1. Introduction

Oral lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory mucocutaneous disorder of immunological origin with varying severity and appearance. This condition affects approximately 2% of the general population, with an onset typically in the third and fifth decades of life, with twice the prevalence in females compared to males [

1]

.

The etiology of OLP remains unclear. Oxidative stress has been found to play a crucial role in its development. It is considered a multifactorial condition, with exacerbating agents contributing to this condition, including psychological stress, medications, and liver dysfunction. OLP is also associated with systemic conditions of dyslipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, hypothyroidism, and nutritional deficiencies like vitamin B12 deficiency or iron deficiency [

2,

3]

.

Pathogenesis of OLP results from an abnormal T cell-mediated immune response in which basal epithelial cells are recognized as foreign because of changes in the antigenicity of their cell surface, in which auto-cytotoxic CD8+ T cells trigger the apoptosis of oral epithelial cells [

4]

.

OLP typically presents with bilateral, symmetric white or red lesions. White lesions are usually painless, while red ones can cause significant pain and discomfort, impacting quality of life. It can appear in six distinct forms: reticular, plaque-like, atrophic, erosive/ulcerative, or papular. Due to its highly dynamic nature, the disease often goes through periods of relapse and remission in some cases [

5]

.

Glutathione peroxidase (GpX) is crucial for keeping cells healthy and shielding them from oxidative stress. Mostly made in the liver, it plays a key role in the antioxidant system by balancing processes that generate reactive oxygen species (ROS). It also helps to metabolize and eliminate toxins, works as a cofactor for detoxifying enzymes, and regenerates antioxidants like vitamins C and E to their active forms, making them a reliable marker for tracking oxidative stress [

6]

.

Managing OLP is a challenging task due to persistent burning pain and flare-ups. The goal of treatment is to ease discomfort, control the severity and activity of oral lichen planus, and lower the risk of complications. Several treatment options are worth considering, including corticosteroids, retinoids, calcineurin inhibitors, herbals, and antioxidants [

7]

.

Corticosteroids are the gold standard treatment for this condition, with topical choices like triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% often recommended for relieving symptoms due to their strong anti-inflammatory effects. However, using them long-term can cause side effects such as candidiasis, dry mouth, and thinning of the mucosa. [

8]

.

Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs), like tacrolimus, are often used as a second-line option for more severe cases of this condition. Tacrolimus works as an immunosuppressant by blocking the calcineurin enzyme, which is important in cell-mediated immunity, stopping T lymphocyte activation by inhibiting calcineurin’s phosphatase activity and helping speed up healing. However, using it long-term can lead to side effects like a burning feeling where it’s applied, higher relapse rates, temporary changes in taste, occasional patches of hyperpigmentation, and, over time, a greater risk of developing oral squamous cell carcinoma.[

9]

.

Antioxidants are a newer approach in treating OLP patients by reducing the high oxidative stress found in these lesions. Selenium (Se), an essential nutrient, helps produce amino acids and enzymes by acting as a cofactor for the glutathione peroxidase enzyme, which protects cells and tissues from free radical damage through redox processes in cell metabolism, minimizing oxidative harm. Selenium also supports and strengthens the immune system and is well known for its powerful antioxidant effects [

10]

.

Recently, selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) have caught a lot of interest in the biomedical field, as their size, shape, and production method can greatly affect how they perform in the body. Among various synthesis approaches, “green” synthesis stands out for examining key traits like stability, uniformity, and biocompatibility, offering clear benefits over traditional methods. It’s eco-friendly, non-toxic, and cost-effective. Using vitamin C in green synthesis focuses on the main mechanisms, ideal conditions, and factors that influence nanoparticle quality and yield. This method not only enhances biocompatibility and stability but also reduces harmful byproducts through sustainable, safe, and environmentally friendly processes [

11]

.

The current study favors saliva over serum as a practical method for diagnosing oral diseases, highlighting benefits like quick, non-invasive collection, easy access, low cost, and simple handling and storage. Saliva also serves as the body’s first line of defense against oxidative stress and mirrors overall health; this agrees with the study’s findings by

Lee et al. (2009) [

12]

.

This clinical trial aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of selenium as an alternative or complementary topical treatment for patients with oral lichen planus, comparing it to topical triamcinolone, topical tacrolimus, and the combination therapies. The comparison was based on clinical assessments of pain scores, lesion sites, the severity, as well as the activity of different lichen planus lesions and salivary glutathione peroxidase enzyme levels in response to the different treatment approaches.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study Design

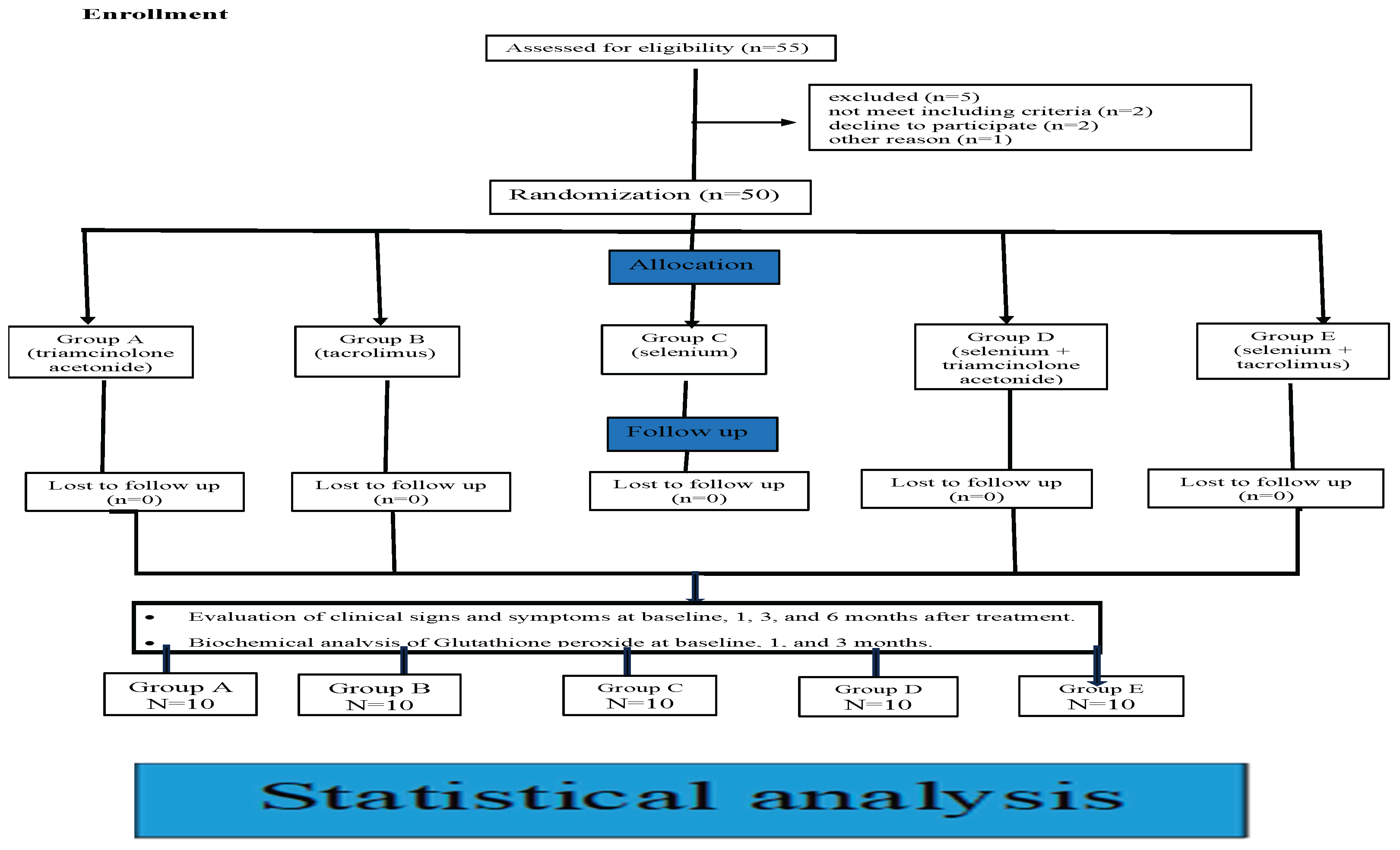

A five-arm randomized, blind, prospective clinical and biochemical trial was carried out on 50 patients with OLP lesions.

2.2. Patients

All patients were recruited from the outpatient clinic of the Dermatology Department, Assiut University Hospitals, and referred to oral Medicine clinics, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Al-Azhar University, Assiut branch.

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

Patients with a clinical diagnosis of OLP (presence of painful bilateral oral lesions. Diagnosis was based on taking the case history, clinical examination, and histopathological confirmation. All patients involved in this clinical trial had to be symptomatic and suffering from some degree of pain. Both males and females, above 30 years old, were enrolled in this clinical trial.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

Patients with OLP who are Smokers or tobacco users, Pregnant and lactating females. Any patient suffering from another autoimmune disease or who has a history of malignancy. Patients received previous treatment for lichen planus at least one week before the study. Patients with drug-induced or contact lichenoid reactions. Patients on anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

This clinical trial was conducted after receiving approval from the ethics committee at Al-Azhar University, Egypt, in November 2023 (

Ethical number: AUAREC2023011-1) and was registered under

Clinical Trial Registration Number: NCT06362005. All participants were clearly informed about the study and provided signed consent forms in accordance with the committee’s guidelines. They were treated following the principles of the modified Helsinki Code for human clinical studies (Association, 2013). [

13]

.

2.4. Sample Size Calculation and Power Analysis

Based on previous studies (*) and Using G power statistical power Analysis program (version 3.1.9.4) for sample size determination, A total sample size (n=50) was sufficient for each group (10 each) in the study to detect a large effect size (f)= 1.0251, with an actual power (1-β error) of 0.8 (80%) and a significance level (α error) 0.05 (5%) for two-tailed hypothesis test.

2.5. Grouping and Randomization

were performed by using the research randomizer website. Patients were randomly classified into five treatment groups, 10 patients each.

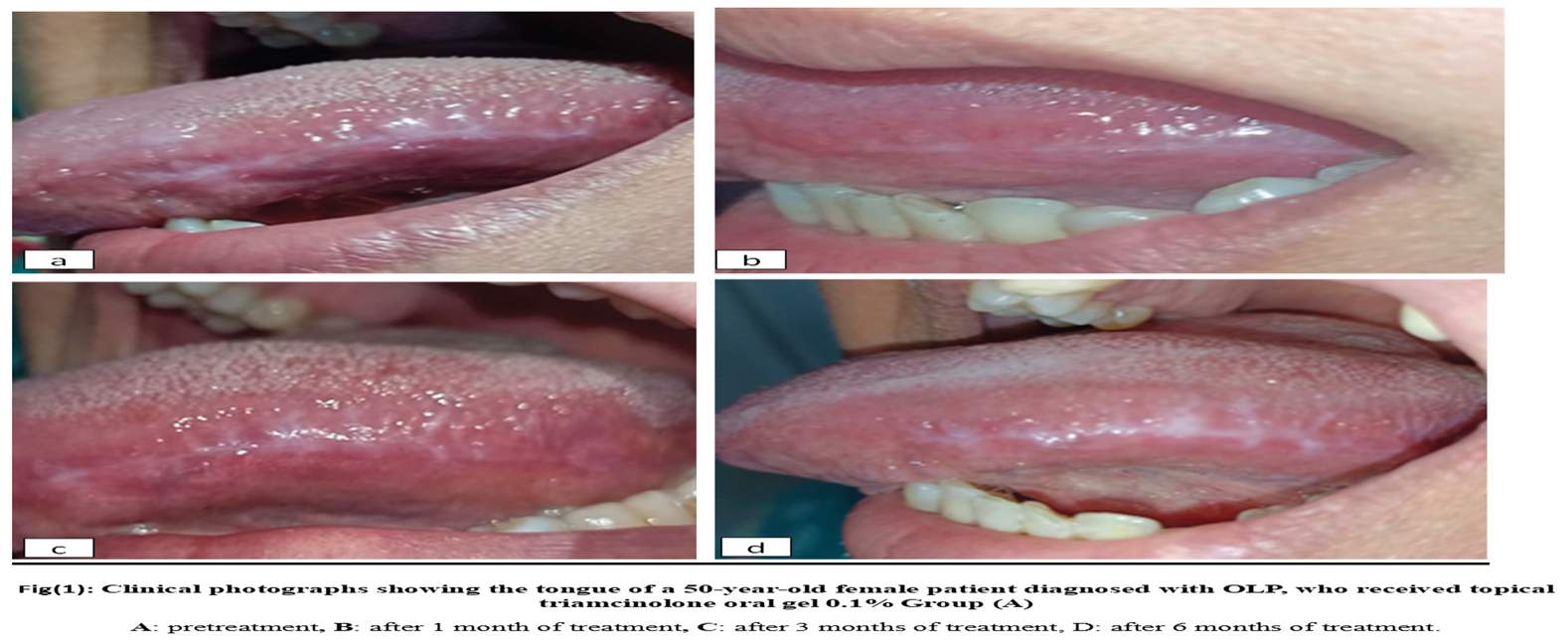

Group A: 10 patients with OLP received topical triamcinolone acetonide 0.1%. oral gel Kenacort-A-Orabase1® four times per day for six weeks." Figure 1

