Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

25 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

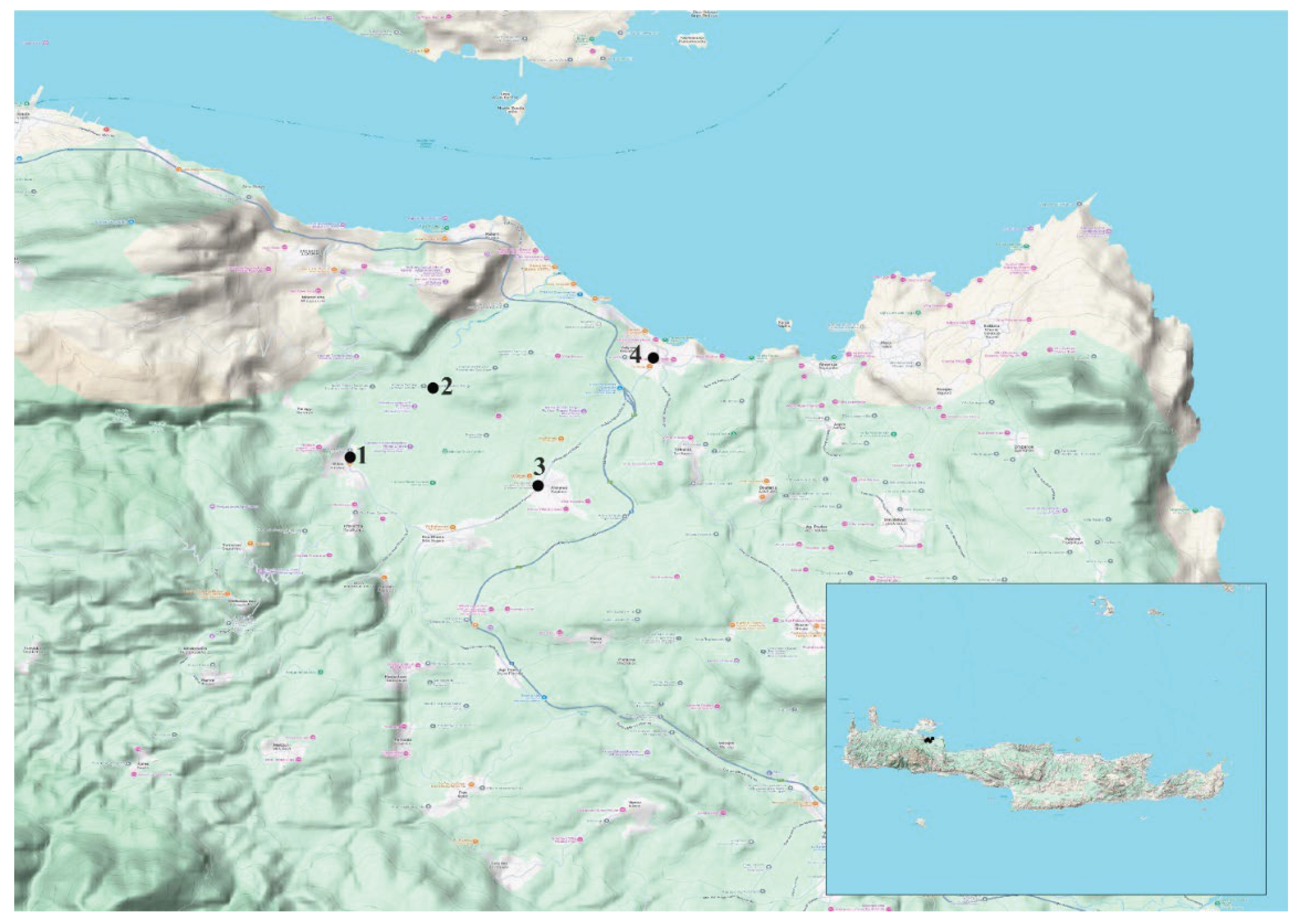

2.1. Study area and river sites

2.2. Field Survey and Additional Data Acquisition

2.3. Analysis of Total Nitrogen

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Water Characteristics

3.2. Biota Indicators

3.3. Comparison Between Matrices

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CLD | Chemiluminescence detector |

| CZO | Critical Zone Observatory |

| DO | Dissolved oxygen |

| EC | Electrical conductivity |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| EPT | Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera, Trichoptera |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| TN | Total nitrogen |

References

- Smucker, N.J.; Kuhn, A.; Cruz-Quinones, C.J.; Serbst, J.R.; Lake, J.L. Stable isotopes of algae and macroinvertebrates in streams respond to watershed urbanization, inform management goals, and indicate food web relationships. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 90, 295–304. [CrossRef]

- Frossard, V.; Aleya, L.; Vallet, A.; Henry, P.; Charlier, J.-B. Impacts of nitrogen loads on the water and biota in a karst river (Loue River, France). Hydrobiologia 2020, 847, 2433–2448. [CrossRef]

- Lilli, M.A.; Efstathiou, D.; Moraetis, D.; Schuite, J.; Nerantzaki, S.D.; Nikolaidis, N.P. A multi-disciplinary approach to understand hydrologic and geochemical processes at Koiliaris Critical Zone Observatory. Water 2020, 12, 2474. [CrossRef]

- Carballeira, C.; Carballeira, A.; Aboal, J.R.; Fernández, J.A. Biomonitoring freshwater fish farms by measuring nitrogen concentrations and the δ¹⁵N signal in living and devitalized moss transplants. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 245, 1014–1021. [CrossRef]

- Nerantzaki, S.D.; Nikolaidis, N.P. The response of three Mediterranean karst springs to drought and the impact of climate change. J. Hydrol. 2020, 591, 125296. [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.O.; Bell, N.; Bruggeman-Nannenga, M.A.; Brugués, M.; Cano, M.J.; Enroth, J.; Flatberg, K.I.; Frahm, J.-P.; Gallego, M.T.; Garilleti, R.; et al. An annotated checklist of the mosses of Europe and Macaronesia. J. Bryol. 2006, 28, 198–267.

- Bowden, W.B.; Glime, J.M.; Riis, T. Macrophytes and bryophytes. In Methods in Stream Ecology, 3rd ed.; Hauer, F.R.; Lamberti, G.A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 243–271.

- AQEM Consortium. Manual for the Application of the AQEM System: A Comprehensive Method to Assess European Streams Using Benthic Macroinvertebrates, Developed for the Purpose of the Water Framework Directive; Version 1.0; February 2002.

- Cheshmedjiev, S.; Soufi, R.; Vidinova, Y.; Tyufekchieva, V.; Yaneva, I.; Uzunov, Y.; Varadinova, E. Multi-habitat sampling method for benthic macroinvertebrate communities in different river types in Bulgaria. Water Res. Manag. 2011, 1, 55–58.

- 10. ISO 5667-3:2024. Water Quality—Sampling—Part 3: Preservation and Handling of Water Samples; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- StatSoft Inc. STATISTICA (Data Analysis Software System), Version 12; StatSoft Inc.: Tulsa, OK, USA, 2013.

- Xia, M.; Xue, N.; Hu, B.; Gong, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X. The sources and influencing factors of dissolved organic carbon under high-sediment environments—A case from Wuding River Basin. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1631894. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Tian, F.; Huang, Y.; Tao, H.; Li, F. Sediment legacy of aquaculture drives endogenous nitrogen pollution and water quality decline in the Taipu River–Lake system. Water 2025, 17, 2000. [CrossRef]

- Euro+Med PlantBase. Euro+Med PlantBase—The Information Resource for Euro-Mediterranean Plant Diversity. Available online: http://www.europlusmed.org (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Papp, B. Investigation of the bryoflora of some streams in Greece. Stud. Bot. Hung. 1999, 29, 59–67.

- Blockeel, T.L. The bryophytes of Greece: New records and observations. J. Bryol. 1991, 16, 629–640. [CrossRef]

- Khadija, S.; Francis, R.; Bernard, T. Trend analysis in ecological status and macrophytic characterization of watercourses: Case of the Semois-Chiers Basin, Belgium Wallonia. J. Water Resour. Prot. 2015, 7, 988–1000. [CrossRef]

- Rimac, A.; Alegro, A.; Šegota, V.; Vuković, N.; Koletić, N. Ecological preferences and indication potential of freshwater bryophytes—Insights from Croatian watercourses. Plants 2022, 11, 3451. [CrossRef]

- Koranda, M.; Kerschbaum, S.; Wanek, W.; Zechmeister, H.A.; Richter, A. Physiological responses of bryophytes Thuidium tamariscinum and Hylocomium splendens to increased nitrogen deposition. Ann. Bot. 2007, 99, 161–169. [CrossRef]

- Simmel, J.; Ahrens, M.; Poschlod, P. Ellenberg N values of bryophytes in Central Europe. J. Veg. Sci. 2021, 32, e12957. [CrossRef]

- Yurukova, L.; Gecheva, G. Biomonitoring in Maritsa River using aquatic bryophytes. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2004, 5, 729–735.

- Evtimova, V.; Tyufekchieva, V.; Varadinova, E.; Vidinova, Y.; Ihtimanska, M.; Georgieva, G.; Todorov, M.; Soufi, R. Macroinvertebrate communities of sub-Mediterranean intermittent rivers in Bulgaria: Association with environmental parameters and ecological status. Ecol. Balkanica 2021, Special Issue 4, 49–64.

- Georgopoulou, E. An annotated checklist of the freshwater molluscs (Gastropoda, Bivalvia) of Crete, Greece. Folia Malacol. 2025, 33, 47–63. [CrossRef]

- Zwick, P. Plecoptera (Stoneflies). In The Aquatic Insects of North Europe: A Taxonomic Handbook; Nilsson, A.N., Ed.; Apollo Books: Stenstrup, Denmark, 1992; Volume 1, pp. 163–200.

- Graf, W.; Murphy, J.; Dahl, J.; Zamora-Muñoz, C.; López-Rodríguez, M.J. Distribution and Ecological Preferences of European Freshwater Organisms. Volume 1: Trichoptera; Pensoft Publishers: Sofia–Moscow, 2008; 388 pp.

- Malicky, H. Ein kommentiertes Verzeichnis der Köcherfliegen (Trichoptera) Griechenlands. Linzer Biol. Beitr. 2005, 37, 533–596.

- Anderson, W.B.; Polis, G.A. Marine subsidies of island communities in the Gulf of California: Evidence from stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes. Oikos 1998, 81, 75–80.

- Beck, M.; Billoir, E.; Felten, V.; Meyer, A.; Usseglio-Polatera, P.; Danger, M. A database of West European headwater macroinvertebrate stoichiometric traits. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2022, 31, 4–9. [CrossRef]

- Beck, B.; Billoir, E.; Usseglio-Polatera, P.; Meyer, A.; Gautreau, E.; Danger, M. Effects of water nutrient concentrations on stream macroinvertebrate community stoichiometry: A large-scale study. Peer Community J. 2024, 4, e69.

- Bonada, N.; Rieradevall, M.; Prat, N. Macroinvertebrate community structure and biological traits related to flow permanence in a Mediterranean river network. Hydrobiologia 2007, 589, 91–106.

- Varadinova, E.; Gecheva, G.; Tyufekchieva, V.; Milkova, T. Macrophyte- and macrozoobenthic-based assessment in rivers: Specificity of the response to combined physico-chemical stressors. Water 2023, 15, 2282.

- García-Álvaro, M.A.; Martínez-Abaigar, J.; Núñez-Olivera, E.; Beaucourt, N. Element concentrations and enrichment ratios in the aquatic moss Rhynchostegium riparioides along the River Iregua (La Rioja, Northern Spain). Bryologist 2000, 103, 518–533.

- Basu, N.B.; Van Meter, K.J.; Byrnes, D.K.; et al. Managing nitrogen legacies to accelerate water quality improvement. Nat. Geosci. 2022, 15, 97–105. [CrossRef]

| Spring/Stream | Coordinates | T, oC | pH | EC, μS/cm | DO, mg/L | ||

| N | E | ||||||

| 1 | Stylos | 35.43423042 | 24.12621967 | 13.7 | 7.91 | 237 | 11.05 |

| 2 | Agios Georgios | 35.4450669 | 24.1391838 | 17.4 | 8.08 | 248 | 9.03 |

| 3 | Armenoi | 35.42976973 | 24.15562563 | 15.0 | 8.18 | 236 | 9.34 |

| 4 | Zourpos | 35.44977297 | 24.17366747 | 15.4 | 7.82 | 1526 | 9.32 |

| Spring/Stream | water, mg/L | sediment g/kg | moss g/kg | macroinvertebrates, g/kg | |

| 1 | Stylos | 1.1 | 0.3 | 20.4 | 44.5 |

| 2 | Agios Georgios | 0.9 | 1.1 | 17.5 | 29.8 |

| 3 | Armenoi | 0.9 | 0.3 | 16.9 | 30.5 |

| 4 | Zourpos | 1.4 | 0.2 | 20.0 | 47.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).