1. Introduction

Rheumatic and autoimmune diseases are characterised by chronic inflammation, immune dysregulation, microvascular damage, and persistent oxidative stress. In rheumatoid arthritis (RA), synovial hyperplasia, pannus formation, and progressive joint destruction are driven by autoantibody production, pro-inflammatory cytokine networks, and a redox environment that amplifies tissue injury and bone erosion [

1,

2,

3]. Oxidative stress contributes to antigen modification, activation of NF-κB signalling, and sustained cytokine production, thereby promoting synovial inflammation and joint damage [

2,

4].

In systemic sclerosis (SSc), early endothelial injury and capillary rarefaction result in severe microangiopathy, Raynaud phenomenon, digital ulcers, and progressive fibrosis of the skin and internal organs. Redox imbalance and impaired antioxidant defences play a central role in endothelial dysfunction, altered vasoreactivity, and fibroblast activation in SSc [

4,

5,

6]

Osteoarthritis (OA), traditionally considered a degenerative “wear-and-tear” disorder, is now recognised as a low-grade inflammatory disease in which oxidative stress, metabolic factors, and synovial inflammation contribute to chondrocyte dysfunction, extracellular matrix degradation, and pain [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Increased reactive oxygen species production within the joint microenvironment accelerates cartilage degeneration and perpetuates nociceptive signalling.

Fibromyalgia and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), frequently encountered in rheumatology practice, are characterised by chronic widespread pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and cognitive dysfunction. Growing evidence implicates mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, autonomic imbalance, and neuroimmune dysregulation in their pathophysiology, with abnormalities in redox homeostasis and energy metabolism consistently reported [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Despite major advances in disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), biologics, and targeted synthetic therapies, many patients with rheumatic and related conditions continue to experience residual disease activity, chronic pain, fatigue, or treatment-limiting toxicity.

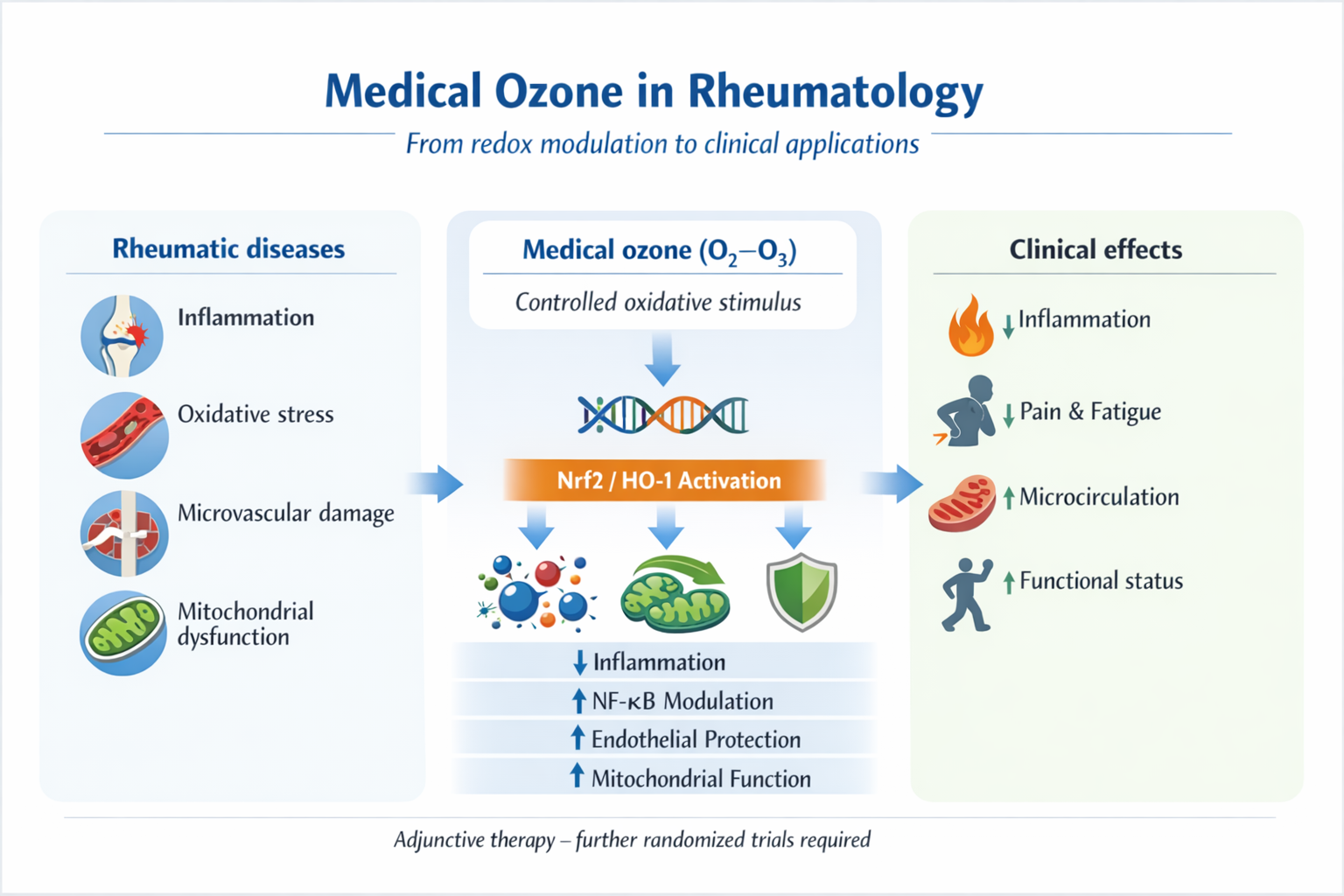

These unmet clinical needs have stimulated interest in adjunctive, non-pharmacological approaches capable of modulating redox imbalance, microcirculatory dysfunction, and neuroimmune activation. Medical ozone, as originally conceptualised by Bocci, is a calibrated mixture of ozone (O₃) and oxygen (O₂) generated from medical-grade oxygen and administered at precisely controlled concentrations and volumes [

1]. When applied using established medical techniques—such as major autohemotherapy, rectal insufflation, local “bagging”, or intra-articular injection—ozone induces a mild and transient oxidative stimulus that activates endogenous antioxidant and cytoprotective pathways rather than causing tissue damage [

1,

3,

4].

Through the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid oxidation products (LOPs) acting as signalling molecules, medical ozone triggers adaptive responses including activation of the Nrf2/heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) pathway, modulation of NF-κB and inflammasome signalling, improvement of endothelial function and microcirculation, and effects on mitochondrial metabolism and neuroimmune regulation [

2,

3,

4,

6,

16]. These mechanisms directly intersect with key pathogenic pathways involved in inflammatory, autoimmune, degenerative, and chronic pain conditions commonly managed in rheumatology.

The aim of this narrative review is to integrate mechanistic insights and clinical evidence on medical ozone therapy across major rheumatologic and related conditions, including RA, SSc, OA, fibromyalgia, and ME/CFS. In addition, the review explores emerging data on ozone as an adjunct to immunosuppressive or cytotoxic therapies and its potential role in complex joint infections, highlighting areas where further high-quality clinical research is required.

2. Literature Overview and Methods

2.1. Review Design

This article is a narrative review designed to provide a comprehensive and critical overview of the biological rationale and clinical evidence supporting the use of medical ozone in rheumatology. Given the heterogeneity of study designs, patient populations, clinical endpoints, and ozone administration protocols, a formal systematic review or meta-analysis was not considered appropriate.

The narrative approach was chosen to allow integration of mechanistic insights, translational evidence, and clinical data across autoimmune, inflammatory, degenerative, and chronic pain conditions commonly encountered in rheumatologic practice.

2.2. Literature Search Strategy

A structured, but non-systematic, literature search was conducted using the PubMed and Scopus databases, covering publications from January 2000 to October 2025. Searches combined free-text terms related to ozone therapy and rheumatology, including:“ozone therapy”, “oxygen–ozone”, “ozone autohemotherapy”, “major autohemotherapy”, “rectal insufflation”, “intra-articular ozone”, “rheumatoid arthritis”, “systemic sclerosis”, “scleroderma”, “Raynaud phenomenon”, “digital ulcers”, “osteoarthritis”, “fibromyalgia”, “chronic fatigue syndrome”, “myalgic encephalomyelitis”, “microcirculation”, “oxidative stress”, “chemotherapy-induced toxicity”, “peripheral neuropathy”, “septic arthritis”, “prosthetic joint infection”, and “biofilm”.

To ensure coverage of foundational concepts and translational mechanisms, reference lists of key narrative reviews, original clinical studies, and seminal mechanistic publications—including Bocci’s monograph and subsequent experimental and clinical works—were manually screened.

