1. Introduction

Arsenic is a metalloid widely present in the environment as both inorganic and organic species, arising from natural sources as well as anthropogenic activities. Inorganic arsenic (iAs) mainly comprises arsenite (As(III)) and arsenate (As(V)), which occur in the trivalent and pentavalent oxidation states, respectively. These two species are considered the most toxic forms of As and show comparable potency, although As(III) generally displays slightly higher toxicity due to its greater reactivity toward cellular thiols and its easier translocation across biological membranes [

1,

2].

On the other hand, organoarsenical compounds (oAs), which include arsenobetaine (AB), arsenocholine (AC), monomethylarsonic acid (MMA), dimethylarsinic acid (DMA), arsenosugars and arsenolipids, are generally characterized by substantially lower toxicity. AB and AC, together with several arsenosugars, are the predominant species in seafood and seaweeds, where they can reach high concentrations, while MMA and DMA may be found in plant-based matrices as intermediate products of microbial or plant metabolism [

3,

4].

iAs species have been classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as “carcinogenic to humans” (Group 1). More recently, the IARC classified DMA and MMA as “possibly carcinogenic to humans” (Group 2B) and AB and other oAs compounds not metabolized in humans, as “not classifiable as to their carcinogenicity to humans” (Group 3) [

5]. Evidence from epidemiological studies suggests that low to moderate exposure to iAs can cause several adverse effects including skin, bladder and lung cancers, skin lesions, spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, infant mortality, congenital heart disease, respiratory disease, chronic kidney disease, neurodevelopmental effects, ischemic heart disease and carotid artery atherosclerosis [

6].

Following the request of the European Commission (EC), based on newly available epidemiological studies, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) in 2024 updated the human health risk assessment of iAs in food. A Reference Point (RP) of 0.06 μg iAs/kg bw per day was identified by EFSA experts based on the benchmark dose lower confidence limit corresponding to the 5% increase of the background incidence for skin cancer after adjustment for confounders (BMDL05). This RP was considered adequate to cover lung and bladder cancer and several other adverse effects [

6].

Food and drinking water represent the main routes of exposure to iAs for the general European population, with the highest mean dietary exposure observed in younger age groups. Rice and rice-based products are among the main contributors across these populations [

7]. Rice (

Oryza sativa L.), in fact, accumulates significantly higher levels of iAs than other cereals due to its nature and the anaerobic growth conditions in rice fields. It is a staple food in many South East Asian countries but it is also increasingly consumed in West countries due to its bland taste, nutritional value, absence of gluten and relatively low allergic potential. [

8,

9,

10].

In 2021, considering the new available occurrence data for iAs in food, EFSA revised the dietary exposure assessment to iAs and identified rice drinks as products deserving attention when assessing dietary exposure to iAs, due to the large consumption as milk alternative in certain specific population group as vegans/vegetarians, people suffering of coeliac disease or lactose intolerance, those wishing to avoid hormones in animal milks due to cancer related illness. Moreover, limited consumption data and high uncertainty linked to left-censored measurements represented other limitations [

11]. In light of that information, the EC has set a new maximum level of 0.030 mg kg

-1 for iAs in non-alcoholic rice-based drinks and EFSA recommended the collection of new consumption data for specific populations and the use of validated analytical methods with adequate sensitivity [

12].

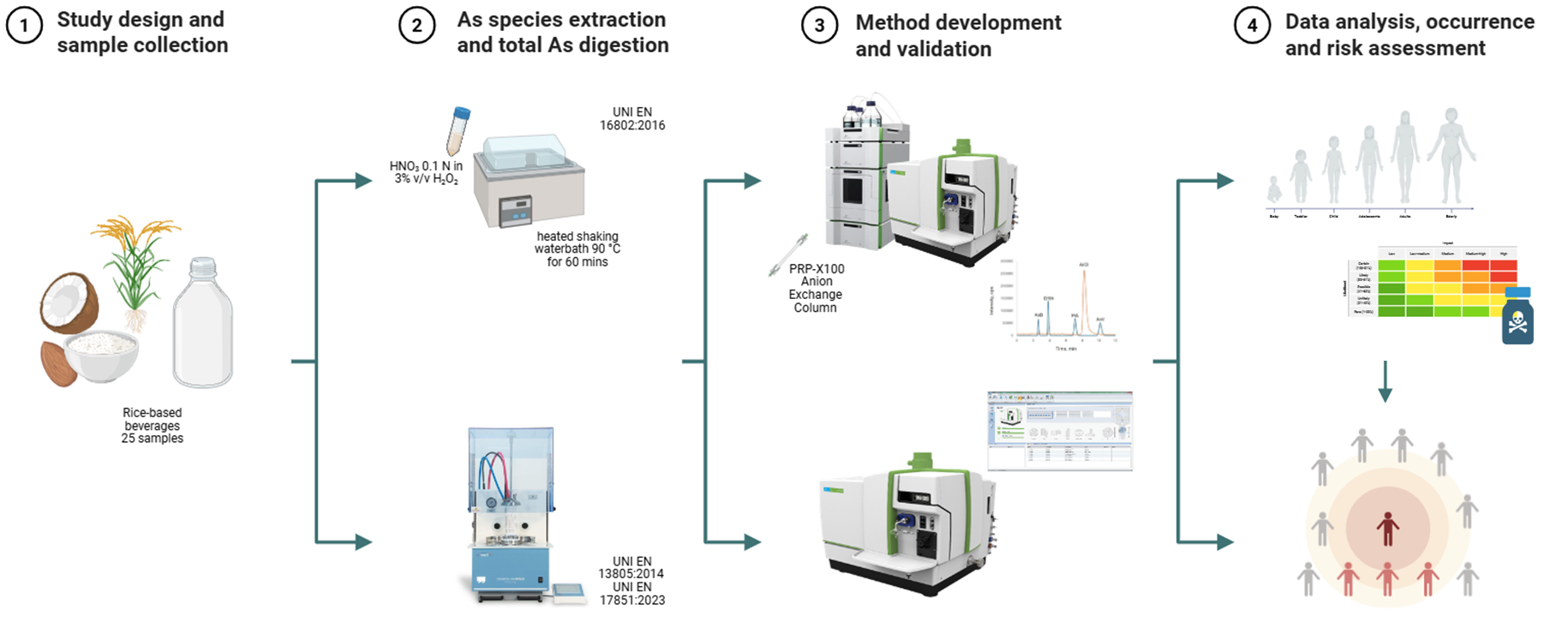

In this framework, a method for the determination of iAs and oAs species (AB, DMA and MMA) was developed and validated in accordance with UNI EN 16802:2016 [

