1. Introduction

Based on potential implications for practical application in defence textiles, the practical application of advanced garments in defence not only enhances the safety and effectiveness of military personnel but also addresses broader logistical, environmental, and comfort challenges. Ongoing research and development in this field are vital to meet the evolving needs of defence operations. Considering temperature regulation, where textile fabrics with thermoregulating properties can effectively maintain a comfortable temperature for the wearer, mitigating heat and cold-induced stress during operations. Moisture management is a challenge to improve comfort and performance. Textiles with wicking properties exhibit superior moisture management capabilities, effectively capturing and dissipating sweat and moisture.

Moisture management is a crucial performance criterion in the garment business, determining fabric comfort levels [

1]. Motorsports athletes compete in high-speed races for hours in hot cockpits reaching 50 °C. Engineers prioritize speed and safety over driver comfort [

2]. To ensure comfort, clothes should maintain the body’s thermal balance throughout various environmental circumstances and activity levels [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. This function should not interfere with sweat-induced humidity removal or body temperature regulation. Alternatively, when the sweating rate is important, the liquid accumulation next to the skin and cooling generated from evaporation could altered. So, the sweat excess should be evacuated by evaporation to maintain the thermal balance.

Thermal energy that is nominally equal to the latent heat of liquid vaporisation is required to achieve evaporation [

9,

10,

11,

12]. A vapour pressure gradient is formed through the boundary layer of unsaturated air and incorporated into contact with saturated material. When water evaporates into the air, humidity levels increase. Heat is necessary

to evaporate water from the medium, and a decrease in the temperature of the medium will result in a temperature difference between the medium and the environment, which is necessary to maintain the water evaporation process [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

In the case of fabrics composed of cotton fibres as hydrophilic material, a part of the required heat to maintain water vapour evaporation is produced by liquid sorption through the fibre [

18,

19,

20]. Thus, the temperature drops at the fabric surface due to the evaporation, which will allow continuous liquid sorption. As a result, the ability of the textile to dry quickly improves water sorption by reducing moisture concentration and reducing fabric temperature [

21]. The textile fabric is a porous media comprising interconnected pores with irregular forms and sizes [

22,

23,

24,

25]. The drying of porous media is a displacement process in which the liquid phase in the pore space recedes because of evaporation [

22].

Two distinctive periods have been identified in most studies dealing with the drying process, which refers to the process of evaporating liquid from a porous media [

10,

11,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. At a constant speed, the drying takes place, and the liquid evaporates as a free liquid surface [

31]. This is known as the “constant rate period”. As the porous material dries and the moisture content drops below a certain level, it is known as the “critical moisture content”, which is the average material moisture content at which the drying rate begins to decline. In the period of rate decline, two sub-periods have been identified by other researchers [

7,

16,

32]: a linear and non-linear one. Drying mechanisms exhibit periods of constant rate and rate drop, even when the external drying conditions remain stable. The critical moisture content is defined as the minimum water concentration that allows capillary rise through the opened pores to ensure maximum evaporation at the peripheral surface. When the moisture content is critical, the surface area of the liquid decreases, reducing the water evaporation rate in the wet, exposed area [

32]. The critical moisture content is dependent on the amount of moisture adsorbed, but it is also dependent on the drying speed and the material structure. In general, the critical moisture content of a hydrophilic material is higher than that of a hydrophobic textile material with similar structural parameters [

11,

23].

Droplet drying measurement methods are crucial for understanding the dynamics of droplet evaporation, which has applications in various fields such as comfort, inkjet printing and pharmaceuticals. Various methods are used to study droplet drying, including optical, acoustic, thermal, and mass measurement techniques. These methods provide insights into droplet shape, size, thickness, temperature and evaporation rates. When selecting a droplet drying measurement method, it is essential to consider the specific requirements of the study or application. The gravimetric methods are widely used to study the drying of the textile fabrics. The Moisture Analyser Method [

34] is used to measure the textile drying time. The textile sample is moistened, immersed in deionised water for 1 min, hung vertically for 5 min, and left to dry freely. The weight of the fabric is then weighed again to determine the drying time. This method can be used only for absorbable materials and does not reflect the physical activities and real conditions to be considered: walking speed, temperature and relative humidity.