2.3. Study Selection and Evidence Inclusion

The literature considered in this narrative review primarily included clinical studies conducted in human subjects that evaluated the use of systemic or local medical ozone in conditions relevant to rheumatologic practice. Attention was given to studies involving autoimmune and inflammatory rheumatic diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic sclerosis, as well as degenerative joint disorders including osteoarthritis. Evidence was also drawn from studies addressing chronic pain and fatigue syndromes frequently managed by rheumatologists, notably fibromyalgia and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). In addition, publications examining treatment-related toxicities and infectious complications of specific relevance to rheumatology—such as methotrexate-associated hepatotoxicity, chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, and septic or prosthetic joint infections—were included to provide a broader clinical perspective.

Alongside clinical evidence, mechanistic and translational studies were considered where they contributed to understanding the biological effects of medical ozone, particularly in relation to redox modulation, immunoregulatory pathways, mitochondrial function, and microcirculatory changes. These studies were used to contextualise clinical findings and to support the pathophysiological rationale discussed throughout the review.

Publications focusing on environmental or accidental ozone exposure, the use of non-medical or non-calibrated ozone devices, or studies lacking clear clinical or translational relevance were not considered for inclusion.

2.4. Evidence Synthesis and Presentation

Evidence was synthesised narratively, with explicit differentiation between levels of clinical evidence (randomised trials, observational studies, and case-based reports). Greater interpretative weight was given to controlled and randomised studies where available, while observational and case reports were used to contextualise emerging or exploratory applications.

Given the narrative nature of the review, no formal risk-of-bias assessment or quantitative synthesis was performed. Instead, methodological limitations, heterogeneity of protocols, and strength of evidence are discussed qualitatively within each disease-specific section to allow critical interpretation by the reader.

3. Mechanisms of Action of Medical Ozone and Relevance to Rheumatic Diseases

Medical ozone exerts its biological effects through a mechanism fundamentally different from that of conventional pharmacological agents. When administered at low and controlled concentrations according to established medical protocols, ozone induces a brief and self-limited oxidative stimulus that activates adaptive cellular responses rather than causing tissue damage. This concept, initially described by Bocci, defines medical ozone as a redox-modulating agent capable of triggering endogenous antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cytoprotective pathways [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The main pathophysiological targets of medical ozone therapy relevant to rheumatologic diseases are summarized in [

Table 1].

During major autohemotherapy, a defined volume of the patient’s blood is exposed ex vivo to a calibrated oxygen–ozone mixture and subsequently reinfused. Ozone rapidly dissolves in the aqueous phase and reacts with polyunsaturated fatty acids, antioxidants, and other biological substrates, leading to the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), particularly hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), and lipid oxidation products (LOPs) [

1,

6,

16]. These molecules act as secondary messengers rather than direct oxidants. H₂O₂ freely diffuses across cell membranes and transiently modifies redox-sensitive signalling pathways, while LOPs, including aldehydes such as 4-hydroxynonenal, exert longer-lasting regulatory effects on gene expression and cellular metabolism [

4,

6,

16].

A central consequence of this controlled oxidative challenge is activation of the nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway. Nrf2 translocate to the nucleus and binds to antioxidant response elements, inducing the expression of a broad array of cytoprotective enzymes, including superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase, glutathione S-transferase, and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) [

2,

4,

16]. HO-1 plays a particularly important role by degrading heme into biliverdin, carbon monoxide, and free iron, thereby conferring antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and vasodilatory effects. Clinical and experimental studies have consistently demonstrated increased HO-1 expression and improved redox profiles following medical ozone therapy [

4,

6,

16].

This adaptive antioxidant response is highly relevant to rheumatic diseases, in which chronic oxidative stress contributes to tissue damage, immune activation, and disease progression. In rheumatoid arthritis, persistent redox imbalance within the synovium amplifies cytokine production, osteoclast activation, and joint destruction. In systemic sclerosis, oxidative stress is closely linked to endothelial dysfunction, impaired vasoreactivity, and fibroblast activation. Similarly, in osteoarthritis, excessive ROS production accelerates chondrocyte senescence and extracellular matrix degradation, while in fibromyalgia and ME/CFS oxidative stress and impaired antioxidant defences are associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and fatigue [

1,

2,

3,

4,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

Beyond antioxidant induction, medical ozone influences inflammatory signalling pathways. While uncontrolled oxidative stress promotes activation of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and perpetuates inflammation, controlled ozone exposure—through Nrf2 and HO-1 upregulation—has been associated with downregulation of NF-κB–dependent transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β, and interleukin-6 [

2,

3,

4]. This modulatory effect allows attenuation of excessive inflammatory responses without inducing broad immunosuppression, a feature that may be advantageous in patients already receiving DMARDs or biologic therapies.

Redox balance is also tightly linked to activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, a key driver of interleukin-1β maturation and secretion. Persistent inflammasome activation has been implicated in several rheumatic and autoinflammatory conditions. By improving mitochondrial function and reducing pathological ROS signalling, ozone may indirectly limit inflammasome activation, although direct evidence in rheumatic diseases remains limited and warrants further investigation [

2].

Medical ozone additionally exerts important effects on endothelial function and microcirculation. Endothelial dysfunction and impaired tissue perfusion are central features of systemic sclerosis and contribute to musculoskeletal pathology in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Ozone therapy has been shown to improve erythrocyte deformability, increase 2,3-diphosphoglycerate levels, and enhance oxygen delivery to peripheral tissues [

1,

4,

6]. Furthermore, induction of HO-1 and the generation of carbon monoxide exert vasoprotective and vasodilatory effects, supporting restoration of microvascular homeostasis. These mechanisms provide a biological basis for the clinical improvements in Raynaud phenomenon, peripheral perfusion, and digital ulcer healing observed in systemic sclerosis patients treated with ozone [

5,

17].

At the cellular energy level, ozone-mediated redox modulation appears to influence mitochondrial metabolism. In conditions such as fibromyalgia and ME/CFS, increasing evidence points to impaired oxidative phosphorylation, altered lactate metabolism, and mitochondrial dysfunction as contributors to fatigue and pain. By restoring redox balance and supporting mitochondrial enzyme activity, medical ozone may improve cellular energy efficiency and reduce metabolic stress [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. These effects, combined with modulation of neuroimmune signalling, may contribute to reductions in central sensitisation and improvements in pain perception and fatigue severity reported in clinical studies.

Taken together, the biological effects of medical ozone can be conceptualised as a hormetic response in which a controlled oxidative stimulus activates endogenous defence systems, leading to improved antioxidant capacity, attenuation of chronic inflammation, enhanced microcirculation, and optimisation of mitochondrial function. This integrated mechanism directly targets key pathogenic pathways shared across autoimmune, inflammatory, degenerative, and chronic pain conditions in rheumatology, providing a coherent mechanistic rationale for the clinical findings discussed in subsequent sections.

4. Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic autoimmune disease characterised by persistent synovial inflammation, pannus formation, progressive cartilage and bone destruction, and extra-articular manifestations. At the molecular level, RA is sustained by a complex interplay between autoantibody production, activation of innate and adaptive immune responses, and a pro-oxidant microenvironment within the synovium. Excessive generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species contributes to post-translational modification of proteins, activation of redox-sensitive transcription factors such as nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), and amplification of pro-inflammatory cytokine networks, including tumour necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6, and interleukin-1β [

1,

2,

3,

4]. These processes promote osteoclast activation, angiogenesis, and progressive joint damage. In parallel, endothelial dysfunction and impaired microcirculation contribute to both local joint pathology and the increased cardiovascular risk observed in RA patients.

Methotrexate (MTX) remains the cornerstone of RA treatment and is widely used as first-line therapy, either alone or in combination with biologic or targeted synthetic DMARDs. Despite its efficacy, a substantial proportion of patients experience incomplete disease control, persistent pain and fatigue, or treatment-limiting adverse effects. Hepatotoxicity, gastrointestinal intolerance, cytopenias, and cumulative oxidative stress are among the most common reasons for dose reduction or discontinuation. Consequently, adjunctive strategies capable of improving disease control while mitigating toxicity are of considerable clinical interest.

Preclinical evidence supports the potential role of ozone in inflammatory arthritis. In experimental models of adjuvant-induced arthritis, ozone administration has been shown to reduce synovial inflammation, joint swelling, and cartilage damage, findings consistent with its redox-modulating and anti-inflammatory properties [

18]. These observations provided a rationale for subsequent clinical evaluation in RA.

The most substantial clinical evidence in RA derives from a series of studies conducted by León Fernández, Oru, and colleagues, who investigated medical ozone as an adjunct to MTX therapy. In a randomised controlled trial, RA patients receiving stable MTX treatment were assigned to continue MTX alone or to receive additional systemic ozone administered by rectal insufflation [

19]. Patients treated with the MTX–ozone combination exhibited significantly greater improvements in disease activity, as assessed by the Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28), and in functional disability, measured by the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index, compared with those receiving MTX alone. These clinical benefits were accompanied by significant reductions in inflammatory markers, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, as well as decreases in autoantibody levels such as anti-citrullinated protein antibodies [

19].

Importantly, the addition of ozone was associated with a marked improvement in oxidative stress parameters. Markers of lipid peroxidation were reduced, while antioxidant defences, including reduced glutathione levels, increased significantly only in the group receiving ozone in combination with MTX [

19]. Correlations between improved redox status and clinical response suggested that correction of oxidative imbalance may be a key mechanism underlying the observed therapeutic benefit.

Subsequent work by the same group focused on the hepatic safety of MTX in RA patients treated with adjunctive ozone. In this study, patients receiving MTX plus ozone showed a significantly lower incidence of abnormalities in γ-glutamyl transferase and alkaline phosphatase compared with those treated with MTX alone [

20]. These findings were accompanied by improved antioxidant profiles, and an inverse relationship between liver enzyme levels and glutathione concentrations supported the hypothesis that ozone-mediated redox modulation may confer hepatoprotective effects in the context of MTX therapy [

20].

Further evidence was provided by a follow-up study evaluating the effects of a second cycle of ozone therapy in RA patients already treated with MTX and ozone [

21]. A repeated ozone cycle led to additional improvements in disease activity, functional status, and oxidative stress markers, suggesting that the adaptive responses induced by ozone may persist or be reinforced over time. The authors proposed that repeated controlled oxidative stimuli could induce a form of “innate immune memory” favouring a more regulated inflammatory response [

21].

In a broader analysis of patients with chronic inflammatory diseases, medical ozone was described as a redox regulator with apparent selectivity for RA, in that patients with higher baseline oxidative stress derived greater clinical and biochemical benefit from ozone therapy [

22]. This observation aligns with the concept that RA, as a disease characterised by pronounced oxidative imbalance, may be particularly responsive to interventions targeting redox homeostasis. Mechanistically, potential synergistic effects between MTX and ozone may involve shared pathways related to adenosine signalling, redox-sensitive immunomodulation, and endothelial function [

5,

22].

Collectively, the available evidence suggests that medical ozone, when used as an adjunct to MTX, can enhance clinical response, improve redox balance, and reduce biochemical markers of hepatotoxicity in RA without compromising short- to medium-term safety [

5,

19,

20,

21,

22]. While these findings are encouraging, they are largely derived from single-centre studies and require confirmation in larger, multicentre randomised trials with longer follow-up. Nevertheless, RA represents one of the rheumatic diseases in which the mechanistic rationale and clinical data supporting adjunctive ozone therapy are currently most developed.

5. Systemic Sclerosis and Vasculopathy

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a complex autoimmune disease characterised by immune activation, widespread microvascular dysfunction, and progressive fibrosis of the skin and internal organs. Vascular injury represents an early and central event in disease pathogenesis, preceding overt fibrosis and organ involvement. Endothelial cell damage, capillary rarefaction, and dysregulated vasoreactivity lead to chronic tissue hypoxia and contribute to hallmark clinical manifestations such as Raynaud phenomenon, digital ulcers, and pulmonary arterial hypertension. Oxidative stress and impaired antioxidant responses play a pivotal role in sustaining endothelial dysfunction and promoting fibroblast activation in SSc [

4,

5,

6].

Reactive oxygen species contribute to endothelial apoptosis, reduced nitric oxide bioavailability, and increased expression of vasoconstrictors, thereby perpetuating microangiopathy. At the same time, oxidative stress promotes activation of profibrotic pathways, including transforming growth factor-β signalling, linking vascular injury to tissue fibrosis. Given this pathophysiological background, therapeutic approaches capable of restoring redox balance and improving microcirculatory function are of particular interest in SSc.

Medical ozone, through its ability to induce adaptive antioxidant responses and modulate endothelial function, has been explored as an adjunctive therapy in SSc, primarily targeting vascular manifestations. Non-invasive ozone-based balneotherapy has been evaluated in patients with Raynaud phenomenon. In a prospective study using ozone-enriched water baths, significant improvements in peripheral microcirculation were demonstrated by thermographic assessment, accompanied by reductions in the frequency and severity of Raynaud attacks and improvements in patient-reported symptoms [

5]. Although the intervention was part of a multimodal balneophysiotherapy programme, the observed enhancement of peripheral perfusion is consistent with the known vasoprotective and redox-modulating effects of ozone.

More direct evidence is available for the treatment of digital ulcers, one of the most debilitating and therapeutically challenging complications of SSc [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Digital ulcers are associated with severe pain, functional impairment, and a high risk of secondary infection, and they often persist despite optimal use of vasodilators, prostanoids, and endothelin receptor antagonists [

23,

25,

27]. In a randomised controlled trial, patients with SSc-related digital ulcers receiving standard care were compared with those receiving standard care plus local oxygen–ozone therapy delivered via a sealed bag enclosing the affected limb [

28]. Patients treated with ozone showed significantly higher rates of ulcer healing, shorter healing times, and greater pain reduction compared with controls. The treatment was well tolerated, with no significant adverse events reported [

28].

Additional support for the role of ozone in SSc vasculopathy comes from case-based evidence. Successful healing of refractory digital ulcers following local oxygen–ozone therapy has been reported in patients who had failed conventional medical treatments [

29]. A randomized controlled trial reported that local oxygen–ozone therapy combined with standard care achieved a significantly higher healing rate of refractory digital ulcers (92% vs. 42%) and improved functional disability in patients with systemic sclerosis [

30]

Moreover, systemic administration of ozone via major autohemotherapy has been associated with rapid and sustained improvement in Raynaud symptoms, reduction of hand oedema, and functional recovery in individual patients with severe vascular involvement. Notably, this report represents the first description of a potential change in nailfold capillaroscopic patterns following ozone autohemotherapy [

17]. While anecdotal, these observations are biologically plausible and consistent with the effects of ozone on microcirculation and endothelial homeostasis

The beneficial vascular effects of ozone in SSc are likely mediated by multiple converging mechanisms. Activation of the Nrf2/heme oxygenase-1 pathway enhances antioxidant defences within the vascular wall, while carbon monoxide generated by heme degradation exerts vasodilatory and cytoprotective effects. Improvements in erythrocyte deformability and oxygen delivery further contribute to enhanced tissue perfusion. Together, these effects may counteract chronic hypoxia and endothelial dysfunction, key drivers of Raynaud phenomenon and digital ulcer formation in SSc [

4,

5,

6,

17,

28,

29].

Overall, the available evidence suggests that medical ozone may represent a useful adjunctive approach for selected vascular manifestations of systemic sclerosis, particularly Raynaud phenomenon and digital ulcers. However, current data are limited by small sample sizes and a predominance of single-centre studies. Larger, well-designed randomised trials are needed to confirm efficacy, define optimal treatment protocols, and clarify the role of systemic versus local ozone therapy in the broader management of SSc vasculopathy.

6. Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most prevalent joint disease encountered in rheumatologic practice and represents a major cause of pain, disability, and reduced quality of life worldwide. Although traditionally regarded as a purely degenerative disorder resulting from mechanical wear, OA is now recognised as a complex disease involving low-grade inflammation, metabolic dysregulation, and oxidative stress affecting the entire joint organ, including cartilage, synovium, subchondral bone, and periarticular tissues. Increased production of reactive oxygen species within the joint microenvironment contributes to chondrocyte senescence, mitochondrial dysfunction, extracellular matrix degradation, and activation of nociceptive pathways, thereby sustaining pain and functional impairment [

7,

8,

9,

10].

Current intra-articular treatment options for OA, such as corticosteroids and hyaluronic acid, provide symptomatic relief in selected patients but are often limited by transient efficacy or variable clinical response. Consequently, there has been growing interest in alternative or adjunctive intra-articular therapies capable of modulating inflammation and oxidative stress while maintaining an acceptable safety profile.

Medical ozone has been extensively investigated as an intra-articular treatment for knee osteoarthritis, making OA the rheumatologic condition with the largest body of clinical evidence supporting ozone therapy. The rationale for its use is based on its capacity to modulate redox balance, reduce inflammatory mediators, and influence pain processing at both peripheral and central levels. When injected intra-articularly at controlled concentrations, ozone induces a local adaptive response rather than direct oxidative damage, consistent with the concept of hormesis.

A systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating intra-articular ozone therapy in knee OA demonstrated consistent and clinically meaningful reductions in pain compared with baseline and with control interventions across multiple studies, most of which were randomised or controlled [

7]. This analysis provided quantitative support for the analgesic efficacy of ozone and highlighted its potential as a minimally invasive treatment option for chronic knee OA.

High-quality randomised controlled trials further substantiate these findings. In a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study, intra-articular ozone injections were compared with placebo (medical oxygen) in patients with knee OA [

8]. Patients treated with ozone experienced significantly greater reductions in pain and improvements in functional outcomes, as measured by validated instruments such as the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC). Notably, the therapeutic benefits persisted for several months after completion of the injection cycle, suggesting effects beyond short-term analgesia. Adverse events were mild, transient, and comparable to those observed in the placebo group [

8].

Additional prospective and randomised studies have confirmed the efficacy of intra-articular ozone in improving pain, physical function, and range of motion in knee OA [

9]. Although the magnitude of benefit may decrease over time, clinically relevant improvements have been reported for several months following treatment, supporting its role as a symptomatic intervention.

Dose–response relationships have also been explored. In a double-blind randomised trial comparing two ozone concentrations (20 µg/mL and 40 µg/mL) with an oxygen control, both ozone doses produced significant improvements in pain and functional mobility, whereas oxygen alone did not [

10]. No clear superiority of the higher concentration was observed, suggesting that lower ozone doses may be sufficient to achieve clinical benefit while minimising the risk of adverse effects [

10].

Taken together, these data indicate that intra-articular ozone therapy is an effective and generally safe option for reducing pain and improving function in knee osteoarthritis [

7,

8,

9,

10]. While OA is not classically an autoimmune disease, its inflammatory and oxidative components, combined with its high prevalence in rheumatologic practice, make it a relevant target for redox-modulating interventions. From a clinical perspective, ozone may be considered as an adjunctive or alternative intra-articular therapy in selected patients with symptomatic knee OA, particularly when conventional treatments provide insufficient relief or are poorly tolerated.

7. Fibromyalgia and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

Fibromyalgia and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) are chronic, disabling conditions frequently encountered in rheumatology clinics and often overlapping with autoimmune and inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Both disorders are characterised by persistent fatigue, widespread pain, sleep disturbance, cognitive dysfunction, and a broad spectrum of somatic symptoms that significantly impair quality of life. Although their aetiology remains incompletely understood, increasing evidence supports a multifactorial pathophysiology involving central sensitisation, autonomic imbalance, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and neuroimmune dysregulation [

11,

12,

13,

14,

31].

In fibromyalgia, altered pain processing within the central nervous system plays a central role, with amplification of nociceptive signalling and reduced efficacy of descending inhibitory pathways. Peripheral factors, including muscle hypoxia, metabolic abnormalities, and low-grade inflammation, may further contribute to symptom persistence. Oxidative stress has been consistently reported in fibromyalgia patients and is thought to exacerbate mitochondrial dysfunction and neuromuscular fatigue, thereby reinforcing pain and central sensitisation [

12,

15,

31].

ME/CFS is characterised by profound fatigue, post-exertional malaise, unrefreshing sleep, cognitive impairment, and orthostatic intolerance. Abnormalities in energy metabolism, impaired oxidative phosphorylation, increased lactate production, and immune dysregulation have been repeatedly described. Redox imbalance and mitochondrial dysfunction are increasingly recognised as core features linking immune activation to the hallmark symptom of disabling fatigue [

11,

13,

14]. Given this shared biological background, therapeutic strategies targeting oxidative stress, mitochondrial function, and neuroimmune pathways may be relevant to both conditions.

Medical ozone, through its capacity to modulate redox homeostasis and mitochondrial metabolism, has been investigated as a complementary therapy in fibromyalgia and ME/CFS, primarily using systemic administration via oxygen–ozone autohemotherapy. In a prospective observational study involving 65 patients with fibromyalgia, oxygen–ozone therapy led to clinically meaningful improvements in pain, fatigue, sleep quality, and overall symptom burden, with approximately 70% of patients reporting a global improvement exceeding 50% [

12]. Treatment was well tolerated, and no significant adverse events were reported.

Similar findings were observed in a subsequent case series of 40 fibromyalgia patients treated with ozone autohemotherapy, in which high response rates were reported for both pain and fatigue, again with an excellent safety profile [

31]. These results were further supported by a prospective study in which ozone autohemotherapy was associated with significant reductions in pain intensity and improvements in quality-of-life measures in fibromyalgia patients [

15].

More robust evidence was provided by a randomised controlled trial evaluating the short- and medium-term effects of major ozone autohemotherapy in fibromyalgia. Patients receiving ozone therapy experienced significantly greater reductions in pain intensity and fibromyalgia impact scores compared with controls, with benefits persisting beyond the end of the treatment period [

15]. Although sample size was limited, this study supports the potential efficacy of ozone in modulating central and peripheral mechanisms underlying fibromyalgia symptoms.

In ME/CFS, encouraging results have been reported from several observational studies. In an open-label study involving 65 patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, oxygen–ozone autohemotherapy was associated with marked reductions in fatigue severity, without serious adverse effects [

11]. These findings were replicated and extended in a larger cohort of 100 patients, in which approximately 70% achieved at least a 50% improvement in fatigue symptoms following ozone therapy [

13].

The largest available dataset derives from a multicentre observational study including 200 patients with ME/CFS treated with oxygen–ozone autohemotherapy [

14]. Using the Fatigue Severity Scale, the authors reported substantial improvements, with a significant proportion of patients shifting from the highest to the lowest fatigue scores after treatment. Overall, more than three-quarters of patients experienced clinically meaningful reductions in fatigue, and treatment was well tolerated across age and sex groups [

14].

The magnitude and consistency of these clinical improvements, although derived largely from uncontrolled studies, suggest that ozone may target central aspects of fibromyalgia and ME/CFS pathophysiology. Proposed mechanisms include restoration of redox balance, enhancement of mitochondrial efficiency, reduction of neuroinflammation, and modulation of autonomic and neuroimmune signalling. These effects may collectively contribute to reductions in central sensitisation, fatigue perception, and pain amplification [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

31].

In summary, available evidence indicates that medical ozone therapy may provide substantial symptomatic benefit in fibromyalgia and ME/CFS, particularly in terms of fatigue, pain, and quality of life. While placebo effects cannot be excluded, especially in chronic pain and fatigue conditions, the convergence of mechanistic plausibility and consistent clinical signals supports further investigation. Well-designed, sham-controlled randomised trials with mechanistic endpoints are needed to define the precise role of ozone therapy in the management of these complex syndromes.

8. Adjunctive Role of Medical Ozone in Immunosuppressive and Cytotoxic Therapies

Immunosuppressive and cytotoxic agents represent a cornerstone of treatment in many rheumatologic conditions, but their use is frequently limited by cumulative toxicity and treatment-related adverse effects. Methotrexate, conventional DMARDs, targeted synthetic agents, and biologic therapies can induce oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and organ-specific toxicity, contributing to fatigue, neuropathic symptoms, hepatic injury, and reduced treatment adherence. Strategies capable of mitigating these adverse effects without compromising therapeutic efficacy are therefore of considerable clinical interest.

Evidence from rheumatoid arthritis provides a proof of concept for the adjunctive use of medical ozone alongside immunosuppressive therapy. Clinical studies combining ozone with methotrexate have demonstrated not only enhanced disease control but also significant improvements in oxidative stress parameters and reductions in biochemical markers of hepatotoxicity [

19,

20,

21]. These findings suggest that ozone-induced activation of endogenous antioxidant systems may counterbalance methotrexate-related oxidative injury in hepatocytes, thereby reducing liver enzyme abnormalities while preserving or even augmenting anti-inflammatory efficacy. Importantly, no increase in adverse events or loss of disease control was observed in patients receiving combination therapy [

19,

20,

21].

Beyond rheumatology, the oncology literature provides additional insights into the potential role of ozone as a supportive therapy in patients exposed to cytotoxic agents. Chemotherapy is well known to induce oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage in non-tumour tissues, leading to cumulative toxicity and long-term functional impairment. Preclinical studies have shown that ozone preconditioning can reduce organ damage induced by cytotoxic drugs such as cisplatin, methotrexate, doxorubicin, and bleomycin, primarily through enhancement of antioxidant defences and attenuation of lipid peroxidation in healthy tissues [

32].

