1. Introduction

The emergence of Large Language Models (LLMs) has fundamentally transformed the landscape of artificial intelligence, enabling machines to understand, generate, and reason with natural language at unprecedented levels of sophistication [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Building upon these capabilities, a new paradigm has emerged: LLM-based agents that can autonomously perceive their environment, formulate plans, and execute actions to achieve complex goals. This evolution represents a significant departure from traditional language models that merely respond to queries, moving towards systems that actively interact with the world and accomplish tasks that previously required human intervention.

The concept of autonomous agents has long been a central pursuit in artificial intelligence research, with early work exploring rule-based systems, reinforcement learning agents, and planning algorithms [

7]. However, the integration of LLMs as the cognitive backbone of these agents has catalyzed remarkable advances in recent years. The introduction of ChatGPT in November 2022 [

8,

9,

10] and subsequent models such as GPT-4 [

3,

11,

12] demonstrated that large-scale language models possess emergent capabilities including few-shot learning, chain-of-thought reasoning, and instruction following that make them particularly well-suited for agent applications. These developments have sparked an explosion of research into LLM agents, with seminal works such as ReAct [

13], Toolformer [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20], and Generative Agents [

21,

22] establishing foundational paradigms for reasoning, tool use, and social simulation respectively.

The rapid proliferation of LLM agent research has created a pressing need for systematic organization and analysis of this burgeoning field. While several surveys have examined specific aspects of LLM agents [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28], the field continues to evolve at such a pace that comprehensive coverage remains challenging. Moreover, the diversity of approaches spanning reasoning enhancement, tool augmentation, multi-agent collaboration, and memory systems necessitates a unified framework for understanding the relationships between different methodologies and identifying opportunities for cross-pollination.

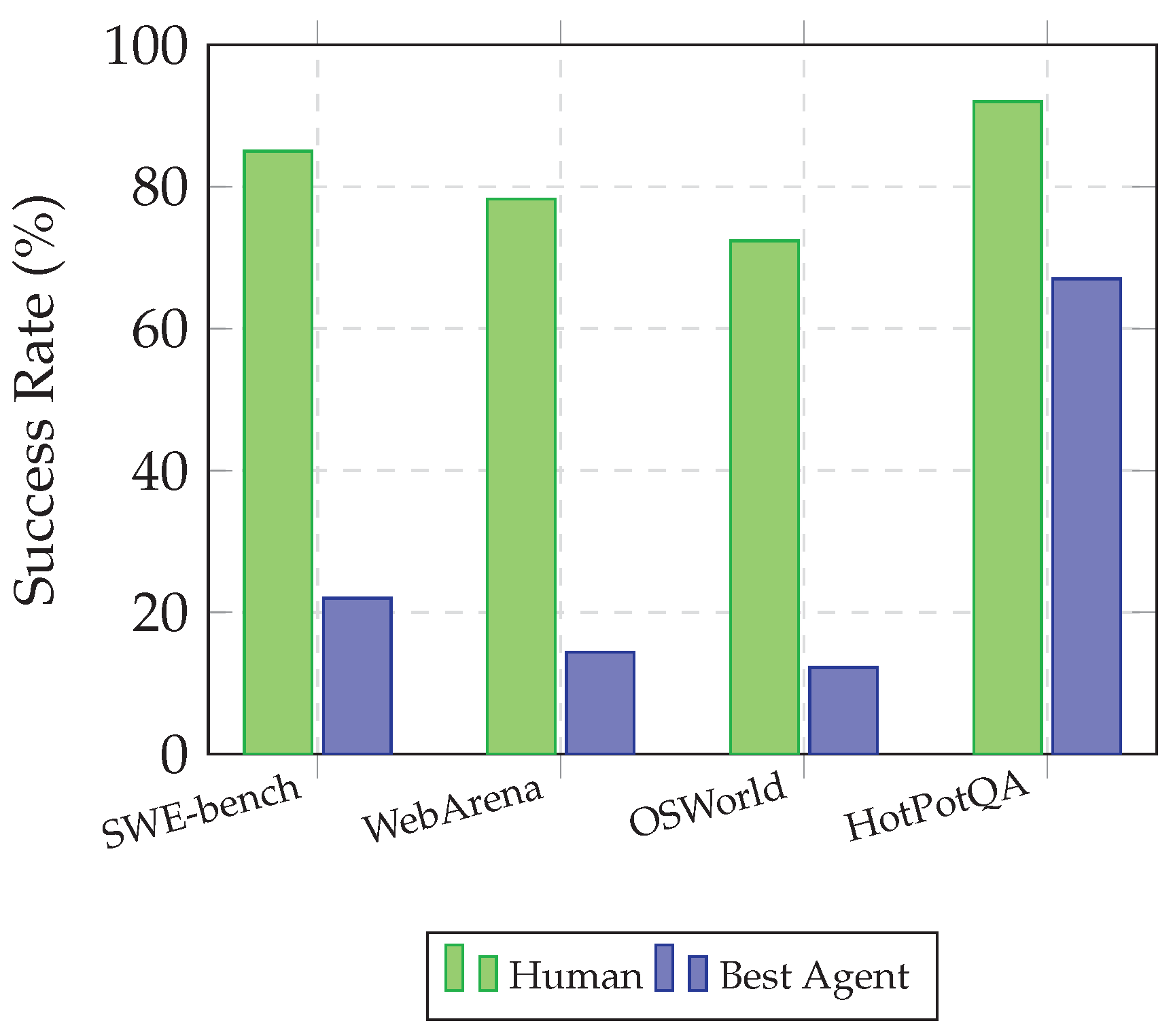

This survey aims to provide a comprehensive and structured overview of LLM-based agents that addresses these challenges. Our contributions can be summarized as follows. First, we establish a formal definition of LLM agents and present a novel taxonomy that organizes the field into four fundamental categories: reasoning-enhanced agents, tool-augmented agents, multi-agent systems, and memory-augmented agents. This taxonomy provides a principled framework for understanding the diverse landscape of agent architectures while highlighting the complementary nature of different approaches. Second, we conduct an in-depth analysis of representative methods within each category, examining their technical innovations, theoretical foundations, and empirical performance. Our analysis encompasses over 100 papers spanning the period from 2020 to 2024, with particular emphasis on developments since the introduction of instruction-tuned models. Third, we present a systematic comparison of agent capabilities across multiple benchmarks, including software engineering tasks (SWE-bench) [

29,

30], web automation (WebArena) [

31], and general agent evaluation (AgentBench) [

32,

33]. This empirical analysis reveals both the impressive progress achieved and the substantial gaps that remain between current systems and human-level performance. Fourth, we identify key challenges facing the field, including issues of hallucination, long-horizon planning, safety, and scalability, and articulate promising research directions for addressing these limitations.

The remainder of this survey is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides essential background on LLMs and establishes foundational concepts for understanding agent architectures.

Section 3 presents our proposed taxonomy and provides an overview of the agent landscape.

Section 4 through

Section 7 provide detailed analyses of reasoning-enhanced agents, tool-augmented agents, multi-agent systems, and memory-augmented agents respectively.

Section 8 examines key application domains including software engineering, scientific research, and embodied AI.

Section 9 presents benchmark comparisons and empirical analyses.

Section 10 discusses current challenges and limitations, while

Section 11 outlines future research directions. Finally,

Section 12 concludes the survey with key takeaways and reflections on the trajectory of the field.

2. Background and Preliminaries

This section establishes the foundational concepts necessary for understanding LLM-based agents. We begin by reviewing the evolution of large language models, then formally define what constitutes an LLM agent, and finally introduce key evaluation metrics and paradigms.

2.1. Evolution of Large Language Models

The development of modern LLMs can be traced through several transformative milestones. The introduction of the Transformer architecture by Vaswani et al. [

1,

34] in 2017 established the self-attention mechanism as the foundation for scalable sequence modeling. Unlike recurrent architectures, Transformers enable parallel processing of input sequences and capture long-range dependencies through attention weights, making them particularly suitable for language understanding tasks. The subsequent development of BERT [

2,

35,

36,

37] demonstrated that bidirectional pre-training on large text corpora could yield powerful representations transferable to diverse downstream tasks.

The scaling of language models to billions of parameters marked a critical phase transition in capabilities [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. GPT-3 with 175 billion parameters exhibited surprising emergent abilities including few-shot learning, where the model could adapt to new tasks from just a handful of examples provided in the prompt. This capability opened the door to in-context learning paradigms that would later prove essential for agent applications. The instruction-tuning revolution, exemplified by InstructGPT and ChatGPT [

8,

44,

45], further enhanced model capabilities by training on human feedback to follow diverse instructions more reliably. These instruction-tuned models demonstrated markedly improved abilities to engage in multi-turn dialogue, follow complex instructions, and maintain coherent behavior across extended interactions.

The release of GPT-4 [

3,

46,

47,

48,

49] in March 2023 represented another significant leap, achieving human-level performance on numerous professional examinations while exhibiting enhanced reasoning and reduced hallucination rates compared to predecessors. Concurrent developments in open-source models, particularly the Llama series [

50] and Code Llama [

51], have democratized access to powerful foundation models and spurred rapid innovation in the research community. The emergence of models specifically designed for safety through techniques like Constitutional AI [

52] has also addressed critical concerns about deploying LLMs in autonomous agent settings. Recent advances in generative modeling [

53,

54] and natural language processing have further expanded the capabilities available to agent systems.

2.2. Definition of LLM Agents

We define an LLM agent as a system that employs a large language model as its core reasoning engine to perceive its environment, make decisions, and execute actions in pursuit of specified goals. Formally, an LLM agent can be characterized by the tuple , where denotes the underlying language model, represents the environment with which the agent interacts, is the state space capturing relevant environmental and internal states, is the action space available to the agent, and is the policy function that maps states to actions.

The agent operates through an iterative perception-reasoning-action loop. At each timestep t, the agent receives an observation from the environment, which is combined with the agent’s memory and task specification g to form the current state . The LLM then processes this state, typically through prompting or fine-tuned inference, to produce a reasoning trace and select an action . The action is executed in the environment, producing a new observation and potentially updating the agent’s memory to . This cycle continues until a termination condition is satisfied or a maximum number of steps is reached.

Formally, the agent’s policy

can be expressed as a conditional probability distribution over actions given the current context:

where

denotes the probability distribution induced by the language model

, and

is a function that formats the inputs into a textual prompt. The agent’s trajectory

is generated by iteratively sampling actions and observing state transitions:

where

represents the environment dynamics. The objective is typically to maximize expected cumulative reward:

where

is the reward function and

is a discount factor.

This formulation distinguishes LLM agents from traditional LLM applications in several important ways. First, agents maintain persistent state across multiple interaction steps, enabling them to pursue multi-step goals rather than responding to isolated queries. Second, agents possess the ability to take actions that modify their environment, whether through tool invocation, code execution, or physical manipulation in embodied settings. Third, agents typically employ explicit reasoning mechanisms that make their decision-making process more interpretable and controllable than end-to-end neural approaches.

