Submitted:

24 December 2025

Posted:

25 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The increasing population of mesopredators in Central Europe necessitates precise monitoring for effective game management. This study aimed to estimate the minimum population and reproduction of the European badger (Meles meles), red fox (Vulpes vulpes), and golden jackal (Canis aureus) in two hunting grounds in southwestern Hungary (Drávaszentes and Darány). Methods included a total burrow count conducted in early 2025, followed by the deployment of wildlife cameras at inhabited setts to record adults and cubs. Results indicated an inhabited burrow density of 1.05/100 ha for badgers and 0.38/100 ha for foxes in Drávaszentes, with average litter sizes of 1.13 and 2.33 cubs, respectively. In Darány, badger density was 1.43/100 ha, while jackals were present at 0.2/100 ha. Additionally, habitat composition preference was analyzed using QGIS by comparing Corine Land Cover categories within 400 m buffers around burrows against random points. Habitat analysis suggested local preferences for non-irrigated arable land and mixed forests. These findings provide essential baseline data on predator population dynamics to support conscious management decisions.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

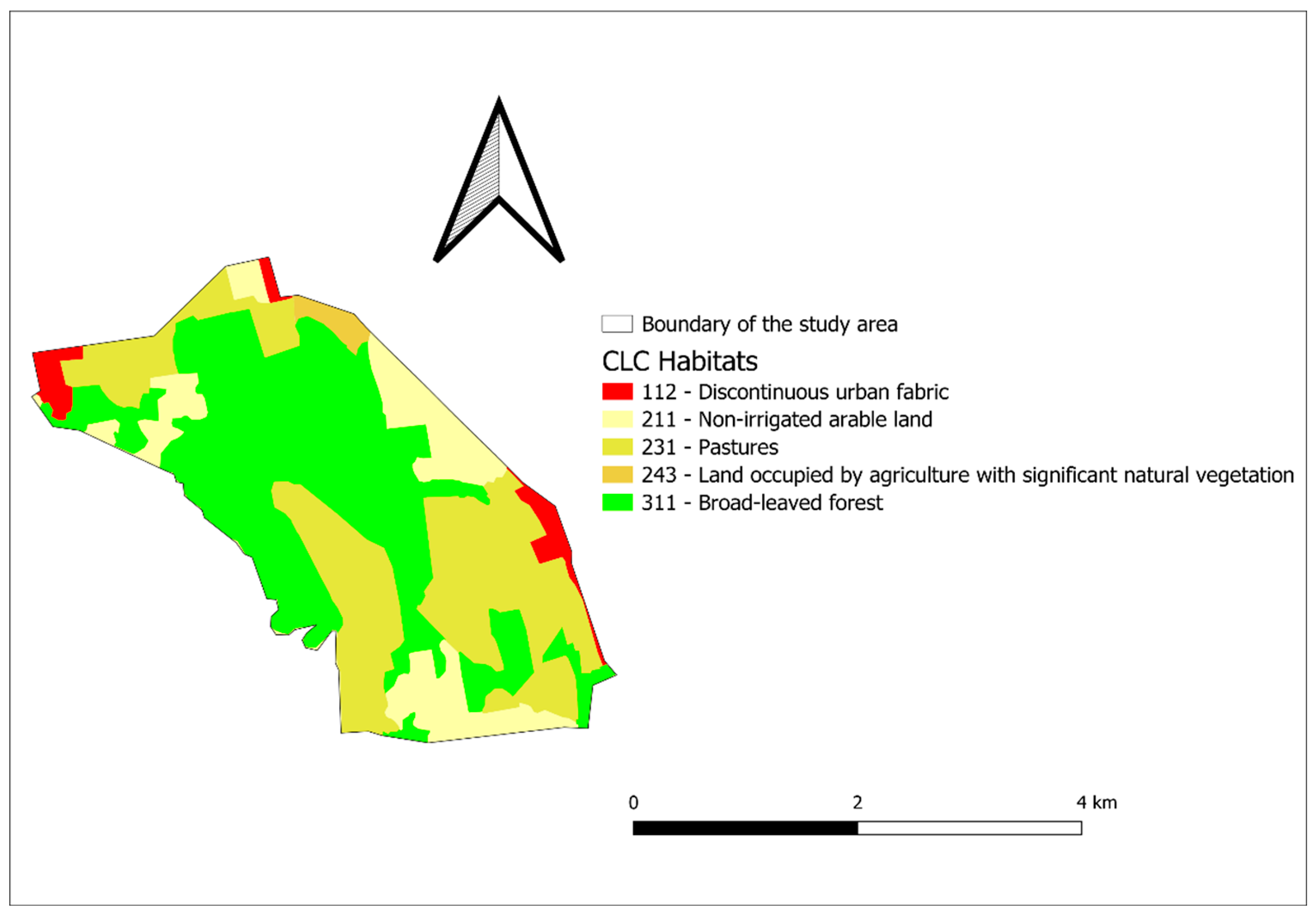

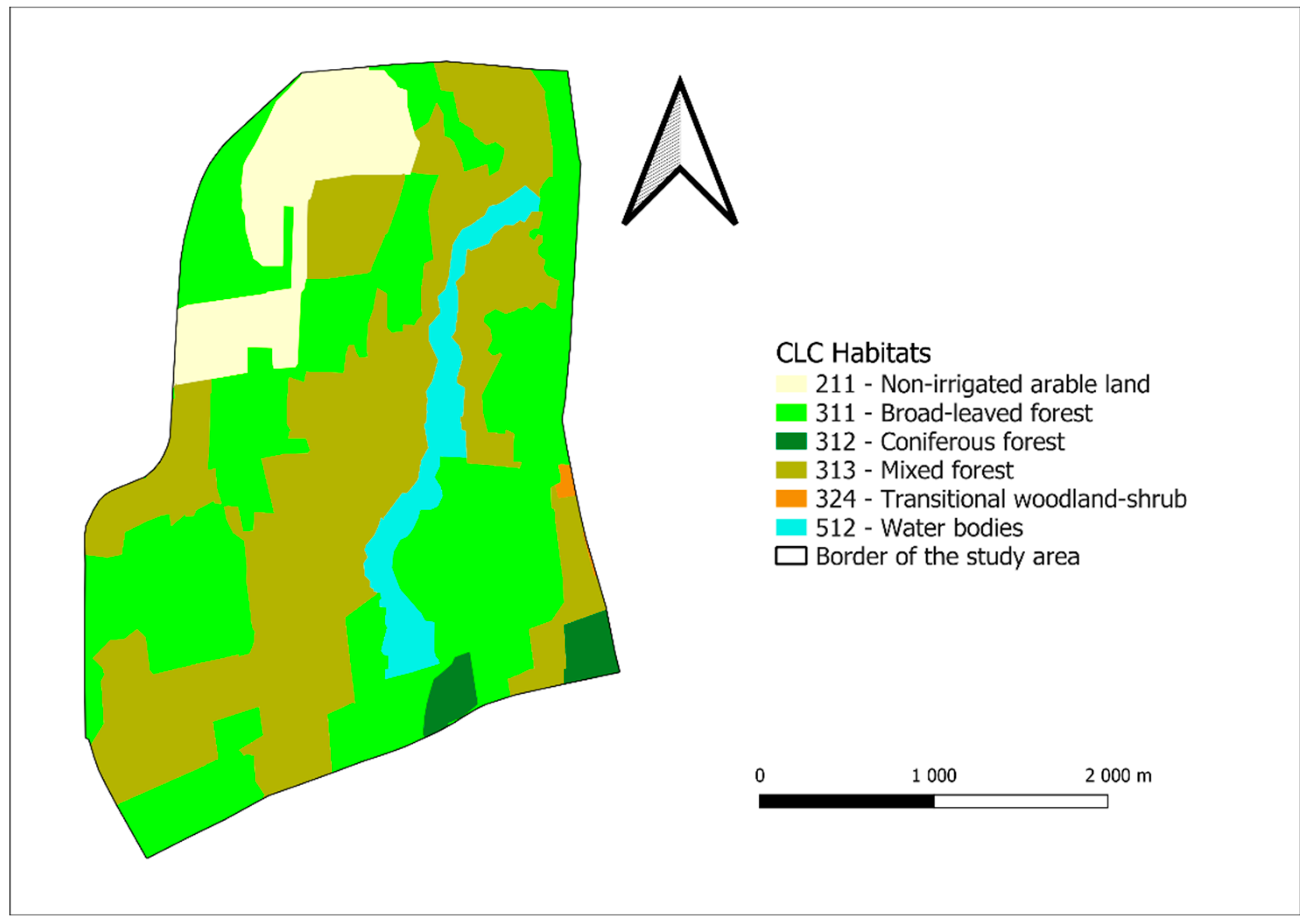

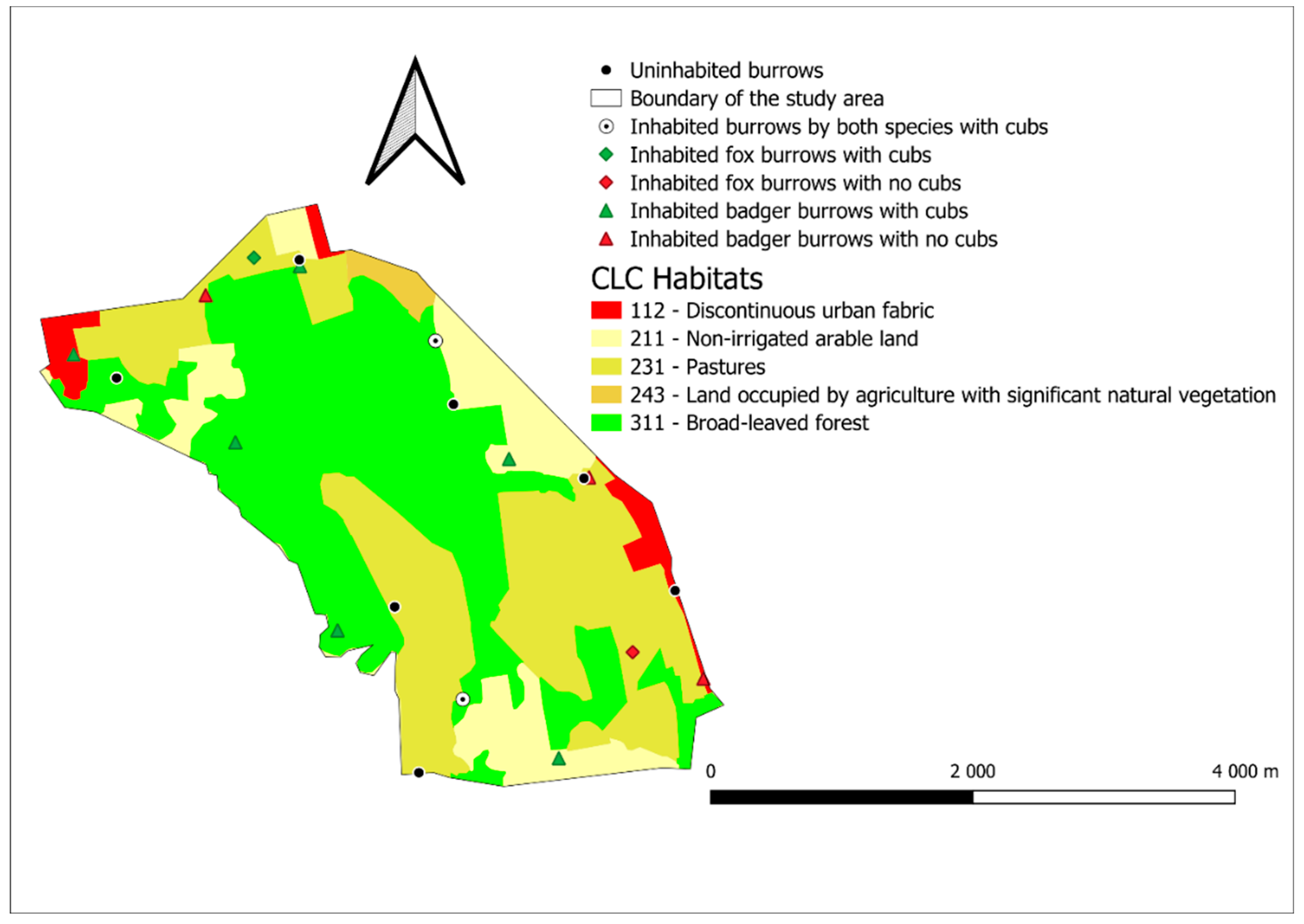

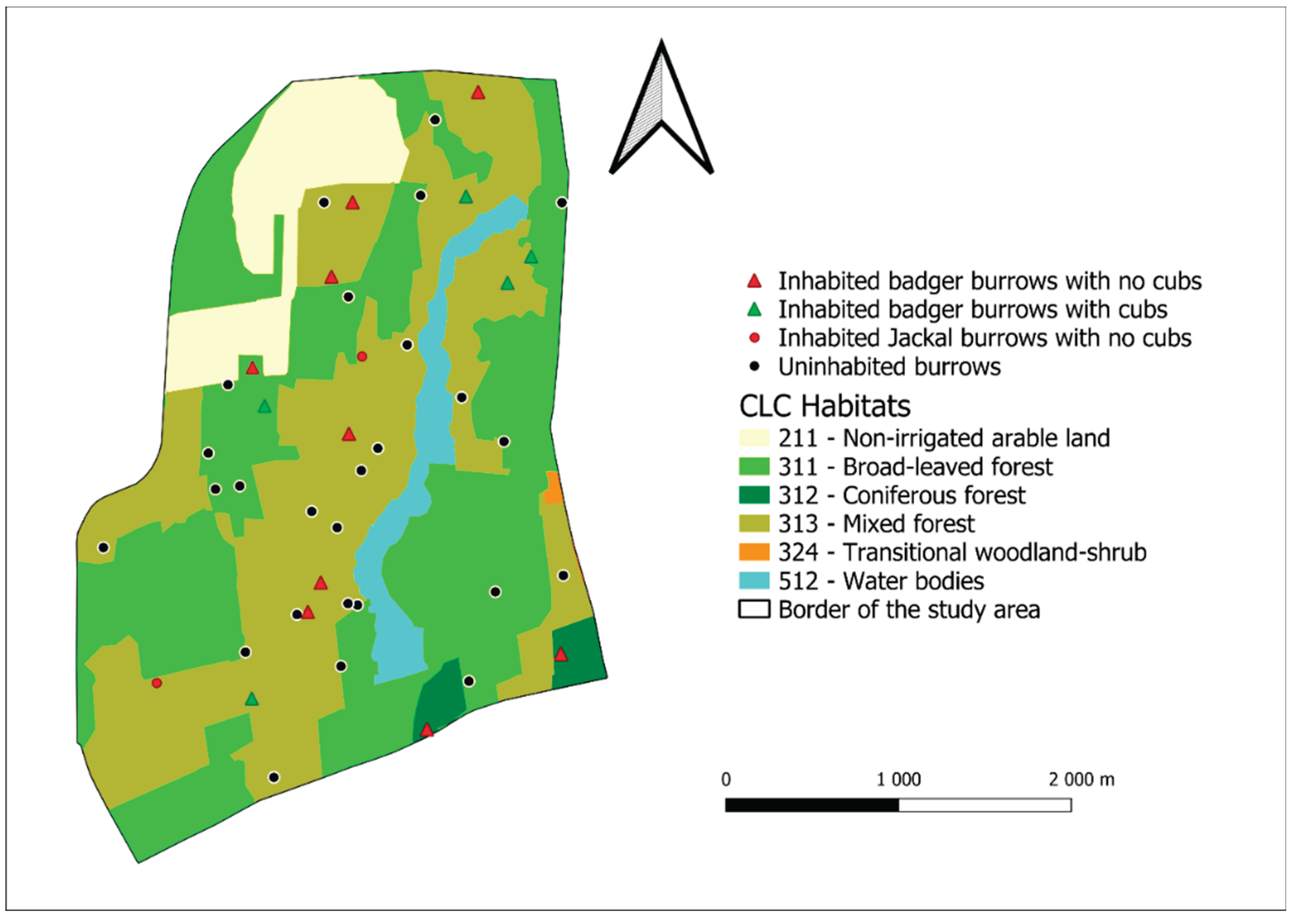

2.1. The Study Areas

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Burrow Density

3.1.1. Drávaszentes

3.1.1. Darány

3.2. Reproduction Results

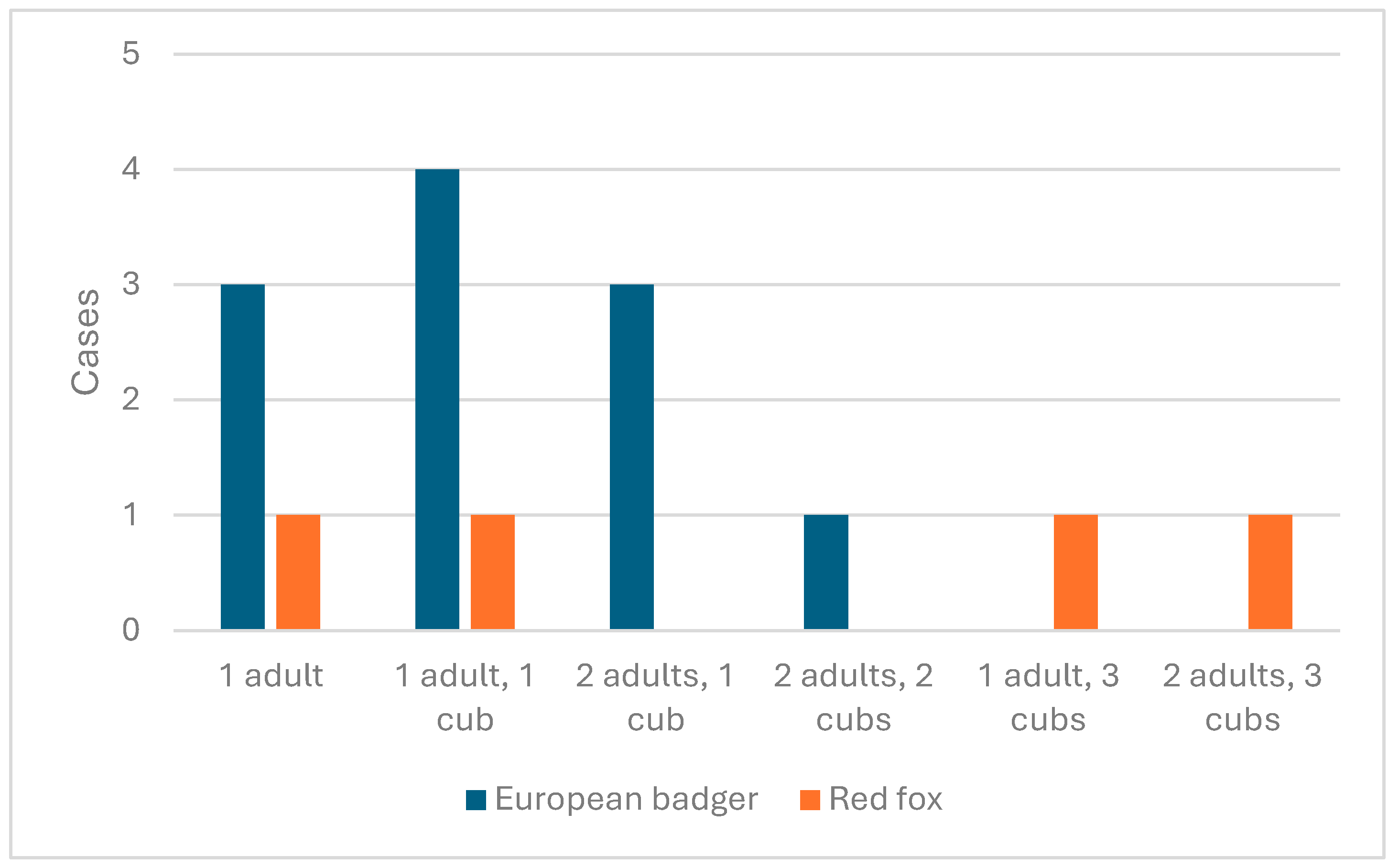

3.2.1. Drávaszentes Reproduction Results

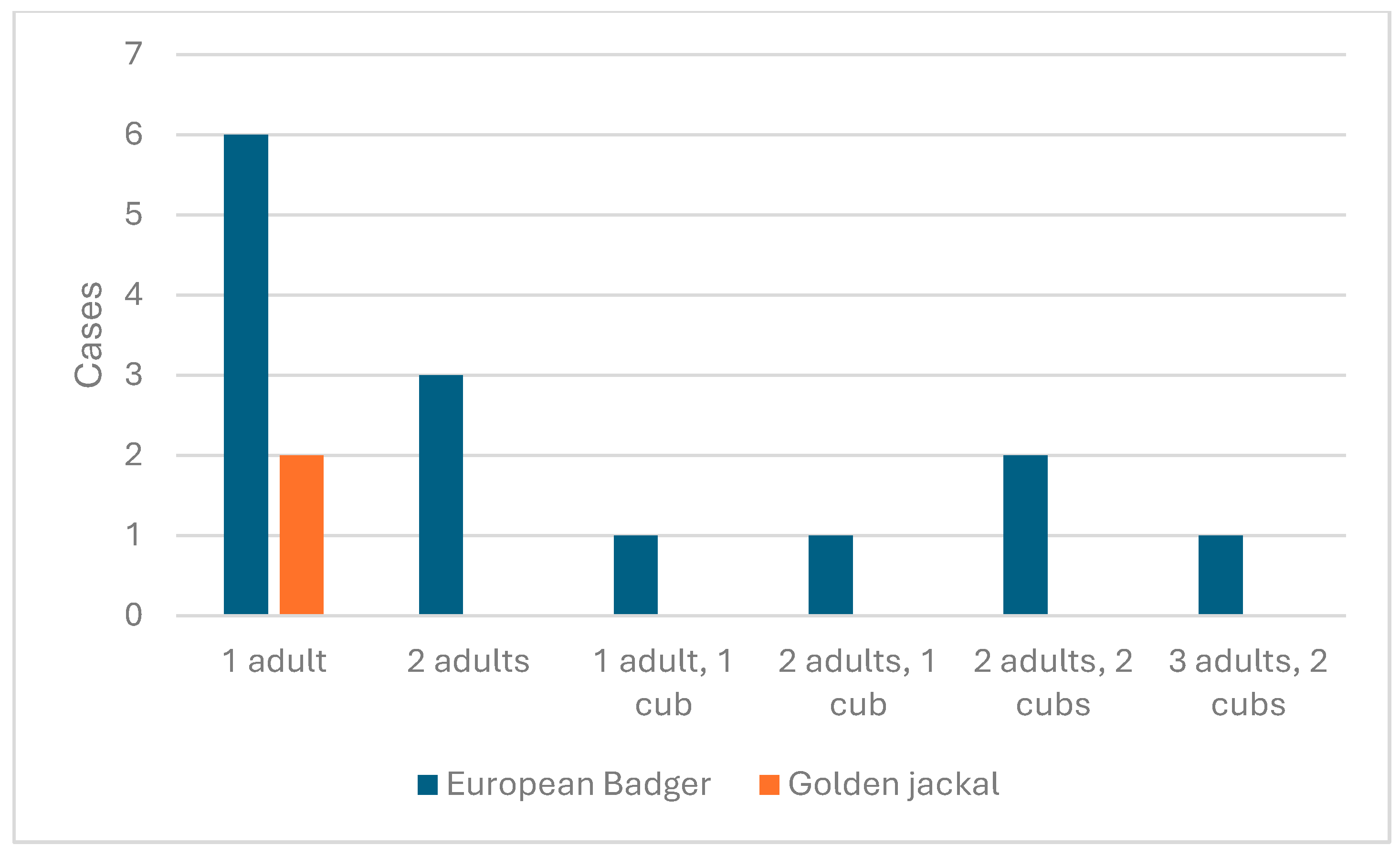

3.2.2. Darány Reproduction Results

3.3. Habitat Composition Preference Results for Badger

3.3.1. Drávaszentes

3.3.2. Darány

4. Discussion

4.1. Burrow Density

4.2. Individual Density

4.3. Cubs Per Burrow

4.4. Badger Habitat Composition Preference

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Habitat type | Comparison | U stat | U' stat | p value | n |

