1. Introduction

The emergence of large language models (LLMs) has revolutionized artificial intelligence (AI) [

1,

2,

3], with models such as GPT-3 [

4], PaLM [

5], LLaMA [

6,

7,

8], and more recently trillion-parameter models like Megatron-Turing NLG [

9] pushing the boundaries of natural language understanding and generation. These models build upon the Transformer architecture [

10,

11], which has become the foundation of modern deep learning. Training these massive models presents unprecedented computational challenges that cannot be addressed by single-GPU training approaches.

Modern LLMs require substantial computational resources that far exceed the capabilities of individual accelerators. For instance, GPT-3 with 175 billion parameters requires approximately 314 ZFLOPs of computation for training [

4]. Research on compute-optimal training [

12] has further demonstrated the importance of scaling both model and data sizes appropriately. A single NVIDIA A100 GPU [

13] with 80GB memory can only accommodate models up to approximately 1-2 billion parameters when using standard training techniques. This fundamental limitation necessitates distributed training across multiple GPUs and compute nodes, as recognized in early work on distributed deep learning [

14].

The key challenges in distributed deep learning training span multiple dimensions. Memory constraints arise because model parameters, gradients, optimizer states, and activations must fit within GPU memory, yet modern models often exceed available capacity by orders of magnitude. Communication overhead becomes significant as synchronizing gradients and parameters across devices introduces latency that can dominate training time. Maintaining computational efficiency requires maximizing GPU utilization while minimizing idle time caused by synchronization barriers. Finally, scalability concerns emerge as systems must maintain efficiency when scaling from tens to thousands of devices.

This survey provides a comprehensive overview of distributed deep learning training technologies. We present a systematic taxonomy of parallelism strategies including data parallelism, tensor parallelism, pipeline parallelism, and hybrid approaches. We provide an in-depth analysis of major training frameworks including DeepSpeed, Megatron-LM, GPipe, and PyTorch FSDP. We offer a detailed examination of communication optimization techniques and collective operations. We present a comprehensive review of network interconnect technologies including NVLink, NVSwitch, InfiniBand, and RoCE. Finally, we provide practical guidelines for deploying distributed training systems.

The remainder of this survey is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces fundamental concepts and background knowledge.

Section 3 presents parallelism strategies in detail.

Section 4 analyzes major distributed training frameworks.

Section 5 discusses communication optimization techniques.

Section 6 examines network interconnect technologies.

Section 7 provides practical deployment guidelines.

Section 8 discusses future trends and open challenges. Finally,

Section 9 concludes this survey.

Table 1.

Technology stack for distributed deep learning training

Table 1.

Technology stack for distributed deep learning training

| Layer |

Representative Technologies |

| Applications |

LLM Training, Computer Vision |

| Training Frameworks |

DeepSpeed, Megatron-LM, FSDP, GPipe |

| Parallelism Strategies |

Data, Tensor, Pipeline, ZeRO |

| Communication Libraries |

NCCL, Gloo, MPI |

| Network Interconnects |

NVLink, InfiniBand, RoCE |

2. Preliminaries

This section introduces the fundamental concepts necessary for understanding distributed deep learning training, including the training process, memory consumption patterns, collective communication primitives, and the Transformer architecture that underlies modern large language models.

2.1. Deep Learning Training Overview

Training a deep neural network involves iteratively updating model parameters

to minimize a loss function

. The standard training procedure consists of four phases. In the forward pass, the model computes predictions

for input

x. The loss computation phase calculates

where

y is the ground truth label. During the backward pass, gradients

are computed via backpropagation through the computational graph. Finally, the parameter update phase modifies the weights according to

where

g represents the optimizer function such as SGD or Adam [

15]. Modern training typically employs mixed precision techniques [

16,

17] to reduce memory consumption and accelerate computation.

2.2. GPU Memory Consumption

During training, GPU memory is consumed by four main components. The total memory requirement can be expressed as:

For a model with parameters using mixed precision training with the Adam optimizer, the memory requirements break down as follows. Parameters require bytes when stored in FP16 format. Gradients similarly require bytes in FP16. The optimizer states demand bytes, comprising FP32 master parameters, momentum terms, and variance terms. Activation memory varies depending on batch size and sequence length, and can often dominate total memory consumption for large batch training.

Table 2 illustrates these memory requirements for models of varying sizes, demonstrating why distributed training becomes necessary as models scale beyond several billion parameters.

2.3. Collective Communication Primitives

Distributed training relies on collective communication operations to synchronize data across devices. The AllReduce operation aggregates data from all processes and distributes the result back to all processes. For

N processes each holding data of size

D, the Ring AllReduce algorithm achieves a communication volume of

, which approaches

as

N grows large, making it bandwidth-optimal. The AllGather operation collects data from all processes and delivers the complete dataset to every process, with each process

i contributing

bytes and receiving

bytes in total. The ReduceScatter operation combines reduction and scatter in a single collective, reducing data across all processes and distributing distinct portions of the result to each process.

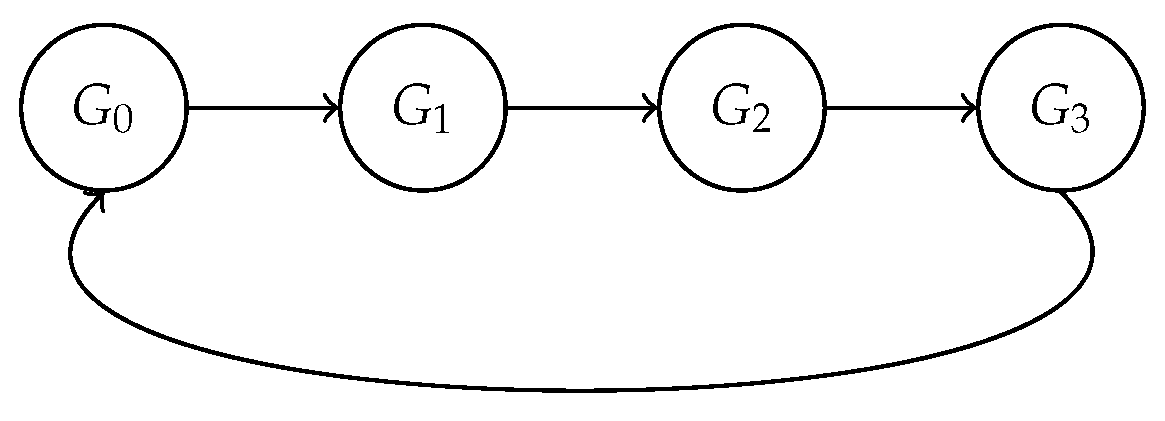

Figure 1 illustrates the Ring AllReduce communication pattern that forms the foundation of efficient gradient synchronization.

2.4. Transformer Architecture

Modern LLMs are predominantly based on the Transformer architecture [

10], which has become the de facto standard for sequence modeling tasks. A standard Transformer layer consists of a Multi-Head Attention (MHA) mechanism with computational complexity

and memory complexity

for sequence length

n and hidden dimension

d. Recent advances such as FlashAttention [

18] have improved the IO efficiency of attention computation. The Feed-Forward Network (FFN) comprises two linear transformations with a hidden dimension typically four times the model dimension. Layer normalization [

19] and residual connections [

20] stabilize training and enable gradient flow through deep networks.

The computational cost of training a Transformer with

L layers, hidden dimension

d, and sequence length

n on batch size

B is approximately:

This quadratic scaling with sequence length and the cubic scaling with model dimension underscore the computational demands of training modern language models.

3. Parallelism Strategies

This section presents the major parallelism strategies for distributed deep learning training, examining their mechanisms, trade-offs, and appropriate use cases.

3.1. Data Parallelism

Data parallelism (DP) is the most widely used parallelism strategy due to its simplicity and effectiveness [

21]. In this approach, each device holds a complete copy of the model and processes different data batches in parallel. After computing local gradients, devices synchronize through collective communication to ensure all replicas maintain identical parameters. Early work on large-scale SGD [

22] demonstrated that data parallelism can achieve near-linear scaling when properly configured.

3.1.1. Distributed Data Parallel

PyTorch’s Distributed Data Parallel (DDP) [

23] implements data parallelism with several key characteristics. Each GPU maintains a complete model replica with identical parameters. The input batch is split across GPUs, with each device processing a distinct subset of the data. Gradients computed during the backward pass are synchronized across all devices via the AllReduce collective operation, typically implemented using the bandwidth-optimal Ring AllReduce algorithm [

24]. Horovod [

25] pioneered this approach with efficient ring-based communication, achieving near-linear scaling to 512 GPUs. This synchronous approach ensures that all model replicas remain identical after each training iteration, guaranteeing reproducible training dynamics.

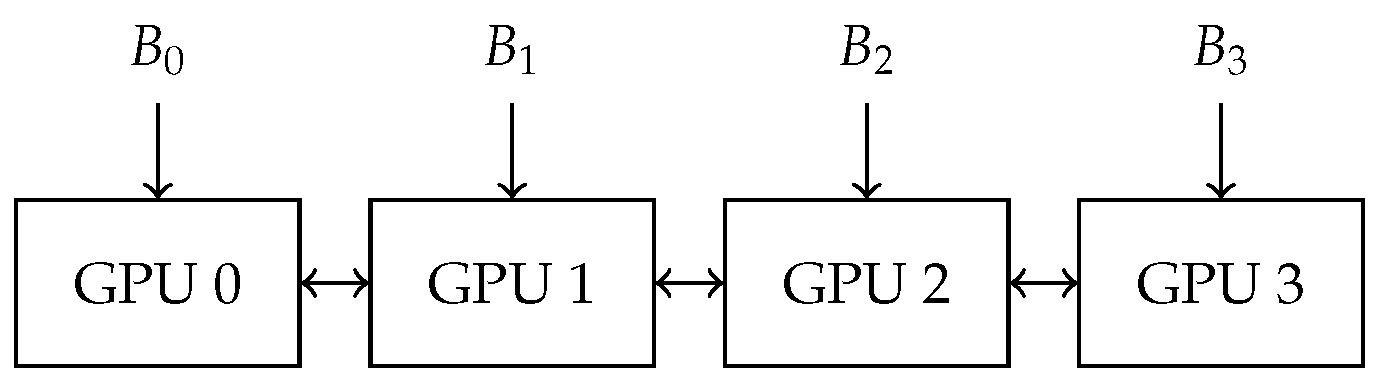

Figure 2 illustrates the data parallelism architecture, showing how data is distributed across GPUs while the model is replicated, with gradient synchronization occurring after the backward pass.

3.1.2. ZeRO: Zero Redundancy Optimizer

The Zero Redundancy Optimizer (ZeRO) [

26] addresses the memory inefficiency of standard data parallelism by partitioning model states across data parallel ranks rather than replicating them. ZeRO introduces three progressive optimization stages, each providing greater memory savings at the cost of increased communication.

ZeRO Stage 1 partitions only the optimizer states across devices. Since optimizer states typically consume the majority of memory in mixed-precision training with Adam, this single optimization reduces memory consumption by approximately 4× while maintaining the same communication volume as standard data parallelism.

ZeRO Stage 2 extends partitioning to include gradients in addition to optimizer states. Gradients are reduced and scattered rather than being replicated across all devices. This approach achieves approximately 8× memory reduction compared to standard data parallelism while still maintaining communication parity.

ZeRO Stage 3 partitions parameters, gradients, and optimizer states across all devices, achieving memory reduction proportional to the number of GPUs. However, this requires AllGather operations to reconstruct parameters before each forward and backward computation, increasing communication volume by approximately 1.5×.

Table 3 summarizes the memory and communication characteristics of each ZeRO stage.

3.2. Tensor Parallelism

Tensor parallelism (TP) [

27] partitions individual layers across multiple devices, enabling the training of layers that would otherwise exceed single-device memory capacity. For a linear layer computing

, the weight matrix

A can be partitioned either along columns or along rows, each approach offering different trade-offs.

In column parallelism, the weight matrix A is partitioned along its columns as , yielding the computation . Each device computes a portion of the output independently, and the results can be used directly by a subsequent row-parallel layer without communication.

In row parallelism, the weight matrix is partitioned along rows as , with the input correspondingly split. The computation becomes , requiring an AllReduce operation to sum the partial results.

Megatron-LM implements tensor parallelism for Transformer layers by applying column parallelism to the query, key, and value projections in attention, followed by row parallelism for the output projection. The MLP block uses column parallelism for the first linear layer and row parallelism for the second. This arrangement requires only two AllReduce operations per Transformer layer, minimizing communication overhead while enabling efficient parallelization of attention heads across devices.

3.3. Pipeline Parallelism

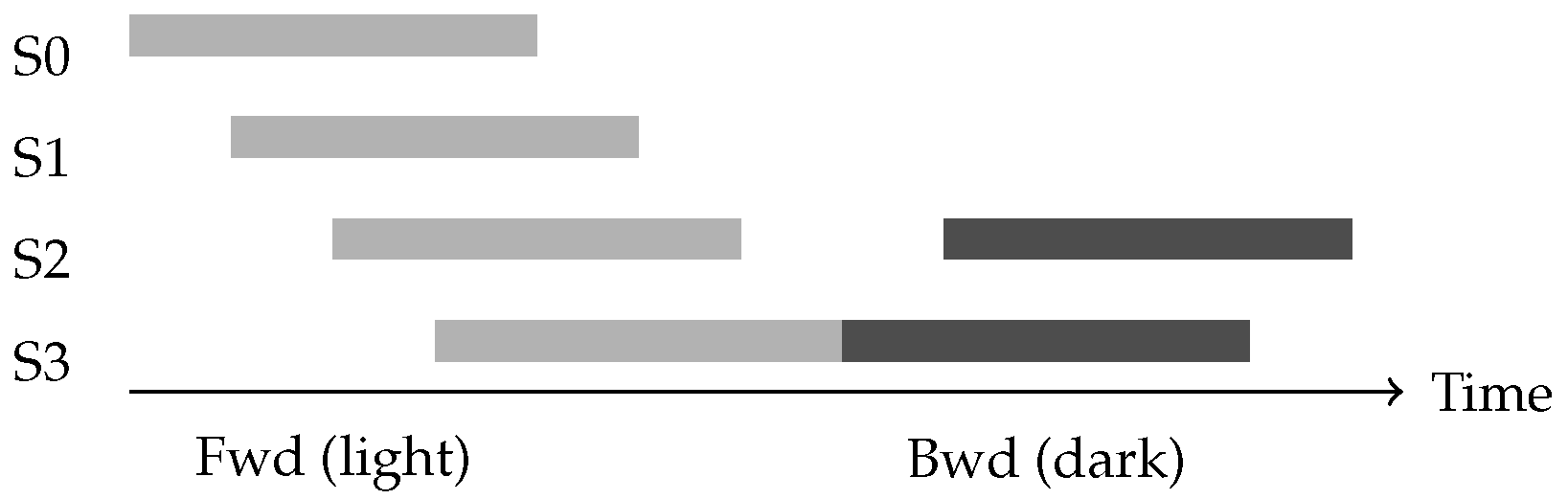

Pipeline parallelism (PP) partitions model layers across devices, with each device responsible for a contiguous subset of layers. Data flows through devices sequentially during the forward pass and in reverse during the backward pass. While conceptually simple, naive pipeline parallelism suffers from severe underutilization, as only one device is active at any time.

3.3.1. GPipe Schedule

GPipe [

28] introduced micro-batch pipelining to address the utilization problem. The approach splits each mini-batch into

M smaller micro-batches that flow through the pipeline in sequence. All forward passes complete before backward passes begin, maintaining synchronous gradient updates. The pipeline bubble ratio, representing the fraction of time devices remain idle, equals

where

P is the number of pipeline stages. Increasing the number of micro-batches reduces bubble overhead but requires storing activations for all in-flight micro-batches, increasing memory consumption.

3.3.2. 1F1B Schedule

PipeDream [

29] introduced the one-forward-one-backward (1F1B) schedule to reduce memory requirements. After an initial warm-up phase, each device alternates between forward and backward passes, limiting the number of in-flight micro-batches. This interleaved schedule achieves better memory efficiency than GPipe while maintaining similar throughput, as illustrated in

Figure 3.

3.4. Hybrid Parallelism

Modern large-scale training combines multiple parallelism strategies to leverage their complementary strengths. The combination of pipeline, tensor, and data parallelism, known as 3D parallelism or PTD-P [

30], has become the standard approach for training models with hundreds of billions of parameters.

In 3D parallelism, the total number of devices equals . Tensor parallelism is typically confined within a single node to exploit high-bandwidth NVLink interconnects, while pipeline parallelism spans across nodes where lower-bandwidth network connections can tolerate the point-to-point communication pattern. Data parallelism scales globally to increase effective batch size.

A typical configuration for training 175 billion parameter models on 1024 GPUs employs 8-way tensor parallelism within each node, 8-way pipeline parallelism across nodes, and 16-way data parallelism globally. This configuration achieved 52% of theoretical peak throughput on NVIDIA A100 clusters [

30]. PaLM [

5] achieved 57.8% hardware FLOPs utilization when training at 540B parameters on 6144 TPU v4 chips.

Table 4 summarizes the key characteristics of each parallelism strategy.

4. Distributed Training Frameworks

This section analyzes the major distributed training frameworks that have emerged to address the challenges of large-scale model training, examining their architectures, key innovations, and appropriate use cases.

