1. Introduction

Stroke was the third leading cause of disability and death worldwide as per the World Health Organization, with an estimated 93.8 million cases and a global burden of disease of 160 million Disability-Adjusted Life Years in 2021 [

1]. Survivors often experience persistent disability associated with neurological deficits that significantly impair motor abilities, independence in activities of daily living, and overall quality of life. The estimated cost of stroke globally is greater than US

$890 billion or 0.66% of the global gross domestic product, with a majority of the global stroke burden (87% of deaths and 89% of disability-adjusted life-years lost) localized to lower-income and lower-middle-income countries [

2]. As the population ages, the absolute number of stroke survivors and stroke-related disability continues to increase in the setting of stroke risk factor burden such as metabolic, environmental and behavioral risks.

Rehabilitation plays a central role in mitigating disability and promoting functional recovery across phases of care following a stroke. Stroke rehabilitation focuses on minimizing disability, increasing functional independence and maximizing both physical and mental recovery. A patient’s capacity and stage of stroke recovery (acute, subacute or chronic) influence the intensity and modality of rehabilitation technique [

3]. Traditional interventions in stroke rehabilitation include physical therapy and occupational therapy. Physical therapy is traditionally focused on improving physical strength, balance, mobility and coordination through task-oriented exercises, while occupational therapy aims to improve fine motor skills, performance of activities of daily living and adaptive strategies. Traditional rehabilitation strategies require repeated practice and a relatively high intensity compared to the patient’s functional ability. The limitations of traditional rehabilitation strategies include limited functional improvement beyond the initial phases of therapy, intensive demands that may be exhausting or not feasible for some patients, limited access to appropriate facilities and therapists in resource-poor settings, and decreased patient engagement with therapy due to repetitive tasks. Adjunctive and emerging rehabilitation technologies are aiding traditional techniques in patient recovery. These technologies include robotic devices, virtual reality (VR), brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) and telerehabilitation. This review focuses on the role of the IoMT in the rehabilitation of stroke patients, providing descriptions of current technologies and their interface with neurorehabilitation development.

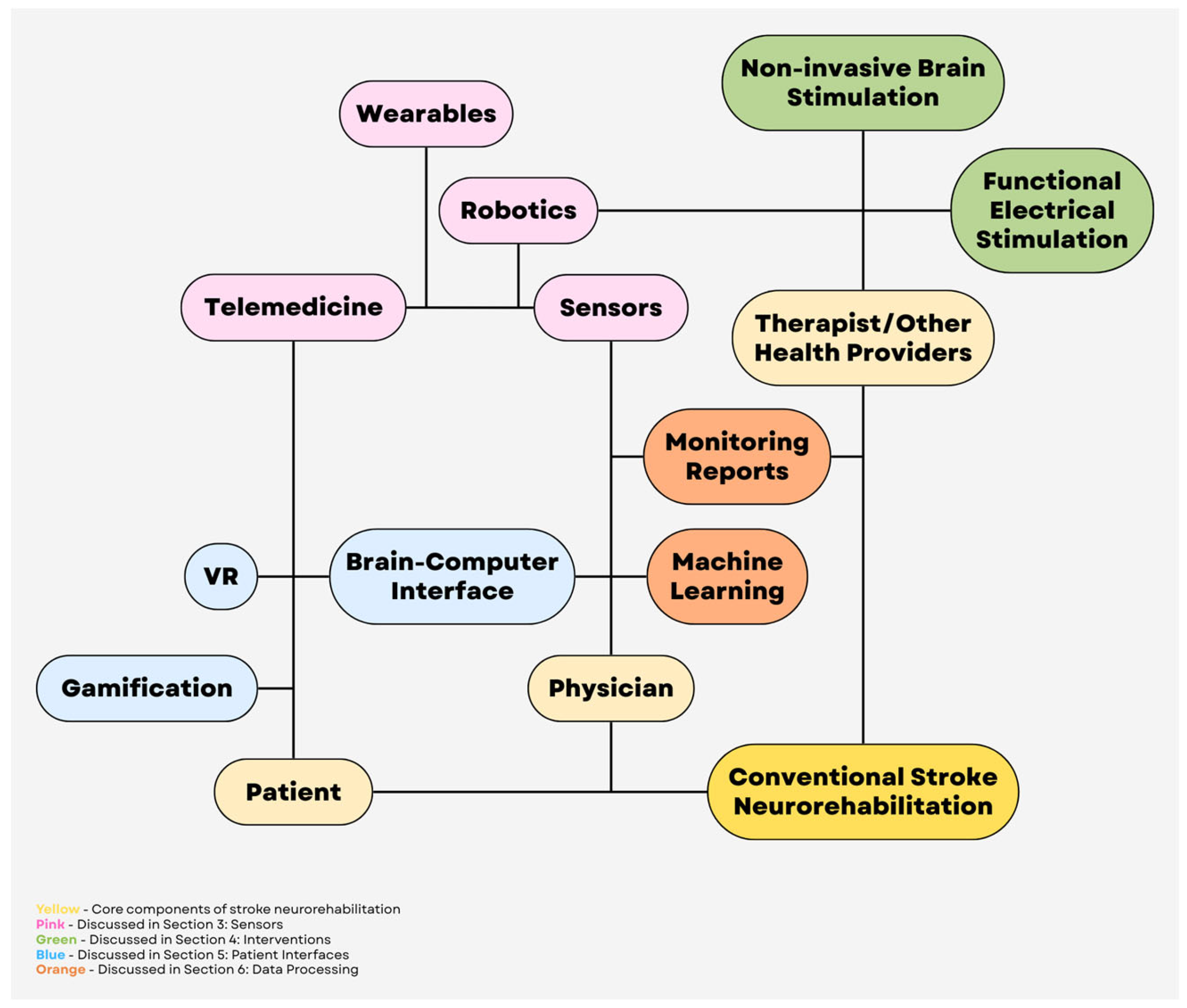

2. The Internet of Medical Things

The Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) refers to a network of medical devices, software applications and health systems that are connected through the internet to collect, share, and analyze health data. It enables a health system to connect multiple devices, such as wearable sensors, medical examination monitors, and hospital equipment and infrastructure for creating a digital network. The IoMT has been utilized in emerging areas of healthcare such as smart hospital systems, remote health monitoring, infectious disease tracking, etc [

4]. The IoMT has a layered architecture, with a perception layer composed of sensors and physical devices, a network layer that provides connectivity, a processing layer that analyzes and stores data, and an application layer that delivers information to end-users such as doctors and patients [

5]. Medical devices include wearables, such as fitness trackers, smartwatches, electrocardiograms (ECGs), etc., and implantable devices, such as pacemakers or insulin pumps. Home monitoring systems often utilize glucose monitors, oxygen sensors, ECGs, blood pressure cuffs, etc. Hospital equipment includes infusion pumps, ventilators, and imaging systems that communicate with hospital databases and patients’ electronic health records (EHRs). Medical devices collect patient data, such as heart rate or blood pressure, that is sent to healthcare systems or servers via the internet, artificial intelligence (AI) or algorithms detect problems or trends and then alert patients or healthcare providers if the patient may need further assessment.

