1. Introduction

Polyacrylonitrile (PAN) nanofiber membranes (PAN NFs) have gained significant attention due to their low density, excellent flexibility, and cost-effectiveness. These advantageous properties have led to their widespread use in industries such as textiles, construction materials, and as precursors for carbon fibers [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In addition, the chemical reactivity of the nitrile group in PAN allows for its functionalization into various groups, such as amino[

5], carboxyl[

6], and pyridine[

7], which further expand its application scope, including metal ion adsorption, catalysis, and catalyst supports. These developments have provided valuable insights for the design of novel functional materials based on PAN NF membranes, particularly in the context of nitrile group functionalization[

8].

Polyionic liquids (PILs), which combine the properties of ionic liquids and traditional polyelectrolytes, have garnered considerable attention in recent years. They are particularly suitable as carriers for functional materials through simple anion exchange processes. Traditional methods of synthesizing PILs often involve the free radical polymerization of ionic liquid monomers with vinyl groups[

9]. This method is straightforward and holds broad application potential; however, the low polymerization degree of PILs limits their range of applications[

10]. An alternative approach is to modify the nitrogen-containing side groups (such as imidazole or pyridine) in synthetic polymers. Given that PAN can undergo cyclization with piperazine to form poly-vinylpyridine, it is hypothesized that PAN-based PILs could be prepared by ionizing the pyridine groups, while maintaining the high polymerization degree and nanofiber membrane morphology of PAN.

In recent years, the treatment of wastewater containing organic dyes has emerged as a key research area in environmental remediation[

11]. While techniques such as membrane separation, adsorption, and biodegradation have made significant progress[

12], challenges remain, including low pollutant removal efficiency, the generation of secondary pollution, and the formation of harmful intermediates[

13,

14,

15,

16]. As a result, these methods face practical limitations in real-world applications. Recently, photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes in wastewater, particularly under visible light irradiation, has attracted significant interest due to its effective use of renewable energy and environmentally friendly nature compared to other catalytic systems[

17,

18,

19].

Polyoxometalates (POMs) are a class of stable transition metal oxide compounds with semiconductor properties[

20,

21]. However, the separation and recovery of water-soluble POMs present significant challenges. To address this issue, loading POMs onto carrier surfaces has proven to be an effective strategy[

22,

23,

24]. Therefore, developing a low-cost, readily available, and highly immobilized stable carrier material is crucial.

Table 1 summarizes recent advancements in photocatalytic membrane materials. By comparing the characteristics of photocatalysts in terms of raw material selection, preparation methods, degradation substances, preparation costs, reusability, and visible light responsiveness, it is concluded that the development of a visible-light-responsive, low-cost, easily recyclable, flexible, and water-insoluble polymer catalyst is an effective approach for dye wastewater degradation.

Polyacrylonitrile (PAN) nanofiber membranes (NF) are well-known for their low cost, excellent flexibility, and wide range of applications, including in textiles, construction materials, and carbon fiber precursors. However, their inherent properties can be further enhanced by functionalization, such as the conversion of nitrile groups into various functional groups, which broadens their applications in areas such as metal ion adsorption and catalysis. In recent years, poly(ionic liquid)s (PILs) have attracted considerable attention due to their unique combination of ionic liquid and traditional polyelectrolyte properties, making them ideal candidates as functional material carriers via simple anion exchange processes. However, traditional methods for preparing PILs often involve low polymerization degrees, limiting their application potential.

In this study, a novel approach is introduced wherein low-cost and flexible PAN NF membranes are modified into PILs and further functionalized with the photocatalytically active phosphomolybdic acid (PMo). The resulting PM-PIL composite membrane exhibits excellent photocatalytic performance for the degradation of methyl blue (MB) under visible light irradiation, demonstrating the potential of composite photocatalytic materials with high molecular weight and nanofiber membrane structures. This study highlights the excellent catalytic activity, reusability, and stability of PM-PIL as an efficient photocatalyst, providing a promising platform for sustainable environmental applications, particularly in the field of wastewater treatment.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. FTIR and SEM Analysis

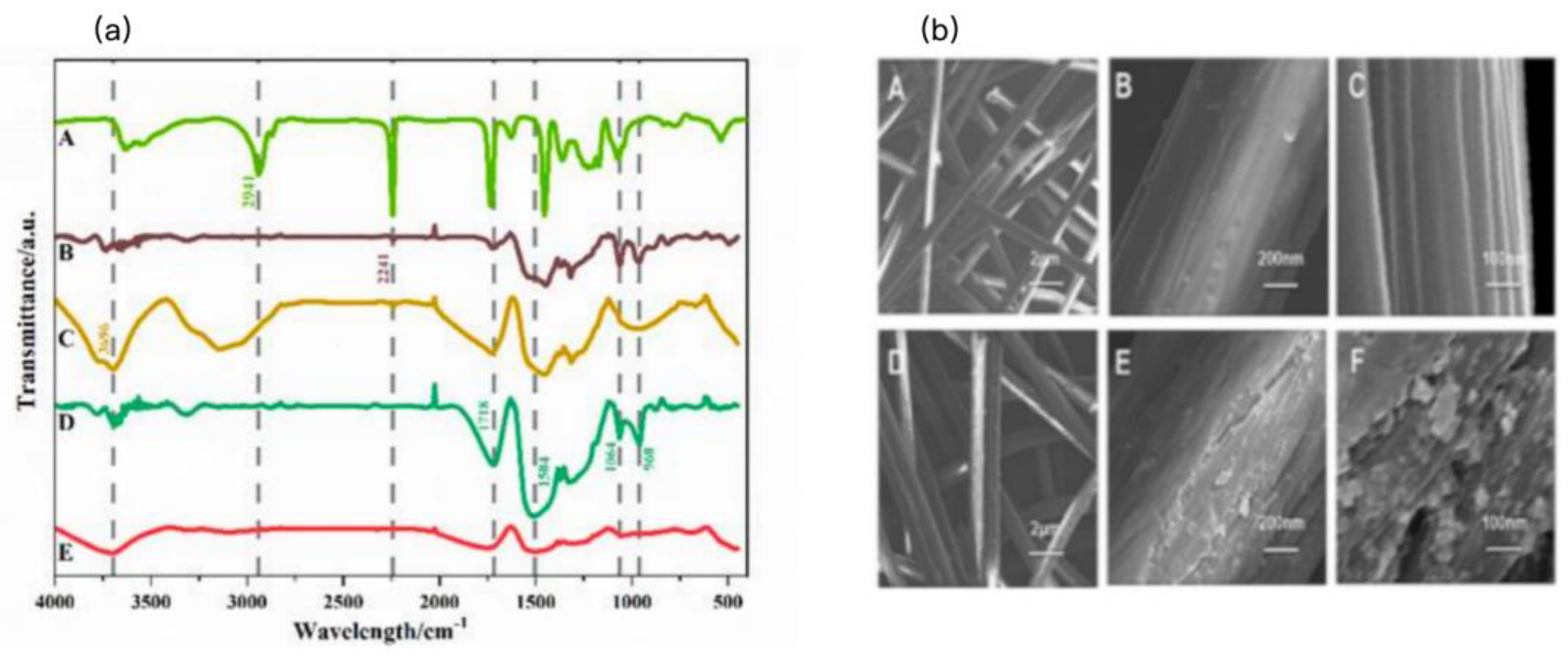

The structural properties of the PAN, PVPy, Br-PIL, PM-PIL nanofiber (NF) membranes and PMo were characterized using Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy, and the results are shown in

Figure 1a. In the FT-IR spectrum of PAN, the absorption peak at 1451 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the in-plane C-H vibration, while the peaks at 2246 cm⁻¹ and 1074 cm⁻¹ are attributed to the stretching and bending vibrations of the C≡N group, respectively[

40,

41,

42]. In the FT-IR spectrum of PVPy, the characteristic peak at 2246 cm⁻¹, associated with the C≡N group, disappears, and new peaks at 1673 cm⁻¹ and 1389 cm⁻¹ are observed, corresponding to the C=N and C-N stretching vibrations in the pyridine ring. This confirms the successful transformation of the C≡N group into pyridine units via cyclization with piperazine[

43,

44].

The FT-IR spectrum of PMo exhibits characteristic absorption peaks at 1074 cm⁻¹, 998 cm⁻¹, 892 cm⁻¹, and 813 cm⁻¹, corresponding to the P-O, W-O, WO-W corner, and W-O-W edge vibrations, respectively. In the FT-IR spectrum of the PMo-PIL composite, the absorption peaks at 1074 cm⁻¹ and 998 cm⁻¹ are related to the P-O group vibrations and W-O resonance, while the peaks at 1673 cm⁻¹ and 1074 cm⁻¹ correspond to the vibrations of the pyridine structure[

45]. These results clearly indicate the successful preparation of the PMo-PIL composite.