2.3. Core Agent Components

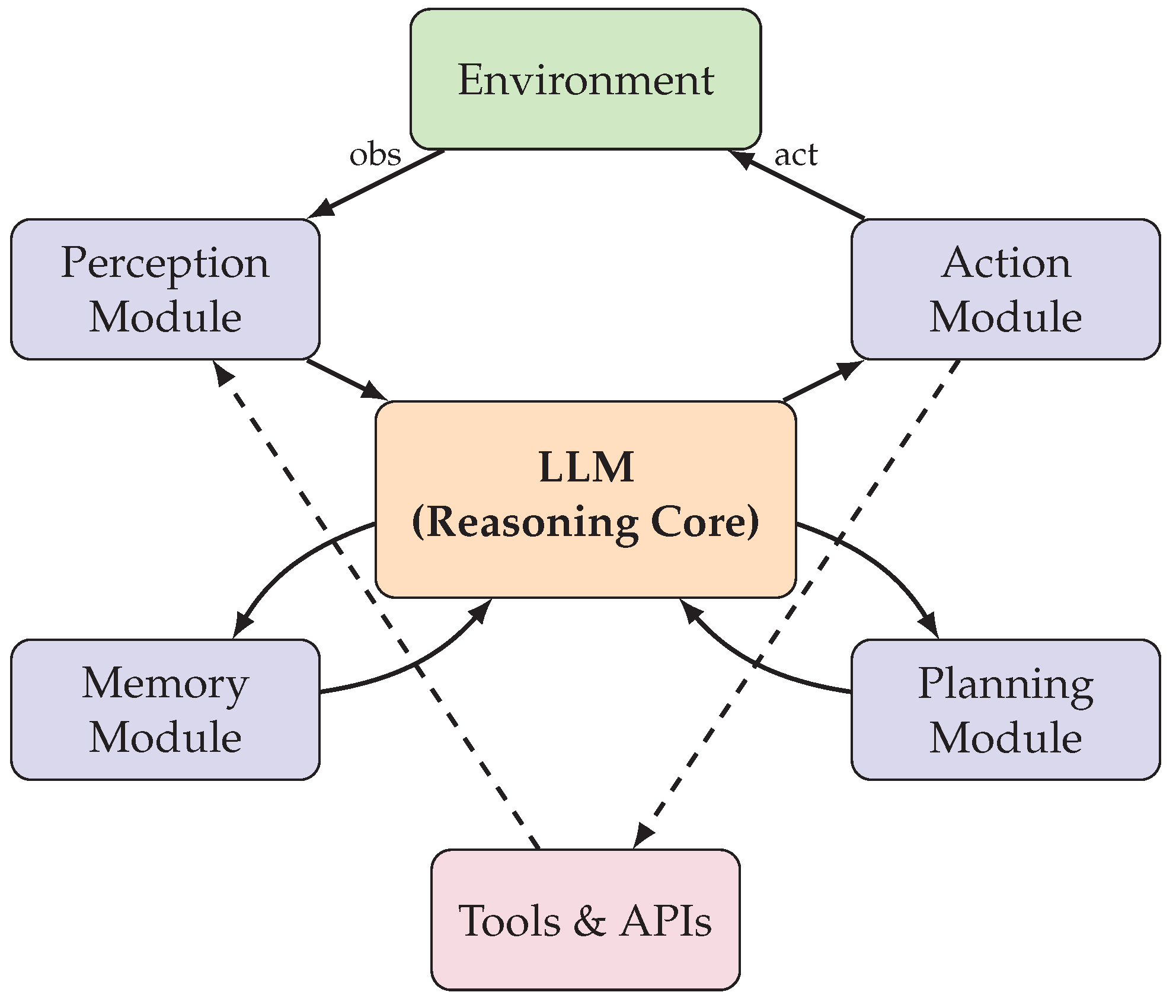

Modern LLM agents typically comprise several interconnected components that collectively enable autonomous behavior. The perception module is responsible for processing environmental observations and converting them into representations suitable for the LLM. In text-based environments, this may involve parsing structured outputs from tools or APIs, while in visual domains, it may require integration with vision encoders or multimodal models. The reasoning module, implemented through the LLM itself, processes the current state and generates plans, decisions, and verbal reasoning traces. Advanced reasoning strategies such as chain-of-thought prompting [

55] and tree-of-thought exploration [

56] enhance this component’s ability to handle complex, multi-step problems.

The memory module maintains information across interaction steps, enabling the agent to learn from experience and maintain context over extended horizons. Memory systems range from simple conversation histories stored in the LLM’s context window to sophisticated architectures with hierarchical storage and retrieval mechanisms [

57]. The action module translates the LLM’s decisions into concrete operations, which may include generating text responses, invoking external tools, executing code, or sending commands to physical actuators. Finally, the planning module orchestrates high-level strategy by decomposing complex goals into manageable subgoals and coordinating their execution over time.

Figure 1 illustrates the general architecture of an LLM agent, showing the interconnections between core components and the cyclic nature of agent operation.

2.4. Evaluation Paradigms

Evaluating LLM agents presents unique challenges compared to traditional NLP benchmarks due to the open-ended nature of agent tasks and the difficulty of defining success criteria for complex goals. Several evaluation paradigms have emerged to address these challenges. Task completion metrics assess whether agents successfully achieve specified objectives, typically measured through binary success rates or partial completion scores. For software engineering tasks, success may be determined by whether generated code passes test suites [

29], while for web navigation, success depends on reaching target states in the browser environment [

31].

Efficiency metrics capture the resources consumed by agents during task execution, including the number of interaction steps, API calls, or tokens processed. These metrics are particularly important for practical deployment where computational costs and latency must be balanced against task performance. Behavioral metrics assess qualitative aspects of agent behavior, such as the coherence of reasoning traces, the appropriateness of tool selections, and the safety of generated actions. Human evaluation remains essential for many of these aspects, though efforts to develop automatic behavioral evaluation are ongoing.

Multi-dimensional benchmarks such as AgentBench [

32] evaluate agents across diverse environments including operating systems, databases, web browsers, and games, providing a more comprehensive picture of general agent capabilities. These benchmarks reveal that current agents exhibit substantial variation in performance across domains, with strong results on some tasks coexisting with failures on others that humans find straightforward.

3. Taxonomy and Overview

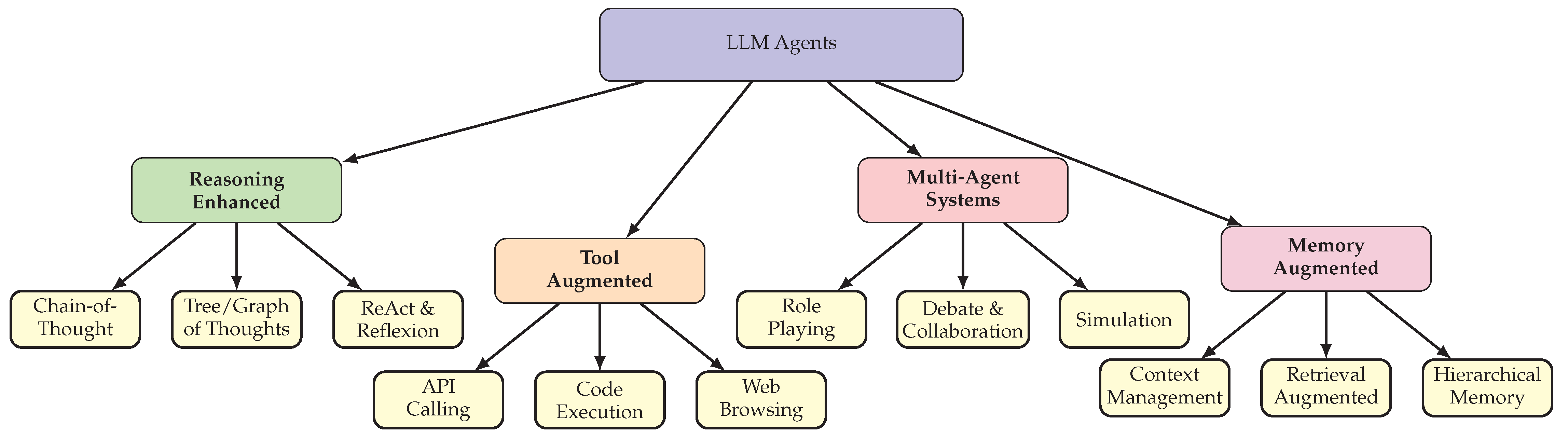

This section presents our proposed taxonomy for organizing the diverse landscape of LLM-based agents. We categorize existing approaches into four fundamental dimensions based on their primary mechanisms for extending LLM capabilities: reasoning enhancement, tool augmentation, multi-agent collaboration, and memory augmentation. While many practical systems combine multiple dimensions, this decomposition provides a principled framework for understanding the core innovations driving the field.

3.1. Taxonomy Overview

Figure 2 illustrates our proposed taxonomy, which organizes LLM agents along four complementary dimensions. Reasoning-enhanced agents focus on improving the quality of LLM decision-making through structured prompting strategies and deliberative search algorithms. Tool-augmented agents extend the action space of LLMs by enabling interaction with external resources including APIs, databases, code interpreters, and web browsers. Multi-agent systems distribute tasks across multiple LLM instances that collaborate through communication protocols, role-playing, and debate. Memory-augmented agents address the limited context windows of LLMs by implementing external memory systems that enable long-term information retention and retrieval.

These four dimensions are complementary rather than mutually exclusive, and state-of-the-art agent systems typically integrate capabilities from multiple categories. For instance, the ReAct framework [

13] combines reasoning traces with action execution, while systems like AutoGPT [

58] and LangChain [

59] integrate all four dimensions into unified architectures. Understanding each dimension in isolation, however, provides crucial insights into the design space and enables principled composition of capabilities.

3.2. Reasoning-Enhanced Agents

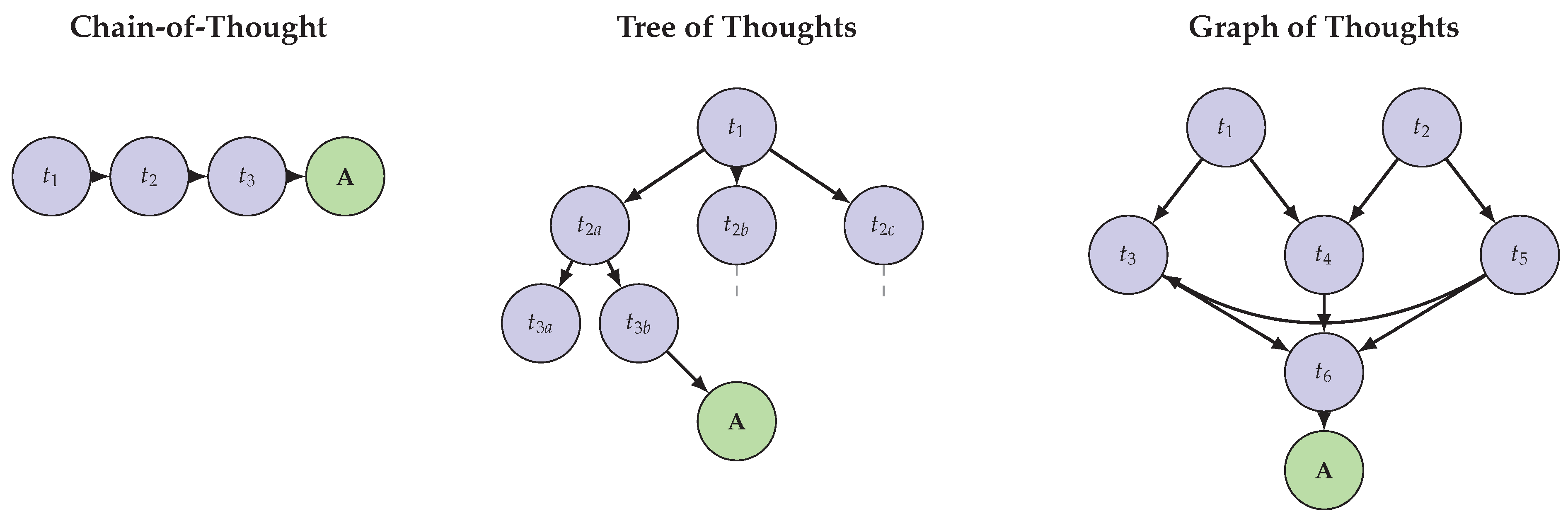

Reasoning-enhanced agents improve LLM decision-making by structuring the generation process to elicit more deliberate and accurate responses. The chain-of-thought (CoT) prompting paradigm [

55] demonstrated that including step-by-step reasoning examples in prompts substantially improves performance on arithmetic, symbolic, and commonsense reasoning tasks. Zero-shot variants [

60] achieve similar benefits through simple trigger phrases like “Let’s think step by step,” suggesting that LLMs possess latent reasoning capabilities that can be activated through appropriate prompting.

Beyond linear chains, tree-structured and graph-structured approaches enable exploration of multiple reasoning paths. Tree of Thoughts [

56] maintains a tree of partial solutions that can be expanded through breadth-first or depth-first search, with the LLM itself serving as both the generator and evaluator of candidate thoughts. Graph of Thoughts [

61] further generalizes this framework by allowing arbitrary connections between thought nodes, enabling operations such as aggregation and refinement that are not possible in tree structures. Self-consistency [

62] takes a complementary approach by sampling multiple reasoning chains and selecting the most consistent answer through majority voting.

The ReAct paradigm [

13] synergizes reasoning and acting by interleaving verbal reasoning traces with environment actions in an alternating fashion. This approach enables the model to ground its reasoning in observations while using reasoning to inform action selection, achieving strong performance on question answering and interactive decision-making tasks. Reflexion [

63] extends this paradigm by incorporating self-reflection, where agents verbally analyze their failures and use these reflections to improve subsequent attempts without any gradient updates.

3.3. Tool-Augmented Agents

Tool-augmented agents extend the capabilities of LLMs by enabling them to invoke external tools and services. This approach addresses fundamental limitations of pure language models, including their inability to access current information, perform precise calculations, and interact with external systems. Toolformer [

14] pioneered the self-supervised approach to tool use, training models to autonomously decide when and how to invoke tools such as calculators, search engines, and translation systems.

API-calling capabilities have been substantially enhanced through dedicated training and evaluation frameworks. ToolLLM [

64] introduces a comprehensive dataset of over 16,000 real-world APIs along with a training recipe that enables open-source models to achieve competitive tool-use performance. Gorilla [

65] specifically targets API documentation retrieval and accurate API call generation, demonstrating that retrieval-augmented approaches can reduce hallucination in tool invocation. The introduction of function calling capabilities in commercial APIs such as OpenAI’s function calling [

66] has further standardized the interface between LLMs and external tools.

Code execution represents a particularly powerful form of tool augmentation, enabling agents to leverage the full expressivity of programming languages. Program-aided language models (PAL) [

67] decompose reasoning problems into programmatic solutions that are executed by interpreters, achieving state-of-the-art results on mathematical reasoning benchmarks. WebGPT [

68] and subsequent systems demonstrate that web browsing capabilities enable agents to access current information and verify factual claims, substantially reducing hallucination rates on knowledge-intensive tasks.

3.4. Multi-Agent Systems

Multi-agent systems distribute problem-solving across multiple LLM instances that interact through structured communication protocols. This approach offers several advantages including task decomposition, diversity of perspectives, and emergent collaborative behaviors. The CAMEL framework [

69] introduced role-playing as a mechanism for autonomous agent cooperation, where agents assume complementary roles such as instructor and assistant to collaboratively solve tasks without human intervention.

Generative Agents [

21] demonstrated the potential for LLM-based agents to exhibit believable social behaviors in simulated environments. By equipping agents with memory systems, reflection capabilities, and planning modules, the researchers created a small town populated by 25 agents that autonomously formed relationships, spread information, and coordinated activities. This work highlighted the emergent properties that can arise from interactions between multiple LLM agents and opened new avenues for social simulation research.

Software development has emerged as a compelling application domain for multi-agent collaboration. MetaGPT [

70] organizes multiple agents into a simulated software company with roles including product manager, architect, and engineer, achieving strong performance on code generation benchmarks. ChatDev [

71] similarly structures agents according to the software development lifecycle, enabling collaborative design, coding, testing, and documentation. AutoGen [

72] provides a flexible framework for defining custom multi-agent conversations, supporting diverse patterns including sequential chat, group discussion, and hierarchical delegation.

3.5. Memory-Augmented Agents

Memory-augmented agents address the fundamental limitation of finite context windows by implementing external memory systems that persist across interactions. Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) [

7] established the foundational paradigm by combining parametric knowledge stored in model weights with non-parametric knowledge retrieved from external databases. This approach enables models to access current information and domain-specific knowledge without requiring retraining.

MemGPT [

57] takes inspiration from operating system memory hierarchies to implement a tiered memory architecture for LLM agents. The system distinguishes between main context (analogous to RAM) and external context (analogous to disk storage), with the agent autonomously managing data movement between tiers through function calls. This enables effectively unbounded context while maintaining the responsiveness of limited context windows for immediate interactions.

Generative Agents [

21] implement a sophisticated memory architecture that includes a memory stream for recording observations, a retrieval mechanism that combines recency, importance, and relevance, and a reflection process that synthesizes higher-level insights from accumulated memories. This architecture enables agents to maintain coherent personalities and remember past interactions over extended simulation periods, demonstrating the importance of structured memory for believable agent behavior.

Table 1 provides a comprehensive comparison of representative methods across the four taxonomic categories, summarizing their key characteristics including primary mechanisms, training requirements, and notable capabilities.

3.6. Integration and Frameworks

The practical deployment of LLM agents typically requires integration across multiple taxonomic dimensions. LangChain [

59], launched in October 2022, emerged as one of the first comprehensive frameworks for building agent applications, providing abstractions for chains, tools, memory, and agent executors. The framework’s modular design enables flexible composition of components while standardizing interfaces between different subsystems.

AutoGPT [

58] garnered significant attention in early 2023 as one of the first demonstrations of fully autonomous agent behavior, automatically decomposing goals into subtasks and iteratively working toward completion. While limited by tendency toward loops and high API costs, AutoGPT demonstrated the potential for end-to-end autonomous systems and inspired numerous follow-up projects. More recent frameworks such as TaskWeaver [

73] adopt code-first approaches that leverage the expressivity of programming languages for agent orchestration, while AgentVerse [

74] provides infrastructure for both task-solving and simulation applications of multi-agent systems.

4. Reasoning-Enhanced Agents

Reasoning-enhanced agents represent a fundamental category of LLM agents that improve decision-making quality through structured prompting strategies and deliberative search algorithms [

75,

76]. This section provides a comprehensive analysis of reasoning paradigms, beginning with chain-of-thought approaches and progressing through increasingly sophisticated tree and graph-based methods.

4.1. Chain-of-Thought Reasoning

The chain-of-thought (CoT) paradigm introduced by Wei et al. [

55] demonstrated that prompting large language models with step-by-step reasoning examples substantially improves performance on complex reasoning tasks. The key insight is that intermediate reasoning steps, rather than directly predicting final answers, enable models to decompose problems and apply learned reasoning patterns more effectively. Empirical evaluation on arithmetic reasoning benchmarks such as GSM8K showed that CoT prompting with PaLM-540B achieved state-of-the-art accuracy of 56.9%, compared to only 17.9% without chain-of-thought, representing a remarkable improvement attributable solely to prompting strategy.

Zero-shot chain-of-thought [

60,

77] extended this paradigm by showing that the simple prompt “Let’s think step by step” can elicit reasoning behavior without task-specific examples. This finding suggested that large language models possess latent reasoning capabilities that require only minimal triggering to activate. The zero-shot approach increased accuracy on MultiArith from 17.7% to 78.7% and on GSM8K from 10.4% to 40.7% using InstructGPT, demonstrating broad applicability across reasoning domains. Subsequent work identified that the effectiveness of trigger phrases varies across tasks, motivating research into automatic prompt optimization.

Self-consistency [

62] introduced a complementary enhancement by sampling multiple diverse reasoning paths and aggregating their conclusions through majority voting. This approach leverages the intuition that complex problems typically admit multiple valid solution strategies, and consistency across different approaches provides stronger evidence for correctness than any single chain. Formally, given a question

q, self-consistency samples

k reasoning chains

and selects the most frequent answer:

Self-consistency improved CoT performance by 17.9% on GSM8K, 11.0% on SVAMP, and 12.2% on AQuA, establishing it as a standard component in reasoning agent architectures. The method requires no additional training and works with any language model capable of chain-of-thought reasoning.

Least-to-most prompting [

78] addresses the challenge of generalizing to problems more complex than those seen in prompts. The approach decomposes complex problems into simpler subproblems that are solved sequentially, with each solution informing subsequent steps. On the SCAN benchmark for compositional generalization, least-to-most prompting achieved 99.7% accuracy on the length generalization split, compared to only 16% for standard chain-of-thought, demonstrating superior ability to handle novel problem complexities. Plan-and-solve prompting [

79] similarly addresses multi-step reasoning by first devising a plan that divides the task into subtasks, then executing the plan step by step, consistently outperforming zero-shot CoT across diverse benchmarks.

4.2. Tree and Graph-Based Deliberation

While chain-of-thought produces linear reasoning sequences, many problems benefit from exploring multiple solution paths and comparing alternatives [

80]. Tree of Thoughts (ToT) [

56] generalizes CoT by maintaining a tree of partial solutions that can be expanded through breadth-first or depth-first search. Recent work on knowledge-augmented planning [

81] addresses planning hallucination by incorporating explicit action knowledge. Each node in the tree represents an intermediate reasoning state, and the LLM serves dual roles as both generator of candidate expansions and evaluator of their promise. This enables deliberate exploration and backtracking when initial attempts prove unfruitful.

The ToT framework can be formalized as a search over a tree

where each node

represents a partial solution state. Given a state

s, the LLM generates candidate thoughts

with branching factor

b, and evaluates each through a value function

:

The search algorithm (BFS or DFS) expands nodes based on these values until reaching a solution or exhausting the search budget.

ToT demonstrated dramatic improvements on tasks requiring strategic planning and exploration. On the Game of 24, where the objective is to combine four numbers using arithmetic operations to obtain 24, GPT-4 with standard prompting solved only 4% of problems while ToT achieved 74% success rate. Similarly, on creative writing tasks requiring coherent paragraph generation with constraints, ToT produced outputs that human evaluators rated significantly higher than those from chain-of-thought or standard prompting. The framework’s flexibility allows customization of search algorithms and evaluation criteria for different problem domains.