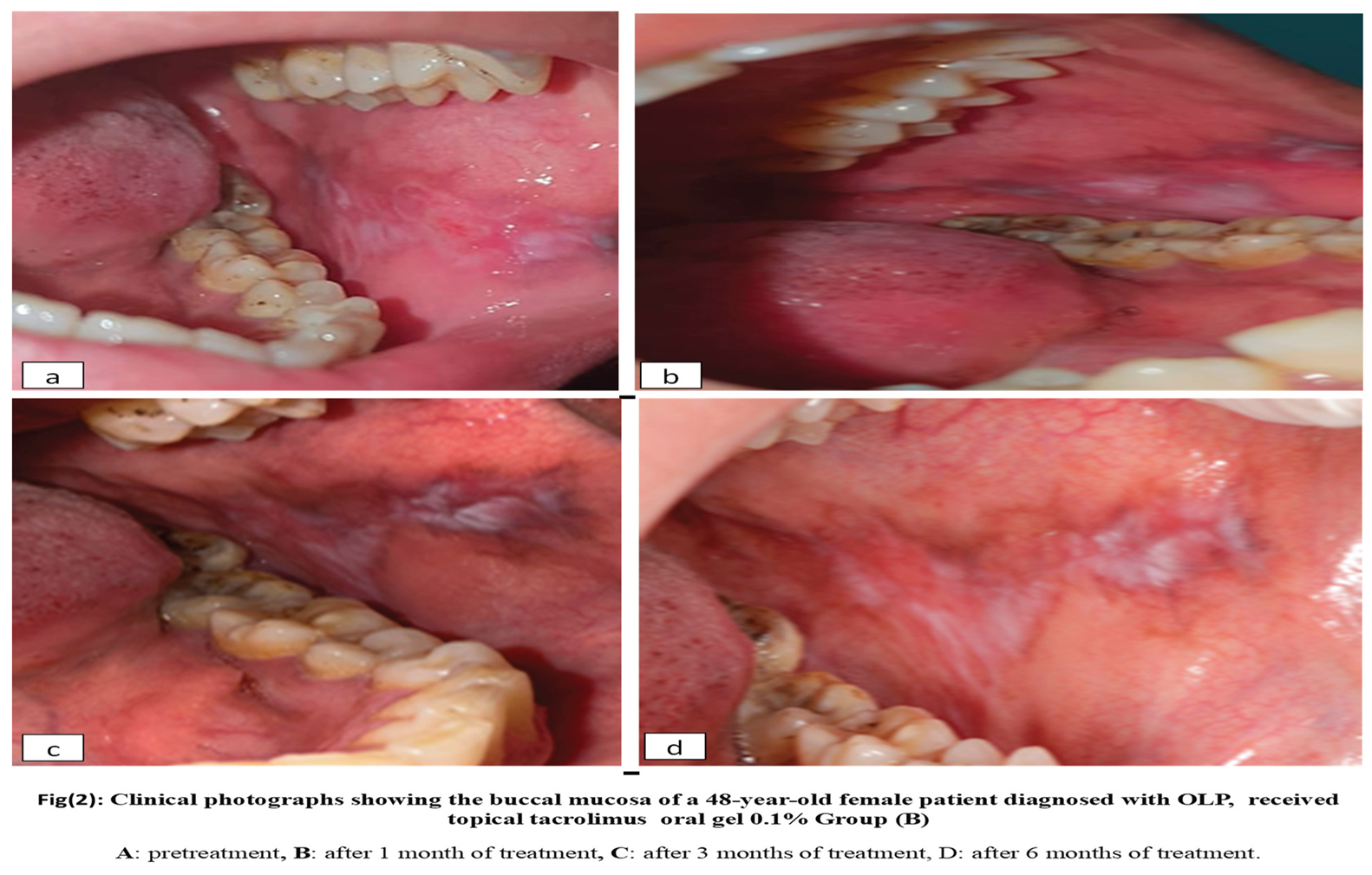

Group B: 10 patients with OLP received topical tacrolimus 0.1% four times per day for six weeks. Figure 2

Group C:10 patients with OLP received topical selenium 1% four times per day for six weeks. Figure 3

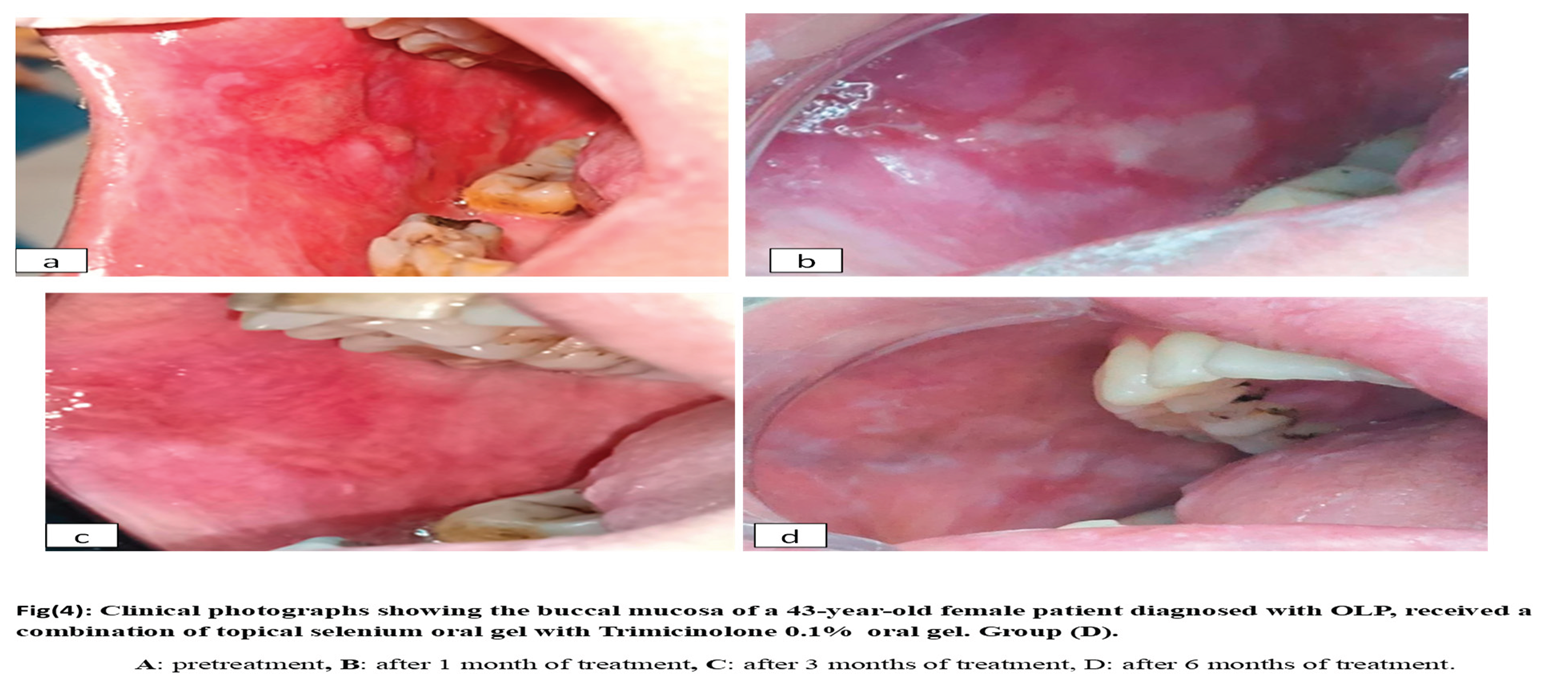

Group D: 10 patients with OLP received topical selenium1% combined with topical triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% four times per day for six weeks. Figure 4

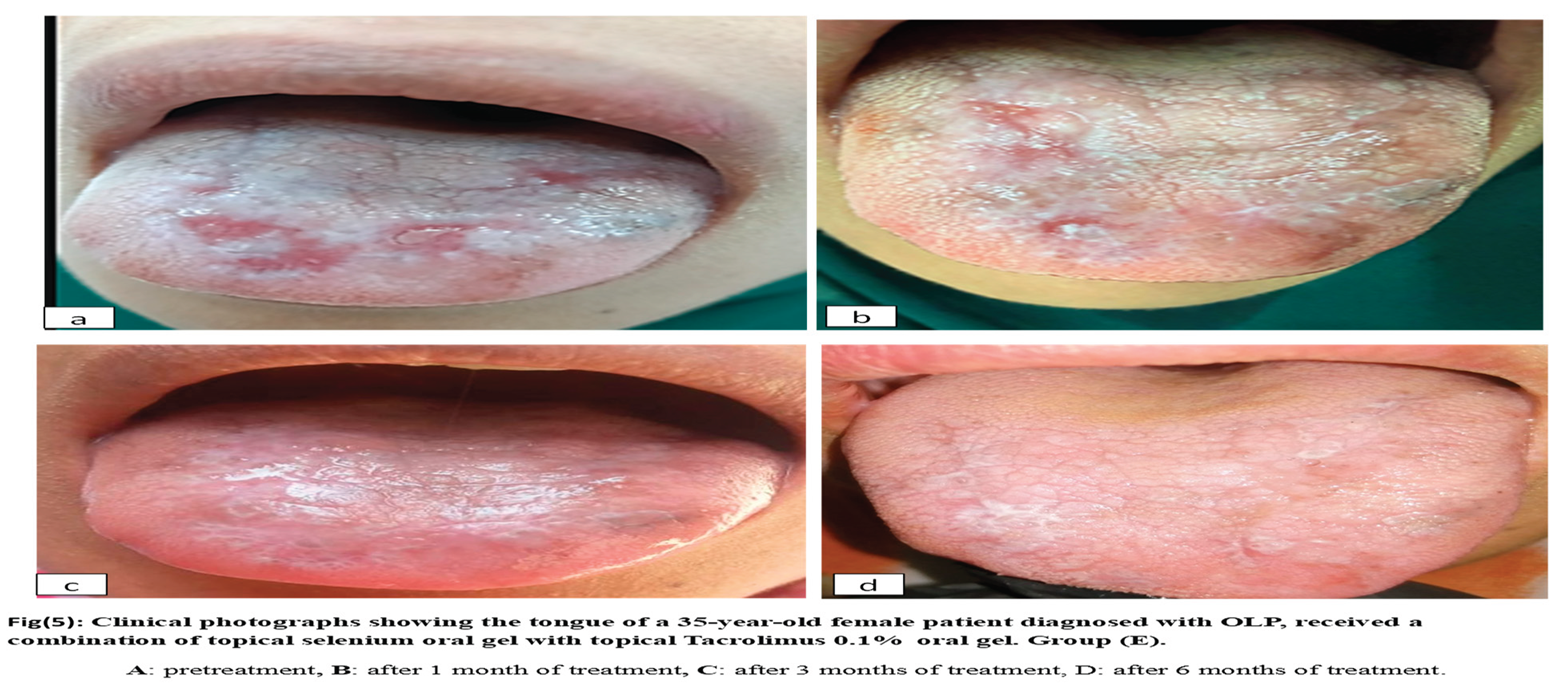

Group E: ten patients with oral lichen planus received topical selenium1% combined with topical tacrolimus 0.1% four times per day for six weeks. Figure 5

Application Method: All patients were advised to apply the gel after brushing and avoid any food or drink intake for at least 20 minutes after gel application. The patient was also asked to apply the gel in one direction only and avoid rubbing the gel back and forth against the oral mucosal lesions.

Adverse Reactions: If an adverse reaction occurred, the patient was told to report it and placed under observation. For serious reactions, treatment was stopped.

2.6. Materials

2.6.1. Therapeutic Agents

• Topical corticosteroids: triamcinolone acetonide (TA) 0.1% oral gel “Kenacort-A-Orabase®.”

•

Tacrolimus oral gel: Twenty capsules of Prograf

® 1 mg, equivalent to 20 mg of Tacrolimus (0.1% w/w), were incorporated into a 2.5% w/w hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) gel base. HPMC gels were made by dispersing the required amount of polymer in a small quantity of distilled water to form an aqueous dispersion. This topical tacrolimus formulation was prepared at the Faculty of Pharmacy, Assiut University [

14]

.

•

Selenium powder: (In the form of sodium selenite pentahydrate (Na2SeO3·5H2O), purchased from Technopharm, India. Selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) 1% were prepared at the Faculty of Pharmacy, Al-Azhar University, Assiut Branch.

Preparation of topical selenium dosage form: Selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) 1% were synthesized by reducing sodium selenite with ascorbic acid and stabilizing them with polysorbate 20. In brief, 30 mg of Na2SeO3·5H2O (1% w/w) was dissolved into 3 % w/w (which equals 90 mL) of Milli-Q water, followed by the dropwise addition of 10 mL ascorbic acid (56.7 mM) under vigorous magnetic stirring for 30 min to complete the reduction process. For every 2 mL of ascorbic acid added, 10 µL of polysorbate was introduced. The formation of SeNPs was confirmed by a color change from clear white to clear red. All solutions were prepared in a sterile environment using a sterile cabinet and double-distilled water. The nanoparticles were collected by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm, and the pellet was resuspended in sterile double-distilled water for bacterial experiments. The chemical reduction of selenium ions to Se nanoparticles (Se-NPs) was evaluated using UV-vis spectroscopy, that considered a simple and indirect method for analyzing the formation of nano-sized particles, identified by the color change of the solution. This eco-friendly approach, known as ”green synthesis,” emphasizes key factors that influence quality and yield, producing stable, uniform, and biocompatible nanoparticles with fewer harmful byproducts than traditional methods. [

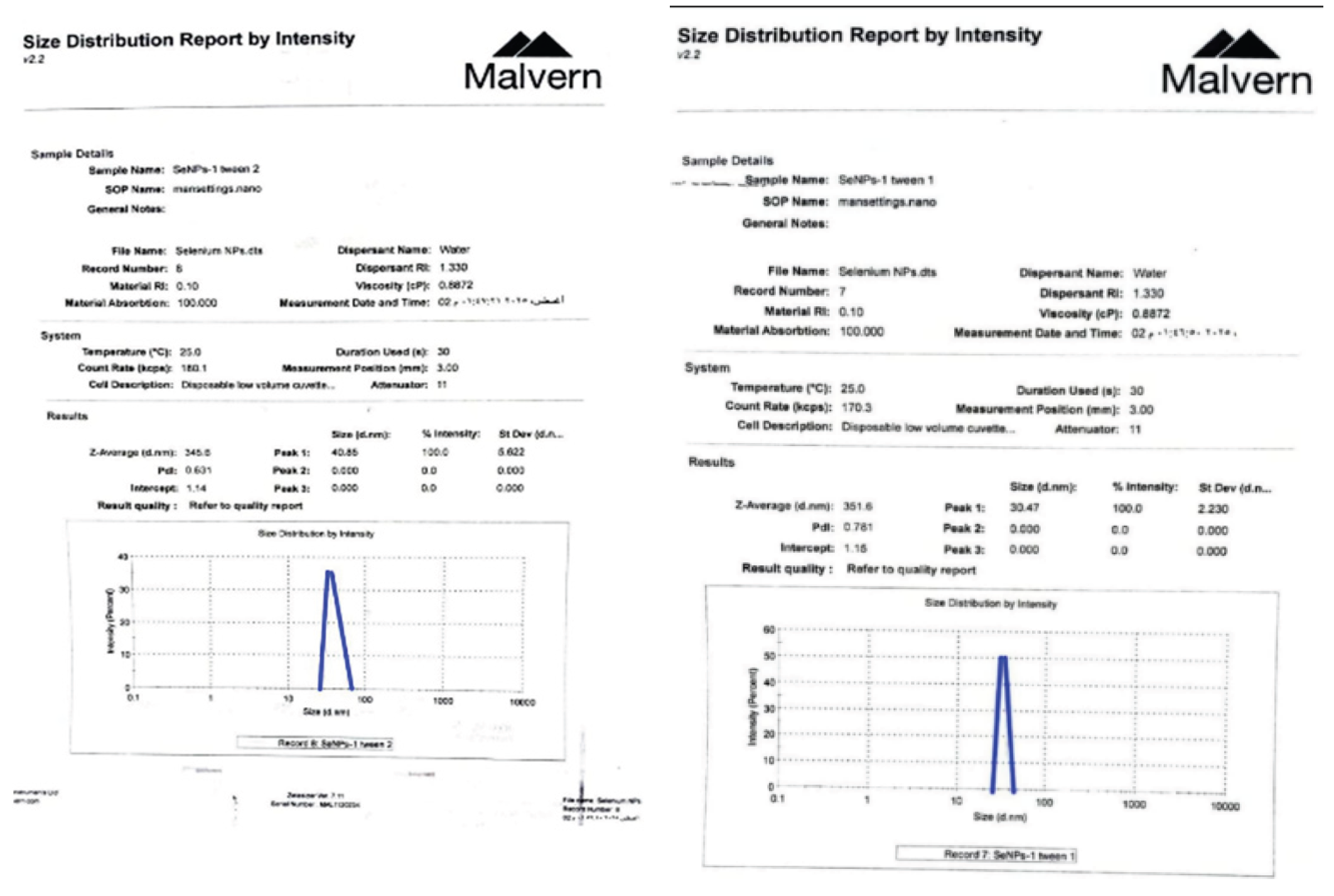

15]

. Characterization of SeNPs: To determine and study the size, pattern, and uniformity of Glu–SeNPs, TEM (transmission electron microscopy), SEM (scanning electron microscopy), and HR-TEM (high-resolution TEM) were performed. EDX (energy dispersive X-ray) was used to analyze the elemental composition of the Glu–SeNPs. FT-IR (Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy) was used to further verify the SeNPs. Strong UV-vis absorption peaks were observed and evaluated using UV-vis spectroscopy, with about 351 nm selected as the scanning range for SeNPs, which is linked to the formation of Se-NPs during the reduction process. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to analyze the physical properties of nanoparticles that had the shape of a sphere, ranging in size from 30.47 d.nm [

16]

Figure 6 and

Figure 7.

2.7.1. Clinical Evaluation

|

Pain: All participants of this clinical trial were assessed for subjective clinical outcome at baseline, after 1,3, and 6 months using a visual analog scale (VAS) [

17]

.

lesion size: For monitoring objective disease severity and activity, a scoring system was used for the measurement of objective outcomes; Photographic records of patients were taken at baseline, after 1,3, and 6 months.

Site score: "Malhotra et al. 2007 [

18]

.

Grade 0: No detectable lesion present. Grade 1: evidence of lichen planus seen ≤50%. (1-3 points of subsites)

Grade 2: >50% of buccal mucosa, dorsum of the tongue, floor of mouth, hard palate, soft palate or oropharynx affected. (4-6 points subsites affected). Grade 3: (7-12 points subsites).

‘

Severity score’ (0–3) (Escudier et al., 2007) [

19]

.

Grade 0: keratosis only ≤ 1 cm2. (Mild asymptomatic). Grade 1: keratosis with mild erythema <3 mm from the gingival margins). Mild/symptomatic. (white stria with atrophic area). Grade 2: Marked Erythema (e.g., full thickness of gingivae, extensive with atrophy or oedema on non-keratinized mucosa). Moderate/symptomatic. (white stria with atrophic area ≥ 1 cm2 marked erythema). Grade 3: Ulceration Present. Severe/symptomatic. (white stria and erosive area).

Activity score = Site score × Severity score

The product of multiplying the site score and the severity score is the ‘activity score.’

2.7.2. Saliva Sampling

In this clinical trial, unstimulated saliva samples were collected from all participants at the Oral Medicine, Periodontology, Diagnosis, and Radiology Department, Faculty of Oral and Dental Medicine, Al-Azhar University (Assiut Branch), Egypt. All patients had completed Phase I therapy, which involved oral hygiene instructions, scaling, and root planing. Scaling was performed the day before to avoid blood contamination. Saliva was collected using the passive drool method without stimulation, both before treatment and during follow-up, between 9 and 11 a.m. Participants were instructed to avoid food, drinks, and tooth brushing for at least two hours before the collection. After rinsing with distilled water, they provided 5 ml of saliva in a clean beaker over five minutes, and any samples containing blood were discarded. The saliva was then placed in clean centrifuge tubes, spun at 3000 g at 4°C for 10 minutes to remove debris and bacteria, and the supernatant was divided into small Eppendorf tubes labeled with patient numbers and color-coded for baseline and post-treatment. All samples were stored at −80°C until analysis. [

20]

.

2.7.3. Biochemical Evaluation

Salivary Glutathione peroxidase enzyme level Analysis: By assessing the levels of salivary Glutathione enzyme by using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay at baseline, 1, and 3 months after treatment. Five mL of whole, unstimulated saliva samples were collected in a sterile container and frozen at -80 c until analysis afterward. Salivary levels of glutathione antioxidant enzyme were measured by ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) Human GPX1(Glutathione peroxidase 1) ELISA Kit (

Catalog No: Re2557H) from Reed Biotech Ltd

®. This ELISA kit applies to the in vitro quantitative determination by pg/mL of human GPX1 concentrations in saliva. [

21]

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All the results were tabulated and statistically analyzed using Microsoft Excel (version 2019; Microsoft, Redmond, Wash) and IBM SPSS Statistics (version 25.0; IBM, Armonk, N.Y.). Descriptive statistics are reported as means and standard deviations. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test for normality, and Levene’s test was used to assess the equality of variance. One-Way ANOVA was used to compare the mean values between the study groups then post hoc tests were used to make pairwise comparisons. Repeated measure ANOVA tests were used to compare means at different intervals within each group then post hoc tests were used to make pairwise comparisons. P value adjusted to be non-significant when P>0.05, significant when P<0.01.

3. Results

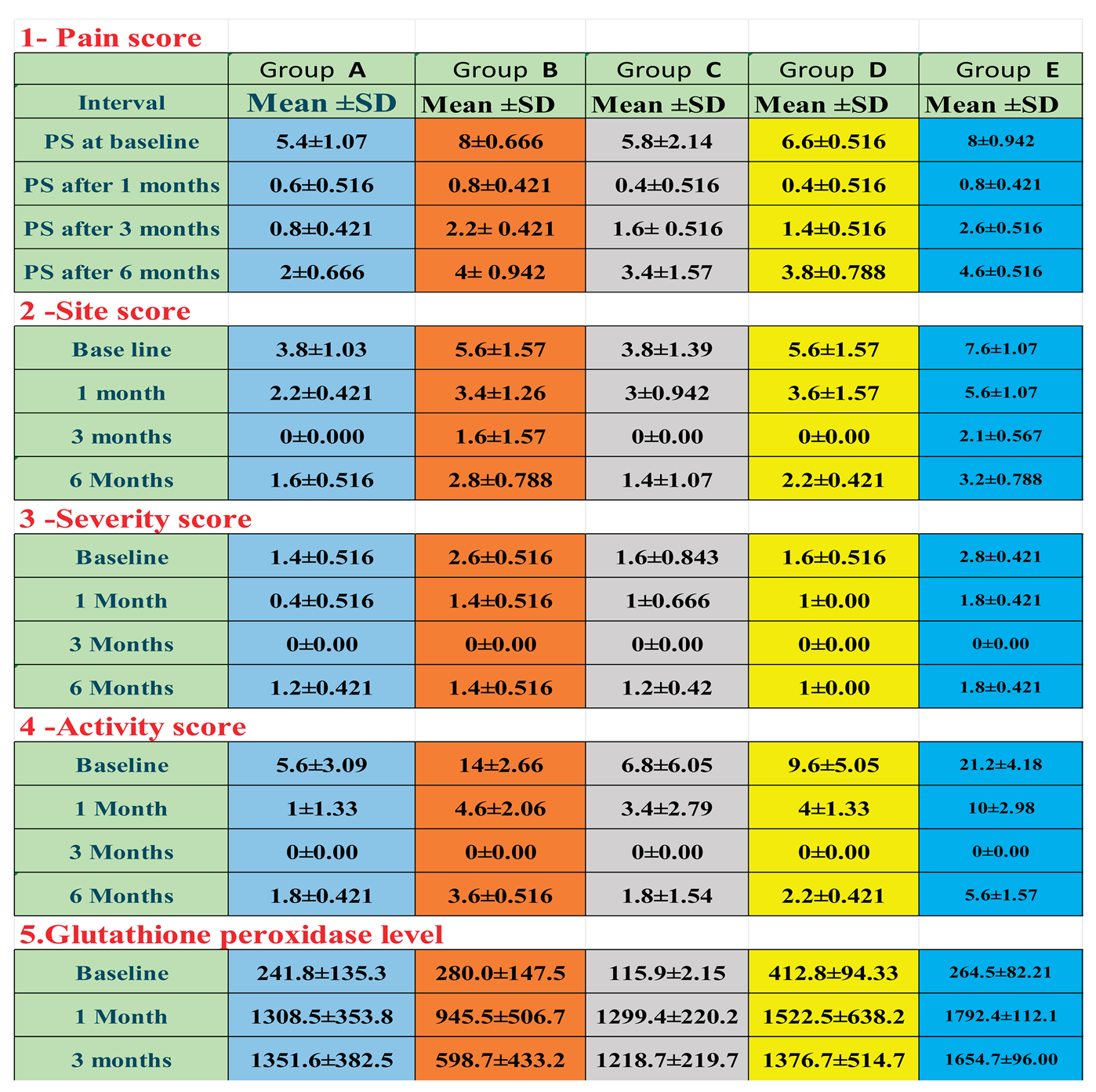

Demographic data: A total of 50 patients (14 men and 36 women) participated in and completed the study according to the prescribed protocol. They ranged in age from 33 to 65 years, with an average age of 46.8 years. The study focused on three main types of lichen planus lesions: non-erosive (keratotic), atrophic, and erosive. Before treatment, common symptoms included burning sensations, pain, and ulcerations from various types of OLP. All patients completed the treatment plan, with outcomes showing full or partial improvement, relapse, or recurrence of lesions within 3–6 months. No significant association was found between baseline characteristics like sex or age and the objective or subjective signs and symptoms before treatment, though differences were noted based on OLP subtypes. Treatment effectiveness was measured using pain scores, clinical evaluations, and biochemical assessments of salivary glutathione peroxidase enzyme levels, summarized in

Table 1 and

Table 2 for baseline and at 1, 3, and 6 months, with biochemical data collected up to 3 months.

Figure 8.

Flow diagram following consort,s guidelines (2010) [22].

Figure 8.

Flow diagram following consort,s guidelines (2010) [22].

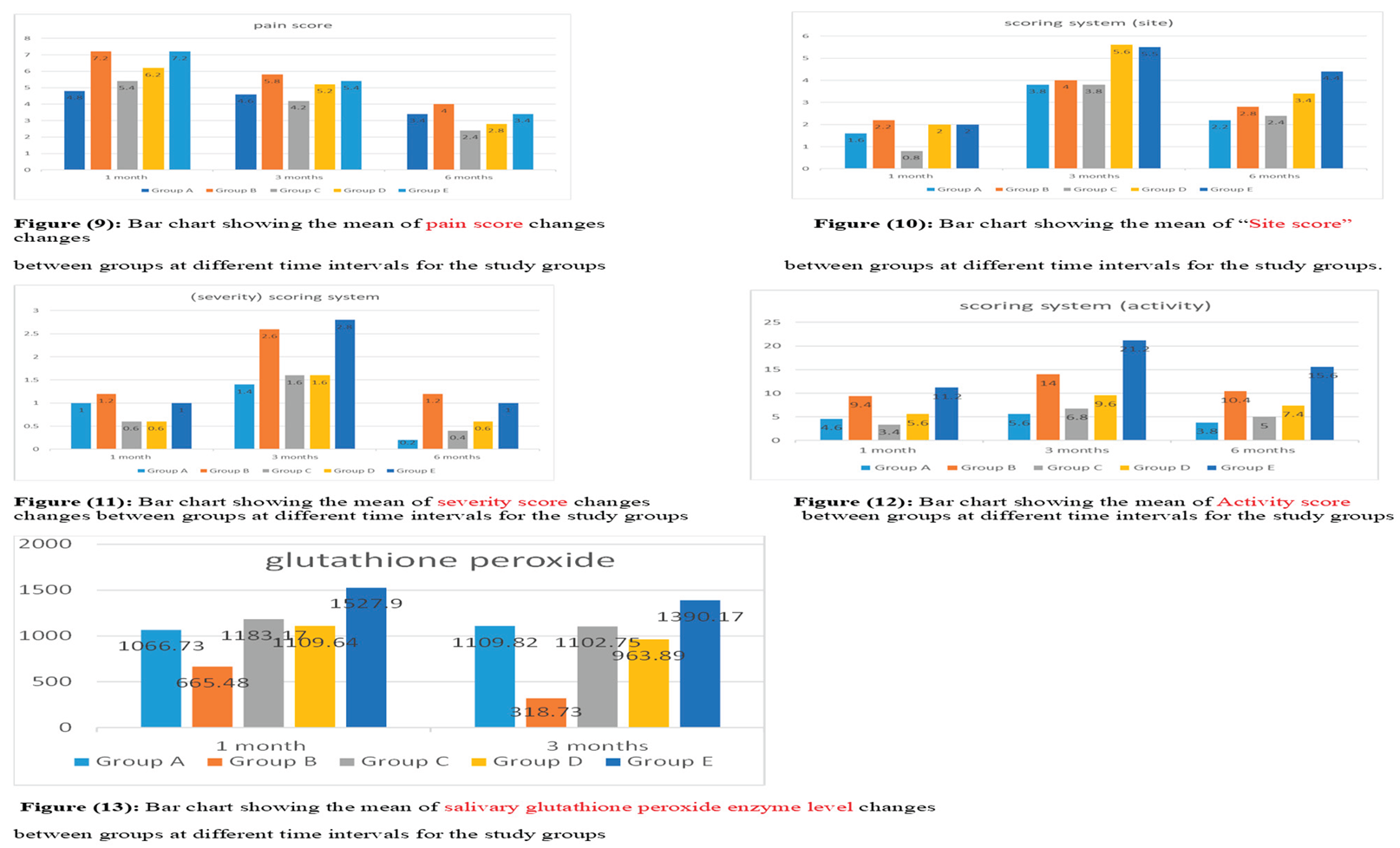

The results of this study showed no significant differences between the study groups at baseline. Using various medications across all groups led to a statistically significant drop in pain scores, as measured by VAS values (P ≤ 0.001) compared to baseline. Differences between all groups were significant at every treatment, favoring the combined groups D and E. There were also significant differences among all groups in clinical scores (site lesion, severity, activity) and glutathione peroxidase enzyme levels. At both 3 and 6 months, highly significant differences were found across all parameters in all groups.

Table 1

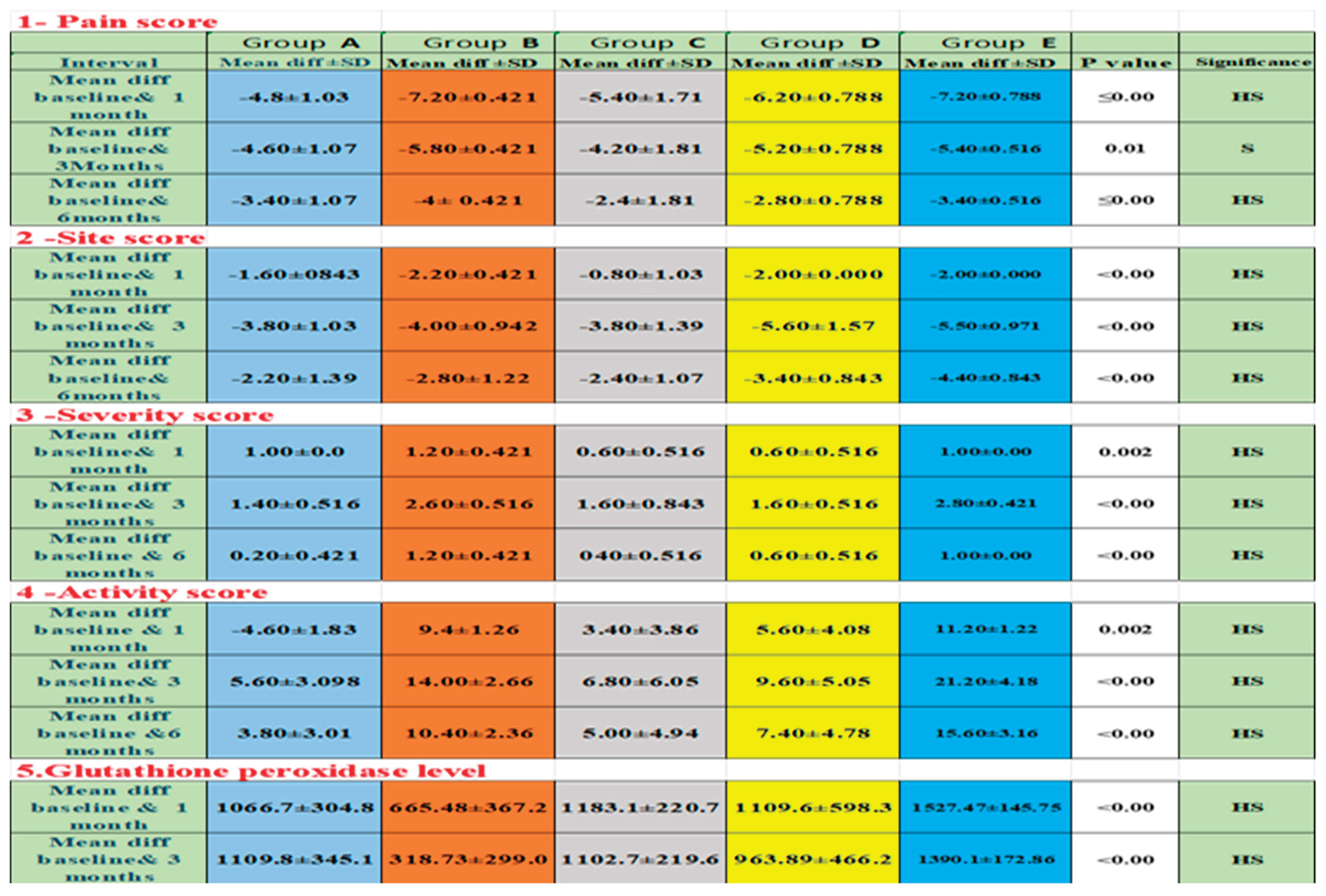

The findings in

Table 2 showed the mean differences between baseline records and 1 month, followed by baseline with 3 months, and finally baseline with 6 months across all studied groups, along with all the recorded parameters. Regarding

pain scores, after

one month, the highest change was in groups

B and

E, at (7.20), followed by group

D at (6.20), group

C at (5.40), and the lowest in group

A at (4.80). After

three months, group

B had the greatest change at 5.80, then group

E at 5.40, group

D at 5.20, group

A at 4.60, and the lowest in group

C at 4.20.

After six months, group

B again showed the greatest change at (4.00), followed by groups

A and

E at (3.40), group

D at (2.80), and the lowest in group

C at (2.40). Figure 9.

For site scores, the biggest change after one month was in group B at (2.20), followed by groups D and E at (2.00, then group A at (1.60), with the smallest change in group C at 0.80. After three months, the greatest change was in group D at (5.60), then group E at (5.50), followed by group B at (4.00), and the lowest in groups A and C at (3.80). After six months, group E led with 4.40, followed by group D at 3.40, group B at 2.80, group C at 2.40, and the lowest change in group A at 2.20. Figure 10.

For the severity score, the biggest change after one month was in group B (1.20), followed by groups A&E (1.00), and the smallest change was in groups C&D (0.60). After three months, the greatest change was in group E (2.80), then group B (2.60), followed by groups C&D (1.60), and the lowest change was in group A (1.40). After six months, the top change was again in group B (1.20), followed by group E (1.00), then group D (0.60), group C (0.40), and the lowest change was in group A. (0.20). Figure 11.

For activity scores, the highest change after one month was in group E (11.20), followed by group B (9.40), group D (5.60), and group A (4.60), with the lowest in group C (3.40). After three months, group E again had the highest change (21.20), then group B (14.00), group D (9.60), and group C (6.80), with the lowest in group A (5.60). After six months, group E led (15.60), followed by group B (10.40), group D (7.40), and group C (5.00), with group A showing the lowest change (3.80). Figure 12

For glutathione peroxidase, the greatest change after one month was in group E (1527.90), followed by group C (1183.17), group D (1109.64), and group A (1066.73), with the lowest in group B (665.48). After three months, group E remained the highest (1390.17), followed by group A (1109.82), group C (1102.75), and group D (963.89), with the lowest again in group B (318.73). Figure 13

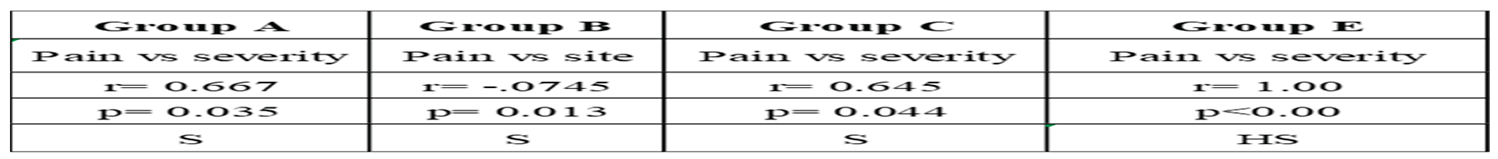

The results in

Table 3, showed the correlation between pain scores, the scoring system, and glutathione peroxide levels, which were analyzed using the Spearman correlation test to evaluate relationships after different treatment approaches across study groups. Results showed: In

group A, a strong positive correlation between pain score and severity score (r = 0.667, p = 0.035) after one month. In

group B, there was a strong negative correlation between pain score and site score (r = -0.745, p = 0.013).

Group C showed a strong positive correlation between pain score and severity score (r = 0.645, p = 0.044). No significant correlations were observed in

group D. In

group E, there was a very strong positive correlation between pain score and severity score (r = 1.00, p < 0.00) after one month (time of drug application)

4. Discussion

The present study was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of selenium as an alternative or complementary topical treatment for oral lichen planus, focusing on its role in reducing pain and achieving clinical resolution in patients with symptomatic OLP, compared to various pharmacological treatment options. In the current study, OLP was observed in 28% of males and 72% of females among 50 patients examined. This differs from findings by

Munde et al. (2013) [

23] and

Gupta et al. (2025) [

24]

, who reported that OLP lesions were roughly twice as common in females as in males. The average participant age in the present study was 46.8 years, while other studies suggest OLP usually begins between ages 30 and 50. Although its exact prevalence is unknown,

Hettiarachchi et al. (2016) [

9] estimated its incidence at around 0.5–2% of the global population. The European Association of Oral Medicine (EAOM) suggests treating OLP only when symptoms appear. OLP lesions were considered a refractory condition, often had a persisting and resistant nature, which makes them difficult for both patients and doctors to handle. Effective treatment is important for easing pain, boosting quality of life, and reducing the risk of cancerous changes. Since the condition is long-lasting and responds well to topical medications, local drug delivery is generally a preferred choice over systemic treatment. [

25]

.

The present study showed that group

A (triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% gel) experienced significant improvements in pain relief, along with a reduction in lesion size and severity. This can be attributed to triamcinolone acetonide’s well-known anti-inflammatory effects, which work through the synthesis of lipocortin-1 to inhibit phospholipase A2, thereby reducing arachidonic acid levels, prostaglandin synthesis, capillary permeability, and inflammatory edema. In addition, corticosteroids help suppress T cell-mediated immune responses by lowering the number and activity of immune cells like T and B lymphocytes, thus leading to decreased surface erythema and decreased pain as it inhibits the synthesis of leukotrienes (mediators of inflammation). These findings are consistent with previous studies by

Gorouhi et al. (2007) [

26],

Arunkumar (2015) [

27],

Shoukheba et al. (2018) [

28],

Serafini et al. (2023) [

29], and

Kotb et al. (2025) [

8]. While triamcinolone acetonide showed clear benefits, some patients did experience side effects, such as relapse after discontinuing treatment.

On the other hand, Tacrolimus 0.1% gel (group

B) in the present study proved effective, providing significant pain relief and completely reducing lesion size and severity. Known as a second-line treatment for symptomatic OLP, tacrolimus works as an immunosuppressant by blocking the calcineurin enzyme, which regulates cell-mediated immunity by preventing interleukin production. These results align with findings from

Resende et al. (2013) [

30]

. Interestingly,

Hettiarachchi et al. (2016) [

9] suggested it could be a first-line option for short-term use, especially for patients more prone to candidiasis, such as those with diabetes. Despite tacrolimus notable benefits in this study, only a few patients experienced adverse effects during the observation period, all of which were minor, including a burning sensation after application, occasional relapse, bad taste, and hyperpigmentation in healed mucosa, consistent with reports from

Gorouhi et al. (2007) [

26]

, Utz et al. (2022) [

31]

, and

Hettiarachchi et al. (2016) [

9].

Compared to the results of previously mentioned study groups (

A, B), using selenium oral gel (group

C) confirmed a safe, well-tolerated, and highly effective new treatment for OLP, offering significant pain relief, faster wound healing, improved symptoms, better quality of life, and longer-lasting results than the standard treatments. These results match those of

Qataya et al. (2019) [

32] and

Belal (2015) [

33]. All these benefits of selenium stem from strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, with the latter helping regulate the immune system and reduce tumor necrosis factor levels. The antioxidant effect targets excess reactive oxygen species (ROS), which cause oxidative stress, cell damage, and slow healing, making ROS reduction a promising approach for chronic lesions. Moreover, selenium also acts as a cofactor for glutathione peroxidase, supporting redox balance. When selenium is converted into nanoparticles, it gains enhanced antimicrobial power—combining these benefits with its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties makes selenium a highly potent treatment. With reference to biochemical results, there was a significant correlation between salivary glutathione peroxidase and antioxidant capacity, consistent with

Qataya et al. (2019) [

32]. In addition,

Shraziy et al. (2022) [

34] reported significantly lower glutathione peroxidase levels in OLP patients, measured using ELISA, a method known for being sensitive, reliable, simple, noninvasive, and widely used, requiring only a small sample for estimation. While Group C OLP patients had no side effects, selenium, compared to topical corticosteroids, provided longer-lasting relief, noticeably reduced pain, and showed no link to candidal infection even with prolonged use.

Zhang et al. (2025) [

35]

, Sadeghian et al (2019).[

36] and

Serramitjana et al (2023) [

37]. noted that saliva can quickly wash away the topical drugs within seconds, making it hard for them to be fully absorbed. To improve bioavailability, the drug needs to stay in contact with the application site longer, allowing it to penetrate deeper into the epithelium. New pharmaceutical approaches like nano-formulations have proven effective at reducing toxicity, limiting side effects, boosting antimicrobial activity, and enhancing tissue absorption, largely due to the mucoadhesive qualities of the nano-gel formula, consistent with findings by

Qatay et al. (2019) [

32]

The observation in group

D (the combination of selenium with 0.1% triamcinolone acetonide) proved effective in managing oral lichen planus, showing statistically significant improvements in both signs and symptoms, along with excellent clinical and biochemical outcomes at all evaluation periods. This can be explained by the synergistic effect of selenium with topical cortisone, as selenium acts as an antioxidant and free radical scavenger, increasing cellular glutathione levels, inhibiting lipid peroxidation, and enhancing membrane stability. These actions promote wound healing, followed by tissue regeneration. In addition, selenium can suppress T lymphocyte function and stimulate inflammatory pathways that have a role in maintaining a healthy immune response. These findings are consistent with

Qatay et al. (2019) [

32], who concluded that this combination improves outcomes and reduces the need for stronger corticosteroids.

Similarly, group

E, which used a combination of selenium gel and 0.1% tacrolimus gel, had a superior clinical response in reducing symptoms and sped up recovery. This was attributed to the synergistic effect of selenium and tacrolimus oral gel, based on the previously mentioned roles of each. These findings are in line with the evidence,

Belal et al. (2015) [

33], who found that combining tacrolimus with selenium can reduce the need for long-term tacrolimus use and address concerns about systemic absorption and potential malignant transformation.

Zhang et al. (2025) [

35] and

Mal et al. (2017) [

38] proved that combination therapy, similar to that used in groups D and E, provided a faster pain relief than single-drug treatments, highlighting selenium’s antioxidant benefits in reducing ROS and supporting speed healing. This approach is often favored over monotherapy for its strong effectiveness, cost-efficiency, and lower risk of drug resistance.

The study’s key findings show that selenium nanoparticle oral gel is a highly effective alternative or complementary topical treatment for Oral Lichen Planus, offering early pain relief and improving all clinical signs and symptoms in OLP patients. Its strong effects are linked to anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial properties, consistent with the findings of

Qatay et al. (2019) [

32] and

Serramitjana et al. (2023) [

37] The results also highlight the importance of a logical approach when selecting OLP medication, tailoring treatment to each patient’s specific needs—whether it’s a first-time case, a resistant one, or part of a short- or long-term plan—aligning with

da Silva’s meta-analysis (2021) [

39]