Submitted:

22 December 2025

Posted:

23 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Context of Sustainable Urban Mobility in the Climate Crisis

1.2. Introduction to the Sunglider Concept: Solar-Powered, Elevated Mobility Solution

1.3. Objectives of the Paper

- Estimate the technological viability of the Sunglider system, with a focus on renewable energy integration, modular design, and intelligent transport applications. This includes assessing its potential contribution to zero-emission mobility, climate resilience, and energy efficiency.

- Consider the urban design qualities of the infrastructure, including spatial integration, accessibility, safety, and experiential dimensions. This involves exploring how the elevated structure interfaces with public space, contributes to urban beauty, and enhances multimodal connectivity.

-

Map the Sunglider’s alignment with the NEB Compass, using its three core axes:

- Sustainability: climate-neutrality, circularity, and biodiversity support.

- Aesthetics and quality of experience: cultural and sensory dimensions of design, architectural quality, and meaningfulness.

- Inclusion: social equity, accessibility, and citizen participation in design and use.

- Discuss broader policy and planning implications, considering how Sunglider-like systems could be scaled or adapted to different urban and regional contexts within Europe and beyond.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. New European Bauhaus Compass Principles

- Sustainability: This principle extends beyond carbon neutrality to include circular economy principles, biodiversity conservation, and environmental stewardship. It encourages designs and systems that are energy-efficient, resource-responsible, and resilient to climate risks.

- Aesthetics and Quality of Experience: NEB emphasizes the cultural, sensory, and emotional dimensions of design. Aesthetics are not limited to visual appeal but include how spaces feel, sound, and support human well-being. Quality of experience also relates to craftsmanship, heritage, and beauty in innovation.

- Inclusion: Central to the NEB vision is the creation of spaces and systems that are equitable, participatory, and accessible to all. This principle underscores the importance of involving diverse communities in design processes and ensuring that outcomes reflect pluralistic needs, including those of marginalized or vulnerable groups.

- Sustainable mobility infrastructure, where aesthetic and inclusive design is essential to promote modal shift.

- Urban regeneration and architecture, encouraging adaptive reuse, biophilic design, and low-carbon materials.

- Civic participation, with emphasis on co-design and community-led initiatives.

2.2. Urban Mobility & Infrastructure Innovation

2.3. Technological Framework of Sunglider

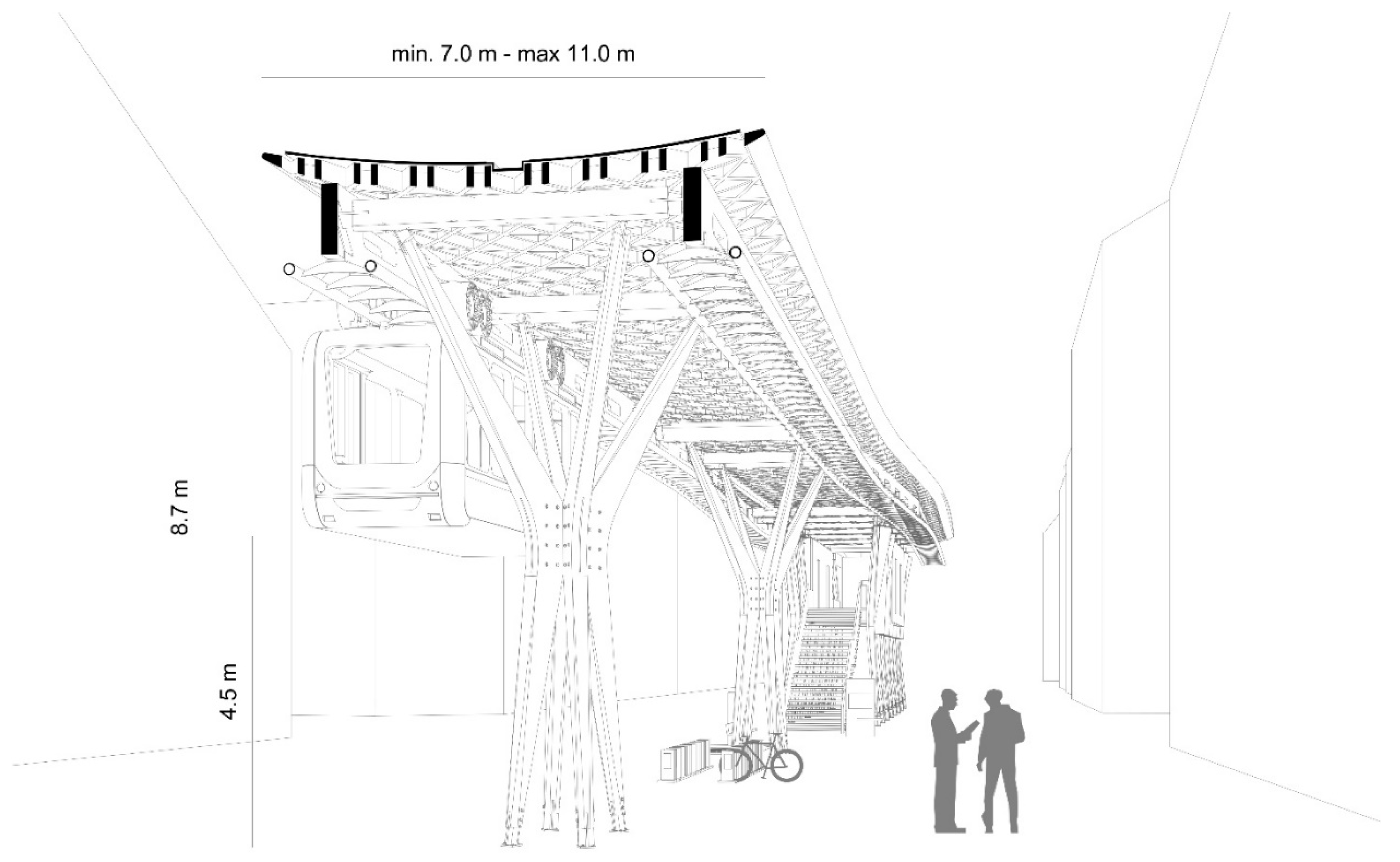

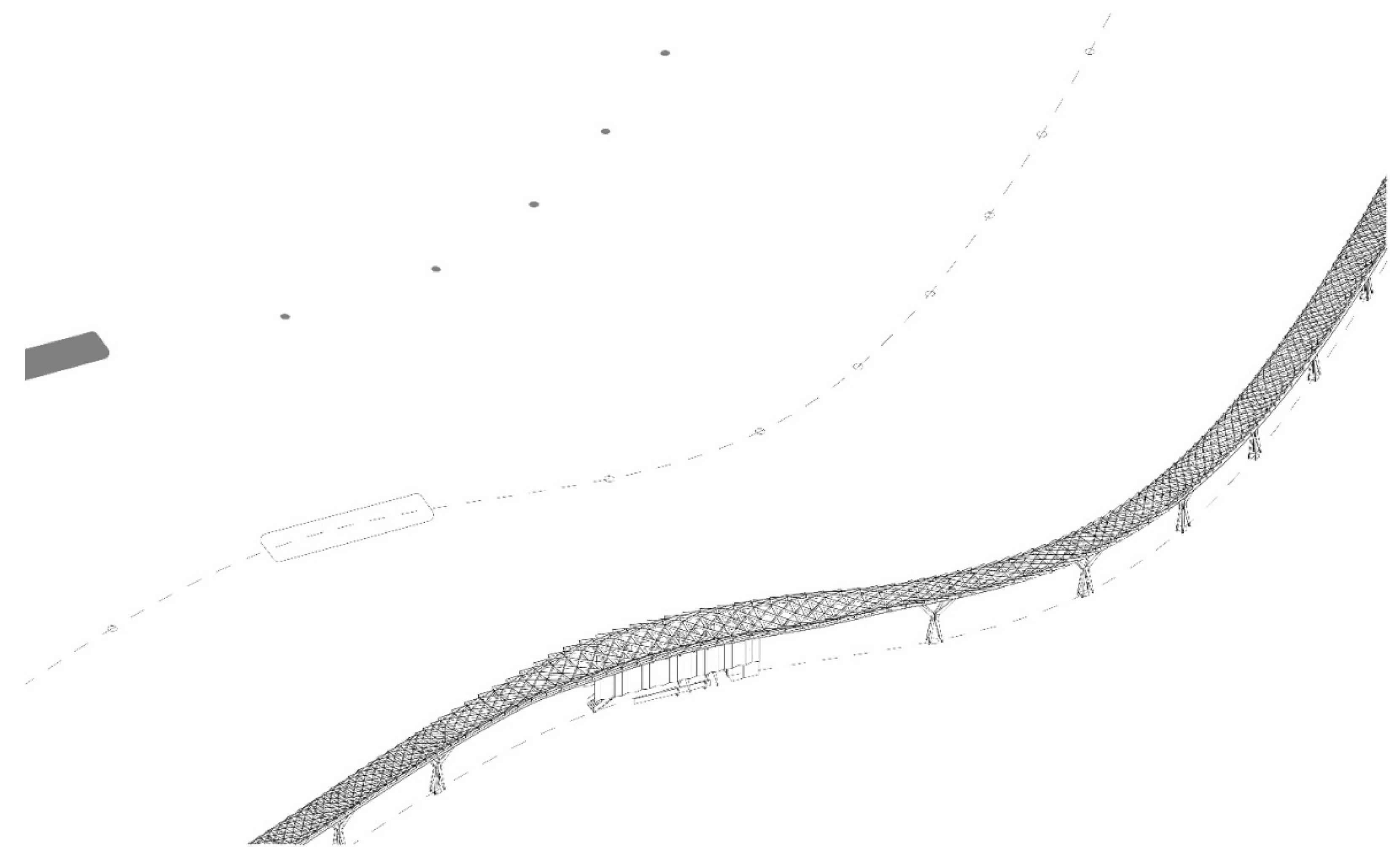

2.3.1. Structural Innovation

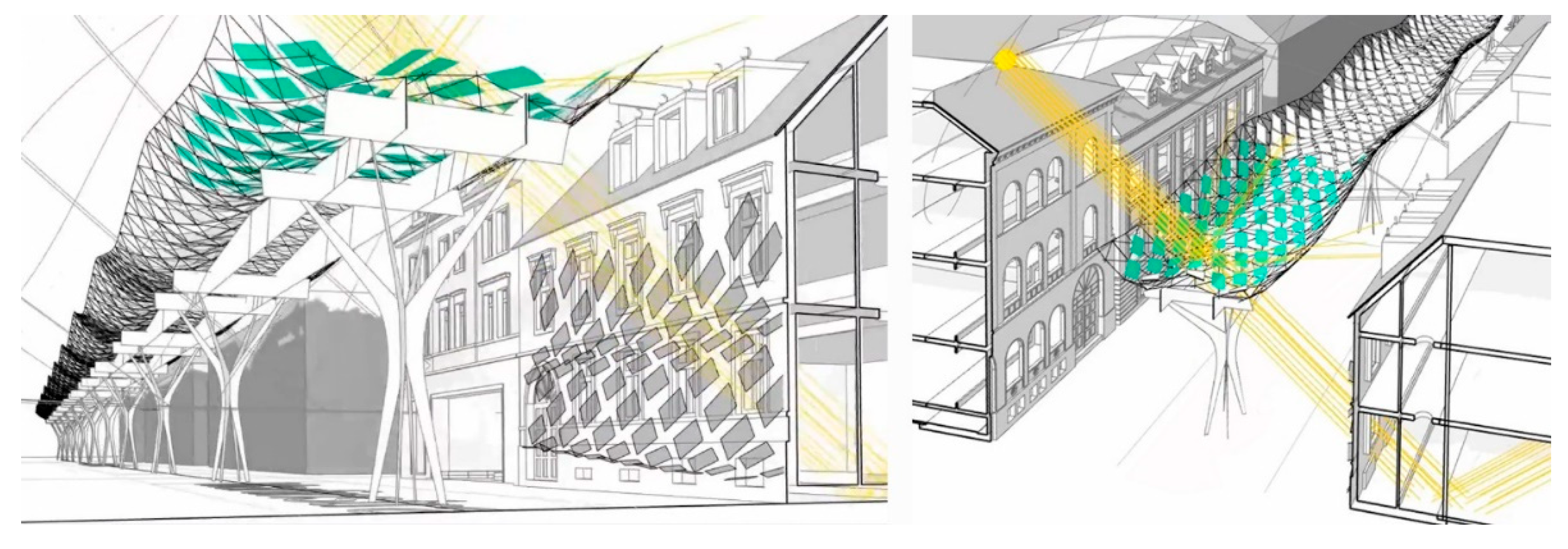

2.3.2. Energy & Environmental Performance

2.4. Safety and Climate Resilience

3. Urban & Spatial Integration

3.1. Land Use and Urban Impact

3.2. Connectivity & Urban Morphology

3.3. Spatial Experience and Aesthetics

4. Evaluation Through the NEB Compass

4.1. Sustainability

4.2. Inclusion

4.3. Aesthetics and Experience

5. Critical Discussion

5.1. Strengths. Scalability, Innovation, and Alignment with NEB Values

- Modular scalability for varying urban contexts

- Technological innovation (ITS, PV integration)

- Alignment with NEB values

5.2. Risks and Implementation Barriers

- Costs: At ‚ā¨3.14 million/km, Sunglider requires significant upfront investment.

- Implementation and governance complexity. Political Feasibility

- Urban integration challenges: In historic cores, concerns about privacy, heritage impact, and visual intrusion must be mitigated (e.g., with screening, careful alignment, barrier-free access).

5.3. Replicability

6. Conclusion

- Dynamic simulations of vehicle energy loads, seasonal performance, and station accessibility.

- Lifecycle and cost–benefit assessments comparing Sunglider to metro, tram, and bike highway systems.

- Field-based studies evaluating public acceptance, visual integration, and policy feasibility.

6.1. Implications

- Multifunctional (mobility + energy generation),

- Intermodally integrated,

- Visually expressive, and

- Climate-adaptive.

6.2. Future Research

- Pilot testing in diverse urban contexts - especially in medium-sized and polycentric cities - to evaluate scalability, social acceptance, and local adaptation.

- Techno-economic modeling to quantify lifecycle costs, emissions savings, and return on investment relative to other transit modes.

- Governance frameworks for cross-sector collaboration (energy, mobility, planning) and inclusive public participation.

- Design research exploring spatial aesthetics, urban integration, and user experience across different geographies.

6.3. Final Thought

References

- UN-Habitat, World Cities Report 2022 URL https://unhabitat.org/wcr/2022/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- International Energy Agency IEA Transport URL https://www.iea.org/energy-system/transport (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- WHO () Sustainable transport for health. World Health Organization 2021. URL: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HEP-ECH-AQH-2021.6 (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Banister D. The sustainable mobility paradigm. In Transport Policy, 15(2), 2008; pp 73–80.

- Newman P. and Kenworthy J., The End of Automobile Dependence Island Press 2015.

- European Commission, Sustainable and Smart Mobility Strategy. COM/2020/789 final URL https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=COM:2020:789:FIN (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- European Commission The New European Bauhaus: Beautiful, Sustainable, Together 2021 URL https://new-european-bauhaus.europa.eu/index_en (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- 8. Design Award Agency. Sunglider – Smart Überground Metro Designed by Peter Kuczia, 2023 URL https://www.designawardagency.com/post/sunglider-smart-uberground-metro-designed-by-peter-kuczia-sunglider (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- 9. Muse International Charting the Future with Sunglider 2023; URL https://muse.international/index/charting-the-future-with-sunglider-smart-uberground-metro/ (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Kuczia, P. Sunglider. In: Lorenz, D. and Staiger, F. (eds.), Nachhaltige Mobilität, Springer Vieweg 2023, pp. 647–660.

- European Commission The New European Bauhaus Compass 2022; URL https://new-european-bauhaus.europa.eu/system/files/2023-01/NEB_Compass_V_4.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- European Commission, New European Bauhaus Progress Report 2022; URL https://new-european-bauhaus.europa.eu/about/progress-report_en (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Shaheen S. and Cohen A. Shared Micromobility Policy Toolkit, UC Berkeley 2019.

- Papa, E. and Ferreira, A. Sustainable Accessibility and the Implementation of Automated Vehicles: Identifying Critical Decisions Urban Science 2018, 2(1), 5; (accessed on 21 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Duarte F. and Ratti C., The impact of autonomous vehicles on cities: A review. In Journal of Urban Technology, 25(4) 2018, pp. 3–18.

- Lindner C. and Rosa B. Deconstructing the High Line, Rutgers University Press 2017.

- Rueda, S., Superblocks for the design of new cities. In: Designing Sustainable Cities. Springer 2019.

- Behling, S., Solar Architecture and Industrial Design, Springer 2009.

- Bertolini, L. Planning the Mobile Metropolis: Transport for People, Places and the Planet, Palgrave Macmillan 2017.

- Gehl, J., Cities for People, Island Press 2010.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).