Submitted:

24 December 2025

Posted:

25 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. .Reagents and Instrument

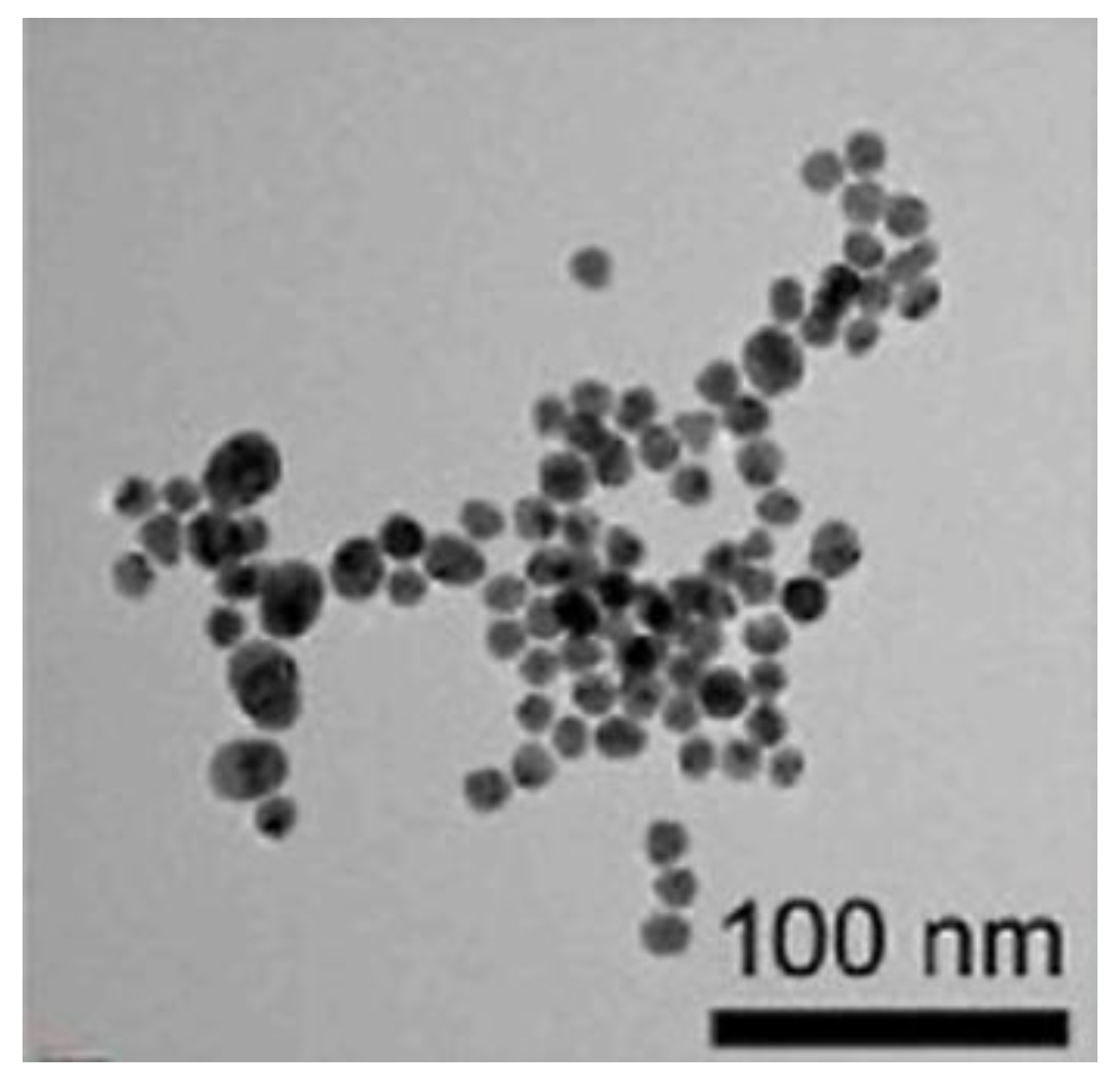

2.2. Preparation of AuNPs

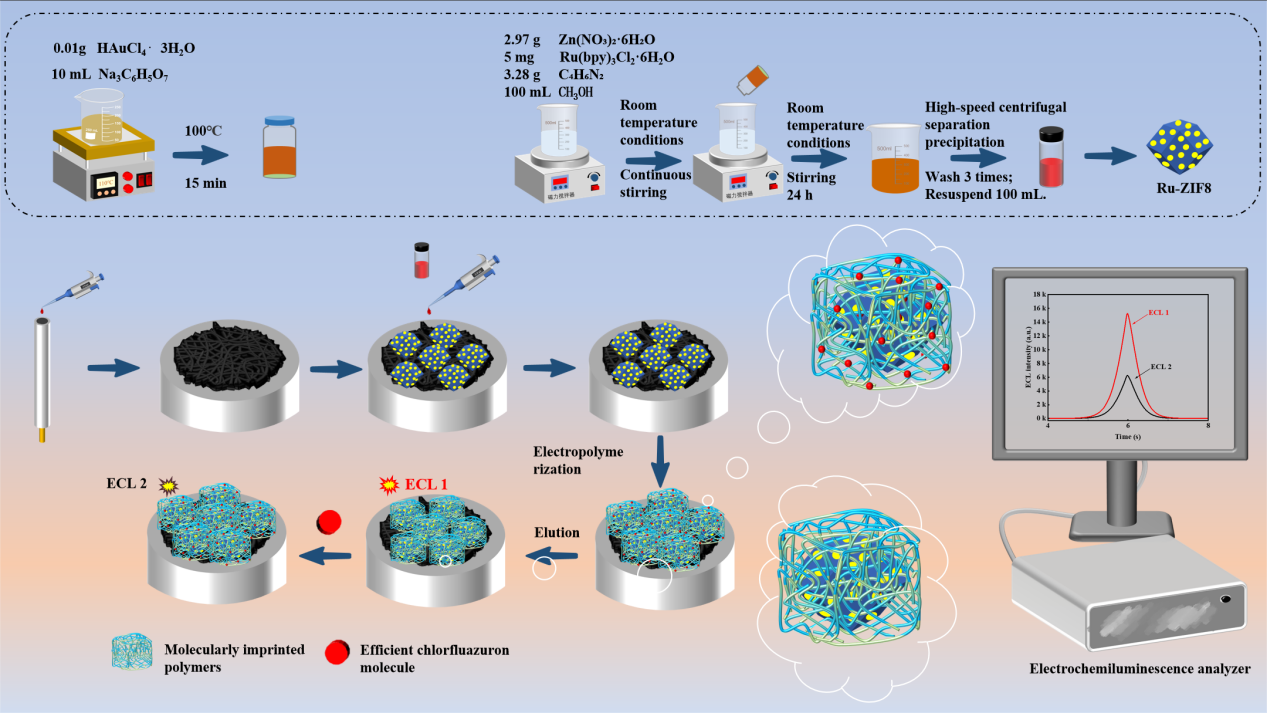

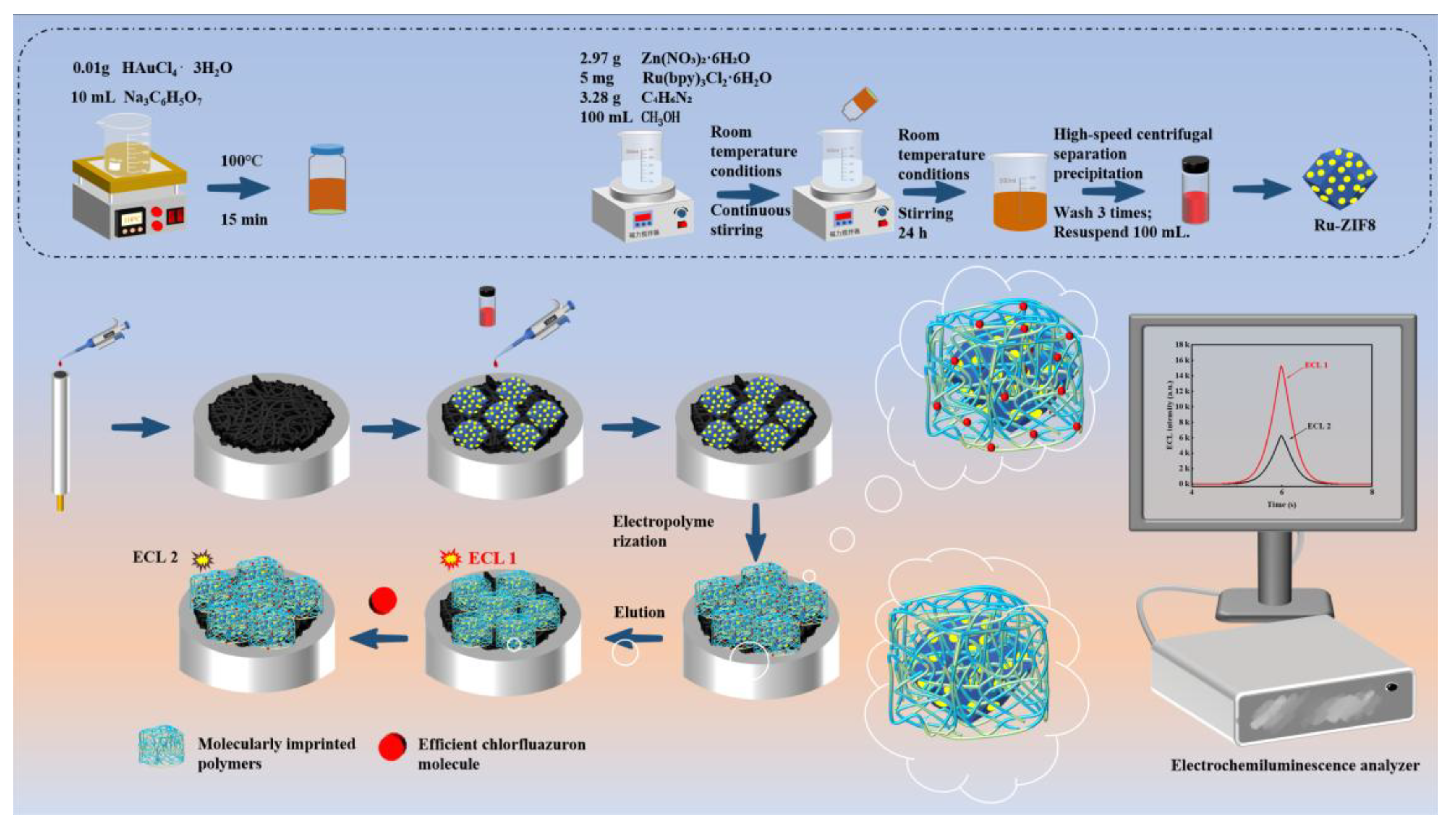

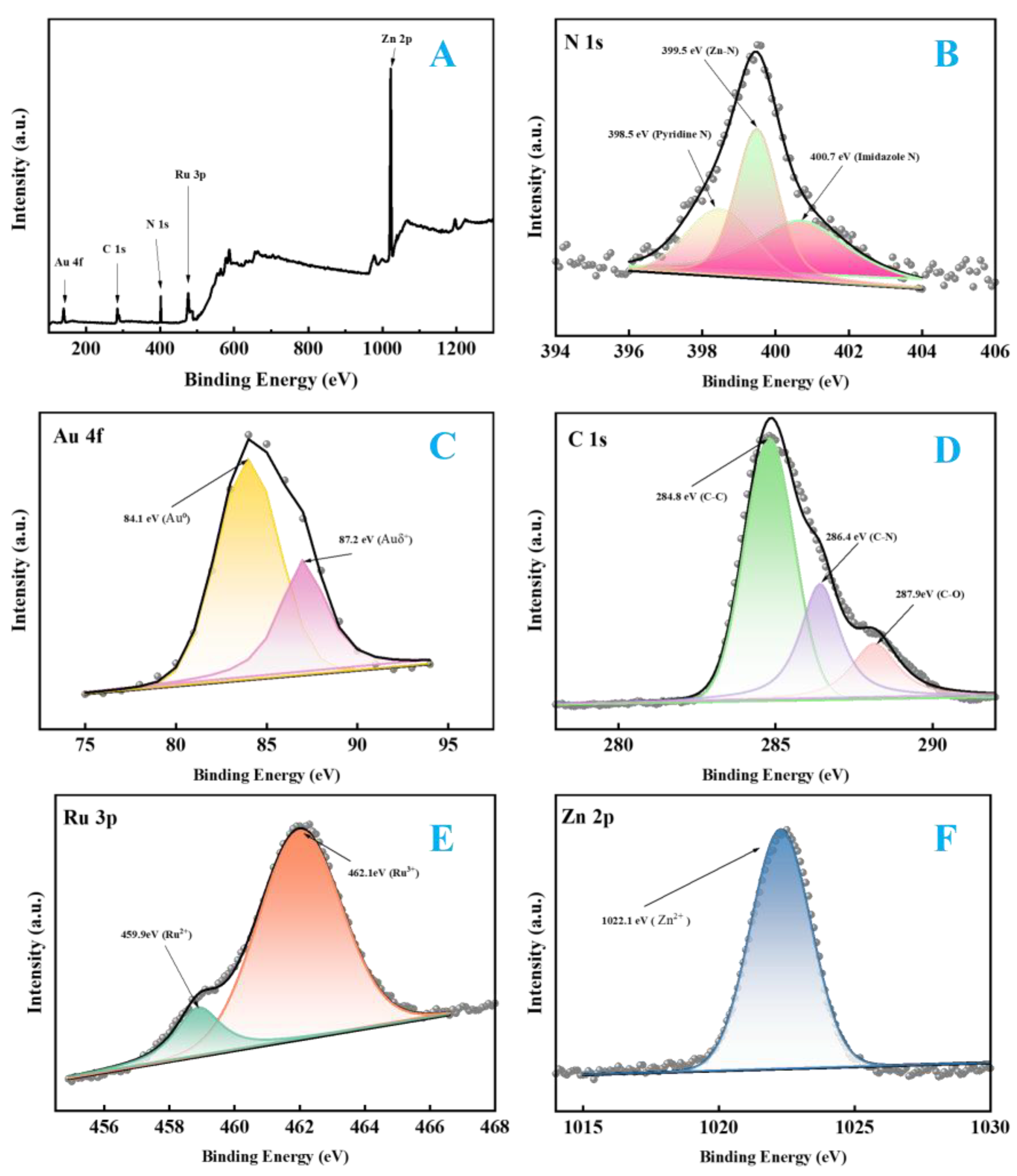

2.3. Preparation of AuNPs@Ru-ZIF8

2.4. Construction of Electrochemiluminescence Aptasensor

2.5. Electrochemiluminescence Measurement

2.6. Sample Pretreatment

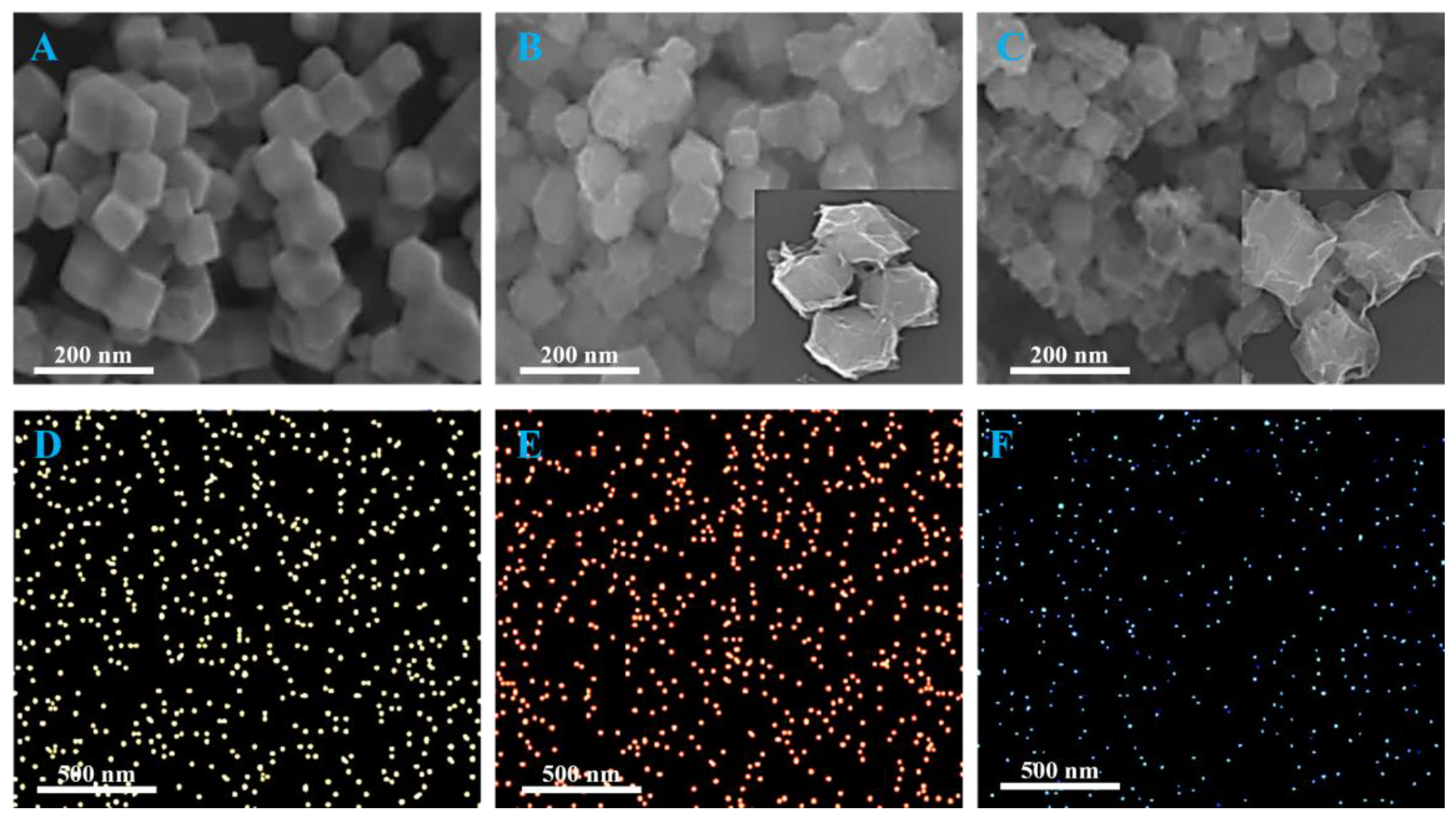

2.7. Phase and Structure Analysis of Experimental Materials

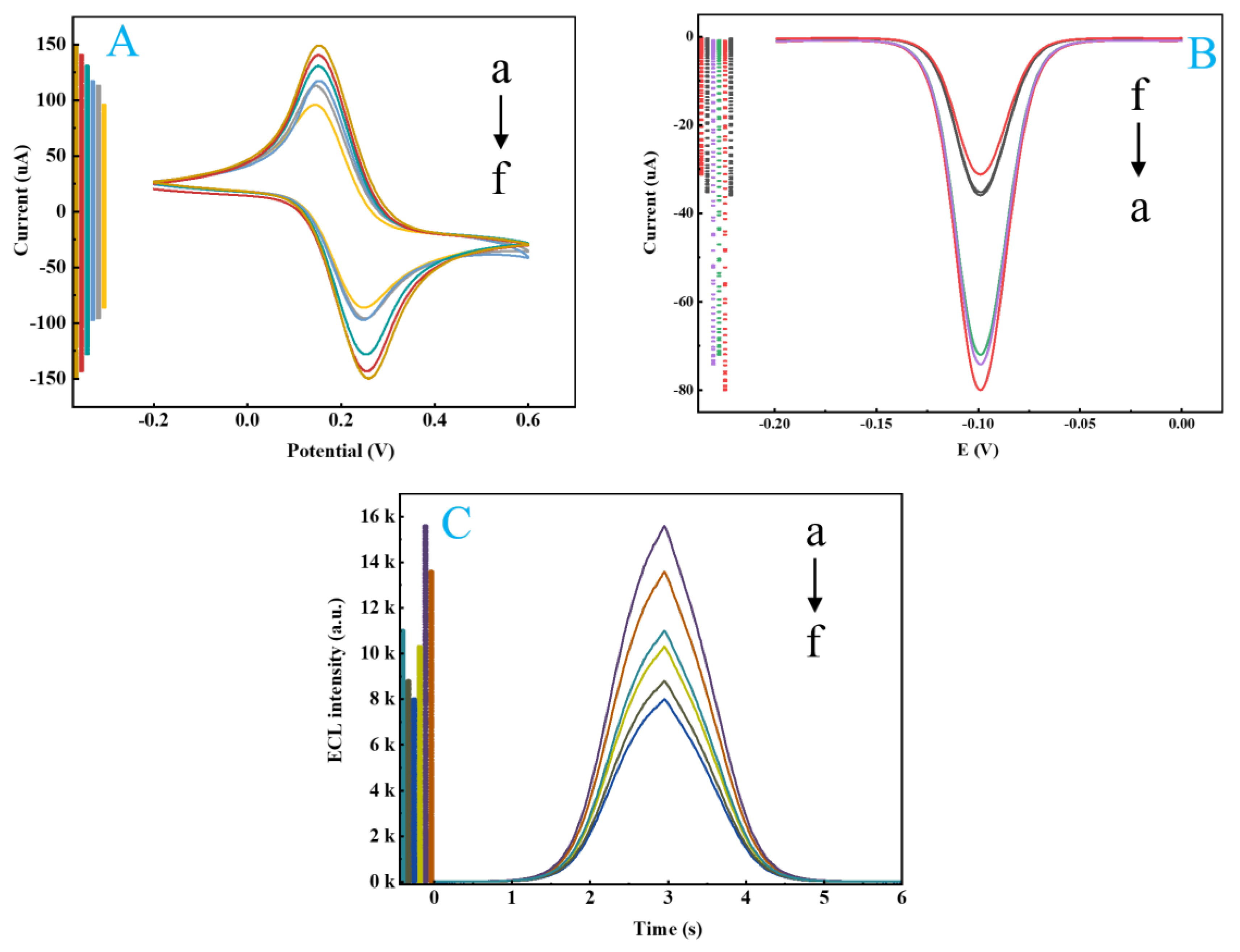

2.8. Electrochemical and Electrochemiluminescent Validation

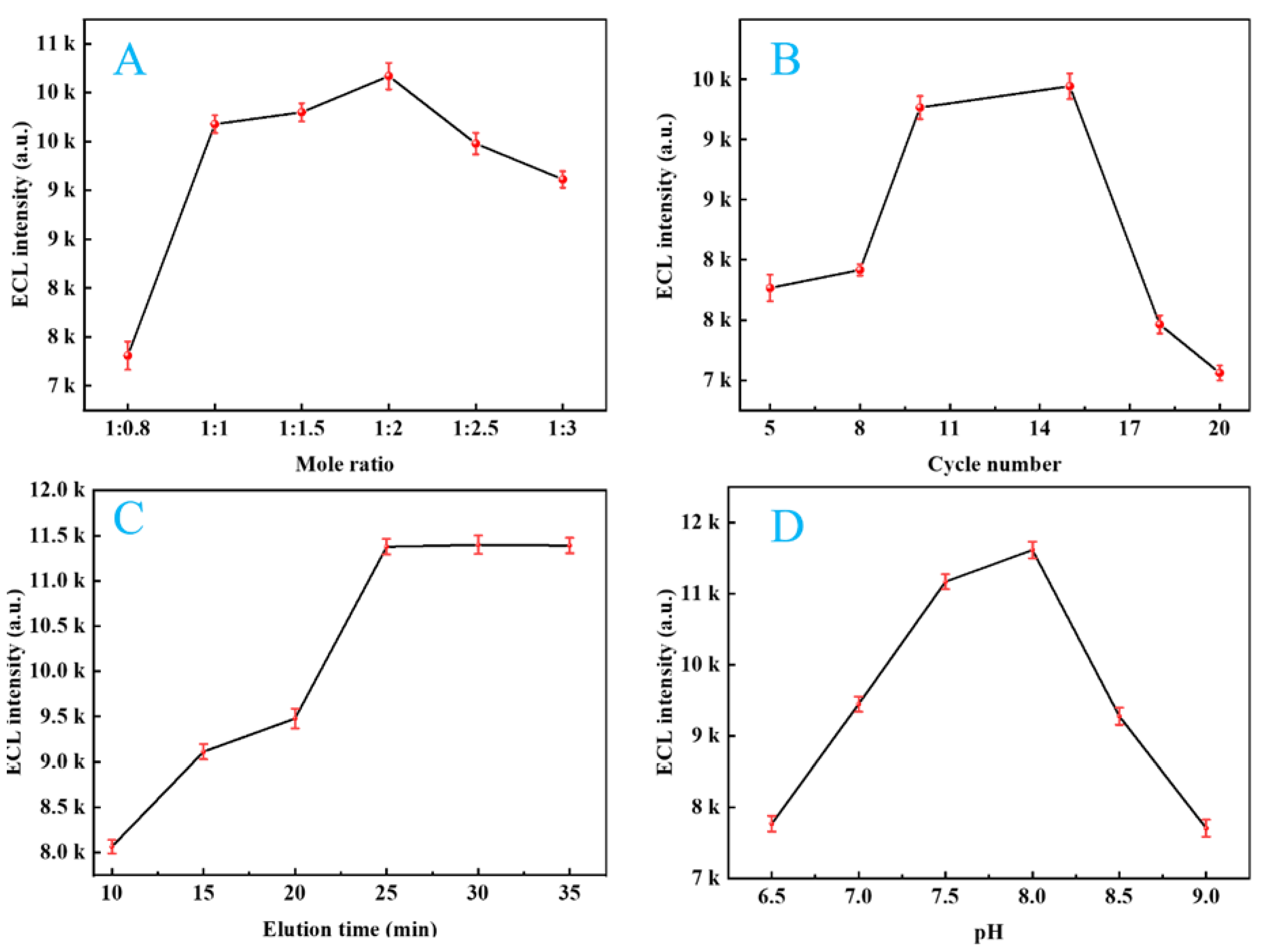

2.9. Optimizing Experimental Parameters

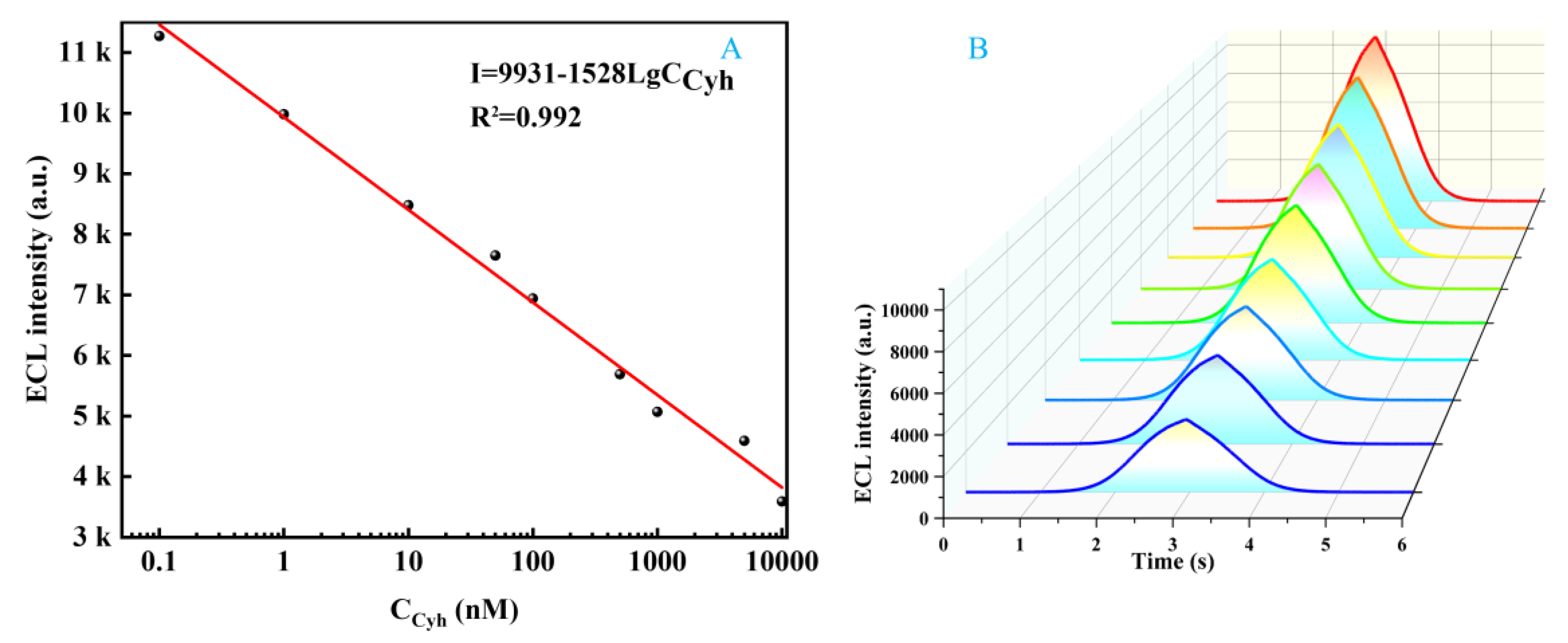

2.10. Aptasensor Performance Analysis

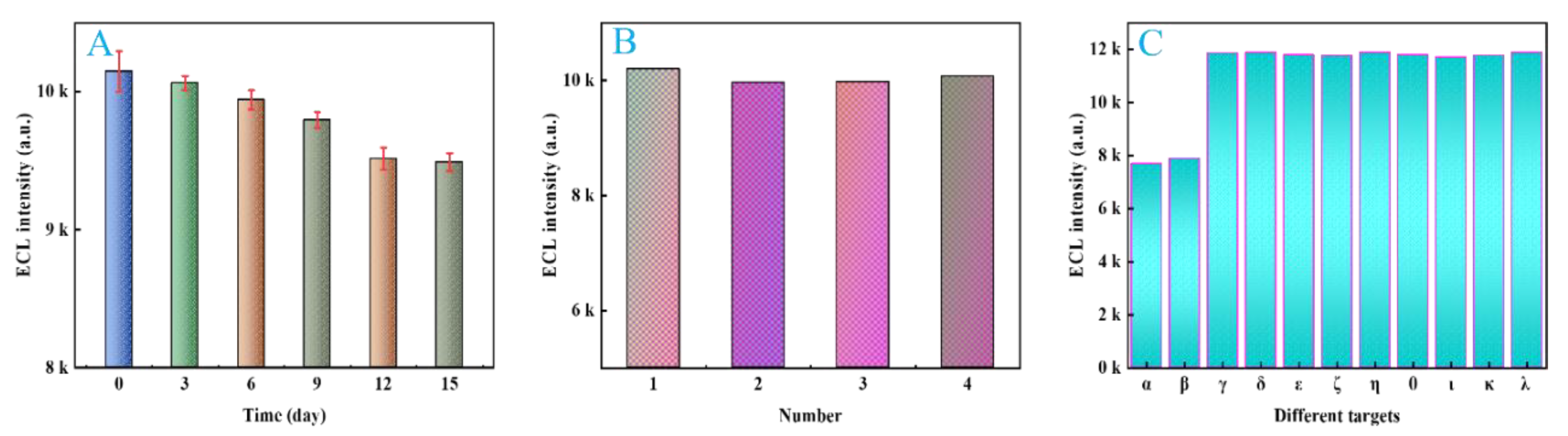

2.11. Stability, Reproducibility and Specificity

2.13. Analysis of Lycium barbarum L.

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- Fu, Yan; Yang, Ting; Zhao, Jian. Determination of eight pesticides in Lycium barbarum by LC-MS/MS and dietary risk assessment. Food Chemistry 2017, 218, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikac, L.; Kovačević, E.; Ukić, Š.; Raić, M.; Jurkin, T.; Marić, I.; Gotić, M.; Ivanda, M. Detection of multi-class pesticide residues with surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 252, 119478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, L.