1. Introduction

Diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) are one of the most prevalent and debilitating consequences of diabetes, which account for 60-75.5% of all lower extremity amputations (LEA) and cost ~

$9-12 billion in the annual care in the United States alone [

1]. The staggering number of ulcers that progress to LEA underscores the inadequacy of current treatments and the urgent need for innovative approaches. Infection is a major co-morbidity and a driver of chronic state and LEA in DFUs [

1]. Unlike chronic ulcers that are locked in a state of persistent and non-resolving inflammation [

2,

3], inflammatory responses are significantly diminished during the acute phase of healing early after injury, making diabetic wounds susceptible to infection with pathogenic bacteria such as

Pseudomonas aeruginosa which further exacerbate tissue damage and impair tissue repair through the production of their virulence factors that can further dampen inflammatory responses and adversely affect a multitude of cellular processes underlying tissue repair [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

Neutrophils are the first line of defense against invading pathogens, immediately migrating to the site of injury to facilitate bacterial clearance by phagocytosis, the generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, antimicrobial peptides, and the development of neutrophil extracellular traps [

12,

13]. However, antimicrobial and bactericidal functions are impaired in neutrophils under hyperglycemia and diabetic conditions, rendering them ineffective to control infection [

14]. In addition, neutrophils isolated from the blood of diabetic patients exhibit impaired chemotactic responses, leading to reduced neutrophil trafficking into the wound and toward infection during the early stages of diabetic wound healing. This neutrophil dysfunction is attributed to impaired signaling through the formyl peptide receptor (FPR), which normally mediates the initial wave of neutrophil trafficking to injury and infection [

4,

15]. Importantly, some auxiliary chemokine receptors, such as CCR1, remain functional under diabetic conditions; however, they are not activated in diabetic wounds in the early stages due to low expression of their endogenous ligands [

4,

6].

There are currently no approved biologic therapies that target infection in diabetic wounds. The only approved biologic therapy for DFUs is Becaplermin gel (0.01% rhPDGF-BB). However, Becaplermin has limited efficacy in stimulating healing and is not effective against infection [

16,

17]. Antibiotics are routinely included in the management of diabetic ulcers [

18,

19], but they are linked to emergence of antibiotic resistance, toxicity, and interference with tissue repair [

20,

21,

22]. These reports underscore the urgent need for novel therapeutics (preferably antibiotic-free) to address infection in diabetic wounds. We have previously demonstrated that topical treatment with CCL3/MIP-1α immunomodulator reduced infection by >99% and improved healing in diabetic mice by bypassing impaired FPR signaling and restoring timely neutrophil trafficking, highlighting its potential in diabetic wound care [

4]. However, regulatory approval of novel biologics requires comprehensive evaluation of their efficacy and toxicity in relevant animal models [

23,

24].

The present study investigated the toxicity profile of topical CCL3 wound therapy in diabetic mice, including physiological monitoring, biochemical and hematological analyses, and histopathological assessment of major organs. Our data demonstrate that topical CCL3 treatment was well tolerated and did not result in any cytotoxic effects. Intriguingly, it resulted in modest yet significant systemic benefits, including hepatoprotection and reduced inflammation. These results provide essential insights into the immunological safety and systemic tolerability of CCL3 therapy in diabetic wound models, supporting its advancement toward clinical application.

2.Material and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Phosphate buffer saline (PBS) pH 7.4 (Gibco™), recombinant mouse CCL3/mip-1 alpha protein (Biotechne/R&D systems), ketamine, hydrochloride, xylazine, buprenorphine, sterile alcohol prep pads (Fisherbrand) biopsy punch (Acuderm, inc), 10% neutral buffered formalin (Epredia), xylene (Merck), hematoxylin (Epredia), eosin (Epredia™), Invitrogen mouse CRP ELISA kit, Invitrogen mouse IgG1 uncoated ELISA kit, Invitrogen mouse IgE ELISA kit.

2.2. Animals and Grouping

We used 8-week-old B6.BKS(D)-Lepr^db/J (db/db) obese diabetic mice (strain #00697; The Jackson Laboratory) as animal model in this study [

25]. Heterozygous (db/+) mice served as normoglycemic controls. All animals were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory and housed in the University of California Davis Health Animal Vivarium. Mice were maintained under controlled environmental conditions (temperature: 22 ± 2 °C; relative humidity: 50 ± 10%) with a 12 h light/dark cycle and ad libitum access to standard chow and water. All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC, Protocol #24063).

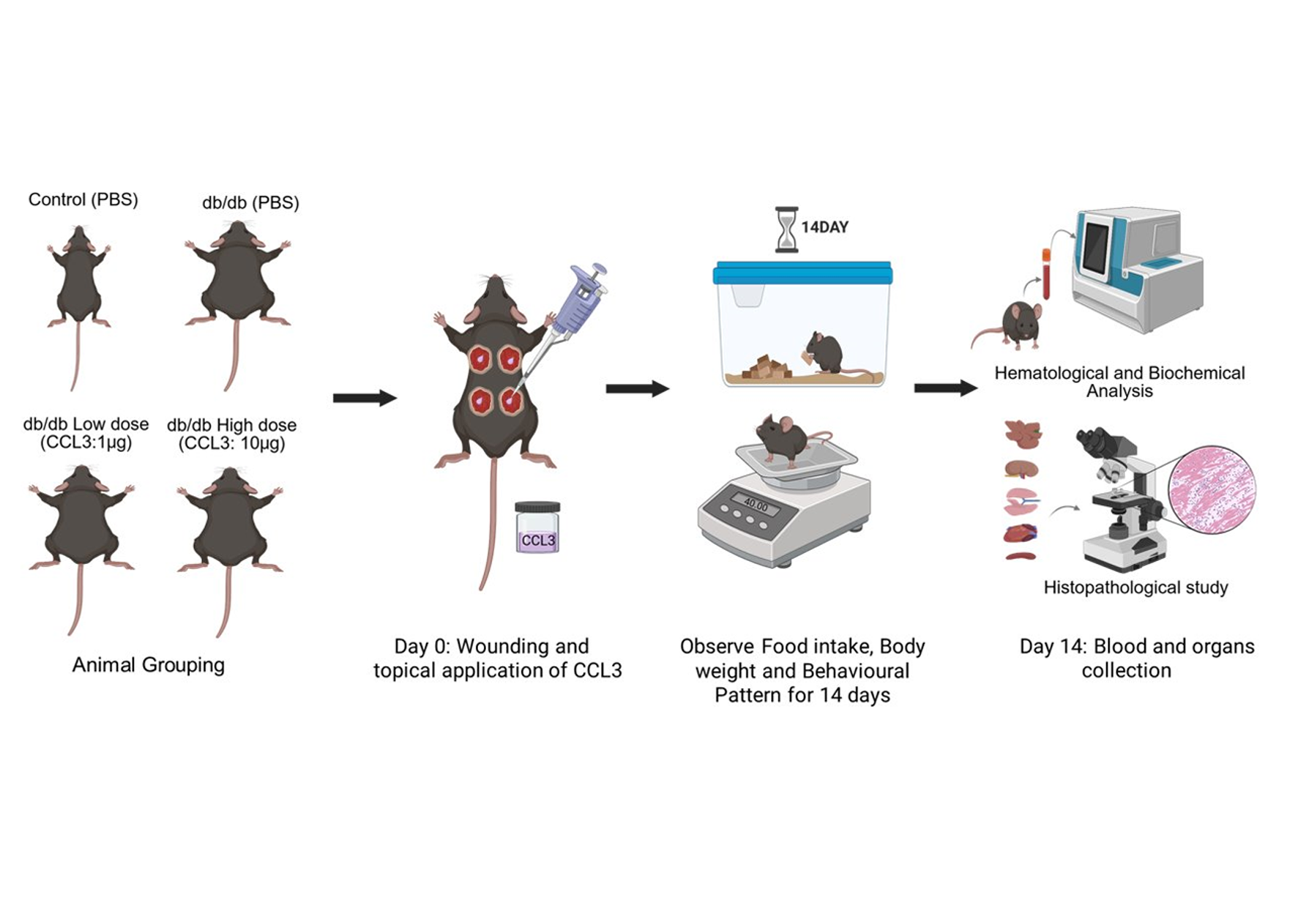

Mice were surgically wounded by 5-mm sterile biopsy punches as described [

5,

26]. They were then randomly assigned to four experimental groups (6 mice/group): 1) control (db/+ receiving PBS); 2) diabetic (db/db receiving PBS); 3) diabetic treated with CCL3 at low dose (1 µg per wound); And 4) diabetic treated with CCL3 at high dose (10 µg per wound). The schematic diagram of the research strategy is depicted in

Figure 1. All wounds in the same mouse received the same treatment to prevent immune confusion that has been reported [

27].

2.3. Wounding and Treatment

One day prior to the wounding (day -1), the dorsal hair was removed with an electric trimmer to expose the skin surface. On day 0, mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg), followed by analgesia with buprenorphine (0.01 mg/kg) for pain management. The dorsal skin was sanitized by wiping with a sterile alcohol pre pad, and full-thickness excisional wounds (5-mm diameter) were made using a sterile biopsy punch. Following wounding, PBS or CCL3 (1 µg or 10 µg per wound) was applied topically based on group allocation. Mice were divided into control and treatment groups, wounded, and then treated with PBS or CCL3 topically (

Figure 1). They were also observed every day for changes in behavior, body weight, and food consumption. To ascertain the systemic safety profile of CCL3 treatment, main organs were histologically evaluated, and blood was studied for hematological and biochemical markers at the end of the trial.

2.4. Monitoring and Clinical Observations

Following treatment, mice were observed for survival, movement, posture, and any signs of discomfort. Body weight and food intake were measured at the start of the trial and at regular intervals during the 14-day period. Daily observations were also made to note any behavioral changes as described [

28] that could suggest systemic toxicity associated with CCL3 treatment.

2.5. Immunological, Hematological and Biochemical Analysis

To assess the systemic safety profile of CCL3 treatment in diabetic mice, immunological, hematological, and biochemical parameters were evaluated using established procedures [

29]. On the 14 day post-injury and treatment, the mice were anesthetized, and blood was collected via cardiac puncture. For plasma collection, blood was drawn into BD Vacutainer™ collection tubes containing EDTA as an anticoagulant and centrifuged at 1000×

g for 10 min at 8 °C, after which the supernatant plasma was collected. For serum separation, blood was collected in BD Microtainer™ serum separator tubes with gel, allowed to clot at room temperature for 30 min, and centrifuged at 4000×

g for 10 min at room temperature to obtain serum [

29]. Plasma and serum samples were prepared and sent to the Comparative Pathology Laboratory at the University of California Davis, School of Veterinary Medicine for extensive hematological and biochemical testing. Red and white blood cell counts (RBC & WBC), hemoglobin (Hb), platelet counts, and differential leukocyte distribution (monocyte, eosinophil, and basophil) were all analyzed using an automated hematology analyzer (Hemavet 950FS). The serum biochemistry was analyzed by Roche Cobas Integra 400 Plus, for indicators of liver and kidney functions including, Alanine Transaminase (ALT), Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST), Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP), total bilirubin, Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, protein levels (total protein and albumin), electrolytes, and glucose as described [

30].

Furthermore, serum samples were analyzed for immunological parameters, including inflammatory and allergy markers such as, C-reactive protein (CRP), Immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1), and Immunoglobulin E (IgE), using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) methodology.

2.6. Histopathological Analysis

Histopathological examination was used as a gold-standard method to visualize and confirm whether CCL3 treatment altered tissue architecture or caused signs of organ toxicity, providing direct insight beyond hematological and biochemical measurements. Following blood collection, the mice were euthanized, and key organs such as the liver, kidney, spleen, heart, and pancreas were taken and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. The organs were processed, paraffin-embedded, sectioned at 4-5 µm, and stained with Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E). Histological evaluation was performed under light microscopy, and semi-quantitative scoring was utilized to quantify necrosis, inflammation, and tissue structure [

31]. Semi-quantitative scoring for necrosis and inflammation was performed according to previously published criteria [

32]. Necrosis was graded on a scale of 0–5: 0 = no necrosis, 1 = minimal (<5% tissue), 2 = mild (5–20%), 3 = moderate (21–40%), 4 = severe (41–60%), and 5 = very severe (>60%). Inflammation was similarly graded on a scale of 0–5: 0 = no infiltrates, 1 = minimal infiltration (few scattered cells), 2 = mild (<10% tissue), 3 = moderate (10–30%), 4 = severe (31–50%), and 5 = very severe (>50%). Necrosis was graded on a scale of 0–5: 0 = no necrosis, 1 = minimal (<5% tissue), 2 = mild (5–20%), 3 = moderate (21–40%), 4 = severe (41–60%), and 5 = very severe (>60%). Inflammation was similarly graded on a scale of 0–5: 0 = no infiltrates, 1 = minimal infiltration (few scattered cells), 2 = mild (<10% tissue), 3 = moderate (10–30%), 4 = severe (31–50%), and 5 = very severe (>50%).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

One-way ANOVA was used to compare groups, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison post hoc test. Statistical significance was determined as p < 0.05. Statistical differences in the figures are given as p ≤ 0.05 (*), p ≤ 0.01 (**), p ≤ 0.001 (***), p ≤ 0.0001 (****) and p ≥ 0.05 (not significant). All analyses were carried out with GraphPad Prism software (version 10.4.2). All results were reported as mean ± SEM. Of note, we evaluated normality and variance homogeneity for all datasets included in parametric analyses before proceeding to student’s t test and one way ANOVA by using GraphPad Prism (version 10.4.2). Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test (n < 30), and homogeneity of variance was evaluated using the Brown-Forsythe test (n > 2). In all cases, the data met these assumptions.

3. Results

The experimental design is illustrated in

Figure 1. Briefly, mice were surgically wounded using 5-mm sterile biopsy punches as previously described [

5,

26,

33]. They were then randomly assigned to four experimental groups (6 mice per group): (1) control (db/+ receiving PBS); (2) diabetic (db/db receiving PBS); (3) diabetic treated with low-dose CCL3 (1 µg per wound); and (4) diabetic treated with high-dose CCL3 (10 µg per wound). Food intake, body weight, and any signs of mortality or behavioral changes were monitored over a 14-day period. On day 14, mice were euthanized, and their blood and major organs were collected for biochemical, immunological, and histological analyses to evaluate the systemic effects of CCL3 treatment on overall health.

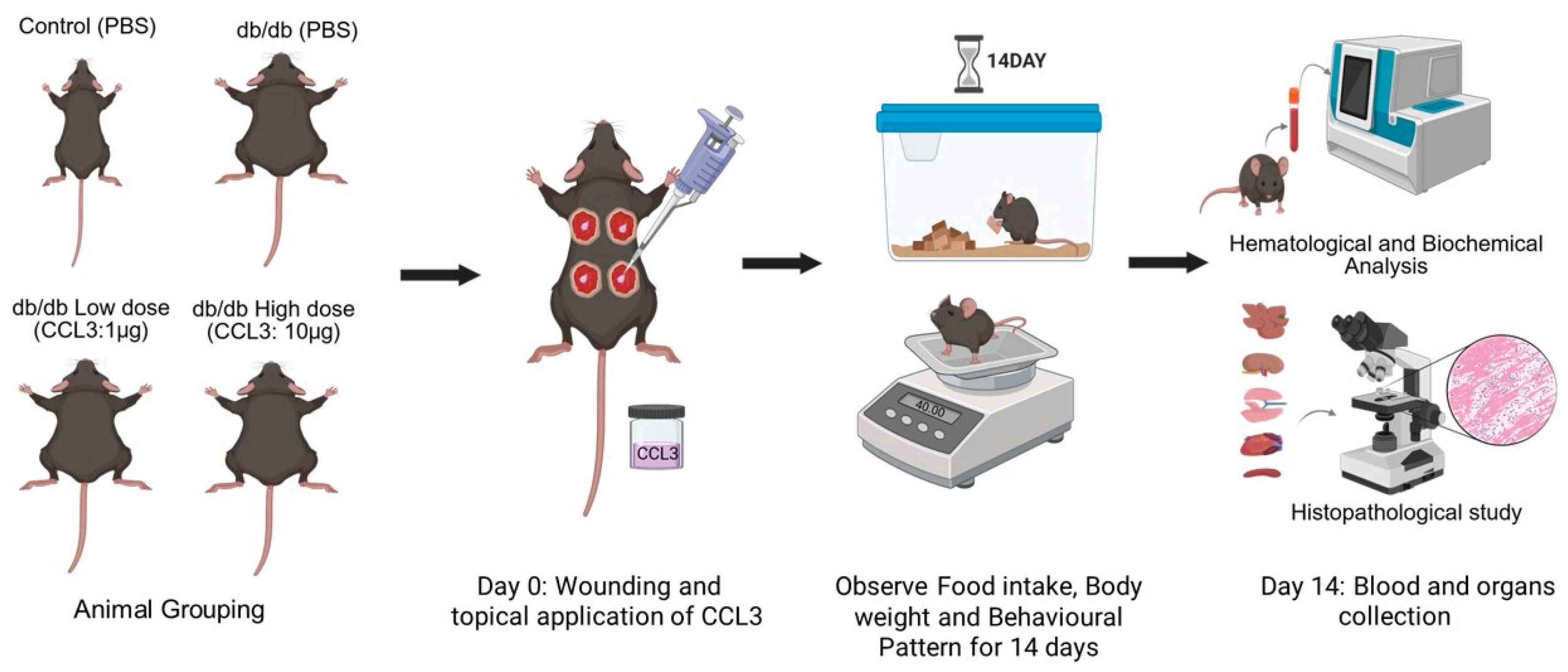

3.1. Physiological and Behavioral Monitoring Following CCL3 Treatment

Following wound surgery on day 0, mice in all groups showed reduced mobility and decreased grooming behavior, which is consistent with acute post-surgical discomfort [

34,

35]. However, by day 2, behavioral patterns had recovered, and the animals resumed normal movement and feeding, with no further abnormalities noted. Nondiabetic control mice (db/+) consumed about 3-4 g of food per day, whereas diabetic mice (db/db) consumed significantly higher amounts (6.5-8 g) per day, which is consistent with increased appetite in db/db obese diabetic mice [

36]. Of note, food intake was temporarily reduced in all groups following surgery on days 0 and 1, but this reduced appetite for food was temporary, and by day 2 the animals had resumed their normal eating behavior (

Figure 2A). Compared to db/+ nondiabetic control mice, db/db diabetic mice continued to consume more food throughout the duration of this study regardless of their treatments. PBS-treated and CCL3-treated db/db mice did not differ significantly at either dose, indicating that topical CCL3 at 1 µg and 10 µg had no effect on feeding behavior. Throughout the study, db/db mice in all groups weighed significantly more (40-50 g) than nondiabetic db/+ mice (20-30 g) controls at baseline (day 0) (p < 0.0001). Despite loss of appetite on day 1, mice did not experience any significant weight loss following wounding procedure and their weights remained constant throughout this 14-day period (

Figure 2B). Notably, the db/db groups treated with PBS and CCL3 did not differ significantly in their eating behavior or weight, indicating that CCL3 treatments were well tolerated and did not change metabolic status in mice (

Figure 2B).

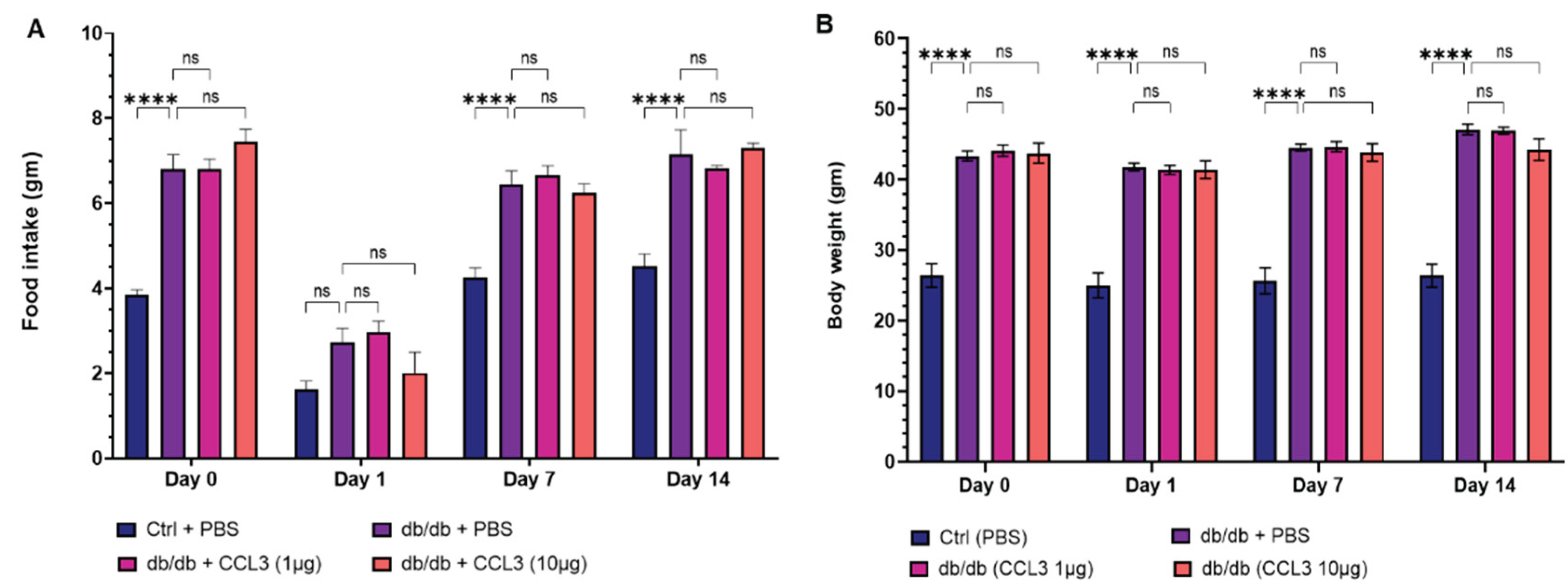

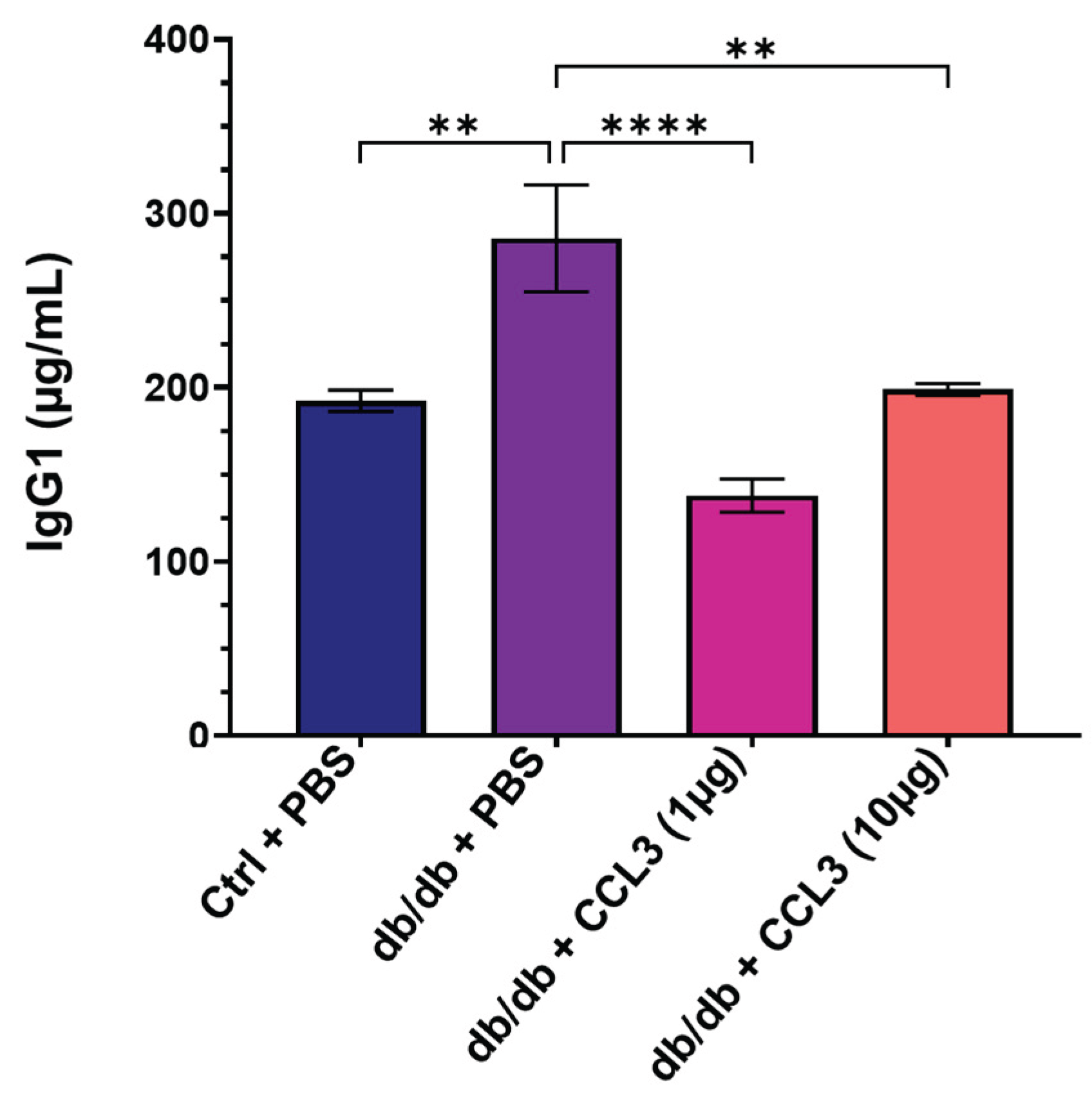

3.2. CCL3 Therapy Reduces Serum IgG1 in Diabetic Mice

We assessed serum biochemistry, hematology, immunological parameters, and circulating biomarkers in day 14 blood to determine whether CCL3 treatment adversely altered immune responses or caused systemic toxicity. In terms of immunological parameters associated with systemic inflammation, compared to nondiabetic control group, diabetic mice treated with PBS (mock) exhibited approximately 48.5% higher serum IgG1 levels (285.75 ± 86.27 µg/mL vs. 192.45 ± 13.51 µg/mL,

p < 0.01); 125% higher IgE (207.35 ± 57.64

vs. 92.29 ± 22.03,

p <0.01); and 335% higher C-reactive protein (CRP) levels (8.14 ± 1.86

vs. 1.83 ± 0.33,

p <0.001) (

Table 1). These findings are consistent with clinical reports showing that diabetic patients exhibit elevated serum levels of IgG1, IgE, and CRP, associated with increased risks of kidney nephropathy, allergic reactions, systemic inflammation, and diabetic retinopathy [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43].

Interestingly, CCL3 treatment lowered serum IgG1 in diabetic mice to levels similar to those of nondiabetic controls (

Figure 3A), suggesting a durable therapeutic effect of topical CCL3 treatment on systemic IgG1-associated inflammation. Of note, IgE and CRP levels in the diabetic groups treated with CCL3 were not significantly different compared to PBS-treated diabetic group (

Table 1). These results indicate that CCL3 therapies do not adversely affect these immune biomarkers. Rather, they potentially have long-term beneficial impact on serum IgG.

3.3. CCL3 Treatment Confers Modest but Significant Hepatoprotective Benefits in Diabetic Mice

Liver enzymes—including alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP)—are frequently elevated in pre-diabetic and diabetic individuals and have been associated with obesity, visceral adiposity, dyslipidemia, increased diabetes risk, and metabolic dysfunction–associated steatosis liver disease (MASLD) [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. In line with these observations, by day 14 post-treatment the PBS-treated diabetic (db/db) control mice exhibited markedly elevated serum ALT (275.65 ± 22.94 U/L), AST (247.58 ± 11.97 U/L), and ALP (217.00 ± 6.32 U/L) levels compared with the nondiabetic control group (ALT: 23.27 ± 1.33 U/L; AST: 83.39 ± 6.18 U/L; ALP: 97.93 ± 16.37 U/L) (

Table 2 and

Figure 4A). Interestingly, topical CCL3 treatment significantly reduced ALT levels in diabetic mice at both 1 µg (210.35 ± 11.43 U/L) and 10 µg (211.18 ± 22.02 U/L) compared with PBS-treated diabetic controls (p < 0.05;

Figure 4A, and

Table 2). While serum AST and ALP levels were significantly elevated in diabetic mice compared to nondiabetic mice, treatment with CCL3 did not alter these levels any further.

To further assess the impact of CCL3 on liver injury, we performed histological analysis of hepatic tissue (Materials & Methods). Compared with nondiabetic mice, diabetic control mice (db/db + PBS) exhibited marked steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning, disruption of normal lobular architecture, and elevated necrosis and inflammation scores (

Figure 4A–D). These histopathological features are consistent with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and liver injury reported in patients with type 2 diabetes [

50,

51,

52]. In contrast, mice treated with CCL3 at either dose showed reduced steatosis, attenuated hepatocyte ballooning, and preservation of hepatic architecture (

Figure 4A–C). Collectively, these findings indicate that CCL3 treatment does not exacerbate liver injury and suggest a potential hepatoprotective effect of CCL3 in diabetic mice.

3.4. CCL3 Does not Cause Organ Toxicity: Histopathological Evidence

Kidney, spleen, pancreas, and heart are among other important organs that are adversely affected by diabetic condition [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58]. We performed histopathological evaluation of these organs to assess potential systemic toxicity following topical CCL3 treatment in diabetic db/db mice. Representative hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections from liver, kidney, spleen, pancreas, and heart are shown, together with semi-quantitative scoring of necrosis and inflammation (Materials & Methods).

Renal histology in db/db + PBS mice revealed characteristic diabetic nephropathy–like changes [

53], including tubular vacuolation and glomerular hypertrophy (

Figure 5A). In contrast, kidneys from CCL3-treated mice displayed comparable histological features without additional structural damage. Quantitative scoring confirmed that necrosis and inflammation levels remained similar across all treatment groups, with no evidence of worsening renal pathology following topical CCL3 application (

Figure 5B-C).

Diabetes causes significant histological changes in the spleen, leading to structural alterations like white pulp atrophy, reduced lymphoid nodules/germinal centers, decreased lymphocyte density, and altered immune cell distribution, often linked to increased oxidative stress and inflammation, resulting in impaired immune function [

54]. The spleen of db/+ control mice showed normal histology, with clearly demarcated white pulp (lymphocyte-rich areas) and red pulp (erythrocyte-rich areas). In contrast, diabetic PBS treated control mice showed disrupted architecture with a lower white pulp percentage compared to non-diabetic control group (53.82 ± 2.94% vs. 69.11 ± 4.13%, p < 0.0001), indicating impaired immune organization (

Figure 5D). CCL3-treated diabetic mice regardless of dose, showed a similar reduction in white pulp (57.33 ± 2.75% and 57.64 ± 4.9% respectively), with no statistical differences from db/db PBS control group, indicating that treatment did not impact splenic changes (

Figure 5D-G).

Diabetic patients display significant histological changes in the pancreas, especially in the islets of Langerhans, including beta-cell loss, insulitis (inflammation in Type 1), and islet amyloidosis (protein deposits in Type 2), alongside potential exocrine tissue damage like fat accumulation and fibrosis, affecting both insulin production and overall pancreatic structure and function [

55,

56]. As expected, nondiabetic db/+ control mice had normal islet and acinar tissue, whereas db/db control mice showed islet distortion and vascular congestion (

Figure 5G). Consistent with these data, diabetic mice showed significantly higher necrosis and inflammation scores than controls (

Figure 5H-I, p < 0.0001). Semi-quantitative scoring showed no evidence of additional CCL3-associated pancreatic toxicity (

Figure 5H-I).

Cardiomyopathy, and cardiovascular problems, including focal myofiber alterations have been reported in diabetic patients [

57,

58]. Consistent with these reports, cardiac sections from db/db + PBS mice exhibited myocardial disruption consistent with diabetic cardiomyopathy, including focal myofiber alterations and increased necrosis scores (

Figure 5J-K). Importantly, topical CCL3 treatment did not increase myocardial rupture, necrosis, or inflammatory changes at the examined doses.

Collectively, histopathological analysis across multiple organs demonstrates that topical CCL3 treatment, even at 10-fold higher dose, does not induce systemic organ toxicity or exacerbate diabetes-associated tissue pathology, supporting its favorable safety profile in this model.

3.5. Assessment of Hematological and Serum Biochemical Parameters

To further evaluate the systemic safety of CCL3 therapy, serum biochemical and hematological parameters were assessed on day 14. As anticipated, glucose levels were significantly higher in db/db mice (402.48 ± 34.02 mg/dL) compared with db/+ controls (231.68 ± 24.41 mg/dL); however, CCL3 treatment did not further affect serum glucose levels (

Table 2). Serum electrolytes (sodium, potassium, chloride, calcium, and phosphorus), as well as total protein and bilirubin concentrations, were similar between PBS- and CCL3-treated diabetic mice, indicating that CCL3 administration did not alter these parameters (

Table 2).

White blood cell (WBC) counts were significantly elevated in db/db mice compared with their db/+ control counterparts (

Table 3), a finding that is consistent with previously reported hematological alterations [

59]. Importantly, administration of CCL3 at either the 1 µg or 10 µg dose did not further alter circulating WBC levels, indicating that CCL3 treatment does not exacerbate diabetes-associated leukocytosis. In addition, no significant differences were detected in hemoglobin concentrations or in the relative proportions of major leukocyte subsets, including neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, and basophils, when comparing diabetic and nondiabetic mice or PBS-treated and CCL3-treated diabetic groups (

Table 3). Consistent with these findings, platelet counts and mean corpuscular volume (MCV) remained comparable across all experimental conditions, and mean platelet volume (MPV) showed no detectable variation among groups (

Table 3). Collectively, these data demonstrate that CCL3 administration at the doses tested does not induce measurable hematological abnormalities, supporting the conclusion that CCL3 therapy is not associated with hematological toxicity under these experimental conditions.

4. Discussion

Previously, we demonstrated that the proinflammatory cytokine CCL3 has therapeutic potential in restoring neutrophil function, improving bacterial clearance, and stimulating healing in diabetic wounds [

4]. However, the lack of a comprehensive safety assessment has limited its translational advancement as an investigative novel biologic for diabetic wound care. The present study is the first to evaluate the acute systemic safety profile of topical CCL3 (MIP-1α) in a diabetic wound model. Our findings show that in db/db mice, single-dose topical administration of CCL3 at the experimentally effective dose and at a 10-fold higher dose was well tolerated, with no evidence of hematological, biochemical, or histopathological toxicity in major organs. Notably, CCL3-treated mice exhibited partial normalization of systemic inflammatory markers and reduced hepatocellular injury, highlighting CCL3’s dual therapeutic potential and safety as a novel biologic for diabetic wound management.

Interestingly, we found that CCL3 treatment reduced serum ALT levels while partially preserving hepatic architecture, indicating hepatoprotective effects. Elevated liver enzymes and fatty liver changes have been well documented in diabetic mice and type 2 diabetes patients [

60,

61]. In our study, CCL3-treated mice showed less ballooning and necrosis, supporting the idea that CCL3-induced neutrophil recruitment may aid in the clearance of necrotic cells and the restoration of tissue homeostasis. Similar findings have been reported for CXCL1 and other neutrophil chemokines, where increasing early neutrophil infiltration accelerated bacterial clearance while reducing secondary tissue damage [

62,

63].

A major concern with any cytokine or chemokine-based therapy is the risk of systemic immune dysregulation or hypersensitivity. The elevated IgE, IgG1, and CRP levels in diabetic PBS mice were consistent with low-grade systemic inflammation in diabetes [

42,

64]. Our immunological analysis revealed that CCL3 did not increase IgE, IgG1, or CRP levels, indicating that treatment did not cause systemic hypersensitivity or exaggerated inflammatory responses. Indeed, CCL3 treatment groups had lower IgG1 levels comparable to the nondiabetic control group, suggesting that CCL3 might be beneficial in reducing systemic inflammation in diabetic hosts, at least in regard to IgG1 levels.

Hematological and biochemical analyses have been accepted as gold-standard parameters in preclinical toxicity testing (OECD Test Guidelines; FDA Preclinical Research guidelines). In our investigation, total blood parameters and biochemistry markers remained within physiological ranges in all groups, indicating that systemic homeostasis was maintained. Notably, diabetic PBS mice demonstrated higher liver marker (ALT, AST, ALP) levels, consistent with previous results of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in db/db mice [

65]. Surprisingly, CCL3 therapy improved hepatocyte steatosis and ballooning while lowering ALT levels. This shows that CCL3 may have hepatoprotective properties in addition to being non-toxic. These findings are consistent with reports that restoring prompt neutrophil responses can avoid further tissue harm by encouraging early clearance of necrotic material and minimizing persistent inflammation [

66,

67].

Histological evaluation is an essential element of toxicity testing because it provides a direct, observable, and detailed view of a substance’s effect on tissues and cells. Histopathological examination revealed that db/db mice had characteristic diabetes-associated lesions in multiple organs, including hepatic steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning, tubular necrosis in the kidneys, white pulp disruption in the spleen, pancreatic islet degeneration, and focal myofibrillar injury in cardiac tissue. These findings are consistent with previous reports describing multisystem injury in leptin receptor-deficient diabetic mice. Chronic hyperglycemia drives oxidative stress, inflammation, and structural organ damage [

68,

69]. Importantly, topical CCL3 did not exacerbate these pathological features; instead, organ scores in CCL3-treated groups were comparable to those in PBS-treated diabetic mice, confirming the absence of systemic organ toxicity. This distinguishes CCL3 from several proinflammatory chemokines, which, if dysregulated, can cause tissue injury [

70].

CCL3 has also been shown to reduce infection and promote wound healing in nondiabetic mice [

33], underscoring its potential as a novel therapeutic approach in wound care. Given the critical role of neutrophils in host defense, immunomodulatory strategies that enhance neutrophil mobilization and activation at sites of infection can be highly effective in controlling infection while simultaneously promoting tissue repair and healing [

33,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76].

Collectively, these findings position CCL3 as a promising candidate biologic that addresses two critical aspects of diabetic wound care: compromised immune defense and safety. Unlike growth factors like recombinant PDGF-BB (Becaplermin), which showed limited efficacy and raised safety concerns, CCL3 appears to combine efficacy in infection control and wound repair with a good systemic tolerability profile. These findings meet a critical translational benchmark, as regulatory guidelines (FDA, ICH M3[R2], ICH S6[R1]) emphasize the importance of conducting preclinical safety studies in relevant disease models before moving biologics into clinical trials. Future research should build on these findings by examining chronic dosing regimens, assessing long-term immunogenicity, and testing in secondary infection models that mimic clinical wound contamination. Nonetheless, the current study provides a solid preclinical foundation, demonstrating efficacy and safety in the diabetic population.

5. Conclusions

This study shows that topical administration of CCL3 in diabetic mice is safe and well-tolerated, with no evidence of systemic organ toxicity. CCL3 reduced hepatocellular injury markers, preserved hematological and biochemical homeostasis, and did not cause abnormal immune responses. CCL3 accelerates wound closure in db/db mice, demonstrating a dual role in restoring impaired immune function and promoting tissue repair. These new safety studies highlight CCL3 as a promising biologic for diabetic wound therapy, combining immunomodulatory efficacy with a favorable systemic safety profile, and represent an important step toward clinical translation.

Authors Contribution

Conceptualization: SHS; Formal Analysis: DD, RP, GT; Funding Acquisition: SHS, GAA; Investigation: SHS, DD, RP, GT; Methodology: SHS, DH; Resources: SHS; Supervision: SHS; Validation: DD, RP, GT; Writing—Original Draft Preparation: DD, RP,SHS; Writing—Review and Editing: DD, RP, GT, FAF, GAA,SHS.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01DK135557 (to SHS & GAA) and R01DK107713 (to SHS).

Conflicts of Interest

A patent (International Application Number: PCT/US19/41112) has been filed. Dr. Sasha Shafikhani is the listed inventor on this application.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Isseroff Laboratory for providing instrumental support with tissue processing, sectioning, and microscopy. We also thank the Comparative Pathology Laboratory, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, for performing plasma and serum hematology and biochemical studies.

References

- Roy, R., R. Singh, and S.H. Shafikhani, Infection in Diabetes: Epidemiology, Immune Dysfunctions, and Therapeutics, in The Diabetic Foot: Medical and Surgical Management. 2024, Springer. p. 299-326.

- Menke, N.B., et al., Impaired wound healing. Clin Dermatol, 2007. 25(1): p. 19-25.

- Bjarnsholt, T., et al., Why chronic wounds will not heal: a novel hypothesis. Wound Repair Regen, 2008. 16(1): p. 2-10. [CrossRef]

- Roy, R., et al., Overriding impaired FPR chemotaxis signaling in diabetic neutrophil stimulates infection control in murine diabetic wound. Elife, 2022. 11: p. 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Wood, S., et al., Pro-inflammatory chemokine CCL2 (MCP-1) promotes healing in diabetic wounds by restoring the macrophage response. PLoS One, 2014. 9(3): p. 1-8,e91574. [CrossRef]

- Roy, R., et al., IL-10 Dysregulation Underlies Chemokine Insufficiency, Delayed Macrophage Response, and Impaired Healing in Diabetic Wounds. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 2022. 142(3): p. 692-704. e14. [CrossRef]

- Goldufsky, J., et al., Pseudomonas aeruginosa uses T3SS to inhibit diabetic wound healing. Wound Repair Regen, 2015. 23(4): p. 557-64. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.F., et al., CrkII/Abl phosphorylation cascade is critical for NLRC4 inflammasome activity and is blocked by Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoT. Nature communications, 2022. 13(1): p. 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.F., et al., Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoT induces G1 cell cycle arrest in melanoma cells. Cell Microbiol, 2021. 23(8): p. e13339,1-11. [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.J., et al., Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoT induces mitochondrial apoptosis in target host cells in a manner that depends on its GTPase-activating protein (GAP) domain activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2015. 290(48): p. 29063-29073. [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.J., J. Goldufsky, and S.H. Shafikhani, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoT Induces Atypical Anoikis Apoptosis in Target Host Cells by Transforming Crk Adaptor Protein into a Cytotoxin. PLoS Pathog, 2015. 11(5): p. e1004934,1-22. [CrossRef]

- Dovi, J.V., A.M. Szpaderska, and L.A. DiPietro, Neutrophil function in the healing wound: adding insult to injury? Thromb Haemost, 2004. 92(2): p. 275-80.

- Brinkmann, V., et al., Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science, 2004. 303(5663): p. 1532-5. [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.M., S.H. Shafikhani, and A.M. Soulika, Macrophage and Neutrophil Dysregulation in Diabetic Wounds. Adv Wound Care 2024. [CrossRef]

- Delamaire, M., et al., Impaired leucocyte functions in diabetic patients. Diabetic Medicine, 1997. 14(1): p. 29-34. [CrossRef]

- Ziyadeh, N., et al., A matched cohort study of the risk of cancer in users of becaplermin. Advances in skin & wound care, 2011. 24(1): p. 31-39. [CrossRef]

- Blume, P., et al., Safety and efficacy of Becaplermin gel in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Chronic Wound Care Management and Research, 2014. 1: p. 11-14. [CrossRef]

- Howell-Jones, R.S., et al., A review of the microbiology, antibiotic usage and resistance in chronic skin wounds. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2005. 55(2): p. 143-9. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M., I. Uckay, and B.A. Lipsky, In diabetic foot infections antibiotics are to treat infection, not to heal wounds. Expert Opin Pharmacother, 2015. 16(6): p. 821-32. [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.S., et al., Antimicrobial resistance: a concise update. The Lancet Microbe, 2025. 6(1). [CrossRef]

- Gu, S., et al., Drug-induced liver injury with commonly used antibiotics in the all of us research program. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 2023. 114(2): p. 404-412. [CrossRef]

- Rivetti, S., et al., Aminoglycosides-related ototoxicity: mechanisms, risk factors, and prevention in pediatric patients. Pharmaceuticals, 2023. 16(10): p. 1353. [CrossRef]

- Moran, L.C., Science, Medicine, and Animals: Teacher’s Guide. 2005: ERIC.

- Prasad, C.B., A review on drug testing in animals. Transl. Biomed, 2016. 7: p. 1-4.

- Singh, R., M. Gholipourmalekabadi, and S.H. Shafikhani, Animal models for type 1 and type 2 diabetes: advantages and limitations. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 2024. 15: p. 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Goldufsky, J., et al., Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin T induces potent cytotoxicity against a variety of murine and human cancer cell lines. J Med Microbiol, 2015. 64(Pt 2): p. 164-73.

- Kohlhapp, F.J., et al., Non-oncogenic Acute Viral Infections Disrupt Anti-cancer Responses and Lead to Accelerated Cancer-Specific Host Death. Cell Rep, 2016. 17(4): p. 957-965. [CrossRef]

- Gil, C.R.E., et al., Food insecurity promotes adiposity in mice. Obesity (Silver Spring), 2025. 33(6): p. 1087-1100. [CrossRef]

- Rathkolb, B., et al., Clinical Chemistry and Other Laboratory Tests on Mouse Plasma or Serum. Curr Protoc Mouse Biol, 2013. 3(2): p. 69-100. [CrossRef]

- McClure, D.E., Clinical pathology and sample collection in the laboratory rodent. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract, 1999. 2(3): p. 565-90, vi. [CrossRef]

- Shrimali, R.K., et al., Selenoprotein expression is essential in endothelial cell development and cardiac muscle function. Neuromuscul Disord, 2007. 17(2): p. 135-42. [CrossRef]

- Rutgers, M., et al., Evaluation of histological scoring systems for tissue-engineered, repaired and osteoarthritic cartilage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 2010. 18(1): p. 12-23. [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, F., et al., Therapeutic evaluation of immunomodulators in reducing surgical wound infection. Faseb j, 2022. 36(1): p. e22090. [CrossRef]

- Ulker, E., et al., Comparison of Pain-Like behaviors in two surgical incision animal models in C57BL/6J mice. Neurobiology of Pain, 2022. 12: p. 100103. [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi Nejat, M., et al., Continuous locomotor activity monitoring to assess animal welfare following intracranial surgery in mice. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 2024. 18: p. 1457894. [CrossRef]

- Santhekadur, P.K., D.P. Kumar, and A.J. Sanyal, Preclinical models of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of hepatology, 2018. 68(2): p. 230-237. [CrossRef]

- Ardawi, M., H. Nasrat, and A. Bahnassy, Serum immunoglobulin concentrations in diabetic patients. Diabetic medicine, 1994. 11(4): p. 384-387. [CrossRef]

- Tang, X., et al., IgG subclass deposition in diabetic nephropathy. European Journal of Medical Research, 2022. 27(1): p. 147. [CrossRef]

- Abdellah, M.H., et al., Serum immunoglobulin G as a predictive marker of early renal affection in type-2 diabetic patients: a single-center study. Journal of The Egyptian Society of Nephrology and Transplantation, 2023. 23(1): p. 17-25.

- Klamt, S., et al., Association between IgE-mediated allergies and diabetes mellitus type 1 in children and adolescents. Pediatric diabetes, 2015. 16(7): p. 493-503. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K., et al., House dust mite and Cockroach specific Immunoglobulin E sensitization is associated with diabetes mellitus in the adult Korean population. Scientific Reports, 2018. 8(1): p. 2614. [CrossRef]

- Stanimirovic, J., et al., Role of C-Reactive Protein in Diabetic Inflammation. Mediators Inflamm, 2022. 2022: p. 3706508. [CrossRef]

- Song, J., et al., Relationship between C-reactive protein level and diabetic retinopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos one, 2015. 10(12): p. e0144406. [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y., et al., The association of alanine aminotransferase and diabetic microvascular complications: A Mendelian randomization study. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 2023. 14: p. 1104963. [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, P., et al., Serum Alanine TransaminaseLevel in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and It’s Relationship with Glycemic Status. Eastern Medical College Journal, 2024. 9(2): p. 68-72. [CrossRef]

- Shibabaw, T., et al., Assessment of liver marker enzymes and its association with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Northwest Ethiopia. BMC research notes, 2019. 12(1): p. 707. [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A., et al., Elevated liver enzymes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Cureus, 2018. 10(11). [CrossRef]

- Cusi, K., et al., Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) in People With Diabetes: The Need for Screening and Early Intervention. A Consensus Report of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care, 2025. 48(7): p. 1057-1082. [CrossRef]

- Makaju, M., et al., Pattern of Serum Liver Enzymes in the Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Journal of Research in Applied and Basic Medical Sciences, 2023. 9(4): p. 272-279. [CrossRef]

- Prashanth, M., et al., Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Assoc Physicians India, 2009. 57(3): p. 205-210.

- Dai, W., et al., Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Medicine, 2017. 96(39): p. e8179. [CrossRef]

- Leite, N.C., et al., Histopathological stages of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in type 2 diabetes: prevalences and correlated factors. Liver International, 2011. 31(5): p. 700-706. [CrossRef]

- Habib, S.L., Kidney atrophy vs. hypertrophy in diabetes: which cells are involved? Cell Cycle, 2018. 17(14): p. 1683-1687. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., et al., Fibroblast growth factor 1 ameliorates diabetes-induced splenomegaly via suppressing inflammation and oxidative stress. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2020. 528(2): p. 249-255. [CrossRef]

- Dyson, N.J., et al., Quantitative analysis of human adult pancreatic histology reveals separate fatty and fibrotic phenotypes in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia, 2025: p. 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Granlund, L., et al., Histological and transcriptional characterization of the pancreatic acinar tissue in type 1 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care, 2021. 9(1). [CrossRef]

- Voulgari, C., D. Papadogiannis, and N. Tentolouris, Diabetic cardiomyopathy: from the pathophysiology of the cardiac myocytes to current diagnosis and management strategies. Vascular health and risk management, 2010: p. 883-903. [CrossRef]

- Marzona, I., et al., Are all people with diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors or microvascular complications at very high risk? Findings from the Risk and Prevention Study. Acta diabetologica, 2017. 54(2): p. 123-131. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., et al., White blood cell subtypes and risk of type 2 diabetes. Journal of Diabetes and its Complications, 2017. 31(1): p. 31-37. [CrossRef]

- Yki-Järvinen, H., Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease as a cause and a consequence of metabolic syndrome. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2014. 2(11): p. 901-10. [CrossRef]

- Yki-Järvinen, H., et al., New insulin glargine 300 units/mL versus glargine 100 units/mL in people with type 2 diabetes using oral agents and basal insulin: glucose control and hypoglycemia in a 6-month randomized controlled trial (EDITION 2). Diabetes Care, 2014. 37(12): p. 3235-43. [CrossRef]

- De Filippo, C., et al., Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2010. 107(33): p. 14691-6.

- Charmoy, M., et al., Neutrophil-derived CCL3 is essential for the rapid recruitment of dendritic cells to the site of Leishmania major inoculation in resistant mice. PLoS pathogens, 2010. 6(2): p. e1000755. [CrossRef]

- Pickup, J.C., Inflammation and activated innate immunity in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 2004. 27(3): p. 813-23. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T., et al., Metformin improves nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in db/db mice by inhibiting ferroptosis. Eur J Pharmacol, 2024. 966: p. 176341. [CrossRef]

- Peiseler, M. and P. Kubes, More friend than foe: the emerging role of neutrophils in tissue repair. J Clin Invest, 2019. 129(7): p. 2629-2639. [CrossRef]

- Filep, J.G., Targeting Neutrophils for Promoting the Resolution of Inflammation. Front Immunol, 2022. 13: p. 866747. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, T.B., et al., Mice with Type 2 Diabetes Present Significant Alterations in Their Tissue Biomechanical Properties and Histological Features. Biomedicines, 2021. 10(1). [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z., et al., Multi-omics analysis reveals the pathogenesis of db/db mice diabetic kidney disease and the treatment mechanisms of multi-bioactive compounds combination from Salvia miltiorrhiza. Front Pharmacol, 2022. 13: p. 987668. [CrossRef]

- Zlotnik, A. and O. Yoshie, The chemokine superfamily revisited. Immunity, 2012. 36(5): p. 705-16. [CrossRef]

- Roy, R., et al., Reduced Bioactive Microbial Products (Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns) Contribute to Dysregulated Immune Responses and Impaired Healing in Infected Wounds in Mice with Diabetes. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 2024. 144(2): p. 387-397. e11. [CrossRef]

- Shafikhani, S., Closing Editorial: Immunopathogenesis of Bacterial Infection. 2025, MDPI. p. 1894. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.L., et al., Therapeutic assessment of N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP) in reducing periprosthetic joint infection. Eur Cell Mater, 2021. 41: p. 122-138. [CrossRef]

- Kroin, J.S., et al., Local vancomycin effectively reduces surgical site infection at implant site in rodents. Regional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine, 2018. 43(7): p. 795-804. [CrossRef]

- Kroin, J.S., et al., Perioperative high inspired oxygen fraction therapy reduces surgical site infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa in rats. Journal of medical microbiology, 2016. 65(8): p. 738–744. [CrossRef]

- Kroin, J.S., et al., Short-term glycemic control is effective in reducing surgical site infection in diabetic rats. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 2015. 120(6): p. 1289-1296. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Experimental design of the toxicity study. Animals were assigned to control and db/db groups receiving PBS or topical CCL3 at low (1 µg) or high (10 µg) doses. On day 0, full-thickness wounds were created and CCL3 or PBS was applied topically. Animals were monitored daily for food intake, body weight, and behavioral changes for 14 days. At the end of the study period, blood and major organs were collected for hematological, biochemical, and histopathological analyses.

Figure 1.

Experimental design of the toxicity study. Animals were assigned to control and db/db groups receiving PBS or topical CCL3 at low (1 µg) or high (10 µg) doses. On day 0, full-thickness wounds were created and CCL3 or PBS was applied topically. Animals were monitored daily for food intake, body weight, and behavioral changes for 14 days. At the end of the study period, blood and major organs were collected for hematological, biochemical, and histopathological analyses.

Figure 2.

Effects of CCL3 treatment on food intake and body weight in diabetic mice. (A) Food intake was measured on Days 0, 1, 7, and 14 in nondiabetic (db/+) mice treated with PBS and diabetic (db/db) mice treated with PBS, CCL3 (1 µg), or CCL3 (10 µg). db/db mice exhibited significantly increased food intake at Days 7 and 14 compared with db/+ controls, with no significant differences observed among db/db treatment groups. (B) Body weight was monitored following wound surgery and treatment at the indicated time points. db/db mice remained significantly heavier than db/+ controls throughout the study, and CCL3 treatment had no effect on body weight. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with multiple-comparison post hoc testing (n = 6 mice per group; ns, not significant; ****p < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

Effects of CCL3 treatment on food intake and body weight in diabetic mice. (A) Food intake was measured on Days 0, 1, 7, and 14 in nondiabetic (db/+) mice treated with PBS and diabetic (db/db) mice treated with PBS, CCL3 (1 µg), or CCL3 (10 µg). db/db mice exhibited significantly increased food intake at Days 7 and 14 compared with db/+ controls, with no significant differences observed among db/db treatment groups. (B) Body weight was monitored following wound surgery and treatment at the indicated time points. db/db mice remained significantly heavier than db/+ controls throughout the study, and CCL3 treatment had no effect on body weight. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with multiple-comparison post hoc testing (n = 6 mice per group; ns, not significant; ****p < 0.0001).

Figure 3.

Evaluation of serum IgG1 levels as an immunological safety marker following CCL3 treatment. Serum IgG1 levels were quantified on day 14 in nondiabetic (db/+) mice treated with PBS and diabetic (db/db) mice treated with PBS, CCL3 (1 µg), or CCL3 (10 µg). Diabetic PBS-treated mice exhibited elevated IgG1 levels, indicative of systemic inflammation, whereas CCL3-treated groups showed a marked reduction, demonstrating that topical CCL3 does not elicit immunotoxic responses. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6 mice per group). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.0001.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of serum IgG1 levels as an immunological safety marker following CCL3 treatment. Serum IgG1 levels were quantified on day 14 in nondiabetic (db/+) mice treated with PBS and diabetic (db/db) mice treated with PBS, CCL3 (1 µg), or CCL3 (10 µg). Diabetic PBS-treated mice exhibited elevated IgG1 levels, indicative of systemic inflammation, whereas CCL3-treated groups showed a marked reduction, demonstrating that topical CCL3 does not elicit immunotoxic responses. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6 mice per group). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.0001.

Figure 4.

CCL3 treatment confers modest but significant hepatoprotective benefits in diabetic mice. A) Serum alanine transaminase (ALT) levels, (B) hepatocyte size, (C-D) necrosis and inflammation scores were assessed on day 14 in control (db/+) mice treated with PBS and diabetic (db/db) mice treated with PBS, CCL3 (1 µg), or CCL3 (10 µg). (E) Representative H&E-stained liver sections showing normal hepatic architecture in control mice and pronounced steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning in PBS- and CCL3-treated diabetic mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 6 per group). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by multiple comparisons; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001. Scale bars = 50 µm.

Figure 4.

CCL3 treatment confers modest but significant hepatoprotective benefits in diabetic mice. A) Serum alanine transaminase (ALT) levels, (B) hepatocyte size, (C-D) necrosis and inflammation scores were assessed on day 14 in control (db/+) mice treated with PBS and diabetic (db/db) mice treated with PBS, CCL3 (1 µg), or CCL3 (10 µg). (E) Representative H&E-stained liver sections showing normal hepatic architecture in control mice and pronounced steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning in PBS- and CCL3-treated diabetic mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 6 per group). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by multiple comparisons; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001. Scale bars = 50 µm.

Figure 5.

Histopathological assessment of major organs following topical CCL3 treatment. Representative H&E images of kidney (A-C), spleen (D-F), pancreas (G-I), and heart J-K) collected on day 14 from control (db/+) mice, diabetic (db/db) mice treated with PBS, and diabetic mice treated with CCL3 (1 µg or 10 µg). Diabetic PBS mice displayed typical diabetic alterations, while CCL3-treated groups showed no additional pathology. Semiquantitative necrosis and inflammation scores (right panels) revealed no significant differences between CCL3-treated and diabetic PBS groups. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 6). One-way ANOVA; *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001. Scale bars = 50 µm.

Figure 5.

Histopathological assessment of major organs following topical CCL3 treatment. Representative H&E images of kidney (A-C), spleen (D-F), pancreas (G-I), and heart J-K) collected on day 14 from control (db/+) mice, diabetic (db/db) mice treated with PBS, and diabetic mice treated with CCL3 (1 µg or 10 µg). Diabetic PBS mice displayed typical diabetic alterations, while CCL3-treated groups showed no additional pathology. Semiquantitative necrosis and inflammation scores (right panels) revealed no significant differences between CCL3-treated and diabetic PBS groups. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 6). One-way ANOVA; *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001. Scale bars = 50 µm.

Table 1.

Serum immunological parameters following 14-day topical CCL3 treatment in diabetic mice. Serum levels of IgG1, IgE, and C-reactive protein (CRP) were measured in nondiabetic control (db/+) mice treated with PBS and diabetic (db/db) mice treated with PBS, CCL3 (1 µg), or CCL3 (10 µg) on day 14. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6 per group).

Table 1.

Serum immunological parameters following 14-day topical CCL3 treatment in diabetic mice. Serum levels of IgG1, IgE, and C-reactive protein (CRP) were measured in nondiabetic control (db/+) mice treated with PBS and diabetic (db/db) mice treated with PBS, CCL3 (1 µg), or CCL3 (10 µg) on day 14. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6 per group).

| Parameters |

Ctrl + PBS |

db/db + PBS |

db/db + CCL3 (1 µg) |

db/db + CCL3 (10 µg) |

| IgG1 (µg/mL) |

192.45 ± 13.51 |

285.75±86.27 |

137.97 ± 21.18 |

198.86 ± 7.50 |

| IgE (µg/mL) |

94.29 ± 22.03 |

207.35 ± 57.64 |

150.41±17.4 |

266.25 ± 51.61 |

| CRP (ng/mL) |

1.83 ± 0.33 |

8.14 ± 1.86 |

6.97 ± 1.66 |

8.29 ± 0.88 |

Table 2.

Serum biochemical parameters following 14-day topical CCL3 treatment in diabetic mice. Serum biochemical indices were evaluated on day 14 in control (db/+) mice treated with PBS and diabetic (db/db) mice treated with PBS, CCL3 (1 µg), or CCL3 (10 µg). Parameters included liver function markers (ALT, AST, ALP), renal function markers (BUN, creatinine), electrolytes, glucose, and total protein. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6 per group). Standard physiological ranges are shown for reference.

Table 2.

Serum biochemical parameters following 14-day topical CCL3 treatment in diabetic mice. Serum biochemical indices were evaluated on day 14 in control (db/+) mice treated with PBS and diabetic (db/db) mice treated with PBS, CCL3 (1 µg), or CCL3 (10 µg). Parameters included liver function markers (ALT, AST, ALP), renal function markers (BUN, creatinine), electrolytes, glucose, and total protein. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6 per group). Standard physiological ranges are shown for reference.

| Parameters |

Ctrl + PBS |

db/db + PBS |

db/db + CCL3 (1 µg) |

db/db + CCL3 (10 µg) |

Standard Range |

| Alanine Transaminase U/L |

23.27 ± 1.33 |

275.65 ± 22.94 |

210.35 ± 11.43 |

211.18 ± 22.02 |

0-403 |

| Aspartate Transaminase U/L |

83.39 ± 6.18 |

247.58 ± 11.97 |

264.39 ± 14.76 |

209.20 ± 14.21 |

0-552 |

| Alkaline Phosphatase U/L |

97.93 ± 16.37 |

217.00 ± 6.32 |

191.98 ± 21.03 |

212.70 ± 27.02 |

49-172 |

| Blood Urea Nitrogen mg/dL |

26.97 ± 0.83 |

30.40 ± 1.10 |

31.05 ± 0.99 |

29.60 ± 1.39 |

15.2-34.7 |

| Calcium mg/dL |

10.17 ± 0.07 |

10.89 ± 0.18 |

10.52 ± 0.38 |

10.05 ± 0.40 |

9.6-11-5 |

| Chloride mmol/L |

114.92 ± 0.76 |

109.42 ± 0.61 |

109.13 ± 1.53 |

110.28 ± 2.03 |

105-118 |

| Creatinine mg/dL |

0.03 ± 0.00 |

0.06 ± 0.00 |

0.05 ± 0.01 |

0.05 ± 0.00 |

0.0-0.3 |

| Glucose mg/dL |

231.68 ± 24.41 |

402.48 ± 34.02 |

464.52 ± 27.46 |

477.40 ± 87.53 |

130-254 |

| Potassium mmol/L |

4.36 ± 0.10 |

5.06 ± 0.23 |

6.84 ± 1.05 |

6.11 ± 1.04 |

6.9-10.0 |

| Sodium mol/L |

155.33 ± 1.02 |

154.33 ± 0.92 |

155.50 ± 1.28 |

156.80 ± 3.32 |

150-160 |

| Phosphorus mg/dL |

9.98 ± 0.82 |

11.10 ± 0.62 |

14.03 ± 0.85 |

14.39 ± 1.35 |

7.5-10.7 |

| Total Bilirubin mg/dL |

0.05 ± 0.01 |

0.06 ± 0.01 |

0.06 ± 0.02 |

0.06 ± 0.01 |

0.0-0.2 |

| Total Protein g/dL |

4.71 ± 0.18 |

5.80 ± 0.11 |

5.01 ± 0.87 |

5.88 ± 0.31 |

4.7-6.1 |

Table 3.

Hematological parameters following 14-day topical CCL3 treatment in diabetic mice. Hematological profiles, including white blood cell (WBC) count, red blood cell (RBC) indices, platelet count, and leukocyte differentials, were analyzed on day 14 in control (db/+) mice treated with PBS and diabetic (db/db) mice treated with PBS, CCL3 (1 µg), or CCL3 (10 µg). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6 per group).

Table 3.

Hematological parameters following 14-day topical CCL3 treatment in diabetic mice. Hematological profiles, including white blood cell (WBC) count, red blood cell (RBC) indices, platelet count, and leukocyte differentials, were analyzed on day 14 in control (db/+) mice treated with PBS and diabetic (db/db) mice treated with PBS, CCL3 (1 µg), or CCL3 (10 µg). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6 per group).

| Parameters |

Ctrl + PBS |

db/db + PBS |

db/db + CCL3 (1 µg) |

db/db + CCL3 (10 µg) |

Standard Range |

| WBC (K/ul) |

9.89 ± 1.55 |

15.10 ± 0.79 |

9.46 ± 1.60 |

9.08 ± 1.28 |

5.1-14.7 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) |

10.77 ± 0.29 |

12.03 ± 0.54 |

12.33 ± 0.62 |

11.78 ± 0.37 |

11.7-16.2 |

| Neutrophil % |

17.48 ± 2.60 |

20.75 ± 1.34 |

16.79 ± 2.02 |

17.44 ± 0.91 |

12.5-31.2 |

| Lymphocyte % |

72.07 ± 3.84 |

68.00 ± 1.95 |

72.94 ± 2.81 |

73.16 ± 1.23 |

62.9-82.7 |

| Monocyte % |

6.32 ± 0.47 |

6.66 ± 0.27 |

5.55 ± 0.36 |

5.69 ± 0.37 |

2.5-7.5 |

| Eosinophil % |

3.33 ± 0.68 |

3.77 ± 0.46 |

3.56 ± 0.67 |

3.11 ± 0.13 |

1-3% |

| Basophil % |

0.89 ± 0.16 |

0.89 ± 0.10 |

0.92 ± 0.11 |

0.58 ± 0.10 |

<1% |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) |

10.77 ± 0.29 |

12.03 ± 0.54 |

12.33 ± 0.62 |

11.78 ± 0.37 |

11.0-16.2 |

| MCV (fL) |

55.67 ± 2.90 |

58.33 ± 0.41 |

58.65 ± 1.06 |

58.78 ± 0.96 |

45.0-55.0 |

| Platelets (K/uL) |

757.67 ± 139.47 |

746.33 ± 67.57 |

813.67 ± 108.18 |

925.20 ± 95.57 |

574-1079 |

| MPV (fL) |

6.00 ± 0.15 |

6.10 ± 0.08 |

6.17 ± 0.12 |

6.00 ± 0.10 |

5.0-20.0 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).