Submitted:

23 December 2025

Posted:

24 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The concept of individual cellular intelligence reframes cells as dynamic entities endowed with sensory, reactive, adaptive, and memory-like capabilities, enabling them to navigate lifelong metabolic and extrinsic stressors. A likely vital component of this intelligence system are stress-responsive G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) networks, interconnected by common signaling adaptors. These stress-regulating networks orchestrate the detection, processing, and experience retention of environmental cues, events, and stressors. These networks, along with other sensory mechanisms such as receptor-mediated signaling and DNA damage detection, allow cells to acknowledge and interpret stressors such as oxidative stress or nutrient scarcity. Reactive responses, including autophagy and apoptosis, mitigate immediate damage, while adaptive strategies, such as metabolic rewiring, receptor expression alteration and epigenetic modifications, enhance long-term survival. Cellular experiences that are effectively translated into ‘memories’, both transient and heritable, likely relies on GPCR-induced epigenetic and mitochondrial adaptations, enabling anticipation of future insults. Dysregulation of these processes and networks can drive pathological states, shaping resilience or susceptibility to chronic diseases like cancer, neurodegeneration, and metabolic disorders. Employing molecular evidence, here we underscore the presence of an effective cellular intelligence, supported by multi-level sensory GPCR networks. The quality of this intelligence acts as a critical determinant of somatic health and a promising frontier for therapeutic innovation. Future research leveraging single-cell omics and systems biology may unravel the molecular underpinnings of these capabilities, offering new strategies to prevent or reverse stress-induced pathologies.

Keywords:

Introduction

Defining Cell Intelligence (CI)

The Origins of Cellular Intelligence (CI)

