic Meteorology and Oceanography 1974, 26, 58. [CrossRef]

- Skeie, R.B.; Hodnebrog, Ø.; Myhre, G. Trends in Atmospheric Methane Concentrations since 1990 Were Driven and Modified by Anthropogenic Emissions. Commun Earth Environ 2023, 4, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Veron, J.E.N.; Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Lenton, T.M.; Lough, J.M.; Obura, D.O.; Pearce-Kelly, P.; Sheppard, C.R.C.; Spalding, M.; Stafford-Smith, M.G.; Rogers, A.D. The Coral Reef Crisis: The Critical Importance of .

- Ehleringer, J.R.; Cerling, T.E. Atmospheric CO2 and the Ratio of Intercellular to Ambient CO2 Concentrations in Plants. Tree Physiol 1993, 15, 105–111. [CrossRef]

- Dlugokencky, E.J.; Nisbet, E.G.; Fisher, R.; Lowry, D. Global Atmospheric Methane: Budget, Changes and Dangers. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2011, 369, 2058–2072. [CrossRef]

- Visscher, P.T.; Stolz, J.F. Microbial Mats as Bioreactors: Populations, Processes, and Products. Paleogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 2005, 1, 87–100. [CrossRef]

- Veiga, M.C.; Jain, M.K.; Wu, W.M.; Hollingsworth, R.I.; Zeikus, J.G. Composition and Role of Extracellular Polymers in Methanogenic Granules. Appl Environ Microbiol 1997, 63, 403–407. [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Yang, Y.Y. Microbially Induced Carbonate Precipitation via Methanogenesis Pathway by a Microbial Consortium Enriched from Activated Anaerobic Sludge. J Appl Microbiol 2021, 131, 236–256. [CrossRef]

- Sowers, K.R.; Baron, S.F.; Ferry, J.G. Methanosarcina Acetivorans Sp. Nov., an Acetotrophic Methane-Producing Bacterium Isolated from Marine Sediments . Appl Environ Microbiol 1984, 47, 971–978. [CrossRef]

- Loyd, S.J.; Marissa N. Smirnoff Progressive Formation of Authigenic Carbonate with Depth in Siliciclastic Marine Sediments Including Substantial Formation in Sediments Experiencing. Chem Geol 2022, 120775. [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, S.; Farag, I.F.; Zhao, R.; Christman, G.D.; Prouty, N.G.; Biddle, J.F. Expanding the Repertoire of Electron Acceptors for the Anaerobic Oxidation of Methane in Carbonates in the Atlantic and Pacific Ocean. ISME J 2021, 2523–2536. [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Wei, G.; Xian, H.; Zhu, J.; Xu, Y.G. Methanogen-Mediated Precipitation of Mn Carbonates at the Expense of Mn Oxides. Geophys Res Lett 2024, 51. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Arenas, P.J.; Latisnere-Barragán, H.; García-Maldonado, J.Q.; López-Cortés, A. Highly Diverse–Low Abundance Methanogenic Communities in Hypersaline Microbial Mats of Guerrero Negro B.C.S., Assessed through Microcosm Experiments. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0303004. [CrossRef]

- Oremland, R.S.; Polcin, S. Methanogenesis and Sulfate Reduction: Competitive and Noncompetitive Substrates in Estuarine Sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 1982, 44, 1270. [CrossRef]

- Mitterer, R.M. Methanogenesis and Sulfate Reduction in Marine Sediments: A New Model. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2010, 295, 358–366. [CrossRef]

- Vogt, J.C.; Abed, R.M.M.; Albach, D.C.; Palinska, K.A. Bacterial and Archaeal Diversity in Hypersaline Cyanobacterial Mats Along a Transect in the Intertidal Flats of the Sultanate of Oman. Microb Ecol 2018, 75, 331–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00248-017-1040-9/FIGURES/6. [CrossRef]

- Visscher, P. Cellular Origin, Life in Extreme Habitats and Astrobiology ; 2010; Vol. 14;.

- Visscher, P.T.; Taylor, B.F.; Kiene, R.P. Microbial Consumption of Dimethyl Sulfide and Methanethiol in Coastal Marine Sediments. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 1995, 18, 145–154. [CrossRef]

- Visscher, P.T.; Reid, R.P.; Bebout, B.M.; Hoeft, S.E.; Macintyre, I.G.; Thompson, J.A. Formation of Lithified Micritic Laminae in Modern Marine Stromatolites (Bahamas); the Role of Sulfur Cycling. American Mineralogist 1998, 83, 1482–1493. [CrossRef]

- Djokic, T.; VanKranendonk, M.J.; Campbel, K.A.; Walter, M.R.; Ward, C.R. Earliest Signs of Life on Land Preserved in ca. 3.5 Ga Hot Spring Deposits. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, L.K.; Dupraz, C.; Buckley, D.H.; Spear, J.R.; Pace, N.R.; Visscher, P.T. Microbial Species Richness and Metabolic Activities in Hypersaline Microbial Mats: Insight into Biosignature Formation Through Lithification. https://home.liebertpub.com/ast 2009, 9, 861–874. [CrossRef]

- Walter, M.R.; Heys, G.R. Links between the Rise of the Metazoa and the Decline of Stromatolites. Precambrian Res 1985, 29, 149–174. [CrossRef]

- Hohl, S. V.; Bian, X.; Viehmann, S.; Yang, S.C.; Raad, R.J.; Meister, P.; John, S.G. A Novel Biomarker for Deep-Time Methanogenesis – Perspectives from Nickel Isotope Fractionation in Modern Microbialites. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2025, 666, 119492. [CrossRef]

- Coffey, J.M.; Flannery, D.T.; Walter, M.R.; George, S.C. Sedimentology, Stratigraphy and Geochemistry of a Stromatolite Biofacies in the 2.72 Ga Tumbiana Formation, Fortescue Group, Western Australia. Precambrian Res 2013, 236, 282–296. [CrossRef]

- Scheller, S.; Goenrich, M.; Thauer, R.K.; Jaun, B. Methyl-Coenzyme M Reductase from Methanogenic Archaea: Isotope Effects on the Formation and Anaerobic Oxidation of Methane. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Van de Vossenberg, J.L.C.M.; Driessen, A.J.M.; Konings, W.N. The Essence of Being Extremophilic: The Role of the Unique Archaeal Membrane Lipids. Extremophiles 1998, 2, 163–170. [CrossRef]

- Myers, T.; Dykstra, C.M. Teaching Old Dogs New Tricks: Genetic Engineering Methanogens. Appl Environ Microbiol 2024, 90. [CrossRef]

- Conrad, R. Methane Production in Soil Environments—Anaerobic Biogeochemistry and Microbial Life between Flooding and Desiccation. Microorganisms 2020, Vol. 8, Page 881 2020, 8, 881. [CrossRef]

- Horne, A.J.; Lessner, D.J. Assessment of the Oxidant Tolerance of Methanosarcina Acetivorans. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2013, 343, 13–19. [CrossRef]

- Decho, A.W.; Norman, R.S.; Visscher, P.T. Quorum Sensing in Natural Environments: Emerging Views from Microbial Mats. Trends Microbiol 2010, 18, 73–80. [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Cruz, S.; Cremers, G.; van Alen, T.A.; Op den Camp, H.J.M.; Jetten, M.S.M.; Rasigraf, O.; Vaksmaa, A. Response of the Anaerobic Methanotroph “ Candidatus Methanoperedens Nitroreducens” to Oxygen Stress. Appl Environ Microbiol 2018, 84. [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, C.P.; Duarte, M.S.; Pereira, M.A.; Stams, A.J.M.; Cavaleiro, A.J. Facultative Anaerobic Bacteria Enable Syntrophic Fatty Acids Degradation under Micro-Aerobic Conditions. Bioresour Technol 2025, 417, 131829. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-C.; Chong, S.+; Zhao, X.-M.; Du, J.-X.; Zou, L.; Yong, Y.-C. Unnatural Direct Interspecies Electron Transfer Enabled by Living Cell-Cell Click Chemistry. Angewandte Chemie 2024, 136, e202402318. [CrossRef]

- Formisano, V.; Atreya, S.; Encrenaz, T.; Ignatiev, N.; Giuranna, M. Detection of Methane in the Atmosphere of Mars. Science (1979) 2004, 306, 1758–1761. [CrossRef]

- Waite, J.H.; Combi, M.R.; Ip, W.; Thomas, E.C.; McNutt, R.L.; Kasprzak, W.; Yelle, R.; Luhmann, J.; Niemann, H.; Gell, D.; et al. Cassini Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer: Enceladus Plume Composition and Structure. Science 2006, 311, 1419–1422. [CrossRef]

- Niemann, H.B.; Atreya, S.K.; Bauer, S.J.; Carignan, G.R.; Demick, J.E.; Frost, R.L.; Gautier, D.; Haberman, J.A.; Harpold, D.N.; Hunten, D.M.; et al. The Abundances of Constituents of Titan’s Atmosphere from the GCMS Instrument on the Huygens Probe. Nature 2005, 438, 779–784. [CrossRef]

- Mickol, R.L.; Takagi, Y.A.; Kral, T.A. Survival of Non-Psychrophilic Methanogens Exposed to Martian Diurnal and 48-h Temperature Cycles. Planet Space Sci 2018, 157, 63–71. [CrossRef]

- Hurowitz, J.A.; Catling, D.C.; Fischer, W.W. High Carbonate Alkalinity Lakes on Mars and Their Potential Role in an Origin of Life Beyond Earth LAKES ON MARS. ElEmEnts 2023, 19, 37–44. [CrossRef]

- Yung, Y.L.; Chen, P.; Nealson, K.; Atreya, S.; Beckett, P.; Blank, J.G.; Ehlmann, B.; Eiler, J.; Etiope, G.; Ferry, J.G.; et al. Methane on Mars and Habitability: Challenges and Responses. Astrobiology 2018, 18, 1221–1242. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).