1. Introduction

Precision aerial seeding technology using unmanned-aerial vehicles (UAVs) is being developed as a promising tool for ecological restoration, precision agriculture and post-disaster vegetation rehabilitation. Aerial seeding holds the potential for significantly faster coverage (an order of magnitude) than in manual planting; however, flying higher to avoid obstacles or cover larger swaths increases wind-driven drift and turbulence driven spread. The literature contains altitude heuristics or wind-agnostic rules, which give some quantitative guidance on selecting the flight parameters or a path plan under site-specific winds. In this context, drones are especially effective for extending assets on steep and difficult terrain, achieving higher-spatial accuracy with lower cost and less human risk than traditional ground or manned aircraft approaches. However, utilization of this potential is contingent on maintaining control of seed delivery under environmental perturbations such as wind, turbulence, and timing jitter that collectively define the probability seeds are effectively delivered to inside the target zone. Achieving reliable placement is challenging as the drop is governed by coupled aerodynamics, stochastic winds, and operational uncertainties, despite progress toward autonomy and flight stability. Most of the existing mission-planning tools are often calibrated with empirical ad-hoc corrections, and no consistent physical relation can be assumed to connect input environment parameters with accuracy figures. Thereby, they cannot predict the performance of recall or reset flight parameters in real time.

Building on these per-cell estimates, this work fills the existing gap through a physics-informed, context-aware framework enabling the direct linkage of observable factors to mission-level end states. We integrate quadratic-drag fall dynamics, height-resolved wind profiles, and finite-time turbulence dispersion compensated with a timing-, heading- and wind direction-dependent error budget. From these components, we compute

for a chosen cell size, a continuous center-proximity score, CEP

50/CR

95 accuracy radii, and an along-/cross-track breakdown to diagnose sensitivity to relative wind angle and control errors. The optimizer applies angle-aware lead compensation to keep the mean impact centered and then searches height-speed-heading settings that minimize spread under the current environment. In this paper, we model aerial seeding as a cell-based targeting with an explicit environmental description,

where

is the 10-m wind speed,

is the wind direction, and

I represents the turbulence intensity. For any grid cell, we predict

and aggregate over the selected cells to obtain the overall recall. To compute these cell-level hit probabilities under a given environmental state

, deterministic and stochastic mechanisms governing dispersal. The drop is modeled with transparent, reproducible components:

Fall time from quadratic drag, capturing propagule mass/area/drag dependence. (e.g.,

, with terminal speed

[

1,

2,

3,

4].)

Mean drift as the vector sum of platform motion and wind at release height, expressed in along-/cross-track coordinates tied to the current heading .

Turbulence-driven spread via an Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process with a height-dependent Lagrangian time scale, yielding closed-form integrals for position variance over the fall.

Operational error budget that incorporates release-timing jitter, small heading deviations, and wind-direction uncertainty so predictions reflect field realities.

To make the framework useful, we developed an interactive dashboard that translates these equations into decision support in real-time [

5]. It both calculates and visualizes the impacts of altitude, velocity, and heading on recall given current winds; generating operating envelopes which identify safe and efficient regions for a specific accuracy level. Our contributions in this paper are summarized as follows:

Physics-grounded model. A concise, reproducible formulation combining quadratic-drag fall time, a height-varying wind field, Ornstein–Uhlenbeck (OU) turbulence, and a calibrated operational error budget to explain accuracy across environments.

Performance in visible metrics. To evaluate our environment formulation, we report several key performance parameters such as hit probability, center-proximity score, CEP50/CR95, and along-/cross-track error decomposition reveal how height, speed, and heading shape precision and recall.

Practitioner-ready tooling. A lightweight, web-based dashboard renders KPIs, visual maps, and “what-if” analyses to guide operators toward height-speed-heading choices and flight paths that maximize recall for a given environment.

Environment-aware optimizer. Given ambient conditions (10 m wind speed, wind-to direction, and turbulence intensity), the system recommends the drone’s height, speed and heading to maximize hit rate under throughput and safety constraints.

These contributions deliver a reproducible and interpretable decision-support system for precision aerial seeding, integrating physics-based modeling, probabilistic reasoning, and real-time planning into a single operational tool.

2. Related Work

We leverage previous work in four areas related to UAV-based aerial seeding: (i) application field experience in forestry and agriculture, (ii) mathematical models for drop accuracy, and (iii) wind-aware path and coverage planning, and (iv) metrics for quality of accuracy results. We conclude with the gap motivating our approach.

2.1. UAV Seeding in Forestry and Farming

UAV seeding has recently been recognized as a rapid and inexpensive tool for restoration and reforestation, with significant emerging applications in post-fire forests or coastal systems such as mangroves [

6,

7]. However, most previous engineering articles focused on dispenser mechanics with the distribution uniformity (row/broadcast width, metering, blockage) [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] instead of end-to-end placement accuracy under wind. In this case, we reformulate the aerial seeding problem as a

targeting problem and calculate hit probability at a per-cell level based on flight characteristics and flow properties.

2.2. Drop Accuracy Relevant Dispersion Models

For transport within the atmosphere, Lagrangian stochastic (LS) formulations are widely considered to be the envelope of particle dispersion as it is based on well-mixed condition [

13,

14,

15]. At the aircraft height, wind shear and turbulence intensity dominate spread; in practical vertical interpolation log-law or power-law profiles are typically used as a function of roughness and stability [

16,

17]. This body of literature provides validated structure for drift and spread, but is seldom linked to UAV seeding (a process that will lead to route- or cell-level recall). In this paper, we close this gap by considering a Langevin spread in the spirit of OU (Ornstein–Uhlenbeck) process and explicitly accounting for its influence on the hit probability.

2.3. Accuracy Metrics and Reporting

Navigation and airdrop communities characterize horizontal error with CEP and

derived from the Rayleigh/Rice family for 2-D Gaussian possibly-biased error [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. We adopt these conventions–reporting CEP50/CR95 along with a task-relevant “hit within cell” probability with each report, and we additionally disaggregate error into both along- and cross-track error contributions to demonstrate how heading relative to wind conditions influences performance. We further separate mean bias (lead-compensable) from random spread (turbulence/jitter), clarifying when Rayleigh (mean-centered) versus Rice (offset) statistics apply.

2.4. Summary and Gap

Existing work shows that UAV seeding is observable, wind-aware routing is necessary, but there does not exist a

white-box, equation-level connection from flight parameters and wind to each cell’s hit probability and the route tirple’s given recall. This paper addresses this gap with a physics-inspired model, route-informed scoring, and a replicable implementation that can be tuned to site-specific winds by practitioners, providing a transparent, equation-level connection between flight parameters, wind, and seeding accuracy. As an external point of reference for the resulting accuracy estimates, and to partially mitigate the limited availability of field datasets at the planning stage, we include a consistency check by comparing our predicted

and hit probabilities under representative conditions with published UAV seed-dropping field accuracy at comparable release heights [

23].

3. Physics-Based Model and Rationale

In this section, we model the near-surface horizontal transport of a seed/propagule deployed from a UAV. The model is environment-aware: wind comes in via where (m s−1) represents the mean wind at 10 m; is the wind direction, and I is the Turbulence intensity. As well, drone control enter via , where H is the height of drones; is the airspeed and is the UAV heading. These parameters constitute the core inputs to formulate our environment in the next sections. We first derive the exact fall time at height H, , under quadratic drag, which defines the exposure time for drift, turbulence, and operational errors. Next, we map the 10 m reference wind to the release height to obtain that represents the wind speed at height H. Using , , the airspeed , and the relative angle between and , we compute the mean drift in the heading frame. Then, we model the finite-time turbulent spread with an Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process. We propagate operational errors to obtain the axis-wise spreads . After that, we define an effective isotropic spread for circular acceptance, where a drop is counted as a hit if it lands inside the target circle of radius r. Finally, we evaluate the closed-form hit probability , which is used in the recall model.

A. Vertical Descent Under Quadratic Drag (Summary; Calculation Introduced in A)

In this section, we determine the physically consistent

fall time from release height

H, assuming the quadratic aerodynamic drag. We will derive the expression

used to represent the exposure time for mean drift, turbulence and operational errors. Let’s start with the Newton’s second law with the quadratic drag [

1],

We adopt a downward-positive vertical coordinate

z;

m is the mass in kg;

g denotes the gravitational acceleration in m s

−2;

is the air density in kg m

−3;

represents the dimension less drag coefficient, taken approximately constant over the descent;

A is the projected area, in m

2 ;

represents the downward vertical speed in m s

−1. During steady descent, gravity and drag are in equilibrium; from (

3.1) with

, we obtain:

where the terminal speed

is understood as a constant aerodynamic steady descent speed at which drag balances gravity. With the above equation, (

3.1) reads as:

with release from rest

. Then, the fall time to drop a distance

H is given by the closed-form expression (derivation is reported in

Appendix A):

For small heights (), (ballistic/free-fall). For large heights (), (near-terminal speed).

B. Mean Wind at Release Height

In the following, we map the 10 m reference wind to release height

H to estimate the mean advection velocity utilized in drift and turbulence. Following the empirical boundary-layer wind profile, we can write

as follows [

24]:

where

represents the standard one-parameter approximation over this narrow layer and homogeneous exposure.

summarizes roughness/stability effects; In our simulation, we set

to 0.2, commonly used over open terrain. Site-specific values should replace the default when available.

C. Mean Drift in the Heading Frame

For this purpose, we calculate in the following the mean horizontal displacement during the drop,

, and use it to (i) pre-compensate the aim point and (ii) transmit the mean offset into the recall model. During the short fall time

T, consider airspeed and the mean wind at release height constant. Using

to-bearings for heading

and wind

, we define the relative wind angle

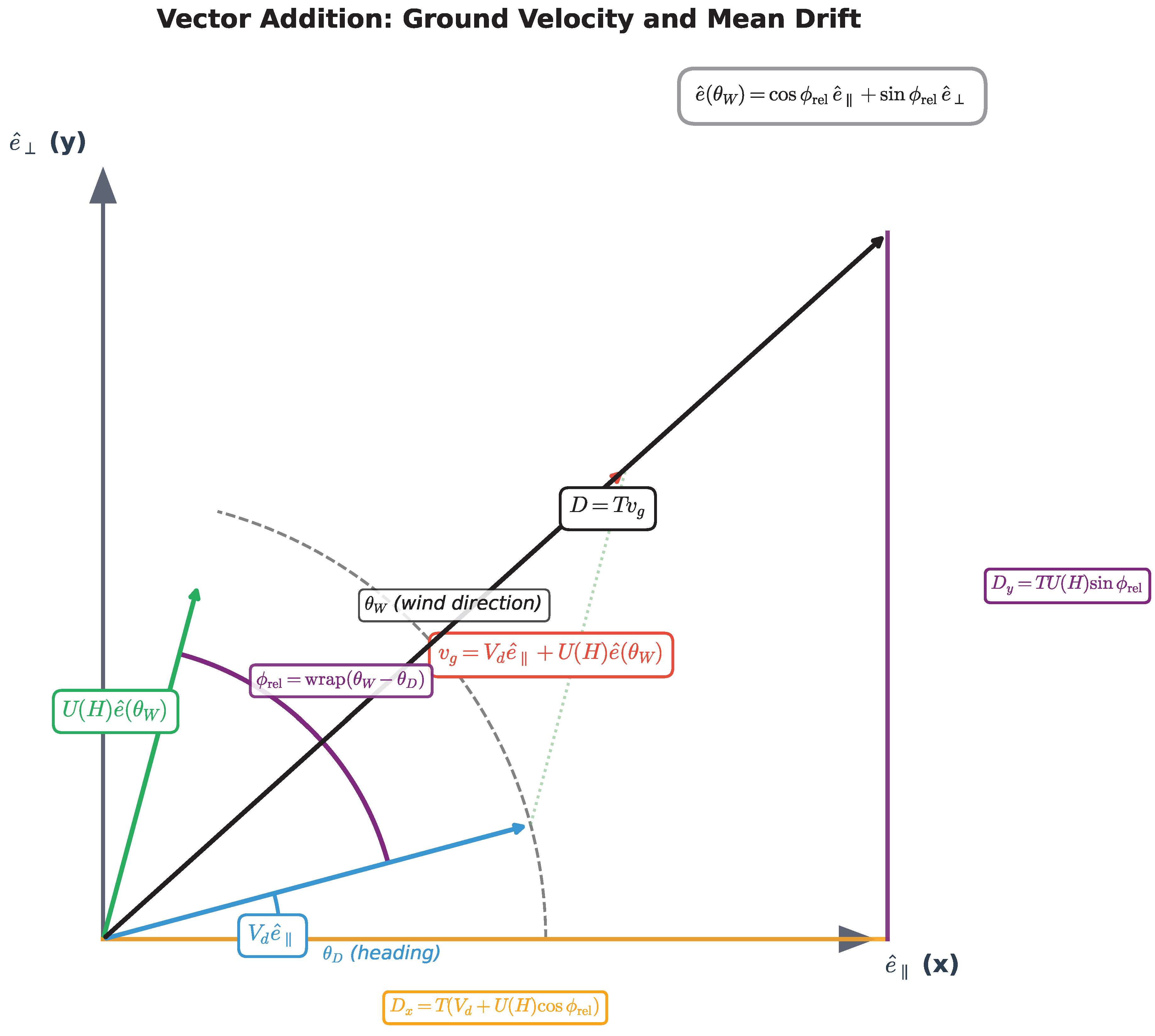

Figure 1 provides an illustrative view on the geometric configurations between the wind direction

and the UAV heading

, and their relative angle

. Let

be the heading-frame basis with

along the vehicle heading (

x) and

left-positive cross-track (

y). The mean wind vector at height

H pointing toward

can be expressed in this frame via the relative wind angle

as,

Thus, the ground-relative velocity during the drop is

Over the short fall time

T, we treat

as a constant

1 , so the mean displacement is

, which yields

Equivalently,

d is the

mean shifting distance from the release point to the expected landing point during the drop. Further details on

D,

and

are provided in

Appendix B.

Figure 1 also illustrates the mean displacement vector

and its components

from the target point to the expected landing point during the drop.

D. Turbulence-Driven Spread (Summary; Full Derivation in Appendix C)

While the mean-drift model in Sec. 3 C determines the expected impact point of the propagule, real atmospheric conditions rarely allow such deterministic precision. Short-time gusts during the drop (

,

from Sec. A) produce stochastic displacements about that mean. To represent the measured near-surface Lagrangian statistics-zero mean, exponential temporal autocovariance, and Gaussian increments, we model each horizontal fluctuation

,

2, as an Ornstein–Uhlenbeck (OU) process [

13,

25,

26]:

where

is the RMS gust speed and

the Lagrangian integral time scale. OU is the minimal Gaussian–Markov model that (i) reproduces the observed exponential memory, (ii) has physically interpretable parameters

, and (iii) yields closed-form finite-time dispersion, avoiding Monte-Carlo time stepping [

13,

25].

Let the turbulent displacement accumulated over the exposure is

. For the OU model,

is Gaussian with zero mean and following variance (see

Appendix C for more details),

Hence, we obtain the definition of the RMS Turbulent Displacement as follows:

This expression shows that the RMS turbulent displacement (in meters) is directly proportional to the RMS gust velocity (in m/s) and the eddy memory time (in s). Physically, determines the strength of the random velocity fluctuations in axis i, while characterizes how long these fluctuations remain correlated during the particle’s fall. The multiplicative term acts as a finite-time correction that transitions smoothly between the short-exposure (ballistic) and long-exposure (diffusive) regimes.

To make the turbulent spread model fully consistent with the mean-drift framework (Sec. 3-C), we express the stochastic parameters

in terms of measurable atmospheric quantities. In practice, wind-field data and seeding flight logs provide the mean wind speed

and the turbulence intensity

I, rather than the RMS turbulent velocity components

directly [

25,

27]. Accordingly, we map the latter to the available quantities through the empirical relationships [

28],

The

factor accounts for the measured lateral-to-streamwise anisotropy of turbulence in near-neutral boundary layers. Introducing these relations here is necessary because the OU model requires the fluctuation amplitude

as input. Thus, equations (

3.11)– (

3.14) establish the complete link between measurable atmospheric parameters and the turbulence-induced position spread

. The later parameter is then used in variance with timing/heading/wind-direction/mechanical terms (Sec. E) in order to form the total spreads by the hit-probability

calculation (Sec. G).

E. Operational error budget

Even with a physically correct exposure time

and mean wind

, real-world releases remain imperfect. Indeed, the trigger fires slightly early/late (

timing jitter ), and the vehicle heading wobbles by small angles about the commanded track (

heading jitter ). Moreover, a small uncertainty in the wind direction (

wind-direction jitter ) also persists over

T. Each of these mechanisms translates directly into meters during the short drop and, if omitted, biases the predicted spreads

downward and inflates

. Below, we map these jitters into axis-wise distance standard deviations using the same heading frame and exposure

T as in Secs. A–D. From Sec. C, the along-track ground speed is

For timing jitter,

with

, so

For heading error

, we pre-compensate by an upstream leg of length

A small yaw error

rotates that leg, producing a cross-track miss

, hence

For wind-direction error

, a small angle error

rotates the wind, introducing a cross-track speed

sustained over

[

25,

27]. Start from the mean horizontal wind vector components:

Now, we perturb the wind direction by a small angle

:

For small

(in radians),

Therefore, the change in the crosswind component (lateral speed error) is

Assuming this small misalignment persists during the drop time

T, the corresponding lateral displacement is

consistent with linearized lateral-drift kinematics [

29].

If

is a zero-mean random variable with standard deviation

, the standard deviation of the induced lateral displacement is

which follows the standard first-order (small-angle) linear propagation of uncertainty [

30]. Combining turbulence-driven spreads from Sec. D with operational terms (and a small mechanical floor

3), we obtain:

The resulting are in meters and feed directly into the recall model (Sec. G).

F. Effective isotropic spread for a circular acceptance

We evaluate accuracy with a circular acceptance of radius

r. The landing error in the heading frame is Gaussian with axis-wise standard deviations

from Secs. D–E. With a circular acceptance, we use an isotropic surrogate matched by the radial second moment, so hit probabilities follow the Rayleigh (zero-mean) or Rice (biased) forms [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35].

For a zero-mean bivariate , we obtain

For an isotropic normal with variance

on each axis,

. Equating the two gives the effective isotropic spread,

which preserves the radial second moment appropriate for circular acceptance and enables the closed-form Rayleigh/Rice hit probabilities widely used in practice [

31,

32,

34,

35].

G. Hit probability for a circular acceptance

We assess accuracy against a circular acceptance of radius

r: a drop is counted as a hit if its horizontal miss distance

R from the target satisfies

. The mean horizontal offset of the expected landing point, due to mean drift (Sec. C), is denoted by

with magnitude

. Each individual drop then deviates randomly from this mean according to a zero-mean bivariate normal residual

with isotropic standard deviation

(from Secs. D–F). The total error relative to the target is thus

. Consequently, the radial miss

follows a Rayleigh distribution when

and a Rice distribution when

[

34,

35,

36,

37].

Case 1 — Mean-centered (): with lead compensation

This configuration corresponds to an intentional

lead correction before release: by leading the drop point (offsetting it by

), the drone can ensure that, on average, seeds hit exactly in their intended location. In this case, the mean of the impact distribution is equal to the target (

). Physically, this is achieved when the onboard planner or dashboard estimates the wind drift and correct the release point accordingly. All other error is pure randomness (turbulence, timing noise, low heading jitter), which produce a zero-mean cloud centered at the target. The distribution of the radial miss distance

R is, therefore a

Rayleigh distribution with scale

, and the probability for a hit inside an acceptance radius

r is

Practical interpretation: this represents the ideal operational mode once deterministic drift has been corrected, only stochastic errors remain. This case maximizes at the same pair .

Case 2 — Mean-offset (): without lead compensation

If the drone does no lead correction or even possibly a non-perfect compensation, in that case the mean impact point remains offset from the target by . The impact cloud center is nearer downwind or forward in the flight path.

In practice this happens when drops are actuated directly under the drone without compensating for drift, or when wind direction, timing delay, or sensor biases introduce systematic error.

In this case,

R follows a

Rice distribution (a non-central form of the Rayleigh), and the hit probability is

where

is the first-order Marcum

Q-function. A convenient closed-form approximation is

with

the modified Bessel function of order zero. As

, this naturally reduces to the Rayleigh case (

3.30).

Practical interpretation: the impact pattern is now systematically shifted; even with small random dispersion, many seeds fall outside the target area. Increasing d reduces rapidly.

In summary, when the lead is applied (

), the formulation in (

3.30) is employed. Otherwise, the Marcum–

Q expression in (

3.31) is adopted (available in standard scientific libraries [

36,

37]).

Table 1.

Definitions of symbols/parameters.

Table 1.

Definitions of symbols/parameters.

| Symbol |

Meaning |

Units |

| H |

Release height above ground |

m |

| m |

Seed/propagule mass |

kg |

| A |

Aerodynamic reference area (projected) |

m2

|

|

Quadratic drag coefficient |

– |

|

Air density |

kg m−3

|

| g |

Gravitational acceleration |

m s−2

|

|

Terminal speed (vertical) (3.2) |

m s−1

|

|

Exact fall time (3.4) |

s |

|

Wind speed at

10

m AGL |

m s−1

|

|

Power-law shear exponent (3.5) |

– |

|

Mean wind speed at height H (3.5) |

m s−1

|

|

Mean wind vector at H

|

m s−1

|

|

Wind-to direction (azimuth) |

rad or deg |

|

Vehicle heading (to) |

rad or deg |

|

Relative angle

|

rad or deg |

|

Vehicle airspeed along heading |

m s−1

|

| k |

Drag constant

|

m−1

|

|

Heading and cross-heading unit vectors |

– |

|

Along-/cross-track drift (3.9) |

m |

|

Mean drift vector (3.10) |

m |

| d |

Mean offset

|

m |

| I |

Turbulence intensity |

– |

|

Turbulent stdevs (along/cross) |

m s−1

|

|

Lagrangian timescale |

s |

|

Timescale constant (2–5) |

– |

|

Turbulent position spreads (OU) |

m |

|

Release-time jitter stdev |

s |

|

Heading jitter stdev |

rad |

|

Wind-direction uncertainty stdev |

rad |

|

Sensor/mechanical error floor (per axis) |

m |

|

Total along/cross spreads (3.26)–(3.27) |

m |

|

Effective isotropic spread (3.29) |

m |

| s |

Cell side length |

m |

|

Acceptance radius

|

m |

|

Hit probability (Rayleigh/Rice) |

– |

|

50% circular error probable |

m |

|

95% containment radius |

m |

4. From Model to Tool: Real-Time Seeding Planner (Dashboard & Package)

In this section, we operationalize the modeling in Sec. 3 into a lightweight, user-friendly planner. Given the release height H, airspeed , 10-meter wind speed , and wind direction , the planner evaluates:

Exposure time (Sec. 3 A).

Mean wind at height via the power law (Sec. 3 B).

Mean drift and in the heading frame (Sec. 3 C).

Turbulence spread from OU finite-time dispersion (Sec. 3 D).

Operational errors (timing, heading, wind-direction) mapped to meters (Sec. E), combined axis-wise to .

Effective isotropic spread (Sec. 3 F).

Hit probability for circular acceptance of radius r (Rayleigh for lead/, Rice/Marcum–Q for no-lead/, Sec. 3 G).

Our dashboard presents: (i)

Recall vs. height at fixed speed; (ii)

Drift vs. height with signed

; (iii)

Recall vs. speed; (iv)

error breakdown (turbulence, timing, heading/wind, total RMS); (v)

operational zones across

; (vi) a

speed–height map with per-cell

. These views are computed from the same analytic expressions as the paper and update in real time as

H,

,

,

, turbulence intensity

I, and cell size

s change.

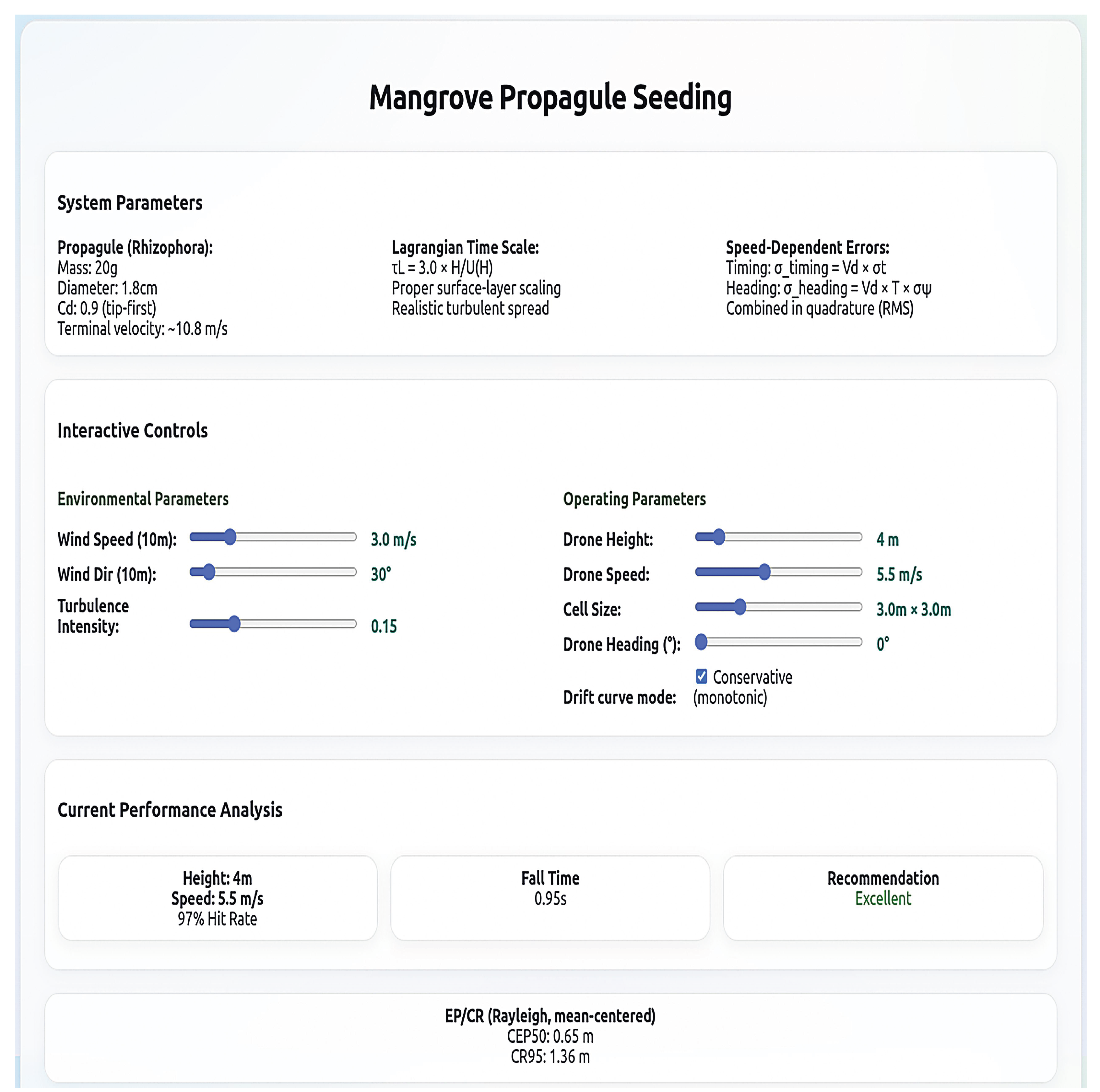

Figure 2 illustrates the interactive dashboard implementing these computations; the live version is available at [

5].

In our dashboard, all plots are calculated from closed-form expressions (no Monte Carlo), ensuring that all parameters are updated instantaneously and reproducibly from a parameter JSON file. The artifact uses the same symbols and equations as the manuscript; parameter defaults (e.g., , ) can be overridden to match site surveys. A rule-based layer evaluates and the current . If the predicted recall falls below target, it emits concise, actionable guidance (e.g., “lower H to m” or “reduce to m s−1”), so adjustments act on the correct levers—exposure , along-track speed, and cross-track wobble—rather than implicitly retuning turbulence. For decision support, we classify settings as Excellent (), Good (80–96%), or Low (), using per-cell . To navigate throughput/safety trade-offs, we perform a grid or Bayesian search over to maximize recall and produce height–speed–heading maps annotated by these classes.

To demonstrate how the framework operates under real conditions, we present two operating examples that can be evaluated in closed form and validated against the dashboard. All aerodynamic and stochastic ingredients follow Secs. 3 A-G. We assume a circular acceptance of radius r (Sec. 3 F) and lead compensation so that the mean bias is zero (, Sec. 3 C). Later setting yields Rayleigh statistics for the hit probability.

Shared dashboard defaults: Unless stated otherwise, we use s, rad), rad), m, m, m s−1, and m s−2.

Example A (Excellent recall; dashboard: 98–99%)

Inputs: m s

−1,

,

,

m,

m s

−1, wind-to

, heading

; hence the relative angle is

.

First, we compute the fall time (Sec. 3 A). With

, we have

Thus, sets the exposure window for turbulence and operational mappings.

Next, we evaluate the mean wind at height

H using the power law (Sec. 3 B):

Consequently, determines both advection and the turbulence velocity scale.

Then, in the drone-heading frame we form the along-track ground speed and the lead distance (Sec. 3 C), noting

:

After that, we map operational jitters to meters (Sec. 3 E) and combine by axis (Sec. 3 F):

Next, we compute finite-time OU spreads (Sec. 3 D). Since

s and

, the velocity RMS values are:

Hence, with

, the position spreads are

Combining these results, we obtain:

Consequently, the Rayleigh closed form (Sec. 3 G) yields

Dashboard expectation: Our dashboard, shown in

Figure 2, yields the same results when using the parameters of Example A, achieving a recall of 97%. Within this envelope, our calculations and dashboard indicate that

heights from up to a data-driven limit (here ) and

speeds from 1 to achieve excellent recall, thereby improving seeding safety (greater clearance, reduced vegetation interaction) and throughput (higher drone speed) while still meeting the recall target.

To put the dispersion levels obtained in Example A into context, we compare the resulting accuracy scales (e.g.,

,

, and drift–spread breakdowns) with reported placement statistics from recent UAV seed-dropping experiments. Although this work does not introduce new field trials, such a comparison provides a practical sanity check on whether the predicted footprints fall within realistic ranges. As a reference point, Lee

et al. [

23] report approximately

successful deployments and

accuracy at a

release height, with a reported

coverage circle of about

in controlled tests (and a mean offset of

) for a seed-ball dropping system.

Under comparable mild-wind conditions in Example A (

,

,

; lead applied,

), our closed-form model yields

and

for

; this corresponds to

and

(Rayleigh, mean-centered [

34]). These meter-scale containment radii are consistent with published field measurements at similar release heights, providing a sanity check that the model does not substantially under- or over-estimate placement dispersion in mild winds [

23]. Our main contribution is to extend these insights into a multi-parameter operational tool that explicitly maps accuracy over wind speed, wind direction, heading, flight speed, and turbulence intensity. Future work, will conduct controlled hover- and in-flight drop tests under measured wind conditions to quantitatively validate the predicted

and

across a wider range of operating regimes.

Example B (low recall under tailwind alignment)

Inputs: m,

,

,

,

,

,

(

),

,m; lead applied (

). Then

,s,

,m,s

−1,

,m, and

,m, giving

Dashboard expectation:∼30% (“Low recall”), corresponding to the near-tailwind, high drone altitude-height, gusty conditions. In this example, the combination of high release height ( m), stronger wind ( m s−1, ), and near-tailwind alignment () drives a large along-track ground speed and long lead distance ). Consequently, the timing and heading jitters are mapped into large meter-scale spreads (via and ), while the longer exposure increases the finite-time OU dispersion. With lead applied (), the mean is centered and the Rayleigh law depends only on ; here, m is comparable to the acceptance radius ( m), yielding low recall. To increase under the same conditions and zone, the following controllable levers can be adjusted: (i) reduce height (e.g., m) to shorten and OU spread; (ii) increase the heading from the wind (increase to 10–) to reduce and ; (iii) tighten the trigger () to shrink the dominant along-track term; or (iv) enlarge the acceptance radius r (larger cell). Each change of the later recommendations can reduce and, by the Rayleigh mapping, increases .

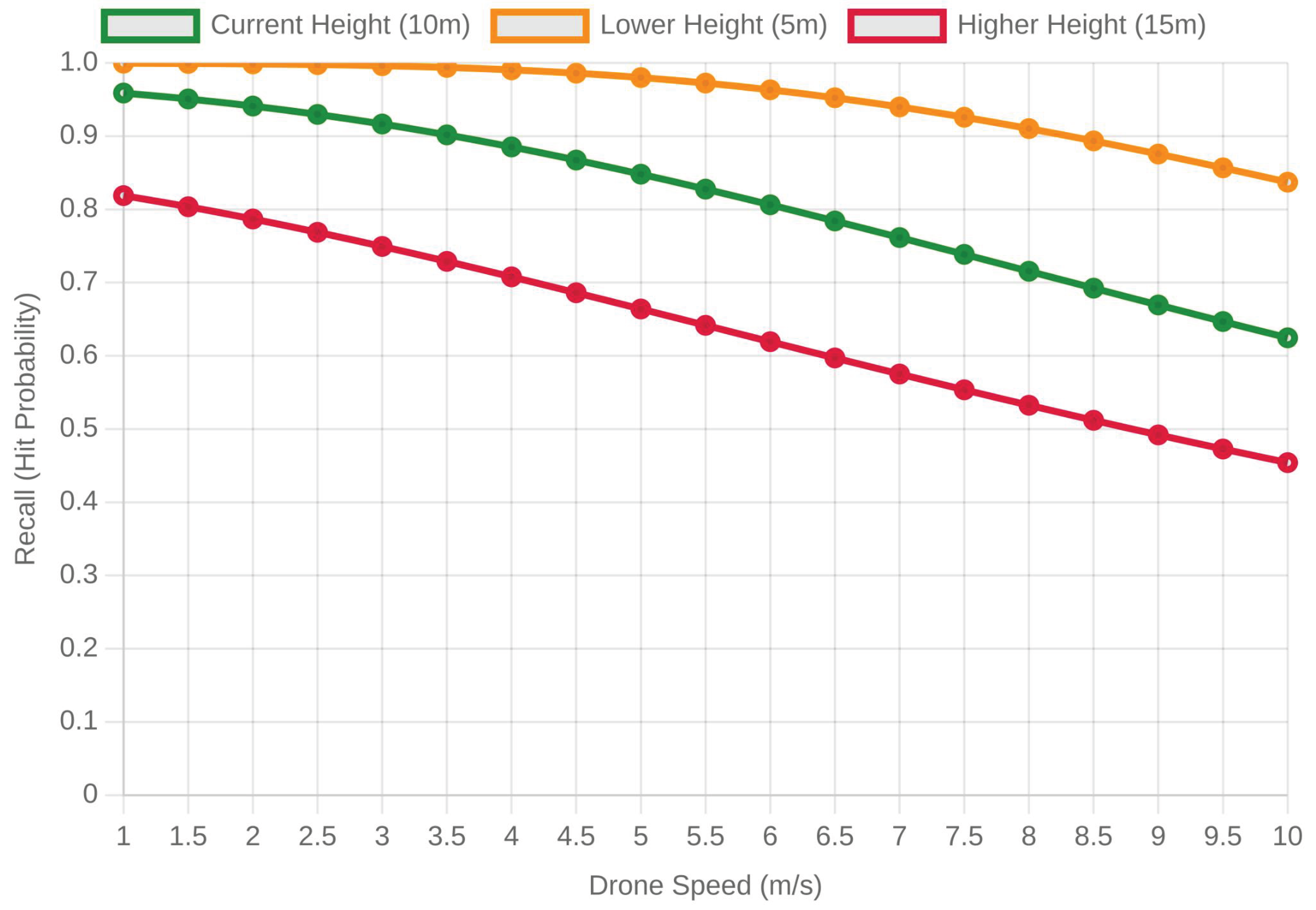

To bring the above analysis into a concrete form for such conditions, we first measure how recall depends on speed while fixed the heights as in

Figure 3. The curves show the hit probability (recall) as a function of drone speed for three different release altitudes:

5 m (orange)

5 m (orange): lower release, best precision, minimal wind exposure;

10 m (green)

10 m (green): nominal operating altitude;

15 m (red)

15 m (red): higher release, more drift, degraded accuracy.

Across all heights, recall drops with speed at all height. The drop is shallow at as the fall time is low and becomes steeper at where seeds stay longer in the air. The greater vertical separation enables the horizontal wind and control errors to accumulate and hence results in a more widespread dispersive footprint. This plot provides direct evidence of the trade-off between operational efficiency and precision: Fly higher (or faster) to cover more area at the cost of losing precision. For an optimal mission, therefore we trade-off throughput with acceptable loss in recall.

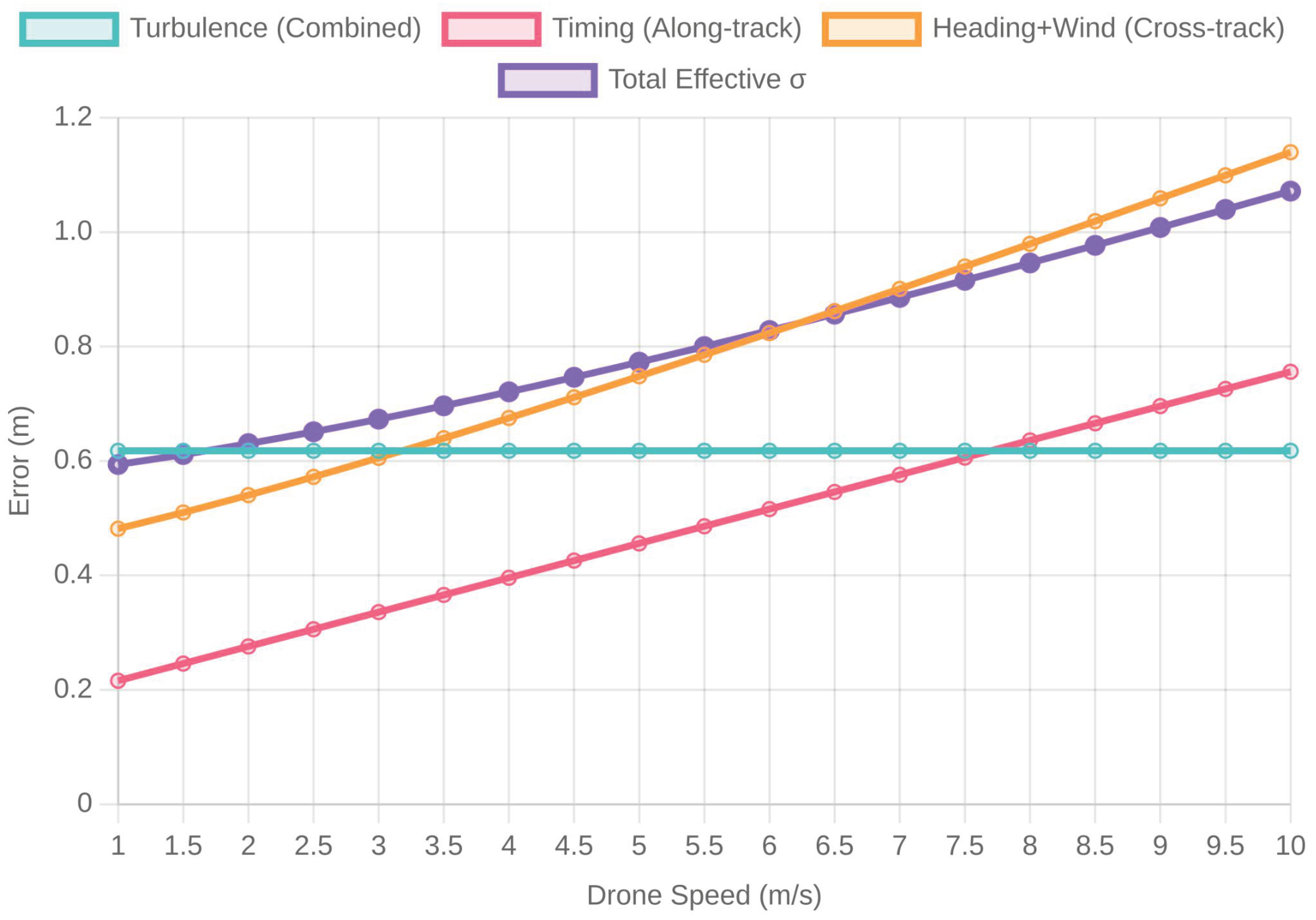

To explain why recall decreases as speed rises, we plot in

Figure 4 the effective error at fixed height and wind. The turbulence term is approximately constant (turquoise,

m), since finite-time OU dispersion is set by

,

I, and

, not by

.

By contrast, operational terms evolve with speed: the along-track timing term scales with (pink, m from 1–10 m s−1), while the cross-track heading + wind term scales with and (orange, m), typically surpassing turbulence by –4 m s−1. The total effective spread (purple), lies between the axis-wise spreads and therefore follows the dominant contributor from below. Operationally, low speeds keep timing secondary; at moderate speeds the cross-track term is the first constraint; and at high speeds both timing and cross-track terms dominate. Practically, avoiding near-tailwind alignment (larger ), tightening trigger jitter, and stabilizing heading are the key levers; otherwise approaches m by m s−1, materially reducing for meter-scale cells.

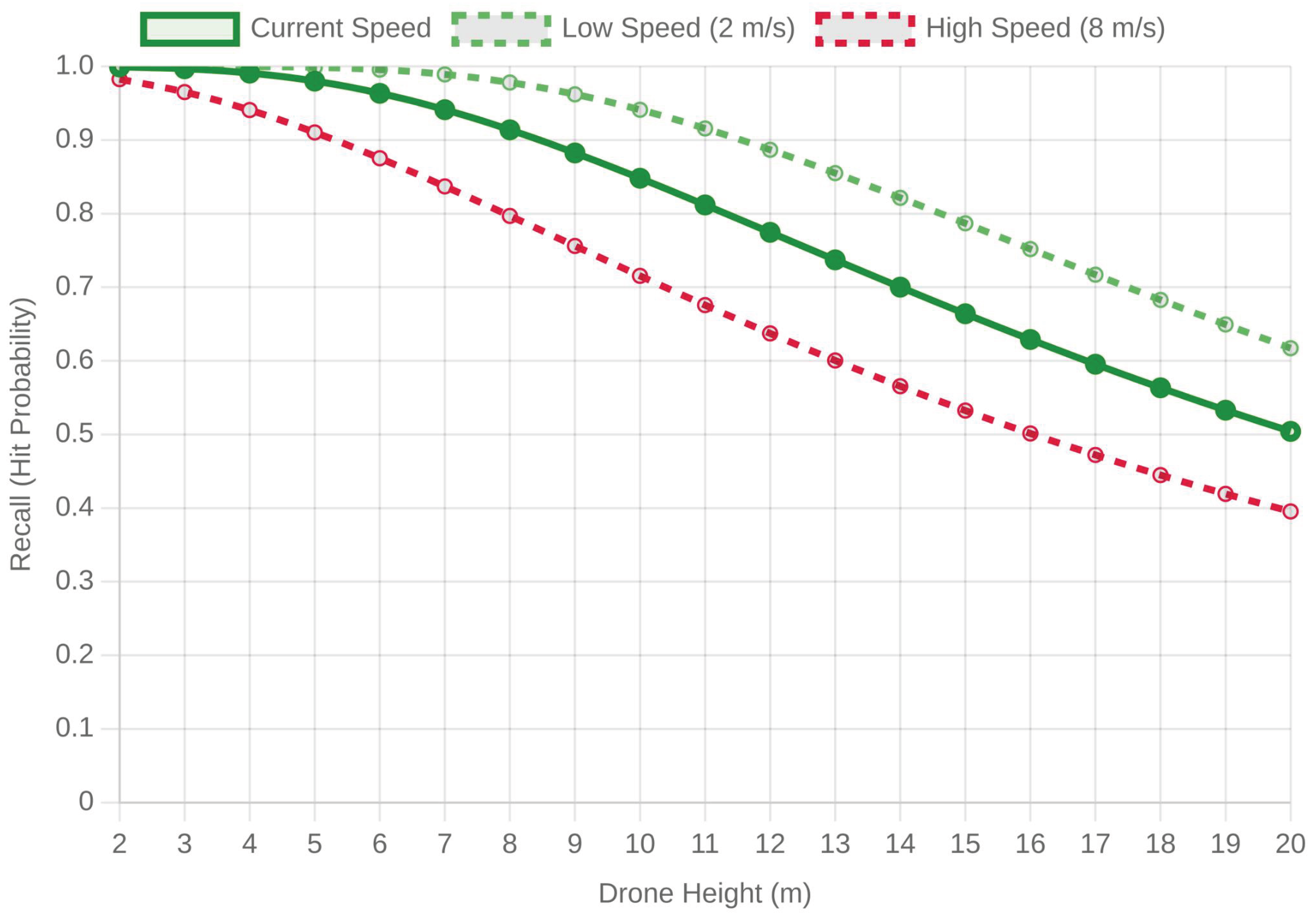

We now turn the view and investigate elevation sensitivity for several particular velocities, as illustrated in

Figure 5. The recall (

) was plotted as a function of release height for three drone speeds:

Low (2 m/s, green dashed)

Low (2 m/s, green dashed)

Nominal (current speed, solid green)

Nominal (current speed, solid green)

High (8 m/s, red dashed)

High (8 m/s, red dashed)

At any given speed, recall drops with altitude due to the longer descent and greater exposure to turbulence and wind shear. Conversely, at any fixed altitude, increasing speed always results less recall, as along-track and cross-track errors increase almost linearly with speed. The figure demonstrates the dual sensitivity of recall to both parameters: the degradations due to altitude and due to speed compound rather than simply add. In practice, missions should jointly reduce these parameters in windy conditions or high precision tasks and have them raised only if throughput or battery savings is essential.

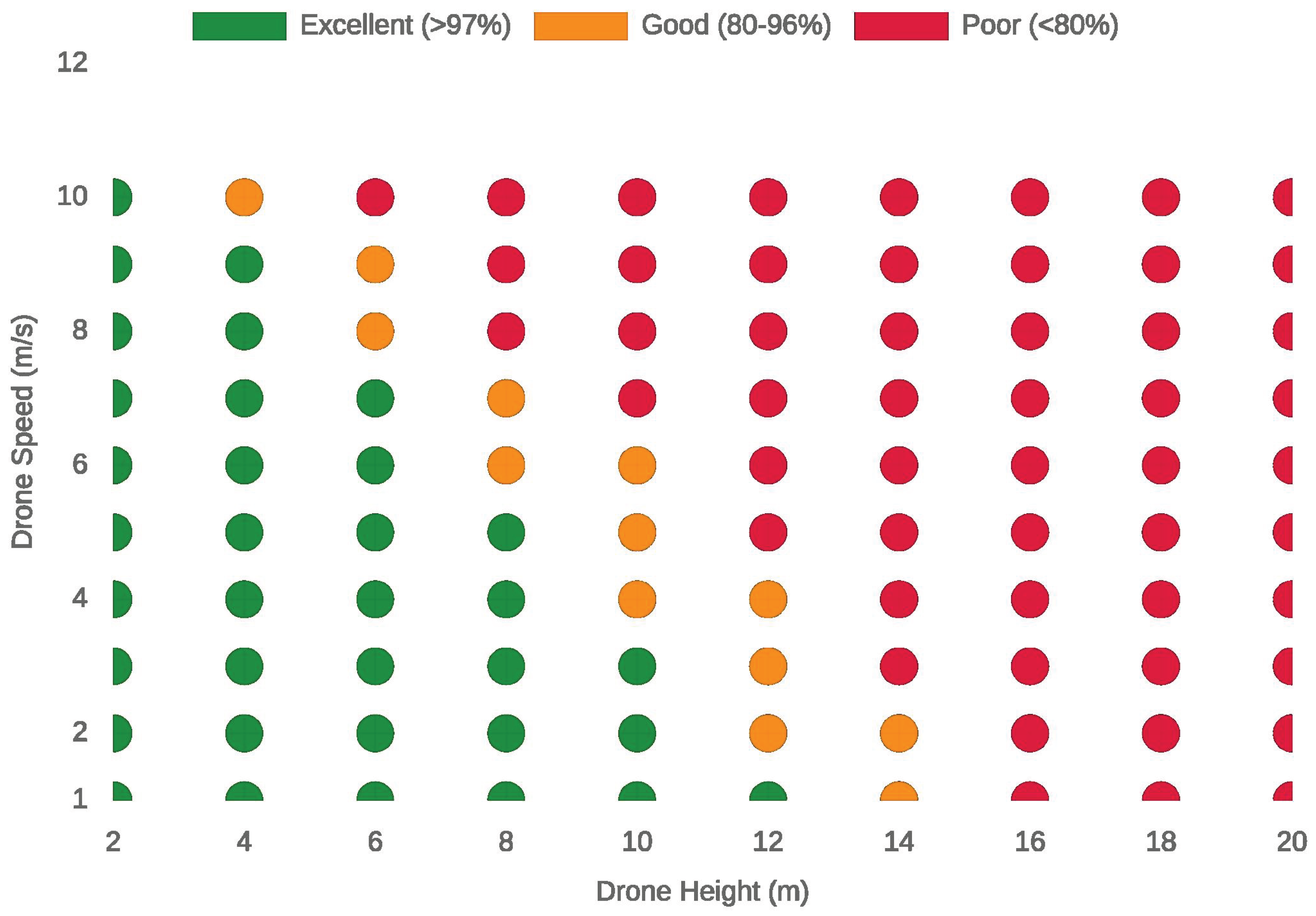

Finally, we combine both of the factors (Height and Speed) in one operational map as in

Figure 6. Each colored circle represents an (height, speed) pair of the parameters and by color also performance quality:

Green

Green: excellent seeding accuracy

Orange

Orange: acceptable or good performance

Red

Red: degraded performance

At lower altitudes (below 8 m) and moderate speeds (below 6 m/s), the hit probability remains high. The airflow perturbation is minimal, and the seed experiences less lateral drift and dispersion before impact. As height increases, or as drone speed exceeds 8–10 m/s, aerodynamic turbulence and timing error dominate. The seed’s descent time grows exponentially with height, exposing it to wind longer; meanwhile, at high speeds, along-track error caused by timing and heading misalignment expands the impact spread. The plot clearly highlights a safe operational corridor: a region of height–speed pairs where excellent recall can be maintained. With this map, operators can have a reference on how to setup their missions in mild winds and ensure accurate seeding.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we develop a general modeling and operational scheme for precision aerial sowing with variable wind conditions. By integrating analytical dispersion modeling with real-time presentation in an interactive dashboard, we turned intricate aerodynamic and stochastic activity into actionable operational advice. The proposed model relates observable flight characteristics such as height, speed the mean wind vector and turbulence intensity with a single probabilistic measure, , which can be used for quantitative assessment as well as intuitive decision making support.

By analyzing example scenarios such as the low-recall tailwind alignment or high-recall crosswind conditions in this study, we showed that recall performance sensitively depends on wind alignment, drone speed, drone heading and flight altitude. By mapping a recall target to the feasible height–speed envelope , the planner prescribes settings that maintain the required hit rate while transparently trading safety margin (height) against throughput (speed).

Apart from its analytical rigor, our dashboard makes environmental variability operational by defining data-driven limitations of flight to guarantee reliability and adaptability in the deployment zones. The future work will be to broaden the dashboard with autonomous adaptive control loops and to integrate field validation data in order to cover the simulation-to-reality gap. Collectively, the research provides a step towards field-scale sustainable accurate seeding operations.

| 1 |

The assumption that is constant during the short fall time T, however, has been successfully used in modeling near surface dispersion semi-classically [ 13, 25]. For typical release heights ( m), T is about one second, so any acceleration term contributes a second-order bias that is negligible relative to the modeled turbulent and operational spreads (Secs. 3–D,E). This approximation enables closed-form solutions without loss of predictive accuracy. |

| 2 |

is the total horizontal wind component along axis ; it is the wind actually observed at time t. The term denotes the random fluctuation about the mean. Accordingly, we decompose into a deterministic mean and a random fluctuation: . |

| 3 |

We include a small, nonzero mechanical floor to prevent a zero-variance artifact when aerodynamic terms are small, keep the hit-probability model well-posed, and avoid forcing turbulence/jitter parameters to absorb hardware imperfections. |

Acknowledgments

This brochure article is derived from a research grant funded by the Research, Development, and Innovation Authority (RDIA) - Kingdom of Saudi Arabia - with grant number 13010-Tabuk-2023-UT-R-3-1-SE.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Vertical Dynamics (Quadratic Drag) and Exact Fall Time

Predictions of mean horizontal drift and turbulence-driven dispersion depend on the exposure time to the flow. That exposure is the fall time from release height H under the same aerodynamics assumed elsewhere. This appendix derives the exact expression for descent with quadratic aerodynamic drag and defines the associated parameters (terminal speed) and , ensuring consistency with the horizontal model. Using the exact removes systematic biases in both mean drift and variance estimates.

Model and regime of validity. For small bodies descending in air at moderate–high Reynolds number (

in our applications), the drag magnitude scales as

with an approximately constant coefficient

over the operational range; see standard treatments in fluid mechanics and particle transport [

18,

38,

39]. This justifies adopting the quadratic-drag model for the vertical dynamics. (At very low

, Stokes drag would be more appropriate, but that regime is not considered here.)

Parameterization. When available, an empirically measured terminal speed is preferred. It implicitly captures shape, attitude, and modest variability in a single robust parameter, and it fixes the drag constant via . The same and k are used throughout the paper to keep the vertical and horizontal components aerodynamically consistent.

Sign convention and scope. We take the vertical axis downward-positive; gravity is , and quadratic drag acts upward (opposing motion). Mean vertical wind is neglected.

Provenance of the equations (sources). The drag law

comes from classical bluff-body aerodynamics [

3,

38]. The vertical equation of motion is Newton’s second law with gravity and opposing drag. The closed-form solution

and its height/time relations are standard results for motion under quadratic drag; see derivations in mechanics texts (e.g., [

40]) and fluid-dynamics primers (e.g., [

39]).

Aerodynamic drag law (quadratic):

with air density (kg m−3), drag coefficient (dimensionless), projected area A (m2), and speed v relative to air. Drag acts opposite velocity.

Assumptions and sign convention. Take z downward-positive, so gravity is and drag is upward (negative). We neglect mean vertical wind (no persistent up/down-drafts).

Newton’s second law (force balance):

Terminal speed and drag constant (tie to later sections). Steady descent (

) in (

A2) gives

Substitute into (

A2) to obtain the reduced ODE used in the main text:

Closed-form vertical speed (separable solution). Separate variables in (

A3) using

:

hence,

Height as an integral of velocity. Since

and

,

Exact fall time (invert ). Solving (

A7) for

t yields

For release from rest (

),

For tall drops (

), descent is near terminal speed,

These checks ensure the exact formula blends smoothly between physical regimes used for back-of-the-envelope estimates.

Appendix B. Mean Drift: Bearings, Components, and Refinements

Given a release at height H with fall time , we derive the mean horizontal displacement accumulated during the drop under a constant mean wind at the release height. The outputs are: the heading–frame components , the offset magnitude , formulas that accept wind-from inputs, and an optional refinement with horizontal quadratic drag (consistent with ).

Inputs and outputs. Inputs: (from Sec. 3 A), airspeed (m s−1), mean wind at height H, (m s−1), vehicle heading (to-bearing, rad), wind direction (to-bearing, rad). Outputs: in the heading frame (along-track x, left-positive cross-track y), its magnitude d, and (optionally) refined with horizontal quadratic drag.

Conventions and frame. We use to-bearings for both heading and wind. The heading frame is defined by unit vectors: along the vehicle’s heading (x axis) and left-positive cross-track (y axis). Angles are wrapped to with a function .

Assumptions and validity. Over the short drop (), the airspeed and mean wind are treated as constant (no strong shear, no significant maneuvering). This is the standard approximation for ballistic drops over a few seconds.

Step 1: relative wind angle. Define

Interpretation: means wind blows toward the nose (tailwind if “from”); means wind from the right (blowing left-to-right across the track).

Step 2: resolve wind in the heading frame. The mean wind vector at height

H has components

Step 3: ground-relative velocity. The constant ground-relative velocity during the drop is

Step 4: integrate over the fall time. Integrating

from

to

yields the mean displacement

with heading-frame components

The mean-offset magnitude is

Step 5: wind-from

inputs (direct use). If the forecast reports wind as

from , convert to

to with

. Equivalently, using

and

,

Step 6: lead compensation (how to use ). Aiming upstream by sets , centering the mean landing point on the target. Under symmetric spreads (Secs. D–G), this maximizes the hit probability.

Optional refinement: horizontal quadratic drag. For strict consistency with the vertical quadratic-drag constant

, treat the

air-relative components

with the same law. The per-axis closed-form integral over

T is

where

are the heading-frame wind components. For

(typical short drops),

and (

A8) reduces to (

A3)

- (A4).

Checks and units. are in meters; T in seconds; and in m s−1. Special cases: (pure along-track); (pure cross-wind contribution).

Appendix C. Finite-Time OU Turbulence and Displacement Variance

Aim.

Using the exposure from Sec. II A, derive axis-wise turbulent position spreads and justify the OU choice.

Why Ornstein–Uhlenbeck (OU)?

OU is the minimal Gaussian–Markov model with amplitude

(RMS gust) and memory

(Lagrangian integral time). It produces the exponential autocovariance commonly observed in surface-layer Lagrangian statistics and gives correct short-/long-time limits with closed-form integrals [

13,

25,

26,

41,

42,

43].

Model (per axis).

With the stationary initial law:

,

, and autocovariance

From velocity to displacement.

Define the turbulent displacement

. Because

is Gaussian and the integral is linear,

is Gaussian with

which is Eq. (

3.12) in the main text. Set

.

Parameters and units.

(m s−1): zero-mean turbulent velocity in axis i.

(m s−1): RMS gust speed in axis i.

(s): Lagrangian integral time scale (memory of ).

: Wiener process; .

(m): turbulent displacement over T.

Near-surface parametrization (neutral)

Here, is the mean wind at the release height (Sec. 3 B), I is turbulence intensity, and H the release height. We evaluate at (Sec. 3 A) for aerodynamic consistency.

Limits.

As : (ballistic). As : (diffusive with effective diffusivity ).

References

- NASA Glenn Research Center. Terminal Velocity. Beginner’s Guide to Aeronautics, 2010. Available online. NASA. (accessed on 2025).

- Anderson, J.D. Fundamentals of Aerodynamics, 5 ed.; McGraw–Hill Education: New York, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Clift, R.; Grace, J.R.; Weber, M.E. Bubbles, Drops, and Particles; Academic Press: New York, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, S. Leaves in the Wind: Aerodynamics of Plant Propagules. American Journal of Botany 2009, 96, 1532–1545. [Google Scholar]

- Almasri, M.; Alhmiedat, T.; Namazi, M.A.; Ershath, M. Mangrove Propagule Seeding: Interactive dashboard for time-aware path planning with stochastic wind. 2025. Available online: https://aist-drone.netlify.app/ (accessed on Nov. 20 2025).

- Mohan, M.; et al. UAV-Supported Forest Regeneration: Current Trends, Research Directions, and Future Challenges. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatopoulos, I.; et al. UAV-assisted seeding and monitoring of reforestation sites: A review. In Australian Geographer; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lysych, A.; et al. Design and Research Sowing Devices for Aerial Sowing of Forest Seeds with UAVs. Inventions 2021, 6, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; et al. Design and experiment of a precision strip seeding UAV for rice. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery, (in Chinese). 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; et al. Evaluation method of rowing performance for UAV rice seeding. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2023, 205, 107600. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Q.R.; et al. UAV-Based Precision Seed Dropping for Automated Reforestation. preprint 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; et al. Key parameters determination based on seed movement for UAV strip seeding. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, D.J. Criteria for the selection of stochastic models of particle trajectories in turbulent flows. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 1987, 180, 529–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.D.; Sawford, B.L. Review of Lagrangian stochastic models for trajectories in the turbulent atmosphere. Boundary-Layer Meteorology 1996, 78, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, D.J.; Wilson, J.D. History of Lagrangian stochastic models for turbulent dispersion. In AGU Geophysical Monograph; American Geophysical Union, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Emeis, S. Current issues in wind energy meteorology. Meteorological Applications 2014, 21, 803–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Villalobos, C.A.; et al. Analysis of the influence of the wind speed profile on wind power estimation. Energy Reports 2022, 8, 13056–13068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, G.Y. Two-Dimensional Measures of Accuracy in Navigational Systems. Technical report, U.S, 1987. Report; Department of Transportation. [Google Scholar]

- Spall, J.C.; Maryak, J.T. A Feasible Bayesian Estimator of Quantiles for Projectile Accuracy from Non-IID Data. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1992, 87, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, S.O. Mathematical Analysis of Random Noise. Bell System Technical Journal 1945, 24, 46–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakimenko, O.A. Statistical Analysis of Touchdown Error for Self-Guided Aerial Payload Delivery Systems. In Proceedings of the AIAA ADS, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; An, W. Assessing circular error probable when the errors are elliptical normal. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation 2012, 82, 565–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Ko, H.; Kim, S. Development and evaluation of an unmanned aerial vehicle seed-ball spreading system. Biosystems Engineering 2023, 226, 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, H. Field monitoring and wind tunnel study of wind effects on a long-span roof. Structural Control and Health Monitoring; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, S.B. Turbulent Flows; Cambridge University Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlenbeck, G.E.; Ornstein, L.S. On the Theory of the Brownian Motion. Physical Review 1930, 36, 823–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stull, R.B. An Introduction to Boundary Layer Meteorology; Springer: Dordrecht, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Khanjari, A.; Lundquist, J.K.; Pouragha, P. An analytical formulation for turbulence kinetic energy added by wind turbines based on LES. Wind Energy Science 2025, 10, 887–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, R.W.; McLain, T.W. Small Unmanned Aircraft: Theory and Practice; Princeton University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J.R. An Introduction to Error Analysis, 2 ed.; University Science Books, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Shalom, Y.; Li, X.R.; Kirubarajan, T. Estimation with Applications to Tracking and Navigation; Wiley, 2001. [Google Scholar]

-

Understanding GPS/GNSS: Principles and Applications, 3 ed.; Kaplan, E.D., Hegarty, C.J., Eds.; Artech House, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- van Diggelen, F. GPS accuracy: Lies, damn lies, and statistics. GPS World 1998, 9, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Rayleigh, Lord. On the resultant of a large number of vibrations of the same pitch and of arbitrary phase. Philosophical Magazine 1880, 10, 73–78. ser. 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, S.O. Mathematical analysis of random noise. Bell System Technical Journal 1945, 24, 46–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.K.; Alouini, M.S. Digital Communication over Fading Channels, 2 ed.; Wiley-IEEE Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, S.M.

Fundamentals of Statistical Signal Processing. In Detection Theory; Prentice Hall, 1998; Vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- White, F.M. Fluid Mechanics, 7 ed.; McGraw–Hill, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, S. Life in Moving Fluids, 2 ed.; Princeton Univ. Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J.R. Classical Mechanics; University Science Books, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, G.I. Diffusion by continuous movements. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society 1921, 20, 196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennekes, H.; Lumley, J.L. A First Course in Turbulence; MIT Press, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Sawford, B.L. Reynolds number effects in Lagrangian stochastic models of turbulent dispersion. Physics of Fluids A 1991, 3, 1577–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

5 m (orange): lower release, best precision, minimal wind exposure;

5 m (orange): lower release, best precision, minimal wind exposure; 10 m (green): nominal operating altitude;

10 m (green): nominal operating altitude; 15 m (red): higher release, more drift, degraded accuracy.

15 m (red): higher release, more drift, degraded accuracy. Low (2 m/s, green dashed)

Low (2 m/s, green dashed)

Nominal (current speed, solid green)

Nominal (current speed, solid green)

High (8 m/s, red dashed)

High (8 m/s, red dashed)

Green: excellent seeding accuracy

Green: excellent seeding accuracy

Orange: acceptable or good performance

Orange: acceptable or good performance

Red: degraded performance

Red: degraded performance