4.1. DeepSpeed

DeepSpeed [

31] is Microsoft’s open-source deep learning optimization library that has become widely adopted for training large language models. The framework’s primary contribution is the ZeRO optimizer family, which enables memory-efficient distributed training without sacrificing computational performance. Memory optimization remains a critical concern in LLM training [

32], and DeepSpeed addresses this through systematic state partitioning.

4.1.1. ZeRO Optimizer Architecture

The ZeRO optimizer [

26] eliminates memory redundancy in data parallelism through systematic state partitioning. In standard data parallelism, each GPU maintains complete copies of model parameters, gradients, and optimizer states, resulting in significant memory redundancy. ZeRO addresses this inefficiency by partitioning these states across the data parallel group while maintaining the computational semantics of data parallelism.

The implementation employs careful orchestration of collective operations to reconstruct necessary states on demand. During the forward pass with ZeRO-3, parameters are gathered via AllGather immediately before computation and discarded afterward. Gradients are computed locally and then reduced via ReduceScatter, with each device retaining only its designated partition. This approach trades increased communication for dramatically reduced memory footprint, enabling the training of models that would otherwise require model parallelism.

4.1.2. ZeRO-Offload and ZeRO-Infinity

ZeRO-Offload [

33] extends the memory optimization by offloading optimizer states and gradients to CPU memory. The implementation carefully schedules data transfers to overlap with GPU computation, minimizing the performance impact of the slower CPU memory system. This approach enables training of 13 billion parameter models on a single GPU, democratizing access to large model training.

ZeRO-Infinity [

34] further extends offloading to NVMe storage, breaking through the CPU memory barrier. By leveraging the high bandwidth of modern NVMe drives and sophisticated prefetching strategies, ZeRO-Infinity enables training of models with over one trillion parameters on clusters of commodity hardware.

Table 5 compares the offloading capabilities of these approaches.

DeepSpeed also provides communication-efficient training through gradient compression techniques. The 1-bit Adam optimizer [

35] compresses gradients to single-bit representations, reducing communication volume by up to 26× while maintaining convergence comparable to standard Adam. ZeRO++ [

36] introduces hierarchical partitioning strategies that exploit the bandwidth hierarchy of modern clusters, reducing inter-node communication by keeping parameter partitions within nodes when possible.

4.2. Megatron-LM

Megatron-LM [

27,

30] is NVIDIA’s framework optimized for training large Transformer models. The framework pioneered efficient tensor parallelism implementations and has been used to train some of the largest language models.

4.2.1. Tensor Parallelism Implementation

Megatron-LM implements tensor parallelism with careful attention to minimizing communication overhead. For the self-attention mechanism, the query, key, and value projection matrices are partitioned by columns, allowing each device to compute attention for a subset of heads independently. The output projection uses row parallelism, requiring an AllReduce to combine partial results. The feed-forward network employs column parallelism for the first linear layer and row parallelism for the second, again requiring only a single AllReduce per sublayer.

This design achieves a critical property: the entire Transformer layer requires only two AllReduce operations regardless of the tensor parallelism degree. The AllReduce operations occur at natural synchronization points where the full tensor is needed, avoiding unnecessary communication for intermediate computations.

4.2.2. Pipeline Parallelism in Megatron-LM

Megatron-LM supports multiple pipeline parallelism schedules optimized for different scenarios. The 1F1B schedule reduces memory consumption by limiting in-flight micro-batches compared to GPipe’s approach of completing all forward passes before backward passes. The interleaved 1F1B schedule further reduces pipeline bubble by assigning multiple non-contiguous layer groups to each device, enabling more computation to overlap with communication.

The framework’s 3D parallelism implementation [

30] combines tensor, pipeline, and data parallelism in a carefully orchestrated manner. On a cluster of 1024 A100 GPUs with 8-way tensor parallelism, 8-way pipeline parallelism, and 16-way data parallelism, the system achieves 52% of theoretical peak throughput when training a model with one trillion parameters.

4.3. GPipe

GPipe [

28] pioneered micro-batch pipeline parallelism for training neural networks that exceed single-device memory capacity. While the framework predates the current generation of LLMs, its core ideas continue to influence modern training systems.

The key insight of GPipe is that pipeline efficiency improves with the ratio of micro-batches to pipeline stages. By dividing each mini-batch into many micro-batches, the pipeline bubble becomes a diminishing fraction of total training time. However, this comes at the cost of increased activation memory, as activations for all micro-batches must be retained until the corresponding backward passes complete.

GPipe addresses activation memory through re-materialization, also known as activation checkpointing. Rather than storing all intermediate activations, the framework discards them after the forward pass and recomputes them during the backward pass. This approach trades computation for memory, enabling 2.7× larger models on a single device at the cost of approximately 33% additional computation. Combined with pipeline parallelism across 128 partitions, GPipe enables training of models up to 83.9 billion parameters, representing a 298× increase compared to single-device training.

4.4. PyTorch FSDP

Fully Sharded Data Parallel (FSDP) [

37] is PyTorch’s native implementation of ZeRO-3-style parameter sharding. The framework provides a user-friendly API that integrates seamlessly with the PyTorch ecosystem while delivering memory efficiency comparable to DeepSpeed ZeRO-3.

FSDP implements a communication pattern that reconstructs parameters on demand and immediately discards them after use. Before each forward computation, the required parameters are gathered via AllGather. After the forward pass completes, non-owned parameter shards are released to free memory. The same pattern repeats during the backward pass, with an additional ReduceScatter operation to distribute gradient shards to their owning ranks.

The framework supports mixed precision training with configurable precision for computation, parameter storage, and gradient reduction. Activation checkpointing integrates naturally with the sharding mechanism, and the framework provides utilities for efficient model initialization from checkpoints without requiring full model materialization.

4.5. Framework Comparison

Table 6 summarizes the key features of each framework. DeepSpeed excels in memory optimization through its comprehensive ZeRO implementation and offloading capabilities. Megatron-LM provides highly optimized tensor and pipeline parallelism implementations tuned for NVIDIA hardware. GPipe’s micro-batch pipelining approach remains relevant for scenarios where pipeline parallelism is the primary scaling mechanism. FSDP offers the advantage of native PyTorch integration with competitive performance for ZeRO-style training.

The choice of framework depends on the specific requirements of the training task. For models requiring tensor parallelism with maximum performance on NVIDIA hardware, Megatron-LM remains the gold standard. For memory-constrained scenarios or heterogeneous hardware, DeepSpeed’s ZeRO and offloading capabilities provide the most flexibility. For teams already invested in the PyTorch ecosystem seeking a straightforward distributed training solution, FSDP offers an excellent balance of capability and usability.

4.6. Cluster Orchestration

Large-scale distributed training requires sophisticated cluster management to coordinate resources, schedule jobs, and handle failures across potentially thousands of GPUs.

Kubernetes has emerged as the dominant container orchestration platform for managing distributed training workloads in production environments. The platform provides declarative resource management, automatic scaling, and fault tolerance through pod restart mechanisms. However, the default Kubernetes scheduler lacks awareness of GPU topology and communication patterns critical for distributed training efficiency. Specialized schedulers such as Gandiva [

38] and Optimus [

39] address these limitations by incorporating GPU-aware scheduling decisions that consider factors like NVLink topology, network locality, and job interference patterns.

Ray [

40] provides a distributed computing framework designed specifically for machine learning workloads. Unlike Kubernetes which focuses on container orchestration, Ray offers native abstractions for distributed actors and tasks that simplify the implementation of training loops and hyperparameter search. Ray Train integrates with PyTorch and other frameworks to provide elastic training capabilities, allowing jobs to scale up or down based on resource availability without requiring manual intervention.

Kubeflow builds on Kubernetes to provide a complete machine learning platform including training operators for TensorFlow, PyTorch, and MXNet. The training operators manage the lifecycle of distributed training jobs, handling pod creation, service discovery, and coordinated startup across workers. The MPI Operator enables running distributed training jobs using the Message Passing Interface, supporting Horovod-based workloads on Kubernetes clusters.

4.7. Inference Optimization

While this survey focuses primarily on training, inference optimization represents an increasingly important area as deployed models serve millions of users. The techniques developed for efficient inference often inform training system design and vice versa.

vLLM [

41] introduces PagedAttention, an attention algorithm inspired by virtual memory paging that dramatically improves memory efficiency for LLM serving. Traditional inference systems allocate contiguous memory for the key-value (KV) cache of each request, leading to significant fragmentation as sequence lengths vary. PagedAttention partitions the KV cache into fixed-size blocks that can be stored non-contiguously, reducing memory waste to under 4% and enabling 2–4× higher throughput compared to prior systems like FasterTransformer.

Orca [

42] pioneered continuous batching for transformer inference, where new requests can join an ongoing batch as previous requests complete rather than waiting for the entire batch to finish. This approach significantly improves GPU utilization and reduces latency for variable-length generation tasks. Combined with iteration-level scheduling, continuous batching enables serving systems to achieve near-optimal hardware utilization even with heterogeneous request patterns.

