Introduction

Paranasal sinus pathologies, including sinusitis, remain one of the most common clinical conditions encountered in primary care, ENT practice, and radiology departments worldwide. Although often considered a routine diagnosis, the underlying anatomical and radiological foundations are far from simple. Understanding the complex anatomy of the paranasal sinuses, along with their embryological development, drainage pathways, anatomical variations, and imaging appearances, is essential for accurate evaluation, preventing complications, and planning appropriate management.

This article revisits the anatomy of the paranasal sinuses, discussing how modern radiology, particularly CT and MRI, plays a crucial role in diagnosing sinusitis and its complications, while highlighting the relevance of common anatomical variations frequently encountered in clinical practice.

Introduction to Paranasal Sinuses

The paranasal sinuses are air-filled cavities located within the skull and facial bones. These include the maxillary, frontal, ethmoidal, and sphenoidal sinuses. Sinuses are lined by pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium, which aids in humidifying inspired air and clearing mucus through coordinated ciliary movement. These spaces also contribute to voice resonance, reduction of skull weight, and protection against facial trauma.

Despite their functional importance, the sinuses are more prone to obstruction, mucosal inflammation, and infection, largely due to their narrow drainage pathways. When these outflow tracts become obstructed, a range of complications, including sinusitis, develops.

Revisiting the Anatomy of the Paranasal Sinuses

Maxillary Sinus

The maxillary sinus is the largest of the paranasal sinuses, pyramidal in configuration, and the most frequently affected sinus in inflammatory disease. It is located within the body of the maxilla, with its medial wall forming the lateral boundary of the nasal cavity and its apex extending laterally into the zygomatic process.

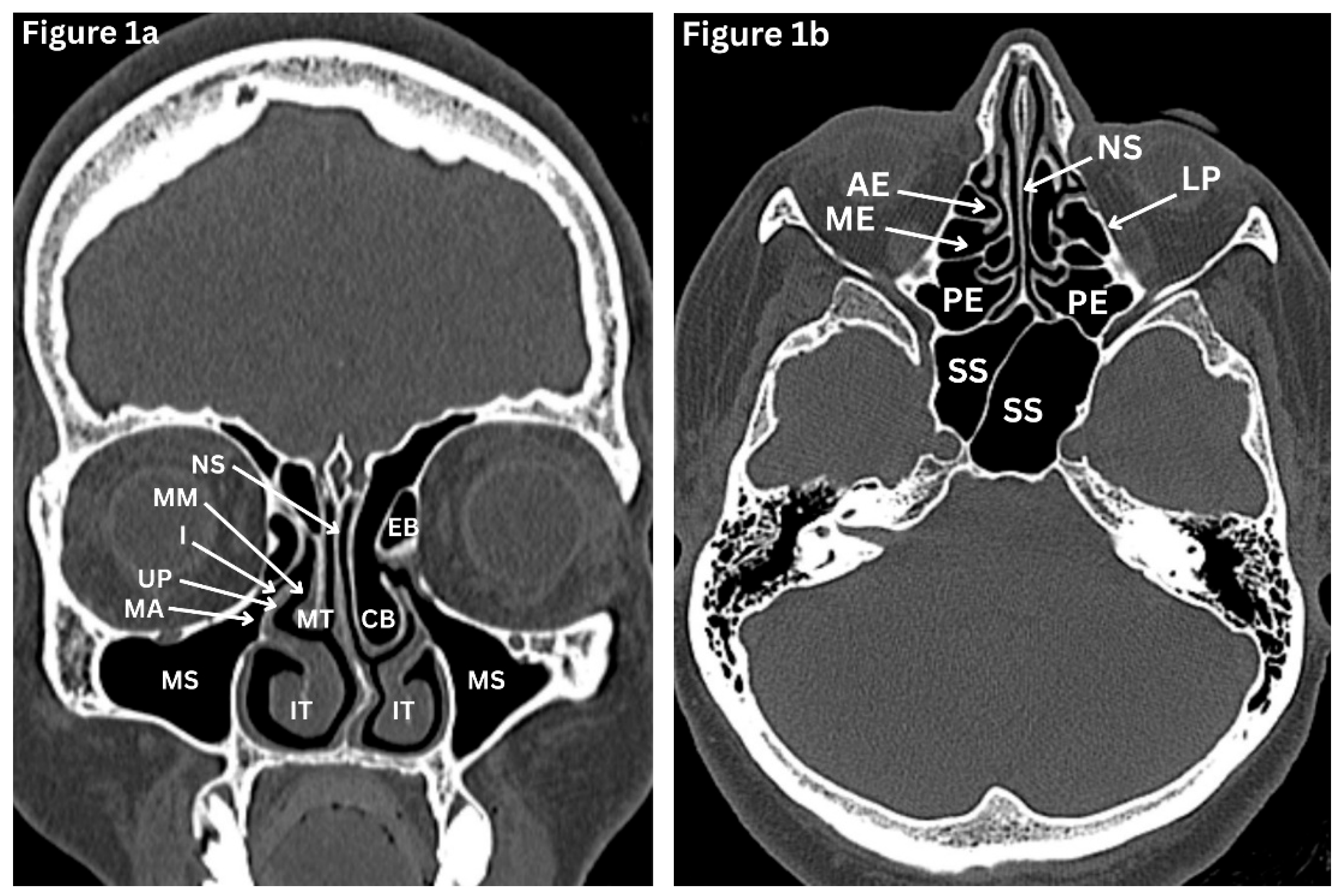

(Figure 1a) Inferiorly, the sinus floor is related to the alveolar part of the maxilla and lies in proximity to the roots of the premolar and molar teeth, with odontogenic communication reported in up to 40% of individuals [

1]. This explains why dental infections may mimic or trigger sinus disease. Superiorly, the roof of the sinus contributes to the orbital floor and contains the infraorbital nerve, together with the superior alveolar branches of the maxillary nerve, which provide sensory innervation to the region. The maxillary sinus ostium is situated on the posterosuperior aspect of the medial wall. It drains into the middle meatus of the lateral nasal wall via the posterior part of the infundibulum. Because of this high, non-dependent position, effective drainage depends on intact mucociliary clearance rather than gravity. This anatomical configuration predisposes to secretion retention and recurrent maxillary sinusitis, particularly when mucosal oedema, anatomical variation, or obstruction of the ostiomeatal complex is present [

1,

2].

Frontal Sinus

The frontal sinuses are unique among the paranasal sinuses in that they are absent from birth and develop later in childhood. They are the most superiorly positioned sinuses and are located within the frontal bone. The frontal sinuses exhibit marked variation in size and symmetry among individuals. Drainage of the sinus occurs via the frontonasal duct into the middle meatus.

(Figure 1c) Sensory innervation is provided by the supraorbital nerve, while vascular supply is derived from branches of the ophthalmic artery. Due of their highly variable anatomy and close proximity to the anterior cranial fossa and the orbit, the frontal sinuses present challenges during surgical intervention and carry an increased risk of intracranial complications in the context of frontal sinusitis [

1,

2].

Ethmoidal Sinuses

The ethmoid labyrinth contains multiple small air cells arranged in anterior, middle, and posterior groups.

(Fiture1a-c) The number of ethmoid air cells varies between individuals, but they typically consist of about seven smaller anterior cells and four larger posterior cells. Their anatomical boundaries are clinically important. The anterior and middle cells drain into the middle meatus, while the posterior cells drain into the superior meatus. The ethmoid sinuses are separated from the orbit by the delicate, paper-thin lamina papyracea, making orbital complications of ethmoiditis potentially risky. Both nerve and blood supply arise from branches of the ophthalmic nerve and artery [

1,

2].

Sphenoid Sinus

Sphenoid sinuses are a pair of sinuses separated by a septum and situated deep within the sphenoid bone.

(Figure 1c) The sphenoid sinus demonstrates considerable variation in size. When underdeveloped, it lies anterior to the pituitary fossa, but with increasing pneumatisation, it extends beneath the fossa. Posterior extension into the basiocciput may occur, and in extensively pneumatised sinuses, aeration can also involve the greater wing of the sphenoid and the pterygoid processes. The sphenoid sinus drains into the sphenoethmoidal recess. It is closely related to the optic nerve, cavernous sinus, pituitary gland, and internal carotid arteries. Even minor pathology in this region may result in significant neurological or visual symptoms [

1,

2].

Embryological Development

The paranasal sinuses develop as mucosal outpouchings from the nasal cavity. The ethmoturbinals appear around the seventh week of fetal life and give rise to the middle and superior turbinates. The maxillary sinus begins to form at approximately the tenth week of gestation, while the ethmoid air cells progressively expand from the fifth month of fetal life. The sphenoid sinus has a prenatal origin; however, clinically significant pneumatisation occurs mainly during childhood, with the sinus becoming fully aerated by around 14 years of age. The frontal sinus is the last to develop, typically becoming radiologically apparent after the age of six to seven years and continuing to mature through adolescence. Its size and configuration generally stabilise by late adolescence to early adulthood, around 18–20 years of age

(Table 1) [

3,

4]. Knowledge of embryology helps explain the variations found in adults and offers forensic value, particularly in age estimation and individual identification.

Osteomeatal Complex (OMC)

The osteomeatal complex is the functional hub of sinus drainage. It includes:

Obstruction at any level of the OMC compromises drainage of the maxillary, frontal, and anterior ethmoid sinuses. Even minimal mucosal thickening in this region may disrupt normal ventilation and predispose to recurrent or chronic sinusitis. On high-resolution CT (HRCT), assessment of osteomeatal complex patency is therefore a key determinant in the evaluation of sinonasal disease and in planning endoscopic sinus surgery.

Radiological Evaluation of Paranasal Sinuses

A. Plain X-Ray

Although limited by overlapping structures, X-rays still provide a quick assessment of maxillary sinus disease. However, sensitivity is significantly lower than Sinus HRCT. The Waters, Caldwell, lateral, and submento-vertex views traditionally aid in evaluating the different sinuses. (5)

B. High-resolution computed tomography

High-resolution axial and coronal computed tomography is considered the method of choice in evaluating paranasal sinuses. It provides excellent anatomical detail, including anatomical variations, identifies obstructive patterns, and guides pre-operative planning and post-operative follow-up in cases of endonasal interventions. It visualises mucosal thickening, polyps, bony de-arrangements, fungal nodules, and OMC anatomy. (5, 6)

C. MRI

MRI provides complementary information to HRCT.MRI is valuable in assessing soft-tissue abnormalities, differentiating tumours from inflammatory processes, fungal sinusitis and evaluating complications such as orbital or intracranial extension. (6, 7)

D. Ultrasound

Sinus ultrasonography offers a rapid, safe, and inexpensive method for assessing fluid levels in cases of acute and subacute maxillary sinusitis. With minimal training, it can be effectively applied by clinicians in acute care and general practice settings. (8)

E. Angiography

Reserved for suspected vascular complications such as aneurysm or venous thrombosis.

Anatomical Variations and Their Relevance in Sinus Disease

Anatomical variations are common and often asymptomatic. However, certain variants can predispose to sinus obstruction or increase the complexity of surgical intervention.

Anatomical variations of sinuses

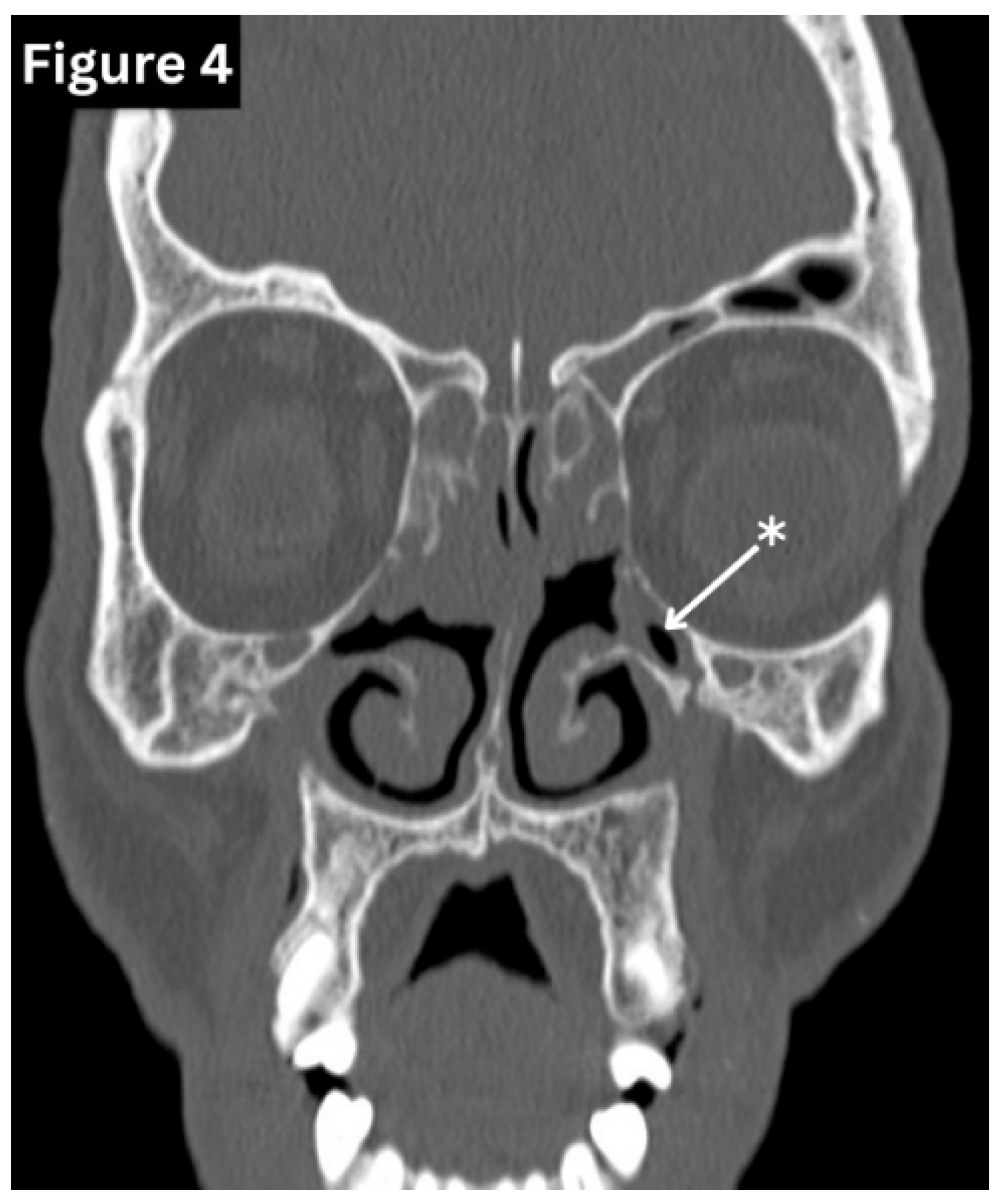

Anatomical variation of the paranasal sinuses is common and has important clinical and surgical implications. Variants of the maxillary sinus include internal septation, the presence of accessory ostia, and varying degrees of sinus hypoplasia. In cases of maxillary sinus hypoplasia, endoscopic intervention carries an increased risk of orbital entry, either through the lamina papyracea or the sinus floor, owing to altered anatomical relationships.

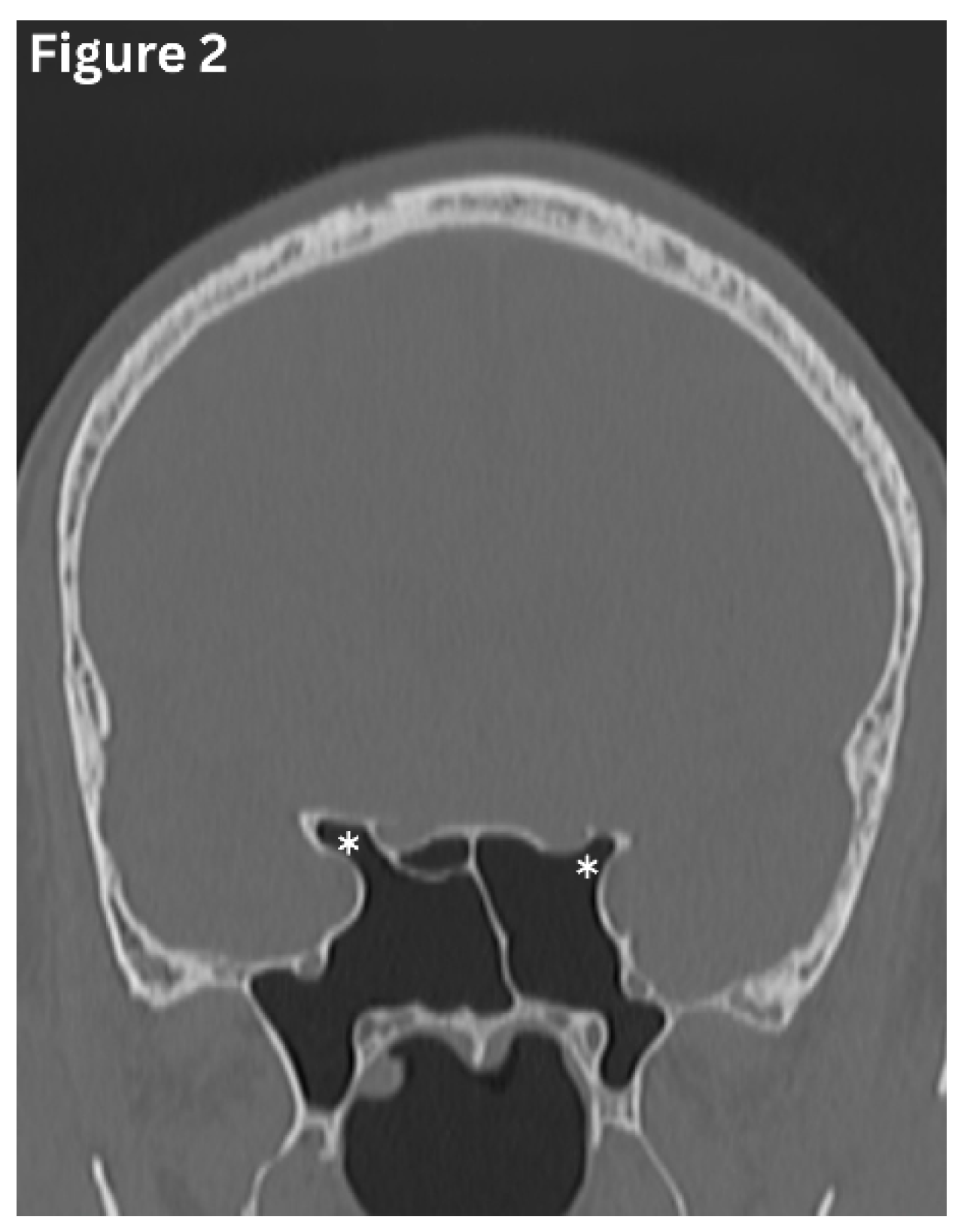

(Figure 4) The frontal sinuses frequently exhibit asymmetry in size and extent and are typically separated by a midline bony septum. One or both frontal sinuses may be markedly underdeveloped or absent in certain individuals. The sphenoid sinus demonstrates wide variability of variations, ranging from partial or complete agenesis to extensive pneumatisation, including extension into the clinoid processes and adjacent pterygoid or ethmoid bones.

(Figure 2) Variations in sphenoid septation, such as deviation or the presence of multiple septa, further contribute to the complexity of this region and are particularly relevant during surgical planning [

9,

10]

(Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Coronal CT image shows pneumatization of the sphenoid sinus extending into the anterior clinoid processes (asterisks).

Figure 2.

Coronal CT image shows pneumatization of the sphenoid sinus extending into the anterior clinoid processes (asterisks).

Figure 3.

Coronal CT image shows multiple septations in the sphenoid sinus, creating multiple compartments. (asterisks).

Figure 3.

Coronal CT image shows multiple septations in the sphenoid sinus, creating multiple compartments. (asterisks).

Figure 4.

Coronal CT image shows hypoplastic both maxillary sinuses(arrow). (

Figure 4:

courtesy of Fakhry Mahmoud Ebouda, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 60030).

Figure 4.

Coronal CT image shows hypoplastic both maxillary sinuses(arrow). (

Figure 4:

courtesy of Fakhry Mahmoud Ebouda, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 60030).

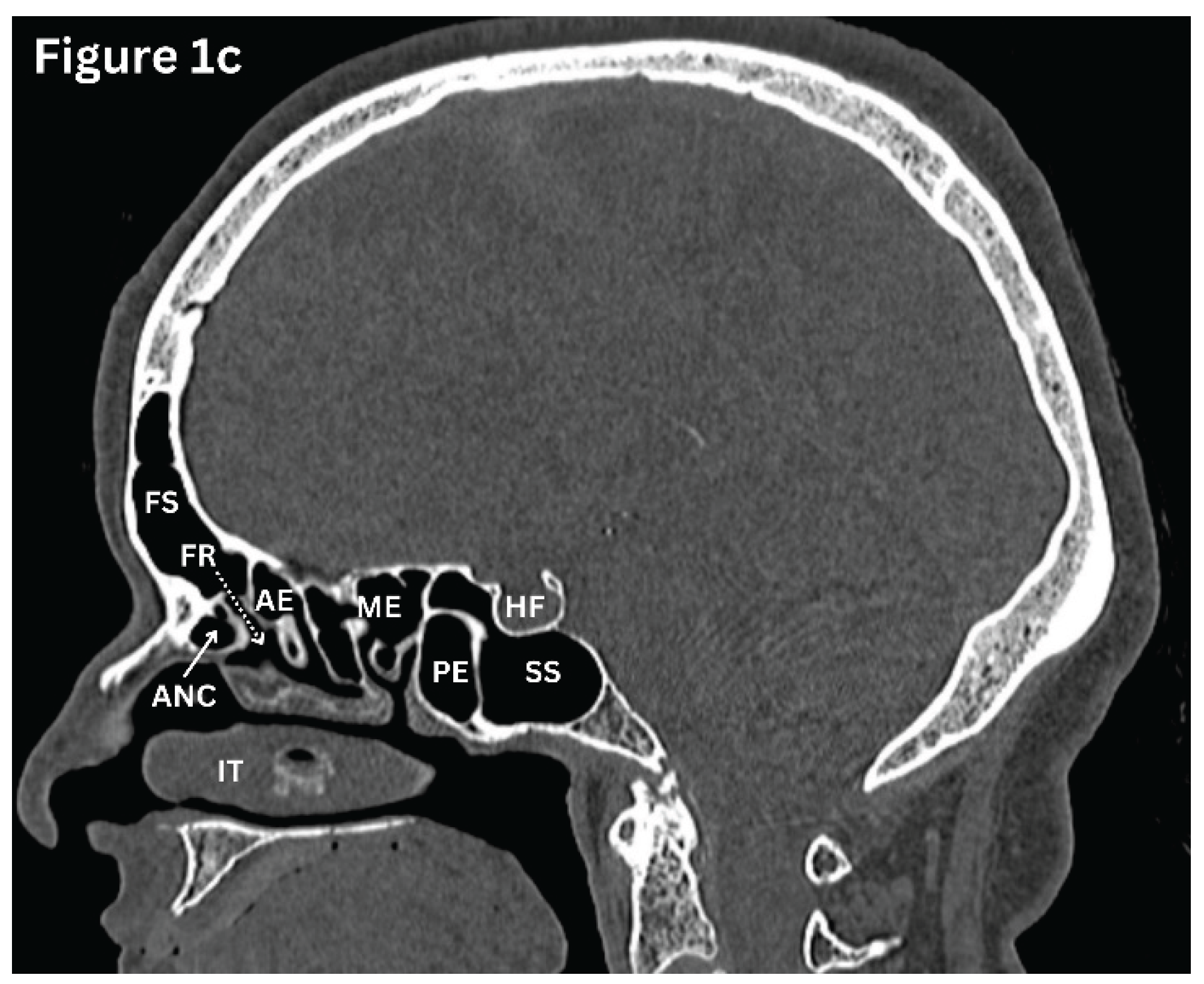

Concha Bullosa (CB)

This refers to a pneumatised vertical part of the middle turbinate.

(Figure 5) Concha Bullosa is observed in approximately 24–55% of individuals and is most commonly present on both sides of the nose [

11]. This variation may compress the OMC, leading to nasal obstruction or recurrent rhinosinus infections.

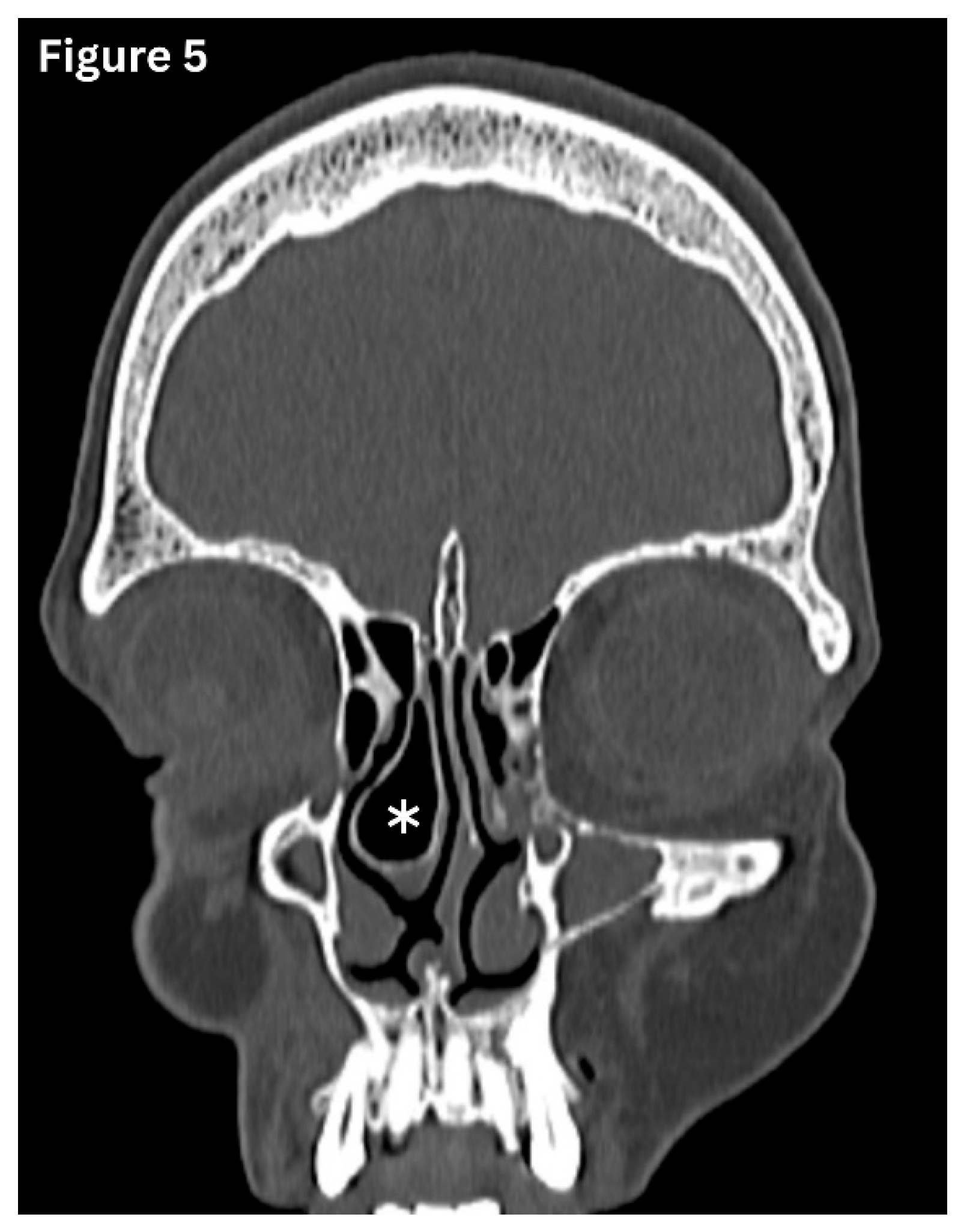

Deviated Nasal Septum (DNS)

This is defined as the displacement of the nasal septum from the midline, resulting in an increased angle of the septum detected on a coronal CT scan or nasal endoscopy.

(Figure 6) A significantly deviated septum reduces airflow and alters mucociliary clearance. It may narrow the middle meatus, thereby increasing the risk of chronic rhinosinusitis in maxillary or ethmoidal sinuses [

11].

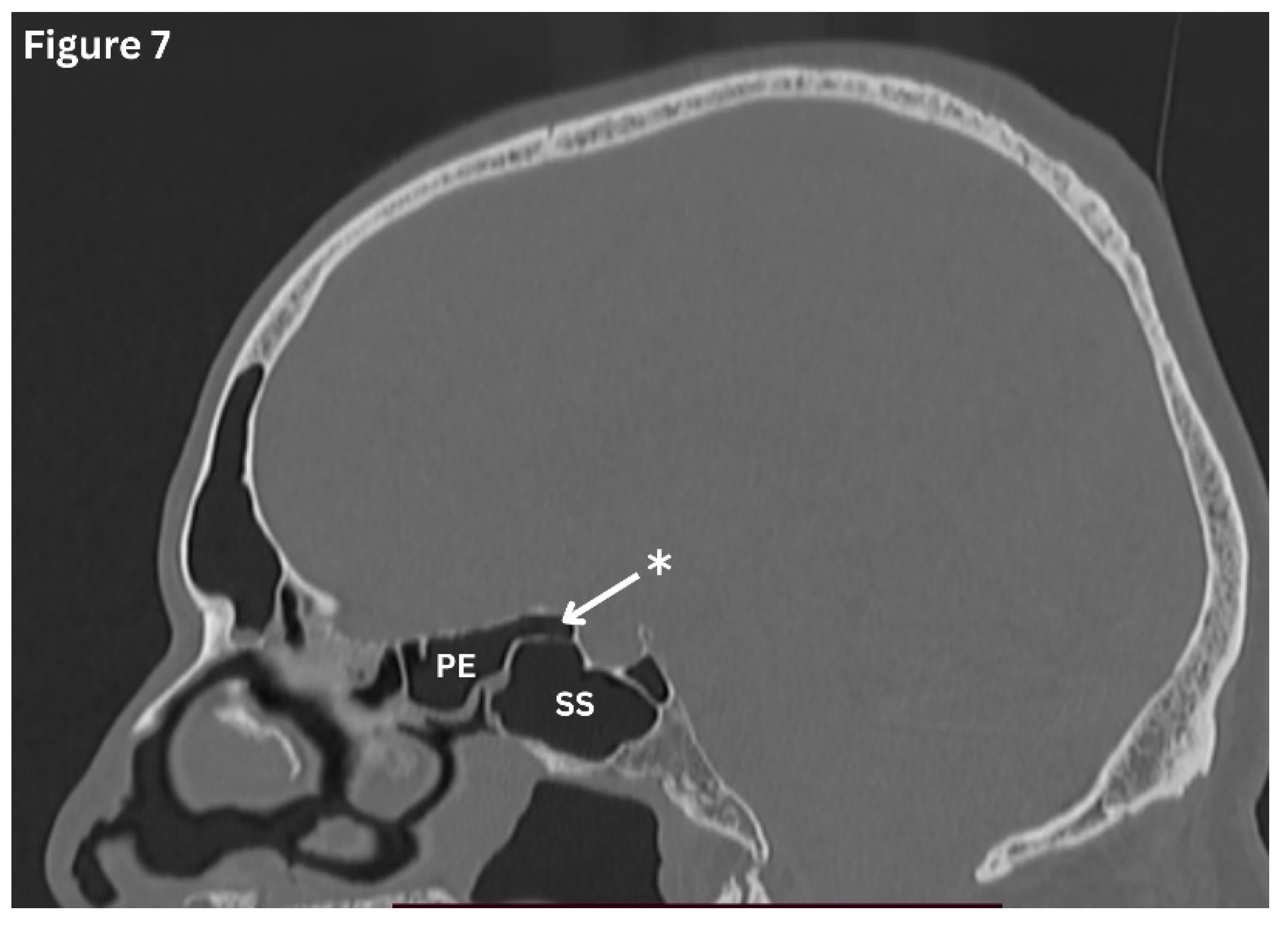

Onodi Cells (OC)

Onodi cells are defined as posterior-most ethmoid cells, extend up to the sphenoid sinus and anterior clinoid processes.

(Figure 7) Their prevalence ranges from approximately 3% to 66% based on CT findings [

12]. Onodi cells have a close relationship with the sphenoid sinus, optic nerve, and internal carotid artery, which increases the risk of complications during endoscopic sinus surgery [

12]. Understanding these variations using sinus HRCT ensures safer and more effective sinus surgery. In addition, inflammation of the Onodi cell can lead to visual symptoms because of its intimate anatomical relationship with the optic nerve [

11].

Figure 7.

Sagittal CT image shows posterior-most ethmoid cells, extending over the sphenoid sinus (Onodi cells) (Arrow).

Figure 7.

Sagittal CT image shows posterior-most ethmoid cells, extending over the sphenoid sinus (Onodi cells) (Arrow).

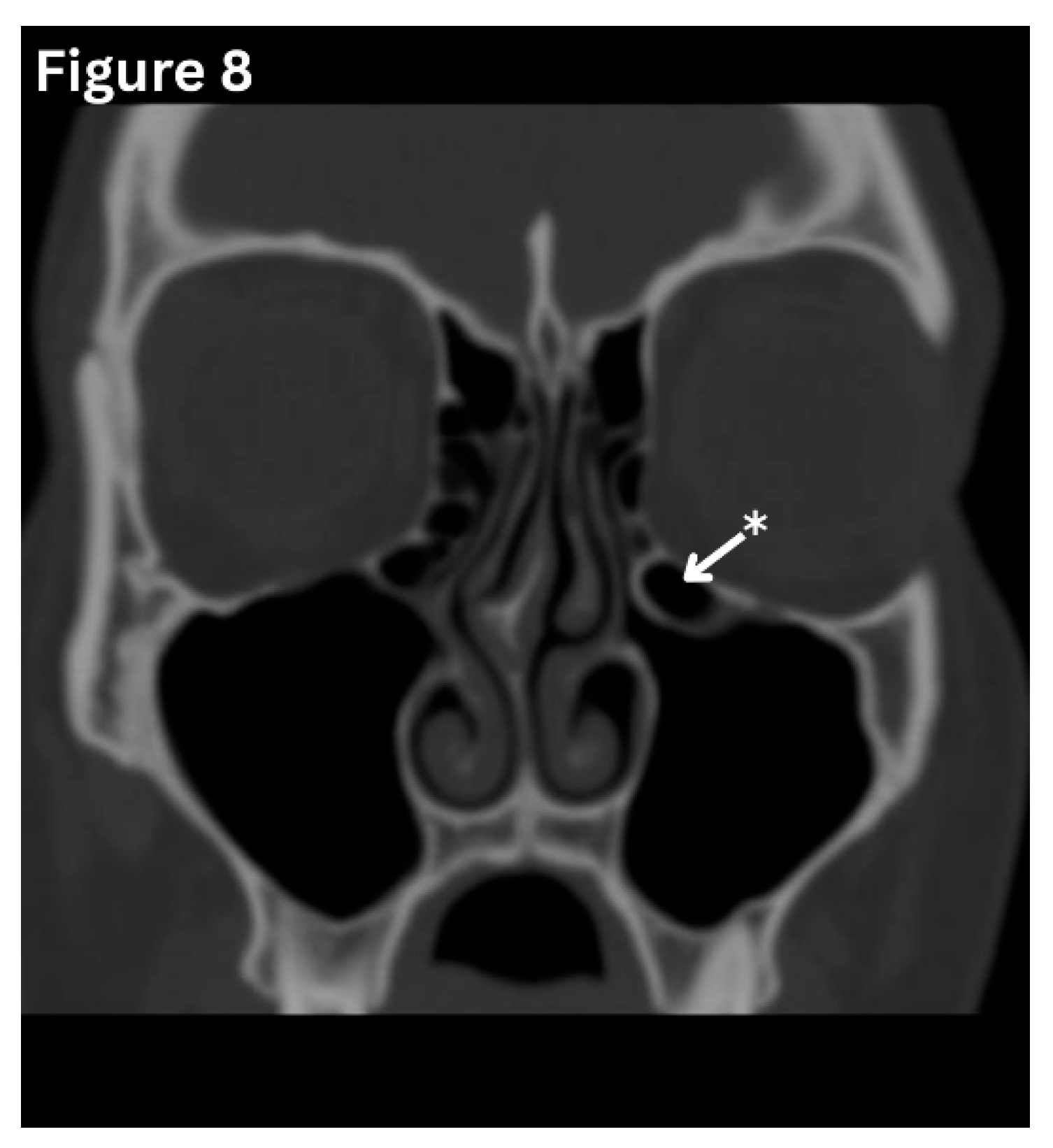

Figure 8.

Coronal CT image shows a teardrop-shaped air cell (Haller Cell) located at the inferomedial aspect of the orbital floor. (Arrow) (

Figure 8-

Courtesy of The Radswiki, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 11469).

Figure 8.

Coronal CT image shows a teardrop-shaped air cell (Haller Cell) located at the inferomedial aspect of the orbital floor. (Arrow) (

Figure 8-

Courtesy of The Radswiki, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 11469).

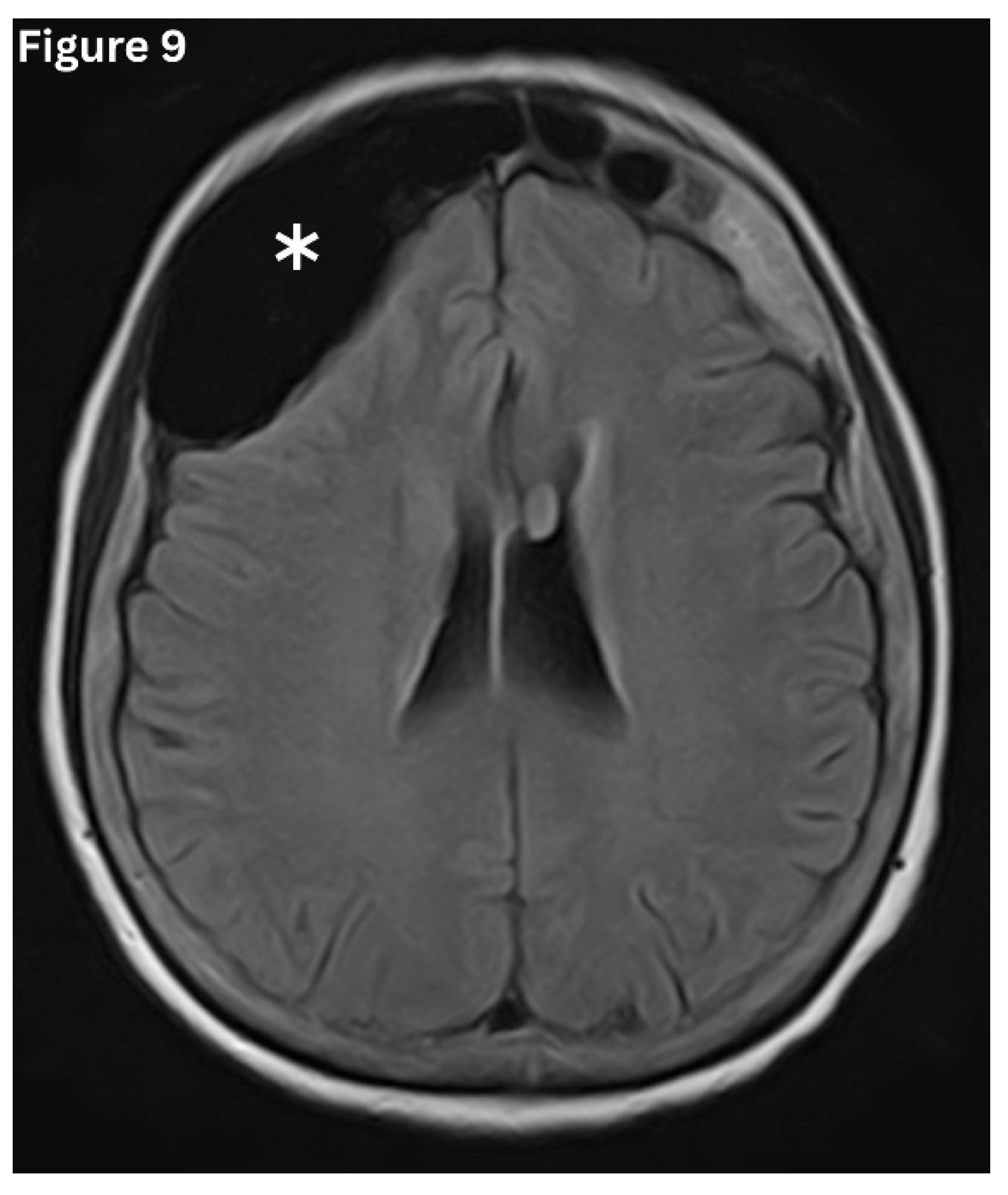

Pneumosinus dilatans

Pneumosinus dilatans (PSD)is characterised by abnormal expansion of a paranasal sinus beyond its normal boundaries, while maintaining normal mucosal lining and preserving bony walls

. (Figure 9 and

Figure 10) It is a developmental variant and is most often seen in the frontal, sphenoid, and maxillary sinuses. PSD most often affects a single sinus rather than multiple cavities, with isolated involvement reported in nearly 80% of cases [

14]. It is frequently detected incidentally on imaging. However, some may present with frontal bossing and a spectrum of visual disturbances, including proptosis, diplopia and headache. This predisposes to recurrent episodes of sinusitis due to impairment of normal sinus drainage [

14].

Pathophysiology of Sinusitis

Sinusitis results from mucosal inflammation triggered by infection, allergies or anatomical obstruction. When sinus drainage is impaired, mucus accumulates, becomes stagnant, and invites microbial proliferation, leading to recurrent or chronic disease [

15].

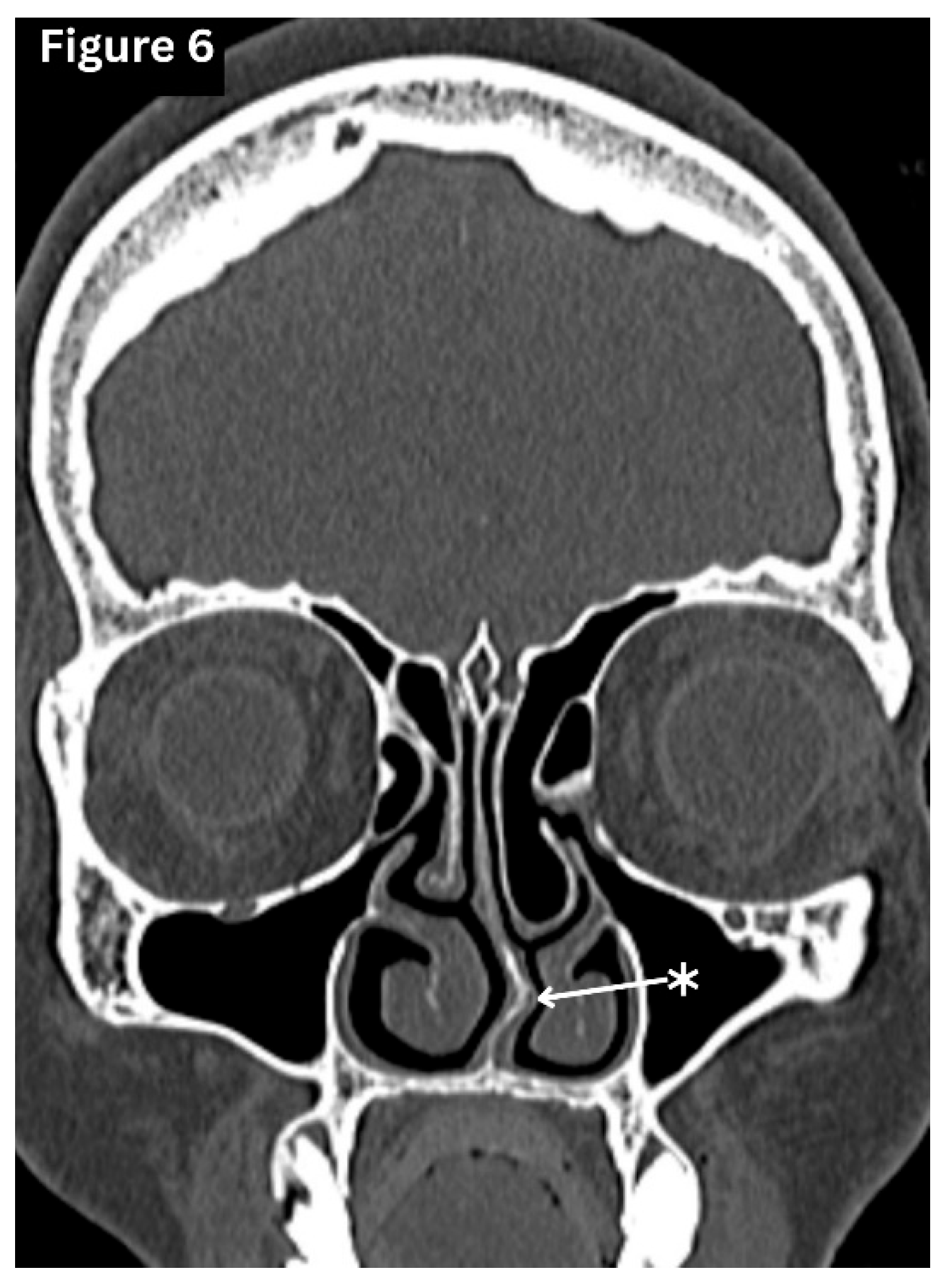

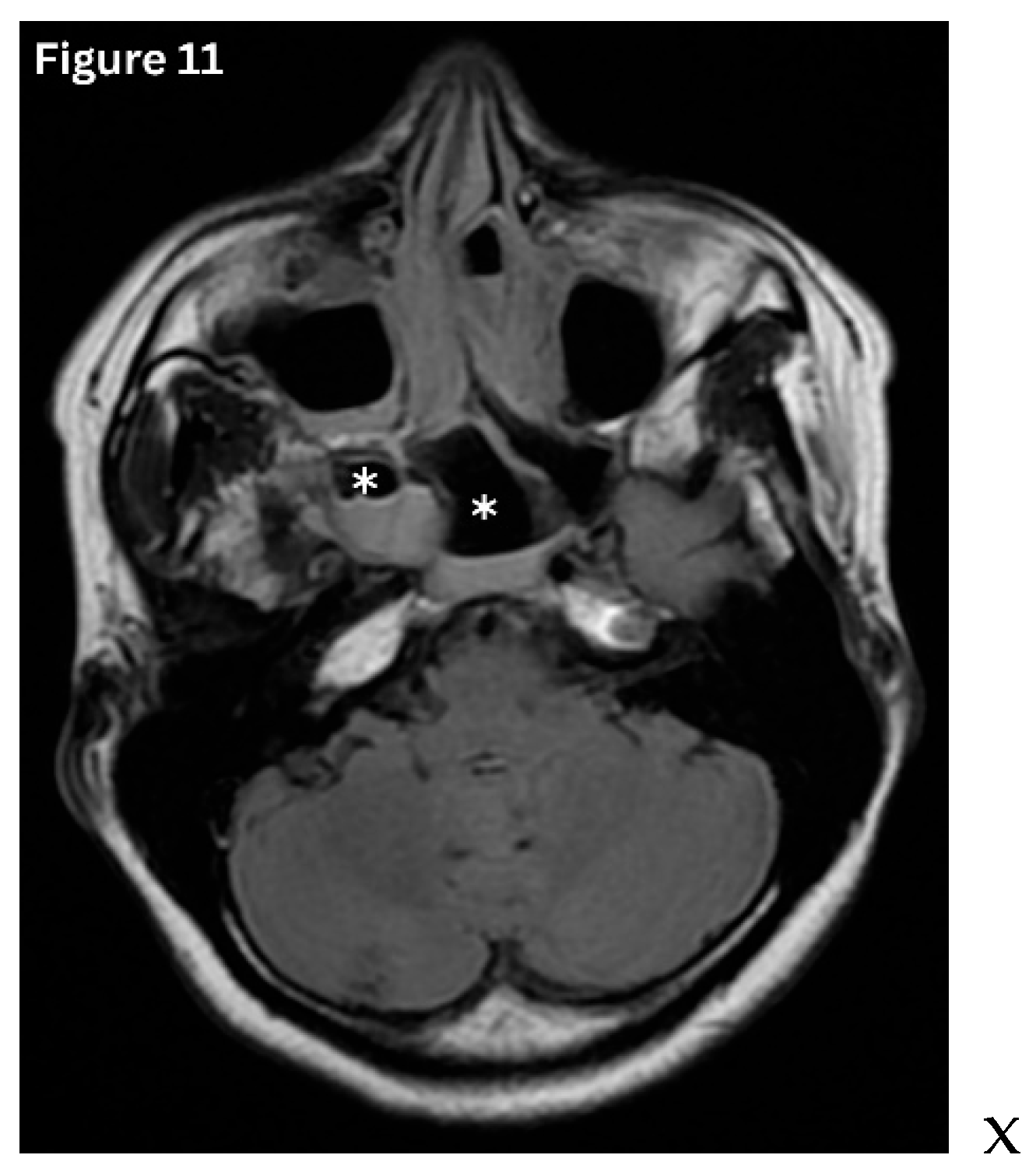

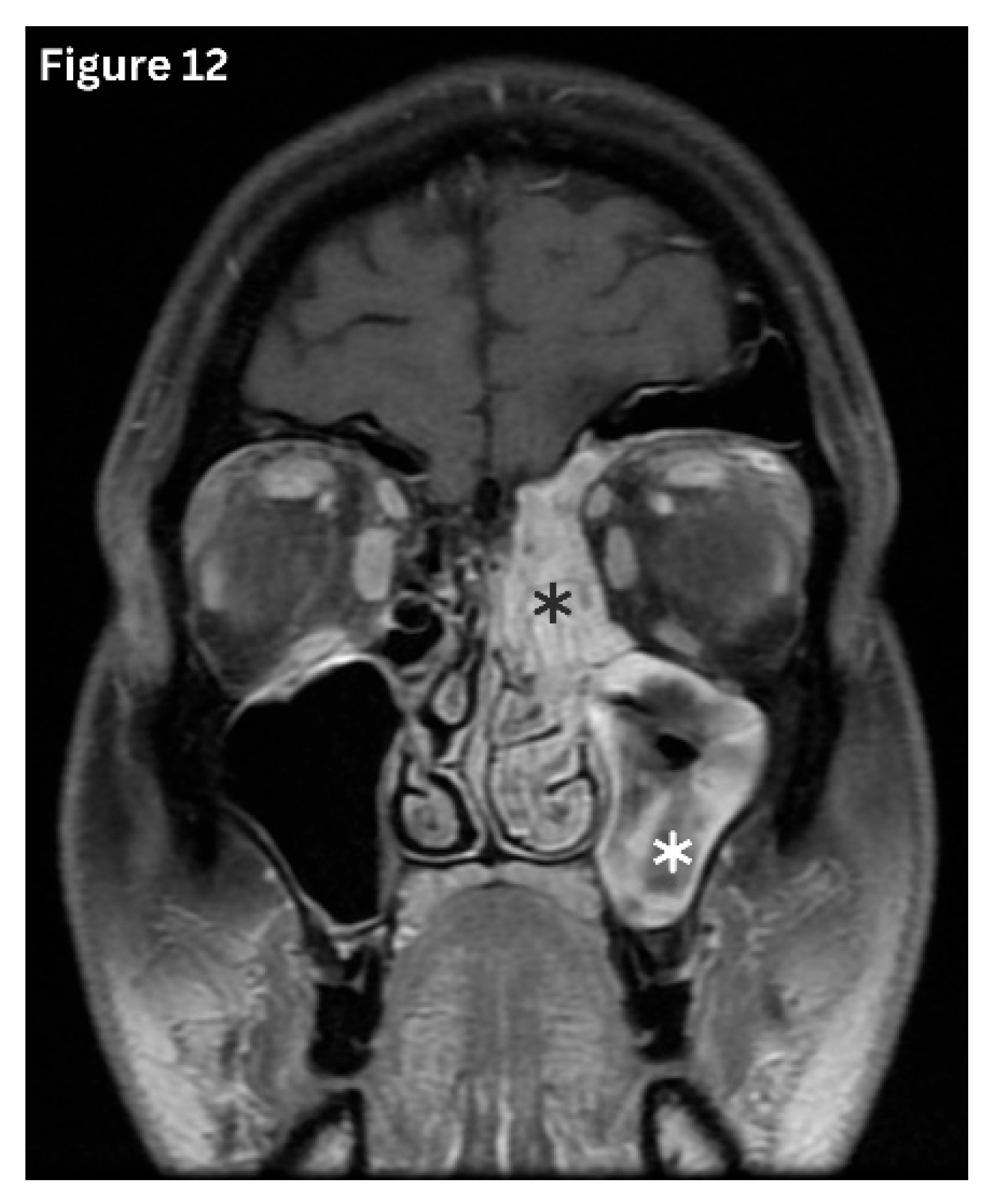

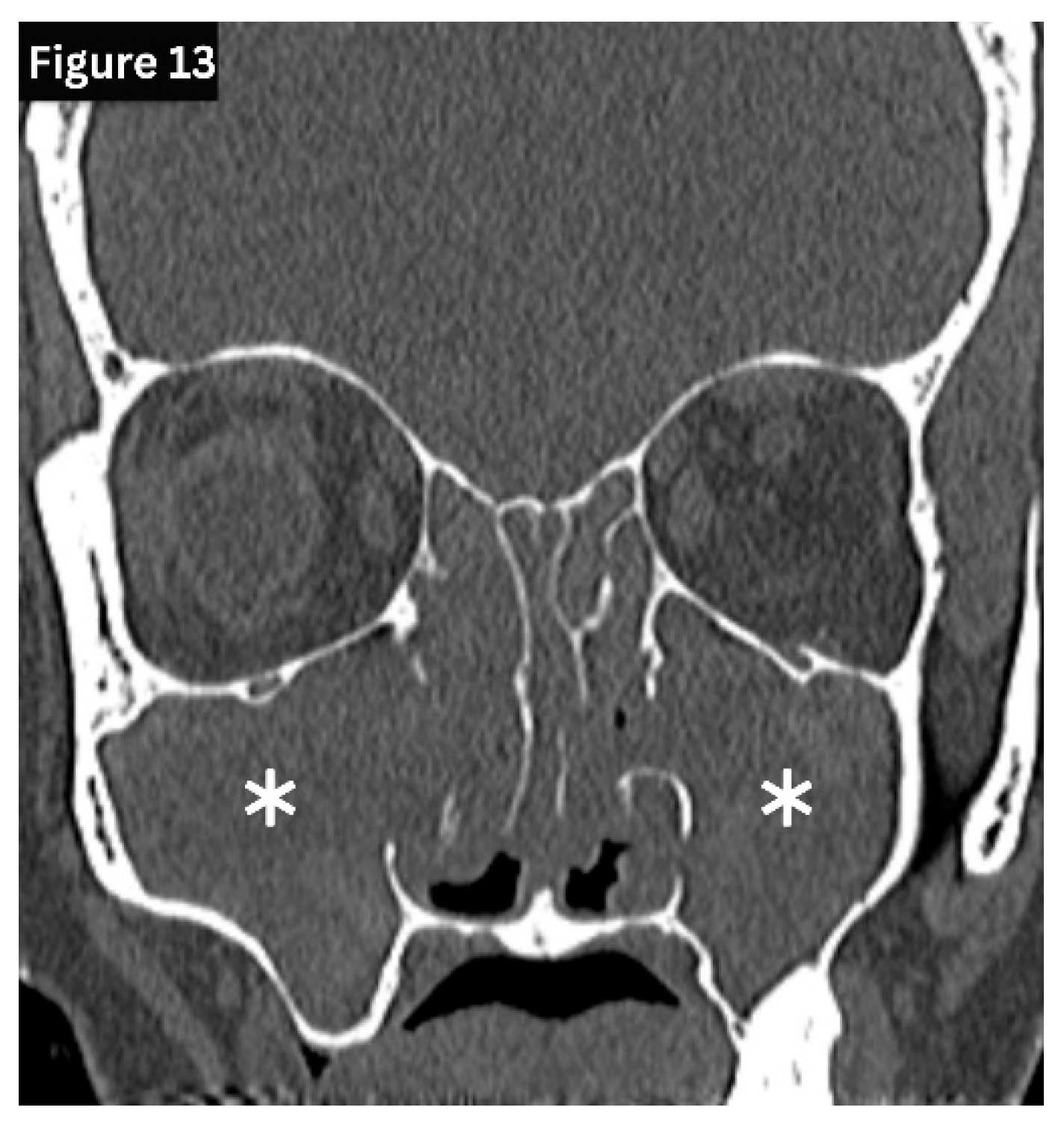

Types of Sinusitis and Imaging Patterns

Acute sinusitis typically demonstrates air–fluid levels, diffuse mucosal thickening, and narrowing of the sinus drainage pathways on imaging.

(Figure 11) Chronic sinusitis develops over several months and is characterised by persistent polypoid mucosal thickening, bony remodelling, and sclerosis of the sinus walls on sinus HRCT.

(Figure 12 and

Figure 13) Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis is characterised by expanded sinuses containing centrally hyperdense inspissated mucin, accompanied by a peripheral hypodense mucosal rim, often in association with nasal polyps, as seen on HRCT. Recurrent and subacute sinusitis exhibits overlapping features of both acute and chronic disease. This is often associated with partial ostial obstruction or underlying anatomical variations [

5,

16].

Complications of Sinusitis

Complications of sinusitis largely arise from direct extension of infection, indicating the close anatomical relationship between the paranasal sinuses and adjacent vital structures. Orbital complications, most often associated with ethmoid sinusitis, may be presented as orbital cellulitis, subperiosteal abscess, or orbital abscess, carrying a risk of visual impairment and ophthalmoplegia. Intracranial involvement is more commonly associated with frontal or sphenoid sinusitis. Complications include meningitis, brain abscess, subdural empyema, and cavernous sinus thrombosis. Osseous complications may also occur, particularly sinus wall osteomyelitis, typically manifesting as Pott’s puffy tumour. Early and appropriate radiological assessment is essential to limit morbidity and prevent permanent sequelae [

15,

16].

Conclusions

A deep understanding of paranasal sinus anatomy and its radiological relationships is fundamental to diagnosing and managing sinusitis effectively. Radiology not only identifies mucosal disease but also reveals anatomical variants, assesses drainage pathways, and detects life-threatening complications. CT and MRI have transformed sinus evaluation, enabling clinicians to approach sinusitis with greater precision, safety, and insight.

Author Contributions

SRS formulated the concept, designed the review, conducted the literature. review: and wrote the manuscript. TSL conducted the literature review and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This review received no external funding.

Availability of data and materials

Acquired DICOM medical images during the current review are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The subject's identifying information was removed from the radiology images.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was not considered, as our work is a narrative review. However, we have secured informed consent to publish radiological images from each patient Additionally, we have intentionally removed identifying information from the radiology images. Image credits were given to

Figure 4 and

Figure 8. Consent was obtained in the local and English languages, and fully completed consent forms are available upon request.

References

- Ogle OE, Weinstock RJ, Friedman E. Surgical anatomy of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics. 2012 May 1;24(2):155-66. [CrossRef]

- Sinnatamby CS. Last’s anatomy: regional and applied. 12th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2011.

- Goldman-Yassen AE, Meda K, Kadom N. Paranasal sinus development and implications for imaging. Pediatric Radiology. 2021 Jun;51(7):1134-48. [CrossRef]

- Lee S, Fernandez J, Mirjalili SA, Kirkpatrick J. Pediatric paranasal sinuses—Development, growth, pathology, & functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Clinical Anatomy. 2022 Sep;35(6):745-61. [CrossRef]

- Newadkar UR. Sinus radiography for sinusitis:“Why” and if considering it then “how”?. Journal of Current Research in Scientific Medicine. 2017 Jan 1;3(1):9-15.

- Ali, B., Nadeem, Z., Naeem, M., Arif, K., Zaman, A., Noor, A., Zahid, M.H., Mustafa, R., Akilimali, A. and Ago, J.L., 2025. Evaluation of the Frequency of Anatomic Variations of the Paranasal Sinus Region by Using Multidetector Computed Tomography: A Hospital-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Health Science Reports, 8(3), p.e70535. [CrossRef]

- Pulickal GG, Navaratnam AV, Nguyen T, Dragan AD, Dziedzic M, Lingam RK. Imaging sinonasal disease with MRI: providing insight over and above CT. European Journal of Radiology. 2018 May 1;102:157-68. [CrossRef]

- Hsu CC, Sheng C, Ho CY. Efficacy of sinus ultrasound in diagnosis of acute and subacute maxillary sinusitis. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association. 2018 Oct 1;81(10):898-904. [CrossRef]

- Beale TJ, Madani G, Morley SJ. Imaging of the paranasal sinuses and nasal cavity: normal anatomy and clinically relevant anatomical variants. In Seminars in Ultrasound, CT and MRI 2009 Feb 1 (Vol. 30, No. 1, pp. 2-16). WB Saunders. [CrossRef]

- Onwuchekwa RC, Alazigha N. Computed tomography anatomy of the paranasal sinuses and anatomical variants of clinical relevance in Nigerian adults. Egypt J Ear Nose Throat Allied Sci. 2017;18(1):31–8. [CrossRef]

- Malpani SN, Deshmukh P. Deviated nasal septum a risk factor for the occurrence of chronic rhinosinusitis. Cureus. 2022 Oct 13;14(10). [CrossRef]

- Chmielik LP, Chmielik A. The prevalence of the Onodi cell–most suitable method of CT evaluation in its detection. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2017 Jun 1;97:202-5. [CrossRef]

- Eltayeb G, Abdulla GJ, Karimzadeh S, Ramadan A, Alrifai AA, Albaqali M, Salman B, Alrashdan MS, Shetty S. Prevalence and radiographic features of Haller cells: A systematic review. Imaging Science in Dentistry. 2025 Jul 1;55(3):215. [CrossRef]

- Seigell S, Singhal S, Gupta N, Verma RR, Gulati A. Pneumosinus dilatans: a myriad of symptomology. Indian Journal of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery. 2022 Oct;74(Suppl 2):1305-9. [CrossRef]

- Wyler B, Mallon WK. Sinusitis update. Emergency Medicine Clinics. 2019 Feb 1;37(1):41-54. [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld RM, Piccirillo JF, Chandrasekhar SS, Brook I, Kumar KA, Kramper M, et al. Clinical practice guideline (update): adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152(2 Suppl):S1–S39. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).