Figure 1b presents the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the PAN and PM-PIL NF membranes. Compared to the PAN membrane, the surface of the PM-PIL membrane exhibits a rougher texture, which can be attributed to the uniform distribution of polyoxymethylene (POM) on the surface of the PM-PIL membrane. Additionally, a honeycomb-like cavity structure is observed on the surface of the PM-PIL NF membrane. This unique morphology may enhance the specific surface area and adsorption capacity of the membrane[

46], suggesting that the PM-PIL membrane has the potential to serve as an ideal polymer support material for various applications.

The FT-IR and SEM analyses collectively confirm the successful fabrication of the PM-PIL composite membrane and provide valuable insights into its structural characteristics. The incorporation of POM and the unique nanofiber morphology are expected to contribute to the enhanced photocatalytic performance and reusability of the PM-PIL membrane, which is further investigated in the following sections.

2.2. XPS Analysis

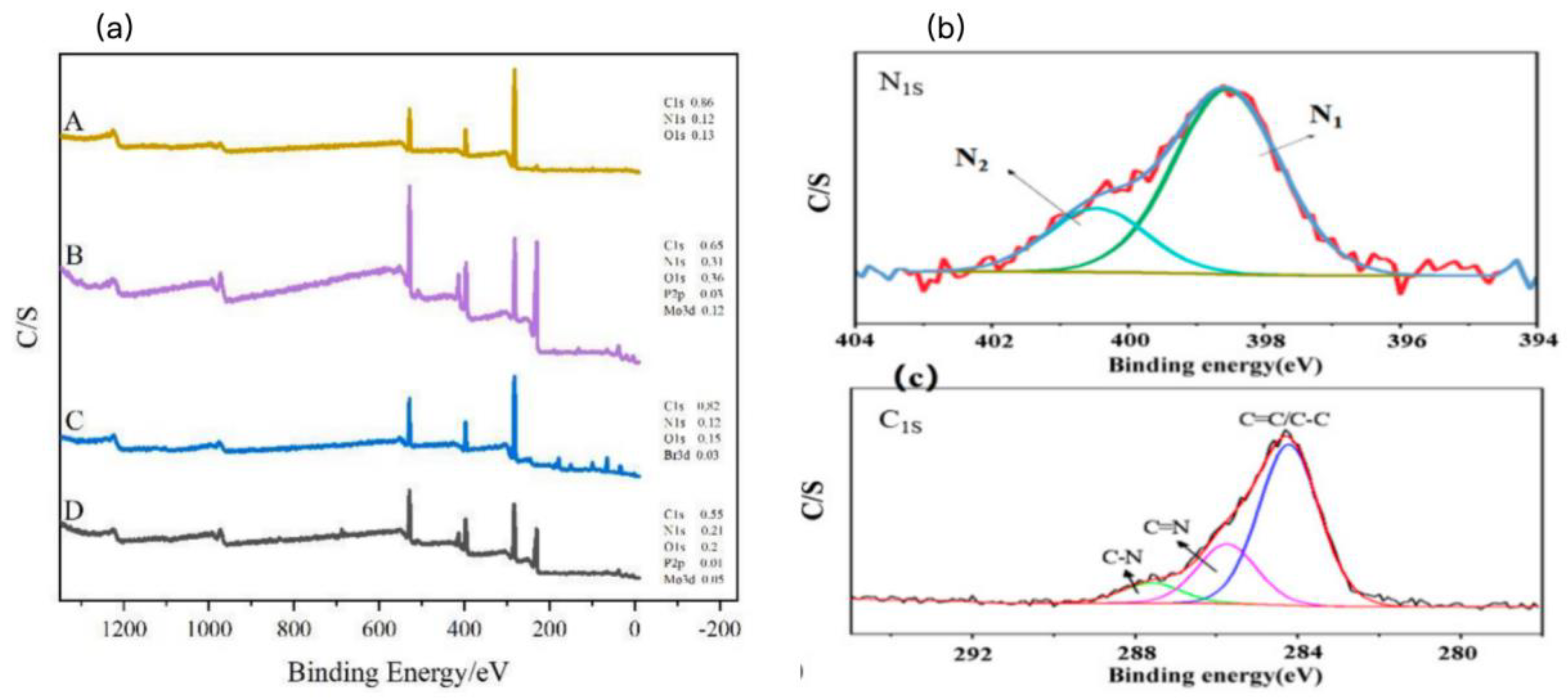

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was employed to investigate the surface chemical composition and elemental valence states of the PM-PIL NF membrane. As shown in

Figure 2a, the survey XPS spectrum reveals the presence of C, O, N, P, and W elements on the membrane surface. The C and N signals originate from the PAN-derived polymer backbone, while the appearance of P and W elements can be attributed to the successful immobilization of phosphomolybdic acid (PMo) onto the PIL nanofiber membrane. Notably, the tungsten content reaches 5.14 wt%, indicating that the anion exchange process proceeded efficiently and that PMo was effectively loaded onto the PIL framework.

To further elucidate the chemical states of nitrogen species, high-resolution N 1s XPS spectra were analyzed (

Figure 2b). Two distinct peaks were observed at binding energies of 400.7 eV (N1) and 402.3 eV (N2), which are characteristic of nitrogen atoms in pyridine-like structures. These results are consistent with the FTIR analysis and confirm the successful conversion of nitrile groups into nitrogen-containing heterocyclic units during the cyclization and ionization processes. The presence of positively charged nitrogen sites is crucial for stabilizing PMo anions through electrostatic interactions, thereby enhancing the immobilization efficiency of the photocatalyst.

The high-resolution C 1s spectrum (

Figure 2c) can be deconvoluted into three main components. The dominant peak corresponds to C–C/C–H bonds, indicating the polymer backbone structure. Two additional peaks with lower intensities are assigned to C–N and C=N bonds, respectively, further confirming the formation of pyridine-type structures and other nitrogen-containing functional groups on the membrane surface. These nitrogen-rich functionalities not only provide anchoring sites for PMo but may also facilitate charge transfer during the photocatalytic process.

Overall, the XPS results provide compelling evidence for the successful fabrication of the PM-PIL NF membrane, demonstrating effective PMo immobilization via anion exchange and the formation of a nitrogen-enriched polymer surface. The coexistence of PMo species and pyridine-based PIL structures on the nanofiber membrane surface is expected to play a synergistic role in enhancing visible-light-driven photocatalytic activity and structural stability during repeated catalytic cycles.

2.3. UV-Vis and XRD Analysis

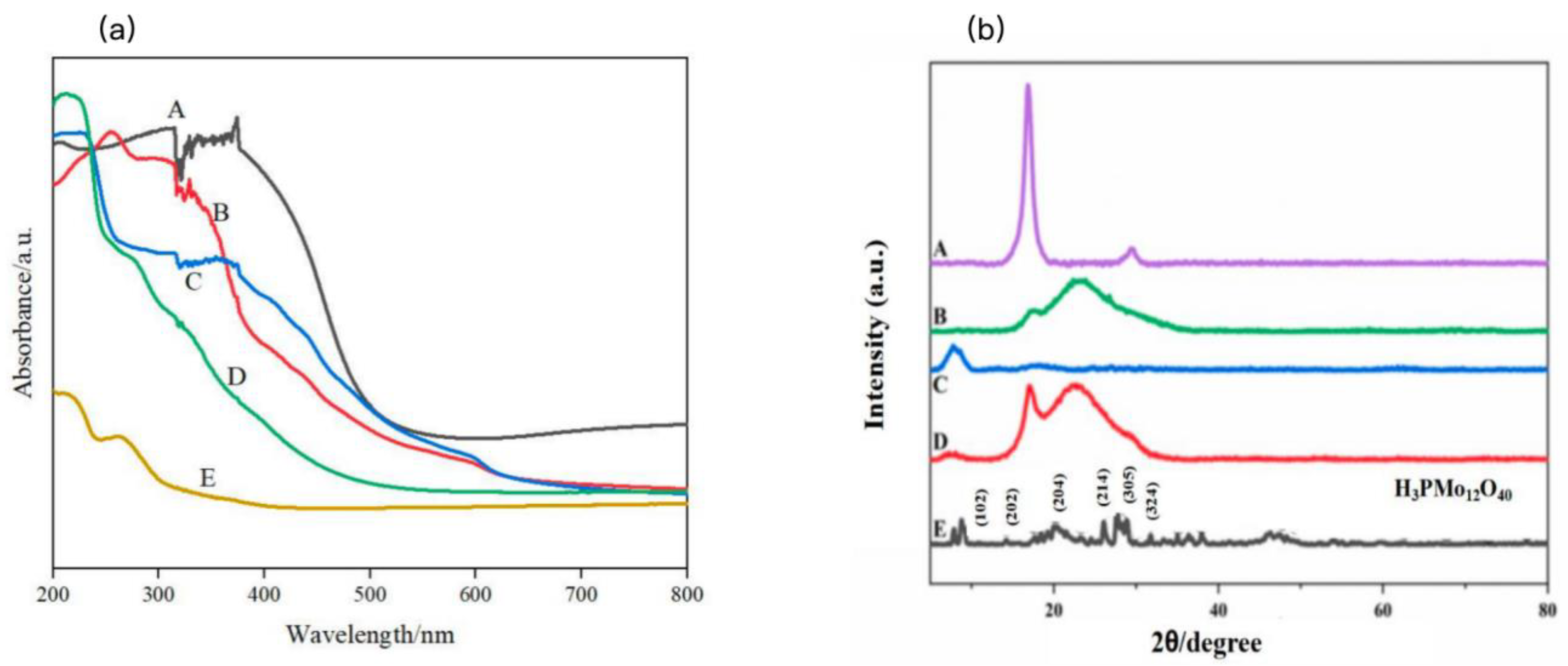

To investigate the light absorption properties of the raw materials and their modified products, UV–visible diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS) was conducted on polyacrylonitrile (PAN), PMo, PVPy, brominated poly(ionic liquid) (Br-PIL), and PM-PIL nanofiber (NF) membranes. The corresponding spectra are shown in

Figure 3a. As expected, pristine PAN exhibits negligible absorption in both the ultraviolet and visible light regions, indicating its photo-inactive nature. Similarly, pure PMo shows almost no absorption in the visible region (>400 nm), which significantly limits its photocatalytic performance under visible light irradiation.

In contrast, the PM-PIL NF membrane displays pronounced absorption across both the ultraviolet and visible regions. This enhanced light-harvesting capability can be attributed to the charge transfer characteristics of the poly(ionic liquid) framework, which effectively extends the light response of PMo into the visible region[

47]. These results suggest that the PIL matrix plays a crucial role in improving the visible-light utilization efficiency of the PMo photocatalyst. Based on the UV–vis DRS data and calculated using the Kubelka–Munk function, the band gap energy of PM-PIL was determined to be 3.09 eV, which is favorable for visible-light-driven photocatalytic reactions.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were performed to examine the crystalline structures of PAN, PMo, PVPy, Br-PIL, and PM-PIL, and the results are presented in

Figure 3b. The PAN NF membrane exhibits a diffraction peak in the 2θ range of 16–17°, which is attributed to the (100) plane of the hexagonal crystal system[

48]. Additionally, a weaker diffraction peak observed at approximately 28–29° corresponds to the (110) plane. In the XRD pattern of PVPy, the (100) diffraction peak at 2θ = 17° shows a noticeable shift, accompanied by other structural changes, which can be ascribed to the introduction of pyridine units and the resulting alteration of the polymer crystal structure.

For PMo, characteristic diffraction peaks are observed at 2θ values of approximately 10°, 20°, 23°, 25°, 28°, and 31°, corresponding to the (110), (200), (220), (310), (222), and (400) crystal planes, respectively. These diffraction features are in good agreement with the standard XRD pattern of PMo reported in the literature[

49] and match well with the data from JCPDS card No. 50-0657, confirming the high crystallinity and phase purity of PMo.

The XRD pattern of Br-PIL shows a diffraction peak at 2θ = 17°, similar to that of PVPy, while the signal at approximately 29° is significantly weakened[

50]. A comparison between the Br-PIL and PVPy patterns indicates that the ionization process has a limited influence on the crystalline structure of PVPy. Notably, in the XRD pattern of PM-PIL, no impurity peaks are detected, demonstrating the high purity of the composite material. Compared with PAN, the diffraction peaks at 2θ = 17° and 29° disappear, while two new peaks emerge at 2θ values of approximately 8° and 23°, which can be assigned to the (200) and (001) crystal planes of PMo, respectively. These results further confirm the successful incorporation of PMo into the PIL NF membrane and the formation of the PM-PIL composite.

Overall, the UV–vis DRS and XRD analyses collectively demonstrate that the introduction of the PIL framework not only significantly enhances the visible-light absorption capability of PMo but also enables its stable immobilization within the nanofiber membrane without generating impurity phases. This synergistic combination of optical and structural advantages is expected to play a key role in the excellent visible-light photocatalytic performance of the PM-PIL NF membrane.

2.4. Visible-Light Photocatalytic Degradation Analysis

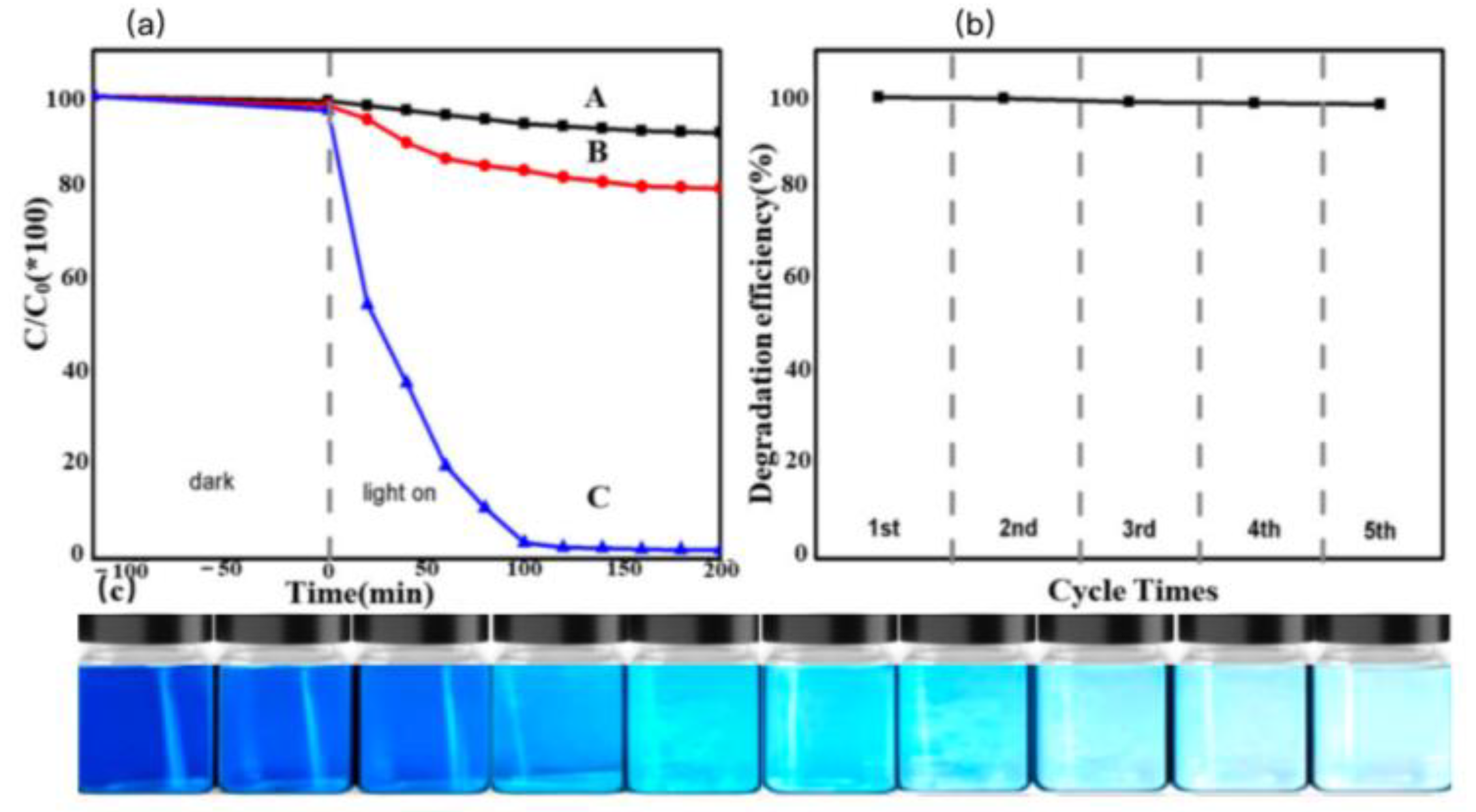

The photocatalytic performance of the PM-PIL NF membrane was evaluated through the degradation of methyl blue (MB) in an aqueous solution under visible light irradiation. MB, a typical azo dye, contains chromophoric azo groups that are primarily degraded via oxidative pathways. In the presence of oxidizing agents such as polyoxometalates (POMs) or ozone, the azo bonds undergo oxidative cleavage, leading to dye decolorization and mineralization. Therefore, MB was selected as a model pollutant to assess the visible-light-driven photocatalytic activity of the PM-PIL catalyst, and the corresponding degradation results are presented in

Figure 4a [

51].

To clarify the role of PM-PIL in the photocatalytic process, control experiments were conducted under identical conditions, including reactions without any catalyst and reactions using a simple physical mixture of polyacrylonitrile (PAN) and PMo. During the photocatalytic experiments, aliquots were withdrawn at regular intervals, and the concentration of MB was monitored by recording the UV–vis absorption spectra. As shown in

Figure 4a, the degradation efficiency of MB under dark conditions was only approximately 1%, indicating negligible adsorption or self-degradation of MB in the absence of light irradiation.

In contrast, under visible light irradiation, the PM-PIL NF membrane exhibited outstanding photocatalytic activity, achieving up to 98% degradation of MB within the same reaction time. The gradual color fading of the MB aqueous solution during the reaction process is clearly illustrated in

Figure 4c, further confirming the efficient photocatalytic degradation capability of PM-PIL. These results demonstrate that PM-PIL acts as an effective visible-light photocatalyst for MB degradation, benefiting from the synergistic interaction between PMo and the poly(ionic liquid) nanofiber matrix[

52,

53].

Moreover, as shown in

Figure 4a,b, the photocatalytic degradation efficiency of MB reached only about 20% when a simple PAN/PMo mixture was used under the same experimental conditions. This significantly lower activity highlights the critical role of the PIL framework in enhancing photocatalytic performance. The immobilization of PMo within the PIL NF membrane not only improves light absorption and charge separation efficiency but also promotes effective contact between the catalyst and the dye molecules. Consequently, the PM-PIL composite membrane exhibits superior photocatalytic efficiency compared to physically mixed systems.

Overall, these results clearly demonstrate that the rational design of PM-PIL NF membranes enables efficient visible-light-driven degradation of MB, outperforming conventional polymer-supported or physically blended photocatalysts. This enhanced performance can be attributed to the improved light-harvesting capability, effective charge transfer, and stable immobilization of PMo within the PIL nanofiber network, making PM-PIL a promising candidate for practical wastewater treatment applications.

The recyclability of heterogeneous photocatalysts is a critical factor for their practical application. To evaluate the reusability of the PM-PIL nanofiber (NF) membrane, the catalyst was recovered from the photocatalytic reaction system after each cycle, thoroughly washed with deionized water and ethanol three times, and then dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C for 8 h. The regenerated PM-PIL NF membrane was subsequently reused for the next photocatalytic degradation experiment under identical conditions.

As shown in

Figure 4b, the PM-PIL NF membrane exhibits excellent cycling stability. After five consecutive photocatalytic cycles, the degradation efficiency of methyl blue remained as high as 98% of the initial value, indicating negligible loss of photocatalytic activity. This outstanding reusability demonstrates that PM-PIL is not only an efficient visible-light photocatalyst but also a robust and durable material suitable for repeated use.

The superior recyclability of the PM-PIL NF membrane can be attributed to its freestanding nanofiber membrane structure, which enables facile separation from the reaction system without the need for additional centrifugation or filtration steps typically required for powder-based catalysts. Moreover, the strong electrostatic (Coulombic) interactions between the negatively charged PMo anions and the positively charged pyridinium groups within the PIL framework play a crucial role in stabilizing the immobilized photocatalyst. These interactions effectively suppress PMo leaching during the photocatalytic process, thereby maintaining high catalytic activity over multiple cycles.

Overall, the combination of structural integrity, strong electrostatic immobilization, and membrane-based morphology endows the PM-PIL NF membrane with excellent reusability and operational stability. These advantages significantly enhance its potential for practical applications in wastewater treatment, offering a cost-effective, efficient, and recyclable solution for visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants.

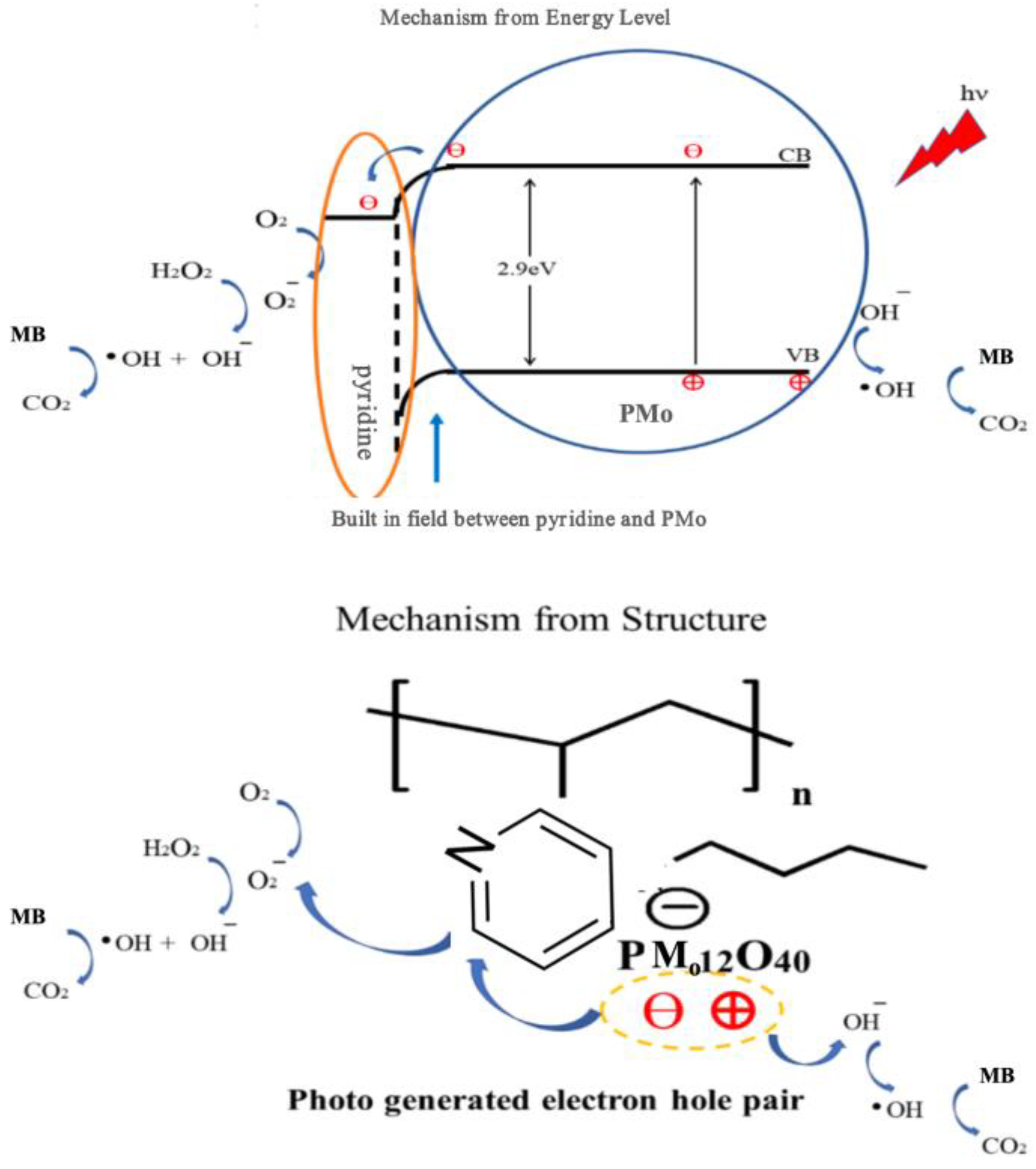

2.5. Photocatalytic Mechanism Analysis

Based on the molecular energy levels and structural characteristics of the PM-PIL NF membrane, a plausible visible-light-driven photocatalytic mechanism is proposed and illustrated in

Figure 5. According to the UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS) results, the PM-PIL composite exhibits a band gap energy of 3.09 eV, indicating its ability to absorb a broad range of ultraviolet and visible light. Further analysis using the Kubelka–Munk model suggests that the photogenerated electron migration energy of PM-PIL reaches approximately 0.09 eV, demonstrating efficient visible-light absorption and charge transfer capability within the composite material [

54].

The enhanced photocatalytic performance of PM-PIL can be attributed to the strong electrostatic interaction between the positively charged pyridinium groups in the poly(ionic liquid) matrix and the negatively charged PMo anions. This Coulombic interaction induces the formation of an internal electric field at the PMo–PIL interface, which effectively promotes the separation and directional migration of photogenerated charge carriers. As a result, the recombination of electron–hole pairs is significantly suppressed, thereby improving the overall photocatalytic efficiency.

Previous studies have shown that polyoxometalates (POMs) can be regarded as low-dimensional semiconductor-like materials with well-defined valence band (VB) and conduction band (CB) structures[

55]. Under visible light irradiation, electrons in PMo are excited from the VB to the CB. The photogenerated electrons in the CB subsequently react with dissolved oxygen (O₂) adsorbed on the catalyst surface to generate superoxide radicals (O₂•⁻). Simultaneously, the photogenerated holes remaining in the VB interact with hydroxide ions (OH⁻) or water molecules to produce highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (•OH). These reactive oxygen species (ROS) play a dominant role in the oxidative degradation of methyl blue molecules adsorbed on the catalyst surface.

Furthermore, hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), employed as an initiator in the reaction system, serves as an effective electron acceptor and ROS promoter. H₂O₂ can react with both •OH and O₂•⁻ radicals to generate additional reactive oxygen species, thereby accelerating the photocatalytic degradation process and enhancing the overall reaction kinetics[

56,

57,

58]. The synergistic effects of efficient light absorption, internal electric field-assisted charge separation, and abundant ROS generation collectively account for the outstanding visible-light photocatalytic activity of the PM-PIL NF membrane.

In summary, the rational integration of PMo within the PIL nanofiber matrix not only improves light-harvesting capability but also facilitates charge carrier separation and transfer through electrostatic interactions. This synergistic mechanism under visible light irradiation endows the PM-PIL NF membrane with superior photocatalytic performance, providing valuable insights for the design of advanced polymer-supported photocatalysts for environmental remediation.

3. Experiment

3.1. Materials and Methods

Polyacrylonitrile nanofiber (PAN NF, average molecular weight = 150,000) electrospun membranes were purchased from Fushun Petrochemical Company (Fushun, China). N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), propylenediamine, toluene, ethanol, phosphomolybdic acid (PMo), 1-bromobutane, methyl blue (MB), ethylene glycol, and acetone were obtained from Aladdin Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All chemical reagents used in this study were of analytical grade and were used as received without further purification.

Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were recorded using a Nicolet iS50 FT-IR spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to identify the chemical structures of the samples. The surface morphology and microstructure of the nanofiber membranes were observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Hitachi S-4800, Hitachi Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were collected on a Rigaku D/MAX-2500 diffractometer (Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.15406 nm) to analyze the crystalline structures of the materials.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were carried out using a PHI 5000 VersaProbe III system (Physical Electronics, Chanhassen, MN, USA) to determine the surface elemental composition and chemical states. UV–visible diffuse reflectance spectra (UV–vis DRS) were obtained on a UV–vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-2600, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with an integrating sphere, and BaSO₄ was used as the reflectance standard. Photocatalytic degradation experiments were conducted under visible light irradiation using a 300 W xenon lamp (CEL-HXF300, CEAULight, Beijing, China) with a 420 nm cutoff filter to eliminate ultraviolet light.

3.2. Sample Preparation

3.2.1. Sample Preparation for Pyridine-Containing Polymer Membrane (PVPy)

Polyacrylonitrile nanofiber (PAN NF) membranes (200 mg) were cut into small pieces and immersed in a mixed solution containing ethylene glycol (2 mL), propylenediamine (2 mL), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, 20 mL), and deionized water (20 mL). The reaction mixture was heated to 80 °C and maintained under a nitrogen atmosphere for 4 h to promote the cyclization reaction of the nitrile groups.

After completion of the reaction, the mixture was allowed to cool naturally to room temperature. The resulting modified membranes were thoroughly washed with deionized water and acetone three times to remove residual reagents and by-products. Finally, the membranes were dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C for 8 h to obtain pyridine-functionalized poly(2-vinylpyridine) nanofiber membranes, denoted as PVPy[

7].

3.2.2. Sample Preparation for Bromide-Based Poly(ionic liquid) Nanofiber Membrane (Br-PIL)

Pyridine-functionalized nanofiber membranes (PVPy NFs, 100 mg) were placed in a reaction flask containing N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, 40 mL). Subsequently, 1 mL of 1-bromobutane was added to the system. The reaction mixture was heated to 80 °C and maintained at this temperature for 24 h to allow the quaternization reaction to proceed.

After completion of the reaction, the system was cooled naturally to room temperature. The resulting light-yellow membranes were collected and thoroughly washed with deionized water and ethanol three times to remove unreacted reagents and residual solvent. Finally, the membranes were dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C for 8 h to obtain the bromide-containing poly(ionic liquid) nanofiber membranes, denoted as Br-PIL.

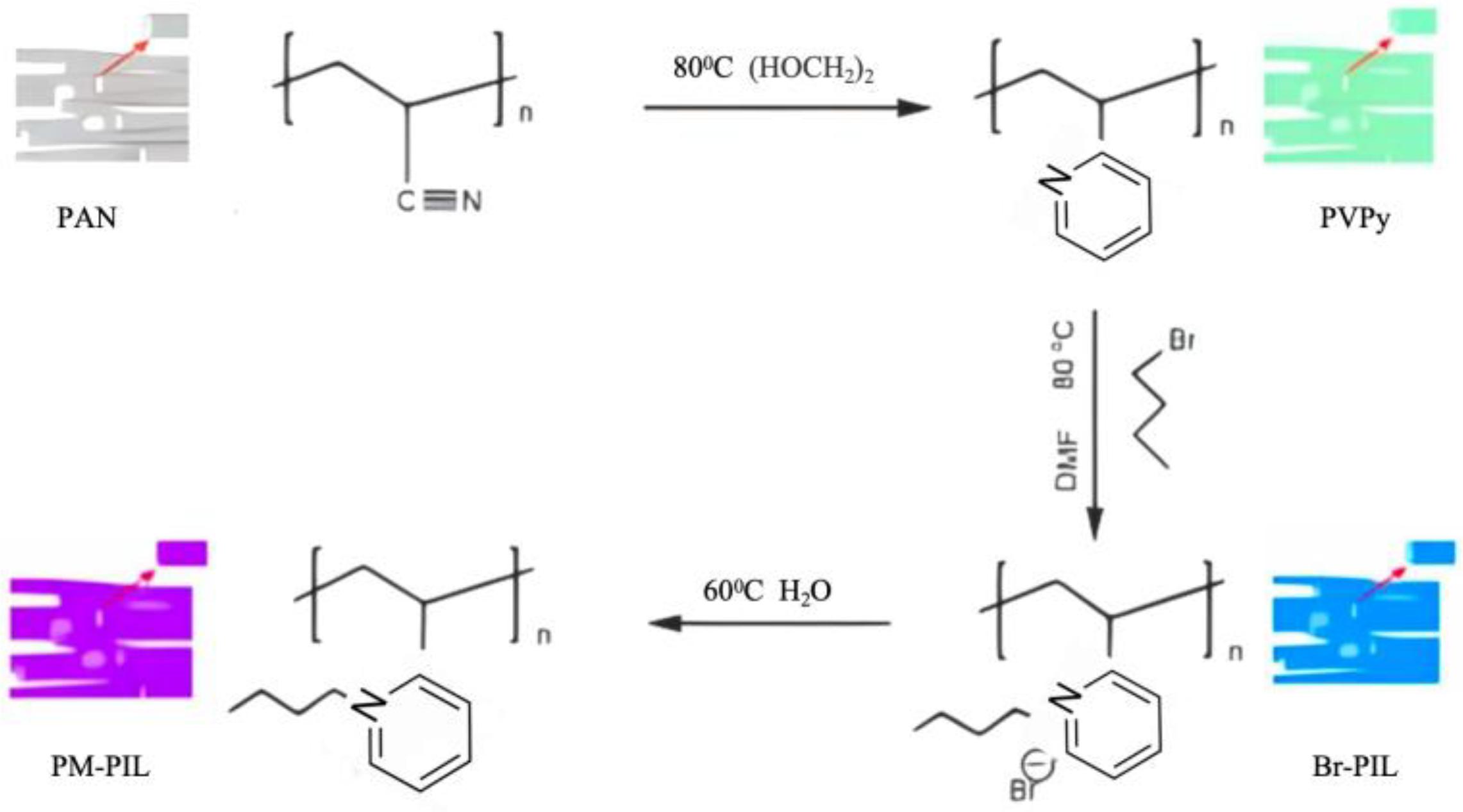

3.2.3. Sample Preparation for PMo-Based Poly(ionic liquid) Nanofiber Membrane (PM-PIL)

Phosphomolybdic acid (PMo, 100 mg) and bromide-containing poly(ionic liquid) nanofiber membranes (Br-PIL, 20 mg) were dispersed in deionized water (40 mL). The mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 4 h to complete the anion exchange process.

After the reaction, the resulting gray–green membranes were collected and washed thoroughly with deionized water three times to remove excess PMo and residual bromide ions. Subsequently, the membranes were dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C for 8 h. The final product, a poly(1-butyl-2-vinylpyridinium) phosphomolybdate nanofiber membrane with PMo₁₂O₄₀³⁻ as the counter anion, was obtained and denoted as PM-PIL (as illustrated in

Figure 6).

3.2.4. Sample Preparation for PM-PIL Nanofiber Membrane

The synthesis route of the PM-PIL nanofiber (NF) membrane is illustrated in Scheme 1. Briefly, polyacrylonitrile (PAN) nanofiber membranes were first prepared by an electrospinning process. The nitrile groups in the PAN nanofibers were subsequently converted into pyridine functionalities through a cyclization reaction with propylenediamine, yielding pyridine-containing poly(2-vinylpyridine) nanofiber membranes, denoted as PVPy.

The obtained PVPy NF membranes were then subjected to a quaternization reaction with 1-bromobutane to generate bromide-based poly(ionic liquid) nanofiber membranes (Br-PIL). Finally, an anion exchange reaction between Br-PIL and phosphomolybdic acid (PMo) was carried out to replace Br⁻ with PMo₁₂O₄₀³⁻, leading to the successful fabrication of PMo-based poly(ionic liquid) nanofiber membranes, referred to as PM-PIL.

This stepwise modification strategy enables the retention of the nanofibrous membrane morphology while introducing ionic liquid functionalities and photocatalytically active PMo species, providing a robust platform for visible-light-driven photocatalytic applications.

3.3. Photocatalytic Degradation of Methyl Blue and Recycling Tests

The photocatalytic performance of the samples was evaluated by the visible-light-driven degradation of methyl blue (MB) in an aqueous solution. A 500 W xenon lamp (CHFXQ500W, Beijing Chengxin Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) equipped with a 400 nm cutoff filter was used as the visible light source to eliminate ultraviolet irradiation. The light intensity was adjusted to 100 mW cm⁻².

The photocatalytic degradation experiments were carried out in an aqueous system. Typically, 20 mg of PM-PIL nanofiber (NF) membrane and 10 mL of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) were added to 20 mL of MB aqueous solution with an initial concentration of 50 ppm. Prior to light irradiation, the suspension was magnetically stirred in the dark for 120 min to establish adsorption–desorption equilibrium. Subsequently, the reaction system was irradiated under visible light at room temperature for 2 h to initiate the photocatalytic degradation process.

For comparison, control experiments were performed under identical conditions without adding any photocatalyst or by using a physical mixture of PAN and PMo instead of PM-PIL. During the photocatalytic reaction, aliquots were withdrawn at regular intervals (every 20 min), and the residual concentration of MB was monitored by measuring the UV–vis absorption spectra of the solution.

To investigate the recyclability of the supported photocatalyst, the PM-PIL NF membrane was removed from the reaction system after each photocatalytic cycle, washed sequentially with deionized water and ethanol three times, and then dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C for 8 h. The regenerated membrane was reused for subsequent photocatalytic degradation experiments under the same conditions.

3.4. Characterization Methods

The surface morphology of the samples was examined using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Hitachi S-4800, Hitachi Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) operated at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. The UV–visible absorption spectra of liquid samples were recorded using a UV–vis spectrophotometer (TU-1901, Purkinje General Instrument Co., Ltd., Beijing, China).

The UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectra (DRS) of solid samples were obtained using a Shimadzu UV-2550 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with an integrating sphere, with BaSO₄ employed as the reflectance standard. The wavelength range for DRS measurements was set from 200 to 800 nm.

Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were collected on a PerkinElmer Spectrum 1600 FT-IR spectrometer (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) to analyze the chemical structures of the samples. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded using a Rigaku D/max-2500 diffractometer (Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.15406 nm) operated at 40 kV and 150 mA. The diffraction data were collected over a 2θ range of 5°–90°.

The anion exchange degree and surface elemental composition of the samples were determined by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, ESCA MK II, Kratos Analytical Ltd., Manchester, UK). Photoluminescence (PL) spectra were recorded using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (FS5-TCSPC, Edinburgh Instruments Ltd., Livingston, UK) equipped with a 150 W ozone-free xenon lamp as the excitation source.

4. Conclusions

In summary, a robust, flexible, and recyclable poly(ionic liquid) (PIL) nanofiber (NF) membrane was successfully fabricated by sequential cyclization, quaternization, and anion exchange modification of low-cost polyacrylonitrile (PAN) nanofiber membranes. The resulting PM-PIL NF membrane effectively immobilized polyoxometalate (POM) photocatalysts and was applied to visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation reactions in aqueous systems.

The PM-PIL membrane exhibited excellent photocatalytic performance, achieving a degradation efficiency of approximately 98% under visible light irradiation, while maintaining nearly unchanged catalytic activity after five consecutive recycling cycles. The outstanding stability and reusability of the membrane can be attributed to the strong electrostatic interactions between the negatively charged POM anions and the positively charged pyridinium groups within the PIL framework, as well as the freestanding nanofiber membrane structure that enables facile recovery without additional separation steps.

From an economic perspective, conventional PILs are expensive, with market prices reaching approximately USD 150,000 per kilogram, whereas PAN is several orders of magnitude less costly. By using PAN as a precursor, the overall material cost is significantly reduced, making the proposed strategy economically attractive. Moreover, unlike powder-based photocatalysts that require energy-intensive centrifugation for recovery, the membrane-based photocatalyst offers a simple and efficient recycling process.

To the best of our knowledge, this work represents the first report on a PM-PIL photocatalyst. The low-cost, functionalized PIL NF membrane developed in this study demonstrates strong potential for large-scale production and provides an economical and sustainable approach for visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation. By utilizing solar energy as a clean and renewable light source, this photocatalytic membrane system offers a promising pathway toward environmentally friendly and sustainable processes. Future research will focus on the development of photocatalysts with enhanced visible-light activity and the expansion of their applications in environmental remediation and beyond.

Author Contributions

Material preparation, catalytic experiments and writing—original draft, Y.G.; writing—review and editing, X.Q.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Xing, Zhi et al. “Electrospun polymer nanofiber composites incorporating metal–organic frameworks and mesoporous carbon for enhanced CO₂ capture and VOC removal.” Journal of Hazardous Materials (2024): in press.

- Wang, Xiaoqiong et al. “In situ construction of covalent organic framework membranes on polyacrylonitrile nanofibers for efficient carbon dioxide capture.” ACS Applied Nano Materials 7.5 (2024): 3150–3162. [CrossRef]

- Yalçınkaya, Tuğçe Töngüç et al. “Polyacrylonitrile and polyacrylonitrile/cellulose-based activated carbon nanofibers from textile wastes for carbon dioxide adsorption.” Journal of Applied Polymer Science 141.3 (2024): 55475.

- Li, Wei et al. “Preparation of cationic polymer nanofiber adsorbents with embedded anionic sites for efficient precious metal ion recovery from waste streams.” Separation and Purification Technology (2025): in press.

- Zhang, Li et al. “Recent advances in electrospun nanofibrous membranes for effective chromium(VI) removal from water: mechanisms, performance, and prospects.” Chemical Engineering Journal 459 (2023): 141933.

- Zhang, Yeke, et al. “Recyclable ZnIn₂S₄/PAN Photocatalytic Nanofiber Membrane for Enhanced Visible-Light-Driven Hydrogen Evolution and Pollutant Degradation.” Applied Catalysis B: Environment and Energy (2024): in press.

- Li, Hongzhang, Xinhua Liu, Eryan Chi, and Guocai Xu. “Phytic Acid Modified Polyacrylonitrile Nanofiber Membranes: Fabrication, Characterization, and Optimization for Pb²⁺ Adsorption.” Polymer Engineering & Science (2024): in press. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jihyun, et al. “Functionalized Polyacrylonitrile Nanofiber Membranes with Carbonic Anhydrase for Enhanced Aqueous CO₂ Capture and Selectivity.” Journal of Membrane Science 687 (2024): 121852.

- Liu, Xiaoming, et al. “Gradient Wettability PAN Nanofiber Membranes for High-Performance Water Treatment and Air Filtration.” Separation and Purification Technology 303 (2025): 122174.

- Wang, Peng, Jie Zheng, Xue-Hao Li, et al. “Carbon Nanofiber Catalysts Containing High-Entropy Metal Phosphides for Efficient Hydrogen Evolution.” Rare Metals (2024): in press.

- Huang, Min, et al. “Porous Polyacrylonitrile Nanofiber Membranes Modified with UiO-66-NH₂ for Enhanced Dye Adsorption and Photocatalytic Degradation.” Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 635 (2024): 1123–1134.

- Kim, Soyoung, et al. “Ionic Liquid-Integrated Electrospun PAN/IL Composite Membranes for High-Efficiency Removal of Sulfonamide Antibiotics from Water.” Journal of Hazardous Materials 454 (2024): 131455.

- Patel, Aarav, and Meena Gupta. “Modification of PAN Nanofiber Membranes with g-C₃N₄ and Carbon Dots for High-Performance Wastewater Treatment Applications.” Chemosphere 323 (2024): 137220.

- Singh, Rajeev, et al. “Advanced Electrospun PAN-Based Nanofiber Membrane Composites for Multiphase Separation and Pollutant Removal in Water Systems.” Environmental Science: Nano 11.7 (2024): 1845–1868.

- Chen, Wei, et al. “Integrated PES/PAN Electrospun Nanofiber Membrane with Ionic Liquids for Enhanced Heavy Metal Ion Separation.” Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 13.4 (2024): 110567.

- Liu, Jing, et al. “Recent progress in photocatalytic membrane reactors for environmental remediation: design strategies, performance improvement and practical challenges.” Journal of Membrane Science 655 (2024): 121085.

- Singh, Amandeep, and Rachna Sharma. “Advances in polymer–semiconductor hybrid photocatalysts for integrated solar energy conversion and pollutant degradation.” Applied Surface Science 616 (2024): 157858.

- Chen, Xiaoyu, et al. “Facile synthesis of polyoxometalate-grafted g-C3N4 nanosheets with enhanced photocatalytic CO₂ reduction under visible light.” Journal of Materials Chemistry A 13.12 (2025): 2048–2060.

- Zhao, Wenxuan, et al. “Carbon quantum dots coupled heterostructure photocatalysts for boosted phenolic pollutant degradation and mechanistic insights.” Optical Materials 105 (2024): 112027.

- Yang, Haoran, et al. “Recent advances in polyoxometalate-based nano-architectures for photocatalysis and energy conversion.” Advanced Functional Materials 35.8 (2025): 2408321.

- Nakamura, Ryota, et al. “Tailored gold–platinum alloy clusters stabilized by polyoxometalates for enhanced photocatalytic oxidation of organic pollutants.” Angewandte Chemie International Edition 64.3 (2025): e202414123.

- Zhang, Qiang, et al. “Janus composite membranes with spatial catalytic sites for simultaneous oil–water separation and photocatalytic degradation of dyes.” Chemical Engineering Journal 457 (2024): 141635.

- Li, Mingyu, et al. “Interface-engineered electrospun nanofiber membranes with dual functionality for continuous visible-light photocatalysis and antibacterial performance.” ACS Applied Polymer Materials 7.5 (2025): 3249–3260.

- Wu, Liang, et al. “Electrospun nanofiber supported MOF–TiO₂ hybrid membranes for enhanced photocatalytic pharmaceutical decomposition.” Science of The Total Environment 871 (2024): 161074.

- Gupta, Pooja, and Harish Vashisth. “Recent trends in TiO₂-based photocatalytic membranes for pharmaceutical and personal care product removal from water: materials, mechanisms, and future prospects.” Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology 10.4 (2025): 413–444.

- Li, Yifan, et al. “Design of robust ceramic–polymer hybrid photocatalytic membranes for long-term wastewater treatment under visible light.” Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 12.1 (2024): 111234.

- Park, Minseok, et al. “Durable TiO₂-based photocatalytic membranes with enhanced UV resistance and fouling mitigation for continuous water treatment.” Water Research 247 (2024): 120781.

- Zhao, Rui, et al. “Self-supporting carbon nanotube/TiO₂ composite membranes with improved visible-light photocatalytic degradation performance.” Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 444 (2024): 114825.

- Al-Khaldi, Faisal, et al. “Visible-light-responsive PES/TiO₂-Ag composite membranes for pharmaceutical removal: performance and stability evaluation.” Desalination 575 (2024): 116992.

- Sun, Xiaolong, et al. “Graphene-oxide-modified photocatalytic membranes with synergistic antifouling and dye degradation properties.” Separation and Purification Technology 330 (2024): 125104.

- Kim, Hyunsoo, et al. “Electrospun nanofiber-based photocatalytic membranes for continuous antibiotic removal in photocatalytic membrane reactors.” Chemical Engineering Journal 468 (2024): 143655.

- Morales-Torres, Silvia, et al. “Advanced photocatalytic membrane reactors for emerging contaminant removal: materials, reactor design and scale-up challenges.” Catalysts 14.2 (2024): 167.

- Zhang, Yuchen, et al. “Visible-light-enhanced ZnIn₂S₄-coated PVDF membranes for continuous photocatalytic degradation of antibiotics.” Journal of Membrane Science 682 (2024): 121902.

- Rahimi, Ali, et al. “Multifunctional graphene-based membranes integrating photocatalytic and antimicrobial properties for wastewater treatment.” Membranes 14.1 (2024): 56.

- Chen, Haoran, et al. “Recent advances in photocatalytic membranes for fouling-resistant water and wastewater treatment.” Progress in Materials Science 140 (2025): 101178.

- Wang, Yiming, et al. “Superhydrophilic photocatalytic membranes for efficient oil–water separation and self-cleaning under visible light.” Desalination 603 (2025): 118642.

- Chen, Zhenyu, et al. “Recent advances in photocatalytic ceramic membranes for water purification: materials design and long-term stability.” Journal of Materials Science & Technology 190 (2025): 45–63.

- Li, Xiaotong, et al. “Electrospun nanofibrous membranes with integrated photocatalytic and antifouling properties for sustainable wastewater treatment.” Chemical Engineering Journal 475 (2024): 146210.

- Sun, Qiang, et al. “Surface-modified PVDF membranes incorporated with TiO₂ for enhanced photocatalytic activity and fouling resistance.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research 31.12 (2024): 15678–15690.

- Zhang, Rui, et al. “Visible-light-driven photocatalytic membranes for oil–water separation and dye degradation: mechanisms and applications.” Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 12.4 (2024): 110987.

- Liu, Haifeng, et al. “Multifunctional electrospun nanofiber membranes with superhydrophilicity and photocatalytic self-cleaning for water treatment.” Langmuir 41.6 (2025): 3124–3136.

- Kim, Jisoo, et al. “Photocatalytic TiO₂-based membranes: recent progress in material engineering and environmental applications.” Catalysts 14.5 (2024): 512.

- Zhao, Peng, et al. “Hybrid photocatalytic membranes with enhanced visible-light response for continuous degradation of organic pollutants.” Journal of Membrane Science 692 (2024): 122013.

- Alavi, Mehrdad, et al. “Advanced photocatalytic membranes for antifouling and self-cleaning water treatment systems.” Progress in Materials Science 138 (2025): 101132.

- Xu, Linyan, et al. “Electrospun polymer nanofiber membranes decorated with metal oxide nanoparticles for photocatalytic wastewater treatment.” Separation and Purification Technology 341 (2024): 123456.

- Huang, Zhiwei, et al. “Recent developments in superhydrophilic and underwater superoleophobic membranes for oil–water separation.” Water Research 256 (2024): 121512.

- Deng, Wei, et al. “Visible-light-responsive photocatalytic membranes based on carbon–semiconductor composites.” Applied Surface Science 642 (2024): 158924.

- Li, Wenbo, et al. “Electrospun nanofiber-based photocatalytic membranes for emerging contaminant removal: design and performance.” Science of The Total Environment 889 (2024): 164012.

- Park, Seungmin, et al. “Recent progress in photocatalytic self-cleaning membranes for water and wastewater treatment.” Membranes 15.2 (2025): 89.

- Gao, Shengnan, et al. “Integration of photocatalytic and adsorption functionalities in nanofibrous membranes for efficient pollutant removal.” Journal of Hazardous Materials 466 (2024): 132845.

- Gao, Y.; Meng, Q.-B.; Wang, B.-X.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, H.; Fang, D.-W.; Song, X.-M. Polyacrylonitrile Derived Robust and Flexible Poly(ionic liquid)s Nanofiber Membrane as Catalyst Supporter. Catalysts 2022, 12, 266. [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Gao, Y.; Xia, W.; Qi, X. Preparation of Bi@Ho3+:TiO2/Composite Fiber Photocatalytic Materials and Hydrogen Production via Visible Light Decomposition of Water. Catalysts 2024, 14, 588. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Cao, T.; Du, J.; Qi, X.; Yan, H.; Xu, X. The Bi-Modified (BiO)2CO3/TiO2 Heterojunction Enhances the Photocatalytic Degradation of Antibiotics. Catalysts 2025, 15, 56. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Feng, T.; Qi, X.; Yan, H.; Du, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. Vacuum-Treated Brown Mesoporous TiO2 Nanospheres with Tailored Defect Structures for Enhanced Photoresponsive Properties. Molecules 2025, 30, 4746. [CrossRef]

- Li, Jiawei, et al. “Recent advances in polyoxometalate-based photocatalysts for environmental remediation.” Catalysis Today 430 (2024): 114–126.

- Gao, Y.; Li, N.; Qi, X.; Zhou, F.; Yan, H.; He, D.; Xia, W.; Zhang, Y. A Dual Photoelectrode System for Solar-Driven Saltwater Electrolysis: Simultaneous Production of Chlorine and Hydrogen. Crystals 2025, 15, 233. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Yuchen, et al. “Mechanistic insights into visible-light-driven dye degradation over polyoxometalate-based photocatalysts.” Langmuir 40.18 (2024): 9645–9656.

- Sun, Peng, et al. “Recent developments of photocatalytic membranes incorporating polyoxometalates for wastewater treatment.” Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 13.1 (2025): 110892.

Figure 1.

(a) FT-IR spectra of PAN (A), PMoPIL (B), Br-PVPy (C), PMo (D), and PVPy (E). (b) SEM images of the PAN NF membranes (A–C) at different magnifications ;SEM images of the PMo–PIL NF membranes (D–F) at corresponding magnifications (scale bars: 2 μm, 200 nm, and 100 nm, respectively).

Figure 1.

(a) FT-IR spectra of PAN (A), PMoPIL (B), Br-PVPy (C), PMo (D), and PVPy (E). (b) SEM images of the PAN NF membranes (A–C) at different magnifications ;SEM images of the PMo–PIL NF membranes (D–F) at corresponding magnifications (scale bars: 2 μm, 200 nm, and 100 nm, respectively).

Figure 2.

(a) XPS survey spectra of PAN (A), PMo (B), Br-PVPy (C), and PMo–PIL (D). (b) High-resolution N 1s XPS spectrum of PMo–PIL. (c) High-resolution C 1s XPS spectrum of PMo–PIL.

Figure 2.

(a) XPS survey spectra of PAN (A), PMo (B), Br-PVPy (C), and PMo–PIL (D). (b) High-resolution N 1s XPS spectrum of PMo–PIL. (c) High-resolution C 1s XPS spectrum of PMo–PIL.

Figure 3.

(a) UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectra (DRS) of PMo–PIL (A), PMo (B), Br-PVPy (C), PVPy (D), and PAN (E). (b) X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of PAN (A), Br-PVPy (B), PMo–PIL (C), PVPy (D), and PMo (E).

Figure 3.

(a) UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectra (DRS) of PMo–PIL (A), PMo (B), Br-PVPy (C), PVPy (D), and PAN (E). (b) X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of PAN (A), Br-PVPy (B), PMo–PIL (C), PVPy (D), and PMo (E).

Figure 4.

(a) UV–vis absorption evolution of methylene blue (MB) during the dark adsorption stage and the subsequent photocatalytic degradation under visible-light irradiation: (A) MB without photocatalyst, (B) MB in the presence of PAN/PMo blended sample, and (C) MB in the presence of PM–PIL under visible light. (b) Recyclability of the immobilized photocatalyst PM–PIL for MB photodegradation (catalyst loading: 1 mg mL⁻¹; 20 mg catalyst dispersed in 20 mL aqueous solution; Mo concentration: 50 ppm). Aliquots were collected every 100 min for a total of five samples. (c) Digital photographs showing the macroscopic appearance changes of the MB aqueous solution recorded every 10 min during the photocatalytic degradation process.

Figure 4.

(a) UV–vis absorption evolution of methylene blue (MB) during the dark adsorption stage and the subsequent photocatalytic degradation under visible-light irradiation: (A) MB without photocatalyst, (B) MB in the presence of PAN/PMo blended sample, and (C) MB in the presence of PM–PIL under visible light. (b) Recyclability of the immobilized photocatalyst PM–PIL for MB photodegradation (catalyst loading: 1 mg mL⁻¹; 20 mg catalyst dispersed in 20 mL aqueous solution; Mo concentration: 50 ppm). Aliquots were collected every 100 min for a total of five samples. (c) Digital photographs showing the macroscopic appearance changes of the MB aqueous solution recorded every 10 min during the photocatalytic degradation process.

Figure 5.

Schematic illustration of the band structure of PM–PIL and the photogenerated charge-carrier separation/transfer behavior under light irradiation, showing the excitation of electrons from the valence band to the conduction band and the corresponding hole formation, as well as the subsequent charge separation and migration processes.

Figure 5.

Schematic illustration of the band structure of PM–PIL and the photogenerated charge-carrier separation/transfer behavior under light irradiation, showing the excitation of electrons from the valence band to the conduction band and the corresponding hole formation, as well as the subsequent charge separation and migration processes.

Figure 6.

Schematic illustration of the synthetic routes for PVPy, Br–PIL, and PM–PIL, including the preparation of pyridine-functionalized polymer (PVPy), subsequent quaternization to obtain Br–PIL, and the final assembly/ion-exchange with PMo to form PM–PIL.

Figure 6.

Schematic illustration of the synthetic routes for PVPy, Br–PIL, and PM–PIL, including the preparation of pyridine-functionalized polymer (PVPy), subsequent quaternization to obtain Br–PIL, and the final assembly/ion-exchange with PMo to form PM–PIL.

Table 1.

Comparison of photocatalytic membrane materials.

Table 1.

Comparison of photocatalytic membrane materials.

| Photocatalytic Membrane |

Preparation Method |

Degradation Target |

Cost |

Recyclability |

Visible Light Responsiveness |

| PM-PIL Membrane |

Independent |

Methyl Blue |

Low |

Easy |

Yes |

|

Al2O3/TiO2 [25] |

Coating |

Carbamazepine |

High |

Difficult |

No |

|

Ceramic/TiO2 [26] |

Coating |

Acid Red 4 |

High |

Difficult |

No |

|

PVDF/TiO2 [27] |

Mixing |

Wastewater |

High |

Difficult |

No |

|

PU/ZnO [28] |

Membrane Immersion |

Methyl Blue |

High |

Difficult |

No |

Carbon Nanotube/

ZnO-TiO2 [29] |

Membrane Immersion |

Methyl Blue |

High |

Difficult |

No |

|

PVDF/ZnO-TiO2 [30] |

Membrane Immersion |

Methyl Blue |

High |

Difficult |

No |

|

PSF/Cu2O [31] |

Chemical Vapor Deposition on Membrane |

IBP |

High |

Easy |

Yes |

|

GO/Fe2O3-TiO2 [32] |

Hydrothermal Synthesis, Membrane Immersion |

Humic Acid |

High |

Difficult |

No |

|

PVDF/ZnIn2S4 [33] |

Membrane Immersion |

Water |

High |

Easy |

Yes |

|

RGO/Bi2WO6 [34] |

Membrane Immersion |

Ciprofloxacin (CIP) |

High |

Difficult |

Yes |

|

RGO/PDA/Bi12O17Cl2 [35] |

Membrane Immersion |

Methyl Blue |

High |

Easy |

Yes |

|

Steel/CeO2 [36] |

Membrane Immersion |

Methyl Blue |

High |

Difficult |

No |

|

Ceramic/TiO2 [37] |

Membrane Immersion |

Humic Acid |

High |

Difficult |

No |

|

PVDF/TiO2 [38] |

Electrospinning and Hydrothermal Reaction |

CO2 |

High |

Easy |

No |

|

PES/TiO2 [39] |

Physical Deposition |

Acid Red 1 |

High |

Difficult |

No |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).