1. Introduction

Medical coding converts clinical diagnoses and procedures into standardized codes. This function is critical for modern healthcare systems [

1,

2]. The International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10), serves as the global standard, supporting systematic documentation, insurance reimbursement, disease tracking, and quality assessment.

Manual ICD-10 coding, though, remains labor-intensive and error-prone. Clinical documentation keeps growing more complex. The challenge intensifies [

3]. The process directly affects hospital reimbursement and revenue management. For healthcare institutions, reliance on automated coding systems has become a financial necessity rather than a convenience. Professional coders need extensive domain knowledge and significant time to extract diagnostic information from discharge summaries, which often contain thousands of words of specialized terminology.

Research on automated ICD coding over the past decade has leaned heavily on natural language processing and machine learning [

4]. Systems built on pretrained language models [

5,

6,

7,

8]—notably the Pre-trained Language Model for ICD coding (PLM-ICD) [

9]—extract patterns directly from large clinical corpora, with the resulting recommendations handed to coders as decision aids. In routine practice, these recommendations still flow through human-in-the-loop pipelines [

10] in which expert coders confirm correctness and supplement any omitted diagnoses.

Even the strongest deep learning pipelines inherit structural constraints: a fixed number of predictions is emitted, little insight into why a code was suggested is provided, and infrequent diagnoses are rarely surfaced. Those shortcomings motivate a search for new automation blueprints.

The rapid growth of large language models (LLMs) [

11,

12,

13] introduces a different path. LLMs can parse long-form narratives and evaluate clinical text coherence; however, uncertainty persists regarding whether specialized models should be replaced outright or integrated into cooperative workflows. The central question becomes:

What is the right role for agentic Artificial Intelligence (AI) in ICD automation—fully autonomous generation, or a cooperative design that blends LLM verification with established classifiers?

Research Focus: This work compares three agentic automation strategies for ICD-10 prediction and analyzes how each one influences accuracy and implementability in coder workflows.

The following designs are evaluated:

Deep Learning Automation: Specialized PLM-ICD models generate 15-code lists directly from discharge summaries, mirroring conventional fixed-output automation.

Direct LLM Automation: Standalone LLMs attempt to write complete ICD code sets from raw text, selecting both the codes and the number of predictions without outside assistance.

Agentic Filtering Automation: A filtering-centric workflow in which candidate codes are proposed by a deep learning model and then validated or discarded by an LLM agent, shifting LLM effort toward quality assurance rather than generation.

Figure 1 depicts this division of labor: candidates are drafted at scale by PLM-ICD, and unsupported items are removed by an LLM reviewer through clinical text verification. By assigning pattern recall to the baseline and filtering to the LLM, the pipeline yields concise, higher-confidence suggestions without incurring the expense of end-to-end LLM generation.

All approaches are benchmarked on 19,801 Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV) discharge summaries with four LLM checkpoints spanning compact to large scales (Qwen2.5-3B-Instruct, Llama-3.2-3B-Instruct, Phi-4-mini-instruct, and Sonnet-4.5). Results are stratified by document length to identify which workflow should be implemented in different clinical scenarios.

Key contributions include:

Head-to-head evaluation of three automation paradigms: The comparative behavior of conventional deep learning, direct LLM generation, and agentic filtering is quantified on a shared dataset with consistent metrics.

Guidelines for document-length-aware implementation: Performance is mapped across short, medium, and long discharge summaries, providing operational guidance on when each approach is preferable.

Evidence for filtering-centric agentic design: The study demonstrates that decomposing tasks and assigning LLMs to verification delivers the largest quality gains while preserving interpretability.

2. Related Work

Automated ICD coding has evolved through multiple technological waves. Each wave addressed limitations of earlier methods—while introducing new challenges of its own. This section reviews the relevant literature across three major approaches: traditional machine learning, deep learning, and recent large language models.

2.1. Traditional Machine Learning Approaches

Early automated ICD coding systems relied on rule-based methods and traditional machine learning [

14,

15]. These systems used pipelines that engineered features from clinical text using bag-of-words representations, term frequency–inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) weighting, and pseudo-relevance feedback [

16] from information retrieval [

17]. Common classifiers included Support Vector Machines, logistic regression, and decision trees applied to multi-label formulations. Some enhanced these with word2vec embeddings [

18].

Clear advantages were possessed by these traditional approaches. Easy to understand. Computationally efficient. However, serious limitations were also present. Complex meaning relationships in clinical narratives were struggled to be captured. Extensive domain-specific feature engineering was required. The explosion of ICD-10 code space—exceeding 70,000 codes—further challenged the ability to scale and generalize.

2.2. Deep Learning for ICD Coding

Everything was changed by deep learning through enabling end-to-end learning from raw clinical text—no manual feature engineering required [

19]. Improved performance was shown by convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [

15] and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) [

20]. Hierarchical text representations were learned automatically. Joint attention mechanisms over labels and document structure were introduced by early neural architectures tailored for ICD coding [

21].

Attention mechanisms [

22] proved particularly valuable. CAML [

23] and LAAT [

24] could identify which text segments mattered for specific diagnostic codes. This improved interpretability significantly. Hierarchical transformer variants pushed interpretability further [

25].