Clinical data support these experimental observations. In prospective studies of cancer survivors with chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, ozone therapy was associated with significant reductions in neuropathic pain and improvements in oxidative stress markers, with many patients experiencing sustained symptom relief after completion of treatment [

33,

34]. These improvements are biologically plausible, given the role of mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative injury in the pathogenesis of chemotherapy-induced nerve damage.

Further studies have demonstrated broader benefits of ozone therapy in patients suffering from chronic treatment-related toxicities. Improvements in health-related quality of life, assessed using validated instruments such as the EQ-5D-5L, and reductions in overall toxicity grades have been reported in symptomatic cancer survivors treated with ozone following chemotherapy or radiotherapy [

33]. In addition, ozone has been used as a supportive and palliative intervention in patients with cancer-related fatigue, with notable improvements in fatigue severity and general well-being [

35].

The mechanistic overlap between chemotherapy-induced toxicity and adverse effects observed in rheumatologic patients receiving long-term immunosuppressive therapy supports the translational relevance of these findings. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial impairment, and neuroinflammation are shared pathways underlying fatigue, neuropathy, and organ toxicity across these clinical contexts. By activating Nrf2-dependent antioxidant responses and modulating mitochondrial and neuroimmune function, ozone may reduce the burden of treatment-related side effects without exerting direct immunosuppressive effects.

From a rheumatologic perspective, these data suggest that medical ozone could be explored as an adjunctive strategy to improve treatment tolerability, reduce cumulative toxicity, and address residual symptoms such as fatigue and neuropathic pain in patients receiving conventional or advanced immunosuppressive therapies. However, direct evidence in rheumatologic populations beyond methotrexate-treated RA remains limited. Carefully designed randomised controlled trials are required to evaluate whether the supportive benefits observed in oncology can be reproduced in patients with autoimmune and inflammatory rheumatic diseases, and to define appropriate indications, timing, and safety parameters.

9. Medical Ozone in Joint, Periprosthetic, and Ulcer-Related Infections

Patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases are at increased risk of serious infections due to underlying immune dysregulation and prolonged exposure to glucocorticoids, conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), and biologic or targeted synthetic therapies. Septic arthritis and prosthetic joint infections (PJI), although relatively uncommon, represent severe complications associated with substantial morbidity, functional impairment, and healthcare burden. Standard management typically requires prolonged antimicrobial therapy and, in the case of PJI, complex surgical interventions that may include prosthesis removal and staged reimplantation.

In addition to deep musculoskeletal infections, rheumatologic patients—particularly those with systemic sclerosis, vasculitis, or severe Raynaud phenomenon—are highly susceptible to chronic skin ulcers, including digital ulcers and lower-limb ulcers. These lesions are frequently complicated by secondary bacterial infection, delayed healing, and recurrent inflammation due to impaired microcirculation, tissue hypoxia, and immune dysfunction. Infected ulcers in this population may serve as a portal of entry for systemic infection and, in severe cases, progress to osteomyelitis or sepsis.

The potential role of medical ozone in infectious settings derives from its broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, anti-biofilm effects, and its capacity to improve tissue oxygenation and modulate local inflammatory responses. Ozone exerts antimicrobial activity through oxidation of microbial cell membranes, enzymes, and nucleic acids, leading to rapid inactivation of bacteria, fungi, and viruses [

1,

2]. Unlike antibiotics, ozone activity is non-specific and does not depend on microbial replication, thereby reducing the risk of resistance development.

Of relevance to both prosthetic joint infections and chronic ulcer-related infections is the ability of ozone to disrupt microbial biofilms. Biofilm formation on prosthetic surfaces and within chronic wounds represents a major obstacle to infection eradication, as microorganisms embedded in biofilm matrices are protected from antibiotics and host immune responses. Experimental and clinical studies have demonstrated that ozonated oils are highly effective in disrupting biofilms produced by methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and other pathogens in chronic wound infections, including diabetic foot ulcers [

36].

Clinical evidence in joint and periprosthetic infections remains limited but illustrative. A notable case report described the successful treatment of a chronic septic hip prosthesis using a combination of systemic and intra-articular ozone therapy alongside targeted oral antibiotic therapy, without the need for prosthesis removal or prolonged intravenous antibiotics [

37]. Although anecdotal, this case highlights the potential adjunctive role of ozone in complex scenarios where standard surgical approaches are contraindicated or declined.

Regarding infected skin ulcers, a larger body of evidence supports the adjunctive use of ozone therapy. In systemic sclerosis, local oxygen–ozone therapy has been shown to improve healing of digital ulcers, reduce pain, and accelerate resolution of local infection when combined with standard wound care [

28,

29]. Beyond rheumatologic populations, multiple clinical studies and reviews indicate that ozone therapy—administered topically, via ozonated oils, or systemically—can significantly enhance healing of chronic ulcers, particularly diabetic foot ulcers and refractory leg ulcers [

38,

39,

40,

41]. These benefits are associated with reductions in microbial load, modulation of local inflammation, enhanced antioxidant responses, and promotion of granulation tissue formation.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses further suggest that ozone therapy may increase ulcer healing rates, shorten healing time, and reduce complications such as infection-related amputations in chronic ulcer populations, although heterogeneity in protocols and study quality remains substantial [

39,

40,

41]. Importantly, ozone appears to exert beneficial effects not only through direct antimicrobial action but also by improving local oxygen delivery, microcirculatory function, and redox balance—mechanisms that are particularly relevant in vasculopathy and immunosuppressed rheumatologic patients.

Despite these encouraging findings, it is essential to emphasise that the use of ozone in septic arthritis, prosthetic joint infection, and infected skin ulcers remains adjunctive and investigational. Current evidence does not support the replacement of established surgical, antimicrobial, and wound care strategies. At present, ozone therapy should be considered only within a multidisciplinary framework and in carefully selected cases where standard approaches are insufficient, contraindicated, or declined by the patient.

Future research should focus on well-designed controlled clinical studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of ozone as an adjunct to antibiotics, surgery, and advanced wound care in musculoskeletal and ulcer-related infections. Attention should be given to biofilm disruption, infection clearance rates, wound healing outcomes, and safety in immunocompromised rheumatologic populations. Until such data are available, ozone therapy in joint, periprosthetic, and ulcer-related infections should remain confined to investigational or compassionate-use settings.

10. Medical Ozone in Low Back Pain, Disc Herniation, and Spondyloarthropathies

Low back pain represents one of the leading causes of disability worldwide and encompasses a heterogeneous group of conditions, including mechanical low back pain, intervertebral disc herniation, degenerative spine disease, and inflammatory disorders such as axial spondyloarthritis and ankylosing spondylitis [

42]. In parallel, diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) represents a distinct, non-inflammatory condition characterised by ligamentous ossification and altered spinal biomechanics, frequently associated with chronic pain, stiffness, and functional limitation [

43].

Intervertebral disc herniation and degenerative disc disease are among the most common causes of chronic low back pain. Disc degeneration is characterised by progressive loss of proteoglycans, dehydration of the nucleus pulposus, annular fissures, and structural instability, often accompanied by local inflammatory responses and nerve root compression [

44]. These mechanisms lead to both mechanical and biochemical pain generation, contributing to radiculopathy and chronic disability.

Medical ozone has been extensively investigated as a minimally invasive treatment for discogenic low back pain and lumbar disc herniation. Intradiscal or paravertebral administration of an oxygen–ozone gas mixture induces oxidation of proteoglycans within the nucleus pulposus, resulting in disc dehydration and reduction of disc volume, with subsequent decompression of affected nerve roots [

45,

46]. In addition to its mechanical effects, ozone therapy modulates local inflammatory mediators, reduces periradicular oedema, and improves microcirculatory perfusion, contributing to analgesic and functional benefits [

1].

Multiple clinical studies have demonstrated the efficacy of ozone therapy in lumbar disc herniation. Early prospective and randomised studies showed significant pain relief and functional improvement following intradiscal or intraforaminal ozone injections, with outcomes comparable to surgical discectomy in selected patients and a lower incidence of complications [

45,

46,

47]. A large meta-analysis confirmed that ozone therapy is associated with clinically meaningful reductions in pain and disability and a favourable safety profile when performed by experienced operators [

48].

While the role of ozone therapy is well established in mechanical and discogenic low back pain, its potential relevance extends to inflammatory spinal disorders. In axial spondyloarthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, chronic inflammation of the sacroiliac joints and spine leads to inflammatory back pain, stiffness, progressive structural damage, and reduced mobility [

49]. Although biologic and targeted synthetic therapies effectively control inflammatory activity, a substantial proportion of patients continue to experience persistent axial pain related to secondary degenerative changes, altered spinal biomechanics, and coexisting disc pathology [

50].

In this context, ozone therapy does not target the underlying autoimmune mechanisms of spondyloarthritis and should not be considered a disease-modifying treatment. However, its analgesic, anti-oedematous, and microcirculatory effects may provide symptomatic benefit in carefully selected patients with controlled inflammatory disease but residual mechanical low back pain or radiculopathy. Ozone therapy may therefore be considered as an adjunctive intervention within a multidisciplinary management strategy, without replacing standard immunomodulatory treatments.

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis represents another clinical scenario in which ozone therapy may have a potential symptomatic role. DISH is characterised by flowing ossification of spinal ligaments with preserved intervertebral disc height and absence of sacroiliac erosions, distinguishing it from inflammatory spondyloarthropathies [

43]. Pain and stiffness in DISH are predominantly mechanical in origin, related to reduced spinal flexibility, paraspinal muscle overload, and secondary degenerative changes. In these patients, paravertebral ozone therapy may alleviate pain and muscle spasm by improving local circulation and reducing nociceptive input, without interfering with ligamentous ossification or bone metabolism [

1,

51].

Across these conditions, a shared pathophysiological background involves the interaction between mechanical stress, local inflammation, impaired microcirculation, and pain sensitisation. When administered at controlled medical doses, ozone induces adaptive antioxidant responses and modulates inflammatory pathways, supporting its use primarily as a symptomatic and functional treatment rather than a disease-modifying intervention in inflammatory spinal diseases.

In conclusion, medical ozone therapy is supported by robust clinical evidence for the treatment of discogenic low back pain and lumbar disc herniation. Its role in axial spondyloarthritis and DISH should be considered adjunctive and symptom-oriented, targeting mechanical and microcirculatory contributors to pain rather than underlying disease mechanisms. Future studies should focus on clearly defined patient phenotypes and the integration of ozone therapy into comprehensive, individualised management strategies for mixed inflammatory–degenerative spinal disorders.

11. Discussion

Taken together, the clinical data discussed across the different inflammatory, degenerative, and chronic pain settings highlight a convergent pattern of potential benefit associated with medical ozone therapy, as summarized in [

Table 2]. Across a heterogeneous group of conditions—including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome—a common pathophysiological substrate emerges, characterised by redox imbalance, chronic inflammation, microvascular dysfunction, mitochondrial impairment, and persistent pain or fatigue [

1,

2,

3,

4,

11,

12,

13,

14,

31,

35]. Medical ozone, when administered at low and controlled doses according to established protocols, appears to interact with these shared mechanisms through a unified biological framework based on redox modulation and adaptive cellular responses [

1,

2,

3,

4,

6,

16].

At the molecular level, the biological effects of ozone are best interpreted within the context of hormesis. A transient and well-controlled oxidative stimulus activates endogenous antioxidant and cytoprotective pathways, most notably the Nrf2/heme oxygenase-1 axis, with downstream modulation of inflammatory signalling, endothelial function, and mitochondrial metabolism [

2,

4,

6,

16]. This mechanism distinguishes medical ozone from conventional antioxidant supplementation, which has often failed to demonstrate consistent clinical benefit, and from non-specific immunosuppressive strategies [

2,

3,

4].

In rheumatoid arthritis, the convergence between mechanistic plausibility and controlled clinical data is particularly compelling. Randomised studies combining ozone with methotrexate demonstrate improvements in disease activity, redox balance, and biochemical markers of hepatotoxicity, without compromising safety [

20,

21,

22]. These findings suggest that ozone may enhance therapeutic efficacy while mitigating treatment-related oxidative injury, addressing a major limitation of long-term methotrexate therapy [

18,

21,

22]. Although confirmation in larger, multicentre trials is required, rheumatoid arthritis currently represents the rheumatic disease with the strongest clinical rationale for adjunctive ozone therapy.

In systemic sclerosis, available evidence supports a potential benefit of ozone primarily in vascular manifestations rather than fibrotic disease progression. Improvements in peripheral microcirculation, Raynaud phenomenon, and digital ulcer healing observed with both local and systemic ozone therapies are consistent with its effects on endothelial homeostasis, redox balance, and tissue oxygenation [

5,

17,

28,

29,

30]. Given the limited efficacy of current treatments for systemic sclerosis vasculopathy, these findings are clinically relevant but remain based on relatively small studies that require further validation.

The antimicrobial and anti-biofilm properties of ozone further extend its theoretical applicability to complex infectious complications, such as septic arthritis and prosthetic joint infections in immunosuppressed patients [

36,

37]. However, current evidence in this area remains limited to experimental data and isolated case reports, and ozone should therefore be regarded as an experimental adjunct rather than an alternative to established surgical and antimicrobial strategies.

In this context, clinical experience and studies in infected chronic skin ulcers, especially diabetic foot ulcers [

38,

40,

41], indicate that the antimicrobial and anti-biofilm properties of ozone could be translatable to rheumatologic patients with vasculopathy and impaired wound healing, supporting its consideration as an adjunct to standard wound care.

Osteoarthritis represents a distinct but highly relevant context in which ozone has been most extensively investigated. Multiple randomised controlled trials and a meta-analysis demonstrate that intra-articular ozone provides meaningful pain relief and functional improvement in knee osteoarthritis, with a favourable safety profile [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Although osteoarthritis is not an autoimmune disease, its inflammatory and oxidative components align well with the biological actions of ozone, supporting its consideration as a symptomatic treatment option in selected patients.

Fibromyalgia and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome pose a different challenge, characterised by central sensitisation, fatigue, and complex neuroimmune and metabolic abnormalities. The magnitude and consistency of symptom improvement reported in observational studies, together with emerging randomised evidence in fibromyalgia, suggest that ozone may influence core disease mechanisms such as mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and neuroinflammation [

12,

13,

14,

15,

31]. Nevertheless, the susceptibility of these conditions to placebo effects necessitates cautious interpretation and underscores the need for sham-controlled trials with mechanistic endpoints.

Finally, robust clinical evidence supports the use of medical ozone in discogenic low back pain and lumbar disc herniation [

46,

48], where its mechanical, anti-inflammatory, and microcirculatory effects have consistently translated into pain relief and functional improvement, suggesting a potential adjunctive role in rheumatologic patients with coexisting degenerative or mechanical spinal pain [

42].

Beyond disease-specific applications, evidence from oncology highlights the potential of ozone to mitigate treatment-related toxicities, including chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy and chronic fatigue [

32,

33,

34]. These findings are of translational interest for rheumatology, where long-term immunosuppressive and cytotoxic therapies frequently result in cumulative toxicity, reduced quality of life, and treatment discontinuation. The mechanistic overlap between these clinical contexts supports further exploration of ozone as a supportive therapy in rheumatologic populations.

Several limitations of the current evidence base must be acknowledged. Many studies are small, single-centre, or observational, and heterogeneity in ozone concentrations, administration routes, and treatment schedules complicates comparison across studies. Blinding is often absent, particularly in chronic pain and fatigue conditions. Long-term safety data in heavily immunosuppressed rheumatologic patients are limited. These factors highlight the need for well-designed, adequately powered randomised controlled trials with standardised protocols and integrated mechanistic assessments. Key safety considerations, methodological limitations, and current research gaps emerging from the available literature are outlined in [

Table 3].

In conclusion, medical ozone occupies an emerging position at the intersection of redox biology, immunomodulation, and vascular and mitochondrial medicine. While current evidence does not support routine clinical implementation, the convergence of mechanistic rationale and clinical signals across multiple rheumatologic conditions justifies further rigorous investigation. If validated by future trials, medical ozone could represent a valuable adjunctive strategy to address residual disease activity, chronic pain, fatigue, and treatment-related toxicity in rheumatology.

12. Conclusions

Medical ozone therapy represents an emerging adjunctive approach in rheumatology, supported by a coherent biological rationale based on redox modulation, microvascular improvement, and regulation of inflammatory and mitochondrial pathways. Across a range of inflammatory, degenerative, and chronic pain conditions—including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis–related vasculopathy, osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, and ME/CFS—available evidence suggests potential clinical benefits, particularly in the management of pain, fatigue, vascular complications, and treatment-related toxicity. Robust data support its use in discogenic low back pain, whereas applications in inflammatory spinal disease and infectious complications should be considered investigational and adjunctive only. Despite encouraging clinical signals, heterogeneity of treatment protocols and limited high-quality randomised trials currently preclude routine clinical implementation. Future multicentre studies with standardised dosing, clearly defined indications, and rigorous safety monitoring are required to establish the role of medical ozone within evidence-based rheumatologic care.

Funding

This work received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges colleagues and collaborators for their valuable scientific discussions and constructive feedback during the development of this review.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflicts of interest.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Artificial intelligence tools were used to support language editing, translation, and the organization of tables and graphical content. The use of these tools was limited to improving clarity, structure, and readability. All scientific content, data interpretation, and final decisions remain the sole responsibility of the author.:

References

- Bocci, V. OZONE: A New Medical Drug; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2011; ISBN 978-90-481-9233-5. [Google Scholar]

- Franzini, M.; Valdenassi, L.; Pandolfi, S.; Tirelli, U.; Ricevuti, G.; Chirumbolo, S. The Role of Ozone as an Nrf2-Keap1-ARE Activator in the Anti-Microbial Activity and Immunity Modulation of Infected Wounds. Antioxid. Basel Switz. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viebahn-Hänsler, R.; León Fernández, O.S.; Fahmy, Z. Ozone in Medicine: Clinical Evaluation and Evidence Classification of the Systemic Ozone Applications, Major Autohemotherapy and Rectal Insufflation, According to the Requirements for Evidence-Based Medicine. Ozone Sci. Eng. 2016, 38, 322–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, L.; Martínez-Sánchez, G.; Bordicchia, M.; Malcangi, G.; Pocognoli, A.; Morales-Segura, M.A.; Rothchild, J.; Rojas, A. Is Ozone Pre-Conditioning Effect Linked to Nrf2/EpRE Activation Pathway in Vivo? A Preliminary Result. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 742, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowicka, D. Thermography Improves Clinical Assessment in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis Treated with Ozone Therapy. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 5842723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocci, V.; Aldinucci, C.; Mosci, F.; Carraro, F.; Valacchi, G. Ozonation of Human Blood Induces a Remarkable Upregulation of Heme Oxygenase-1 and Heat Stress Protein-70. Mediators Inflamm. 2007, 2007, 26785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noori-Zadeh, A.; Bakhtiyari, S.; Khooz, R.; Haghani, K.; Darabi, S. Intra-Articular Ozone Therapy Efficiently Attenuates Pain in Knee Osteoarthritic Subjects: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 42, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus, C.C.L.; dos Santos, F.C.; de Jesus, L.M.O.B.; Monteiro, I.; Sant’Ana, M.S.S.C.; Trevisani, V.F.M. Comparison between Intra-Articular Ozone and Placebo in the Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Study. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0179185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkyılmaz, G.G.; Bakır, M.; Atıcı, Ş.R. The Effect of Intra-Articular Ozone Injection on Pain and Physical Function in Knee Osteoarthritis: A Prospective Study. J. Clin. Med. Kazakhstan 2020, 6, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arjmanddoust, Z.; Nazari, A.; Moezy, A. Efficacy of Two Doses of Intra-Articular Ozone Therapy for Pain and Functional Mobility in Knee Osteoarthritis: A Double-Blind Randomized Trial. Adv. Rheumatol. Lond. Engl. 2025, 65, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirelli, U.; Cirrito, C.; Pavanello, M. Ozone Therapy Is an Effective Therapy in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Result of an Italian Study in 65 Patients. Ozone Ther. 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirelli, U.; Cirrito, C.; Pavanello, M.; Piasentin, C.; Lleshi, A.; Taibi, R. Ozone Therapy in 65 Patients with Fibromyalgia: An Effective Therapy. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 1786–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirelli, U. Oxygen-Ozone Therapy Is an Effective Therapy in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Results in 100 Patients. Biomed. J. Sci. Tech. Res. 2019, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirelli, U.; Franzini, M.; Valdenassi, L.; Pandolfi, S.; Berretta, M.; Ricevuti, G.; Chirumbolo, S. Patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) Greatly Improved Fatigue Symptoms When Treated with Oxygen-Ozone Autohemotherapy. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Fernández, A.; Macías-García, L.; Valverde-Moreno, R.; Ortiz, T.; Fernández-Rodríguez, A.; Moliní-Estrada, A.; De-Miguel, M. Autohemotherapy with Ozone as a Possible Effective Treatment for Fibromyalgia. Acta Reumatol. Port. 2019, 44, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Roche, L.; Riera-Romo, M.; Mesta, F.; Hernández-Matos, Y.; Barrios, J.M.; Martínez-Sánchez, G.; Al-Dalaien, S.M. Medical Ozone Promotes Nrf2 Phosphorylation Reducing Oxidative Stress and Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in Multiple Sclerosis Patients. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 811, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluccio, F. Rapid and Sustained Effect of Ozone Major Autohemotherapy for Raynaud and Hand Edema in Systemic Sclerosis Patient: A Case Report. Cureus 2022, 14, e31831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taşçi Bozbaş, G.; Yilmaz, M.; Paşaoğlu, E.; Gürer, G.; Ivgin, R.; Demirci, B. Effect of Ozone in Freund’s Complete Adjuvant-Induced Arthritis. Arch. Rheumatol. 2018, 33, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León Fernández, O.S.; Viebahn-Haensler, R.; Cabreja, G.L.; Espinosa, I.S.; Matos, Y.H.; Roche, L.D.; Santos, B.T.; Oru, G.T.; Polo Vega, J.C. Medical Ozone Increases Methotrexate Clinical Response and Improves Cellular Redox Balance in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 789, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (PDF) Medical Ozone Reduces the Risk of γ-Glutamyl Transferase and Alkaline Phosphatase Abnormalities and Oxidative Stress in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients Treated with Methotrexate. ResearchGate 2025. [CrossRef]

- Oru, G.T.; Viebahn-Haensler, R.; Fernández, E.G.; Almiñaque, D.A.; Vega, J.C.P.; Santos, B.T.; Cabreja, G.L.; Espinosa, I.S.; Nápoles, N.T.; Fernández, O.S.L. Medical Ozone Effects and Innate Immune Memory in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients Treated with Methotrexate+Ozone After a Second Cycle of Ozone Exposure. Chronic Pain Manag. J. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- León Fernández, O.S.; Oru, G.T.; Viebahn-Haensler, R.; López Cabreja, G.; Serrano Espinosa, I.; Corrales Vázquez, M.E. Medical Ozone: A Redox Regulator with Selectivity for Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Pharm. Basel Switz. 2024, 17, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanzi, L.; Braschi, F.; Fiori, G.; Galluccio, F.; Miniati, I.; Guiducci, S.; Conforti, M.-L.; Kaloudi, O.; Nacci, F.; Sacu, O.; et al. Digital Ulcers in Scleroderma: Staging, Characteristics and Sub-Setting through Observation of 1614 Digital Lesions. Rheumatol. Oxf. Engl. 2010, 49, 1374–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluccio, F.; Allanore, Y.; Czirjak, L.; Furst, D.E.; Khanna, D.; Matucci-Cerinic, M. Points to Consider for Skin Ulcers in Systemic Sclerosis. Rheumatol. Oxf. Engl. 2017, 56, v67–v71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluccio, F.; Matucci-Cerinic, M. Two Faces of the Same Coin: Raynaud Phenomenon and Digital Ulcers in Systemic Sclerosis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2011, 10, 241–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluccio, F.; Matucci-Cerinic, M. Registry Evaluation of Digital Ulcers in Systemic Sclerosis. Int. J. Rheumatol. 2010, 2010, 363679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiori, G.; Galluccio, F.; Braschi, F.; Amanzi, L.; Miniati, I.; Conforti, M.L.; Del Rosso, A.; Generini, S.; Candelieri, A.; Magonio, A.; et al. Vitamin E Gel Reduces Time of Healing of Digital Ulcers in Systemic Sclerosis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2009, 27, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hassanien, M.; Rashad, S.; Mohamed, N.; Elawamy, A.; Ghaly, M.S. Non-Invasive Oxygen-Ozone Therapy in Treating Digital Ulcers of Patients with Systemic Sclerosis. Acta Reumatol. Port. 2018, 43, 210–216. [Google Scholar]

- Riva, H.; Balestra, B.; Giannini, O.; Bonforte, G. Treatment of Digital Ulcers with Oxygen-Ozone Therapy in a Patient with Systemic Sclerosis. Ozone Ther. 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaymaz, S.; Karasu, U.; Alkan, H.; Ulutaş, F.; Albayrak Yaşar, C.; Dündar Ök, Z.; Çobankara, V.; Yiğit, M.; Yıldız, N.; Ardıç, F. Efficacy of Local Oxygen-Ozone Therapy for the Treatment of Digital Ulcer Refractory to Medical Therapy in Systemic Sclerosis: A Randomized Controlled Study. Mod. Rheumatol. 2022, 32, 1102–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirelli, U.; Cirrito, C.; Pavanello, M. Ozone Therapy in 40 Patients with Fibromyalgia: An Effective Therapy. Ozone Ther. 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavo, B.; Rodríguez-Esparragón, F.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Martínez-Sánchez, G.; Llontop, P.; Aguiar-Bujanda, D.; Fernández-Pérez, L.; Santana-Rodríguez, N. Modulation of Oxidative Stress by Ozone Therapy in the Prevention and Treatment of Chemotherapy-Induced Toxicity: Review and Prospects. Antioxid. Basel Switz. 2019, 8, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavo, B.; Cánovas-Molina, A.; Ramallo-Fariña, Y.; Federico, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Galván, S.; Ribeiro, I.; Marques da Silva, S.C.; Navarro, M.; González-Beltrán, D.; et al. Effects of Ozone Treatment on Health-Related Quality of Life and Toxicity Induced by Radiotherapy and Chemotherapy in Symptomatic Cancer Survivors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clavo, B.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Galván, S.; Federico, M.; Martínez-Sánchez, G.; Ramallo-Fariña, Y.; Antonelli, C.; Benítez, G.; Rey-Baltar, D.; Jorge, I.J.; et al. Long-Term Improvement by Ozone Treatment in Chronic Pain Secondary to Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy: A Preliminary Report. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 935269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirelli, U.; Cirrito, C.; Pavanello, M.; Del Pup, L.; Lleshi, A.; Berretta, M. Oxygen-Ozone Therapy as Support and Palliative Therapy in 50 Cancer Patients with Fatigue - A Short Report. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 8030–8033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.; Peirone, C.; Amaral, J.S.; Capita, R.; Alonso-Calleja, C.; Marques-Magallanes, J.A.; Martins, Â.; Carvalho, Á.; Maltez, L.; Pereira, J.E.; et al. High Efficacy of Ozonated Oils on the Removal of Biofilms Produced by Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) from Infected Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Mol. Basel Switz. 2020, 25, 3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowen, R.J. Ozone Therapy in Conjunction with Oral Antibiotics as a Successful Primary and Sole Treatment for Chronic Septic Prosthetic Joint: Review and Case Report. Med. Gas Res. 2018, 8, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, E.; Holland, O.J.; Vanderlelie, J.J. Ozone Therapy for the Treatment of Chronic Wounds: A Systematic Review. Int. Wound J. 2018, 15, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvis, A.M.; Ekta, J.S. Ozone Therapy: A Clinical Review. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2011, 2, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wainstein, J.; Feldbrin, Z.; Boaz, M.; Harman-Boehm, I. Efficacy of Ozone-Oxygen Therapy for the Treatment of Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2011, 13, 1255–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Sánchez, G.; Al-Dalain, S.M.; Menéndez, S.; Re, L.; Giuliani, A.; Candelario-Jalil, E.; Alvarez, H.; Fernández-Montequín, J.I.; León, O.S. Therapeutic Efficacy of Ozone in Patients with Diabetic Foot. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2005, 523, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, D.; March, L.; Brooks, P.; Blyth, F.; Woolf, A.; Bain, C.; Williams, G.; Smith, E.; Vos, T.; Barendregt, J.; et al. The Global Burden of Low Back Pain: Estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 968–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, D.; Niwayama, G. Radiographic and Pathologic Features of Spinal Involvement in Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis (DISH). Radiology 1976, 119, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.A.; Roughley, P.J. What Is Intervertebral Disc Degeneration, and What Causes It? Spine 2006, 31, 2151–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreula, C.F.; Simonetti, L.; De Santis, F.; Agati, R.; Ricci, R.; Leonardi, M. Minimally Invasive Oxygen-Ozone Therapy for Lumbar Disk Herniation. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2003, 24, 996–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Gallucci, M.; Limbucci, N.; Zugaro, L.; Barile, A.; Stavroulis, E.; Ricci, A.; Galzio, R.; Masciocchi, C. Sciatica: Treatment with Intradiscal and Intraforaminal Injections of Steroid and Oxygen-Ozone versus Steroid Only. Radiology 2007, 242, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelekis, A.; Bonaldi, G.; Cianfoni, A.; Filippiadis, D.; Scarone, P.; Bernucci, C.; Hooper, D.M.; Benhabib, H.; Murphy, K.; Buric, J. Intradiscal Oxygen-Ozone Chemonucleolysis versus Microdiscectomy for Lumbar Disc Herniation Radiculopathy: A Non-Inferiority Randomized Control Trial. Spine J. Off. J. North Am. Spine Soc. 2022, 22, 895–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steppan, J.; Meaders, T.; Muto, M.; Murphy, K.J. A Metaanalysis of the Effectiveness and Safety of Ozone Treatments for Herniated Lumbar Discs. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. JVIR 2010, 21, 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, J.; Sieper, J. Ankylosing Spondylitis. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2007, 369, 1379–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrey, M.N.; Mease, P.J. Pain in Axial Spondyloarthritis: More to It Than Just Inflammation. J. Rheumatol. 2021, 48, 1632–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jaziri, A.A.; Mahmoodi, S.M. Painkilling Effect of Ozone-Oxygen Injection on Spine and Joint Osteoarthritis. Saudi Med. J. 2008, 29, 553–557. [Google Scholar]

Table 1.

Pathophysiological targets of medical ozone therapy in rheumatologic conditions.

Table 1.

Pathophysiological targets of medical ozone therapy in rheumatologic conditions.

| Pathophysiological process |

Role in rheumatic diseases |

Effects of medical ozone |

| Oxidative stress |

Sustains inflammation, tissue damage, and mitochondrial dysfunction |

Activation of endogenous antioxidant systems via Nrf2/HO-1 pathway |

| Chronic inflammation |

Drives synovitis, fibrosis, and pain |

Modulation of NF-κB signaling and pro-inflammatory cytokines |

| Endothelial dysfunction |

Impairs microcirculation and tissue perfusion |

Improved endothelial function and vasoprotection |

| Microvascular damage |

Contributes to Raynaud phenomenon and digital ulcers |

Enhanced microcirculation and oxygen delivery |

| Mitochondrial dysfunction |

Associated with fatigue and pain syndromes |

Improved mitochondrial efficiency and redox balance |

Table 2.

Summary of clinical evidence supporting the use of medical ozone therapy in rheumatologic and related conditions.

Table 2.

Summary of clinical evidence supporting the use of medical ozone therapy in rheumatologic and related conditions.

Condition

Clinical setting

|

Route of administration |

Study design |

Main clinical outcomes |

Level of evidence |

| Rheumatoid arthritis |

Rectal insufflation (adjunct to methotrexate) |

Randomized controlled trials |

↓ Disease activity, ↓ oxidative stress, ↓ hepatotoxicity |

Moderate |

| Systemic sclerosis (vasculopathy) |

Local bagging; major autohemotherapy |

RCTs, observational studies |

↑ Digital ulcer healing, ↓ Raynaud severity |

Low–moderate |

| Knee osteoarthritis |

Intra-articular injection |

RCTs, meta-analyses |

↓ Pain, ↑ function |

Moderate–high |

| Fibromyalgia |

Major autohemotherapy |

RCTs, observational studies |

↓ Pain, ↓ fatigue, ↑ quality of life |

Low–moderate |

| ME/CFS |

Major autohemotherapy |

Observational studies |

↓ Fatigue severity |

Low |

| Discogenic low back pain |

Intradiscal / paravertebral injection |

RCTs, meta-analyses |

↓ Pain, ↑ function |

High |

| Axial spondyloarthritis (residual mechanical pain) |

Paravertebral injection |

Observational studies |

↓ Pain, ↑ functional mobility |

Low |

| Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) |

Paravertebral injection |

Observational studies |

↓ Mechanical pain, ↓ stiffness |

Low |

| Treatment-related toxicity (immunosuppressive / cytotoxic therapies) |

Major autohemotherapy |

Observational studies |

↓ Fatigue, ↓ neuropathic pain, ↑ quality of life |

Low |

| Chronic ulcers and joint-related infections (adjunctive use) |

Local ozone; systemic ozone |

Case series, experimental studies |

↑ Healing rate, ↓ infection burden |

Very low |

Table 3.

Safety profile, limitations, and research gaps of medical ozone therapy in rheumatology.

Table 3.

Safety profile, limitations, and research gaps of medical ozone therapy in rheumatology.

| Aspect |

Current evidence |

| Overall safety |

Favourable when administered according to certified medical protocols |

| Common adverse effects |

Mild, transient local discomfort |

| Serious adverse events |

Rare; mainly related to improper administration |

| Protocol heterogeneity |

High variability in dose, route, and frequency |

| Long-term safety data |

Limited in immunosuppressed populations |

| Research gaps |

Need for large multicentre randomized trials with standardized protocols |

|