Submitted:

25 December 2025

Posted:

26 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction and Historical Context

1.1. Historical Development

1.2. Mathematical Formulation

1.3. Classification of First-Order ODEs

| Type | General Form | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Separable | Variables can be separated | |

| Linear | Linear in y and | |

| Exact | ||

| Bernoulli | Nonlinear but reducible to linear | |

| Homogeneous | Invariant under scaling |

1.4. Modern Significance

- Population dynamics in ecology

- Chemical kinetics and reaction rates

- Electrical circuits (RC, RL)

- Pharmacokinetics and drug metabolism

- Economic growth models

- Heat transfer and diffusion processes

- Machine learning (gradient descent dynamics)

2. Analytical Solution Methods: Comprehensive Treatment

2.1. Separation of Variables with Advanced Examples

2.2. Linear Equations: Theory and Applications

2.3. Exact Equations and Integrating Factors

2.4. Bernoulli Equations and Transformations

2.5. Riccati Equations

3. Qualitative Analysis and Stability Theory

3.1. Autonomous Equations and Phase Line Analysis

3.2. Linear Stability Analysis

- : asymptotically stable

- : unstable

- : linearization inconclusive

3.3. Lyapunov Functions for Nonlinear Stability

- (1)

- and for

- (2)

- near

3.4. Bifurcation Analysis

- For : stable, unstable

- For : unstable, stable

- At : bifurcation point

4. Canonical Models: Detailed Analysis

4.1. Exponential Growth and Decay

- Population growth ()

- Radioactive decay ()

- Compound interest (k as interest rate)

| Process | Formula | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Half-life | Carbon-14: years | |

| Doubling time | Bacteria: minutes |

4.2. Logistic Growth: Complete Analysis

4.3. Newton’s Law of Cooling: Extended Models

4.4. Gompertz Growth Model

5. Numerical Methods: Algorithms and Implementation

5.1. Euler’s Method: Error Analysis

5.2. Runge-Kutta Methods Family

5.2.1. Second-Order Methods (RK2)

- Modified Euler:

- Heun’s method:

5.2.2. Classical Fourth-Order Runge-Kutta (RK4)

5.3. Stiff Equations and Implicit Methods

5.3.1. Backward Euler Method

5.3.2. Trapezoidal Rule (Crank-Nicolson)

5.4. Adaptive Step Size Control

6. Advanced Topics and Extensions

6.1. Allee Effect Models

6.2. Delay Differential Equations (DDEs)

6.3. Stochastic Differential Equations (SDEs)

6.4. Fractional Differential Equations

7. Applications Across Disciplines

7.1. Ecology and Population Dynamics

- Lotka-Volterra predator-prey models

- Metapopulation dynamics

- Species invasion models

- Harvesting and management strategies

7.2. Biomedical Sciences

7.2.1. Pharmacokinetics: One-Compartment Model

7.2.2. Epidemiology: SI Model

7.3. Physics and Engineering

7.3.1. Electrical Circuits

7.3.2. Mechanics with Drag

7.4. Economics and Finance

7.4.1. Solow Growth Model

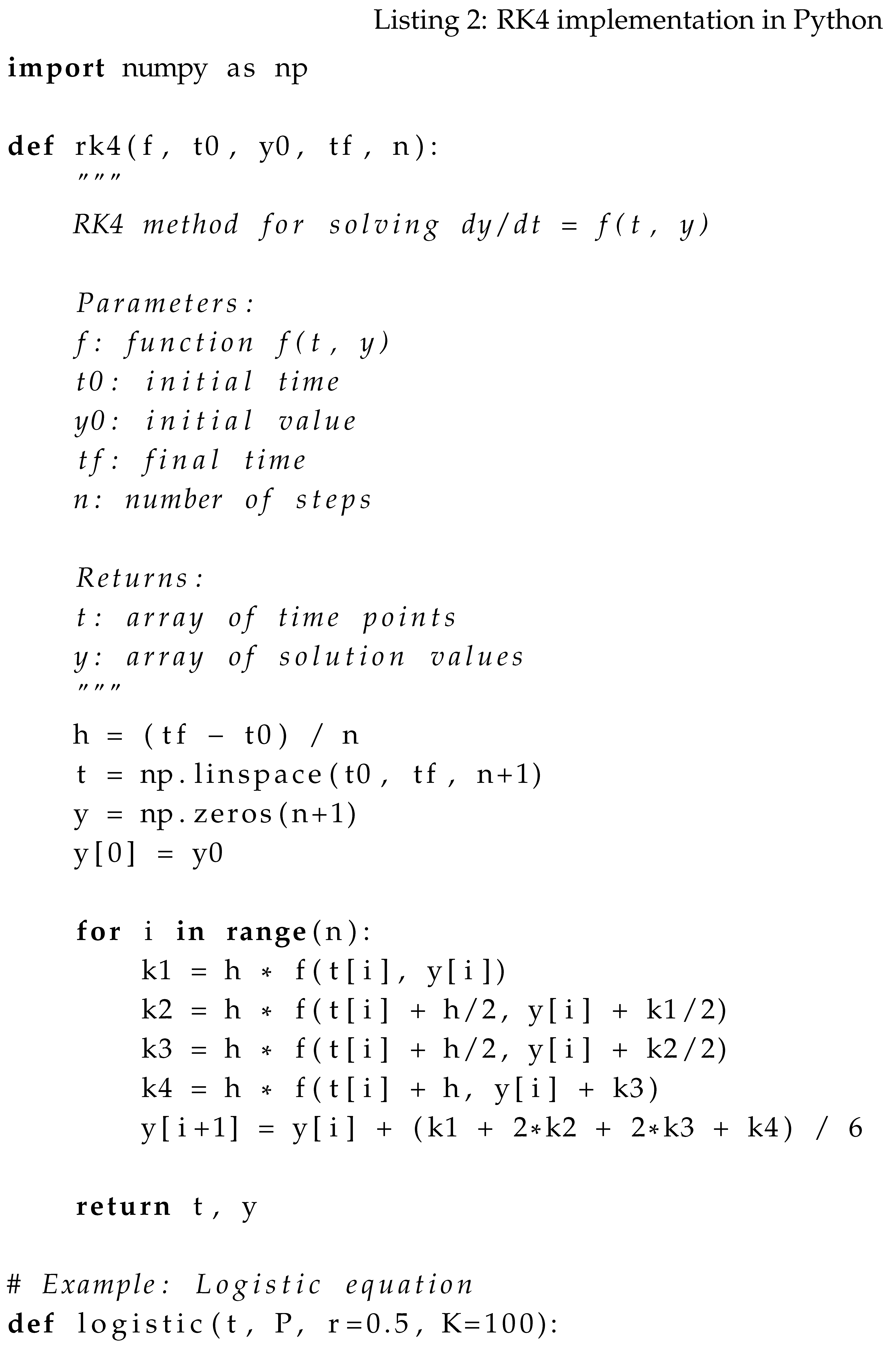

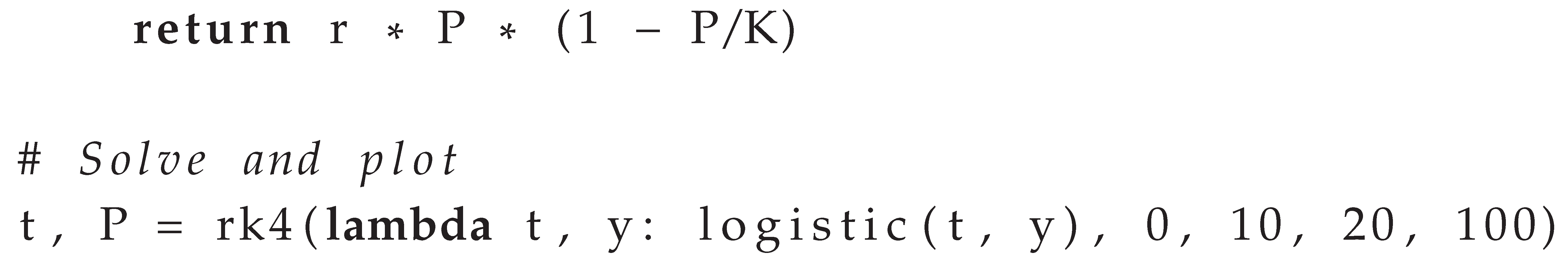

8. Computational Implementation Examples

8.1. Python Implementation of RK4

8.2. MATLAB Implementation for Stiff Problems

9. Conclusions and Future Directions

- Machine Learning Integration: Neural ODEs that parameterize with neural networks

- High-Dimensional Systems: Applications in data science and network dynamics

- Stochastic Methods: Improved numerical methods for SDEs

- Hybrid Systems: Combining continuous ODEs with discrete events

- Uncertainty Quantification: Propagating parameter uncertainties through ODE models

Appendix A. Useful Integrals and Transformations

Appendix A.1. Common Integrals

Appendix A.2. Integration by Parts Formula

Appendix B. Stability Criteria Summary

| Equilibrium Type | Condition | Stability |

|---|---|---|

| Node | , real | Asymptotically stable |

| Source | , real | Unstable |

| Saddle | , | Semistable |

| Degenerate | Higher-order analysis |

Appendix C. Appendix C: Numerical Methods Error Comparison

| Method | Order | Stability | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward Euler | 1 | Conditional | Low |

| Backward Euler | 1 | Unconditional | Medium (implicit) |

| Trapezoidal Rule | 2 | Unconditional | Medium (implicit) |

| Heun’s Method | 2 | Conditional | Medium |

| Classical RK4 | 4 | Conditional | High |

| Adams-Bashforth | Variable | Conditional | Medium |

References

- Brauer, F.; Castillo-Chavez, C. Mathematical Models in Population Biology and Epidemiology; Springer Science & Business Media, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, M. W.; Smale, S.; Devaney, R. L. Differential Equations, Dynamical Systems, and an Introduction to Chaos; Academic Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Strogatz, S. H. Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos: With Applications to Physics, Biology, Chemistry, and Engineering; CRC Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Trench, W. F. Elementary Differential Equations with Boundary Value Problems; Trinity University, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, W. E.; DiPrima, R. C.; Meade, D. B. Elementary Differential Equations and Boundary Value Problems; John Wiley & Sons, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Butcher, J. C. Numerical Methods for Ordinary Differential Equations; John Wiley & Sons, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ascher, U. M.; Petzold, L. R. Computer Methods for Ordinary Differential Equations and Differential-Algebraic Equations; SIAM, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein-Keshet, L. Mathematical Models in Biology; SIAM, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J. D. Mathematical Biology: I. An Introduction; Springer, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kloeden, P. E.; Platen, E. Numerical Solution of Stochastic Differential Equations; Springer, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, J. K.; Kocak, H. Dynamics and Bifurcations; Springer Science & Business Media, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Holm, S. Fractional Derivative Modeling in Mechanics and Engineering; Springer, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shampine, L. F. Numerical Solution of Ordinary Differential Equations; Chapman and Hall, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Keshava, R. Ordinary Differential Equations: Principles and Applications; Tata McGraw-Hill, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, V. I. Ordinary Differential Equations; Springer, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Coddington, E. A.; Levinson, N. Theory of Ordinary Differential Equations; McGraw-Hill, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, P. Ordinary Differential Equations; SIAM, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, J. K. Ordinary Differential Equations; Krieger Publishing Company, 1980. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).