Submitted:

22 December 2025

Posted:

24 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

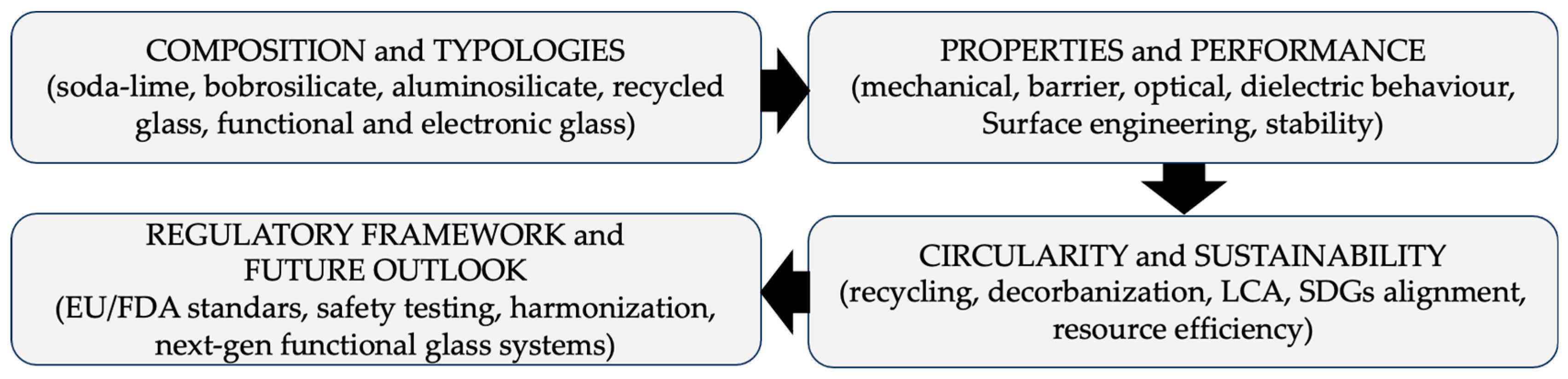

1. Introduction

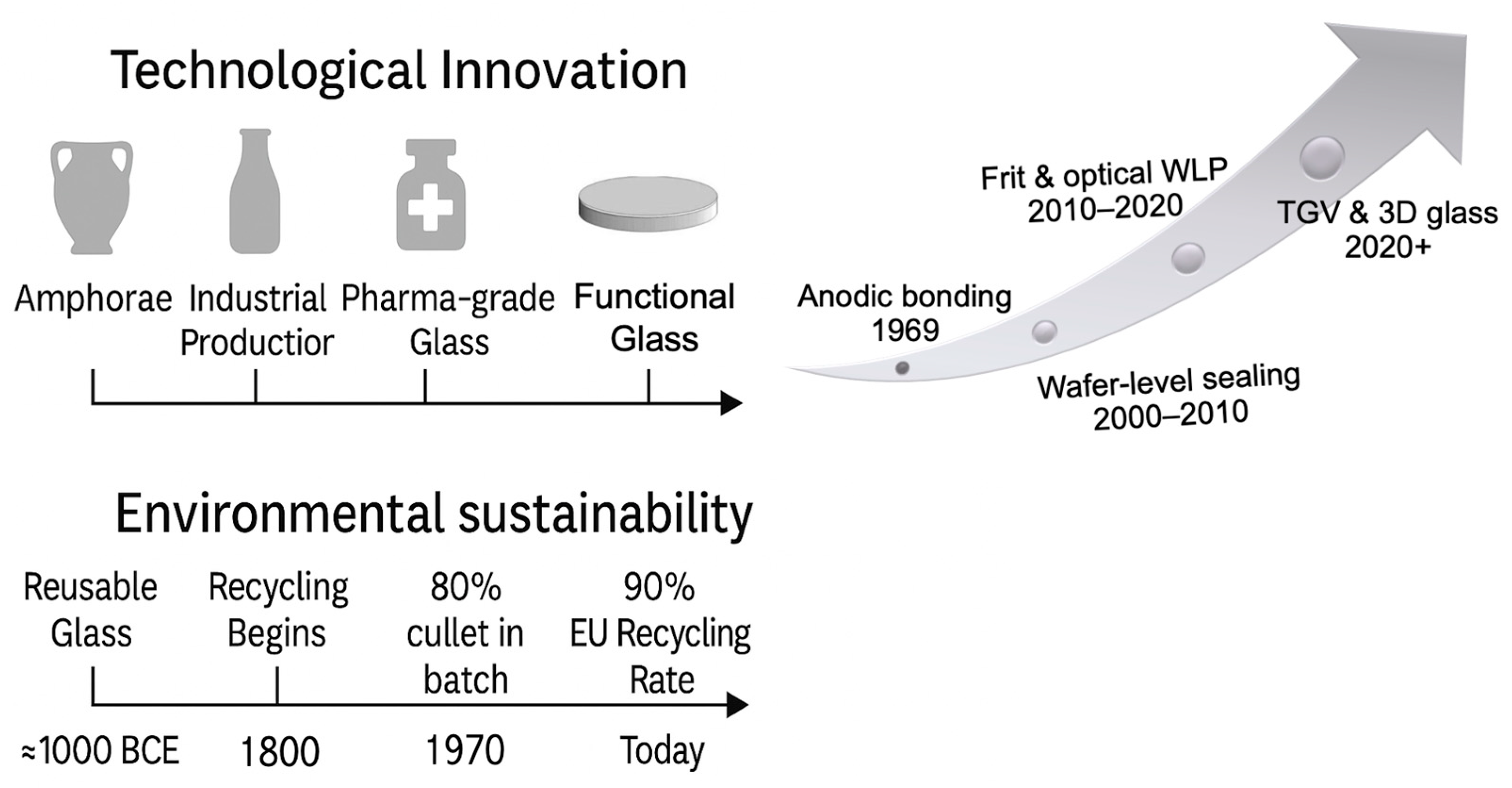

1.1. Historical and Technological Evolution of Packaging Glass

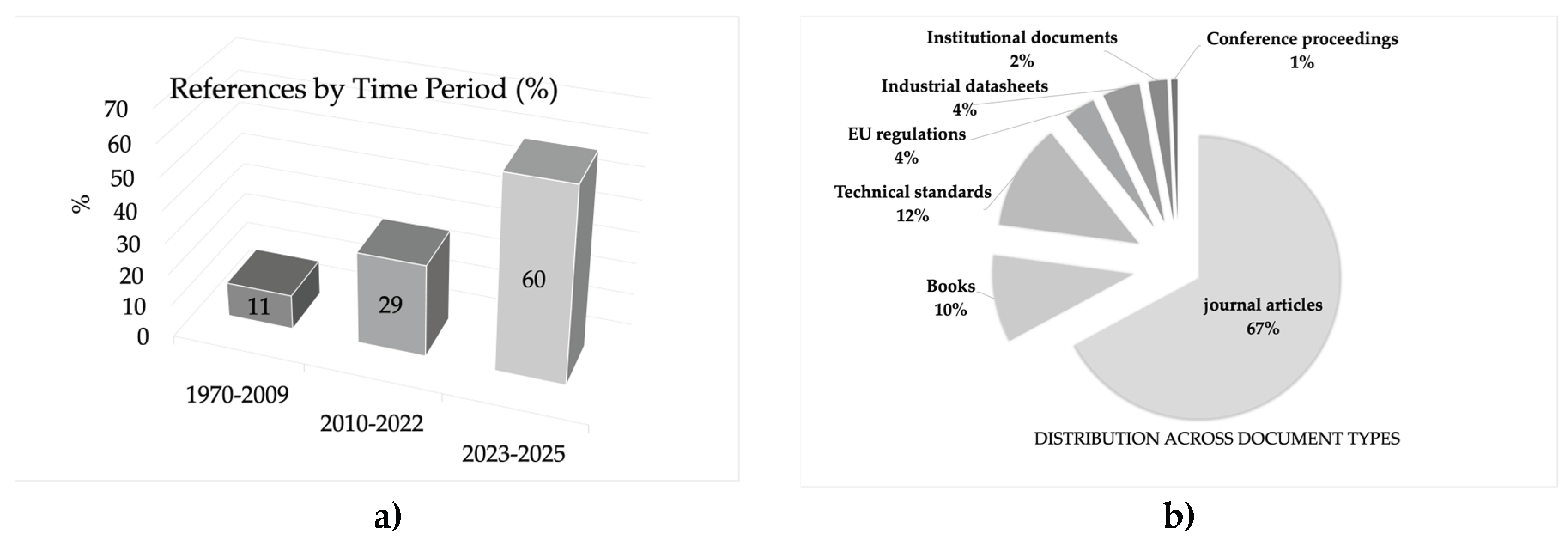

1.1. Methodological Note: Scope and Selection Criteria

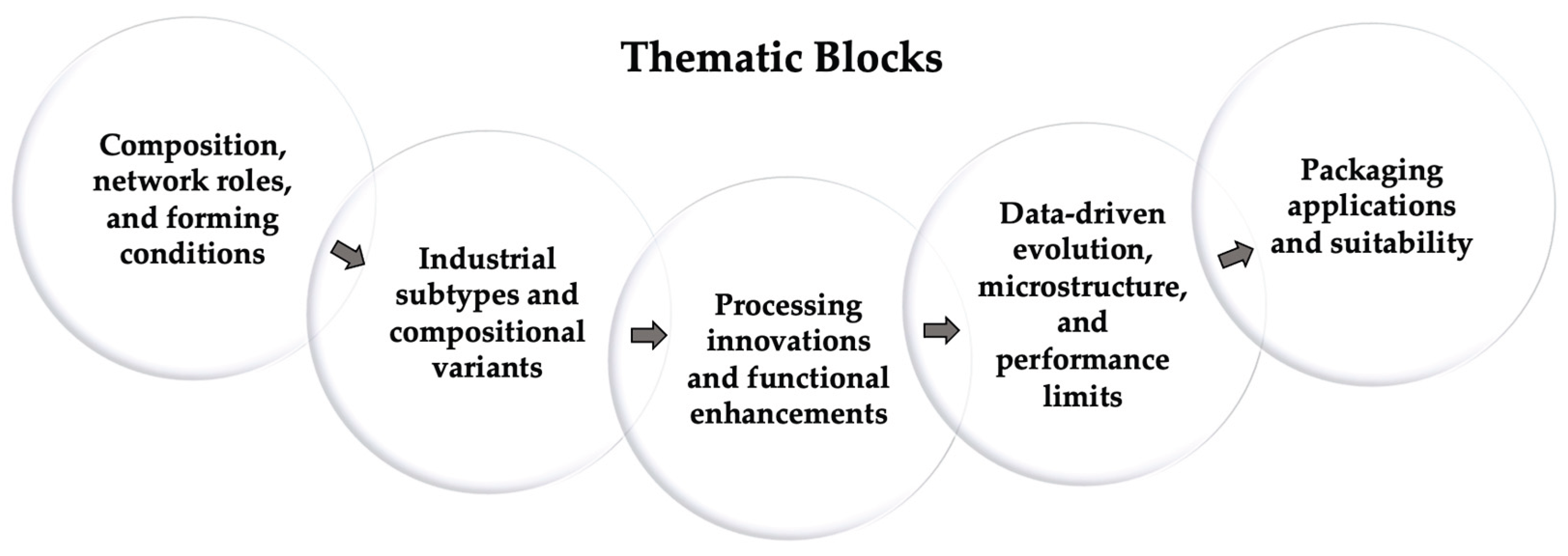

2. Typologies and Compositions of Packaging Glass

- (i)

