Submitted:

23 December 2025

Posted:

24 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Why the Africa Context Matters?

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

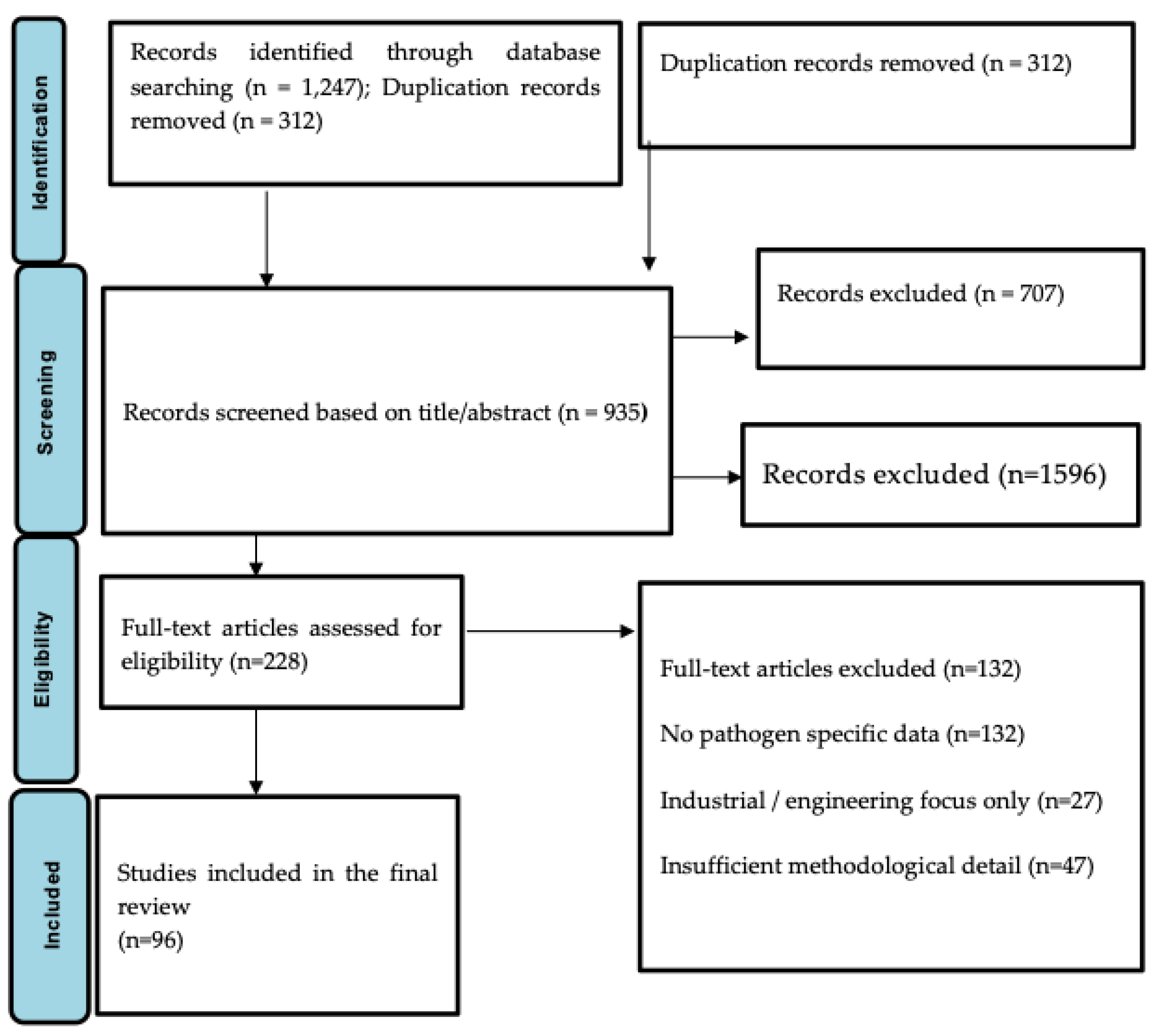

2.4. Screening Process

2.5. Technical Workflow Overview

2.6. Sampling Workflow

2.7. Concentration and Extraction Workflow

2.8. Biological and Molecular Detection Workflow

3. Results

3.1. Prisma Layout Flow Summary

3.2. Detection of Gastrointestinal Pathogens in Wastewater

3.3. Detection of Respiratory Pathogens in Wastewater

3.4. Correlations Between Wastewater Signals and Clinical Case Data

3.5. Technical and Operational Considerations

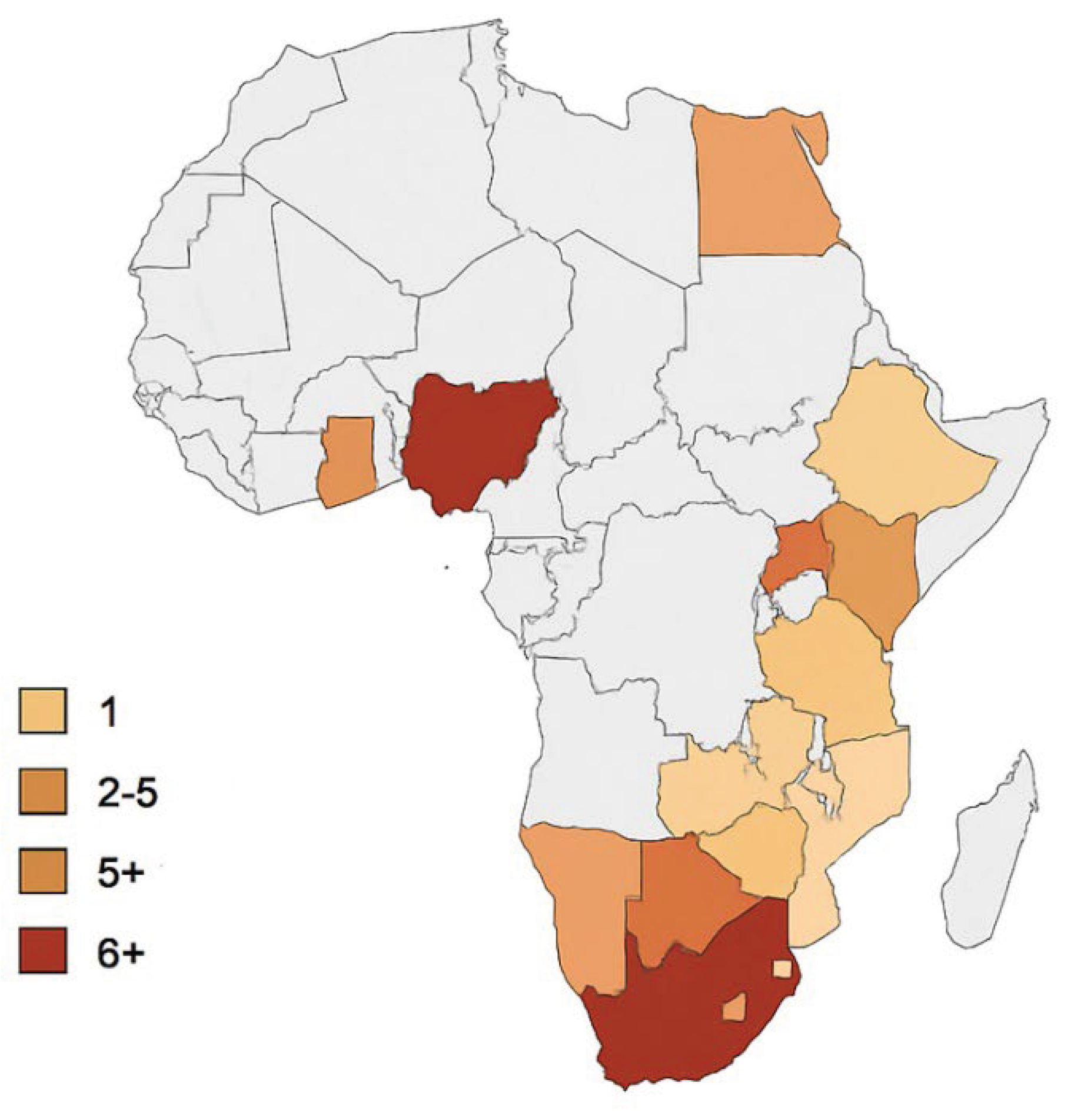

3.6. Regional WBE Evidence in Africa Compared with Findings from Rwanda

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of Wastewater-Based Epidemiology (WBE) for GI and Respiratory Pathogens

4.2. Detection of Gastrointestinal Pathogens in Wastewater

4.3. Detection of Respiratory Pathogens in Wastewater

4.4. Correlation Between Wastewater Signals and Clinical Data

4.5. Strengths and Limitations of WBE in Public Health Surveillance

4.6. Implications for Early Warning Systems

4.7. Opportunities for Implementation in Low-Resource African Settings

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| AMR | Antimicrobial Resistance |

| AMS | Antimicrobial Stewardship |

| API20E | Analytical Profile Index 20 Enterobacterales |

| ARGs | Antimicrobial Resistance Genes |

| AST | Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal Fluid |

| CCN | Clinical Case Notification |

