1. Introduction

Public procurement stands as one of the strongest tools available to the public sector for improving performance, driving national development, and supporting broader socioeconomic transformation, since it directly shapes how public resources are converted into services and infrastructure that affect everyday life [

1].). Across the world, governments commit an estimated 12 to 20 percent of gross domestic product to procurement activities, and in many developing countries the share is even higher, which places procurement at the very centre of public value creation and economic management [

2,

3].

At the same time, procurement remains widely known as one of the public functions most exposed to corruption and abuse, partly because of the large sums involved and the discretion exercised by officials at different stages of the process [

4]. In Sub Saharan Africa, procurement related irregularities account for a significant proportion of audit infractions, financial wastage, and value losses recorded in public expenditure, and this situation continues to weaken accountability systems and service delivery [

5].. In the case of Ghana, annual reports of the Auditor General repeatedly draw attention to persistent breaches of procurement law, poor contract management practices, unsupported and irregular payments, limited competition in tendering, and collusive behaviour among suppliers, all of which combine to erode fiscal discipline and gradually reduce public confidence in the management of state resources [

6,

7]..

Because procurement decisions directly influence the quality, cost, efficiency, and fairness of public services, efforts to strengthen ethical behaviour in procurement have become a major concern in global governance, especially as citizens demand better value for money and greater transparency in public spending. International bodies such as the World Bank, the OECD, the African Union, and Ghana’s Public Procurement Authority consistently stress professionalization, skills development, and ethics training as key responses to corruption risks and weak procurement outcomes, even though the way these elements work together is not always clearly explained [

2,

3].

In spite of this strong policy focus, the actual capabilities that support ethical behaviour in procurement are still not well developed in theory and research, and the literature often treats them in a rather narrow way [

1].Many studies reduce procurement literacy to basic knowledge of laws and regulations, working on the assumption that once officers understand the legal framework, they will naturally act ethically, which is not always the case in practice [

8,

9]. This view simplifies the real nature of procurement work, since procurement officers are required to exercise analytical judgement, use digital systems, manage supplier relationships, handle interpersonal pressures, and apply ethical reasoning in day-to-day decisions, areas that are not fully captured by legal knowledge alone [

2,

10].

Ethical behaviour in procurement is shaped by a combination of competencies rather than by legal knowledge on its own, because practitioners are expected to analyse demand, assess risk, evaluate suppliers, monitor contracts, operate digital systems, justify decisions, and manage pressure and conflicts of interest, often at the same time [

11,

12].Each of these activities relies on different forms of literacy that are both cognitively and behaviourally distinct, which means that understanding ethical procurement practice requires a shift away from one-dimensional ideas of procurement literacy toward a broader view that captures the full capability structure supporting ethical action in real settings [

10].

This study introduces the Procurement Literacy Capability Theory PLCT, a multidimensional framework that defines procurement literacy as an interlinked system of cognitive, analytical, managerial, digital and ethical competencies that function together rather than in isolation. The framework brings together five literacy domains, namely Legal and Policy Knowledge Literacy, Procurement Planning and Decision-Making Literacy, Supplier and Contract Management Literacy, Digital and E Procurement Literacy, and Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy, reflecting both the formal rules governing public procurement systems and the behavioural skills needed for responsible, transparent, and accountable conduct [

11,

12,

13] Grounded in capability theory as advanced by [

14], alongside competency-based perspectives and behavioural ethics, PLCT suggests that ethical behaviour does not arise from single pockets of knowledge but from the interaction and reinforcement of multiple literacy capabilities across the procurement cycle, although in practice these capabilities are not always evenly developed [

1,

8].

Despite the growing complexity of procurement roles, empirical research on procurement ethics has not advanced at the same pace, and several important gaps continue to limit understanding in this area [

3]. Three critical gaps remain in the literature unexplored.

First, much of the existing literature continues to treat procurement literacy as a single and largely legal based construct, with attention placed mainly on awareness of rules and policies, while forms of literacy linked to digital systems, analytical judgement, managerial practice, and ethical reasoning receive far less consideration [

1]. This narrow framing restricts how well we understand the behavioural processes that actually drive ethical outcomes in procurement practice [

8].Second, only a small number of studies have explored how different literacy domains work together to influence ethical behaviour through connected capability pathways, and the common belief that competence in one area will naturally translate into ethical conduct overlooks the practical and behavioural skills required to act ethically under real institutional pressure [

3,

14]

Third, even though procurement reforms frequently stress professionalisation and skills development, there is still a lack of empirical work that validates a multidimensional literacy model or examines its ability to predict ethical behaviour, despite growing agreement that many ethics failures stem from capability gaps rather than simple lack of knowledge. This paper addresses these gaps by developing and empirically testing the Procurement Literacy Capability Theory through structural equation modelling applied to validated literacy constructs, though some relationships are more nuanced than initially assumed.

The results show that procurement literacy is clearly multidimensional and that ethical behaviour emerges from the interaction of planning literacy, supplier management capability, digital literacy, legal and policy knowledge, and ethical practice competence, rather than from any single domain acting alone. Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy appears as the main behavioural channel through which other literacy domains shape ethical intention, while corruption perception, although relevant for behaviour, does not break these underlying capability pathways. By proposing PLCT and supporting it with empirical evidence, this study contributes a core theoretical step forward in procurement governance research, reframing procurement professionalism as an integrated capability system and offering a practical behavioural model for strengthening integrity, accountability, and ethical performance in public procurement contexts.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Public Procurement and Ethical Behaviour

Public procurement is broadly viewed as a key instrument through which governments pursue efficiency, transparency, and long-term development outcomes, since it governs how public resources are converted into goods, works, and services that affect society at large [

1]. At the global level, procurement represents about 12 to 20 percent of gross domestic product, placing it among the largest components of public expenditure and making it highly influential in shaping development results [

3]. Because procurement choices directly affect the quality of infrastructure, health care delivery, education inputs, and other public investments, ethical behaviour within procurement systems has immediate consequences for service delivery and public welfare [

2].

At the same time, procurement is repeatedly identified as one of the most corruption exposed functions of government. Evidence from Sub Saharan Africa indicates that procurement related activities account for the largest share of corruption losses in the public sector, often linked to practices such as bid rigging, inflated contract prices, conflicts of interest, and weak oversight during contract execution [

5,

15].. In Ghana, successive reports of the Auditor General consistently record procurement irregularities, including noncompetitive tendering, poor contract management, unsupported payments, and failure to comply with established procurement procedures, and these weaknesses together account for billions of Ghana cedis in financial losses [

6,

7]. While some of these outcomes reflect deliberate misconduct, they also reveal persistent capability gaps among procurement actors that limit their ability to act appropriately within complex systems [

8].

Ethical behaviour in procurement therefore depends on the ability of practitioners to apply principles such as fairness, transparency, accountability, and value for money across all stages of the procurement cycle [

16]. Empirical research nonetheless shows that unethical practices frequently arise when officials lack the skills required to design sound tenders, evaluate suppliers effectively, monitor contract performance, or operate digital procurement platforms [

17,

18]. This suggests that improving ethical conduct cannot rely on legal compliance alone but must involve the development of a range of interconnected competencies that support ethical judgement in practice. Within this context, scholars and policy makers increasingly argue that professionalisation and capability development should be treated as central strategies to reduce corruption risks and improve procurement outcomes, although implementation often remains uneven.