Figure 1 shows a schematic of the IoMT.

3. Sensors

Within the IoMT, sensors constitute the foundational “perception layer” that enables continuous, multi-scale characterization of stroke survivors’ impairments, activity patterns, and physiologic status across inpatient, outpatient, and home environments [

6,

7,

8]. Cameras, wearable devices, and robot-embedded sensors connect to network and application layers, generating high-frequency, multimodal data streams (kinematics, kinetics, physiologic signals, and user interaction metrics) that can be encrypted, aggregated in the cloud, analyzed using advanced analytics or machine learning, and used to inform individualized rehabilitation plans and adaptive interventions [

6].

3.1. Telemedicine and Diagnostic Use of Videography

High-resolution video integrated into telemedicine platforms has progressed beyond simple videoconferencing to enable structured, quantifiable assessment and therapy delivery. Contemporary telerehabilitation systems can combine synchronous audio–video communication with structured motor or cognitive tasks and cloud-based analytics to approximate or augment in-person examinations [

9,

10]. In subacute stroke, a post-discharge telerehabilitation program incorporating a personalized rehabilitation plan, regular video consultations, and health education demonstrated superior functional recovery, such as improved activities of daily living, compared with usual care in a randomized trial [

11]. Additionally, a multicenter randomized controlled non-inferiority trial found that a self-guided, AI-driven cognitive telerehabilitation program delivered via a mobile platform produced improvements across multiple cognitive measures and was not inferior to therapist-supervised cognitive rehabilitation [

10]. In longer-term post-stroke populations, home-based multidomain cognitive training delivered through a VR rehabilitation system has been associated with improvements in cognitive and mood-related outcomes and reduced caregiver burden [

12]. For motor rehabilitation, standard video can be paired with marker less computer-vision (pose-estimation) algorithms that track body landmarks to estimate joint angles and movement patterns, enabling remote scoring of gait and upper-limb task performance without dedicated motion-capture hardware [

13,

14]. When integrated with IoMT platforms that collect and manage the data, these systems support automated data upload, longitudinal tracking, and integration with the EHR [

6].

3.2. Wearable Sensors

Wearables, such as inertial measurement units (IMUs), pressure sensors, and surface electromyography (EMG) patches extend measurement beyond the clinic to capture real-world use of the paretic limb, gait quality, cardiovascular load, and engagement with daily activities [

7,

15,

16,

17]. Systematic reviews have shown that IMU-based systems can reliably quantify spatiotemporal gait parameters, upper-limb kinematics, and compensatory strategies in stroke survivors, with good agreement to laboratory motion-capture systems and clinical scales [

15,

17]. Recent studies integrate wearable sensors with machine-learning models to classify task performance, detect compensatory movement patterns, and estimate standardized clinical scores from free-living data, thereby enabling precision rehabilitation dosing and early identification of non-responders [

7,

16].

Within an IoMT architecture, wearable devices typically communicate with a smartphone or home gateway, which encrypts and transmits data to cloud services for storage and analysis [

6,

16]. This infrastructure enables near real-time monitoring and automated alerts, such as fall detection, abnormal heart-rate responses to exertion, or sudden reductions in limb use, which can prompt timely outreach or earlier follow-up [

17,

18]. Wearables can also support stroke rehabilitation by quantifying therapy volume and detecting avoidance of the affected limb even when clinic performance appears adequate [

16,

18,

19]. However, many systems continue to face challenges, including limited battery life and comfort, inconsistent user adherence, lack of validated cut-offs linked to functional outcomes, and fragmented data standards that complicate integration with hospital information systems [

6,

7,

18,

19]. Addressing these barriers is essential for transitioning wearable technology from research prototypes into routine stroke rehabilitation.

3.3. Sensors in Robotic Systems

Rehabilitation robots are equipped with a range of sensors, incorporating joint encoders, force and load sensors, inertial sensors, and, in some cases, EMG or neural interfaces [

20,

21,

22]. These sensors enable precise measurement of interaction forces, movement trajectories, and patient participation, supporting both real-time adaptive assistance and objective outcome tracking [

20,

21]. IoMT-enabled robots can transmit high-resolution movement and force data to secure cloud platforms, providing remote access to session frequency, intensity, and progression, and enabling therapists or engineers to adjust parameters without onsite presence [

22,

23]. Recent studies support robot-assisted approaches that incorporate enhanced feedback. For example, a prospective cohort study of a mirror-therapy rehabilitation robot for both upper and lower limbs after stroke found that robot-assisted training was associated with improvements in motor and functional outcomes compared with conventional rehabilitation [

24]. Hybrid approaches that combine robot-assisted practice with brain–computer interfaces (BCI), noninvasive neuromodulation, or functional electrical stimulation (FES) may be particularly effective, as they can more directly link a patient’s movement intent to timed stimulation and the resulting movement, which is thought to better promote use-dependent neuroplasticity [

8,

20,

23,

25].

4. Interventions

In addition to passive monitoring, the IoMT offers an infrastructure for delivering and coordinating technology-enabled neuromodulatory and motor interventions, including non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS), functional electrical stimulation (FES), and robot-assisted therapy. A common trend across these modalities is the shift toward sensor-driven, performance-adaptive closed-loop systems in which treatment parameters are individualized using patient-specific kinematics, physiologic signals, and adherence data collected in real time and analyzed within cloud-based platforms [

6,

8,

16].

4.1. Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation

NIBS, primarily repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), aims to modulate maladaptive network dynamics after stroke, such as interhemispheric imbalance, to enhance training-induced plasticity when paired with task-specific practice [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Recent research demonstrates modest but clinically relevant effects of rTMS on motor and selected cognitive outcomes, although substantial heterogeneity in effect sizes is observed due to driven by patient factors (stroke phase, baseline severity, lesion, or network integrity) and protocol parameters (site, frequency, intensity, timing relative to training) [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Evidence from meta-analyses suggests rTMS benefit is detectable across multiple protocols but remains sensitive to trial design and dosing, highlighting the need for adequately powered, mechanism-informed studies with standardized outcomes and synchronized behavioral training [

26,

27].

IoMT integration for NIBS is currently most advanced for home-based, remotely supervised-tDCS (RS-tDCS), where compact stimulators can upload session logs (e.g., delivered dose, impedance, and basic safety/tolerability data) and support adherence through tele-supervision and protocol safeguards [

30,

31,

32]. In post-stroke cognitive dysfunction, a randomized trial pairing home-based RS-tDCS with cognitive training demonstrated feasibility and safety, supporting the practicality of moving selected NIBS workflows outside the clinic [

30]. Because remote delivery shifts more responsibility to the patient/caregiver environment, standardized technology and safety procedures are essential and have been formalized in RS-tDCS protocol guidance [

31].