The ISO 17616 and Japanese JIS L 1096-1999 standards for moisture drying rate and speed [

35,

36] are employed for the determination of drying characteristics after wetting by sweat. The ISO 17617 method expresses the moisture content over time as a drying rate. There are two methods: the vertical method A and the horizontal method B. Method A is divided into A1 and A2 depending on the location where the sample is mounted. In the case of A1, after dropping 0.3 mL of water, the mass is measured at 5-minute intervals until the time reaches 60 minutes or the residual moisture content falls within 10% of the initial value [

36]. The two methods simulated low-intensity activities or normal manual work without any possibility of controlling the airflow to simulate outdoor activities. The air velocity can affect the cooling evaporative heat flow and the mobility of water vapour particles [

37].

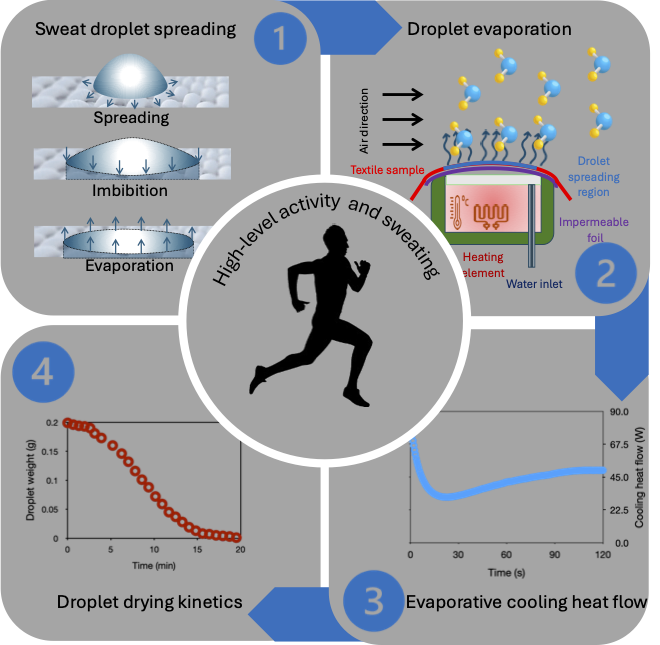

In this study, a new mathematical model considering the fabric structural parameters, liquid properties and test conditions was developed based on an ISO 11092 modified measurement protocol to calculate the dried amount of a droplet. The Permetest skin model was used to study the droplet drying kinetics deposited at the surface of a textile fabric under controlled environmental conditions.

2. Drying Kinetics Modelling During Evaporation

To predict the water vapour resistance, a new mathematical model was established based on the measuring standard of the Permetest skin model according to ISO 11092 [

38].

The instrument measures the water vapour Resistance (Ret) [m2Pa/W] and the relative water vapour (RWVP) [%]. The measuring head has a curved meshed surface with a diameter of about 80 mm covered with a semipermeable foil to keep the sample dry. Water vapour passes through the membrane to simulate transpiration. A sensor system records the cooling evaporative heat flow and analyses it using a computer. The head is covered with a semipermeable film. The heating power (q0) is recorded without a sample. Then, the textile is inserted between the head and the channel opening. Reaching the steady state, the wet head’s heat loss (qs) is registered.

According to ISO 11092

38, at equilibrium, the resistance to evaporation is as follows:

Where:

- -

Psat,T: The measuring head surface partial pressure of saturated water vapour in test conditions [Pa],

- -

Pvap: The water-vapour partial pressure in test conditions [Pa],

- -

As: The area of sample surface [m2],

- -

H: The heating power of measurement heat [W],

- -

ΔH: The heating power correction term [W].

Without a sample, the semipermeable membrane water vapour resistance (R

et0) simulating human skin is:

The heat required (Q) to maintain a constant temperature on the surface of a plate is:

According to the mass conservation principle and continuity conditions, the provided heating flow by the hot plate is equivalent to the evaporation flow (evaporative cooling flow) [

39]. Cooling is mostly the function of water vapour permeability level. Wicking fabrics must be in thermal contact with the skin to cause cooling effects. So, we have:

Here:

- -

LH2O: evaporation water latent heat [J/Kg],

- -

Øm0: equilibrium evaporated mass flow [Kg/m2s].

Combining Equations (2)–(4) leads to:

According to Fick’s first law, at equilibrium, the water-vapour mass flow through the water-vapour permeable membrane is:

Where:

- -

D0,T: The diffusion coefficient of water vapour from semipermeable foil in test temperature [m2/s],

- -

MH2O: molecular weight of water (18.015 10-3Kg/mol),

- -

: concentration gradient [mol/m3],

- -

X: spatial coordinates of the molar concentration [m].

the concentration gradient (

)can be determined from the relation [

40]:

Here:

- -

∆Pvap=Psat,T-Pvap: water vapour pressure difference [Pa],

- -

R: gaz constant (R = 8.315 103J/Kmol.˚K),

- -

Ttest: Absolute temperature during the test [˚K].

Consequently, the mass flow of water vapour during evaporation from the semi-permeable membrane is:

Where:

- -

RH2O=R/MH2O: Water vapour specific constant (= 461.5 J/(Kg.˚K)),

- -

th0: semi-permeable membrane thickness [m].

Replacing the mass flow (

m0) in the Equation (5), we obtain:

The semipermeable membrane water vapour resistance (R

et0) corresponds to calibration steps performed at the beginning of the measuring protocol (without a sample). It is noteworthy that semipermeable membrane and fabric sample are in series system. Consequently, it is imperative to consider the following:

Where:

- -

: Fabric thickness [m],

- -

DTotal,T: Total diffusion coefficient on the water vapour at test temperature [m2/s],

- -

Dsample,T: Diffusion coefficient of the water vapour through the sample in test condition temperature [m2/s].

Hence, the Equation (10) leads to:

By covering the measuring head with a cellophane film (impermeable to the water vapour) instead of the semipermeable foil, the deposited droplet on the textile sample and in contact with the surrounding air is the only origin of the evaporation (

Figure 1).

Figure 2 illustrates the evaporative cooling heat flow kinetics with and without samples. Without a sample, it presents a water vapour-proof nude skin. The dried sample was conditioned under test conditions for 24 hours before testing.

As depicted in

Figure 2, the evaporative cooling heat flow exhibits numerical constancy, with an average value of approximately 100±0.11 W in the absence of the sample (simulating naked skin) and 97±1.53 W in its presence. The corresponding coefficients of variation are 0.11% and 1.58%, respectively. The heat flow immediately drops after depositing the sample on the measuring head is less than 91±2.3 W, commencing with a value of 99.2±1.5 W and subsequently stabilising at 97±1.53 W from 2.5 minutes. The initial heat flow drop was caused by the exothermal moisture absorption in the measured fabric.

So, the (R

et0) = 0. Meaningful, there is no evaporation from the Permetest measuring head in this case and the evaporative cooling heat flow will be maintained at 100 W, as calibrated. Thus, Equation (12) will be reduced to:

The Equation (13) could be written as follows:

Considering textile fabrics as porous materials with a total porosity (ε

Total) and tortuosity (τ), the water vapour effective evaporative diffusion coefficient is:

D

air,T is the diffusion coefficient of the water vapour in the air in the test conditions temperature. By analogy, the Equation (8) leads to the following expression:

Replacing the expression of the effective evaporation coefficient of the water vapour presented by Equation (15) and considering the total porosity and tortuosity, Equation (16) can be rewritten as follows:

Using Equation (2), the expression of water vapour mass flow during droplet evaporation from the sample leads to:

Here, Q[W] represents the evaporative cooling heat flow recorded by the Permetest apparatus during droplet evaporation. According to equation 18, the droplet’s substantial evaporation flow from the textile fabric is a function of the sample’s structural parameters (thickness, tortuosity, and total porosity), the physical characteristics of water vapour under test conditions (diffusion coefficient through the sample, partial pressure of saturated water vapour at the surface of the measuring unit, and water vapour partial pressure of the air), and the test environmental conditions (temperature and relative humidity).

