1. Introduction

Urban public space increasingly presents itself as a design challenge for cities due to the changing demands produced by climate change and the rapid social and technological transformations currently taking place. While climate change is a holistic phenomenon occurring on a planetary scale, its effects are felt locally, close to citizens. These effects are perceived in outdoor spaces as much or more than indoors, forcing the search for immediate solutions and elevating the redesign of cities' outdoor spaces to a level of urgency and prominence [

1].

Adaptation strategies for urban spaces in response to climate change must also address the inherent rigidity of the built environment, which is often characterized by a lack of flexibility. This inflexibility stems from urban structures and spatial configurations that were originally designed to accommodate the environmental and social demands of a pre-climate-change era, thereby limiting their capacity to respond effectively to evolving climatic conditions within a given context. Urban buildings, streets, and squares are, by definition, difficult to adapt and repurpose. Furthermore, the very nature of urban planning regulations and their drafting and approval processes develop at a slow pace that cannot easily adapt to the fast-changing needs of society and natural environmental conditions in the context of a rapidly changing climate [

2,

3].

Increasingly, the lack of interdisciplinary collaboration in the formulation of urban strategies remains a significant barrier to the effective design and development of sustainable and liveable cities. Disciplinary fragmentation in urban planning and the absence of a long-term holistic vision hinders the transition toward more sustainable cities [

4,

5,

6]. A multi-disciplinary approach to research and practice in urban design and architecture may be critical for effectively addressing these challenges. [

7] emphasizes the need for a transdisciplinary approach in urban design research and practice to address public health challenges in cities. Collaboration among architects, urban planners, designers, sociologists, epidemiologists, and other professionals is essential to understanding and addressing the complex interactions between the built environment, human behaviour, and health in cities [

1].

Urban resilience in architecture as a way to react to climate change, regarding both mitigation and adaptation, often focuses on monitoring energy consumption in buildings and reducing CO2 emissions in infrastructure and transportation. These actions are mainly addressed through the implementation of IT solutions that help collect data and the improvement of building envelopes and facilities, skipping the evident urge to redesign the very shape and components of the common open urban space, the common shared living rooms of cities. To date, climate change adaptation in the urban environment has primarily focused on the problem of increased solar radiation and temperature in public spaces. Other types of adaptation strategies are being implemented, particularly for disaster prevention and sea-level rise, among others. However, on a local scale, there is an urgent need to define urban intervention methods and processes that address climate change in a more holistic, multifaceted, and organized manner [

8,

9].

The example of climate shelters (i.e. public spaces that provide thermal comfort to the most vulnerable inhabitants see [

10] implemented in cities such as Barcelona and Bilbao [

11,

12] seems promising. However, mapping and repurposing existing buildings, parks, and spaces does not seem sufficient as a long-term solution [

8]. At the same time, the use of Nature-based Solutions (NbS) in the search for and implementation of climate adaptation is on the rise. Again, it is still unclear how such solutions can be effective in the lack of long-term planning and evaluation of their integration with and impact on the local communities they are meant to serve [

13,

14,

15]. Maladaptation is a concrete risk, and efforts made to prevent the effects of climate change end up making people and places even more vulnerable to such effects [

16]. Taking into account the intangible layers of the urban space e.g. people’s interactions with other human and non-human actors, an ecological, multi-sensory approach to human perception of space, and the engagement of residents in adapting the city’s space to climate change are becoming key factors, moving forward, for a successful climate adaptation [

1].

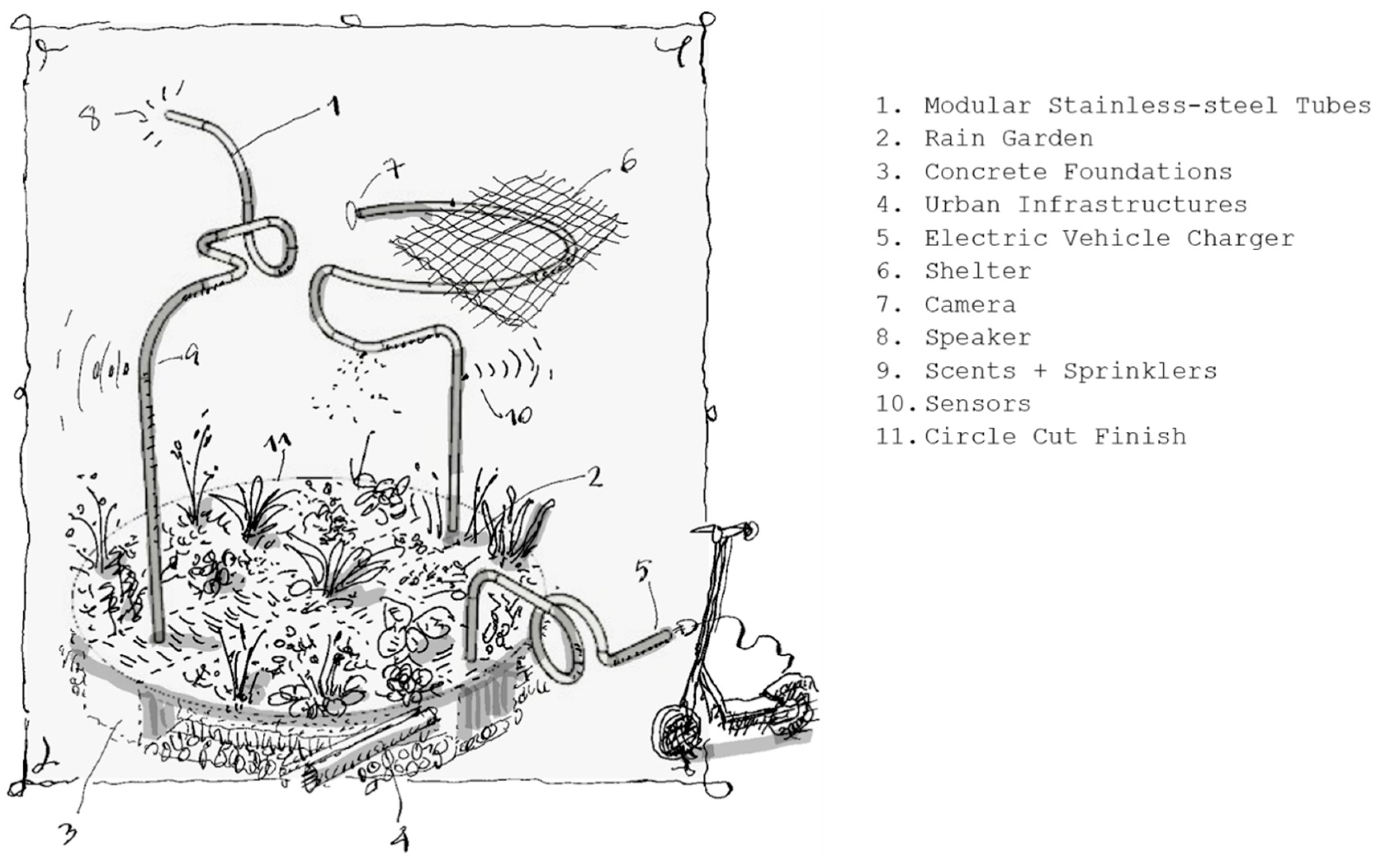

In this article, we present the design process and definition of a novel modular, multi-sensory Nature-based-Solution (NbS) for adaptive urban furniture for the city space. The solution - called

Urban Oasis - resulted in an industrial patent (Utility Model U243580ES) and primarily aims at providing a multifunctional urban infrastructure that integrates rain gardens within paved urban areas designed to capture, filter, and manage rainwater to help mitigate urban flooding and reduce heat island effects.

Urban Oasis also incorporates modular tubular supports that house urban functional features, such as climate sensors, irrigation systems, lighting, and electric vehicle chargers, contributing to climate change adaptation and urban resilience. It is the main outcome of the research project “Urban Furniture for a Sustainable and Egalitarian City" [

17] jointly funded by the Basque Government, the University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU, and the private company Transformados Metáliscos S.L. between 2022 and 2024. The research project aligns with SDG11, "Sustainable Cities and Communities," and is part of the University-Industry-Society collaboration program involving the architecture and engineering departments of UPV/EHU, along with invited artists and researchers. The project's global objective is the design and development of urban furniture as an adaptive system that takes into account current social, technological, and climatic challenges for the entire life cycle of the product, from the preliminary analysis and design to the development and implementation process.

In the course of the project, the importance of climatic, environmental, and sustainable factors as emerged from the collection of both quantitative and qualitative data (see [

17]), repositioned the research from an initial investigation on the possibilities of f urban furniture in a changing urban realm to the definition of solutions for urban climate change adaptation. From the first phase of the research, a Design Checklist emerged as the first element of a framework that supports designers toward the definition of more sustainable, equitable, and climate-adaptable urban solutions. In this article, we describe how

Urban Oasis aligns with the Design Checklist and integrates the different tangible and intangible layers that concur in shaping our current - and future - experience of the urban space in the context of climate adaptation.

2. Materials and Methods: Practice-Based Research

The challenges highlighted in the previous section require renewed research methodologies that can inform the definition of efficient and effective strategies for climate change adaptation and the rethinking of public space design. Likely, if we do not change the way we ask questions, we will not find new answers. To this end, in our research, we adopted practice-based research as the reference framework to first formalize the guiding questions of the study and later guide the design of the new solution. Practice-based research and Research through Design (RtD) are a methodological process in urban and landscape design that involves formulating research questions and engaging in iterative design processes. These processes include testing of design alternatives to ensure the validity and robustness of the design outcomes. The knowledge generated through RtD is embodied in the final design artifacts, which can be either site-specific solutions or replicable design principles applicable to multiple contexts [

18]. Such an approach is, in our belief, of the utmost importance especially in the fields of architecture and urban design as it vindicates practice-based research as a valid form of inquiry. In this sense, advocating for a

designerly way of knowing [

19] in architecture and urban studies is key to systematically leverage the very act of designing as a research method and a legitimate way of inquiring and researching.

Table 1 illustrates the different relationships between traditional normative research and design as a form of research [

20].

In the words of Giaccardi and Stappers "

In the generative process of ideation, concept development, and making that brought this prototype into existence, the designers have struggled with opportunities and constraints, with implications of theoretical goals/constructs, and the confrontation between these and the empirical realities in the world. In other words, any designer involved with the prototype will have had to navigate around the real-world obstacles that got in the way of building the best bridge between the product and its user." [

20], [Section 41.1.4].

In this article we describe the second phase of a research project where the balance between theoretical and practical investigation was essential. In the first phase, we defined the theoretical framework for the design of solutions that address climate adaptation in urban space [

1,

17] the research questions and goals. We then conducted a qualitative and quantitative study which included keywords analysis, expert interviews, and case studies analysis, which helped us define a Design Checklist (see

Section 2.2) as a tool to inform the conceptualization, design, and implementation of real-world solutions for climate adaptation in the city space. We conducted a series of preliminary design actions, both theoretical and practical, to situate the conceptualization of such solutions within the context of the Basque Country, Spain, where our research is situated [

21]. In this article, we describe in detail the second phase of the research by documenting the conceptualization, design, and technical development of a novel urban furniture solution -

Urban Oasis, now registered as a patent - which is expected to be implemented and tested in a real environment in the city of Bilbao, now at the forefront of research and public policies on the adaptation of the urban space to climate change and its threats [

1]. We addressed the development of

Urban Oasis as a practice-based-research endeavour and specifically, as a Research-through- Design project. In the specific case of climate change adaptation in the city space, where general, long-term strategies have to go hand in hand with short and medium-term tactics, we believe that practice-led research, with its conjectural nature and iterative processes, can be highly effective.

In the following sections, we first briefly describe the conceptual framework against which the design process was conducted. Secondly, we describe in detail the adopted design method of the Double Diamond and its phases (Discover, Define, Develop, and Deliver) and how they were adopted in our project.

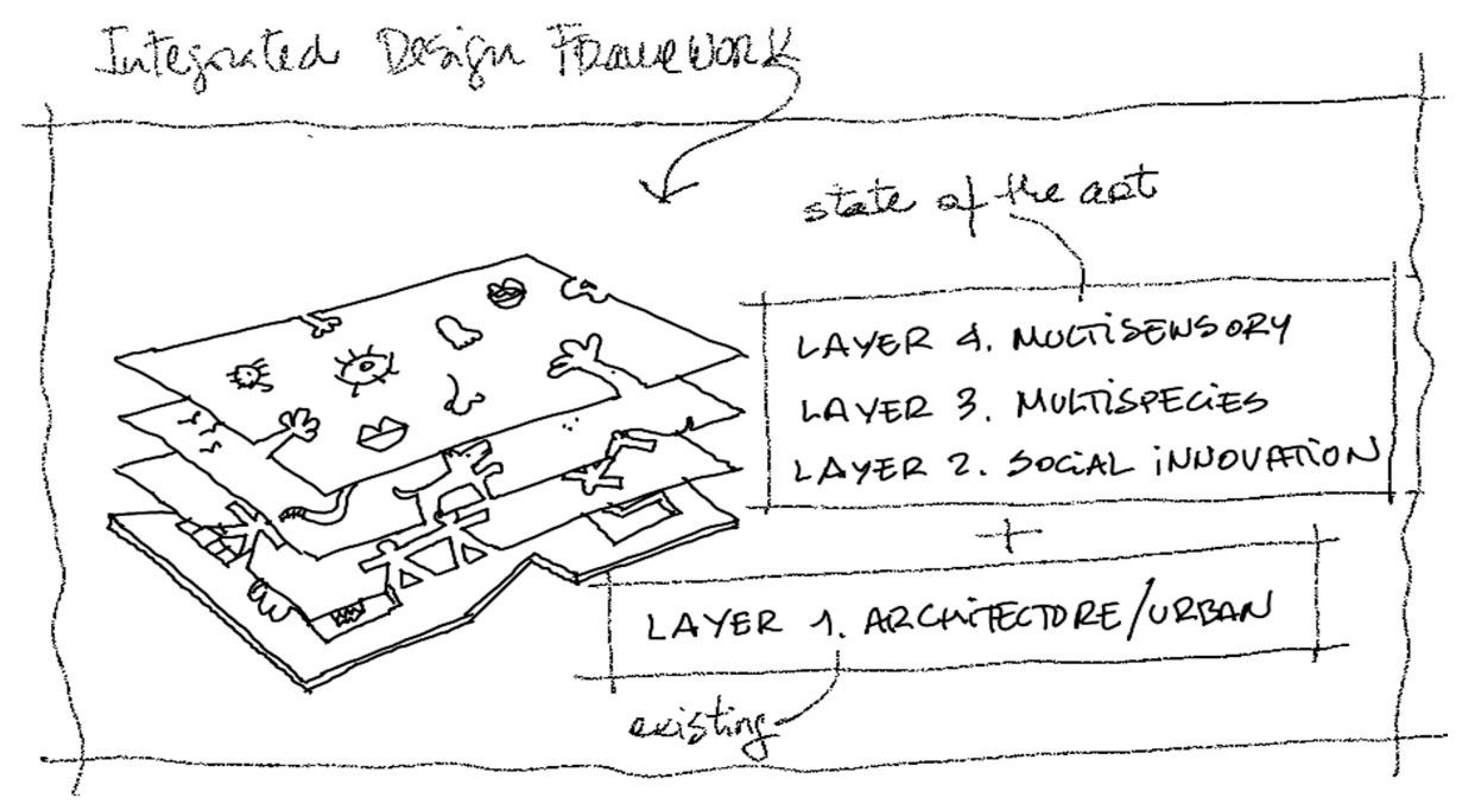

2.1. Overlapping Layers: The Integrated Design Framework

The practice-led research endeavour described in this paper has to be regarded as a first design action towards the definition of a broader framework for designing climate adaptation in the urban space which the co-authors of this paper are developing [

1]. The framework advocates for a transdisciplinary approach to urban space design in the light of the climate crisis and notably in the light of the scarce results, to date, of climate adaptation (if not maladaptation, see [

16]) designs and policies [

22]. The framework is based on four layers that address the city space on a continuum from tangible (i.e. architecture and urban design solutions) to intangible (social innovation, multi-species approach, multi-sensory perception). As shown in

Figure 1, while the layer of architecture and urban design is already well established as it provides existing solutions to climate adaptation, the remaining three layers are the expression of emerging research that sees the city as an organic (or post-organic) entity, fostering a holistic, transdisciplinary approach to design solutions.

By definition, layers work as parallel blankets of data: By overlapping them we can identify how these planar categories interact with each other to deliver new patterns of information and structure of events [

23]. As we will describe in

Section 3,

Urban Oasis stems from the interconnection of all the layers to create a conceptual and physical suture between the more tangible and less tangible layers, thus providing a solution that is not only transdisciplinary but also transversal across the layers.

Urban Oasis incorporates urban furniture design into water gardens, an element already being implemented as a NbS for creating climate shelters in cities. The combination of design and ecology makes it essential to approach the project in a transdisciplinary manner. Although their benefits and efficiency are still unclear (see [

24]) we believe that the use of NbS provides an innovative foundation on which to build the integration of the intangible layers of social innovation, multi-species, and multi-sensory approach to the design of successful urban adaptation.

2.2. The Double Diamond Method and the Design Checklist

In this project, the design development followed the classical steps of the Design Thinking “Double Diamond” methodology

(Figure 2). The Double Diamond was introduced by the Design Council [

25] and it is widely used as a reference design method in a variety of contexts (e.g. design of services, analogue or digital products, public policies). The first phases, traditionally called Discover and Define, involve the integration of a state-of-the-art assessment (e.g. analyses of keywords from scientific literature, interviews with professionals with expertise in the field) with the accumulated knowledge and experience of the research team [

26].Typically, the material collected during the Discover phase will inform the definition of a descriptive brief of the project (the Define phase), which may include external clients’ or stakeholders’ requirements alongside external constraints or self-imposed limitations that the design team identifies as fundamental for development [

27]. In this design-driven approach, the conjectural nature of design as a discipline is a key premise, and the designers’ own accumulated experience [

26] and initial idea generators (the

primary generators, see [

28]) become integral to the workflow.

In the Double Diamond the Discover phase is expansive and opens up a number of design possibilities and establishes the research questions and goals of a design process, while the subsequent Define phase narrows them down to ensure the design is sufficiently valid [

29]. In this project, the Discover and Define phases led to the definition of a Design Checklist (see [

17] for further details) that identifies 12 key parameters that successful solutions for the design of the urban space should include:

Pedestrianization: Prioritize pedestrians by reducing car traffic and introducing lighter mobility options, enhancing urban liveability.

Applied Technology: Use smart systems (e.g., sensing, 3D printing) for efficient space, traffic, and waste management while fostering interaction between people and cities.

Universal Accessibility: Design inclusively by considering all abilities (including temporary disabilities and non-human entities) for equitable urban spaces.

Multifunctionality: Create adaptable spaces for recreation, culture, and commerce. Incorporate modular designs to ensure resilience during emergencies and efficient space use.

Durability: Use weather-resistant, vandal-proof materials for urban furniture to withstand climate uncertainties and ensure longevity.

Green Spaces: Integrate green areas to improve air quality, climate adaptation, and water cycle management, promoting ecological sustainability.

Liveability/Social Sustainability: Prioritize liveable urban spaces that enhance quality of life, addressing post-pandemic social and environmental challenges.

Sustainable Logistics: Plan efficient logistics with loading zones, decentralized hubs, and sustainable vehicles to support rising e-commerce and emergencies.

Modularity: Design flexible urban furniture for diverse uses, maximizing inclusivity, sustainability, and adaptability.

Urban Safety: Ensure perceived safety through lighting, open spaces, visibility, and secure mobility networks (e.g., bike lanes).

Cultural Identity: Preserve history and include local art to strengthen identity, promote belonging, and integrate diverse cultures.

Multimodality/Commerce: Balance pedestrian, cyclist, and PMV mobility with commercial needs through thoughtful design and conflict management.

During the project, the Design Checklist has been adopted as the guiding tool to validate the compliance of the different phases - from conceptualisation to development - with our primary goal: to provide novel solutions for the climate adaptability of the sustainable and egalitarian city of the future.

2.3. Research Team

In the Develop and Deliver phases (the second half of the Double Diamond method), we relied on a multidisciplinary team to define initial work principles following the design framework and tools established in the Discover and Define phases. The team is composed of researchers in engineering with expertise in biomaterials and circular economy with an industrial focus; researchers in architecture with expertise in landscape, public space, and city studies, architects with expertise in urban furniture design, 3D modelling, and 3D design, an artist with expertise in fast prototyping and video production, and a modelling expert from the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU). To complement the development of the intangible layers of our approach to design (see

Section 2.2), experts in soundscape studies, interaction design, and social innovation from the Design Research Group at the University of Deusto were also engaged. The team also counted on an industrial partner, the company Transformados Metálicos SL, specialised in high-quality steel construction with a strong emphasis on sustainability. Additionally, to complement the development of social and perceptual aspects of the intangible layers, we engaged experts in sound, interaction, and social innovation from the Design Research Group at the University of Deusto. The project posed a significant challenge for the design team as it involved creating a novel solution in a field where formal innovation (i.e. related to the formal appearance of a product, vs radical innovation of a product’s substantial characteristics and usages) is the common approach. With this project, our aim was to go beyond mere formality to pave the way for a potential paradigm shift in how public space and its components are designed to adapt to climate change.

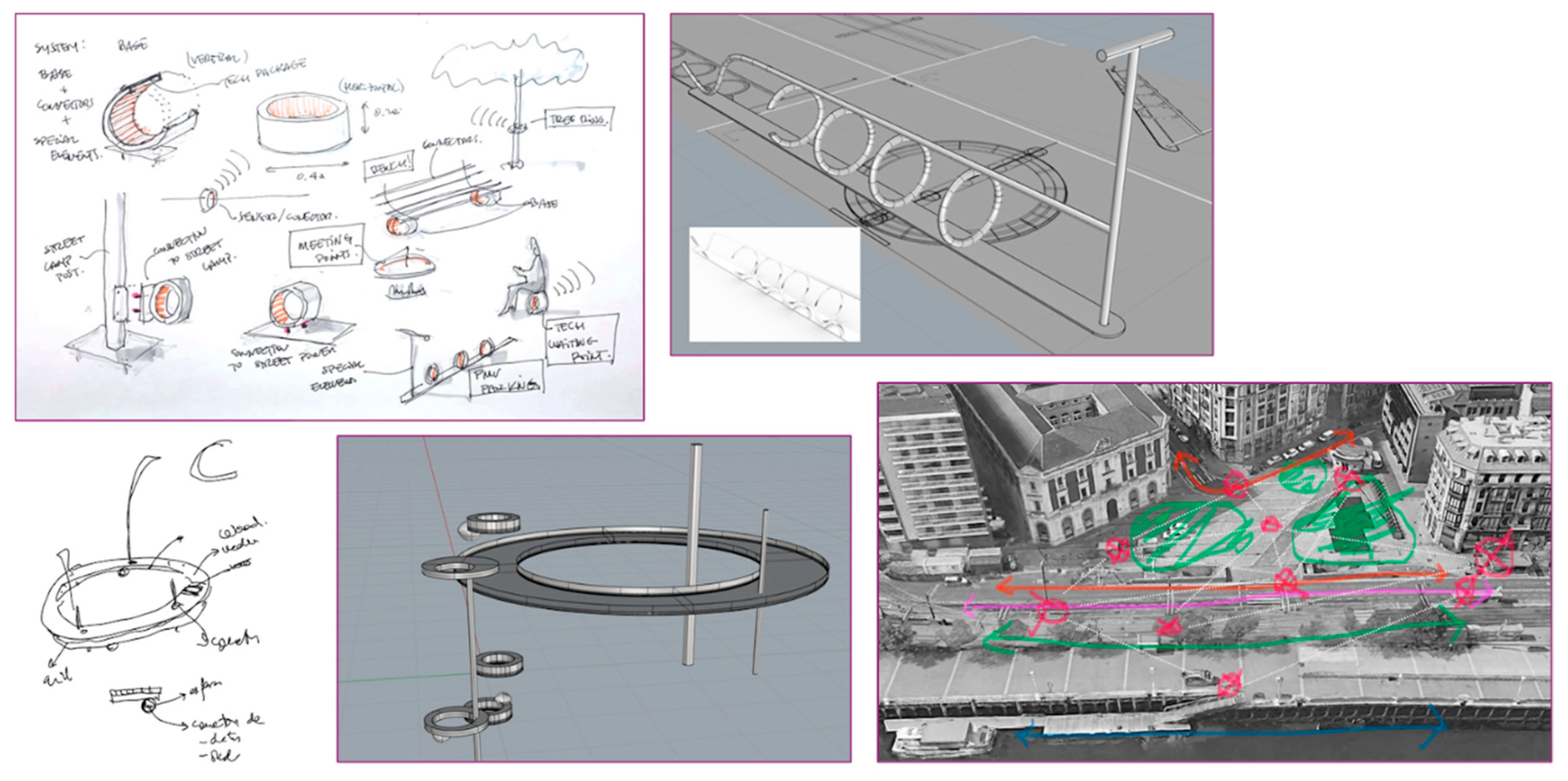

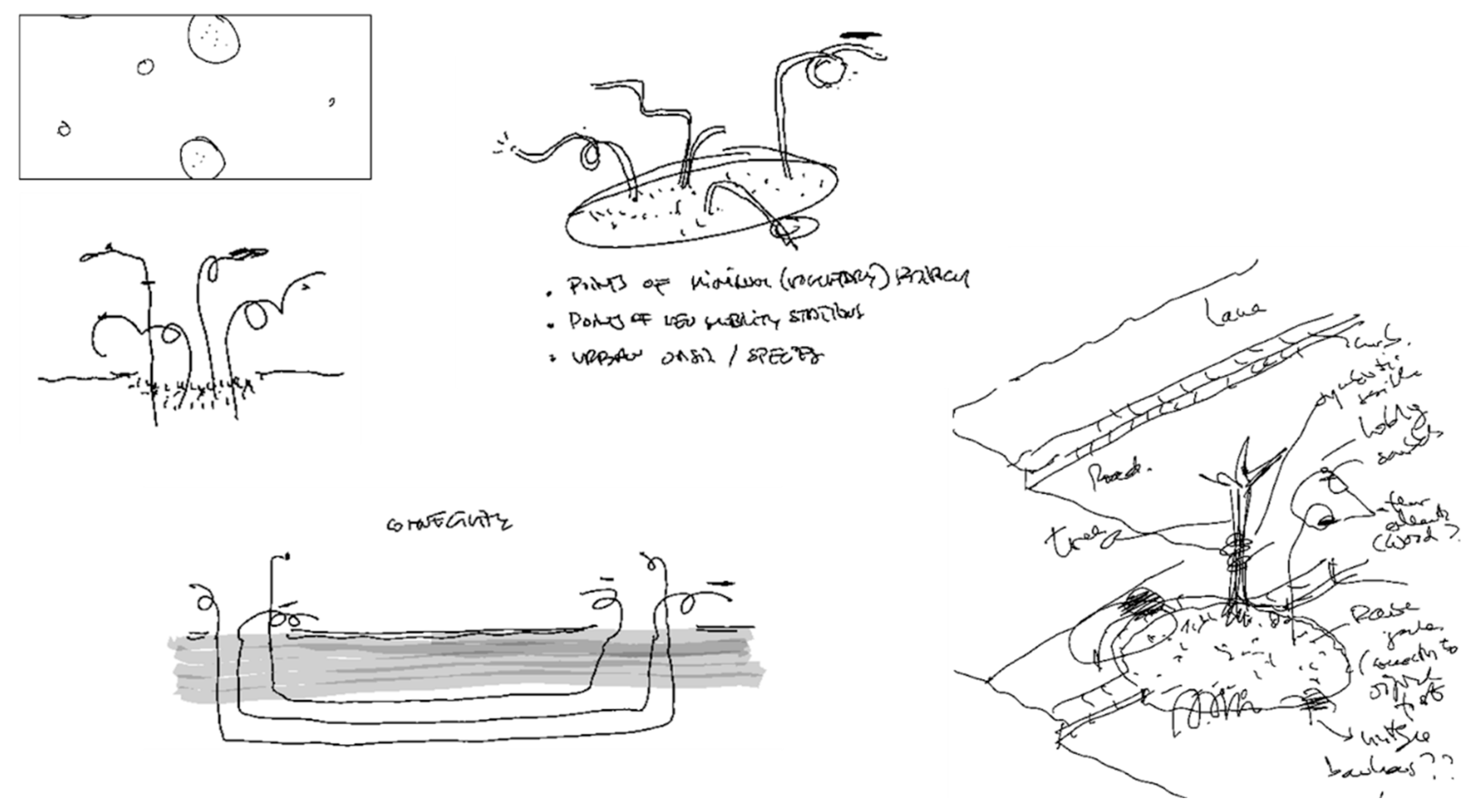

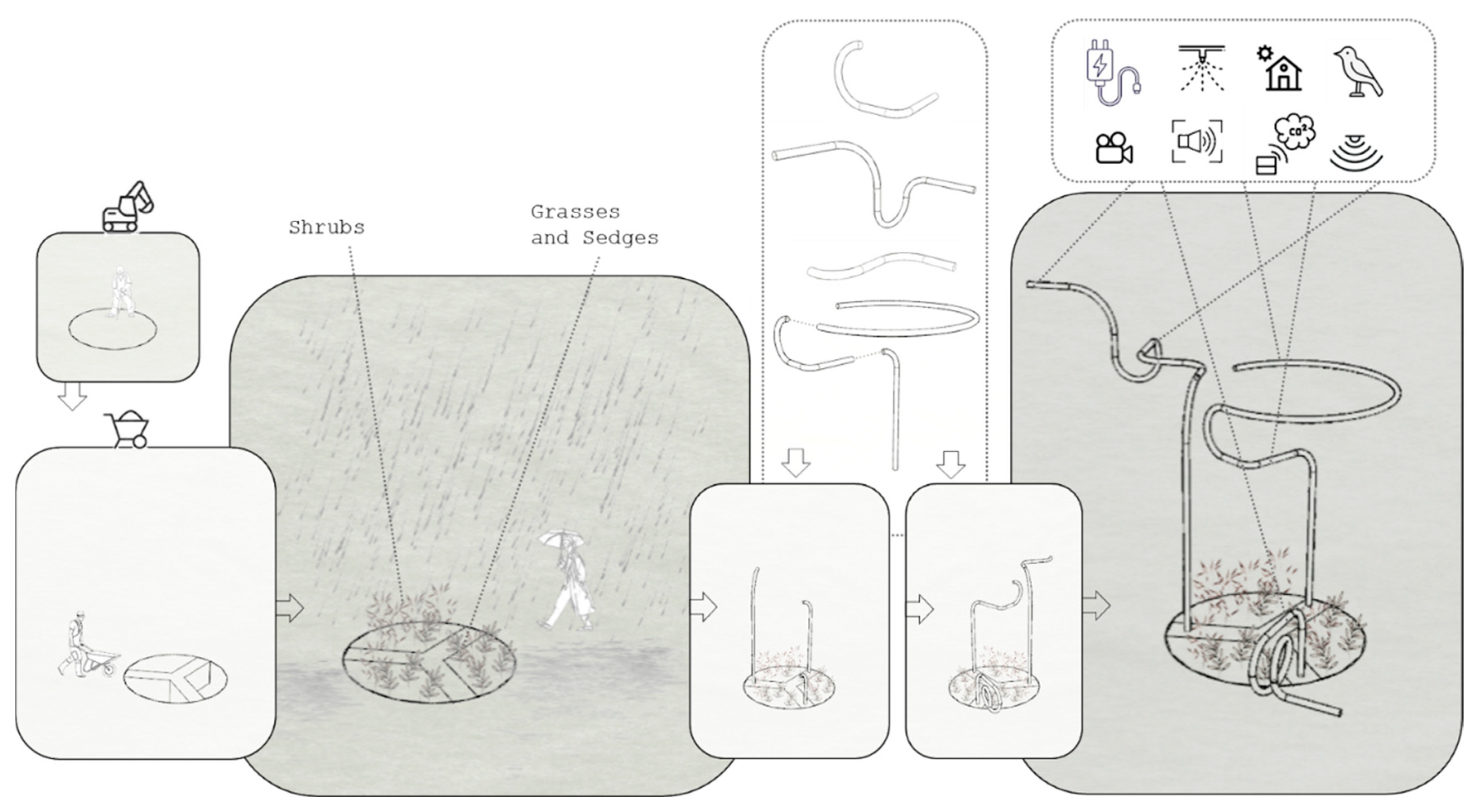

2.4. Evolution and Development of the Idea

Once defined the design framework of reference (see

Section 2.1) and the appropriate design tools (the Design Checklist, see

Section 2.2) the team began to sketch and evaluate ideas and concepts. The third phase (Develop) is expansive and, as such, allows for the free contribution of ideas and generative drawing. The initial concepts that emerged aimed for a simple, understated formal unit i.e. the minimum formal element that would later be replicated as a system or network, and installed at various points in the city, offering multiple solutions. We first explored simple components (such as ring-shaped elements, see

Figure 3) that could cooperatively or parasitically anchor to existing city elements such as lampposts or trees. The goal was to leverage existing elements for greater sustainability, add minimal visual noise to the existing cityscape, and blur the boundary between natural and artificial by using elements from both realms in similar ways. This initial phase of the Develop stage along with the mapping of potential locations where such embryonic elements could be used in the Basque Country is detailed in [

21].

This initial approach helped us identify key design decisions such as working with metallic elements and sustainable materials and utilizing a production approach aligned with the manufacturing methods of the project’s industrial partner. This ensured process economy and better-controlled LCA (Life Cycle Assessment). However, the placement and integration of the components into the city’s pavements, streets, or squares were still unclear. In the following iteration of the Develop phase, the team deepened the study of the manufacturing process to explore the usage of steel tubes to create tree-like structures (see

Figure 4).

The original ring-shape evolved into a trunk-like shape that could support the solution’s functional components by, similarly to a lamppost, grounding on the city’s pavement. These modular trunks and shapes, designed with adjustable and combinable forms, were open-ended and, after consulting diameters and turning radii, deemed feasible for production by the company. The structure could include solar panels and/or shading elements to create adaptable climate shelters. Additionally, these tubular components could house sensors, water sprinklers, colour, lighting, electric chargers, cameras, acoustic sensors and audio speakers, and other functional pieces along their length and at their ends, thus maximising the potential for the solution to integrate all the four layers of our design framework i.e. to consider multi-sensory elements both for data collection (e.g. acoustic sensors to measure the sound level or even identify sound sources, see [

1]) and for multi-sensory design actions toward improved wellbeing of residents [

30].

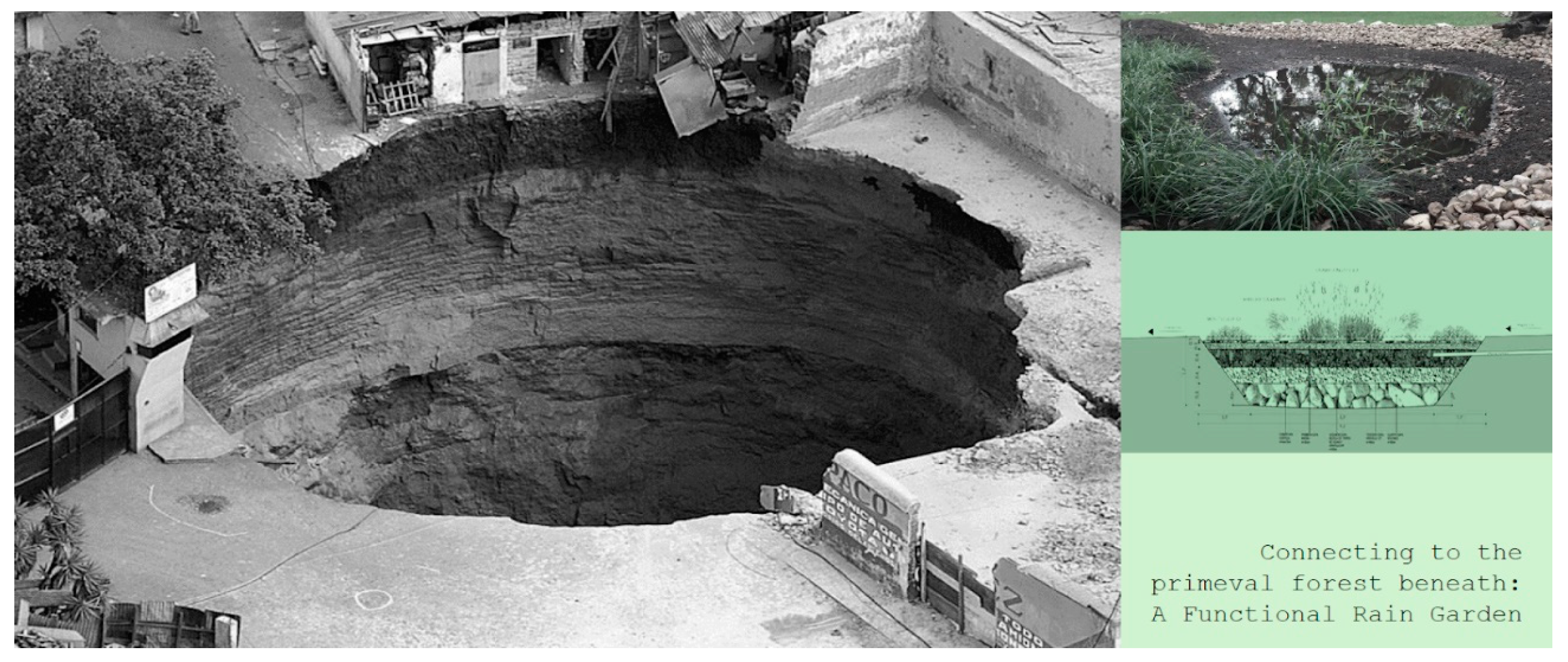

Still, the solution required a fundamental layer (see

Figure 1) to bridge the gap between the city as a traditional human-centred design and a vision where other species could find refuge, fostering a gentle transition between the harshness of the urban environment and the natural world. As a concept design, the team speculated about removing the city pavement to reveal the primal forest beneath as a regenerative oasis, a hybrid and refreshing space in the city (

Figure 5). This hole, this void, this indiscriminate cut—this

urban oasis—would serve as the habitat where our modular elements can grow. Like a ubiquitous invasive rhizome, we envisioned perforations that, disregarding the boundaries between sidewalks and roads, can be shaped according to the needs of mobility, shelters, or other social, perceptual, and interspecies layers within the public realm.

Like a network of plants and roots these perforations could conceptually - and perhaps physically - connect through a systemic rhizome, transforming our solution into a natural interconnected organism (

Figure 6). This rhizome would establish symbiotic relationships with the roots of existing trees and the city's underground infrastructure.

Each circular void perforated into the city's surface houses a rain garden on which the modular steel elements are installed. The perforation system with rain gardens enhances the permeability of urban floorings. In addition to hosting potential uses, functions, and shelters on its upper part, it optimizes flood risks and improves the water cycle by increasing the porosity of an ecosystem that lacks permeability, such as urban ground.

This solution presents an innovative approach if compared to the state-of-the-art climate change adaptation solutions (see [

17] for a recent review). The design is conceived as a modular, living system that evolves and adapts - a model of resilience and adaptability. The final design of

Urban Oasis is conceived as a network of points where each unit consists of a circular opening in the urban pavement with a rain garden, a concealed foundation footing, and functional aerial elements (

Figure 7). The overall system of units creates a network of green points that function as urban refuges, where the green infrastructure of the rain garden provides interconnected urban and social functions and potential climate sheltering

The solution offers a sustainable urban furniture system distinguished by its modular design versatility and integration into city pavements through an opening where the concrete foundation that supports the aerial elements of the furniture is housed and connects to urban infrastructures (

Figure 8).

The opening where the foundation is located has an approximate diameter of two metres and can be adjusted according to specific needs. The circular opening is cut into the pavement, finished around its perimeter, and accommodates a rain garden, which is a typified NbS. This rain garden shares with the foundations the space within the circle and contributes to improving drainage and permeability of the city's surface [

31], thereby facilitating the natural water cycle and reducing flood risk. The aerial elements of the furniture design which emerge from the foundation, are made of hollow stainless-steel tubes with a diameter of 50 mm and a thickness of 2 mm (also adjustable as needed). The pieces are predominantly curved and modular, allowing multiple configurations, using standard compound units. The joints are made using a stainless-steel connector piece. Power and data run through the interior of the tubes, and at the top and along selected points of the tube shaft functional elements such as sensors (e.g. temperature, light, sound, presence), cameras, lights, speakers, supports for covering elements, electric vehicle chargers, and other functional components can be housed. The reader can refer to

Figure 7 to see how each of the elements is integrated into

Urban Oasis. The system's fundamental components (elements 1, 2, and 3 in

Figure 7) are:

Rain Garden: A circular opening in the city's surface that houses the various elements required for a rain garden. It is designed with filtering components suited to the climatic conditions and features native plants. It includes a foundation for the aerial components of urban furniture design and connections to the city’s underground installations.

Aerial Modular Elements: Stainless steel tubes anchored to the foundation within the rain garden (1). These tubes are designed with specific curves, diameters, and materials defined by the industrial partner of the project and combinable through custom-designed joints. They are manufactured to accommodate functional components (3).

Functional Components: These are installed along the tubes (2) or at their tip. They may include sensors, lights, cameras, chargers, sprinklers, and other elements. Additional features, such as canopies, shading covers, solar panels, or speakers, can also be integrated into these tubes.

3. Results: Urban Oasis—A Patented Solution

The result of the research presented in this article is formalized as an industrial solution in the form of a Utility Model, whose registration application has been submitted to the Spanish Patent and Trademark Office (number U202432323).

3.1. Justification of Innovation

The project’s innovation and patentability are justified as a contribution to the advancement of knowledge and the industrial application of innovative solutions for public spaces, directly linked to urban adaptability to climate change. While patents related to rain garden systems and urban drainage solutions already exist, Urban Oasis introduces significant novelty through its unique combination of functionalities. The differentiating aspect lies in the integration of functional aerial elements within the hollow stainless-steel tubes, which not only serve as the furniture's structure but also house sensors, cameras, lights, electric chargers, speakers, and other technological components that provide multiple urban services. These elements are not described in current patents, granting the solution a clear competitive edge and patentability. Although rain gardens and modularity concepts are well known, the integration of smart urban technology and the system's ability to function both as urban landscaping and as part of the technological infrastructure of cities represent clear innovation. This approach combines sustainability elements with current demands for connectivity and urban services, reinforcing its feasibility as a patentable invention.

Urban Oasis can have significant applications across various industries due to its combination of NbS and smart urban technology. The main applications include:

Urban infrastructure and public furniture: The system can be adopted by cities to enhance public spaces, integrating NbS that improve stormwater management and reduce flooding risks. Its ability to house elements such as lights, cameras, speakers, and sensors enables the creation of smart urban infrastructure, facilitating environmental monitoring, safety, and efficient resource use in urban areas.

Real estate development and sustainable urbanization: In real estate development, this system can be integrated into urbanization projects aimed at meeting environmental regulations and sustainability goals. By providing both green infrastructure and functional furniture, it is ideal for residential and commercial complexes requiring sustainable drainage solutions and carbon footprint reduction through renewable energy use and smart technologies.

Transportation and electric mobility: The integrated electric chargers within the furniture elements offer an innovative solution for cities aiming to promote the use of electric vehicles. This system can be installed in strategic locations such as parking lots, bus stops, or waiting points for scooters and electric bikes, supporting sustainable mobility infrastructure.

Smart and connected cities: Smart furniture equipped with sensors and data connectivity facilitates the collection of valuable information for connected cities [

32], such as weather monitoring, noise levels, temperature, or air quality. This real-time monitoring capability allows cities to improve operational efficiency and enhance citizen experiences.

Urban regeneration and green infrastructures: This system can also play a key role in urban renewal projects, transforming degraded industrial or commercial areas into multifunctional green spaces. By improving soil permeability and reducing urban heat impacts, the system contributes to the environmental regeneration of cities.

Urban Oasis offers a multifunctional approach that not only addresses the environmental challenges of modern cities but also enhances technological connectivity and the efficiency of urban services. This makes it an integral solution for designing and developing sustainable cities, aligning with SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities.

3.2. Technical Description

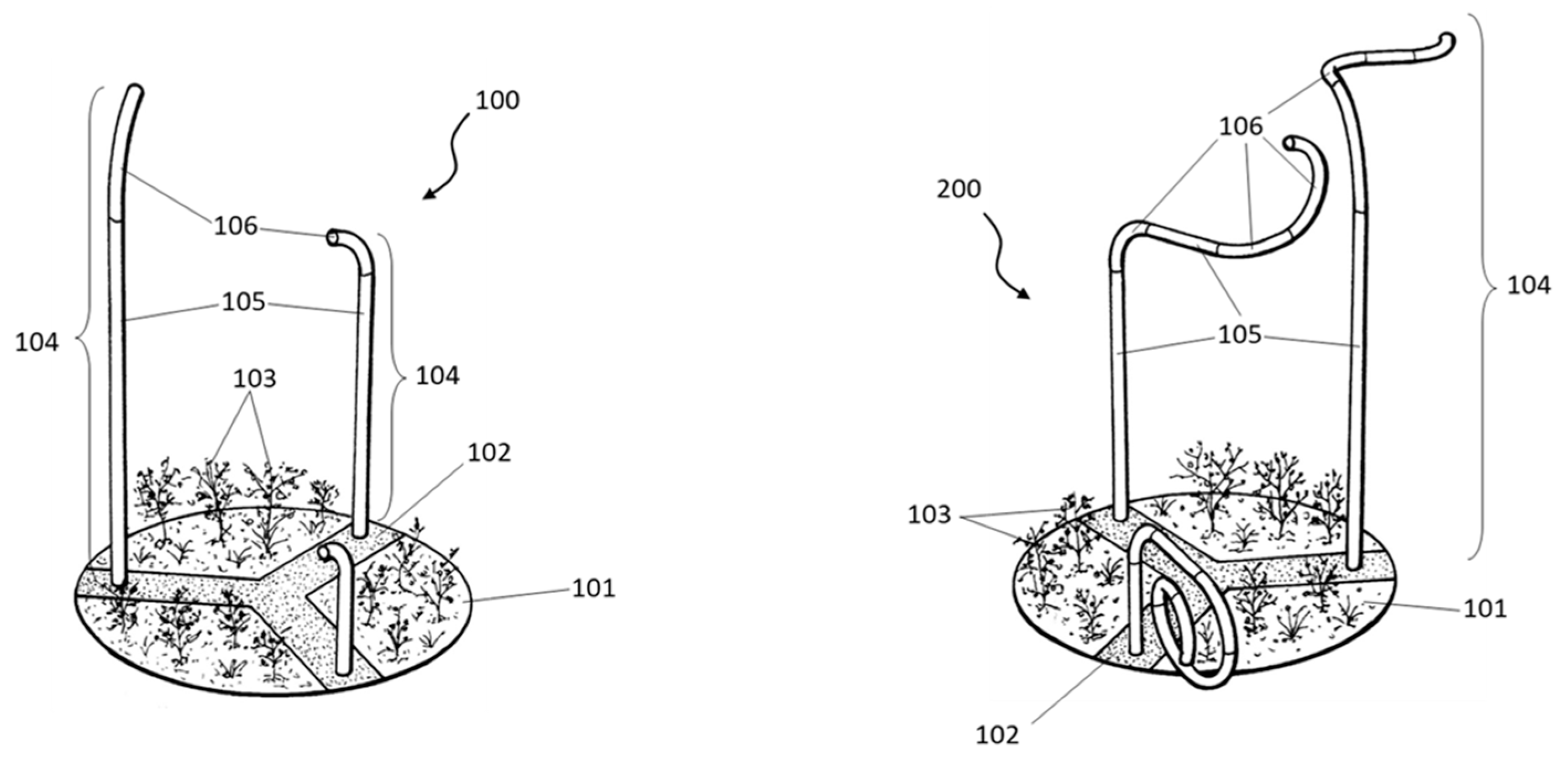

Figure 9 shows urban infrastructure (100) comprising three hollow tubular supports (104). Each hollow tubular support (104) includes at least one straight tubular section (105) and at least one curved tubular section (106). The length of each tubular section (105, 106) may vary, thereby creating hollow tubular supports (104) of arbitrary shapes. The opening on the urban pavement that accommodates the rain garden is circular. However, other geometric shapes can be implemented in the design of the urban rain garden. The hollow tubular supports (104) are anchored at one of their ends to a foundation (102). This foundation (102) extends from one edge of the circle defining the opening in the urban pavement where the urban rain garden (100) is located to the opposite edge. In the arrangement shown in

Figure 9, the foundation (102) is Y-shaped, connecting points on the perimeter of the opening to a central area within it.

The part of the urban infrastructure (100, left side of

Figure 9) not occupied by the foundation (102) comprises an urban garden (101). The urban rain garden (101) includes an outer layer with vegetation (103) and underlying layers of filtering material (not shown) configured to filter water entering the urban rain garden (101). Naturally, the rain garden (101), particularly its filtering layers, can extend beneath the foundation (102). The right side of

Figure 9 shows urban infrastructure (200) where the tubular supports (104) feature straight sections (105) and curved sections (106) of varying lengths, assembled in a sequence different from those of the tubular supports (104) in the left side of

Figure 9. This variation produces tubular supports (104) of different shapes, optimizing the design for its intended urban functionality.

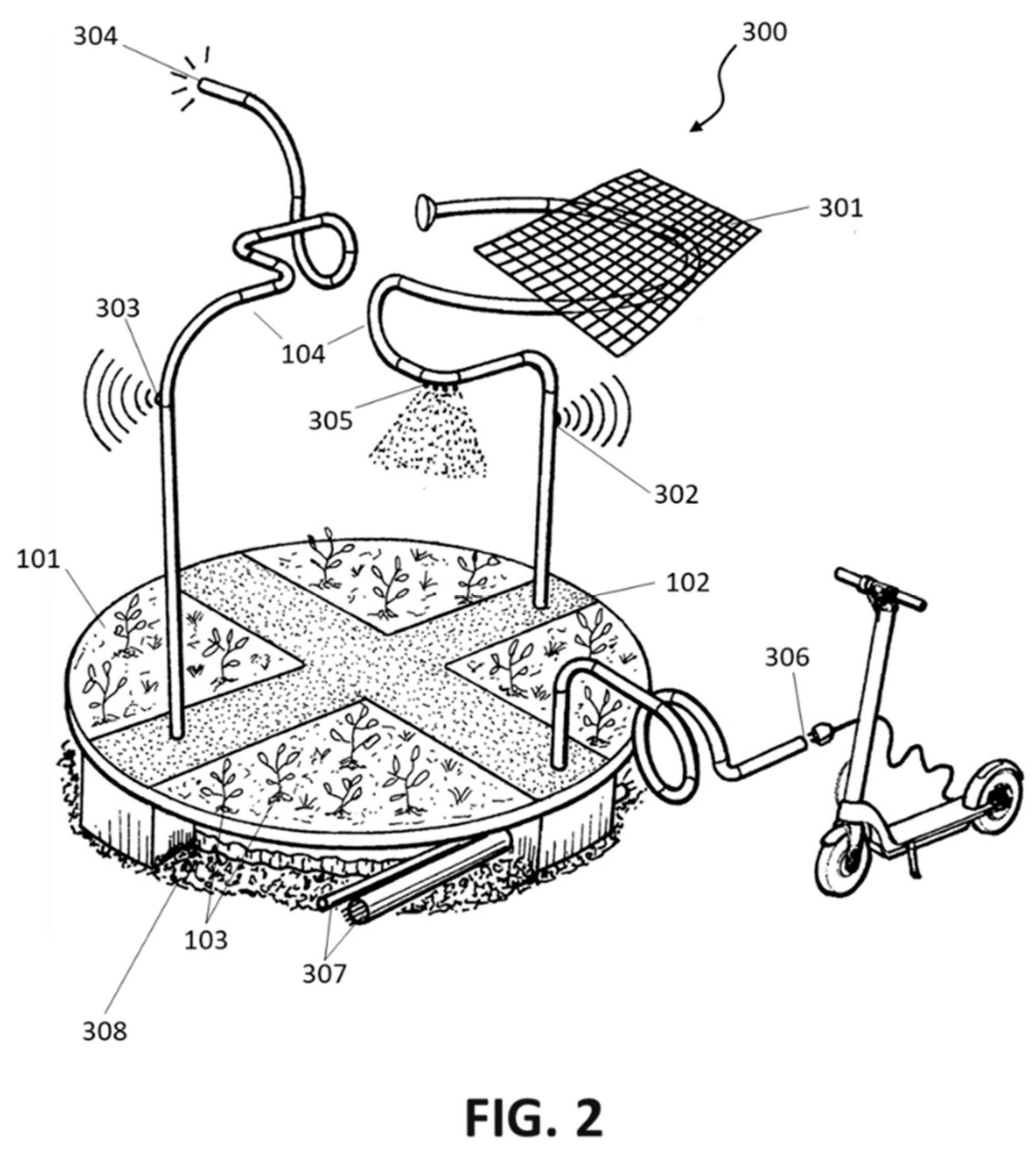

Figure 10 depicts urban infrastructure (300) with multiple hollow tubulars supports. In this arrangement, the opening in the urban pavement defining the urban rain garden (300) is circular. The foundation (102) anchoring the hollow tubular supports (104) has a cross shape, with arms arranged transversely and a central connection point within the opening. The area of the urban rain garden (300) not occupied by the foundation (102) comprises an urban garden (101). The urban rain garden (101) includes an outer layer of vegetation (103) and underlying layers of filtering material (not shown) configured to filter water entering the rain garden (101). Naturally, the rain garden (101), particularly its filtering layers, can extend beneath the foundation (102).

In this case, the foundation (102) extends to the outer surface of the urban infrastructure, meaning no vegetation (103) grows on it. In alternative embodiments, the foundation (102) is buried, allowing vegetation (101) to grow over the entire area of the opening. Beneath the foundation (102), the rain garden (300) may also include layers of filtering material (308) configured to filter water entering the urban rain garden (300). Below the filtering layer (308), there may be connections (307) to the urban sewage system, configured to evacuate excess water received by the urban rain garden (300).

A plurality of hollow tubular supports (104) are anchored to the foundation (102). Each hollow tubular support (104) comprises multiple straight and curved sections of varying lengths, optimizing the resulting shape of the hollow tubular support (104) for its intended function.

The hollow tubular supports (104) can incorporate various devices that provide service and functionality to the urban rain garden (300). Devices such as speakers (302), telecommunications antennas (303), lamps (304), or electric charger connectors (306) can be integrated into the hollow tubular supports (104). These supports (104) with integrated devices (302, 303, 304, 306) are connected to the electrical power supply through their anchor point on the foundation (102). The hollow tubular supports (104) may also include liquid sprinklers (305) or parasol surfaces (301). Supports (104) with liquid sprinklers (305) are connected to liquid conduits through their anchor point on the foundation (102).

In this text, the word "comprises" and its variants (such as "comprising," etc.) should not be interpreted exclusively; that is, they do not exclude the possibility of the described elements including other components, steps, etc. Additionally, the invention is not limited to the specific arrangements described but also encompasses variations that could be implemented.

4. Discussion

This article addresses key aspects of urban sustainability, adaptability, and multifunctionality through the innovative design of both rain gardens and urban furniture. Starting from an investigation that aimed to answer the need for a paradigm shift in the design and implementation of urban furniture and public space elements for a more sustainable and egalitarian city, the research defined an actual implementable solution for the adaptation of cities to climate change. While theoretical and practical research in this field is advancing, the definition of specific usable and adaptive solutions validated in a real environment is still an unfulfilled need. We propose the use of modular and interactive Nature-based Solutions that aim to blend the artificial and human-centred with the natural and more-than-human to provide a holistic approach to the challenges posed by climate adaptation.

With this research, we also want to vindicate design as a valid form of research. The research hereby presented was conducted following an iterative design-driven process validated through the lenses of a previously defined Design Checklist and against a design framework, currently in progress, that incorporates the overlapping tangible and intangible layers of the urban realm into the design of real-world solutions. The first outcome of our approach is a registered industrial patent for the novel solution Urban Oasis.

Below, we summarise how the proposed design fulfils the Design Checklist criteria and interconnections the layers of our Integrated Design Framework.

4.1. Alignment with the Design Checklist

Urban Oasis adheres to the key principles outlined in the Design Checklist, specifically:

Pedestrianisation: The design prioritises pedestrian use by replacing conventional paved surfaces with permeable gardens, promoting walkable and green public spaces.

Applied Technology: Environmental sensors, motion detectors, and other embedded technologies enable smart management of urban spaces, providing real-time data on environmental and social conditions.

Universal Accessibility: Modular designs allow inclusivity for users of all abilities, ensuring equal access and use.

Multifunctionality: The rain garden incorporates features for environmental monitoring, public utility (charging stations), and ecological integration, showcasing its adaptability for diverse urban contexts.

Durability: The use of stainless steel and other robust materials ensures longevity and resistance to climate-related challenges.

Green Spaces: By integrating rain gardens, the design contributes to ecological sustainability, improving air quality, managing water cycles, and enhancing urban biodiversity.

Liveability/Social Sustainability: The inclusion of seating areas and water points within a rain garden design encourages the use of these spaces for social interaction and leisure, enhancing community engagement (Wang et al., 2024).

Sustainable Logistics: The design integrates with urban infrastructure to ensure efficiency in water and energy usage, supporting broader sustainability goals.

Modularity: Its scalable and reversible components allow adaptation to various urban environments, creating a flexible system suitable for long-term use.

Urban Safety: Enhanced lighting and open design improve visibility and perceived safety for urban users.

Cultural Identity: The customizable design respects local aesthetics and integrates with community-specific cultural elements.

Multimodality/Commerce: The modular system balances pedestrian, cyclist, and commercial needs, enhancing the overall functionality of public spaces.

4.2. Interconnection of Layers

The proposed design integrates and connects the tangible and intangible layers of the Integrated Design Framework. Tangible layers, such as architecture and urban furniture, serve as the foundation, while intangible layers (social innovation, more-than-human components, and multisensory design) enhance the system’s inclusivity, functionality, and ecological integration. The design’s transversality is achieved by stitching together the layers conceptually and physically. For example:

Social innovation is incorporated by creating an inclusive, adaptable space for diverse users based on the principle that healthy shared environments “

protects communities from exposure to environmental harms and is conducive to the physical, mental and social well-being of its inhabitants” [

30].

More-than-human components [

33] are addressed via green infrastructure that supports urban biodiversity and ecological health. Rain gardens attract various species such as bugs, butterflies, birds and bees, creating an urban solution to the declining population of beneficial species in human environments due to habitat loss.

Functional elements that support multisensory design (e.g. speakers, lights) can be used to enhance human and non-human resident populations’ connection to the urban environment, improving quality of life. For instance, soundscape design can be integrated to leverage the restorative power of sound and create a healthier environment for individuals and society. Additionally, ongoing research shows that natural soundscapes can improve perceived comfort in urban space [

34].

Phyto-purification system becomes an element of interest at both perceptive and didactive levels [

35]. The rain garden is a miniature ecosystem that reproduces the natural water cycle, becoming an educational tool to raise awareness among younger generations of its importance in climate adaptation.

The system leverages Nature-based Solutions (NbS) as a core strategy to address climate adaptation challenges in urban environments. Rain gardens serve as ecological hubs that improve water management, reduce heat island effects, and enhance urban biodiversity [

36]. This approach offers an alternative to traditional hard infrastructure, promoting sustainability and resilience while integrating seamlessly with existing urban networks.

5. Conclusions

This research underscores the importance of a transdisciplinary approach to urban design, combining architecture, engineering, ecology, and social sciences to develop innovative solutions for climate change adaptation. The Urban Oasis rain garden exemplifies how multifunctional and modular urban infrastructure can address the complexities of urban environments while adhering to sustainability principles.

By integrating tangible and intangible layers within the urban fabric, the proposed rain garden design goes beyond conventional solutions, handling not only environmental challenges but also social and technological needs. Its modular and scalable nature enhances widespread application across various urban contexts, making it a versatile tool for cities aiming to achieve SDG11: "Sustainable Cities and Communities."

The next steps in the development of Urban Oasis include:

Full-scale prototyping and implementation of the design at a pilot location.

Testing and validation of its functionality, durability, and user interaction.

Refinement of the design based on empirical findings to ensure long-term feasibility and impact.

This research highlights the critical role of integrated design frameworks and practice-based research in creating more liveable, equitable, and climate-resilient cities.

6. Patents

The result of the research presented in this article is formalized as an industrial solution in the form of a Utility Model, whose registration application has been submitted to the Spanish Patent and Trademark Office (number U202432323).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S., S.L., A.L; methodology, J.S. and A.L; writing—original draft preparation, J.S., S.L., A.L.; writing—review and editing, J.S., S.L., A.L.; visualization, J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded under the 2022 University-Business-Society call from the University of the Basque Country with identification code number US22/21. SL work is partially funded by the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Cofund Programme of the European Commission (H2020-MSCA-COFUND-2020-101034228-WOLFRAM2). The funders had no involvement in the study design, data analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the company Transformados Metáliscos S.L. for their support and advice throughout the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| |

|

| LCA |

Life Cycle Assessment |

| NbS |

Nature-based Solutions |

| RtD |

Research through Design |

References

- Lenzi, S., Sádaba, J. and Retegi, A. (2025). Designing Climate Adaptation in the Urban Space: The Need for a Transdisciplinary Approach. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities. In review.

- Rius-Ulldemolins, J., & Klein, R. (2020). From top-down urban planning to culturally sensitive planning? Urban renewal and artistic activism in a neo-bohemian district in Barcelona. Journal of Urban Affairs, 44(4–5), 524–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2020.1811114. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Qing; Song, Yan; Cai, Yinying. Blending Bottom-Up and Top-Down Urban Village Redevelopment Modes: Comparing Multidimensional Welfare Changes of Resettled Households in Wuhan, China. Sustainability; Basel Tomo 12, N.º 18, (2020): 7447. DOI:10.3390/su12187447. [CrossRef]

- Semeraro, T., Nicola, Z., Lara, A., Sergi Cucinelli, F., & Aretano, R. (2020). A Bottom-Up and Top-Down Participatory Approach to Planning and Designing Local Urban Development: Evidence from an Urban University Center. Land, 9(4), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9040098. [CrossRef]

- Atanacković Jeličić, J., Rapaić, M., Kapetina, M., Medić, S., Ecet, D.. (2021). Urban planning method for fostering social sustainability: Can bottom-up and top-down meet?. Results in Engineering, Volume 12,2021. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2021.100284. [CrossRef]

- Lang, D. J., Wiek, A., Bergmann, M., Stauffacher, M., Martens, P., Moll, P., Swilling, M., & Thomas, C. J. (2012). Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: Practice, principles, and challenges. Sustainability Science, 7(SUPPL. 1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11625-011-0149-X. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, R. J. (2022). Co-Benefits of Transdisciplinary Planning for Healthy Cities. Urban Planning, 7(4), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v7i4.5674. [CrossRef]

- Amorim-Maia, A. T. (2023). Creating inclusive and effective climate shelters. Policy Brief. BCNUEJ. Available online at: https://tinyurl.com/3hzevenh. Last accessed: 16 Jan 2025.

- Lwasa, S., K.C. Seto, X. Bai, H. Blanco, K.R. Gurney, Ş. Kılkış, O. Lucon, J. Murakami, J. Pan, A. Sharifi, Y. Yamagata (2022). Urban systems and other settlements. In IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Slade, A. Al Khourdajie, R. van Diemen, D. McCollum, M. Pathak, S. Some, P. Vyas, R. Fradera, M. Belkacemi, A. Hasija, G. Lisboa, S. Luz, J. Malley, (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA. doi: 10.1017/9781009157926.010. [CrossRef]

- López Plazas, F., Crespo Sánchez, E., Llorca Pérez, R., Santacana Albanilla, E. (2023). Schools as climate shelters: Design, implementation and monitoring methodology based on the Barcelona experience, Journal of Cleaner Production, Volume 432, 139588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.139588. [CrossRef]

- Amorim-Maia, A.T., Anguelovski, I., Connolly, J., Chu, E. (2023). Seeking refuge? The potential of urban climate shelters to address intersecting vulnerabilities. Landscape and Urban Planning. Volume 238, 104836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2023.104836. [CrossRef]

- Florido, F. What Are Climate Shelters? CREAF 2022. Available online: https://www.creaf.cat/en/articles/what-are-climate-shelters (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Walker, S.E., Smith, E.A., Bennett, N., Bannister, E., Narayana, A., Nuckols, T., Pineda Velez, K., Wrigley, J., Bailey, K.M. (2024). Defining and conceptualizing equity and justice in climate adaptation. Global Environmental Change, Volume 87, 102885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2024.102885. [CrossRef]

- Brousseau, J. J., Stern, M. J., Pownall, M., & Hansen, L. J. (2024). Understanding how justice is considered in climate adaptation approaches: a qualitative review of climate adaptation plans. Local Environment, 29(12), 1644–1663. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2024.2386964. [CrossRef]

- Olazabal, M., Loroño-Leturiondo, M., Amorín-Maia, A.T. et al. Integrating science and the arts to deglobalize climate change adaptation. Nat Commun 15, 2971 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47400-7. [CrossRef]

- Schipper, E. Lisa F. (2020). Maladaptation: When Adaptation to Climate Change Goes Very Wrong. One Earth, Volume 3, Issue 4, 409 - 414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2020.09.014. [CrossRef]

- Sádaba, J., Alonso, Y., Latasa, I., & Luzarraga, A. (2024). Towards Resilient and Inclusive Cities: A Framework for Sustainable Street-Level Urban Design. Urban Science, 8(4), 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci8040264. [CrossRef]

- Cortesão, J.; Lenzholzer, S. Research Through Design in Urban and Landscape Design Practice. Journal of Urban Design 2022, 27, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2022.2062313. [CrossRef]

- Cross, N. (1982). Designerly ways of knowing. Design Studies. Volume 3:4. Pp. 221-227. https://doi.org/10.1016/0142-694X(82)90040-0. [CrossRef]

- Stappers, P. J., & Giaccardi, E. (2017). Research through Design. In M. Soegaard, & R. Friis-Dam (Eds.), The Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction (2nd ed., pp. 1-94). The Interaction Design Foundation.

- Sádaba, J.; Alonso, Y.; Latasa, I.; Collantes, E. Framing the Scope for Transdisciplinary Research in Architecture and Urban Design: A Work-in-Progress on the Future of Streets. Blucher Design Proceedings 2023, 1, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.5151/ead2023-1BIL-01Full-10Sadaba-et-al. [CrossRef]

- Dilling, L. et al. Is adaptation success a flawed concept? Nat. Clim. Change 9, 572–574 (2019).

- Maki, F. Investigations in Collective Form; Washington University School of Architecture: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1964.

- Goodwin, S.; Olazabal, M.; Castro, A.J.; Pascual, U. Measuring the contribution of nature-based solutions beyond climate adaptation in cities. Global Environmental Change 2024, 89, 102939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2024.102939. [CrossRef]

- Design Council (2005). The Double Diamond. URL: https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-resources/the-double-diamond/. Last accessed: 01/02/2025.

- Schön, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1983.

- Rowe, P. G. (1987). Design thinking. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Darke, J. The Primary Generator and the Design Process. Design Studies 1979, 1, 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/0142-694X(79)90027-9. [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. The Sciences of the Artificial; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1969.

- RUIZ ARANA, U. (2024). Multispecies soundscapes: a more-than-human approach. Proceedings of the InterNoise Conference 2024. Nantes, France. Pp. 2743-2749(7). Doi: https://doi.org/10.3397/IN_2024_3226. [CrossRef]

- Monachese, A.P.; Gómez-Villarino, M.T.; López-Santiago, J.; Sanz, E.; Almeida-Ñauñay, A.F.; Zubelzu, S. Challenges and Innovations in Urban Drainage Systems: Sustainable Drainage Systems Focus. Water 2025, 17, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17010076. [CrossRef]

- Ministerio del Medioambiente. Libro Verde de Sostenibilidad Urbana Y Local En La Era de La Información; Ministerio de Medio Ambiente: Madrid, 2012.

- Cameron, F. R. (2023). From Sustainable Development to Sustaining Practices for Human, More-than and Other-than Human Worlds. Museum International, 75(1–4), 214–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/13500775.2023.2348883. [CrossRef]

- NPA Nitidara, J Sarwono, S Suprijanto, FXN Soelami (2022). The multisensory interaction between auditory, visual, and thermal to the overall comfort in public open space: A study in a tropical climate. Sustainable Cities and Society 78, 103622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.103622. [CrossRef]

- Izembart, H. and Le Boudec, B. Waterscapes: el tratamiento de aguas residuales mediante sistemas vegetales. Editorial Gustavo Gili: Barcelona, Spain, 2003.

- Wang, M.; Zhuang, J.; Sun, C.; Wang, L.; Zhang, M.; Fan, C.; Li, J. The Application of Rain Gardens in Urban Environments: A Bibliometric Review. Land 2024, 13, 1702. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13101702. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).