1. Introduction

Recently, Tourism is an important enabler of economic growth and a central subject in contemporary economic and environmental research, particularly in relation to sustainable development goals. In this context, tourism plays a pivotal role by stimulating economic activity, generating employment opportunities, and enhancing foreign trade [

1]. With more than one billion tourists traveling to an international destination every year, tourism sector accounted for approximately 10% of global GDP and supported more than 330 million jobs worldwide in 2023 [

2]. The latest projections by WTTC suggest the sector will contribute

$16 trillion in GDP by 2034 and total travel spend will reach

$14 trillion. For European counties, the sector’s contribution to global GDP totaled approximately €1.65 trillion, accounting for 11.1% of the total economy -surpassing pre-pandemic levels by 0.8% in 2024. In terms of employment, the sector supported nearly 23.53 million jobs in 2024, representing a significant portion of the workforce, with projections reaching 28.02 million by 2034 [

3]. International tourism also generated around 982.2 billion euros in terms of foreign exchange, equivalent to 6.1% of total exports. These statistics highlight tourism’s strategic role in driving of European economic growth, while also displaying its remarkable resilience and strong prospects for sustainable development in the coming years.

However, the increase of tourism activities, particularly those driven by investments in infrastructure and superstructure, can generate environmental problems that harm long-term ecological sustainability. Moreover, the nexus between economic advancement and tourism expansion has attracted much attention considerable scholarly attention across European countries, reflecting the complex relationship between economic prosperity and sustainable tourism development. According to European Environment Agency, the EU27’s accounted for roughly 5.9% of global CO₂ emissions, while the greenhouse gas emissions estimates at 894 million tonnes of CO2-equivalents in 2024. This situation is further complicated by significant waste generation across EU countries, resulting a pressure on ecosystems and challenges in environmental stewardship. As the environmental consequences of tourism have become more evident, academic and policy interest has increasingly removed toward examining waste generation and exploring how its management can be transformed into a source of benefit. The influx visitors usually causes a rise in different types of waste, including plastic, food waste, and single-use packaging, which local waste management systems often are not prepared to handle. In numerous destinations, the influx of visitors leads to substantially higher waste volumes compared to non-touristic regions. During peak tourism seasons, the rise in waste levels intensifies, often placing excessive pressure on local waste-management systems. Nevertheless, in a context marked by accelerating globalization, government tourism policies should focus on the positive outcomes of tourism of tourism while simultaneously reducing the negative effects. Considering these possible consequences, countries need to improve government efficiency and address the potential negative externalities associated with the tourism sector.

Whereas, it’s generally recognized that effective waste management plays a crucial role in country’s sustainable development, influencing everything from tourism development, economic growth, and the attraction of foreign investment. In this context, it is essential to examine whether waste management has a direct impact or a moderating role on tourism development and, consequently, on economic growth. Thus, a key objective of this study is to explore the link between waste management and economic development. This research focuses on the critical challenge policymakers’ face in the pursuit of continued economic growth while promoting a thriving tourism sector. Sustainable tourism development aims to harmonize economic prosperity with environmental protection and social well-being at this age of 21st century.

Nonetheless, there is an increasing awareness among researchers and decision-makers globally worldwide that the development of sustainable tourism in European countries depends largely on enhanced environmental quality and the implementation of effective waste-management practices. This implies that an effective waste management system is essential for tourism development to stimulate economic growth. The empirical studies on the Tourism-Waste generation nexus primarily follow two main approaches. The first estimates models by analyzing the elasticity between variables, including municipal solid waste and tourism development in a single equation, often without a strong underlying theoretical framework. The second approach applies traditional econometric tools, including unit root tests, cointegration, and causality analyses. This study distinguishes itself by employing the system GMM technique. To unlike the single-equation method, the system estimation can bring up the simultaneities among of the endogenous variables specified in the system and identify the likely two-way effects between them. To the best of our knowledge, none of the empirical studies have focused to investigating the nexus between waste management-Tourism-economic growth via the simultaneous equations models. Furthermore, incorporating trade openness and urbanization as key determinants of waste management offers a new perspective on how tourism contributes to sustainable waste management practices. To explore the underlying nexus, the present study focuses specifically on the context of the 27 European countries from 2010 to 2024. Specifically, the study seeks to analyze: a) how important economic, environmental, social, and globalization factors impact the development tourism in European countries ? ; b) how the interplay between tourism development and waste management contributes to overall economic performance ?; and c) how international tourism receipts serves as an indicator of sustainable tourism growth and its capacity to support funding for effective waste management strategies..

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides a critical review of the related literature;

Section 3 outlines the methodology and data source utilized for research;

Section 4 presents and discusses the empirical findings, while

Section 5 provides concluding remarks.

2. Literature Review

This study examines the link between tourism development, waste generation and economic growth. The review of literature is arranged into sections to provide a clear analytical structure. It analyzes the effects of tourism on advancement evaluates the environmental consequences of tourism development and explores the relationship between tourism activities and waste management. Researching the link between tourism-economic growth and the efficiency of waste systems is also carried out.

2.1. Tourism and Economic Growth

Sustainable tourism development continues to draw global interest. Tourism activity generates employment opportunities and income for local communities. Recent evidence indicates that global tourism growth, financial development, and other infrastructure indices have risen by 1% [

4]. Tourism has progressively evolved into the third-largest export industry globally, following food and automobile sectors. In recent years, international tourism generated a record

$1.9 trillion in export revenues, equivalent to about 6% of global exports.

The existing literature largely investigates the relationship between tourism development and economic growth by examining both unidirectional and bidirectional causal linkages between the two variables [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Some studies emphasize that tourism can directly drive economic growth by creating employment opportunities, generating income, and increasing foreign exchange earnings (unidirectional relationship). Conversely, others shows that economic growth itself can stimulate tourism development by improving infrastructure and raising demand for travel (reverse unidirectional). Several studies have confirmed a bidirectional relationship between tourism and economic growth in the short run. Moreover, research documents persistent bidirectional long-run causalities among carbon emissions, economic growth, and tourism [

7]. However, further empirical research is needed to strengthen the evidence on the tourism-economic growth nexus. Tourism development is widely recognized as a key driver of economic growth, influencing the economy through multiple channels, such as size enterprises [

10] (Regerson, 2008), innovation activities [

11], institutional quality [

9] and the accumulation of human capital [

4,

12,

13]. Specific information about international and domestic visitors plays a crucial role in calculating tourism’s economic impact. [

14] emphasize that tourism’s economic dimension is captured through indicators such as the scale and number of tourism businesses, their business operations, employment levels, and the wages of their employees.

2.2. Tourism and the Environment

The prevalence of environmental issues presents a growing concern to stakeholders worldwide. Researchers and policymakers aim to identify the main causes of these problems and to predict their future direction. As a result, there has been an increase in research aimed at identifying the determinants of environmental degradation. While the majority of these studies have examined the environmental effects of economic growth and energy use. However, few other studies considered tourism as one of the potential environmental determinants. Previous research commonly indicates that the environmental effects of tourism are usually measured using simple environmental indicators, such as CO₂ emissions [

15] or air pollution [

16].

A growing body of literature examines sustainable tourism, highlighting how tourism its dual potential to support and damage the environment. Several studies have investigated how promoting tourism influences pollutant emissions, concluding that it negatively impacts environmental quality [

4,

9,

17,

18,

19]. Tourism contributes to increased carbon emissions because tourists commonly use road, air, and sea transportation and consume a variety of goods and services, which can lead to a decline in environmental quality. In addition, tourism activities rely on various energy sources, including crude oil, natural gas, and coal. With the development of tourism economy, increased investments in infrastructure can further expose the natural environment to vulnerability. At the same time, although tourism can negatively impact the environment, there are also positive relationships between the tourism sector and the environment, which play a crucial role in advancing the objectives of sustainable development [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

2.3. Tourism and Waste Generation

Effective waste management plays a crucial role in the sustainable development of tourism. In this regard, tourist destinations increasingly face serious challenges related to visible plastic pollution, where solid waste generation has emerged as a primary issue for popular tourist attractions [

25]. Several studies have investigated the relationship between tourist flows and emissions, emphasizing that rising tourist arrivals in peak seasons correlate with high rates of waste generation. An increase in tourist arrivals is positively associated with higher levels of waste generation, creating substantial challenges for tourist cities, particularly with regard to waste disposal and littering. This situation is further due to widespread street food consumption, typically wrapped in single-use plastics, alongside miniature toiletries in hotel rooms and individual portions of butter or spreads at breakfast buffets. Moreover, the rising on-the-go lifestyle, particularly in select EU countries, has fueled a distinct waste stream dominated by biodegradable and compostable materials.

Previous studies have also highlighted the link between waste management practices and tourism development, while documenting the detrimental impact of waste accumulation on destination image [

26] and the association between the density of tourism-related businesses and environmental emissions [

27]. Tourist destinations express significant concerns regarding waste treatment capacity and the proportion of waste actually processed. To address these issues, specific indicators are commonly employed to monitor solid waste recycling rates and the performance of waste treatment services. Empirical evidence points to a declining trend in the generation of unsorted waste alongside a positive evolution in the collection of recyclable materials [

28]. Nevertheless, the implementation of effective waste management systems remains essential to prevent the intensification of environmental and social issues associated with tourism activities [

29]. Structural modeling approaches have pinpointed tourism as a key contributor to solid waste, establishing connections between municipal waste handling and insufficient disposal infrastructure [

30].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

This study is an attempt to analyse the connectedness of tourism development, waste generation and economic performance in 27 European countries from 2010-2024. Data were collected via Eurostat, the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), and the World Bank’s (World Development Indicators). The multivariate model for this research comprises: economic performance (GDP), measured by the real gross domestic product rate (%); tourism development (TOUR), represented by international tourist arrivals and tourism receipts as a percentage of GDP (%); waste generation, represented by the municipal waste recycling rate (%); per capita energy usage (E), measured in kg of oil; Urbanization (U,) indicated by the proportion of population residing in urban areas; physical capital stock in tourism (K), proxied by gross fixed capital formation in the tourism sector (in constant 2000 US dollars), and Trade openness (TO) evaluated as the total of exports and imports, as a percentage of GDP.

Table 1 presents details the descriptive statistics and correlation coefficient matrix of the variables. The standard deviations of most of the variables show huge variations, indicating wide dispersion from their means, except for energy consumption and physical capital variables, which are not too dispersed from their means. The pairwise correlation coefficients shown reveal that most variables are negative, except the waste generation variable, which is positively correlated with urbanisation and trade openness. In contrast, economic growth is negatively correlated with waste generation.

3.2. Econometric Model

This study aims to analyze the relationships between tourism development, waste generation and economic performance in 27 European countries during 2010-2024. These variables are treated as endogenous because tourism can affect outcomes while causing environmental impacts and in turn economic growth and waste handling can influence tourism trends. Given this endogeneity, applying single-equation regression techniques could result in biased and unreliable parameter estimates, thereby compromising thus the validity of the findings. To derive reliable estimates, this study utilizes a simultaneous equations (SE) approach to explore the interrelationships among tourism development, waste generation and economic growth. Following on previous literature, we develop a log-linear SE model that enables the examination simultaneously of both direct and indirect impacts among the three variables. Control variables, including trade openness and urbanization, are incorporated in the equations to account for institutional and macroeconomic heterogeneity across countries. The log-linear specification also helps mitigate heteroscedasticity and ensures consistency of the estimates. The empirical implementation of this model is carried out using System Generalized Method of Moments (System GMM) in Stata 17, which effectively addresses endogeneity, simultaneity, and unobserved country-specific effects.

Based on empirical studies [

6,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35], the interdependencies among tourism development, waste generation, and economic growth are modeled as follows:

Eq. (1) indicates that economic growth depends on tourism development, waste generation, energy consumption, urbanization and trade openness. Tourism, represented here by tourism receipts as a share of GDP, has been extensively acknowledged in the literature as a factor in economic growth [

4,

7,

36]. Since, it promotes job creation produces income and enhances service exports. At the same time, the production of waste can harm outcomes by raising waste disposal expenses harming the environment and diminishing the appeal of locations [

25,

29,

37]. Energy consumption, reflecting household energy needs, is also crucial in influencing economic dynamics [

18,

38]. Urbanization, which reflects the concentration of people and economic activities in cities, impacts production efficiency and the use of infrastructure. Meanwhile, trade openness promotes technology diffusion expands markets and generates foreign exchange revenue thereby affecting growth [

12,

39]. Based on growth theory [

40] and enhanced production function models domestic capital and labor are incorporated as further factors acknowledging that human and physical capital are crucial, for sustained economic growth [

41]. This specification allows for the evaluation of both the direct and indirect effects of tourism and waste on economic performance in a panel of European countries.

Eq. (2) aims to explore the factors driving tourism development. Tourism receipts as a percentage of GDP is used to measure tourism in this context. The economic activity in many European countries, including employment, foreign exchange earnings, and overall welfare, is significantly influenced by tourism [

6,

7,

36]. Based on findings from the tourism indicated by fixed capital formation within the tourism industry alongside the workforce engaged in tourism play a role, in the sector’s ability and quality of services provided [

7,

11]. Urbanization, reflecting the concentration of economic activity and infrastructure development, and trade openness, facilitating cross-border mobility and market integration, are additional macroeconomic factors affecting tourism [

12,

39]. This specification allows capturing both supply- and demand-side determinants of tourism while controlling for country-specific characteristics that may influence the tourism sector in a panel of European countries.-driven growth literature, the extent of tourism is probably shaped by the broader economic context, indicated by GDP growth, which influences both domestic and global demand, for tourism services [

42,

43].

Equation (3) analyzes waste production as dependent on expansion tourism progress, energy use, urban growth and education. Waste production, quantified in kilograms per person or, by the recycling percentage serves as an environmental metric shaped by economic and social aspects [

25,

37,

44]. Environmental degradation studies suggest that economic expansion usually raises waste output in development phases because of greater consumption and industrial activities whereas in later phases, enhanced technology and heightened environmental consciousness can lower waste per individual [

33,

45]. Tourism directly adds to waste creation since more tourists lead to municipal solid waste and the growth of tourism facilities can further intensify environmental strain [

29,

46]. Energy usage, serving as an indicator of both household operations intensifies waste generation [

18,

38]. Urbanization, which indicates the proportion of people residing in areas places extra pressure, on waste management facilities and infrastructure especially in heavily populated locations [

47]. Education is included as a determinant to capture the population’s environmental awareness, as higher educational attainment is often associated with more sustainable waste management practices and recycling behavior [

24,

48]. This specification allows for an integrated assessment of the socio-economic and environmental drivers of waste generation across European countries, providing a comprehensive understanding of the interactions between tourism, economic activity, and environmental quality.

3.3. The Estimation Method

This study employs the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) developed by Arellano and Bond [

49] to estimate the dynamic interrelationships among tourism development, waste generation, and economic growth. The GMM framework is particularly appropriate in this context for correcting unobserved country heterogeneity, omitted variable bias, measurement error, and potential endogeneity which frequently impact growth estimation [

50].

Specifically, the system GMM estimator combines equations in both first differences and levels, thereby controlling for time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity and mitigating biases arising from omitted variables or measurement errors. Endogeneity of explanatory variables is addressed through internal instruments: lagged levels of the regressors serve as instruments for the differenced equations, while lagged differences are used as instruments for the level equations. This dual-equation approach, as proposed by Arellano and Bover [

51], improves efficiency and reduces potential finite-sample bias compared to the standard difference GMM. By applying system GMM, the study captures the simultaneous, dynamic relationships among the key variables while providing robust and consistent parameter estimates in the context of a panel of European countries over the period 2010-2024.

4. Results

The diagnostic statistics reported for the three estimated models confirm the overall reliability of the System GMM results. The AR(1) test shows the expected first-order serial correlation, while the AR(2) statistic indicates no evidence of second-order correlation, supporting the consistency of the moment conditions. The Sargan test suggests that the set of instruments is globally valid, and the Hansen test confirms the absence of instrument over identification problems. Taken together, these diagnostics validate the robustness of our dynamic panel results. Based on the model specification as indicted in Equations (1), (2) and (3), the empirical results are presented in

Table 2.

Regarding Eq. (1) The findings attest to the influence of tourism and environmental variables on economic outcomes, within the 27 European nations. The lagged GDP shows a statistically significant impact (coefficient = -0.446, p < 0.01) indicating possible adjustment mechanisms in the growth trajectory. Tourism development exhibits a positive influence, on economic performance with an elasticity of 1.501 (p < 0.01) aligning with previous research emphasizing tourisms role in promoting growth [

48,

52,

53]. Waste management, measured by recycling rates is positively linked to growth (coefficient = 0.308 p < 0.05) suggesting that enhanced environmental practices contribute to economic development [

54]. Trade openness also has an impact (coefficient = 0.059, p < 0.05) whereas energy consumption shows a negative influence (coefficient = -2.02 p < 0.05) indicating that energy inefficiency could impede growth. Urbanization is not significant (coefficient = -0.127) and the intercept is highly significant (26.452, p < 0.01). In general, these findings emphasize the importance of tourism and environmental management, in enhancing economic performance while pointing out the possible drawbacks of energy consumption. Regarding Eq. (2) Tourism growth is notably affected by its value (coefficient = 0.856 p < 0.01) per capita GDP (0.428 p < 0.01) and the capital stock within the tourism industry (0.392, p < 0.01) whereas recycling shows a slight yet negative influence (, -0.041 p < 0.05). Urbanization has a positive effect (0.027, p < 0.1) while trade openness is statistically non-significant (0.0007). These results indicate that economic performance and physical capital accumulation are major determinants of tourism growth, consistent with prior empirical studies [

48,

52,

54]. For Eq. (3), waste generation is largely driven by its own lag (0.856, p < 0.01), while tourism development has a significant negative effect (-0.287, p < 0.01), reflecting the effectiveness of tourism-related environmental policies in certain regions. GDP has a modest positive impact (0.034, p < 0.1), whereas energy consumption has a negative effect (-0.733, p < 0.05). Urbanization and trade openness show positive coefficients (0.042 and 0.013, p < 0.1), indicating that more urbanized and open economies tend to generate more waste. These findings are in line with previous studies linking economic growth, tourism, and waste generation [

25,

34,

53].

To gain an understanding of the relationship between our key variables, the Dumitrescu and Hurlin Granger non-causality tests [

55] were conducted with outcomes presented in

Table 3. The results reveal the existence of both one-way and two-way links among the variables investigated. In particular a bidirectional association is evident between tourism and GDP, waste generation, and energy consumption. Similarly, there is a bidirectional association between waste generation and energy consumption. Finally, a unidirectional causality relationship found between waste generation to economic growth.

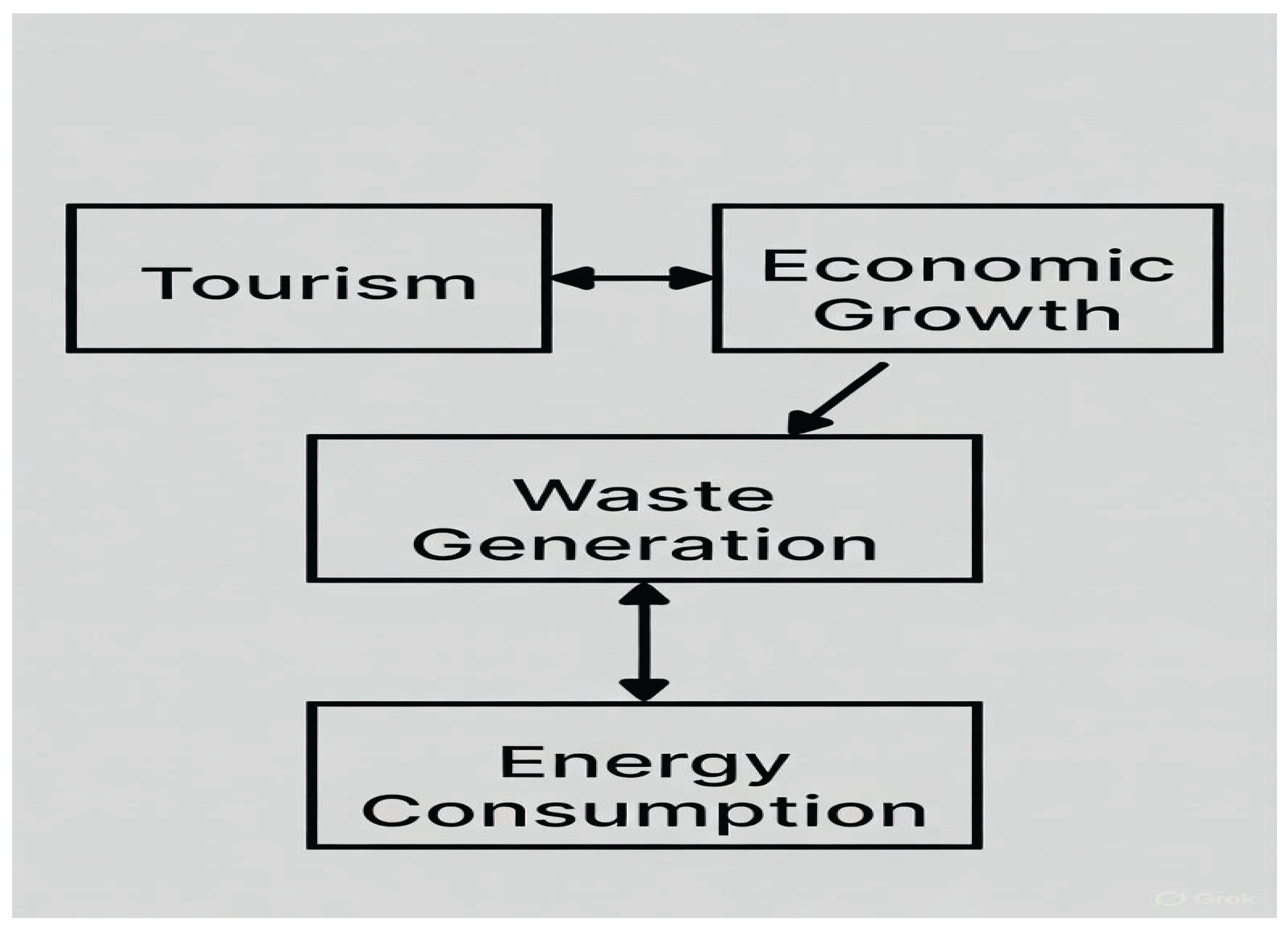

Figure 1 presents an overview of the causality test outcomes for 27 nations. Three main findings appear from the results. First, there is a bidirectional causality between economic growth and tourism development. A rise in GDP, per capita promotes tourism by increasing income and expenditure while tourism growth subsequently aids progress by generating employment attracting investments and expanding service exports. This outcome aligns with studies [

48,

52,

54]. Secondly, there is a bidirectional relationship between tourism and waste generation. A rise in tourism leads to waste production highlighting the environmental impacts associated with tourism expansion. Conversely improved waste management practices, including heightened recycling activities, typically aid in mitigating the environmental impacts of tourism. These findings are consistent with the conclusions of [

25,

53] who emphasize that tourism growth, without controls can exacerbate waste management issues. In summary, economic performance directly influences waste generation in one direction. Although economic growth usually increases waste generation due to consumption, effective waste management strategies and recycling programs can mitigate these environmental impacts without compromising economic growth. This emphasizes the need to align tourism with sustainable development to ensure long-term economic and ecological equilibrium. Overall, the results demonstrate strong interconnections between tourism development, waste management, and economic growth, recommending that European countries implement strategies to promote sustainable tourism (ecotourism) and preserve the environment.

5. Conclusion

This study examines the interrelationships between tourism development, waste generation, and economic performance for a panel of 27 European countries over the period 2010-2024, using simultaneous equations and System GMM estimations. Although research on economics and tourism is expanding, limited attention has been given to the causal relationships, between tourism, economic development and waste generation within a combined analytical approach. This research suggested three models: (i) GDP explained by tourism, waste production, energy use, urban development and trade openness; (ii) tourism explained by GDP, recycling, capital, development and trade openness; and (iii) recycling explained by GDP, tourism, energy use, urban development and trade openness.

Our results emphasize key interactions. Firstly, tourism significantly and positively drives growth while a rising GDP also enhances tourism indicating a two-way connection. Secondly, tourism growth and energy use lead, to increased waste production. Recycling reduces environmental harm. Thirdly, greater GDP encourages recycling implying that economic development can support sustainability when suitable policies exist. The causality examination using Dumitrescu-Hurlin tests indicates two-way influences between tourism and GDP and between GDP and recycling whereas one-way influences are founded from tourism to waste production and from energy use to recycling. These findings highlight the relationships among economic growth tourism activities and environmental impacts, in European nations.

Policy implications for our findings show that tourism development is one of the silver bullet for revering environmental degradation in European countries. Countries in these income groups should prioritize tourism development measures and address environmental issues in their development agendas. Nonetheless, the European countries should promote recycling and energy efficiency, more innovative, and environmentally friendly technology, particularity in the tourism sector. Specifically, achieving Sustainable Development Goal-13 requires restructuring the tourism industry around sustainability, thereby curbing its contributions to climate change, overexploitation of natural resources and reliance on fossil fuel-based energy consumption.

References

- Roy, M.; Medhekar, A. Tourism-led growth hypothesis: A global perspective bibliometric analysis. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2025, 30, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Tourism. World Tourism Highlights 2023; United Nations World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- World Travel; Tourism Council (WTTC). Travel & Tourism Economic Impact Report 2024; WTTC: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Liu, L.; Pan, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B. Tourism and economic growth: The role of institutional quality. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 2025, 98, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilen, M.; Yilanci, V.; Eryüzlü, H. Tourism development and economic growth: Panel causality analysis in the frequency domain. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuković, D.B.; Maiti, M.; Petrović, M.D. Tourism employment and economic growth: Dynamic panel threshold analysis. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algahtani, R.A. Tourism growth, economic development, and environmental sustainability in Saudi Arabia. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2025, 12, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qodirov, A.; Urakova, D.; Amonov, M.; Masharipova, M.; Ibadullaev, E.; Xolmurotov, F.; Matkarimov, F. The dynamics of tourism, economic growth, and CO₂ emissions in Uzbekistan: An ARDL approach. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2024, 14, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Cheablam, O. Sustainable tourism and its environmental and economic impacts: Fresh evidence from major tourism hubs. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, C.M. Shared growth and tourism small enterprise development in South Africa. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2015, 33, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.K.; Natoli, R.; Divisekera, S. Innovation and productivity in tourism small and medium enterprises: A longitudinal study. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 38, 100804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wei, M.; Wang, N.; Chen, Q. The impact of human capital and tourism industry agglomeration on China’s tourism eco-efficiency. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L. Productivity, destination performance, and stakeholder well-being. Tour. Hosp. 2022, 3, 618–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melián-González, S.; Bulchand-Gidumal, J. Employment in tourism: The jaws of the snake in the hotel industry. Tour. Manag. 2020, 80, 104123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, Q.B.; Shah, S.N.; Iqbal, N.; et al. Impact of tourism development upon environmental sustainability: A suggested framework for sustainable ecotourism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 5917–5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sáenz-de-Miera, O.; Rosselló, J. Modeling tourism impacts on air pollution: The case study of PM10 in Mallorca. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, C.; Arif, M.; Shehzad, K.; Ahmad, M.; Oláh, J. Modeling the dynamic linkage between tourism development, technological innovation, urbanization, and environmental quality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fafurida, F.; Solihah, D.M.; Marpaung, G.N. Tourism-induced environmental degradation in ASEAN countries. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2025, 15, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramati, S.R.; Alam, M.S.; Chen, C.-F. The effects of tourism on economic growth and CO₂ emissions. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 712–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.P.; Thanh, S.D.; Nguyen, B. Economic uncertainty and tourism consumption. Tour. Econ. 2020, 28, 920–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, F.; Wei, L.; Asif, M.; Haq, M.Z.U.; Rehman, H.U. The contribution of sustainable tourism to economic growth and employment in Pakistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannat, A.; Islam, M.M.; Aruga, K. Interrelationship of economic, environmental, and social factors with tourism growth in G7 countries. Sustain. Futures 2025, 9, 100483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başarir, Ç.; Çakir, Y.N. Causal interactions between CO₂ emissions, financial development, energy, and tourism. Asian Econ. Financ. Rev. 2015, 5, 1227–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsalobre-Lorente, D.; Driha, O.M.; Shahbaz, M.; Sinha, A. The effects of tourism and globalization on environmental degradation. MPRA Pap. 2020, 100092. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Li, T.; Li, L.; Liu, Q. A DPSIR–Bayesian network approach for tourism ecological security. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, P.; Sharma, R.; Sarkar, P.; Sarkar, S. Waste and tourism: Drivers of sustainable waste management practices. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2025, 12, 102290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koliotasi, A.-S.; Abeliotis, K.; Tsartas, P.-G. Understanding the impact of waste management on a destination’s image. Tour. Hosp. 2023, 4, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbulú, I.; Rey-Maquieira, J.; Sastre, F. The impact of tourism and seasonality on municipal solid waste generation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mdoda, S.S.; Dube, K.; Montsiemang, T. Tackling water and waste management challenges. Water 2024, 16, 3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S.; Goswami, S. Tourism-induced challenges in municipal solid waste management. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2016, 35, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Brahmasrene, T. Investigating the influence of tourism on economic growth and carbon emissions. Tour. Manag. 2013, 38, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.F.; Abosedra, S. Tourism-led growth hypothesis: Evidence from Lebanon. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, I. A literature survey on the energy–growth nexus. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sun, T.; Lu, Y. COVID-19 pandemic and tourists’ risk perceptions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbulú, I.; Lozano, J.; Rey-Maquieira, J. Tourism activity and waste generation dynamics. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 406, 136824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahni, H.; Nsiah, C.; Fayissa, B. Tourism receipts and African economic growth. Tour. Econ. 2021, 27, 915–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.; Can, M.; Paramati, S.R.; Fang, J.; Wu, W. Tourism quality, economic development, and the environment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, M.C. Does tourism development promote economic growth? Econ. Model. 2013, 33, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solow, R.M. A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Q. J. Econ. 1956, 70, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mello, L.R. Foreign direct investment and growth. J. Dev. Stud. 1997, 34, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, G.; Cenciarelli, V.G.; Allegrini, M. Tourism’s impacts on the costs of municipal solid waste collection. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 177, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, D.I. The rise and fall of the Environmental Kuznets Curve. World Dev. 2004, 32, 1419–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, R.; Irsyad, M.; Nepal, S.K. Tourist arrivals, energy consumption, and emissions. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safiei, S.; Salim, R.A. Renewable and non-renewable energy consumption and CO₂ emissions. Energy Policy 2014, 66, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katircioglu, S.T. Testing the tourism-induced EKC hypothesis. Econ. Model. 2014, 41, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalá-Ordóñez, A.; Alcalá-Olid, F.; Olivera, M. The nexus between tourism, economic growth, and environmental pollution at a regional level in Spain: A new CS-ARDL approach. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2024, 16, 310–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, R.V.; Damásio, B. Exploring the linear and non-linear effects of tourism on economic growth in the Cabo Verde Islands: Evidence from the ARDL and NARDL models. Curr. Issues Tour. 2025, 28, 3393–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajahat, A.; Sadiq, F.; Kumail, T.; Li, H.; Zahid, M.; Sohag, K. A cointegration analysis of structural change, international tourism and energy consumption on CO₂ emission in Pakistan. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 3001–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M.; Bond, S. Some tests of specification for panel data. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1991, 58, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, R.; Bond, S. Initial conditions and moment restrictions. J. Econom 1998, 87, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M.; Bover, O. Another look at instrumental variable estimation. J. Econom 1995, 68, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetanah, B. Dynamic economic impact of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vita, G.; Kyaw, K.S. Tourism development and growth. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 60, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, A.; Martinho, G.; Chang, N.-B. Solid waste management in European countries. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 1033–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumitrescu, E.I.; Hurlin, C. Testing for Granger non-causality in heterogeneous panels. Econ. Model. 2012, 29, 1450–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).