13]. In parallel, total arsenic (tAs) was quantified by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). The validated method was applied to 25 rice-based beverages collected to be representative of the Italian market. The resulting occurrence dataset revealed a generally homogeneous contamination profile, and the findings were compared with data reported by EFSA and published in recent international studies on similar matrices. The present study was carried out within the framework of the activities of the Italian National Reference Laboratory for metals and nitrogenous compounds in food.

Based on the analytical results and the most recent Italian consumption data, dietary exposure to iAs from rice drinks was estimated and the risk was characterized in general population, consumers and subgroups using the margin of exposure approach. The outcome indicates a potentially concerning scenario for certain population groups. Although the risk appears insufficiently controlled, the data clearly highlight the need for updated and robust consumption information, particularly in view of evolving dietary patterns and the growing use of plant-based beverages among specific subgroups of the population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

Ultrapure grade water was used throughout this study (18.3 MΩ cm, Millipore S.p.A. Zeener UP 900 Scholar UV).

Suprapure nitric acid (HNO3) 67 - 69% v/v (ROMIL Ltd, Waterbeach, Cambridge, England) was used for the mineralization procedure, while ultrapure HNO3 (67 - 69% v/v ROMIL Ltd, Waterbeach, Cambridge, England) was used for the preparation of the extraction mixtures. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) used in both extraction and mineralization is of suprapure grade (30% v/v, ROMIL Ltd, Waterbeach, Cambridge, England).

The calibration and internal standard solutions of rhodium and arsenic used for the determination of tAs were obtained from certified rhodium and germanium standards (both 1000 ± 5 mg l-1, High Purity Standard, Charleston, SC.) and As (1000 mg l-1, CPAchem Ltd., Bulgaria).

Standard solutions of the 1 mg l-1 arsenical species (AB, MMA, DMA) used in the speciation analysis were obtained by dissolution in water of AB (Fluka-Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), MMA (Tri Chemical Laboratories Inc., Yamanashi, Japan) and DMA (≥ 99.0 % Sigma-Aldrich-Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), respectively. The solution of As(V) was obtained from the As+5 standard (999 ± 5 µg ml-1, Inorganic Ventures, Christiansburg, US Virginia). Solutions of the arsenical species were stored in the dark at -20°C to prevent possible interconversion between the different species, and their concentration was verified by ICP-MS analysis. Standard solutions were daily diluted with the extraction solution for appropriate matrix matching and subjected to speciation analysis by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (HPLC-ICP-MS) to verify their chromatographic purity.

Ammonium carbonate (NH4)2CO3 (99.999% Sigma-Aldrich, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), ammonia solution (25% v/v Suprapur®, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and methanol CH3OH (HPLC grade, Panreac Quimica S.A., Barcelona, Spain) were used for the preparation of the mobile phase used for speciation analysis. Prior to use, the mobile phase was filtered with the Millipore® Stericup® vacuum filtration system equipped with a Millipore (DuraporeTM) 0.22 μm membrane filter (VWR International, Milan, Italy) and degassed with a NEXAR Channel Vacuum Degasser (PerkinElmer, US-Shelton, USA).

2.2. Reference Materials and Samples

Twenty-five samples of rice-based drinks were purchased from various retail outlets to ensure representativeness of products commonly available on the Italian market. All rice drink samples contain water, rice (at varying percentages), sunflower oil and sea salt. Two products were fortified with vitamins (vit B2, vit B12, vitD), while guar gum and gellan gum were added as stabilizers and texturizing agents in 4 samples. No specific information on the origin of the rice was provided on product labels, except for rice of Italian origin (48% of samples). The majority of products (88%) were certified organic. The rice-based drinks were stored at room temperature prior to opening and at -20 °C thereafter.

NIST rice flour SRMs 1568b (Gaithersburg, US-MD), NMIJ 7532-a (Ibaraky, Japan) and ERM-BC211 (Geel, Belgium) were used as certified reference materials (CRMs) for As species and tAs determination.

2.3. Instrumentation

All analytical determinations were performed by a NexION® 2000 Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer (PerkinElmer, Shelton, USA) equipped with a nickel Triple Cone Interface, a Meinhard quartz concentric nebulizer, and a quartz cyclonic spray chamber. For speciation analysis a NexSAR™ 200 inert HPLC pump was used. Syngistix™ (version 3.3) for ICP-MS and Clarity (version 8.1) (PerkinElmer, US-Shelton) software programs were used for total and speciation analyses, respectively. Operational conditions were reported in

Table 1.

2.2. Total Arsenic Determination

Total arsenic was determined by ICP-MS, according to the European Standard UNI EN17851:2023 [

14], following closed vessel microwave-assisted digestion performed using a Milestone ultraWAVE microwave system (FKV, Bergamo, Italy) equipped with a Teflon 15-vessel rotor.

Approximately 1.0 g of each sample (0.3 g ca. for CRMs) was weighed into a Teflon vessel and added with 3 ml of HNO3, 3ml of H2O and 1ml of H2O2. Samples were subjected to a microwave digestion program with a temperature increase to 200 °C over 40 minutes, followed by a holding period at this temperature for additional 25 min.

After cooling at room temperature, the digested samples were transferred to polypropylene tubes and diluted up to 20 ml with water. The tAs concentration was determined after appropriate dilution using the collision mode (KED) for the removal of ArCl interference. Quantification was performed by external calibration (1% HNO3) with rhodium (1 mg l-1) as internal standard.