Meanwhile, other approaches focused on performance gains. MultiResCNN [

26] used multi-filter residual architectures. DILM-ICD [

27] employed iterative refinement with curriculum-style optimization. Both advanced the state of the art through different architectural innovations.

Then came pretrained language models [

5,

6]. BERT-based architectures [

7,

8] adapted for extreme multi-label classification [

28] achieved state-of-the-art results through transfer learning. PLM-ICD [

9] achieved strong performance, reaching approximately 55

Despite these advances, deep learning models face persistent challenges:

Limited interpretability: Neural architectures work as black boxes, providing minimal insight into coding reasoning.

Fixed prediction number: A predetermined list length (e.g., the top 15 codes) is still emitted by most models, even when the case clearly calls for more or fewer predictions.

Difficulty with rare codes: Models struggle with long-tail distribution of infrequent diagnostic codes [

29].

Lack of uncertainty measurement: Predictions lack calibrated confidence estimates for clinical decision support.

2.3. Large Language Models in Healthcare

Remarkable abilities are shown by recent large language models—GPT-4 [

12], Llama [

30], Phi [

31], and Claude [

32]. Excellence is demonstrated at clinical text understanding, medical reasoning, and knowledge synthesis. Where have these models been applied by researchers? Across various healthcare domains. Clinical question answering. Medical dialogue generation. Clinical note summarization. Differential diagnosis assistance [

33]. The applications keep expanding.

For medical coding specifically, reasonable ICD codes from discharge summaries can be generated by LLMs according to early investigations. Interpretation of complex clinical narratives is enabled by the natural language understanding inherent to LLMs. Diagnostic relationships can be reasoned about and coding decisions can be explained.

But careful evaluation for production medical coding remains limited. Key questions persist:

Precision and reliability: Do LLMs achieve precision comparable to specialized models trained on large-scale clinical coding datasets?

Consistency and determinism: Do LLM outputs remain stable across identical inputs—critical for clinical implementation?

Optimal integration strategies: Should LLMs replace or complement existing specialized models?

2.4. Prompt Engineering for Medical Validation

Hierarchical multi-agent frameworks modeled after hospital workflows have recently improved clinical AI safety by routing tasks toward specialized agents and yielding up to 8.2% performance gains compared with single-agent pipelines [

34]. Such architectures only succeed when prompts provide unambiguous contracts between collaborating agents. In medical coding scenarios, upstream retrieval agents must feed structured evidence, while downstream validation agents must explain accept/reject decisions in a standardized format.

Consequently, prompt engineering has become central to ICD validation. Prior studies targeting medical professionals have shown that carefully scoped prompts can substantially improve the accuracy and reliability of clinical NLP systems [

35,

36,

37]. In this work, validation prompts are deliberately designed to:

Clearly define the validation task and decision rules.

Supply the necessary clinical snippets and ICD-10 descriptions so evidence remains localized.

Request structured outputs (for example, Accept/Reject plus justification) so downstream parsers can automate follow-up actions.

Provide few-shot exemplars that demonstrate correct validation logic.

Constrain formatting for consistent, machine-checkable responses.

Recent reviews catalog zero-shot, few-shot, and chain-of-thought prompting paradigms that can be adapted to these requirements [

38,

39].

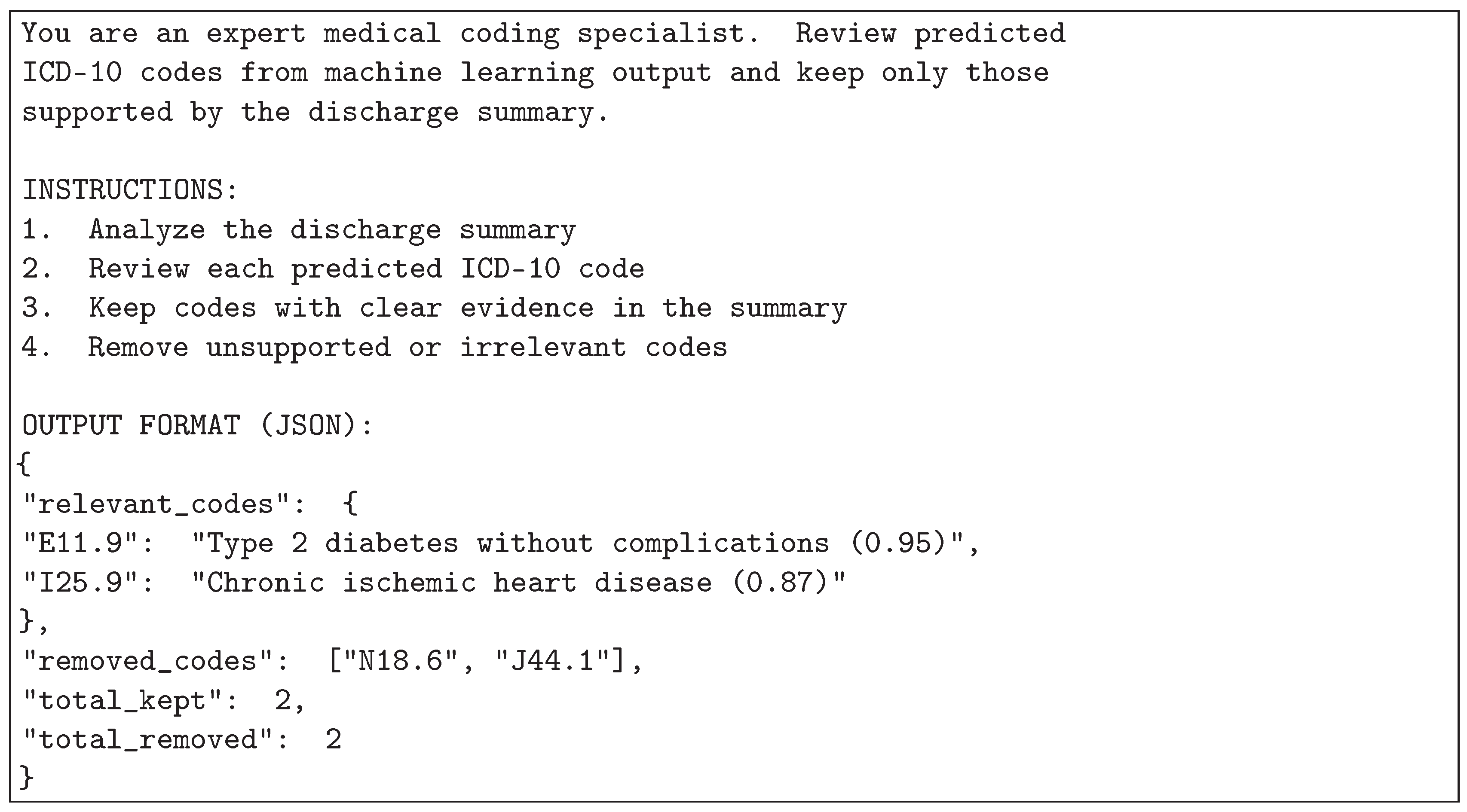

Figure 2 illustrates the standardized template employed so that autonomous validation agents generate machine-readable rationales aligned with clinical quality checks.

2.5. Research Gap and Contribution

Existing literature reveals that moderate accuracy for automated ICD coding is achieved by specialized deep learning models, though interpretability is lacked. Strong medical reasoning is demonstrated by LLMs; however, careful evaluation for coding tasks has not been performed.

A fundamental question remains unanswered: should specialized models be replaced outright by LLMs or deployed in complementary roles? Under what circumstances does each method work best? How can agentic AI be effectively utilized to automate medical coding workflows? These questions matter for clinical implementation and remain insufficiently explored in current literature.

3. Materials & Methods

This study investigates three distinct approaches for utilizing agentic AI to automate ICD-10 code prediction. Each approach represents a different automation strategy with distinct characteristics in terms of prediction generation, output determination, and quality control mechanisms.

3.1. Deep Learning Automation

PLM-ICD [

9] was selected to represent conventional deep learning automation for several reasons. First, Specialized deep learning model designed specifically to automate ICD coding tasks. Second, it demonstrates strong performance on the MIMIC-IV dataset. Third, modern pretrained language models are used, making it a representative baseline for evaluating how agentic AI-based automation approaches compare against established deep learning automation methods.

PLM-ICD is a deep learning model based on pretrained language models. PLM-ICD is built on RoBERTa [

6], a pretrained language model that employs Byte Pair Encoding [

40] to reduce vocabulary size by merging frequently occurring subword units during training. The model is specifically designed for multi-label ICD code prediction from clinical text [

28]. The dataset was partitioned 74%/11%/15% for training, validation, and testing, respectively, using iterative stratification to preserve the ICD label distribution across splits. Each discharge summary was then tokenized and mapped into contextual embeddings so that the network consumed structured input while retaining clinical semantics. Optimization of the multi-label objective minimized the summed binary cross-entropy over all code positions.

where

N is the number of samples,

C is the number of classes (ICD-10 codes),

is the true binary label for sample

i and class

j, and

is the predicted probability for sample

i and class

j.

To improve model results and avoid overfitting, Mean Average Precision (mAP) was used as the Early Stopping criterion. mAP is critical in multi-label tasks as both precision and recall across multiple thresholds are checked. During training, validation mAP@k was monitored, with training being stopped if no progress was observed for several epochs. This approach provided more stable training, better generalization, and stronger performance in multi-label ICD-10 coding.

This deep learning automation approach processes discharge summaries and automatically generates a fixed set of 15 ICD code predictions. All 15 automated predictions are retained and evaluated using Precision@15 (P@15), representing a comprehensive coverage automation strategy.

3.2. Direct LLM Automation

This approach utilizes large language models to directly automate the entire coding process. LLMs receive discharge summaries as input and autonomously generate ICD codes without external guidance or candidate sets. The automation is fully autonomous—output size is decided dynamically by the model based on its assessment. Performance is evaluated using Precision (P), reflecting the variable-output nature of this automation strategy.

3.3. Agentic Filtering Automation

This novel approach utilizes agentic AI to automate ICD coding through intelligent integration of deep learning and LLM capabilities. The automation operates in two stages: First, the PLM-ICD model automatically generates 15 candidate predictions. Second, an LLM agent automatically evaluates and filters these candidates, checking each code’s clinical relevance, semantic coherence, and confidence level. Low-confidence predictions are automatically filtered out. The final automated output contains a variable number of high-confidence codes selected from the original 15 candidates, evaluated using Precision (P).

Unlike direct LLM automation, this agentic approach automates coding through strategic task decomposition—utilizing deep learning for automated candidate generation and LLM-based agentic intelligence for automated verification and selection.

Figure 3 illustrates the architectural differences between all three automation approaches.

Figure 3 demonstrates the distinct automation architectures employed by each approach. Deep learning automation produces fixed 15-code output through direct automated prediction. Direct LLM automation autonomously generates variable output sizes. Agentic filtering automation utilizes agentic AI to integrate automated candidate generation with LLM-based automated quality assessment

3.4. Hardware Configuration

All experiments were executed on a workstation equipped with NVIDIA RTX 4090 graphics processing units (GPUs). The 24 GB of GPU memory provided for PLM-ICD fine-tuning, batched inference, and the multiple passes required for the agentic filtering setup. Keeping every run on the same hardware ensured consistent computational conditions across approaches.

3.5. Language Models Evaluated

Four different large language models with different abilities and computational requirements were tested. Qwen2.5-3B-Instruct [

41] is a compact open-source model optimized for instruction following. Llama-3.2-3B-Instruct [

30] represents Meta’s lightweight instruction-tuned model. Phi-4-mini-instruct [

31] is Microsoft’s efficient small-scale language model. Finally, Sonnet-4.5 [

32] is an advanced large-scale model with extensive language understanding capabilities. Note that the selected LLMs show substantial design diversity [

30,

31,

32,

41], making it difficult to isolate performance differences between fundamental methodological approaches and model-specific implementation factors.

3.6. Evaluation Metrics and Research Scope

This study specifically focuses on precision-oriented evaluation of ICD code predictions. The research question centers on whether the reliability and accuracy of predicted codes can be improved by LLM-based agentic filtering, rather than maximizing code coverage or completeness.

The agentic filtering stage functions strictly as a quality gate: the baseline’s 15 candidates are re-examined and only those with clear textual support are retained, rather than attempting full code generation. This structure matches day-to-day coder workflows, where short, dependable suggestion lists are far more useful than sprawling sets that require heavy triage. In human-in-the-loop settings, precision directly determines whether teams will trust the system—false positives waste coder time and create audit exposure, whereas missing codes are typically added during routine review.

Evaluation Metrics:

Two complementary precision metrics were used to suit the different output characteristics of each approach:

Precision@15 (P@15): Applied to the baseline approach which produces exactly 15 predictions. It measures the proportion of correct codes among the 15 outputs:

Precision (P): Applied to approaches with variable output sizes (LLM-only and agentic). It measures the proportion of correct predictions:

Metric rationale: Precision-focused analysis provides more sensitivity than accuracy or Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) based reporting when dealing with extreme class imbalance, complementing prior findings on precision-recall behavior in imbalanced settings [

42].

This study does not aim to develop a comprehensive automated coding system that captures all possible ICD codes for a discharge summary. This study investigates LLM-based filtering can improve prediction reliability by reducing false positives while maintaining competitive accuracy on correctly identified codes. Recall and coverage metrics are important for fully automated coding systems that operate without human oversight; however, they are outside the scope of this study, which focuses on improving precision within coder-assistance workflows. In such human-in-the-loop settings, omitted codes are typically identified and added during routine coding review.. In future work, recall and F1-score should also be reported in accordance with established clinical prediction model reporting guidelines [

43] to improve both reproducibility and transparency.

Key methodological differences:

Baseline: Fixed output of 15 codes (evaluated with P@15)

LLM-only: Variable output size decided autonomously by the model (evaluated with P)

Agentic: Selects variable number of codes from baseline’s 15 candidates through LLM-based filtering (evaluated with P)

Note that these methodological differences reflect each approach’s natural working characteristics. The baseline approach uses P@15 with fixed 15-code output, while LLM-only and agentic approaches use standard precision with variable output sizes. This makes direct numerical comparisons challenging but represents how each automation strategy operates in practice.

4. Results

4.1. Dataset and Experimental Setup

The collection of patient data and database construction were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Patient consent was waived as the dataset is fully de-identified and contains no personal information.The MIMIC-IV Note dataset [

44,

45] has a large collection of de-identified free-text clinical records, including admission and discharge notes, radiology reports, and other clinical narratives describing patient history, treatments, follow-ups, and clinical course. Note that MIMIC-IV may contain imbalances in disease distribution, case complexity, and clinical documentation patterns, which could limit generalizability across diverse healthcare settings and patient populations.

4.2. Evaluation Dataset

All three approaches were evaluated on the same test set of 19,801 discharge summaries from MIMIC-IV [

45] to ensure fair comparison across methodologies.

4.3. Overall Performance Comparison

Table 1 provides detailed performance metrics for all model configurations tested in this study.

4.3.1. Key Performance Observations

Table 1 surfaces three patterns that mirror the intent behind each methodology. The baseline P@15 system always emits fifteen codes, leaning into breadth so downstream reviewers see a wide pool of candidates. Agentic pipelines, by contrast, return only two to eight codes on average because they filter aggressively for confidence. In practice that means blanket coverage is traded for higher-quality, better justified suggestions.

Baseline deep learning therefore serves as a coverage-oriented reference point. PLM-ICD achieved a P@15 of 55.8

LLM-only generation showed complete failure across all model scales.Compact models demonstrated near-zero performance (Llama-3.2-3B: 1.5 percent, Qwen2.5-3B: 4.9 percent, Phi-4-mini-instruct: 12.4 percent). Even Sonnet-4.5 managed only 34.6 percent precision, demonstrating that increased model scale does not guarantee adequate performance for specialized medical coding tasks.

Agentic filtering transformed failing LLMs into competitive precision-focused systems by leveraging the models as verification mechanisms rather than code generators. Llama-3.2-3B improved from 1.5 percent to 55.1 percent precision (36.7× improvement), Qwen2.5-3B from 4.9 percent to 37.0 percent (7.6×), Phi-4-mini-instruct from 12.4 percent to 45.5 percent (3.7×), and Sonnet-4.5 from 34.6 percent to 52.6 percent (1.5×). The improvements were achieved through selective output (2.0 to 7.9 codes) that prioritized suggestion reliability over exhaustive coverage.

4.3.2. Document-Length Sensitivity

Document length emerged as a critical factor influencing relative approach performance (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). This sensitivity mirrors broader observations that transformer-based models struggle with very long contexts despite architectural adaptations [

46]. Three different performance zones were identified:

Figure 5 provides a detailed breakdown of performance across document length zones. Compact LLMs show dramatic improvement with agentic filtering: Llama-3.2-3B improves from 0.8-1.6 percent standalone to 26.9-64.6 percent agentic across zones. The visualization demonstrates how agentic filtering transforms failing standalone LLMs into competitive medical coding systems by leveraging baseline candidates for verification rather than generating codes from scratch.Zone 1: Short Documents (0 to 3K characters). Agentic filtering achieved the best performance with 50 to 60 percent precision for well-configured systems. In contrast, LLM-only generation showed severe degradation (1.5 to 12.4 percent for compact models; 34.6 percent for Sonnet-4.5), while baseline achieved 18 to 25 percent precision.

Zone 2: Medium-length documents (3–15K characters). In this range, baseline deep learning and agentic approaches showed similar levels of performance, achieving precision between 50

Zone 3: Long Documents (15K+ characters). Baseline deep learning outperformed all alternatives (56 to 58 percent precision), including Sonnet-4.5 in both standalone and agentic configurations.Agentic filtering ranged from 38 to 60 percent precision, while LLM-only generation remained at 1 to 38 percent.

5. Discussions

5.1. Interpretation of Findings

Why does agentic filtering automation succeed where direct LLM automation fails? The automation architecture explains this transformation. Automating code generation from scratch requires both comprehensive medical knowledge and precise code-to-diagnosis mapping—a challenging automation task for general-purpose LLMs. Automating verification and filtering, in contrast, requires evaluating candidate plausibility against clinical text. This automation task aligns well with LLMs’ natural language understanding capabilities, enabling effective utilization of agentic AI for quality control.

Interestingly, model size correlates poorly with direct automation performance. This suggests that automating specialized domain tasks needs more than computational scale. Training methodology, instruction-following capability, and domain-specific fine-tuning may matter more than parameter count for autonomous code generation. The agentic automation approach sidesteps these limitations entirely by reframing the automation architecture from end-to-end generation to task-decomposed verification, effectively utilizing agentic AI for what it does best.

The inter-model variability observed in LLM-only performance reinforces this point. Performance showed extreme variance—from 1.5 percent (Llama-3.2-3B) to 34.6 percent (Sonnet-4.5), representing a 23× differential. This substantial variation highlights that task-appropriate model selection matters critically for specialized medical coding applications.

Document length emerged as a critical design parameter. The three-zone performance pattern described in the Results section shows that optimal system configuration depends fundamentally on input characteristics. Short documents lack sufficient context for pattern-based deep learning but provide adequate information for LLM-guided filtering. Long documents, meanwhile, contain rich patterns that specialized models exploit effectively—patterns that potentially overwhelm LLM context processing capabilities. This challenges one-size-fits-all implementation strategies. A better approach? Document-length-adaptive system architectures.

The consistent behavior of small models (Llama-3.2-3B, Qwen2.5-3B) in agentic configuration addresses clinical concerns about reproducibility while maintaining computational efficiency, making precision-focused ICD-10 coding assistance accessible even to resource-constrained healthcare settings.

5.2. Implications for Automating Clinical Workflows Using Agentic AI

Based on the findings, a document-length-adaptive automation strategy is proposed, optimizing which automation approach to utilize according to input characteristics as detailed in the three-zone performance analysis.

One clear recommendation: avoid direct LLM automation entirely for production medical coding. The consistently inadequate precision across all document lengths and model scales makes autonomous LLM generation unsuitable for clinical use.

The agentic filtering automation approach addresses a real clinical challenge. Manual ICD-10 coding consumes significant time and directly impacts hospital reimbursement and revenue cycle management. By utilizing agentic AI to achieve competitive accuracy with compact models, this automation approach enables resource-constrained healthcare settings to implement effective automated coding assistance.

5.3. Comparison with Related Work

This study extends prior medical coding automation research by systematically investigating three distinct automation approaches: deep learning automation, direct LLM automation, and agentic filtering automation utilizing agentic AI. Previous work showed moderate success with deep learning automation (PLM-ICD) and explored LLM applications in healthcare. The findings add something new—clear guidance on how to effectively utilize agentic AI for automation. The agentic filtering automation approach represents a novel contribution, demonstrating that effective automation is achieved by utilizing agentic AI to strategically integrate specialized models with LLM verification, rather than relying on autonomous LLM generation.

How does this compare to traditional ensemble methods? Traditional ensembles typically improve the baseline by 0.1-0.5 percent through model aggregation and voting. The agentic approach achieves much larger gains for specific configurations—up to 36.7 times for Llama-3.2-3B. Keep in mind, though, that improvements vary significantly across models and document lengths. Another advantage: unlike ensembles requiring multiple trained models, the approach uses a single baseline model with LLM-based filtering.

5.4. Precision-Oriented Design Rationale

This study explicitly focuses on precision-enhancing agentic filtering for human-in-the-loop workflows rather than comprehensive autonomous coding. In real-world implementation, professional coders review AI-generated suggestions, verify accuracy, and add missing codes based on clinical judgment. Within this workflow, precision is prioritized because incorrect suggestions waste coder time and create audit liability; broader coverage metrics such as recall are acknowledged conceptually but were not measured in this evaluation.

The empirical results demonstrate this design choice quantitatively. Baseline PLM-ICD provides 15 code suggestions at 55.8 percent precision, while agentic Llama provides 4 selective suggestions at 55.1 percent precision. The key advantage? A 73 percent reduction in false positives—from 6.6 to 1.8 incorrect suggestions per case. This precision-oriented design aligns with established practices in clinical decision support systems [

47], where high specificity prevents alert fatigue [

48] and maintains clinician trust.

6. Conclusions

This study addresses a practical question for clinical automation: how can agentic AI be deployed to deliver reliable ICD-10 coding [

1,

2]? Three automation strategies were compared—deep learning pipelines [

9], direct LLM generation [

49], and an agentic filtering workflow. The evidence points to the latter: the most effective systems pair specialized predictors with LLM-based validation, producing sizeable gains even when the base models remain compact.

These findings reach beyond ICD coding. They outline a general blueprint for automating clinical workflows with agentic AI. Task decomposition that couples domain-specific candidate generators with agentic verification can outperform monolithic, end-to-end LLM automation across other clinical NLP settings as well.

The agentic filtering automation approach also provides pathways for more interpretable automated systems. LLMs can be prompted to output textual justifications for acceptance or rejection of specific automated predictions, which could enhance clinical interpretability and trust in AI-driven automation, though evaluating the quality and accuracy of such explanations remains future work.

Future work could build on these findings in several ways. Incorporating document-length–aware routing may enable automatic selection of the most appropriate approach for each case. In addition, adaptive confidence thresholding might better balance precision-recall trade-offs. Evaluation frameworks should expand beyond precision to incorporate recall and F1-score metrics. Finally, explainability mechanisms that prompt LLMs to generate textual justifications could enhance clinical trust, though rigorous evaluation of such explanations’ accuracy and clinical validity would be essential.

What’s the bottom line? The future of automating clinical coding doesn’t lie in end-to-end LLM automation. Instead, strategic utilization of agentic AI through task decomposition works better. Deep learning automation generates accurate candidates. Agentic AI provides intelligent automated verification and filtering. This complementary automation architecture creates coding systems that are more accurate and interpretable—exactly what real-world healthcare implementation demands.

Clinical AI automation will keep evolving, but one principle should stay constant: match each automation approach to what it does best, then orchestrate them through agentic AI. The aim is not to supplant clinicians; it is to build supportive systems whose agentic verification complements human expertise and keeps workflows grounded in real-world practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.A., L.N., K.W., N.H., C.T., and P.M.; methodology, K.A., L.N., and P.M.; software, K.A.; validation, K.A., L.N., and P.M.; formal analysis, K.A.; investigation, K.A.; resources, N.H. and P.M.; data curation, K.A.; writing—original draft preparation, K.A.; writing—review and editing, K.A., L.N., K.W., N.H., C.T., and P.M.; visualization, K.A.; supervision, P.M.; project administration, P.M.; funding acquisition, P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Reinventing University Funding (2024) from the Office of the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation, and Mahidol University under the initiative: Developing a Frontier Research Network in Digital and Artificial Intelligence for Thailand.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the MIMIC-IV database (

https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/). Access to MIMIC-IV requires completion of a training course and signing a Data Use Agreement. Researchers can request access through PhysioNet. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data due to privacy and ethical considerations. The experimental code and model configurations used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mahidol University for the support and resources that helped this study. The authors are also very thankful to their advisors for their helpful guidance and knowledge.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ICD |

International Classification of Diseases |

| ICD-10 |

International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision |

| LLM |

Large Language Model |

| PLM |

Pretrained Language Model |

| PLM-ICD |

Pretrained Language Model for ICD |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| NLP |

Natural Language Processing |

| MIMIC-IV |

Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| DUA |

Data Use Agreement |

| CITI |

Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative |

| IRB |

Institutional Review Board |

| TF-IDF |

Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency |

| BPE |

Byte Pair Encoding |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| RNN |

Recurrent Neural Network |

| GPU |

Graphics Processing Unit |

| mAP |

Mean Average Precision |

| ROC |

Receiver Operating Characteristic |

References

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10), 5 ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare; Medicaid Services; National Center for Health Statistics. ICD-10-CM Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting FY 2024

. In Available from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the National Center for Health Statistics; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, T.; Shepheard, J.; Sundararajan, V. Quality of Diagnosis and Procedure Coding in ICD-10 Administrative Data. Medical Care 2006, 44, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edin, J.; Junge, A.; Havtorn, J.D.; Borgholt, L.; Maistro, M.; Ruotsalo, T.; Maaløe, L. Automated Medical Coding on MIMIC-III and MIMIC-IV: A Critical Review and Replicability Study. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 46th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, ACM, Taipei, Taiwan, 2023; pp. 2572–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. RoBERTa: A Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.11692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Yoon, W.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; So, C.H.; Kang, J. BioBERT: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 2019, 36, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsentzer, E.; Murphy, J.; Boag, W.; Weng, W.H.; Jindi, D.; Naumann, T.; McDermott, M. Publicly Available Clinical BERT Embeddings. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2nd Clinical Natural Language Processing Workshop, 2019; Association for Computational Linguistics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.W.; Tsai, S.C.; Chen, Y.N. PLM-ICD: Automatic ICD Coding with Pretrained Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 4th Clinical Natural Language Processing Workshop, Association for Computational Linguistics, Seattle, WA, 2022; pp. 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosqueira-Rey, E.; Hernandez-Pereira, E.; Alonso-Rios, D.; Bobes-Bascaran, J.; Fernandez-Leal, A. Human-in-the-loop machine learning: a state of the art. Artificial Intelligence Review 2022, 56, 3005–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Peng, Y.; Cohen, T.; Ghassemi, M.; Weng, C.; Tian, S. Large language models in biomedicine and health: current research landscape and future directions. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2024, 31, 1801–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nori, H.; King, N.; McKinney, S.M.; Carignan, D.; Horvitz, E. Capabilities of GPT-4 on Medical Challenge Problems. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.13375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, K.; Azizi, S.; Tu, T.; Mahdavi, S.S.; Wei, J.; Chung, H.W.; Scales, N.; Tanwani, A.; Cole-Lewis, H.; Pfohl, S.; et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature 2023, 620, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perotte, A.; Pivovarov, R.; Natarajan, K.; Weiskopf, N.; Wood, F.; Elhadad, N. Diagnosis code assignment: models and evaluation metrics. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2014, 21, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masud, J.H.B.; Kuo, C.C.; Yeh, C.Y.; Yang, H.C.; Lin, M.C. Applying Deep Learning Model to Predict Diagnosis Code of Medical Records. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Mourad, A.; Zhuang, S.; Koopman, B.; Zuccon, G. Pseudo Relevance Feedback with Deep Language Models and Dense Retrievers: Successes and Pitfalls. arXiv 2022, arXiv:cs. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, C.D.; Raghavan, P.; Schütze, H. Introduction to Information Retrieval; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolov, T.; Chen, K.; Corrado, G.; Dean, J. Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1301.3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otter, D.W.; Medina, J.R.; Kalita, J.K. A Survey of the Usages of Deep Learning for Natural Language Processing. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2021, 32, 604–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammani, A.; Bagheri, A.; van der Heijden, P.G.M.; te Riele, A.S.J.M.; Baas, A.F.; Oosters, C.A.J.; Oberski, D.; Asselbergs, F.W. Automatic Multilabel Detection of ICD-10 Codes in Dutch Cardiology Discharge Letters Using Neural Networks. npj Digital Medicine 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Xing, E. A Neural Architecture for Automated ICD Coding. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2018, Volume 1, 1066–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All you Need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullenbach, J.; Wiegreffe, S.; Duke, J.; Sun, J.; Eisenstein, J. Explainable Prediction of Medical Codes from Clinical Text. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics 2018, Vol. 1, 1101–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.; Nguyen, D.Q.; Nguyen, A. A Label Attention Model for ICD Coding from Clinical Text. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2020; pp. 3335–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Perez-Concha, O.; Nguyen, A.; Bennett, V.; Jorm, L. Hierarchical label-wise attention transformer model for explainable ICD coding. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2022, 133, 104161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Yu, H. ICD Coding from Clinical Text Using Multi-Filter Residual Convolutional Neural Network. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2020, 34, 8180–8187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Niu, K.; Zeng, M.; Li, M. DILM-ICD: A Deep Iterative Learning Model for Automatic ICD Coding. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM). IEEE, 2023; pp. 1394–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yan, J.; Wang, X.; Zha, H. Deep Extreme Multi-label Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 ACM on International Conference on Multimedia Retrieval. ACM, 2018; pp. 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, A.; Kavuluru, R. Few-Shot and Zero-Shot Multi-Label Learning for Structured Label Spaces. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2018; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 3132–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; Martin, L.; Stone, K.; Albert, P.; Almahairi, A.; Babaei, Y.; Bashlykov, N.; Batra, S.; Bhargava, P.; Bhosale, S.; et al. Llama 2: Open Foundation and Fine-Tuned Chat Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.09288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdin, M.; Aneja, J.; Behl, H.; Bubeck, S.; Eldan, R.; Gunasekar, S.; Harrison, M.; Hewett, R.J.; Javaheripi, M.; Kauffmann, P.; et al. Phi-4 Technical Report. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.08905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Kadavath, S.; Kundu, S.; Askell, A.; Kernion, J.; Jones, A.; Chen, A.; Goldie, A.; Mirhoseini, A.; McKinnon, C.; et al. Constitutional AI: Harmlessness from AI Feedback. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.08073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Jiang, Y.; Zhi, H.; Dong, Y.; Li, H.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Dong, Q.; Shen, H.; Wang, Y. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: past, present and future. Stroke and Vascular Neurology 2017, 2, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Jeong, H.; Park, C.; Park, E.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Lee, H.; McDuff, D.; Ghassemi, M.; Breazeal, C.; et al. Tiered Agentic Oversight: A Hierarchical Multi-Agent System for Healthcare Safety. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.12482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, F.; Wang, C.; Liu, S. Prompt Engineering in Clinical Practice: Tutorial for Clinicians. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2025, 27, e72644–e72644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivarajkumar, S.; Kelley, M.; Samolyk-Mazzanti, A.; Visweswaran, S.; Wang, Y. An Empirical Evaluation of Prompting Strategies for Large Language Models in Zero-Shot Clinical Natural Language Processing: Algorithm Development and Validation Study. JMIR Medical Informatics 2024, 12, e55318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, X.; Deng, X.; Wen, H.; You, M.; Liu, W.; Li, Q.; Li, J. Prompt engineering in consistency and reliability with the evidence-based guideline for LLMs. npj Digital Medicine 2024, 7, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaghir, J.; Naguib, M.; Bjelogrlic, M.; Névéol, A.; Tannier, X.; Lovis, C. Prompt Engineering Paradigms for Medical Applications: Scoping Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2024, 26, e60501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaghir, J.; Naguib, M.; Bjelogrlic, M.; Névéol, A.; Tannier, X.; Lovis, C. Prompt engineering paradigms for medical applications: scoping review and recommendations for better practices. arXiv;arXiv version of the paper published in 2024. 2024, arXiv:2405.01249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouhar, V.; Meister, C.; Gastaldi, J.L.; Du, L.; Vieira, T.; Sachan, M.; Cotterell, R. A Formal Perspective on Byte-Pair Encoding. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.16837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Bai, S.; Chu, Y.; Cui, Z.; Dang, K.; Deng, X.; Fan, Y.; Ge, W.; Han, Y.; Huang, F.; et al. Qwen Technical Report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.16609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.; Goadrich, M. The Relationship Between Precision-Recall and ROC Curves. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML ’06), 2006; ACM; pp. 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, G.S.; Moons, K.G.; Dhiman, P.; Riley, R.D.; Beam, A.L.; Van Calster, B.; Ghassemi, M.; Liu, X.; Reitsma, J.B.; van Smeden, M.; et al. TRIPOD+AI statement: updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ 2024, 385, e078378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.; Pollard, T.; Horng, S.; Celi, L.A.; Mark, R. MIMIC-IV-Note: Deidentified free-text clinical notes; PhysioNet, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.E.W.; Bulgarelli, L.; Shen, L.; Gayles, A.; Shammout, A.; Horng, S.; Pollard, T.J.; Hao, S.; Moody, B.; Gow, B.; et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Scientific Data 2023, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, H.; Wang, G.; Lu, Y.; Florencio, D.; Zhang, C. Understanding Long Documents with Different Position-Aware Attentions. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.08201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, I.; Gorman, P.; Greenes, R.A.; Haynes, R.B.; Kaplan, B.; Lehmann, H.; Tang, P.C. Clinical Decision Support Systems for the Practice of Evidence-based Medicine. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2001, 8, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmke, H.; Fiumefreddo, R.; Schuetz, P.; De Iaco, R.; Zaugg, C. Tackling alert fatigue with a semi-automated clinical decision support system: quantitative evaluation and end-user survey. Swiss Medical Weekly 2023, 153, 40082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soroush, A.; Glicksberg, B.S.; Zimlichman, E.; Barash, Y.; Freeman, R.; Charney, A.W.; Nadkarni, G.N.; Klang, E. Large Language Models Are Poor Medical Coders – Benchmarking of Medical Code Querying. NEJM AI 2024, 1, AIdbp2300040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).