Graph of Thoughts (GoT) [

61] further extends the deliberation paradigm by representing reasoning as an arbitrary directed graph rather than a tree. This enables operations not possible in tree structures, including aggregation of multiple thought branches into unified conclusions and refinement of earlier thoughts based on subsequent discoveries. GoT improved sorting quality by 62% over ToT while reducing computational costs by over 31%, demonstrating that more flexible reasoning topologies can simultaneously improve quality and efficiency. The framework has been applied to diverse tasks including document merging, set operations, and keyword extraction.

Self-ask [

82] introduced a related approach where the model explicitly asks and answers follow-up questions before addressing the main query. This compositional structure naturally decomposes multi-hop reasoning into single-hop subquestions that can be answered individually. The structured format also enables seamless integration with search engines, where follow-up questions can be routed to external information sources rather than relying solely on the model’s parametric knowledge. This combination of self-decomposition and retrieval augmentation achieved strong results on multi-hop question answering benchmarks.

Figure 3 illustrates the structural differences between Chain-of-Thought, Tree of Thoughts, and Graph of Thoughts reasoning paradigms.

4.3. Reasoning with Action

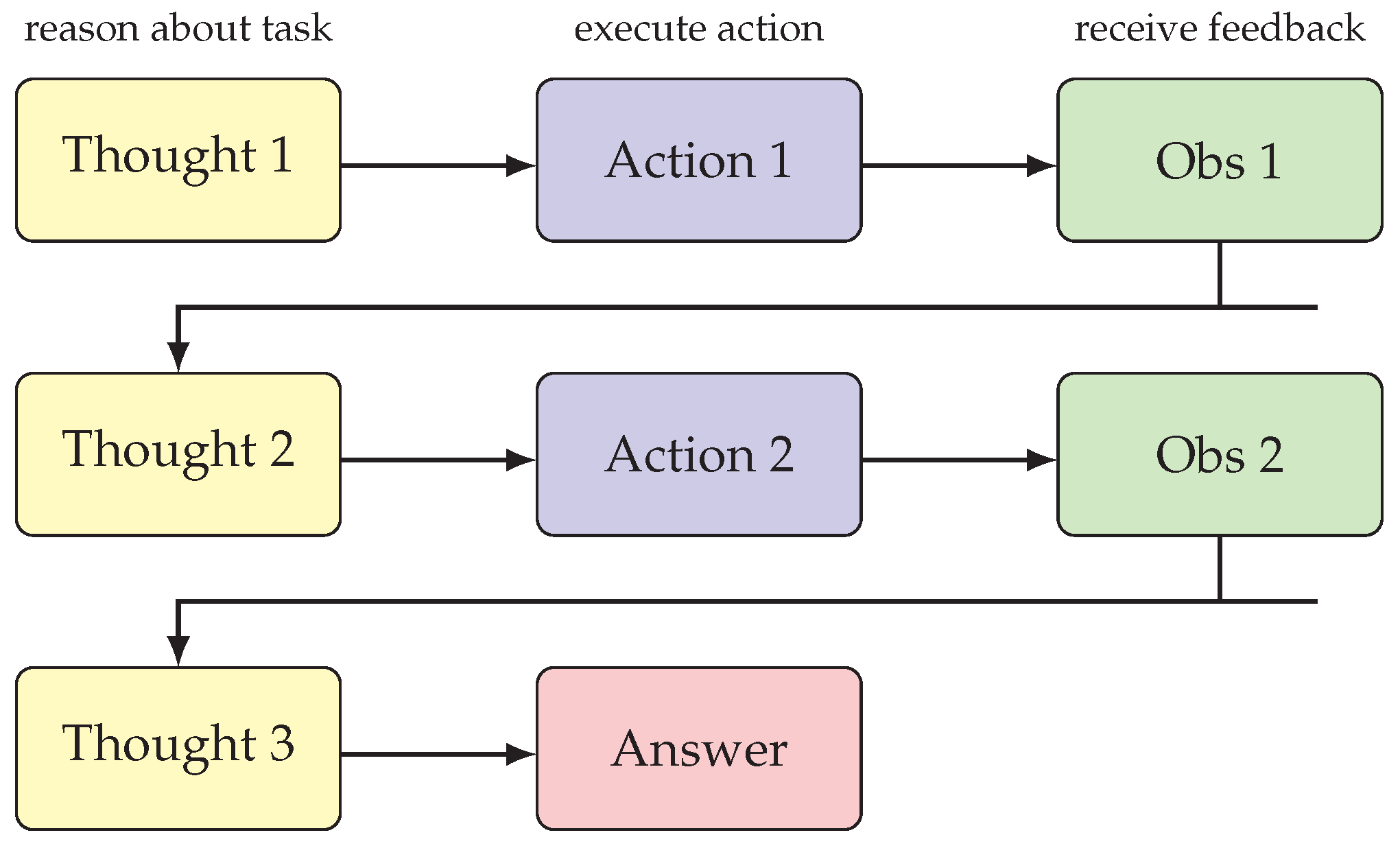

The ReAct paradigm [

13] represents a pivotal advancement that synergizes reasoning and acting in an interleaved fashion. Rather than separating reasoning and action into distinct phases, ReAct agents alternate between generating verbal reasoning traces that interpret observations and plan next steps, and taking actions that query external sources or modify the environment. This tight coupling enables reasoning to be grounded in concrete observations while actions are informed by deliberate reasoning.

Figure 4 illustrates the ReAct interaction loop, showing how thought, action, and observation interleave to solve complex tasks.

ReAct achieved notable top 5% recognition at ICLR 2023 and demonstrated strong performance across diverse benchmarks. On HotPotQA [

83], ReAct with GPT-3 outperformed both pure reasoning (chain-of-thought) and pure acting (action generation without reasoning traces) approaches, achieving a 6% improvement in exact match score over the best baseline. The framework proved particularly effective when actions could provide new information relevant to the reasoning process, creating a productive feedback loop between thought and observation.

Reflexion [

63] extends ReAct by incorporating explicit self-reflection after task completion or failure. Rather than immediately attempting tasks again, Reflexion agents generate verbal analyses of what went wrong and how to improve, storing these reflections in an episodic memory buffer. On subsequent attempts, the agent conditions its behavior on accumulated reflections, enabling learning from experience without gradient updates. This “verbal reinforcement learning” achieved significant improvements on code generation benchmarks, including state-of-the-art performance on HumanEval with 91% pass@1 accuracy.

Self-Refine [

84] demonstrates that iterative self-improvement can enhance outputs across diverse tasks. The approach generates an initial output, then uses the same LLM to provide feedback and refine the output, repeating this cycle until convergence or a maximum iteration count. Across seven tasks ranging from dialogue generation to mathematical reasoning, Self-Refine improved task performance by approximately 20% absolute compared to single-shot generation. The method requires no additional training data and works with any sufficiently capable language model, making it broadly applicable.

CRITIC [

85] addresses the observation that LLMs alone cannot reliably verify their own outputs without external grounding. The framework enables models to validate and revise outputs through interaction with external tools such as search engines and code interpreters. On question answering tasks, CRITIC with ChatGPT achieved 7.7 F1 improvement across three benchmarks, while on mathematical reasoning, it provided 7.0% absolute gains. The results highlight the critical importance of external feedback for enabling reliable self-correction in LLM agents.

4.4. Agent Fine-Tuning for Reasoning

While prompting-based approaches avoid the computational cost of training, fine-tuning can yield agents with more robust and efficient reasoning capabilities. FireAct [

86] investigates fine-tuning language models on agent trajectories generated by more capable models such as GPT-4. The approach collects successful reasoning-action traces across multiple tasks and uses them to fine-tune smaller models in a distillation-like setup. Fine-tuning Llama2-7B with just 500 agent trajectories led to 77% improvement on HotPotQA while reducing inference costs by 70% compared to prompting GPT-4 directly.

The benefits of fine-tuning extend beyond performance to include improved robustness and reduced sensitivity to prompt variations. FireAct showed that fine-tuned models maintained strong performance even when observations were noisy or partially missing, with only 5.1% drop compared to 28.0% for prompted models in adversarial settings. Multi-method fine-tuning, where training data combines trajectories from different prompting strategies, can further improve generalization, though optimal combinations vary across base models. These findings suggest that agent fine-tuning represents a promising direction for developing practical agent systems with predictable behavior.

4.5. Summary and Comparative Analysis

Table 2 summarizes the key characteristics of reasoning-enhanced agent approaches. Chain-of-thought methods provide accessible improvements through prompting alone but are limited to linear reasoning. Tree and graph-based approaches enable more sophisticated exploration but incur higher computational costs. ReAct-style methods excel in interactive settings where reasoning can be grounded in observations, while fine-tuning approaches offer the best combination of performance and efficiency for deployment.

5. Tool-Augmented Agents

Tool-augmented agents extend the capabilities of large language models by enabling them to interact with external tools, APIs, and computational resources. This section examines the key paradigms for tool augmentation, including self-supervised tool learning, API integration frameworks, code execution engines, and web browsing capabilities.

5.1. Foundations of Tool Use

The integration of external tools addresses several fundamental limitations inherent to pure language models. First, LLMs possess only parametric knowledge frozen at training time, making them unable to access current information or domain-specific databases. Second, while LLMs can approximate arithmetic and symbolic reasoning, they remain prone to errors that even simple calculators would never make. Third, language models cannot directly interact with external systems such as databases, file systems, or web services. Tool augmentation addresses all three limitations by enabling LLMs to delegate appropriate subtasks to specialized tools while orchestrating the overall problem-solving process.

Toolformer [

14] established the paradigm of self-supervised tool learning, where models learn when and how to invoke tools without explicit supervision. The approach trains models to insert API calls into text in positions where doing so improves perplexity on subsequent tokens. By optimizing for this self-supervised objective, the model learns to use tools including calculators, search engines, translation systems, and calendars in contextually appropriate ways. Toolformer achieved substantially improved zero-shot performance across diverse tasks, often matching or exceeding much larger models that lack tool access.

The mechanism underlying Toolformer involves first sampling potential API call positions and arguments from a prompted model, then filtering these candidates based on whether including the API response reduces perplexity. Formally, a tool call

c at position

i is retained if:

where

L denotes the language model loss,

is the tool response, and

is a threshold. The surviving examples are used to fine-tune the model to generate tool calls autonomously. This self-supervised approach requires only a handful of demonstrations for each tool and can be extended to new tools without architectural changes. The key insight is that language models possess sufficient world knowledge to determine when tool assistance would be beneficial, and this knowledge can be distilled into tool-using behavior through targeted fine-tuning.

5.2. API Integration and Function Calling

The practical deployment of tool-augmented agents requires robust mechanisms for discovering, selecting, and invoking APIs. OpenAI’s function calling capability [

66], introduced in June 2023, established a standardized interface where developers describe available functions in JSON schema format, and the model outputs structured JSON arguments for function invocation. This approach separates the concerns of function selection and argument generation from actual execution, enabling flexible integration with arbitrary backend services while maintaining safety through application-controlled execution.