- Composition, network roles, and forming conditions

- (ii)

- Industrial subtypes and compositional variants

- (iii)

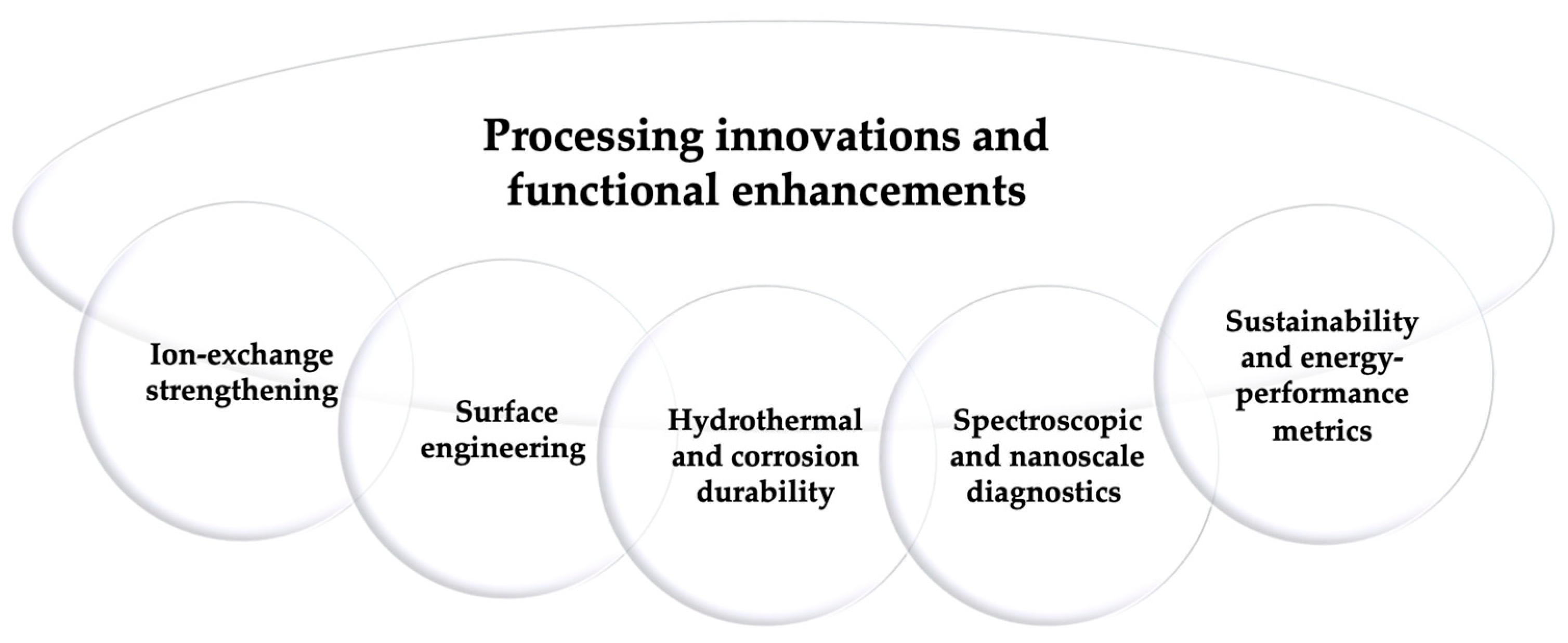

- Processing innovations and functional enhancements

- (iv)

- Data-driven evolution, microstructure, and performance limits

- (v)

- Packaging applications and suitability

2.1. Soda-Lime Glass for Packaging Applications

| Glass component | Primary function in packaging | Typical glass families and processes |

|---|---|---|

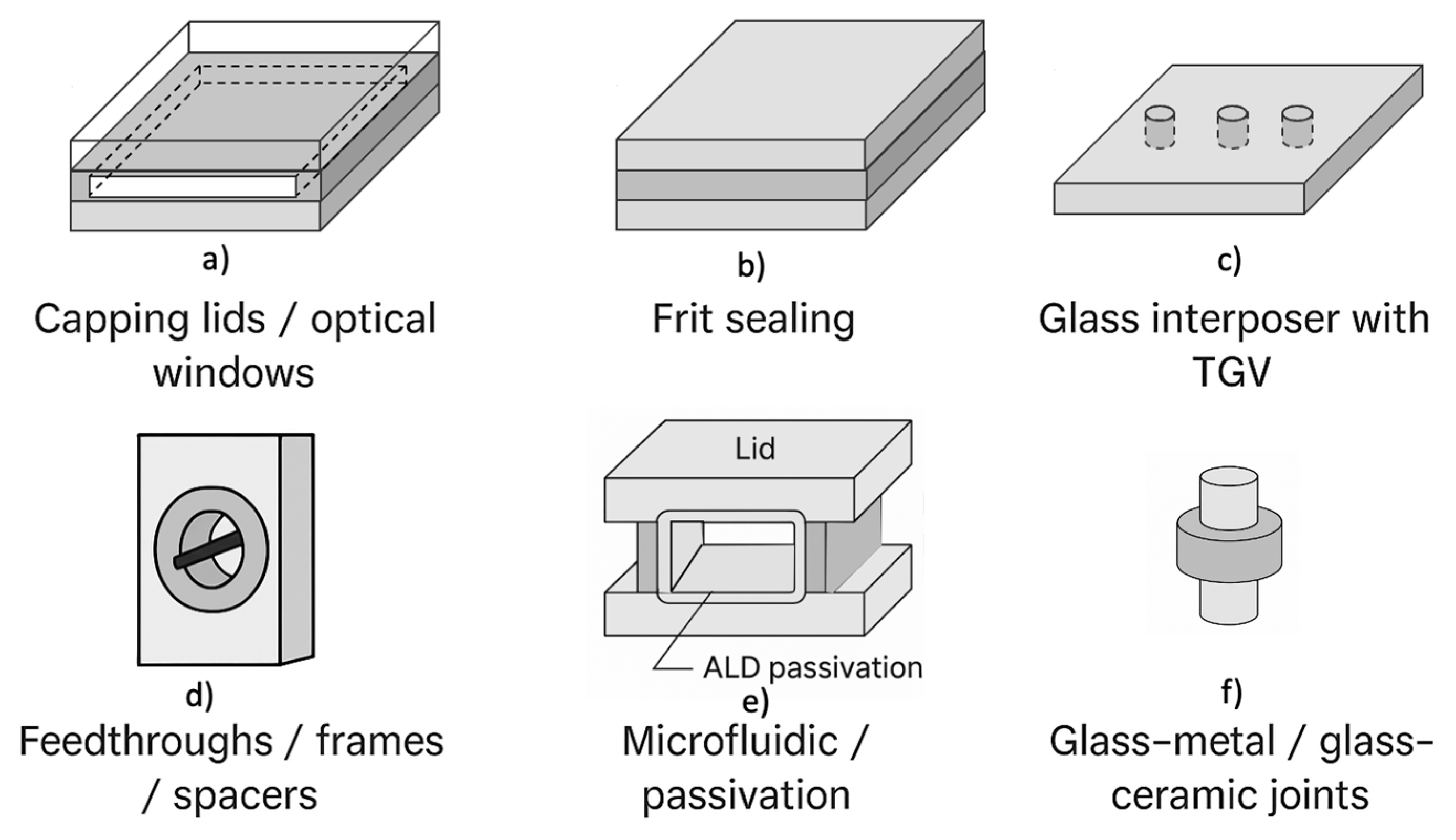

| Capping lids / optical windows |

Hermetic sealing, optical or IR transmission, mechanical protection of MEMS and sensors | Borosilicate (Pyrex, Borofloat), aluminosilicate, LAS glass-ceramics; anodic, frit, or laser bonding |

| Sealing layers / bonding frits |

Pb-free hermetic sealing, dielectric isolation, adhesion to metals or ceramics | Bi2O3–B2O3–ZnO, Ba–Zn–B2O3, phosphate-silicate frits; screen-printing, jet deposition, localized sintering |

| Substrates / interposers (TGV) |

Electrical insulation, vertical interconnection, dimensional stability | Alkali-free borosilicate or aluminoborosilicate; laser drilling, chemical etching, metallization, planarization |

| Feedthroughs / frames / spacers |

Mechanical alignment, electrical feedthrough, cavity definition | Borosilicate, aluminosilicate, glass-ceramic rings; diffusion or glass-to-metal bonding |

| Microfluidic chips / passivation layers | Chemical inertness, optical access, bio-compatibility, corrosion protection | Borosilicate–phosphate hybrids, ALD-coated aluminosilicates; wet etching, additive microfabrication |

| Glass–metal / glass–ceramic joints |

Long-term hermeticity and insulation in harsh environments | Borosilicate–aluminosilicate with ZrO2 or TiO2, LAS glass-ceramics; compression or diffusion sealing |

- Flint (colorless): obtained from low-iron batches (Fe2O3 ≤ 0.03–0.05 wt%) and used in food, beverage, and cosmetic packaging. Premium extra-flint variants employ ultra-low-iron sands and enhanced refining/decolorizing to maximize clarity for luxury beverages and perfumery.

- Amber: generated through controlled Fe–S–C chemistry and providing UV–visible attenuation up to ~450 nm, suitable for beer, nutraceuticals, and other light-sensitive products.

- Green (emerald/olive): obtained through regulated Fe and Cr oxide additions, widely used in beverage packaging (water, wine, oils) for aesthetic appeal and partial UV filtering.

2.2. Borosilicate Glass for Pharmaceutical and High-Stability Packaging

- Type I borosilicate – Used for primary pharmaceutical packaging complying with Hydrolytic Class I under USP <660> and ISO 4802 [68,70,71]. These compositions combine high silica, moderate boron, and very low alkali content to minimize ion exchange and pH shifts in injectables, while ensuring low thermal expansion and high surface durability. They are employed for vials, prefillable syringes, ampoules, and cartridges (Schaut 2014; Schaut 2017; Ditter 2018)[3,6,53].

- Technical borosilicate (e.g., Pyrex®, Duran®) – Glasses with very high silica and higher alkali levels than Type I, optimized for thermal-shock resistance, transparency, and durability over repeated washing or sterilization. They are not designed for extreme hydrolytic stability but are widely used in laboratory ware, bakeware, reagent bottles, and optical or photonic components (Schaut 2017)[3].

- Alkali-free borosilicate – Compositions with high silica and negligible alkali oxides, replaced by alkaline-earth modifiers to suppress ionic mobility. Their low permittivity and loss tangent enable hermetic and dielectric packaging in microelectronics, RF systems, and optoelectronic devices, including substrates, optical windows, cover glasses, and interposers (Rodríguez-Cano 2024; Liu 2025)[46,47].

- Ion-exchange strengthening

- Surface engineering

- -

- Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) produces nanometric Al2O3/SiO2 films with excellent uniformity, sealing microdefects and reducing protein adsorption while improving abrasion resistance (Rodríguez-Cano, 2024)[47].

- -

- Sol–gel nanocoatings allow tunable wettability and smoother inner surfaces, supporting drug recovery and mitigating residue formation.

- Hydrothermal and corrosion durability

- Spectroscopic and nanoscale diagnostics

- Sustainability and energy-performance metrics

2.3. Aluminosilicate Glass

- Alkali-bearing aluminosilicates — ion-exchangeable glasses combining high rigidity with the ability to develop strong compressive layers. They are used in chemically strengthened vials and cartridges, offering lower breakage, higher dimensional robustness, and reduced extractables versus Type I borosilicate (Schaut, 2014, Schaut, 2017) [3,6]. This is the only aluminosilicate class currently adopted in commercial primary packaging.

- Alkaline-earth aluminosilicates — used in displays, optical sealing, and functional/electronic packaging requiring low CTE; not used in direct-contact pharma packaging (Varshneya, 2019) [77].

- Low-alkali/alkali-free aluminosilicates — for displays and multilayer sealing requiring suppressed alkali mobility; not used in pharmaceutical primary contact (Bechgaard 2016) [80].

- High-alumina aluminosilicates — used in abrasion-resistant optical covers and high-temperature insulators; unsuitable for direct-contact packaging due to high softening temperature and limited ion exchange

- Ion-exchange strengthening

- Thermal history and pre-densification

- Sustainability and energy-performance metrics

- Composition and network effects

- Surface relaxation and crack initiation

- Ion-exchange and stress depth limitations

2.4. Recycled and Cullet-Rich Glass

- Green glass accommodates up to ≈95 wt% cullet because Fe–Cr chromophores tolerate mixed-colour feedstock, supporting beer and wine packaging.

- Amber glass typically includes 60–80 wt% cullet; Fe–S–C chromophores provide intrinsic UV shielding for light-sensitive beverages.

- Flint and extra-flint glass are generally limited to 30–50 wt% cullet since very low Fe2O3 levels are required to preserve brightness and colour uniformity (Gerace 2024) [13]; used for premium transparent containers.

- Pharmaceutical and diagnostic glass (borosilicates and high-alumina alkali-free compositions) accepts lower cullet fractions or uses dedicated take-back systems due to stringent durability and clarity requirements.

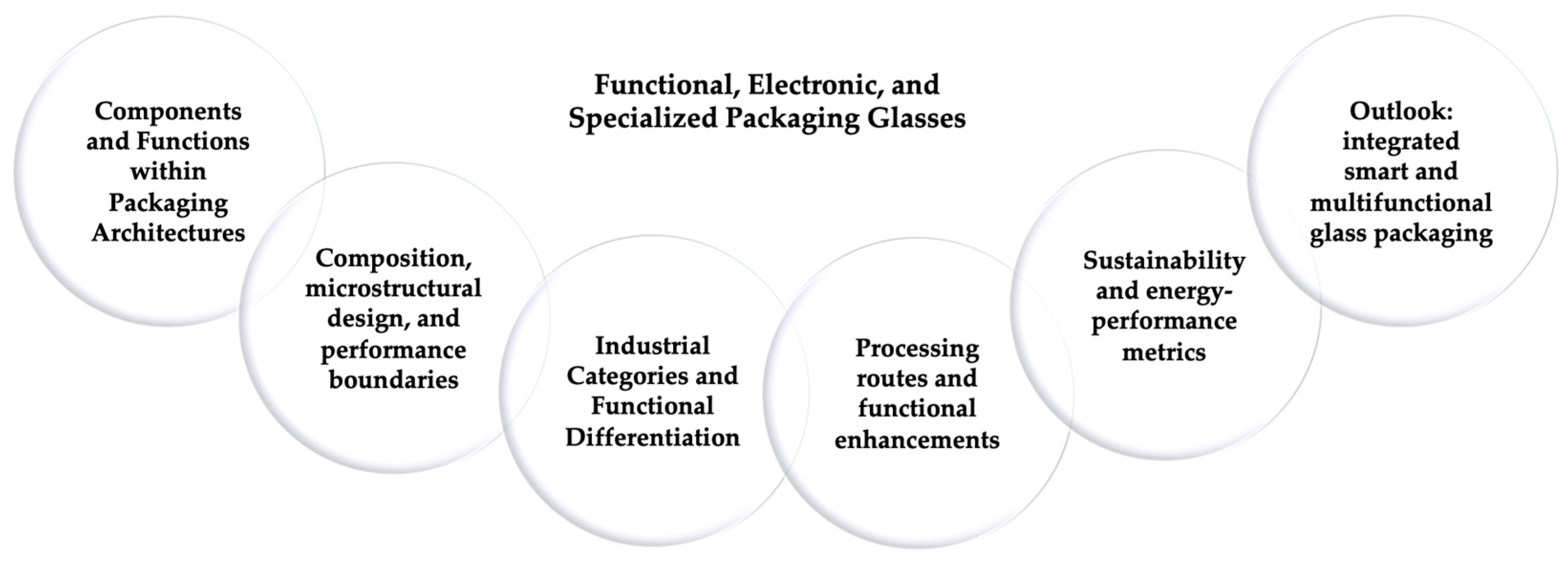

2.5. Functional, Electronic, and Specialized Packaging Glasses

- relative permittivity εᵣ ≈4–6 with dielectric loss tan δ < 0.005;

- thermal expansion CTE ≈3–5 × 10−6 K−1 for matching Si, GaN, and Al2O3;

- softening range ≈350–500 °C for low-energy frit or glass–ceramic sealing;

- optical transparency >90% in the relevant spectral window;

- flexural strength >400 MPa after ion exchange;

- water-vapour transmission <10−4 g m−2 day−1 with ALD barriers.

- hermetic leak rates < 10−8 mbar L s−1,

- CTE-matched interfaces within ±0.5 × 10−6 K−1,

- high mechanical reinforcement (surface σc > 400 MPa; strength gains 2–3×),

- optical retention > 90% after ion-exchange or coating,

- enhanced barrier performance, with moisture/ion permeability reduced by ×100,

- stable dielectric response, with εᵣ ≈ 4.5 and low loss under thermal/humidity stress.

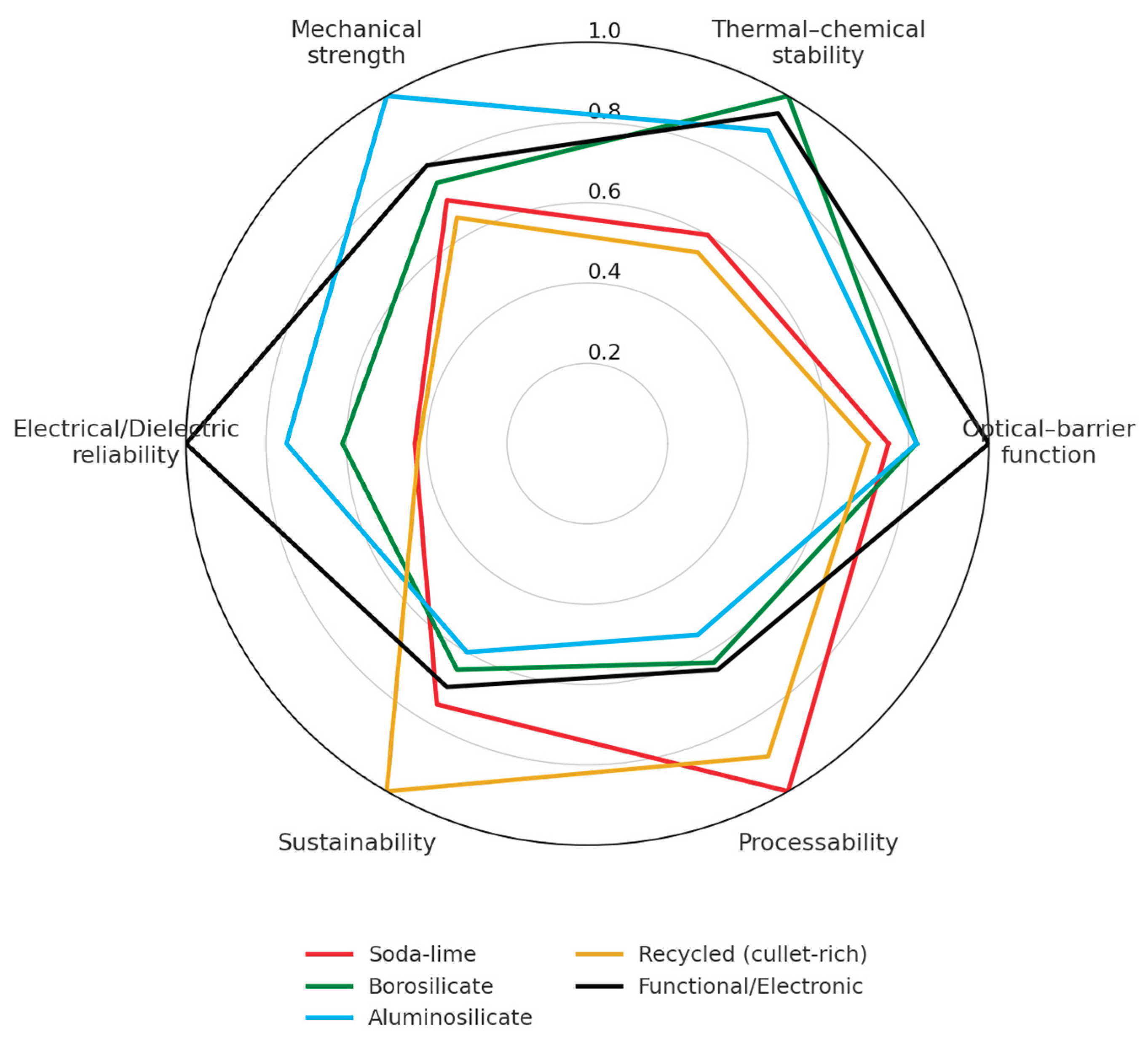

2.6. Comparative Overview

| Parameter (units) | Soda–lime | Type I/III Borosilicate | Aluminosilicate | Recycled (cullet-rich) |

| (Gerace 2024; Schaut 2017; Deng 2024, Deng 2025, Cao 2025, Przepióra 2025, Shelby 2020, Varshneya 2022 ) [3,13,64,65,66,77,103] | (Schaut 2014; Guadagnino 2022; Ditter 2018; Schaut 2017; Pintori 2023; Liu 2025; Pal 2024; Savvova 2025; Rodriguez-Cano 2024; Brunswic 2024)[3,6,46,47,53,55,56,57,69,104] | (Schaut 2014; Ditter 2018; Cormier 2021; Pal 2024; Abd-Elsatar 2024; Wang 2025; Gallo 2022; Belançon 2025)[6,17,25,27,53,54,56,105] | (Gerace 2024; Barbato 2024; Somogyi 2024; Savvova 2025; Wojnarowska 2025; Bristogianni 2023; Shelby 2020; Varshneya 2022) [12,13,21,57,77,85,92,103] | |

| Typical composition (wt%) | SiO2 70–74; Na2O 12–14; CaO 9–11; MgO 3–4; Al2O3 1–2. | SiO2 78–81; B2O3 12–13; Na2O/K2O 4–5; Al2O3 2–3. | SiO2 73–77; Al2O3 6–12; MgO/CaO 5–8; Na2O/K2O 3–5. | SiO2 69–73; Na2O 12–14; CaO 8–10; MgO 3–4; Al2O3 1–2; Fe2O3 0.1–0.7; Cr2O3 ≤0.3 (from flint/amber/green cullet mixtures) |

| Density (g cm−3) | 2.48–2.55 | 2.23–2.30 | 2.42–2.48 | 2.47–2.50 (till to ~2.55 for green cullet) |

| Young’s modulus (GPa) | 70–72 | 61–65 | 70–75 | 70–76 (measured on recycled soda-lime glass, IET/4PB) |

| Tensile strength (MPa) | 45–85 | 45–80 | 60–90 | 40–70 (≈70 flint → 55 amber → 45 green) |

| Compressive strength (MPa, typ.) | 800–1000 | 900–1100 | 1000–1200 | 850–950 (≈ –10% for green cullet) |

| Flexural strength (MPa) | 60–150 | 70–130 | 90–150 | 43.7–47.7 (annealed cullet-based specimens) |

| Hardness (HV, Vickers) | 540–580 | 530–560 | 600–650 | ≈ 540 ± 15 (≤ 10% variation) |

| Fracture toughness KIC (MPa m1ᐟ2) |

0.65-0.75 | 0.8-1 | 0.9-1.2 | 0.65–0.75 (nearly invariant) |

| Poisson’s ratio (–) | 0.22–0.24 | 0.20–0.22 | 0.21–0.23 | ≈ 0.23 (± 0.01) |

| CTE (10−6 K−1, 20–300 °C) | 8.5–9.0 | 3.2–3.4 | 3.8–4.2 | 8.5–8.8 (≈ 8.5 flint → 8.9 green) |

| Hydrolytic class (EU/Ph. Eur.) | II–III | I | I | II → I (for cullet > 60%; amber slightly more stable). |

| Optical / UV protection (qual.) | Clear/amber/green; amber or coatings for UV | High clarity; optional ALD/UV coatings | Colorless premium; coatings as needed | UV cut-off: ≈ 320 flint → 450 amber → 420 green nm. |

| Gas barrier (O2/H2O permeability) | Practically zero | Practically zero | Practically zero | Practically zero |

| Key characteristics (qual.) | High productivity; cost-efficient; good processability | Highest thermal/chemical stability; sterilizable | Highest stiffness/hardness; thin walls; premium look | Lowest footprint with high cullet; stable properties across remelts |

| Recyclability & cullet (qual.) | Fully recyclable; typical cullet 30–60% | Fully recyclable (specialized lines) | Fully recyclable (premium lines) | Fully recyclable; cullet 50–90%; quality depends on sorting and contaminants |

| Sustainability impact (LCA, indicative) | +10% cullet → ~3% energy ↓; GWP ~1.0–1.2 t CO2e/t | Higher melting T; offset by durability & reuse | Higher E; lightweighting compensated cost | +10% cullet → ≈ 3% ↓ energy; GWP 1.0–1.2 t CO2e t−1; regional loops cut emissions by ≈ 25% |

| Primary application sectors | Food & beverages; sauces; jars | Parenterals; diagnostics; hot-fill | Premium beverages; cosmetics; refillable containers | All sectors; deposit-return loops; amber preferred for light-sensitive products |

| Property | Borosilicate (high-purity, functional) | Fused Silica | Boro-Aluminosilicate | Aluminosilicate (ion-exchanged / technical) | Hybrid Aluminosilicate–Phosphate | Borosilicate–Aluminosilicate Hybrid | Low-Alkali Aluminosilicate |

| Reference | (Alhaji 2024; Abd-Elsatar 2024; Rodríguez-Cano 2024; Shelby 2020; Varshneya 2022; SCHOTT 2023; MIL-STD-883; Del Río 2022; Colangelo 2024; Ahmadi 2025) [17,47,77,100,103,107,108,109] | (Mazinani 2025; Shelby 2020; Varshneya 2022; Corning HPFS 2023; Heraeus Suprasil 2023; IFC Glass Benchmark 2021; Del Río 2022; Colangelo 2024)[24,77,101,102,103,107,110,111] | (Behera 2025; Shelby 2020; Varshneya 2022; Xiao 2016; Jiao 2017; Roshanghias 2022) [41,77,98,103,112,113] | (Nunes 2025, Belançon 2025; Shelby 2020; Varshneya 2022; Yazdi 2023; IFC 2021; Colangelo 2024) [25,77,81,103,107,110,114] | (Jiang 2025, Shelby 2020; Jiao 2017; Del Río 2022; Ahmadi 2025) [26,103,109,111,113] | (Lu 2019, Shelby 2020; Roshanghias 2022; Yazdi 2023; Colangelo 2024) [28,41,103,107,114] | (Wang 2025, Shelby 2020, Varshneya 2022; IFC 2021; Del Río 2022; Ahmadi 2025) [27,77,103,109,110,111] |

| Main Composition (wt%) | SiO2 77–80; B2O3 9–13; Na2O/K2O 4–6; Al2O3 2–6; CaO 1–2 | SiO2 >99.8 | SiO2 ≈70, B2O3 12, Al2O3 ≈10, BaO ≈3, ZnO ≈2 | SiO2 68–70, Al2O3 9–12, Na2O/K2O ≤3 | SiO2 60, Al2O3 10, P2O5 10, CaO 8, MgO 6, ZnO 4 | SiO2 74, B2O3 10, Al2O3 8, Na2O/K2O 4, CaO 3 | SiO2 67, Al2O3 11, MgO 7, BaO 5, ZnO 3 |

| CTE (×10−6 K−1) | 3.2-3.4* | 0.50-0.55 | ≈4.2 | 3.5–4.5* | ≈3.5* | 3.0–3.5* | 3.5–4.0 |

| Dielectric Strength (kV mm−1) | 20–40* | 20–25* | 16–18* | 18–22* | 15–20* | 14–16* | ≈20* |

| Permittivity ε′ (1 MHz) |

4.6–5.2 (lit.) | 3.8–4.0 (std.) | 6–8 (lit.) | 6.5–11 (lit.) | 12–18 (lit.) | 6–8 (lit.) | 6–8 (est.) |

| Loss tangent tan δ (1 MHz) | 0.003–0.008 (lit.) | 0.0001–0.0002 (std.) | 0.001–0.004 (lit.) | 0.002–0.01 (lit.) | 0.005–0.015 (lit.) | 0.001–0.004 (lit.) | 0.001–0.004 (est.) |

| Hermeticity (mbar·L·s−1) | ≤ 10−8–10−9 * | ≤ 10−9 * | ≤ 10−9 * | 10−8* | <10−8* | 10−8* | 10−8* |

| Optical Transmittance (%) | > 90 (400–700 nm) * |

>92 | 88–90 | 88-91 | 85–90* | 80–85* | >90* |

| Hardness (GPa) | 5.6-6.0 | ≈6.0* | ≈5.8 | 6.2–7.7 (measured; ≈ 620–773 HV) |

≈6.2* | ≈6.0* | ≈6.8* |

| Key characteristics (qual.) | Low-alkali, good CTE match to Si; stable dielectrics; low autofluorescence | Ultra-low CTE; highest optical purity; excellent radiation stability | Balanced CTE; good mechanical strength; compatible with low-T frit sealing | Chemically strengthenable; high surface hardness; impact-resistant cover glass | Low-temperature sealing; tailored CTE; good dielectric performance | Intermediate CTE; robust under thermal cycling; hermetic encapsulation | Stable permittivity; low ion migration; high dielectric reliability |

| Recyclability & cullet (qual.) | Not compatible with container-glass cullet; niche, small-scale recycling only | No established large-scale recycling; re-melting limited to specialty lines | Very limited recyclability; composition not accepted in soda-lime cullet loops | Very limited recyclability; composition not accepted in soda-lime cullet loops | No closed-loop routes; treated as specialty waste at end-of-life | No closed-loop routes; treated as specialty waste at end-of-life | Not accepted in mixed cullet; requires dedicated recovery to avoid contamination |

| Sustainability impact | Higher melting energy than container glass; low glass mass per device mitigates impact | Very high melting energy and CO2 per kg; use restricted to high-value components | Energy-intensive melting; Zn/Ba oxides raise environmental and end-of-life concerns | High energy demand for melting and ion exchange; long service lifetime partly offsets footprint | High energy demand for melting and ion exchange; long service lifetime partly offsets footprint | Specialty compositions; decarbonisation relies on furnace electrification and optimized batching | Specialty compositions; decarbonisation relies on furnace electrification and optimized batching |

| Main Application | Microfluidic chips, biosensors, RF/microwave substrates, pharma vials | Lab-on-chip, optical diagnostic systems | Sealing for biomedical cartridges | Displays, sensors, protective windows, LED/PV modules | Micro-battery sealing, MEMS | Nuclear waste immobilization, high-temperature sensors | Transparent hermetic coatings |

- Data coverage: Even for the functional glass families listed, experimental data remain discontinuous and partly derived from industrial datasheets and standards; values represent consolidated reference ranges rather than complete datasets.

- Terminological scope: The borosilicate and aluminosilicate families reported here correspond to high-purity, low-alkali functional glasses for optical, electronic, and hermetic uses. They differ from the Type I/III borosilicate and high-alumina soda–lime (aluminosilicate) container glasses summarized in Table 2.

- Permittivity and dielectric loss values are included only where consistent data are available.

3. Properties-Based Performance of Packaging Glass Families

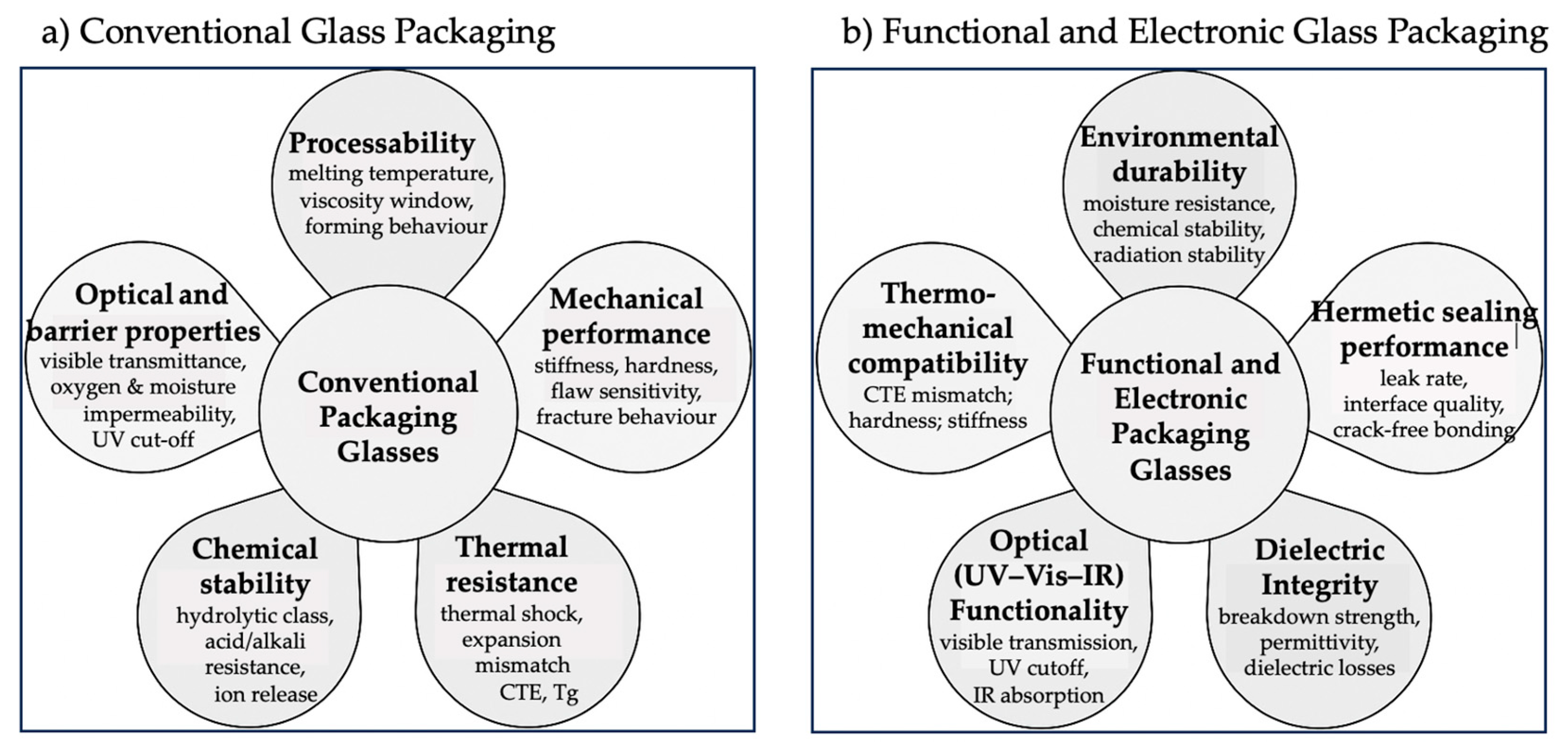

3.1. Conventional Packaging Glasses

3.1.1. Physical and Mechanical Properties

3.1.2. Thermal Properties and Shock Resistance

3.1.3. Chemical Stability and Corrosion Resistance

3.1.4. Optical and Barrier Properties

3.1.5. Processability and Lightweighting

3.1.6. Property–Driven Positioning of Glass Families in Packaging Applications

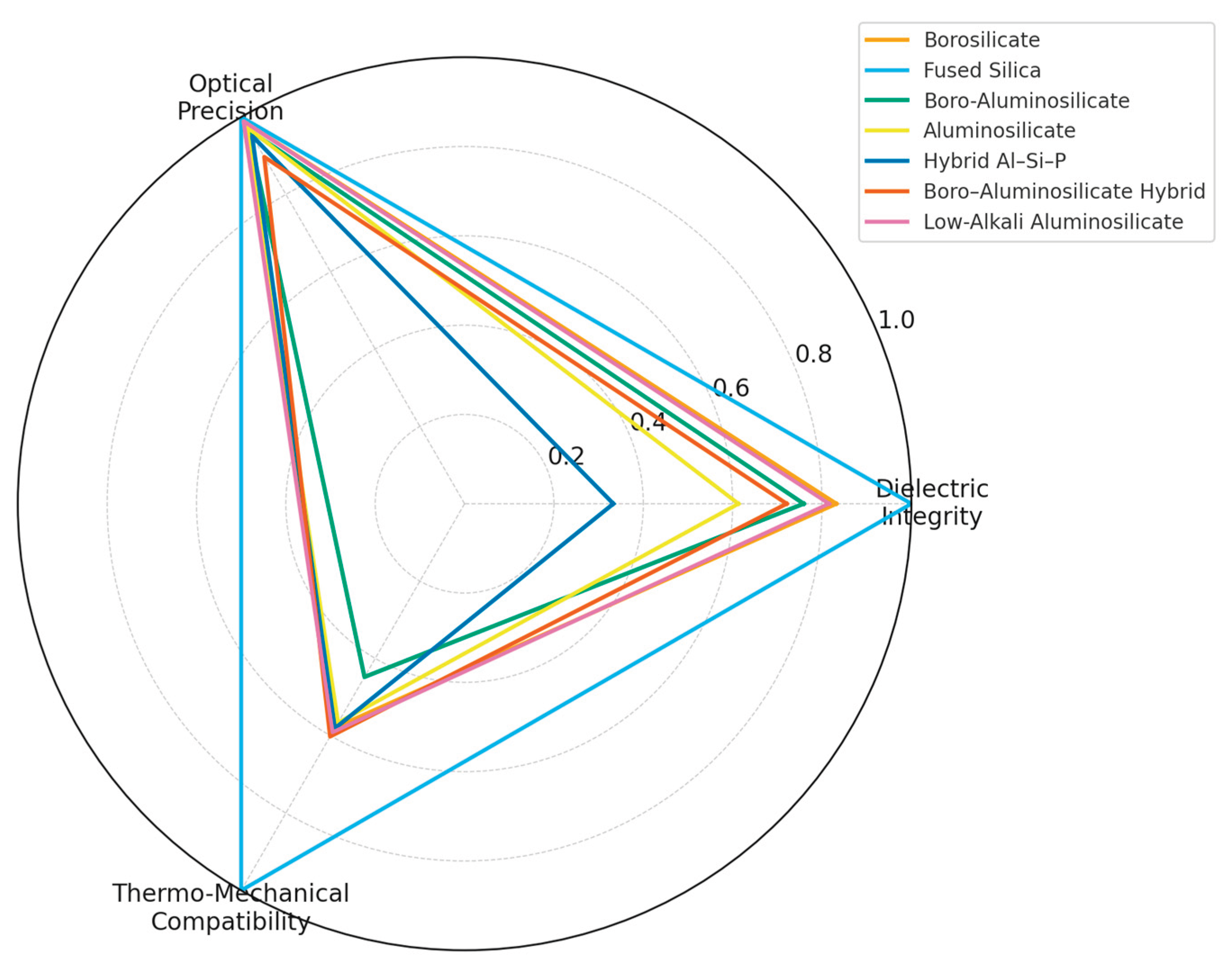

3.2. Functional and Electronic Packaging Glasses

3.2.1. Hermeticity

3.2.2. Dielectric Performance

3.2.3. Optical Functionality in the UV–Visible–IR Range

3.2.4. Thermal–Mechanical Compatibility

3.2.5. Environmental Durability

3.2.6. From Functional Domains to Electronic and Functional Packaging Architectures

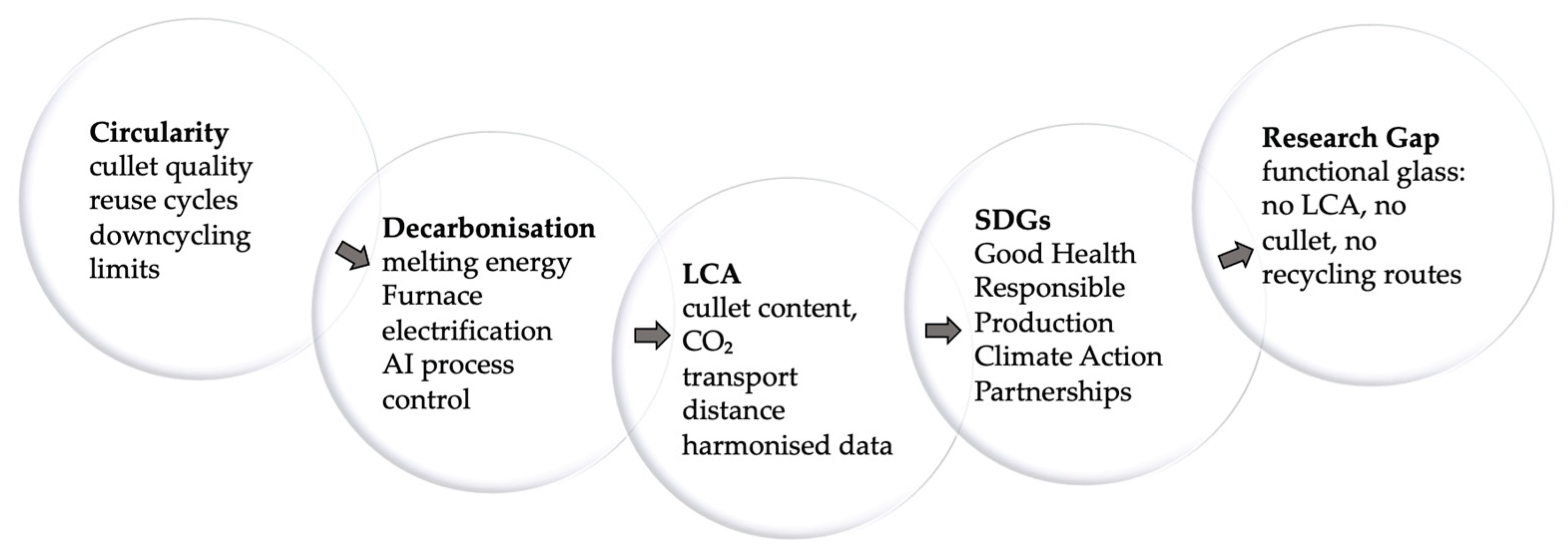

4. Circularity and Sustainability of Packaging Glass

4.1. Circularity of Container Glass

4.2. Energy Demand and Decarbonisation of Container Glass

4.3. Life-Cycle Assessment Indicators for Container Glass

4.4. SDG Alignment of Container Glass

4.5. Research Gap for Functional and Electronic Packaging Glasses

5. Regulatory Framework and Future Outlook

5.1. Food-Contact and Pharmaceutical Compliance

- Migration behaviour for pharmaceutical use is evaluated according to the European Pharmacopoeia, Chapter 3.2.1 (Glass containers for pharmaceutical use)[125] and USP <660> (Containers—Glass) [68]. These chapters define limits for pH change, extractable alkalinity, and specific ion release after autoclaving or sterilisation, as well as the procedures for surface and whole-container tests.

- Compositional restrictions are included in the same pharmacopeial chapters, which list allowable glass families (borosilicate, soda-lime, aluminosilicate), specify acceptable oxide systems, and prohibit certain toxic elements—such as Pb, Cd or As—in primary packaging for parenteral preparations.

5.2. Standards for Recycling, Reuse, and Emission Control

5.3. Digitalization and Traceability

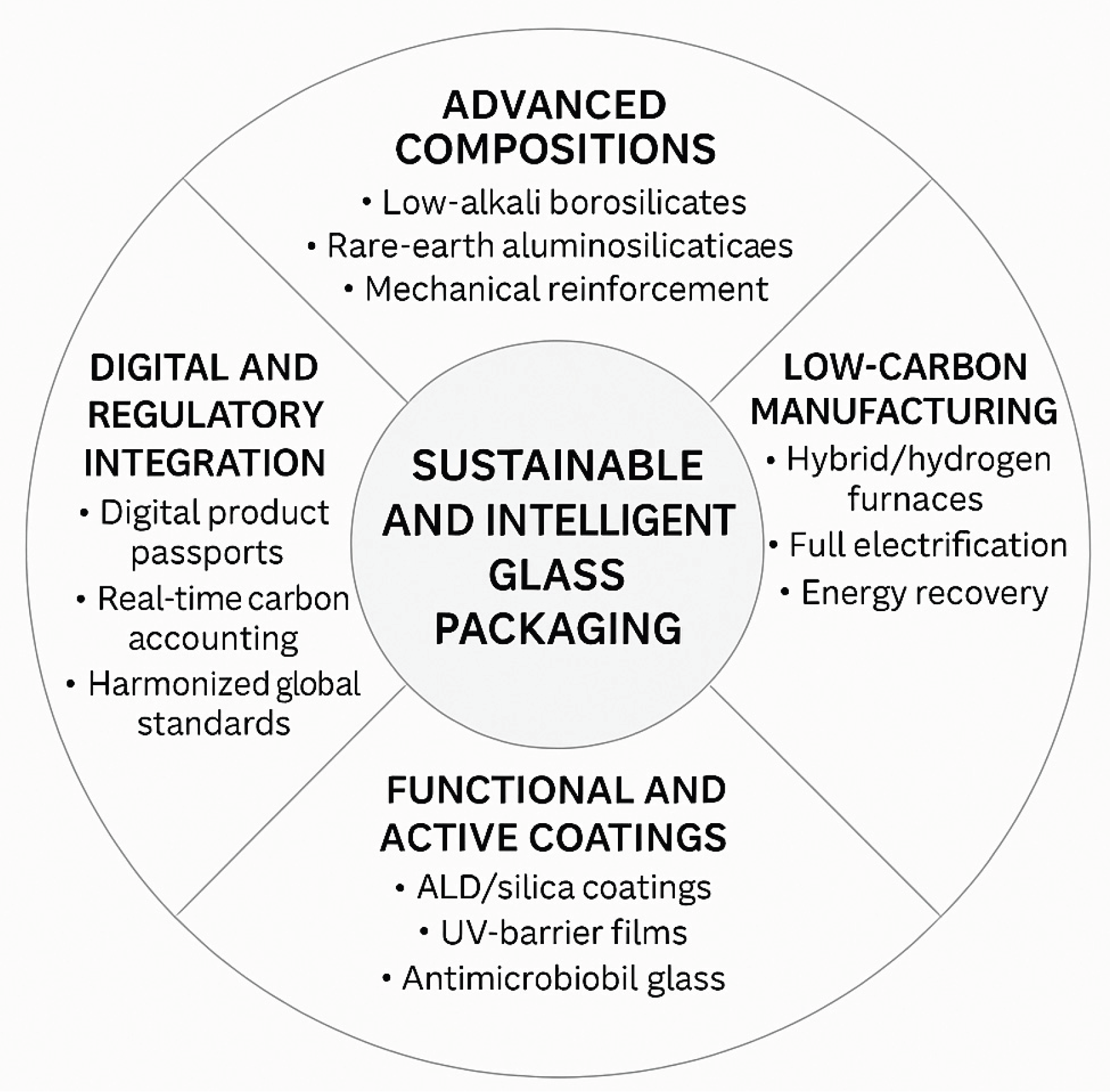

5.4. Future Outlook

5.5. Regulatory Gaps and Implementation Barriers

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Perspectives

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Lowe, C.M.; Elkin, W.I. Beer Packaging in Glass and Recent Developmens. Journal of the Institute of Brewing 1986, 92, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.; Valdés, A.; Mellinas, A.; Garrigós, M. New Trends in Beverage Packaging Systems: A Review. Beverages 2015, 1, 248–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaut, R.A.; Weeks, W.P. Historical Review of Glasses Used for Parenteral Packaging. PDA Journal of Pharmaceutical Science and Technology 2017, 71, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnotta, L. Packaging Materials: Past, Present and Future. CMS 2024, 17, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, H.; Dutta, U. Trends in Beverage Packaging. In Trends in Beverage Packaging; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 1–19. ISBN 978-0-12-816683-3. [Google Scholar]

- Schaut, R.A.; Peanasky, J.S.; DeMartino, S.E.; Schiefelbein, S.L. A New Glass Option for Parenteral Packaging. PDA Journal of Pharmaceutical Science and Technology 2014, 68, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinci, G.; D’Ascenzo, F.; Esposito, A.; Musarra, M.; Rapa, M.; Rocchi, A. A Sustainable Innovation in the Italian Glass Production: LCA and Eco-Care Matrix Evaluation. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 223, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinci, G.; D’Ascenzo, F.; Esposito, A.; Musarra, M. Glass Beverages Packaging: Innovation by Sustainable Production. In Trends in Beverage Packaging; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 105–133. ISBN 978-0-12-816683-3. [Google Scholar]

- Serna Saiz, J.; Ahumada Forigua, D.A.; Sánchez García, P.L. Impact of Glass Packaging Leaching on the Uncertainty of Inorganic Standard Solutions. Anal Bioanal Chem 2025, 417, 2741–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.U.A.; Ahmad, S.; Butt, S.I. Environmental Impact Assessment of the Manufacturing of Glass Packaging Solutions: Comparative Scenarios in a Developing Country. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2023, 102, 107195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacocca, R.G.; Toltl, N.; Allgeier, M.; Bustard, B.; Dong, X.; Foubert, M.; Hofer, J.; Peoples, S.; Shelbourn, T. Factors Affecting the Chemical Durability of Glass Used in the Pharmaceutical Industry. AAPS PharmSciTech 2010, 11, 1340–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbato, P.M.; Olsson, E.; Rigamonti, L. Quality Degradation in Glass Recycling: Substitutability Model Proposal. Waste Management 2024, 182, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerace, K.S.; Mauro, J.C. Characterization of Soda–Lime Silicate Glass Bottles to Support Recycling Efforts. Int J Ceramic Engine & Sci 2024, 6, e10217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, C.; De Feo, G.; Picone, V. LCA of Glass Versus PET Mineral Water Bottles: An Italian Case Study. Recycling 2021, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Feo, G.; Ferrara, C.; Minichini, F. Comparison between the Perceived and Actual Environmental Sustainability of Beverage Packagings in Glass, Plastic, and Aluminium. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 333, 130158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, C.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hengst, L.; Liu, X.; Toth, R.; Rodriguez, J.; Mohammad, A.; Bandaranayake, B.M.B.; et al. Quality Attributes and Evaluation of Pharmaceutical Glass Containers for Parenterals. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2019, 568, 118510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamal Abd-Elsatar, A.; Elsayed, H.; Kanková, H.; Hruška, B.; Kraxner, J.; Bernardo, E.; Galusek, D. Ion-Exchange Enhancement of Borosilicate Glass Vials for Pharmaceutical Packaging. Open Ceramics 2024, 20, 100689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, C.R.; Kim, H.D.; Jang, Y.-C. Exploring Glass Recycling: Trends, Technologies, and Future Trajectories. Environmental Engineering Research 2024, 30, 240241–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, F.; De-la-Torre, G.E.; KalantarHormozi, M.R.; Schmidt, T.C.; Dobaradaran, S. A Review of Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals Migration from Food Contact Materials into Beverages. Chemosphere 2024, 355, 141760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manninen, I.; Ritasalo, R.; Hirsjärvi, S. Improved Properties of Glass Vials for Primary Packaging with Atomic Layer Deposition. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2024, 113, 3354–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somogyi, A.; Chesnot, V. Glass Packaging and Its Contribution to the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Int J of Appl Glass Sci 2024, 15, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balassa, B.E.; Koteczki, R.; Csiba-Herczeg, Á. Traditional or Alternative Wine Packaging: A Study of Consumer Choices and Perceptions. International Journal of Urban Sciences 2025, 29, 314–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aralekallu, S.; Boddula, R.; Singh, V. Development of Glass-Based Microfluidic Devices: A Review on Its Fabrication and Biologic Applications. Materials & Design 2023, 225, 111517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazinani, B.; Fadlelmula, M.M.; Subramanian, V. Highly Stable Low-Temperature Phosphate Glass as a Platform for Multimaterial 3D Printing of Integrated Functional Microfluidic Devices. Adv Eng Mater 2025, 2501603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belançon, M.P.; Sandrini, M.; Zanuto, V.S.; Muniz, R.F. Glassy Materials for Silicon-Based Solar Panels: Present and Future. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 2023, 619, 122548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Yin, X.; Chen, Y.; Xu, L.; Zeng, X.; Wu, L. Preparation and Phase Evolution of Borosilicate Glass/Glass-Ceramic Waste Forms for Immobilizing High-Level Radioactive Sludge. Ceramics International 2025, 51, 27423–27435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Shah, A.; Lee, H.; Lee, C.H. Microfluidic Technologies for Wearable and Implantable Biomedical Devices. Lab Chip 2025, 25, 4542–4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Ren, M.; Deng, L.; Benmore, C.J.; Du, J. Structural Features of ISG Borosilicate Nuclear Waste Glasses Revealed from High-Energy X-Ray Diffraction and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Journal of Nuclear Materials 2019, 515, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risch, S.J. Food Packaging History and Innovations. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 8089–8092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corning Incorporated. Corning 7740 Glass – Technical Data Sheet; Corning Inc.: Corning, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rosemarie Trentinella Roman Glass - The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2003.

- Ni, H. A Brief Analysis of the Production and Circulation of Glass Containers from the Wei, Jin to the Sui and Tang Dynasties. 2025, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Verità, M. Venetian Innovations in Glassmaking and Their Influence on the European Glass History. Actes du Deuxieme Colloque Inteernational de l’Association Verre, Nancy, 26-28 Mars 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brill, R.H. Chemical Analyses of Early Glasses. 1-2-3; Corning Museum of Glass: Corning, NY, 1999; ISBN 978-0-87290-142-1. [Google Scholar]

- Freestone, I.C. The Archaeometry of Glass. In Handbook of Archaeological Sciences; Pollard, A.M., Armitage, R.A., Makarewicz, C.A., Eds.; Wiley, 2023; pp. 885–910. ISBN 978-1-119-59204-4. [Google Scholar]

- EPA AP 42 AP 42, Fifth Edition, Volume I Chapter 11.15: Mineral Products Industry - Glass Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the AP 42, Fifth Edition, Volume I Chapter 11: Mineral Products Industry; Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards, Research Triangle Park, NC., 1986.

- Okwuobi, S.; Ishola, F.; Ajayi, O.; Salawu, E.; Aworinde, A.; Olatunji, O.; Akinlabi, S.A. A Reliability-Centered Maintenance Study for an Individual Section-Forming Machine. Machines 2018, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzol, D.K.; Roos, C. State of the Art Container Glass Forming. In Additive Manufacturing of Glass; Elsevier, 2025; pp. 159–186. ISBN 978-0-323-85488-7. [Google Scholar]

- Wallis, George; Pomerantz, Daniel I. Field Assisted Glass-Metal Sealing. J. Appl. Phys. 1969, 40, 3946–3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S. Wafer-Level Hermetic MEMS Packaging by Anodic Bonding and Its Reliability Issues. Microelectronics Reliability 2014, 54, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshanghias, A.; Bardong, J.; Binder, A. Glass Frit Jetting for Advanced Wafer-Level Hermetic Packaging. Materials 2022, 15, 2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianchandani, Yogesh B.; Tabata, Osamu; Zappe, Hans. O. Brand 1.15 Packaging Comprehensive Microsystems; Elsevier, 2008; ISBN 978-0-444-52190-3. [Google Scholar]

- Demirhan Aydin, G.; Akar, O.S.; Akin, T. Wafer Level Vacuum Packaging of MEMS-Based Uncooled Infrared Sensors. Micromachines 2024, 15, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yu, D.; Zhong, Y. Development of 3D Wafer Level Hermetic Packaging with Through Glass Vias (TGVs) and Transient Liquid Phase Bonding Technology for RF Filter. Sensors 2022, 22, 2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Chen, H.; Fu, H.; Liang, T.; Gao, L.; Deng, B.; Zhang, J. Structural and Performance Variations of Aluminoborosilicate Glass Substrates with Mixed Alkaline Earth Effect for Applications in 3D Integrated Packaging. Ceramics International 2024, 50, 38089–38095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liang, T.; Zheng, W.; Liu, Y.; Fu, H.; Liu, Q.; Wu, C.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Gao, L.; et al. Effects of Al2O3 on the Coefficient of Thermal Expansion and Dielectric Properties of Borosilicate Glasses as an Interposer for 3D Packaging. Ceramics International 2025, 51, 3404–3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Cano, R.; Clark, N.L.; Mauro, J.C.; Lanagan, M.T. Borosilicate Glass with Low Dielectric Loss and Low Permittivity for 5G/6G Electronic Packaging Applications. AIP Advances 2024, 14, 115105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; Chen, C.; Li, A.; Chen, C.; Yu, H.; Zhang, L.; Tao, H.; Zeng, H.; et al. Creating Single-Crystalline β-CaSiO3 for High-Performance Electronic Packaging Substrate. Advanced Materials 2025, 37, 2414156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, A.; Zhong, C.; Zhang, L.; Lu, K.; Zeng, H. Regulating the Valence State of Lead Ions in Lead Aluminosilicate Glass to Improve the Passivation Performance for Advanced Chip Packaging. Applied Surface Science 2024, 651, 159208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Wu, S.; Zhong, Y.; Xu, R.; Yu, T.; Zhao, J.; Yu, D. Application of Through Glass Via (TGV) Technology for Sensors Manufacturing and Packaging. Sensors 2023, 24, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Pan, K.; Park, S. Thermo-Mechanical Reliability of Glass Substrate and Through Glass Vias (TGV): A Comprehensive Review. Microelectronics Reliability 2024, 161, 115477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaut, R.A.; Weeks, W.P. Historical Review of Glasses Used for Parenteral Packaging. PDA Journal of Pharmaceutical Science and Technology 2017, 71, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ditter, D.; Mahler, H.-C.; Roehl, H.; Wahl, M.; Huwyler, J.; Nieto, A.; Allmendinger, A. Characterization of Surface Properties of Glass Vials Used as Primary Packaging Material for Parenterals. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2018, 125, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, L. Glasses: Aluminosilicates. In Encyclopedia of Materials: Technical Ceramics and Glasses; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 496–518. ISBN 978-0-12-822233-1. [Google Scholar]

- Brunswic, L.; Angeli, F.; Charpentier, T.; Gin, S.; Asplanato, P.; Kaya, H.; Kim, S.H. Comparative Study of the Structure and Durability of Commercial Silicate Glasses for Food Consumption and Cosmetic Packaging. npj Mater Degrad 2024, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, R.; Pandey, P.; Thakur, S.K.; Khadam, V.K.R.; Dutta, P.; Chawra, D.H.S.; Singh, D.R.P. The Significance of Pharmaceutical Packaging and Materials in Addressing Challenges Related to Unpacking Pharmaceutical Products. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Savvova, O.; Falko, T.; Fesenko, O.; Klymov, M.; Smyrnova, Y. Efficiency of Thermochemical Treatment in Pharmaceutical Glass Production Under Plant Conditions. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2025, 1499, 012047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhu, T.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, K.; Meng, Z.; Huang, J.; Cai, W.; Lai, Y. Recent Advances in Functional Cellulose-Based Materials: Classification, Properties, and Applications. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2024, 6, 1343–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerkens, R. Analysis of Elementary Process Steps in Industrial Glass Melting Tanks - Some Ideas on Innovations in Industrial Glass Melting. Ceramics-Silikaty 2008, 52, 206–217. [Google Scholar]

- FEVE-European Container Glass Federation FEVE. Available online: https://feve.org (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Sani, G.; Sajzew, R.; Limbach, R.; Sawamura, S.; Koike, A.; Wondraczek, L. Surface Hardness and Abrasion Threshold of Chemically Strengthened Soda-Lime Silicate Glasses After Steam Processing. Glass Eur 2023, 1, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, D.; Bao, Y. Inspection of Defective Glass Bottle Mouths Using Machine Learning. J. Imaging 2025, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monegaglia, F.; Peghini, N.; Lenzi, E.; Bettio, S.; Calanca, P.; Dallapiccola, D.; Bertolli, A.; Mazzola, M. A Physics-Informed AI Control System for Enhanced Safety and Automation in Hollow Glass Manufacturing. Procedia Computer Science 2025, 253, 3123–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Wakelin, E.; Kilinc, E.; Bingham, P.A. A Survey of Commercial Soda–Lime–Silica Glass Compositions: Trends and Opportunities I—Compositions, Properties and Theoretical Energy Requirements. Int J of Appl Glass Sci 2025, 16, e16691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Qin, Y.; Cao, X.; Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Xu, S.; Lin, Y.; Cao, W.; He, C. Crack Path Competition and Biomimetic Toughening Strategy in Soda-Lime Glass: Experimental Study and Phase-Field Simulation. Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics 2025, 139, 105092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przepiora, K.; Zanotto, E.D.; Krishnan, N.; Ragoen, C.; Godet, S. Mechanical Properties and Deformation Mechanisms of Phase-Separated Soda-Lime-Silica Glass. Materialia 2025, 39, 102349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Fu, H.; Xie, H.; Chen, H.; Gao, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y. Effect of Different Ba/Sr Ratios on the Properties of Borosilicate Glasses for Application in 3D Packaging. Ceramics International 2024, 50, 41648–41653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Pharmacopeial Convention USP Containers-Glass. In USP 47 – NF 42; Rockville, MD, USA, 2024.

- Pintori, G.; Panighello, S.; Pinato, O.; Cattaruzza, E. Insights on Surface Analysis Techniques to Study Glass Primary Packaging. Int J of Appl Glass Sci 2023, 14, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO) ISO 4802-2; Glassware — Hydrolytic Resistance of the Interior Surfaces of Glass Containers — Part 2: Determination by Flame Spectrometry and Classification. 2023.

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO) ISO 4802-1; Glassware — Hydrolytic Resistance of the Interior Surfaces of Glass Containers — Part 1: Determination by Titration Method and Classification. 2023.

- Jung, J.; Woo, S.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.-J. Enhancing Borosilicate Glass Vials through Chemical Strengthening. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 2025, 664, 123596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Packaging and Packaging Waste, Amending Regulation (EU) 2019/1020 and Directive (EU) 2019/904, and Repealing Directive 94/62/EC. Official Journal of the European Union 2024, COM, 677 Final. [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, S.; Suneel, G.; Selvakumar, J.; Biswas, K.; Manna, S.; Nag, S.; Ambade, B. Synthesis and Characterization of Multi-Component Borosilicate Glass Beads for Radioactive Liquid Waste Immobilisation. Journal of Nuclear Materials 2025, 604, 155485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourguignon, M. Borosilicate Glasses: From Viscoplasticity to Indentation Cracking? Thèse de doctorat de Physique Chimie des matériaux, Sorbonne Université, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Naumov, A.S.; Sigaev, V.N. Transparent Lithium-Aluminum-Silicate Glass-Ceramics (Overview). Glass Ceram 2024, 80, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshneya, Arun K. Fundamentals of Inorganic Glasses, 2nd ed.; Elsevier, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes, F.J.V.; Garza-García, M.; López-Cuevas, J.; Chavarría, C.A.G.; Rendón-Angeles, J.C. Study of a Mixed Alkaline-Earth Effect on Some Properties of Glasses of the CaO-MgO-Al2O3-SiO2 System. Bol. Soc. Esp. Ceram. V. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Jin, L.; Wang, H.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Han, J. Structural Origin of the Mixed Alkaline Earth Effect in Alkali-free Aluminosilicate Glasses Revealed by AIMD Simulations. J Am Ceram Soc. 2025, e70295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechgaard, T.K.; Goel, A.; Youngman, R.E.; Mauro, J.C.; Rzoska, S.J.; Bockowski, M.; Jensen, L.R.; Smedskjaer, M.M. Structure and Mechanical Properties of Compressed Sodium Aluminosilicate Glasses: Role of Non-Bridging Oxygens. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 2016, 441, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, B.M.F.; Dinis, A.; Fernandes, J.C.; Almeida, R.M.; Santos, L.F. Mechanical Behavior of Ion-Exchanged Alkali Aluminosilicate Glass Ceramics. Crystals 2024, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Nam, J.; Ko, J.; Kim, S. Influence of Pre-Heat Treatment on Glass Structure and Chemical Strengthening of Aluminosilicate Glass. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 2023, 609, 122266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pönitzsch, A.; Nofz, M.; Wondraczek, L.; Deubener, J. Bulk Elastic Properties, Hardness and Fatigue of Calcium Aluminosilicate Glasses in the Intermediate-Silica Range. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 2016, 434, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbari, S.A.; Hof, L.A. Glass Waste Circular Economy - Advancing to High-Value Glass Sheets Recovery Using Industry 4.0 and 5.0 Technologies. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 462, 142629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnarowska, M.; Muradin, M.; Paiano, A.; Ingrao, C. Recycled Glass Bottles for Craft-Beer Packaging: How to Make Them Sustainable? An Environmental Impact Assessment from the Combined Accounting of Cullet Content and Transport Distance. Resources 2025, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallucci, T.; Lagioia, G.; Piccinno, P.; Lacalamita, A.; Pontrandolfo, A.; Paiano, A. Environmental Performance Scenarios in the Production of Hollow Glass Containers for Food Packaging: An LCA Approach. Int J Life Cycle Assess 2021, 26, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zero West Europe HOW-CIRCULAR-IS-GLASS 2025.

- Caspers, J.; Bade, P.; Finkbeiner, M. Reusable Beverages Packaging: A Life Cycle Assessment of Glass Bottles for Wine Packaging. Cleaner Engineering and Technology 2025, 25, 100914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, A.; Parker, J.M. The Sustainable Magic of Glass. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2023, 138, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loryuenyong, V.; Panyachai, T.; Kaewsimork, K.; Siritai, C. Effects of Recycled Glass Substitution on the Physical and Mechanical Properties of Clay Bricks. Waste Management 2009, 29, 2717–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epure, C.; Munteanu, C.; Istrate, B.; Harja, M.; Lupu, F.C.; Luca, D. Innovation in the Use of Recycled and Heat-Treated Glass in Various Applications: Mechanical and Chemical Properties. Coatings 2025, 15, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristogianni, T.; Oikonomopoulou, F. Glass Up-Casting: A Review on the Current Challenges in Glass Recycling and a Novel Approach for Recycling “as-Is” Glass Waste into Volumetric Glass Components. Glass Struct Eng 2023, 8, 255–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meziani, S.; Hammouti, A.; Bodiou, L.; Lorrain, N.; Chahal, R.; Bénardais, A.; Courson, R.; Troles, J.; Boussard-Plédel, C.; Nazabal, V.; et al. Mid-Infrared Integrated Spectroscopic Sensor Based on Chalcogenide Glasses: Optical Characterization and Sensing Applications. Advanced Sensor and Energy Materials 2025, 4, 100149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-N.; Lee, J.; Huh, J.-S.; Kim, H. Thermal and Electrical Properties of BaO–B2O3–ZnO Glasses. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 2002, 306, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeder*, T. Review of Bi2 O3 Based Glasses for Electronics and Related Applications. International Materials Reviews 2013, 58, 3–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsay, C.; Zha, Y.; Arnold, C.B. Solution-Processed Chalcogenide Glass for Integrated Single-Mode Mid-Infrared Waveguides. Opt. Express 2010, 18, 26744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, C.; Li, S.; Sun, Y.; Ma, Q.; Wang, R.; Wang, H.; Wang, G.; Ma, S. Study on Structure and Performance of Bi–B–Zn Sealing Glass Encapsulated Fiber Bragg Grating. Ceramics International 2023, 49, 14432–14444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, P.P.; Kumar, N.; Kumari, M.; Kumar, S.; Mondal, P.K.; Arun, R.K. Integrated Microfluidic Devices for Point-of-Care Detection of Bio-Analytes and Disease. Sens. Diagn. 2023, 2, 1437–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staff, M.T.; Fernie, J.A.; Mallinson, P.M.; Whiting, M.J.; Yeomans, J.A. Fabrication of a Glass-Ceramic-to-Metal Seal Between Ti–6Al–4V and a Strontium Boroaluminate Glass. Int J Applied Ceramic Tech 2016, 13, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaji, I. A.; Abbas, Z.; Zaid, M. H. M. Solid State Science and Technology. Dielectric Characterisation of Borosilicate Glass for Microwave Substrate Application 2024, 32, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corning HPFS® Fused Silica — Technical Data Sheet; Corning Inc.: Corning, NY, USA, 2023.

- Suprasil® Fused Silica — Technical Data Sheet; Heraeus Quartz Glass GmbH & Co. KG: Hanau, Germany; Heraeus Quartz Glass GmbH & Co. KG, 2023.

- Shelby, J.E. Introduction to Glass Science and Technology; Royal society of chemistry, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guadagnino, E.; Guglielmi, M.; Nicoletti, F. Glass: The Best Material for Pharmaceutical Packaging. Int J of Appl Glass Sci 2022, 13, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sant’Ana Gallo, L.; Célarié, F.; Bettini, J.; Rodrigues, A.C.M.; Rouxel, T.; Zanotto, E.D. Fracture Toughness and Hardness of Transparent MgO–Al2O3–SiO2 Glass-Ceramics. Ceramics International 2022, 48, 9906–9917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristogianni, T.; Oikonomopoulou, F.; Veer, F.A. On the Flexural Strength and Stiffness of Cast Glass. Glass Struct Eng 2021, 6, 147–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colangelo, S. Reducing the Environmental Footprint of Glass Manufacturing. Int J of Appl Glass Sci 2024, 15, 350–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCHOTT AG Schott AG. BOROFLOAT® 33 — Technical Information Sheet. Available online: https://media.schott.com/api/public/content/cda43a92330145c9b34db0373098ec32?v=87d55030%26download=true (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Sara Ahmadi Advances in the Standards & Applied Sciences 2025; 1 (3). From Efficiency to Sustainability: A Review of Low-Emission Glass 2025.

- IFC Strengthening Sustainability in the Glass Industry 2020.

- Furszyfer Del Rio, D.D.; Sovacool, B.K.; Foley, A.M.; Griffiths, S.; Bazilian, M.; Kim, J.; Rooney, D. Decarbonizing the Glass Industry: A Critical and Systematic Review of Developments, Sociotechnical Systems and Policy Options. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 155, 111885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Han, R.; Luo, M. Jiangxi Key Laboratory of Advanced Ceramic Materials Structure and Properties of ZnO–BaO–Bi2O3–B2O3 Glasses for Low Temperature Sealing Applications. Glass Tech.: Eur. J. Glass Sci. Technol. A 2016, 57, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Zhong, Z.; Xu, J.; Dong, W.; Li, H.; Zhou, J.; Peng, X. Preparation and Properties of Bi2O3-B2O3-ZnO Metal Sealing Glass. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 2025, 668, 123801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdi, S.A.F.; Garavaglia, M.; Ghisi, A.; Corigliano, A. An Experimental and Numerical Study on Glass Frit Wafer-to-Wafer Bonding. Micromachines 2023, 14, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Defense. MIL-STD-883 Rev. L: Test Method Standard – Microcircuits; Method 1014 “Seal”; 2024.

- Lv, Y.; Liu, N.; Chen, C.; Cai, Z.; Li, J. Pharmaceutical Packaging Materials and Medication Safety: A Mini-Review. Safety 2025, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Bodhak, S.; Molla, A.R.; Annapurna, K.; Biswas, K. An Insight into the Thermal Processability of Highly Bioactive Borosilicate Glasses through Kinetic Approach. Int J of Appl Glass Sci 2023, 14, 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, W.; Zhang, L.; Yan, X.; Fan, J.; Zeng, H. Tuning the Thermal and Insulation Properties of Bismuth Borate Glass for SiC Power Electronics Packaging. J Am Ceram Soc. 2024, 107, 2207–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Zhou, D.D. Technology Advances and Challenges in Hermetic Packaging for Implantable Medical Devices. In Implantable Neural Prostheses 2;Biological and Medical Physics, Biomedical Engineering; Zhou, D., Greenbaum, E., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2009; pp. 27–61. ISBN 978-0-387-98119-2. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, T.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Gao, L.; Gan, G.; Qu, S.; Wu, C.; Harris, V.G. Effect of Al2O3 on Structural Dynamics and Dielectric Properties of Lithium Metasilicate Photoetchable Glasses as an Interposer Technology for Microwave Integrated Circuits. Ceramics International 2020, 46, 18032–18036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, D.; Dvivedi, A.; Kumar, P. Optimizing the Quality Characteristics of Glass Composite Vias for RF-MEMS Using Central Composite Design, Metaheuristics, and Bayesian Regularization-Based Machine Learning. Measurement 2025, 243, 116323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Regulation (EC) No 1935/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Materials and Articles Intended to Come into Contact with Food; 2004.

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 4802-1/2; 2018—Glassware—Hydrolytic Resistance Tests. 2018.

- European Committee for Standardization EN 1183:1997; Packaging—Glass Containers—Determination of Hydrolytic Resistance. 1997.

- Chapter 3.2.1 Glass Containers for Pharmaceutical Use. In European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines European Pharmacopoeia, 11th Ed. ed; EDQM, 2023.

- Sharifi, F.; Maglalang, E.; Lee, A.; He, J.; Moshashaee, S. A Toolbox for Early Detection of Glass Delamination in Vials. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2025, 671, 125236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Commission Regulation (EU) 2022/1616 on Recycled Plastic Materials and Articles Intended to Come into Contact with Food; 2022.

- European Committee for Standardization CEN. EN 13430:2004—Packaging—Requirements for Packaging Recoverable by Material Recycling; EN 13430:2004. 2004.

- International Organization for Standardization; ISO. ISO 14067:2018—Greenhouse Gases—Carbon Footprint of Products—Requirements and Guidelines. 2018.

- European Committee for Standardization CEN. EN 13432:2000—Requirements for Packaging Recoverable through Composting and Biodegradation. 2025.

- European Commission. Proposal for a Regulation on Packaging and Packaging Waste (PPWR); COM(2022) 677 Final, Consolidated Version 2025. 2025.

- International Organization for Standardization; ISO. ISO 14040:2006—Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. 2006.

- European Commission Best Available Techniques (BAT) Reference Document for the Manufacture of Glass (BREF). 2022.

- European Commission Sustainable Products Initiative: Digital Product Passport and Product Sustainability Framework (SPI). 2024.

- Bassam, S.A.; Naseer, K.A.; Mahmoud, K.A.; Sangeeth, C.S.S.; Sayyed, M.I.; El-Rehim, A.F.A.; Khandaker, M.U. Influence of Transition Metals on the Radiation Shielding Capability of Eu3+ Ions Doped Telluro Borophosphate Glasses. Nuclear Engineering and Technology 2025, 57, 103229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 22095:2020; Chain of Custody—General Terminology and Models. 2020.

- Wall; Petavratzi, D.E. Life Cycle Assessment of Electronics Supply Chains 2025.

- Andersen, O.; Hille, J.; Gilpin, G.; Andrae, A.S.G. Life Cycle Assessment of Electronics. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Technologies for Sustainability (SusTech), Portland, OR, USA, July 2014; IEEE; pp. 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Bainbridge, A.; Harwell, J.; Zhang, S.; Wagih, M.; Kettle, J. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Circular Consumer Electronics Based on IC Recycling and Emerging PCB Assembly Materials. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 29183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Kiehbadroudinezhad, M.; Hosseinzadeh-Bandbafha, H.; