Submitted:

10 November 2024

Posted:

11 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

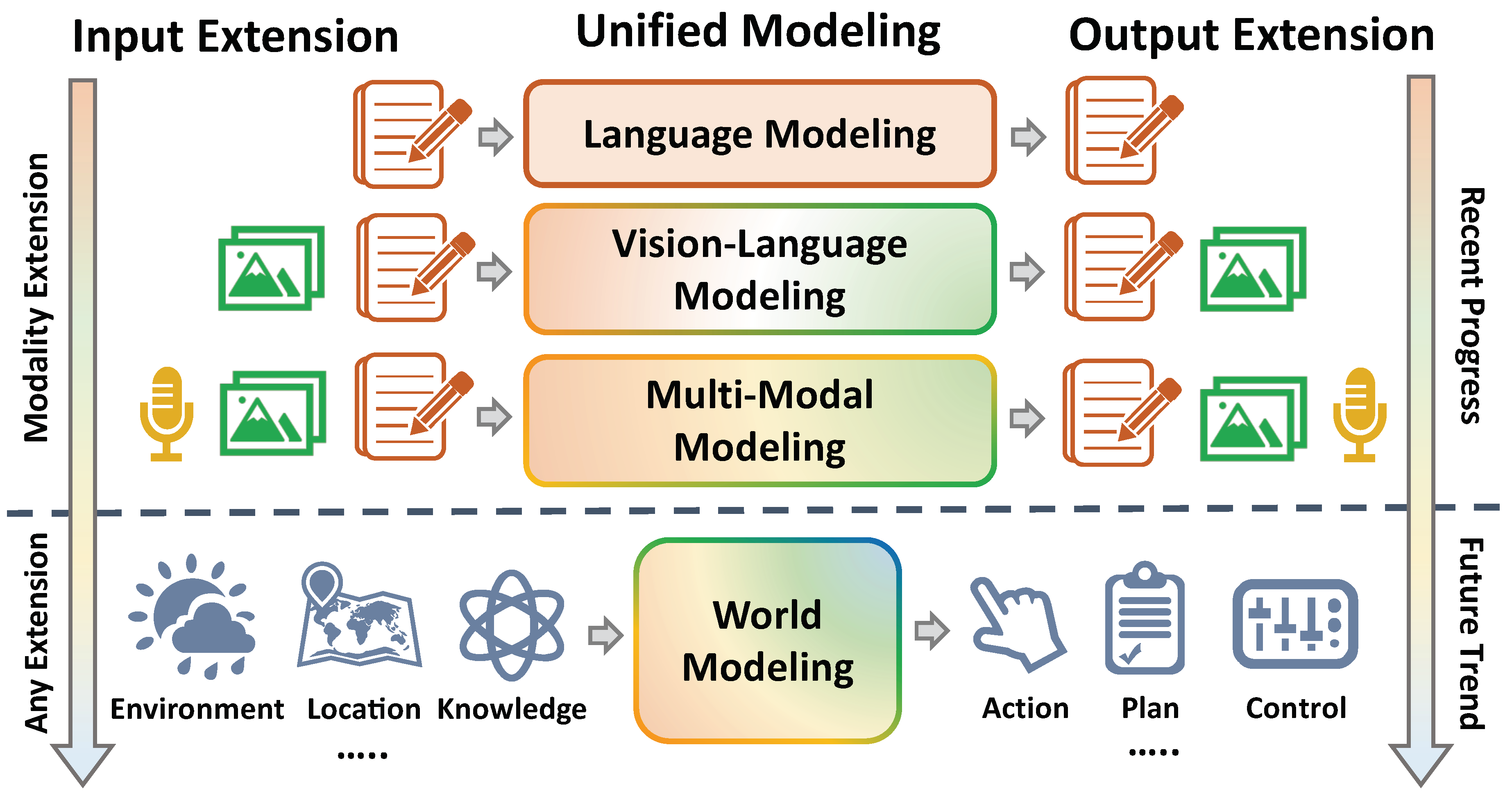

1. Introduction

- Going beyond specific scenarios and model framework, we review the current LMMs from a general perspective of input-output space extension. We hope that such a broad and comprehensive survey can provide an intuitive overview to related researchers and inspire future work.

- Based on the structure of input-output spaces, we systematically review the existing models, including mainstream models based on discrete-continuous hybrid spaces and models with unified multi-modal discrete representations. Additionally, we introduce how to align the constructed multi-modal representations and conduct evaluations according to the extended input and output.

- We elaborate on how to extend LMMs to embodied scenarios to highlight the extensibility of LMMs from the input-output extension perspective. To our knowledge, this is the first article to summarize embodied LMMs.

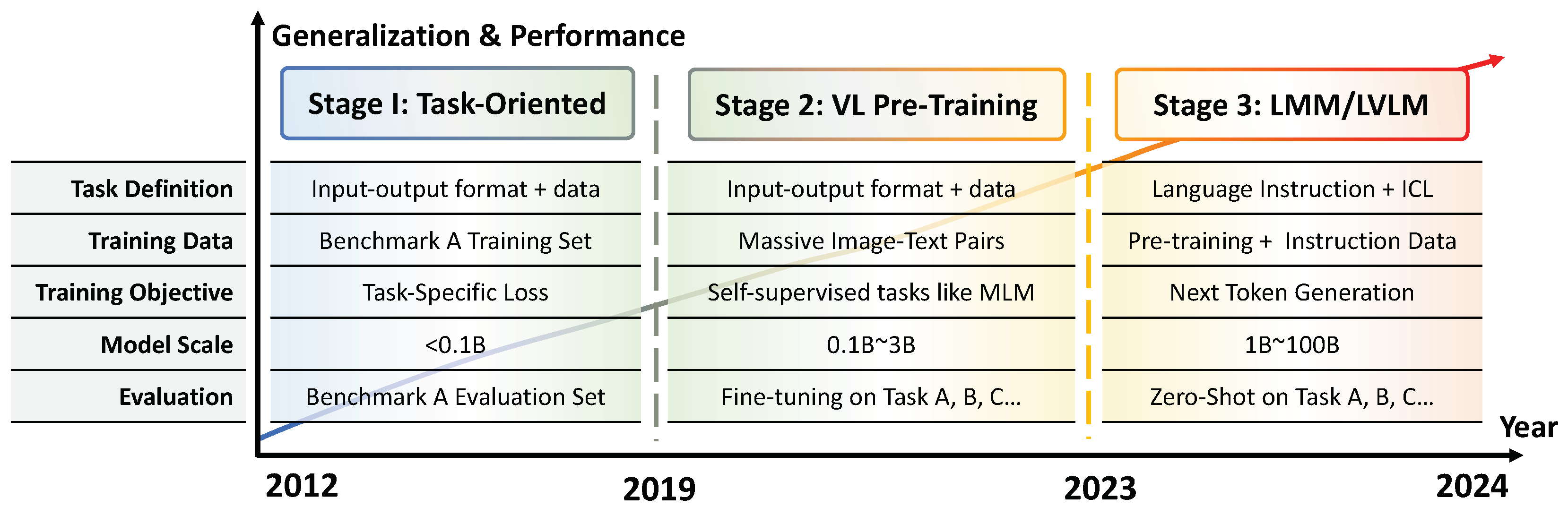

2. Preliminary

- Task-Oriented Paradigm

- Vision-Language Pre-training (VLP)

- Large Multi-Modal Models (LMMs)