More broadly, IoMT systems can enhance NIBS delivery by digitizing session-level metadata, including dose, impedance, tolerability, and timing relative to training, and linking these data to contemporaneous performance and physiologic metrics obtained from wearables or rehabilitation robots [

6,

16,

20,

22,

23,

25]. This integration provides a clearer understanding of adherence and response over time and supports the development of closed-loop NIBS, in which stimulation scheduling or intensity is adjusted based on objective indicators such as daily activity, sleep patterns, plateauing task performance, or physiologic signs of fatigue inferred from movement quality and load [

16,

25].

4.2. Functional Electrical Stimulation

FES delivers patterned electrical stimulation to peripheral nerves or muscles to elicit or augment voluntary movements, such as peroneal-nerve stimulation for dorsiflexion during ambulation and upper-limb stimulation to support grasp-related tasks [

8,

33,

34]. Contemporary post-stroke FES systems include both open-loop (therapist- or patient-triggered) approaches and closed-loop paradigms that trigger stimulation using physiologic or intent signals such as surface EMG, kinematics, or BCI outputs [

33,

35,

36]. Systematic reviews of upper-limb FES report improvements in motor impairment and functional task outcomes across various device configurations, but highlight substantial heterogeneity in stimulation dosing, triggering strategies, comparators, and outcome measures which complicate generalizability and protocol standardization [

33,

37]. Peroneal-nerve FES has demonstrated evidence of improving gait outcomes when combined with physiotherapy, although effect sizes vary across studies [

34].

IoMT-enabled FES devices can record stimulation parameters, such as pulse amplitude, width, and frequency, as well as usage patterns and, in some cases, surface EMG or kinematic signals, which are uploaded for remote monitoring and titration [

7,

8]. Prototypes that integrate EMG sensors, FES, and virtual-reality environments illustrate closed-loop architectures in which stimulation timing and task difficulty are adapted in real time based performance metrics [

8,

20]. This approach enables personalized progression of task complexity, automated adherence tracking, and timely clinician intervention when usage or response declines. However, practical barriers remain, including device complexity and the training burden for patients and caregivers.

4.3. Robotic Systems

Robot-assisted rehabilitation enables high-intensity, repeatable, task-specific practice while providing objective quantification of kinematics, kinetics, and active participation through embedded sensors [

20,

21]. IoMT-connected robots can transmit session-level metrics, including frequency, repetitions, assistance levels, and trajectory and force profiles, to secure platforms to support remote supervision and longitudinal progression [

6,

22,

23]. A clinic-to-home feasibility framework using a planar rehabilitation robot demonstrates how structured remote programs can be implemented with minimal therapist oversight and regular performance logging [

9].

In addition to feasibility studies, a prospective cohort study of a mirror-therapy rehabilitation robot applied to both upper and lower limbs reported improvements in motor and functional outcomes compared with conventional rehabilitation, supporting the clinical plausibility of robotic paradigms that integrate augmented feedback with sensor-derived performance capture [

24]. Hybrid approaches that combine robotics with FES or NIBS are of particular interest because they can synchronize stimulation with specific phases of movement quantified by robot or wearable sensors. This design principle aims to strengthen use-dependent plasticity by coupling intent, stimulation, and executed movement [

8,

20,

25,

35].

5. Patient Interfaces

Although in-person assessment and care remain the gold standard of stroke neurorehabilitation, challenges regarding their accessibility persist, such as limited access to nearby rehabilitation providers, dose limitations of in-person sessions, and traveling difficulties–particularly for patients dealing with new neurological deficits [

38]. The advancement of telemedicine technology and implementation has allowed patients to have greater access to rehabilitation resources. Electronic interfaces help meet these challenges by streamlining the patient’s transition from initial hospitalization to outpatient or home rehabilitation, producing better access and continuity of care [

38]. Innovations like BCI, VR, and telerehabilitation present alternatives and supplementation to conventional stroke rehabilitation, allowing continuous monitoring without the constraints of space, and potentially provide more accurate measurements of functional metrics within the patient’s home environment [

39,

40,

41,

42]. In the following sections, this paper highlights the different approaches in neurorehabilitation underpinning these three innovations.

Research on stroke telerehabilitation has increased in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, during which in-person services were reduced or shut down entirely [

39,

41,

43]. Stroke telerehabilitation is the delivery of stroke therapy through remote communication methods, which may be synchronous, e.g. video conferencing, or asynchronous, e.g. watching a video within a phone application [

38,

39]. Most modalities involve some kind of guided therapeutic exercise, and services are targeted to improve motor or daily function, communication, depression, or stroke risk factors [

39,

44,

45]. Telerehabilitation can contain gamified elements [

38,

42]. For example, a clinician may select therapeutic exercises on a gaming console for the patient and monitor their completion during or after completion [

44]. The underlying approach behind gamification in neurorehabilitation is to activate dopaminergic pathways associated with the ventral striatum, the brain region responsible for reward processing and motivation, and thus promote a stroke therapy approach that is engaging, motivating, and easily accessible while still being highly intense and task-oriented [

38,

42,

46]. Telerehabilitation has been shown to improve post-stroke impairments, disability, and patient quality of life, while reducing depression in patient caregivers [

39]. Studies have shown similar or even better outcomes for patients receiving telerehabilitation compared to conventional stroke therapy [

38,

39,

40,

44,

45]. The major benefits posed by telerehabilitation are time- and cost-savings, especially for patients living in areas with limited healthcare access [

40].

Much like telerehabilitation, VR is a rapidly expanding field in stroke rehabilitative therapy. VR is a broad classification commonly divided into immersive and non-immersive modalities [

42]. Immersive VR is generally characterized by user interaction with a completely virtual environment, usually through a VR headset, while non-immersive VR generally presents the virtual environment on a monitor, with which the user interacts using a controller, as in gaming consoles [

42,

46]. VR is derived from video games, and as with telerehabilitation interventions, gamified elements are often seen [

46]. Studies primarily show benefits in upper extremity motor recovery, especially with immersive VR and in combination with conventional therapy [

38,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. A recent meta-analysis also found that VR game therapies were more effective than conventional therapy in improving cognitive ability, attention, mobility, and emotional state [

48].

