Submitted:

22 December 2025

Posted:

24 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

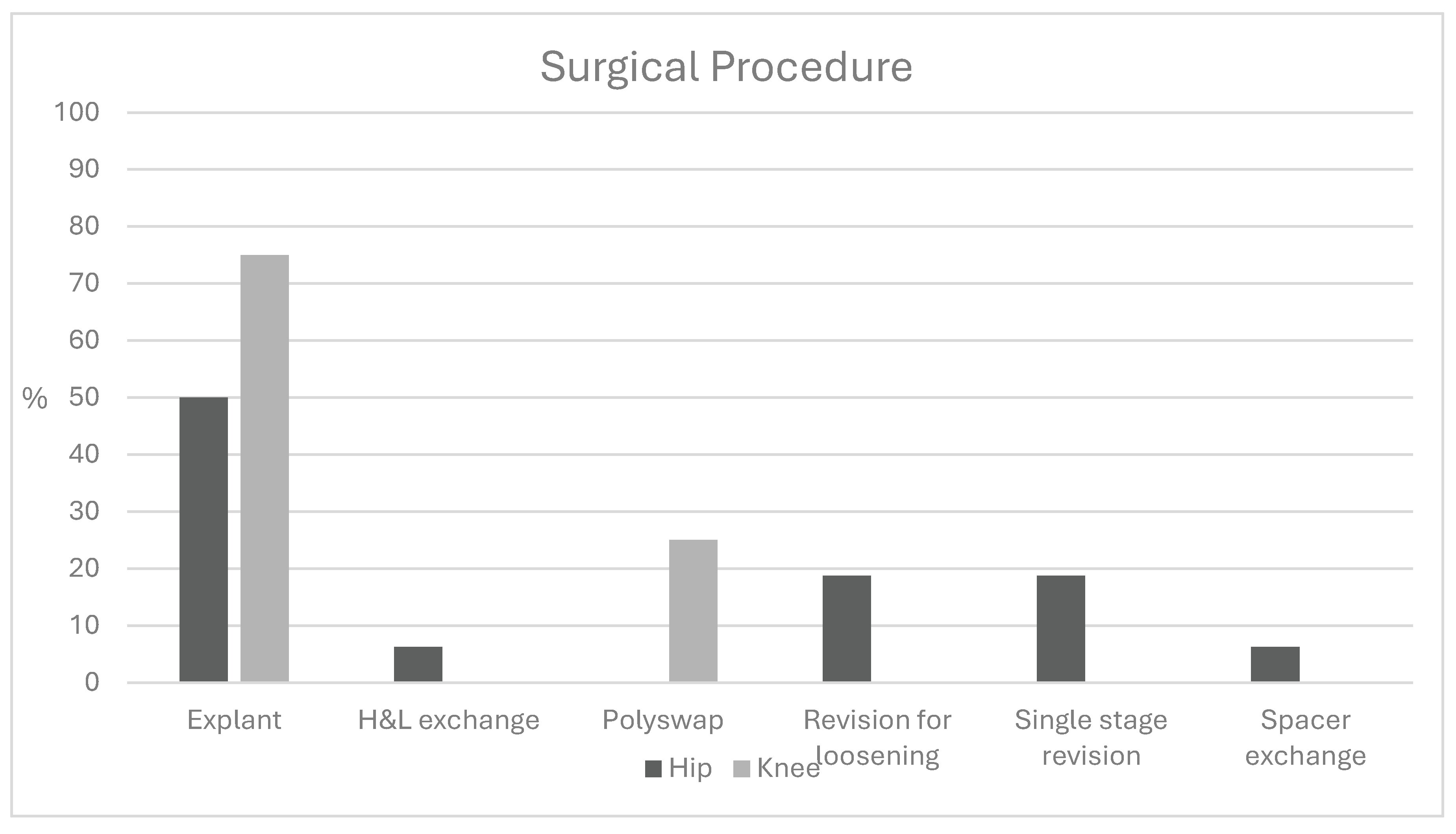

Introduction Cutibacterium species, common commensal gram-positive bacteria, present a diagnostic challenge for arthroplasty surgeons. While Cutibacterium infections have been well characterized in shoulder surgery, their presentation and clinical significance in total hip (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) remain less understood. Methods A retrospective chart review identified patients with positive Cutibacterium cultures following THA or TKA. Demographics, laboratory values, and microbiologic data were collected. Statistical comparisons were performed using t-tests and chi-squared analysis. One-year outcomes were evaluated using the MSIS ORT criteria among patients undergoing further surgical intervention. Results Twenty-nine patients with Cutibacterium-positive cultures were identified (21 THA, 8 TKA); 15 (52%) were polymicrobial. Ten THA patients (47.6%) and seven TKA patients (87.5%) met MSIS criteria for infection. Mean time to culture positivity was similar between THA (6.8 days) and TKA (7.4 days; p = 0.57). Sonication cultures were positive in 24% of THA and 12.5% of TKA cases. Mean ESR was 36.4 mm/h for THA and 51.5 mm/h for TKA (p = 0.21); mean CRP was 35.2 and 36.8 mg/dL, respectively (p = 0.95). Mean synovial cell counts were 27,055 for THA and 22,194 for TKA, with PMN percentages of 68% and 73.9% (p = 0.72, 0.70). Monomicrobial infections demonstrated a mean cell count of 24,143 with 58.9% PMNs, compared to 25,903 and 78.8% in polymicrobial cases. At one year, 72% of patients undergoing subsequent surgery achieved successful outcomes. Higher ASA classification was the only significant predictor of failure (mean 3.0 vs. 2.75). Conclusion Cutibacterium-associated THA and TKA infections often present with delayed culture growth, mild inflammatory markers, and frequent polymicrobial involvement. Most patients experience favorable outcomes following surgical management, though greater medical comorbidity may predict treatment failure.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Methods

Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boddapati, V; Fu, MC; Mayman, DJ; Su, EP; Sculco, PK; McLawhorn, AS. Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty for Periprosthetic Joint Infection Is Associated With Increased Postoperative Morbidity and Mortality Relative to Noninfectious Revisions. The Journal of Arthroplasty 2018, 33, 521–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozic, KJ. The Impact of Infection After Total Hip Arthroplasty on Hospital and Surgeon Resource Utilization. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005, 87, 1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtz, SM; Lau, E; Watson, H; Schmier, JK; Parvizi, J. Economic Burden of Periprosthetic Joint Infection in the United States. The Journal of Arthroplasty 2012, 27, 61–65.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodson, CC; Craig, EV; Cordasco, FA; Dines, DM; Dines, JS; DiCarlo, E; et al. Propionibacterium acnes infection after shoulder arthroplasty: A diagnostic challenge. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 2010, 19, 303–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, JW; Kozak, TK; Hanssen, AD; Cofield, RH. Infection after shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001, 206–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubin, GG; Portillo, ME; Trampuz, A; Corvec, S. Propionibacterium acnes, an emerging pathogen: From acne to implant-infections, from phylotype to resistance. Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses 2014, 44, 241–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, JG; Gandhi, SD; Park, DK; Fischgrund, JS. Cutibacterium acnes in Spine Pathology: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 2019, 27, e633–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, M-F; Berthelot, P; Fresard, A; Cazorla, C; Carricajo, A; Vautrin, A-C; et al. Arthroplastic and osteosynthetic infections due to Propionibacterium acnes: a retrospective study of 52 cases, 1995-2002. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2005, 24, 739–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leheste, JR; Ruvolo, KE; Chrostowski, JE; Rivera, K; Husko, C; Miceli, A; et al. P. acnes-Driven Disease Pathology: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2017, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, M; Passley, TM; Purcell, JM; Leheste, JR. Early-Onset Parkinson’s Disease With Multiple Positive Intraoperative Spinal Tissue Cultures for Cutibacterium acnes. Cureus 2021, 13, e17607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, M; Takemura, T; Guzman, J; Uchida, K; Furukawa, A; Suzuki, Y; et al. Localization of Propionibacterium acnes in granulomas supports a possible etiologic link between sarcoidosis and the bacterium. Mod Pathol 2012, 25, 1284–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, CK; Marsh, JP; Drinković, D; Walker, CG; Poon, PC. Propionibacterium acnes in primary shoulder arthroplasty: rates of colonization, patient risk factors, and efficacy of perioperative prophylaxis. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 2016, 25, 846–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, MJ; Jancosko, JJ; Mendoza, V; Nottage, WM. The Incidence of Propionibacterium acnes in Shoulder Arthroscopy; The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery: Arthroscopy, 2015; Volume 31, pp. 1702–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namdari, S; Nicholson, T; Parvizi, J; Ramsey, M. Preoperative doxycycline does not decolonize Propionibacterium acnes from the skin of the shoulder: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 2017, 26, 1495–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolakowski, L; Lai, JK; Duvall, GT; Jauregui, JJ; Dubina, AG; Jones, DL; et al. Neer Award 2018: Benzoyl peroxide effectively decreases preoperative Cutibacterium acnes shoulder burden: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 2018, 27, 1539–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, B; Al, K; Pena-Diaz, AM; Athwal, GS; Drosdowech, D; Faber, KJ; et al. Cutibacterium acnes and the shoulder microbiome. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 2018, 27, 1734–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvall, G; Kaveeshwar, S; Sood, A; Klein, A; Williams, K; Kolakowski, L; et al. Benzoyl peroxide use transiently decreases Cutibacterium acnes load on the shoulder. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 2020, 29, 794–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiBartola, AC; Swank, KR; Flanigan, DC. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction complicated by Propionibacterium acnes infection: case series. The Physician and Sportsmedicine 2018, 46, 273–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patzer, T; Petersdorf, S; Krauspe, R; Verde, PE; Henrich, B; Hufeland, M. Prevalence of Propionibacterium acnes in the glenohumeral compared with the subacromial space in primary shoulder arthroscopies. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 2018, 27, 771–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, U; Torrance, E; Townsend, R; Davies, S; Mackenzie, T; Funk, L. Low-grade infections in nonarthroplasty shoulder surgery. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 2017, 26, 1553–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajita, Y; Iwahori, Y; Harada, Y; Deie, M. Incidence of Propionibacterium acnes in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Journal of Orthopaedic Science 2020, 25, 110–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gausden, EB; Villa, J; Warner, SJ; Redko, M; Pearle, A; Miller, A; et al. Nonunion After Clavicle Osteosynthesis: High Incidence of Propionibacterium acnes. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma 2017, 31, 229–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, JM; Dennis, DA; Kleeman-Forsthuber, L; Yang, CC; Miner, TM; Jennings, JM. Cutibacterium colonization of the anterior and lateral thigh. The Bone & Joint Journal 2020, 102-B, 52–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nodzo, SR; Westrich, GH; Henry, MW; Miller, AO. Clinical Analysis of Propionibacterium acnes Infection After Total Knee Arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty 2016, 31, 1986–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvizi, J; Tan, TL; Goswami, K; Higuera, C; Della Valle, C; Chen, AF; et al. The 2018 Definition of Periprosthetic Hip and Knee Infection: An Evidence-Based and Validated Criteria. The Journal of Arthroplasty 2018, 33, 1309–1314.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fillingham, YA; Della Valle, CJ; Suleiman, LI; Springer, BD; Gehrke, T; Bini, SA; et al. Definition of Successful Infection Management and Guidelines for Reporting of Outcomes After Surgical Treatment of Periprosthetic Joint Infection: From the Workgroup of the Musculoskeletal Infection Society (MSIS). The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 2019, 101, e69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elston, MJ; Dupaix, JP; Opanova, MI; Atkinson, RE. Cutibacterium acnes (formerly Proprionibacterium acnes) and Shoulder Surgery. Hawaii J Health Soc Welf 2019, 78, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zeller, V; Ghorbani, A; Strady, C; Leonard, P; Mamoudy, P; Desplaces, N. Propionibacterium acnes: an agent of prosthetic joint infection and colonization. J Infect 2007, 55, 119–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renz, N; Mudrovcic, S; Perka, C; Trampuz, A. Orthopedic implant-associated infections caused by Cutibacterium spp. – A remaining diagnostic challenge. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alijanipour, P; Bakhshi, H; Parvizi, J. Diagnosis of Periprosthetic Joint Infection: The Threshold for Serological Markers. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® 2013, 471, 3186–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Definition for Periprosthetic Joint Infection. The Journal of Arthroplasty 2011, 26, 1136–8. [CrossRef]

- Flurin, L; Greenwood-Quaintance, KE; Patel, R. Microbiology of polymicrobial prosthetic joint infection. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease 2019, 94, 255–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisrenoult, P. Cutibacterium acnes prosthetic joint infection: Diagnosis and treatment. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research 2018, 104, S19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batten, TJ; Gallacher, S; Thomas, WJ; Kitson, J; Smith, CD. C. acnes in the joint, is it all just a false positive? Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portillo, ME; Corvec, S; Borens, O; Trampuz, A. Propionibacterium acnes: An Underestimated Pathogen in Implant-Associated Infections. BioMed Research International 2013, 2013, e804391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achermann, Y; Liu, J; Zbinden, R; Zingg, PO; Anagnostopoulos, A; Barnard, E; et al. Propionibacterium avidum: A Virulent Pathogen Causing Hip Periprosthetic Joint Infection. Clin Infect Dis 2018, 66, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shohat, N; Goswami, K; Clarkson, S; Chisari, E; Breckenridge, L; Gursay, D; et al. Direct Anterior Approach to the Hip Does Not Increase the Risk for Subsequent Periprosthetic Joint Infection. The Journal of Arthroplasty 2021, 36, 2038–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namdari, S; Nicholson, T; Parvizi, J. Cutibacterium acnes is Isolated from Air Swabs: Time to Doubt the Value of Traditional Cultures in Shoulder Surgery? Arch Bone Jt Surg 2020, 8, 506–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew-Littorin, C; Brüggemann, H; Davidsson, S; Nilsdotter-Augustinsson, Å; Hellmark, B; Söderquist, B. Clonal diversity of Cutibacterium acnes (formerly Propionibacterium acnes) in prosthetic joint infections. Anaerobe 2019, 59, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic | THA | TKA | p-value |

| N | 21 | 8 | |

| Male Sex (%) | 10 (47.6) | 1 (12.5) | 0.19 |

| Age (mean (SD)) | 65.8 (9.32) | 64.7 (12.0) | 0.82 |

| BMI (mean (SD)) | 34.6 (6.7) | 31.2 (11.3) | 0.47 |

| ASA (mean (SD)) | 2.79 (0.43) | 2.62 (0.52) | 0.44 |

| Prior revision (%) | 0.23 | ||

| No | 17 (81.0) | 5 (62.5) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) | |

| Yes | 4 (19.0) | 2 (25.0) | |

| Met MSIS Criteria (%) | 10 (47.6) | 7 (87.5) | 0.13 |

| Total Patients | 21 | 8 |

| Laboratory Data | THA | TKA | p-value |

| Polymicrobial (%) | 10 (47.6) | 5 (62.5) | 0.68 |

| Time to culture positivity (mean (SD)) | 6.75 (2.5) | 7.39 (2.6) | 0.57 |

| Number of positive cultures (mean (SD)) | 2.05 (1.6) | 1.75 (1.5) | 0.66 |

| WBC count (mean (SD)) | 27,055 (3,9922) | 22,195 (2,9172) | 0.77 |

| PMN % (mean (SD)) | 67.92 (36.5) | 73.88 (29.3) | 0.70 |

| Sonicated tissues positive for Cutibacterium (%) | 0.24 | ||

| No | 16 (76.2) | 7 (87.5) | |

| Yes | 5 (23.8) | 1 (12.5) | |

| Alpha Defensin (%) | 0.41 | ||

| Unknown | 17 (81.0) | 8 (100.0) | |

| Negative | 2 (9.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Positive | 2 (9.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| ESR mm/h (mean (SD)) | 36.38 (27.3) | 51.50 (31.1) | 0.21 |

| CRP (mean (SD)) | 35.23 (63.0) | 36.80 (38.0) | 0.95 |

| THA Anterior Approach | THA Posterior Approach | |

| Monomicrobial | 6 | 4 |

| Polymicrobial | 4 | 4 |

| Total | 10 | 8 |

| Tier 1. Infection control with no continued antibiotic therapy |

| Tier 2. Infection control with the patient on suppressive antibiotic therapy |

| Tier 3. Need for reoperation and/or revision and/or spacer retention (assigned to subgroups A, B, C, D, E, and F based on the type of reoperation) |

| Aseptic revision at >1 year from initiation of PJI treatment |

| Septic revision (including debridement, antibiotics, and implant retention [DAIR]) at >1 year from initiation of PJI treatment (excluding amputation, resection arthroplasty, and arthrodesis) |

| Aseptic revision at ≤1 year from initiation of PJI treatment |

| Septic revision (including DAIR) at ≤1 year from initiation of PJI treatment (excluding amputation, resection arthroplasty, and arthrodesis) |

| Amputation, resection arthroplasty, or arthrodesis |

| Retained spacer |

| Tier 4. Death (assigned to subgroups A or B). |

| Death ≤1 year from initiation of PJI treatment |

| Death >1 year from initiation of PJI treatment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).