Gorilla [

65] specifically targets the challenge of accurate API call generation, recognizing that hallucination of incorrect API names, parameters, or usage patterns represents a significant barrier to reliable tool use. The system combines fine-tuning on curated API documentation with retrieval augmentation, enabling adaptation to documentation changes at test time without retraining. Gorilla achieved state-of-the-art performance on API call accuracy, surpassing GPT-4 on the APIBench dataset while maintaining the flexibility to incorporate new APIs through document retrieval. The retriever-aware training approach ensures that the model learns to leverage retrieved documentation effectively rather than relying solely on memorized API knowledge.

ToolLLM [

64] addresses the challenge of scaling tool use to thousands of real-world APIs. The framework constructs ToolBench, a comprehensive dataset covering over 16,000 APIs from the RapidAPI marketplace, along with automatically generated instructions and solution paths. To enable efficient navigation of large API spaces, ToolLLM introduces a depth-first search-based decision tree algorithm that enables models to explore multiple reasoning traces and backtrack from unsuccessful attempts. The resulting ToolLLaMA model demonstrates strong generalization to unseen APIs, achieving comparable performance to ChatGPT on tool-use tasks while enabling deployment with open-source models.

5.3. Code Execution and Program Synthesis

Code execution represents a particularly powerful modality for tool augmentation, as it enables agents to leverage the full expressivity of programming languages for computation, data manipulation, and system interaction. Program-aided language models (PAL) [

67] pioneered the approach of generating programs as intermediate reasoning steps, with actual computation delegated to an interpreter. This separation of concerns allows the LLM to focus on problem decomposition and program structure while avoiding arithmetic errors that plague pure language model reasoning.

PAL demonstrated dramatic improvements on mathematical reasoning benchmarks. On GSM8K, PAL with Codex outperformed PaLM-540B using chain-of-thought by an absolute 15%, despite using a substantially smaller model. The key advantage is that generated programs can be verified for syntactic correctness and tested on examples, providing feedback mechanisms not available for free-form text reasoning. Moreover, programmatic solutions are inherently more precise, avoiding the ambiguity and approximation that can accumulate in natural language reasoning chains.

HuggingGPT [

87], also known as JARVIS, extends code execution to orchestrate diverse AI models as tools. The system uses ChatGPT as a controller that plans task decomposition, selects appropriate models from the Hugging Face ecosystem, executes selected models on task inputs, and generates integrated responses. This meta-learning approach enables handling of complex multimodal tasks by composing specialized models for subtasks including image generation, speech recognition, and object detection. HuggingGPT successfully integrates hundreds of models across 24 task types, demonstrating the potential for LLMs to serve as general-purpose AI orchestrators.

TaskWeaver [

73] adopts a code-first philosophy for agent orchestration, converting user requests into executable code that coordinates plugins and manages stateful computation. Unlike approaches that treat code as one tool among many, TaskWeaver uses code as the primary representation for plans and actions, leveraging programming language constructs for control flow, error handling, and data transformation. This design enables handling of complex data structures and domain-specific operations while maintaining interpretability through generated code artifacts.

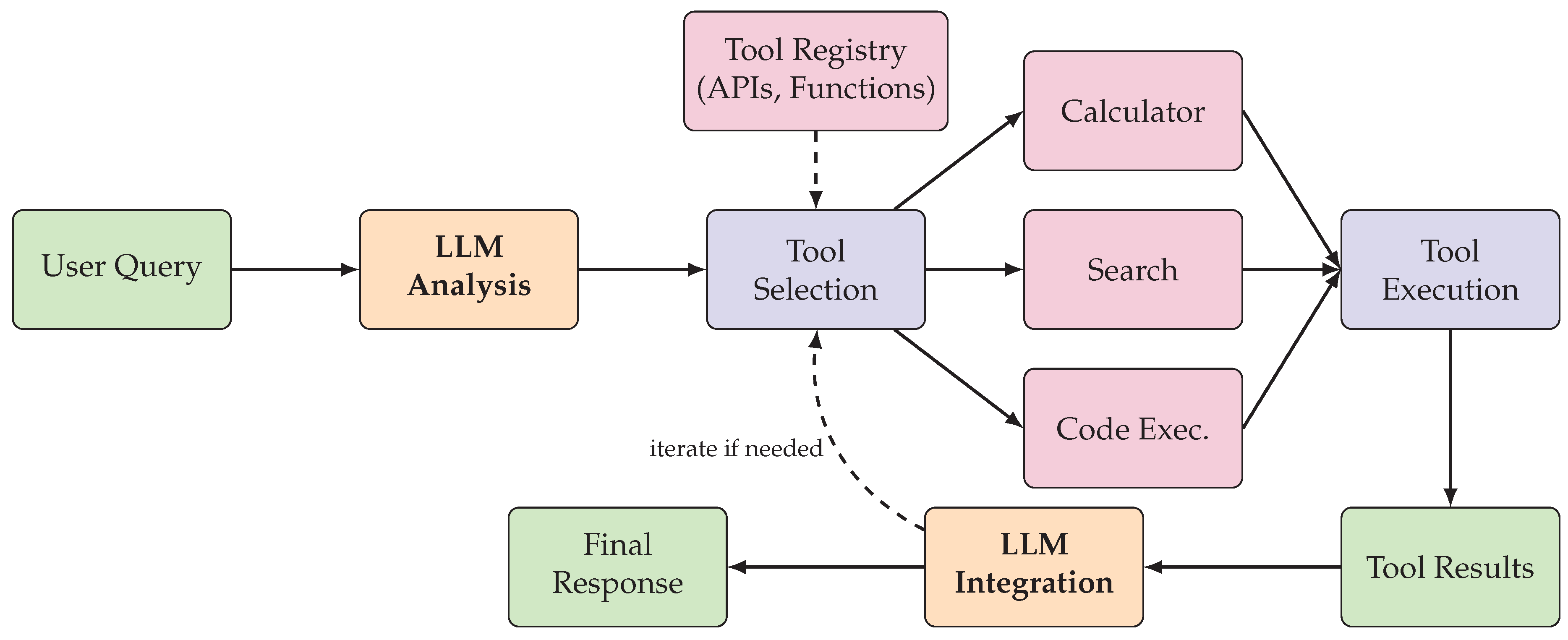

Figure 5 illustrates the general pipeline for tool-augmented agent operation, showing how the LLM orchestrates tool discovery, selection, invocation, and result integration.

5.4. Web Browsing and Information Retrieval

Web browsing capabilities enable agents to access current information, verify claims against authoritative sources, and interact with web-based services. WebGPT [

68] established foundational approaches by fine-tuning GPT-3 to operate a text-based web browser for answering questions. The system learns to issue search queries, navigate search results, and extract relevant information through imitation learning on human demonstrations. Subsequent optimization with human feedback improved answer quality to the point where model responses were preferred over human-written answers 56% of the time.

WebGPT demonstrated substantial improvements in factual accuracy through its browsing capability. On TruthfulQA, WebGPT models outperformed all GPT-3 variants on both truthfulness and informativeness metrics. Critically, the percentage of truthful and informative answers increased with model size for WebGPT, unlike base GPT-3 where scaling provided minimal improvements. This finding suggests that grounding in retrieved information enables more beneficial scaling of factual knowledge capabilities.

Mind2Web [

88] introduced the first large-scale benchmark for generalist web agents, comprising over 2,000 tasks across 137 real websites spanning 31 domains. The benchmark evaluates agents on their ability to follow natural language instructions to accomplish diverse web tasks including form filling, navigation, and information extraction. Evaluation revealed significant gaps between current models and human performance, with the best approaches achieving only around 50% accuracy on element selection compared to human levels exceeding 90%. This benchmark has catalyzed research into more capable web agents.

WebArena [

31] advances web agent evaluation by providing a realistic, reproducible environment with self-hosted websites representing e-commerce, social forums, software development, and content management domains. The benchmark includes 812 tasks designed to emulate authentic human web use, with evaluation based on functional correctness rather than surface-level metrics. Experiments revealed that even GPT-4-based agents achieved only 14.41% task success compared to 78.24% human performance, highlighting substantial room for improvement. The controlled environment enables reproducible evaluation and systematic analysis of failure modes.

5.5. Multimodal Tool Integration

Recent advances have extended tool augmentation to multimodal settings where agents must process and generate content across text, images, audio, and video. Visual language models such as GPT-4V enable agents to perceive visual information directly, reducing reliance on separate vision tools. However, the integration of specialized tools for tasks such as image generation, video editing, and 3D modeling remains important for achieving high-quality outputs in specialized domains.

The orchestration of multimodal tools introduces unique challenges including modality alignment, format conversion, and quality assessment across different content types. Systems like HuggingGPT [

87] address these challenges by maintaining explicit representations of input-output modalities for each available tool, enabling automatic planning of tool chains that respect modality constraints. The success of such systems demonstrates that LLMs can effectively coordinate diverse specialized tools to accomplish complex multimodal objectives.

5.6. Summary

Tool-augmented agents substantially extend the capabilities of language models by enabling access to external computation, information, and services.

Table 3 summarizes key approaches across different tool modalities. The field continues to evolve rapidly, with ongoing work addressing challenges including tool discovery, composition, and verification.

6. Multi-Agent Systems

Multi-agent systems distribute problem-solving across multiple LLM instances that interact through structured communication protocols [

89,

90]. This paradigm offers several advantages over single-agent approaches, including task decomposition through role specialization, diversity of perspectives that can improve solution quality, and emergent collaborative behaviors that mirror human teamwork. This section examines the foundational frameworks, communication protocols, and application patterns that characterize LLM-based multi-agent systems.

6.1. Role-Playing and Autonomous Cooperation

The CAMEL framework [

69] introduced role-playing as a mechanism for enabling autonomous cooperation between LLM agents without human intervention. The system assigns complementary roles to different agents, such as an AI user that provides instructions and an AI assistant that executes them, and uses inception prompting to guide their interaction toward task completion. A task specifier agent first elaborates an initial idea into a well-defined task, which the user and assistant agents then collaboratively solve through multi-turn dialogue.

CAMEL revealed several challenges inherent to autonomous multi-agent cooperation. Conversation deviation occurs when agents gradually drift from the original task objective, potentially exploring tangential or irrelevant topics. Role flipping happens when agents confuse their assigned roles, with the assistant providing instructions or the user attempting to execute tasks. Establishing appropriate termination conditions proved difficult, as agents may declare completion prematurely or continue indefinitely without reaching solutions. These observations have informed subsequent work on more robust multi-agent coordination.

The DERA framework [

91] specifically targets knowledge-intensive tasks by structuring dialog between two specialized agents: a Researcher that processes information and identifies crucial problem components, and a Decider that integrates the Researcher’s findings to make final judgments. This division of labor mirrors expert consultation processes, where information gathering and synthesis are separated from decision-making. On medical question answering tasks, DERA demonstrated significant improvements over single-agent baselines, achieving GPT-4 level performance on the MedQA dataset with explicit reasoning traces that enhance interpretability.

6.2. Software Development with Multiple Agents

Software development has emerged as a compelling domain for multi-agent collaboration due to its inherent structure of specialized roles and well-defined workflows. MetaGPT [

70] organizes multiple agents into a simulated software company with roles including product manager, architect, project manager, and engineer. The framework encodes standardized operating procedures (SOPs) into prompt sequences, guiding agents through structured workflows that mirror professional software development practices. Critically, MetaGPT requires agents to produce structured outputs such as requirements documents, design artifacts, and interface specifications, which serve as intermediate artifacts that reduce ambiguity and error propagation.

MetaGPT achieved state-of-the-art performance on code generation benchmarks, with 85.9% and 87.7% Pass@1 on HumanEval and MBPP respectively. The framework demonstrated 100% task completion rate on tested scenarios, highlighting the robustness enabled by structured workflows. The use of intermediate documents proved particularly valuable, as it allowed later-stage agents to work from well-specified requirements rather than ambiguous natural language descriptions. This structured approach substantially reduced the hallucination and inconsistency problems that plague less constrained multi-agent systems.

ChatDev [

71] similarly structures agents according to the software development lifecycle phases of design, coding, testing, and documentation. The chat chain architecture decomposes each phase into atomic chat interactions between pairs of agents, enabling fine-grained control over communication while maintaining the benefits of natural language collaboration. The framework employs communicative dehallucination techniques where agents cross-check each other’s outputs, reducing errors through social verification mechanisms. ChatDev demonstrated strong performance on software generation tasks while providing interpretable logs of the development process.

AutoGen [

72] provides a more flexible framework for defining custom multi-agent conversations without prescribing specific organizational structures. The framework supports diverse conversation patterns including two-agent chat, sequential multi-agent chat, group discussion, and hierarchical delegation. Agents can be customized with different LLM backends, system prompts, tool access, and code execution capabilities. This flexibility has enabled applications across mathematics, coding, question answering, operations research, and entertainment domains, demonstrating the generality of the multi-agent conversation paradigm.

6.3. Simulation and Emergent Behavior

Generative Agents [

21] demonstrated that LLM-based agents can exhibit believable social behaviors in simulated environments. The system populated a small village with 25 agents, each possessing a unique identity, occupation, and set of relationships. Agents were equipped with memory systems for recording and retrieving experiences, reflection capabilities for synthesizing higher-level insights, and planning modules for coordinating daily activities. Without explicit programming of social behaviors, agents spontaneously formed relationships, spread information through the community, and coordinated group activities such as parties.

The emergent behaviors observed in Generative Agents included information diffusion, where knowledge introduced to one agent propagated through the social network via conversations, and relationship formation, where agents developed friendships based on shared experiences and compatible personalities. Agents demonstrated coherent personalities over extended periods, remembering past interactions and adjusting behavior accordingly. Human evaluators rated agent behaviors as significantly more believable than ablated versions lacking memory or reflection capabilities, validating the importance of these architectural components.

AgentVerse [

74] provides infrastructure for both task-solving and simulation applications of multi-agent systems. The framework supports dynamic adjustment of agent group composition through recruitment and dismissal based on task requirements. Experiments demonstrated that multi-agent groups consistently outperformed single agents across diverse tasks, with the most significant improvements on complex problems requiring diverse expertise. The emergence of social behaviors including collaboration, competition, and specialization was observed even in task-solving scenarios, suggesting that multi-agent dynamics provide benefits beyond simple task decomposition.

6.4. Debate and Collective Intelligence

Beyond cooperative problem-solving, multi-agent systems can leverage adversarial dynamics to improve solution quality. Debate frameworks pit agents against each other in argumentation, with the expectation that rigorous examination of opposing positions will surface errors and strengthen conclusions. This approach mirrors human practices such as peer review and courtroom proceedings, where adversarial processes are valued for their ability to expose weaknesses.

ProAgent [

92] investigates proactive cooperation in multi-agent settings, where agents must anticipate and adapt to the behaviors of teammates without explicit communication. The framework uses LLMs to reason about teammate intentions and dynamically adjust behavior to complement observed actions. In cooperative game environments like Overcooked-AI, ProAgent achieved superior performance in both AI-AI and AI-human cooperation scenarios, with over 10% improvement over baselines. The ability to cooperate effectively with unknown partners represents an important capability for deployable multi-agent systems.

6.5. Communication Protocols and Coordination

The design of communication protocols significantly impacts multi-agent system performance [

93]. Unstructured natural language communication offers flexibility but can lead to redundancy, ambiguity, and information loss. Structured protocols that define message formats and turn-taking rules can improve efficiency but may constrain the range of expressible interactions. Hybrid approaches that combine structured coordination with natural language content appear promising for balancing these concerns.

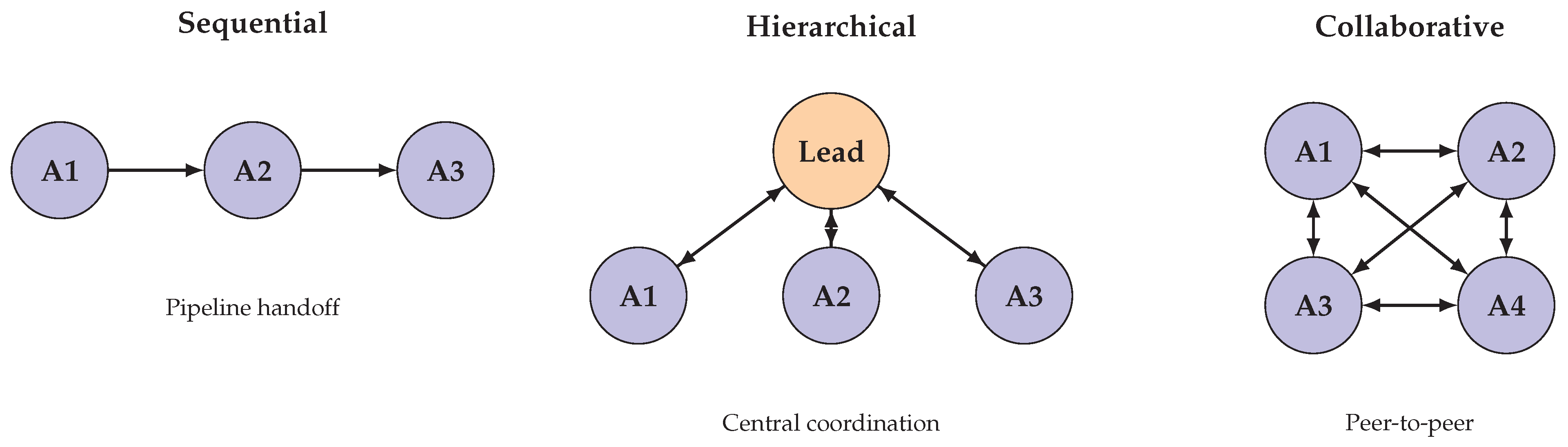

Figure 6 illustrates three fundamental communication topologies employed in multi-agent systems: sequential handoff, hierarchical delegation, and fully connected collaboration.

Memory and context management present particular challenges in multi-agent settings. Individual agents have limited context windows that may be insufficient for tracking extended multi-party conversations. Shared memory systems can provide common ground but introduce synchronization and consistency challenges. Selective attention mechanisms that filter relevant information for each agent based on role and task state represent an active area of research.

6.6. Summary

Multi-agent systems leverage the power of LLMs through coordination and collaboration, enabling capabilities that exceed those of individual agents.

Table 4 summarizes key multi-agent frameworks and their characteristics. The field continues to evolve toward more sophisticated coordination mechanisms and larger-scale deployments.

7. Memory-Augmented Agents

Memory-augmented agents address the fundamental limitation of finite context windows in large language models by implementing external memory systems that persist across interactions [

94,

95,

96]. While modern LLMs can process increasingly long contexts, with some models supporting over 100,000 tokens, practical constraints including computational cost and attention degradation over long sequences motivate the development of explicit memory architectures. This section examines the design principles, implementations, and applications of memory systems for LLM agents.

7.1. Context Window Limitations

The context window of a language model defines the maximum amount of text that can be processed in a single forward pass, fundamentally constraining the temporal horizon over which agents can maintain coherent state. Early transformer models were limited to 512 or 2048 tokens, making extended conversations and document analysis impractical without memory augmentation. While recent models have dramatically expanded context lengths, with Claude supporting 100K tokens and GPT-4 supporting 128K tokens, several limitations persist even at these scales.

First, attention complexity scales quadratically with sequence length in standard transformer architectures, making very long contexts computationally expensive and slow to process. Second, empirical studies have demonstrated that LLMs exhibit degraded performance on information located in the middle portions of long contexts, a phenomenon termed the “lost in the middle” effect. Third, the cost of processing long prompts through API-based services can be prohibitive for applications requiring frequent updates or many concurrent sessions. These factors motivate memory architectures that maintain essential information in compact representations rather than raw context.

7.2. Retrieval-Augmented Generation

Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) [

7] established the foundational paradigm for combining parametric knowledge stored in model weights with non-parametric knowledge retrieved from external databases. The approach augments the model’s input with documents retrieved based on query similarity, enabling access to information not present in training data without requiring model updates. RAG models demonstrated substantial improvements on knowledge-intensive NLP tasks including question answering, fact verification, and open-domain dialogue.

The RAG architecture comprises a retriever component that identifies relevant documents and a generator component that conditions on retrieved content to produce outputs. The retriever typically employs dense passage representations computed by neural encoders, with similarity measured through inner products in embedding space. Documents are retrieved at inference time based on query embeddings, and the top-k results are concatenated with the original query to form the generator input. This design enables seamless integration of dynamic knowledge bases with frozen language model generators.

Subsequent developments have refined RAG architectures along multiple dimensions. Iterative retrieval interleaves retrieval and generation steps, allowing the model to formulate follow-up queries based on initial results. Reranking stages improve retrieval precision by applying more expensive models to rank retrieved candidates. Query expansion and reformulation techniques enhance recall by generating multiple query variants. These enhancements have established RAG as a standard component in knowledge-intensive agent systems.

7.3. Hierarchical Memory Architectures

MemGPT [

57] introduced a hierarchical memory architecture inspired by operating system memory management. The system distinguishes between main context (analogous to RAM) comprising the LLM’s active context window, and external context (analogous to disk storage) comprising persistent databases. The agent autonomously manages data movement between tiers through function calls that read from and write to external storage, conceptually similar to page faults and cache management in traditional computing.

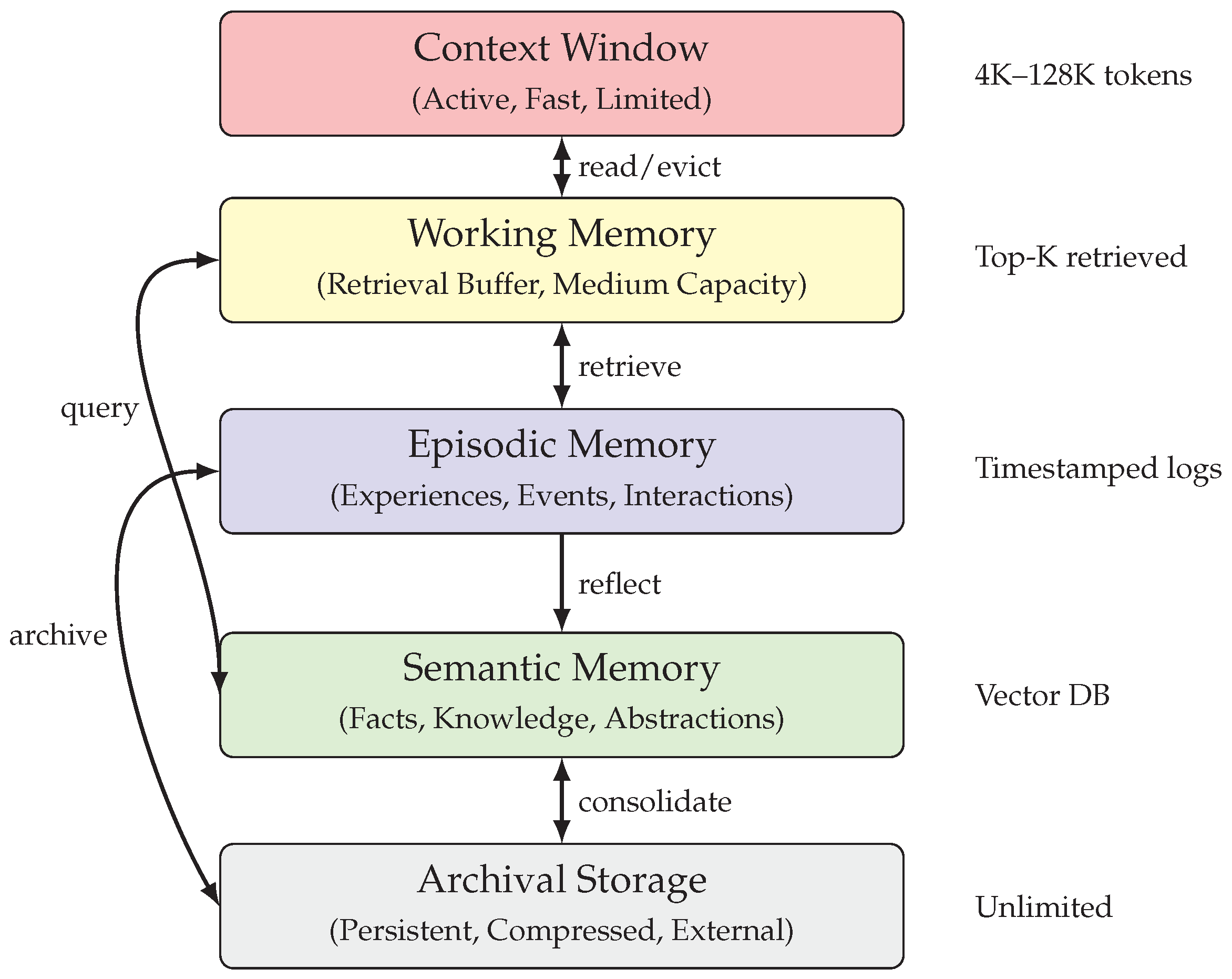

Figure 7 illustrates the hierarchical memory architecture employed in modern memory-augmented agents, showing the relationship between immediate context, working memory, and long-term storage.

This architecture enables effectively unbounded context while maintaining responsive interaction through the limited main context. When relevant information resides in external storage, the agent can retrieve it into main context for processing. When main context becomes full, the agent can evict less immediately relevant information to external storage while retaining retrieval capability. MemGPT was evaluated on conversational agents and document analysis tasks, demonstrating that virtual context management enables performance competitive with models having much larger native context windows.

The design leverages the function calling capabilities of modern LLMs, where the agent can invoke memory operations as tools alongside other actions. Memory operations include reading specific entries by key, searching external storage for relevant content, and writing new observations or synthesized knowledge. The agent learns when to invoke these operations through standard prompting or fine-tuning on memory management demonstrations. This approach treats memory management as an integral part of agent behavior rather than a separate preprocessing step.

7.4. Memory in Generative Agents

Generative Agents [

21] implemented a sophisticated memory architecture designed to support believable social behavior over extended time horizons. The architecture comprises three interconnected components: a memory stream that records observations in natural language, a retrieval function that selects relevant memories based on multiple criteria, and a reflection process that synthesizes higher-level insights from accumulated experiences.

The memory stream maintains a comprehensive record of the agent’s experiences, with each entry containing a description, creation timestamp, and most recent access timestamp. Retrieval considers three factors: recency, with more recent memories weighted higher; importance, with significant events weighted higher; and relevance, with memories semantically similar to the current context weighted higher. The retrieval score for memory

m given query

q is computed as:

where recency decays exponentially with time since last access:

and relevance is computed as cosine similarity between embedding vectors:

The combination of these factors determines which memories surface during recall, enabling contextually appropriate behavior while preserving episodic coherence.

The reflection process addresses the challenge of extracting meaningful patterns from numerous individual memories. Periodically, agents aggregate recent memories and prompt the LLM to generate higher-level observations about patterns, relationships, and insights. These reflections are themselves stored in the memory stream and can be retrieved like primary observations, enabling hierarchical abstraction over experience. Human evaluations confirmed that agents with full memory architectures exhibited significantly more believable and coherent behavior than ablated versions lacking memory or reflection capabilities.

7.5. Episodic and Semantic Memory

Drawing on cognitive science distinctions, some memory architectures explicitly separate episodic memory capturing specific experiences from semantic memory capturing general knowledge. Episodic memories preserve contextual details including when and where events occurred, supporting recall of specific interactions and experiences. Semantic memories abstract away contextual details to capture generalizable facts and relationships, supporting reasoning about categories and typical properties.

This separation enables different retrieval strategies suited to different query types. Questions about specific past interactions benefit from episodic retrieval that considers temporal and contextual similarity. Questions about general facts or typical patterns benefit from semantic retrieval that ignores contextual details in favor of conceptual similarity. Hybrid systems can route queries to appropriate memory stores based on query characteristics or retrieve from both stores and aggregate results.

The formation of semantic memories from episodic experiences mirrors human learning processes where repeated experiences give rise to generalized knowledge. Mechanisms for semantic memory formation include frequency-based abstraction, where commonly occurring patterns are extracted as general rules, and analogy-based transfer, where similarities across episodes support formation of abstract categories. These mechanisms remain active areas of research in memory-augmented agent design.

7.6. Memory Consolidation and Forgetting

As agents accumulate experiences over time, memory systems must address storage growth and the potential for outdated information to interfere with current behavior. Memory consolidation processes compress detailed episodic memories into more compact semantic representations, reducing storage requirements while preserving essential information. Forgetting mechanisms remove or down-weight memories that are outdated, contradicted by newer information, or simply irrelevant to current objectives.

Intelligent forgetting presents significant challenges, as determining which memories can be safely discarded requires understanding their potential future relevance. Time-based decay provides a simple heuristic but may prematurely remove infrequently accessed but important memories. Access-based policies retain frequently used memories but may preserve outdated information that happens to be commonly queried. Importance-based approaches require reliable estimation of memory significance, which itself may depend on future contexts that are unknowable. These tradeoffs parallel fundamental challenges in database design and information retrieval.

7.7. Summary

Memory augmentation enables LLM agents to maintain coherent state and leverage past experience over extended time horizons.

Table 5 summarizes key memory architecture approaches and their characteristics. The design of effective memory systems remains an active research area with important implications for agent capabilities.

8. Applications

LLM agents have been deployed across a diverse range of application domains, demonstrating their versatility and practical utility. This section examines key application areas including software engineering, scientific research, embodied AI, web automation, and enterprise applications, analyzing both the successes achieved and the challenges encountered in each domain.

8.1. Software Engineering

Software engineering represents one of the most active and consequential application domains for LLM agents [

97,

98]. The structured nature of code, availability of execution feedback, and clear success criteria through test suites make software tasks particularly amenable to agent-based approaches. Early work focused on code generation from natural language specifications, with models demonstrating impressive ability to synthesize functions and complete code snippets. Recent work has explored both agent-based and agentless approaches [

99] to software engineering tasks.

The introduction of Devin by Cognition AI [

100] in March 2024 marked a significant milestone as a claimed first fully autonomous AI software engineer. Devin operates with access to a shell, code editor, and browser within a sandboxed environment, enabling it to plan and execute complex engineering tasks from natural language specifications. On the SWE-bench benchmark [

29], Devin resolved 13.86% of issues end-to-end, substantially exceeding the previous state-of-the-art of 1.96%. However, subsequent independent evaluations revealed significant limitations, with only 3 of 20 tested tasks completed satisfactorily, highlighting the gap between benchmark performance and practical reliability.

SWE-agent [

101] introduced the concept of agent-computer interfaces (ACIs) specifically designed for LLM interaction with software systems. Unlike human-oriented interfaces with graphical elements and free-form navigation, ACIs provide structured commands and outputs optimized for language model consumption. This interface design philosophy substantially improved agent performance on software engineering tasks, achieving state-of-the-art results on SWE-bench when combined with capable base models. The work demonstrated that thoughtful interface design can be as important as model capability for agent effectiveness.

OpenHands [

102], evolved from the OpenDevin project, provides an open-source platform for AI software developers as generalist agents. The platform supports diverse software engineering workflows including bug fixing, feature implementation, and code review, with evaluation across 15 benchmarks spanning different aspects of software development. The open-source nature has enabled rapid community contributions and research into agent architectures, tool designs, and evaluation methodologies.

8.2. Scientific Research

LLM agents are increasingly being applied to accelerate scientific research across domains including chemistry, biology, materials science, and mathematics. These applications leverage agents’ ability to process scientific literature, design experiments, analyze data, and generate hypotheses. The combination of domain knowledge in training data with tool access to computational resources and databases enables agents to contribute meaningfully to research workflows.

In chemistry, agents have been developed to assist with synthesis planning, property prediction, and laboratory automation. Systems that combine language models with specialized chemistry tools such as molecular simulators and reaction databases can propose synthetic routes for target compounds and predict reaction outcomes. The ability to reason about molecular structures in natural language while accessing quantitative computational chemistry tools represents a powerful combination for accelerating discovery.

Mathematical reasoning represents another significant application area, building on the strong performance of LLMs on mathematical benchmarks. Agents that combine natural language reasoning with formal proof assistants can tackle problems that neither approach handles well alone. The natural language component enables intuitive problem understanding and strategy formulation, while formal tools provide rigorous verification and search capabilities. This combination has achieved notable results on competition mathematics and theorem proving tasks.

8.3. Embodied AI and Robotics

Embodied AI extends LLM agents into physical environments where they must perceive the world through sensors and act through physical actuators. This domain presents unique challenges including the need for real-time responsiveness, handling of continuous state spaces, and ensuring safe behavior in physical environments. Despite these challenges, LLM-based approaches have demonstrated promising results in robot manipulation, navigation, and human-robot interaction.

Voyager [

103] demonstrated the potential for LLM agents in virtual embodied environments by creating an agent that continuously explores, learns, and accomplishes diverse goals in Minecraft. The system comprises an automatic curriculum for exploration, a skill library for storing and retrieving learned behaviors, and an iterative prompting mechanism that incorporates environmental feedback. Voyager obtained 3.3x more unique items and unlocked technology milestones up to 15.3x faster than baselines, while demonstrating generalization to new Minecraft worlds with novel task specifications.

Inner Monologue [

104] investigated the use of language models for embodied reasoning in robotic settings. Recent surveys on robot intelligence with LLMs [

105] and embodied multi-modal agents [

106] have further advanced this area. The approach enables robots to form internal monologues that interpret observations, plan actions, and adapt to feedback through natural language. By grounding language generation in physical observations and action outcomes, robots can exhibit more robust and adaptive behavior than purely feedforward approaches. The system demonstrated capabilities including multilingual instruction following and interactive problem solving when faced with obstacles.

The HuggingGPT system [

87] demonstrates how LLM orchestration can enable complex multimodal tasks that combine perception, reasoning, and generation. By routing subtasks to appropriate specialized models from the Hugging Face ecosystem, the system can handle requests spanning image understanding, speech processing, and video analysis. This orchestration paradigm provides a path toward general-purpose embodied agents that leverage diverse perceptual and actuation capabilities.

8.4. Web Automation

Web automation applies LLM agents to navigate websites, fill forms, extract information, and complete transactions on behalf of users. The web represents a natural environment for agent deployment due to its structured nature, well-defined action space of clicks and typing, and immediate feedback through page updates. However, the complexity and diversity of real websites present significant challenges for robust automation.

Mind2Web [

88] established the first large-scale benchmark for generalist web agents, revealing substantial gaps between current capabilities and practical requirements. Subsequent work including WebVoyager [

107], AutoWebGLM [

108], and WebAgent [

109] has advanced web navigation capabilities through multimodal understanding and reinforcement learning. The benchmark comprises tasks across 137 websites in 31 domains, with evaluation on element selection accuracy and task completion. Best methods achieved approximately 50% element selection accuracy compared to human levels above 90%, indicating significant room for improvement. The benchmark has catalyzed research into more capable web understanding and interaction.

WebArena [

31] advances evaluation by providing reproducible self-hosted web environments representing realistic domains including e-commerce, forums, and content management. The 812 included tasks emulate authentic human web activities with functional correctness evaluation. GPT-4-based agents achieved only 14.41% task success compared to 78.24% human performance, demonstrating that current agents struggle with the full complexity of web interaction. The controlled environment enables systematic analysis of failure modes and iterative improvement.

OSWorld [

110] extends agent evaluation to general computer use across operating systems including Ubuntu, Windows, and macOS. The benchmark comprises 369 tasks involving real applications, file operations, and multi-application workflows. State-of-the-art models achieved only 12.24% success compared to 72.36% human performance, with primary challenges including GUI element identification and operational knowledge. This benchmark highlights the substantial gap remaining before agents can serve as general computer assistants.

Table 6 provides a comprehensive comparison of LLM agent applications across different domains, summarizing key characteristics, representative systems, and current performance levels.

8.5. Enterprise and Business Applications

Enterprise applications represent a significant opportunity for LLM agent deployment, with potential to automate knowledge work, enhance decision-making, and improve customer service. Customer service chatbots leveraging LLM capabilities can handle a broader range of queries with more natural conversation than traditional rule-based systems. Document processing agents can extract, summarize, and route information from diverse business documents.

Data analysis and business intelligence represent particularly promising application areas. Agents that combine natural language understanding with database querying and visualization tools can enable non-technical users to explore data and generate insights. The ability to translate natural language questions into SQL queries, execute them against databases, and present results in interpretable formats democratizes access to data-driven decision making.

However, enterprise deployment raises significant concerns around accuracy, security, and governance. Hallucination risks are particularly consequential in business contexts where incorrect information can lead to financial or reputational damage. Integration with sensitive data systems requires robust access controls and audit capabilities. Regulatory compliance in domains such as finance and healthcare imposes additional requirements on agent behavior and documentation.

8.6. Timeline of Major Developments

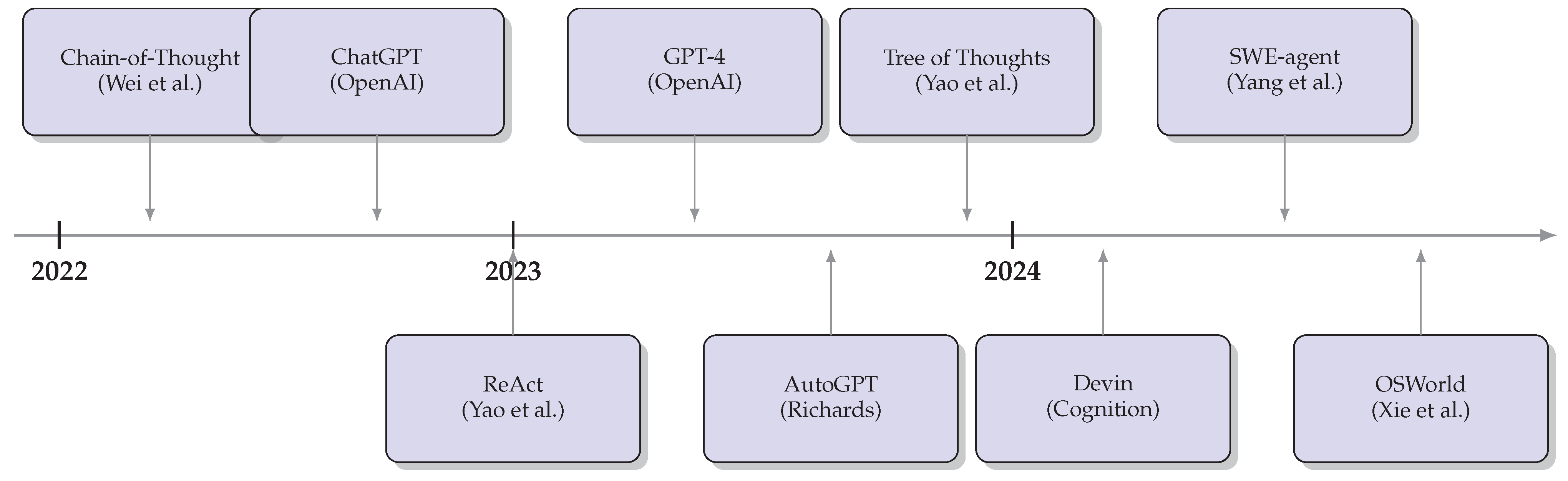

Figure 8 illustrates the evolution of key LLM agent developments from 2022 to 2024. The timeline shows the rapid acceleration of progress following the introduction of ChatGPT and GPT-4, with foundational paradigms established in 2023 and increasingly sophisticated systems emerging in 2024.

9. Benchmarks and Evaluation

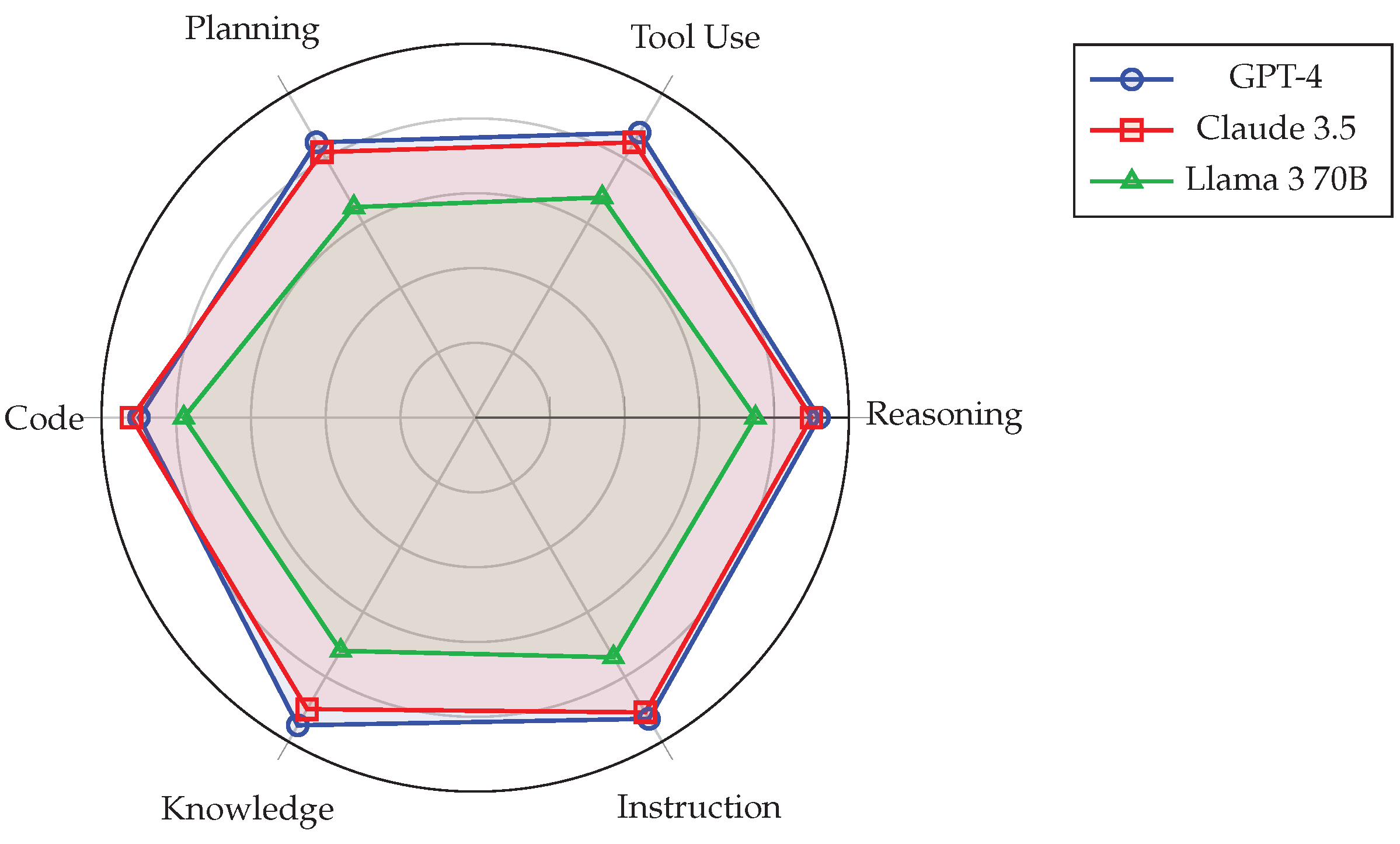

The systematic evaluation of LLM agents requires benchmarks that capture the multi-faceted nature of agent capabilities including reasoning, tool use, planning, and interaction with complex environments. This section surveys the major benchmarks developed for agent evaluation, presents comparative analyses of agent performance, and discusses evaluation methodologies and their limitations.

9.1. General Agent Benchmarks

AgentBench [

32] provides the first comprehensive benchmark designed to evaluate LLMs as autonomous agents across diverse environments. Recent work has introduced TheAgentCompany [

111] for evaluating agents on consequential real-world tasks, while comprehensive surveys on agent evaluation [

112,

113] have systematized evaluation methodologies. The benchmark comprises eight distinct environments spanning operating systems, databases, knowledge graphs, digital card games, lateral thinking puzzles, house-holding simulation, web browsing, and web shopping. Each environment requires different combinations of skills including command generation, query formulation, strategic planning, and interactive navigation.