3. Input-Output Space Extension

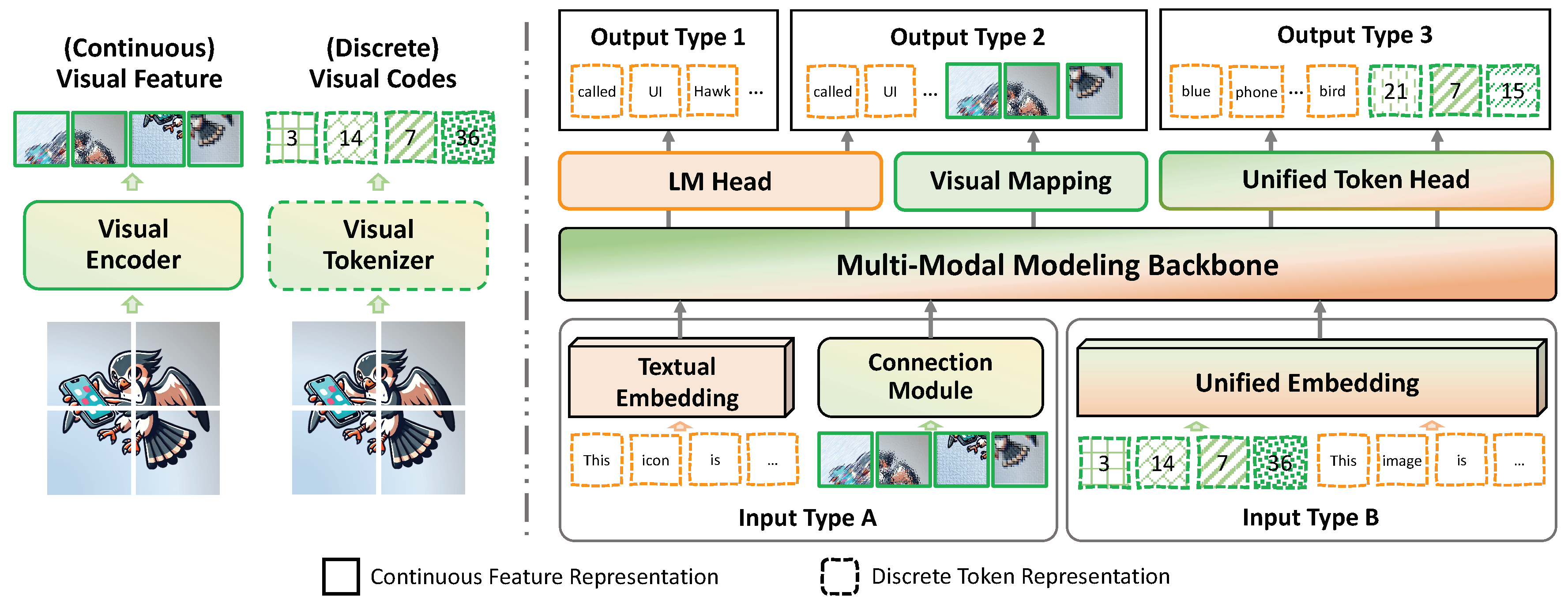

3.1. Encode Multi-Modal Input Representation

3.1.1. Textual Representation

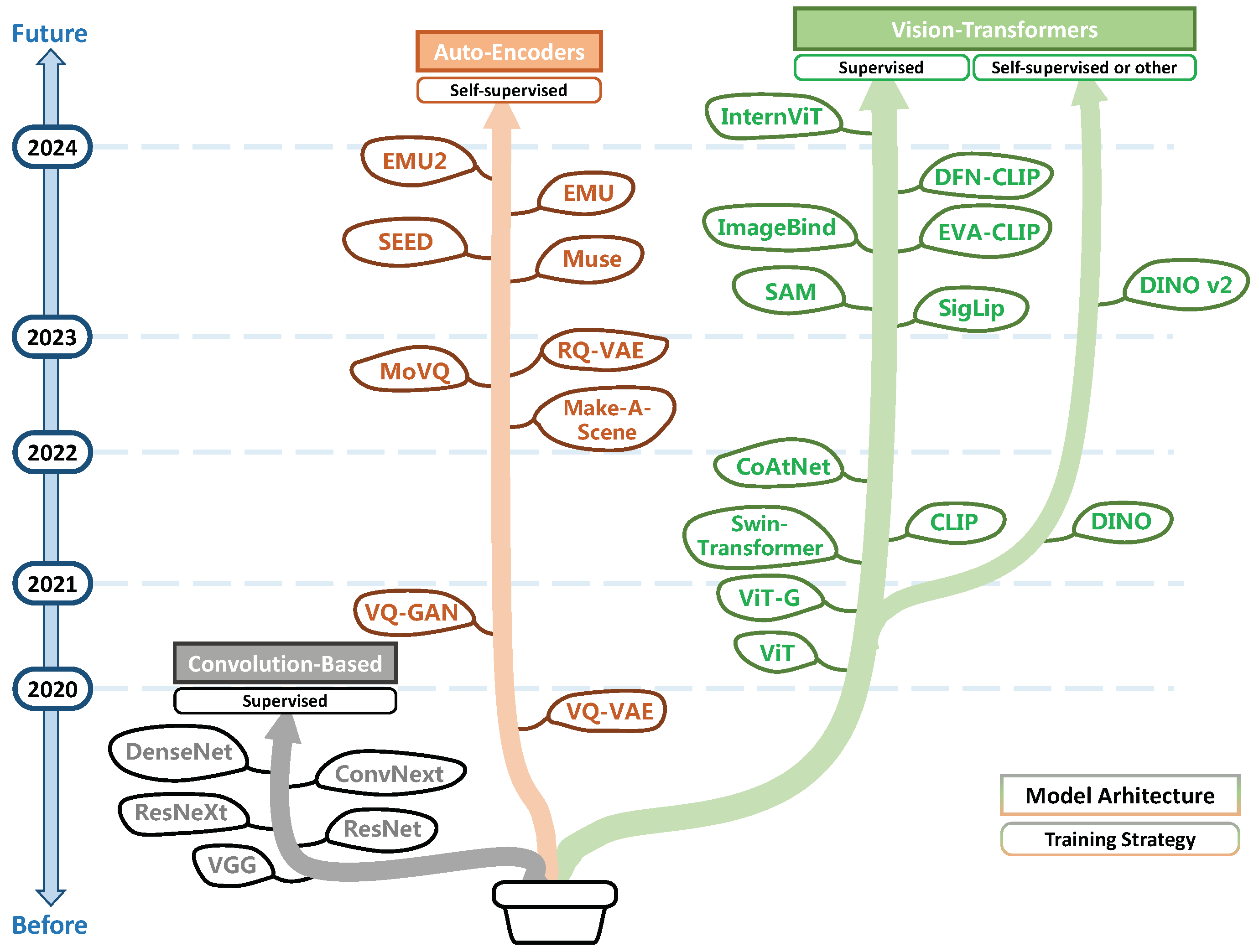

3.1.2. Visual Representation

- Encoder Architecture

- Encoder Training

- Visual Representation Enhancement

- Multi-Image Input

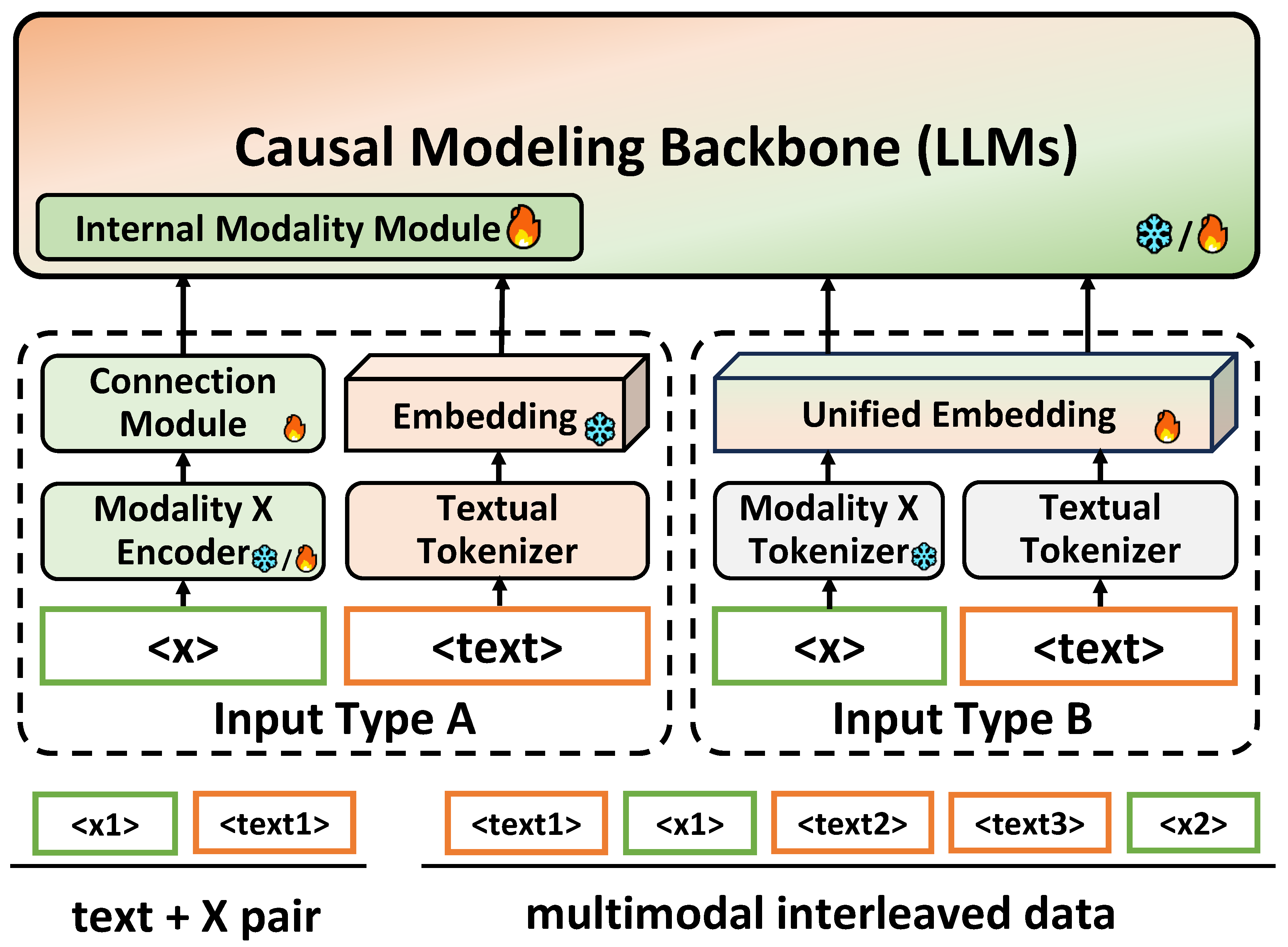

3.1.3. Constructing Multi-Modal Input Space

- Type A: Hybrid Input Space

- Type B: Unified Discrete Input Space

3.1.4. Extension to More Modalities

3.2. Decode Multi-Modal Output Representation

3.2.1. Type 1: Text-Only Output Space

3.2.2. Type 2: Hybrid Multi-Modal Output Space

3.2.3. Type 3: Unified Discrete Multi-Modal Output Space

3.2.4. Extension to More Modalities

3.3. Prevalent Input-Output Paradigms

4. Multi-Modal Alignment

4.1. Alignment Architecture

4.1.1. Multi-Modal Modeling Backbone

4.1.2. Input-level Alignment

- MLP Based

- Attention Based

- Others

4.1.3. Internal Alignment

- Cross-Attention Layer

- Adaption Prompt

- Visual Expert

- Mixture of Experts (MoE)

4.1.4. Output-level Alignment

4.2. Multi-Modal Training

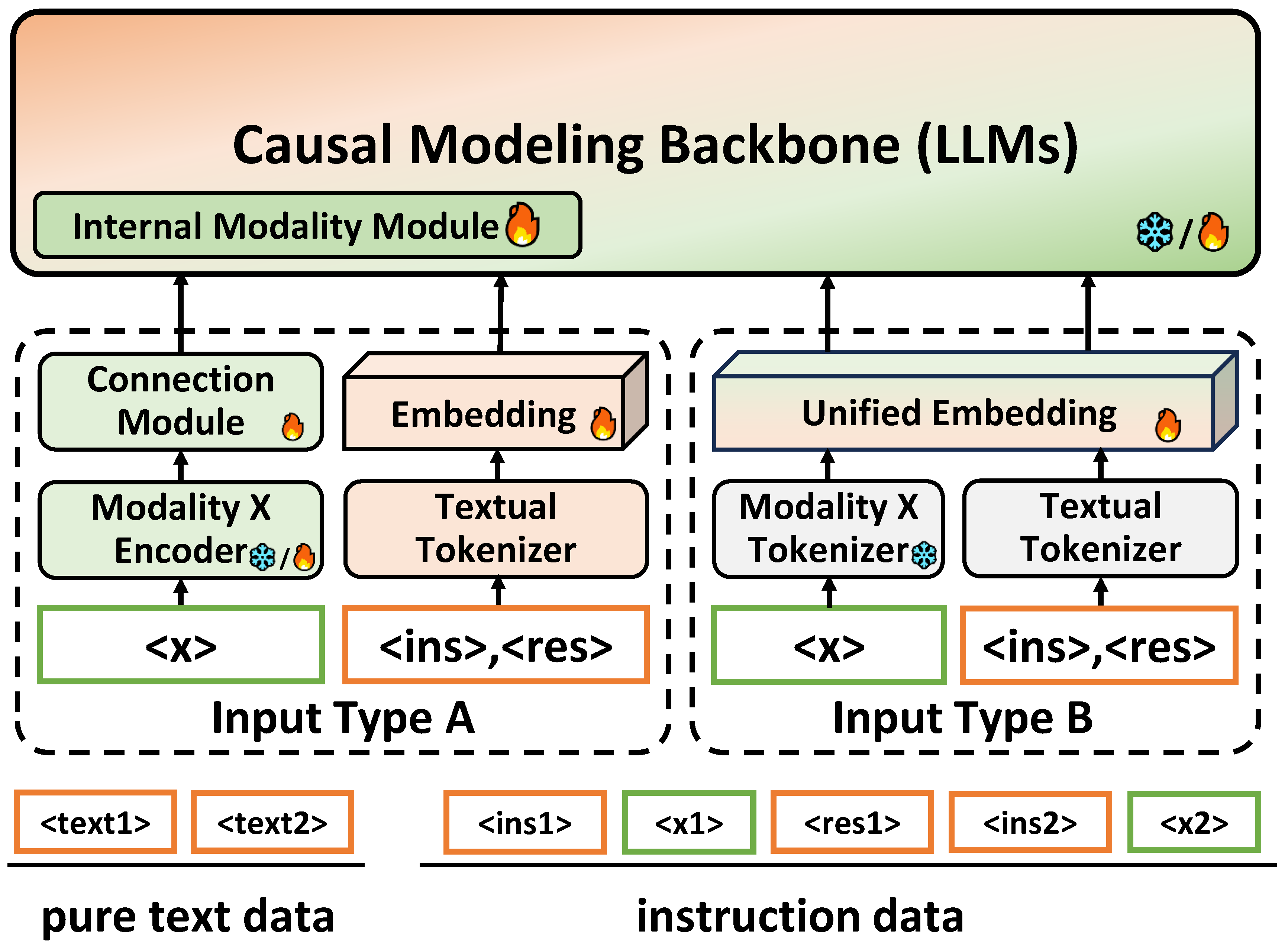

4.2.1. Training Data

- Pre-training Data

- Instruction-following Data

4.2.2. Training Stages

- Pre-training

- Instruction Fine-tuning

- Additional Alignment Stages

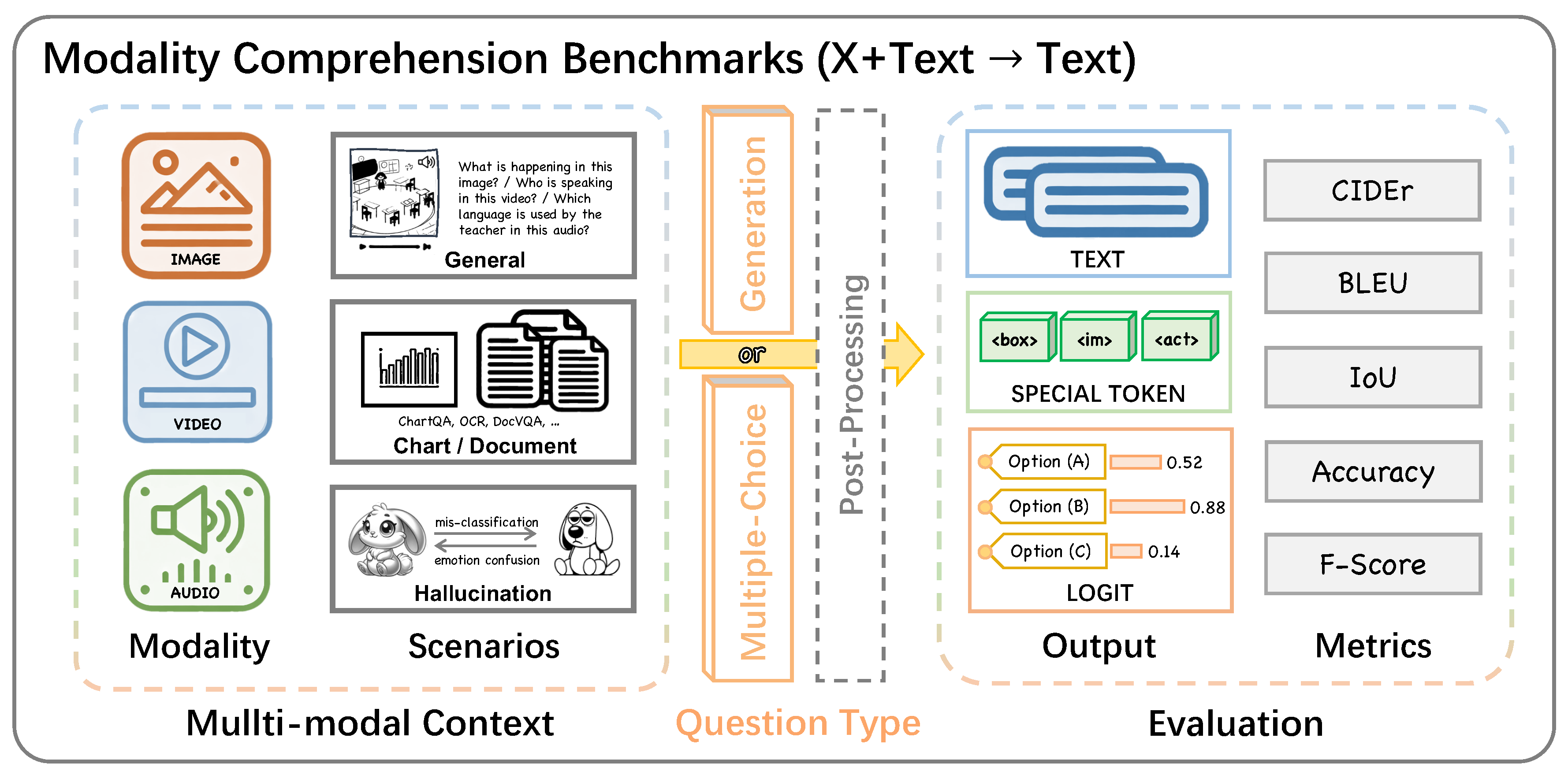

5. Evaluation and Benchmarks

5.1. Modality Comprehension Benchmarks

5.1.1. Image-to-Text

5.1.2. Video-to-Text

5.1.3. Audio-to-Text

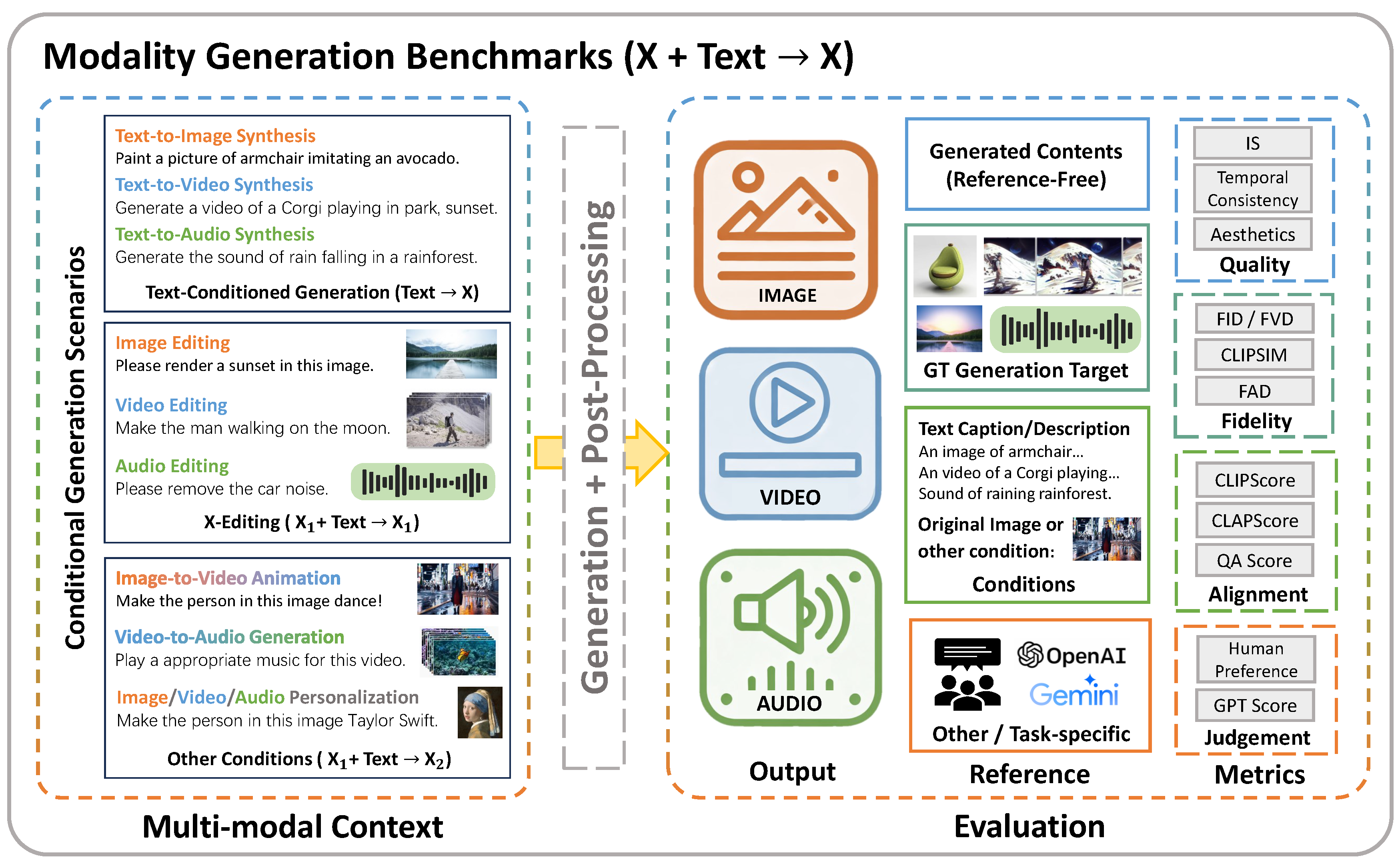

5.2. Modality Generation Benchmarks

5.2.1. Image Generation

5.2.2. Video Generation

5.2.3. Audio Generation

6. Diagnostics: Benchmarks for Hallucination Evaluation

6.1. Evaluation on Hallucination Discrimination

6.2. Evaluation on Hallucination Generation

7. Extension to Embodied Agents

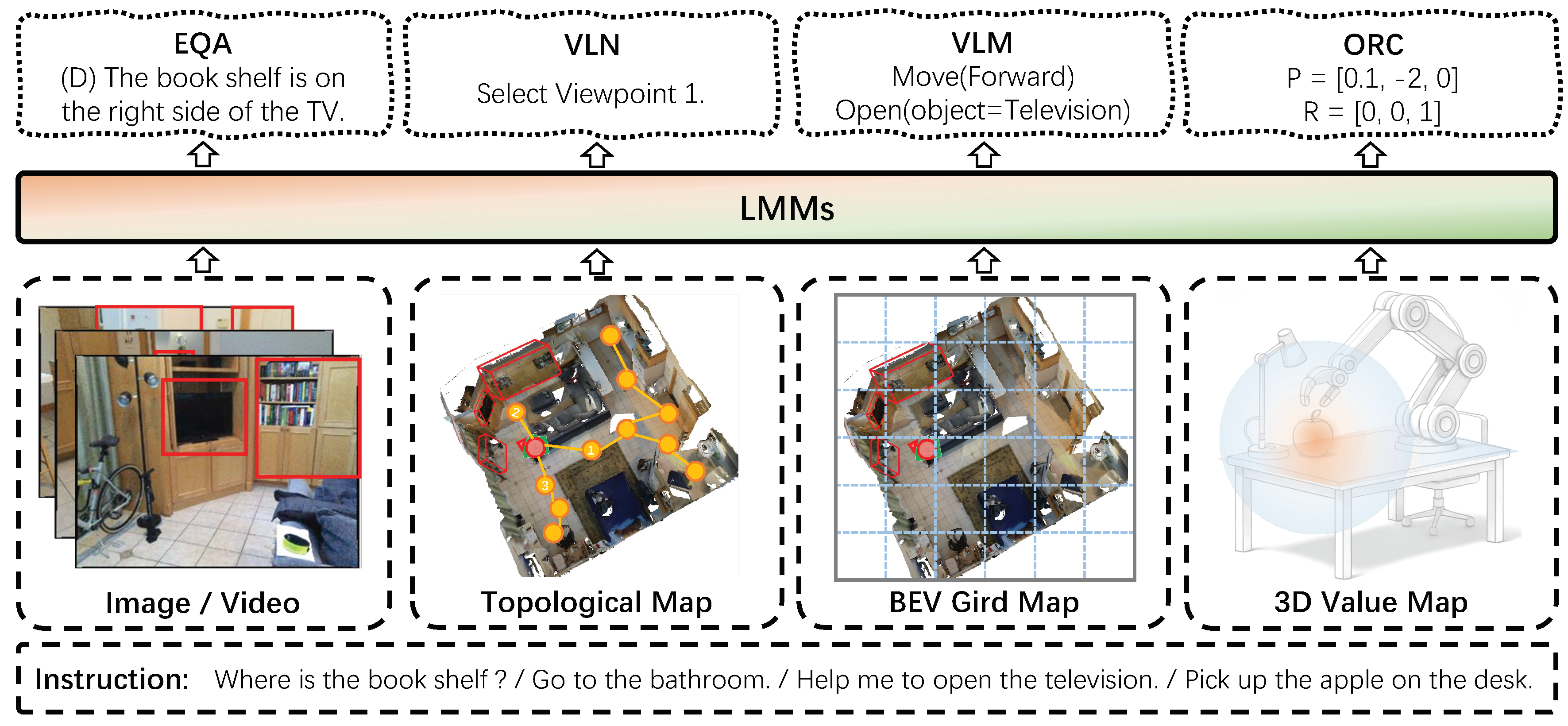

7.1. Embodied Tasks

7.2. Input Extension: Environment Representation

7.3. Output Extension: Action Representation

- Discrete Action Space

- Continuous Action Space

- Hierarchical Action Space

7.4. Multi-Modal Alignment

- Input-level Alignment

- Output-level Alignment

7.5. Evaluation

- Task-Specific Benchmarks

- Comprehensive Benchmarks

8. Discussion and Outlook

8.0.1. How to construct multi-modal input-output spaces with discretely or continuously encoded modality signal?

8.0.2. How to design model architectures and training strategies to align the constructed multi-modal space?

8.0.3. How to comprehensively evaluate LMMs based on the expanded input-output space?

8.0.4. A promising way towards world models.

9. Conclusion

References

- OpenAI. ChatGPT ( version), 2023. 3 August.

- Touvron, H.; Martin, L.; Stone, K.; Albert, P.; Almahairi, A.; Babaei, Y.; Bashlykov, N.; Batra, S.; Bhargava, P.; Bhosale, S. ; others. Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.09288 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J.; Bai, S.; Chu, Y.; Cui, Z.; Dang, K.; Deng, X.; Fan, Y.; Ge, W.; Han, Y.; Huang, F. ; others. Qwen technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.16609, arXiv:2309.16609 2023.

- AI@Meta. Llama 3 Model Card 2024.

- Li, J.; Li, D.; Savarese, S.; Hoi, S. Blip-2: Bootstrapping language-image pre-training with frozen image encoders and large language models. arXiv:2301.12597, arXiv:2301.12597 2023.

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Wu, Q.; Lee, Y.J. Visual instruction tuning. Advances in neural information processing systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J.; Bai, S.; Yang, S.; Wang, S.; Tan, S.; Wang, P.; Lin, J.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, J. Qwen-vl: A frontier large vision-language model with versatile abilities. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.12966, arXiv:2308.12966 2023.

- Ma, Z.; Yang, G.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Z.; Wang, J.; Du, Z.; Yu, F.; Chen, Q.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, S. ; others. An Embarrassingly Simple Approach for LLM with Strong ASR Capacity. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.08846, arXiv:2402.08846 2024.

- Koh, J.Y.; Fried, D.; Salakhutdinov, R.R. Generating images with multimodal language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhan, J.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y.; Qiu, X. SpeechGPT-Gen: Scaling Chain-of-Information Speech Generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.13527, arXiv:2401.13527 2024.

- Wu, S.; Fei, H.; Qu, L.; Ji, W.; Chua, T.S. Next-gpt: Any-to-any multimodal llm. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.05519, arXiv:2309.05519 2023.

- Zhan, J.; Dai, J.; Ye, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, R.; Zhang, G.; Li, L.; Yan, H.; Fu, J.; Gui, T.; Sun, T.; Jiang, Y.; Qiu, X. 2024; arXiv:cs.CL/2402.12226].

- Wu, J.; Gan, W.; Chen, Z.; Wan, S.; Philip, S.Y. Multimodal large language models: A survey. 2023 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData). IEEE, 2023, pp. 2247–2256.

- Caffagni, D.; Cocchi, F.; Barsellotti, L.; Moratelli, N.; Sarto, S.; Baraldi, L.; Cornia, M.; Cucchiara, R. The (r) evolution of multimodal large language models: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.12451, arXiv:2402.12451 2024.

- Tang, Y.; Bi, J.; Xu, S.; Song, L.; Liang, S.; Wang, T.; Zhang, D.; An, J.; Lin, J.; Zhu, R. ; others. Video understanding with large language models: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.17432, arXiv:2312.17432 2023.

- Latif, S.; Shoukat, M.; Shamshad, F.; Usama, M.; Ren, Y.; Cuayáhuitl, H.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; Togneri, R.; Cambria, E. ; others. Sparks of large audio models: A survey and outlook. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.12792, arXiv:2308.12792 2023.

- Xiao, H.; Zhou, F.; Liu, X.; Liu, T.; Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Huang, X. A comprehensive survey of large language models and multimodal large language models in medicine. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.08603, arXiv:2405.08603 2024.

- Cui, C.; Ma, Y.; Cao, X.; Ye, W.; Zhou, Y.; Liang, K.; Chen, J.; Lu, J.; Yang, Z.; Liao, K.D. ; others. A survey on multimodal large language models for autonomous driving. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 2024, pp. 958–979.

- Li, J.; Lu, W. A Survey on Benchmarks of Multimodal Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.08632, arXiv:2408.08632 2024.

- Huang, J.; Zhang, J. A Survey on Evaluation of Multimodal Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.15769, arXiv:2408.15769 2024.

- Bai, T.; Liang, H.; Wan, B.; Yang, L.; Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Cui, B.; He, C.; Yuan, B.; Zhang, W. A Survey of Multimodal Large Language Model from A Data-centric Perspective. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.16640, arXiv:2405.16640 2024.

- Team, C. Chameleon: Mixed-modal early-fusion foundation models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.09818, arXiv:2405.09818 2024.

- Goyal, Y.; Khot, T.; Summers-Stay, D.; Batra, D.; Parikh, D. Making the v in vqa matter: Elevating the role of image understanding in visual question answering. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2017, pp. 6904–6913.

- Hudson, D.A.; Manning, C.D. Gqa: A new dataset for real-world visual reasoning and compositional question answering. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2019, pp. 6700–6709.

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. ECCV. Springer, 2014, pp. 740–755.

- Young, P.; Lai, A.; Hodosh, M.; Hockenmaier, J. From image descriptions to visual denotations: New similarity metrics for semantic inference over event descriptions. TACL 2014, 2, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, H.; Desai, K.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Jain, R.; Johnson, M.; Batra, D.; Parikh, D.; Lee, S.; Anderson, P. Nocaps: Novel object captioning at scale. ICCV, 2019, pp. 8948–8957.

- Sidorov, O.; Hu, R.; Rohrbach, M.; Singh, A. Textcaps: a dataset for image captioning with reading comprehension. ECCV. Springer, 2020, pp. 742–758.

- Kazemzadeh, S.; Ordonez, V.; Matten, M.; Berg, T. Referitgame: Referring to objects in photographs of natural scenes. EMNLP, 2014, pp. 787–798.

- Johnson, J.; Hariharan, B.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Fei-Fei, L.; Lawrence Zitnick, C.; Girshick, R. Clevr: A diagnostic dataset for compositional language and elementary visual reasoning. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2017, pp. 2901–2910.

- Suhr, A.; Lewis, M.; Yeh, J.; Artzi, Y. A Corpus of Natural Language for Visual Reasoning. Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers); Barzilay, R., Kan, M.Y., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Vancouver, Canada, 2017; pp. 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.; Lai, F.; Doran, D.; Kadav, A. Visual entailment: A novel task for fine-grained image understanding. arXiv:1901.06706, arXiv:1901.06706 2019.

- Zellers, R.; Bisk, Y.; Farhadi, A.; Choi, Y. From recognition to cognition: Visual commonsense reasoning. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2019, pp. 6720–6731.

- Xu, K.; Ba, J.; Kiros, R.; Cho, K.; Courville, A.; Salakhudinov, R.; Zemel, R.; Bengio, Y. Show, Attend and Tell: Neural Image Caption Generation with Visual Attention. Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning; Bach, F., Blei, D., Eds.; PMLR: Lille, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Faghri, F.; Fleet, D.J.; Kiros, J.R.; Fidler, S. Vse++: Improving visual-semantic embeddings with hard negatives. arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.05612, arXiv:1707.05612 2017.

- Anderson, P.; He, X.; Buehler, C.; Teney, D.; Johnson, M.; Gould, S.; Zhang, L. Bottom-Up and Top-Down Attention for Image Captioning and Visual Question Answering. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2018.

- Li, Z.; Wei, Z.; Fan, Z.; Shan, H.; Huang, X. An Unsupervised Sampling Approach for Image-Sentence Matching Using Document-level Structural Information. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2021, 35, 13324–13332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wei, Z.; Li, P.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, X. Storytelling from an Image Stream Using Scene Graphs. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2020, 34, 9185–9192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraja, V.K.; Morariu, V.I.; Davis, L.S. Modeling context between objects for referring expression understanding. Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, –14, 2016, Proceedings, Part IV 14. Springer, 2016, pp. 792–807. 11 October.

- Yue, S.; Tu, Y.; Li, L.; Yang, Y.; Gao, S.; Yu, Z. I3n: Intra-and inter-representation interaction network for change captioning. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2023, 25, 8828–8841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. 2019; arXiv:cs.CL/1810.04805].

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.u.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All you Need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Guyon, I.; Luxburg, U.V.; Bengio, S.; Wallach, H.; Fergus, R.; Vishwanathan, S.; Garnett, R., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2017, Vol. 30.

- Chen, Y.C.; Li, L.; Yu, L.; El Kholy, A.; Ahmed, F.; Gan, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, J. Uniter: Universal image-text representation learning. ECCV. Springer, 2020, pp. 104–120.

- Su, W.; Zhu, X.; Cao, Y.; Li, B.; Lu, L.; Wei, F.; Dai, J. 2020; arXiv:cs.CV/1908.08530].

- Li, J.; Selvaraju, R.; Gotmare, A.; Joty, S.; Xiong, C.; Hoi, S.C.H. Align before Fuse: Vision and Language Representation Learning with Momentum Distillation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Ranzato, M.; Beygelzimer, A.; Dauphin, Y.; Liang, P.; Vaughan, J.W., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2021, Vol. 34, pp. 9694–9705.

- Li, Z.; Fan, Z.; Tou, H.; Chen, J.; Wei, Z.; Huang, X. Mvptr: Multi-level semantic alignment for vision-language pre-training via multi-stage learning. Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, 2022, pp. 4395–4405.

- Li, X.; Yin, X.; Li, C.; Zhang, P.; Hu, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; Hu, H.; Dong, L.; Wei, F.; Choi, Y.; Gao, J. Oscar: Object-Semantics Aligned Pre-training for Vision-Language Tasks. Computer Vision – ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, Proceedings, Part XXX; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2020; pp. 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, D.; Xiong, C.; Hoi, S. Blip: Bootstrapping language-image pre-training for unified vision-language understanding and generation. ICML. PMLR, 2022, pp. 12888–12900.

- Yu, J.; Wang, Z.; Vasudevan, V.; Yeung, L.; Seyedhosseini, M.; Wu, Y. 2022; arXiv:cs.CV/2205.01917].

- Wang, Z.; Yu, J.; Yu, A.W.; Dai, Z.; Tsvetkov, Y.; Cao, Y. 2022; arXiv:cs.CV/2108.10904].

- Li, Z.; Fan, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, X.; Wei, Z. Unifying Cross-Lingual and Cross-Modal Modeling Towards Weakly Supervised Multilingual Vision-Language Pre-training. Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); Rogers, A., Boyd-Graber, J., Okazaki, N., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Toronto, Canada, 2023; pp. 5939–5958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Bosma, M.; Zhao, V.Y.; Guu, K.; Yu, A.W.; Lester, B.; Du, N.; Dai, A.M.; Le, Q.V. Finetuned language models are zero-shot learners. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.01652, arXiv:2109.01652 2021.

- OpenAI. GPT-4 Technical Report. arXiv:2303.08774, arXiv:2303.08774 2023.

- Sennrich, R.; Haddow, B.; Birch, A. Neural machine translation of rare words with subword units. arXiv preprint arXiv:1508.07909, arXiv:1508.07909 2015.

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I.; others. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI blog 2019, 1, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y. Google’s Neural Machine Translation System: Bridging the Gap between human and machine translation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.08144, arXiv:1609.08144 2016.

- Kudo, T. Subword regularization: Improving neural network translation models with multiple subword candidates. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.10959, arXiv:1804.10959 2018.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 770–778.

- Liu, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, C.Y.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Darrell, T.; Xie, S. A ConvNet for the 2020s. arXiv e-prints, 2022.

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S. ; others. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929, arXiv:2010.11929 2020.

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021, pp. 10012–10022.

- Van Den Oord, A.; Vinyals, O.; others. Neural discrete representation learning. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Esser, P.; Rombach, R.; Ommer, B. Taming transformers for high-resolution image synthesis. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021, pp. 12873–12883.

- Bavishi, R.; Elsen, E.; Hawthorne, C.; Nye, M.; Odena, A.; Somani, A.; Taşırlar, S. Fuyu-8B, 2023.

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; Uszkoreit, J.; Houlsby, N. T: Image is Worth 16x16 Words, 2021; arXiv:cs.CV/2010.11929].

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J. ; others. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. ICML. PMLR, 2021, pp. 8748–8763.

- Sun, Q.; Fang, Y.; Wu, L.; Wang, X.; Cao, Y. Eva-clip: Improved training techniques for clip at scale. arXiv:2303.15389, arXiv:2303.15389 2023.

- Zhai, X.; Mustafa, B.; Kolesnikov, A.; Beyer, L. Sigmoid loss for language image pre-training. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 11975–11986.

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.Y. ; others. Segment anything. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 4015–4026.

- He, K.; Fan, H.; Wu, Y.; Xie, S.; Girshick, R. Momentum contrast for unsupervised visual representation learning. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020, pp. 9729–9738.

- Caron, M.; Touvron, H.; Misra, I.; Jégou, H.; Mairal, J.; Bojanowski, P.; Joulin, A. Emerging properties in self-supervised vision transformers. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021, pp. 9650–9660.

- Zhou, J.; Wei, C.; Wang, H.; Shen, W.; Xie, C.; Yuille, A.; Kong, T. ibot: Image bert pre-training with online tokenizer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2111.07832, arXiv:2111.07832 2021.

- Oquab, M.; Darcet, T.; Moutakanni, T.; Vo, H.; Szafraniec, M.; Khalidov, V.; Fernandez, P.; Haziza, D.; Massa, F.; El-Nouby, A. ; others. Dinov2: Learning robust visual features without supervision. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.07193, arXiv:2304.07193 2023.

- Ge, Y.; Ge, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, X.; Shan, Y. 2023; arXiv:cs.CV/2307.08041].

- Sun, Q.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, F.; Yu, Q.; Luo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Rao, Y.; Liu, J.; Huang, T.; Wang, X. 2024; arXiv:cs.CV/2312.13286].

- Zhu, D.; Chen, J.; Shen, X.; Li, X.; Elhoseiny, M. Minigpt-4: Enhancing vision-language understanding with advanced large language models. arXiv:2304.10592, arXiv:2304.10592 2023.

- Yuan, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, J.; Tang, D.; Luo, X.; Qin, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, J. Osprey: Pixel understanding with visual instruction tuning. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 28202–28211.

- Ge, C.; Cheng, S.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, J.; Gao, Y.; Song, J.; Song, S.; Huang, G.; Zheng, B. ConvLLaVA: Hierarchical Backbones as Visual Encoder for Large Multimodal Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.15738, arXiv:2405.15738 2024.

- Ye, J.; Hu, A.; Xu, H.; Ye, Q.; Yan, M.; Xu, G.; Li, C.; Tian, J.; Qian, Q.; Zhang, J. ; others. Ureader: Universal ocr-free visually-situated language understanding with multimodal large language model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.05126, arXiv:2310.05126 2023.

- Li, Z.; Yang, B.; Liu, Q.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yang, J.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Bai, X. Monkey: Image resolution and text label are important things for large multi-modal models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.06607, arXiv:2311.06607 2023.

- Gao, P.; Zhang, R.; Liu, C.; Qiu, L.; Huang, S.; Lin, W.; Zhao, S.; Geng, S.; Lin, Z.; Jin, P. ; others. SPHINX-X: Scaling Data and Parameters for a Family of Multi-modal Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.05935, arXiv:2402.05935 2024.

- Xu, R.; Yao, Y.; Guo, Z.; Cui, J.; Ni, Z.; Ge, C.; Chua, T.S.; Liu, Z.; Sun, M.; Huang, G. LLaVA-UHD: an LMM Perceiving Any Aspect Ratio and High-Resolution Images. ArXiv, 2403. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, S.; Lee, Y.J. Llava-next: Improved reasoning, ocr, and world knowledge, 2024.

- Lu, H.; Liu, W.; Zhang, B.; Wang, B.; Dong, K.; Liu, B.; Sun, J.; Ren, T.; Li, Z.; Sun, Y. ; others. Deepseek-vl: Towards real-world vision-language understanding. arXiv:2403.05525, arXiv:2403.05525 2024.

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, W.; Ding, P.; Huang, S.; Wang, D. Cobra: Extending Mamba to Multi-Modal Large Language Model for Efficient Inference 2024.

- Hong, W.; Wang, W.; Lv, Q.; Xu, J.; Yu, W.; Ji, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Dong, Y.; Ding, M. ; others. Cogagent: A visual language model for gui agents. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.08914, arXiv:2312.08914 2023.

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhong, Z.; Chen, Y.; Chu, R.; Liu, S.; Jia, J. Mini-gemini: Mining the potential of multi-modality vision language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.18814, arXiv:2403.18814 2024.

- Tong, S.; Brown, E.; Wu, P.; Woo, S.; Middepogu, M.; Akula, S.C.; Yang, J.; Yang, S.; Iyer, A.; Pan, X. ; others. Cambrian-1: A fully open, vision-centric exploration of multimodal llms. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.16860, arXiv:2406.16860 2024.

- Fan, X.; Ji, T.; Jiang, C.; Li, S.; Jin, S.; Song, S.; Wang, J.; Hong, B.; Chen, L.; Zheng, G. ; others. MouSi: Poly-Visual-Expert Vision-Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.17221, arXiv:2401.17221 2024.

- Luo, R.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, M.; Dong, J.; Qiu, M.; Lu, P.; Wang, T.; Wei, Z. Valley: Video assistant with large language model enhanced ability. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.07207, arXiv:2306.07207 2023.

- Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Bing, L. Video-llama: An instruction-tuned audio-visual language model for video understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.02858, arXiv:2306.02858 2023.

- Li, B.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Liu, Z. 2023; arXiv:cs.CV/2305.03726].

- Yu, Y.Q.; Liao, M.; Zhang, J.; Wu, J. TextHawk2: A Large Vision-Language Model Excels in Bilingual OCR and Grounding with 16x Fewer Tokens. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.05261, arXiv:2410.05261 2024.

- Bertasius, G.; Wang, H.; Torresani, L. Is space-time attention all you need for video understanding? ICML, 2021, Vol. 2, p. 4.

- Liu, Z.; Ning, J.; Cao, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Hu, H. Video Swin Transformer. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2022, pp. 3202–3211.

- Li, K.; He, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Luo, P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Qiao, Y. Videochat: Chat-centric video understanding. arXiv:2305.06355, arXiv:2305.06355 2023.

- Xu, H.; Ye, Q.; Wu, X.; Yan, M.; Miao, Y.; Ye, J.; Xu, G.; Hu, A.; Shi, Y.; Xu, G. ; others. Youku-mplug: A 10 million large-scale chinese video-language dataset for pre-training and benchmarks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.04362, arXiv:2306.04362 2023.

- Hsu, W.N.; Bolte, B.; Tsai, Y.H.H.; Lakhotia, K.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Mohamed, A. Hubert: Self-supervised speech representation learning by masked prediction of hidden units. IEEE/ACM transactions on audio, speech, and language processing 2021, 29, 3451–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizalde, B.; Deshmukh, S.; Al Ismail, M.; Wang, H. Clap learning audio concepts from natural language supervision. ICASSP 2023-2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–5.

- Girdhar, R.; El-Nouby, A.; Liu, Z.; Singh, M.; Alwala, K.V.; Joulin, A.; Misra, I. Imagebind: One embedding space to bind them all. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2023, pp. 15180–15190.

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, D.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y.; Qiu, X. Speechtokenizer: Unified speech tokenizer for speech large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.16692, arXiv:2308.16692 2023.

- Han, J.; Zhang, R.; Shao, W.; Gao, P.; Xu, P.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, K.; Liu, C.; Wen, S.; Guo, Z. ; others. ImageBind-LLM: Multi-modality Instruction Tuning. arXiv:2309.03905, arXiv:2309.03905 2023.

- Tang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Khademi, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, C.; Bansal, M. 2023; arXiv:cs.CV/2311.18775].

- Lu, J.; Clark, C.; Lee, S.; Zhang, Z.; Khosla, S.; Marten, R.; Hoiem, D.; Kembhavi, A. S: 2, 2023; arXiv:cs.CV/2312.17172].

- Wu, C.; Yin, S.; Qi, W.; Wang, X.; Tang, Z.; Duan, N. Visual chatgpt: Talking, drawing and editing with visual foundation models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.04671, arXiv:2303.04671 2023.

- Zhang, P.; Wang, X.; Cao, Y.; Xu, C.; Ouyang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Ding, S.; Zhang, S.; Duan, H.; Yan, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Li, J.; Chen, K.; He, C.; Zhang, X.; Qiao, Y.; Lin, D.; Wang, J. InternLM-XComposer: A Vision-Language Large Model for Advanced Text-image Comprehension and Composition. ArXiv, 2309. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.; Zhang, P.; Zang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, B.; Ouyang, L.; Wei, X.; Zhang, S.; Duan, H.; Cao, M. ; others. InternLM-XComposer2: Mastering free-form text-image composition and comprehension in vision-language large model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.16420, arXiv:2401.16420 2024.

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-Resolution Image Synthesis With Latent Diffusion Models. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2022, pp. 10684–10695.

- Dong, R.; Han, C.; Peng, Y.; Qi, Z.; Ge, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhao, L.; Sun, J.; Zhou, H.; Wei, H.; Kong, X.; Zhang, X.; Ma, K.; Yi, L. 2024; arXiv:cs.CV/2309.11499].

- Zheng, K.; He, X.; Wang, X.E. 2024; arXiv:cs.CV/2310.02239].

- Sun, Q.; Yu, Q.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, H.; Liu, J.; Huang, T.; Wang, X. 2024; arXiv:cs.CV/2307.05222].

- Ge, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zeng, Z.; Ge, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Shan, Y. Making llama see and draw with seed tokenizer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.01218, arXiv:2310.01218 2023.

- Dai, W.; Li, J.; Li, D.; Tiong, A.M.H.; Zhao, J.; Wang, W.; Li, B.; Fung, P.; Hoi, S. 2023; arXiv:cs.CV/2305.06500].

- Chen, Z.; Wu, J.; Wang, W.; Su, W.; Chen, G.; Xing, S.; Muyan, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, X.; Lu, L. ; others. Internvl: Scaling up vision foundation models and aligning for generic visual-linguistic tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.14238, arXiv:2312.14238 2023.

- Alayrac, J.B.; Donahue, J.; Luc, P.; Miech, A.; Barr, I.; Hasson, Y.; Lenc, K.; Mensch, A.; Millican, K.; Reynolds, M.; others. Flamingo: a visual language model for few-shot learning. NIPS 2022, 35, 23716–23736. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Han, J.; Zhou, A.; Hu, X.; Yan, S.; Lu, P.; Li, H.; Gao, P.; Qiao, Y. Llama-adapter: Efficient fine-tuning of language models with zero-init attention. arXiv:2303.16199, arXiv:2303.16199 2023.

- Zhu, D.; Chen, J.; Shen, X.; Li, X.; Elhoseiny, M. Minigpt-4: Enhancing vision-language understanding with advanced large language models. arXiv:2304.10592, arXiv:2304.10592 2023.

- Ye, Q.; Xu, H.; Xu, G.; Ye, J.; Yan, M.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Hu, A.; Shi, P.; Shi, Y. ; others. mplug-owl: Modularization empowers large language models with multimodality. arXiv:2304.14178, arXiv:2304.14178 2023.

- Gao, P.; Han, J.; Zhang, R.; Lin, Z.; Geng, S.; Zhou, A.; Zhang, W.; Lu, P.; He, C.; Yue, X. ; others. Llama-adapter v2: Parameter-efficient visual instruction model. arXiv:2304.15010, arXiv:2304.15010 2023.

- Luo, G.; Zhou, Y.; Ren, T.; Chen, S.; Sun, X.; Ji, R. Cheap and Quick: Efficient Vision-Language Instruction Tuning for Large Language Models. arXiv:2305.15023, arXiv:2305.15023 2023.

- Gong, T.; Lyu, C.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, M.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, K.; Zhang, W.; Luo, P.; Chen, K. Multimodal-gpt: A vision and language model for dialogue with humans. arXiv:2305.04790, arXiv:2305.04790 2023.

- Chen, K.; Zhang, Z.; Zeng, W.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, F.; Zhao, R. Shikra: Unleashing Multimodal LLM’s Referential Dialogue Magic. arXiv:2306.15195, arXiv:2306.15195 2023.

- Maaz, M.; Rasheed, H.; Khan, S.; Khan, F.S. Video-chatgpt: Towards detailed video understanding via large vision and language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.05424, arXiv:2306.05424 2023.

- Zeng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, J.; Xia, J.; Wei, G.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, T. What Matters in Training a GPT4-Style Language Model with Multimodal Inputs? arXiv:2307.02469, arXiv:2307.02469 2023.

- Hu, W.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Chen, Z.; Tu, Z. BLIVA: A Simple Multimodal LLM for Better Handling of Text-Rich Visual Questions. arXiv:2308.09936, arXiv:2308.09936 2023.

- IDEFICS. Introducing IDEFICS: An Open Reproduction of State-of-the-Art Visual Language Model. https://huggingface.co/blog/idefics, 2023.

- Awadalla, A.; Gao, I.; Gardner, J.; Hessel, J.; Hanafy, Y.; Zhu, W.; Marathe, K.; Bitton, Y.; Gadre, S.; Sagawa, S. ; others. Openflamingo: An open-source framework for training large autoregressive vision-language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.01390, arXiv:2308.01390 2023.

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Lee, Y.J. Improved baselines with visual instruction tuning. arXiv:2310.03744, arXiv:2310.03744 2023.

- Chen, J.; Zhu, D.; Shen, X.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, P.; Krishnamoorthi, R.; Chandra, V.; Xiong, Y.; Elhoseiny, M. Minigpt-v2: large language model as a unified interface for vision-language multi-task learning. arXiv:2310.09478, arXiv:2310.09478 2023.

- Wang, W.; Lv, Q.; Yu, W.; Hong, W.; Qi, J.; Wang, Y.; Ji, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Song, X. ; others. Cogvlm: Visual expert for pretrained language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.03079, arXiv:2311.03079 2023.

- Chen, L.; Li, J.; Dong, X.; Zhang, P.; He, C.; Wang, J.; Zhao, F.; Lin, D. Sharegpt4v: Improving large multi-modal models with better captions. arXiv:2311.12793, arXiv:2311.12793 2023.

- Ye, Q.; Xu, H.; Ye, J.; Yan, M.; Hu, A.; Liu, H.; Qian, Q.; Zhang, J.; Huang, F.; Zhou, J. mPLUG-Owl2: Revolutionizing Multi-modal Large Language Model with Modality Collaboration. ArXiv, 2311. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.; Liu, C.; Zhang, R.; Gao, P.; Qiu, L.; Xiao, H.; Qiu, H.; Lin, C.; Shao, W.; Chen, K. ; others. Sphinx: The joint mixing of weights, tasks, and visual embeddings for multi-modal large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.07575, arXiv:2311.07575 2023.

- Chu, X.; Qiao, L.; Lin, X.; Xu, S.; Yang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wei, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, B.; Wei, X. ; others. Mobilevlm: A fast, reproducible and strong vision language assistant for mobile devices. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.16886, arXiv:2312.16886 2023.

- Lin, J.; Yin, H.; Ping, W.; Lu, Y.; Molchanov, P.; Tao, A.; Mao, H.; Kautz, J.; Shoeybi, M.; Han, S. 2024; arXiv:cs.CV/2312.07533].

- Cha, J.; Kang, W.; Mun, J.; Roh, B. Honeybee: Locality-enhanced projector for multimodal llm. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 13817–13827.

- Wu, J.; Hu, X.; Wang, Y.; Pang, B.; Soricut, R. Omni-SMoLA: Boosting Generalist Multimodal Models with Soft Mixture of Low-rank Experts. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 14205–14215.

- Chen, S.; Jie, Z.; Ma, L. Llava-mole: Sparse mixture of lora experts for mitigating data conflicts in instruction finetuning mllms. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.16160, arXiv:2401.16160 2024.

- Lin, B.; Tang, Z.; Ye, Y.; Cui, J.; Zhu, B.; Jin, P.; Zhang, J.; Ning, M.; Yuan, L. Moe-llava: Mixture of experts for large vision-language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.15947, arXiv:2401.15947 2024.

- Chu, X.; Qiao, L.; Zhang, X.; Xu, S.; Wei, F.; Yang, Y.; Sun, X.; Hu, Y.; Lin, X.; Zhang, B. ; others. MobileVLM V2: Faster and Stronger Baseline for Vision Language Model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.03766, arXiv:2402.03766 2024.

- He, M.; Liu, Y.; Wu, B.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, T.; Zhao, B. Efficient Multimodal Learning from Data-centric Perspective. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.11530, arXiv:2402.11530 2024.

- Zhou, B.; Hu, Y.; Weng, X.; Jia, J.; Luo, J.; Liu, X.; Wu, J.; Huang, L. Tinyllava: A framework of small-scale large multimodal models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.14289, arXiv:2402.14289 2024.

- Young, A.; Chen, B.; Li, C.; Huang, C.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, G.; Li, H.; Zhu, J.; Chen, J.; Chang, J. ; others. Yi: Open foundation models by 01. ai. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.04652, arXiv:2403.04652 2024.

- McKinzie, B.; Gan, Z.; Fauconnier, J.P.; Dodge, S.; Zhang, B.; Dufter, P.; Shah, D.; Du, X.; Peng, F.; Weers, F. ; others. Mm1: Methods, analysis & insights from multimodal llm pre-training. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.09611, arXiv:2403.09611 2024.

- Qiao, Y.; Yu, Z.; Guo, L.; Chen, S.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, M.; Wu, Q.; Liu, J. Vl-mamba: Exploring state space models for multimodal learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.13600, arXiv:2403.13600 2024.

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, W.; Ding, P.; Huang, S.; Wang, D. Cobra: Extending mamba to multi-modal large language model for efficient inference. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.14520, arXiv:2403.14520 2024.

- Chen, Z.; Wang, W.; Tian, H.; Ye, S.; Gao, Z.; Cui, E.; Tong, W.; Hu, K.; Luo, J.; Ma, Z. ; others. How far are we to gpt-4v? closing the gap to commercial multimodal models with open-source suites. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.16821, arXiv:2404.16821 2024.

- Abdin, M.; Jacobs, S.A.; Awan, A.A.; Aneja, J.; Awadallah, A.; Awadalla, H.; Bach, N.; Bahree, A.; Bakhtiari, A.; Behl, H. ; others. Phi-3 technical report: A highly capable language model locally on your phone. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.14219, arXiv:2404.14219 2024.

- Xu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, D.; Lin, Z.; Ng, S.K.; Feng, J. Pllava: Parameter-free llava extension from images to videos for video dense captioning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.16994, arXiv:2404.16994 2024.

- Yu, Y.; Liao, M.; Wu, J.; Liao, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zeng, W. TextHawk: Exploring Efficient Fine-Grained Perception of Multimodal Large Language Models. CoRR, 2404. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Z.; Yu, Z.; Yu, J.; Ouyang, X.; Zheng, L.; Gai, Z.; Wang, M.; Ding, J. Imp: Highly Capable Large Multimodal Models for Mobile Devices. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.12107, arXiv:2405.12107 2024.

- Laurençon, H.; Tronchon, L.; Cord, M.; Sanh, V. What matters when building vision-language models? arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.02246, arXiv:2405.02246 2024.

- Lu, S.; Li, Y.; Chen, Q.G.; Xu, Z.; Luo, W.; Zhang, K.; Ye, H.J. Ovis: Structural Embedding Alignment for Multimodal Large Language Model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.20797, arXiv:2405.20797 2024.

- Yao, L.; Li, L.; Ren, S.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Sun, X.; Hou, L. DeCo: Decoupling Token Compression from Semantic Abstraction in Multimodal Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.20985, arXiv:2405.20985 2024.

- Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zhu, S.; Kuo, C.W.; Xu, L.; Chen, F.; Jain, J.; Shi, H.; Wen, L. Cumo: Scaling multimodal llm with co-upcycled mixture-of-experts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.05949, arXiv:2405.05949 2024.

- Hong, W.; Wang, W.; Ding, M.; Yu, W.; Lv, Q.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Huang, S.; Ji, J.; Xue, Z. ; others. CogVLM2: Visual Language Models for Image and Video Understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.16500, arXiv:2408.16500 2024.

- Zhang, P.; Dong, X.; Zang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Qian, R.; Chen, L.; Guo, Q.; Duan, H.; Wang, B.; Ouyang, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Sun, P.; Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Yan, H.; He, C.; Zhang, X.; Chen, K.; Dai, J.; Qiao, Y.; Lin, D.; Wang, J. InternLM-XComposer-2. 2024; arXiv:cs.CV/2407.03320]. [Google Scholar]

- Laurençon, H.; Marafioti, A.; Sanh, V.; Tronchon, L. Building and better understanding vision-language models: insights and future directions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.12637, arXiv:2408.12637 2024.

- Ye, J.; Xu, H.; Liu, H.; Hu, A.; Yan, M.; Qian, Q.; Zhang, J.; Huang, F.; Zhou, J. mPLUG-Owl3: Towards Long Image-Sequence Understanding in Multi-Modal Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.04840, arXiv:2408.04840 2024.

- Li, B.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, D.; Zhang, R.; Li, F.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, K.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, C. 2024; arXiv:cs.CV/2408.03326].

- Wang, P.; Bai, S.; Tan, S.; Wang, S.; Fan, Z.; Bai, J.; Chen, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Ge, W. ; others. Qwen2-VL: Enhancing Vision-Language Model’s Perception of the World at Any Resolution. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.12191, arXiv:2409.12191 2024.

- Su, Y.; Lan, T.; Li, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Cai, D. Pandagpt: One model to instruction-follow them all. arXiv:2305.16355, arXiv:2305.16355 2023.

- Li, Y.; Jiang, S.; Hu, B.; Wang, L.; Zhong, W.; Luo, W.; Ma, L.; Zhang, M. Uni-MoE: Scaling Unified Multimodal LLMs with Mixture of Experts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.11273, arXiv:2405.11273 2024.

- Zhang, D.; Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhan, J.; Wang, P.; Zhou, Y.; Qiu, X. Speechgpt: Empowering large language models with intrinsic cross-modal conversational abilities. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.11000, arXiv:2305.11000 2023.

- Wu, J.; Gaur, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, L.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, T.; Li, J.; Liu, S.; Ren, B.; Liu, L. ; others. On decoder-only architecture for speech-to-text and large language model integration. 2023 IEEE Automatic Speech Recognition and Understanding Workshop (ASRU). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–8.

- Tang, C.; Yu, W.; Sun, G.; Chen, X.; Tan, T.; Li, W.; Lu, L.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, C. Salmonn: Towards generic hearing abilities for large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.13289, arXiv:2310.13289 2023.

- Chu, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhou, X.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Yan, Z.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, J. Qwen-audio: Advancing universal audio understanding via unified large-scale audio-language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.07919, arXiv:2311.07919 2023.

- Hu, S.; Zhou, L.; Liu, S.; Chen, S.; Hao, H.; Pan, J.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Sivasankaran, S.; Liu, L. ; others. Wavllm: Towards robust and adaptive speech large language model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.00656, arXiv:2404.00656 2024.

- Das, N.; Dingliwal, S.; Ronanki, S.; Paturi, R.; Huang, D.; Mathur, P.; Yuan, J.; Bekal, D.; Niu, X.; Jayanthi, S.M. ; others. SpeechVerse: A Large-scale Generalizable Audio Language Model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.08295, arXiv:2405.08295 2024.

- Chu, Y.; Xu, J.; Yang, Q.; Wei, H.; Wei, X.; Guo, Z.; Leng, Y.; Lv, Y.; He, J.; Lin, J. ; others. Qwen2-audio technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.10759, arXiv:2407.10759 2024.

- Fang, Q.; Guo, S.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, S.; Feng, Y. LLaMA-Omni: Seamless Speech Interaction with Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.06666, arXiv:2409.06666 2024.

- Jin, Y.; Xu, K.; Xu, K.; Chen, L.; Liao, C.; Tan, J.; Mu, Y. ; others. Unified Language-Vision Pretraining in LLM with Dynamic Discrete Visual Tokenization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.04669, arXiv:2309.04669 2023.

- Yu, L.; Shi, B.; Pasunuru, R.; Muller, B.; Golovneva, O.; Wang, T.; Babu, A.; Tang, B.; Karrer, B.; Sheynin, S.; others. Scaling autoregressive multi-modal models: Pretraining and instruction tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.02591 2023, arXiv:2309.02591 2023, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X.; Dong, L.; Huang, S.; Peng, Z.; Chen, W.; Wei, F. 2024; arXiv:cs.CV/2310.02992].

- Lin, X.V.; Shrivastava, A.; Luo, L.; Iyer, S.; Lewis, M.; Gosh, G.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Aghajanyan, A. MoMa: Efficient Early-Fusion Pre-training with Mixture of Modality-Aware Experts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.21770, arXiv:2407.21770 2024.

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; Tang, H.; Li, D.; Fang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Xie, E.; Yin, H.; Yi, L. ; others. VILA-U: a Unified Foundation Model Integrating Visual Understanding and Generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.04429, arXiv:2409.04429 2024.

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F. ; others. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv:2302.13971, arXiv:2302.13971 2023.

- Dubey, A.; Jauhri, A.; Pandey, A.; Kadian, A.; Al-Dahle, A.; Letman, A.; Mathur, A.; Schelten, A.; Yang, A.; Fan, A. ; others. The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.21783, arXiv:2407.21783 2024.

- Chiang, W.L.; Li, Z.; Lin, Z.; Sheng, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, L.; Zhuang, S.; Zhuang, Y.; Gonzalez, J.E.; Stoica, I.; Xing, E.P. Vicuna: An Open-Source Chatbot Impressing GPT-4 with 90%* ChatGPT Quality, 2023.

- Jiang, A.Q.; Sablayrolles, A.; Mensch, A.; Bamford, C.; Chaplot, D.S.; Casas, D.d.l.; Bressand, F.; Lengyel, G.; Lample, G.; Saulnier, L. ; others. Mistral 7B. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.06825, arXiv:2310.06825 2023.

- Yang, A.; Yang, B.; Hui, B.; Zheng, B.; Yu, B.; Zhou, C.; Li, C.; Li, C.; Liu, D.; Huang, F. ; others. Qwen2 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.10671, arXiv:2407.10671 2024.

- Bi, X.; Chen, D.; Chen, G.; Chen, S.; Dai, D.; Deng, C.; Ding, H.; Dong, K.; Du, Q.; Fu, Z. ; others. Deepseek llm: Scaling open-source language models with longtermism. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.02954, arXiv:2401.02954 2024.

- Kan, K.B.; Mun, H.; Cao, G.; Lee, Y. Mobile-LLaMA: Instruction Fine-Tuning Open-Source LLM for Network Analysis in 5G Networks. IEEE Network 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, G.; Mesnard, T.; Hardin, C.; Dadashi, R.; Bhupatiraju, S.; Pathak, S.; Sifre, L.; Rivière, M.; Kale, M.S.; Love, J. ; others. Gemma: Open models based on gemini research and technology. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.08295, arXiv:2403.08295 2024.

- Hu, S.; Tu, Y.; Han, X.; He, C.; Cui, G.; Long, X.; Zheng, Z.; Fang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, W. ; others. Minicpm: Unveiling the potential of small language models with scalable training strategies. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.06395, arXiv:2404.06395 2024.

- MistralAITeam. Mixtral of experts A high quality Sparse Mixture-of-Experts. [EB/OL], 2023. https://mistral.ai/news/mixtral-of-experts/ Accessed , 2023. 11 December.

- Chung, H.W.; Hou, L.; Longpre, S.; Zoph, B.; Tay, Y.; Fedus, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Dehghani, M.; Brahma, S.; Webson, A.; Gu, S.S.; Dai, Z.; Suzgun, M.; Chen, X.; Chowdhery, A.; Castro-Ros, A.; Pellat, M.; Robinson, K.; Valter, D.; Narang, S.; Mishra, G.; Yu, A.; Zhao, V.; Huang, Y.; Dai, A.; Yu, H.; Petrov, S.; Chi, E.H.; Dean, J.; Devlin, J.; Roberts, A.; Zhou, D.; Le, Q.V.; Wei, J. Scaling Instruction-Finetuned Language Models. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2024, 25, 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Djolonga, J.; Padlewski, P.; Mustafa, B.; Changpinyo, S.; Wu, J.; Ruiz, C.R.; Goodman, S.; Wang, X.; Tay, Y.; Shakeri, S.; Dehghani, M.; Salz, D.; Lucic, M.; Tschannen, M.; Nagrani, A.; Hu, H.; Joshi, M.; Pang, B.; Montgomery, C.; Pietrzyk, P.; Ritter, M.; Piergiovanni, A.; Minderer, M.; Pavetic, F.; Waters, A.; Li, G.; Alabdulmohsin, I.; Beyer, L.; Amelot, J.; Lee, K.; Steiner, A.P.; Li, Y.; Keysers, D.; Arnab, A.; Xu, Y.; Rong, K.; Kolesnikov, A.; Seyedhosseini, M.; Angelova, A.; Zhai, X.; Houlsby, N.; Soricut, R. 2023; arXiv:cs.CV/2305.18565].

- Bachmann, R.; Kar, O.F.; Mizrahi, D.; Garjani, A.; Gao, M.; Griffiths, D.; Hu, J.; Dehghan, A.; Zamir, A. 2024; arXiv:cs.CV/2406.09406].

- Mizrahi, D.; Bachmann, R.; Kar, O.F.; Yeo, T.; Gao, M.; Dehghan, A.; Zamir, A. 2023; arXiv:cs.CV/2312.06647].

- Hendrycks, D.; Gimpel, K. 2023; arXiv:cs.LG/1606.08415].

- Dong, X.; Zhang, P.; Zang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, B.; Ouyang, L.; Zhang, S.; Duan, H.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Yan, H.; Gao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Chen, K.; He, C.; Zhang, X.; Dai, J.; Qiao, Y.; Lin, D.; Wang, J. 2024; arXiv:cs.CV/2404.06512].

- Kar, O.F.; Tonioni, A.; Poklukar, P.; Kulshrestha, A.; Zamir, A.; Tombari, F. BRAVE: Broadening the visual encoding of vision-language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.07204, arXiv:2404.07204 2024.

- Lu, J.; Gan, R.; Zhang, D.; Wu, X.; Wu, Z.; Sun, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, P.; Song, Y. Lyrics: Boosting fine-grained language-vision alignment and comprehension via semantic-aware visual objects. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.05278, arXiv:2312.05278 2023.

- Chen, K.; Shen, D.; Zhong, H.; Zhong, H.; Xia, K.; Xu, D.; Yuan, W.; Hu, Y.; Wen, B.; Zhang, T. ; others. Evlm: An efficient vision-language model for visual understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.14177, arXiv:2407.14177 2024.

- FedusF, W.; Zoph, B.; Shazeer, N. Switch transformers: Scaling to trillion parameter models with simple and efficient sparsity. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2022, 23, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, W.; Jiang, J.; Wang, F.; Tang, J.; Kim, S.; Huang, J. A survey on mixture of experts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.06204, arXiv:2407.06204 2024.

- Shen, S.; Hou, L.; Zhou, Y.; Du, N.; Longpre, S.; Wei, J.; Chung, H.W.; Zoph, B.; Fedus, W.; Chen, X. ; others. Mixture-of-experts meets instruction tuning: A winning combination for large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.14705, arXiv:2305.14705 2023.

- Komatsuzaki, A.; Puigcerver, J.; Lee-Thorp, J.; Ruiz, C.R.; Mustafa, B.; Ainslie, J.; Tay, Y.; Dehghani, M.; Houlsby, N. Sparse upcycling: Training mixture-of-experts from dense checkpoints. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.05055, arXiv:2212.05055 2022.

- Sharma, P.; Ding, N.; Goodman, S.; Soricut, R. Conceptual captions: A cleaned, hypernymed, image alt-text dataset for automatic image captioning. ACL, 2018, pp. 2556–2565.

- Changpinyo, S.; Sharma, P.; Ding, N.; Soricut, R. Conceptual 12M: Pushing Web-Scale Image-Text Pre-Training To Recognize Long-Tail Visual Concepts. 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2021, pp. 3557–3567. [CrossRef]

- Byeon, M.; Park, B.; Kim, H.; Lee, S.; Baek, W.; Kim, S. Coyo-700m: Image-text pair dataset, 2022.

- Chen, X.; Fang, H.; Lin, T.Y.; Vedantam, R.; Gupta, S.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft coco captions: Data collection and evaluation server. arXiv:1504.00325, arXiv:1504.00325 2015.

- Srinivasan, K.; Raman, K.; Chen, J.; Bendersky, M.; Najork, M. Wit: Wikipedia-based image text dataset for multimodal multilingual machine learning. Proceedings of the 44th international ACM SIGIR conference on research and development in information retrieval, 2021, pp. 2443–2449.

- Desai, K.; Kaul, G.; Aysola, Z.; Johnson, J. RedCaps: Web-curated image-text data created by the people, for the people. Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems Track on Datasets and Benchmarks; Vanschoren, J.; Yeung, S., Eds., 2021, Vol. 1.

- Schuhmann, C.; Vencu, R.; Beaumont, R.; Kaczmarczyk, R.; Mullis, C.; Katta, A.; Coombes, T.; Jitsev, J.; Komatsuzaki, A. Laion-400m: Open dataset of clip-filtered 400 million image-text pairs. arXiv:2111.02114, arXiv:2111.02114 2021.

- Schuhmann, C.; Beaumont, R.; Vencu, R.; Gordon, C.; Wightman, R.; Cherti, M.; Coombes, T.; Katta, A.; Mullis, C.; Wortsman, M.; others. Laion-5b: An open large-scale dataset for training next generation image-text models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 25278–25294. [Google Scholar]

- Ordonez, V.; Kulkarni, G.; Berg, T. Im2Text: Describing Images Using 1 Million Captioned Photographs. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Shawe-Taylor, J.; Zemel, R.; Bartlett, P.; Pereira, F.; Weinberger, K., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2011, Vol. 24.

- Gadre, S.Y.; Ilharco, G.; Fang, A.; Hayase, J.; Smyrnis, G.; Nguyen, T.; Marten, R.; Wortsman, M.; Ghosh, D.; Zhang, J.; others. Datacomp: In search of the next generation of multimodal datasets. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Q.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, X.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wang, X.; Liu, J. Capsfusion: Rethinking image-text data at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.20550, arXiv:2310.20550 2023.

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, G.; Zhu, B.; Song, Q.; Ge, G.; Chen, H.; Qiao, G.; Peng, R.; Wu, L.; Wang, J. Taisu: A 166m large-scale high-quality dataset for chinese vision-language pre-training. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 16705–16717. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, B.; Wu, W.; Bai, H.; Timofeev, A.; Du, X.; Gan, Z.; Shan, J.; Chuah, C.N.; Yang, Y.; Cao, M. 2024; arXiv:cs.CV/2310.07699].

- Gu, J.; Meng, X.; Lu, G.; Hou, L.; Minzhe, N.; Liang, X.; Yao, L.; Huang, R.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, X.; others. Wukong: A 100 million large-scale chinese cross-modal pre-training benchmark. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 26418–26431. [Google Scholar]

- Sharifzadeh, S.; Kaplanis, C.; Pathak, S.; Kumaran, D.; Ilic, A.; Mitrovic, J.; Blundell, C.; Banino, A. Synth 2: Boosting Visual-Language Models with Synthetic Captions and Image Embeddings. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.07750, arXiv:2403.07750 2024.

- Singla, V.; Yue, K.; Paul, S.; Shirkavand, R.; Jayawardhana, M.; Ganjdanesh, A.; Huang, H.; Bhatele, A.; Somepalli, G.; Goldstein, T. From Pixels to Prose: A Large Dataset of Dense Image Captions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.10328, arXiv:2406.10328 2024.

- Thomee, B.; Shamma, D.A.; Friedland, G.; Elizalde, B.; Ni, K.; Poland, D.; Borth, D.; Li, L.J. Yfcc100m: The new data in multimedia research. Communications of the ACM 2016, 59, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onoe, Y.; Rane, S.; Berger, Z.; Bitton, Y.; Cho, J.; Garg, R.; Ku, A.; Parekh, Z.; Pont-Tuset, J.; Tanzer, G. ; others. DOCCI: Descriptions of Connected and Contrasting Images. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.19753, arXiv:2404.19753 2024.

- Garg, R.; Burns, A.; Ayan, B.K.; Bitton, Y.; Montgomery, C.; Onoe, Y.; Bunner, A.; Krishna, R.; Baldridge, J.; Soricut, R. ImageInWords: Unlocking Hyper-Detailed Image Descriptions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.02793, arXiv:2405.02793 2024.

- Urbanek, J.; Bordes, F.; Astolfi, P.; Williamson, M.; Sharma, V.; Romero-Soriano, A. A picture is worth more than 77 text tokens: Evaluating clip-style models on dense captions. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 26700–26709.

- Xu, H.; Xie, S.; Tan, X.E.; Huang, P.Y.; Howes, R.; Sharma, V.; Li, S.W.; Ghosh, G.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Feichtenhofer, C. Demystifying clip data. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.16671, arXiv:2309.16671 2023.

- Wang, W.; Shi, M.; Li, Q.; Wang, W.; Huang, Z.; Xing, L.; Chen, Z.; Li, H.; Zhu, X.; Cao, Z. ; others. The all-seeing project: Towards panoptic visual recognition and understanding of the open world. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.01907, arXiv:2308.01907 2023.

- Miech, A.; Zhukov, D.; Alayrac, J.B.; Tapaswi, M.; Laptev, I.; Sivic, J. Howto100m: Learning a text-video embedding by watching hundred million narrated video clips. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2019, pp. 2630–2640.

- Grauman, K.; Westbury, A.; Byrne, E.; Chavis, Z.; Furnari, A.; Girdhar, R.; Hamburger, J.; Jiang, H.; Liu, M.; Liu, X. ; others. Ego4d: Around the world in 3,000 hours of egocentric video. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022, pp. 18995–19012.

- Nagrani, A.; Seo, P.H.; Seybold, B.; Hauth, A.; Manen, S.; Sun, C.; Schmid, C. Learning audio-video modalities from image captions. European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, 2022, pp. 407–426.

- Bain, M.; Nagrani, A.; Varol, G.; Zisserman, A. Frozen in Time: A Joint Video and Image Encoder for End-to-End Retrieval. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2021, pp. 1728–1738.

- Chen, T.S.; Siarohin, A.; Menapace, W.; Deyneka, E.; Chao, H.w.; Jeon, B.E.; Fang, Y.; Lee, H.Y.; Ren, J.; Yang, M.H. ; others. Panda-70m: Captioning 70m videos with multiple cross-modality teachers. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 13320–13331.

- Zhu, B.; Lin, B.; Ning, M.; Yan, Y.; Cui, J.; Wang, H.; Pang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z. ; others. Languagebind: Extending video-language pretraining to n-modality by language-based semantic alignment. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.01852, arXiv:2310.01852 2023.

- Drossos, K.; Lipping, S.; Virtanen, T. Clotho: An audio captioning dataset. ICASSP 2020-2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2020, pp. 736–740.

- Kim, C.D.; Kim, B.; Lee, H.; Kim, G. Audiocaps: Generating captions for audios in the wild. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), 2019, pp. 119–132.

- Mei, X.; Meng, C.; Liu, H.; Kong, Q.; Ko, T.; Zhao, C.; Plumbley, M.D.; Zou, Y.; Wang, W. Wavcaps: A chatgpt-assisted weakly-labelled audio captioning dataset for audio-language multimodal research. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing.

- Gemmeke, J.F.; Ellis, D.P.; Freedman, D.; Jansen, A.; Lawrence, W.; Moore, R.C.; Plakal, M.; Ritter, M. Audio set: An ontology and human-labeled dataset for audio events. 2017 IEEE international conference on acoustics, speech and signal processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2017, pp. 776–780.

- Xue, H.; Hang, T.; Zeng, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, B.; Yang, H.; Fu, J.; Guo, B. Advancing high-resolution video-language representation with large-scale video transcriptions. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022, pp. 5036–5045.

- Zhou, L.; Xu, C.; Corso, J. Towards automatic learning of procedures from web instructional videos. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2018, Vol. 32.

- Sigurdsson, G.A.; Varol, G.; Wang, X.; Farhadi, A.; Laptev, I.; Gupta, A. Hollywood in homes: Crowdsourcing data collection for activity understanding. Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, –14, 2016, Proceedings, Part I 14. Springer, 2016, pp. 510–526. 11 October.

- Shang, X.; Di, D.; Xiao, J.; Cao, Y.; Yang, X.; Chua, T.S. Annotating Objects and Relations in User-Generated Videos. Proceedings of the 2019 on International Conference on Multimedia Retrieval. ACM, 2019, pp. 279–287.

- Goyal, R.; Ebrahimi Kahou, S.; Michalski, V.; Materzynska, J.; Westphal, S.; Kim, H.; Haenel, V.; Fruend, I.; Yianilos, P.; Mueller-Freitag, M. ; others. The" something something" video database for learning and evaluating visual common sense. Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 5842–5850.

- Li, J.; Wong, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Kankanhalli, M.S. Video storytelling: Textual summaries for events. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2019, 22, 554–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yang, H.; Tuo, Z.; He, H.; Zhu, J.; Fu, J.; Liu, J. VideoFactory: Swap Attention in Spatiotemporal Diffusions for Text-to-Video Generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.10874, arXiv:2305.10874 2023.

- Hu, A.; Xu, H.; Ye, J.; Yan, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, B.; Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Jin, Q.; Huang, F.; Zhou, J. mPLUG-DocOwl 1.5: Unified Structure Learning for OCR-free Document Understanding. ArXiv, 2403. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, A.; Xu, H.; Ye, J.; Yan, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, B.; Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Jin, Q.; Huang, F. ; others. mplug-docowl 1.5: Unified structure learning for ocr-free document understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.12895, arXiv:2403.12895 2024.

- Ordonez, V.; Kulkarni, G.; Berg, T. Im2text: Describing images using 1 million captioned photographs. Advances in neural information processing systems 2011, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Changpinyo, S.; Sharma, P.; Ding, N.; Soricut, R. Conceptual 12m: Pushing web-scale image-text pre-training to recognize long-tail visual concepts. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021, pp. 3558–3568.

- Yang, D.; Huang, S.; Lu, C.; Han, X.; Zhang, H.; Gao, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, H. Vript: A Video Is Worth Thousands of Words. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.06040, arXiv:2406.06040 2024.

- Wu, Y.; Chen, K.; Zhang, T.; Hui, Y.; Berg-Kirkpatrick, T.; Dubnov, S. Large-scale contrastive language-audio pretraining with feature fusion and keyword-to-caption augmentation. ICASSP 2023-2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–5.

- Chen, S.; Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, M.; Zhu, X.; Liu, J. Vast: A vision-audio-subtitle-text omni-modality foundation model and dataset. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 72842–72866. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; He, X.; Guo, L.; Zhu, X.; Wang, W.; Tang, J.; Liu, J. Valor: Vision-audio-language omni-perception pretraining model and dataset. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.08345, arXiv:2304.08345 2023.

- Kong, Z.; Lee, S.g.; Ghosal, D.; Majumder, N.; Mehrish, A.; Valle, R.; Poria, S.; Catanzaro, B. Improving text-to-audio models with synthetic captions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.15487, arXiv:2406.15487 2024.

- Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Chen, J.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.F.; Wang, W.Y. Vatex: A large-scale, high-quality multilingual dataset for video-and-language research. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2019, pp. 4581–4591.

- Anne Hendricks, L.; Wang, O.; Shechtman, E.; Sivic, J.; Darrell, T.; Russell, B. Localizing moments in video with natural language. Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 5803–5812.

- Fang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Molchanov, P.; Cho, J.H.; Pavone, M.; Han, S.; Yin, H. VILA2: VILA Augmented VILA. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.17453, arXiv:2407.17453 2024.

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Wu, Q.; Lee, Y.J. Visual instruction tuning. arXiv:2304.08485, arXiv:2304.08485 2023.

- Tang, B.J.; Boggust, A.; Satyanarayan, A. Vistext: A benchmark for semantically rich chart captioning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.05356, arXiv:2307.05356 2023.

- Wang, B.; Li, G.; Zhou, X.; Chen, Z.; Grossman, T.; Li, Y. Screen2words: Automatic mobile UI summarization with multimodal learning. The 34th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, 2021, pp. 498–510.

- Panayotov, V.; Chen, G.; Povey, D.; Khudanpur, S. Librispeech: an asr corpus based on public domain audio books. 2015 IEEE international conference on acoustics, speech and signal processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2015, pp. 5206–5210.

- Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Xu, R.; Wang, P.; Feng, X.; Kong, L.; Liu, Q. Multimodal arxiv: A dataset for improving scientific comprehension of large vision-language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.00231, arXiv:2403.00231 2024.

- Li, X.; Zhang, F.; Diao, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Duan, L.Y. Densefusion-1m: Merging vision experts for comprehensive multimodal perception. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.08303, arXiv:2407.08303 2024.

- Chen, L.; Wei, X.; Li, J.; Dong, X.; Zhang, P.; Zang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Duan, H.; Lin, B.; Tang, Z. ; others. Sharegpt4video: Improving video understanding and generation with better captions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.04325, arXiv:2406.04325 2024.

- Erfei, C.; Yinan, H.; Zheng, M.; Zhe, C.; Hao, T.; Weiyun, W.; Kunchang, L.; Yi, W.; Wenhai, W.; Xizhou, Z.; Lewei, L.; Tong, L.; Yali, W.; Limin, W.; Yu, Q.; Jifeng, D. Comprehensive Multimodal Annotations With GPT-4o, 2024.

- Zhu, W.; Hessel, J.; Awadalla, A.; Gadre, S.Y.; Dodge, J.; Fang, A.; Yu, Y.; Schmidt, L.; Wang, W.Y.; Choi, Y. Multimodal c4: An open, billion-scale corpus of images interleaved with text. NeurIPS 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Laurençon, H.; Saulnier, L.; Tronchon, L.; Bekman, S.; Singh, A.; Lozhkov, A.; Wang, T.; Karamcheti, S.; Rush, A.; Kiela, D.; others. Obelics: An open web-scale filtered dataset of interleaved image-text documents. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Awadalla, A.; Xue, L.; Lo, O.; Shu, M.; Lee, H.; Guha, E.K.; Jordan, M.; Shen, S.; Awadalla, M.; Savarese, S. ; others. MINT-1T: Scaling Open-Source Multimodal Data by 10x: A Multimodal Dataset with One Trillion Tokens. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.11271, arXiv:2406.11271 2024.

- Li, Q.; Chen, Z.; Wang, W.; Wang, W.; Ye, S.; Jin, Z.; Chen, G.; He, Y.; Gao, Z.; Cui, E. ; others. OmniCorpus: An Unified Multimodal Corpus of 10 Billion-Level Images Interleaved with Text. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.08418, arXiv:2406.08418 2024.

- Huang, S.; Dong, L.; Wang, W.; Hao, Y.; Singhal, S.; Ma, S.; Lv, T.; Cui, L.; Mohammed, O.K.; Patra, B.; others. Language is not all you need: Aligning perception with language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 72096–72109. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, K.; Yu, J.; Ma, X.; Li, X.; Chen, G.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y. ; others. Internvid: A large-scale video-text dataset for multimodal understanding and generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.06942, arXiv:2307.06942 2023.

- Wang, A.J.; Li, L.; Lin, K.Q.; Wang, J.; Lin, K.; Yang, Z.; Wang, L.; Shou, M.Z. COSMO: COntrastive Streamlined MultimOdal Model with Interleaved Pre-Training. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.00849, arXiv:2401.00849 2024.

- Sun, Q.; Yu, Q.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, H.; Liu, J.; Huang, T.; Wang, X. Generative pretraining in multimodality. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.05222, arXiv:2307.05222 2023.

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. Journal of machine learning research 2020, 21, 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Soldaini, L.; Kinney, R.; Bhagia, A.; Schwenk, D.; Atkinson, D.; Authur, R.; Bogin, B.; Chandu, K.; Dumas, J.; Elazar, Y. ; others. Dolma: An open corpus of three trillion tokens for language model pretraining research. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.00159, arXiv:2402.00159 2024.

- Penedo, G.; Malartic, Q.; Hesslow, D.; Cojocaru, R.; Cappelli, A.; Alobeidli, H.; Pannier, B.; Almazrouei, E.; Launay, J. The RefinedWeb dataset for Falcon LLM: outperforming curated corpora with web data, and web data only. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.01116, arXiv:2306.01116 2023.

- Yuan, S.; Zhao, H.; Du, Z.; Ding, M.; Liu, X.; Cen, Y.; Zou, X.; Yang, Z.; Tang, J. Wudaocorpora: A super large-scale chinese corpora for pre-training language models. AI Open 2021, 2, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekar, S.; Zhang, Y.; Aneja, J.; Mendes, C.C.T.; Del Giorno, A.; Gopi, S.; Javaheripi, M.; Kauffmann, P.; de Rosa, G.; Saarikivi, O. ; others. Textbooks are all you need. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.11644, arXiv:2306.11644 2023.

- Hernandez, D.; Brown, T.; Conerly, T.; DasSarma, N.; Drain, D.; El-Showk, S.; Elhage, N.; Hatfield-Dodds, Z.; Henighan, T.; Hume, T. ; others. Scaling laws and interpretability of learning from repeated data. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.10487, arXiv:2205.10487 2022.

- Suárez, P.J.O.; Sagot, B.; Romary, L. Asynchronous pipeline for processing huge corpora on medium to low resource infrastructures. 7th Workshop on the Challenges in the Management of Large Corpora (CMLC-7). Leibniz-Institut für Deutsche Sprache, 2019.

- Computer, T. RedPajama: an Open Dataset for Training Large Language Models 2023.

- Lee, K.; Ippolito, D.; Nystrom, A.; Zhang, C.; Eck, D.; Callison-Burch, C.; Carlini, N. Deduplicating training data makes language models better. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.06499, arXiv:2107.06499 2021.

- Silcock, E.; D’Amico-Wong, L.; Yang, J.; Dell, M. Noise-robust de-duplication at scale. Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2022.

- Kaddour, J. The minipile challenge for data-efficient language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.08442, arXiv:2304.08442 2023.

- Abbas, A.; Tirumala, K.; Simig, D.; Ganguli, S.; Morcos, A.S. Semdedup: Data-efficient learning at web-scale through semantic deduplication. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.09540, arXiv:2303.09540 2023.

- Zauner, C. Implementation and benchmarking of perceptual image hash functions 2010.

- Marino, K.; Rastegari, M.; Farhadi, A.; Mottaghi, R. Ok-vqa: A visual question answering benchmark requiring external knowledge. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2019, pp. 3195–3204.

- Zhang, P.; Li, C.; Qiao, L.; Cheng, Z.; Pu, S.; Niu, Y.; Wu, F. VSR: a unified framework for document layout analysis combining vision, semantics and relations. Document Analysis and Recognition–ICDAR 2021: 16th International Conference, Lausanne, Switzerland, –10, 2021, Proceedings, Part I 16. Springer, 2021, pp. 115–130. 5 September.

- Schwenk, D.; Khandelwal, A.; Clark, C.; Marino, K.; Mottaghi, R. A-okvqa: A benchmark for visual question answering using world knowledge. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gurari, D.; Li, Q.; Stangl, A.J.; Guo, A.; Lin, C.; Grauman, K.; Luo, J.; Bigham, J.P. Vizwiz grand challenge: Answering visual questions from blind people. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2018, pp. 3608–3617.

- Zhu, Y.; Groth, O.; Bernstein, M.; Fei-Fei, L. Visual7w: Grounded question answering in images. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 4995–5004.

- Kiela, D.; Firooz, H.; Mohan, A.; Goswami, V.; Singh, A.; Ringshia, P.; Testuggine, D. The hateful memes challenge: Detecting hate speech in multimodal memes. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 2611–2624. [Google Scholar]

- Acharya, M.; Kafle, K.; Kanan, C. TallyQA: Answering complex counting questions. Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2019, Vol. 33, pp. 8076–8084.

- Xia, H.; Lan, R.; Li, H.; Song, S. ST-VQA: shrinkage transformer with accurate alignment for visual question answering. Applied Intelligence 2023, 53, 20967–20978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Palzer, D.; Li, J.; Fosler-Lussier, E.; Xiao, N. MapQA: A dataset for question answering on choropleth maps. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.08545, arXiv:2211.08545 2022.

- Shah, S.; Mishra, A.; Yadati, N.; Talukdar, P.P. Kvqa: Knowledge-aware visual question answering. Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2019, Vol. 33, pp. 8876–8884.

- Lerner, P.; Ferret, O.; Guinaudeau, C.; Le Borgne, H.; Besançon, R.; Moreno, J.G.; Lovón Melgarejo, J. ViQuAE, a dataset for knowledge-based visual question answering about named entities. 45th ACM SIGIR, 2022, pp. 3108–3120.

- Yu, Z.; Xu, D.; Yu, J.; Yu, T.; Zhao, Z.; Zhuang, Y.; Tao, D. Activitynet-qa: A dataset for understanding complex web videos via question answering. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2019, Vol. 33, pp. 9127–9134.

- Xiao, J.; Shang, X.; Yao, A.; Chua, T.S. Next-qa: Next phase of question-answering to explaining temporal actions. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021, pp. 9777–9786.

- Yi, K.; Gan, C.; Li, Y.; Kohli, P.; Wu, J.; Torralba, A.; Tenenbaum, J.B. Clevrer: Collision events for video representation and reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.01442, arXiv:1910.01442 2019.

- Yang, A.; Miech, A.; Sivic, J.; Laptev, I.; Schmid, C. Learning to answer visual questions from web videos. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.05019, arXiv:2205.05019 2022.

- Jang, Y.; Song, Y.; Yu, Y.; Kim, Y.; Kim, G. Tgif-qa: Toward spatio-temporal reasoning in visual question answering. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 2758–2766.

- Wu, B.; Yu, S.; Chen, Z.; Tenenbaum, J.B.; Gan, C. Star: A benchmark for situated reasoning in real-world videos. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.09711, arXiv:2405.09711 2024.

- Lei, J.; Yu, L.; Bansal, M.; Berg, T.L. Tvqa: Localized, compositional video question answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.01696, arXiv:1809.01696 2018.

- Jahagirdar, S.; Mathew, M.; Karatzas, D.; Jawahar, C. Watching the news: Towards videoqa models that can read. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 4441–4450.

- Marti, U.V.; Bunke, H. The IAM-database: an English sentence database for offline handwriting recognition. International journal on document analysis and recognition 2002, 5, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Shekhar, S.; Singh, A.K.; Chakraborty, A. Ocr-vqa: Visual question answering by reading text in images. 2019 ICDAR. IEEE, 2019, pp. 947–952.

- Singh, A.; Natarajan, V.; Shah, M.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, X.; Batra, D.; Parikh, D.; Rohrbach, M. Towards vqa models that can read. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2019, pp. 8317–8326.

- Wendler, C. wendlerc/RenderedText, 2023.

- Kim, G.; Hong, T.; Yim, M.; Nam, J.; Park, J.; Yim, J.; Hwang, W.; Yun, S.; Han, D.; Park, S. OCR-Free Document Understanding Transformer. European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2022.

- Mathew, M.; Karatzas, D.; Jawahar, C. Docvqa: A dataset for vqa on document images. WACV, 2021, pp. 2200–2209.

- Kantharaj, S.; Leong, R.T.K.; Lin, X.; Masry, A.; Thakkar, M.; Hoque, E.; Joty, S. Chart-to-text: A large-scale benchmark for chart summarization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.06486, arXiv:2203.06486 2022.

- Kafle, K.; Price, B.; Cohen, S.; Kanan, C. Dvqa: Understanding data visualizations via question answering. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 5648–5656.

- Masry, A.; Long, D.X.; Tan, J.Q.; Joty, S.; Hoque, E. Chartqa: A benchmark for question answering about charts with visual and logical reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.10244, arXiv:2203.10244 2022.

- Methani, N.; Ganguly, P.; Khapra, M.M.; Kumar, P. Plotqa: Reasoning over scientific plots. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 2020, pp. 1527–1536.

- Kahou, S.E.; Michalski, V.; Atkinson, A.; Kádár, Á.; Trischler, A.; Bengio, Y. Figureqa: An annotated figure dataset for visual reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.07300, arXiv:1710.07300 2017.

- Mathew, M.; Bagal, V.; Tito, R.; Karatzas, D.; Valveny, E.; Jawahar, C. Infographicvqa. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 2022, pp. 1697–1706.

- Lu, P.; Qiu, L.; Chang, K.W.; Wu, Y.N.; Zhu, S.C.; Rajpurohit, T.; Clark, P.; Kalyan, A. Dynamic prompt learning via policy gradient for semi-structured mathematical reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.14610, arXiv:2209.14610 2022.

- Hsiao, Y.C.; Zubach, F.; Wang, M. ; others. Screenqa: Large-scale question-answer pairs over mobile app screenshots. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.08199, arXiv:2209.08199 2022.

- Tanaka, R.; Nishida, K.; Yoshida, S. Visualmrc: Machine reading comprehension on document images. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2021, Vol. 35, pp. 13878–13888.

- Van Landeghem, J.; Tito, R. ; Borchmann,.; Pietruszka, M.; Joziak, P.; Powalski, R.; Jurkiewicz, D.; Coustaty, M.; Anckaert, B.; Valveny, E.; others. Document understanding dataset and evaluation (dude). Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 19528–19540.

- Tito, R.; Karatzas, D.; Valveny, E. Hierarchical multimodal transformers for multipage docvqa. Pattern Recognition 2023, 144, 109834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Pi, R.; Zhang, J.; Ye, J.; Zhong, W.; Wang, Y.; Hong, L.; Han, J.; Xu, H.; Li, Z. ; others. G-llava A diagram is worth a dozen images.: Solving geometric problem with multi-modal large language model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.11370, arXiv:2312.11370 2023.

- Cao, J.; Xiao, J. An augmented benchmark dataset for geometric question answering through dual parallel text encoding. Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 1511–1520.

- Kazemi, M.; Alvari, H.; Anand, A.; Wu, J.; Chen, X.; Soricut, R. Geomverse: A systematic evaluation of large models for geometric reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.12241, arXiv:2312.12241 2023.

- Zhang, C.; Gao, F.; Jia, B.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, S.C. Raven: A dataset for relational and analogical visual reasoning. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019, pp. 5317–5327.

- Saikh, T.; Ghosal, T.; Mittal, A.; Ekbal, A.; Bhattacharyya, P. Scienceqa: A novel resource for question answering on scholarly articles. International Journal on Digital Libraries 2022, 23, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Gong, R.; Jiang, S.; Qiu, L.; Huang, S.; Liang, X.; Zhu, S.C. Inter-GPS: Interpretable geometry problem solving with formal language and symbolic reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2105.04165, arXiv:2105.04165 2021.

- Kembhavi, A.; Salvato, M.; Kolve, E.; Seo, M.; Hajishirzi, H.; Farhadi, A. A diagram is worth a dozen images. Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, –14, 2016, Proceedings, Part IV 14. Springer, 2016, pp. 235–251. 11 October.

- Lu, P.; Qiu, L.; Chen, J.; Xia, T.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yu, Z.; Liang, X.; Zhu, S.C. Iconqa: A new benchmark for abstract diagram understanding and visual language reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.13214, arXiv:2110.13214 2021.

- Kembhavi, A.; Seo, M.; Schwenk, D.; Choi, J.; Farhadi, A.; Hajishirzi, H. Are you smarter than a sixth grader? textbook question answering for multimodal machine comprehension. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 4999–5007.

- Laurençon, H.; Tronchon, L.; Sanh, V. Unlocking the conversion of Web Screenshots into HTML Code with the WebSight Dataset. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.09029, arXiv:2403.09029 2024.

- Belouadi, J.; Lauscher, A.; Eger, S. Automatikz: Text-guided synthesis of scientific vector graphics with tikz. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.00367, arXiv:2310.00367 2023.

- Si, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, R.; Yang, D. Design2Code: How Far Are We From Automating Front-End Engineering? arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.03163, arXiv:2403.03163 2024.

- Lindström, A.D.; Abraham, S.S. Clevr-math: A dataset for compositional language, visual and mathematical reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.05358, arXiv:2208.05358 2022.

- Gupta, T.; Marten, R.; Kembhavi, A.; Hoiem, D. Grit: General robust image task benchmark. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.13653, arXiv:2204.13653 2022.

- Krishna, R.; Zhu, Y.; Groth, O.; Johnson, J.; Hata, K.; Kravitz, J.; Chen, S.; Kalantidis, Y.; Li, L.J.; Shamma, D.A.; others. Visual genome: Connecting language and vision using crowdsourced dense image annotations. International journal of computer vision 2017, 123, 32–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Li, Z.; Zhang, T.; Peng, C.; Yu, G.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Sun, J. Objects365: A large-scale, high-quality dataset for object detection. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2019, pp. 8430–8439.

- Xu, Z.; Shen, Y.; Huang, L. Multiinstruct: Improving multi-modal zero-shot learning via instruction tuning. arXiv:2212.10773, arXiv:2212.10773 2022.

- Jiang, D.; He, X.; Zeng, H.; Wei, C.; Ku, M.; Liu, Q.; Chen, W. Mantis: Interleaved multi-image instruction tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.01483, arXiv:2405.01483 2024.

- Chen, F.; Han, M.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, J.; Xu, S.; Xu, B. X-LLM: Bootstrapping Advanced Large Language Models by Treating Multi-Modalities as Foreign Languages. arXiv:2305.04160, arXiv:2305.04160 2023.

- Li, L.; Yin, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, L.; Wang, P.; Ren, S.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Xu, J.; Sun, X. ; others. M3IT: A Large-Scale Dataset towards Multi-Modal Multilingual Instruction Tuning. arXiv:2306.04387, arXiv:2306.04387 2023.

- Li, Y.; Zhang, G.; Ma, Y.; Yuan, R.; Zhu, K.; Guo, H.; Liang, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, J.; Wu, S. ; others. OmniBench: Towards The Future of Universal Omni-Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.15272, arXiv:2409.15272 2024.

- Li, K.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Chen, G.; Luo, P.; Wang, L.; Qiao, Y. 2023; arXiv:cs.CV/2311.17005].

- Ren, S.; Yao, L.; Li, S.; Sun, X.; Hou, L. TimeChat: A Time-sensitive Multimodal Large Language Model for Long Video Understanding. ArXiv, 2312. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Feng, C.; Shao, R.; Ashby, T.; Shen, Y.; Jin, D.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, Q.; Huang, L. Vision-flan: Scaling human-labeled tasks in visual instruction tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.11690, arXiv:2402.11690 2024.

- Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Ye, Q.; Chong, D.; Zhou, P.; Hua, Y. Qilin-med-vl: Towards chinese large vision-language model for general healthcare. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.17956, arXiv:2310.17956 2023.

- Gong, T.; Lyu, C.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, M.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, K.; Zhang, W.; Luo, P.; Chen, K. Multimodal-gpt: A vision and language model for dialogue with humans. arXiv:2305.04790, arXiv:2305.04790 2023.

- Zhao, H.; Cai, Z.; Si, S.; Ma, X.; An, K.; Chen, L.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Han, W.; Chang, B. Mmicl: Empowering vision-language model with multi-modal in-context learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.07915, arXiv:2309.07915 2023.

- Fan, L.; Krishnan, D.; Isola, P.; Katabi, D.; Tian, Y. Improving clip training with language rewrites. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, B.; Wu, W.; Bai, H.; Timofeev, A.; Du, X.; Gan, Z.; Shan, J.; Chuah, C.N. ; others. VeCLIP: Improving CLIP Training via Visual-Enriched Captions. European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, 2025, pp. 111–127.

- Yu, Q.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, X.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, F.; Cao, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, J. Capsfusion: Rethinking image-text data at scale. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 14022–14032.

- Pi, R.; Gao, J.; Diao, S.; Pan, R.; Dong, H.; Zhang, J.; Yao, L.; Han, J.; Xu, H.; Zhang, L.K.T. DetGPT: Detect What You Need via Reasoning. arXiv:2305.14167, arXiv:2305.14167 2023.

- Zhao, L.; Yu, E.; Ge, Z.; Yang, J.; Wei, H.; Zhou, H.; Sun, J.; Peng, Y.; Dong, R.; Han, C. ; others. Chatspot: Bootstrapping multimodal llms via precise referring instruction tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.09474, arXiv:2307.09474 2023.

- Liu, Z.; Chu, T.; Zang, Y.; Wei, X.; Dong, X.; Zhang, P.; Liang, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Lin, D. ; others. MMDU: A Multi-Turn Multi-Image Dialog Understanding Benchmark and Instruction-Tuning Dataset for LVLMs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.11833, arXiv:2406.11833 2024.

- Pi, R.; Zhang, J.; Han, T.; Zhang, J.; Pan, R.; Zhang, T. Personalized Visual Instruction Tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.07113, arXiv:2410.07113 2024.

- Zhang, R.; Wei, X.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Tong, C.; Liu, J.; Zhou, A.; Wei, B.; Zhang, S. ; others. Mavis: Mathematical visual instruction tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.08739, arXiv:2407.08739 2024.