1. Introduction

Human metapneumovirus (HMPV), a pathogen of the family Pneumoviridae (genus

Metapneumovirus) first identified in 2001, is a significant cause of acute respiratory infections (ARIs) globally [

1]. Reflecting its widespread circulation, infection occurs predominantly in early childhood, with an estimated 50% of children becoming infected by age two and nearly all by age five [

1]. The clinical manifestations of HMPV are diverse, ranging from mild upper respiratory illness to severe conditions such as bronchiolitis and pneumonia, which are estimated to be responsible for 6.2% of hospital admissions for ARI [

2]. Moreover, the clinical burden of HMPV is amplified in the context of co-infections with other pathogens, such as bacteria and fungus, which can lead to critical and potentially lethal complications, especially in vulnerable populations [

3,

4]. This clinical challenge is compounded by the absence of licensed vaccines or specific antiviral therapies, leaving supportive care as the sole management strategy. Thus, HMPV infection represents a significant public health concern.

As an enveloped RNA virus, HMPV possesses a genome of approximately 13 kb containing eight genes. These genes encode nine proteins, three of which—the fusion (F), attachment (G), and small hydrophobic (SH) proteins—are surface glycoproteins crucial for viral function. Genetic diversity, particularly within the

F and

G genes, provides the basis for classifying HMPV into two genetic lineages, designated genotypes A (HMPV-A) and B (HMPV-B) [

5,

6,

7]. These genotypes are further delineated into distinct sublineages, including A1, A2a, A2b, A2c, B1, and B2 [

8,

9]. The prevalence of these genotypes and sublineages varies temporally and geographically, and understanding their circulation dynamics is crucial for public health surveillance. HMPV-B, in particular, co-circulate with or independently cause significant seasonal outbreaks [

10,

11].

HMPV is phylogenetically and clinically related to human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), another major pathogen within the Pneumoviridae family [

12]. For both viruses, the F protein is the primary target of the host neutralizing antibody response, making it the central focus for vaccine and antibody-based intervention development. Extensive research on RSV has identified at least six antigenic sites on its F protein (designated sites Ø, I, II, III, IV, and V), which serve as a valuable framework for understanding pneumovirus antigenicity [

13,

14]. While sites Ø and V are the targets of the most potent neutralizing antibodies in RSV, the corresponding region in HMPV is shielded by a dense network of N-linked glycans, which limits its immunogenicity [

15,

16]. Sites I and II have also been identified as potential targets for neutralizing antibodies in HMPV, although reports characterizing them remain limited [

17]. In contrast, the regions corresponding to sites III and IV in HMPV emerge as some of the most accessible and critical targets for neutralizing antibodies [

17]. Furthermore, sites III and IV are structurally highly conserved between HMPV and RSV, identifying them as prime targets for cross-reactive antibodies capable of neutralizing both viruses [

14].

The F protein is relatively conserved compared to the highly variable G protein, rendering it a promising target for antibody-based interventions and vaccine development. Nevertheless, amino acid substitutions can accumulate during viral circulation, potentially altering antigenicity. Despite the clinical importance of HMPV-B, comprehensive molecular evolutionary analyses of its F gene remain limited. To address this gap, the present study integrates phylogenetic and in silico approaches to elucidate the molecular evolution of the HMPV-B F gene, with the aim of characterizing its genetic diversity and predicting potential changes in antigenic sites.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Sequence Retrieval

We obtained the full-length coding region of the HMPV-B

F gene (positions 3052–4671; 1620 nt for HMPV strain; NCBI Reference Sequence: NC_039199.1) from NCBI Virus (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/virus/vssi/#/) to analyze the molecular evolution on 20 February 2025. The initial dataset was curated by first excluding sequences that contained ambiguous nucleotides (e.g., N, Y, R, or V) or lacked clear collection dates or geographic origins. From the remaining sequences, only those belonging to genotype B were selected for further analysis, based on the genotyping scheme from Nextstrain (

https://clades.nextstrain.org/) on 14 March 2025 [

18]. Then, duplicate sequences (100% identity) were also excluded from the dataset using Clustal Omega (

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/jdispatcher/msa/clustalo) on 26 March 2025 [

19]. Subsequently, five outlier sequences considered to be potential sequencing artifacts were removed to prevent bias: two (JQ413397.1, JQ413401.1) for containing large internal deletions, and three (MK177081.1, MK177095.1, MK177098.1) for exhibiting an unusually high number of unique substitutions. These outliers were considered potential artifacts, such as sequencing errors, which could bias the results of the molecular evolutionary analysis. This curation resulted in a dataset of 509 sequences. Due to constraints inherent in the selective pressure analysis method, the dataset was randomly downsized to a final set of 500 sequences (B1: 212 sequences; B2: 288 sequences). The final dataset comprised strains from 18 countries spanning 1982 to 2024 (

Supplementary Figure S1), with detailed information provided in

Supplementary Table S1.

2.2. Time-Scaled Phylogenetic Tree

A time-scaled phylogenetic tree of the HMPV-B

F gene was constructed using the Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (BMCMC) approach in BEAST version 2.6.7 [

20]. The dataset comprised 501 HMPV sequences, with an HMPV-A reference strain (GenBank accession no. NC_039199.1) included as an outgroup to estimate the divergence time between HMPV-A and HMPV-B. Prior to the BMCMC analysis, the optimal nucleotide substitution model (TrN+I+G) was determined using jModelTest version 2.1.10 [

21]. Subsequently, path-sampling and stepping-stone sampling methods were employed to compare four molecular clock models (strict, relaxed exponential, relaxed log normal, and random local) and two coalescent tree priors (constant population and exponential population). This comparison identified the relaxed exponential clock and the coalescent constant population model as the best fit for the data. The BMCMC analysis was run for 300 million steps, sampling every 3000 steps. Convergence of the chains was assessed in Tracer version 1.7.2 [

22], and an effective sample size (ESS) greater than 200 was accepted for all parameters. The first 15% of samples were discarded as burn-in. The maximum clade credibility (MCC) tree was summarized using TreeAnnotator version 2.6.7 and visualized with FigTree version 1.4.0 (

http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/). Branch support was evaluated using 95% highest posterior density (HPD) intervals. Detailed parameter settings used in the BMCMC analyses are provided in

Supplementary Table S2.

2.3. Bayesian Skyline Analysis and Substitution Rate Estimation

We investigated the historical population dynamics of the HMPV-B

F gene using a Bayesian skyline plot (BSP) model implemented in the BEAST package. The analysis, aimed at estimating changes in effective population size over time, was applied to both the full set of 500 HMPV-B sequences and to each sublineage (B1 and B2). The best substitution and clock models were selected, as described above. For the total HMPV-B dataset, the BMCMC chain was run for 500 million steps, with sampling every 1,000 steps. The visualization of BSPs was presented by Tracer. The mean molecular evolutionary rates (substitutions/site/year) were also estimated using Tracer for the total dataset and for each sublineage separately. Statistical comparisons between genotypes were conducted using unpaired t-tests in EZR [

23], with

p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. The detailed parameters of the BSP analyses are shown in Supplemental

Tables S2.

To identify lineage-specific amino acid substitutions associated with the demographic changes, we analyzed all available sequences in our dataset for the B1 (n = 19) and B2 (n = 29) sublineages from the period of 2004–2009. This timeframe was selected to represent the phase following the major demographic fluctuations, based on the BSP results. Additionally, to evaluate the persistence of identified amino acid variations in recent years, single representative strains detected in 2022 for the B1 lineage (GenBank accession no. PQ634879.1) and in 2024 for the B2 lineage (GenBank accession no. PV052149.1) were included in the analysis. All sequences were aligned and visually compared with the B1 and B2 prototype strains (GenBank accession nos. EU857572.1 and EU857574.1, respectively).