Speculative decoding [

43] accelerates autoregressive generation by using a smaller draft model to propose multiple tokens that the larger target model verifies in parallel. When the draft model’s predictions align with what the target model would generate, multiple tokens can be accepted in a single forward pass, reducing the number of sequential model invocations required. This technique can provide 2–3× speedup for inference with minimal impact on output quality.

5. Communication Optimization

Efficient communication is critical for distributed training performance, as synchronization overhead can dominate training time at scale. This section examines communication optimization techniques that reduce this overhead while maintaining training convergence.

5.1. Collective Communication Libraries

The NVIDIA Collective Communications Library (NCCL) has become the de facto standard for GPU collective operations in distributed deep learning. NCCL implements topology-aware algorithms that automatically detect and exploit the bandwidth hierarchy of modern systems, selecting optimal communication paths through NVLink for intra-node communication and InfiniBand or Ethernet for inter-node transfers.

NCCL supports multiple algorithmic implementations for each collective operation, selecting among them based on message size and network topology. The Ring algorithm achieves bandwidth-optimal performance for large messages by organizing GPUs in a logical ring and pipelining data transfers. The Tree algorithm provides latency-optimal performance for small messages through hierarchical aggregation. For InfiniBand networks supporting SHARP (Scalable Hierarchical Aggregation and Reduction Protocol), NCCL can offload reduction operations to network switches, reducing both latency and host CPU overhead.

Table 7 summarizes the key collective operations and their communication volumes. The AllReduce operation, fundamental to gradient synchronization in data parallelism, achieves a communication volume of

using the Ring algorithm, where

D is the data size and

N is the number of participants. This approaches

for large

N, making AllReduce bandwidth-bound rather than latency-bound for typical gradient sizes.

5.2. Gradient Compression

Gradient compression techniques reduce communication volume by transmitting approximate gradients, trading some accuracy for significant bandwidth savings. These approaches have proven particularly valuable for training over bandwidth-constrained networks.

Quantization methods reduce the precision of gradient representations. The 1-bit Adam optimizer [

35] compresses gradients to single-bit signs, achieving up to 32× compression compared to FP32 gradients. QSGD [

44] provides a theoretical framework for quantized gradient communication with provable convergence guarantees. The method employs error feedback to accumulate quantization errors and correct them in subsequent iterations, maintaining convergence comparable to full-precision training. More recent work on FP8 communication achieves 2× compression with minimal accuracy impact, providing a practical middle ground between compression ratio and training stability.

Sparsification methods transmit only the most significant gradient elements. Top-K sparsification [

45,

46] selects the K% largest gradient magnitudes for communication, achieving compression ratios of 100× or more. Error feedback mechanisms accumulate the residual gradients that were not transmitted, ensuring that all gradient information eventually propagates to the model. This approach requires careful tuning of the sparsity ratio to balance communication savings against potential convergence degradation.

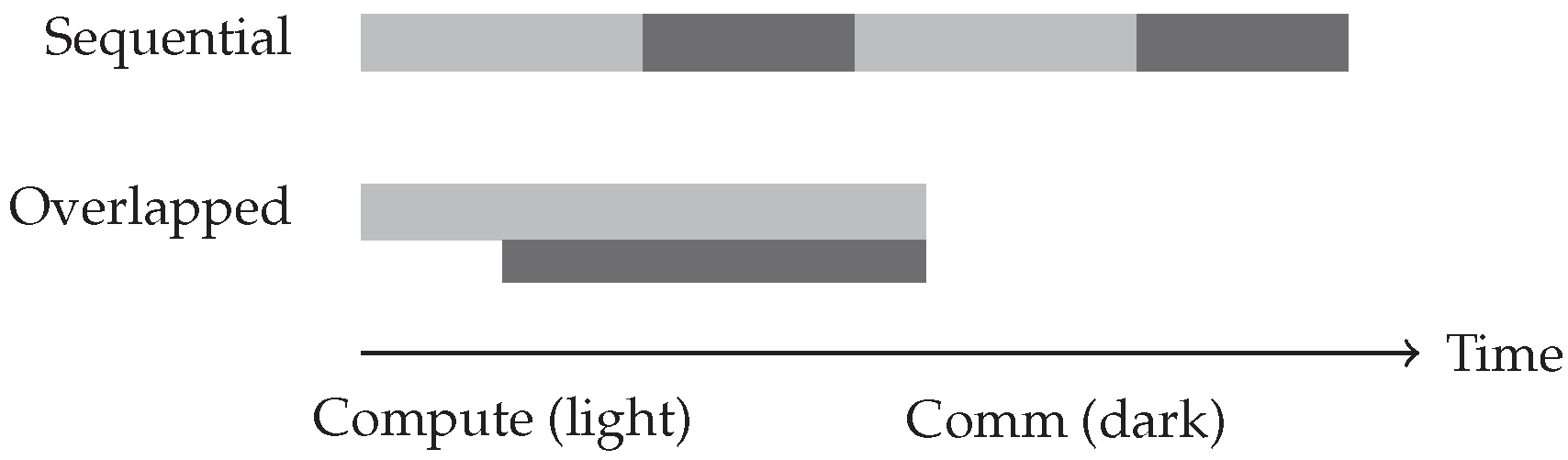

5.3. Computation-Communication Overlap

Overlapping computation with communication hides communication latency by performing both activities concurrently. This optimization is essential for achieving high efficiency in distributed training.

Gradient bucketing, implemented in PyTorch DDP, groups gradients into buckets that trigger AllReduce operations when filled. As the backward pass progresses through model layers, earlier layers’ gradients become available while later layers are still computing. By initiating AllReduce for completed buckets while backward computation continues, the communication time overlaps with computation time. The bucket size represents a trade-off: larger buckets improve AllReduce efficiency but delay communication initiation, while smaller buckets enable earlier overlap but incur per-bucket overhead.

Parameter prefetching in FSDP and ZeRO-3 overlaps AllGather operations with computation. While the current layer computes using its gathered parameters, the system initiates AllGather for the next layer’s parameters. This pipelining ensures that parameters are available when needed without blocking on communication. Effective prefetching requires careful memory management to accommodate the additional parameters in flight and accurate prediction of layer execution order.

Figure 4 illustrates how computation-communication overlap reduces total execution time compared to sequential execution, demonstrating the performance benefit of these techniques.

5.4. Hierarchical Communication

Large clusters exhibit a pronounced bandwidth hierarchy, with intra-node communication via NVLink offering 5-10× higher bandwidth than inter-node communication via InfiniBand or Ethernet. Hierarchical communication strategies exploit this structure to minimize data movement across slower network links.

Two-level AllReduce implements gradient synchronization in two phases. First, GPUs within each node perform a local reduction using high-bandwidth NVLink, producing a single gradient tensor per node. Second, nodes perform inter-node AllReduce using the network fabric, communicating N-fold less data than a flat AllReduce where N is the number of GPUs per node. Finally, the reduced result is broadcast within each node. This approach significantly reduces network traffic for clusters with many GPUs per node.

ZeRO++ [

36] extends hierarchical optimization to parameter sharding. The hierarchical parameter partitioning (hpZ) feature maintains secondary parameter copies within each node, enabling intra-node AllGather operations that avoid inter-node communication during forward and backward passes. Quantized weight communication (qwZ) further reduces inter-node traffic by communicating lower-precision parameter copies. These optimizations can reduce inter-node communication by 4× compared to standard ZeRO-3, with modest memory overhead from the secondary copies.

Table 8 summarizes the communication optimization techniques, their typical reduction factors, and associated trade-offs that practitioners must consider when selecting optimization strategies.

6. Network Interconnects

Network interconnects significantly impact distributed training performance, as communication efficiency directly affects scalability and throughput [

47]. This section examines the key interconnect technologies at both intra-node and inter-node levels, which are fundamental to GPU-accelerated computing [

48].

6.1. Intra-Node Interconnects

Modern GPU servers employ specialized interconnects to enable high-bandwidth communication between GPUs within a single node, as standard PCIe connections prove insufficient for the communication demands of distributed training.

PCI Express remains the baseline interconnect between GPUs and CPUs, with each generation doubling bandwidth. PCIe 4.0 provides 2 GB/s per lane, yielding 64 GB/s for a x16 connection, while PCIe 5.0 doubles this to 128 GB/s. However, even the latest PCIe generations cannot match the bandwidth requirements of tensor parallelism, where GPUs must exchange activations at every layer.

NVLink [

49,

50] addresses this limitation by providing direct high-bandwidth connections between GPUs. The technology has evolved significantly across GPU generations, as shown in

Table 9. The Volta architecture introduced NVLink 2.0 with 300 GB/s bidirectional bandwidth, Ampere increased this to 600 GB/s with NVLink 3.0, and Hopper achieved 900 GB/s with NVLink 4.0. The forthcoming Blackwell architecture doubles bandwidth again to 1.8 TB/s with NVLink 5.0, representing a 6× improvement over the first generation.

NVSwitch extends NVLink connectivity to enable all-to-all communication between GPUs within a node. Without NVSwitch, NVLink connections form a partial mesh where each GPU connects directly to only some neighbors. NVSwitch provides a non-blocking crossbar that allows any GPU to communicate with any other GPU at full bandwidth simultaneously. In DGX H100 systems, third-generation NVSwitch enables all eight GPUs to communicate at 900 GB/s each, providing an aggregate bisection bandwidth of 3.6 TB/s. This capability proves essential for tensor parallelism, where all-to-all communication patterns arise from attention computations.

6.2. Inter-Node Interconnects

Inter-node communication traverses the datacenter network, where InfiniBand and RDMA over Converged Ethernet (RoCE) represent the dominant technologies for high-performance AI training clusters.

InfiniBand [

51,

52] has long been the preferred interconnect for high-performance computing due to its low latency, high bandwidth, and native RDMA support. The technology continues to evolve, with EDR providing 100 Gb/s, HDR reaching 200 Gb/s, and NDR achieving 400 Gb/s per port. The upcoming XDR generation targets 800 Gb/s, maintaining InfiniBand’s position at the performance frontier. Beyond raw bandwidth, InfiniBand provides hardware-based congestion control that maintains performance under heavy load, and SHARP enables in-network reduction operations that offload collective communication from hosts.

RoCE [

53] enables RDMA capabilities over standard Ethernet infrastructure, providing an alternative to InfiniBand with potentially lower cost and simpler integration with existing datacenter networks. RoCE v1 operates at Layer 2 and is limited to a single broadcast domain, while RoCE v2 encapsulates RDMA in UDP packets, enabling routing across Layer 3 networks. RoCE requires Priority Flow Control (PFC) and Explicit Congestion Notification (ECN) for lossless operation, adding configuration complexity compared to InfiniBand’s integrated congestion management.

Table 10 compares InfiniBand and RoCE across key dimensions. InfiniBand offers lower latency and proven scalability to tens of thousands of GPUs but requires dedicated infrastructure and specialized expertise. RoCE provides comparable bandwidth at lower cost by leveraging existing Ethernet infrastructure, making it attractive for organizations with established Ethernet operations teams.

GPUDirect RDMA enables direct data transfer between GPU memory and the network adapter, bypassing CPU involvement and system memory copies. This capability reduces latency and CPU overhead for inter-node GPU communication. Both InfiniBand and RoCE support GPUDirect RDMA, and the technology has become essential for efficient multi-node training where frequent GPU-to-GPU communication across nodes occurs.

6.3. Large-Scale Network Architectures

Production AI training clusters employ carefully designed network topologies to provide sufficient bandwidth for distributed training workloads while managing cost and complexity.

The fat-tree topology, based on Clos network principles, remains the standard architecture for large-scale clusters. In a two-tier fat-tree, leaf switches connect directly to servers while spine switches provide full-mesh connectivity between leaf switches. This topology offers full bisection bandwidth, meaning aggregate bandwidth between any two halves of the cluster equals the aggregate server uplink bandwidth. Three-tier designs extend this architecture for larger deployments.

Meta’s AI training clusters [

53] demonstrate RoCE deployment at scale for production workloads. The architecture employs a two-tier Clos topology organized into AI Zones, with Rack Training Switches (RTSW) serving as leaf switches connected to servers via copper DAC cables. The design supports 400 Gb/s links with RoCE v2 transport, and implements receiver-driven flow control to manage congestion for collective communication patterns. This infrastructure supports training of the Llama model family and diverse production workloads including ranking, recommendation, and natural language processing.

Table 11 provides a comprehensive comparison of interconnect technologies across the full hierarchy from GPU-to-GPU within a node to inter-node communication, highlighting the order-of-magnitude bandwidth differences that motivate hierarchical communication strategies.

7. Practical Guidelines

This section provides practical guidance for deploying distributed training systems, drawing on the technical foundations established in previous sections to offer concrete recommendations for hardware selection, parallelism configuration, and performance optimization.

7.1. Hardware Selection

The choice of GPU hardware fundamentally shapes the distributed training architecture.

Table 12 compares current-generation GPUs across key specifications relevant to large model training. Memory capacity determines the maximum model size that can be accommodated with various parallelism strategies, while interconnect bandwidth influences the efficiency of tensor parallelism and other communication-intensive approaches.

System configuration significantly impacts achievable parallelism strategies. DGX-class systems provide 8 GPUs with NVSwitch interconnect and multiple high-bandwidth network interfaces, enabling efficient tensor parallelism within the node and pipeline or data parallelism across nodes. Cloud instances vary in their GPU count and interconnect capabilities, requiring careful matching of parallelism strategy to available hardware topology.

7.2. Parallelism Strategy Selection

Selecting appropriate parallelism strategies requires balancing model requirements against hardware capabilities. The decision framework in Figure

Table 13 provides a starting point, but optimal configuration often requires empirical evaluation.

For models under 1 billion parameters, standard data parallelism via DDP provides the simplest and most efficient solution. The entire model fits comfortably in GPU memory with room for large batch sizes, and communication overhead remains manageable.

Models between 1 and 10 billion parameters benefit from ZeRO-2, which partitions gradients and optimizer states while keeping parameters replicated. This configuration reduces memory consumption approximately 8× without increasing communication volume, often enabling single-GPU-per-model training that would otherwise require tensor parallelism.

Larger models between 10 and 50 billion parameters typically require tensor parallelism to fit within node memory, combined with ZeRO-1 or ZeRO-2 for optimizer state efficiency. Tensor parallelism degree should match the number of attention heads divisible by the chosen degree, commonly 2, 4, or 8 for models with 32 or 64 attention heads.

Models exceeding 50 billion parameters require 3D parallelism combining tensor, pipeline, and data parallelism.

Table 14 summarizes recommended configurations based on model scale and deployment scenario.

7.3. Configuration Guidelines

Tensor parallelism configuration requires attention to hardware topology. The tensor parallel degree should not exceed the number of GPUs connected via NVLink within a node, as crossing node boundaries dramatically increases communication latency. The degree must divide the number of attention heads evenly, and common configurations use TP=8 for 8-GPU nodes with models having 32, 64, or 128 attention heads.

Pipeline parallelism configuration balances bubble overhead against memory efficiency. The number of micro-batches should exceed 4× the number of pipeline stages to limit bubble ratio below 25%. Layers should be distributed to balance computation time across stages, accounting for differences between attention and feed-forward layers.

ZeRO configuration presents a trade-off between memory savings and communication overhead. ZeRO-1 adds minimal overhead while reducing optimizer memory 4×, making it appropriate when optimizer states dominate memory consumption. ZeRO-2 extends savings to 8× without increasing communication and suits most large model training scenarios. ZeRO-3 provides maximum memory efficiency but increases communication 1.5× and should be reserved for memory-constrained situations where other approaches prove insufficient.

7.4. Performance Monitoring

Effective distributed training requires continuous monitoring of system behavior to identify bottlenecks and optimization opportunities. GPU utilization and memory consumption reveal whether computation fully occupies available resources or stalls waiting for communication. Throughput metrics in samples or tokens per second provide the primary measure of training efficiency. The ratio of communication time to computation time indicates whether communication has become the bottleneck, suggesting opportunities for overlap optimization or compression techniques.

Table 15 summarizes common distributed training issues and their typical resolutions, providing a troubleshooting reference for practitioners encountering problems during deployment.

8. Future Trends and Open Challenges

This section discusses emerging trends and open research challenges in distributed deep learning training, examining how the field continues to evolve in response to growing model scales and new architectural paradigms.

8.1. Emerging Training Paradigms

The demands of next-generation models are driving the development of new training paradigms that address limitations of current approaches.

Ultra-long sequence training presents significant challenges as context lengths extend beyond 100,000 tokens. Memory requirements scale quadratically with sequence length in standard attention mechanisms, quickly exhausting available GPU memory even for moderately sized models. Sequence parallelism [

54,

55] and ring attention techniques distribute the sequence dimension across devices, enabling training with context lengths that would be impossible on single devices. Context parallelism represents a distinct form of parallelism that partitions the sequence dimension independently of model parallelism, requiring careful coordination to maintain attention computation correctness across sequence boundaries.

Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architectures [

56,

57] enable scaling to trillions of parameters while maintaining manageable computational costs by activating only a subset of parameters for each input. These architectures introduce expert parallelism as a new dimension, distributing experts across devices and routing tokens dynamically based on learned gating functions. The all-to-all communication required for token routing creates new bottlenecks, and load imbalance across experts can significantly reduce hardware utilization. Auxiliary losses and routing constraints help mitigate these challenges but introduce additional hyperparameters requiring careful tuning.