2.2. Procurement Literacy: Current Conceptual Limitations

Although procurement competence has received considerable attention in both academic and policy discussions, procurement literacy itself continues to be defined in a rather narrow manner within research and practice. The majority of studies equate procurement literacy with knowledge of procurement laws, regulations, and formal procedures, treating legal familiarity as the main indicator of competence and ethical conduct [

19,

20].This framing rests on the assumption that once practitioners understand the rules, ethical procurement behaviour will naturally follow, and as a result many training programmes and empirical studies tend to reinforce a rule focused approach, while paying limited attention to the analytical, managerial, and digital skills that modern procurement systems increasingly demand [

8,

13].

In reality, public procurement today involves responsibilities that go well beyond simple legal compliance, since practitioners are expected to carry out needs assessments, analyse markets, evaluate supplier performance, manage risk, negotiate contracts, and operate electronic procurement platforms, often under time and political pressure [

13]. Evidence from the literature shows that weaknesses in any one of these areas can seriously undermine procurement integrity. Poor planning, for instance, often results in rushed emergency procurement; weak contract monitoring creates space for supplier opportunism; limited digital capability reduces transparency and makes auditing more difficult; and insufficient ethical practice competence leaves officers vulnerable to conflicts of interest and undue influence [

21,

22].

Despite these practical realities, procurement scholarships have rarely brought together multiple literacy domains into a unified capability framework. Many studies still treat procurement literacy as a single construct or concentrate almost entirely on legal and policy knowledge, while overlooking digital literacy, supplier and contract management competence, planning capability, and applied ethical judgement. This one-dimensional approach offers only limited explanatory value, because it does not reflect the interconnected nature of procurement work or clarify how different competencies interact to shape ethical behaviour in practice. As a result, there is increasing recognition among scholars and practitioners that more integrated and comprehensive approaches are needed to strengthen procurement capacity and improve ethical outcomes across public procurement systems [

9]

2.3. Ethical Behavioural Intention in Public Administration

Ethical behaviour in public administration is closely linked to behavioural intention, since intention captures the willingness of an individual to act in a morally appropriate way when confronted with an ethical choice. Foundational theories such as the Theory of Reasoned Action and the Theory of Planned Behaviour place intention at the centre of behaviour, arguing that it serves as the most immediate predictor of what people actually do in practice [

23,

24]. Within ethical decision making, intention reflects a person’s readiness to choose ethical options over unethical ones, even when alternatives may appear easier or more rewarding.

This emphasis on intention is also evident in Rest’s Four Component Model, which explains ethical action as the outcome of moral awareness, moral judgement, moral motivation, and moral character, with motivation aligning closely with behavioural intention [

25]. Without the intention to act ethically, awareness and judgement alone are unlikely to translate into ethical behaviour. Public sector ethics scholars therefore view behavioural intention as a meaningful indicator of future ethical conduct, particularly in contexts where direct observation of behaviour is difficult or premature [

26].

Behavioural intention is especially relevant in the case of procurement students, who represent future entrants into a highly regulated and risk prone professional field. Because these individuals have not yet been fully exposed to organisational cultures, workplace incentives, or political pressures, their ethical behavioural intention tends to reflect their underlying literacy, values, and capabilities rather than learned coping strategies or institutional norms. For this reason, intention provides a theoretically sound and practical outcome variable for emerging professionals in procurement, capturing the extent to which literacy-based capabilities translate into ethical readiness before real world constraints begin to shape behaviour.

2.4. Capability Theory and Competency Based Models

Sen’s Capability Approach offers an important way to understand how competence is converted into actual functioning in professional life, since it focusses on what individuals are genuinely able to do rather than what they simply know [

14]. From a capability perspective, behaviour is not shaped by knowledge in isolation but by a combination of skills, resources, conditions, and opportunities that together determine whether a person can act effectively. In professional settings, this implies that effective and ethical behaviour develops through the interaction of multiple capabilities, and not from isolated pieces of information or technical knowledge.

Within public administration research, capability theory has been used to explain professional competence by highlighting the need for blended abilities that span analytical, technical, ethical, and practical domains [

27,

28]. Competency based models echo this position by arguing that performance in the public service depends on integrated sets of knowledge, skills, and behaviours that are aligned with specific roles and responsibilities [

7]. In the context of procurement, this means that practitioners must combine competence in planning, supplier and contract management, use of digital systems, interpretation of legal and policy requirements, and ethical reasoning, rather than relying on any single skill area [

6,

9].

Understanding ethical performance in procurement therefore requires attention to the progression from knowledge, to capability, and finally to behaviour. Having knowledge of rules and ethical principles is not enough if individuals lack the analytical judgement or practical skills needed to apply those principles in complex decision-making situations. Ethical behaviour emerges when different dimensions of literacy, including digital capability, planning competence, managerial skill, legal understanding, and ethical practice, interact and reinforce one another, although in practice these elements are not always developed evenly across individuals or institutions.

2.5. The Need for a Multidimensional Capability Model

The body of literature reviewed points to several intersecting insights which together highlight a significant conceptual gap within public procurement research. To begin with, ethical vulnerabilities remain a persistent challenge that continues to weaken procurement performance across regions, including Sub Saharan Africa. Evidence from audit reports, corruption perception indices, and empirical investigations repeatedly indicates that procurement is among the highest risk areas for fraud, mismanagement, and loss of public value. Even with ongoing reforms, ethical failures still appear at critical stages such as planning, supplier selection, contract implementation, and record keeping, suggesting that many existing interventions have not fully engaged with the behavioural drivers of ethical breakdown.

A second insight concerns the way procurement literacy has been defined and applied in the literature. The dominant approach treats procurement literacy largely as knowledge of laws and regulations, reinforcing a compliance centred view of procurement practice. While legal and policy knowledge is clearly necessary, concentrating almost exclusively on this dimension tends to hide the importance of analytical judgement, managerial capability, digital competence, and ethical skills that are essential in contemporary procurement environments. Today’s procurement systems depend heavily on digital platforms, data analysis, market intelligence, risk evaluation, contract monitoring, and supplier relationship management, but these competencies sit outside the traditional legal knowledge focus. This narrow conceptualisation constrains theoretical advancement and reduces the ability of existing models to explain why ethical failures persist despite formal compliance structures being in place.

Third, research on ethical behaviour within public administration consistently shows that ethical behavioural intention is shaped by several interacting influences, including moral competence, situational awareness, and skills that are specific to the professional domain. Behavioural ethics perspectives, including the Theory of Planned Behaviour, Rest’s ethical decision-making model, and Treviño’s person situation interactionist framework, all point to the fact that the willingness to act ethically is not driven by knowledge alone, but by a broader mix of cognitive, motivational, and contextual elements. For this reason, ethical behavioural intention serves as a sound and theoretically grounded outcome variable for examining ethical readiness among emerging procurement professionals, particularly before workplace pressures begin to reshape behaviour.

Fourth, insights from capability theory and competency-based models in public administration further underline the importance of examining how integrated sets of skills translate into actual functioning. Sen’s Capability Approach stresses that effective action depends on the interaction of multiple internal capabilities rather than isolated pieces of knowledge. Similarly, competency frameworks argue that performance in the public sector results from combinations of technical, analytical, and behavioural competencies that together enable professionals to function effectively. When applied to procurement, these perspectives imply that ethical behaviour is more likely to emerge from the interaction of different literacy domains, including digital, analytical, managerial, legal, and ethical competencies, rather than from any single knowledge area.

These arguments reveal a clear theoretical and empirical gap. Although the complexity of procurement and the multidimensional nature of ethical behaviour are widely acknowledged, existing studies have not conceptualised procurement literacy as a multidimensional capability system, nor have they empirically examined how different literacy dimensions interact to shape ethical behavioural intention. Much of the literature still treats procurement literacy as a one-dimensional construct or isolates individual competencies without exploring their combined behavioural effects.

This gap points to the need for a multidimensional capability model that frames procurement literacy as an interconnected set of digital, analytical, managerial, legal, and ethical practice competencies that jointly influence ethical behavioural intention. Such an approach would be better aligned with contemporary procurement practice, consistent with behavioural ethics theory, and responsive to ongoing calls for professionalisation in public procurement systems. The Procurement Literacy Capability Theory introduced in the following section responds directly to this need by presenting an integrated and empirically validated framework for explaining how procurement competencies come together to shape ethical behaviour.

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Procurement Literacy as a Multidimensional Capability

Procurement literacy has for a long time been described mainly as knowledge of procurement laws, procedures, and regulatory requirements, and while this understanding remains important, it does not fully reflect the realities of contemporary procurement practice. A compliance focused view places emphasis on rule following, yet it tends to overlook the wider range of competencies that procurement actors are now expected to demonstrate in practice. Modern public procurement increasingly requires strong analytical planning, confidence in using digital systems, effective engagement with suppliers, sound ethical judgement, and the capacity to operate within complex and often uncertain contracting environments [

21,

22].

In this context, procurement literacy is better understood as a multidimensional capability rather than as a single body of knowledge. Building on Sen’s Capability Approach, which defines capabilities as internal resources that allow people to achieve valued forms of functioning, this study conceptualises procurement literacy as a set of interconnected capabilities that work together to support effective and ethical procurement practice (Sen, 1993). Specifically, procurement literacy is framed as consisting of five interdependent capability domains, which collectively shape how procurement professionals interpret rules, make decisions and act ethically throughout the procurement cycle [

9].

3.2. Dimensions of Procurement Literacy as Multidimensional Capabilities

The Digital and Electronic Procurement Literacy (DIGEPL) domain captures the ability of procurement actors to use digital procurement systems and electronic platforms to enhance transparency, maintain data integrity, and support informed decision making. Core competence elements within this domain include effective use of electronic procurement tools, proper digital record keeping, interpretation of procurement data, and application of transparency controls, although in practice these skills are not always evenly developed.

Procurement Planning and Decision-Making Literacy (PLANDML) reflects the analytical capacity required to assess organisational needs, develop clear specifications, evaluate procurement risks, and design appropriate procurement strategies that align with budgetary and policy constraints. This domain covers competencies such as needs assessment, budgeting, risk analysis, forecasting, and strategic decision making, which together shape the quality of procurement outcomes.

Supplier and Contract Management Literacy (SUPCML) refers to the managerial capability needed to evaluate suppliers, negotiate contract terms, enforce contractual obligations, and monitor supplier performance over time. The key competency elements here include supplier evaluation, contract negotiation, contract enforcement, ongoing performance monitoring, and risk mitigation, all of which play a critical role in maintaining value for money and accountability.

Legal and Policy Knowledge Literacy (LEGPKL) focusses on understanding procurement laws, regulatory frameworks, compliance requirements, and internal institutional procedures that govern procurement activity. Competence in this domain involves accurate interpretation of regulations, conducting compliance checks, meeting documentation requirements, and awareness of sanctions for noncompliance, although knowledge alone does not always guarantee ethical conduct.

Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy (ETHPPL) represents the behavioural capability to apply principles of fairness, justify procurement decisions, resist unethical influence, and uphold integrity throughout procurement tasks. Its core competencies include decision justification, transparent work practices, resistance to undue pressure, and accountability behaviours, which together support ethical action even in challenging or ambiguous situations.

3.3. Interactions Among Literacy Capabilities

The Procurement Literacy Capability Theory assumes that procurement literacy domains do not function as separate or stand-alone competencies, but rather as interdependent capabilities that support and reinforce one another across the entire procurement cycle. Public procurement follows an integrated and largely sequential process, starting with the identification and assessment of needs, progressing through supplier engagement and contract execution, and concluding with monitoring and evaluation activities. Because of this structure, the development of capability in one area often sets the foundation for competence in the next stage of the process.

Within the PLCT framework, literacy dimensions are therefore viewed as forming a capability cascade, in which earlier capabilities strengthen and enable more advanced behavioural capabilities. For example, sound planning and decision-making support effective supplier management, while digital literacy enhances transparency and accountability at multiple stages of procurement. Ethical behaviour, in this sense, is not treated as an isolated trait but as an outcome that emerges when these interlinked capabilities work together, although the strength of each link may vary depending on context and individual experience.

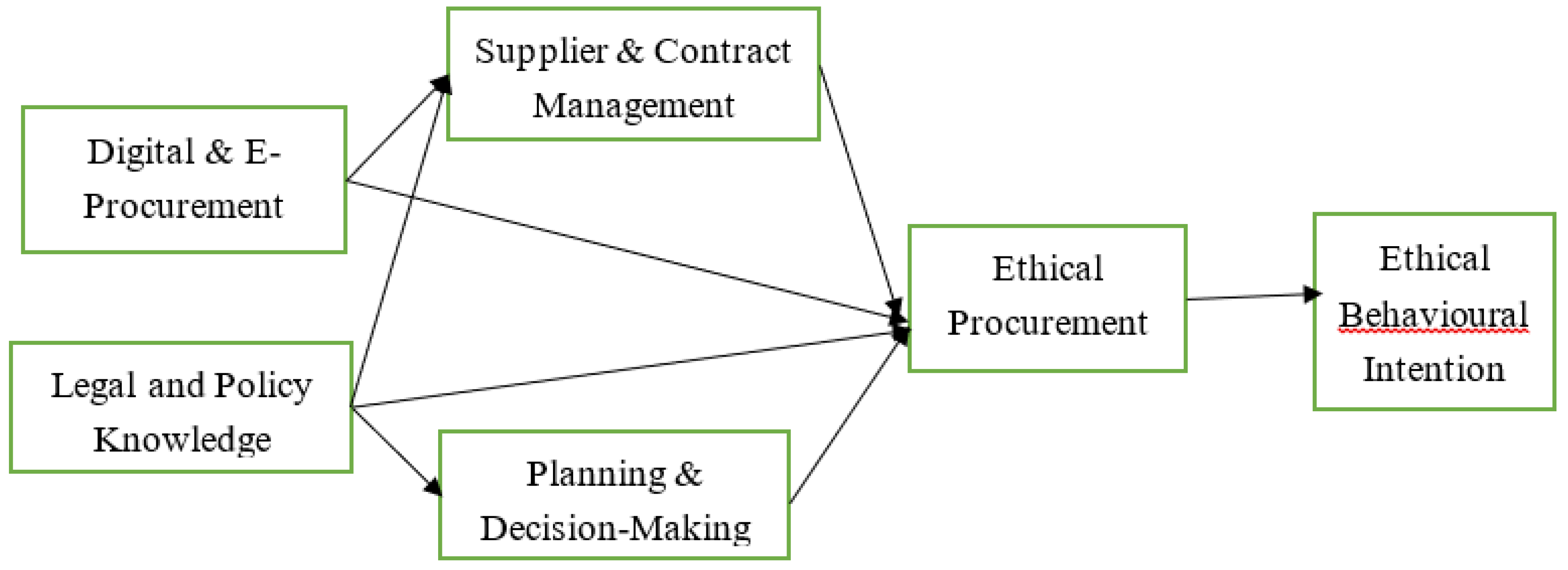

The relationships in general form a coherent capability structure, as illustrated in

Figure 1, where digital capability supports analytical capability, analytical capability enables managerial capability, and managerial capability contributes to the development of ethical capability, while legal and policy knowledge reinforces ethical competence throughout the process. These layered interdependencies represent the central mechanism through which procurement literacy evolves into ethical behavioural intention within the PLCT framework, even though the strength of each link may vary between individuals and institutional settings.

3.4. Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy as the Central Mechanism

Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy represents the behavioural core of the Procurement Literacy Capability Theory, because it is the point at which knowledge and skills are translated into actual ethical action. While the other literacy domains, including digital capability, planning competence, supplier management capability, and legal and policy knowledge, provide important cognitive and technical resources, they are not sufficient on their own to produce ethical behaviour in practice. Research in behavioural ethics repeatedly shows that ethical conduct depends on the ability to turn judgement and awareness into action through clear decision justification, proper documentation, transparent processes, and resistance to undue influence, and this is precisely what ETHPPL seeks to capture [

25,

26].

Within the PLCT framework, ETHPPL operates as the central transmission mechanism that connects the upstream literacy capabilities to ethical behavioural intention. Digital literacy enhances the quality and visibility of information that supports ethical choices, planning competence creates structured points in the procurement process where ethical judgement must be exercised, supplier management capability exposes practitioners to ethical risks that arise during interaction with markets, and legal and policy knowledge clarifies what is expected in terms of compliance. However, these capabilities only influence ethical outcomes to the extent that they strengthen Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy. When individuals lack the behavioural capacity to apply ethical principles in real situations, technical skills and regulatory knowledge remain largely unused or misapplied.

Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy therefore functions as the immediate behavioural capability through which procurement professionals demonstrate fairness, accountability, and integrity in their daily work. It is the mechanism that converts literacy inputs into ethical readiness, even before actual behaviour is observed. Placing ETHPPL at the centre of the framework aligns with behavioural ethics models, which argue that ethical behaviour arises when moral judgement, competence, and situational demands come together. In procurement settings, ETHPPL enables this alignment, making it the key pathway through which ethical behavioural intention is formed.

3.5. Ethical Behavioural Intention as Capability Outcome

Ethical behavioural intention represents the final capability outcome within the Procurement Literacy Capability Theory, since it reflects the point at which accumulated competencies translate into readiness for ethical action. The Theory of Planned Behaviour identifies intention as the most immediate and reliable predictor of actual behaviour, and behavioural ethics models similarly argue that ethical conduct begins with a conscious intention to act in line with moral standards [

23,

25]. In the case of procurement students, who have not yet entered organisational environments where routines, incentives, and constraints can shape behaviour, ethical intention offers a sound and theoretically justified indicator of ethical preparedness.

Within the PLCT framework, ethical behavioural intention does not arise from knowledge in isolation but from the interaction of several upstream capabilities that develop across the procurement literacy system. Digital capability, analytical planning skills, supplier and contract management competence, and legal and policy understanding provide essential input, but their influence on intention is channelled mainly through Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy. ETHPPL embodies the practical behavioural competence needed to apply fairness, justify procurement decisions, resist pressure, and uphold integrity in day to day procurement tasks, even when situations are complex or ambiguous.

Ethical behavioural intention is therefore framed not simply as an attitudinal response but as the functional expression of an integrated capability system. When individuals possess a balanced mix of technical, analytical, managerial, and ethical competencies and are able to coordinate these through Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy, they are more likely to form intentions that align with ethical procurement conduct. In this way, intention becomes the natural endpoint of a capability cascade, capturing an individual’s readiness to act ethically in real procurement contexts.

3.6. Integrated Summary of the Procurement Literacy Capability Theory and Conceptual Model

The Procurement Literacy Capability Theory explains ethical behavioural intention in public procurement as the result of coordinated interaction among several literacy capabilities, rather than as an outcome of legal knowledge alone. In this framework, procurement literacy is defined as a multidimensional capability system made up of digital proficiency, analytical planning competence, supplier and contract management capability, legal and policy understanding, and practical ethical skills. These capabilities are not treated as independent elements, but as interconnected components that evolve in a sequence reflecting the stages of the procurement cycle.

The conceptual model presented in

Figure 1 arranges these capabilities into a capability cascade. Digital and electronic procurement literacy serves as the enabling capability, as it enhances access to information and supports the analytical work required for effective planning and decision making. The planning capability then shapes supplier and contract management competence by setting clear specifications, evaluation criteria, and performance expectations. Supplier management capability subsequently contributes to ethical procurement practice literacy, strengthening the behavioural skills needed to apply fairness, justify decisions, maintain transparency, and withstand undue influence. Legal and policy knowledge supports this ethical capability by clarifying compliance limits and institutional expectations, though it does not operate in isolation.

At the core of the model lies Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy, which functions as the main behavioural channel through which upstream competencies are converted into ethical readiness. The theory holds that technical, analytical, and regulatory capabilities affect ethical behavioural intention largely by reinforcing ETHPPL, a position that aligns with behavioural ethics perspectives emphasising the movement from moral understanding to moral action [

25,

26].. Ethical behavioural intention then emerges as the final capability outcome, consistent with the Theory of Planned Behaviour, which identifies intention as the closest predictor of actual behaviour [

23]. For procurement students who have not yet been exposed to organisational constraints or institutional pressures, ethical intention offers a valid and theoretically grounded measure of ethical preparedness.

In general, the integrated conceptual model provides a holistic and empirically testable explanation of how procurement literacy influences ethical outcomes. It responds directly to gaps in the existing literature by showing that ethical intention is shaped not by isolated knowledge domains, but by the combined effect of multiple capabilities interacting through a central ethical practice mechanism. In doing so, the Procurement Literacy Capability Theory establishes a strong theoretical basis for understanding competence development, ethical formation, and capability strengthening within public procurement systems.

4. Hypotheses Development

The Procurement Literacy Capability Theory builds on the idea that ethical behavioural intention develops from an interconnected capability structure, rather than from isolated areas of knowledge or rule familiarity. From behavioural ethics theory, the Capability Approach and competency based perspectives in public administration, the theory assumes that behaviour is shaped through the interaction of cognitive, analytical, managerial, and ethical capabilities, supported by evidence from procurement research that highlights the complexity of modern procurement practice [

14,

16,

21,

22,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]

4.1. Digital Capability → Analytical Capability

Digital capability improves access to accurate and timely information, improves transparency, and supports more precise analysis within procurement processes. When procurement actors are able to use electronic systems effectively, they gain better visibility over needs, markets, prices, and risks, which improves the quality of planning and decision making. Empirical studies indicate that digital tools contribute to stronger strategic planning and more rational procurement decisions, particularly by reducing information gaps and discretion-based errors. In line with the PLCT framework, digital and electronic procurement literacy is therefore expected to reinforce the analytical competence required for procurement planning and structured decision making [

21,

22].

H1: Digital and E Procurement Literacy (DIGEPL) positively influences Procurement Planning and Decision-Making Literacy (PLANDML).

4.2. Analytical Capability →Managerial Capability

The analytical capability expressed through effective planning plays a central role in shaping the way suppliers are selected, engaged, and managed. Prior studies show that strong needs assessment, realistic budgeting, and systematic risk analysis are closely associated with better supplier relationships and improved contract performance outcomes [

16,

29].. When planning is weak or rushed, supplier engagement becomes inconsistent and contract execution is often exposed to inefficiencies and disputes. Within the PLCT framework, planning and decision-making literacy is therefore treated as an upstream capability that enables sound supplier and contract management.

H2: Procurement Planning and Decision-Making Literacy (PLANDML) positively influences Supplier and Contract Management Literacy (SUPCML).

4.3. Managerial Capability → Ethical Capability

Interactions with suppliers represent one of the points in the procurement process where ethical risks are most pronounced, including collusion, favouritism, and exposure to undue influence. Managerial capability equips procurement actors with the confidence and structure needed to handle these interactions in a fair and consistent manner. Behavioural ethics theory suggests that ethical conduct develops when individuals are able to apply judgement and control in situations involving discretion and pressure [

25]. In this sense, the competence in supplier and contract management is expected to directly contribute to the development of practical ethical capabilities.

H3: Supplier and Contract Management Literacy (SUPCML) positively influences Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy (ETHPPL).

4.4. Legal and Policy Knowledge → Ethical Capability

Legal and policy knowledge provides the interpretive base for identifying procedural breaches and understanding what constitutes acceptable and unacceptable conduct within procurement systems [

20]. However, awareness of rules does not automatically lead to ethical behaviour, especially in complex or ambiguous situations. Behavioural ethics research indicates that legal knowledge affects behaviour mainly when converted into applied ethical competence, such as proper documentation, justification of decisions, and resistance to pressure [

26]. Consistent with PLCT, legal and policy literacy is therefore expected to strengthen ethical procurement practice rather than directly shaping behaviour.

H4: Legal and Policy Knowledge Literacy (LEGPKL) positively influence Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy (ETHPPL).

4.5. Ethical Capability → Ethical Behavioural Intention

Behavioural ethics research and the Theory of Planned Behaviour both point to practical ethical competence as a direct driver of ethical intention, since individuals are more likely to intend to act ethically when they feel capable of doing so in real situations [

23,

25,

26]. In procurement settings, the ability to justify decisions, withstand pressure, apply rules consistently and act fairly is the immediate basis for ethical readiness. When procurement actors possess this practical ethical capability, ethical intention is more likely to follow naturally, even before actual behaviour is observed.

H5: Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy (ETHPPL) positively influences Ethical Behavioural Intention (EBEH).

4.6. Mediation Hypotheses

Within the Procurement Literacy Capability Theory, Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy is positioned as the central mechanism through which upstream capabilities are translated into ethical intention. Behavioural ethics theory explains that moral awareness and regulatory understanding only shape behaviour when individuals are able to apply ethical principles within specific contexts, rather than simply knowing what is right or wrong [

25,

26]. Capability theory makes a similar argument, suggesting that effective functioning depends on converting internal resources and skills into concrete action [

14].

Based on this logic, Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy is expected to operate as a mediating capability, channelling the effects of managerial and legal knowledge into ethical behavioural intention. Supplier and contract management competence exposes practitioners to ethically sensitive situations, while legal and policy knowledge clarifies acceptable boundaries, but neither is sufficient unless supported by practical ethical skill.

Consequently, two mediation relationships are proposed.

H6: Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy (ETHPPL) mediates the relationship between Supplier and Contract Management Literacy (SUPCML) and Ethical Behavioural Intention (EBEH).

H7: Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy (ETHPPL) mediates the relationship between Legal and Policy Knowledge Literacy (LEGPKL) and Ethical Behavioural Intention (EBEH).

5. Methodology

5.1. Research Design

This study adopted a quantitative cross sectional research design and applied structural equation modelling to empirically examine the Procurement Literacy Capability Theory. The use of SEM was considered appropriate because the theory specifies a multidimensional capability structure with interrelated pathways and mediating relationships, which are difficult to test adequately using conventional regression techniques that assume simple and independent effects [

30] (Hair et al., 2021). The analytical approach therefore allowed the study to capture both direct and indirect relationships among the capability domains within a single integrated framework.

Data was collected using the validated Multidimensional Procurement Literacy Instrument developed by [

13], which captures multiple latent constructs relevant to procurement practice. Specifically, the instrument measures digital literacy, planning capability, supplier and contract management capability, legal and policy literacy, ethical procurement practice literacy, and ethical behavioural intention. All constructs were operationalised using five-point Likert scale items, allowing respondents to indicate the extent to which each statement reflected their perceptions and preparedness, although responses may still reflect some level of subjective judgement as is common with survey-based studies.

5.2. Sample and Participants

The target population for this study comprised undergraduate students enrolled in procurement and supply chain programmes at accredited universities in Ghana. This group was chosen for two main reasons. First, the Procurement Literacy Capability Theory is concerned with how procurement capability is formed before individuals enter full professional practice, a stage where organisational cultures and institutional pressures can soften or reshape personal ethical dispositions over time [

25,

26]. Second, students who have completed the core procurement courses possess the minimum knowledge base needed to engage meaningfully with the literacy and ethics related items included in the instrument.

A total of 776 respondents were drawn from Levels 200 to 400, ensuring that all participants had completed core procurement modules and possessed adequate exposure to procurement concepts. Level 100 students were excluded because of their limited engagement with foundational procurement coursework. The final sample size was considered adequate for confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modelling, meeting and exceeding conservative recommendations for psychometric evaluation of latent variable models in large and representative enough for infinite population exceeding 50,000 [

30,

31,

32,

33].

5.3. Data Collection Procedures

Data were collected using an anonymised Google Forms questionnaire that was administered during scheduled class sessions with the approval of course coordinators. The survey was distributed digitally and supervised by trained research assistants, a step taken to maintain confidentiality and reduce the risk of social desirability bias during responses [

34]. Participants were clearly informed that participation was voluntary and that their responses had no connection to course assessment or academic grading, which helped create a relaxed response environment.

5.4. Ethical Clearance

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Committee on Human Research, Publications and Ethics of the School of Medical Sciences, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, in collaboration with the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital in Kumasi, Ghana (Ref: CHRPE/AP/1000/25). All study procedures complied with internationally accepted research ethics standards for studies involving human participants. Students were provided with an information sheet explaining the purpose of the study, confidentiality arrangements, and data protection measures. Participation was voluntary and informed consent was implied through the completion and submission of the questionnaire. No identifying information was collected, and all completed responses were stored securely in password protected files accessible only to members of the research team.

5.5. Measures

All study constructs were measured using reflective items drawn from the validated Multidimensional Procurement Literacy Instrument [

13]. Each procurement literacy domain was assessed using six items designed to capture capability within that specific area. Ethical behavioural intention was also measured with six items, developed in line with the Theory of Planned Behaviour [

23]. Responses were recorded on a five point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. In the present dataset, Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.86 to 0.94 across all constructs, indicating a high level of internal consistency, although minor response variation was still observed.

5.6. Data Preparation and Screening

Data preparation followed established best practice guidelines for structural equation modelling. The proportion of missing data was low, below five percent, and missing values were handled using expectation maximisation procedures [

35]. Preliminary checks showed that skewness and kurtosis values were within acceptable limits for maximum likelihood estimation. Multivariate outliers were examined using Mahalanobis distance, and variance inflation factor values below three confirmed that multicollinearity was not a concern in the dataset. Detailed descriptive statistics and screening outcomes are reported in

Section 6.

5.7. Data Analysis Strategy

Structural equation modelling was conducted using JAMOVI and JASP, following the two-step analytical approach proposed by [

36].. In the first step, confirmatory factor analysis was used to evaluate the measurement model and assess construct validity using multiple fit indices, including chi square over degrees of freedom, CFI, TLI, RMSEA, SRMR, and IFI [

37,

38] . Convergent and discriminant validity were examined using average variance extracted, composite reliability, the Fornell Larcker criterion, and HTMT ratios [

39]. In the second step, the structural model was estimated to test the hypothesised capability pathways, including the sequential relationships from digital capability to planning, supplier capability, and ethical procurement practice, as well as the mediating role of ethical procurement practice literacy. Indirect effects were assessed using bootstrapping with 5,000 resamples to ensure robust inference.

6. Results

6.1. Data Screening and Preparation

Data screening was carried out in line with recommended procedures for structural equation modelling, to ensure that the dataset was suitable for both measurement and structural analysis [

40,

41]. Missing values across the indicators were generally low, ranging from 0.0 to 3.4 percent, and these were handled using expectation maximisati, which is considered appropriate when missingness is limited and randomly distributed [

30,

35].

All measurement items satisfied acceptable conditions for univariate normality. Skewness values ranged between minus 0.629 and 0.228, while kurtosis values fell between minus 1.045 and minus 0.117, remaining comfortably within the limits recommended for maximum likelihood estimation. Multicollinearity did not present a concern, as variance inflation factor values ranged from 1.75 to 3.51, well below the commonly cited threshold of five, and no bivariate correlation exceeded 0.78.

Following these screening procedures, the final dataset consisting of 776 observations met all key assumptions required for confirmatory factor analysis and subsequent structural equation modelling. The data were therefore considered adequate for testing the proposed capability structure and hypothesised relationships, even though minor deviations typical of survey data were still present.

6.2. Socio Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

A total of 776 procurement students took part in the study, drawn from two traditional universities and two technical universities across Ghana. The respondents were selected from Levels 200 to 400 and students enrolled in both regular and distance education programmes. A detailed breakdown of the demographic characteristics is presented in

Table 1.

The sample was made up largely of regular students, who accounted for 86.9 percent of respondents, while distance learners represented 13.1 percent. Economic background was grouped into two categories for modelling purposes, although three categories were used for descriptive analysis. Using the full classification, the majority of respondents described their background as moderate income, representing 60.1 percent, followed by low income at 36.3 percent, with only a small fraction identifying as high income at 3.6 percent.

Gender distribution within the sample was fairly balanced, with males constituting 52.8 percent and females 47.2 percent of respondents, which supports reasonable representation across gender groups, even though a small proportion did not indicate gender. The level of study showed a noticeable concentration at Level 300, which accounted for 55.2 percent of the sample, followed by Level 200 at 26.0 percent and Level 400 at 18.8 percent. This pattern broadly reflects typical enrolment structures within procurement related programmes in Ghanaian universities.

Work experience among respondents varied widely. Nearly half of the students, about 47.7 percent, reported having some form of internship experience, while 38.9 percent indicated that they had no prior work experience at all. A smaller group, 9.3 percent, had engaged in part time work, and only 4.1 percent reported holding full-time positions. This mix suggests that the sample includes both relatively inexperienced students and those with some exposure to professional environments, which is important when interpreting results related to ethical behavioural intention.

This demographic profile points to a reasonably diverse and representative sample of procurement students within Ghanaian tertiary institutions. This diversity strengthens the credibility of the analysis and supports cautious generalisation of the study findings to similar student populations, even though minor imbalances across categories remain.

The measurement model covering the five procurement literacy constructs, namely digital literacy, planning and decision-making literacy, supplier and contract management literacy, legal and policy knowledge literacy, and ethical procurement practice literacy, together with the outcome construct of ethical behavioural intention, was evaluated using confirmatory factor analysis. CFA was employed to examine how well the observed items represented their underlying latent constructs and to assess the adequacy of the proposed measurement structure.

Results showed that the overall fit of the measurement model was very strong, with acceptable to excellent fit indices reported across the classical, robust, and scaled estimation approaches, as summarised in

Table 2. These findings indicate that the specified constructs were measured reliably and that the factor structure aligned well with the theoretical expectations of the study, even though small variations across estimators were observed, as is typical in applied SEM analyses.

The confirmatory factor analysis produced a very strong measurement model, and the evidence from several fit indices points in the same direction. The incremental fit indices were particularly high, with CFI = .995, TLI = .994, IFI = .995, and NFI = .993, all clearly above the recommended cutoff of .90 [

37]. The parsimony fit was also satisfactory, PNFI = .921, suggesting that the model achieves a good balance between explanatory strength and simplicity, without adding unnecessary parameters.

The absolute fit measures further supported the adequacy of the model. The Standardised Root Mean Square Residual values fell within acceptable bounds, ranging from .050 to .055, indicating small residual discrepancies between the observed and estimated matrices. RMSEA values ranged from .073 to .077 under the classical and scaled estimators, which is consistent with acceptable approximation error for complex and multidimensional measurement structures [

42]. In addition, both the Goodness of Fit Index and the Adjusted GFI exceeded .99, reinforcing confidence in the overall specification [

40].

The results indicate that the measurement structure underlying the Procurement Literacy Capability Model is statistically sound and conceptually consistent, making it appropriate to proceed to the estimation of the structural relationships.

Table 3 reports the standardised factor loadings for all observed items measuring the five capability constructs as well as the outcome variable. All factor loadings exceeded the recommended minimum value of .60 [

40], and most items loaded above .70, which points to strong indicator reliability across the measurement model.

Digital and E-Procurement Literacy, Supplier and Contract Management Literacy, Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy, and Ethical Behavioural Intention all showed high and stable loadings, suggesting that their indicators represented the underlying latent constructs quite well. Legal and Policy Knowledge Literacy and Planning and Decision-Making Literacy also demonstrated adequate convergence, with factor loadings ranging from .67 to .91. Overall, the pattern of loadings supports the assumption of one dimensionality for each construct and confirms that the measurement model is stable and properly specified. These findings provide solid empirical grounds for moving forward with reliability checks, validity assessment, and structural model testing, even though small variations across items are expected in applied survey research.

6.3. Reliability and Validity Assessment

The quality of the measurement model was evaluated by examining internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity, in line with established standards for structural equation modelling [

40,

43]. All constructs showed strong internal consistency. Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.865 to 0.948, while McDonald’s omega coefficients ranged between 0.850 and 0.958, all exceeding the commonly accepted threshold of 0.70 for acceptable reliability [

44]. These results suggest that the items within each scale are measuring the same underlying concept in a consistent manner, even though slight variations across constructs were observed.

Convergent validity was assessed using both standardised factor loadings and the Average Variance Extracted values. All factor loadings met or exceeded recommended cut off points, with most items loading above 0.80, indicating that the observed indicators strongly reflect their respective latent constructs. The AVE values ranged from 0.532 to 0.824, which is above the minimum criterion of 0.50 proposed by [

45]. This indicates that each construct explains a meaningful proportion of variance in its indicators, rather than being dominated by measurement error.

Discriminant validity was examined using the Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio. All HTMT values were below the conservative threshold of 0.85, although the highest value reached 0.890, which is still considered acceptable for constructs that are theoretically related [

46]. These findings confirm that the six capability domains, namely digital and electronic procurement literacy, legal and policy knowledge literacy, planning literacy, supplier and contract management literacy, ethical procurement practice literacy, and ethical behavioural intention, remain empirically distinct even though they are conceptually connected within the proposed framework.

The evidence from reliability coefficients, AVE statistics, and HTMT ratios provides strong support for the psychometric adequacy of the measurement model. The constructs demonstrate satisfactory internal consistency, capture their intended conceptual meanings, and retain sufficient distinction from one another. Overall, these results indicate that the multidimensional procurement literacy model is robust and suitable for subsequent structural model estimation, even if minor overlaps across closely related domains cannot be completely ruled out.

Table 4.

Reliability Indices (α, ω, AVE).

Table 4.

Reliability Indices (α, ω, AVE).

| Variable |

α |

Ordinal α |

ω₁ |

ω₂ |

ω₃ |

AVE |

| LEGPKL |

0.865 |

0.889 |

0.850 |

0.850 |

0.806 |

0.532 |

| DIGEPL |

0.909 |

0.929 |

0.923 |

0.923 |

0.958 |

0.720 |

| EBEH |

0.948 |

0.965 |

0.950 |

0.950 |

0.952 |

0.824 |

| ETHPPL |

0.928 |

0.949 |

0.931 |

0.931 |

0.939 |

0.762 |

| SUPCML |

0.926 |

0.941 |

0.930 |

0.930 |

0.942 |

0.740 |

| PLANDML |

0.926 |

0.942 |

0.930 |

0.930 |

0.939 |

0.739 |

Table 5.

HTMT Discriminant Validity Matrix.

Table 5.

HTMT Discriminant Validity Matrix.

| |

LEGPKL |

DIGEPL |

EBEH |

ETHPPL |

SUPCML |

PLANDML |

| LEGPKL |

1.000 |

0.586 |

0.641 |

0.660 |

0.733 |

0.765 |

| DIGEPL |

0.586 |

1.000 |

0.512 |

0.597 |

0.688 |

0.650 |

| EBEH |

0.641 |

0.512 |

1.000 |

0.886 |

0.630 |

0.656 |

| ETHPPL |

0.660 |

0.597 |

0.886 |

1.000 |

0.703 |

0.696 |

| SUPCML |

0.733 |

0.688 |

0.630 |

0.703 |

1.000 |

0.890 |

| PLANDML |

0.765 |

0.650 |

0.656 |

0.696 |

0.890 |

1.000 |

6.4. Structural Path Analysis

The structural model was estimated using maximum likelihood estimation, and the standardised path coefficients are reported in

Table 7. Overall, the model showed strong explanatory strength across the key endogenous constructs. Ethical Behavioural Intention accounted for a large proportion of explained variance, R² = .787, while Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy recorded an R² value of .584. Supplier and Contract Management Literacy showed particularly high explanatory power with R² = .831, and Procurement Planning and Decision-Making Literacy recorded an R² of .730. These values suggest that the structural model captures a substantial share of variation in the core behavioural and capability outcomes, indicating solid predictive performance.

The estimated paths largely supported the proposed hypotheses. Digital and electronic procurement literacy had a strong and positive effect on planning and decision-making capability, β = .854, p < .001, showing that digital competence plays a central role in strengthening analytical capacity. Planning capability, in turn, strongly predicted supplier and contract management literacy, β = .906, p < .001, confirming that sound analytical preparation translates into more effective managerial capability in supplier engagement and contract execution. Supplier and contract management literacy also showed a significant positive effect on ethical procurement practice literacy, β = .352, p < .001, suggesting that practical exposure to supplier relationships enhances applied ethical competence.

Ethical procurement practice literacy emerged as the most influential predictor of ethical behavioural intention, β = .838, p < .001. This result indicates that ethical intention is shaped mainly by the ability to apply ethical principles in practice, rather than by technical skills or regulatory awareness alone. Legal and policy knowledge literacy showed a weak direct association with ethical behavioural intention, β = .067, p = .020, which was statistically significant but small in magnitude, and this suggests that legal knowledge by itself has limited behavioural impact unless it is translated into practical ethical capability. Its influence was more clearly observed through indirect effects operating via ethical procurement practice literacy.

In combination, these findings provide strong support for the central claim of the Procurement Literacy Capability Theory, namely that ethical outcomes in procurement are capability driven and arise from the interaction of digital, analytical, managerial, legal, and ethical competencies, rather than from reliance on any single body of knowledge. The pattern of results reinforces the view that ethics in procurement is built through layered capability development, even though the strength of each pathway may vary slightly across contexts.

Figure 2 presents the final structural equation model, showing all significant standardised path coefficients and factor loadings supporting the hypothesised relationships.

6.5. Mediation Analysis

Mediation effects were examined using bootstrapped indirect effect testing with 5,000 resamples, and the results confirm that Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy operates as the central behavioural mechanism through which procurement capabilities influence ethical behavioural intention. The full pattern of indirect effects is reported in

Table 8, and the results show a clear layered structure rather than isolated effects.

The strongest indirect pathway followed a multistage capability sequence moving from digital competence through planning and managerial capability and then ethical practice before reaching ethical intention. Specifically, the pathway from Digital and Electronic Procurement Literacy to Procurement Planning and Decision-Making Literacy, then to Supplier and Contract Management Literacy, followed by Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy and finally Ethical Behavioural Intention, produced a significant indirect effect, β = .091, p < .001. This finding offers strong empirical backing for the capability cascade proposed by the Procurement Literacy Capability Theory, where early-stage capabilities enable later behavioural capacities rather than acting independently.

Legal and Policy Knowledge Literacy also demonstrated a substantial indirect effect on ethical behavioural intention when transmitted through Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy, β = .332, p < .001. This result indicates that legal knowledge becomes behaviourally meaningful only when students possess the practical ethical competence required to interpret rules, justify decisions, and apply regulations appropriately in real or simulated procurement situations. Legal awareness on its own appears insufficient to drive ethical intention.

Interestingly, a negative indirect effect was observed along the pathway from Legal and Policy Knowledge Literacy through Supplier and Contract Management Literacy and Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy to Ethical Behavioural Intention, β = −.070, p = .021. This suggests that when supplier management capability is weak, legal knowledge may actually lose behavioural relevance and possibly create ethical blind spots, a pattern consistent with arguments that rule familiarity without managerial competence can distort ethical judgement rather than strengthen it.

The mediation results reinforce the view that ethical practice capability functions as the behavioural engine of the procurement literacy system. Ethical readiness is shaped by how multiple capabilities interact and reinforce one another, not by the presence of any single skill or knowledge area in isolation. The mediation hypothesis H7 was fully supported, as all relevant indirect effects reached statistical significance at p < .05, and no meaningful direct effect was found between Legal and Policy Knowledge Literacy and Ethical Behavioural Intention, confirming full mediation through Supplier and Contract Management Literacy and Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy.

The structural and mediation findings together offer a clear capability-based account of how ethical behaviour takes shape in procurement, and the pattern that emerges is one of interaction rather than isolated influence. The results show quite clearly that ethical intention does not grow out of single pockets of knowledge but instead develops through the way different literacy domains work together and reinforce one another over time.

To begin with, legal literacy on its own does not lead straight to ethical behaviour. Its effect only becomes visible when it passes through Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy, which suggests that ethical conduct is driven more by capability than by rules alone. Students and future practitioners may know the law, but unless that knowledge is converted into practical ethical competence, it remains largely inactive and sometimes even confusing in real decision situations.

Second, the strongest influences in the model appeared along multistage capability chains. Sequential paths, especially those connecting planning literacy, supplier and contract management literacy, and ethical practice literacy, produced much stronger effects than any single direct link. This pattern supports the idea that procurement competence grows in connected stages, rather than through isolated or stand-alone training components, even though many programmes still treat them separately.

Third, Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy clearly functions as the behavioural centre of the entire framework. It emerged as the strongest direct predictor of ethical intention and also served as the key mediator across all meaningful indirect relationships. This underlines its role as the point where other competencies become behaviourally useful, without which technical or legal skills struggle to influence intention in a meaningful way.

Fourth, managerial and supplier focused competencies appear to be critical leverage points for shaping ethical outcomes. Supplier and Contract Management Literacy not only had a significant effect on ethical practice capability but also featured prominently in several mediated pathways that eventually led to ethical intention. This suggests that ethical risks and learning are often activated during supplier interactions, where judgement and discretion are most look like tested.

Taken as a whole, these results provide strong empirical backing for the Procurement Literacy Capability Theory. The observed relationships are consistent with its central claims that procurement literacy is interdependent, sequenced, and closely tied to behaviour. The findings show that competencies must first reinforce one another and then be translated into practical ethical capability before they can meaningfully shape ethical intention, which explains why narrow or rule focused approaches often fall short in practice.

5. Discussion

This study set out to explore how different dimensions of procurement literacy interact to shape ethical behaviour among university students in Ghana, while also proposing and empirically validating the Procurement Literacy Capability Theory. The results provide strong backing for the core ideas of the theory and offer a clear empirical explanation of how ethical behaviour develops within contemporary procurement settings, even though the process is not always linear in practice.

The findings show that procurement literacy should not be viewed as a bundle of separate knowledge areas. Rather, the literacy domains operate as an interconnected capability system in which competencies reinforce one another, follow a sequence, and eventually translate into ethical intention. Legal and Policy Knowledge did not demonstrate a meaningful direct effect on ethical behaviour. Its effect became evident only when it passed through Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy, which supports the PLCT position that knowing the rules is not enough unless individuals are able to apply those rules in context. This result is consistent with earlier work on ethical behaviour, which argues that knowledge must be filtered through interpretive judgement and situational competence before it can influence action (Rest et al., 2014; Treviño et al., 2014).

A similar pattern was observed for digital and electronic procurement literacy. Digital capability did not directly predict ethical behaviour but instead contributed indirectly through planning literacy and supplier management capability. This suggests that digital systems enhance ethical capacity only when they are embedded within human decision processes, rather than operating as stand-alone technical solutions. Governance frameworks in the public sector have made similar observations, noting that technology amplifies existing capability rather than replacing judgement [

47,

48,

49]. In line with PLCT, the results therefore support the idea that procurement capabilities work in a chain, where earlier capabilities enable later behavioural influence.

Planning and decision-making literacy emerged as a structurally important capability within the model. It exerted a strong influence on Supplier and Contract Management Literacy, which then shaped ethical practice capability. This finding reinforces earlier studies showing that weak planning is a major source of procurement irregularities and inefficiencies [

50,

51,

52]. Within the logic of PLCT, planning creates the conditions under which supplier management competence can operate effectively, and it is within these conditions that ethical practice becomes possible rather than abstract.

Supplier and Contract Management Literacy played a dual role in the model, functioning both as a mediator and as a capability amplifier. It directly influenced ethical practice literacy and also carried several indirect pathways to ethical behaviour. This supports the PLCT view of supplier management as a conversion capability, one that turns upstream knowledge and planning into practical, actionable competence. Research on contract governance has similarly identified supplier management as the operational point where integrity, compliance, and discretion are most actively tested [

53,

54,

55].

Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy was the strongest predictor of ethical behaviour and the central mediating mechanism across all meaningful pathways [

13]. 2025). This confirms that ethical practice competence is the behavioural heart of procurement literacy. In PLCT terms, ethical behaviour is not treated as a simple cognitive outcome, but as a capability outcome that only emerges when multiple competencies converge within the ethical practice domain. The empirical evidence clearly supports this view, since every significant pathway leading to ethical behaviour passed through Ethical Procurement Practice Literacy.

The results provide robust support for the Procurement Literacy Capability Theory, and all three of its core assumptions are validated. First, capability interdependence is evident, as none of the literacy domains independently predicted ethical behaviour. Second, capability sequencing is clearly observed, with the strongest pathways following the order of planning, supplier management, ethical practice, and then ethical behaviour. Third, behavioural translation is confirmed, since ethical behaviour only emerged when knowledge and skills were converted into ethical practice competence.

By integrating these findings, the study demonstrates that ethical procurement behaviour is not driven by isolated literacies or simple familiarity with rules. Instead, it arises from a coherent capability chain that enables individuals to interpret regulations, manage risk, and act ethically within complex procurement environments. From a practical standpoint, the findings suggest that procurement education should move away from purely knowledge based modular teaching and toward capability-based sequencing. Ethical practice training should be positioned as the integrative core of procurement literacy, supported by planning competence, supplier management skills, and legal understanding. Universities and training institutions may need to rely more on experiential methods such as dilemma simulations, supervised procurement clinics, and scenario-based assessments, so that students can practice translating knowledge into ethical action.

From a theoretical perspective, this study contributes a validated model explaining how procurement literacy shapes ethical behaviour. It represents the first empirical test of the Procurement Literacy Capability Theory and demonstrates its explanatory strength using confirmatory factor analysis, structural equation modelling, and bootstrapped mediation analysis. Future research can extend PLCT to practising procurement officers and public sector professionals, while also examining contextual moderators such as organisational culture, complexity of procurement environments, or political pressure.

In summary, the findings confirm that procurement literacy functions as a capability system. Ethical behaviour emerges from interdependent, sequenced, and translated competencies rather than from knowledge alone. By validating PLCT, this study provides a strong foundation for rethinking procurement ethics education and offers a useful theoretical lens for future work on procurement capability development.

7. Conclusion

This study set out to propose and empirically test the Procurement Literacy Capability Theory, with the aim of deepening understanding of how ethical behaviour takes shape within public procurement. Using data drawn from undergraduate procurement students in Ghana and applying structural equation modelling, the analysis shows quite clearly that procurement literacy functions as a multidimensional and interlinked capability system, rather than a loose collection of separate knowledge areas.

The results indicate that ethical behavioural intention is not produced directly by legal and policy knowledge. Instead, ethical outcomes develop when several procurement capabilities work together and are translated into ethical procurement practice literacy, which stands at the centre of the model. Digital capability, planning and decision-making competence, and supplier and contract management capability all contribute to this process, but only insofar as they feed into practical ethical competence. This cascade of capabilities confirms that ethical conduct in procurement is driven by capability development that is sequenced and grounded in practice, rather than by rule awareness alone.

By empirically confirming both the interdependence and the sequencing of procurement literacy domains, the study offers strong support for the central propositions of PLCT. The findings show that ethical procurement practice literacy is the key mechanism through which upstream capabilities influence ethical intention, while managerial and supplier focused competencies emerge as important leverage points for shaping ethical outcomes. In this way, the study extends existing work in behavioural ethics and public procurement by providing a validated, theory-based explanation of how ethical readiness is formed before individuals enter full professional practice.

From a theoretical standpoint, the study contributes a validated capability-based model of procurement ethics that moves beyond compliance focused and single dimension approaches. Methodologically, it illustrates the usefulness of combining confirmatory factor analysis, structural modelling, and bootstrapped mediation techniques to examine complex capability relationships. From a practical angle, the findings suggest that procurement education should move away from purely modular knowledge delivery toward sequenced capability development, with ethical practice positioned as an integrative competence supported by planning and supplier management skills.

Although the study focuses on ethical behavioural intention rather than observed behaviour, intention remains a theoretically sound and empirically strong outcome for research on capability formation. Future research could apply PLCT to practising procurement officers, track capability development over time, or examine contextual influences such as organisational culture, institutional pressure, or political interference.