2.3. Arsenic Speciation

The method used for iAs was based on the European Standard UNI EN 16802:2016 for the determination of iAs in foodstuffs of marine and plant origin by anion-exchange HPLC-ICP-MS [

13] after a mild acid water bath extraction. This analytical method provides complete oxidation with quantitative conversion of As(III) to As(V), without conversion of other oAs into iAs, so that the quantification of As(V) corresponds to iAs (sum of As(III) and As(V)), which appears as a well-separated peak in the HPLC-ICP-MS chromatogram, with an improvement in the detection sensitivity for iAs. ArCl interference was resolved chromatographically. The standard mode for ICP-MS determination was used. Briefly, 1.0 g of each rice drink sample (0.3 g ca. for CRMs) was treated with a solution of 0.1 M HNO

3 and 3% H

2O

2 in a heated water bath at 90 °C ± 2 °C under gentle agitation for 60 min ± 5 min.

After cooling, the extracts were centrifuged for 15 min at 8000 rpm and 4 °C, and the supernatants filtered with PVDF 0.22 μm filters.

2.4. Dietary Exposure Assessment

Dietary exposure to iAs from rice-based drinks was estimated by combining the occurrence data generated in this study with individual food consumption data from the most recent Italian national dietary surveys (IV SCAI CHILD and IV SCAI ADULT), as included in the EFSA Comprehensive European Food Consumption Database (update: December 2022). [

15,

16]. For the total dietary exposure to iAs in the Italian population the results of latest EFSA chronic dietary exposure assessment were used [

7].

To ensure accurate matching between consumption records and analytical data, the FoodEx2 classification system was applied. Occurrence values for iAs were assigned to the corresponding FoodEx2 code along the following hierarchical pathway:

Exposure hierarchy (L1): Products for non-standard diets, food imitates and food supplements → (L2): Meat and dairy imitates → (L3): Dairy imitates → (L4): Milk imitates → (L5): Rice drink. Only consumption events explicitly coded as “Rice drink” at the L5 level were included [

17].

A deterministic chronic exposure assessment was conducted following EFSA standard methodology. For each subject, daily intake of rice drinks (g/day) was expressed on a body weight basis (g/kg bw per day), using the individual body weight recorded in the survey. Exposure was estimated by multiplying the consumption amount by the mean concentration of iAs measured in rice drink samples. Exposure calculations were performed for both (i) all subjects, including non-consumers (zero-consumption on recording days), and (ii) consumers only, defined as individuals reporting at least one consumption event of rice drink [

11].

Given the absence of censored values in the analytical dataset, no substitution approach (lower bound (LB)/ middle bound (MB)/ upper bound UB) was required for the rice drink occurrence. For comparison with overall dietary exposure, values from EFSA 2021 chronic exposure assessment were used (Annex B EFSA 2021), expressed as LB and UB estimates. Exposure estimates were generated for the population groups defined in the Comprehensive Database: toddlers (12–35 months), other children (3–9 years), adolescents (10–17 years), adults (18–64 years), and the elderly (≥65 years). Mean chronic exposure was used as the relevant metric for risk characterization, in line with EFSA guidance for substances with long-term effects.

2.5. Risk Characterization

Risk characterization was performed using the margin of exposure (MOE) approach, as recommended by EFSA for substances that are both genotoxic and carcinogenic, such as iAs. The MOE is the ratio between the RP (the dose at which a low but measurable adverse effect is observed) and the human intake, and therefore it makes no implicit assumptions about a “safe” intake. Therefore, this approach is considered by the Scientific Committee as more appropriate for substances that are both genotoxic and carcinogenic [

18]. Based on the available data from human studies, an MOE of 1 or less would correspond to an exposure level to iAs that might be associated with an increased risk of skin cancer [

6].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Method Validation for Inorganic Arsenic Determination

