Submitted:

24 December 2025

Posted:

24 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Materials

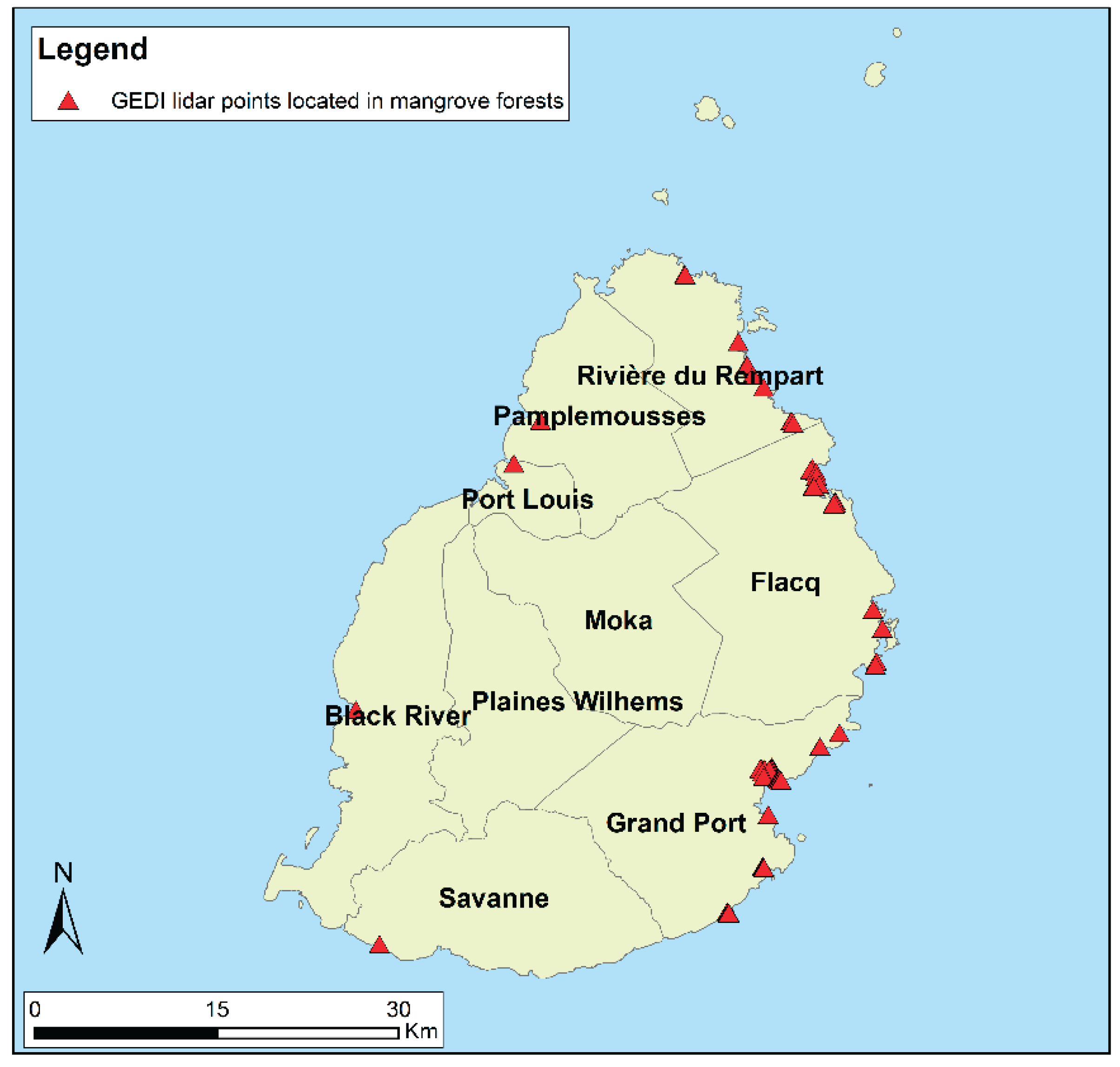

2.1. Study Area

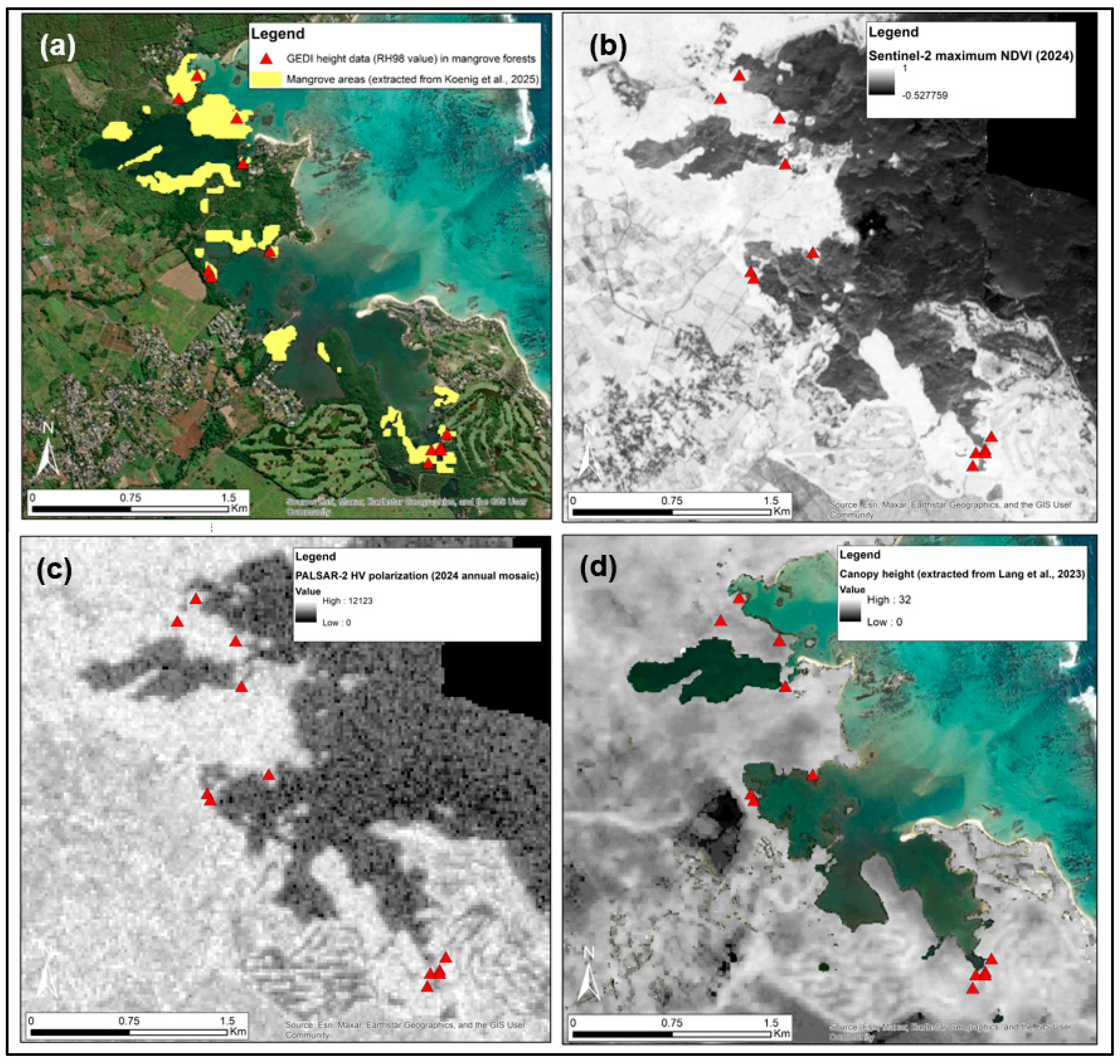

2.2. Datasets

2.3. Methodology

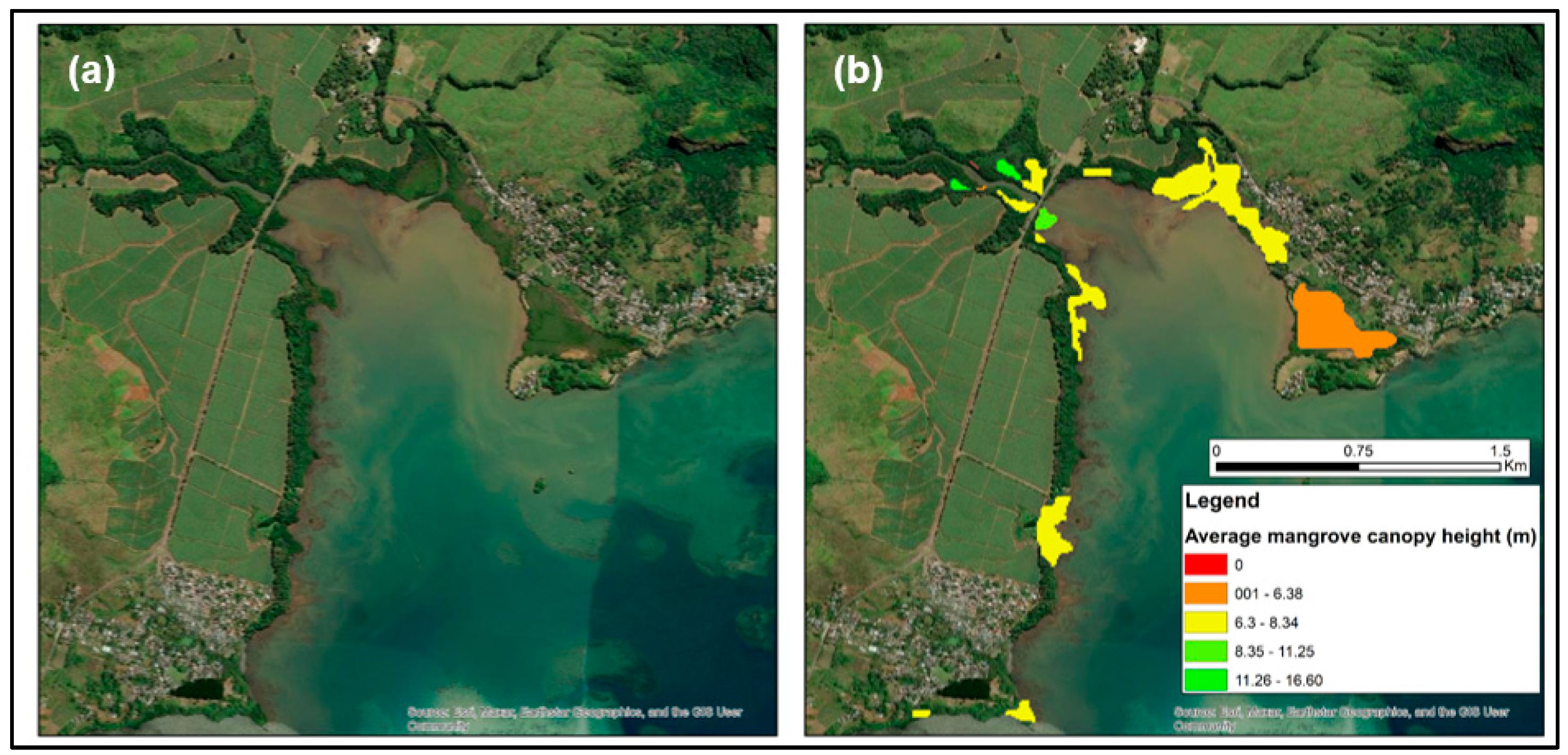

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

References

- United Nations, ‘Paris Agreement’. 2015. [Online]. Available: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf. 2015.

- CBD, ‘CBD/COP/15/L.25’. 2022. Accessed: Jan. 26, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.cbd.int/doc/c/e6d3/cd1d/daf663719a03902a9b116c34/cop-15-l-25-en.pdf.

- C. C. Jakovac et al., ‘Costs and Carbon Benefits of Mangrove Conservation and Restoration: A Global Analysis’, Ecological Economics, vol. 176, no. March, 2020. March. [CrossRef]

- B. A. Johnson, P. Kumar, N. Okano, R. Dasgupta, and B. R. Shivakoti, ‘Nature-based solutions for climate change adaptation: A systematic review of systematic reviews’, Nature-Based Solutions, vol. 2, p. 100042, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Kumano, M. Tamura, T. Inoue, and H. Yokoki, ‘Estimating the cost of coastal adaptation using mangrove forests against sea level rise’, Coastal Engineering Journal, vol. 63, no. 3, pp. 263–274, July 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Liu, K. Zhang, Y. Li, and L. Xie, ‘Numerical study of the sensitivity of mangroves in reducing storm surge and flooding to hurricane characteristics in southern Florida’, Continental Shelf Research, vol. 64, pp. 51–65, 2013. [CrossRef]

- R. Merven, C. Appadoo, V. Florens, and P. Iranah, ‘Dependency on mangroves ecosystem services is modulated by socioeconomic drivers and socio-ecological changes – insights from an insular biodiversity hotspot’, Human Ecology, vol. 51, no. 6, pp. 1141–1156, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Nesha, Y. A. Hussin, L. M. Van Leeuwen, and Y. B. Sulistioadi, ‘Modeling and mapping aboveground biomass of the restored mangroves using ALOS-2 PALSAR-2 in East Kalimantan, Indonesia’, International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, vol. 91, p. 102158, Sept. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Gupta and L. K. Sharma, ‘Mixed tropical forests canopy height mapping from spaceborne LiDAR GEDI and multisensor imagery using machine learning models’, Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment, vol. 27, p. 100817, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Santoro et al., ‘Design and performance of the Climate Change Initiative Biomass global retrieval algorithm’, Science of Remote Sensing, vol. 10, p. 100169, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Lang, W. Jetz, K. Schindler, and J. D. Wegner, ‘A high-resolution canopy height model of the Earth’, Nat Ecol Evol, vol. 7, no. 11, pp. 1778–1789, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Simard et al., ‘A New Global Mangrove Height Map with a 12 meter spatial resolution’, Sci Data, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 15, Jan. 2025. no. 1. [CrossRef]

- X. G. H. Koenig, P. N. K. Deenapanray, J.-L. Weber, S. Rakotondraompiana, and T. A. Ramihangihajason, ‘Are Neutrality Targets Alone Sufficient for Protecting Nature? Learning From Land Cover Change and Land Degradation Neutrality Targets in Mauritius’, Land Degradation & Development, vol. 36, no. n/a, pp. 265–280, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Republic of Mauritius, ‘Final Country Report of the LDN Target Setting Programme – Republic of Mauritius’. 2018. Accessed: Aug. 18, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.unccd.int/sites/default/files/ldn_targets/Mauritius%20LDN%20TSP%20Country%20Report.pdf.

- ‘Google Earth Engine’. Accessed: Aug. 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://earthengine.google.com/.

- L. Gao et al., ‘Remote sensing algorithms for estimation of fractional vegetation cover using pure vegetation index values: A review’, ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, vol. 159, pp. 364–377, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Q. Wang, S. Adiku, J. Tenhunen, and A. Granier, ‘On the relationship of NDVI with leaf area index in a deciduous forest site’, Remote Sensing of Environment, vol. 94, no. 2, pp. 244–255, Jan. 2005.

- L. Breiman, ‘Random Forests’, Machine Learning, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 5–32, 2001.

- M. Belgiu and L. Drăguţ, ‘Random forest in remote sensing: A review of applications and future directions’, ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, vol. 114, pp. 24–31, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- B. A. Johnson and Z. Xie, ‘Classifying a high resolution image of an urban area using super-object information’, ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, vol. 83, pp. 40–49, Sept. 2013.

- M. Hall, E. Frank, G. Holmes, B. Pfahringer, P. Reutemann, and I. H. Witten, ‘The WEKA Data Mining Software : An Update’, SIGKDD Explorations, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 10–18, 2009.

- R. Suwa et al., ‘Mangrove biomass estimation using canopy height and wood density in the South East and East Asian regions’, Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, vol. 248, p. 106937, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Ramdhun and C. Appadoo, ‘A contribution to understanding blue carbon sequestration and forest structure in mangroves of different ages in a small island ( Mauritius )’, Ocean Life, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 74–81, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. D. D. Doodee, S. D. D. V. Rughooputh, and S. Jawaheer, ‘Mangrove biomass productivity and sediment carbon storage assessment at selected sites in Mauritius: the effect of tidal inundation, forest age and mineral availability’, Environ. Res. Commun., vol. 7, no. 1, p. 015037, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Usage in this study |

| Sentinel-2 multispectral imagery |

To calculate maximum annual NDVI (normalized difference vegetation index) value for the year 2024 |

| PALSAR-2 annual mosaic imagery |

To extract SAR backscatter at 25m resolution in HH and HV polarizations for the year 2024 |

| PALSAR-2 ScanSAR imagery |

To extract median and maximum SAR backscatter at 60-100m resolution in HH and HV polarizations for the year 2024 |

| GEDI LIDAR data |

To extract LIDAR canopy height measurements of mangrove forests (Relative Height 98% metric) |

| Global canopy height map | As additional input variable for regression modeling, and for comparison with our regression modeling results |

| Map | Mean Absolute Error |

Root Mean Square Error |

R | R2 |

| Random Forest model output (this study) |

3.43 m | 4.45 m | 0.68 | 0.46 |

| Global canopy height map from [11] |

4.38 m | 5.33 m | n/a | n/a |

| Linear regression model output (this study) |

3.64 m | 4.84 m | 0.58 | 0.34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).