Submitted:

25 December 2025

Posted:

26 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

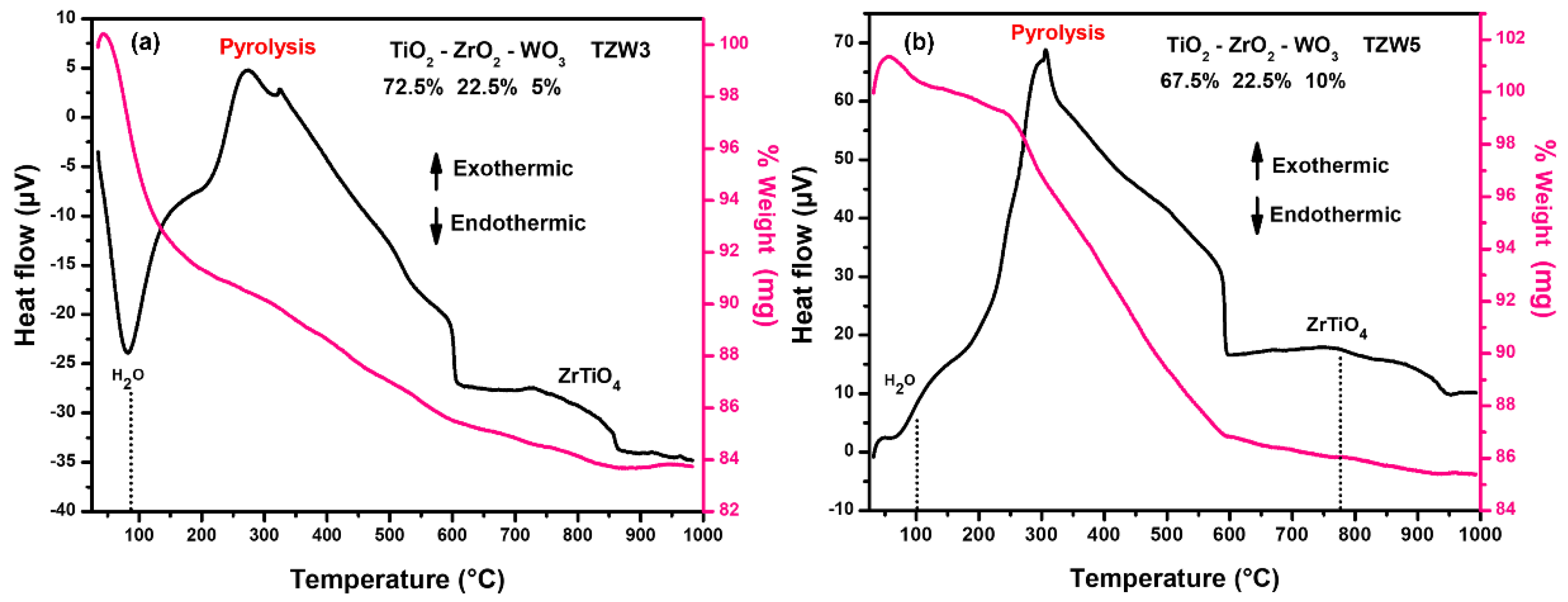

2.1. TGA-DSC Results

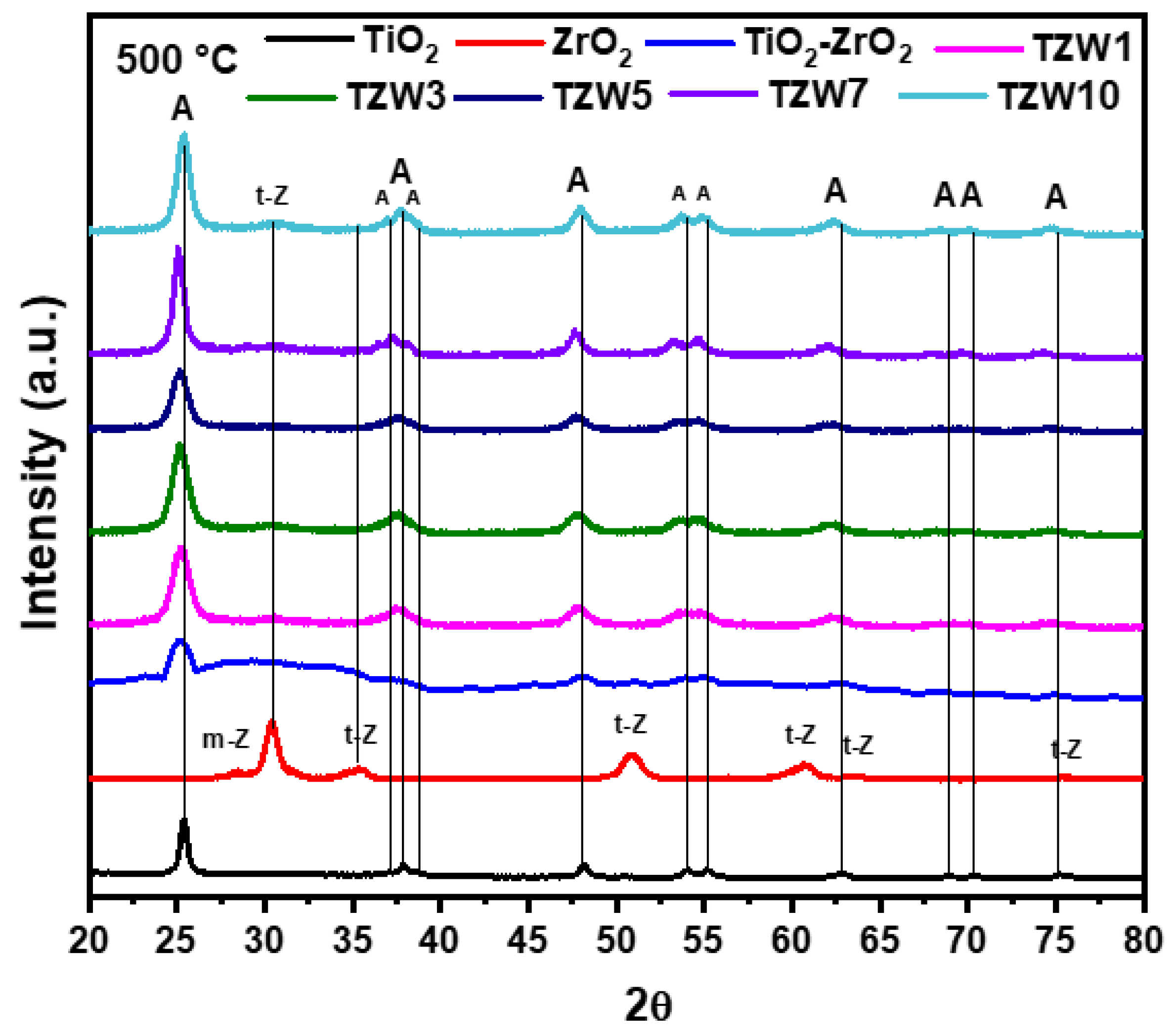

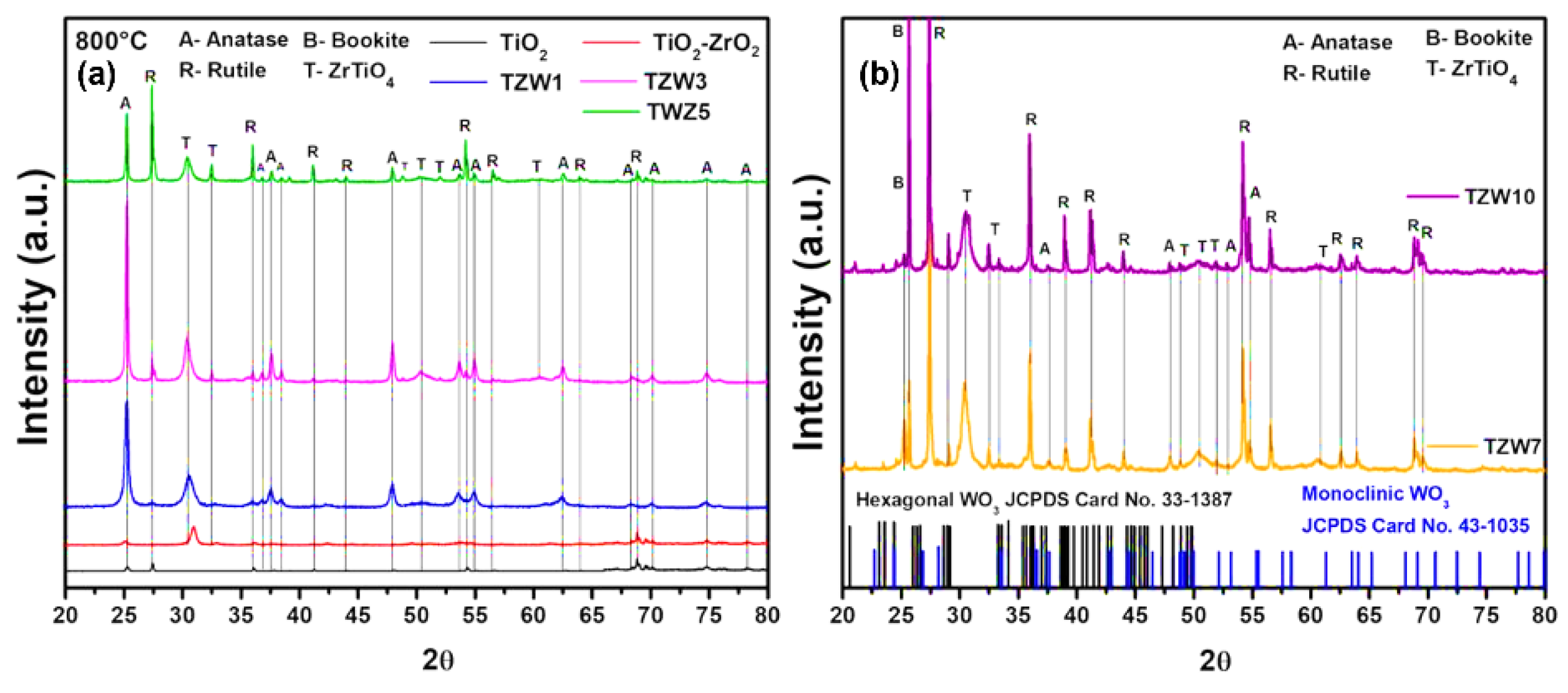

2.2. X-Ray Difracction

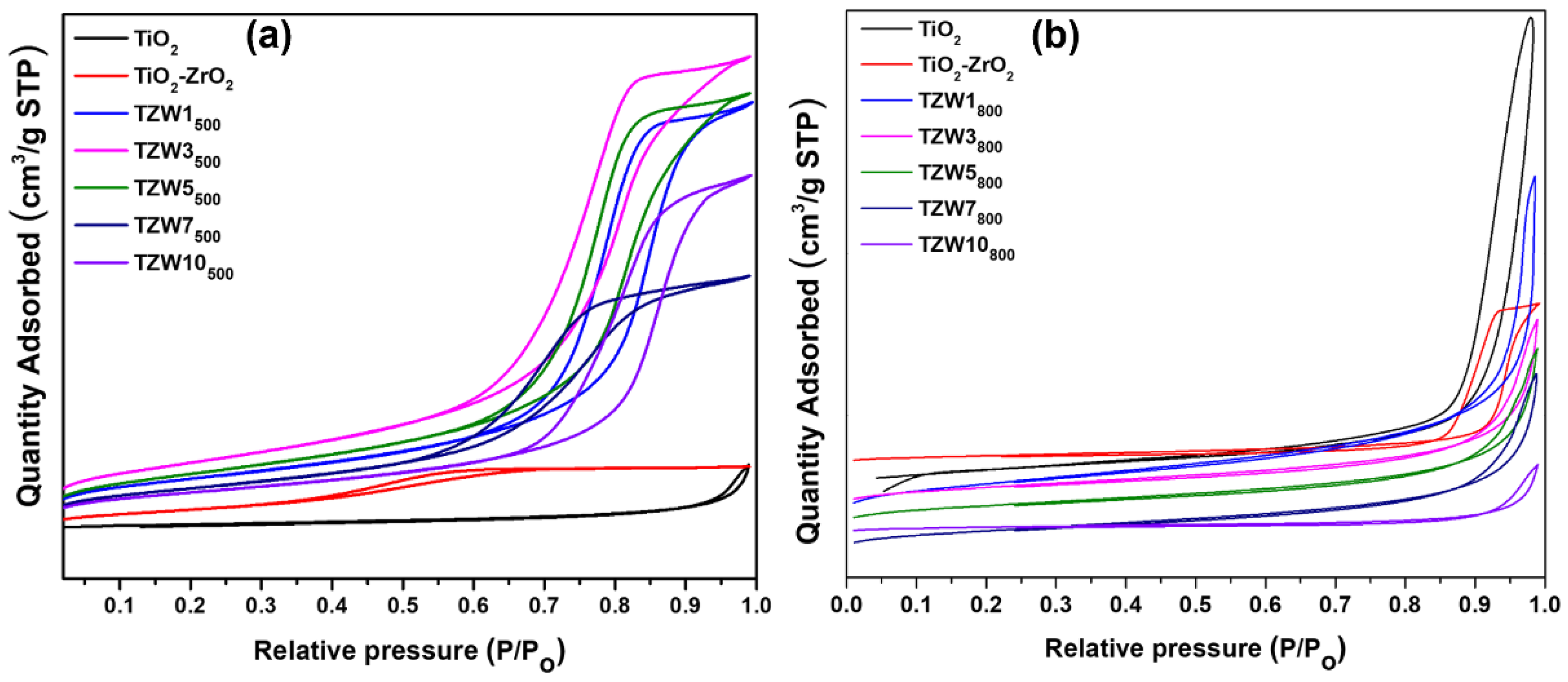

2.3. N2 Physisorption

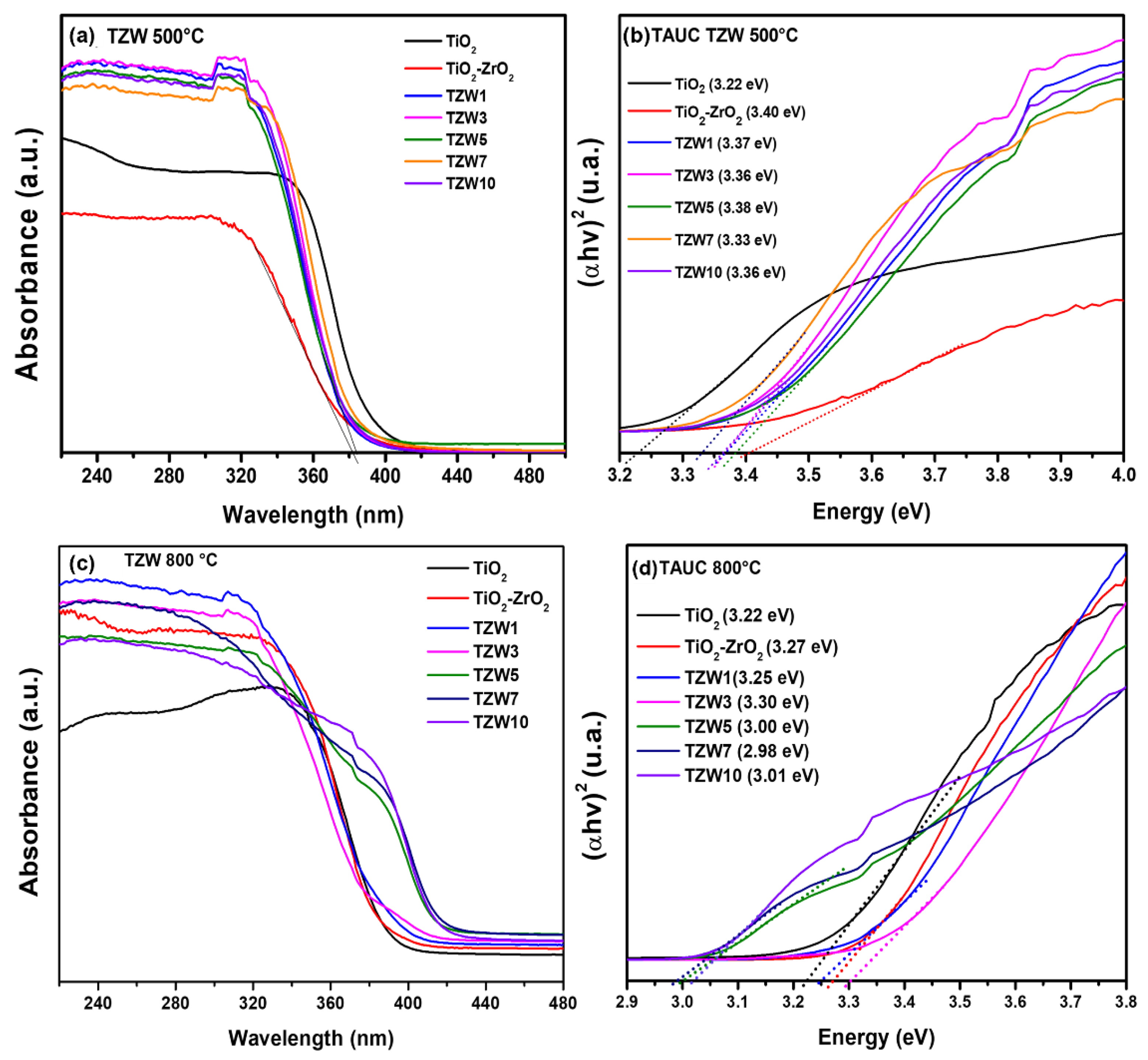

2.4. UV-Vis Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy

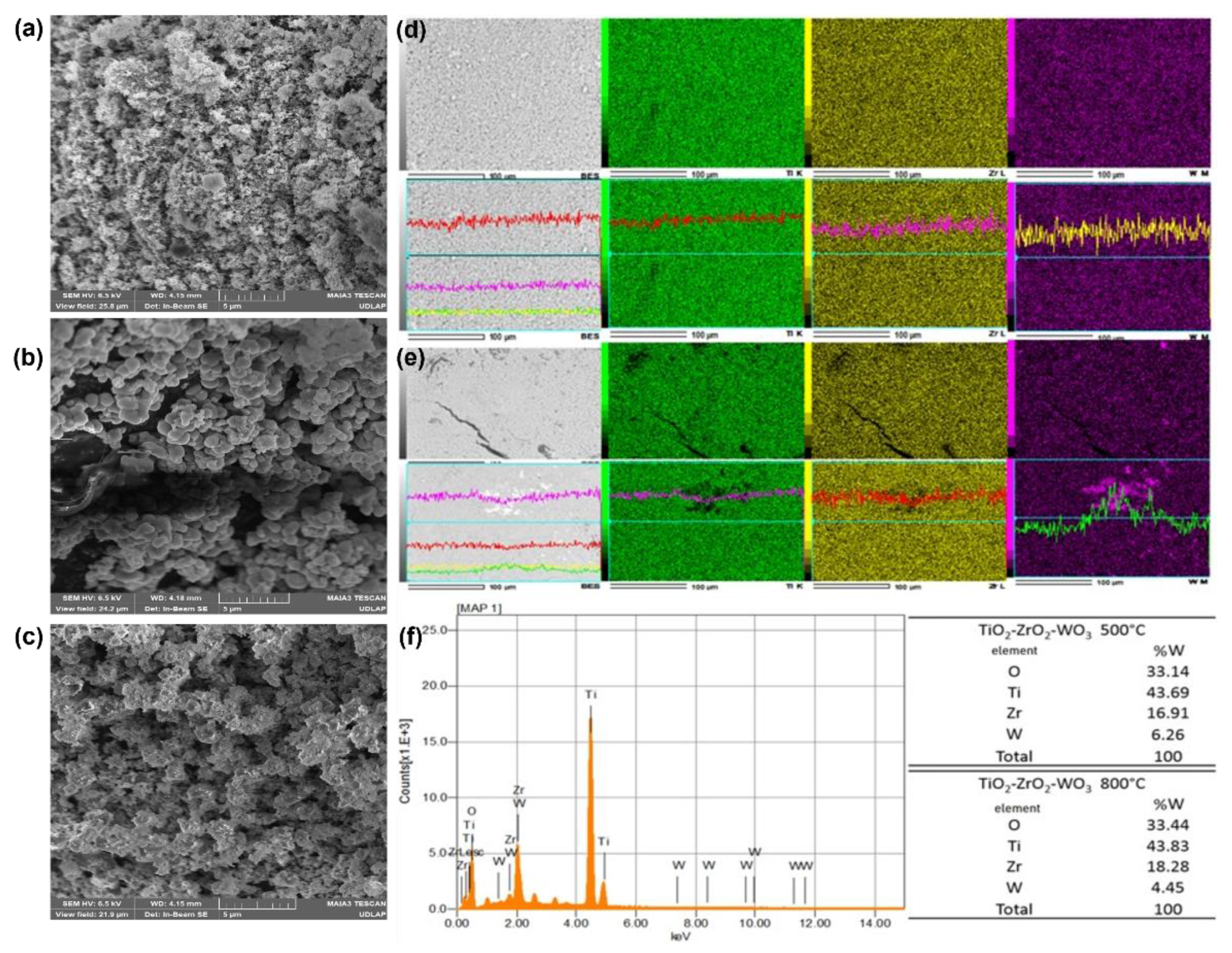

2.5. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)/Energy Dispersive X-Ray Analysis (EDS)

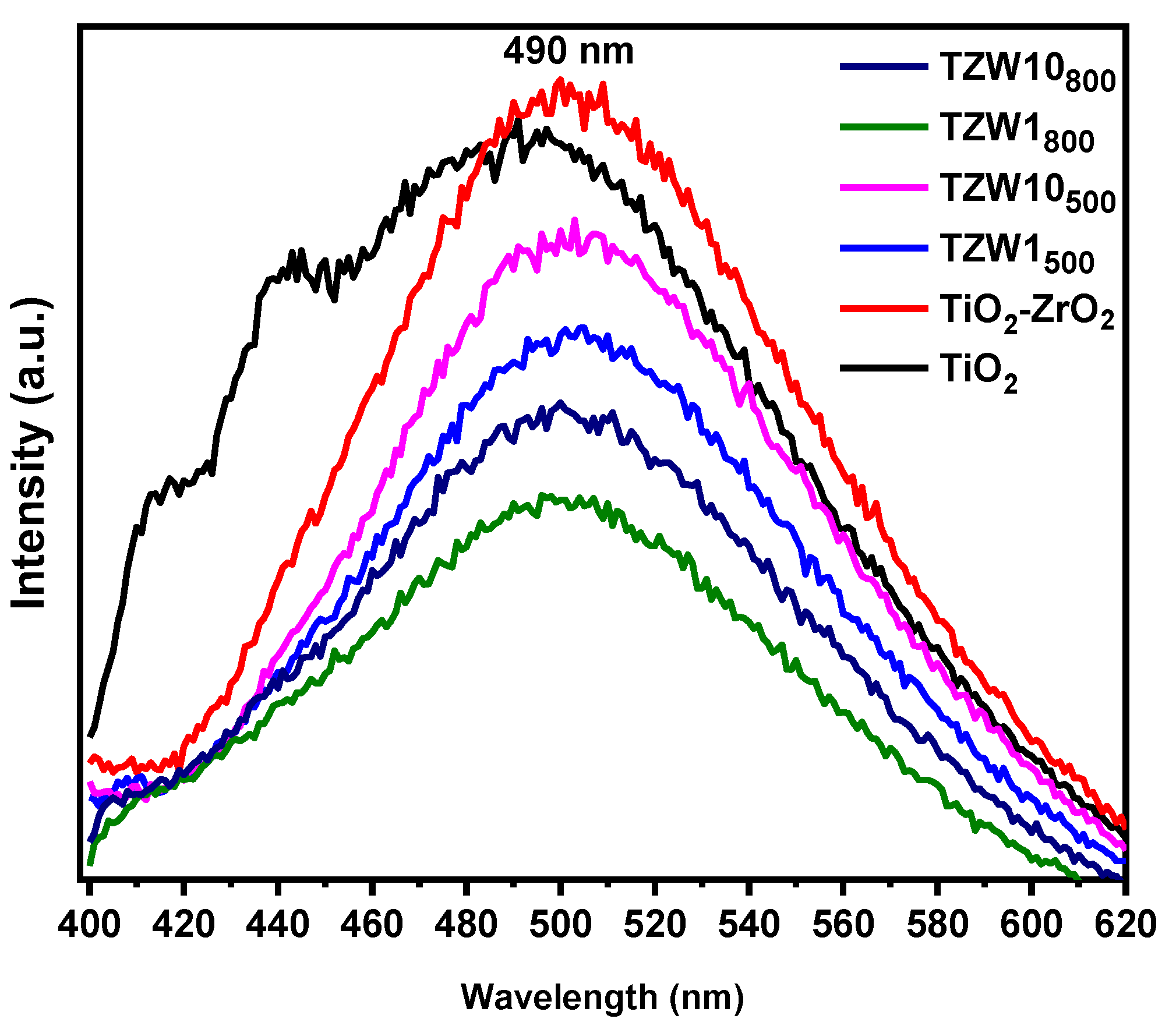

2.6. Photoluminescence Spectroscopy

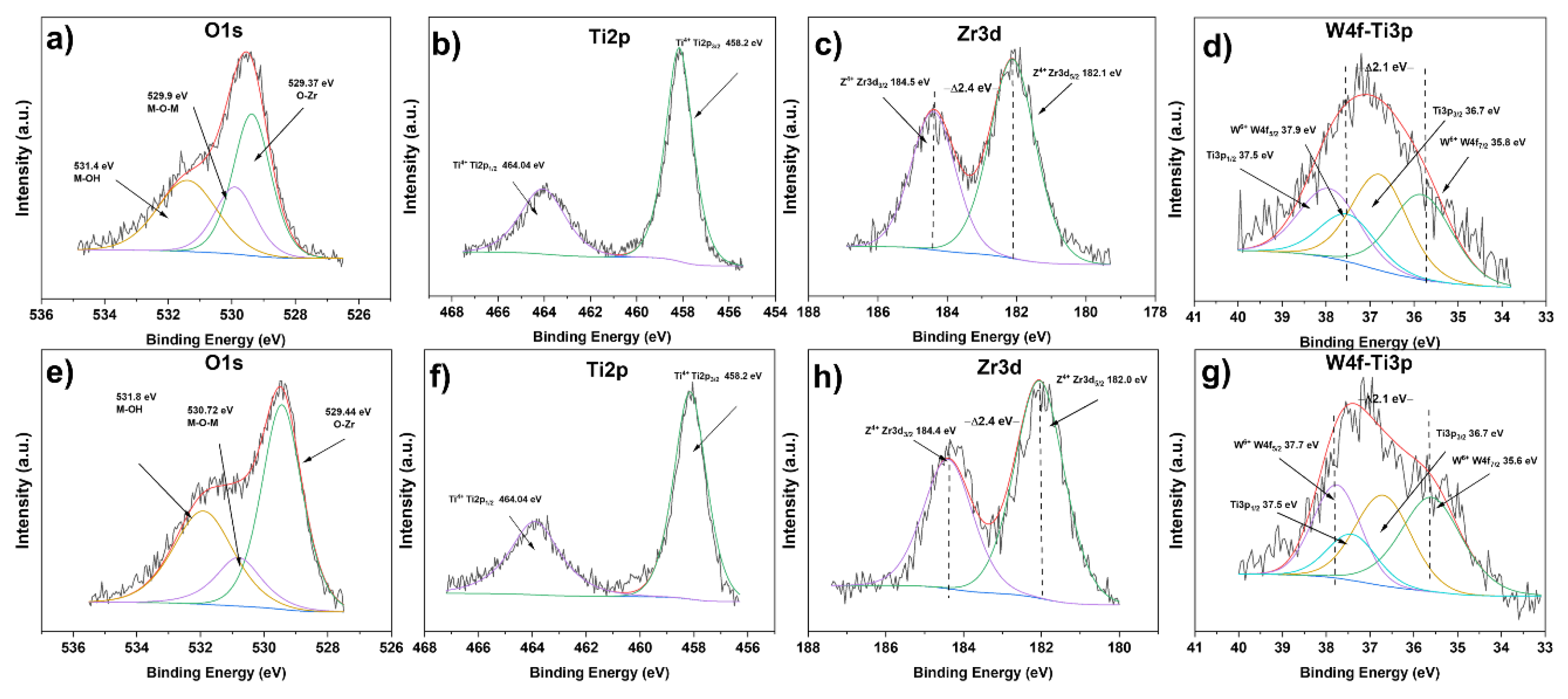

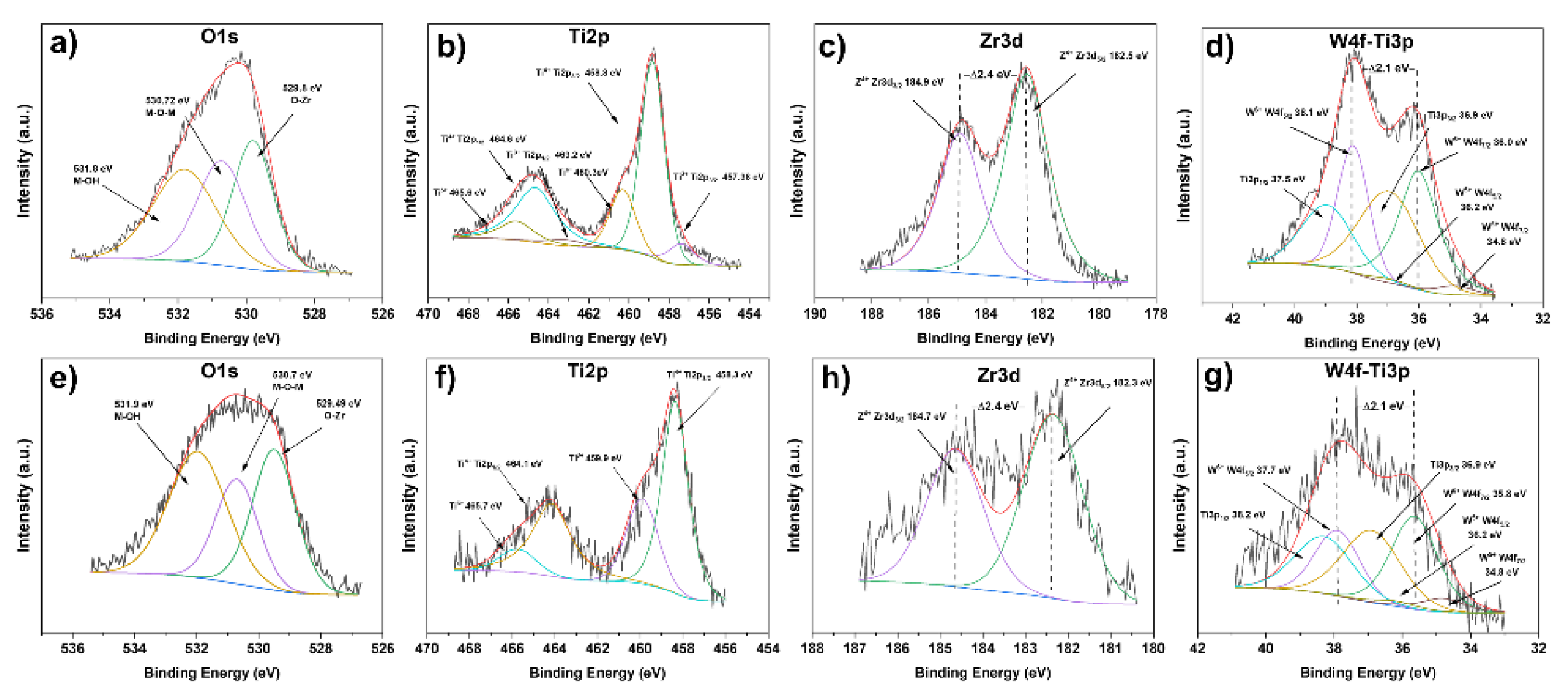

2.7. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

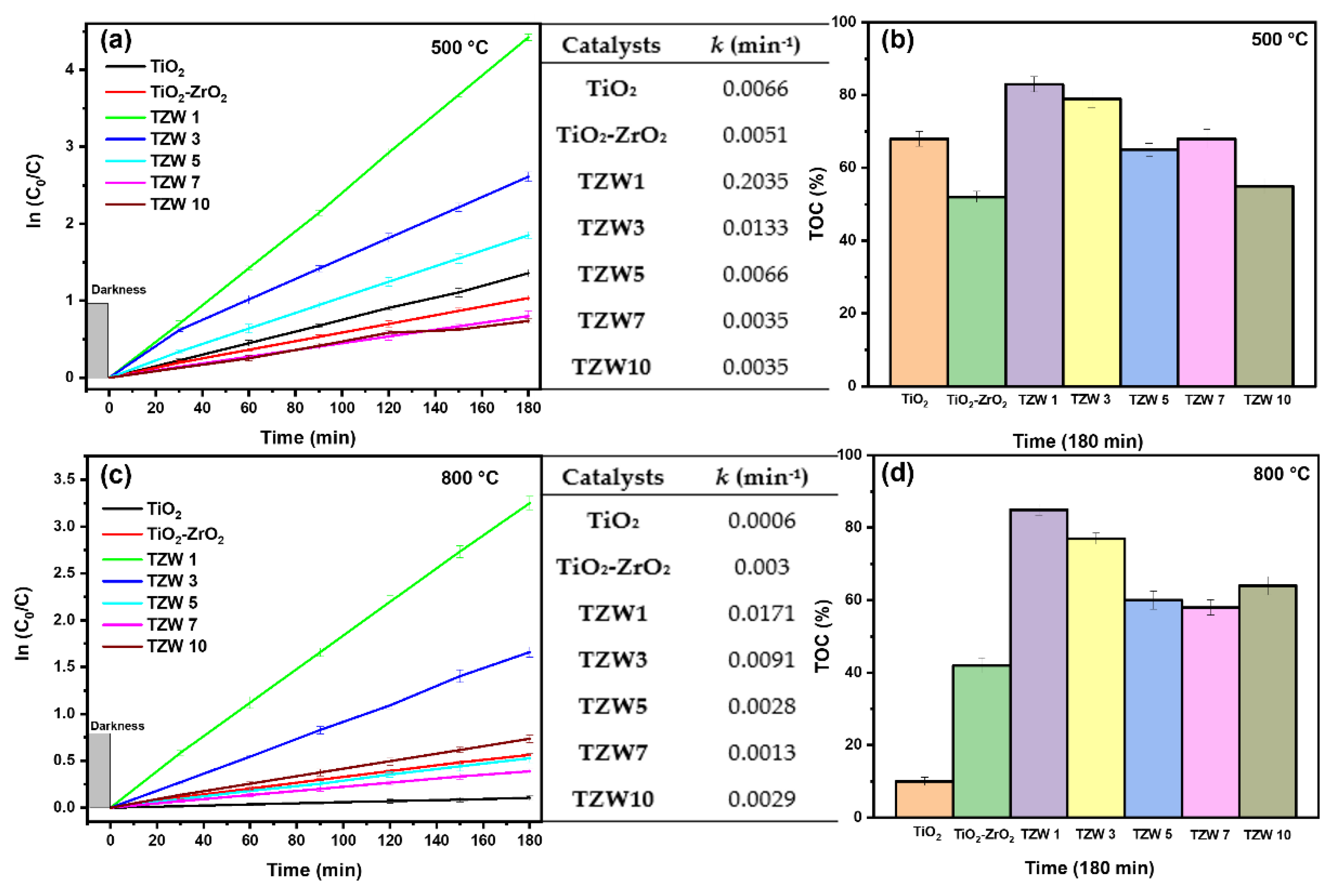

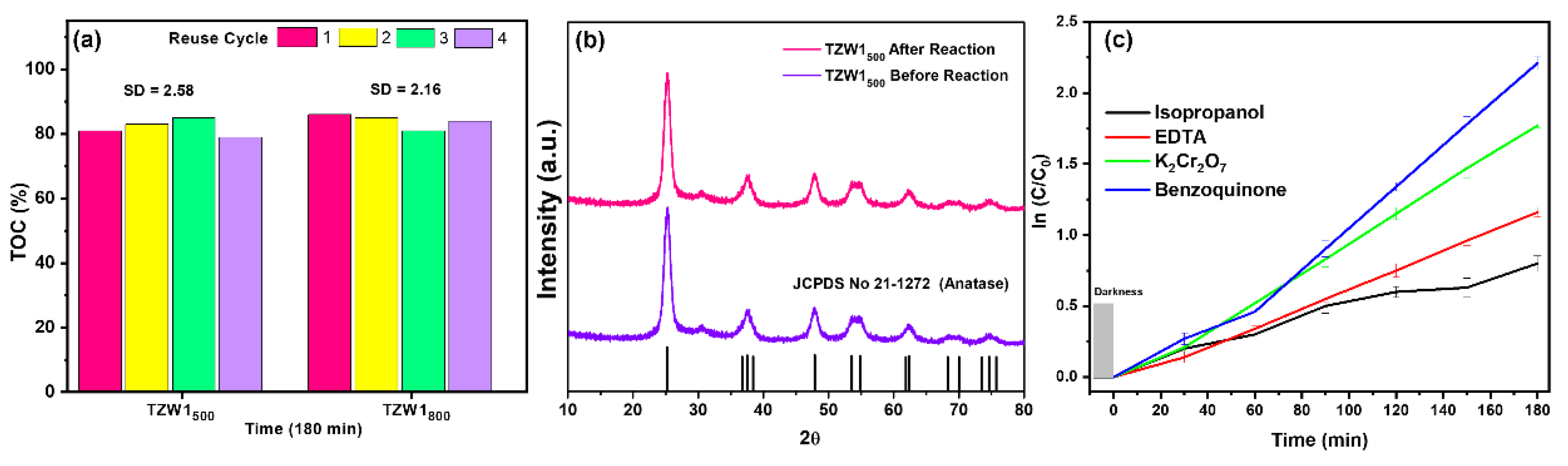

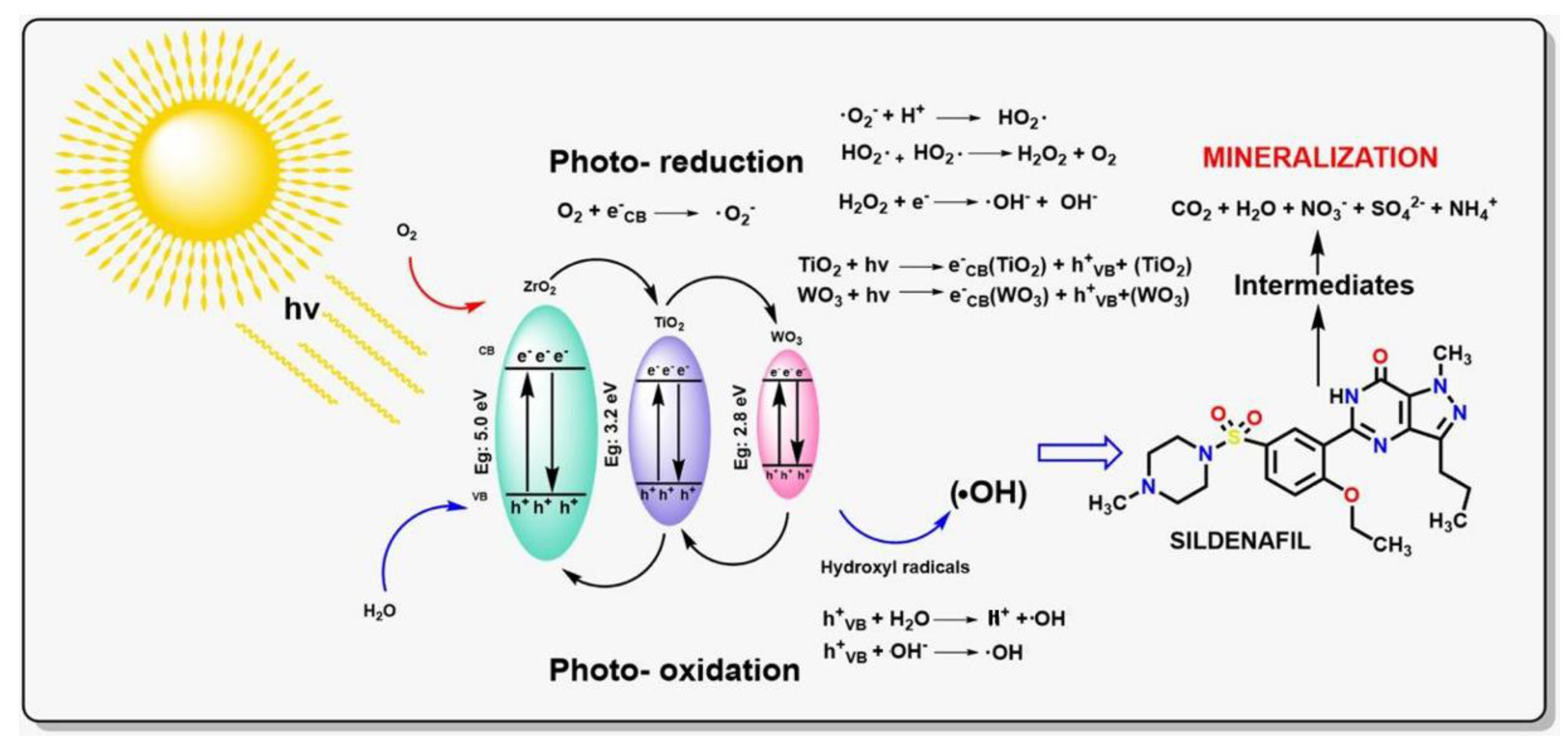

2.8. Photocatalytic Test

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Photocatalyst Synthesis

3.2. Characterization of Catalysts

3.3. Photocatalytic Test

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vinayagam, V.; Shrima, M.; Kumaresan, R.; Narayanan, M.; Sillanpää, M.; Viet N Vo, D.; Kushwaha, O.S.; Jenis, P.; Potdar, P.; Gadiya, S. Sustainable Adsorbents for the Removal of Pharmaceuticals from Wastewater: A Review. Chemosphere 2022, 300, 134597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küster, A.; Adler, N. Pharmaceuticals in the Environment: Scientific Evidence of Risks and Its Regulation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, X.-T.; Zhang, P.-Y.; Liu, S.-Y.; Lin, J.-G.; Tan, D.-Q.; Wang, D.-G. Assessment of Correlations between Sildenafil Use and Comorbidities and Lifestyle Factors Using Wastewater-Based Epidemiology. Water Res. 2022, 218, 118446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, L.P.; Becker-Krail, D.B.; Cory, W.C. Persistent Phototransformation Products of Vardenafil (Levitra®) and Sildenafil (Viagra®). Chemosphere 2015, 134, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causanilles, A.; Rojas Cantillano, D.; Emke, E.; Bade, R.; Baz-Lomba, J.A.; Castiglioni, S.; Castrignanò, E.; Gracia-Lor, E.; Hernández, F.; Kasprzyk-Hordern, B.; et al. Comparison of Phosphodiesterase Type V Inhibitors Use in Eight European Cities through Analysis of Urban Wastewater. Environ. Int. 2018, 115, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorn, P.; Pérez, S.; Aceña, J.; Gardinali, P.; Abad, J.L.; Barceló, D. Identification of Phototransformation Products of Sildenafil (Viagra) and Its N-demethylated Human Metabolite under Simulated Sunlight. J. Mass Spectrom. 2012, 47, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrile, M.G.; Ciucio, M.M.; Demarchi, L.M.; Bono, V.M.; Fiasconaro, M.L.; Lovato, M.E. Degradation and Mineralization of the Emerging Pharmaceutical Pollutant Sildenafil by Ozone and UV Radiation Using Response Surface Methodology. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 23868–23886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Zhang, X.; Feng, W. Enhanced Ultrasound-Assisted Pore-Adjustable Spherical Imma-Fe3O4 Catalytic-Activated Piezoelectric Fenton Reaction for PDE-5i Degradation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Jia, Z.; Liu, X.; Cheng, J. A Novel 1T-2H MoS2/NaBi(MoO4)2 Alternating-Phase Piezoelectric Composites for High-Efficient Ultrasound-Drived Piezoelectric Catalytic Removal of Sildenafil. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 179, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizzamia, A.R.; Tesoro, C.; Bianco, G.; Bufo, S.A.; Ciriello, R.; Brienza, M.; Scrano, L.; Lelario, F. Efficient Photooxidation Processes for the Removal of Sildenafil from Aqueous Environments: A Comparative Study. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 9, 100708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K.; Irie, H.; Fujishima, A. TiO2 Photocatalysis: A Historical Overview and Future Prospects. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 44, 8269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitiyanan, A.; Ngamsinlapasathian, S.; Pavasupree, S.; Yoshikawa, S. The Preparation and Characterization of Nanostructured TiO2–ZrO2 Mixed Oxide Electrode for Efficient Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. J. Solid State Chem. 2005, 178, 1044–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, M.H.; Mehrabani-Zeinabad, A. Photocatalytic Activity of ZrO2/TiO2/Fe3O4 Ternary Nanocomposite for the Degradation of Naproxen: Characterization and Optimization Using Response Surface Methodology. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, S.; Lv, L.; Wang, M.; Zhang, W.; Pan, B. A Thermally Stable Mesoporous ZrO2–CeO2–TiO2 Visible Light Photocatalyst. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 229, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.-L.; Xiong, B.-Y.; Li, J.-L.; Li, Y.-T.; Zhou, Y.-L.; Yang, A.-S.; Zhang, Q.-P. Constructing WO3/TiO2 Heterojunction with Solvothermal-Sintering for Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity under Visible Light Irradiation. Solid State Sci. 2022, 131, 106963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Hao, X.; Sun, X.; Du, P.; Liu, W.; Fu, J. Highly Active WO3@anatase-SiO2 Aerogel for Solar-Light-Driven Phenanthrene Degradation: Mechanism Insight and Toxicity Assessment. Water Res. 2019, 162, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navio, J.A.; Colón, G.; Herrmann, J.M. Photoconductive and Photocatalytic Properties of ZrTiO4. Comparison with the Parent Oxides TiO2 and ZrO2. J. Photochem. Photobiol. Chem. 1997, 108, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Q.; Zhang, L.; Liu, C.; Li, X.; Xu, C.; Hou, X. Boosting Photogenerated Carriers for Organic Pollutant Degradation via In-Situ Constructing Atom-to-Atom TiO2/ZrTiO4 Heterointerface. Ceramics International 2021, 47, 33298–33308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazaeli, R.; Aliyan, H.; Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh, A.; Richeson, D. Investigation of the Synergistic Photocatalytic Activity of a Ternary ZrTiO4/TiO2/Mn3O4 (ZTM) Nanocomposite in a Typical Water Treatment Process. Surfaces and Interfaces 2024, 52, 104877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhachanamoorthi, N.; Oviya, K.; Sugumaran, S.; Suresh, P.; Parthibavarman, M.; Jeshaa Dharshini, K.; Aishwarya, M. Effective Move of Polypyrrole/TiO2 Hybrid Nanocomposites on Removal of Methylene Blue Dye by Photocatalytic Activity. Chem. Phys. Impact 2024, 9, 100723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, B.M.; Khan, A. Recent Advances on TiO2 -ZrO2 Mixed Oxides as Catalysts and Catalyst Supports. Catal. Rev. 2005, 47, 257–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limón-Rocha, I.; Marizcal-Barba, A.; Guzmán-González, C.A.; Anaya-Esparza, L.M.; Ghotekar, S.; González-Vargas, O.A.; Pérez-Larios, A. Co, Cu, Fe, and Ni Deposited over TiO2 and Their Photocatalytic Activity in the Degradation of 2,4-Dichlorophenol and 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid. inorganics 2022, 10, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerachamy, S.; Rajagopal, S. Microstructural Analysis of Terbium Doped Zirconia and Its Biological Studies. Condens. Matter 2022, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manrı́quez, M.E.; López, T.; Gómez, R.; Navarrete, J. Preparation of TiO2–ZrO2 Mixed Oxides with Controlled Acid–Basic Properties. J. Mol. Catal. Chem. 2004, 220, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silahua-Pavón, A.A.; Espinosa-González, C.G.; Ortiz-Chi, F.; Pacheco-Sosa, J.G.; Pérez-Vidal, H.; Arévalo-Pérez, J.C.; Godavarthi, S.; Torres-Torres, J.G. Production of 5-HMF from Glucose Using TiO2-ZrO2 Catalysts: Effect of the Sol-Gel Synthesis Additive. Catal. Commun. 2019, 129, 105723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayoufi, A.; Faouzi Nsib, M.; Houas, A. Doping Level Effect on Visible-Light Irradiation W-Doped TiO2–Anatase Photocatalysts for Congo Red Photodegradation. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2014, 17, 818–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-S.; Yang, J.-H.; Balaji, S.; Cho, H.-J.; Kim, M.-K.; Kang, D.-U.; Djaoued, Y.; Kwon, Y.-U. Hydrothermal Synthesis of Anatase Nanocrystals with Lattice and Surface Doping Tungsten Species. CrystEngComm 2009, 11, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Cruz, D.; Arévalo, J.C.; Torres, G.; Margulis, R.G.B.; Ornelas, C.; Aguilar-Elguézabal, A. TiO2 Doped with Sm3+ by Sol–Gel: Synthesis, Characterization and Photocatalytic Activity of Diuron under Solar Light. Catal. Today 2011, 166, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.; Solomon, S.; Thomas, J.K.; John, A. Characterizations and Electrical Properties of ZrTiO4 Ceramic. Mater. Res. Bull. 2012, 47, 3141–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arévalo-Pérez, J.C.; Cruz-Romero, D.D.L.; Cordero-García, A.; Lobato-García, C.E.; Aguilar-Elguezabal, A.; Torres-Torres, J.G. Photodegradation of 17 α-Methyltestosterone Using TiO2 -Gd3+ and TiO2-Sm3+ Photocatalysts and Simulated Solar Radiation as an Activation Source. Chemosphere 2020, 249, 126497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palliyaguru, L.; Kulathunga, U.S.; Jayarathna, L.I.; Jayaweera, C.D.; Jayaweera, P.M. A Simple and Novel Synthetic Route to Prepare Anatase TiO2 Nanopowders from Natural Ilmenite via the H3PO4/NH3 Process. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2020, 27, 846–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, Q.; Matsushita, T.; Sun, S.; Tatsuoka, H. Growth of Brookite TiO2 Nanorods by Thermal Oxidation of Ti Metal in Air. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2024, 35, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badli, N.A.; Ali, R.; Wan Abu Bakar, W.A.; Yuliati, L. Role of Heterojunction ZrTiO4/ZrTi2O6/TiO2 Photocatalyst towards the Degradation of Paraquat Dichloride and Optimization Study by Box–Behnken Design. Arab. J. Chem. 2017, 10, 935–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of Gases, with Special Reference to the Evaluation of Surface Area and Pore Size Distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Chen, G.; Yu, Y.; Hao, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, Y. Facile Approach to Synthesize G-PAN/g-C3N4 Composites with Enhanced Photocatalytic H2 Evolution Activity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 7171–7179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; He, W.; Dong, X.; Jiang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Dong, F. In Situ DRIFT Investigation on the Photocatalytic NO Oxidation Mechanism with Thermally Exfoliated Porous G-C3 N4 Nanosheets. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 19280–19287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, H.; Gaborieau, M.; Huang, J.; Jiang, Y. Glucose Conversion to 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural on Zirconia: Tuning Surface Sites by Calcination Temperatures. SISydney Catal Symp. 2020, 351, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.; Alavi, S.M.; Larimi, A. UV–Vis Light Responsive Bi2WO6 Nanosheet/TiO2 Nanobelt Heterojunction Photo-Catalyst for CO2 Reduction. Catal. Commun. 2023, 179, 106681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Ie, I.-R.; Yuan, C.-S.; Hung, C.-H.; Chen, W.-H. Removal of Elemental Mercury by TiO2 doped with WO3 and V2O5 for Their Photo- and Thermo-Catalytic Removal Mechanisms. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 5839–5852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Shao, Q.; Zhao, J.; Pan, D.; Dong, M.; Jia, C.; Ding, T.; Wu, T.; Guo, Z. Microwave Solvothermal Carboxymethyl Chitosan Templated Synthesis of TiO2/ZrO2 Composites toward Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Rhodamine B. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 541, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Alejandre, A.; Ramírez, J.; Val, I.J.; Peñuelas-Galaz, M.; Sánchez-Neri, P.; Torres-Mancera, P. Activity of NiW Catalysts Supported on TiO2-Al2O3 Mixed Oxides: Effect of Ti Incorporation Method on the HDS of 4,6-DMDBT. Sel. Contrib. XIX Ibero Am. Catal. Symp. 2005, 107–108, 879–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerosa, M.; Bottani, C.E.; Caramella, L.; Onida, G.; Di Valentin, C.; Pacchioni, G. Defect Calculations in Semiconductors through a Dielectric-Dependent Hybrid DFT Functional: The Case of Oxygen Vacancies in Metal Oxides. J. Chem. Phys. 2015, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuffrida, F.; Calcagno, L.; Pezzotti Escobar, G.; Zimbone, M. Photocatalytic Efficiency of TiO2/Fe2O3 and TiO2/WO3 Nanocomposites. Crystals 2023, 13, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Kang, M. Hydrogen Production from Methanol/Water Decomposition in a Liquid Photosystem Using the Anatase Structure of Cu Loaded TiO2. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2007, 32, 3841–3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oanh, L.M.; Do, D.B.; Hung, N.M.; Thang, D.V.; Phuong, D.T.; Ha, D.T.; Van Minh, N. Formation of Crystal Structure of Zirconium Titanate ZrTiO4 Powders Prepared by Sol–Gel Method. J. Electron. Mater. 2016, 45, 2553–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Araque, D.; Ramírez-Ortega, D.; Acevedo-Peña, P.; Zanella, R.; Gómez, R. Photocatalytic Degradation of 2,4-Dichlorophenol on ZrO2–TiO2: Influence of Crystal Size, Surface Area, and Energetic States. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2020, 31, 3332–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraswati, T.E.; Nandika, A.O.; Andhika, I.F.; Patiha; Purnawan, C.; Wahyuningsih, S.; Rahardjo, S.B. Fabrication of TiO2 /Carbon Photocatalyst Using Submerged DC Arc Discharged in Ethanol/Acetic Acid Medium. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 202, 012058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambur, A.; Pozan, G.S.; Boz, I. Preparation, Characterization and Photocatalytic Activity of TiO2–ZrO2 Binary Oxide Nanoparticles. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2012, 115–116, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singupilla, S.S.; Tirukkovalluri, S.R.; Gorli, D.; Nayak, S.R.; Raffiunnisa; Jikamo, S.C.; Kadiyala, N.R.; Genji, J. Aloe Vera Gel-Mediated Sol-Gel Synthesis of Ce-Ni Co-Doped TiO2 Nanomaterials for Efficient Visible-Light-Driven Binary Dye Degradation and Antimicrobial Applications. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2025, 115, 509–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G.; Raza, W.; Tahir, M.B. Green Synthesis of TiO2 Nanoparticle Using Cinnamon Powder Extract and the Study of Optical Properties. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2020, 30, 1425–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.P.; Pandikumar, A.; Lim, H.N.; Ramaraj, R.; Huang, N.M. Boosting Photovoltaic Performance of Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells Using Silver Nanoparticle-Decorated N,S-Co-Doped-TiO2 Photoanode. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebeca Sofiya Joice, M.; Dev, P.R.; Iyyappan, E.; Manovah David, T.; Thangavel, N.; Neppolian, B.; Wilson, P. Construction of Novel Step-Scheme TiO2-WO3 Nanostructured Heterojunction towards Morphology-Driven Enhancement of Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. JCIS Open 2025, 18, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldirham, S.H.; Helal, A.; Shkir, M.; Sayed, M.A.; Ali, A.M. Enhancement Study of the Photoactivity of TiO2 Photocatalysts during the Increase of the WO3 Ratio in the Presence of Ag Metal. Catalysts 2024, 14, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Lai, C.; Hamid, S. One-Step Formation of WO3-Loaded TiO2 Nanotubes Composite Film for High Photocatalytic Performance. Materials 2015, 8, 2139–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, A.; Pan, G.-H.; Wu, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Wu, H.; Zhang, J. Microstructure and Photoluminescence of ZrTiO4:Eu3+ Phosphors: Host-Sensitized Energy Transfer and Optical Thermometry. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.B.; Zhong, X.X.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cvelbar, U.; Ostrikov, K. Single-Step Synthesis of TiO2/WO3−x Hybrid Nanomaterials in Ethanoic Acid: Structure and Photoluminescence Properties. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 562, 150180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, T.A.T.; Gerónimo, E.S.; Torres, J.G.T.; Del Angel Montes, G.A.; Vázquez, I.R.; García, A.C.; Uribe, A.C.; Pavon, A.A.S.; Pérez, J.C.A. Photocatalytic Oxidation of Pesticides with TiO2-CeO2 Thin Films Using Sunlight. Catalysts 2025, 15, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, X.; Yang, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X. Performance and Mechanism of In Situ Prepared NF@CoMnNi-LDH Composites to Activate PMS for Degradation of Enrofloxacin in Water. Water 2024, 17, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Lu, Q.; Lv, L.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Deng, Z.; Lou, Z.; Hou, Y.; Teng, F. Ligand-Free Rutile and Anatase TiO2 Nanocrystals as Electron Extraction Layers for High Performance Inverted Polymer Solar Cells. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 20084–20092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Iturriaga, J.; Hernández-Pichardo, M.L.; Montoya De La Fuente, J.A.; Del Angel, P.; Gomora-Herrera, D.; Palacios-González, E.; Lartundo, L.; Moreno-Ruíz, L.A. Hydroisomerization of N-Hexane over Pt/WOx-ZrO2-TiO2 Catalysts. Catal. Today 2021, 360, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Zhao, B.; Niu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Liu, L.; Dong, J.; Tang, M.; Li, X. Hydrogenation of Naphthalene to Decalin Catalyzed by Pt Supported on WO3 of Different Crystallinity at Low Temperature. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2021, 49, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Li, R.; Xu, Q. Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity of Se-Doped TiO2 under Visible Light Irradiation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baithy, M.; Mukherjee, D.; Rangaswamy, A.; Reddy, B.M. Structure–Activity Relationships of WOx-Promoted TiO2–ZrO2 Solid Acid Catalyst for Acetalization and Ketalization of Glycerol towards Biofuel Additives. Catal. Lett. 2022, 152, 1428–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Gan, W.; Qiu, Z.; Zhan, X.; Qiang, T.; Li, J. Preparation of Heterostructured WO3/TiO2 Catalysts from Wood Fibers and Its Versatile Photodegradation Abilities. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Patel, R.L.; Liang, X. Significant Improvement in TiO2 Photocatalytic Activity through Controllable ZrO2 Deposition. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 25829–25834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanyan, L.; Kurniawan, T.A.; Ying, Z.; Albadarin, A.B.; Walker, G. Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Acetaminophen from Wastewater Using WO3/TiO2/SiO2 Composite under UV–VIS Irradiation. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 243, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, J.H.F.; Lee, K.M.; Pang, Y.L.; Abdullah, B.; Juan, J.C.; Leo, B.F.; Lai, C.W. Photodegradation Assessment of RB5 Dye by Utilizing WO3/TiO2 Nanocomposite: A Cytotoxicity Study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 22372–22390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, J.H.F.; Lai, C.W.; Leo, B.F.; Juan, J.C.; Johan, M.R. Advanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Acetaminophen Using Cu2O/WO3/TiO2 Ternary Composite under Solar Irradiation. Catal. Commun. 2022, 163, 106396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaiano, V.; Sacco, O.; Matarangolo, M. Photocatalytic Degradation of Paracetamol under UV Irradiation Using TiO2-Graphite Composites. Graph. Mater. Photoelectrocatalysis 2018, 315, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, J.; Xing, Z.; Yin, J.; Li, Z.; Tan, S.; Li, M.; Jiang, J.; Zhu, Q.; Zhou, W. Ti3+ Self-Doped Rutile/Anatase/TiO2(B) Mixed-Crystal Tri-Phase Heterojunctions as Effective Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalysts. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 2568–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdova-Pérez, G.E.; Cortez-Elizalde, J.; Silahua-Pavón, A.A.; Cervantes-Uribe, A.; Arévalo-Pérez, J.C.; Cordero-Garcia, A.; De Los Monteros, A.E.E.; Espinosa-González, C.G.; Godavarthi, S.; Ortiz-Chi, F.; et al. γ-Valerolactone Production from Levulinic Acid Hydrogenation Using Ni Supported Nanoparticles: Influence of Tungsten Loading and pH of Synthesis. Nanomaterials 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boppella, R.; Basak, P.; Manorama, S.V. Viable Method for the Synthesis of Biphasic TiO2 Nanocrystals with Tunable Phase Composition and Enabled Visible-Light Photocatalytic Performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 1239–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reguero-Márquez, G.A.; Lunagómez-Rocha, M.A.; Cervantes-Uribe, A.; del Angel, G.; Rangel, I.; Torres-Torres, J.G.; González, F.; Godavarthi, S.; Arevalo-Perez, J.C.; Espinosa de los Monteros, A.E.; et al. Photodegradation of 2,4-D (Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid) with Rh/TiO2; Comparative Study with Other Noble Metals (Ru, Pt, and Au). RSC Adv 2022, 12, 25711–25721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, V.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, N.; Sillanpää, M.; Makgwane, P.R.; Ahmaruzzaman, Md.; Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A.; Rani, M.; Chinnamuthu, P. TiO2-CeO2 Assisted Heterostructures for Photocatalytic Mitigation of Environmental Pollutants: A Comprehensive Study on Band Gap Engineering and Mechanistic Aspects. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023, 151, 110564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, N.; Lai, C.W.; Johan, M.R.B.; Mousavi, S.M.; Badruddin, I.A.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, G.; Gapsari, F. Progress in Photocatalytic Degradation of Industrial Organic Dye by Utilising the Silver Doped Titanium Dioxide Nanocomposite. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, F.V.B.; Ferreira, A.P.G.; Alarcon, R.T.; Cavalheiro, É.T.G. Studies on the Thermal Behavior of Sildenafil Citrate. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. Open 2024, 3, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Patnaik, R.; Divya, N. A Brief Review on the Synthesis of TiO2 Thin Films and Its Application in Dye Degradation. Adv. Chem. Eng. Sci. ACES 2023, 72, 2749–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Catalyst | Anatase (TiO2) (101) |

Rutile (TiO2) (110) |

Orthorhombic (ZrTiO4) (111) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2 | 14.89 | - | - |

| TiO2-ZrO2 500 | 9.42 | ||

| TZW1500 | 10.20 | - | - |

| TZW3500 | 11.08 | - | - |

| TZW5500 | 10.92 | - | - |

| TZW7500 | 14.84 | - | - |

| TZW10500 | 12.03 | - | - |

| TiO2-ZrO2 800 | 20.15 | 8.50 | |

| TZW1800 | 23.76 | - | 10.01 |

| TZW3800 | 37.80 | 53.16 | 15.93 |

| TZW5800 | 48.3 | 54.69 | 12.64 |

| TZW7800 | - | 64.44 | 16.17 |

| TZW10800 | - | 59.90 | 12.42 |

| Catalysts | Ti-Zr-W (%) |

SBET (m2/g) | Pore diameter Dp (nm) | Pore volume Vp (cm3/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2 500 | 100-0-0 | 54 | 8.20 | 0.162 |

| TiO2-ZrO2 500 | 75-25-0 | 216 | 3.48 | 0.260 |

| TZW1500 | 74.25-24.75-1 | 104 | 8.78 | 0.340 |

| TZW3500 | 72.75-24.25-3 | 134 | 7.46 | 0.370 |

| TZW5500 | 72.5-22.5-5 | 114 | 8.12 | 0.350 |

| TZW7500 | 69.75-23.25-7 | 87 | 6.22 | 0.200 |

| TZW10500 | 67.5-22.5-10 | 79 | 9.60 | 0.280 |

| TiO2 800 | 100-0-0 | 5 | 35.07 | 0.175 |

| TiO2-ZrO2 800 | 75-25-0 | 28 | 18.85 | 0.153 |

| TZW1800 | 74.25-24.75-1 | 24 | 11.61 | 0.047 |

| TZW3800 | 72.75-24.25-3 | 16 | 10.75 | 0.026 |

| TZW5800 | 72.5-22.5-5 | 15 | 11.20 | 0.027 |

| TZW7800 | 69.75-23.25-7 | 13 | 11.45 | 0.029 |

| TZW10800 | 67.5-22.5-10 | 5 | 22.84 | 0.008 |

| Catalyst | Oxidation States | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti | Zr | W | O | |||||

| Ti3+ | Ti4+ | Zr4+ | W5+ | W6+ | O-M | M-O-M | M-OH | |

| TZW1500 | - | 100 | 100 | - | 100 | 44.08 | 22.27 | 33.66 |

| TWZ10500 | - | 100 | 100 | - | 100 | 51.40 | 14.52 | 34.08 |

| TZW1800 | 27.98 | 72.02 | 100 | 4.86 | 95.14 | 32.25 | 31.56 | 36.19 |

| TWZ10800 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 11.53 | 88.47 | 34.30 | 24.83 | 40.87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).