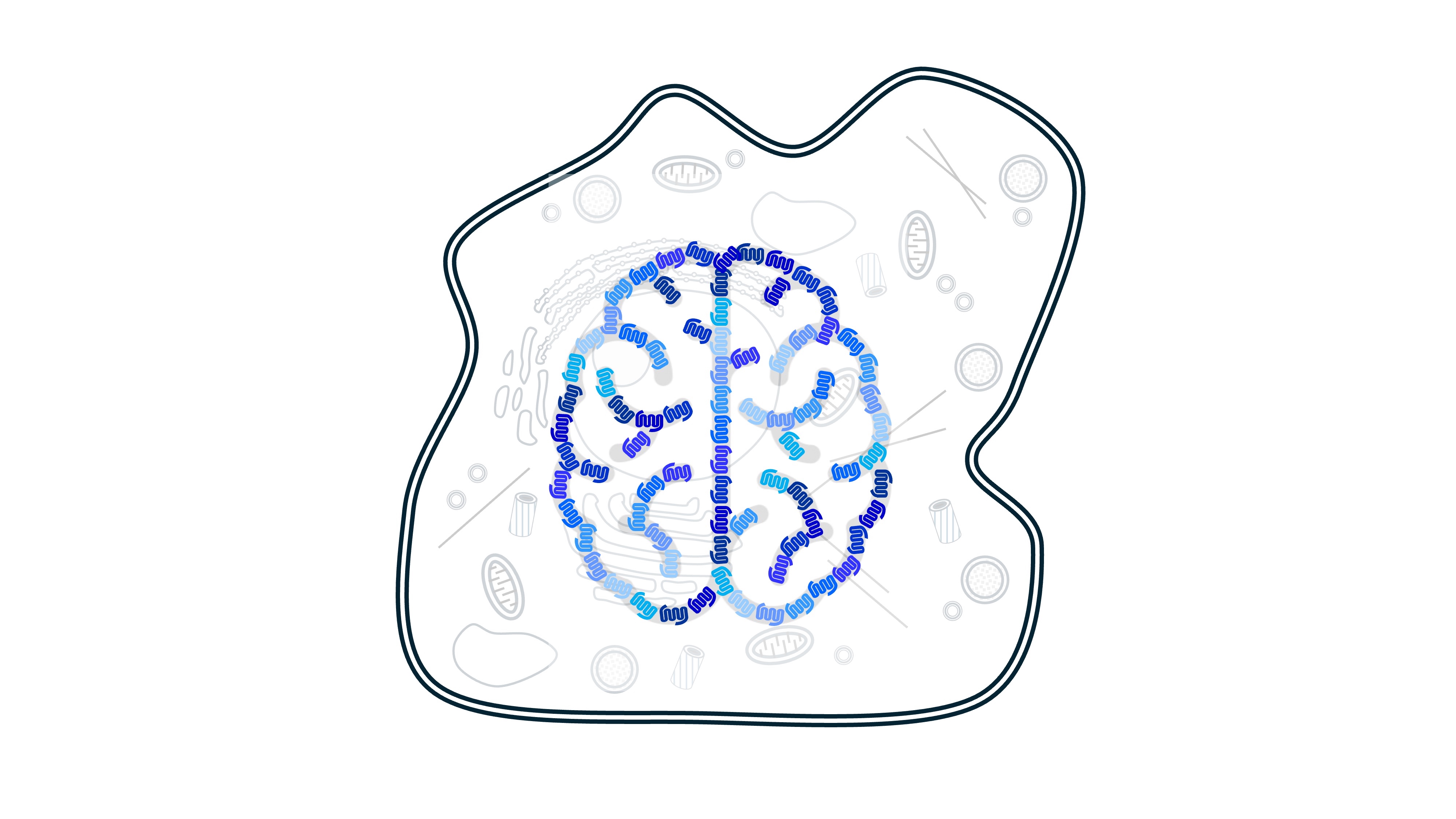

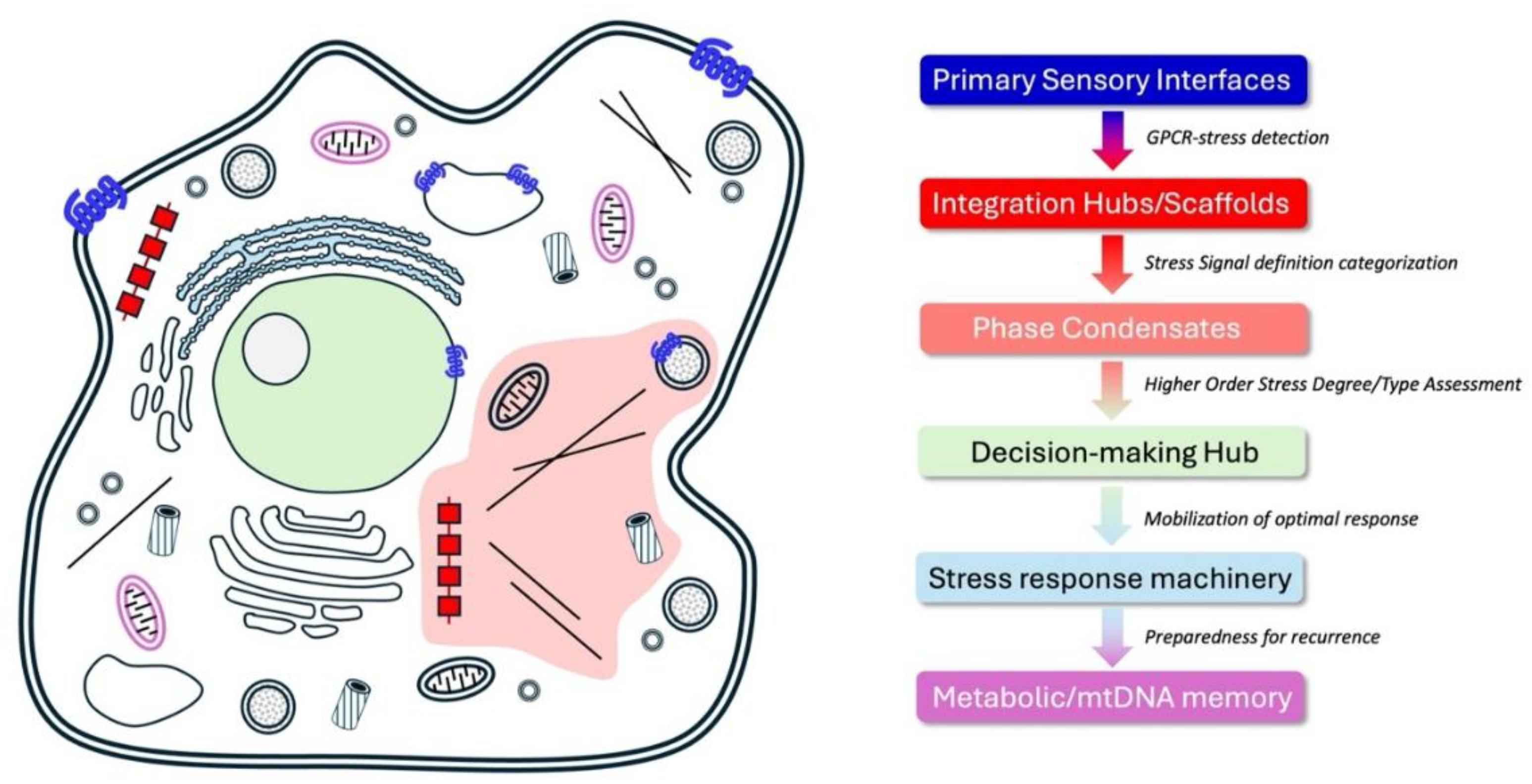

Spatial Organization of Cellular Intelligence (CI)

Emerging Role of Phase Separation in the Spatial Organization of Cellular Intelligence

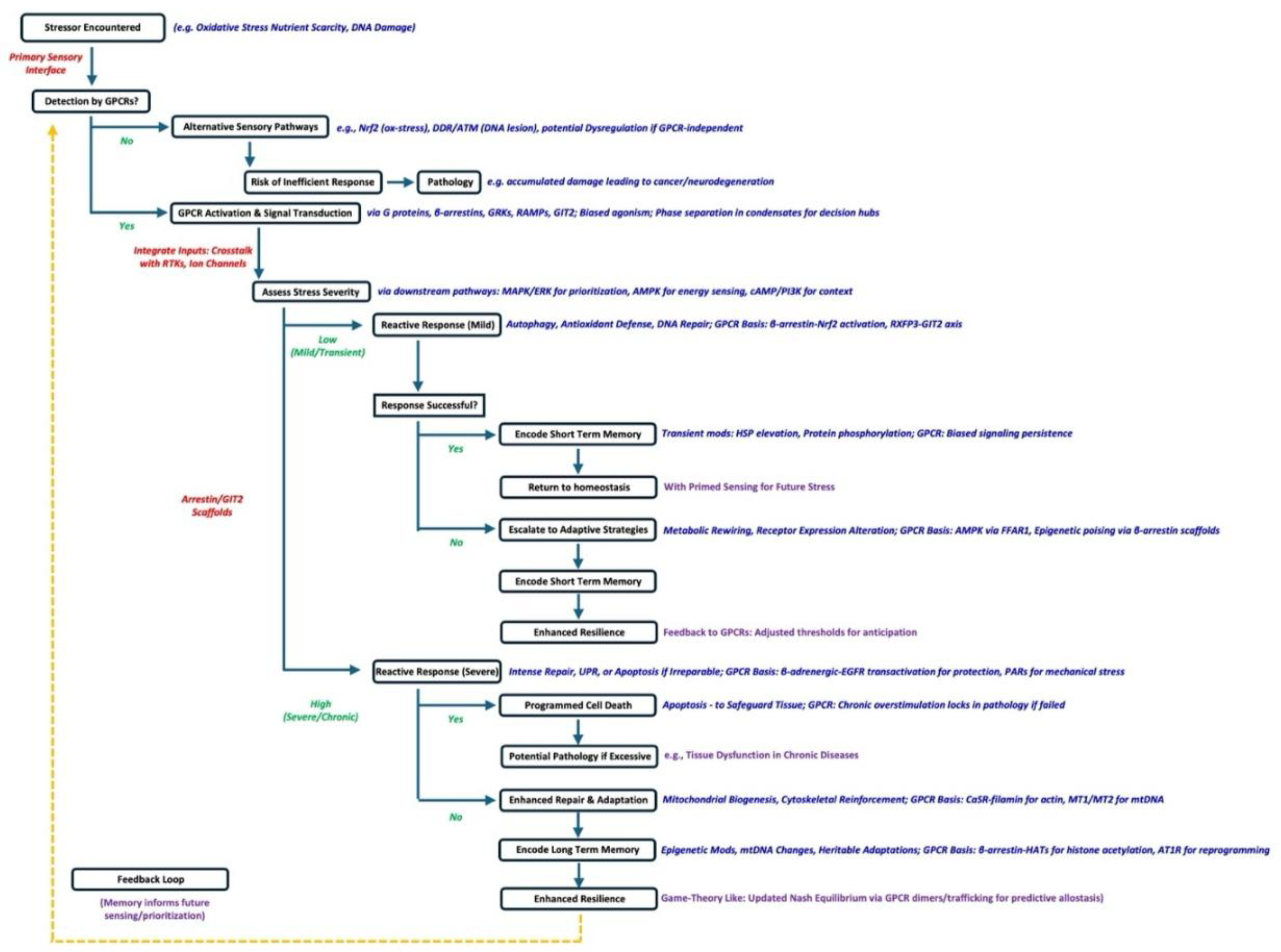

Reactive and Adaptive Responses: Decision-Making Under Stress

Short- and Long-Term Memory Processes: Learning from Stress

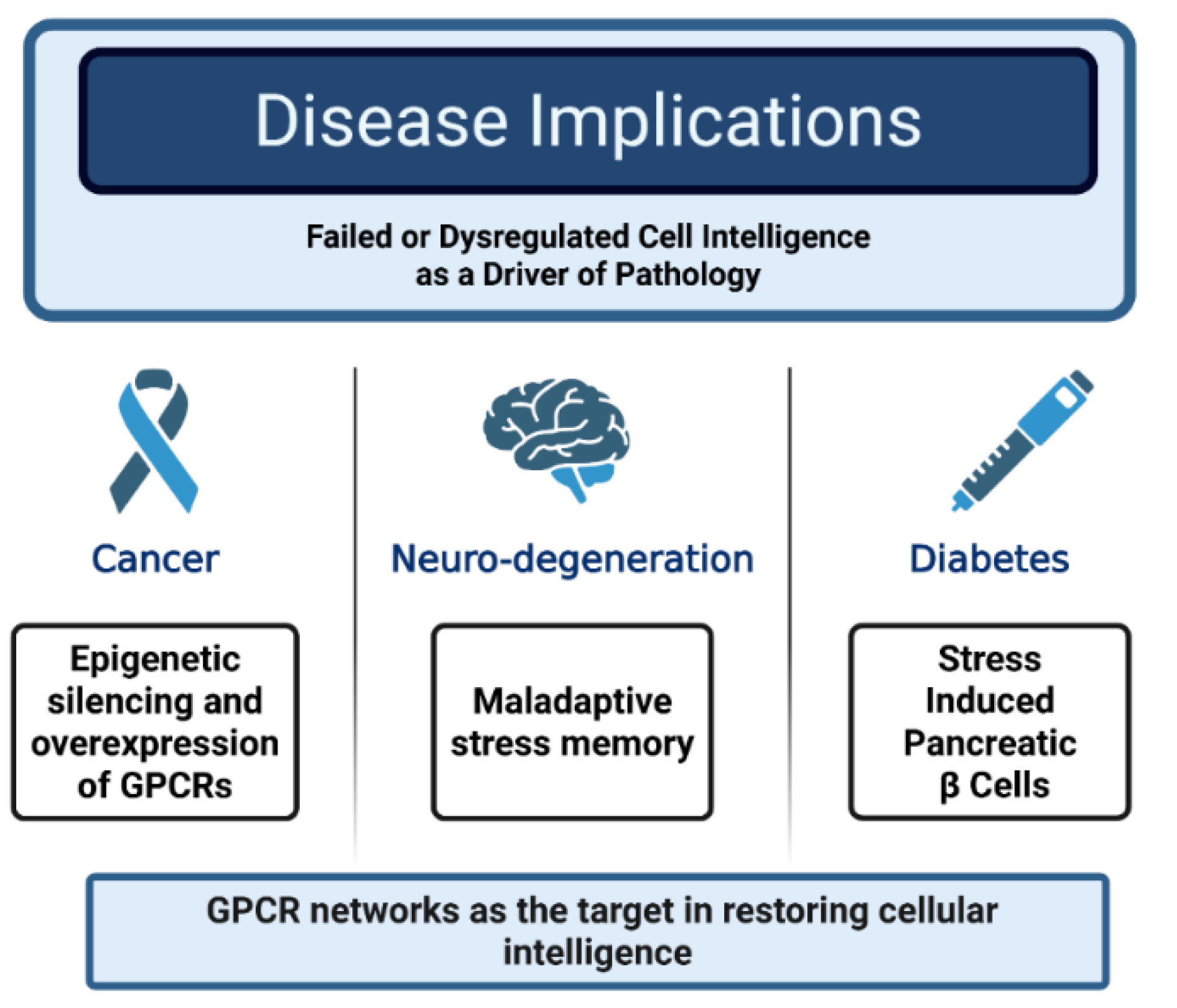

Implications for Long-Term Disease: When Intelligence Fails

How GPCRs Generate and Mediate the Phenomenon of Cell Intelligence

GPCR Networks as Sensory Hubs of Cellular Intelligence

GPCRs as Game-Theory Strategists: Cellular Nash Equilibria in the Repeated Stress Game

GPCR Networks in Cellular Memory Formation

GPCR Signaling and Epigenetics in Cellular Stress and CI

Implications for Long-Term Disease: When CI Fails

Future Directions: Exploiting Cellular Intelligence and GPCR Networks

Conclusions

The Future - Cellular Fractals of Disease

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoeijmakers, J. H. J. (2009). DNA damage, aging, and cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 361(15), 1475–1485. [CrossRef]

- Medzhitov, R. (2010). Inflammation 2010: New adventures of an old flame. Cell, 140(6), 771–776. [CrossRef]

- Pierce, K. L., et al. (2002). Seven-transmembrane receptors. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 3(9), 639–650. [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, D. M., et al. (2009). The structure and function of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature, 459(7245), 356–363. [CrossRef]

- Lefkowitz, R. J., & Shenoy, S. K. (2005). Transduction of receptor signals by β-arrestins. Science, 308(5721), 512–517. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D. C. (2005). A mitochondrial paradigm of metabolic and degenerative diseases, aging, and cancer: A dawn for evolutionary medicine. Annual Review of Genetics, 39, 359–407. [CrossRef]

- Leysen H, Walter D, Christiaenssen B, Vandoren R, Harputluoğlu İ, Van Loon N, Maudsley S. GPCRs Are Optimal Regulators of Complex Biological Systems and Orchestrate the Interface between Health and Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Dec 13;22(24):13387. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q. (2013). Role of Nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology, 53, 401–426. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S. P., & Bartek, J. (2009). The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature, 461(7267), 1071–1078. [CrossRef]

- Hardie, D. G., et al. (2012). AMPK: A nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 13(4), 251–262. [CrossRef]

- Jaenisch, R., & Bird, A. (2003). Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: How the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nature Genetics, 33(Suppl), 245–254. [CrossRef]

- Netea, M. G., et al. (2016). Trained immunity: A program of innate immune memory in health and disease. Science, 352(6284), aaf1098. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S., et al. (2010). Epigenetics in cancer. Carcinogenesis, 31(1), 27–36. [CrossRef]

- Jones, P. A., & Baylin, S. B. (2007). The epigenomics of cancer. Cell, 128(4), 683–692. [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, W., Maudsley, S. (2010). The Devil is in the Dose: Complexity of Receptor Systems and Responses. In: Mattson, M., Calabrese, E. (eds) Hormesis. Humana Press. [CrossRef]

- Lyon, P. (2015). The cognitive cell: Bacterial behavior reconsidered. Frontiers in Microbiology, 6, 264. [CrossRef]

- Shalaeva DN, Galperin MY, Mulkidjanian AY. Eukaryotic G protein-coupled receptors as descendants of prokaryotic sodium-translocating rhodopsins. Biol Direct. 2015 Oct 15;10:63. [CrossRef]

- Fang B, Zhao L, Du X, Liu Q, Yang H, Li F, Sheng Y, Zhao W, Zhong H. Studying the rhodopsin-like G protein-coupled receptors by atomic force microscopy. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken). 2021 Aug;78(8):400-416. [CrossRef]

- Maudsley S, Martin B, Luttrell LM. The origins of diversity and specificity in g protein-coupled receptor signaling. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005 Aug;314(2):485-94. [CrossRef]

- Maudsley S, Siddiqui S, Martin B. Systems analysis of arrestin pathway functions. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2013;118:431-67. [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, S. K., & Lefkowitz, R. J. (2011). β-arrestin-mediated receptor trafficking and signal transduction. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 32(9), 521–533. [CrossRef]

- Maudsley S., Leysen, H., van Gastel, J., Martin, B. (2022). Systems Pharmacology: Enabling Multidimensional Therapeutics. Comprehensive Pharmacology, Editor(s): Terry Kenakin, Elsevier, 2022, Pages 725-769, ISBN 9780128208762, doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-820472-6.00017-7.

- McLatchie, L. M., Fraser, N. J., Main, M. J., Wise, A., Brown, J., Thompson, N., Solari, R., Lee, M. G., & Foord, S. M. (1998). RAMPs regulate the transport and ligand specificity of the calcitonin-receptor-like receptor. Nature, 393(6683), 333–339. [CrossRef]

- Maudsley S, Zamah AM, Rahman N, Blitzer JT, Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ, Hall RA. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor association with Na(+)/H(+) exchanger regulatory factor potentiates receptor activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2000 Nov;20(22):8352-63. [CrossRef]

- Chadwick W, Martin B, Chapter MC, Park SS, Wang L, Daimon CM, Brenneman R, Maudsley S. GIT2 acts as a potential keystone protein in functional hypothalamic networks associated with age-related phenotypic changes in rats. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36975. [CrossRef]

- Martin B, Chadwick W, Janssens J, Premont RT, Schmalzigaug R, Becker KG, Lehrmann E, Wood WH, Zhang Y, Siddiqui S, Park SS, Cong WN, Daimon CM, Maudsley S. GIT2 Acts as a Systems-Level Coordinator of Neurometabolic Activity and Pathophysiological Aging. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2016 Jan 18;6:191. [CrossRef]

- Maudsley S, Martin B, Janssens J, Etienne H, Jushaj A, van Gastel J, Willemsen A, Chen H, Gesty-Palmer D, Luttrell LM. Informatic deconvolution of biased GPCR signaling mechanisms from in vivo pharmacological experimentation. Methods. 2016 Jan 1;92:51-63. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Dinh Cat, A., et al. (2013). Angiotensin II and oxidative stress. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling, 19(12), 1405–1418. [CrossRef]

- Cekic, C., & Linden, J. (2016). Purinergic regulation of the immune system. Nature Reviews Immunology, 16(3), 177–192. [CrossRef]

- van Gastel J, Leysen H, Santos-Otte P, Hendrickx JO, Azmi A, Martin B, Maudsley S. The RXFP3 receptor is functionally associated with cellular responses to oxidative stress and DNA damage. Aging (Albany NY). 2019 Dec 3;11(23):11268-11313. [CrossRef]

- Leysen H, Walter D, Clauwaert L, Hellemans L, van Gastel J, Vasudevan L, Martin B, Maudsley S. The Relaxin-3 Receptor, RXFP3, Is a Modulator of Aging-Related Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Apr 15;23(8):4387. [CrossRef]

- Rakesh K, Yoo B, Kim IM, Salazar N, Kim KS, Rockman HA. beta-Arrestin-biased agonism of the angiotensin receptor induced by mechanical stress. Sci Signal. 2010 Jun 8;3(125):ra46. [CrossRef]

- Noma T, Lemaire A, Naga Prasad SV, Barki-Harrington L, Tilley DG, Chen J, Le Corvoisier P, Violin JD, Wei H, Lefkowitz RJ, Rockman HA. Beta-arrestin-mediated beta1-adrenergic receptor transactivation of the EGFR confers cardioprotection. J Clin Invest. 2007 Sep;117(9):2445-58. [CrossRef]

- Hjälm G, MacLeod RJ, Kifor O, Chattopadhyay N, Brown EM. Filamin-A binds to the carboxyl-terminal tail of the calcium-sensing receptor, an interaction that participates in CaR-mediated activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2001 Sep 14;276(37):34880-7. [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, O., & Akira, S. (2010). Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell, 140(6), 805–820. [CrossRef]

- Busillo, J. M., et al. (2010). β-arrestin-dependent signaling by chemokine receptors. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 285(51), 39746–39756. [CrossRef]

- Veglio F, Morra di Cella S, Schiavone D, Paglieri C, Rabbia F, Mulatero P, Chiandussi L. Peripheral adrenergic system and hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2001;23(1-2):3-14. [CrossRef]

- Jablonka, E., & Lamb, M. J. (2005). Evolution in Four Dimensions: Genetic, Epigenetic, Behavioral, and Symbolic Variation in the History of Life. MIT Press. ISBN: 9780262600699.

- Maudsley S, Pierce KL, Zamah AM, Miller WE, Ahn S, Daaka Y, Lefkowitz RJ, Luttrell LM. The beta(2)-adrenergic receptor mediates extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation via assembly of a multi-receptor complex with the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000 Mar 31;275(13):9572-80. [CrossRef]

- Benians A, Leaney JL, Tinker A. Agonist unbinding from receptor dictates the nature of deactivation kinetics of G protein-gated K+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 May 13;100(10):6239-44. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S., et al. (2018). Dopamine D2 receptor signaling modulates histone acetylation via β-arrestin. Nature Communications, 9(1), 2523. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. C., & Wei, Y. H. (2012). Mitochondrial alterations, cellular response to oxidative stress and defective protein degradation in aging. Biogerontology, 13(2), 97–113. [CrossRef]

- Hetz, C. (2012). The unfolded protein response: Controlling cell fate decisions. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 13(2), 89–102. [CrossRef]

- Chadwick W, Mitchell N, Martin B, Maudsley S. Therapeutic targeting of the endoplasmic reticulum in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012 Jan;9(1):110-9. [CrossRef]

- Maudsley S, Davidson L, Pawson AJ, Freestone SH, López de Maturana R, Thomson AA, Millar RP. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone functionally antagonizes testosterone activation of the human androgen receptor in prostate cells through focal adhesion complexes involving Hic-5. Neuroendocrinology. 2006;84(5):285-300. [CrossRef]

- Liu Z, Qin Z, Liu Y, Xia X, He L, Chen N, Hu X, Peng X. Liquid‒liquid phase separation: roles and implications in future cancer treatment. Int J Biol Sci. 2023 Aug 6;19(13):4139-4156. [CrossRef]

- Anderson PJ, Xiao P, Zhong Y, Kaakati A, Alfonso-DeSouza J, Zhang T, Zhang C, Yu K, Qi L, Ding W, Liu S, Pani B, Krishnan A, Chen O, Jassal C, Strawn J, Sun JP, Rajagopal S. β-Arrestin Condensates Regulate G Protein-Coupled Receptor Function. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2025 Apr 6:2025.04.05.647240. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Xiao K. A Mass Spectrometry-Based Structural Assay for Activation-Dependent Conformational Changes in β-Arrestins. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1957:293-308. [CrossRef]

- Gould ML, Nicholson HD. Changes in receptor location affect the ability of oxytocin to stimulate proliferative growth in prostate epithelial cells. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2019 May;31(6):1166-1179. [CrossRef]

- Reversi A, Rimoldi V, Brambillasca S, Chini B. Effects of cholesterol manipulation on the signaling of the human oxytocin receptor. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006 Oct;291(4):R861-9. [CrossRef]

- Wippich F, Bodenmiller B, Trajkovska MG, Wanka S, Aebersold R, Pelkmans L. Dual specificity kinase DYRK3 couples stress granule condensation/dissolution to mTORC1 signaling. Cell. 2013 Feb 14;152(4):791-805. [CrossRef]

- Shorter J. Phase separation of RNA-binding proteins in physiology and disease: An introduction to the JBC Reviews thematic series. J Biol Chem. 2019 May 3;294(18):7113-7114. [CrossRef]

- Ash PEA, Lei S, Shattuck J, Boudeau S, Carlomagno Y, Medalla M, Mashimo BL, Socorro G, Al-Mohanna LFA, Jiang L, Öztürk MM, Knobel M, Ivanov P, Petrucelli L, Wegmann S, Kanaan NM, Wolozin B. TIA1 potentiates tau phase separation and promotes generation of toxic oligomeric tau. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 Mar 2;118(9):e2014188118. [CrossRef]

- Islam M, Shen F, Regmi D, Petersen K, Karim MRU, Du D. Tau liquid-liquid phase separation: At the crossroads of tau physiology and tauopathy. J Cell Physiol. 2024 Jun;239(6):e30853. [CrossRef]

- Feric M, Vaidya N, Harmon TS, Mitrea DM, Zhu L, Richardson TM, Kriwacki RW, Pappu RV, Brangwynne CP. Coexisting Liquid Phases Underlie Nucleolar Subcompartments. Cell. 2016 Jun 16;165(7):1686-1697. [CrossRef]

- Lafontaine DLJ, Riback JA, Bascetin R, Brangwynne CP. The nucleolus as a multiphase liquid condensate. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021 Mar;22(3):165-182. [CrossRef]

- Abdelmohsen K, Srikantan S, Tominaga K, Kang MJ, Yaniv Y, Martindale JL, Yang X, Park SS, Becker KG, Subramanian M, Maudsley S, Lal A, Gorospe M. Growth inhibition by miR-519 via multiple p21-inducing pathways. Mol Cell Biol. 2012 Jul;32(13):2530-48. [CrossRef]

- Maudsley S, Davidson L, Pawson AJ, Chan R, López de Maturana R, Millar RP. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonists promote proapoptotic signaling in peripheral reproductive tumor cells by activating a Galphai-coupling state of the type I GnRH receptor. Cancer Res. 2004 Oct 15;64(20):7533-44. [CrossRef]

- Kroemer, G., et al. (2010). Autophagy and the integrated stress response. Molecular Cell, 40(2), 280–293. [CrossRef]

- Elmore, S. (2007). Apoptosis: A review of programmed cell death. Toxicologic Pathology, 35(4), 495–516. [CrossRef]

- Mattson, M. P., & Meffert, M. K. (2006). Roles for NF-κB in nerve cell survival, plasticity, and disease. Cell Death & Differentiation, 13(5), 852–860. [CrossRef]

- Chadwick W, Zhou Y, Park SS, Wang L, Mitchell N, Stone MD, Becker KG, Martin B, Maudsley S. Minimal peroxide exposure of neuronal cells induces multifaceted adaptive responses. PLoS One. 2010 Dec 17;5(12):e14352. [CrossRef]

- Richter, K., et al. (2010). The heat shock response: Life on the verge of death. Molecular Cell, 40(2), 253–266. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Zhou J, Zhang N, Wu X, Zhang Q, Zhang W, Li X, Tian Y. Two sensory neurons coordinate the systemic mitochondrial stress response via GPCR signaling in C. elegans. Dev Cell. 2022 Nov 7;57(21):2469-2482.e5. [CrossRef]

- Suofu Y, Li W, Jean-Alphonse FG, Jia J, Khattar NK, Li J, Baranov SV, et al. Dual role of mitochondria in producing melatonin and driving GPCR signaling to block cytochrome c release. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Sep 19;114(38):E7997-E8006. [CrossRef]

- Wu D, Casey PJ. GPCR-Gα13 Involvement in Mitochondrial Function, Oxidative Stress, and Prostate Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Jun 28;25(13):7162. [CrossRef]

- Barrangou, R., et al. (2007). CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science, 315(5819), 1709–1712. [CrossRef]

- Ling, C., & Groop, L. (2009). Epigenetics: A molecular link between environmental factors and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes, 58(12), 2718–2725. [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. (2006). Oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: Where are we now? Journal of Neurochemistry, 97(6), 1634–1658. [CrossRef]

- Gilman, A. G. (1987). G proteins: Transducers of receptor-generated signals. Annual Review of Biochemistry, 56, 615–649. [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt S, Rochais F. G proteins: more than transducers of receptor-generated signals? Circ Res. 2007 Apr 27;100(8):1109-11. [CrossRef]

- Maudsley S, Patel SA, Park SS, Luttrell LM, Martin B. Functional signaling biases in G protein-coupled receptors: Game Theory and receptor dynamics. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2012 Aug;12(9):831-40. [CrossRef]

- Wootten, D., et al. (2018). Advances in GPCR signaling: Structural insights and therapeutic potential. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 17(1), 62–80. [CrossRef]

- Maudsley S, Martin B, Luttrell LM. G protein-coupled receptor signaling complexity in neuronal tissue: implications for novel therapeutics. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2007 Feb;4(1):3-19. [CrossRef]

- Ma M, Jiang W, Zhou R. DAMPs and DAMP-sensing receptors in inflammation and diseases. Immunity. 2024 Apr 9;57(4):752-771. [CrossRef]

- Junyent M, Noori H, De Schepper R, Frajdenberg S, Elsaigh RKAH, McDonald PH, Duckett D, Maudsley S. Unravelling Convergent Signaling Mechanisms Underlying the Aging-Disease Nexus Using Computational Language Analysis. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2025 Mar 14;47(3):189. [CrossRef]

- Santos-Otte P, Leysen H, van Gastel J, Hendrickx JO, Martin B, Maudsley S. G Protein-Coupled Receptor Systems and Their Role in Cellular Senescence. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2019 Aug 23;17:1265-1277. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Barak LS, Winkler KE, Caron MG, Ferguson SS. A central role for beta-arrestins and clathrin-coated vesicle-mediated endocytosis in beta2-adrenergic receptor resensitization. Differential regulation of receptor resensitization in two distinct cell types. J Biol Chem. 1997 Oct 24;272(43):27005-14. [CrossRef]

- Cheng L, Xia F, Li Z, Shen C, Yang Z, Hou H, Sun S, Feng Y, Yong X, Tian X, Qin H, Yan W, Shao Z. Structure, function and drug discovery of GPCR signaling. Mol Biomed. 2023 Dec 4;4(1):46. [CrossRef]

- Gomes AAS, Di Michele M, Roessner RA, Damian M, Bisch PM, Sibille N, Louet M, Banères JL, Floquet N. Lipids modulate the dynamics of GPCR:β-arrestin interaction. Nat Commun. 2025 May 29;16(1):4982. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Chen T, Lu X, Lan X, Chen Z, Lu S. G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs): advances in structures, mechanisms, and drug discovery. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024 Apr 10;9(1):88. [CrossRef]

- Sulon SM, Benovic JL. Targeting G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) to G protein-coupled receptors. Curr Opin Endocr Metab Res. 2021 Feb;16:56-65. [CrossRef]

- Kotliar IB, Lorenzen E, Schwenk JM, Hay DL, Sakmar TP. Elucidating the Interactome of G Protein-Coupled Receptors and Receptor Activity-Modifying Proteins. Pharmacol Rev. 2023 Jan;75(1):1-34. [CrossRef]

- Maharana J, Banerjee R, Yadav MK, Sarma P, Shukla AK. Emerging structural insights into GPCR-β-arrestin interaction and functional outcomes. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2022 Aug;75:102406. [CrossRef]

- Muneta-Arrate I, Di Pizio A, Selent J, Diez-Alarcia R. The complexity of G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) modulation and signalling. Br J Pharmacol. 2025 Jul;182(14):3039-3043. [CrossRef]

- Gurevich VV, Gurevich EV. GPCR Signaling Regulation: The Role of GRKs and Arrestins. Front Pharmacol. 2019 Feb 19;10:125. [CrossRef]

- Mao, L. M., et al. (2005). GRK2/3 desensitization of mGluR signaling in neurons. Journal of Neuroscience, 25(40), 9189–9197. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Roy ER, Wang Y, Watkins T, Cao W. DLK-MAPK Signaling Coupled with DNA Damage Promotes Intrinsic Neurotoxicity Associated with Non-Mutated Tau. Mol Neurobiol. 2024 May;61(5):2978-2995. [CrossRef]

- Maparu K, Chatterjee D, Kaur R, Kalia N, Kuwar OK, Attri M, Singh S. Molecular crosstalk between GPCR and receptor tyrosine-protein kinase in neuroblastoma: molecular mechanism and therapeutic implications. Med Oncol. 2025 Mar 23;42(5):131. [CrossRef]

- Singh A, Shadangi S, Rana S. G-protein coupled receptors in neuroinflammation, neuropharmacology, and therapeutics. Biochem Pharmacol. 2025 Dec;242(Pt 2):117301. [CrossRef]

- Kee TR, Khan SA, Neidhart MB, Masters BM, Zhao VK, Kim YK, McGill Percy KC, Woo JA. The multifaceted functions of β-arrestins and their therapeutic potential in neurodegenerative diseases. Exp Mol Med. 2024 Feb;56(1):129-141. [CrossRef]

- Ripoll L, von Zastrow M, Blythe EE. Intersection of GPCR trafficking and cAMP signaling at endomembranes. J Cell Biol. 2025 Apr 7;224(4):e202409027. [CrossRef]

- Cai Z, Kong W. Advances in GPCRs: structure, mechanisms, disease, and pharmacology. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2024 May 1;326(5):C1291-C1292. [CrossRef]

- Kalogriopoulos NA, Tei R, Yan Y, Klein PM, Ravalin M, Cai B, Soltesz I, Li Y, Ting AY. Synthetic GPCRs for programmable sensing and control of cell behaviour. Nature. 2025 Jan;637(8044):230-239. Erratum in: Nature. 2025 Feb;638(8050):E2. doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-08607-w. [CrossRef]

- Kumari P, Inoue A, Chapman K, Lian P, Rosenbaum DM. Molecular mechanism of fatty acid activation of FFAR1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023 May 30;120(22):e2219569120. [CrossRef]

- Tan X, Jiao PL, Sun JC, Wang W, Ye P, Wang YK, Leng YQ, Wang WZ. β-Arrestin1 Reduces Oxidative Stress via Nrf2 Activation in the Rostral Ventrolateral Medulla in Hypertension. Front Neurosci. 2021 Apr 7;15:657825. [CrossRef]

- Perry-Hauser N, Maudsley S, Berchiche YA, Slosky LM. Editorial: GPCRs: signal transduction. Front Mol Biosci. 2024 Apr 10;11:1403161. [CrossRef]

- Hendrickx JO, van Gastel J, Leysen H, Martin B, Maudsley S. High-dimensionality Data Analysis of Pharmacological Systems Associated with Complex Diseases. Pharmacol Rev. 2020 Jan;72(1):191-217. [CrossRef]

- Caniceiro AB, Orzeł U, Rosário-Ferreira N, Filipek S, Moreira IS. Leveraging Artificial Intelligence in GPCR Activation Studies: Computational Prediction Methods as Key Drivers of Knowledge. Methods Mol Biol. 2025;2870:183-220. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J., Price, G. The Logic of Animal Conflict. Nature 246, 15–18 (1973). [CrossRef]

- Axelrod R, Axelrod DE, Pienta KJ. Evolution of cooperation among tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 Sep 5;103(36):13474-9. [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M. A., & Sigmund, K. (2006). Evolutionary Games and Population Dynamic. Harvard University Press.

- Hauser AS, Attwood MM, Rask-Andersen M, Schiöth HB, Gloriam DE. Trends in GPCR drug discovery: new agents, targets and indications. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017 Dec;16(12):829-842. [CrossRef]

- Insel PA, Blaschke TF, Amara SG, Meyer UA. Introduction to the Theme “New Insights, Strategies, and Therapeutics for Common Diseases”. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2022 Jan 6;62:19-24. [CrossRef]

- Gurevich VV, Gurevich EV. A boost in learning by removing nuclear phosphodiesterases and enhancing nuclear cAMP signaling. Sci Signal. 2023 Mar 28;16(778):eadg9504. [CrossRef]

- Jean-Charles PY, Kaur S, Shenoy SK. G Protein-Coupled Receptor Signaling Through β-Arrestin-Dependent Mechanisms. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2017 Sep;70(3):142-158. [CrossRef]

- Choi JW, Gardell SE, Herr DR, Rivera R, Lee CW, Noguchi K, Teo ST, Yung YC, Lu M, Kennedy G, Chun J. FTY720 (fingolimod) efficacy in an animal model of multiple sclerosis requires astrocyte sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1) modulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 Jan 11;108(2):751-6. [CrossRef]

- Xiao S, Peng K, Li C, Long Y, Yu Q. The role of sphingosine-1-phosphate in autophagy and related disorders. Cell Death Discov. 2023 Oct 18;9(1):380. [CrossRef]

- Rampino A, Marakhovskaia A, Soares-Silva T, Torretta S, Veneziani F, Beaulieu JM. Antipsychotic Drug Responsiveness and Dopamine Receptor Signaling; Old Players and New Prospects. Front Psychiatry. 2019 Jan 9;9:702. [CrossRef]

- Mancini AD, Bertrand G, Vivot K, Carpentier É, Tremblay C, Ghislain J, Bouvier M, Poitout V. β-Arrestin Recruitment and Biased Agonism at Free Fatty Acid Receptor 1. J Biol Chem. 2015 Aug 21;290(34):21131-21140. [CrossRef]

- Teng D, Zhou Y, Tang Y, Liu G, Tu Y. Mechanistic Studies on the Stereoselectivity of FFAR1 Modulators. J Chem Inf Model. 2022 Aug 8;62(15):3664-3675. [CrossRef]

- Howland KK, Brock A. Cellular barcoding tracks heterogeneous clones through selective pressures and phenotypic transitions. Trends Cancer. 2023 Jul;9(7):591-601. [CrossRef]

- Velloso JPL, Kovacs AS, Pires DEV, Ascher DB. AI-driven GPCR analysis, engineering, and targeting. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2024 Feb;74:102427. [CrossRef]

- Eichel K, von Zastrow M. Subcellular Organization of GPCR Signaling. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2018 Feb;39(2):200-208. [CrossRef]

- Schaupp L, Muth S, Rogell L, Kofoed-Branzk M, Melchior F, Lienenklaus S, et al. Microbiota-Induced Type I Interferons Instruct a Poised Basal State of Dendritic Cells. Cell. 2020 May 28;181(5):1080-1096.e19. [CrossRef]

- Jing N, Zhang K, Chen X, Liu K, Wang J, Xiao L, Zhang W, Ma P, Xu P, Cheng C, Wang D, Zhao H, He Y, Ji Z, Xin Z, Sun Y, Zhang Y, Bao W, Gong Y, Fan L, Ji Y, Zhuang G, Wang Q, Dong B, Zhang P, Xue W, Gao WQ, Zhu HH. ADORA2A-driven proline synthesis triggers epigenetic reprogramming in neuroendocrine prostate and lung cancers. J Clin Invest. 2023 Dec 15;133(24):e168670. [CrossRef]

- Laschet C, Dupuis N, Hanson J. The G protein-coupled receptors deorphanization landscape. Biochem Pharmacol. 2018 Jul;153:62-74. [CrossRef]

- Chadwick W, Keselman A, Park SS, Zhou Y, Wang L, Brenneman R, Martin B, Maudsley S. Repetitive peroxide exposure reveals pleiotropic mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling mechanisms. J Signal Transduct. 2011;2011:636951. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., et al. (2016). Histamine H1 receptor signaling primes endothelial cells for inflammation. Journal of Immunology, 196(12), 5038–5047. [CrossRef]

- van der Meer, J. W. M., et al. (2015). Trained immunity: A memory for innate host defense. Cell Host & Microbe, 17(5), 555–564. [CrossRef]

- Yuen, E. Y., et al. (2017). Serotonin 5-HT2A receptor signaling in psychiatric disorders. Molecular Psychiatry, 22(9), 1235–1244. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., et al. (2019). FFAR4 signaling modulates mitochondrial dynamics in response to oxidative stress. Molecular Metabolism, 23, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- He, L., et al. (2016). GLP-1 receptor signaling enhances mitochondrial biogenesis via AMPK. Diabetes, 65(3), 577–589. [CrossRef]

- Ushio-Fukai, M., & Alexander, R. W. (2004). Reactive oxygen species as mediators of angiogenesis signaling. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry, 264(1-2), 85–97. [CrossRef]

- Hirasawa, A., et al. (2005). Free fatty acids regulate insulin secretion from pancreatic β cells through GPR120. Nature Medicine, 11(1), 90–94. [CrossRef]

- Busillo, J. M., & Benovic, J. L. (2007). Regulation of CXCR4 signaling. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1768(4), 952–963. [CrossRef]

- Jones, P. A. (2012). Functions of DNA methylation: Islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nature Reviews Genetics, 13(7), 484–492. [CrossRef]

- Kouzarides, T. (2007). Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell, 128(4), 693–705. [CrossRef]

- Bartel, D. P. (2009). MicroRNAs: Target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell, 136(2), 215–233. [CrossRef]

- Seong, K. H., et al. (2011). Chromatin regulation by heat shock factor in stress response. Genes & Development, 25(18), 1962–1974. [CrossRef]

- Feil, R., & Fraga, M. F. (2012). Epigenetics and the environment: Emerging patterns and implications. Nature Reviews Genetics, 13(2), 97–109. [CrossRef]

- Nestler, E. J. (2014). Epigenetic mechanisms of drug addiction. Neuropharmacology, 76(Pt B), 259–268. [CrossRef]

- Mayr, B., & Montminy, M. (2001). Transcriptional regulation by the phosphorylation-dependent factor CREB. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2(8), 599–609. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, P., et al. (2000). Signaling to chromatin through histone modifications. Cell, 103(2), 263–271. [CrossRef]

- Popkie, A. P., et al. (2010). Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling regulates DNA methylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 285(32), 24356–24364. [CrossRef]

- Karbiener, M., et al. (2011). Epigenetic regulation of GPR120 in obesity. Epigenetics, 6(7), 912–918. [CrossRef]

- Sato, N., et al. (2010). Epigenetic regulation of chemokine receptor expression. Journal of Immunology, 184(9), 4592–4600. [CrossRef]

- Neves, S. R., et al. (2002). G protein pathways. Science, 296(5573), 1636–1639. [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D., & Weinberg, R. A. (2011). Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell, 144(5), 646–674. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A. (2014). Epigenetic memory: The Lamarckian brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 15(4), 245–256. [CrossRef]

- Jones, P. A., et al. (2016). Targeting the cancer epigenome for therapy. Nature Reviews Genetics, 17(10), 630–641. [CrossRef]

- Stuart, T., & Satija, R. (2019). Integrative single-cell analysis. Nature Reviews Genetics, 20(5), 257–272. [CrossRef]

- Lymperopoulos, A., et al. (2013). Adrenergic receptor signaling in heart failure. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 138(2), 193–202. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., et al. (2002). CXCR4 overexpression promotes metastasis via β-arrestin signaling. Cancer Research, 62(21), 5925–5930. PMID: 12414634.

- Abd-Elrahman, K. S., & Ferguson, S. S. G. (2022). Modulation of mGluR signaling in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropharmacology, 202, 108860. [CrossRef]

- Violin, J. D., & Lefkowitz, R. J. (2007). β-arrestin-biased ligands at seven-transmembrane receptors. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 28(8), 416–422. [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, C. (2015). Defining cell types and states with single-cell genomics. Genome Research, 25(10), 1491–1498. [CrossRef]

- Kitano, H. (2002). Systems biology: A brief overview. Science, 295(5560), 1662–1664. [CrossRef]

- Hilton, I. B., & Gersbach, C. A. (2020). Enabling functional genomics with genome engineering. Nature Reviews Genetics, 21(3), 171–186. [CrossRef]

- Cordero, M. D., et al. (2018). AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) as a therapeutic target in metabolic diseases. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets, 22(12), 1031–1043. [CrossRef]

- Irannejad, R., et al. (2013). Conformational biosensors reveal GPCR signaling from endosomes. Nature, 495(7442), 534–538. [CrossRef]

- Hlavacek, W. S., & Faeder, J. R. (2009). Modeling signaling networks with rule-based approaches. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 10(11), 811–821. [CrossRef]

- Violin, J. D., et al. (2010). Biased ligands at angiotensin II receptors. Nature, 468(7325), 951–955. [CrossRef]

- Drucker, D. J. (2018). Mechanisms of action and therapeutic application of glucagon-like peptide-1. Cell Metabolism, 27(4), 740–756. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Rico M, Arasmou-Idrovo MS, Marín-Rodríguez B, Pascual-Guerra J. Fractal dimension reveals cellular morphological changes as early biomarkers in neurodegenerative diseases: A narrative review. NeuroMarkers 2025 2:100108. ISSN 2950-5887.

- Peavy GM, Jacobson MW, Salmon DP, Gamst AC, Patterson TL, Goldman S, Mills PJ, Khandrika S, Galasko D. The influence of chronic stress on dementia-related diagnostic change in older adults. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012 Jul-Sep;26(3):260-6. [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Villanueva M, Gómez-Ramírez J, Maestú F, Venero C, Ávila J, Fernández-Blázquez MA. The Role of Chronic Stress as a Trigger for the Alzheimer Disease Continuum. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020 Oct 22;12:561504. [CrossRef]

- Yashin AI, Wu D, Arbeev K, Bagley O, Akushevich I, Duan M, Yashkin A, Ukraintseva S. Interplay between stress-related genes may influence Alzheimer’s disease development: The results of genetic interaction analyses of human data. Mech Ageing Dev. 2021 Jun;196:111477. [CrossRef]

- Rezayof A, Sardari M, Hashemizadeh S. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of stress-induced memory impairment. Explor Neurosci. 2022;1:100–119. [CrossRef]

- Wallensten J, Ljunggren G, Nager A, Wachtler C, Bogdanovic N, Petrovic P, Carlsson AC. Stress, depression, and risk of dementia - a cohort study in the total population between 18 and 65 years old in Region Stockholm. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2023 Oct 2;15(1):161. [CrossRef]

- Bizzarri M, Giuliani A, Cucina A, D’Anselmi F, Soto AM, Sonnenschein C. Fractal analysis in a systems biology approach to cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2011 Jun;21(3):175-82. [CrossRef]

- Goldberger AL, Amaral LA, Hausdorff JM, Ivanov PCh, Peng CK, Stanley HE. Fractal dynamics in physiology: alterations with disease and aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002 Feb 19;99 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):2466-72. [CrossRef]

- Lambrou GI, Zaravinos A. Fractal dimensions of in vitro tumor cell proliferation. J Oncol. 2015;2015:698760. [CrossRef]

- Baish JW, Jain RK. Fractals and Cancer. Cancer Res (2000) 60 (14): 3683–3688.

- Zhang Z, Lee KCM, Siu DMD, Lo MCK, Lai QTK, Lam EY, Tsia KK. Morphological profiling by high-throughput single-cell biophysical fractometry. Commun Biol. 2023 Apr 24;6(1):449. [CrossRef]

- Lemberger T. Systems biology in human health and disease. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:136. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).