Submitted:

25 December 2025

Posted:

26 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

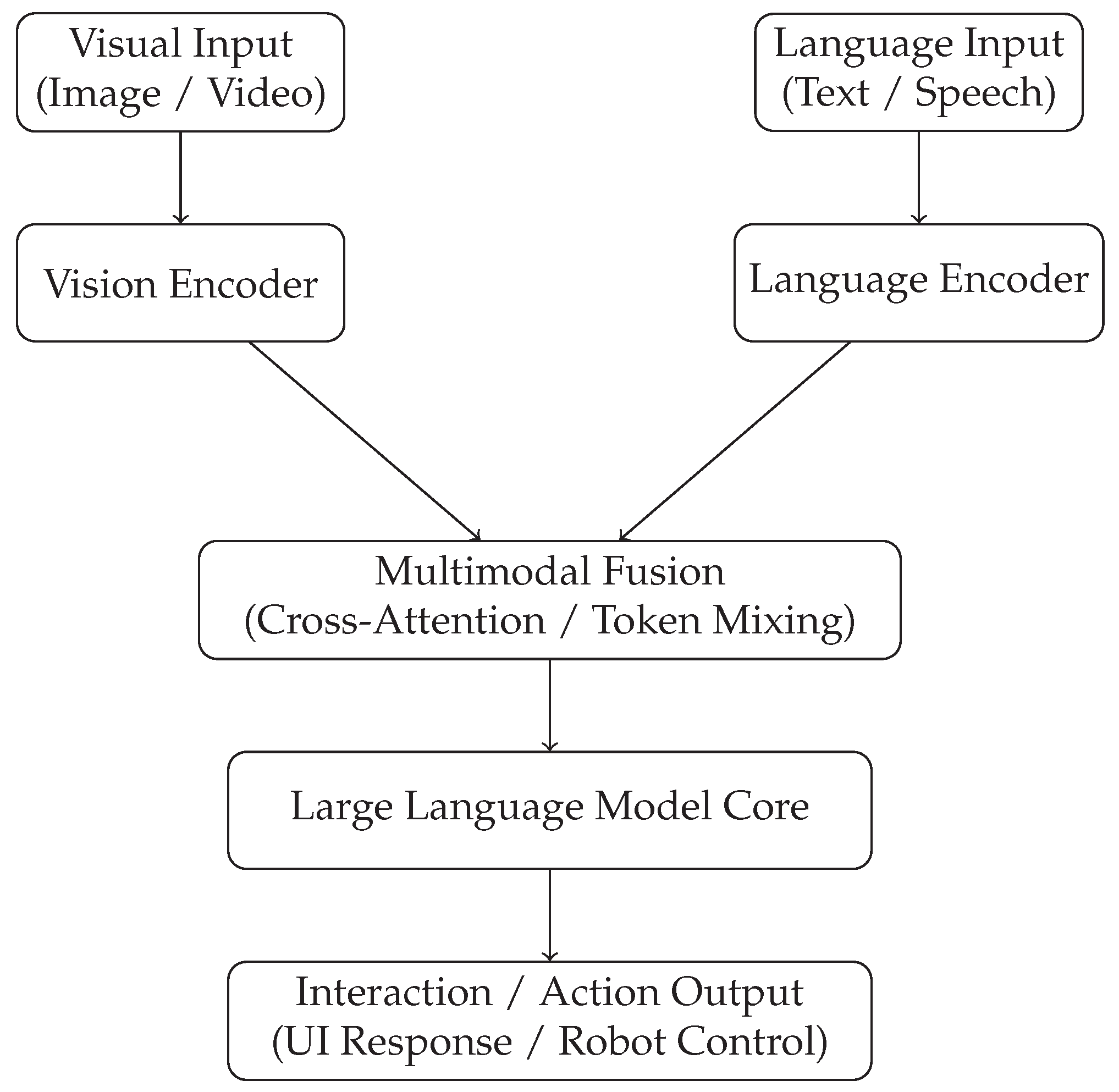

2. Foundations of Multimodal Large Vision–Language Models

2.1. Problem Formulation and Multimodal Representation

2.2. Vision Encoders

2.3. Language Models and Autoregressive Generation

2.4. Cross-Modal Alignment and Fusion

2.5. Training Objectives and Optimization

2.6. Grounding, Action, and Decision-Making

2.7. Discussion

3. Architectural Paradigms and System Design of LVLMs

4. Applications in Human–Computer Interaction and Robotics

5. Challenges, Limitations, and Open Research Problems

6. Future Directions and Research Opportunities

7. Conclusions

References

- Peng, B.; Li, C.; He, P.; Galley, M.; Gao, J. Instruction tuning with gpt-4. arXiv:2304.03277 2023.

- Overbay, K.; Ahn, J.; Park, J.; Kim, G.; et al. mRedditSum: A Multimodal Abstractive Summarization Dataset of Reddit Threads with Images. In Proceedings of the The 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2023.

- Sun, L.; Liang, H.; Wei, J.; Sun, L.; Yu, B.; Cui, B.; Zhang, W. Efficient-Empathy: Towards Efficient and Effective Selection of Empathy Data. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.01937 2024.

- Feng, J.; Sun, Q.; Xu, C.; Zhao, P.; Yang, Y.; Tao, C.; Zhao, D.; Lin, Q. MMDialog: A Large-scale Multi-turn Dialogue Dataset Towards Multi-modal Open-domain Conversation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2023, pp. 7348–7363.

- Du, Y.; Guo, H.; Zhou, K.; Zhao, W.X.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Cai, M.; Song, R.; Wen, J.R. What makes for good visual instructions? synthesizing complex visual reasoning instructions for visual instruction tuning. arXiv:2311.01487 2023.

- Farnebäck, G. Two-frame motion estimation based on polynomial expansion. In Proceedings of the Image Analysis: 13th Scandinavian Conference, SCIA 2003 Halmstad, Sweden, June 29–July 2, 2003 Proceedings 13. Springer, 2003, pp. 363–370.

- Broder, A.Z. On the resemblance and containment of documents. In Proceedings of the Proceedings. Compression and Complexity of SEQUENCES 1997 (Cat. No. 97TB100171). IEEE, 1997, pp. 21–29.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. NeurIPS 2017.

- Marino, K.; Rastegari, M.; Farhadi, A.; Mottaghi, R. Ok-vqa: A visual question answering benchmark requiring external knowledge. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/cvf conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019, pp. 3195–3204.

- Jing, L.; Li, R.; Chen, Y.; Jia, M.; Du, X. FAITHSCORE: Evaluating Hallucinations in Large Vision-Language Models. arXiv:2311.01477 2023.

- Kothawade, S.; Beck, N.; Killamsetty, K.; Iyer, R. Similar: Submodular information measures based active learning in realistic scenarios. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 18685–18697.

- Gu, J.; Meng, X.; Lu, G.; Hou, L.; Minzhe, N.; Liang, X.; Yao, L.; Huang, R.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, X.; et al. Wukong: A 100 million large-scale chinese cross-modal pre-training benchmark. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 26418–26431.

- Mangalam, K.; Akshulakov, R.; Malik, J. Egoschema: A diagnostic benchmark for very long-form video language understanding. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36.

- Wei, H.; Kong, L.; Chen, J.; Zhao, L.; Ge, Z.; Yang, J.; Sun, J.; Han, C.; Zhang, X. Vary: Scaling up the vision vocabulary for large vision-language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.06109 2023.

- Grave, É.; Bojanowski, P.; Gupta, P.; Joulin, A.; Mikolov, T. Learning Word Vectors for 157 Languages. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2018), 2018.

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. In Proceedings of the CVPR, 2022.

- Mildenhall, B.; Srinivasan, P.P.; Tancik, M.; Barron, J.T.; Ramamoorthi, R.; Ng, R. Nerf: Representing scenes as neural radiance fields for view synthesis. Communications of the ACM 2021, 65, 99–106.

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.13971 2023.

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Ding, K.; Qin, M.; Zhuang, X.; Li, X.; Chen, H. InstructProtein: Aligning Human and Protein Language via Knowledge Instruction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.03269 2023.

- Lai, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wu, W.; Bai, H.; Timofeev, A.; Du, X.; Gan, Z.; Shan, J.; Chuah, C.N.; Yang, Y.; et al. From scarcity to efficiency: Improving clip training via visual-enriched captions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.07699 2023.

- Das, A.; Kottur, S.; Gupta, K.; Singh, A.; Yadav, D.; Moura, J.M.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Visual dialog. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 326–335.

- Gao, J.; Lin, C.Y. Introduction to the special issue on statistical language modeling, 2004.

- Jiang, C.; Xu, H.; Dong, M.; Chen, J.; Ye, W.; Yan, M.; Ye, Q.; Zhang, J.; Huang, F.; Zhang, S. Hallucination Augmented Contrastive Learning for Multimodal Large Language Model. arXiv:2312.06968 2023.

- Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, L.; Guo, H.; Xiao, C. ChatGPT-powered Conversational Drug Editing Using Retrieval and Domain Feedback. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.18090 2023.

- Elazar, Y.; Bhagia, A.; Magnusson, I.; Ravichander, A.; Schwenk, D.; Suhr, A.; Walsh, P.; Groeneveld, D.; Soldaini, L.; Singh, S.; et al. What’s In My Big Data? arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.20707 2023.

- Chen, H.; Xie, W.; Afouras, T.; Nagrani, A.; Vedaldi, A.; Zisserman, A. Localizing visual sounds the hard way. In Proceedings of the CVPR, 2021.

- Xu, M.; Yoon, S.; Fuentes, A.; Park, D.S. A comprehensive survey of image augmentation techniques for deep learning. Pattern Recognition 2023, 137, 109347.

- Liu, W.; Zeng, W.; He, K.; Jiang, Y.; He, J. What Makes Good Data for Alignment? A Comprehensive Study of Automatic Data Selection in Instruction Tuning. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023.

- Stewart, G.W. On the early history of the singular value decomposition. SIAM review 1993, 35, 551–566.

- Himakunthala, V.; Ouyang, A.; Rose, D.; He, R.; Mei, A.; Lu, Y.; Sonar, C.; Saxon, M.; Wang, W.Y. Let’s Think Frame by Frame: Evaluating Video Chain of Thought with Video Infilling and Prediction. arXiv:2305.13903 2023.

- Ben Abacha, A.; Demner-Fushman, D. A question-entailment approach to question answering. BMC bioinformatics 2019, 20, 1–23.

- Jordon, J.; Szpruch, L.; Houssiau, F.; Bottarelli, M.; Cherubin, G.; Maple, C.; Cohen, S.N.; Weller, A. Synthetic Data–what, why and how? arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.03257 2022.

- Anonymous. NL2ProGPT: Taming Large Language Model for Conversational Protein Design, 2024.

- Mallya, A.; Wang, T.C.; Sapra, K.; Liu, M.Y. World-consistent video-to-video synthesis. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, Proceedings, Part VIII 16. Springer, 2020, pp. 359–378.

- Young, P.; Lai, A.; Hodosh, M.; Hockenmaier, J. From image descriptions to visual denotations: New similarity metrics for semantic inference over event descriptions. TACL 2014.

- Lei, J.; Berg, T.L.; Bansal, M. Detecting moments and highlights in videos via natural language queries. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 11846–11858.

- Lei, J.; Yu, L.; Berg, T.L.; Bansal, M. Tvr: A large-scale dataset for video-subtitle moment retrieval. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, Proceedings, Part XXI 16. Springer, 2020, pp. 447–463.

- Pham, V.T.; Le, T.L.; Tran, T.H.; Nguyen, T.P. Hand detection and segmentation using multimodal information from Kinect. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Multimedia Analysis and Pattern Recognition (MAPR). IEEE, 2020, pp. 1–6.

- Hernandez, D.; Brown, T.; Conerly, T.; DasSarma, N.; Drain, D.; El-Showk, S.; Elhage, N.; Hatfield-Dodds, Z.; Henighan, T.; Hume, T.; et al. Scaling laws and interpretability of learning from repeated data. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.10487 2022.

- Abbas, A.K.M.; Tirumala, K.; Simig, D.; Ganguli, S.; Morcos, A.S. SemDeDup: Data-efficient learning at web-scale through semantic deduplication. In Proceedings of the ICLR 2023 Workshop on Mathematical and Empirical Understanding of Foundation Models, 2023.

- Yin, S.; Fu, C.; Zhao, S.; Li, K.; Sun, X.; Xu, T.; Chen, E. A survey on multimodal large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.13549 2023.

- Mnih, V.; Heess, N.; Graves, A.; et al. Recurrent models of visual attention. Advances in neural information processing systems 2014, 27.

- Kazemzadeh, S.; Ordonez, V.; Matten, M.; Berg, T. Referitgame: Referring to objects in photographs of natural scenes. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2014 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing (EMNLP), 2014, pp. 787–798.

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, A.; Li, M.; Zhao, H.; Karypis, G.; Smola, A. Multimodal chain-of-thought reasoning in language models. arXiv:2302.00923 2023.

- Ge, J.; Luo, H.; Qian, S.; Gan, Y.; Fu, J.; Zhan, S. Chain of Thought Prompt Tuning in Vision Language Models. arXiv:2304.07919 2023.

- Chu, X.; Qiao, L.; Lin, X.; Xu, S.; Yang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wei, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, B.; Wei, X.; et al. MobileVLM: A Fast, Reproducible and Strong Vision Language Assistant for Mobile Devices. arXiv:2312.16886 2023.

- Bran, A.M.; Schwaller, P. Transformers and Large Language Models for Chemistry and Drug Discovery. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.06083 2023.

- Ono, K.; Morita, A. Evaluating large language models: Chatgpt-4, mistral 8x7b, and google gemini benchmarked against mmlu. Authorea Preprints 2024.

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2021, pp. 8748–8763.

- Sharma, P.; Ding, N.; Goodman, S.; Soricut, R. Conceptual captions: A cleaned, hypernymed, image alt-text dataset for automatic image captioning. In Proceedings of the ACL, 2018.

- Hu, W.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Chen, Z.; Tu, Z. Bliva: A simple multimodal llm for better handling of text-rich visual questions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2024, Vol. 38, pp. 2256–2264.

- Han, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, N.; Gu, Y.; Liu, X.; Huo, Y.; Qiu, J.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, L.; et al. Pre-trained models: Past, present and future. AI Open 2021, 2, 225–250.

- Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Fan, W.; Wei, X.Y.; Liu, H.; Tang, J.; Li, Q. Empowering Molecule Discovery for Molecule-Caption Translation with Large Language Models: A ChatGPT Perspective. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.06615 2023.

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Lee, Y.J. Improved baselines with visual instruction tuning. arXiv:2310.03744 2023.

- Wang, W.; Lv, Q.; Yu, W.; Hong, W.; Qi, J.; Wang, Y.; Ji, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Song, X.; et al. CogVLM: Visual Expert for Pretrained Language Models, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CV/2311.03079].

- Xu, Z.; Feng, C.; Shao, R.; Ashby, T.; Shen, Y.; Jin, D.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, Q.; Huang, L. Vision-Flan: Scaling Human-Labeled Tasks in Visual Instruction Tuning. arXiv:2402.11690 2024.

- Moon, S.; Madotto, A.; Lin, Z.; Nagarajan, T.; Smith, M.; Jain, S.; Yeh, C.F.; Murugesan, P.; Heidari, P.; Liu, Y.; et al. Anymal: An efficient and scalable any-modality augmented language model. arXiv:2309.16058 2023.

- Hendrycks, D.; Burns, C.; Kadavath, S.; Arora, A.; Basart, S.; Tang, E.; Song, D.; Steinhardt, J. Measuring mathematical problem solving with the math dataset. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.03874 2021.

- Zhao, H.; Liu, S.; Ma, C.; Xu, H.; Fu, J.; Deng, Z.H.; Kong, L.; Liu, Q. GIMLET: A Unified Graph-Text Model for Instruction-Based Molecule Zero-Shot Learning. bioRxiv 2023, pp. 2023–05.

- Li, K.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Chen, G.; Luo, P.; et al. Mvbench: A comprehensive multi-modal video understanding benchmark. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.17005 2023.

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv:2302.13971 2023.

- Chen, C.; Qin, R.; Luo, F.; Mi, X.; Li, P.; Sun, M.; Liu, Y. Position-enhanced visual instruction tuning for multimodal large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.13437 2023.

- Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Nie, W.; Eaton, J.; Rees, B.; Gu, Q. MoleculeGPT: Instruction Following Large Language Models for Molecular Property Prediction. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2023 Workshop on New Frontiers of AI for Drug Discovery and Development, 2023.

- Bran, A.M.; Cox, S.; White, A.D.; Schwaller, P. ChemCrow: Augmenting large-language models with chemistry tools. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.05376 2023.

- Singer, P.; Flöck, F.; Meinhart, C.; Zeitfogel, E.; Strohmaier, M. Evolution of reddit: from the front page of the internet to a self-referential community? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 23rd international conference on world wide web, 2014, pp. 517–522.

- Lu, Y.; Bartolo, M.; Moore, A.; Riedel, S.; Stenetorp, P. Fantastically ordered prompts and where to find them: Overcoming few-shot prompt order sensitivity. arXiv:2104.08786 2021.

- Zhang, W.; Cai, M.; Zhang, T.; Zhuang, Y.; Mao, X. Earthgpt: A universal multi-modal large language model for multi-sensor image comprehension in remote sensing domain. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.16822 2024.

- Huang, J.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, K.; Qiu, H.; Lu, S. Visual Instruction Tuning towards General-Purpose Multimodal Model: A Survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.16602 2023.

- Sun, Q.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, F.; Yu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Rao, Y.; Liu, J.; Huang, T.; Wang, X. Generative multimodal models are in-context learners. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 14398–14409.

- Chen, Y.; Sikka, K.; Cogswell, M.; Ji, H.; Divakaran, A. Dress: Instructing large vision-language models to align and interact with humans via natural language feedback. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.10081 2023.

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Fan, S.; Yang, K.; Wu, Y.; Qiao, M.; Nie, Z. Biomedgpt: Open multimodal generative pre-trained transformer for biomedicine. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.09442 2023.

- Askell, A.; Bai, Y.; Chen, A.; Drain, D.; Ganguli, D.; Henighan, T.; Jones, A.; Joseph, N.; Mann, B.; DasSarma, N.; et al. A general language assistant as a laboratory for alignment. arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.00861 2021.

- Gong, T.; Lyu, C.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, M.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, K.; Zhang, W.; Luo, P.; Chen, K. Multimodal-gpt: A vision and language model for dialogue with humans. arXiv:2305.04790 2023.

- Xu, H.; Ghosh, G.; Huang, P.Y.; Arora, P.; Aminzadeh, M.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Metze, F.; Zettlemoyer, L. VLM: Task-agnostic Video-Language Model Pre-training for Video Understanding. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, 2021, pp. 4227–4239.

- Barbieri, F.; Camacho-Collados, J.; Neves, L.; Espinosa-Anke, L. TweetEval: Unified Benchmark and Comparative Evaluation for Tweet Classification, 2020, [arXiv:cs.CL/2010.12421].

- Luo, G.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Sun, X.; Ji, R. Feast Your Eyes: Mixture-of-Resolution Adaptation for Multimodal Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.03003 2024.

- Krishna, R.; Zhu, Y.; Groth, O.; Johnson, J.; Hata, K.; Kravitz, J.; Chen, S.; Kalantidis, Y.; Li, L.J.; Shamma, D.A.; et al. Visual genome: Connecting language and vision using crowdsourced dense image annotations. IJCV 2017.

- Zhou, D.; Schärli, N.; Hou, L.; Wei, J.; Scales, N.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bousquet, O.; Le, Q.; Chi, E. Least-to-most prompting enables complex reasoning in large language models. arXiv:2205.10625 2022.

- Huang, S.; Dong, L.; Wang, W.; Hao, Y.; Singhal, S.; Ma, S.; Lv, T.; Cui, L.; Mohammed, O.K.; Liu, Q.; et al. Language is not all you need: Aligning perception with language models. arXiv:2302.14045 2023.

- Wang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Suzek, T.O.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Bryant, S.H. PubChem: a public information system for analyzing bioactivities of small molecules. Nucleic acids research 2009, 37, W623–W633.

- Liu, Z.; Li, S.; Luo, Y.; Fei, H.; Cao, Y.; Kawaguchi, K.; Wang, X.; Chua, T.S. Molca: Molecular graph-language modeling with cross-modal projector and uni-modal adapter. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.12798 2023.

- LeCun, Y. A path towards autonomous machine intelligence version 0.9. 2, 2022-06-27. Open Review 2022, 62.

- Edwards, C.; Zhai, C.; Ji, H. Text2mol: Cross-modal molecule retrieval with natural language queries. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2021, pp. 595–607.

- Xue, L.; Gao, M.; Xing, C.; Martín-Martín, R.; Wu, J.; Xiong, C.; Xu, R.; Niebles, J.C.; Savarese, S. ULIP: Learning Unified Representation of Language, Image and Point Cloud for 3D Understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.05171 2022.

- Yu, T.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, H.; He, T.; Han, Y.; Cui, G.; Hu, J.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, H.T.; Sun, M.; et al. RLHF-V: Towards Trustworthy MLLMs via Behavior Alignment from Fine-grained Correctional Human Feedback. arXiv:2312.00849 2023.

- Wang, K.; Babenko, B.; Belongie, S. End-to-end scene text recognition. In Proceedings of the 2011 International conference on computer vision. IEEE, 2011, pp. 1457–1464.

- Peebles, W.; Xie, S. Scalable diffusion models with transformers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 4195–4205.

- LeCun, Y.; Denker, J.; Solla, S. Optimal brain damage. Advances in neural information processing systems 1989, 2.

- Chen, K.; Zhang, Z.; Zeng, W.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, F.; Zhao, R. Shikra: Unleashing Multimodal LLM’s Referential Dialogue Magic. arXiv:2306.15195.

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. The Journal of Machine Learning Research 2020, 21, 5485–5551.

- Xu, P.; Shao, W.; Zhang, K.; Gao, P.; Liu, S.; Lei, M.; Meng, F.; Huang, S.; Qiao, Y.; Luo, P. LVLM-eHub: A Comprehensive Evaluation Benchmark for Large Vision-Language Models. arXiv:2306.09265 2023.

- Yu, W.; Yang, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Lin, K.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, L. Mm-vet: Evaluating large multimodal models for integrated capabilities. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.02490 2023.

- Rogers, V.; Meara, P.; Barnett-Legh, T.; Curry, C.; Davie, E. Examining the LLAMA aptitude tests. Journal of the European Second Language Association 2017, 1, 49–60.

- Lin, B.; Zhu, B.; Ye, Y.; Ning, M.; Jin, P.; Yuan, L. Video-llava: Learning united visual representation by alignment before projection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.10122 2023.

- Gu, A.; Dao, T. Mamba: Linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.00752 2023.

- Wang, B.; Li, G.; Zhou, X.; Chen, Z.; Grossman, T.; Li, Y. Screen2words: Automatic mobile UI summarization with multimodal learning. In Proceedings of the The 34th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, 2021, pp. 498–510.

- Zhang, X.; Wu, C.; Zhao, Z.; Lin, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xie, W. PMC-VQA: Visual Instruction Tuning for Medical Visual Question Answering. arXiv:2305.10415 2023.

- Chen, G.; Zheng, Y.D.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Huang, Y.; Pan, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Lu, T.; et al. Videollm: Modeling video sequence with large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.13292 2023.

- Zhou, C.; Liu, P.; Xu, P.; Iyer, S.; Sun, J.; Mao, Y.; Ma, X.; Efrat, A.; Yu, P.; Yu, L.; et al. Lima: Less is more for alignment. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36.

- Hassibi, B.; Stork, D. Second order derivatives for network pruning: Optimal brain surgeon. Advances in neural information processing systems 1992, 5.

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.; Mishkin, P.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, S.; Slama, K.; Ray, A.; et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. NeurIPS 2022.

- Wu, S.; Lu, K.; Xu, B.; Lin, J.; Su, Q.; Zhou, C. Self-evolved diverse data sampling for efficient instruction tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.08182 2023.

- Liu, F.; Wang, X.; Yao, W.; Chen, J.; Song, K.; Cho, S.; Yacoob, Y.; Yu, D. Mmc: Advancing multimodal chart understanding with large-scale instruction tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.10774 2023.

- Chen, D.; Chen, R.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, P.; Wan, Y.; Sun, L. MLLM-as-a-Judge: Assessing Multimodal LLM-as-a-Judge with Vision-Language Benchmark. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.04788 2024.

- Schaeffer, R.; Miranda, B.; Koyejo, S. Are emergent abilities of large language models a mirage? Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36.

- Kaplan, J.; McCandlish, S.; Henighan, T.; Brown, T.B.; Chess, B.; Child, R.; Gray, S.; Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Amodei, D. Scaling laws for neural language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.08361 2020.

- Zheng, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Tang, R.; Gao, S.; Zhou, Z. Structured3D: A Large Photo-realistic Dataset for Structured 3D Modeling. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of The European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2020.

- Jiang, J.; Shu, Y.; Wang, J.; Long, M. Transferability in deep learning: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2201.05867 2022.

| Application Domain | Key LVLM Capabilities | Primary Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Multimodal Conversational Interfaces | Visually grounded dialogue, context-aware responses, intent inference | Latency, hallucination, user trust, evaluation of interaction quality |

| Intelligent User Assistance | Visual referencing, explanation generation, workflow guidance | Transparency, bias in explanations, integration with legacy systems |

| Creative and Collaborative Tools | Joint reasoning over sketches and text, iterative co-creation | Control, authorship, intellectual property, usability |

| Language-Guided Manipulation | Object grounding, spatial reasoning, task generalization | Safety, perception errors, sim-to-real transfer |

| Navigation and Exploration | Landmark-based reasoning, instruction following, environment generalization | Temporal consistency, localization errors, real-time constraints |

| Human–Robot Interaction | Multimodal communication, intent explanation, adaptive behavior | Social appropriateness, trust calibration, ethical deployment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).