Multimodal training combines diverse data types including text, images, video, and audio within unified model architectures. These models require flexible batching strategies to handle inputs of varying sizes and computational requirements. Cross-modal attention mechanisms increase communication demands, and different modalities may benefit from different parallelism configurations, complicating the optimization of training efficiency.

8.2. Hardware Evolution

Hardware advances continue to reshape the distributed training landscape, with both incremental improvements and architectural innovations expanding the design space.

Next-generation interconnects promise substantial bandwidth improvements. NVLink 5.0 in the Blackwell architecture achieves 1.8 TB/s bidirectional bandwidth per GPU, doubling the previous generation and enabling more aggressive tensor parallelism strategies. The NVLink Switch extends NVLink connectivity beyond a single node, enabling all-to-all communication among up to 576 GPUs at NVLink bandwidth rather than network bandwidth. These capabilities may fundamentally alter the optimal balance between tensor, pipeline, and data parallelism for future systems.

Heterogeneous computing architectures combine GPUs with CPUs, specialized accelerators, and disaggregated memory systems. Training systems may leverage different device types for different operations, using GPUs for matrix operations while offloading embedding lookups to CPUs or memory-centric accelerators. Near-memory and in-network computing approaches move computation closer to data, potentially reducing data movement for certain operations.

8.3. Software and Algorithmic Advances

Software innovations complement hardware advances in improving distributed training efficiency.

Automatic parallelism systems like Alpa [

58] eliminate the need for manual parallelism configuration by automating strategy selection through compiler-based analysis. These systems construct cost models for different parallelism choices based on computation graphs and hardware characteristics, then search the configuration space to identify near-optimal strategies. As model architectures grow more complex and hardware becomes more heterogeneous, automatic parallelism becomes increasingly valuable for achieving good performance without expert tuning.

Elastic training enables dynamic scaling of training jobs in response to resource availability. Systems can add or remove nodes during training without requiring restarts, adapting to the fluid resource environment of cloud computing. Fault tolerance through checkpoint-restart and more advanced techniques like redundant computation ensures training progress survives individual node failures in large clusters where failures become statistically common. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning methods such as LoRA have emerged as important techniques for adapting large pretrained models while reducing computational requirements. Knowledge distillation provides another avenue for creating smaller, efficient models from larger teacher models.

8.4. Open Challenges

Despite significant progress, several fundamental challenges remain in distributed deep learning training.

Scalability challenges emerge as training scales to tens of thousands of GPUs. Communication overhead grows with cluster size, eventually dominating computation time for certain operations. Load imbalance becomes more pronounced with heterogeneous workloads and dynamic routing in MoE models. Synchronization barriers introduce idle time that reduces efficiency, and fault tolerance requirements increase as the probability of component failure grows with system size.

Efficiency gaps between achieved and theoretical performance remain substantial. Current systems typically achieve 30-50% of peak hardware throughput, leaving significant room for optimization. Memory fragmentation from dynamic workloads wastes capacity, and energy consumption at scale raises sustainability concerns.

Usability challenges impede broader adoption of distributed training. The configuration space for parallelism strategies is complex, with interactions between parameters that make manual tuning difficult. Debugging distributed systems requires specialized tools and expertise. Reproducibility across different hardware configurations presents difficulties when training runs cannot be exactly replicated.

Table 16 summarizes the key research directions and their associated challenges, highlighting areas where continued innovation is most needed.

9. Conclusion

This survey has provided a comprehensive examination of distributed deep learning training technologies, spanning parallelism strategies, training frameworks, communication optimization, and network interconnects. As language models continue to scale toward trillions of parameters, these technologies have become essential for advancing the state of the art in artificial intelligence.

The parallelism strategies examined in this survey each address different aspects of the distributed training challenge. Data parallelism remains the foundation of distributed training due to its simplicity and efficiency, with ZeRO optimizations enabling memory-efficient variants that scale to models previously requiring model parallelism. Tensor parallelism enables training of individual layers that exceed single-device memory capacity, with Megatron-LM’s implementation achieving minimal communication overhead through careful operator partitioning. Pipeline parallelism provides a mechanism for scaling across nodes with limited bandwidth, trading pipeline bubble overhead for reduced communication requirements. The combination of these approaches in 3D parallelism has enabled training of the largest models to date.

The training frameworks analyzed provide the practical implementations of these parallelism strategies. DeepSpeed excels in memory optimization through its comprehensive ZeRO implementation and heterogeneous offloading capabilities, democratizing access to large model training. Megatron-LM provides highly optimized tensor and pipeline parallelism implementations that achieve state-of-the-art throughput on NVIDIA hardware. PyTorch FSDP offers native integration with the PyTorch ecosystem while delivering competitive memory efficiency.

Communication optimization techniques prove essential for maintaining efficiency at scale. Gradient compression through quantization and sparsification can reduce communication volume by orders of magnitude, enabling training over bandwidth-constrained networks. Computation-communication overlap hides latency by executing both activities concurrently. Hierarchical communication strategies exploit the bandwidth hierarchy of modern systems to minimize data movement across slower network links.

Network interconnects establish the physical foundation for distributed training. NVLink and NVSwitch provide the high-bandwidth intra-node connectivity required for efficient tensor parallelism. InfiniBand remains the gold standard for inter-node communication in high-performance clusters, while RoCE emerges as a cost-effective alternative that leverages existing Ethernet infrastructure. The bandwidth hierarchy from NVLink to network interconnects motivates many of the parallelism and communication design choices.

For practitioners deploying distributed training systems, several recommendations emerge from this analysis. Initial efforts should focus on data parallelism with ZeRO optimizations before introducing model parallelism, as the former provides memory savings without requiring architectural changes to training code. Tensor parallelism should remain within NVLink-connected GPUs to exploit high-bandwidth interconnects, while pipeline parallelism provides a mechanism for cross-node scaling where network bandwidth is limited. Continuous monitoring of GPU utilization, communication overhead, and throughput metrics enables identification of optimization opportunities.

The field continues to evolve rapidly in response to growing model scales and new architectural paradigms. Ultra-long sequence training, mixture-of-experts architectures, and multimodal models present new challenges that current systems only partially address. Hardware advances including next-generation interconnects and heterogeneous computing architectures expand the design space for future training systems. Automatic parallelism and elastic training represent promising software directions for improving both efficiency and usability.

Despite significant progress, substantial challenges remain. Achieving efficient training at scales of tens of thousands of GPUs requires continued innovation in communication algorithms and fault tolerance mechanisms. Closing the gap between achieved and theoretical performance demands better understanding of system bottlenecks and more sophisticated optimization techniques. Improving usability through automation and better tooling will broaden access to distributed training capabilities.

As artificial intelligence continues its rapid advance, distributed training technologies will remain critical infrastructure enabling the development of increasingly capable models. The foundations established by the systems, algorithms, and hardware examined in this survey provide the basis for continued progress toward more efficient and accessible large-scale model training.

References

- Yu, Z. AI for science: A comprehensive review on innovations, challenges, and future directions. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence for Science (IJAI4S) 2025, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Idris, M.Y.I.; Wang, P.; Qureshi, R. CoTextor: Training-free modular multilingual text editing via layered disentanglement and depth-aware fusion. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS Creative AI Track, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Idris, M.Y.I.; Wang, P. Visualizing our changing Earth: A creative AI framework for democratizing environmental storytelling through satellite imagery. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS Creative AI Track, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhery, A.; Narang, S.; Devlin, J.; Bosma, M.; Mishra, G.; Roberts, A.; Barham, P.; Chung, H.W.; Sutton, C.; Gehrmann, S.; et al. PaLM: Scaling Language Modeling with Pathways. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.02311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Roziere, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. Llama: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.13971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; Martin, L.; Stone, K.; Albert, P.; Almahairi, A.; Babaei, Y.; Bashlykov, N.; Batra, S.; Bhargava, P.; Bhosale, S.; et al. Llama 2: Open Foundation and Fine-Tuned Chat Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.09288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grattafiori, A.; Dubey, A.; Jauhri, A.; et al. The Llama 3 Herd of Models. arXiv 2024. arXiv:2407.21783. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Patwary, M.; Norick, B.; LeGresley, P.; Rajbhandari, S.; Casper, J.; Liu, Z.; Prabhumoye, S.; Zerveas, G.; Korthikanti, V.; et al. Using DeepSpeed and Megatron to Train Megatron-Turing NLG 530B, A Large-Scale Generative Language Model. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.11990. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Wang, J.; Chen, H.; Idris, M.Y.I. QRS-Trs: Style transfer-based image-to-image translation for carbon stock estimation in quantitative remote sensing. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 52726–52737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, J.; Borgeaud, S.; Mensch, A.; Buchatskaya, E.; Cai, T.; Rutherford, E.; de Las Casas, D.; Hendricks, L.A.; Welbl, J.; Clark, A.; et al. Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.15556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NVIDIA. NVIDIA A100 Tensor Core GPU Architecture. 2020. Available online: https://www.nvidia.com/en-us/data-center/a100/.

- Dean, J.; Corrado, G.; Monga, R.; Chen, K.; Devin, M.; Mao, M.; Ranzato, M.; Senior, A.; Tucker, P.; Yang, K.; et al. Large Scale Distributed Deep Networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2012, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Micikevicius, P.; Narang, S.; Alben, J.; Diamos, G.; Elsen, E.; Garcia, D.; Ginsburg, B.; Houston, M.; Kuchaiev, O.; Venkatesh, G.; et al. Mixed Precision Training. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kalamkar, D.; Mudigere, D.; Mellempudi, N.; Das, D.; Banerjee, K.; Avancha, S.; Vooturi, D.T.; Jammalamadaka, N.; Huang, J.; Yuen, H.; et al. A Study of BFLOAT16 for Deep Learning Training. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.12322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, T.; Fu, D.Y.; Ermon, S.; Rudra, A.; Ré, C. FlashAttention: Fast and Memory-Efficient Exact Attention with IO-Awareness. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 16344–16359. [Google Scholar]

- Ba, J.L.; Kiros, J.R.; Hinton, G.E. Layer Normalization. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1607.06450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition; 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Verbraeken, J.; Wolting, M.; Katzy, J.; Kloppenburg, J.; Verbelen, T.; Rellermeyer, J.S. A Survey on Distributed Machine Learning. ACM Computing Surveys 2020, 53, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, P.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; Noordhuis, P.; Wesolowski, L.; Kyrola, A.; Tulloch, A.; Jia, Y.; He, K. Accurate, Large Minibatch SGD: Training ImageNet in 1 Hour. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.02677. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Zhao, Y.; Varma, R.; Salpekar, O.; Noordhuis, P.; Li, T.; Paszke, A.; Smith, J.; Vaughan, B.; Damania, P.; et al. PyTorch Distributed: Experiences on Accelerating Data Parallel Training. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment 2020, Vol. 13, 3005–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patarasuk, P.; Yuan, X. Bandwidth Optimal All-reduce Algorithms for Clusters of Workstations. Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing 2009, 69, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergeev, A.; Del Balso, M. Horovod: fast and easy distributed deep learning in TensorFlow. In proceedings of the. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.05799. [Google Scholar]

- Rajbhandari, S.; Rasley, J.; Ruwase, O.; He, Y. ZeRO: Memory Optimizations Toward Training Trillion Parameter Models. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1910.02054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoeybi, M.; Patwary, M.; Puri, R.; LeGresley, P.; Casper, J.; Catanzaro, B. Megatron-LM: Training Multi-Billion Parameter Language Models Using Model Parallelism. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.08053. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Bapna, A.; Firat, O.; Chen, M.X.; Chen, D.; Lee, H.; Ngiam, J.; Le, Q.V.; Wu, Y.; et al. GPipe: Efficient Training of Giant Neural Networks using Pipeline Parallelism. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2019; Vol. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, D.; Harlap, A.; Phanishayee, A.; Seshadri, V.; Devanur, N.R.; Ganger, G.R.; Gibbons, P.B.; Zaharia, M. PipeDream: Generalized Pipeline Parallelism for DNN Training. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 27th ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, 2019; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, D.; Shoeybi, M.; Casper, J.; LeGresley, P.; Patwary, M.; Korthikanti, V.; Vainbrand, D.; Kasber, P.; Hennigen, L.; Catanzaro, B. Efficient Large-Scale Language Model Training on GPU Clusters Using Megatron-LM. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis (SC), 2021; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rasley, J.; Rajbhandari, S.; Ruwase, O.; He, Y. DeepSpeed: System Optimizations Enable Training Deep Learning Models with Over 100 Billion Parameters. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 2020; pp. 3505–3506. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Bi, Z.; Niu, Q.; Liu, J.; Peng, B.; Zhang, S.; Liu, M.; Li, M.; Pan, X.; Xu, J.; et al. Deep learning and machine learning, advancing big data analytics and management: Tensorflow pretrained models. arXiv 2024. arXiv:2409.13566.

- Ren, J.; Rajbhandari, S.; Aminabadi, R.Y.; Ruwase, O.; Yang, S.; Zhang, M.; Li, D.; He, Y. ZeRO-Offload: Democratizing Billion-Scale Model Training. In Proceedings of the USENIX Annual Technical Conference, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rajbhandari, S.; Ruwase, O.; Rasley, J.; Smith, S.; He, Y. ZeRO-Infinity: Breaking the GPU Memory Wall for Extreme Scale Deep Learning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.07857. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.; Gan, S.; Awan, A.A.; Rajbhandari, S.; Li, C.; Lian, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, C.; He, Y. 1-bit Adam: Communication Efficient Large-Scale Training with Adam’s Convergence Speed. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.02888. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Qin, H.; Rajbhandari, S.; Ruwase, O.; He, Y. ZeRO++: Extremely Efficient Collective Communication for Giant Model Training. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.10209. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Gu, A.; Varma, R.; Luo, L.; Huang, C.C.; Xu, M.; Wright, L.; Shojanazeri, H.; Ott, M.; Shleifer, S.; et al. PyTorch FSDP: Experiences on Scaling Fully Sharded Data Parallel. Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment 2023, 16, 3848–3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Bhardwaj, R.; Ramjee, R.; Sivathanu, M.; Kwatra, N.; Han, Z.; Patel, P.; Peng, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Gandiva: Introspective Cluster Scheduling for Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 13th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation, 2018; pp. 595–610. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Bao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, C.; Guo, C. Optimus: An Efficient Dynamic Resource Scheduler for Deep Learning Clusters. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Thirteenth EuroSys Conference, 2018; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Moritz, P.; Nishihara, R.; Wang, S.; Tumanov, A.; Liaw, R.; Liang, E.; Elibol, M.; Yang, Z.; Paul, W.; Jordan, M.I.; et al. Ray: A Distributed Framework for Emerging AI Applications. In Proceedings of the 13th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation, 2018; pp. 561–577. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, W.; Li, Z.; Zhuang, S.; Sheng, Y.; Zheng, L.; Yu, C.H.; Gonzalez, J.E.; Zhang, H.; Stoica, I. Efficient Memory Management for Large Language Model Serving with PagedAttention. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, 2023; pp. 611–626. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, G.I.; Jeong, J.S.; Kim, G.W.; Kim, S.; Chun, B.G. Orca: A Distributed Serving System for Transformer-Based Generative Models. In Proceedings of the 16th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation, 2022; pp. 521–538. [Google Scholar]

- Leviathan, Y.; Kalman, M.; Matias, Y. Fast Inference from Transformers via Speculative Decoding. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, 2023; pp. 19274–19286. [Google Scholar]

- Alistarh, D.; Grubic, D.; Li, J.; Tomioka, R.; Vojnovic, M. QSGD: Communication-Efficient SGD via Gradient Quantization and Encoding. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2017; Vol. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Han, S.; Mao, H.; Wang, Y.; Dally, W.J. Deep Gradient Compression: Reducing the Communication Bandwidth for Distributed Training. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, K.; Tang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, X.; Chu, X. Understanding Top-k Sparsification in Distributed Deep Learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.08772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Bi, Z.; Song, J.; Liang, C.X.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Y. Hardware Accelerated Foundations for Multimodal Medical AI Systems: A Comprehensive Survey. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Bi, Z.; Wang, T.; Wen, Y.; Niu, Q.; Liu, J.; Peng, B.; Zhang, S.; Pan, X.; Xu, J.; et al. Deep learning and machine learning with gpgpu and cuda: Unlocking the power of parallel computing. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.05686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Song, S.L.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Tallent, N.R.; Barker, K.J. Evaluating Modern GPU Interconnect: PCIe, NVLink, NV-SLI, NVSwitch and GPUDirect. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems 2020, 31, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NVIDIA. NVLink and NVSwitch for Advanced Multi-GPU Communication. 2024. Available online: https://www.nvidia.com/en-us/data-center/nvlink/.

- NVIDIA. NVIDIA InfiniBand NDR. 2022. Available online: https://www.nvidia.com/en-us/networking/infiniband/.

- Liu, J.; Wu, J.; Panda, D.K. High Performance RDMA-Based MPI Implementation over InfiniBand. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 17th Annual International Conference on Supercomputing, 2003; pp. 295–304. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.H.; Geng, Y.; Haller, M.; Li, B.; Li, Y.; Miao, R.; Raindel, S.; Shen, P.; Zhao, J. RDMA over Ethernet for Distributed AI Training at Meta Scale. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGCOMM 2024, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Xue, F.; Baranwal, C.; Li, Y.; You, Y. Sequence Parallelism: Long Sequence Training from System Perspective. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.13120. [Google Scholar]

- Korthikanti, V.; Casper, J.; Lym, S.; McAfee, L.; Andersch, M.; Shoeybi, M.; Catanzaro, B. Reducing Activation Recomputation in Large Transformer Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2205.05198. [Google Scholar]

- Fedus, W.; Zoph, B.; Shazeer, N. Switch Transformers: Scaling to Trillion Parameter Models with Simple and Efficient Sparsity. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2022, 23, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- DeepSeek-AI. DeepSeek-V3 Technical Report. arXiv 2024. arXiv:2412.19437.

- Zheng, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhuang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhuo, D.; Xing, E.P.; et al. Alpa: Automating Inter- and Intra-Operator Parallelism for Distributed Deep Learning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.12023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Ring AllReduce: each GPU sends to its neighbor in a ring.

Figure 1.

Ring AllReduce: each GPU sends to its neighbor in a ring.

Figure 2.

Data parallelism: GPUs hold model replicas, process different batches , and synchronize gradients via AllReduce.

Figure 2.

Data parallelism: GPUs hold model replicas, process different batches , and synchronize gradients via AllReduce.

Figure 3.

GPipe schedule: forward passes (light) then backward passes (dark) across 4 pipeline stages.

Figure 3.

GPipe schedule: forward passes (light) then backward passes (dark) across 4 pipeline stages.

Figure 4.

Computation-communication overlap reduces iteration time.

Figure 4.

Computation-communication overlap reduces iteration time.

Table 2.

Memory requirements for different model sizes (excluding activations)

Table 2.

Memory requirements for different model sizes (excluding activations)

| Model Size |

Params (GB) |

Grads (GB) |

Optimizer (GB) |

| 1B |

2 |

2 |

12 |

| 7B |

14 |

14 |

84 |

| 13B |

26 |

26 |

156 |

| 70B |

140 |

140 |

840 |

| 175B |

350 |

350 |

2100 |

Table 3.

ZeRO optimization stages with memory reduction and communication overhead

Table 3.

ZeRO optimization stages with memory reduction and communication overhead

| Stage |

Partitioned States |

Memory Reduction |

Comm. Volume |

| ZeRO-1 |

Optimizer states |

|

|

| ZeRO-2 |

+ Gradients |

|

|

| ZeRO-3 |

+ Parameters |

|

|

Table 4.

Comparison of parallelism strategies across key dimensions

Table 4.

Comparison of parallelism strategies across key dimensions

| Strategy |

Memory Efficiency |

Compute Efficiency |

Communication Cost |

Scalability Limit |

Best Use Case |

| Data Parallel (DDP) |

Low |

High |

Medium (AllReduce) |

Model size |

Small-medium models |

| Tensor Parallel (TP) |

High |

High |

High (AllReduce) |

Attention heads |

Within-node scaling |

| Pipeline Parallel (PP) |

High |

Medium (bubbles) |

Low (P2P) |

Layer count |

Cross-node scaling |

| ZeRO-1/2 |

Medium |

High |

Medium (ReduceScatter) |

Model size |

Memory-constrained |

| ZeRO-3 |

Very High |

Medium |

High (AllGather) |

GPU count |

Very large models |

| 3D Parallelism |

High |

High |

Mixed |

Hardware |

100B+ parameters |

Table 5.

Comparison of ZeRO offloading approaches

Table 5.

Comparison of ZeRO offloading approaches

| Component |

ZeRO-Offload |

ZeRO-Infinity |

| Optimizer States |

CPU |

CPU + NVMe |

| Gradients |

CPU |

CPU + NVMe |

| Parameters |

GPU |

CPU + NVMe |

| Max Model Size (single GPU) |

13B |

>1T |

Table 6.

Feature comparison of distributed training frameworks

Table 6.

Feature comparison of distributed training frameworks

| Feature |

DeepSpeed |

Megatron |

GPipe |

FSDP |

| Data Parallel |

✓ |

✓ |

– |

✓ |

| Tensor Parallel |

✓ |

✓ |

– |

– |

| Pipeline Parallel |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

– |

| ZeRO/Sharding |

✓ |

– |

– |

✓ |

| CPU Offload |

✓ |

– |

– |

✓ |

| NVMe Offload |

✓ |

– |

– |

– |

Table 7.

NCCL collective operations with communication complexity

Table 7.

NCCL collective operations with communication complexity

| Operation |

Primary Use Case |

Comm. Volume |

| AllReduce |

Gradient synchronization (DDP) |

|

| AllGather |

Parameter reconstruction (ZeRO-3) |

|

| ReduceScatter |

Gradient sharding (ZeRO) |

|

| Broadcast |

Model initialization |

D |

| Send/Recv |

Pipeline parallelism |

D |

Table 8.

Summary of communication optimization techniques

Table 8.

Summary of communication optimization techniques

| Technique |

Typical Reduction |

Trade-off |

| Gradient Bucketing |

Latency hiding |

Memory for buffers |

| Top-K Sparsification |

10-100× |

Potential convergence impact |

| 1-bit Quantization |

32× |

Error feedback overhead |

| Hierarchical AllReduce |

2-8× |

Implementation complexity |

Table 9.

NVLink bandwidth evolution across GPU architectures

Table 9.

NVLink bandwidth evolution across GPU architectures

| Generation |

Architecture |

Bidirectional BW |

Links per GPU |

| NVLink 2.0 |

Volta (V100) |

300 GB/s |

6 |

| NVLink 3.0 |

Ampere (A100) |

600 GB/s |

12 |

| NVLink 4.0 |

Hopper (H100) |

900 GB/s |

18 |

| NVLink 5.0 |

Blackwell (B200) |

1.8 TB/s |

18 |

Table 10.

Comparison of InfiniBand and RoCE v2 for AI training

Table 10.

Comparison of InfiniBand and RoCE v2 for AI training

| Characteristic |

InfiniBand |

RoCE v2 |

| Latency |

∼1 s |

∼2-3 s |

| Bandwidth |

Up to 400 Gb/s |

Up to 400 Gb/s |

| Congestion Control |

Hardware-based |

PFC + ECN required |

| Infrastructure Cost |

Higher |

Lower |

| Operational Model |

Dedicated fabric |

Existing Ethernet |

| Proven Scale |

10,000+ GPUs |

Growing deployments |

Table 11.

Interconnect technology comparison across the communication hierarchy

Table 11.

Interconnect technology comparison across the communication hierarchy

| Technology |

Bandwidth |

Latency |

Scope |

| PCIe 5.0 |

128 GB/s |

∼1 s |

GPU-CPU |

| NVLink 4.0 |

900 GB/s |

<1 s |

Intra-node GPU |

| NVSwitch |

900 GB/s/GPU |

<1 s |

Intra-node all-to-all |

| InfiniBand NDR |

400 Gb/s |

∼1 s |

Inter-node |

| RoCE v2 |

400 Gb/s |

∼2 s |

Inter-node |

Table 12.

GPU specifications relevant for distributed training

Table 12.

GPU specifications relevant for distributed training

| GPU |

Memory |

BF16 TFLOPs |

NVLink BW |

TDP |

| A100 80GB |

80 GB |

312 |

600 GB/s |

400W |

| H100 SXM |

80 GB |

989 |

900 GB/s |

700W |

| H200 |

141 GB |

989 |

900 GB/s |

700W |

Table 13.

Parallelism strategy selection guide

Table 13.

Parallelism strategy selection guide

| Model Size |

Constraint |

Recommendation |

| < 10B |

– |

DDP + ZeRO-2 |

| 10B–100B |

Single node |

TP + ZeRO |

| 10B–100B |

Multi-node |

TP + PP + DP |

| > 100B |

NVLink |

TP8 + PP + DP |

| > 100B |

No NVLink |

PP + DP + ZeRO-3 |

Table 14.

Recommended parallelism strategies by model size

Table 14.

Recommended parallelism strategies by model size

| Model Size |

Single Node |

Multi-Node |

| <1B |

DDP |

DDP |

| 1–10B |

DDP + ZeRO-2 |

DDP + ZeRO-2 |

| 10–50B |

TP + ZeRO-1 |

TP + PP + DP |

| 50–200B |

TP + ZeRO-3 |

TP8 + PP + DP |

| >200B |

– |

3D Parallelism |

Table 15.

Common distributed training issues and resolutions

Table 15.

Common distributed training issues and resolutions

| Symptom |

Typical Resolution |

| Out of memory |

Reduce batch size, enable checkpointing |

| Low throughput |

Verify network bandwidth, enable overlap |

| Loss instability |

Reduce learning rate, check gradient clipping |

| Training hang |

Check NCCL timeout, verify connectivity |

Table 16.

Future research directions and key challenges

Table 16.

Future research directions and key challenges

| Research Area |

Key Challenge |

| Extreme Scale |

Efficient training on 10,000+ GPUs |

| Memory Systems |

Training models exceeding 10T parameters |

| Communication |

Achieving sub-linear scaling overhead |

| Automation |

Zero-configuration distributed training |

| Efficiency |

Approaching theoretical peak utilization |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |