1. Introduction

Cervical cancer remains a major global health challenge arising from the malignant progression of human papillomavirus (HPV) induced cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). Persistent high-risk HPV infection is the causal factor in virtually all cases of cervical dysplasia and cancer. Globally, cervical cancer ranks as the third most prevalent malignancy among women, with approximately 255,016 cases occurring in individuals aged 20 to 49 years. It is also the second leading cause of death from malignant diseases, accounting for 93,736 deaths [

1]. Without treatment, 20-30% of HSIL/CIN2+ cases may develop into invasive cervical cancer within ten years [

2,

3]. Standard therapies for CIN include excisional or ablative procedures [

4] such as loop electrosurgical excision, cold-knife conization, cryotherapy and laser ablation, which have high success rates but can damage cervical structure [

5,

6,

7]. Surgical treatments can lead to bleeding, infection, cervical stenosis, and major obstetric complications such as cervical insufficiency and preterm birth [

3,

8,

9]. With the rising incidence of CIN in younger women and a global emphasis on fertility preservation, there is a clear need for non-invasive alternatives [

10].

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has emerged over the past decade as a promising non-surgical option HPV-related cervical lesions. PDT involves the administration of a photosensitizer that selectively accumulates in dysplastic or HPV-infected epithelium, followed by illumination with a specific wavelength of light to produce reactive oxygen species that destroy abnormal cells while sparing healthy tissue [

10,

11]. Common photosensitizers, such as 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) and chlorin-based drugs, accumulate in neoplastic cells. When activated by red light (630–662 nm), they produce singlet oxygen and free radicals that trigger apoptosis and necrosis in dysplastic epithelium [

12]. In addition to direct cytotoxicity, PDT may have immunomodulatory effects. Studies report increases in local T-cell activity and reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines after PDT, suggesting enhanced clearance of HPV infection via immune mechanisms [

13]. Unlike excisional methods, PDT treats lesions in situ without excising tissue, thus preserving the anatomic and functional integrity of the cervix [

14]. This organ-sparing approach is particularly attractive for managing CIN in women who wish to avoid the reproductive risks of surgery.

This study aims to fill certain knowledge gaps by assessing the clinical effectiveness of PDT in a large group of women with HPV-related cervical lesions and examining how different patient factors affect treatment results.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

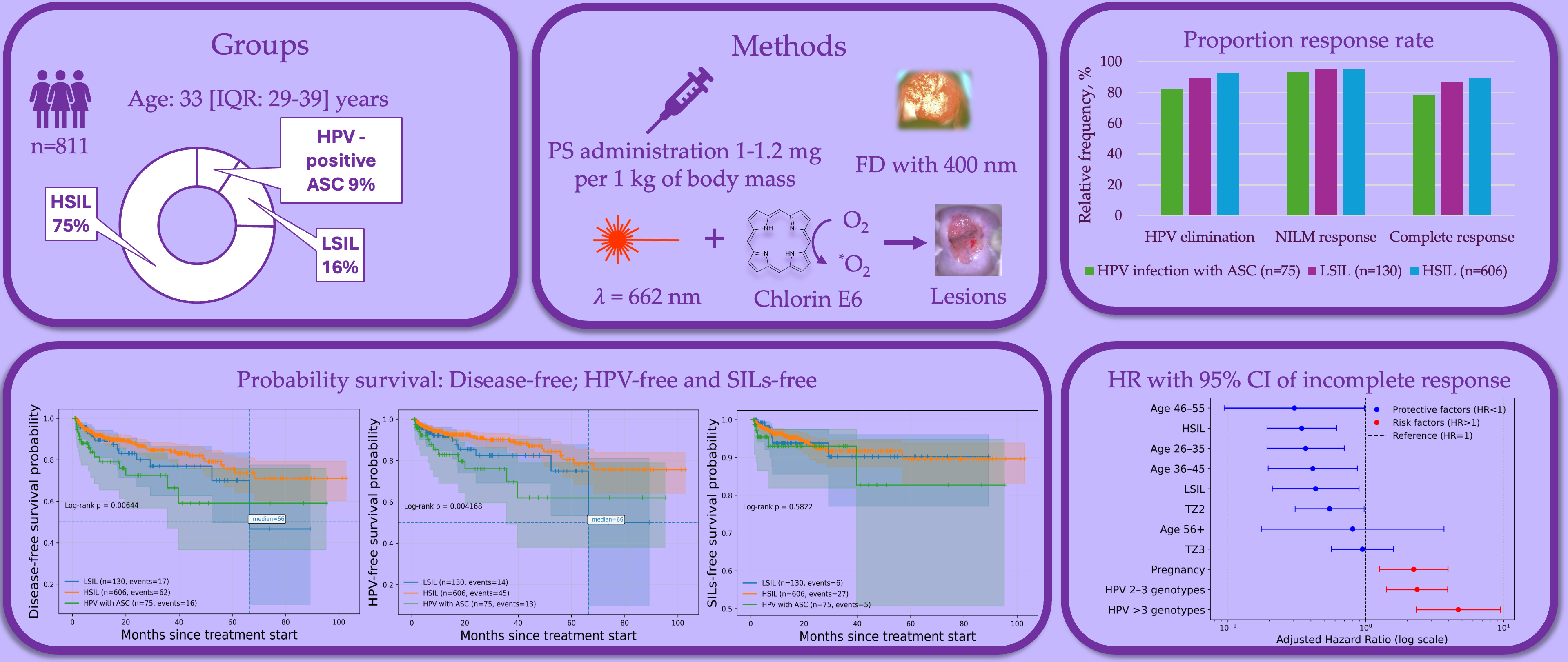

The 811 patients were treated by PDT and divided into the HPV infection with ASC (n=75; 9.2%), LSIL (n=130; 16%) and HSIL (n=606; 74.7%) groups. Patients with HSIL had CIN2 in 24.4% (n=198) of cases; CIN3 in 37.4% (n=303) and carcinoma in situ in 12.9% (n=105) of cases. The trial flowchart is presented in

Figure 1. The median follow-up period was 9.6 months (IQR: 3.3 – 23.4; min-max: from 1 to 103). Univariate analysis of baseline characteristics (demographic data, HPV status and viral load, LBC/histology results) is shown in

Table 1.

A total of three study groups, several clinically relevant differences were observed in demographic variables, reproductive history and HPV characteristics some of which were statistically significant.

Patients with HSIL were significantly older than participants with HPV and ASC (34.98.2 vs. 31.47.2, P<0.001) and LSIL (34.98.2 vs. 31.48 years, p<0.001). A similar pattern was seen in the age-stratified analysis: HSIL group had a higher proportion of participants aged 36-45 and 46 years compared with patients HPV infection with ASC and LSIL (p<0.001).

The age at sexual debut differed slightly across groups with significance detected only for mean values (

P=0.047). When we categorized age at sexual debut <18 vs. 18 years no statistically significant differences were observed (

P=0.24). Both in mean and median values, the number of sexual partners was higher in HSIL group (

P = 0.011) with a particularly notable difference when compared with Group I (3 [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5] vs. 4 [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7],

P=0.037). The categorical distribution of sexual partners (1, 2-3 and >3) was not significantly different (

P=0.13).

Pregnancy status varied significantly across the groups. A higher proportion of women in Group III reported a history of pregnancy compared with Groups I (72.9% vs. 58.3%, P=0.019) and II (72.9% vs. 57.6%, P=0.002). The number of pregnancies also differed between groups (P<0.001). However, categorized gravidity (1, 2-3, >3 pregnancies) did not show statistically significant group differences (P=0.15).

The distribution of transformation zone (TZ) types (TZ1, TZ2 and TZ3) was similar across all three groups with no significant differences detected (P=0.84).

HPV16 was the predominant genotype in all groups with the highest prevalence in Group III compared with Group I (67.7% vs. 50%, P=0.017) and Group II (67.7% vs. 47.9%, P<0.001). HPV18, HPV31 and HPV33 were detected less frequently and show comparable distributions. Patients with HSIL (Group III) had the highest proportion of single infections (51.5%), whereas Group II exhibited the highest proportion of single infection (41.5%). HPV-negative results were most common in group I and II (18.7 and 10.8%) and the least frequent in Group III (5.6%). Among individuals with multiple infections, the number of concurrent HPV types (2-3 vs. >3) did not differ significantly between groups (P=0.86).

Although mean viral load values showed considerable variability and were not significantly different (P=0.59), but median viral load was higher in Group II and Group III than in Group I (6.1 [5.4-7.1] and 6 [5.1-7] vs. 5.4 [4.5-6.1], P=0.043 for both comparison).

3.2. Comparison of Complete Response, HPV Clearance and Lesion Remission

Overall HPV clearance was 91.1% (n=739). The lowest rate of HPV clearance was in group of HPV infection with ASC (p=0.012). In pairwise comparing HPV infection with ASC and HSIL had a statistically significant differences (82.7% vs. 92.6%; p = 0.011).

Overall lesion efficacy was 95.3% (n=773). The equally lesion efficacy was for each group (p=0.68). Regression of cervical lesion was in 3.8% for HSIL and 0.8% for LSIL. Ineffective PDT was in 1.3% for HPV infection with ASC, 3.8% for LSIL and 0.7% for HSIL. Progression of cervical lesion was detected in 5.3% of cases for HPV infection with ASC.

Overall complete response was 88.3% (n=716). The highest rate of complete response was in HISL group (n=544; 89.8%) comparing with LSIL group (n=113; 86.9%) and HPV infection with ASC (n=59; 78.7%). In pairwise comparison complete response rate was statistically higher in HSIL group than HPV infection with ASC group (p=0.011).

Figure 2.

Overall response rate of HPV elimination, cytological outcome and complete response. ASC – atypical squamous cells; HPV – human papillomavirus; HSIL – high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; LSIL – low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion. *Difference between three groups; **Difference between HSIL and HPV infection with ASC groups.

Figure 2.

Overall response rate of HPV elimination, cytological outcome and complete response. ASC – atypical squamous cells; HPV – human papillomavirus; HSIL – high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; LSIL – low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion. *Difference between three groups; **Difference between HSIL and HPV infection with ASC groups.

3.3. Multivariate Analysis of Factors for Complete Response, HPV Clearance and Lesion Remission

Multivariate analysis of factors for complete response (CR), HPV clearance and lesion remission was performed using logistic regression with stepwise factors selection (

Table 2). Input predictors were age groups, age at sexual debut groups, number of sexual partners, pregnancy status, TZ types, HPV infection and grade of squamous intraepithelial lesion.

3.3.1. Complete Response

After adjustment for covariates, several factors were independently associated with odds of CR (

Table 3). Patients with aged 18-25 years had significantly higher odds of achieving CR compared with the other age groups (OR=2.18; 95% CI: 1.07-4.44; p=0.032). A TZ2 was also associated with increased odds of CR relative to TZ1 (OR=1.98; 95% CI: 1.06-3.69; p=0.033), whereas TZ3 showed no significant association. In contrast, pregnancy status was independently associated with a reduced likelihood of CR (OR=0.46; 95% CI: 0.25-0.86; p=0.014). The number of HPV genotypes exhibited a strong inverse dose-dependent association with CR. Compared with single HPV infection, infection with 2-3 HPV genotypes was associated with a significant reduction in CR odds (OR=0.44; 95% CI: 0.25-0.77; p=0.004) while infection with more than three HPV genotypes showed a more pronounced decrease (OR=0.16; 95% CI: 0.07-0.38; p<0.001). Baseline cytological diagnosis was also significantly associated with treatment outcomes. Compared with HPV-positive cases with ASC, both LSIL (OR=2.47; 95% CI: 1.10-5.54; p=0.029) and HSIL (OR=3.18; 95% CI: 1.65-6.12; p=0.001) were associated with increased odds of CR.

ROC analysis demonstrated moderate discriminative performance with an AUC of 0.69 (95% CI: 0.64-0.74; p<0.001). At the optimal cutoff probability (P=0.89, Youden index) the model of logistic regression achieved a sensitivity of 61% and specificity of 62.8%.

Figure 3.

ROC curves of (a) complete response, (b) HPV clearance and (c) lesion remission and adjusted odds ratio for (d) complete response, (e) HPV clearance and (f) lesion remission.

Figure 3.

ROC curves of (a) complete response, (b) HPV clearance and (c) lesion remission and adjusted odds ratio for (d) complete response, (e) HPV clearance and (f) lesion remission.

3.3.2. HPV Clearance

After adjustment, infection with more than three HPV genotypes was strongly associated with reduced odds of HPV clearance (OR=0.18; 95% CI: 0.08-0.42; p<0.001). Infection with 2-3 HPV genotypes was not significant associated with HPV clearance. Baseline cytology diagnosis demonstrated an independent association with outcome. Compared with HPV-positive cases with ASC, HSIL was associated with significantly higher odds of HPV clearance (OR=3.07; 95% CI: 1.53-6.13; p=0.002), while LSIL results did not reach statistical significance.

ROC analysis showed limited but statistically significant discrimination with an AUC of 0.62 (95% CI: 0.55-0.67; p<0.001). At the optimal cutoff probability (P=0.94, Youden index) the model of logistic regression achieved a sensitivity of 60.3% and specificity of 55.4%.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the relationship between predictors and the odds of HPV clearance.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the relationship between predictors and the odds of HPV clearance.

| Predictors |

Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

| COR; 95% CI |

P value |

AOR; 95% CI |

P value |

SILs grade:

LSIL

HSIL |

1.94; 0.83 – 4.54

2.90; 1.47 – 5.74 |

0.125

0.002* |

2.13; 0.90 – 5.06

3.07; 1.53 – 6.13 |

0.087

0.002 |

Multiple HPV infection:

2-3 genotypes

>3 genotypes |

0.90; 0.46 – 1.75

0.18; 0.08 – 0.43 |

0.755

< 0.001* |

0.93; 0.47 – 1.82

0.18; 0.08 – 0.42 |

0.821

< 0.001 |

3.3.3. Lesion Remission

Lesion remission was associated with multiple HPV infection compared with single HPV infection. Infection with more than 3 HPV genotypes (AOR=0.25; 95% CI: 0.08-0.78; p=0.017) and 2-3 HPV genotypes (AOR=0.47; 95% CI: 0.22-0.99; p=0.047) showed a strong negative association in the odds of lesion remission.

ROC analysis showed low but statistically significant discrimination with an AUC of 0.60 (95% CI: 0.51-0.69; p=0.006). At the optimal cutoff probability (P=0.96, Youden index) the model of logistic regression achieved a sensitivity of 78.2% and specificity of 40.5%.

Table 5.

Characteristics of the relationship between predictors and the odds of CR.

Table 5.

Characteristics of the relationship between predictors and the odds of CR.

| Predictors |

Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

| cOR; 95% CI |

P value |

aOR; 95% CI |

P value |

Multiple HPV infection:

2-3 genotypes

>3 genotypes |

0.47; 0.22 – 0.99

0.25; 0.08 – 0.78 |

0.047

0.017 |

0.47; 0.22 – 0.99

0.25; 0.08 – 0.78 |

0.047

0.017 |

3.4. Time-to-Event for Incomplete Response, Persistent HPV Infection and Lesion Persistent

Time-to-event analyses were performed to evaluate predictors of incomplete response, persistent HPV infection and persistent lesion following PDT. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were compared using likelihood ratio testing and multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were applied to identify independent predictors. Input predictors were age groups, age at sexual debut groups, number of sexual partners, pregnancy status, TZ types, HPV infection and grade of SILs.

3.4.1. Incomplete Response

For incomplete response, Kaplan-Meier analysis (

Figure 4a) revealed significant differences in disease-free survival across age groups, pregnancy status, number of HPV genotypes, TZ types and baseline cytology (p<0.001). The median time to incomplete response was reached only in patients aged 18–25 years, with a median of 66.4 months, whereas the median was not reached in patients aged 26–35, 36–45, and 46–55 years. In patients aged ≥56 years, the median was also not reached. According to transformation zone type, the median time to incomplete response was not reached in all TZ groups; however, earlier declines in response-free survival were observed in TZ1 compared with TZ2. Pregnant patients demonstrated earlier occurrence of incomplete response. In this subgroup, the median time to incomplete response was 61.0 months, whereas the median was not reached in non-pregnant patients. A pronounced effect was observed for HPV multiplicity. Patients infected with more than three HPV genotypes reached a median time to incomplete response of 61.0 months, while the median was not reached in patients with single-genotype or 2–3 genotype infections. Baseline cytology was also associated with time-to-event outcomes. The median time to incomplete response was not reached in patients with LSIL and HSIL, whereas earlier events were observed in patients with HPV-positive atypical squamous cells.

In multivariable Cox regression (

Figure 4d and

Table 6), age 26–35 years (HR = 0.37; 95% CI: 0.19–0.70), 36–45 years (HR = 0.41; 95% CI: 0.20–0.87), and 46–55 years (HR = 0.30; 95% CI: 0.09–0.98) were independently associated with a reduced risk of incomplete response. TZ2 was associated with lower hazard compared with TZ1 (HR = 0.55; 95% CI: 0.31–0.97). Pregnancy increased the risk of incomplete response (HR = 2.23; 95% CI: 1.26–3.95). Infection with 2–3 HPV genotypes (HR = 2.36; 95% CI: 1.42–3.93) and more than three genotypes (HR = 4.70; 95% CI: 2.33–9.48) significantly increased risk in a dose-dependent manner. Baseline LSIL and HSIL were associated with reduced hazards compared with HPV-positive ASC.

3.4.2. Persistent HPV Infection

For persistent HPV infection, Kaplan–Meier curves (

Figure 4b) demonstrated significant stratification by age, pregnancy status, HPV multiplicity, and baseline diagnosis (

p < 0.001). Patients aged 18–25 years demonstrated earlier HPV persistence, whereas the median HPV-free survival was not reached in patients aged 26–35 and 36–45 years. In older age groups, median estimates were also not reached. Pregnant patients exhibited earlier HPV persistence, with a median HPV-free survival of approximately 58.7 months, while the median was not reached in non-pregnant patients. HPV multiplicity had a strong impact on median survival. Patients with more than three HPV genotypes reached a median time to HPV persistence of 49.8 months, whereas the median was not reached in patients with single-genotype or 2–3 genotype infections. By baseline cytology, the median HPV-free survival was not reached in patients with LSIL and HSIL, while earlier HPV persistence was observed in patients with HPV-positive ASC.

In Cox regression (

Figure 4e and

Table 7), age 26–35 years (HR = 0.43; 95% CI: 0.21–0.90) and 36–45 years (HR = 0.37; 95% CI: 0.16–0.89) were associated with reduced risk of persistent HPV infection. Pregnancy increased the hazard of HPV persistence (HR = 1.96; 95% CI: 1.03–3.72). Infection with more than three HPV genotypes was the strongest predictor of HPV persistence (HR = 5.01; 95% CI: 2.41–10.42). Baseline LSIL and HSIL were associated with significantly reduced hazards of HPV persistence.

3.4.3. Lesion Persistent

For lesion persistent, Kaplan–Meier (

Figure 4c) analysis showed significant differences in lesion-free survival depending on HPV multiplicity, pregnancy status, and age group. Patients with more than three HPV genotypes reached a median time to lesion persistence of 52.3 months, whereas the median was not reached in patients with single-genotype infection. Pregnancy status was associated with earlier lesion persistence. In pregnant patients, the median lesion-free survival was approximately 54.1 months, while the median was not reached in non-pregnant patients. Age-stratified analysis showed that patients aged 26–35 years did not reach the median lesion-free survival during follow-up, whereas earlier events were observed in younger patients.

In multivariable Cox regression (

Figure 4f and

Table 8), infection with 2–3 HPV genotypes (HR = 2.61; 95% CI: 1.23–5.52) and more than three genotypes (HR = 4.21; 95% CI: 1.44–12.31) independently increased the risk of persistent SIL. Pregnancy was associated with increased SIL persistence (HR = 2.40; 95% CI: 1.01–5.70), while age 26–35 years was associated with reduced risk (HR = 0.33; 95% CI: 0.13–0.83).

4. Discussion

In this study, we evaluated PDT as a treatment for HPV-related cervical lesions: HPV infection with ASC, LSIL and HSIL. The results demonstrate that PDT is highly effective in achieving both HPV clearance and lesion remission, corroborating and extending findings from prior research. We observed an overall CR rate of 88.3% in our cohort (716/811 patients), defined stringently as concurrent clearance of high-risk HPV and regression to normal cytology. This included HPV clearance in 91.1% of patients and lesion remission in 95.3%. Notably, the therapeutic efficacy was high even for patients with high-grade disease: among women with HSIL (CIN2/3 or carcinoma in situ) PDT achieved a CR in 89.8% of cases, which is remarkably consistent with clearance rates reported for surgical excision in this population [

14,

15]. Our finding that the HSIL group had the highest response proportion (89.8% CR) aligns with several studies indicating that PDT can successfully eradicate severe dysplasia. For example, Hillemanns et al. reported a 95% response in CIN2 with hexaminolevulinate-PDT in a phase II trial [

16], and more recent comparative studies have shown 82–100% remission of CIN2/3 lesions with ALA-PDT, comparable to conization [

14]. Importantly, none of the HSIL cases in our series showed progression to invasive cancer during follow-up, reinforcing that PDT, when effective, halts disease progression in high-grade lesions.

Patients with LSIL and those with only atypical squamous cells (ASC-US/ASC-H with positive HPV) also benefited substantially from PDT in our study, though their CR rates were somewhat lower (87% for LSIL and 79% for HPV positive with ASC). The slightly reduced success in the mild abnormality groups may reflect the challenge in treating low-grade infections that might be multifocal or the fact that some low-grade changes can persist due to reinfection. It is worth noting, however, that the lesion remission rate in LSIL was very high (99.2% showed no residual LSIL cytology after PDT) with only <1% showing any lesion persistence or progression. Our LSIL outcomes are consistent with other reports of proactive treatment in CIN1. Li et al. observed a 94.8% pathological regression in LSIL at 6 months post-ALA PDT [

11], and a Brazilian trial of MAL-PDT noted 75% of CIN1 cleared at 2 years (versus 57% in a placebo group) [

17]. Historically, some randomized studies found no advantage of PDT over observation in CIN1 (owing to high spontaneous regression) [

16]. Our data, however, along with recent cohorts from China, suggest that for patients who desire active treatment of persistent LSIL or concomitant HR-HPV infection, PDT can effectively eliminate low-grade lesions and the virus. This proactive approach may alleviate patient anxiety and potentially reduce the risk of those 10–20% of LSIL that would otherwise progress [

11].

One of the strengths of our study is the investigation of clinical and demographic factors that might influence PDT success. Multivariable analysis identified several independent predictors of treatment outcome, and these findings generally concur with trends noted in the literature. Perhaps the most significant factor was HPV infection multiplicity. Patients harboring multiple high-risk HPV genotypes had substantially lower odds of CR and higher hazard of treatment failure over time, in a dose-dependent fashion (adjusted OR 0.16 for >3 types vs single-type HPV infection). Similarly, in our time-to-event analysis, infection with ≥2 HPV strains markedly increased the risk of an “incomplete response” event (adjusted HR 2.36 for 2–3 types and 4.70 for >3 types). These results reinforce a consensus that co-infection with multiple HPV strains is a key risk factor for therapeutic failure. Multiple HPV infections have been shown in other studies to predict lower clearance rates and higher recurrence after treatment [

14]. For instance, Wang et al. noted that having more than one HPV strain was associated with suboptimal 6-month outcomes after PDT (OR < 0.1 for cure) [

14]. In the context of genital warts (another HPV disease treated with PDT), patients with mixed low- and high-risk HPV required prolonged therapy and had lower virological clearance (50% clearance for high-risk vs ~77% for low-risk HPV) [

18], again indicating that high-risk/multiple HPV infections are more resilient [

18]. Biologically, multiple infections could signify a heavier viral load or more compromised local immunity, thus making eradication by a single modality more challenging. Clinically, our findings highlight that patients with multiple HPV genotypes may need closer follow-up and possibly adjunctive measures (such as immunotherapy or repeat PDT sessions) to achieve complete clearance [

14].

Another factor affecting PDT outcomes was the cervical TZ type, which relates to lesion location and accessibility. We found that lesions with a TZ2 (partially endocervical, but still visible) responded better to PDT than those with a TZ1 (fully exocervical). TZ2 was associated with higher odds of CR (OR=1.98) and a significantly lower hazard of recurrence (HR 0.55 vs TZ1). Lesions involving the endocervical canal more deeply (TZ3) showed a trend toward lower response as well, though in our logistic model TZ3 was not statistically different from TZ1. These observations concord with clinical experience that endocervical extension can hinder treatment efficacy. A recent study by Qian et al. explicitly identified cervical canal involvement as an independent risk factor for persistent HPV after ALA-PDT for HSIL [

10]. In their cohort, patients whose HSIL extended into the endocervix had significantly higher rates of HPV persistence at 3 months (i.e., reduced clearance) [

10]. Consistently, a specialized analysis of PDT for HSIL confined to the endocervical canal noted that while PDT can still be effective, careful delivery (e.g., intracervical fiber optic irradiation) is required [

15]. The clinical implication is that women with TZ3 or largely endocervical lesions might benefit from modified PDT techniques (such as using a intrauterine light applicator or increasing photosensitizer incubation time) to ensure adequate treatment of the transformation zone. It may also be prudent to monitor such patients more rigorously post-PDT, as our survival curves suggested earlier loss of response in TZ3 lesions compared to more ectocervical ones.

Patient age and reproductive history also emerged as relevant factors, though their influence is nuanced. In our logistic regression, younger age (particularly 18–25 years) was associated with higher odds of initial CR. This could be attributed to a more robust tissue regenerative capacity or immune response in younger patients, and indeed other authors have noted that ALA-PDT is “particularly suitable for young women” with CIN because it spares fertility and appears effective in this group [

10]. Paradoxically, however, our longitudinal analysis found that the youngest patients had the shortest disease-free intervals: women under 25 experienced incomplete-response events sooner than older age groups (median 66 months for age 18–25 vs not reached for older groups). Cox modeling confirmed that patients aged 26–45 had significantly lower hazards of recurrence than those under 25. One interpretation of this discrepancy is that while young patients respond well initially to PDT, they may be at higher risk of reinfection or relapse due to behavioral factors and possibly a longer remaining lifespan in which to acquire new HPV infections. Additionally, younger women’s cervical epithelium might be more prone to HPV re-entry. In contrast, women over 30, once cleared, might have lifestyle or biological factors that make re-infection less frequent. Previous studies have not uniformly reported age as a determinant of PDT outcome, so our findings contribute novel insight that warrants further investigation. They suggest counseling younger patients on diligent HPV prevention post-therapy.

Pregnancy status was associated in our study with a lower likelihood of complete response to PDT (adjusted OR=0.46) and a higher risk of recurrence (HR=2.23). Women who had ever been pregnant were more prone to treatment failure than nulliparous women. This factor is less documented in the literature; however, it could be hypothesized that cervical anatomical changes from childbirth (such as cervical scarring or glandular involvement in parous women) might impede uniform photosensitizer uptake or light distribution. Moreover, pregnancy and the postpartum period have immunological and hormonal shifts that could affect HPV persistence. One could consider that women with prior pregnancies tend to be slightly older on average, but in our multivariate model age was adjusted for separately. Thus, parity appears to independently correlate with poorer PDT outcomes in our data. This finding should be interpreted cautiously but prompts further research for instance, examining if postpartum timing or breastfeeding status influences PDT efficacy, or if cervical microenvironment differences in parous women play a role.

Collectively, the risk factor analysis from our study dovetails with prior evidence on what influences cervical disease outcomes and highlights important considerations for clinical practice. HPV genotype merits a brief discussion as well. While single-genotype infections had better outcomes than multi-genotype infections, we did not find that any specific high-risk type (HPV16 vs HPV18) was significantly associated with treatment success in a multivariate sense. Earlier studies suggested HPV16 may be the most persistent and difficult to eradicate type [

17]. Interestingly, in the context of PDT, some reports have shown no significant difference in clearance between HPV16 and other types when adequate follow-up is provided [

11]. For example, in the LSIL PDT study from Shanghai, HPV16/18-positive cases had a slightly higher clearance at 3 months than others, and by 6 months their clearance (94.9%) was statistically equivalent to non-16/18 cases (92.3%) [

11]. Our high overall HPV clearance rate (91%) suggests that PDT, especially with a broad-acting photosensitizer and proper technique, can eliminate even the traditionally recalcitrant genotypes. This is a significant advantage, as HPV eradication is correlated with reduced recurrence and progression risk [

14,

15]. Indeed, the ability of PDT to

simultaneously treat the lesion and clear underlying HPV infection is a distinguishing benefit over some surgical treatments (which remove diseased tissue but do not address field infection in adjacent epithelium). This “field clearance” effect of PDT may explain the low recurrence rates observed. Our Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that the vast majority of patients remained HPV-free and lesion-free over the follow-up period; median time to recurrence was not reached in most subgroups, indicating durable responses. This is in line with other studies where long-term follow-up after PDT has shown sustained remission. In a 2-year follow-up study, Inada et al. found only 10% of treated CIN2/3 patients experienced any recurrence within two years, and 0% progressed to cancer, whereas 90% remained disease-free [

17]. Even for CIN1, >75% had durable clearance at 2 years, with the remainder mostly showing only minor persistent lesions [

17]. Our study’s median follow-up (~9.6 months, with some patients followed up to 8+ years) shows similarly encouraging durability, with only a small fraction of patients experiencing lesion persistence or reappearance. Furthermore, when comparing PDT to standard therapies, long-term efficacy appears comparable. Liu et al. reported no significant difference in 2-year cure and HPV eradication rates between PDT and LEEP for HSIL (both ~95% HPV clearance by 24 months) [

15], but the PDT group avoided the complications inherent to excisional surgery. This underscores that PDT’s clinical benefits are not achieved at the cost of higher recurrence – on the contrary, PDT may reduce recurrences by sanitizing the tissue of HPV infection beyond the immediate lesion.

PDT was generally well tolerated in our cohort with no sever systemic complications. Hower, cervical canal atresia was observed in 6 patients (0.74%), representing a clinically relevant late local adverse event. All affected patients underwent cervical dilatation at 2 months after PDT. Patients adhered to post-PDT photosensitivity precautions without incident, and only minimal transient side effects were noted, such as mild pelvic cramping or discharge consistent with epithelial sloughing. This match reports from other centers: Qian et al. noted no serious adverse reactions in 40 HSIL patients treated with ALA-PDT – only slight transient discomfort in a few cases [

10]. Randomized trials have similarly found PDT to be well-tolerated; Hillemanns et al. reported that HAL-PDT was “well accepted” by patients, with only self-limited local effects and no significant laboratory or systemic safety issues [

16]. Compared to surgery, PDT avoids anesthesia risks and intraoperative or immediate postoperative complications. Our comparative observations (though non-randomized) echo those of Wang et al., who documented a “notably lower incidence of side effects” in PDT vs conization [

14]. The chief drawbacks of PDT noted were logistical in Wang’s study, PDT had a longer total treatment duration and higher cost than surgery [

14]. In our setting, PDT was delivered in an outpatient context and, while the upfront cost of photosensitizer and laser time is considerable, it potentially offsets costs of surgical theater use and management of surgical complications. Nevertheless, economic analyses will be important in the future to justify widespread adoption of PDT. From the patient’s perspective, the avoidance of fertility-threatening complications and the relatively atraumatic experience of PDT (no excisional pain, minimal downtime) are significant advantages that improve quality of life.

The clinical implications of our findings are significant. PDT can now be considered a valid therapeutic option for HPV-related cervical lesions, from low-grade abnormalities to high-grade precancerous lesions, especially in populations where fertility preservation or surgical risk avoidance is a priority. Young women with HSIL, in particular, form a key demographic who may benefit from PDT over conization [

10,

14]. The evidence from our study and others indicates that PDT offers comparable efficacy to excisional treatment in eradicating lesions and HPV [

14,

15], while conferring added benefits in terms of safety and cervical conservation. Thus, in a setting with the necessary expertise and equipment, PDT could be presented to patients as an alternative to LEEP/cone biopsy. It will be important for clinicians to stratify patients based on the risk factors discussed: for example, a patient with a single HPV16 infection, exophytic HSIL on the ectocervix, and no prior pregnancies appears to be an ideal PDT candidate with a high likelihood of cure. Conversely, a patient with multifocal lesions extending into the canal, infected by HPV16/18/52 simultaneously, and with a history of multiple pregnancies might have a relatively lower success probability with PDT alone; such a patient could still undergo PDT but with counseling that repeat treatments or a backup excisional procedure might be needed if clearance is not achieved. Our data, coupled with the immunological findings from Ju et al., also hint at the possibility of combining PDT with other modalities to improve outcomes in tougher cases [

13]. For instance, therapeutic HPV vaccines or immune checkpoint modulators might be used alongside PDT to boost the host response against HPV-infected cells. Since PDT can induce immunogenic cell death and enhance antigen presentation, it could synergize with immunotherapy an exciting avenue for future research.

Looking forward, there are several directions for future work and improvements in the field of PDT for cervical disease. First, standardized, large-scale clinical trials are needed to further validate efficacy and optimize protocols. A randomized controlled trial comparing PDT vs LEEP in a Western population would be valuable and could pave the way for international guidelines to incorporate PDT. Such trials should also evaluate long-term outcomes (5-year recurrence and perhaps even cancer incidence) to fully establish durability. Second, studies should focus on protocol optimization: determining the ideal photosensitizer, the optimal dosing and incubation time, and whether multiple treatment sessions yield better outcomes than a single session for high-grade lesions. For example, the difference between our approach (chlorin e6 intravenous PDT in one session) and others (fractionated ALA-PDT in multiple weekly sessions) needs to be delineated in terms of efficacy, patient compliance, and cost. Third, given the importance of treating endocervical disease, technology development is warranted such as improved intra-cervical light delivery devices, or endoscopic/light-diffusing fiber techniques to ensure the full transformation zone is treated even in TZ3 cases. Additionally, adjunctive mechanical removal of mucus or acetowhite mapping under colposcopy before PDT could help target occult lesions. Fourth, exploring combination therapy is a promising frontier: combining PDT with antiviral or immune-based therapies (imiquimod, interferon, therapeutic vaccines) might significantly improve clearance of stubborn infections and further reduce recurrence. There is also interest in photodynamic diagnosis – using fluorescence to delineate lesions which was part of our protocol to confirm photosensitizer uptake; this could be expanded to guide more selective treatment and spare normal areas. Lastly, cost-effectiveness and implementation research will be critical. Training programs for PDT, cost reduction of photosensitizers, and ensuring access in low-resource settings will determine how widely this therapy can be adopted. Interestingly, PDT is relatively low-cost in some analyses because it can be done in-office with minimal disposables; as technology matures, it may become an affordable option even in middle-income regions, complementing the WHO strategy to eliminate cervical cancer through not just vaccination and screening, but also effective treatment of pre-cancers.