Broadly speaking, stroke rehabilitation therapies aim to potentiate neuroplasticity with the goal of maximizing nervous system functions after brain injury [

8]. For example, motor rehabilitation in conventional stroke therapy may involve patients performing a core-stability exercise in order to strengthen and create new neural connections between the intent and the execution of such an exercise [

41]. Enhancing this neural rewiring by closing the “central-peripheral-central” loop of intent, execution, and feedback is the basis of BCI [

50]. In BCI, the patient is connected to an electroencephalogram (EEG) and is asked to attempt a task [

38]. As the patient thinks about this activity, their central nervous system is activated, generating neural activity linked to the intention of task performance [

51]. The EEG captures this neural activity, and the BCI reads the brain signals to provide the patient with some kind of feedback, which may be visual (an image of the task being completed), robotic (a device they wear which helps complete the task), or so on [

38]. This bypasses brain lesions that prevent stroke patients from activating their peripheral nervous system during task execution, and returning feedback to their central nervous system upon task completion [

38]. BCI is an emerging field that has applications in motor, cognitive, and emotional regulatory rehabilitation post-stroke [

52]. Studies have shown its effectiveness is comparative to conventional stroke therapy, especially for upper extremity motor functions measured by the Fugl-Meyer assessment [

38,

50,

53,

54]. There is also evidence that BCI can improve attention and other cognitive functions in stroke, although its use in cognitive rehabilitation is more well-studied in non-stroke populations, such as patients with attention deficit disorder [

38,

54]. BCI interventions are often linked to motor imagery, a neuroscience concept and therapy which promotes neuroplasticity by activating the motor cortex with the imagery of a motor task instead of motor execution [

38,

54]. With the advent of AI, integration of BCI with machine learning may improve neural activity decoding capabilities and allow BCI therapies to provide more tailored feedback to patients [

52].

6. Data Processing

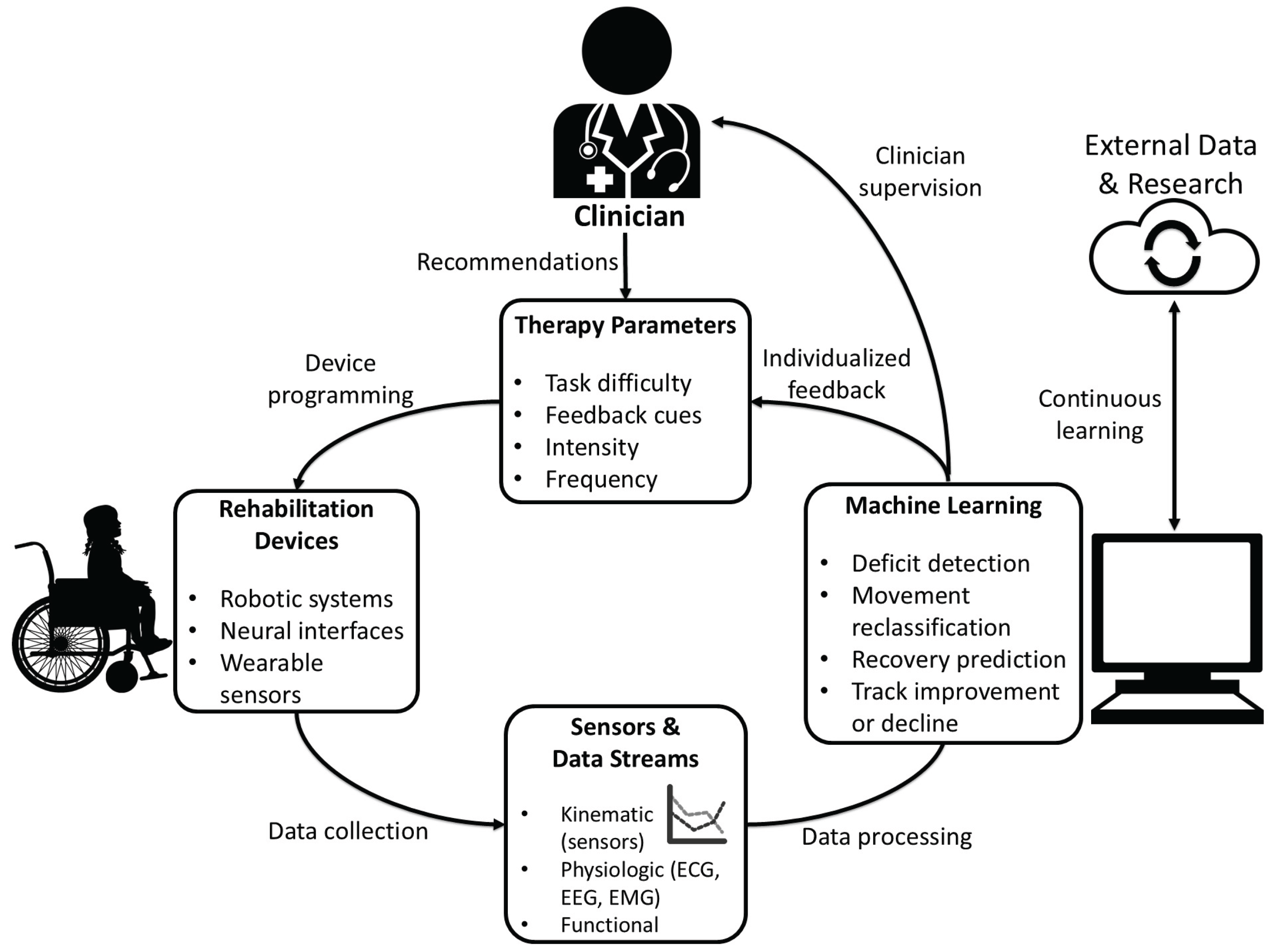

As rehabilitation technology has moved toward more data-driven care, the collection and interpretation of patient information have changed dramatically. One of the biggest shifts has been remote access to real-time physiological and biomechanical data. With information from inertial sensors, gyroscopes, accelerometers, and pressure sensors, clinicians can evaluate gait and physical progress in the rehabilitative phase [

7]. Additionally, physiological data can also be monitored through the use of EMG, ECG, and EEG to better assess recovery. Several studies have shown that remote sensors allow for effective monitoring of therapeutic exercises and functional performance outside of the clinic [

7,

55]. This is especially important for patients with neurological conditions, where progress often depends on regular monitoring and accurate feedback [

56].

Remote monitoring also allows earlier detection of problems. A stroke patient with subtle changes in range of motion or tone can be detected with remote monitoring long before an in-person appointment [

56]. Remote activity-sensing aftercare programs have already demonstrated the value of continuous monitoring [

57]. As rehabilitation devices such as robotic systems, BCI-controlled interfaces, and sensor-embedded orthotics become more complex and widespread, remote clinician oversight can improve efficiency, safety and continuity of care. However, storing and processing remote data comes with many challenges. Different manufacturers store information in different formats, adding to the complex issues facing cybersecurity [

58]. Furthermore, medical devices require approval by the FDA, and all patient data must be protected as outlined by HIPAA and state privacy laws [

58]. Transmitting and integrating the information to the hospital or clinic also requires confidentiality and security [

59].

Machine learning (ML) is a major contributor to rehabilitation data processing as it helps clinicians make sense of the enormous amount of data from patients. Some of the common supervised learning algorithms used in ML include support vector machine, decision tree, random forest, artificial neural network [

7]. By using algorithms that can detect complex patterns across large datasets, ML models can assist clinicians in predicting recovery trajectories, personalizing treatment plans, and identifying subtle markers of improvement or decline. In many cases, ML models can identify patterns in sensor and clinical data that humans would be unable to detect. For example, ML has been used to classify rehabilitation movements and evaluate movement quality using wearable sensors [

55]. ML models can also consistently detect proprioceptive deficits in stroke patients [

60]. Some studies also suggest they may help predict recovery patterns and, in certain cases, identify stroke subtypes [

60]. Similarly, models using robotic-assisted rehabilitation data have classified stroke severity with high accuracy [

61]. Therefore, ML may eventually have a diagnostic role to supplement current imaging techniques.

Another promising area is predictive modeling in neurorehabilitation. ML systems have already shown success in predicting early upper-limb recovery trajectories and functional outcomes after spinal cord injury rehabilitation [

62,

63]. Additionally, A study comparing COX regression (linear) models against ML-based (non-linear) models found the latter superior in predicting gait recovery following ischemic stroke [

64]. The additional information from ML systems may enable clinicians to better structure recovery schedules and personalize therapy goals.

However, there are many limitations. Datasets for neurorehabilitation patients are often small and highly individualized, making it harder for models to generalize information [

59]. Clinicians also need models that are easy to interpret, so the information can be used to improve patient outcomes [

59]. Without an understanding of why the algorithm suggests a certain recommendation, the clinician cannot safely adapt it into patient care. Ultimately, the goal is to combine multiple data streams including physiological, environmental, and behavioral data to assess a patient’s recovery. These systems also have the capability to continuously learn from new patients, gradually improving the effectiveness of machine assistance in neurorehabilitation (

Figure 2).

7. Case Studies of Integrated Systems

Advances in telemedicine, closed-loop neurorehabilitation, and AI are transforming recovery by enabling continuous, data-driven therapy that extends seamlessly from clinic to home.

7.1. Telemedicine and Virtual Rehabilitation Networks

Telemedicine and virtual rehabilitation networks have been particularly effective in expanding access to high-intensity rehabilitation beyond traditional hospital settings [

65]. For instance, the large phase III TRos/TR-2 Trial demonstrated improved upper-limb recovery in subacute stroke patients through a program delivering 70 minutes per day of home-based arm training, using games, exercises, and educational content over six to eight weeks [

66]. Another example, the six-month ACTIV Trial, utilized a hybrid approach combining minimal in-person visits with text and phone support, leading to significant improvements in physical function for participants who adhered to the program [

67]. The effectiveness of these virtual approaches is further highlighted by the VA Telehealth Programs, which include the Remote Patient Monitoring-Home Telehealth (RPM-HT) initiative to monitor post-stroke function and chronic risk factors, and the Telestroke Program, which provides real-time neurologist access for acute care in rural facilities [

68]. These systems collectively illustrate how virtual care can maintain continuity and effectively reduce geographic barriers to essential rehabilitation services.

7.2. Closed-Loop Systems for Motor Recovery

Closed-loop systems represent a significant leap in neurorehabilitation by integrating sensors, stimulators, and adaptive algorithms to provide real-time therapeutic adjustments. A primary example is the

BrainGate2 Trial, which utilizes a brain-computer interface (BCI) to convert motor intent directly into robotic arm movements. This technology enables individuals with paralysis to perform goal-directed actions, demonstrating the profound potential for neuroplastic motor restoration through direct neural engagement [

69,

70]

. Similarly, the MindMotion™ PRO System provides a CE-certified VR platform that uses motion capture and gamified feedback to reinforce correct movement patterns. Its closed-loop design is specifically engineered to adjust task difficulty continuously based on a patient's immediate performance, a feature that actively encourages neuroplastic adaptation. Clinical evaluations of the system have shown significant improvements in Fugl-Meyer Assessment scores and overall patient motivation [

71,

72,

73].

Together, these cases highlight how the delivery of real-time sensorimotor feedback can accelerate the recovery process while maintaining high levels of patient engagement.

7.3. Artificial Intelligence and Data-Driven Personalization

AI has become a cornerstone of modern neurorehabilitation by enabling the automated tailoring of therapy intensity, content, and progression. This shift toward data-driven personalization is exemplified by the AISN Trial, a multicenter study testing an AI-driven decision-support module within the RGS@home VR system. By personalizing task difficulty based on real-time performance, this AI optimization aims to significantly improve motor recovery compared to traditional methods [

74,

75]. Similarly, the AI Cognitive Telerehabilitation Trial utilized the AI-guided Zenicog® platform, demonstrating that automated systems can perform comparably to therapist-supervised cognitive training [

10].

Beyond software, AI-guided robotics such as the Ekso exoskeleton and IpsiHand device use machine learning to analyze EMG and EEG signals, allowing for highly individualized motor training by adjusting physical assistance levels in real time [

76,

77]. AI-enhanced VR systems like VRehab, NeuRRoVR, and MindMotion GO further support this trend by using multimodal sensors to modify task complexity dynamically and deliver automated feedback [

78,

79,

80]. This technological integration extends to AI-powered mobile applications, such as those developed by the University of Texas Health Houston for exercise coaching or iTalkBetter for language rehabilitation, which analyze movement and speech to provide immediate clinical guidance. Across all these domains, AI effectively increases therapy dosage, precision, and personalization, ensuring that rehabilitation is both intensive and uniquely suited to the patient’s needs.

7.4. Synergistic Integration

The future of rehabilitation lies in the synergistic integration of telemedicine, closed-loop devices, and AI into cohesive, end-to-end ecosystems. One such example is the Motor Recovery Ecosystem, which combines EMG-triggered FES wearables and motion sensors with AI engines to create an adaptive home-based environment. Monitored via telerehabilitation dashboards, this system continuously predicts recovery trajectories and dynamically adjusts exercise intensity, providing high-intensity retraining that blends independent practice with professional oversight [

56]. Similarly, the Cognitive Rehabilitation Ecosystem utilizes lightweight EEG headsets to monitor neural markers of attention and fatigue in real time. This allows a sophisticated AI engine to automatically adjust task complexity or trigger neurostimulation, such as tDCS, ensuring the patient remains in an optimal learning zone while neuropsychologists review analytics through a dedicated portal [

81,

82].

This data-driven approach extends to physical mobility through the Gait Rehabilitation Ecosystem, where wearable IMUs feed data into AI that modulates smart orthoses or exoskeletons. This provides immediate correction of gait asymmetry and enables remote physical therapy reviews, shifting the paradigm from episodic clinical visits to immediate, daily gait correction [

83]. Communication recovery is also being transformed by the Aphasia Rehabilitation Ecosystem, which integrates mobile technology with AI-driven natural language processing. This system monitors speech metrics like fluency and word retrieval in real time, immediately adjusting exercise difficulty while Speech-Language Pathologists review "speech heatmaps" to guide long-term progress [

84,

85].

Finally, the Chronic Pain Precision Ecosystem utilizes biosensors to detect early pain flare signatures. This allows predictive AI algorithms to trigger closed-loop neuromodulation, such as spinal cord stimulation or vagus nerve stimulation, before symptoms escalate. By allowing a telemedicine team of pain specialists to review weekly AI reports and refine medication protocols, these integrated ecosystems demonstrate how continuous data flow can deliver highly personalized, intensive therapy within the daily lives of patients [

86,

87].

8. Discussion

Stroke remains a leading global cause of long-term disability, causing substantial personal, social and economic burdens, with patients in under-resourced nations being most affected. Conventional rehabilitation remains the foundation for post-stroke recovery, but its effectiveness is often constrained by accessibility and long-term engagement. The IoMT provides a unifying infrastructure capable of addressing some of these limitations by enabling continuous monitoring, data management and analysis, data-driven personalization, and scalable delivery of rehabilitation. IoMT-enabled sensors, wearables, robotic systems, and telemedicine platforms allow objective, high-frequency capture of physiological, motor and cognitive data in real-world environments. When combined with cloud computing and ML these data streams support adaptive, closed-loop rehabilitation models that individualize medical care, optimize timing of interventions such as FES or NIBS, and enable early detection of plateaus or decline. Emerging evidence from randomized trials, cohort studies, and feasibility frameworks indicates that such approaches can achieve outcomes comparable to, and in some cases exceeding, conventional rehabilitation therapy, while expanding access for patients in resource-limited or remote settings.

The integration of IoMT with virtual reality, brain–computer interfaces, robotics, and AI-driven decision support illustrates a broader paradigm shift from episodic, clinic-centered rehabilitation toward continuous, home-embedded recovery ecosystems. These systems emphasize patient engagement, neuroplasticity-driven training, and longitudinal outcome tracking, aligning rehabilitation more closely with the principles of precision medicine. However, significant challenges remain, including data interoperability, cybersecurity, regulatory oversight, algorithm interpretability, and the need for large, diverse datasets to support generalizable machine-learning models.

9. Conclusions

Finally, IoMT-based neurorehabilitation represents a transformative opportunity to enhance stroke recovery by increasing therapy intensity, personalization, and accessibility while maintaining clinical oversight. Future progress will depend on rigorous multicenter trials with standardized outcomes, harmonized data standards, and interdisciplinary collaboration among clinicians, engineers, and policymakers. Addressing these challenges will be essential for translating promising IoMT-enabled technologies from research settings into equitable, routine clinical care that improves functional independence and quality of life for the growing population of stroke survivors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C., W.W., Z.J. and S.B..; methodology, A.C and Z.J..; writing—original draft preparation, A.C., E.S., J.T., B.K. and W.W.; writing—review and editing, A.C., Z.J. and S.B.; visualization, J.T. and B.K.; supervision, S.B.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial intelligence |

| BCIss |

Brain-computer interfaces |

| ECG |

Electrocardiogram |

| EEG |

Electroencephalogram |

| EHR |

Electronic health record |

| EMG |

Electromyography |

| FES |

Functional electrical stimulation |

| IMU |

Inertial measurement unit |

| IoMT |

Internet of medical things |

| ML |

Machine learning |

| NIBS |

Non-invasive brain stimulation |

| RS-tDCS |

Remotely supervised-transcranial direct current stimulation |

| tDCS |

Transcranial direct current stimulation |

| rTMS |

Transcranial magnetic stimulation |

| VR |

Virtual reality |

References

-

Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Neurol, 2024. 23(10): p. 973-1003.

- Feigin, V.L., et al., World Stroke Organization: Global Stroke Fact Sheet 2025. Int J Stroke, 2025. 20(2): p. 132-144. [CrossRef]

- Shahid, J., A. Kashif, and M.K. Shahid, A Comprehensive Review of Physical Therapy Interventions for Stroke Rehabilitation: Impairment-Based Approaches and Functional Goals. Brain Sci, 2023. 13(5). [CrossRef]

- Huang, C., et al., Internet of medical things: A systematic review. Neurocomput., 2023. 557(C): p. 18. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, J., et al., Internet of Medical Things (IoMT)-Based Smart Healthcare System: Trends and Progress. Comput Intell Neurosci, 2022. 2022: p. 7218113.

- Gallo, G.D. and D. Micucci, Internet of Medical Things Systems Review: Insights into Non-Functional Factors. Sensors (Basel), 2025. 25(9).

- Wei, S. and Z. Wu, The Application of Wearable Sensors and Machine Learning Algorithms in Rehabilitation Training: A Systematic Review. Sensors (Basel), 2023. 23(18).

- Marín-Medina, D.S., et al., New approaches to recovery after stroke. Neurol Sci, 2024. 45(1): p. 55-63. [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Ollinger, G., et al., Telerehabilitation using a 2-D planar arm rehabilitation robot for hemiparetic stroke: a feasibility study of clinic-to-home exergaming therapy. J Neuroeng Rehabil, 2024. 21(1): p. 207.

- Kim, S., et al., AI-driven cognitive telerehabilitation for stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Front Neurol, 2025. 16: p. 1636017.

- Sun, S., et al., A randomized controlled Trial of telerehabilitation intervention for acute ischemic stroke patients Post-Discharge. J Clin Neurosci, 2025. 136: p. 111245.

- Contrada, M., et al., Multidomain Cognitive Tele-Neurorehabilitation Training in Long-Term Post-Stroke Patients: An RCT Study. Brain Sci, 2025. 15(2). [CrossRef]

- Lam, W.W.T., Y.M. Tang, and K.N.K. Fong, A systematic review of the applications of markerless motion capture (MMC) technology for clinical measurement in rehabilitation. J Neuroeng Rehabil, 2023. 20(1): p. 57.

- Ahmed, T., et al., Automated Movement Assessment in Stroke Rehabilitation. Front Neurol, 2021. 12: p. 720650.

- Maceira-Elvira, P., et al., Wearable technology in stroke rehabilitation: towards improved diagnosis and treatment of upper-limb motor impairment. J Neuroeng Rehabil, 2019. 16(1): p. 142. [CrossRef]

- Adans-Dester, C., et al., Enabling precision rehabilitation interventions using wearable sensors and machine learning to track motor recovery. NPJ Digit Med, 2020. 3: p. 121. [CrossRef]

- Karoulla, E., et al., Tracking Upper Limb Motion via Wearable Solutions: Systematic Review of Research From 2011 to 2023. J Med Internet Res, 2024. 26: p. e51994.

- Rech, K., et al., Enhancing safety monitoring in post-stroke rehabilitation through wearable technologies. Clin Rehabil, 2025. 39(3): p. 388-398.

- Stock, R., A.P. Gaarden, and E. Langørgen, The potential of wearable technology to support stroke survivors' motivation for home exercise - Focus group discussions with stroke survivors and physiotherapists. Physiother Theory Pract, 2024. 40(8): p. 1795-1806.

- Gassert, R. and V. Dietz, Rehabilitation robots for the treatment of sensorimotor deficits: a neurophysiological perspective. J Neuroeng Rehabil, 2018. 15(1): p. 46.

- Oña, E.D., et al., A Review of Robotics in Neurorehabilitation: Towards an Automated Process for Upper Limb. J Healthc Eng, 2018. 2018: p. 9758939. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., et al., A Home-based Dual-mode Upper Limb Rehabilitation System: Teleoperation Mode and Bilateral Mode with sEMG and IMU. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform, 2025. 29(11): p. 8140-8152. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., et al., Personalized robots for long-term telerehabilitation after stroke: a perspective on technological readiness and clinical translation. Front Rehabil Sci, 2023. 4: p. 1329927.

- Wu, X., et al., Rehabilitation training robot using mirror therapy for the upper and lower limb after stroke: a prospective cohort study. J Neuroeng Rehabil, 2025. 22(1): p. 54. [CrossRef]

- Rithiely, B., et al., Non-invasive brain stimulation for stroke-related motor impairment and disability: an umbrella review of systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurosci, 2025. 19: p. 1633986.

- Hofmeijer, J., F. Ham, and G. Kwakkel, Evidence of rTMS for Motor or Cognitive Stroke Recovery: Hype or Hope? Stroke, 2023. 54(10): p. 2500-2511. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.Y., et al., Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Motor Recovery After Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials With Low Risk of Bias. Neuromodulation, 2025. 28(1): p. 16-42.

- Van Hoornweder, S., et al., The effects of transcranial direct current stimulation on upper-limb function post-stroke: A meta-analysis of multiple-session studies. Clin Neurophysiol, 2021. 132(8): p. 1897-1918.

- Edwards, J.D., et al., A translational roadmap for transcranial magnetic and direct current stimulation in stroke rehabilitation: Consensus-based core recommendations from the third stroke recovery and rehabilitation roundtable. Neurorehabil Neural Repair, 2024. 38(1): p. 19-29.

- Ko, M.H., et al., Home-Based Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation to Enhance Cognition in Stroke: Randomized Controlled Trial. Stroke, 2022. 53(10): p. 2992-3001. [CrossRef]

- Charvet, L.E., et al., Remotely-supervised transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) for clinical trials: guidelines for technology and protocols. Front Syst Neurosci, 2015. 9: p. 26.

- Kocahasan, M., et al., Remotely Supervised Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation in Post-Stroke Recovery: A Scoping Review. Medicina (Kaunas), 2025. 61(4). [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A., et al., A systematic review on functional electrical stimulation based rehabilitation systems for upper limb post-stroke recovery. Front Neurol, 2023. 14: p. 1272992.

- Jaqueline da Cunha, M., et al., Functional electrical stimulation of the peroneal nerve improves post-stroke gait speed when combined with physiotherapy. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Phys Rehabil Med, 2021. 64(1): p. 101388.

- Biasiucci, A., et al., Brain-actuated functional electrical stimulation elicits lasting arm motor recovery after stroke. Nat Commun, 2018. 9(1): p. 2421. [CrossRef]

- Ren, C., et al., The effect of brain-computer interface controlled functional electrical stimulation training on rehabilitation of upper limb after stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Hum Neurosci, 2024. 18: p. 1438095.

- Eraifej, J., et al., Effectiveness of upper limb functional electrical stimulation after stroke for the improvement of activities of daily living and motor function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev, 2017. 6(1): p. 40.

- Gunduz, M.E., B. Bucak, and Z. Keser, Advances in Stroke Neurorehabilitation. J Clin Med, 2023. 12(21). [CrossRef]

- Duncan, P.W. and J. Bernhardt, Telerehabilitation: Has Its Time Come? Stroke, 2021. 52(8): p. 2694-2696.

- Kayola, G., et al., Stroke Rehabilitation in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Challenges and Opportunities. Am J Phys Med Rehabil, 2023. 102(2S Suppl 1): p. S24-s32.

- Salgueiro, C., G. Urrútia, and R. Cabanas-Valdés, Influence of Core-Stability Exercises Guided by a Telerehabilitation App on Trunk Performance, Balance and Gait Performance in Chronic Stroke Survivors: A Preliminary Randomized Controlled Trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2022. 19(9). [CrossRef]

- Tosto-Mancuso, J., et al., Gamified Neurorehabilitation Strategies for Post-stroke Motor Recovery: Challenges and Advantages. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep, 2022. 22(3): p. 183-195.

- Saygili, F., et al., Effects of modified-constraint induced movement therapy based telerehabilitation on upper extremity motor functions in stroke patients. Brain Behav, 2024. 14(6): p. e3569. [CrossRef]

- Cramer, S.C., et al., Telerehabilitation Following Stroke. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am, 2024. 35(2): p. 305-318.

- Everard, G., et al., New technologies promoting active upper limb rehabilitation after stroke: an overview and network meta-analysis. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med, 2022. 58(4): p. 530-548. [CrossRef]

- Villarroel, R., et al., Virtual Reality Therapy for Upper Limb Motor Impairments in Patients With Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Physiother Res Int, 2025. 30(2): p. e70040.

- Hao, J., et al., Comparison of immersive and non-immersive virtual reality for upper extremity functional recovery in patients with stroke: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Neurol Sci, 2023. 44(8): p. 2679-2697.

- Lin, C., Y. Ren, and A. Lu, The effectiveness of virtual reality games in improving cognition, mobility, and emotion in elderly post-stroke patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg Rev, 2023. 46(1): p. 167.

- Park, Y.S., C.S. An, and C.G. Lim, Effects of a Rehabilitation Program Using a Wearable Device on the Upper Limb Function, Performance of Activities of Daily Living, and Rehabilitation Participation in Patients with Acute Stroke. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021. 18(11).

- Li, D., et al., Effects of brain-computer interface based training on post-stroke upper-limb rehabilitation: a meta-analysis. J Neuroeng Rehabil, 2025. 22(1): p. 44. [CrossRef]

- Zrenner, C., et al., Closed-Loop Neuroscience and Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation: A Tale of Two Loops. Front Cell Neurosci, 2016. 10: p. 92.

- Ma, Y.N., et al., Integrative neurorehabilitation using brain-computer interface: From motor function to mental health after stroke. Biosci Trends, 2025. 19(3): p. 243-251.

- Wang, A., et al., Rehabilitation with brain-computer interface and upper limb motor function in ischemic stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Med, 2024. 5(6): p. 559-569.e4.

- Liu, X., et al., Effects of motor imagery based brain-computer interface on upper limb function and attention in stroke patients with hemiplegia: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Neurol, 2023. 23(1): p. 136. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K., et al., Deep learning model for classifying shoulder pain rehabilitation exercises using IMU sensor. J Neuroeng Rehabil, 2024. 21(1): p. 42.

- Senadheera, I., et al., AI Applications in Adult Stroke Recovery and Rehabilitation: A Scoping Review Using AI. Sensors (Basel), 2024. 24(20).

- Lu, Z., et al., Implementation of Remote Activity Sensing to Support a Rehabilitation Aftercare Program: Observational Mixed Methods Study With Patients and Health Care Professionals. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, 2023. 11: p. e50729.

- Ginsburg, G.S., R.W. Picard, and S.H. Friend, Key Issues as Wearable Digital Health Technologies Enter Clinical Care. N Engl J Med, 2024. 390(12): p. 1118-1127. [CrossRef]

- Lanotte, F., M.K. O'Brien, and A. Jayaraman, AI in Rehabilitation Medicine: Opportunities and Challenges. Ann Rehabil Med, 2023. 47(6): p. 444-458.

- Hossain, D., et al., The use of machine learning and deep learning techniques to assess proprioceptive impairments of the upper limb after stroke. J Neuroeng Rehabil, 2023. 20(1): p. 15.

- Jeter, R., et al., Classifying Residual Stroke Severity Using Robotics-Assisted Stroke Rehabilitation: Machine Learning Approach. JMIR Biomed Eng, 2024. 9: p. e56980.

- van der Gun, G.J., et al., Can machine learning improve on the early prediction of upper limb recovery after stroke? J Neuroeng Rehabil, 2025. 22(1): p. 223.

- Rasoolinejad, M., et al., Machine learning predicts improvement of functional outcomes in spinal cord injury patients after inpatient rehabilitation. Front Rehabil Sci, 2025. 6: p. 1594753. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J. and Y. Xie, Machine learning techniques for independent gait recovery prediction in acute anterior circulation ischemic stroke. J Neuroeng Rehabil, 2025. 22(1): p. 19.

- Laver, K.E., et al., Telerehabilitation services for stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2020. 1(1): p. CD010255.

-

Telerehabilitation In The Home After Stroke: A Randomized, Controlled, Assessor-Blind Clinical Trial, I. Moss Rehabilitation Research, D. National Institute of Neurological, and Stroke, Editors. 2024.

- Saywell, N.L., et al., Telerehabilitation After Stroke Using Readily Available Technology: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair, 2021. 35(1): p. 88-97. [CrossRef]

- Dedo, R., T. Jurga, and J. Barkham, VA Home Telehealth Program for Initiating and Optimizing Heart Failure Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy. Fed Pract, 2023. 40(Suppl 6): p. S16-s23.

- Abbott, A., Mind-controlled robot arms show promise. Nature, 2012.

-

Understanding and Restoring Speech Production Using an Intracortical Brain-computer Interface, D. National Institute on and D. Other Communication, Editors. 2023.

- Chaudhary, U., Neurofeedback Basics and Applications, in Expanding Senses using Neurotechnology : Volume 1 ‒ Foundation of Brain-Computer Interface Technology, U. Chaudhary, Editor. 2025, Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham. p. 363-400.

- Perez-Marcos, D., et al., Increasing upper limb training intensity in chronic stroke using embodied virtual reality: a pilot study. J Neuroeng Rehabil, 2017. 14(1): p. 119. [CrossRef]

-

The Use of Immersive Virtual Reality for Upper Limb Neurorehabilitation in Stroke Survivors, L. Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de and R. Clinique Romande de, Editors. 2017.

- Maier, M., B.R. Ballester, and P. Verschure, Principles of Neurorehabilitation After Stroke Based on Motor Learning and Brain Plasticity Mechanisms. Front Syst Neurosci, 2019. 13: p. 74.

-

Integrating AI in Stroke Neurorehabilitation (AISN), E. Universidad Miguel Hernandez de, Editor. 2025.

- Abbas, G.H., et al., AI-Driven Rehabilitation Robotics: Advancements in and Impacts on Patient Recovery. Cureus, 2025. 17(10): p. e94273.

- Yao, Y., et al., Advancements in Sensor Technologies and Control Strategies for Lower-Limb Rehabilitation Exoskeletons: A Comprehensive Review. Micromachines (Basel), 2024. 15(4).

- Olawade, D.B., et al., Enhancing home rehabilitation through AI-driven virtual assistants: a narrative review. Ann Transl Med, 2025. 13(5): p. 61. [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, S.A., et al., A Resource-Efficient, High-Dose, Gamified Neurorehabilitation Program for Chronic Stroke at Home: Retrospective Real-World Analysis. JMIR Serious Games, 2025. 13: p. e69335.

- Norris, T.A., et al., Shaping corticospinal pathways in virtual reality: effects of task complexity and sensory feedback during mirror therapy in neurologically intact individuals. J Neuroeng Rehabil, 2024. 21(1): p. 154.

- Jin, W., et al., Electroencephalogram-based adaptive closed-loop brain-computer interface in neurorehabilitation: a review. Front Comput Neurosci, 2024. 18: p. 1431815. [CrossRef]

- Faria, A.L., et al., NeuroAIreh@b: an artificial intelligence-based methodology for personalized and adaptive neurorehabilitation. Front Neurol, 2023. 14: p. 1258323.

- Abedi, A., et al., Artificial intelligence-driven virtual rehabilitation for people living in the community: A scoping review. NPJ Digit Med, 2024. 7(1): p. 25.

- Zhong, X., AI-assisted assessment and treatment of aphasia: a review. Front Public Health, 2024. 12: p. 1401240. [CrossRef]

- Liscano, Y., L.M. Bernal, and J.A. Díaz Vallejo, Effectiveness of AI-Assisted Digital Therapies for Post-Stroke Aphasia Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci, 2025. 15(9). [CrossRef]

- Ansari, R.A., et al., Artificial Intelligence-Guided Neuromodulation in Heart Failure with Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction: Mechanisms, Evidence, and Future Directions. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis, 2025. 12(8). [CrossRef]

- Prunskis, J.V., et al., The Application of Artificial Intelligence to Enhance Spinal Cord Stimulation Efficacy for Chronic Pain Management: Current Evidence and Future Directions. Curr Pain Headache Rep, 2025. 29(1): p. 85. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).