Submitted:

22 December 2025

Posted:

24 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. D-Optimal Design of Experiments Method

2.2. Polynomial Regression

2.3. Radial Basis Function

2.4. Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm

3. Screening Methodology

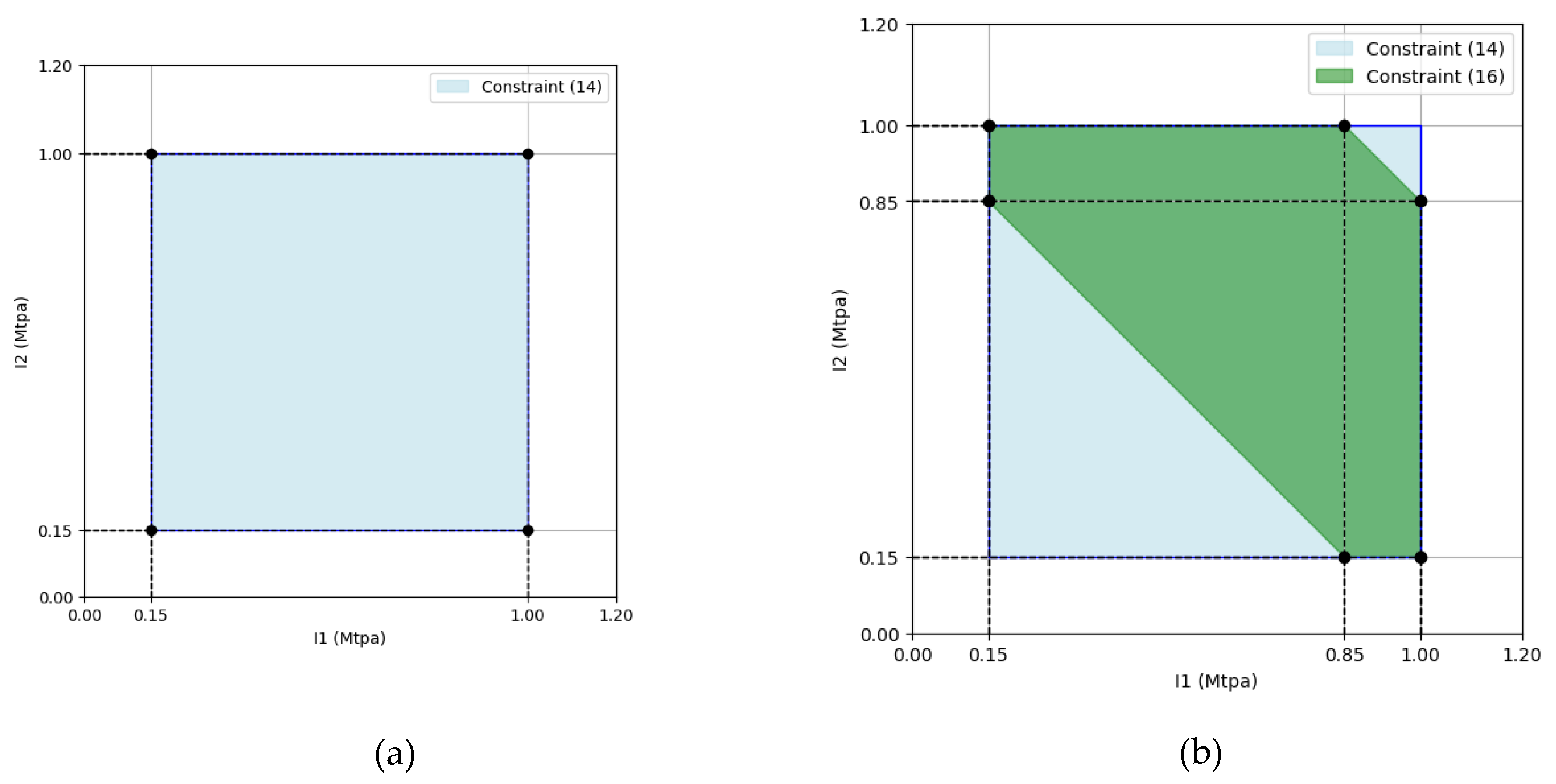

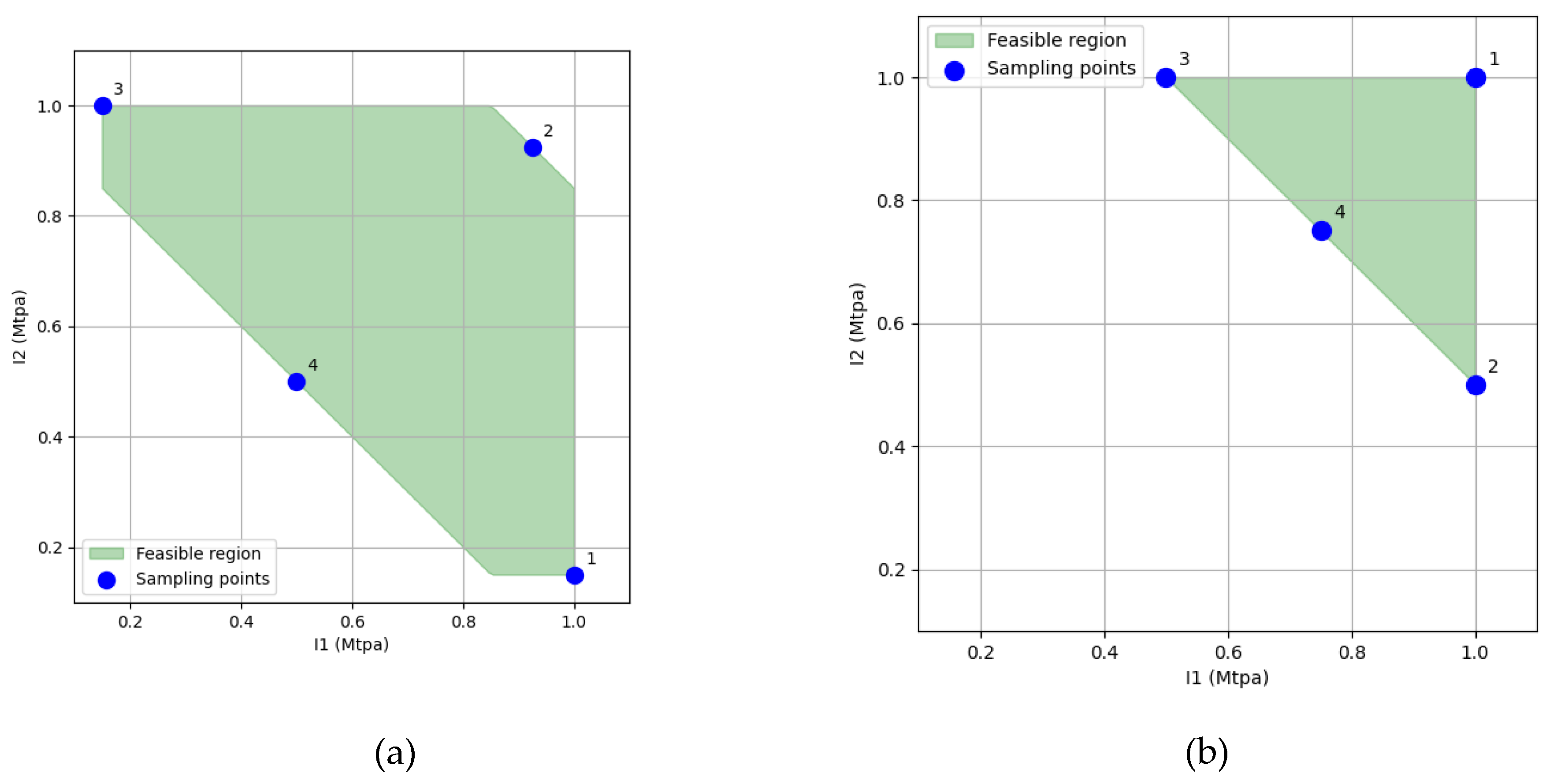

3.1. Problem Definition and DoE Sampling

3.2. Optimization Method

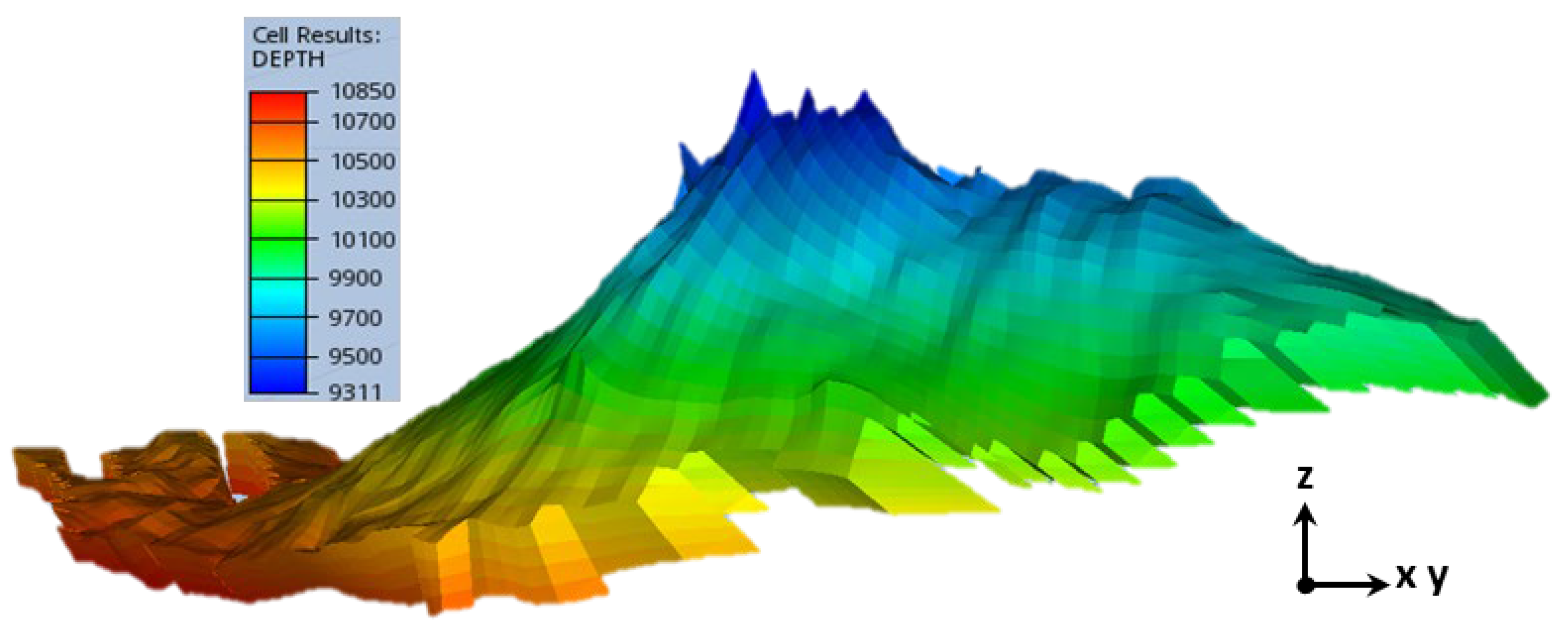

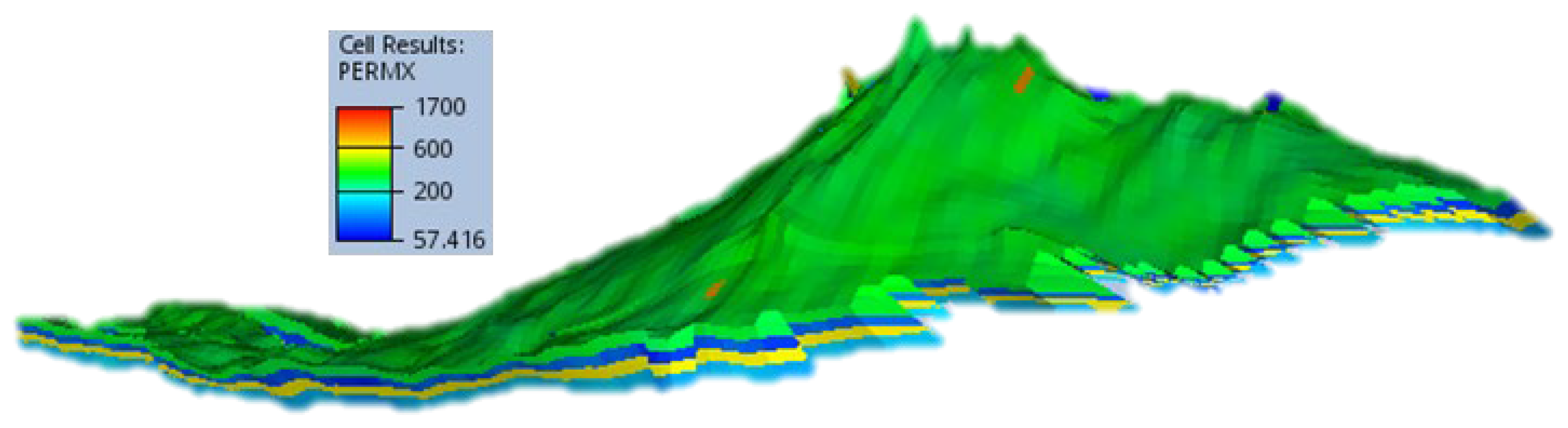

4. Case Studies

5. Results & Discussion

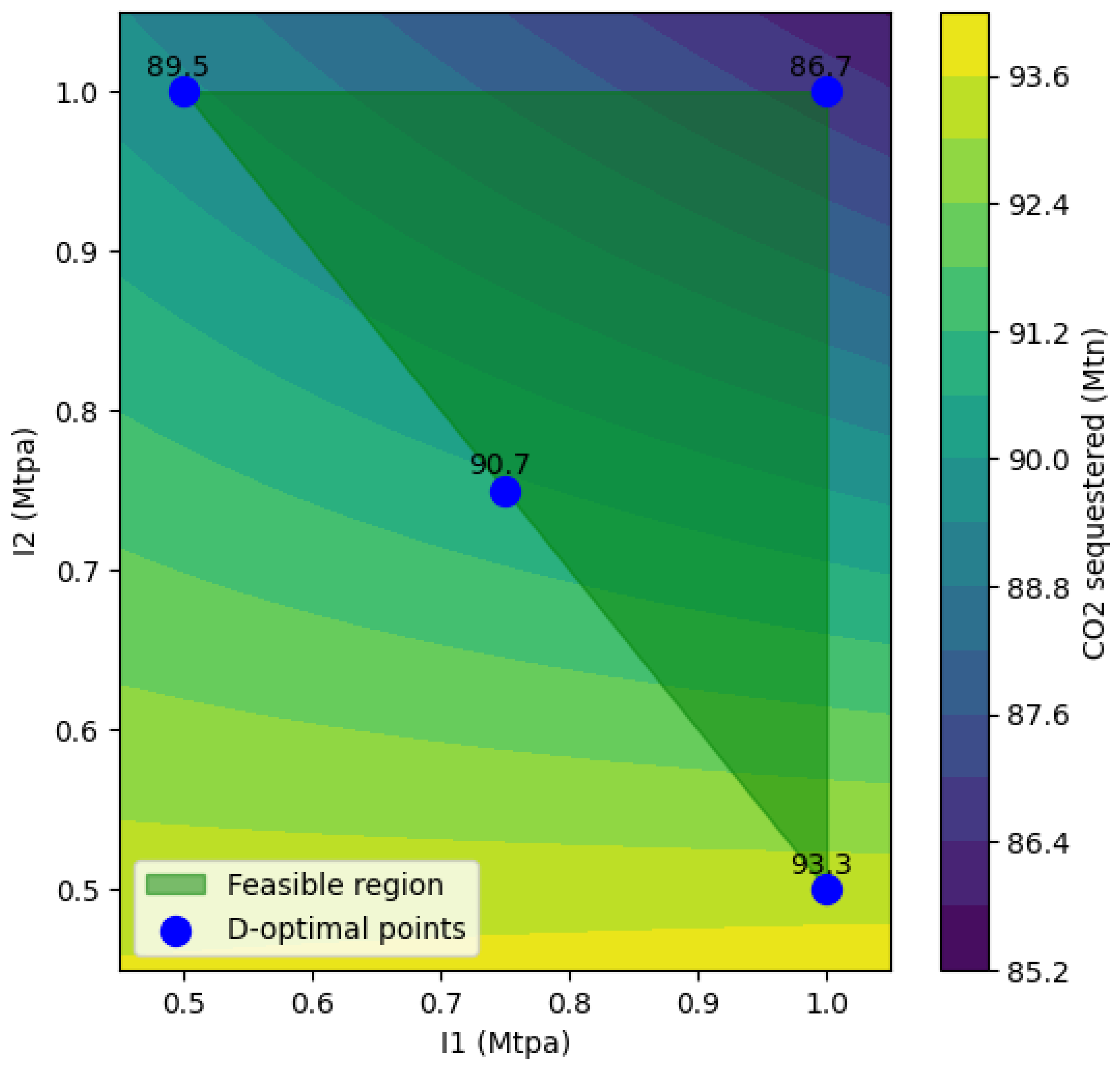

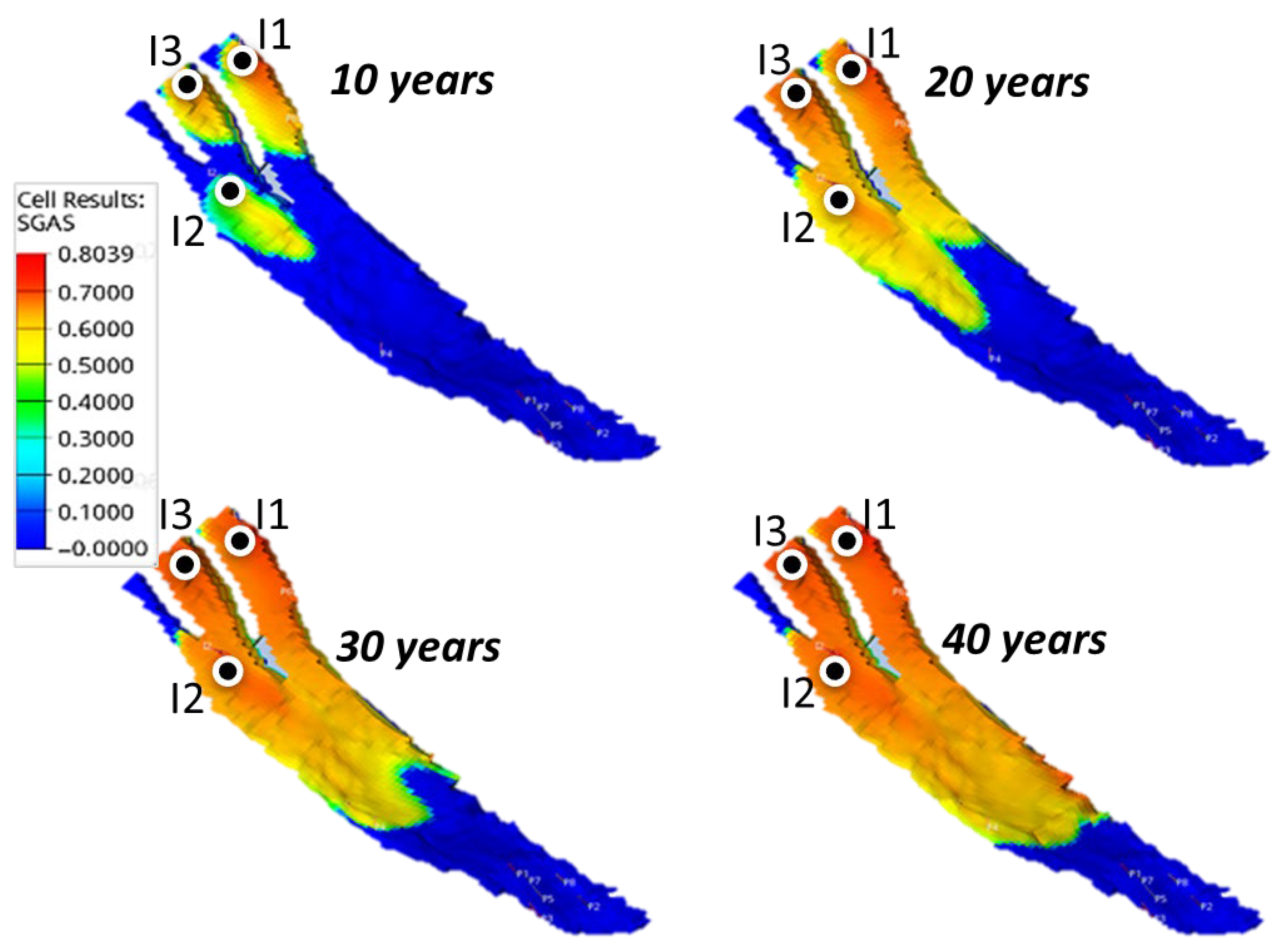

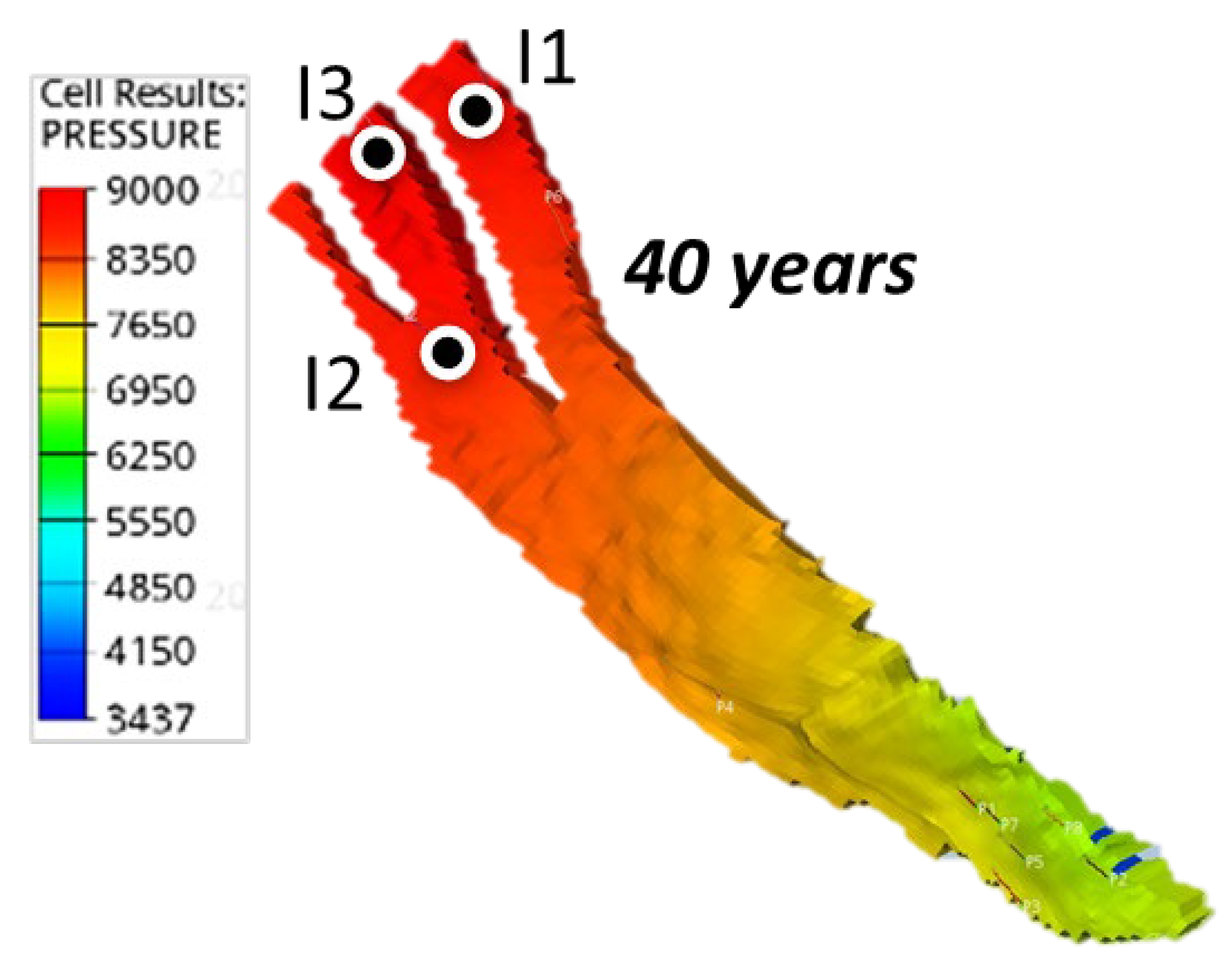

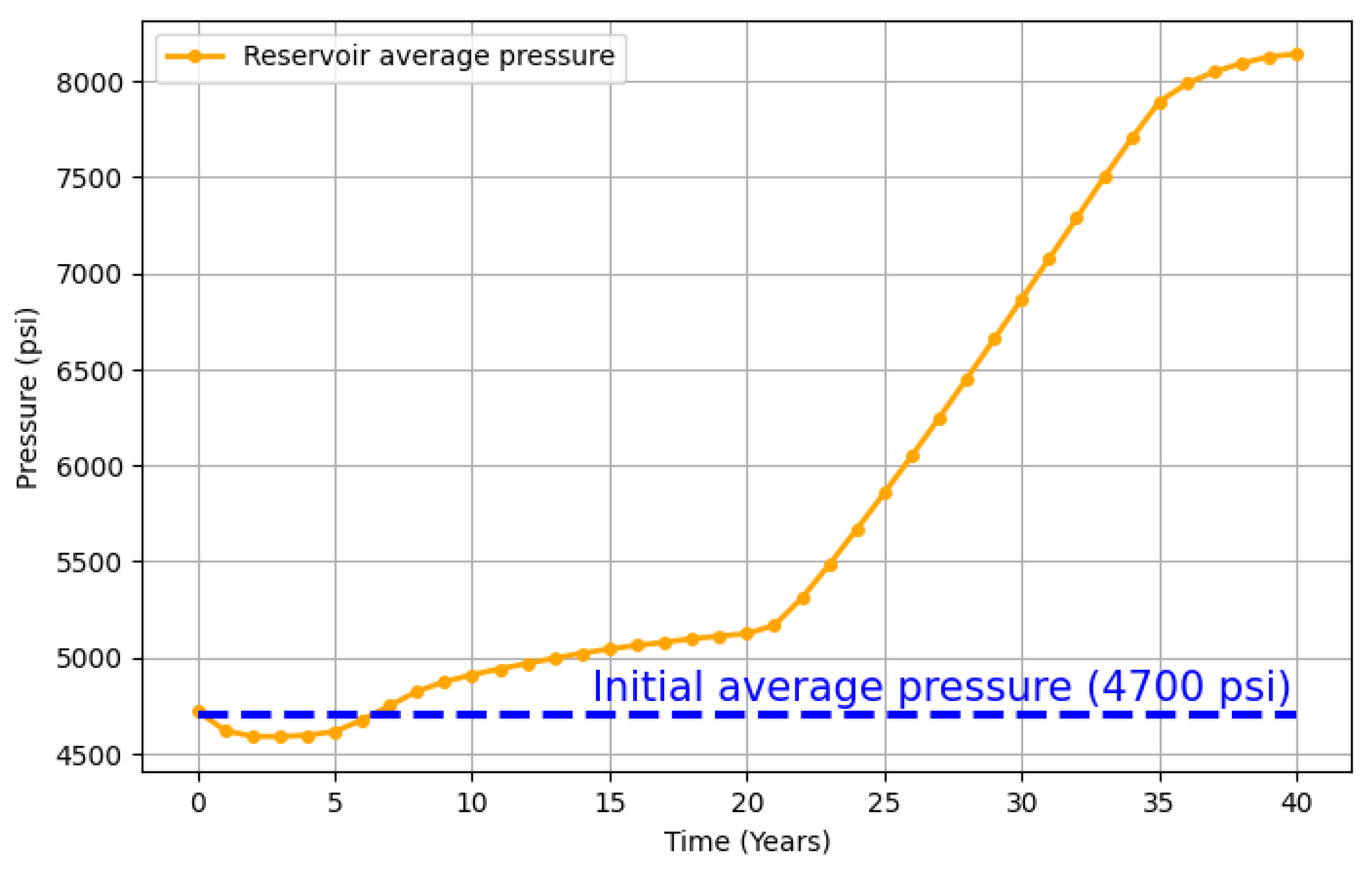

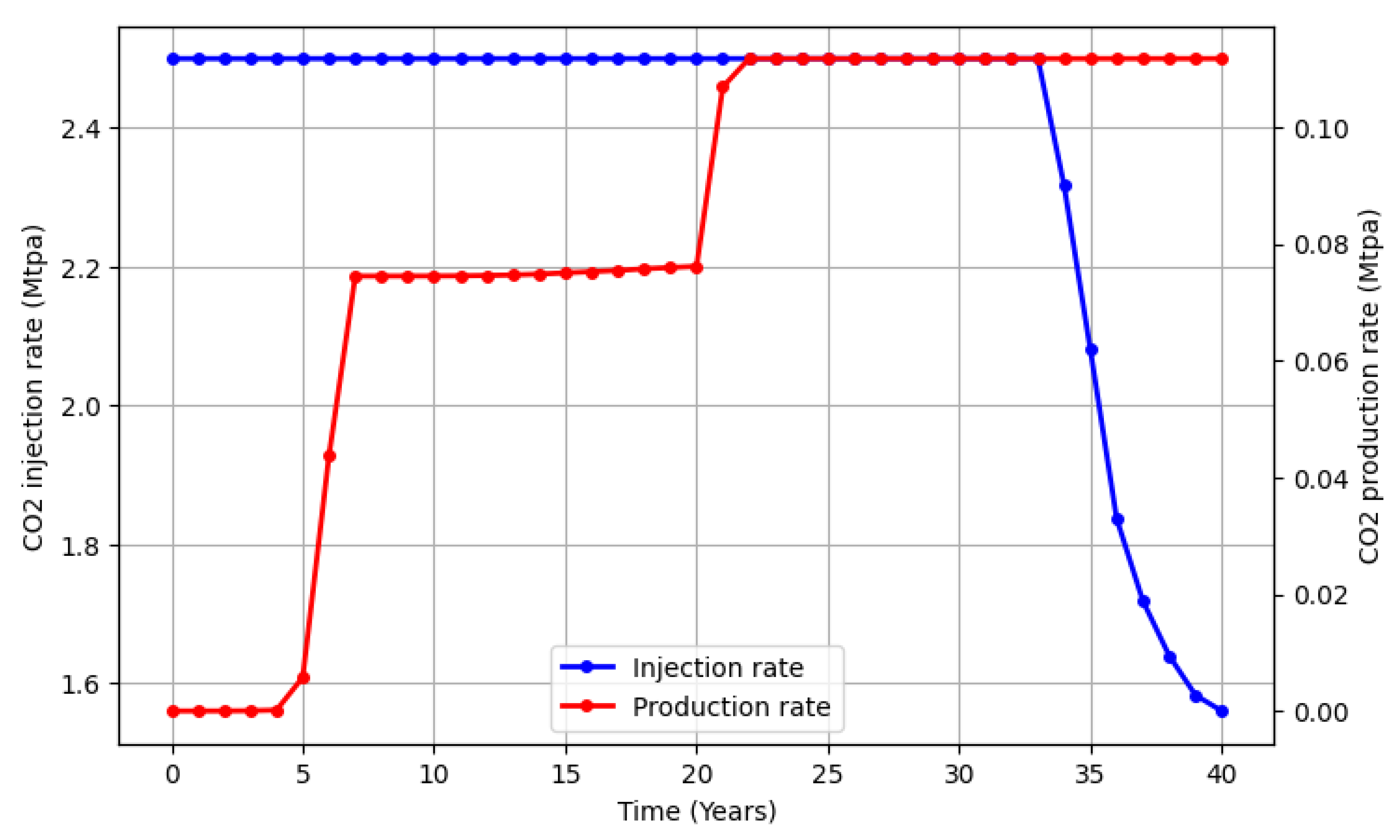

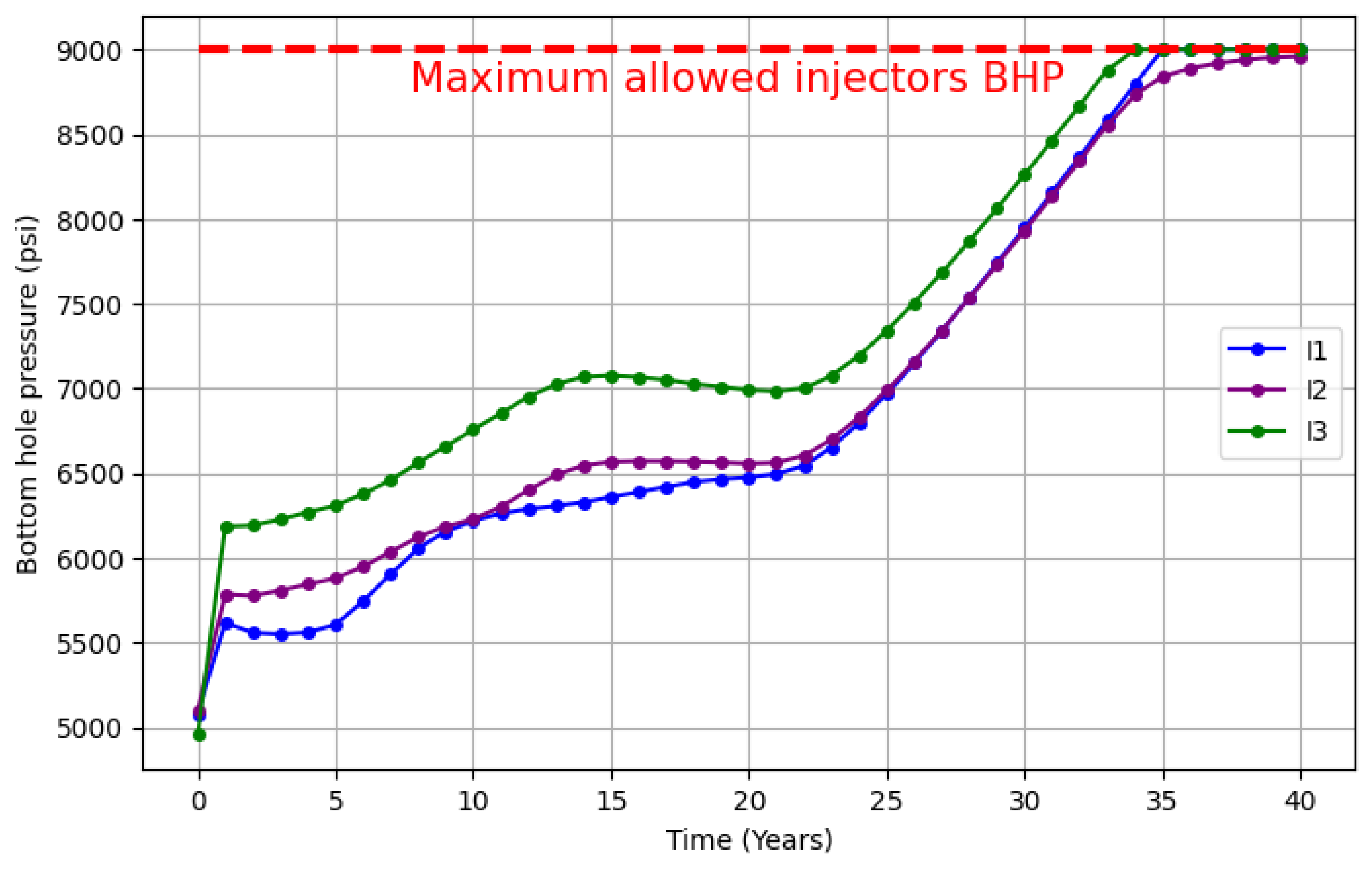

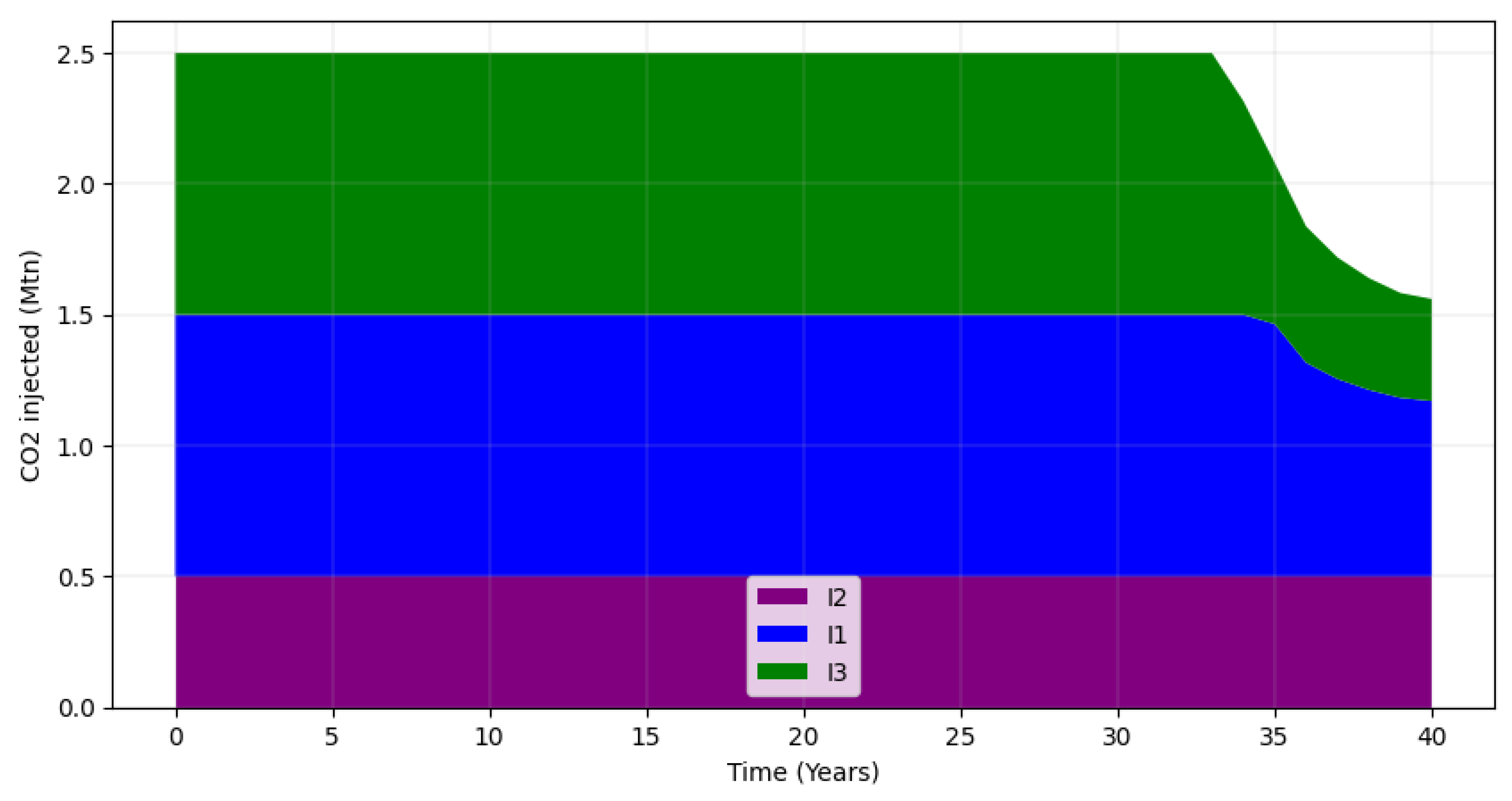

5.1. Case 1: Total Field CO2 Sequestration Target 80 Mtn with Three Injection Wells

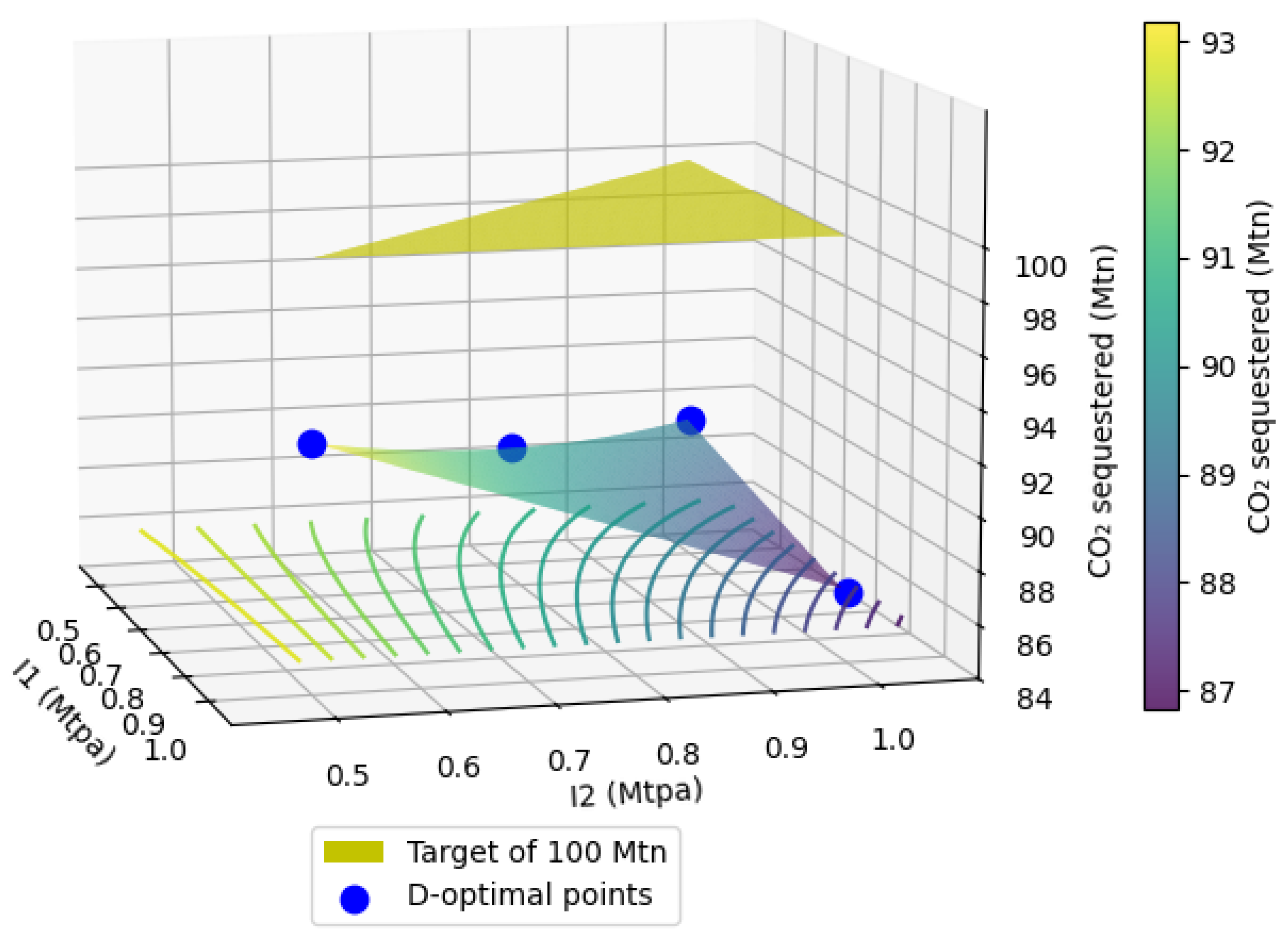

5.2. Case 2: Total Field CO2 Sequestration Target 100 Mtn with Three Injection Wells

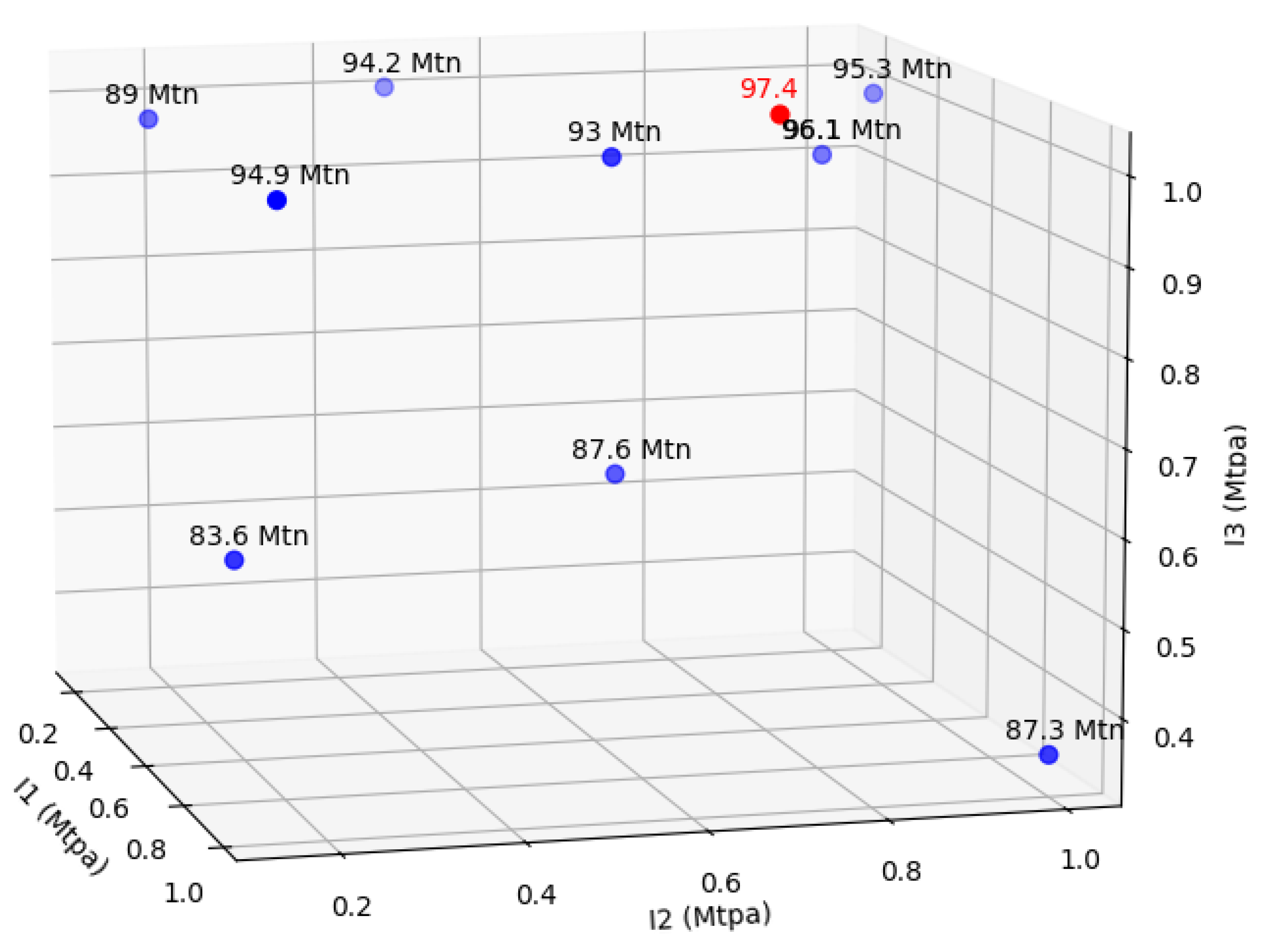

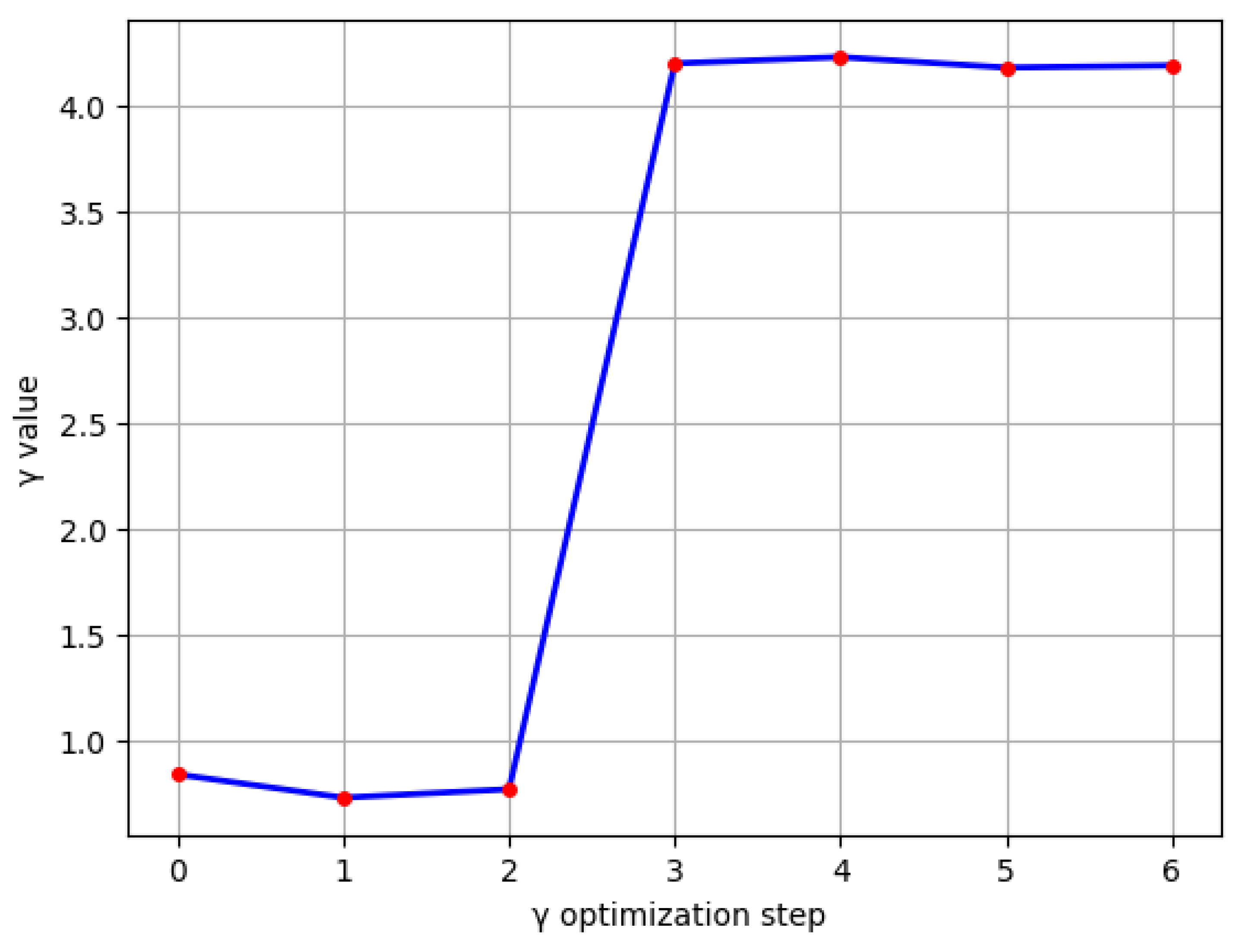

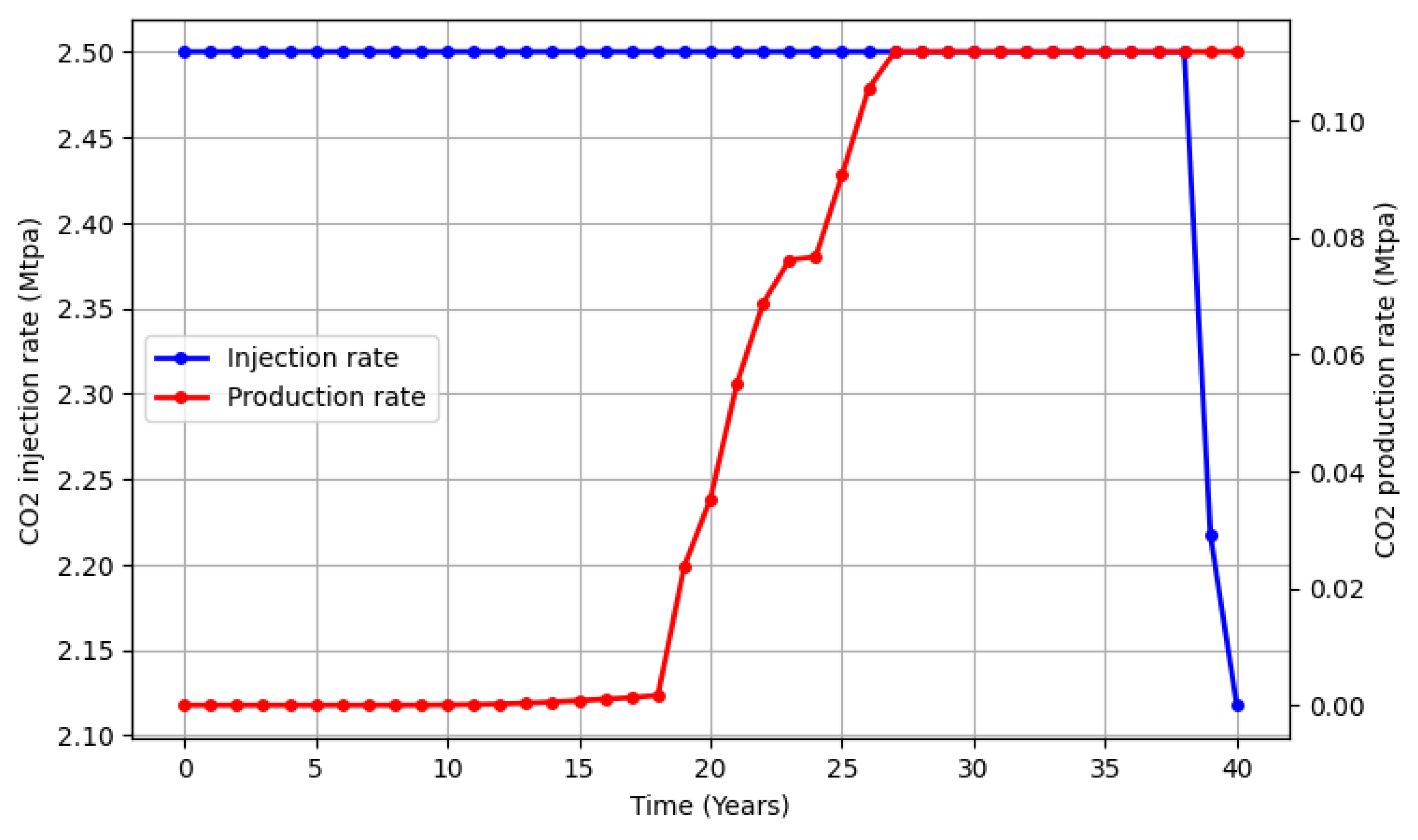

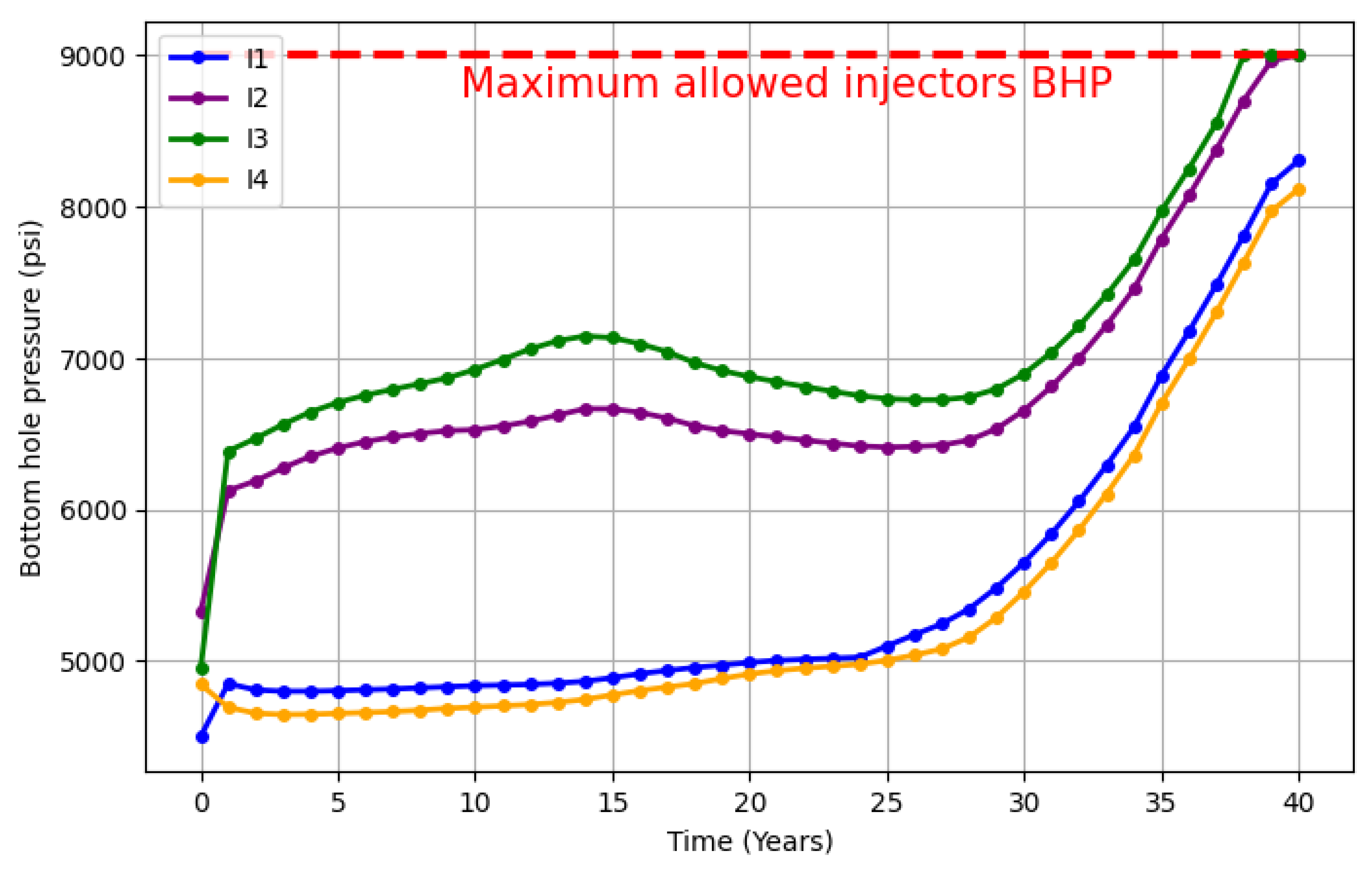

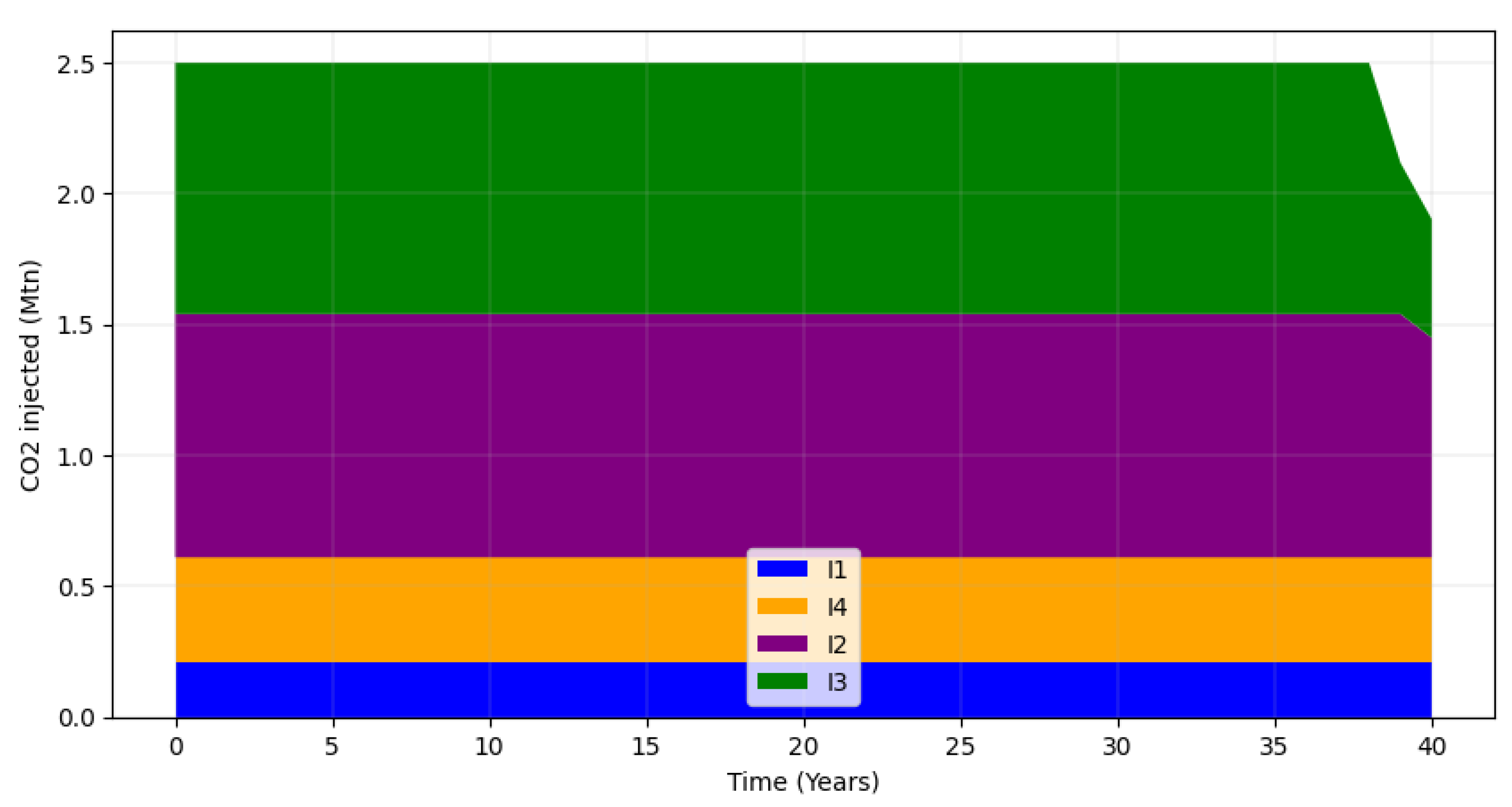

5.3. Case 3: Total Field CO2 Sequestration Target 100 Mtn with Four Injection Wells

5.4. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Appendix A

Appendix A.1.

Appendix A.2.

| Acceleration coefficients & |

γ value searching bounds |

Particle swarm size | Maximum iterations |

| 0.5 | (0.1, 100) | 100 | 100 |

| Acceleration Coefficients & |

well rates searching bounds |

Particle swarm size | Maximum iterations |

| 0.5 | (0.15, 1.0) | 100 | 100 |

Appendix B

Appendix Β.1.

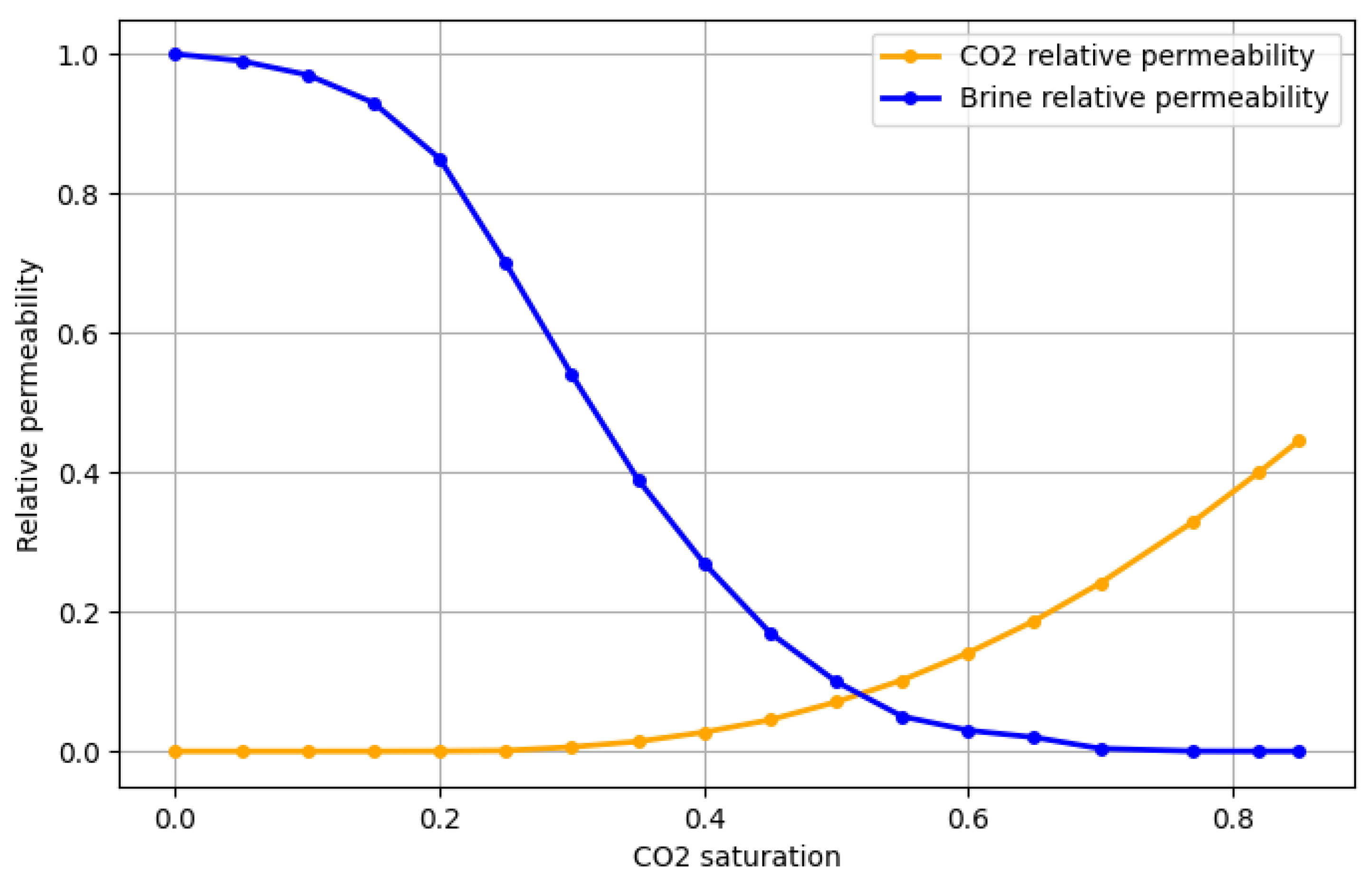

| CO2 saturation | CO2 relative permeability |

Brine relative permeability |

| 0.00 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 |

| 0.05 | 0.0000 | 0.9900 |

| 0.10 | 0.0000 | 0.9700 |

| 0.15 | 0.0000 | 0.9300 |

| 0.20 | 0.0002 | 0.8500 |

| 0.25 | 0.0010 | 0.7000 |

| 0.30 | 0.0062 | 0.5400 |

| 0.35 | 0.0140 | 0.3900 |

| 0.40 | 0.0273 | 0.2700 |

| 0.45 | 0.0450 | 0.1700 |

| 0.50 | 0.0707 | 0.1000 |

| 0.55 | 0.1020 | 0.0500 |

| 0.60 | 0.1412 | 0.0300 |

| 0.65 | 0.1870 | 0.0200 |

| 0.70 | 0.2412 | 0.0040 |

| 0.77 | 0.3288 | 0.0002 |

| 0.82 | 0.4000 | 0.0000 |

| 0.85 | 0.4450 | 0.0000 |

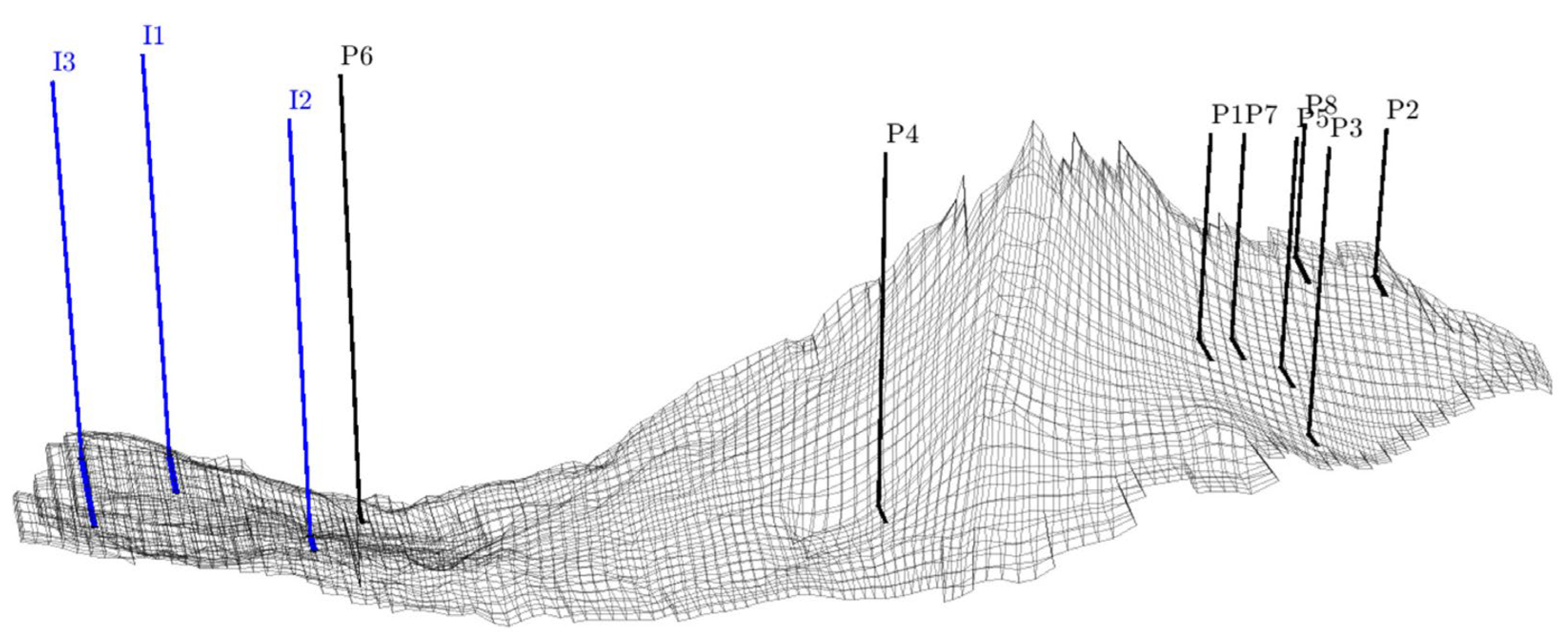

| Well name | Group | Wellhead location grid cells (x, y) |

Connection grid cells (upper, lower) |

Skin factor |

| I1 | Injectors | 84, 15 | 1, 4 | 0.708 |

| I2 | Injectors | 60, 26 | 1, 4 | 0.708 |

| I3 | Injectors | 74, 9 | 1, 4 | 0.708 |

| P1 | Producers | 62, 100 | 1, 3 | 0.708 |

| P2 | Producers | 70, 117 | 4, 4 | 0.708 |

| P3 | Producers | 57, 108 | 1, 3 | 0.708 |

| P4 | Producers | 53, 72 | 4, 4 | 0.708 |

| P5 | Producers | 62, 107 | 1, 3 | 0.708 |

| P6 | Producers | 76, 29 | 4, 4 | 0.708 |

| P7 | Producers | 63, 103 | 1, 3 | 0.708 |

| P8 | Producers | 70, 110 | 4, 4 | 0.708 |

Appendix C

Appendix C.1.

| (Mtpa) | (Mtpa) | (Mtn) | Absolute Error (%) | |

| 1 | 0.75 | 90 | 90.75 | 0.8 |

| 0.8 | 0.9 | 88.9 | 89.2 | 0.3 |

| 0.9 | 0.7 | 90.9 | 91.2 | 0.32 |

Appendix C.2.

| (Mtpa) | (Mtn) (γ* = 4.2) | Absolute Error (%) | |

| (0.34, 0.78, 0.73, 0.65) | 92.7 | 90.4 | 2.54 |

| (0.91, 0.22, 0.51, 0.86) | 88.7 | 85.9 | 3.26 |

| (0.61, 0.34, 0.65, 0.90) | 88.7 | 86.2 | 2.9 |

| (0.84, 0.16, 0.83, 0.67) | 93.8 | 91.1 | 2.96 |

| (0.96, 0.44, 0.23, 0.87) | 87 | 84.2 | 3.32 |

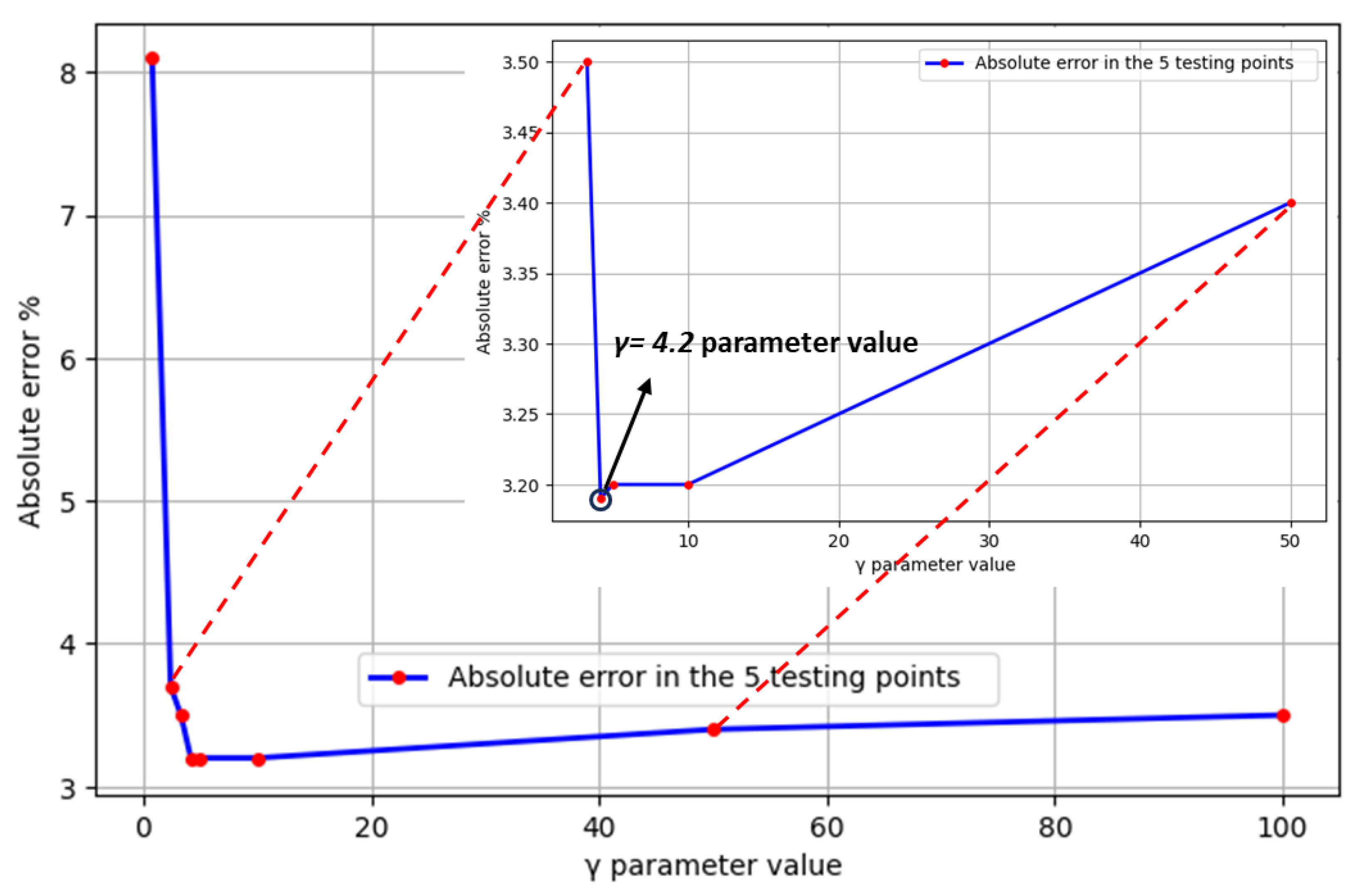

| γ parameter value | Absolute Error (%) |

| γ1 = 0.77 | 8.10 |

| γ2 = 2.4 | 3.70 |

| γ3 = 3.3 | 3.50 |

| γ4 = 4.2 | 3.20 |

| γ5 = 5 | 3.20 |

| γ6 = 10 | 3.20 |

| γ7 = 50 | 3.40 |

| γ8 = 100 | 3.50 |

References

- Lee, H.; Romero, J. AR6 Synthesis Report; Geneva, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- I. P. on C. C. (IPCC), Ed., Annex I: Glossary. In Global Warming of 1.5 °C: IPCC Special Report on Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C above Pre-industrial Levels in Context of Strengthening Response to Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2022; pp. 541–562. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, I.; Gaganis, V. Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage in Saline Aquifers: Subsurface Policies, Development Plans, Well Control Strategies and Optimization Approaches—A Review. 2023, MDPI. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L. Research progress on CO2 capture and utilization technology. Journal of CO2 Utilization 2022, vol. 66, 102260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Li, Q. A Review of Pipeline Transportation Technology of Carbon Dioxide. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2019, vol. 310(no. 3), 032033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotias, S.; Gaganis, V.; Bellas, S. Integrated Raw Material Approach to Sustainable Geothermal Energy Production: Harnessing CO2 for Enhanced Resource Utilization. Technical Annals 2024, vol. 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotias, S. P.; Ismail, I.; Gaganis, V. Optimization of Well Placement in Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS): Bayesian Optimization Framework under Permutation Invariance. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2024, vol. 14(no. 8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail; Gaganis, V. Well Control Strategies for Effective CO2 Subsurface Storage: Optimization and Policies; MDPI AG, Jan 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, G.; Zhang, W.; Huang, W. Urban Near-surface Characterization Using Passive Fiber-optic Accelerometer Array Records: A Case Study. 2025, vol. 2025(no. 1), 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amvrazis, M.; Ismail, I.; Ktenas, D.; Gaganis, V.; Tartaras, E.; Stefatos, A. Prinos CO2 Storage Permit Application: An Integrated Technical and Regulatory Workflow. 2025, vol. 2025(no. 1), 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail; Fotias, S. P.; Gaganis, V. A Holistic Framework for Optimizing CO2 Storage: Reviewing Multidimensional Constraints and Application of Automated Hierarchical Spatiotemporal Discretization Algorithm. Energies (Basel) 2025, vol. 18(no. 22). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “citations-20251214T204338”.

- White, J. A. Geomechanical behavior of the reservoir and caprock system at the In Salah CO2 storage project. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, vol. 111(no. 24), 8747–8752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Lau, H. C.; Chen, Z. Extension of CO2 storage life in the Sleipner CCS project by reservoir pressure management. J Nat Gas Sci Eng 2022, vol. 108, 104814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail; Fotias, S. P.; Avgoulas, D.; Gaganis, V. Integrated Black Oil Modeling for Efficient Simulation and Optimization of Carbon Storage in Saline Aquifers. Energies (Basel) 2024, vol. 17(no. 8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Gildin, E.; Kompantsev, G. Optimization of pressure management strategies for geological CO2 storage using surrogate model-based reinforcement learning. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control 2024, vol. 138, 104262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanakaki, E. M.; Fotias, S. P.; Gaganis, V. Application of an Automated Machine Learning-Driven Grid Block Classification Framework to a Realistic Deep Saline Aquifer Model for Accelerating Numerical Simulations of CO2 Geological Storage. Processes 2025, vol. 13(no. 8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. John, R. C.; Draper, N. R. D-Optimality for Regression Designs: A Review. Technometrics 1975, vol. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Song; Zhaojie. D-optimal design for Rapid Assessment Model of CO2 flooding in high water cut oil reservoirs. J Nat Gas Sci Eng 2014, vol. 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Delshad, M.; Sepehrnoori, K. Development of a framework for optimization of reservoir simulation studies. J Pet Sci Eng 2007, vol. 59(no. 1–2), 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mudhafar, Watheq J.; Wojtanowicz, Andrew K. Leveraging Designed Simulations and Machine Learning to Develop a Surrogate Model for Optimizing the Gas–Downhole Water Sink–Assisted Gravity Drainage (GDWS-AGD) Process to Improve Clean Oil Production. Processes 2024, vol. 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxendale, D. OPEN POROUS MEDIA OPM Flow Reference Manual; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, F. The Open Porous Media Flow reservoir simulator. Computers & Mathematics with Applications 2021, vol. 81, 159–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Deng, X.; Jin, R. Bayesian D-Optimal Design of Experiments with Quantitative and Qualitative Responses. Apr 2023. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2304.08701.

- Press, William H.; Teukolsky, Saul A.; Vetterling, William T.; Flannery, Brian P. Numerical Recipes in C The Art of Scientific Computing, Second; Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge: Cambridge, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z. D-optimal design for Rapid Assessment Model of CO2 flooding in high water cut oil reservoirs. J Nat Gas Sci Eng 2014, vol. 21, 764–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Aguiar, P. F.; Bourguignon, B.; Khots, M. S.; Massart, D. L.; Phan-Than-Luu, R. D-optimal designs. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 1995, vol. 30(no. 2), 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. P. D., K; Asche, Thomas S.; Kleinekorte, Johanna. BoFire: Bayesian Optimization Framework Intended for Real Experiments. In ArXiv; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Nocedal, Jorge; Wright, Stephen J. Numerical Optimization, 2nd ed.; Springer: California: New York, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ostertagová, E. Modelling using Polynomial Regression. Procedia Eng 2012, vol. 48, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2011, vol. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher, M. Bishop, Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer Science + Business Media: New York, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen, Pauli; Gommers, Ralf; Oliphant, Travis E.; Haberland, Matt. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat Methods 2020, vol. 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhang, B.; Zheng, X.; Chen, W. A comparative study of different radial basis function interpolation algorithms in the reconstruction and path planning of γ radiation fields. Nuclear Engineering and Technology 2024, vol. 56(no. 7), 2806–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogan, Adrijan; Kolar-Požun, Andrej; Kosec, Gregor. A Numerical Study of Combining RBF Interpolation and Finite Differences to Approximate Differential Operators. ArXiv 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks are Radial Basis Function Networks; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Abualigah, L. Particle Swarm Optimization: Advances, Applications, and Experimental Insights. Computers, Materials and Continua 2025, vol. 82(no. 2), 1539–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangfu, X. Z. A hybrid global maximum power point tracking control method based on particle swarm optimization (PSO) and perturbation and observation (P&O). Electric Power Systems Research vol. 248. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, L. J. V. PySwarms: a research toolkit for Particle Swarm Optimization in Python. J Open Source Softw, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bagci, Suat. CO2 Injection Well Design Considerations: Completion Design to Injectivity Analysis. SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fotias, S. P.; Ismail, I.; Tartaras, E.; Stefatos, A.; Gaganis, V. Optimizing CO2 Injection Rates in CCS: a Bayesian Approach for Realistic Business Efficiency. 2024, vol. 2024(no. 1), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, F. F. Edward A. Exploring for Oil and Gas Traps.

- Geology In, Geothermal Gradient.

- Chen, B.; Harp, D. R.; Lin, Y.; Keating, E. H.; Pawar, R. J. Geologic CO2 sequestration monitoring design: A machine learning and uncertainty quantification based approach. Appl Energy 2018, vol. 225, 332–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanin, E. Geomechanical risk assessment for CO2 storage in deep saline aquifers. Journal of Rock Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, V. Gaganis; Tartaras, E.; Stefatos, A. Spatiotemporal Hierarchical Optimization of CO2 Injection Schedules: An Industry-Ready Framework. In Fifth EAGE Eastern Mediterranean Workshop; European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers: Cairo, Egypt, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Amvrazis, M.; Ismail, I.; Ktenas, D.; Gaganis, V.; Tartaras, E.; Stefatos, A. Prinos CO2 Storage Permit Application: An Integrated Technical and Regulatory Workflow. In Fifth EAGE Eastern Mediterranean Workshop; European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers: Cairo, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Furre, K.; Eiken, O.; Alnes, H.; Vevatne, J. N.; Kiær, A. F. 20 Years of Monitoring CO2-injection at Sleipner. Energy Procedia 2017, vol. 114, 3916–3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotias, S. P.; Gaganis, V. Sensitivity of CO2 Flow in Production/Injection Wells in CPG (CO2 Plume Geothermal) Systems. Materials Proceedings, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Trimi, P.-M. A Review of Caprock Integrity in Underground Hydrogen Storage Sites: Implication of Wettability, Interfacial Tension, and Diffusion. Hydrogen 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, R.; Ghahramani, K.; Khojamli, S.; Mihrin, D.; Feilberg, K. L. Experimental Investigation of the Effect of Major Impurities in the CO2 Stream on Carbon Storage in Chalk Reservoirs. SPE Europe Energy Conference and Exhibition, Turin, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

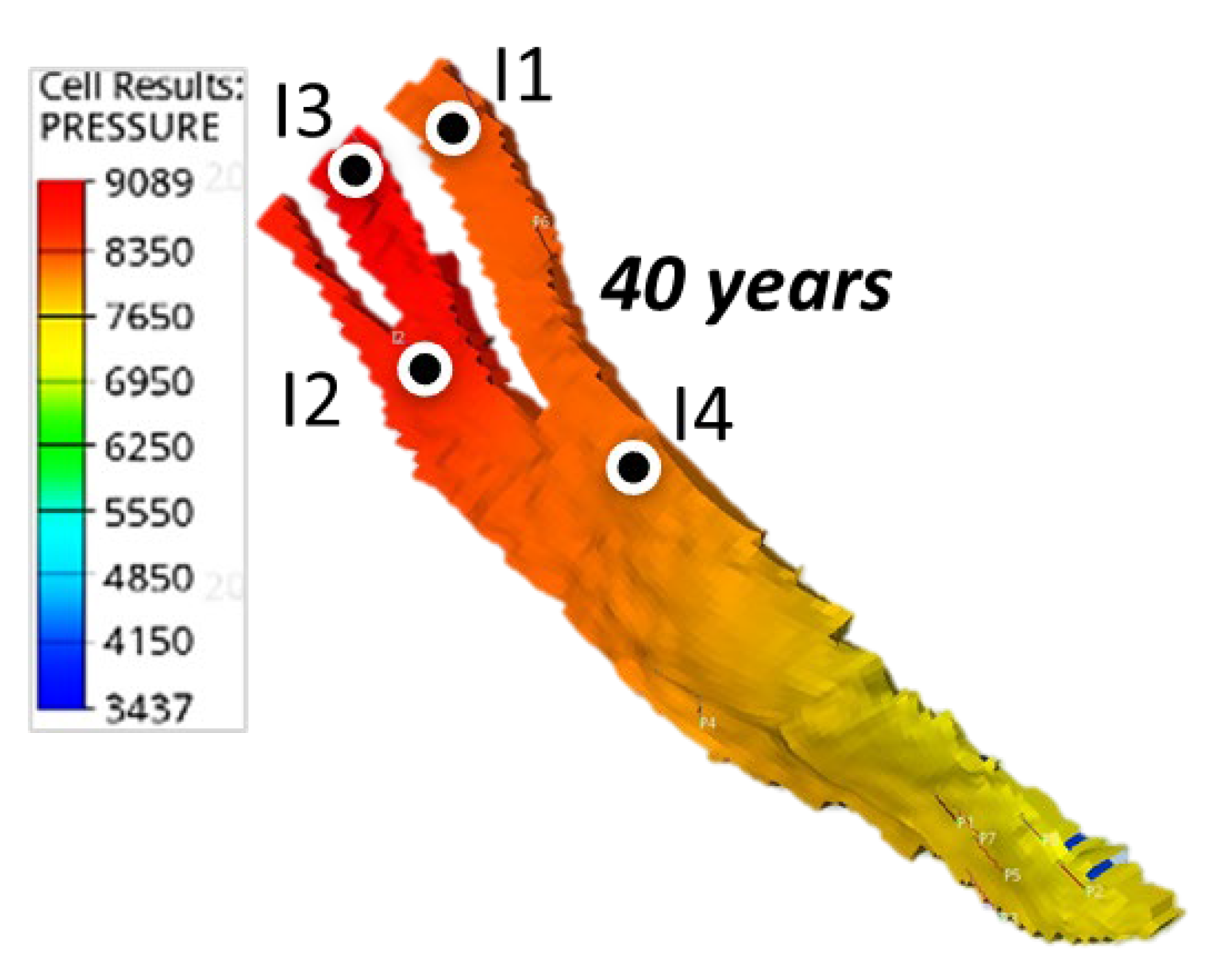

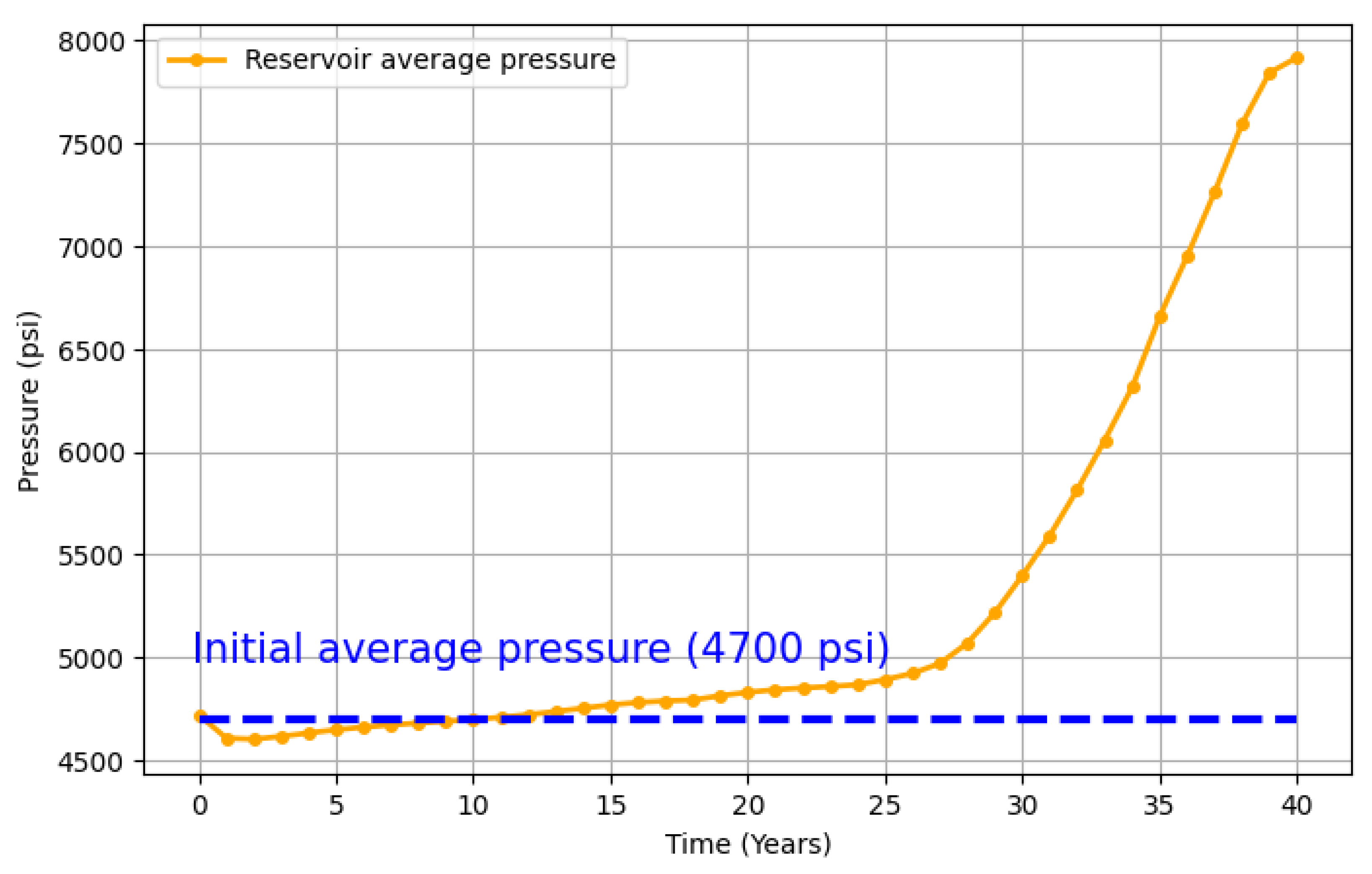

| Group | Maximum brine production (Mstb/day) | Maximum CO2 production (MMscf/day) |

BHP limits (psi) |

| Field | 80 | 6.0 | - |

| Producers | 60 | 4.0 | 3,000 |

| Injectors | - | - | 9,000 |

| I1 (Mtpa) | I2 (Mtpa) | (Mtn) |

| 1.00 | 1.00 | 80 |

| 1.00 | 0.50 | 80 |

| 0.50 | 1.00 | 80 |

| 0.75 | 0.75 | 80 |

| I1 (Mtpa) | I2 (Mtpa) | (Mtn) |

| 0.75 | 0.75 | 90.7 |

| 1.00 | 0.50 | 93.3 |

| 0.50 | 1.00 | 89.5 |

| 1.00 | 1.00 | 86.7 |

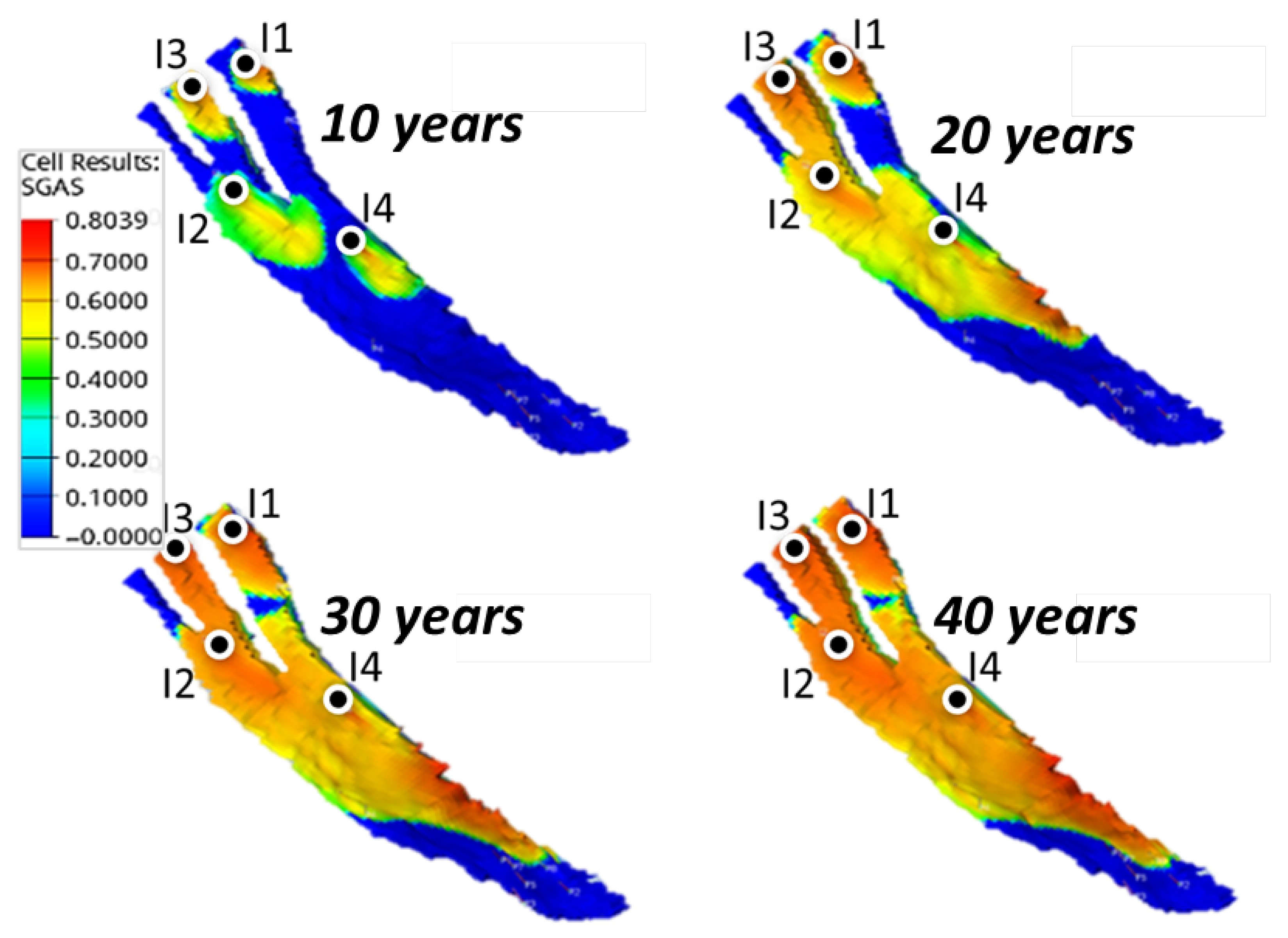

| Point | ξ= (I1, I2, I3, I4) (Mtpa) | (Mtn) |

| 1 | (0.35, 1.00, 1.00, 0.15) | 95.3 |

| 2 | (0.35, 0.15, 1.00, 1.00) | 89.0 |

| 3 | (0.78, 0.15, 0.57, 1.00) | 83.6 |

| 4 | (0.15, 0.47, 1.00, 0.88) | 94.2 |

| 5 | (1.00, 0.15, 1.00, 0.35) | 94.9 |

| 6 | (0.15, 1.00, 0.90, 0.45) | 96.1 |

| 7 | (0.65, 0.61, 0.62, 0.62) | 87.6 |

| 8 | (1.00, 1.00, 0.35, 0.15) | 87.3 |

| 9 | (0.78, 0.57, 1.00, 0.15) | 93.0 |

| Point | (I1, I2, I3, I4) (Mtpa) | γ | (Mtn) |

| 10 | (0.15, 0.92, 1.0, 0.43) | 0.73 | 96.8 |

| 11 | (0.15, 0.95, 1.0, 0.40) | 0.77 | 96.7 |

| 12 | (0.15, 0.85, 1.0, 0.50) | 4.20 | 96 |

| 13 | (0.21, 0.93, 0.96, 0.40) | 4.23 | 97.4 |

| 14 | (0.21, 0.93, 0.96, 0.40) | 4.18 | 97.4 |

| 15 | (0.21, 0.93, 0.96, 0.40) | 4.19 | 97.4 |

| Case | Number of injectors | Targeted CO2 sequestration (Mtn) | Achieved CO2 sequestration (Mtn) | D-optimal design points | Simulations required |

| Case 1 | 3 | 80 | 80 | 4 | 4 |

| Case 2 | 3 | 100 | 93.3 | 4 | 5 |

| Case 3 | 4 | 100 | 97.4 | 9 | 15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).