-J.; Lv, W.; Han, S.-H.; Zhang, F.-K.; Pan, J.-R. Determination of Organophosphorus Pesticides Based on Biotin-Avidin Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay. Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 2011, 39, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Dou, S.; Vriesekoop, F.; Geng, L.; Zhou, S.; Huang, J.; Sun, J.; Sun, X.; Guo, Y. Advances in signal amplification strategies applied in pathogenic bacteria apta-sensing analysis—A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1287, 341938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wang, H.; Li, P.; Li, C.; Li, D.; Dong, H.; Guo, Z.; Geng, L.; Zhang, X.; Fang, M.; et al. Metal-organic framework-based aptasensor utilizing a novel electrochemiluminescence system for detecting acetamiprid residues in vegetables. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2024, 259, 116371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyad, P.W.; Park, S.-J.; Ha, T.-J. Recent advances in biosensors based on metal-oxide semiconductors system-integrated into bioelectronics. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2024, 259, 116407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Fangyan; Wang, Peilin; Li, Zhenrun. PVDF-HFP/EMIM: Otf film-based self-supporting ECL sensing system with CB[8]/Cu NC host-guest strategy for piR-36743 detection in gastric cancer ascites [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 509, 161221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhoum, A.; Altintas, Z.; Devi, K.S.; Forster, R.J. Electrochemiluminescence biosensors for detection of cancer biomarkers in biofluids: Principles, opportunities, and challenges. Nano Today 2023, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Q.; Lv, L.; Liu, T.; Wang, X. A fluorescence-validated MIP-ECL sensor based on UiO66 loaded carbon nitride for detection of trace Patulin in series fruit products. Microchem. J. 2024, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Gu, X.; Zhang, S.; Zou, Y.; Yan, F. Magnetic graphene oxide and vertically-ordered mesoporous silica film for universal and sensitive homogeneous electrochemiluminescence aptasensor platform. Microchem. J. 2024, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiramoto, Kaoru; Hirano-Iwata, Ayumi; Ino, Kosuke; et al. Electrochemiluminescence of [Ru(bpy)3]2+/tri-n-propylamine to visualize different lipid compositions in supported lipid membranes[J]. Chemical Communications 2025, 61, 4495–4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Zhiwei; Ma, Jun. Electroactive MIPs/N, S-Mo2C/Ag NPs nanocomposites for dual-signal ratiometric electrochemical sensing of carbendazim. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2025, 1020, 179488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Su, M.; Yang, M.; Fang, X.; Wang, H.; Li, G. Synthesis and performance studies of functionalized metal-organic framework UiO-66 composites in water bodies. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2024, 159, 105512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Dong, H.; Geng, L.; Xu, R.; Liu, M.; Guo, Z.; Sun, J.; Sun, X.; Guo, Y. Rational design and controlled synthesis of metal-organic frameworks to meet the needs of electrochemical sensors with different sensing characteristics: An overview. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2024, 281, 111536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorgami, G.; Haddadi, S.A.; Okati, M.; Mekonnen, T.H.; Ramezanzadeh, B. In situ-polymerized and nano-hybridized Ti3C2-MXene with PDA and Zn-MOF carrying phosphate/glutamate molecules; toward the development of pH-stimuli smart anti-corrosion coating. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, A.; Fooladi, A.A.I.; Havaei, S.A.; Mahboobi, M.; Sedighian, H. Recent advances in aptamer discovery, modification and improving performance. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2024, 40, 101852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Dong, C.; Jiang, D.; Shan, X.; Chen, Z. Construction of electrochemiluminescence aptasensor for acetamiprid detection using flower-liked SnO2 nanocrystals encapsulated Ag3PO4 composite as luminophore. Microchem. J. 2023, 187, 108374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.-L.; Song, K.-H.; Xu, J.-T.; Wang, K.-Z.; Feng, X.-Z.; Han, G.-C.; Kraatz, H.-B. An electrochemical aptamer sensor for rapid quantification sulfadoxine based on synergistic signal amplification of indole and MWCNTs and its electrooxidation mechanism. Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 2024, 401, 135008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, H.; Li, Q.; Tian, Y.; Gao, X.; Zhang, W.; Sun, Z.; Mou, Y.; Sun, X.; Guo, Y.; et al. Development of a fluorescent sensor based on TPE-Fc and GSH-AuNCs for the detection of organophosphorus pesticide residues in vegetables. Food Chem. 2024, 431, 137067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Dong, S.; Yang, J.; Shi, Q.; Guan, L.; Sun, L.; Chen, Z.; Feng, J. Efficient and switchable aptamer “fluorescence off/on” method based on UiO-66@Cu for ultrasensitive detection of acetamiprid. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Wang, X.; Tian, Z.; Jia, F.; Wang, J.; Xie, L.; Lan, J.; Han, P.; Lin, H.; Huang, X.; et al. Controlled-release of cinnamaldehyde from MXene/ZIF8/gelatin composite coatings: An integrated strategy to combat implant-associated infection. Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2025, 251, 114615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Q.; Xu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, D.; Nie, G. A novel “on-off-on” electrochemiluminescence strategy based on RNA cleavage propelled signal amplification and resonance energy transfer for Pb2+ detection. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1290, 342218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Z.; Liu, Y.; Pan, M.; Tao, X.; Chen, Y.; Ma, P.; Zhuo, Y.; Song, D. AgInZnS quantum dots as anodic emitters with strong and stable electrochemiluminescence for biosensing application. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 228, 115219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Xu, S.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G. A highly stable voltammetric sensor for trace ofloxacin determination coupling molecularly imprinting film with AuNP and UiO-66 MOF dual-encapsulated black phosphorus nanosheets. Mater. Today Chem. 2024, 43, 102468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Jing; Lu, Lili; Fan, Zhaoyu; et al. A Molecularly Imprinted Polymer Sensor Based on the Electropolymerization of p-Aminothiophenol-Functionalized Au Nanoparticles Electrode for the Detection of Nonylphenol [J]. Biomedical and Environmental Sciences 2020, 33, 887–891. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Qiu, H.; Shen, H.; Pan, J.; Dai, X.; Yan, Y.; Pan, G.; Sellergren, B. Molecularly imprinted fluorescent hollow nanoparticles as sensors for rapid and efficient detection λ-cyhalothrin in environmental water. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 85, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, J.C.; Silva, J.P.; Zanoni, M.V.B.; de Andrade, A.R. High sensitive phosphorene and molecular imprinted polymers electrochemical sensor to determine benzene in oilfield-produced water. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 111703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Juan; Miao, Yanqing; Liu, Chunye; et al. Progress in the preparation and application of gold nanoparticles. Chemical Technology 1–12.

- Pham, T.B.; Bui, H.; Pham, V.H.; Do, T.C. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy based on Silver nano-dendrites on microsphere end-shape optical fibre for pesticide residue detection. Optik 2020, 219, 165172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito-Shida, S.; Saito, M.; Tsutsumi, T. Comparison of nitrogen and helium as carrier gases for determination of pesticide residues in foods via gas chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry with atmospheric pressure chemical ionization. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Su, H.; Liu, H.; Sun, B. A selectivity-enhanced fluorescence imprinted sensor based on yellow-emission peptide nanodots for sensitive and visual smart detection of λ-cyhalothrin. Anal. Chim. Acta 2023, 1255, 341124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Added amount (ng/ mL) | Method | detection value (ng/ mL) |

RSD (%) | Recovery rate (%) |

| 0 | LC-MS/MS ECL-MIPs |

0 0 |

- - |

- - |

| 10 | LC-MS/MS ECL-MIPs |

10.16 10.23±0.28 |

3.13 4.00 |

101.60 102.30 |

| 100 | LC-MS/MS ECL-MIPs |

107.02 106.50±4.60 |

5.10 4.55 |

107.02 116.50 |

| Source | ECL detection value | detection value (ng/mL) |

| Ningxia | 9170 | 1.42 |

| Gansu | 9020 | 1.79 |

| Qinghai | 9200 | 1.34 |

| Xinjiang | 8950 | 1.98 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).