| 112 | Burrows with cubs - Burrows with no cubs | 7,000 | 17,000 | 0,355 | 11 |

| Burrows with cubs - random 1 | 31,000 | 33,000 | 0,957 | 16 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 2 | 32,000 | 32,000 | 0,957 | 16 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 3 | 24,000 | 40,000 | 0,423 | 16 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 4 | 28,000 | 36,000 | 0,700 | 16 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 5 | 31,000 | 33,000 | 0,957 | 16 | |

| 211 | Burrows with cubs - Burrows with no cubs | 11,000 | 13,000 | 0,921 | 11 |

| Burrows with cubs - random 1 | 23,000 | 41,000 | 0,382 | 16 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 2 | 21,000 | 43,000 | 0,279 | 16 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 3 | 21,000 | 43,000 | 0,279 | 16 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 4 | 24,000 | 40,000 | 0,442 | 16 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 5 | 7,000 | 57,000 | 0,007 | 16 | |

| 231 | Burrows with cubs - Burrows with no cubs | 6,000 | 18,000 | 0,279 | 11 |

| Burrows with cubs - random 1 | 23,500 | 40,500 | 0,400 | 16 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 2 | 26,500 | 37,500 | 0,598 | 16 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 3 | 29,500 | 34,500 | 0,833 | 16 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 4 | 29,500 | 34,500 | 0,833 | 16 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 5 | 23,000 | 41,000 | 0,371 | 16 | |

| 243 | Burrows with cubs - Burrows with no cubs | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 11 |

| Burrows with cubs - random 1 | 29,000 | 35,000 | 0,783 | 16 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 2 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 16 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 3 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 16 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 4 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 16 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 5 | 29,000 | 35,000 | 0,783 | 16 | |

| 311 | Burrows with cubs - Burrows with no cubs | 6,000 | 18,000 | 0,279 | 11 |

| Burrows with cubs - random 1 | 32,000 | 32,000 | 1,000 | 16 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 2 | 29,000 | 35,000 | 0,798 | 16 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 3 | 30,000 | 34,000 | 0,879 | 16 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 4 | 32,000 | 32,000 | 1,000 | 16 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 5 | 30,000 | 34,000 | 0,879 | 16 |

| Habitat type | Comparison | U stat | U' stat | p value | n |

| 211 | Burrows with cubs - Burrows with no cubs | 24,500 | 25,500 | 1,000 | 15 |

| Burrows with cubs - random 1 | 4,500 | 20,500 | 0,116 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 2 | 11,000 | 14,000 | 0,828 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 3 | 11,000 | 14,000 | 0,828 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 4 | 11,000 | 14,000 | 0,828 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 5 | 11,000 | 14,000 | 0,828 | 10 | |

| 231 | Burrows with cubs - Burrows with no cubs | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 15 |

| Burrows with cubs - random 1 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 2 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 3 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 4 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 5 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 10 | |

| 311 | Burrows with cubs - Burrows with no cubs | 18,000 | 32,000 | 0,440 | 15 |

| Burrows with cubs - random 1 | 5,000 | 20,000 | 0,151 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 2 | 3,000 | 22,000 | 0,056 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 3 | 12,000 | 13,000 | 1,000 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 4 | 12,000 | 13,000 | 1,000 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 5 | 9,000 | 16,000 | 0,548 | 10 | |

| 312 | Burrows with cubs - Burrows with no cubs | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 15 |

| Burrows with cubs - random 1 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 2 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 3 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 4 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 5 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 10 | |

| 313 | Burrows with cubs - Burrows with no cubs | 25,000 | 25,000 | 1,000 | 15 |

| Burrows with cubs - random 1 | 2,000 | 23,000 | 0,032 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 2 | 1,000 | 24,000 | 0,016 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 3 | 11,000 | 14,000 | 0,841 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 4 | 8,000 | 17,000 | 0,421 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 5 | 8,000 | 17,000 | 0,421 | 10 | |

| 324 | Burrows with cubs - Burrows with no cubs | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 15 |

| Burrows with cubs - random 1 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 2 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 3 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 4 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 5 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 10 | |

| 512 | Burrows with cubs - Burrows with no cubs | 9,000 | 16,000 | 0,521 | 15 |

| Burrows with cubs - random 1 | 9,000 | 16,000 | 0,521 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 2 | 7,000 | 18,000 | 0,284 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 3 | 6,000 | 19,000 | 0,199 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 4 | 9,000 | 16,000 | 0,521 | 10 | |

| Burrows with cubs - random 5 | 10,000 | 15,000 | 0,674 | 10 |

| Category | Habitat type | MIN | Q1 | MED | Q3 | MAX |

| Burrows with cubs | 112 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 1,56 | 22,11 |

| 211 | 5,55 | 8,87 | 18,42 | 21,44 | 37,77 | |

| 231 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 4,62 | 12,94 | 23,82 | |

| 243 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,27 | 3,76 | |

| 311 | 7,58 | 11,36 | 18,43 | 26,00 | 42,06 | |

| Burrows with no cubs | 112 | 0,00 | 3,16 | 6,32 | 6,65 | 6,98 |

| 211 | 14,78 | 16,91 | 19,03 | 19,56 | 20,09 | |

| 231 | 13,79 | 16,19 | 18,58 | 18,97 | 19,35 | |

| 243 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | |

| 311 | 3,79 | 7,44 | 11,09 | 13,98 | 16,87 | |

| random 1 | 112 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 2,57 |

| 211 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 8,70 | 8,97 | 11,64 | |

| 231 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 4,07 | 15,66 | 20,12 | |

| 243 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | |

| 311 | 4,09 | 4,09 | 14,95 | 17,25 | 21,51 | |

| random2 | 112 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 2,05 | 11,92 |

| 211 | 0,00 | 2,54 | 9,19 | 21,96 | 30,28 | |

| 231 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 10,36 | 18,01 | 36,74 | |

| 243 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | |

| 311 | 1,39 | 16,87 | 21,00 | 31,56 | 45,53 | |

| random 3 | 112 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 3,84 | 8,32 | 13,51 |

| 211 | 0,00 | 0,32 | 9,72 | 17,91 | 43,72 | |

| 231 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 4,99 | 14,11 | 18,51 | |

| 243 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | |

| 311 | 0,00 | 10,18 | 19,80 | 29,25 | 50,22 | |

| random 4 | 112 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 14,78 |

| 211 | 0,00 | 0,90 | 12,92 | 20,12 | 48,92 | |

| 231 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 8,20 | 18,62 | 28,89 | |

| 243 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | |

| 311 | 1,30 | 7,86 | 20,35 | 39,85 | 49,04 | |

| random 5 | 112 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,92 | 17,63 |

| 211 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,64 | 3,12 | 27,23 | |

| 231 | 0,00 | 0,86 | 15,39 | 36,75 | 46,52 | |

| 243 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 4,89 | |

| 311 | 0,04 | 8,39 | 16,14 | 44,99 | 49,47 |

| Category | Habitat type | MIN | Q1 | MED | Q3 | MAX |

| Burrows with cubs | 211 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,09 | 8,12 |

| 311 | 9,56 | 10,02 | 19,58 | 25,38 | 27,70 | |

| 312 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | |

| 313 | 14,39 | 18,88 | 23,61 | 32,45 | 40,66 | |

| 512 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 5,97 | 7,04 | 7,66 | |

| Burrows with no cubs | 211 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 4,78 | 23,10 |

| 311 | 1,54 | 6,75 | 15,03 | 23,40 | 30,15 | |

| 312 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 25,37 | |

| 313 | 0,00 | 16,35 | 24,33 | 36,74 | 48,46 | |

| 512 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,11 | 1,69 | 6,21 | |

| random 1 | 211 | 0,00 | 0,49 | 17,34 | 20,10 | 23,80 |

| 231 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,23 | |

| 311 | 16,65 | 24,45 | 28,45 | 28,77 | 30,11 | |

| 312 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | |

| 313 | 0,00 | 8,43 | 9,53 | 11,95 | 20,96 | |

| 512 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 9,82 | |

| random2 | 211 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 32,57 |

| 231 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 7,30 | |

| 311 | 10,36 | 29,10 | 31,24 | 34,94 | 41,73 | |

| 312 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 3,51 | 12,19 | |

| 313 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 8,49 | 9,17 | 15,84 | |

| 324 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 1,77 | 6,12 | |

| 512 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 6,80 | |

| random 3 | 211 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 29,80 |

| 231 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 1,66 | |

| 311 | 7,38 | 10,38 | 14,09 | 27,33 | 43,76 | |

| 312 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,11 | |

| 313 | 4,67 | 6,35 | 22,89 | 39,11 | 42,83 | |

| 324 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | |

| 512 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,73 | |

| random 4 | 211 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 11,23 |

| 231 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | |

| 311 | 1,35 | 11,60 | 21,62 | 24,53 | 35,37 | |

| 312 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 36,81 | |

| 313 | 12,04 | 14,46 | 14,84 | 27,29 | 27,29 | |

| 324 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,01 | |

| 512 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 11,33 | |

| random 5 | 211 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 12,38 |

| 231 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | |

| 311 | 11,46 | 16,60 | 23,95 | 25,43 | 43,31 | |

| 312 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,46 | |

| 313 | 0,00 | 13,89 | 14,95 | 26,98 | 33,62 | |

| 324 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 0,00 | |

| 512 | 0,00 | 0,00 | 6,91 | 9,38 | 11,79 |

References

- Prugh, Laura; Stoner, Chantal; Epps, Clinton; Bean, William; Ripple, William; Laliberte, Andrea; Brashares, Justin. The Rise of the Mesopredator. Aspen Bibliography 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemer, Gary W.; Gompper, Matthew E.; Van Valkenburgh, Blaire. The Ecological Role of the Mammalian Mesocarnivore. BioScience 2009, Volume 59(Issue 2), Pages 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, Euan; Johnson, Christopher. Predator interactions, mesopredator release and biodiversity conservation. Ecology letters 2009, 12, 982–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csányi, S.; Márton, M.; Bőti, Sz.; Schally, G. Vadgazdálkodási Adattár - 2024/2025. vadászati év; MATE VTI, Országos Vadgazdálkodási Adattár: Gödöllő, 2025; p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://jogkodex.hu/jsz/2001_90_fvm_rendelet_9682074 (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Heltai, M.; Torbó, L.T.; Lanszki, J.; Szabó, L. Az aranysakál (Canis aureus L. 1758) állománynagyságának vizsgálata közvetlen megfigyelések alapján. Tájökológiai Lapok 2012, 10(2), 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanszki, J.; Heltai, M.; Heltai, M. 2010: Eurázsiai borz (Meles meles Linnaeus, 1758). In Emlős ragadozók Magyarországon; Mezőgazda Kiadó: Budapest, 2010; pp. 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bijl, H; Schally, G; Márton, M; Heltai, M; Csányi, S. From invaders to residents: The golden jackal (Canis aureus) expansion in Hungary since the mid-1990s. PLOS ONE 2024, 19(7), e0306489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakonczay Z. (szerk.) 1989: Vörös Könyv. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest.

- Szabó, L.; Heltai, M.; Szűcs, E.; Lanszki, J.; Lehoczki, R. Expansion range of golden jackal in Hungary between 1997 and 2006. Mammalia 2009, 73, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heltai, M.; Bíró, Zs.; Szemethy, L. : A borz terjeszkedése Magyarországon 1988 és 2000 között. Vadbiológia 2001, 8, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Takács, A.; Szemethy, L.; Takács, A. A.; Takács, P. T.; Heltai, M. Adatok az eurázsiai borz (Meles meles) parazitákkal való fertőzöttségéről Magyarországon. Magyar Állatorvosok Lapja 2012, 134(2), 106–110. [Google Scholar]

- Csányi, S. (2007): Vadbiológia. Budapest: Mezőgazda Kiadó, 135 p.

- Leopold, A. (Szerk.) (1933): Game management. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 481 p.

- Heltai, M. 2016: Ragadozóemlős-fajok monitorozási módszereinek fejlesztése, és a tudatos ragadozó-gazdálkodás megalapozása az aranysakál, az eurázsiai borz és a vörös róka esetében. Akadémiai nagydoktori mű, Szent István Egyetem.

- Meia, J. S.; Weber, J. M. Characteristics and distribution of breeding dens of the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) in a mountainous habitat. Mammalian Biology 1992, 57, 137–143. [Google Scholar]

- Goszczyński, J.; Wójtowicz, I. Annual dynamics of den use by red foxes Vulpes vulpes and badgers Meles meles in central Poland. Acta theriologica 2001, 46(4), 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márton, M. Az európai borz és a vörös róka kotorékhely-kompetenciójának vizsgálata különböző terepbiológiai módszerekkel. Doktori dolgozat (Phd), Szent István Egyetem, Vadbiológiai és Vadgazdálkodási Tanszék, Gödöllő, 2018; p. 104. [Google Scholar]

- Heltai M. (Szerk.) (2010): Emlős ragadozók Magyarországon. Budapest: Mezőgazda Kiadó, 240 p.

- Jensen, P. Lidt om gravlingen. Naturens Verden 1959, 11, 289–320. [Google Scholar]

- Kruuk H. (Szerk.) (1989): The social badger. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 155 p.

- Neal E., Cheeseman C. (Szerk.) (1996): Badgers. London: T and AD Poyser Ltd., 271 p.

- Bang, P.; Dahlström, P. Állatnyomok és -jelek; M-érték Kiadó Kft.: Budapest, 2006; p. 264. [Google Scholar]

- Delahay, R. J.; Ward, A. I.; Walker, N.; Long, B.; Cheeseman, C. L. : Distribution of badger latrines in a high-density population: habitat selection and implications for the transmission of bovine tuberculosis to cattle. Journal of Zoology 2007, 272(3), 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trolliet, Franck; Huynen, Marie-Claude; Vermeulen, Cédric; Hambuckers, Alain. Use of camera traps for wildlife studies. A review. Biology Agriculture Science Environnement 2014, 18, 446–454. [Google Scholar]

- Márton, M.; Markolt, F.; Szabó, L.; Heltai, M. Niche segregation between two medium-sized carnivores in a hilly area of Hungary. Annales Zoologici Fennici 2014, Vol. 51(No. 5), 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosztra, B.; Büttner, G.; Hazeu, G.; Arnold, S. (2017): Updated CLC illustrated nomenclature guidelines. European Topic Centre on Urban, land and soil systems; ETC/ULS. ETC/ULS.

- Judge, J.; Wilson, G.; Macarthur, R.; et al. Density and abundance of badger social groups in England and Wales in 2011–2013. Sci Rep 2014, 4, 3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, Neil; Etherington, Thomas; Wilson, Gavin; Montgomery, Ian; Mcdonald, Robbie; Ian, W. Monitoring and population estimation of the European badger Meles meles in Northern Ireland. Wildlife Biology 2011, 18, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, Rafał; BUNEVICH, Aleksei; Jedrzejewska, Bogumila. Badger density and distribution of setts in Bialowieza Primeval Forest (Poland & Belrus) compared to other Eurasian populations. Acta Theriologica 2000, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.; Rosalino, L.M.; Alcobia, S.; Santos-Reis, M. Sett Use, Density and Breeding Phenology of Badgers in Mediterranean Agro-Sylvo-Pastoral Systems. Animals 2021, 11, 2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigaux, Pierre; Chanu, Cedric. Eurasian Badger (Meles meles) density and setts distribution in a rural landscape of Massif Central (Puy-de-Dome, France). Revue d Ecologie 2012, 67, 339–347. [Google Scholar]

- Kozák, L.; Heltai, M. (2006): Distribution and habitat selection of badgers in the region of Erdőspuszták (Eastern Hungary). Anale Universitatii din Oradea, Fascicula Biologie, Tom. XIII. 48-51 p.

- Brochier, B. Emplacement et densite des terriers de mise-bas du renard roux (Vulpes vulpesL.) en peripherie bruxelloise. Cahiers d'Ethologie appliquee 1989, 9, 495–508. [Google Scholar]

- Alberto, Meriggi; Paola, Rosa. Factors affecting the distribution of fox dens in northern Italy / Fattori influenzanti la distribuzione delle tane di volpe ( Vulpes vulpes ) in Italia settentrionale. Hystrix: the Italian Journal of Mammalogy 1991, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, M. Den-site selection at multiple scales by the red fox (Vulpes vulpes subsp. montana) in apatchy human-dominated landscape. Global Ecology and Conservation. [CrossRef]

- Márton, Mihály & Markolt, Ferenc & Szabo, Laszlo & Heltai, Miklós. (2013). BURROW DENSITIES OF EURASIAN BADGER (MELES MELES) AND RED FOX (VULPES VULPES) IN BÖRZSÖNY MOUNTAINS. 2.

- acquier, M.; Vandel, JM.; Léger, F.; et al. Breaking down population density into different components to better understand its spatial variation. BMC Ecol Evo 2021, 21, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalino, L. M.; Macdonald, D. W.; Santos-Reis, M. : Spatial Structure And Land-Cover Use In A Low-Density Mediterranean Population Of Eurasian Badgers. Canadian Journal Of Zoology;P 2004, 82(9), 1493–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla, Eloy; Delibes, Miguel; Travaini, A.; Palomares, F. Physical and population parameters of Eurasian badgers (Meles meles L.) from Mediterranean Spain. Zeitschrift Fur Saugetierkunde-International Journal of Mammalian Biology 1999, 64, 269–276. [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo, Pelayo; González-Quirós, Pablo; Prieto, José M.; Etherington, Thomas R.; Gortázar, Christian; Balseiro, Ana. Generalizing and transferring spatial models: A case study to predict Eurasian badger abundance in Atlantic Spain. Ecological Modelling 2014, Volume 275, Pages 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauhala, Kaarina; Holmala, Katja; Lammers, Wiebke; Schregel, Julia. Home ranges and densities of medium-sized carnivores in south-east Finland, with special reference to rabies spread. Acta theriologica 2006, 51, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsø, L. K.; Dupont, P.; Rød-Eriksen, L.; Andersskog, I. P. Ø.; Ulvund, K. R.; Flagstad, Ø.; Bischof, R.; Eide, N. E. Estimating red fox density using non-invasive genetic sampling and spatial capture–recapture modelling. Oecologia 2022, 198(1), 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panek, M.; Bresiński, W. Red fox Vulpes vulpes density and habitat use in a rural area of western Poland in the end of 1990s, compared with the turn of 1970s. Acta Theriologica 2002, 47(4), 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selonen, V.; Brommer, J. E.; Klangwald, C.; Laaksonen, T. Successful invasion: camera trap distance sampling reveals higher density for invasive raccoon dog compared to native mesopredators . Biological Invasions 2024, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmento, P.; Cruz, J.; Eira, C.; Fonseca, C. Evaluation of camera trapping for estimating red fox abundance . Journal of Wildlife Management 2009, 73(7), 1207–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banea, O. C.; Krofel, M.; Červinka, J.; Gargarea, P.; Szabó, L. New records, first estimates of densities and questions of applied ecology for jackals in Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve and hunting terrains from Romania . Acta Zoologica Bulgarica 2012, 64(4), 353–366. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A; Mukherjee, A; Dookia, S; Kumara, HN. High resource availability and lack ofcompetition have increased population of a meso-carnivore. A case study of Golden Jackal in Keoladeo National Park, India. Mamm Res 2016, 61, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selimovic, A.; Schöll, E.M.; Bosseler, L.; et al. Habitat use of golden jackals (Canis aureus) in riverine areas of northern Bosnia and Herzegovina. Eur J Wildl Res 2021, 67, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krofel, Miha. Survey of golden jackals (Canis aureus L.) in Northern Dalmatia, Croatia: Preliminary results. Natura Croatica 2008, 17, 259–264. [Google Scholar]

- Krofel, M. Confirmed presence of territorial groups of golden jackals (Canis aureus) in Slovenia. Nat. Slo 2009, 11(1), 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trbojević, Igor; Trbojević, Tijana; Malešević, Danijela; Krofel, Miha. The golden jackal (Canis aureus) in Bosnia and Herzegovina: density of territorial groups, population trend and distribution range. Mammal Research 2018, 63, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauze-Gryz, D.; Gryz, J. Den-Dwelling Carnivores in Central Poland: Long-Term Trends in Abundance and Productivity. Diversity 2023, 15, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski, K; Ważna, A; Kurek, P; Cichocki, J; Gabryś, G. Reproduction success in European badgers, red foxes and raccoon dogs in relation to sett cohabitation. PLOS ONE 2020, 15(8), e0237642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biancardi, Carlo; Rigo, Valentina; Azzolini, Sonia; Gnoli, Claudio. Eurasian badger (meles meles) habitat and sett site selection in the northern Apennines. Natural History Sciences 2014, 1, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalino, L. M.; Macdonald, D. W.; Santos-Reis, M. : Spatial structure and land-cover use in a low-density Mediterranean population of Eurasian badgers. Canadian Journal of Zoology 2004, 82(9), 1493–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, T. C.; Hindenlang, K.; Imfeld, S. A habitat analysis of badger (Meles meles L.) setts in a seminatural forest. Mammalian Biology 2001, 66, 204–214. [Google Scholar]

- Balestrieri, A.; Remonti, L.; Prigioni, C. Habitat selection in a low-density badger Meles meles popula-tion: a comparison of radio-tracking and latrine sur-veys. Wildlife Biology 2009, 15, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myslajek, R.; Nowak, S.; Jedrzejewska, B. Distribution, characteristics and use of shelters by the Eurasian badger Meles meles along an altitudinal gradient in the Western Carpathians, S Poland. Folia Zoologica 2012, 61, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Linh San, E.; Ferrari, N.; Weber, J. M. : Socio-Spatial Organization Of Eurasian Badgers (Meles Meles) In A Low-Density Population Of Central Europe. Canadian Journal Of Zoology;P 2007, 85(9), 973–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Romero, C.; Virgós, E.; Escribano-Ávila, G.; Mangas, J. G.; Barja, I.; Pardavila, X. : Habitat Selection By European Badgers In Mediterranean Semiarid Ecosystems. Journal Of Arid Environments 2012, 76, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apeldoorn, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Vink, J.; Matyastik, Tomas. Dynamics of a local badger (Meles meles) population in the Netherlands over the years 1983-2001. Mammalian Biology - Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde 2006, 71, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgós, E.; Casanovas, J. G. Badger Meles Meles Sett Site Selection In Low Density Mediterranean Areas Of Central Spain. Acta Theriologica 1999, 44(2), 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Density (burrow/100 ha) | Reference |

| Hungary (Drávaszentes) | 1.05 | present study |

| Hungary (Darány) | 1.43 | present study |

| England and Wales | 0.49 | [28] |

| Northern Ireland | 0.56 | [29] |

| Poland / Belarus | 0,22 | [30] |

| Portugal | 1.05 | [31] |

| France | 0,45 | [32] |

| Hungary | 1,07 | [33] |

| Hungary (survey) | 0.32 | [33] |

| Country | Density (burrow/100 ha) | Reference |

| Hungary (Drávaszentes) | 0.38 | present study |

| Hungary (Darány) | 0 | present study |

| Switzerland | 0.33 | [16] |

| Belgium | 1 | [34] |

| Italy | 0.67 - average | [35] |

| Pakistan | 1.3 | [36] |

| Hungary (Bakony) | 3.66 | [37] |

| Hungary (Börzsöny) | 4.08 | [37] |

| Country | Density (individual/100 ha) | Reference |

| Hungary (Drávaszentes) | 1.44 | present study |

| Hungary (Darány) | 2.24 | present study |

| France | 3.84 | [38] |

| Portugal | 0.45 | [39] |

| Spain (Coto del Rey) | 0.67 | [40] |

| Spain (Reserva Biologica) Spain |

0.23 3.81 |

[40] [41] |

|

Finland |

2002 - 0.21 2003 - 0.26 |

[42] |

| Country | Density (individual/100 ha) | Reference |

| Hungary (Drávaszentes) | 0.48 | present study |

| Hungary (Darány) | 0 | present study |

|

Norway (Central) |

0.04 in 2016 0.10 in 2017 0.06 in 2018 |

[43] |

|

Norway (Southern) |

0.16 in 2017 0.09 in 2018 |

[43] |

|

Poland (Western) |

1.02 in the spring 1. 63 in early winter |

[44] (spotlight count method) |

|

Poland (Western) |

1.26 in winter |

[44] (track count method) |

| Finland (South) | 0.6 | [45] |

| Portugal (Central-East) | 0.61 | [46] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).