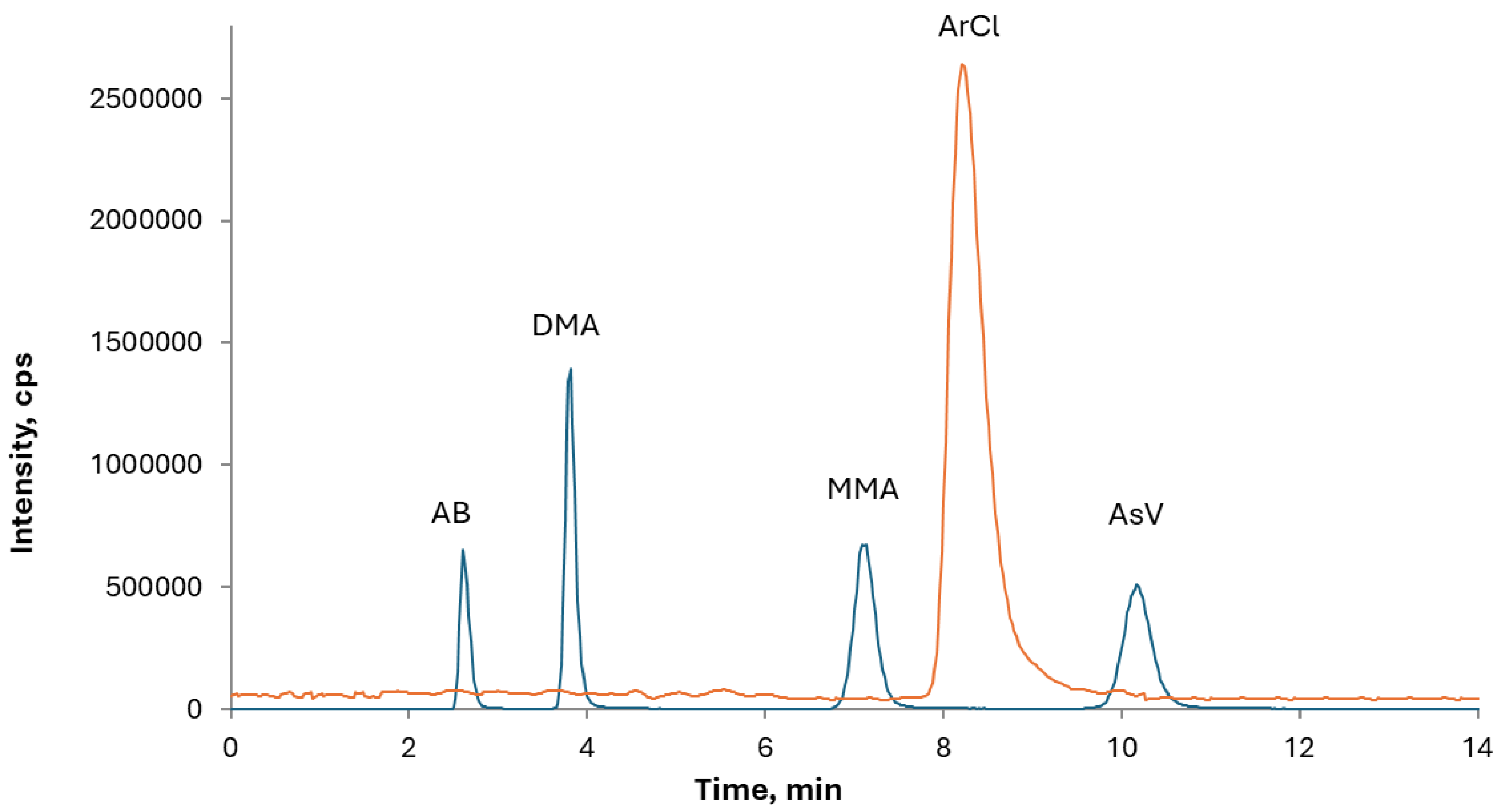

The optimal chromatographic conditions were established by verifying the sufficient separation of the arsenical species of interest, namely AB, MMA, DMA, and As(V). The absence of coelution of arsenate and chloride peaks was verified to avoid possible interference from the polyatomic ion

40Ar

35Cl

+ on

75As, and the standard mode determination was chosen for speciation analysis. As shown in

Figure 1, the chloride peak is well separated from iAs meaning that potential interference from ArCl can be disregarded.

The limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) for iAs were calculated using the 3 σ and 10 σ criterion, respectively, where σ is the standard deviation of ten independent extraction blank analyses spiked at a level of 0.5 μg kg-1. The calculated LOQs of the method were 0.7 and 1.5 μg kg-1 for fresh and dried samples, respectively. Similarly, for fresh samples, the LOQs of the method for DMA and MMA were 0.5 and 0.4 μg kg-1, respectively.

Precision was assessed in terms of repeatability and intermediate precision (within-laboratory reproducibility) by determining within-day and between-day (2 days) relative standard deviations (RSDs) [

19,

20] from six independent replicates at three levels of concentration. In particular, two rice-based CRMs, namely ERM-BC211 and NMIJ CRM 7532-a, as well as a sample of rice drink spiked at level of interest, i.e. the maximum level for iAs in non-alcoholic rice-based drinks set out in Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/915, were used. The repeatability and intermediate precision, expressed as RSD ranged from 0.7 to 4.7 % and from 2.2 to 8.1 %, respectively. The validation parameters for iAs comply with the requirements laid down in Regulation (EC) No 333/2007 [

21]. In particular, the LOD and LOQ values for rice-based beverages are well below the maximum values permitted by the Regulation (i.e., 9 μg kg

-1 and 30 μg kg

-1 for LOD and LOQ, respectively). Furthermore, for both repeatability and intermediate precision, the HorRat ratio—defined as the ratio between the observed RSD and the RSD calculated using the Horwitz equation— is well below 2, confirming values lower than the limit required by the Regulation.