| |COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| ddPCR | Droplet Digital Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| ESBL | Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| GLASS | Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System |

| HAI | Hospital-Acquired Infection |

| HAV | Hepatitis A Virus |

| HEV | Hepatitis E Virus |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| IPC | Infection Prevention and Control |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| LMICs | Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| MDRO | Multidrug-Resistant Organism |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| Mesh | Medical Subject Headings |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| MDRO | Multidrug-Resistant Organism |

| MS2 | MS2 Bacteriophage |

| PMMoV | Pepper Mild Mottle Virus |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| qPCR | Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| RSV | Respiratory Syncytial Virus |

| RT-PCR | Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| RT-qPCR | Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| SSIs | Surgical Site Infections |

| UN DESA | United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WBE | Wastewater-Based Epidemiology |

| WPV | Wild Poliovirus |

References

- Medema, G.; Been, F.; Heijnen, L.; Petterson, S. Implementation of environmental surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 virus to support public health decisions: Opportunities and challenges. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2021, 17, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivins, A.; North, D.; Ahmad, A.; Ahmed, W.; Alm, E.; Been, F.; et al. Wastewater-based epidemiology: Global collaborative to maximize contributions in the fight against COVID-19. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54(13), 7754–7757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daughton, C.G. Wastewater surveillance for population-wide COVID-19: The present and future. SCI. Total Environ. 2020, 736, 139631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troeger, C.; Blacker, B.F.; Khalil, I.A.; et al. Global morbidity and mortality of diarrhea, 195 countries (GBD 2016). Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18(11), 1211–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. GLASS Report 2021; WHO: Geneva, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer Walker, C.L.; Perin, J.; Aryee, M.J.; et al. Diarrhea incidence in LMICs, 1990–2010. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer Walker, C.L.; Rudan, I.; Liu, L.; et al. Global burden of childhood pneumonia & diarrhea. Lancet 2013, 381(9875), 1405–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, C.A.; Luo, T.X.; Zhou, S.S.; et al. Barriers to surveillance in LMICs. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e004216. [Google Scholar]

- Amuquandoh, A.; Effah, E.; Ohene, S.A.; et al. Surveillance challenges in low-income settings. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 36, 133. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay, S.; et al. Limitations of clinical case reporting in resource-poor settings. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2019, 24(10), 1204–1214. [Google Scholar]

- Kupferschmidt, K.; Cohen, J. China’s COVID-19 strategy evaluation. Science 2020, 367(6482), 1061–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, A.; et al. High SARS-CoV-2 titers in wastewater. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peccia, J.; Zulli, A.; Brackney, D.E.; et al. Wastewater RNA tracks community infection dynamics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 1164–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitajima, M.; Ahmed, W.; Bibby, K.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater: Knowledge gaps. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 739, 139076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norström, A.; et al. Wastewater-based pathogen surveillance: Global evidence. Environ. Int. 2022, 158, 106944. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, W.; Angel, N.; Edson, J.; et al. First confirmed SARS-CoV-2 detection in Australian wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusiñol, M.; Martínez-Puchol, S.; Timoneda, N.; et al. Enteric virus monitoring in wastewater. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2020, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hellmér, M.; Paxéus, N.; Magnius, L.; et al. Early warning of HAV & norovirus from sewage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80(21), 6771–6781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, G.; Bonadonna, L.; Lucentini, L.; et al. Emerging viral pathogens in wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 734, 139435. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Breitbart, M.; Lee, W.H.; et al. Systematic review of enteric viruses in wastewater. Water Res. 2021, 203, 117534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, S.; Levy, J.I.; De Hoff, P.; et al. Early detection of Omicron via wastewater sequencing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibby, K.; Bivins, A.; Wu, Z.; North, D. Wastewater surveillance of respiratory viruses. Science 2021, 371(6526), 1159–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt, W.Q.; Schmitz, B.W.; Innes, G.K.; et al. COVID-19 wastewater surveillance for public health action. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27(9), 2671–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, J.E.; Dickey, B.W.; Miller, R.D.; et al. Epidemiology of norovirus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 55 Suppl. 4, S120–S126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haramoto, E.; Kitajima, M.; Hata, A.; et al. Virus removal and fate in wastewater treatment. Water Res. 2018, 133, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Wastewater-Based Disease Surveillance for Public Health Action. Washington DC: NASEM, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gahamanyi, N.; et al. Surveillance challenges in Africa. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2022, 41, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Rwanda Biomedical Centre (RBC). Annual Epidemiological Bulletin; Ministry of Health: Kigali, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mutesa, L.; Ndishimye, P.; Butera, Y.; et al. Pooled testing strategy for SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2021, 589, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, S.; Orschler, L.; Lackner, S. Long-term wastewater SARS-CoV-2 monitoring. Water Res. 2021, 201, 117365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, J.S.; Scire, J.; Caduff, L.; et al. Wastewater surveillance for reproduction number & variants. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naughton, C.C.; Roman, F.A.; Alvarado, A.G.F.; et al. Global wastewater surveillance needs transparency. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55(22), 14763–14772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2023; WHO: Geneva, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ihekweazu, C.; Agogo, E. Africa’s response to COVID-19. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Urbanization Prospects 2022; UN DESA: New York, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Edson, R.; Rutayisire, R.; El-Khatib, Z.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 detection via wastewater at Kigali International Airport. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2025, 11, e71104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzinamarira, T.; Gashema, P.; Iradukunda, P.G.; et al. Utilization of SARS-CoV-2 wastewater surveillance in Africa: A rapid review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.; Gwee, S.X.W.; Ng, J.Q.X.; et al. Wastewater surveillance to infer COVID-19 transmission: A systematic review. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 804, 150060. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Cassi, X.; Scheidegger, A.; Bänziger, C.; et al. Wastewater monitoring outperforms case numbers when positivity rates are high. Water Res. 2021, 200, 117252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Roguet, A.; McClary-Gutierrez, J.S.; et al. Evaluation of sampling, analysis, and normalization methods for SARS-CoV-2 wastewater concentrations. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 787, 147449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, R.; Mathee, A.; Reddy, T.; et al. One year of wastewater surveillance in South Africa supporting COVID-19 clinical findings. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwu, E.E.; Lawal, R.A.; Igboanusi, C.J.; et al. Surveillance of public health pathogens using wastewater in Lagos, Nigeria.

- BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 21157. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza Grijalva, L.; Seck, A.; Roldan-Hernandez, L.; et al. Persistence of respiratory, enteric, and fecal indicator viruses in fecal sludge in Dakar, Senegal. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 2024, 14(10), 916–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zyl, WB; et al. Detection of pathogen bacteria in bacteria in wastewater in South Africa. Water SA 2017, 43(2), 239–248. [Google Scholar]

- Edson et al. — Correct Rwanda WBE reference (replacing incorrect Habiyaremye et al.). Edson, R.; Rutayisire, R.; El-Khatib, Z.; Nsekuye, O.; Mucunguzi, H.V.; Muvunyi, R.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 detection in international travelers through wastewater-based epidemiology at the Kigali International Airport: Genomic surveillance study. JMIR Public Health Surveil. 2025, 11, e71104. [CrossRef]

- Pecson; Pecson, B.M.; Darby, E.; Haas, C.N.; Amha, Y.M.; Bartolo, M.; Danielson, R.; et al. Reproducibility and sensitivity of 36 methods to quantify the SARS-CoV-2 genetic signal in raw wastewater: Findings from an interlaboratory evaluation. Environ. Sci.: Water Res. Technol. 2021, 7, 504–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmahdy, EM; Shaheen, MNF; Chawla-Sarkar, M; et al. Vertical distribution of enteric viruses in different layers of wastewater treatment plants in Egypt. Food Environ Virol. 2019, 11, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Polio Environmental Surveillance Expansion Guidelines: Surveillance of Polioviruses in Sewage and Wastewater; WHO: Geneva, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations – World Urbanization Prospects 2022.

- Johnson, R; et al. Wastewater SARS-CoV-2 trends correlate with clinical cases in South Africa. SCI Total Environ. 2021, 786, 147273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, R; et al. National wastewater surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 in South Africa. Water Res. 2022, 219, 118603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, R; et al. One year of wastewater surveillance in South Africa. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlangu, P; et al. Environmental surveillance for polioviruses in South Africa. J Med Virol. 2019, 91, 144–152. [Google Scholar]

- Gumede, N; et al. Detection of polio in wastewater networks in SA. Commun Dis Surveill Bull 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nkado, RM; et al. Wastewater as reservoir of AMR genes in South Africa. Sci Total Environ. 2020, 703, 135649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniji, JA; et al. Poliovirus detection in wastewater, Nigeria. Virus Res. 2017, 232, 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Baba, M; et al. Environmental surveillance for poliovirus. J Med Virol. 2018, 90, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Awolusi, OO; et al. SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater in Nigeria. J Water Health 2023, 21(1), 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmahdy, EM; et al. HAV & HEV detection in wastewater. Food Environ Virol. 2019, 11, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Said, A; et al. Hepatitis viruses in Egyptian sewage. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2020, 27, 978–987. [Google Scholar]

- Shawky, S; et al. SARS-CoV-2 wastewater detection in Egypt. Sci Total Environ. 2021, 800, 149620. [Google Scholar]

- Barhoumi, M; et al. SARS-CoV-2 wastewater detection in Tunisia. Sci Total Environ. 2021, 760, 144044. [Google Scholar]

- Wurtzer, S; et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load patterns in wastewater. Sci Total Environ. 2021, 757, 143738. [Google Scholar]

- Nasseri, S; et al. Wastewater surveillance for COVID-19 in Morocco. Sci Total Environ. 2021, 748, 141282. [Google Scholar]

- Kiiru, JN; et al. AMR bacteria in Kenyan wastewater. BMC Microbiol. 2018, 18, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Omwandho, CO; et al. Salmonella in Kenyan wastewater. East Afr Med J 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Oyaro, N; et al. SARS-CoV-2 wastewater detection. J Environ Health Sci Eng. 2021, 19, 865–872. [Google Scholar]

- Katongole, P; et al. AMR bacteria in wastewater. BMC Infect Dis. 2020, 20, 820. [Google Scholar]

- Armah, GE; et al. Norovirus & rotavirus detection in wastewater. J Med Virol. 2016, 88, 1692–1701. [Google Scholar]

- Aboagye, G; et al. Enteric viruses in wastewater. J Appl Microbiol. 2018, 125, 1130–1139. [Google Scholar]

- Diop, OM; et al. Poliovirus surveillance in Senegal. J Infect Dis. 2014, 210, S655–S665. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza Grijalva, L; et al. Viral persistence in fecal sludge. J Water Sanit Hyg Dev. 2024, 14(10), 916–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manangazira, P; et al. SARS-CoV-2 wastewater signal detection in Zimbabwe. Pan Afr Med J 2021, 39, 111. [Google Scholar]

- Uwimana, A; et al. SARS-CoV-2 wastewater surveillance in Kigali. Rwanda Public Health Bulletin 2022. [Google Scholar]

- RBC Wastewater Monitoring Report, 2021.

- Ndayishimiye E, et al. Framework for wastewater surveillance in Rwanda. Rwanda J Med Health Sci. 2023.

- Misbah G, et al. Aircraft wastewater genomic surveillance in Rwanda. In press, 2025.

- Alemayehu, T; et al. AMR genes in Ethiopian wastewater. Antibiotics 2020, 9(7), 386. [Google Scholar]

- Wade, M.J.; Lo Jacomo, A.; Armenise, E.; Brown, M.R.; Bunce, J.T.; Cameron, G.; et al. Understanding and managing uncertainty and variability for wastewater monitoring beyond the pandemic: Lessons from the UK national surveillance programme. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424(B), 127456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodder, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; de Roda Husman Lodder, W; de Roda Husman, AM. SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater: Potential health risk, but also data source. Euro Surveill. 2020, 25(12), 2000302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriksen; CorrecHendriksen, RS; Munk, P; Njage, P; van Bunnik, B; McNally, L; Lukjancenko, O; et al. Global monitoring of antimicrobial resistance based on metagenomics analyses of urban sewage. Nat Commun. 2019, 10, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazama; Kazama, S; Miura, T; Masago, Y; et al. Environmental surveillance of norovirus genogroups I and II in Japan, 2012–2013. Food Environ Virol. 2017, 9, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awolusi; Awolusi, OO; Omeje, VO; Otunla, A; et al. Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater in Nigeria: Implications for viral surveillance. J Water Health 2023, 21(1), 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- DOI: 10.2166/wh.2022.128.

- Africa CDC – Correct official citation. Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Pathogen Genomics Initiative Annual Reports, 2021–2024. Addis Ababa: Africa CDC; 2021–2024.

- Wolfe; Wolfe, MK; Topol, A; Knudson, A; Simpson, A; White, B; Vugia, DJ; et al. High-frequency, high-resolution wastewater SARS-CoV-2 surveillance for public health action. Environ Sci Technol Lett. 2022, 9(2), 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deboosere et al. (Correct)Deboosere N, Horm SV, Delobel A, et al. Survival of viruses on fresh produce, using MS2 bacteriophage as surrogate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012; 78:3242–3248. [CrossRef]

- Bivins; Bibby Bivins, A; Bibby, K. Wastewater surveillance during and beyond COVID-19. Curr Opin Environ Sci Health 2021, 18, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClary-Gardner; McClary-Gardner, J; Chandra, F; Boehm, AB; et al. Quantifying uncertainty and variability in wastewater SARS-CoV-2 measurements: A multi-laboratory study. Sci Total Environ. 2023, 859, 160024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu; Liu, P; Ibaraki, M; VanTassell, J; Geith, K; Cavallo, M; Kannayan, A; et al. Modeling spatial and temporal variation in wastewater SARS-CoV-2 concentrations. Sci Total Environ. 2022, 829, 154622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Africa CDC – Correct institutional citation Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Early Warning and Surveillance Strategy 2023–2027. Addis Ababa: Africa CDC; 2023.

| Pathogen Group | Specific Pathogens | Preferred Detection Method(s) | Reference |

| Enteric viruses | Norovirus, Rotavirus, Enteroviruses, HAV | RT-qPCR, ddPCR | La Rosa et al., 2019 [19] ; Hellmér et al., 2014 [18] |

| Bacterial pathogens | AMR pathogens in sewage, Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Vibrio cholera | Culture, qPCR, sequencing | Van Zyl et al., 2017 [44] Hendrick sen et al., 2019 [81] |

| Protozoa | Giardia, Cryptosporidium | Immunofluorescence, qPCR | Kitajima et al., 2020 [14] |

| AMR markers | blaCTX-M, blaNDM, macrolide-resistance genes | qPCR, metagenomic sequencing | Hendriksen et al., 2019 [81] |

| Country | Study Focus | Pathogens Detected | Analytical Platform | Reference |

| Rwanda | SARS-CoV-2 wastewater surveillance and feasibility | SARS-CoV-2 (RNA) | RT-qPCR, passive sampling | Edson et al., 2025 [36]; |

| South Africa | National WBE network for COVID-19 | SARS-CoV-2, PMMoV | RT-qPCR, normalization | Street et al., 2024 [41] |

| Nigeria | Enteric virus detection | Enteroviruses, adenovirus, norovirus | RT-PCR, cell culture | Awolusi et al., 2023 [58] |

| Senegal | Fecal sludge/ Viral persistence | Enteric and respiratory viruses | RT-qPCR | Mendoza Grijalya et al., 2024 [43] |

| Egypt | Detection of HAV and HEV viruses | HAV, HEV | RT-PCR | Elmahdy et al., 2019 [59] |

| South Africa | Bacterial pathogen tracking | Salmonella, Shigella, Vibrio | Culture + PCR | Van Zyl et al., 2017 [44] |

| Pathogen | Rationale for Wastewater Detection | Analytical Platform | Reference |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Fecal shedding; mucosal shedding | RT-qPCR, ddPCR, sequencing | Kitajima et al., 2020 [14]; Edson et al., 2025 [36] |

| Influenza A/B | Fecal shedding in infected individuals | RT-qPCR | Wolfe et al., 2022 [85] |

| RSV | Presence in stool and respiratory excretions | RT-qPCR | Wolfe et al., 2022 [53] |

| Human adenovirus | Dual GI and respiratory involvement | qPCR | La Rosa et al., 2019 [19] |

| Pathogen | Correlation Outcome | Setting | Reference |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Wastewater signal increases precede clinical cases by 4 to 14 days | Rwanda, Europe, USA | Huisman et al., 2022 [31]; Edson et al., 2025 [36] |

| Norovirus | Wastewater peaks reflect seasonal occurrences | Sweden | Hellmér et al., 2014 [18] |

| Polio | Strong correlation between wastewater and AFP surveillance | Global (WHO) | WHO poliovirus guidelines, 2022 [49] |

| Hepatitis A | Strong correlation between wastewater and AFP surveillance | Japan, Italy | La Rosa et al., 2019 [19] |

| Category | Key Points | Reference |

| Strengths | Early detection, population-wide coverage, cost-effective, includes asymptomatic infections | Medema et al., 2021 [37] |

| Limitations | Infrastructure gaps, variable viral decay, quantification challenges, limited lab capacity | Wade et al., 2022 [79] |

| Opportunity Area | Description | Reference |

| Passive sampling | Low-cost, suitable for irregular sewage systems | Liu et al., 2022 [89] |

| Integration with Africa CDC networks | Strengthening surveillance through genomics initiatives | Africa CDC, 2023 [90] |

| Urban sanitation expansions | Improving coverage in cities such as Kigali, Nairobi | UN Urbanization Report 2022 [49] |

| Workforce and lab capacity-building | Training in PCR, sequencing, AMR monitoring | Hendriksen et al., 2019 [81] |

| Country | Research topic | Disease/Pathogen identified | Papers | Platform used |

Scientific References |

| South Africa | SARS-CoV-2 detection in municipal wastewater | COVID-19 | 6+ | RT-qPCR, Sequencing (illumine) PEG concentration | Johnson R. et al., 2021 [50]; Lester et al., 2022 [51]; Street et al., 2024 [52] |

| Poliovirus environmental surveillance | Polio (WPV, cVDPV) | 3 | Cell culture, RT-PCR | Mahlangu et al., 2019 [53]; Gumede et al., 2020 [54] | |

| AMR genes in wastewater | Antimicrobial resistance | 2 | Metagenomics, qPCR | Nkado R. et al., 2020 [55] | |

| Nigeria | Poliovirus environmental surveillance (national surveillance program) | Polio | 5+ | PCR, cell culture | Adeniji et al., 2017 [56]; Baba et al., 2018 [57]; |

| SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater | COVID-19 | 1 | RT-qPCR | Awolusi et al., 2023 [58] | |

| Egypt | Hepatitis A&E monitoring in wastewater | HAV, HEV | 2 | RT-PCR | El-Mahdy et al., 2019 [59]; El-Said et al., 2020 [60] |

| SARS-CoV-2 detection | COVID-19 | 1 | RT-qPCR | Shawky et al., 2021 [61] | |

| Tunisia | SARS-CoV-2 detection in wastewater | COVID-19 | 2 | RT-qPCR; | Barhoumi et al., 2021 [62]; Wurtzer et al., 2021 [63] |

| Morocco | Surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in urban wastewater | COVID-19 | 1 | RT-qPCR | Nasseri et al., 2021 [64] |

| Kenya | Antibiotic resistance bacteria in wastewater | AMR bacteria (E. Coli, Klebsiella, Salmonella | 2 | Culture, AST, PCR | Kiiru et al., 2018 [65]; Omwandho et al., 2019 [66]; |

| SARS-CoV-2 wastewater surveillance | COVID-19 | 1 | RT-qPCR | Oyaro et al., 2021 [67] | |

| Uganda | AMR monitoring in wastewater | Resistance E. Coli & Enterococcus | 1 | Culture based, PCR | Katongole et al., 2020 [68] |

| Ghana | Environmental detection of enteric viruses | Norovirus, Rotavirus, Adenovirus | 2 | RT-PCR | Armah et al., 2016 [69]; Aboagye et al., 2018 [70] |

| Senegal | Polio environmental surveillance | Polioviruses | 2 | Cell culture, PCR | Diop et al., 2014 [71]; Mendoza et al., 2024 [72] |

| Zimbabwe | SARS-CoV-2 surveillance | COVID-19 | 1 | RT-qPCR | Manangazira et al., 2021 [73] |

| Rwanda | SARS-CoV-2 detection in municipal wastewater | COVID-19 | 2 | RT-qPCR, viral concentration (PEG) Sequencing support via regional labs | Uwimana A. et al., 2022 [74]; University of Rwanda - RBC wastewater monitoring report, 2021 [75] |

| Development of wastewater surveillance framework for early outbreak detection | Multi-pathogen (SARS-CoV-2) enteric viruses | 1 | RT-qPCR, environmental sampling protocol | Ndayishimiye et al., 2023 [76] | |

| Airport-based WBE and genomic surveillance using aircraft wastewater and pooled nasal swabs from international travelers at Kigali International Airport | SARS-CoV-2 and variants and other imported lineages | ≥2 peer-reviewed genomic surveillance studies using wastewater & swabs at the airport | Aircraft wastewater sampling + pooled nasal swabs; RT-qPCR and whole-genome sequencing to detect/imported variants; integration with national genomic surveillance | Edson R et al., 2025 [36]; (Misbah G et al., 2025 [77] | |

| Ethiopia | AMR genes | ARGs (blaCTX-M, mecA, etc.) |

1 | qPCR | Alemayehu et al., 2020 [78] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).