Submitted:

24 December 2025

Posted:

24 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Epidemiology of Myocardial Involvement in COVID-19

4. Histology of COVID-19 Myocarditis

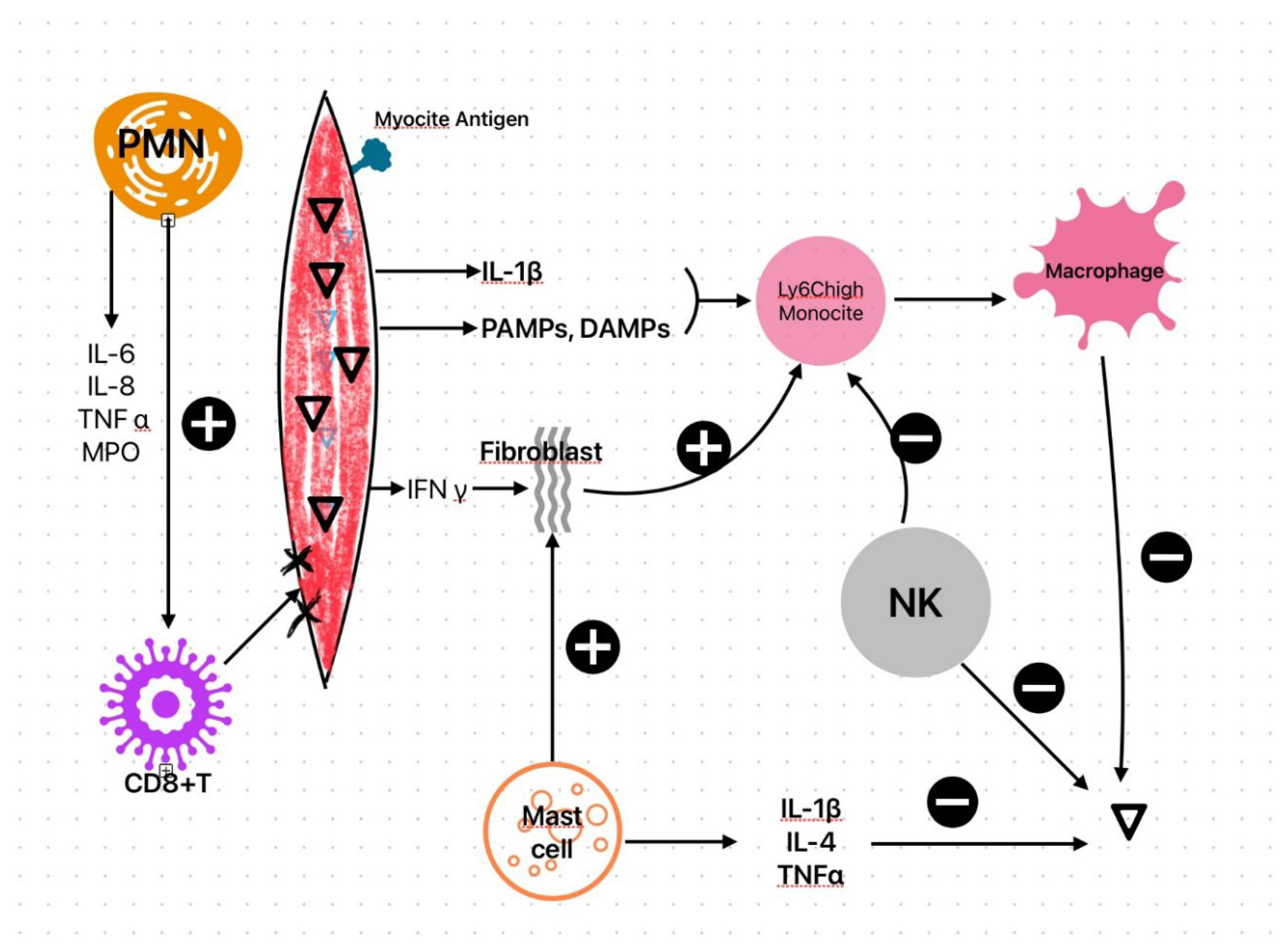

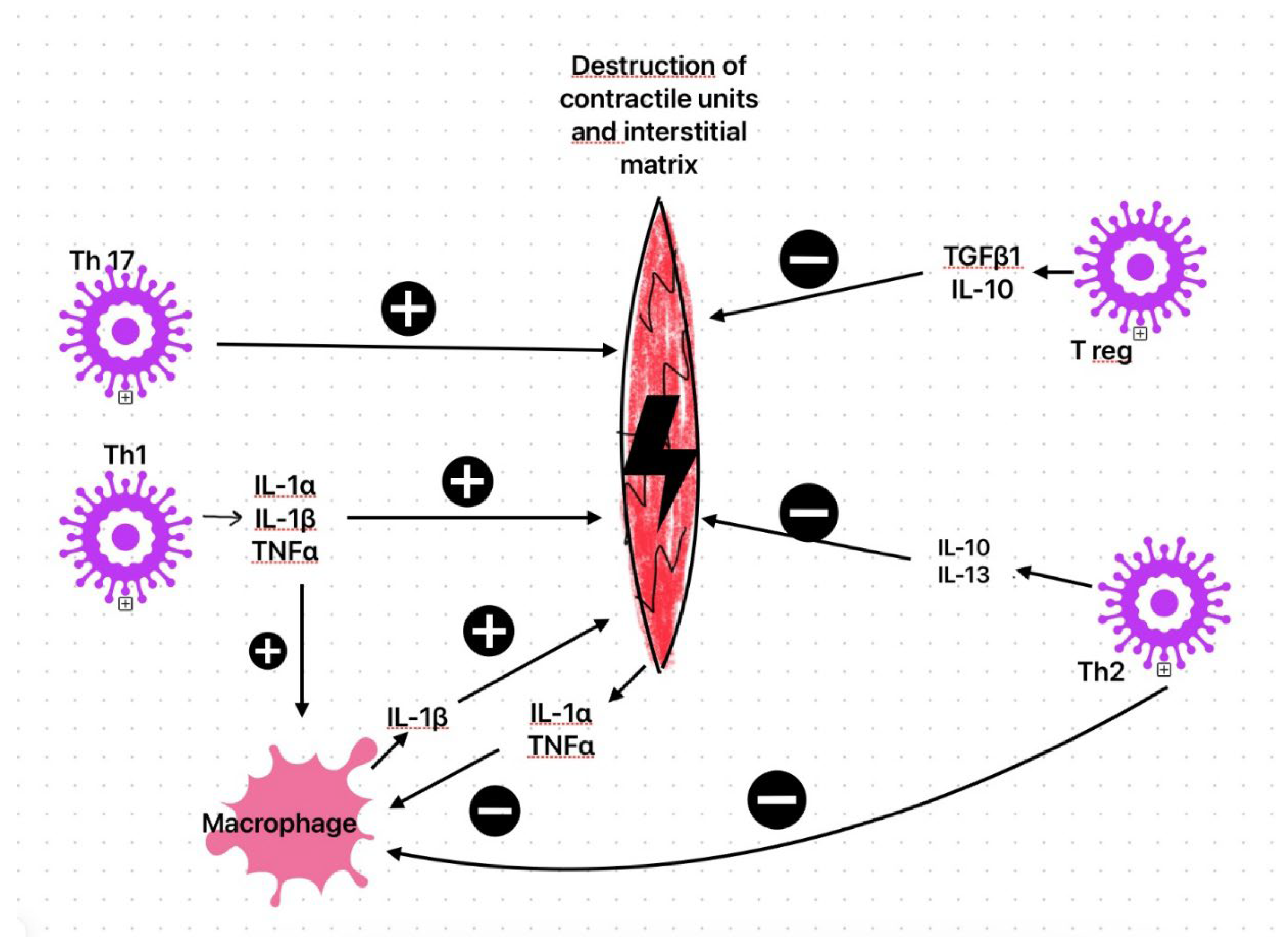

5. Myocarditis Pathophysiology

6. Vascular Involvement in COVID-19

7. Acute Myocarditis After Vaccination

- An aberrant innate immune activation by the vaccine platform (mRNA and lipid nanoparticle components) that triggers myocardial inflammation in predisposed individuals. The higher prevalence of myocarditis in young males may be explained by higher levels of androgens, especially testosterone, which can enhance the pro-inflammatory response by Th1 lymphocytes and pro-inflammatory cytokine production [162,163]. The lipid nanoparticles may act as adjuvants, enhancing immune responses, but could potentially contribute to excessive inflammatory reactions in susceptible individuals[164].

- An adaptive immune response in which anti-spike antibodies or spike-directed T cells cross-react with cardiac antigens. This represents the molecular mimicry hypothesis and was described by Nunez et al. [165]. The molecular mimicry is associated with a cross-reaction of antibodies against the spike protein with self-antigens such as heavy chains of myosin or troponin C1.[166]

- A hyper-inflammatory recall response after repeat antigen exposure, consistent with a short latency and robust anamnestic immunity.

8. Clinical Manifestations of Cardiac Involvement

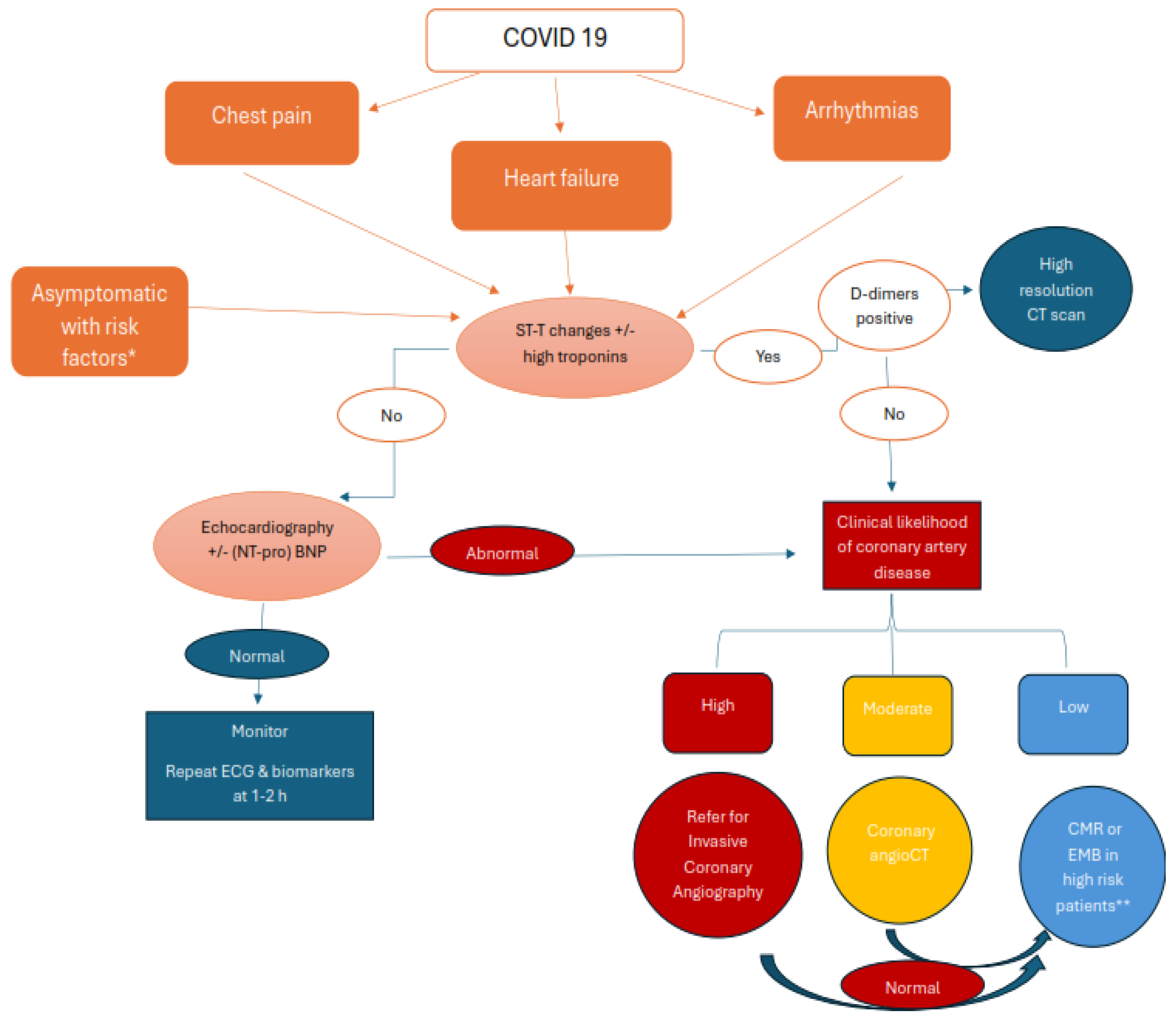

9. Diagnosis of Cardiac Involvement

10. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siripanthong, B.; Nazarian, S.; Muser, D.; Deo, R.; Santangeli, P.; Khanji, M.Y.; Cooper, L.T.; Chahal, C.A.A. Recognizing COVID-19-Related Myocarditis: The Possible Pathophysiology and Proposed Guideline for Diagnosis and Management. Heart Rhythm 2020, 17, 1463–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oster, M.E.; Shay, D.K.; Su, J.R.; Gee, J.; Creech, C.B.; Broder, K.R.; Edwards, K.; Soslow, J.H.; Dendy, J.M.; Schlaudecker, E.; et al. Myocarditis Cases Reported After mRNA-Based COVID-19 Vaccination in the US From December 2020 to August 2021. JAMA 2022, 327, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patone, M.; Mei, X.W.; Handunnetthi, L.; Dixon, S.; Zaccardi, F.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Watkinson, P.; Khunti, K.; Harnden, A.; Coupland, C.A.C.; et al. Risk of Myocarditis After Sequential Doses of COVID-19 Vaccine and SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Age and Sex. Circulation 2022, 146, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrini, D.; Kawakami, R.; Guagliumi, G.; Sakamoto, A.; Kawai, K.; Gianatti, A.; Nasr, A.; Kutys, R.; Guo, L.; Cornelissen, A.; et al. Microthrombi as a Major Cause of Cardiac Injury in COVID-19: A Pathologic Study. Circulation 2021, 143, 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oster, M.E.; Shay, D.K.; Su, J.R.; Gee, J.; Creech, C.B.; Broder, K.R.; Edwards, K.; Soslow, J.H.; Dendy, J.M.; Schlaudecker, E.; et al. Myocarditis Cases Reported After mRNA-Based COVID-19 Vaccination in the US From December 2020 to August 2021. JAMA 2022, 327, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halushka, M.K.; Vander Heide, R.S. Myocarditis Is Rare in COVID-19 Autopsies: Cardiovascular Findings across 277 Postmortem Examinations. Cardiovasc Pathol 2021, 50, 107300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, X.; Chen, M.; Feng, Y.; Xiong, C. The ACE2 Expression in Human Heart Indicates New Potential Mechanism of Heart Injury among Patients Infected with SARS-CoV-2. Cardiovasc Res 2020, 116, 1097–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhao, P.; Tang, D.; Zhu, T.; Han, R.; Zhan, C.; Liu, W.; Zeng, H.; Tao, Q.; Xia, L. Cardiac Involvement in Patients Recovered From COVID-2019 Identified Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2020, 13, 2330–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Xu, E.; Bowe, B.; Al-Aly, Z. Long-Term Cardiovascular Outcomes of COVID-19. Nat Med 2022, 28, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC ACIP Evidence to Recommendations for Use of Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/acip/evidence-to-recommendations/bla-covid-19-moderna-etr.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Golpour, A.; Patriki, D.; Hanson, P.J.; McManus, B.; Heidecker, B. Epidemiological Impact of Myocarditis. J Clin Med 2021, 10, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanuri, S.; Aedma, S.; Naik, A.; Kumar, P.; Mahajan, P.; Gupta, R.; Garg, J.; Thurugam, M.; Elbey, A.; Varadarajan, P.; et al. Pathophysiology of Myocarditis: State-of-the-Art Review Corresponding Author. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, G.; Luo, H.; Qiu, Y.; Yang, D.; McManus, B. Myocarditis. Circ Res 2016, 118, 496–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelle, M.C.; Zaffina, I.; Lucà, S.; Forte, V.; Trapanese, V.; Melina, M.; Giofrè, F.; Arturi, F. Endothelial Dysfunction in COVID-19: Potential Mechanisms and Possible Therapeutic Options. Life (Basel) 2022, 12, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehmer, T.K.; Kompaniyets, L.; Lavery, A.M.; Hsu, J.; Ko, J.Y.; Yusuf, H.; Romano, S.D.; Gundlapalli, A.V.; Oster, M.E.; Harris, A.M. Association Between COVID-19 and Myocarditis Using Hospital-Based Administrative Data - United States, March 2020-January 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021, 70, 1228–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluckman, T.J.; Bhave, N.M.; Allen, L.A.; Chung, E.H.; Spatz, E.S.; Ammirati, E.; Baggish, A.L.; Bozkurt, B.; Cornwell, W.K.; et al.; Writing Committee 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Cardiovascular Sequelae of COVID-19 in Adults: Myocarditis and Other Myocardial Involvement, Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection, and Return to Play: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022, 79, 1717–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammirati, E.; Lupi, L.; Palazzini, M.; Hendren, N.S.; Grodin, J.L.; Cannistraci, C.V.; Schmidt, M.; Hekimian, G.; Peretto, G.; Bochaton, T.; et al. Prevalence, Characteristics, and Outcomes of COVID-19-Associated Acute Myocarditis. Circulation 2022, 145, 1123–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Liu, X.; Su, Y.; Ma, J.; Hong, K. Prevalence and Impact of Cardiac Injury on COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Cardiol 2020, 44, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuin, M.; Rigatelli, G.; Battisti, V.; Costola, G.; Roncon, L.; Bilato, C. Increased Risk of Acute Myocardial Infarction after COVID-19 Recovery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Cardiol 2023, 372, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsoularis, I.; Fonseca-Rodríguez, O.; Farrington, P.; Lindmark, K.; Fors Connolly, A.-M. Risk of Acute Myocardial Infarction and Ischaemic Stroke Following COVID-19 in Sweden: A Self-Controlled Case Series and Matched Cohort Study. Lancet 2021, 398, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, R.C.; Garg, S.; George, M.G.; Patel, K.; Jackson, S.L.; Loustalot, F.; Wortham, J.M.; Taylor, C.A.; Whitaker, M.; Reingold, A.; et al. Acute Cardiac Events During COVID-19-Associated Hospitalizations. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023, 81, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, C.; Leone, O.; Rizzo, S.; De Gaspari, M.; van der Wal, A.C.; Aubry, M.-C.; Bois, M.C.; Lin, P.T.; Maleszewski, J.J.; Stone, J.R. Pathological Features of COVID-19-Associated Myocardial Injury: A Multicentre Cardiovascular Pathology Study. Eur Heart J 2020, 41, 3827–3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Deswal, A.; Khalid, U. COVID-19 Myocarditis and Long-Term Heart Failure Sequelae. Curr Opin Cardiol 2021, 36, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carsana, L.; Sonzogni, A.; Nasr, A.; Rossi, R.S.; Pellegrinelli, A.; Zerbi, P.; Rech, R.; Colombo, R.; Antinori, S.; Corbellino, M.; et al. Pulmonary Post-Mortem Findings in a Series of COVID-19 Cases from Northern Italy: A Two-Centre Descriptive Study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020, 20, 1135–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Zhao, W.; Feng, R.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Peng, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Luo, J.; et al. The Pathological Autopsy of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-2019) in China: A Review. Pathog Dis 2020, 78, ftaa026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaller, T.; Hirschbühl, K.; Burkhardt, K.; Braun, G.; Trepel, M.; Märkl, B.; Claus, R. Postmortem Examination of Patients With COVID-19. JAMA 2020, 323, 2518–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearse, M.; Hung, Y.P.; Krauson, A.J.; Bonanno, L.; Boyraz, B.; Harris, C.K.; Helland, T.L.; Hilburn, C.F.; Hutchison, B.; Jobbagy, S.; et al. Factors Associated with Myocardial SARS-CoV-2 Infection, Myocarditis, and Cardiac Inflammation in Patients with COVID-19. Mod Pathol 2021, 34, 1345–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otifi, H.M.; Adiga, B.K. Endothelial Dysfunction in Covid-19 Infection. Am J Med Sci 2022, 363, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.E.; Akmatbekov, A.; Harbert, J.L.; Li, G.; Quincy Brown, J.; Vander Heide, R.S. Pulmonary and Cardiac Pathology in African American Patients with COVID-19: An Autopsy Series from New Orleans. Lancet Respir Med 2020, 8, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.H.; Li, T.Y.; He, Z.C.; Ping, Y.F.; Liu, H.W.; Yu, S.C.; Mou, H.M.; Wang, L.H.; Zhang, H.R.; Fu, W.J.; et al. A pathological report of three COVID-19 cases by minimal invasive autopsies. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi 2020, 49, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, D.; Fitzek, A.; Bräuninger, H.; Aleshcheva, G.; Edler, C.; Meissner, K.; Scherschel, K.; Kirchhof, P.; Escher, F.; Schultheiss, H.-P.; et al. Association of Cardiac Infection With SARS-CoV-2 in Confirmed COVID-19 Autopsy Cases. JAMA Cardiol 2020, 5, 1281–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Xu, J.; Yu, C.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Lin, D.; Yan, C.; Guo, M.; Li, J.; He, P.; et al. Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 Colonization and High Expression of Inflammatory Factors in Cardiac Tissue 6 Months after COVID-19 Recovery: A Prospective Cohort Study. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2024, 14, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardiac SARS-CoV-2 Infection, Involvement of Cytokines in Postmortem Immunohistochemical Study. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4418/14/8/787 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Yu, B.; Wu, Y.; Song, X.; Liu, G.; Wang, F.; Zhang, F.; Liang, B. Possible Mechanisms of SARS-CoV2-Mediated Myocardial Injury. Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications 2023, 8, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, S.A.; Gauntt, C.J.; Sakkinen, P. Enteroviruses and Myocarditis: Viral Pathogenesis through Replication, Cytokine Induction, and Immunopathogenicity. Adv Virus Res 1998, 51, 35–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkiel, S.; Kuan, A.P.; Diamond, B. Autoimmunity in Heart Disease: Mechanisms and Genetic Susceptibility. Mol Med Today 1996, 2, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sozzi, F.B.; Gherbesi, E.; Faggiano, A.; Gnan, E.; Maruccio, A.; Schiavone, M.; Iacuzio, L.; Carugo, S. Viral Myocarditis: Classification, Diagnosis, and Clinical Implications. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9, 908663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollack, A.; Kontorovich, A.R.; Fuster, V.; Dec, G.W. Viral Myocarditis--Diagnosis, Treatment Options, and Current Controversies. Nat Rev Cardiol 2015, 12, 670–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisch, B. Cardio-Immunology of Myocarditis: Focus on Immune Mechanisms and Treatment Options. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heymans, S.; Eriksson, U.; Lehtonen, J.; Cooper, L.T. The Quest for New Approaches in Myocarditis and Inflammatory Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016, 68, 2348–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschöpe, C.; Ammirati, E.; Bozkurt, B.; Caforio, A.L.P.; Cooper, L.T.; Felix, S.B.; Hare, J.M.; Heidecker, B.; Heymans, S.; Hübner, N.; et al. Myocarditis and Inflammatory Cardiomyopathy: Current Evidence and Future Directions. Nat Rev Cardiol 2021, 18, 169–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuschner, F.; Rauch, P.J.; Ueno, T.; Gorbatov, R.; Marinelli, B.; Lee, W.W.; Dutta, P.; Wei, Y.; Robbins, C.; Iwamoto, Y.; et al. Rapid Monocyte Kinetics in Acute Myocardial Infarction Are Sustained by Extramedullary Monocytopoiesis. J Exp Med 2012, 209, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruestle, K.; Hackner, K.; Kreye, G.; Heidecker, B. Autoimmunity in Acute Myocarditis: How Immunopathogenesis Steers New Directions for Diagnosis and Treatment. Curr Cardiol Rep 2020, 22, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, H.; Hara, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Miyamoto, T.; Kinoshita, M.; Yamada, T.; Uchiyama, K.; Matsumori, A. Mast Cells Play a Critical Role in the Pathogenesis of Viral Myocarditis. Circulation 2008, 118, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckbach, L.T.; Grabmaier, U.; Uhl, A.; Gess, S.; Boehm, F.; Zehrer, A.; Pick, R.; Salvermoser, M.; Czermak, T.; Pircher, J.; et al. Midkine Drives Cardiac Inflammation by Promoting Neutrophil Trafficking and NETosis in Myocarditis. J Exp Med 2019, 216, 350–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivadeneyra, L.; Charó, N.; Kviatcovsky, D.; de la Barrera, S.; Gómez, R.M.; Schattner, M. Role of Neutrophils in CVB3 Infection and Viral Myocarditis. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2018, 125, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabie, N.; Hsieh, D.T.; Buono, C.; Westrich, J.R.; Allen, J.A.; Pang, H.; Stavrakis, G.; Lichtman, A.H. Neutrophils Sustain Pathogenic CD8+ T Cell Responses in the Heart. Am J Pathol 2003, 163, 2413–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, S.; Rose, N.R.; Čiháková, D. Natural Killer Cells in Inflammatory Heart Disease. Clin Immunol 2017, 175, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.P.; Mason, J.W. Advances in the Understanding of Myocarditis. Circulation 2001, 104, 1076–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Luca, G.; Cavalli, G.; Campochiaro, C.; Tresoldi, M.; Dagna, L. Myocarditis: An Interleukin-1-Mediated Disease? Front. Immunol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vdovenko, D.; Eriksson, U. Regulatory Role of CD4+ T Cells in Myocarditis. J Immunol Res 2018, 2018, 4396351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J.M.; Cooper, L.T.; Kem, D.C.; Stavrakis, S.; Kosanke, S.D.; Shevach, E.M.; Fairweather, D.; Stoner, J.A.; Cox, C.J.; Cunningham, M.W. Cardiac Myosin-Th17 Responses Promote Heart Failure in Human Myocarditis. JCI Insight 2016, 1, e85851, 85851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, N.R. Critical Cytokine Pathways to Cardiac Inflammation. J Interferon Cytokine Res 2011, 31, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumori, A. Cytokines in Myocarditis and Cardiomyopathies. Curr Opin Cardiol 1996, 11, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, J.W. Myocarditis and Dilated Cardiomyopathy: An Inflammatory Link. Cardiovasc Res 2003, 60, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, C. Viral Myocarditis. Yale J Biol Med 2024, 97, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldeviano, G.C.; Barin, J.G.; Talor, M.V.; Srinivasan, S.; Bedja, D.; Zheng, D.; Gabrielson, K.; Iwakura, Y.; Rose, N.R.; Cihakova, D. Interleukin-17A Is Dispensable for Myocarditis but Essential for the Progression to Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Circ Res 2010, 106, 1646–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamm, C.; Fairweather, D.; Cooper, L.T. Republished: Pathogenesis and Diagnosis of Myocarditis. Postgrad Med J 2012, 88, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Hoogen, P.; van den Akker, F.; Deddens, J.C.; Sluijter, J.P.G. Heart Failure in Chronic Myocarditis: A Role for microRNAs? Curr Genomics 2015, 16, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowlton, K.U. Pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 Induced Cardiac Injury from the Perspective of the Virus. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2020, 147, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansueto, G.; Niola, M.; Napoli, C. Can COVID 2019 Induce a Specific Cardiovascular Damage or It Exacerbates Pre-Existing Cardiovascular Diseases? Pathol Res Pract 2020, 216, 153086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dal Ferro, M.; Bussani, R.; Paldino, A.; Nuzzi, V.; Collesi, C.; Zentilin, L.; Schneider, E.; Correa, R.; Silvestri, F.; Zacchigna, S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2, Myocardial Injury and Inflammation: Insights from a Large Clinical and Autopsy Study. Clin Res Cardiol 2021, 110, 1822–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trypsteen, W.; Cleemput, J.V.; van Snippenberg, W.; Gerlo, S.; Vandekerckhove, L. On the Whereabouts of SARS-CoV-2 in the Human Body: A Systematic Review. PLOS Pathogens 2020, 16, e1009037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, B.T.; Maioli, H.; Johnston, R.; Chaudhry, I.; Fink, S.L.; Xu, H.; Najafian, B.; Deutsch, G.; Lacy, J.M.; Williams, T.; et al. Histopathology and Ultrastructural Findings of Fatal COVID-19 Infections in Washington State: A Case Series. Lancet 2020, 396, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavazzi, G.; Pellegrini, C.; Maurelli, M.; Belliato, M.; Sciutti, F.; Bottazzi, A.; Sepe, P.A.; Resasco, T.; Camporotondo, R.; Bruno, R.; et al. Myocardial Localization of Coronavirus in COVID-19 Cardiogenic Shock. Eur J Heart Fail 2020, 22, 911–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudit, G.Y.; Kassiri, Z.; Jiang, C.; Liu, P.P.; Poutanen, S.M.; Penninger, J.M.; Butany, J. SARS-Coronavirus Modulation of Myocardial ACE2 Expression and Inflammation in Patients with SARS. Eur J Clin Invest 2009, 39, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.B.; Farzan, M.; Chen, B.; Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 Entry into Cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2022, 23, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SARS-CoV-2 Replication Revisited: Molecular Insights and Current and Emerging Antiviral Strategies. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2673-8112/5/6/85 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Walls, A.C.; Park, Y.-J.; Tortorici, M.A.; Wall, A.; McGuire, A.T.; Veesler, D. Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell 2020, 181, 281–292.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaglia, E.; Vecchione, C.; Puca, A.A. COVID-19 Infection and Circulating ACE2 Levels: Protective Role in Women and Children. Front Pediatr 2020, 8, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, C.; Huang, C.; Zhou, W.; Ji, X.; Zhang, F.; Wang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Cui, Q. AGTR2, One Possible Novel Key Gene for the Entry of SARS-CoV-2 Into Human Cells. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform 2021, 18, 1230–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.J.; Hiscox, J.A.; Hooper, N.M. ACE2: From Vasopeptidase to SARS Virus Receptor. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2004, 25, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topol, E.J. COVID-19 Can Affect the Heart. Science 2020, 370, 408–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, D.W.; Oudit, G.Y.; Reich, H.; Kassiri, Z.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Q.C.; Backx, P.H.; Penninger, J.M.; Herzenberg, A.M.; Scholey, J.W. Loss of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme-2 (Ace2) Accelerates Diabetic Kidney Injury. Am J Pathol 2007, 171, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicin, L.; Abplanalp, W.T.; Mellentin, H.; Kattih, B.; Tombor, L.; John, D.; Schmitto, J.D.; Heineke, J.; Emrich, F.; Arsalan, M.; et al. Cell Type-Specific Expression of the Putative SARS-CoV-2 Receptor ACE2 in Human Hearts. Eur Heart J 2020, 41, 1804–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangos, M.; Budde, H.; Kolijn, D.; Sieme, M.; Zhazykbayeva, S.; Lódi, M.; Herwig, M.; Gömöri, K.; Hassoun, R.; Robinson, E.L.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infects Human Cardiomyocytes Promoted by Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Int J Cardiol 2022, 362, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sungnak, W.; Huang, N.; Bécavin, C.; Berg, M.; Queen, R.; Litvinukova, M.; Talavera-López, C.; Maatz, H.; Reichart, D.; Sampaziotis, F.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Entry Factors Are Highly Expressed in Nasal Epithelial Cells Together with Innate Immune Genes. Nat Med 2020, 26, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Chatterjee, S.; Xiao, K.; Riedel, I.; Wang, Y.; Foo, R.; Bär, C.; Thum, T. MicroRNAs Targeting the SARS-CoV-2 Entry Receptor ACE2 in Cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2020, 148, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scialo, F.; Daniele, A.; Amato, F.; Pastore, L.; Matera, M.G.; Cazzola, M.; Castaldo, G.; Bianco, A. ACE2: The Major Cell Entry Receptor for SARS-CoV-2. Lung 2020, 198, 867–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crackower, M.A.; Sarao, R.; Oudit, G.Y.; Yagil, C.; Kozieradzki, I.; Scanga, S.E.; Oliveira-dos-Santos, A.J.; da Costa, J.; Zhang, L.; Pei, Y.; et al. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 Is an Essential Regulator of Heart Function. Nature 2002, 417, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Shen, X.Z.; Bernstein, E.A.; Giani, J.F.; Eriguchi, M.; Zhao, T.V.; Gonzalez-Villalobos, R.A.; Fuchs, S.; Liu, G.Y.; Bernstein, K.E. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Enhances the Oxidative Response and Bactericidal Activity of Neutrophils. Blood 2017, 130, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudit, G.Y.; Kassiri, Z.; Patel, M.P.; Chappell, M.; Butany, J.; Backx, P.H.; Tsushima, R.G.; Scholey, J.W.; Khokha, R.; Penninger, J.M. Angiotensin II-Mediated Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Mediate the Age-Dependent Cardiomyopathy in ACE2 Null Mice. Cardiovasc Res 2007, 75, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brosnihan, K.B.; Neves, L.A.A.; Joyner, J.; Averill, D.B.; Chappell, M.C.; Sarao, R.; Penninger, J.; Ferrario, C.M. Enhanced Renal Immunocytochemical Expression of ANG-(1-7) and ACE2 during Pregnancy. Hypertension 2003, 42, 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuba, K.; Imai, Y.; Rao, S.; Gao, H.; Guo, F.; Guan, B.; Huan, Y.; Yang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, W.; et al. A Crucial Role of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS Coronavirus-Induced Lung Injury. Nat Med 2005, 11, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haga, S.; Yamamoto, N.; Nakai-Murakami, C.; Osawa, Y.; Tokunaga, K.; Sata, T.; Yamamoto, N.; Sasazuki, T.; Ishizaka, Y. Modulation of TNF-Alpha-Converting Enzyme by the Spike Protein of SARS-CoV and ACE2 Induces TNF-Alpha Production and Facilitates Viral Entry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 7809–7814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peiris, J.S.M.; Guan, Y.; Yuen, K.Y. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. Nat Med 2004, 10, S88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Guo, F.; Liu, K.; Wang, H.; Rao, S.; Yang, P.; Jiang, C. Endocytosis of the Receptor-Binding Domain of SARS-CoV Spike Protein Together with Virus Receptor ACE2. Virus Res 2008, 136, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Liu, X.; Xu, J.; Weng, L.; Ren, J.; Ge, J.; Zou, Y. Mas Receptor Mediates Cardioprotection of Angiotensin-(1-7) against Angiotensin II-Induced Cardiomyocyte Autophagy and Cardiac Remodelling through Inhibition of Oxidative Stress. J Cell Mol Med 2016, 20, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.-Y.; Kuo, W.-W.; Yeh, Y.-L.; Ho, T.-J.; Lin, J.-Y.; Lin, D.-Y.; Chu, C.-H.; Tsai, F.-J.; Tsai, C.-H.; Huang, C.-Y. ANG II Promotes IGF-IIR Expression and Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis by Inhibiting HSF1 via JNK Activation and SIRT1 Degradation. Cell Death Differ 2014, 21, 1262–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeager, C.L.; Ashmun, R.A.; Williams, R.K.; Cardellichio, C.B.; Shapiro, L.H.; Look, A.T.; Holmes, K.V. Human Aminopeptidase N Is a Receptor for Human Coronavirus 229E. Nature 1992, 357, 420–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faghihi, H. CD147 as an Alternative Binding Site for the Spike Protein on the Surface of SARS-CoV-2. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2020, 24, 11992–11994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilts, J.; Crozier, T.W.M.; Greenwood, E.J.D.; Lehner, P.J.; Wright, G.J. No Evidence for Basigin/CD147 as a Direct SARS-CoV-2 Spike Binding Receptor. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.-F.; Vander Kooi, C.W. Neuropilin Functions as an Essential Cell Surface Receptor. J Biol Chem 2015, 290, 29120–29126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Bag, A.K.; Singh, R.K.; Talmadge, J.E.; Batra, S.K.; Datta, K. Multifaceted Role of Neuropilins in the Immune System: Potential Targets for Immunotherapy. Front Immunol 2017, 8, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, D. The Potential of Melatonin in the Prevention and Attenuation of Oxidative Hemolysis and Myocardial Injury from Cd147 SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Receptor Binding. Melatonin Research 2020, 3, 380–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurchenko, V.; Constant, S.; Eisenmesser, E.; Bukrinsky, M. Cyclophilin–CD147 Interactions: A New Target for Anti-Inflammatory Therapeutics. Clin Exp Immunol 2010, 160, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipoor, S.D.; Mirsaeidi, M. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry beyond the ACE2 Receptor. Mol Biol Rep 2022, 49, 10715–10727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantuti-Castelvetri, L.; Ojha, R.; Pedro, L.D.; Djannatian, M.; Franz, J.; Kuivanen, S.; van der Meer, F.; Kallio, K.; Kaya, T.; Anastasina, M.; et al. Neuropilin-1 Facilitates SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry and Infectivity. Science 2020, 370, 856–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayi, B.S.; Leibowitz, J.A.; Woods, A.T.; Ammon, K.A.; Liu, A.E.; Raja, A. The Role of Neuropilin-1 in COVID-19. PLoS Pathog 2021, 17, e1009153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.; He, X.; Huang, F.; Chen, J.; Yang, X. Electrocardiogram Analysis of Patients with Different Types of COVID-19. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2020, 25, e12806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.; Randeva, H.S.; Chatha, K.; Hall, M.; Spandidos, D.A.; Karteris, E.; Kyrou, I. Neuropilin-1 as a New Potential SARS-CoV-2 Infection Mediator Implicated in the Neurologic Features and Central Nervous System Involvement of COVID-19. Mol Med Rep 2020, 22, 4221–4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, J.L.; Simonetti, B.; Klein, K.; Chen, K.-E.; Williamson, M.K.; Antón-Plágaro, C.; Shoemark, D.K.; Simón-Gracia, L.; Bauer, M.; Hollandi, R.; et al. Neuropilin-1 Is a Host Factor for SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Science 2020, 370, 861–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, B. CD26: A Surface Protease Involved in T-Cell Activation. Immunol Today 1994, 15, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vankadari, N.; Wilce, J.A. Emerging WuHan (COVID-19) Coronavirus: Glycan Shield and Structure Prediction of Spike Glycoprotein and Its Interaction with Human CD26. Emerg Microbes Infect 2020, 9, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röhrborn, D.; Wronkowitz, N.; Eckel, J. DPP4 in Diabetes. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayesh, M.E.H.; Kohara, M.; Tsukiyama-Kohara, K. Effects of Oxidative Stress on Viral Infections: An Overview. Npj Viruses 2025, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Q.; Ding, Y.; Liu, W.; Liu, S. Viral Infections and the Glutathione Peroxidase Family: Mechanisms of Disease Development. Antioxid Redox Signal 2025, 42, 623–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.-D.; Ji, T.-T.; Dong, J.-R.; Feng, H.; Chen, F.-Q.; Chen, X.; Zhao, H.-Y.; Chen, D.-K.; Ma, W.-T. Pathogenesis and Treatment of Cytokine Storm Induced by Infectious Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 13009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kombe Kombe, A.J.; Fotoohabadi, L.; Gerasimova, Y.; Nanduri, R.; Lama Tamang, P.; Kandala, M.; Kelesidis, T. The Role of Inflammation in the Pathogenesis of Viral Respiratory Infections. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Zhou, L.; Tian, W.; Liu, X.; Yang, L.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, S.; Wang, D.W.; Wei, J. Deep Insight into Cytokine Storm: From Pathogenesis to Treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2025, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragab, D.; Salah Eldin, H.; Taeimah, M.; Khattab, R.; Salem, R. The COVID-19 Cytokine Storm; What We Know So Far. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Shi, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Huang, L.; Zhang, C.; Liu, S.; Zhao, P.; Liu, H.; Zhu, L.; et al. Pathological Findings of COVID-19 Associated with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2020, 8, 420–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, I.A.; Badolato-Corrêa, J.; Familiar-Macedo, D.; de-Oliveira-Pinto, L.M. Th17 Cells in Viral Infections-Friend or Foe? Cells 2021, 10, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coomes, E.A.; Haghbayan, H. Interleukin-6 in Covid-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Rev Med Virol 2020, 30, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Kilian, C.; Turner, J.-E.; Bosurgi, L.; Roedl, K.; Bartsch, P.; Gnirck, A.-C.; Cortesi, F.; Schultheiß, C.; Hellmig, M.; et al. Clonal Expansion and Activation of Tissue-Resident Memory-like Th17 Cells Expressing GM-CSF in the Lungs of Severe COVID-19 Patients. Sci Immunol 2021, 6, eabf6692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeisel, M.B.; Felmlee, D.J.; Baumert, T.F. Hepatitis C Virus Entry. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2013, 369, 87–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helenius, A. Virus Entry: Looking Back and Moving Forward. J Mol Biol 2018, 430, 1853–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, M.Z.; Bujko, K.; Ciechanowicz, A.; Sielatycka, K.; Cymer, M.; Marlicz, W.; Kucia, M. SARS-CoV-2 Entry Receptor ACE2 Is Expressed on Very Small CD45- Precursors of Hematopoietic and Endothelial Cells and in Response to Virus Spike Protein Activates the Nlrp3 Inflammasome. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2021, 17, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, S.; Huang, K.; Li, H. Roles of Inflammasomes in Viral Myocarditis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copin, M.-C.; Parmentier, E.; Duburcq, T.; Poissy, J.; Mathieu, D. Lille COVID-19 ICU and Anatomopathology Group Time to Consider Histologic Pattern of Lung Injury to Treat Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19 Infection. Intensive Care Med 2020, 46, 1124–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Yang, M.; Wan, C.; Yi, L.-X.; Tang, F.; Zhu, H.-Y.; Yi, F.; Yang, H.-C.; Fogo, A.B.; Nie, X.; et al. Renal Histopathological Analysis of 26 Postmortem Findings of Patients with COVID-19 in China. Kidney Int 2020, 98, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, Z.; Flammer, A.J.; Steiger, P.; Haberecker, M.; Andermatt, R.; Zinkernagel, A.S.; Mehra, M.R.; Schuepbach, R.A.; Ruschitzka, F.; Moch, H. Endothelial Cell Infection and Endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, 1417–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pons, S.; Fodil, S.; Azoulay, E.; Zafrani, L. The Vascular Endothelium: The Cornerstone of Organ Dysfunction in Severe SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Crit Care 2020, 24, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, W.; Lammens, M.; Kerckhofs, A.; Voets, E.; Van San, E.; Van Coillie, S.; Peleman, C.; Mergeay, M.; Sirimsi, S.; Matheeussen, V.; et al. Fatal Lymphocytic Cardiac Damage in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Autopsy Reveals a Ferroptosis Signature. ESC Heart Fail 2020, 7, 3772–3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loo, J.; Spittle, D.A.; Newnham, M. COVID-19, Immunothrombosis and Venous Thromboembolism: Biological Mechanisms. Thorax 2021, 76, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, T.T.; Mairuhu, A.T.A.; de Kruif, M.D.; Klein, S.K.; Gerdes, V.E.A.; ten Cate, H.; Brandjes, D.P.M.; Levi, M.; van Gorp, E.C.M. Infections and Endothelial Cells. Cardiovasc Res 2003, 60, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esper, R.J.; Nordaby, R.A.; Vilariño, J.O.; Paragano, A.; Cacharrón, J.L.; Machado, R.A. Endothelial Dysfunction: A Comprehensive Appraisal. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2006, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loomans, C.J.M.; Wan, H.; de Crom, R.; van Haperen, R.; de Boer, H.C.; Leenen, P.J.M.; Drexhage, H.A.; Rabelink, T.J.; van Zonneveld, A.J.; Staal, F.J.T. Angiogenic Murine Endothelial Progenitor Cells Are Derived from a Myeloid Bone Marrow Fraction and Can Be Identified by Endothelial NO Synthase Expression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2006, 26, 1760–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackermann, M.; Verleden, S.E.; Kuehnel, M.; Haverich, A.; Welte, T.; Laenger, F.; Vanstapel, A.; Werlein, C.; Stark, H.; Tzankov, A.; et al. Pulmonary Vascular Endothelialitis, Thrombosis, and Angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S.; Wu, J. Bioactive Peptides on Endothelial Function. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdecchia, P.; Cavallini, C.; Spanevello, A.; Angeli, F. The Pivotal Link between ACE2 Deficiency and SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Eur J Intern Med 2020, 76, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opal, S.M.; van der Poll, T. Endothelial Barrier Dysfunction in Septic Shock. J Intern Med 2015, 277, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, T.R.; Leeper, N.J.; Hynes, K.L.; Gewertz, B.L. Interleukin-6 Causes Endothelial Barrier Dysfunction via the Protein Kinase C Pathway. J Surg Res 2002, 104, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C.A.; Jones, S.A. IL-6 as a Keystone Cytokine in Health and Disease. Nat Immunol 2015, 16, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination and Myocarditis or Myopericarditis: Population Based Cohort Study | The BMJ. Available online: https://www.bmj.com/content/375/bmj-2021-068665 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Mevorach, D.; Anis, E.; Cedar, N.; Bromberg, M.; Haas, E.J.; Nadir, E.; Olsha-Castell, S.; Arad, D.; Hasin, T.; Levi, N.; et al. Myocarditis after BNT162b2 mRNA Vaccine against Covid-19 in Israel. N Engl J Med 2021, 385, 2140–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, B.; Kamat, I.; Hotez, P.J. Myocarditis With COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines. Circulation 2021, 144, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, B.; Kamat, I.; Hotez, P.J. Myocarditis With COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines. Circulation 2021, 144, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patone, M.; Mei, X.W.; Handunnetthi, L.; Dixon, S.; Zaccardi, F.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Watkinson, P.; Khunti, K.; Harnden, A.; Coupland, C.A.C.; et al. Risks of Myocarditis, Pericarditis, and Cardiac Arrhythmias Associated with COVID-19 Vaccination or SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Nat Med 2022, 28, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oster, M.E.; Shay, D.K.; Su, J.R.; Gee, J.; Creech, C.B.; Broder, K.R.; Edwards, K.; Soslow, J.H.; Dendy, J.M.; Schlaudecker, E.; et al. Myocarditis Cases Reported After mRNA-Based COVID-19 Vaccination in the US From December 2020 to August 2021. JAMA 2022, 327, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gargano, J.W.; Wallace, M.; Hadler, S.C.; Langley, G.; Su, J.R.; Oster, M.E.; Broder, K.R.; Gee, J.; Weintraub, E.; Shimabukuro, T.; et al. Use of mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine After Reports of Myocarditis Among Vaccine Recipients: Update from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices - United States, June 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021, 70, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, G.A.; Parsons, G.T.; Gering, S.K.; Meier, A.R.; Hutchinson, I.V.; Robicsek, A. Myocarditis and Pericarditis After Vaccination for COVID-19. JAMA 2021, 326, 1210–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.K.; Lavine, K.J.; Lin, C.-Y. Myocarditis after Covid-19 mRNA Vaccination. N Engl J Med 2021, 385, 1332–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical Considerations: Myocarditis after COVID-19 Vaccines | CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/myocarditis.html (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Bouchlarhem, A.; Boulouiz, S.; Bazid, Z.; ismaili, N.; El ouafi, N. Is There a Causal Link Between Acute Myocarditis and COVID-19 Vaccination: An Umbrella Review of Published Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Clin Med Insights Cardiol 2024, 18, 11795468231221406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mevorach, D.; Anis, E.; Cedar, N.; Bromberg, M.; Haas, E.J.; Nadir, E.; Olsha-Castell, S.; Arad, D.; Hasin, T.; Levi, N.; et al. Myocarditis after BNT162b2 mRNA Vaccine against Covid-19 in Israel. N Engl J Med 2021, 385, 2140–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witberg, G.; Barda, N.; Hoss, S.; Richter, I.; Wiessman, M.; Aviv, Y.; Grinberg, T.; Auster, O.; Dagan, N.; Balicer, R.D.; et al. Myocarditis after Covid-19 Vaccination in a Large Health Care Organization. N Engl J Med 2021, 385, 2132–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahasing, C.; Doungngern, P.; Jaipong, R.; Nonmuti, P.; Chimmanee, J.; Wongsawat, J.; Boonyasirinant, T.; Wanlapakorn, C.; Leelapatana, P.; Yingchoncharoen, T.; et al. Myocarditis and Pericarditis Following COVID-19 Vaccination in Thailand. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchlarhem, A.; Boulouiz, S.; Bazid, Z.; Ismaili, N.; El Ouafi, N. Is There a Causal Link Between Acute Myocarditis and COVID-19 Vaccination: An Umbrella Review of Published Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Clin Med Insights Cardiol 2024, 18, 11795468231221406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoto, P.D.M.C.; Byamungu, L.N.; Brand, A.S.; Tamuzi, J.L.; Kakubu, M.A.M.; Wiysonge, C.S.; Gray, G. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Myocarditis and Pericarditis in Adolescents Following COVID-19 BNT162b2 Vaccination. NPJ Vaccines 2023, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Feng, L.; Li, Y.; Lowe, S.; Guo, Z.; Bentley, R.; Xie, C.; Wu, B.; Xie, P.; Xia, W.; et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Association Between SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination and Myocarditis or Pericarditis. Am J Prev Med 2023, 64, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiese, A.; Frati, P.; Del Duca, F.; Santoro, P.; Manetti, A.C.; La Russa, R.; Di Paolo, M.; Turillazzi, E.; Fineschi, V. Myocardial Pathology in COVID-19-Associated Cardiac Injury: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021, 11, 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patone, M.; Mei, X.W.; Handunnetthi, L.; Dixon, S.; Zaccardi, F.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Watkinson, P.; Khunti, K.; Harnden, A.; Coupland, C.A.C.; et al. Risk of Myocarditis After Sequential Doses of COVID-19 Vaccine and SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Age and Sex. Circulation 2022, 146, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlstad, Ø.; Hovi, P.; Husby, A.; Härkänen, T.; Selmer, R.M.; Pihlström, N.; Hansen, J.V.; Nohynek, H.; Gunnes, N.; Sundström, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination and Myocarditis in a Nordic Cohort Study of 23 Million Residents. JAMA Cardiol 2022, 7, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikawa, T.; Takagi, H.; Ishikawa, K.; Kuno, T. Myocardial Injury Characterized by Elevated Cardiac Troponin and In-Hospital Mortality of COVID-19: An Insight from a Meta-Analysis. J Med Virol 2021, 93, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiese, A.; Frati, P.; Del Duca, F.; Santoro, P.; Manetti, A.C.; La Russa, R.; Di Paolo, M.; Turillazzi, E.; Fineschi, V. Myocardial Pathology in COVID-19-Associated Cardiac Injury: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021, 11, 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikawa, T.; Takagi, H.; Ishikawa, K.; Kuno, T. Myocardial Injury Characterized by Elevated Cardiac Troponin and In-Hospital Mortality of COVID-19: An Insight from a Meta-Analysis. J Med Virol 2021, 93, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husby, A.; Gulseth, H.L.; Hovi, P.; Hansen, J.V.; Pihlström, N.; Gunnes, N.; Härkänen, T.; Dahl, J.; Karlstad, Ø.; Heliö, T.; et al. Clinical Outcomes of Myocarditis after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccination in Four Nordic Countries: Population Based Cohort Study. bmjmed 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouchana, L.; Blet, A.; Al-Khalaf, M.; Kafil, T.S.; Nair, G.; Robblee, J.; Drici, M.; Valnet-Rabier, M.; Micallef, J.; Salvo, F.; et al. Features of Inflammatory Heart Reactions Following mRNA COVID-19 Vaccination at a Global Level. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2022, 111, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.J.; Na, Y.; Hyun, H.J.; Nham, E.; Yoon, J.G.; Seong, H.; Seo, Y.B.; Choi, W.S.; Song, J.Y.; Kim, D.W.; et al. Comparative Safety Analysis of mRNA and Adenoviral Vector COVID-19 Vaccines: A Nationwide Cohort Study Using an Emulated Target Trial Approach. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2024, 30, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, J.; Song, M.C.; Park, S.; Kang, H.; Kyung, T.; Kim, N.; Kim, D.K.; Bae, K.; Lee, K.J.; Lee, E.; et al. Deciphering Deaths Associated with Severe Serious Adverse Events Following SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Vaccine: X 2024, 16, 100446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florek, K.; Sokolski, M. Myocarditis Associated with COVID-19 Vaccination. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buoninfante, A.; Andeweg, A.; Genov, G.; Cavaleri, M. Myocarditis Associated with COVID-19 Vaccination. NPJ Vaccines 2024, 9, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Three Decades of Messenger RNA Vaccine Development. ResearchGate 2025. [CrossRef]

- Nunez-Castilla, J.; Stebliankin, V.; Baral, P.; Balbin, C.A.; Sobhan, M.; Cickovski, T.; Mondal, A.M.; Narasimhan, G.; Chapagain, P.; Mathee, K.; et al. Potential Autoimmunity Resulting from Molecular Mimicry between SARS-CoV-2 Spike and Human Proteins. Viruses 2022, 14, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arutyunov, G.P.; Tarlovskaya, E.I.; Arutyunov, A.G.; Lopatin, Y.M. ACTIV Investigators Impact of Heart Failure on All-Cause Mortality in COVID-19: Findings from the Eurasian International Registry. ESC Heart Fail 2023, 10, 1013–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymans, S.; Cooper, L.T. Myocarditis after COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination: Clinical Observations and Potential Mechanisms. Nat Rev Cardiol 2022, 19, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; et al.; Authors/Task Force Members 2021 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure: Developed by the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). With the Special Contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail 2022, 24, 4–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Bozkurt, B.; Aguilar, D.; Allen, L.A.; Byun, J.J.; Colvin, M.M.; Deswal, A.; Drazner, M.H.; Dunlay, S.M.; Evers, L.R.; et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2022, 145, e895–e1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, V.; Mukherjee, D.; Peng Ang, S.; Kainth, T.; Naz, S.; Babu Shrestha, A.; Agrawal, V.; Mitra, S.; Ee Chia, J.; Jilma, B.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine-Associated Myocarditis: Analysis of the Suspected Cases Reported to the EudraVigilance and a Systematic Review of the Published Literature. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc 2023, 49, 101280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florek, K.; Sokolski, M. Myocarditis Associated with COVID-19 Vaccination. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myocarditis and Pericarditis after COVID-19 Vaccination: Clinical Management Guidance for Healthcare Professionals. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/myocarditis-and-pericarditis-after-covid-19-vaccination/myocarditis-and-pericarditis-after-covid-19-vaccination-guidance-for-healthcare-professionals (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Sularz, A.K.; Hua, A.; Ismail, T. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines and Myocarditis. Clinical Medicine 2023, 23, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Y.P.; Agstam, S.; Yadav, A.; Gupta, A.; Gupta, A. Cardiovascular Manifestations of COVID-19: An Evidence-Based Narrative Review. Indian J Med Res 2021, 153, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, J.N.; Swaminathan, M.; Adedipe, A.; Garcia-Sayan, E.; Hung, J.; Kelly, N.; Kort, S.; Nagueh, S.; Poh, K.K.; Sarwal, A.; et al. American Society of Echocardiography COVID-19 Statement Update: Lessons Learned and Preparation for Future Pandemics. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2023, 36, 1127–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, M.G.; Bobba, A.; Chourasia, P.; Gangu, K.; Shuja, H.; Dandachi, D.; Farooq, A.; Avula, S.R.; Shekhar, R.; Sheikh, A.B. COVID-19 Associated Myocarditis Clinical Outcomes among Hospitalized Patients in the United States: A Propensity Matched Analysis of National Inpatient Sample. Viruses 2022, 14, 2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, B.; Bluemke, D.A.; Lüscher, T.F.; Neubauer, S. Long COVID: Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 with a Cardiovascular Focus. Eur Heart J 2022, 43, 1157–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.S.; Anderson, S.A.; Steele, J.M.; Wilson, H.C.; Muniz, J.C.; Soslow, J.H.; Beroukhim, R.S.; Maksymiuk, V.; Jacquemyn, X.; Frosch, O.H.; et al. Cardiac Manifestations and Outcomes of COVID-19 Vaccine-Associated Myocarditis in the Young in the USA: Longitudinal Results from the Myocarditis After COVID Vaccination (MACiV) Multicenter Study. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 76, 102809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Li, H.; Santosa, A.; Wettermark, B.; Fall, T.; Björk, J.; Börjesson, M.; Gisslén, M.; Nyberg, F. Cardiovascular Events Following Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccination in Adults: A Nationwide Swedish Study. Eur Heart J 2025, 46, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaliyaperumal, D.; Bhargavi, K.; Ramaraju, K.; Nair, K.S.; Ramalingam, S.; Alagesan, M. Electrocardiographic Changes in COVID-19 Patients: A Hospital-Based Descriptive Study. Indian J Crit Care Med 2022, 26, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll-Bernardes, R.; Mattos, J.D.; Schaustz, E.B.; Sousa, A.S.; Ferreira, J.R.; Tortelly, M.B.; Pimentel, A.M.L.; Figueiredo, A.C.B.S.; Noya-Rabelo, M.M.; Sales, A.R.K.; et al. Troponin in COVID-19: To Measure or Not to Measure? Insights from a Prospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11, 5951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majure, D.T.; Gruberg, L.; Saba, S.G.; Kvasnovsky, C.; Hirsch, J.S.; Jauhar, R. Northwell Health COVID-19 Research Consortium Usefulness of Elevated Troponin to Predict Death in Patients With COVID-19 and Myocardial Injury. Am J Cardiol 2021, 138, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.C.; Ladenson, J.H.; Mason, J.W.; Jaffe, A.S. Elevations of Cardiac Troponin I Associated with Myocarditis. Experimental and Clinical Correlates. Circulation 1997, 95, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usta Atmaca, H.; Çiçek, N.E.; Pişkinpaşa, M.E. Role of Serum NT-proBNP Levels in Early Prediction of Prognosis in Severe COVID-19 Pneumonia. Istanbul Med J 2023, 24, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faridi, K.F.; Hennessey, K.C.; Shah, N.; Soufer, A.; Wang, Y.; Sugeng, L.; Agarwal, V.; Sharma, R.; Sewanan, L.R.; Hur, D.J.; et al. Left Ventricular Systolic Function and Inpatient Mortality in Patients Hospitalized with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2020, 33, 1414–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz-Menger, J.; Collini, V.; Gröschel, J.; Adler, Y.; Brucato, A.; Christian, V.; Ferreira, V.M.; Gandjbakhch, E.; Heidecker, B.; Kerneis, M.; et al. 2025 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Myocarditis and Pericarditis. Eur Heart J 2025, 46, 3952–4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overton, P.M.; Toshner, M.; Mulligan, C.; Vora, P.; Nikkho, S.; de Backer, J.; Lavon, B.R.; Klok, F.A. Pulmonary Thromboembolic Events in COVID-19—A Systematic Literature Review. Pulm Circ 2022, 12, e12113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doeblin, P.; Jahnke, C.; Schneider, M.; Al-Tabatabaee, S.; Goetze, C.; Weiss, K.J.; Tanacli, R.; Faragli, A.; Witt, U.; Stehning, C.; et al. CMR Findings after COVID-19 and after COVID-19-Vaccination-Same but Different? Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2022, 38, 2057–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, V.M.; Schulz-Menger, J.; Holmvang, G.; Kramer, C.M.; Carbone, I.; Sechtem, U.; Kindermann, I.; Gutberlet, M.; Cooper, L.T.; Liu, P.; et al. Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance in Nonischemic Myocardial Inflammation: Expert Recommendations. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018, 72, 3158–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahrholdt, H.; Wagner, A.; Deluigi, C.C.; Kispert, E.; Hager, S.; Meinhardt, G.; Vogelsberg, H.; Fritz, P.; Dippon, J.; Bock, C.-T.; et al. Presentation, Patterns of Myocardial Damage, and Clinical Course of Viral Myocarditis. Circulation 2006, 114, 1581–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.L.; Davogustto, G.; Soslow, J.H.; Wassenaar, J.W.; Parikh, A.P.; Chew, J.D.; Dendy, J.M.; George-Durrett, K.M.; Parra, D.A.; Clark, D.E.; et al. Characteristics of COVID-19 Myocarditis With and Without Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome. Am J Cardiol 2022, 168, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Qin, L.; Xu, X.; Chen, R.; Zhang, G.; Wang, B.; Li, B.; Chu, X.-M. Immune Modulation: The Key to Combat SARS-CoV-2 Induced Myocardial Injury. Front Immunol 2025, 16, 1561946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abumayyaleh, M.; Schupp, T.; Behnes, M.; El-Battrawy, I.; Hamdani, N.; Akin, I. COVID-19 and Myocarditis: Trends, Clinical Characteristics, and Future Directions. J Clin Med 2025, 14, 4560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Chen, D.; Yuan, D.; Lausted, C.; Choi, J.; Dai, C.L.; Voillet, V.; Duvvuri, V.R.; Scherler, K.; Troisch, P.; et al. Multi-Omics Resolves a Sharp Disease-State Shift between Mild and Moderate COVID-19. Cell 2020, 183, 1479–1495.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genetic and Epigenetic Intersections in COVID-19-Associated Cardiovascular Disease: Emerging Insights and Future Directions. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9059/13/2/485 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Xu, S.; Ilyas, I.; Weng, J. Endothelial Dysfunction in COVID-19: An Overview of Evidence, Biomarkers, Mechanisms and Potential Therapies. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2023, 44, 695–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.