The total porosity of a woven fabric can be expressed as follows [

[39]:

Where:

- -

and : respectively the average diameters of the warp yarns and weft ones [m],

- -

Wa/cm and We/cm: respectively the warp density weft density [threads/m],

- -

r(%) and em (%): respectively the weft and warp crimp [%],

- -

ths: sample thickness [m].

As demonstrated in equation (19), porosity is not directly influenced by fabric design patterns. Nevertheless, it is correlated with structural compactness, which encompasses factors such as warp and weft diameters, yarn crimp, and thickness. It is inversely proportional to warp and weft diameters (D

Warp and D

Weft), yarn crimp and warp and weft densities but proportional to thickness.

Where;

- -

, characterizing the evaporation parameters,

- -

, describing the structural and geometrical parameters of the sample fabric.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Rip-Stop Fabric Pattern Design

Figure 3 depicts two different rip-stop fabric pattern designs. The fabric design was based on the delimiting grid variation between plain-woven structures. Samples were woven using the rigid rapier Dornier weaving machine HTV/HTVS/PTV with the Bonas ZJ2 jacquard system.

The tested fabrics were woven with the same warp yarn, which contained 100% polyester and had a yarn number of 25 Nm. Weft yarns of 25 Nm from various materials (100% cotton and 100% polyester) were used. The warp and weft count were set at 24±2 threads/cm. The woven fabric thickness has been determined using the ISO 5084:1996 standard [

41]. The weight per unit area, warp and weft densities were determined using the ISO 7211-6:2020 standard [

42]. The yarn’s linear densities have been determined using the ISO 2060:1994 standard [

43]. The warp and weft densities were estimated using the ISO 7211-2:2024 standard [

44]. The total porosities of the plain-woven zone and the delimiting grid one were calculated based on equation 19.

Table 1 illustrates the ripstop defence fabrics’ structural properties.

3.2. Experimental Test Protocol

First, the tested sample was deposited at the top of the Permetest measured head covered by a water vapour impermeable membrane. Then, the heat flow was adjusted to 100 W. Next, a 200 ± 2 mg at an experimental test temperature of the distilled water droplet was applied on the top surface of the textile sample placed on top of the measuring heat. While the droplet evaporated from the sample, the varied evaporative cooling heat flow was permanently registered and visualized using the Permetest. Finally, the recorded evaporative heat flux was converted to the droplet evaporated mass using Equation 20 and considering the evaporation, structural and geometrical parameters.

All tests were carried out under standard conditions in an atmosphere of 20±2 ˚C and 65±4% relative humidity relative humidity according to standard ISO 139:2005 [

45] and air velocity was adjusted to 1 m/s. Isothermal conditions inside the instrument during the Ret measurements were maintained with the precision ±0.1˚ C. The droplet was kept in the testing conditions for 24 hours before deposing. All fabric samples were conditioned in the same atmosphere 24 hours before testing.

4. Results and Discussion

Figure 4 illustrates the evaporative cooling heat flow kinetics while a droplet evaporates from a textile fabric using the developed methodology. To determine the droplet evaporation from the textile sample, a modified test protocol was implemented. A water vapour impermeable membrane was positioned between the sample and the measuring head to prevent evaporation from the Permetest water reservoir. Consequently, the sole source of evaporation was the droplet deposited on the top surface of the tested sample. As the heat flow (Q) was continuously recorded by the Permetest, the evaporated droplet mass was determined using Equation 20.

The existence of three different phases was noticed by analysing the

Figure 4:

- -

Phase 1: The drying kinetics is low, with a flattening at the droplet mass change. The slope of the drop mass reduction is very modest. At this level, drop penetration through the sample thickness is more significant than drying, and the drop spread diameter is minimal. As a result, the drop’s surface area exposed to evaporation is reduced as illustrated in

Figure 5.

- -

Phase 2: During this phase, the kinetics of droplet mass decrease exhibit the steepest negative slope. This phase corresponds to the complete distribution of droplet throughout the textile surface. This ensures that the droplets are evenly spread at the sample surface, facilitating evaporation (

Figure 5).

- -

Phase 3: the downward rate of the drying curve slope decreases and tends to zero. This indicates the quantity of direct water absorbed by the sample, which is difficult to remove without additional energy.

Figure 5 illustrates the overall dynamics of spreading, imbibition, and evaporation for a liquid droplet on a porous substrate, such as a textile fabric. Lucas-Washburn formulated the spontaneous flow of liquid through porous media as being linearly proportional to the square root of the time elapsed. [

46]. During the spreading process, the macropores primarily facilitate the wicking action and rapidly absorb water. Subsequently, these macropores serve as a reservoir to convey liquid through the fabric via the interconnected micropores. Subsequently, during evaporation, which is related to spreading and imbibition dynamics on a porous substrate due to variations in droplet surface area and primarily influenced by the direct and indirect water proportion, this amount depends on the fibre type: hydrophilic or hydrophobic. In our case, cotton is easy to wet and difficult to dry compared to polyester fibre.

Established from

Figure 4, the droplet drying kinetics properties are summarised in

Table 2.

Based on

Table 2, which summarizes the three phases of the drying kinetics, the sample made with 100% polyester weft yarns exhibited the most competitive performance during phase 1. The drying period interval was limited to 0.8±0.1 minutes, with a negative drying slope of approximately -0.0129±0.0002 g/min. In contrast, the drying period interval was extended to 1.4±0.2 minutes, with a negative drying slope of approximately -0.0183±0.0004 g/min, in the case of Structure 2-P and Structure 1-P, respectively. The total drying times for samples woven with 100% polyester weft yarns were limited to 8.3 ± 0.21 minutes and 12.25 ± 0.25 minutes, respectively, for the Structure 2 and Structure 1. Conversely, the total drying times for samples woven with 100% cotton weft yarns were prolonged to 20.25 ± 2.52 minutes and 16.2 ± 1.34 minutes, respectively, for the Structure 1 and Structure 2.

Polyester fibres are hydrophilic and do not absorb water. Consequently, water vapour particles are trapped within the scales of pores without absorption. This phenomenon results in rapid water particle spread and imbibition compared to cotton fibres. The same behaviour was observed during phases 2 and 3.

Table 2 further indicates that Structure 2 dries faster than Structure 1, regardless of the raw material used (cotton or polyester).

Figure 3 illustrates that the floats in the delimiting grid are more pronounced in Structure 1 due to its porosity compared to Structure 2. Consequently, greater porosity of the sample Structure 2 leads to a more breathable structure.

As presented in

Table 1, there were no significant changes in the total porosity levels for cotton and polyester between Structure 1 and Structure 2 in the plain woven design zone. This was because the lengths of floats remained constant. However, the porosity values varied as the lengths of floats were changed in the delimiting grid zone.in fact, in Structure 1, the floats were distributed over five warps and five wefts in both the longitudinal and transversal directions. Conversely, in Structure 2, the length of floats was limited to two yarns in both directions. Consequently, the porosity values changed between structures, leading to variations in the thermal contact points with the skin.

5. Conclusions

To conclude, a novel methodology for investigating the kinetics of water droplet drying during evaporation from a defence textile fabric was introduced. Mathematical modelling was developed based on a modified Permetest skin method and the water vapour evaporation kinetics of droplet evaporation from the surface of a textile fabric. A water vapour impermeable membrane was placed at the top of the Permetest measuring head to ensure that the deposit droplet was the only source of evaporation from the textile sample. It was observed that the raw materials and fabric design structures significantly influence the evaporation kinetics. Hydrophilic fibres exhibit faster drying rates compared to hydrophobic fibres. Furthermore, adding floats in the delimiting grid of ripstop defence fabrics results in a slower-drying fabric. During droplet evaporation and drying, three distinct phases were noticeable. During the first one, the drying kinetics are low and the drop penetration through the sample thickness is more significant than drying. In the second phase, the drop mass decreases most rapidly, ensuring even distribution throughout the fabric and promoting evaporation. The slope of the curve decreases and approaches zero during the third phase, indicating the quantity of direct water absorbed by the sample, which requires more energy to remove, especially for cotton fibres. Using polyester in textile fabrics reduces drying time from 65% to 95% compared to cotton. Adding floats to ripstop fabrics in the deliming grid zone extends drying time by about 20% when cotton yarns are used, compared to 32% when polyester is added.

In summary, the developed mathematical model was designed to precisely align with the fabric construction parameters, liquid properties, and test conditions of a droplet evaporation kinetics from the textile fabric. This model will serve as a crucial tool for optimizing drying processes, thereby substantially enhancing the comfort of sportswear. In the future, the research framework will prioritize investigating the impact of varying air velocities on the drying process.

References

- Knížek, R; Bajzík, V; Tunáková, V. Water-resistant and vapor-permeable textile laminates containing nanofiber membrane as footwear lining. Journal of Industrial Textiles 2024, 54, 15280837241301772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedy, R; McQuerry, M. Thermal comfort analysis of auto-racing suits using a dynamic thermal manikin. Journal of Industrial Textiles 2023, 53, 15280837221150648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinta, SK; Gujar, PD. Significance of Moisture Management for High Performance Textile Fabrics. Int J Innov Res Sci Eng Technol; 2.

- Mayur, B; Mrinal, C; Saptarshi, M; et al. Moisture Management Properties of Textiles and Its Evaluation. Current Trends in Fashion Technology & Textile Engineering 2018, 3, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheuvront, SN; Haymes, EM. Thermoregulation and Marathon Running. Sports Medicine 2001, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengasamy, RS. 5—Wetting phenomena in fibrous materials. In Thermal and Moisture Transport in Fibrous Materials; Pan, N, Gibson, P, Eds.; Woodhead Publishing; pp. 156–187.

- Haghi, AK. Moisture permeation of clothing: A factor governing thermal equilibrium and comfort. J Therm Anal Calorim 2004, 76, 1035–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S; Barker, RL. Moisture Management Properties of Heat-Resistant Workwear Fabrics— Effects of Hydrophilic Finishes and Hygroscopic Fiber Blends. Textile Research Journal 2004, 74, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissan, AH; Kaye, WG; Bell, JR. Mechanism of drying thick porous bodies during the falling rate period: I. The pseudo-wet-bulb temperature. AIChE Journal 1959, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, DW; Vollers, CT; Einashar, AM. Contact drying of a sheet of moist fibrous material. Journal of Manufacturing Science and Engineering, Transactions of the ASME 1980, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, DW; Vollers, CT. The Drying of Fibrous Materials. Textile Research Journal 1971, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinisch, T; Bajzík, V; Hes, L. New methodology and instrument for determination of the isothermal drying rate of cotton and polypropylene fabrics at constant air velocity. J Eng Fiber Fabr 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippen, LK. Moisture transport properties of selected knit fabrics. University of North Carolina at Greensboro. 1975. Available online: https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/Crippen_uncg_7606510.PDF (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Cowen, W. Some Principles of Drying. Journal of the Society of Dyers and Colourists 1939, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C; Takater, M. Change of temperature of cotton and polyester fabrics in wetting and drying process. Journal of Fiber Bioengineering and Informatics 2012, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W; Xu, W; Cui, W; et al. A novel method to analyze the moisture liberation of textile fabrics. In Epub ahead of print Fibers and Polymers; 2008; Volume 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, JR; Nissan, AH. Mechanism of drying thick porous bodies during the falling-rate period: II. A hygroscopic material. AIChE Journal 1959, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W; Cheng, L; Liu, Y; et al. Study on the thermo-physiological comfort properties of cotton/polyester combination yarn-based double-layer knitted fabrics. Textile Research Journal 2024, 00405175241268802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W; Zhang, L; Cheng, L; et al. Investigation of the moisture transfer ability and thermal comfort properties of single-layer cotton/polyester interwoven fabrics. Textile Research Journal 2023, 94, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benltoufa, S; Algamdy, H; Ghith, A; et al. The water vapour resistance dynamic measurement of natural and synthetic fibre. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology 2024, 36, 1094–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, JO; Spivak, SM. Dynamic Moisture Vapor Transfer Through Textiles: Part II: Further Techniques for Microclimate Moisture and Temperature Measurement. Textile Research Journal 1994, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiotis, AG; Boudouvis, AG; Stubos, AK; et al. Effect of liquid films on the isothermal drying of porous media. Phys Rev E 2003, 68, 37303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, JR; Grosberg, P. 18—The movement of vapour and moisture during the falling rate period of drying of thick textile materials. Journal of the Textile Institute Transactions 1962, 53, Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissan, AH; George, HH; Bolles, T V. Mechanism of drying thick porous bodies during the falling-rate period: III. Analytical treatment of macroporous systems. AIChE Journal 1960, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilllland, ER. Fundamentals of Drying and Air Conditioning. Ind Eng Chem Epub ahead of print. 1938, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRESTON, JM; CHEN, JC. Some Aspects of the Drying and Heating of Textiles: Part I–The Moisture in Fabrics. Journal of the Society of Dyers and Colourists 1946, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N; Arakeri, JH. Investigation on the effect of temperature on evaporative characteristic length of a porous medium. Drying Technology 2020, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujumdar, AS. Drying: Principles and practice. In Albright’s Chemical Engineering Handbook;Epub ahead of print; 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourt, L; Sookne, AM; Frishman, D; et al. The Rate of Drying of Fabrics. Textile Research Journal 1951, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidzadeh-Bonn, N; Azouni, A; Coussot, P. Effect of wetting properties on the kinetics of drying of porous media. Journal of Physics Condensed Matter 2007, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perré, P. Multiscale aspects of heat and mass transfer during drying. In Drying of Porous Materials; Kowalski, SJ, Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht; pp. 59–76.

- Coplan, MJ. Some Moisture Relations of Wool and Several Synthetic Fibers and Blends. Textile Research Journal 1953, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, MW. Heat and mass transfer in drying of porous media. Drying Technology 2021, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AATCC Test Method 199-2011. Drying time of textiles: moisture analyser method. 2011.

-

JIS L 1096:1999; Testing methods for woven fabrics: drying speed.

-

ISO 17616:2014; Textiles: determination of moisture drying rate.

- Benltoufa, S. The dynamic of cooling heat flow of simple jersey polyester fabric. Industria Textila 2024, 75, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

ISO 11092:2014; Textiles—Physiological effects—Measurement of thermal and water-vapour resistance under steady-state conditions (sweating guarded-hotplate test). International Organisation for Standardisation: Geneva (Switzerland), 2014.

- Benltoufa, S; Boughattas, A; Fayala, F; et al. Water vapour resistance modelling of basic weaving structure. The Journal of The Textile Institute 2024, 115, 2456–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourt, L; Harrist, M. Diffusion of Water Vapor Through Textiles. Textile Research Journal 1947, 17, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

ISO 5084:1996; Textiles — Determination of thickness of textiles and textile products. 1996.

-

ISO 7211-6; Textiles — Methods for analysis of woven fabrics construction Part 6: Determination of the mass of warp and weft per unit area of fabric. 2020.

-

ISO 2060:1994; Textiles — Yarn from packages — Determination of linear density (mass per unit length) by the skein method. 1994.

-

ISO 7211-2; Textiles — Methods for analysis of woven fabrics construction — Part 2: Determination of number of threads per unit length. 2024.

-

ISO 139:2005; Textiles — Standard atmospheres for conditioning and testing. 2005.

- Das, S; Patel, H V; Milacic, E; et al. Droplet spreading and capillary imbibition in a porous medium: A coupled IB-VOF method based numerical study. Physics of Fluids 2018, 30, 012112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).