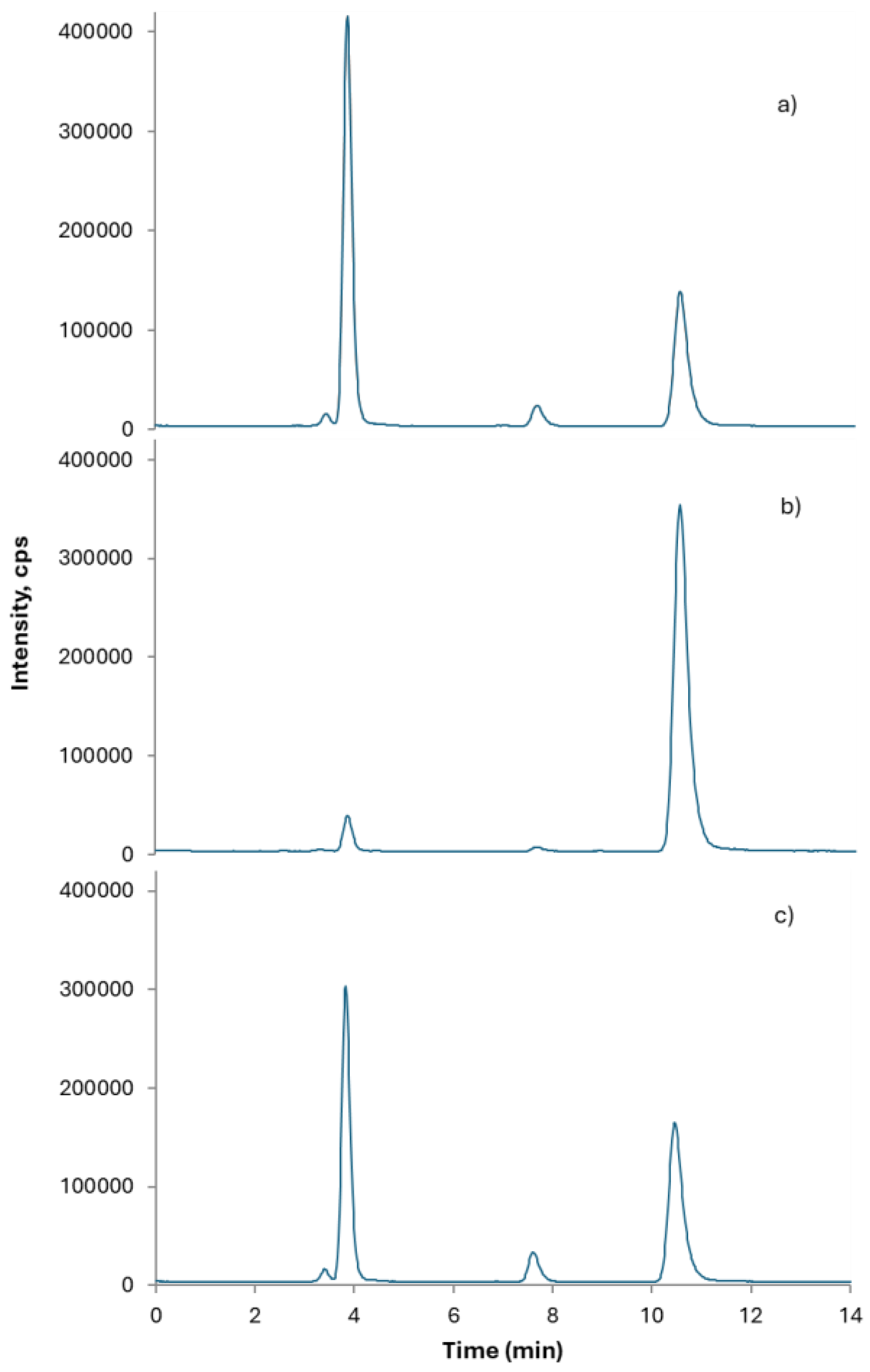

Rice CRMs (NIST SRM 1568b, ERM-BC211 and NMIJ CRM 7532-a) were used throughout the study for trueness assessment. The chromatographic profiles obtained for the CRMs are presented in

Figure 2. The results showed good agreement with the certified values for both tAs and iAs. Results for MMA and DMA were also reported revealing good accordance with certified values, despite the relatively low certified concentration values for MMA (

Table 2). Mass balance, as ratio of the sum of As species in the extract to tAs, was also reported as a measure of both extraction efficiency and column recovery. Spiking/recovery experiments were also performed using a rice drink sample spiked with 20 μg kg⁻¹ iAs to evaluate trueness for iAs in the matrix at the level of interest [

19,

20].

3.2. Occurence of Inorganic Arsenic and Organo-Arsenic Species in Rice-Based Beverages

The present study investigates the contamination pattern of iAs and oAs species in rice-based beverages. The sampling strategy reflects the products currently available on the Italian market and was designed to provide a representative picture of the situation across the entire country. Overall, 25 samples were analyzed, including 16 samples containing rice as sole ingredient, 2 brown rice drinks, 4 rice-and-coconut drinks, 2 rice-and-almond drinks, and 1 beverage containing rice, hazelnut, and cocoa.

Table 3 reports the concentration values of tAs, iAs and oAs, together with the rice content (%) and the percentage of iAs compared with tAs. In addition, mean, median and range (min-max) concentrations are reported.

Overall, the concentrations observed were homogenous, and iAs was the most representative species, with quantifiable levels in 100% of the samples. The mean iAs and DMA concentrations were found to be 15 µg kg

-1 and 3 µg kg

-1, respectively. MMA was found at low levels in six samples, consistent with its molecular instability (it is gradually converted to DMA, which is more stable) across vegetable food matrices, as well as with its limited translocation into rice from soil [

22]. Notably, one sample of rice and almond drink exhibited a higher content of oAs (28 and 9 µg kg

-1 of DMA and MMA, respectively).

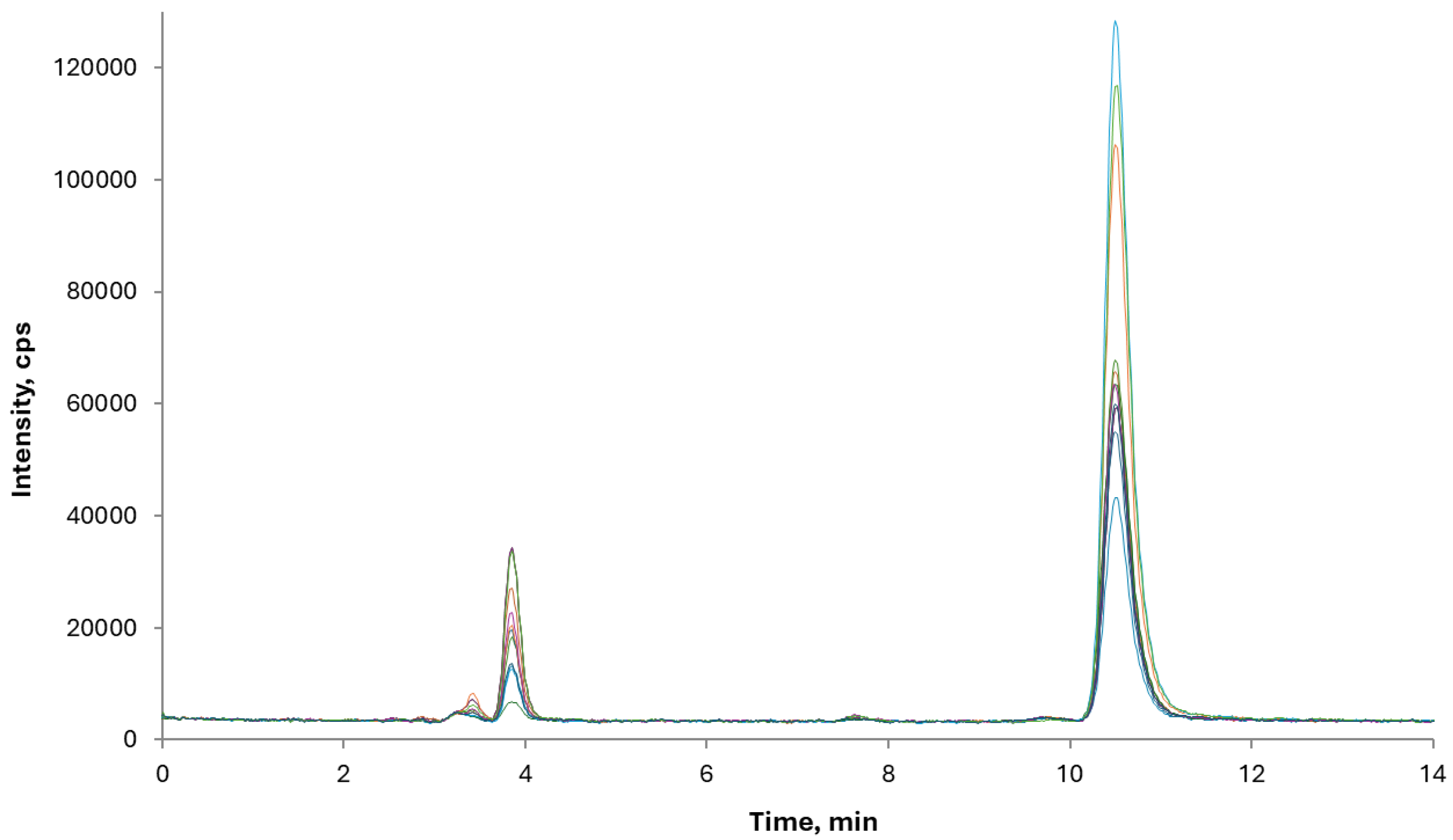

The merged chromatographic profiles of these samples are reported in

Figure 3. None of the samples exceeded the maximum level (30 µg kg

-1) for iAs set in point 3.4.1.6 of Annex I of Regulation (EU) No 915/2023, for the food category “Non-alcoholic rice-based drinks” [

12]. Although no maximum limits have been established for DMA and MMA, these compounds received particular attention at the recent meeting of the Joint Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)/World Health Organization (WHO) Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) in October 2025, in relation to new toxicological evidence. Indeed, the Committee recommended the collection of additional occurrence and dietary exposure data [

23].

In this reshaping context, the occurrence data generated in this study are of particular significance when compared with other studies on this matrix. Meharg et al. determined DMA, MMA and iAs in rice milk produced in European countries [

24]; Pedron et al. provided speciation results for rice milk samples produced in Italy [

25]; dos Santos et al. analyzed rice milk powder from Brazil [

26]; Guillod-Magnin et al. determined iAs in rice drink from Switzerland [

27]; Munera-Picazo et al. reported results for rice milk from Spain [

28]; Signes-Pastor et al. provided information about tAs and arsenic species a Japanese fermented sweet rice drink, amazake [

29].

Despite the apparent restricted number of analyzed samples, the results are comparable with other studies carried out worldwide (see

Table 4). Furthermore, the present study encompasses the largest number of samples analyzed to date, with the exception of those considered in the most recent EFSA report. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that this report is characterized by a high proportion of left-censored data (42%) for iAs, as well as a limited number of samples (n = 14) in which both iAs and tAs were quantitatively determined [

7].

3.3. Dietary Exposure and Risk Characterization

Dietary exposure to iAs from rice-based beverages was estimated by combining the occurrence data generated in this study with individual consumption records from the most recent Italian national dietary surveys (IV SCAI CHILD and IV SCAI ADULT). Consumption levels were low in the overall population but showed clear differences between all subjects and consumers only, reflecting the niche consumption of these products (

Table 5).

Toddlers were by far the highest consumers among those reporting intake (18.0 g/kg bw per day), followed by other children (8.51 g/kg bw per day), whereas adolescents, adults and the elderly showed markedly lower consumption. Although the number of consumers in the Italian survey is generally low, the average consumption of rice drinks among Italian consumers by the age classes is comparable to that of consumers in the other European surveys. For Italian adolescent consumers, the consumption of rice-based drinks is slightly higher than in other European countries but that does not have a substantial impact on the exposure assessment.

Based on these consumption levels and the measured mean concentration of iAs in rice drinks (15 µg kg

-1), chronic exposure estimates for the total population ranged from 0.0001 µg/kg bw per day in the elderly to 0.0042 µg/kg bw per day in toddlers (

Table 6). Among consumers only, the exposure increased considerably, reaching 0.27 µg/kg bw per day for toddlers and 0.13 /kg bw per day for other children. Although these values remain lower than the overall chronic dietary exposure to iAs estimated by EFSA for Italy (0.03–0.61 µg/kg bw per day, depending on age group), they represent a non-negligible contribution for regular consumers, particularly for younger age classes disproportionately reliant on plant-based beverages.

Risk characterization was carried out using the MOE approach, applying the RP (0.06 µg/kg bw per day) selected by EFSA from human epidemiological data. In the total population, MOE values ranged from 14 in toddlers to 598 in the elderly, mirroring their respective consumption levels. Among consumers only, the MOE decreased substantially in the youngest age groups, reaching critical values in toddlers (MOE = 0.2) and other children (MOE = 0.5), raising a potential health concern.

These data should also be interpreted in the broader context of evolving dietary habits. The increasing diversification of food choices, including the rise in consumption of plant-based beverages and products marketed for specific nutritional needs, may significantly influence exposure patterns to arsenic. As the intake of plant-derived commodities continues to expand, the relative contribution of rice drinks to total iAs exposure may become more relevant, particularly for children, vegans/vegetarians and flexitarians, individuals with coeliac disease or gluten intolerance, and other groups relying on milk alternatives [

35].

Previous EFSA assessments noted that the impact of rice drinks on overall dietary exposure was likely underestimated due to the high proportion of left-censored data (42%) and the uncertainty associated with substitution methods (LB–UB differences), combined with limited consumption information for these food items. The present dataset contributes to reducing this uncertainty by providing robust, uncensored occurrence data and population-specific exposure estimates.

To sum up, consumer exposure to iAs in food remains a health concern, according to EFSA latest risk assessment report. The results of this study confirm that rice-based beverages, although contributing modestly to total population exposure, may pose a more meaningful risk for specific subgroups—particularly toddlers and young children with high consumption patterns. In these cases, limiting the intake of rice drinks and diversifying the choice of plant-based beverages may help reduce exposure to iAs.

5. Conclusions

This study provides an updated overview of iAs and oAs occurring in rice-based beverages available on the Italian market. The analytical method, developed and validated in accordance with UNI EN 16802:2016, proved suitable for the simultaneous determination of iAs, AB, DMA, and MMA, while also demonstrating sufficient sensitivity to generate robust occurrence data without left censoring for iAs. The contamination levels were found to be homogeneous across products, with iAs representing the predominant species. Furthermore, all samples complied with the current European maximum level for non-alcoholic rice-based drinks.

When combined with recent Italian consumption data, these occurrence data enabled a general population and age-specific assessment of dietary exposure. While rice-based beverages contribute minimally to overall population exposure, intake estimates for habitual consumers, especially during early childhood, indicate narrow margins of exposure, suggesting potential risk. This finding lends further support to the mounting concern for vulnerable subgroups, who may consume rice drinks as substitutes for milk. The increasing diversification of dietary habits, particularly the expanding use of plant-based beverages among individuals with specific nutritional needs, points out the need for continuous monitoring of iAs in these products. Finally, continued efforts in analytical method optimization, database improvement, consumer guidance and effective risk communication policies will contribute to more accurate exposure and risk assessment, and, more importantly, better protection of public health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization. M.D. and A.S.; methodology. A.C.T; software. M.D.; validation. A.C.T.; formal analysis. F.V.; investigation. M.D., A.C.T., T.D., A.S.; resources F.V.; data curation. A.C.T.; writing—original draft preparation. M.D., T.D.; writing—review and editing. M.D., T.D., A.S.; visualization. F.M.; supervision. P.S., A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AB |

Arsenobetaine |

| AC |

Arsenocholine |

| As |

Arsenic |

| As(III) |

Arsenite |

| As(V) |

Arsenate |

| BMDL05 |

Benchmark Dose Lower Confidence Limit for a 5% increase in response |

| bw |

Body weight |

| CRM |

Certified Reference Material |

| DMA |

Dimethylarsinic acid |

| EC |

European Commission |

| EFSA |

European Food Safety Authority |

| FAO |

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| FoodEx2 |

Food classification and description system developed by EFSA |

| HPLC |

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| HPLC-ICP-MS |

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with Inductively Coupled |

| |

Plasma Mass Spectrometry |

| IARC |

International Agency for Research on Cancer |

| ICP-MS |

Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry |

| iAs |

Inorganic arsenic |

| JECFA |

Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives |

| KED |

Kinetic Energy Discrimination |

| LB |

Lower Bound |

| LOD |

Limit of Detection |

| LOQ |

Limit of Quantification |

| MB |

Middle Bound |

| MOE |

Margin of Exposure |

| MMA |

Monomethylarsonic acid |

| oAs |

Organic arsenic |

| RP |

Reference Point |

| RSD |

Relative Standard Deviation |

| tAs |

Total arsenic |

| UB |

Upper Bound |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- Muehe, E.M.; Wang, T.; Kerl, C.F.; Planer-Friedrich, B.; Fendorf, S. Rice Production Threatened by Coupled Stresses of Climate and Soil Arsenic. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4985. [CrossRef]

- Cubadda, F.; Aureli, F.; D’Amato, M.; Raggi, A.; Turco, A.C.; Mantovani, A. Speciated urinary arsenic as a biomarker of dietary exposure to inorganic arsenic in residents living in high-arsenic areas in Latium, Italy. Pure Appl. Chem. 2012, 84, 203–214. [CrossRef]

- IARC Arsenic, Metals, Fibres and Dusts; International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2012; ISBN 978-92-832-1320-8.

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Scientific Opinion on Arsenic in Food. EFSA J. 2009, 7, 1351. [CrossRef]

- D’Amore, T.; Miedico, O.; Pompa, C.; Preite, C.; Iammarino, M.; Nardelli, V. Characterization and Quantification of Arsenic Species in Foodstuffs of Plant Origin by HPLC/ICP-MS. Life 2023, 13, 511. [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); Schrenk, D.; Bignami, M.; Bodin, L.; Chipman, J.K.; del Mazo, J.; Grasl-Kraupp, B.; Hogstrand, C.; Hoogenboom, L. (Ron); Leblanc, J.-C.; et al. Update of the Risk Assessment of Inorganic Arsenic in Food. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e8488. [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); Arcella, D.; Cascio, C.; Gómez Ruiz, J.Á. Chronic Dietary Exposure to Inorganic Arsenic. EFSA J. 2021, 19, e06380. [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.N.; Villada, A.; Deacon, C.; Raab, A.; Figuerola, J.; Green, A.J.; Feldmann, J.; Meharg, A.A. Greatly Enhanced Arsenic Shoot Assimilation in Rice Leads to Elevated Grain Levels Compared to Wheat and Barley. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 6854–6859. [CrossRef]

- Signes, A.; Mitra, K.; Burló, F.; Carbonell-Barrachina, A.A. Effect of Cooking Method and Rice Type on Arsenic Concentration in Cooked Rice and the Estimation of Arsenic Dietary Intake in a Rural Village in West Bengal, India. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2008, 25, 1345–1352. [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.N.; Price, A.H.; Raab, A.; Hossain, S.A.; Feldmann, J.; Meharg, A.A. Variation in Arsenic Speciation and Concentration in Paddy Rice Related to Dietary Exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 5531–5540. [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Management of Left-Censored Data in Dietary Exposure Assessment of Chemical Substances. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1557. [CrossRef]

- European Commission Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/915 of 25 April 2023 on Maximum Levels for Certain Contaminants in Food and Repealing Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 (Text with EEA Relevance); 2025;

-

UNI EN 16802:2016 Foodstuffs - Determination of Elements and Their Chemical Species - Determination of Inorganic Arsenic in Foodstuffs of Marine and Plant Origin by Anion-Exchange HPLC-ICP-MS.;

-

UNI EN 17851:2023 Foodstuffs - Determination of Elements and Their Chemical Species - Determination of Ag, As, Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Mn, Mo, Ni, Pb, Se, Tl, U and Zn in Foodstuffs by Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) after Pressure Digestion.;

- Aida, T.; Cinzia, L.D.; Raffaela, P.; Laura, D.; Lorenza, M.; Stefania, S.; Deborah, M.; Javier, C.A.F.; Marika, F.; Giovina, C. Italian National Dietary Survey on Adult Population from 10 up to 74 Years Old – IV SCAI ADULT. EFSA Support. Publ. 2022, 19, 7559E. [CrossRef]

- CREA; Turrini, A.; Cinzia, L.D.; Raffaela, P.; Laura, D.; Lorenza, M.; Marika, F.; Giovina, C.; Deborah, M. Italian National Dietary Survey on Children Population from Three Months up to Nine Years Old – IV SCAI CHILD. EFSA Support. Publ. 2021, 18, 7087E. [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); Salfinger, A.; Gibin, D.; Niforou, K.; Ioannidou, S. FoodEx2 Maintenance 2022. EFSA Support. Publ. 2023, 20, 7900E. [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Opinion of the Scientific Committee on a Request from EFSA Related to A Harmonised Approach for Risk Assessment of Substances Which Are Both Genotoxic and Carcinogenic. EFSA J. 2005, 3, 282. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.; Ellison, S.L.R.; Wood, R. Harmonized Guidelines for Single-Laboratory Validation of Methods of Analysis: (IUPAC Technical Report).

- Cantwell, H. The Fitness for Purpose of Analytical Methods (2025);

- European Commission Commission Regulation (EC) No 333/2007 of 28 March 2007 Laying down the Methods of Sampling and Analysis for the Official Control of the Levels of Lead, Cadmium, Mercury, Inorganic Tin, 3-MCPD and Benzo(a)Pyrene in Foodstuffs (Text with EEA Relevance ); 2007; Vol. 088;

- Muehe, E.M.; Wang, T.; Kerl, C.F.; Planer-Friedrich, B.; Fendorf, S. Rice Production Threatened by Coupled Stresses of Climate and Soil Arsenic. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4985. [CrossRef]

- FAO; WHO One-Hundred-and-First Meeting - Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA);

- Meharg, A.A.; Deacon, C.; Campbell, R.C.J.; Carey, A.-M.; Williams, P.N.; Feldmann, J.; Raab, A. Inorganic Arsenic Levels in Rice Milk Exceed EU and US Drinking Water Standards. J. Environ. Monit. 2008, 10, 428. [CrossRef]

- Pedron, T.; Segura, F.; Silva, F.; Souza, A.; Maltez, H.; Batista, B. Essential and Non-Essential Elements in Brazilian Infant Food and Other Rice-Based Products Frequently Consumed by Children and Celiac Population. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2016, 49, 78–86. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, G.M.; Pozebon, D.; Cerveira, C.; de Moraes, D.P. Inorganic Arsenic Speciation in Rice Products Using Selective Hydride Generation and Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (AAS). Microchem. J. 2017, 133, 265–271. [CrossRef]

- Guillod-Magnin, R.; Brüschweiler, B.J.; Aubert, R.; Haldimann, M. Arsenic Species in Rice and Rice-Based Products Consumed by Toddlers in Switzerland. Food Addit. Contam. Part Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 2018, 35, 1164–1178. [CrossRef]

- Munera-Picazo, S.; Burló, F.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A. Arsenic Speciation in Rice-Based Food for Adults with Celiac Disease. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2014, 31, 1358–1366. [CrossRef]

- Signes-Pastor, A.J.; Deacon, C.; Jenkins, R.O.; Haris, P.I.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A.; Meharg, A.A. Arsenic Speciation in Japanese Rice Drinks and Condiments. J. Environ. Monit. 2009, 11, 1930–1934. [CrossRef]

- Permigiani, I.S.; Vallejo, N.K.; Hasuoka, P.E.; Gil, R.A.; Romero, M.C. Arsenic Speciation Analysis in Cow’s Milk and Plant-Based Imitation Milks by HPLC-ICP-MS. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 126, 105898. [CrossRef]

- da Rosa, F.C.; Nunes, M.A.G.; Duarte, F.A.; Flores, É.M. de M.; Hanzel, F.B.; Vaz, A.S.; Pozebon, D.; Dressler, V.L. Arsenic Speciation Analysis in Rice Milk Using LC-ICP-MS. Food Chem. X 2019, 2, 100028. [CrossRef]

- Cano-Lamadrid, M.; Munera-Picazo, S.; Burgos-Hernández, A.; Burló, F.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A. Inorganic and Total Arsenic Contents in Rice and Rice-Based Foods Consumed by a Potential Risk Subpopulation: Sportspeople. J. Food Sci. 2016, 81, T1031-7. [CrossRef]

- González, N.; Calderón, J.; Rúbies, A.; Bosch, J.; Timoner, I.; Castell, V.; Marquès, M.; Nadal, M.; Domingo, J.L. Dietary Exposure to Total and Inorganic Arsenic via Rice and Rice-Based Products Consumption. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 141, 111420. [CrossRef]

- Leclercq, C.; Arcella, D.; Piccinelli, R.; Sette, S.; Le Donne, C.; Turrini, A.; INRAN-SCAI 2005-06 Study Group The Italian National Food Consumption Survey INRAN-SCAI 2005-06: Main Results in Terms of Food Consumption. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 2504–2532. [CrossRef]

- FAO Thinking about the Future of Food Safety. A Foresight Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022; ISBN 978-92-5-135783-5.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).