2.4. Phylogenetic Distance Analysis

We assessed the genetic diversity of the HMPV-B

F gene by calculating patristic distances. To this end, maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic trees were reconstructed independently for three distinct datasets: (i) all 500 HMPV-B strains combined, (ii) strains within the B1 sublineage, and (iii) strains within the B2 sublineage. Each tree was inferred using IQ-TREE version 2.2.2.6 [

24], which utilized ModelFinder for automatic model selection and assessed nodal support via 1000 ultrafast bootstrap replicates and the SH-aLRT. Subsequently, all pairwise patristic distances were calculated from each respective tree using Patristic [

25]. The differences in mean distances between the groups were statistically evaluated with an unpaired t-test in EZR, where

p < 0.05 was set as the threshold for significance.

2.5. Analysis of Codon-Specific Selective Pressures

We investigated codon-specific selective pressures on the HMPV-B F protein by analyzing the 500

F gene coding sequences via the Datamonkey web server (

http://www.datamonkey.org/, accessed on 4 July 2025) [

26]. The ratio of non-synonymous (

dN) to synonymous (

dS) substitution rates per site (

dN/

dS) was estimated to infer selective pressures. Evidence for codons evolving under positive selection (

dN/

dS > 1) and negative (purifying) selection (

dN/

dS < 1) was investigated using four complementary methods: Single-Likelihood Ancestor Counting (SLAC), Fixed-Effects Likelihood (FEL), Internal Fixed-Effects Likelihood (IFEL), and Fast Unconstrained Bayesian Approximation (FUBAR). For the likelihood-based methods (SLAC, FEL, and IFEL), a

p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For the Bayesian method (FUBAR), a posterior probability of > 0.9 was used as the threshold for significance.

2.6. Amino Acid Identity Analysis

We assessed the sequence identity of HMPV-B F proteins against an HMPV reference using a sliding-window approach. This analysis represents smoothed identity values averaged across an 80-amino-acid window. First, we generated a 50% consensus sequence for each HMPV-B sublineage. Pairwise amino acid identity was then calculated between these consensus sequences and the HMPV reference (HMPV-A, GenBank: NC_039199.1) using a window size of 80 residues with a step size of 5 residues. From the resulting smoothed identity curves, we specifically calculated the mean percent identity for the core regions of neutralizing antibody binding sites. For the purpose of this study, these core regions were defined based on previous reports [

15,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32] as follows: site Ø (amino acids 54–65 and 170–183), site I (amino acids 23–31 and 282–284), site II (amino acids 233–238), site III (amino acids 277–281), site IV (amino acids 395–405), and site V (amino acids 136–156). This analysis was implemented in Python version 3.12.11 within the Google Colaboratory environment, utilizing the pandas library version 2.2.2 for data manipulation and matplotlib version 3.10.0 for plotting.

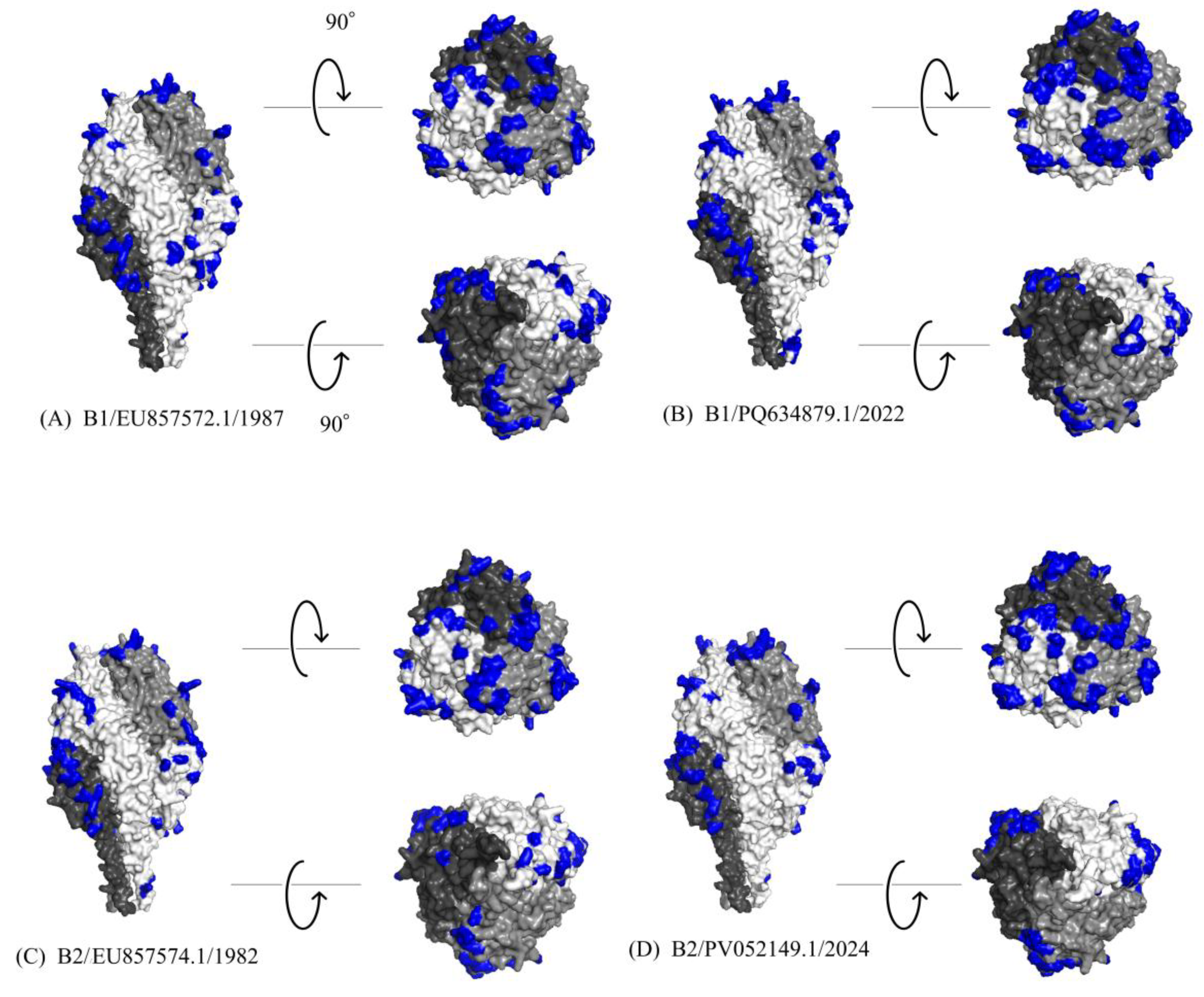

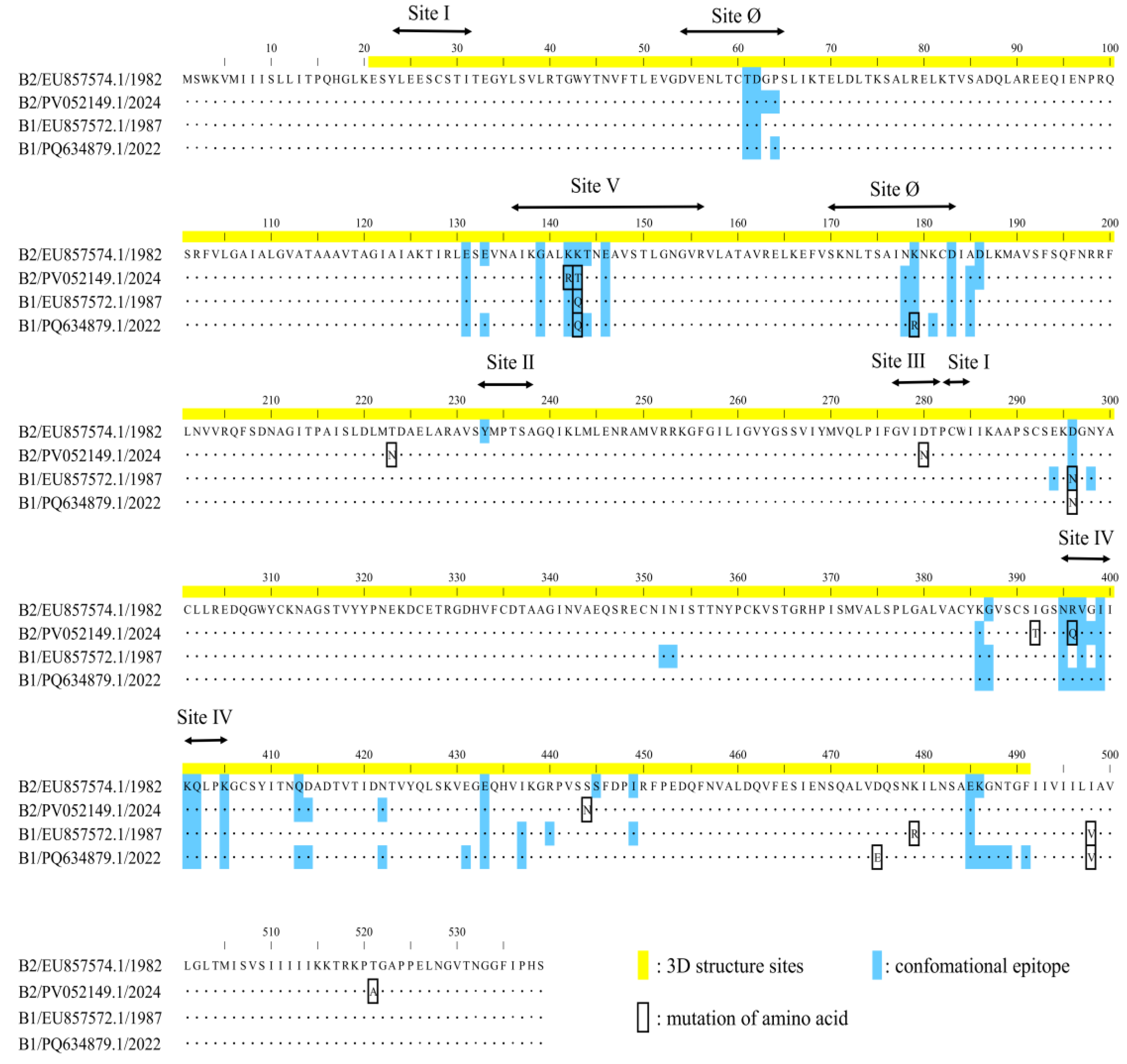

2.7. Structure Modeling

Three-dimensional (3D) structural models of the HMPV F protein were generated for representative strains of B1 (GenBank: EU857572.1, PQ634879.1) and B2 (GenBank: EU857574.1, PV052149.1) using a local installation of ColabFold (LocalColabFold version 1.5.3) [

33]. For each prediction, a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) was first created locally against the uniref30, PDB100, and colabfold_envdb sequence databases. Subsequently, structural models were predicted by utilizing information from known protein structures as templates. To improve physical realism, the resulting structures underwent a refinement process using the AMBER force field. From the five models generated for each protein, we selected the one with the most favorable combination of the predicted local distance difference test (pLDDT), template modeling (TM)-score, and root mean square deviation (RMSD) metrics. The selected structures were visualized using PyMOL version 3.0.3 (

https://www.pymol.org/).

2.8. B-cell Epitope Prediction and Comparative Analysis

We predicted conformational B-cell epitopes on the F protein models of representative strains using four methods: DiscoTope 3.0 (higher confidence: 1.50, recall up to ~30%) [

34], ElliPro (cutoff: 0.5) [

35], SEPPA 3.0 (cutoff: 0.089) [

36], and SEMA (cutoff: 0.76) [

37]. An amino acid residue was defined as a putative B-cell epitope if it was predicted by at least three of the four methods. The identified epitopes were then mapped onto the 3D protein models using PyMOL. To complement the 3D structural analysis, we performed a multiple sequence alignment of the representative strains. Additionally, we visualized amino acid substitutions associated with predicted epitopes and experimentally identified neutralizing antibody binding sites in a linear sequence format. The reference strain for the linear sequence was the oldest strain in the dataset (B2 strain detected in 1982; GenBank accession: EU857574.1).

3. Results

3.1. Time-Scaled Phylogeny and Divergence Time Estimation

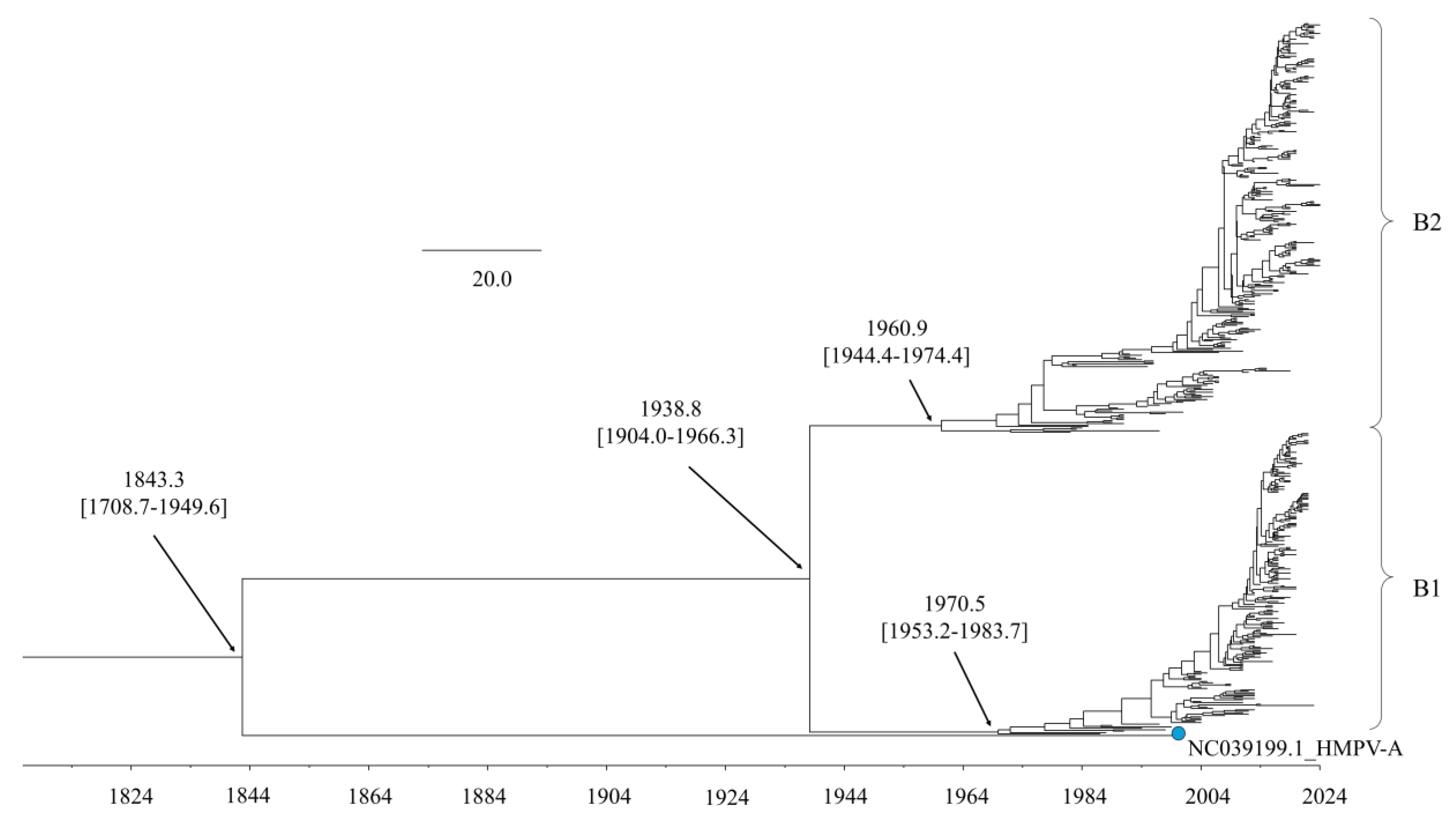

The time-scaled phylogenetic tree, constructed using the BMCMC method, revealed the evolutionary history of the HMPV-B

F gene (

Figure 1). The tree indicated that HMPV-A and HMPV-B diverged from a common ancestor around 1843 (95% Highest Posterior Density [HPD] interval: 1708.7–1949.6). Within HMPV-B, the divergence into the two primary sublineages, B1 and B2, was dated to around 1938 (95% HPD: 1904.0–1966.3). Sublineage B1 subsequently diversified into multiple subclusters starting around 1970. Similarly, sublineage B2 began diversifying into its own distinct subclusters around 1960.

3.2. Historical Changes in Effective Population Size

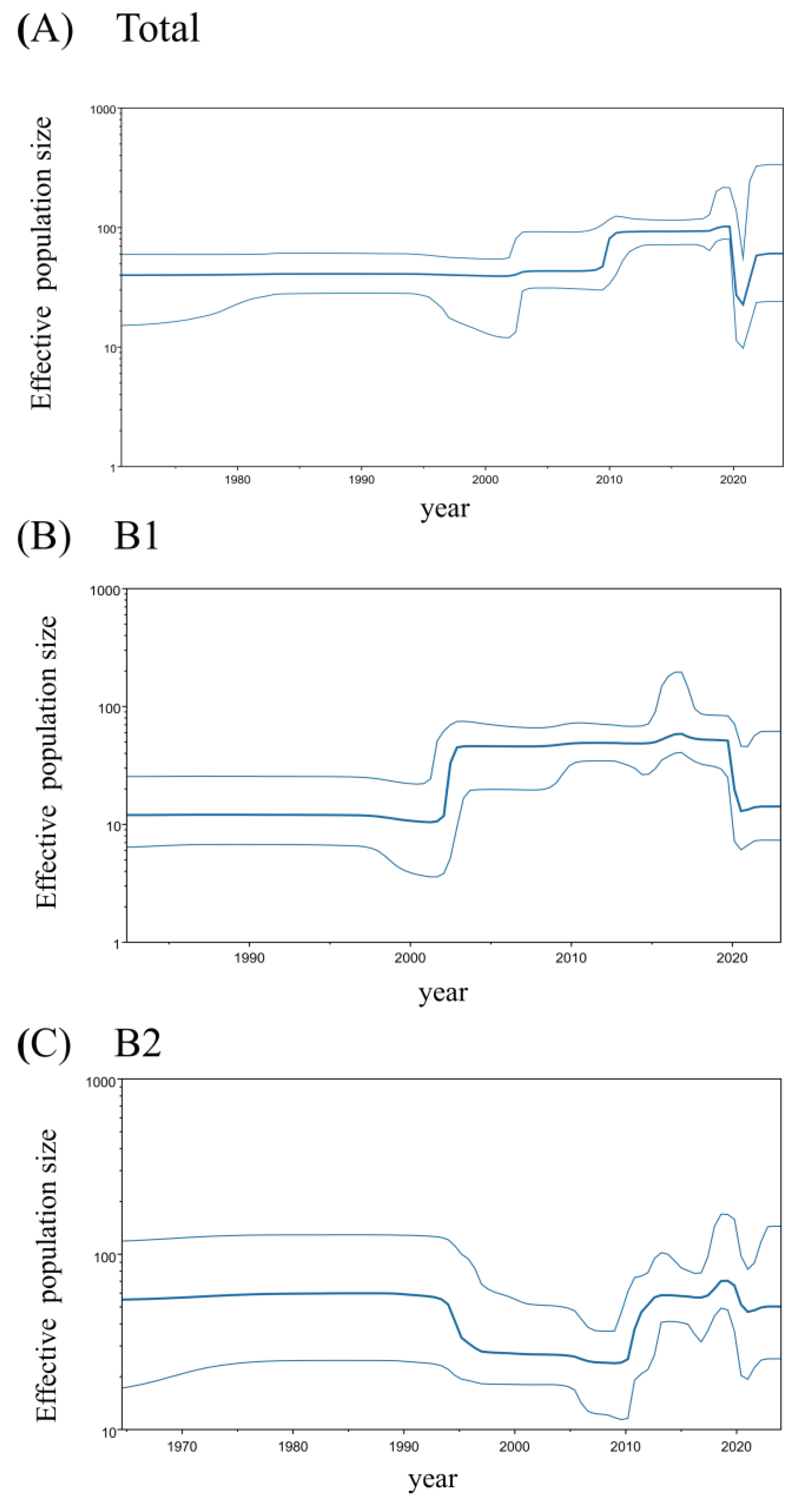

A BSP analysis of the HMPV-B

F gene revealed temporal dynamics in the virus’s effective population size (

Figure 2). The overall effective population size of HMPV-B grew rapidly circa 2010 and then stabilized until 2019, when it sharply declined. A subsequent resurgence was observed around 2021, but it did not reach the previous peak (

Figure 2A). The two sublineages displayed distinct demographic histories. The B1 sublineage showed a pronounced U-shaped pattern, characterized by a sharp rise around 2002, followed by a steep decline around 2020 that reduced its effective population size to a level comparable to that of the early 2000s (

Figure 2B). Conversely, the effective population size of the B2 sublineage experienced a sharp decline around 1995, remained relatively stable, and then expanded sharply again around 2010. After a period of further growth in the late 2010s, the B2 population also decreased around 2020; however, this decline was less pronounced than that observed in B1, leaving the population size at a level similar to that of the early 2010s (

Figure 2C).

To investigate whether lineage-specific amino acid substitutions contributed to the contrasting population dynamics of the B1 (post-expansion) and B2 (post-contraction) lineages, we analyzed sequences from 2004 to 2009, a period during which the effective population sizes of both lineages remained relatively stable. We compared these strains to representative early strains (B1: 1987; B2: 1984) and to recent strains collected from 2020 onwards (B1: 2022; B2: 2024). In the B1 lineage, two amino acid substitutions (D475E and R479K) were identified in strains from the 2004–2009 period (

Supplementary Figure S2). These substitutions persisted in representative strains from 2020 onwards, a period characterized by a sharp decline in effective population size. Similarly, the B2 lineage exhibited one substitution (K143T) common to strains from 2004–2009 (

Supplementary Figure S3). This mutation was maintained in representative strains from 2010 onwards, coinciding with the period of rapid population expansion.

3.3. Estimated Evolutionary Rate

Bayesian analysis estimated the molecular evolutionary rate of the F gene among all HMPV-B strains at 1.01 × 10−3 substitutions/site/year (mean; 95% HPD, 8.73 × 10−4 to 1.15 × 10−3). The evolutionary rate for the B1 sublineage (mean, 9.76 × 10−4; 95% HPD, 8.28 × 10−4 to 1.13 × 10−3 substitutions/site/year) was significantly higher than that observed for the B2 sublineage (mean, 7.35 × 10−4; 95% HPD, 5.79 × 10−4 to 8.93 × 10−4 substitutions/site/year) (p < 0.001).

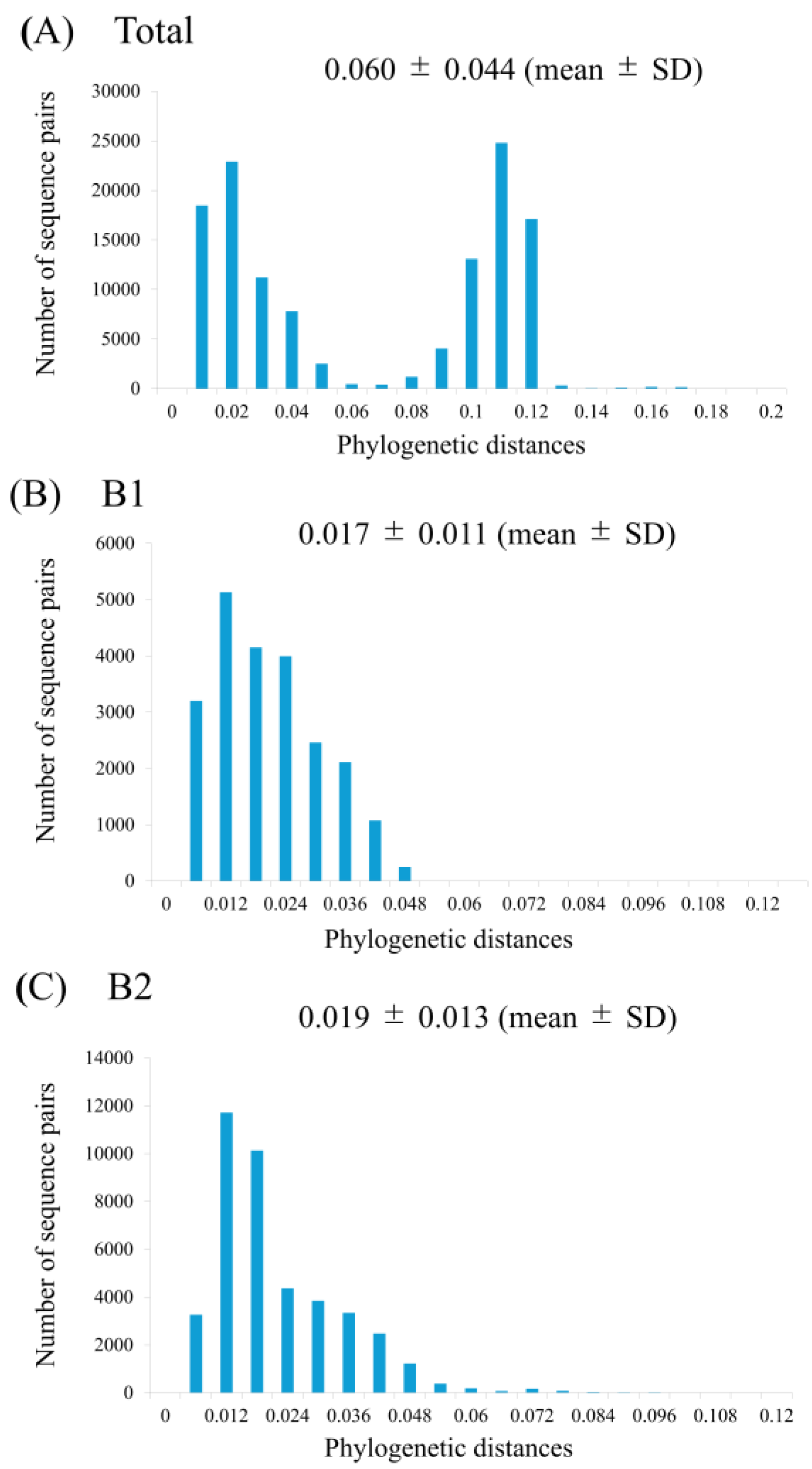

3.4. Phylogenetic Distance

Pairwise patristic distances were calculated from the ML phylogenetic tree to assess the genetic diversity among the analyzed strains. The distribution of these distances for the entire HMPV-B dataset was bimodal, indicating clear divergence between sublineages, with a mean genetic distance of 0.060 (standard deviation [SD], 0.044) (

Figure 3). When analyzed separately, the mean intra-genotype distance was 0.017 (SD, 0.011) for B1 sublineage and 0.019 (SD, 0.013) for B2 sublineage. A statistical comparison confirmed that the genetic diversity within B2 was significantly greater than that within B1 (unpaired t-test,

p < 0.0001).

3.5. Positive and Negative Selection Sites

The selective pressures acting on the HMPV-B F protein were investigated by analyzing its coding sequence for sites under positive and negative selection. While three methods (SLAC, IFEL, and FUBAR) each identified a single, unique codon under positive selection (codons 522, 143, and 482, respectively), no site was consistently identified by more than one method. This lack of consensus suggests limited evidence for strong positive selection acting on any specific site in the F protein. In contrast, strong evidence for purifying (negative) selection was observed. A total of 209 codons, corresponding to approximately 39% of the protein, were consistently identified as being under negative selection by all four methods. These negatively selected sites were distributed throughout the F protein sequence (

Supplementary Figure S4).

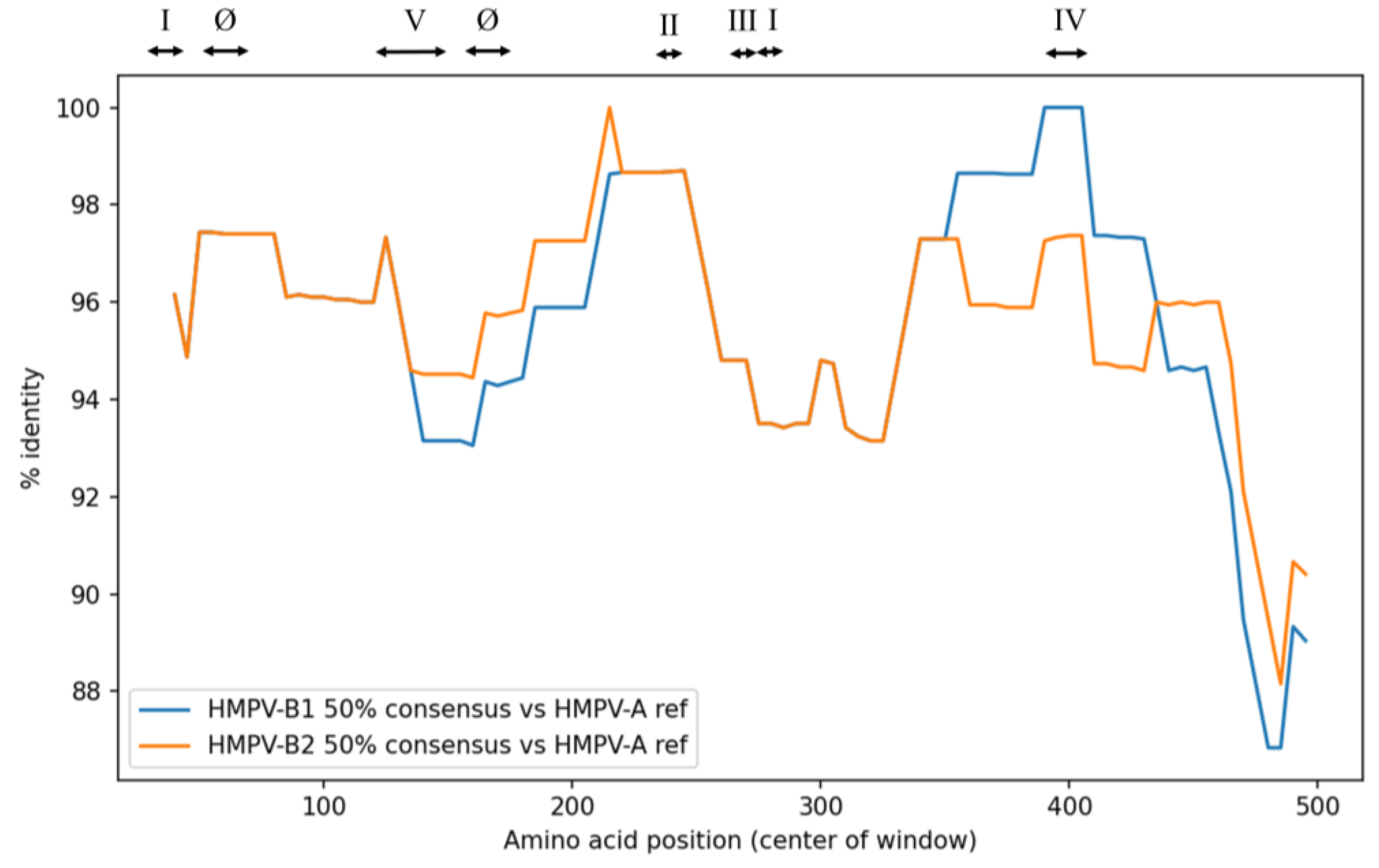

3.7. F Protein Sequence Identity Compared to the HMPV Reference Strain

The sequence identity of the F protein in the analyzed HMPV-B strains was compared to the HMPV reference strain (HMPV-A). Overall, the average sequence identity was high and nearly identical between the two sublineages (B1: 95.6% vs. B2: 95.7%) (

Figure 4,

Supplementary Table S3). High homology with HMPV-A reference strain was also maintained across the neutralizing antibody binding sites (sites Ø and I–V), ranging from 94.6% to 98.2%, with B1 and B2 exhibiting comparable identity values. The greatest difference between sublineages was observed at site IV, where the B1 lineage showed 98.2% identity compared with 96.0% for the B2 lineage.

3.6. Structural Modeling and Conformational Epitope Mapping

To investigate the antigenic properties of the F protein, 3D models were generated for representative HMPV-B strains, and predicted conformational B-cell epitopes were mapped onto their surfaces (

Figure 5A-C). The predicted trimeric structures consistently adopted a "tree-like" conformation, comprising a globular head and a stalk region. The calculated conformational epitopes were predominantly located on the globular head region across all analyzed strains. A high degree of conservation was observed in both the amino acid sequences and the predicted epitope regions between the B1 and B2 sublineages. While the predicted models showed a high degree of structural similarity, specific amino acid substitutions were identified within calculated epitope sites (

Figure 6). Notably, these included substitutions at experimentally identified neutralizing antibody binding sites: K142R and K143T in the 2024 B2 strain (PV052149.1); K143Q in both the 1987 B1 strain (EU857572.1) and the 2022 B1 strain (PQ634879.1); K179R in the 2022 B1 strain; and R396Q in the 2024 B2 strain. Despite these substitutions, the overall surface of the predicted epitopes did not appear to be substantially altered. A comprehensive list of the predicted epitope sites is provided in

Supplementary Table S4.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to elucidate the evolutionary trajectory of the HMPV-B F gene and to assess potential alterations in antigenic sites associated with the accumulation of genetic mutations. Our phylogenetic analysis revealed that HMPV-B diverged into the B1 and B2 sublineages around 1938, after which both lineages continued to diversify into distinct subclusters. The intra-lineage genetic diversity (measured by patristic distances) within both sublineages remained limited. Our selective pressure analysis demonstrated that the F gene was predominantly under purifying selection, with negative selection sites distributed throughout the protein. Despite this overall conservation at the amino acid level, several substitutions were identified, including some located within experimentally identified neutralizing antibody binding sites. However, these substitutions were not predicted to substantially alter the conformational epitope regions. These findings indicate that the HMPV-B F gene maintains a stable antigenicity under strong evolutionary constraint.

The BSP analysis revealed notable fluctuations in the effective population size of HMPV-B. The overall effective population size for the

F gene exhibited a sharp expansion around 2010, a trend that coincides with increased global reporting of respiratory infections [

38]. This expansion may therefore be correlated with enhanced diagnostic capabilities and surveillance efforts, rather than being solely attributable to intrinsic viral factors. In addition, the sharp decline in effective population size around 2019 is likely attributable to decreases in HMPV case detection during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Interestingly, the two sublineages displayed divergent demographic histories. B1 largely followed the overall HMPV-B pattern, whereas B2 exhibited a more irregular history, characterized by an earlier reduction followed by a later expansion. To investigate whether any shared amino acid substitutions were associated with characteristic changes in effective population size, we examined residues that were altered in both sublineages. Although several shared substitutions appeared in strains from the stable period (2004–2009), these changes persisted across later demographic shifts, including the B1 decline around 2020 and the B2 expansion around 2010. Accordingly, no shared amino acid changes were uniquely linked to periods of population contraction or expansion.

The overall evolutionary rate of the

F gene in HMPV-B was estimated at 1.01 × 10⁻³ substitutions/site/year. This rate is higher than previously reported estimates for the

F gene across all HMPV genotypes (7.12 × 10⁻⁴) and also exceeds those of other Pneumoviridae family members, such as RSV-A (7.69 × 10⁻⁴) and RSV-B (7.14 × 10⁻⁴) [

39,

40,

41]. Moreover, it also surpasses the evolutionary rates reported for the

F genes of other RNA viruses, such as human parainfluenza virus type 1 (HPIV1; 8.50 × 10⁻⁴), HPIV2 (4.20 × 10⁻⁴), HPIV3 (9.40 × 10⁻⁴), HPIV4 (4.41 × 10⁻⁴), and mumps virus (5.0 × 10⁻⁴) [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. In contrast, amino acid variation in the F protein remained limited, indicating that increases in nucleotide-level diversity were not reflected at the protein level. Selective pressure analysis supported this observation, revealing pervasive purifying selection and no consistent evidence of positive selection across methods. As a consequence of this predominance of purifying selection, most substitutions were synonymous, resulting in broad conservation of the HMPV-B F protein despite its relatively high evolutionary rate. Similarly, although the evolutionary rate of the HMPV-B2

F gene was significantly higher than that of HMPV-B1, this higher rate did not translate into greater amino acid diversity between the two sublineages.

HMPV and RSV cause clinically similar respiratory illnesses and affect overlapping patient populations. As with RSV, the development of vaccines and prophylactic antibody preparations for HMPV is advancing, with particular focus on targeting neutralizing antibody binding sites on the F protein (sites Ø and I–V). These antigenic sites are of special interest because several correspond to cross-reactive neutralizing antibody epitopes shared between HMPV and RSV [

14,

15,

16,

29]. Because amino acid substitutions can alter antigenicity, we examined whether substitutions occurring within these neutralizing antibody binding sites, as well as across strains of different sublineages and detection years, could modify conformational epitope structures using

in silico analysis. Our analysis showed that the predicted conformational epitope regions were highly conserved across all representative HMPV-B strains. Although several amino acid substitutions were observed within neutralizing antibody binding sites (e.g., sites III, IV, and V), these changes were not predicted to substantially alter the three-dimensional epitope architecture. Additionally, sequence identity across all 500 strains showed uniformly high amino acid conservation, with no major differences between the B1 and B2 sublineages. These results indicate that amino acid variation across the broader dataset was limited, consistent with the findings obtained from representative strains. These observations support the feasibility of developing vaccines and prophylactic antibody preparations targeting the F protein. Moreover, because most individuals are infected with HMPV by five years of age [

1], the high structural conservation of these epitopes suggests that recurrent epidemics are more likely driven by waning host immunity than by viral antigenic drift. Consequently, preventive strategies targeting the conserved F protein are likely to remain effective in the long term. In contrast, the high degree of conservation does not necessarily confer an advantage for vaccine or antibody development. For instance, residues Asn57 and Asn172 at site Ø form the core of the glycan shield [

17], and no mutations were detected at these positions in our representative strains. The preservation of this glycan shield suggests that developing antibody preparations targeting the apical region—an approach effective for RSV—may remain challenging for HMPV.

Although our consensus analysis did not identify strong evidence for positive selection, the IFEL method individually flagged codon 143 as a potential site. Notably, amino acid substitutions at this position were observed in multiple strains compared to the 1982 B2 strain. Although predicted structural epitopes containing this site (codon 143) appeared conserved

in silico, it is important to distinguish between predicted structural conservation and actual functional impact [

47]. A single substitution (e.g., K143T/Q) could alter antigenicity by affecting the binding affinity of neutralizing antibodies, even if the overall three-dimensional structure is maintained. Furthermore, the potential impact of mutations at this site on virus-host membrane fusion remains unknown.

This study has several limitations. First, the use of publicly available sequences introduces potential sampling bias, as regions or periods with stronger surveillance are more likely to be represented. Second, our consensus-based epitope analysis did not identify site III, a known neutralizing antibody binding site comparable in importance to site IV. To enhance reliability, we defined residues as epitopes only when at least three of four prediction algorithms supported them. Although this stringent criterion reduces false-positive predictions, it likely resulted in the omission of certain antigenic sites, including site III. Finally, the present study lacks experimental validation. While epitope prediction and structural modeling provide useful insights, determining the quantitative functional impact of amino acid substitutions ultimately requires in vitro assays such as neutralization and membrane fusion studies, which remain important areas for future investigation.

5. Conclusions

Our analyses show that the HMPV-B F gene evolves under strong purifying selection, resulting in limited amino acid diversity between the B1 and B2 sublineages. Neutralizing antibody binding regions remained highly conserved, and substitutions within these sites were not predicted to alter epitope architecture. These findings indicate that the antigenic structure of the F protein is stable across decades, supporting its suitability as a target for antibody-based interventions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Figure S1: Temporal distribution of HMPV-B strains by collection year; Figure S2: Amino acid sequence alignment of representative F proteins from the HMPV-B1 sublineage; Figure S3: Sequence alignment of representative HMPV-B2 strains; Figure S4: Negative selection sites in HMPV-B F protein; Table S1: List of HMPV-B strains and associated metadata used in this study; Table S2: Parameter settings for the BMCMC analyses; Table S3: Pairwise sequence identity of HMPV-B F proteins compared to the HMPV-A reference strain; Table S4: Predicted conformational B-cell epitopes on the HMPV-B F protein.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.Shi., A.R., and H.K.; methodology, T.Shi., F.M., M.S., R.K., T.Su., and H.K.; formal analysis, T.Shi.; visualization, T.Shi. and F.M.; writing—original draft preparation, T.S.; writing—review and editing, T.Shi., F.M., T.Sa., A.R., and H.K.; visualization, T.Shi.; supervision, K.S., H.I., A.R., and H.K.; funding acquisition, A.R. and H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (grant number, JP25fk0108661).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in association with the present study.

References

- van den Hoogen, B.G.; de Jong, J.C.; Groen, J.; Kuiken, T.; de Groot, R.; Fouchier, R.A.; Osterhaus, A.D. A newly discovered human pneumovirus isolated from young children with respiratory tract disease. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, A.; Manoha, C.; Bour, J.B.; Abbas, R.; Fournel, I.; Tiv, M.; Pothier, P.; Astruc, K.; Aho-Glélé, L.S. Human metapneumovirus in patients hospitalized with acute respiratory infections: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Virol. 2016, 81, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Rodriguez, C.; Banos-Lara, M.D.R. HMPV in Immunocompromised Patients: Frequency and Severity in Pediatric Oncology Patients. Pathogens 2020, 9, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuerman, O.; Barkai, G.; Mandelboim, M.; Mishali, H.; Chodick, G.; Levy, I. Human metapneumovirus (hMPV) infection in immunocompromised children. J. Clin. Virol. 2016, 83, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Hoogen, B.G.; Herfst, S.; Sprong, L.; Cane, P.A.; Forleo-Neto, E.; de Swart, R.L.; Osterhaus, A.D.; Fouchier, R.A. Antigenic and genetic variability of human metapneumoviruses. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biacchesi, S.; Skiadopoulos, M.H.; Boivin, G.; Hanson, C.T.; Murphy, B.R.; Collins, P.L.; Buchholz, U.J. Genetic diversity between human metapneumovirus subgroups. Virology 2003, 315, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastien, N.; Normand, S.; Taylor, T.; Ward, D.; Peret, T.C.; Boivin, G.; Anderson, L.J.; Li, Y. Sequence analysis of the N, P, M and F genes of Canadian human metapneumovirus strains. Virus Res. 2003, 93, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huck, B.; Scharf, G.; Neumann-Haefelin, D.; Puppe, W.; Weigl, J.; Falcone, V. Novel human metapneumovirus sublineage. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nao, N.; Saikusa, M.; Sato, K.; Sekizuka, T.; Usuku, S.; Tanaka, N.; Nishimura, H.; Takeda, M. Recent Molecular Evolution of Human Metapneumovirus (HMPV): Subdivision of HMPV A2b Strains. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagušić, M.; Slović, A.; Ljubin-Sternak, S.; Mlinarić-Galinović, G.; Forčić, D. Genetic diversity of human metapneumovirus in hospitalized children with acute respiratory infections in Croatia. J. Med. Virol. 2017, 89, 1885–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, K.; Li, Y.; Chen, D.; Tan, Y.; Liang, L.; Liu, M.; Liang, J.; An, S.; et al. Epidemiology, genetic characteristics, and association with meteorological factors of human metapneumovirus infection in children in southern China: A 10-year retrospective study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 137, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley, D.A.; Smith, D.W.; Barr, I.; Moore, H.C.; Nicol, M.; Blyth, C.C. Determinants of respiratory syncytial virus and human metapneumovirus transmission. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2025, 38, e0020324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazur, N.I.; Terstappen, J.; Baral, R.; Bardají, A.; Beutels, P.; Buchholz, U.J.; Cohen, C.; Crowe, J.E., Jr.; Cutland, C.L.; Eckert, L.; et al. Respiratory syncytial virus prevention within reach: The vaccine and monoclonal antibody landscape. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, e2–e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Diaz, D.; Mousa, J.J. Antibody Epitopes of Pneumovirus Fusion Proteins. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battles, M.B.; Más, V.; Olmedillas, E.; Cano, O.; Vázquez, M.; Rodríguez, L.; Melero, J.A.; McLellan, J.S. Structure and Immunogenicity of Pre-Fusion-Stabilized Human Metapneumovirus F Glycoprotein. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rush, S.A.; Brar, G.; Hsieh, C.L.; Chautard, E.; Rainho-Tomko, J.N.; Slade, C.D.; Bricault, C.A.; Kume, A.; Kearns, J.; Groppo, R.; et al. Characterization of Prefusion-F-Specific Antibodies Elicited by Natural Infection with Human Metapneumovirus. Cell Rep. 2022, 40, 111399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Li, L.; Liu, L.; Zhang, T.; Sun, M. Neutralising Antibodies against Human Metapneumovirus. Lancet Microbe 2023, 4, e732–e744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadfield, J.; Megill, C.; Bell, S.M.; Huddleston, J.; Potter, B.; Callender, C.; Sagulenko, P.; Bedford, T.; Neher, R.A. Nextstrain: Real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics. 2018, 34((23)), 4121–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, F.; Madhusoodanan, N.; Lee, J.; Eusebi, A.; Niewielska, A.; Tivey, A.R.N.; Lopez, R.; Butcher, S. The EMBL-EBI Job Dispatcher Sequence Analysis Tools Framework in 2024. Nucleic Acids Research 2024, 52((W1)), W521–W525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouckaert, R.; Vaughan, T.G.; Barido-Sottani, J.; Duchêne, S.; Fourment, M.; Gavryushkina, A.; Heled, J.; Jones, G.; Kühnert, D.; De Maio, N.; et al. BEAST 2.5: An Advanced Software Platform for Bayesian Evolutionary Analysis. PLoS Computational Biology 2019, 15, e1006650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darriba, D.; Taboada, G.L.; Doallo, R.; Posada, D. jModelTest 2: More Models, New Heuristics, and Parallel Computing. Nature Methods 2012, 9, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rambaut, A.; Drummond, A.J.; Xie, D.; Baele, G.; Suchard, M.A. Posterior Summarization in Bayesian Phylogenetics Using Tracer 1.7. Systematic Biology 2018, 67, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the Freely Available Easy-to-Use Software ‘EZR’ for Medical Statistics. Bone Marrow Transplan-tation 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourment, M.; Gibbs, M.J. PATRISTIC: A Program for Calculating Patristic Distances and Graphically Comparing the Components of Genetic Change. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2006, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, S.; Shank, S.D.; Spielman, S.J.; Li, M.; Muse, S.V.; Kosakovsky Pond, S.L. Datamonkey 2.0: A Modern Web Application for Characterizing Selective and Other Evolutionary Processes. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2018, 35((3)), 773–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Krause, J.C.; Leser, G.P.; Cox, R.G.; Lamb, R.A.; Williams, J.V.; Crowe, J.E., Jr.; Jardetzky, T.S. Structure of the Human Metapneumovirus Fusion Protein with Neutralizing Antibody Identifies a Pneumovirus Antigenic Site. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012, 19, 461–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Huang, J.; Rush, S.A.; Murray, J.; Gingerich, A.D.; Royer, F.; Hsieh, C.L.; Tripp, R.A.; McLellan, J.S.; Mousa, J.J. Structural Basis for Ultrapotent Antibody-Mediated Neutralization of Human Metapneumovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2203326119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corti, D.; Bianchi, S.; Vanzetta, F.; Minola, A.; Perez, L.; Agatic, G.; Guarino, B.; Silacci, C.; Marcandalli, J.; Marsland, B.J.; et al. Cross-Neutralization of Four Paramyxoviruses by a Human Monoclonal Antibody. Nature 2013, 501, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Tang, A.; Cox, K.S.; Wen, Z.; Callahan, C.; Sullivan, N.L.; Nahas, D.D.; Cosmi, S.; Galli, J.D.; Minnier, M.; et al. Characterization of Potent RSV Neutralizing Antibodies Isolated from Human Memory B Cells and Identification of Diverse RSV/hMPV Cross-Neutralizing Epitopes. mAbs 2019, 11, 1415–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Más, V.; Rodríguez, L.; Olmedillas, E.; Cano, O.; Palomo, C.; Terrón, M.C.; Luque, D.; Melero, J.A.; McLellan, J.S. Engineering, Structure and Immunogenicity of the Human Metapneumovirus F Protein in the Postfusion Conformation. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, X.; Fridman, A.; Zhang, L.; Pristatsky, P.; Durr, E.; Minnier, M.; Tang, A.; Cox, K.S.; Wen, Z.; Moore, R.; et al. Profiling of hMPV F-Specific Antibodies Isolated from Human Memory B Cells. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirdita, M.; Schütze, K.; Moriwaki, Y.; Heo, L.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Steinegger, M. ColabFold: Making Protein Folding Accessible to All. Nature Methods 2022, 19, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Høie, M.H.; Gade, F.S.; Johansen, J.M.; Würtzen, C.; Winther, O.; Nielsen, M.; Marcatili, P. DiscoTope-3.0: Improved B-cell epitope prediction using inverse folding latent representations. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1322712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomarenko, J.; Bui, H.H.; Li, W.; Fusseder, N.; Bourne, P.E.; Sette, A.; Peters, B. ElliPro: A new structure-based tool for the prediction of antibody epitopes. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, L.; Yan, D.; Mao, T.; Tang, K.; Qiu, T.; Cao, Z. SEPPA 3.0-enhanced spatial epitope prediction enabling glycoprotein antigens. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W388–W394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashkova, T.I.; Umerenkov, D.; Salnikov, M.; Strashnov, P.V.; Konstantinova, A.V.; Lebed, I.; Shcherbinin, D.N.; Asatryan, M.N.; Kardymon, O.L.; Ivanisenko, N.V. SEMA: Antigen B-cell conformational epitope prediction using deep transfer learning. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 960985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2016 Lower Respiratory Infections Collaborators. Estimates of the Global, Regional, and National Morbidity, Mortality, and Aetiologies of Lower Respiratory Infections in 195 Countries, 1990–2016: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2018, 18((11)), 1191–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.F.; Wang, C.K.; Tollefson, S.J.; Piyaratna, R.; Lintao, L.D.; Chu, M.; Liem, A.; Mark, M.; Spaete, R.R.; Crowe, J.E., Jr.; et al. Genetic diversity and evolution of human metapneumovirus fusion protein over twenty years. Virol J. 2009, 6, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, M.; Tsukagoshi, H.; Sada, M.; Sunagawa, S.; Shirai, T.; Okayama, K.; Sugai, T.; Tsugawa, T.; Hayashi, Y.; Ryo, A.; et al. Detailed Evolutionary Analyses of the F Gene in the Respiratory Syncytial Virus Subgroup A. Viruses. 2021, 13((12)), 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, H.; Nagasawa, K.; Kimura, R.; Tsukagoshi, H.; Matsushima, Y.; Fujita, K.; Hirano, E.; Ishiwada, N.; Misaki, T.; Oishi, K.; et al. Molecular evolution of the fusion protein (F) gene in human respiratory syncytial virus subgroup B. Infect Genet Evol. 2017, 52, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T.; Akagawa, M.; Kimura, R.; Sada, M.; Shirai, T.; Okayama, K.; Hayashi, Y.; Kondo, M.; Takeda, M.; Ryo, A.; et al. Molecular Evolutionary Analyses of the Fusion Protein Gene in Human Respirovirus 1. Virus Research 2023, 333, 199142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirai, T.; Mizukoshi, F.; Kimura, R.; Matsuoka, R.; Sada, M.; Shirato, K.; Ishii, H.; Ryo, A.; Kimura, H. Molecular Evolution of the Fusion (F) Genes in Human Parainfluenza Virus Type 2. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aso, J.; Kimura, H.; Ishii, H.; Saraya, T.; Kurai, D.; Matsushima, Y.; Nagasawa, K.; Ryo, A.; Takizawa, H. Molecular Evolution of the Fusion Protein (F) Gene in Human Respirovirus 3. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 10, 3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizukoshi, F.; Kimura, H.; Sugimoto, S.; Kimura, R.; Nagasawa, N.; Hayashi, Y.; Hashimoto, K.; Hosoya, M.; Shirato, K.; Ryo, A. Molecular Evolutionary Analyses of the Fusion Genes in Human Parainfluenza Virus Type 4. Microorganisms 2024, 12((8)), 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, A.; Rivailler, P.; Zhu, Z.; Deng, X.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, F.; Sun, Z.; He, J.; Si, Y.; et al. Evolutionary Analysis of Mumps Viruses of Genotype F Collected in Mainland China in 2001–2015. Scientific Reports 2017, 7((1)), 17144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, P.L.; Karron, R.A. Respiratory Syncytial Virus and Metapneumovirus. In Fields Virology, 6th ed.; Knipe, D.M., Howley, P., Eds.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 1086–1123. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |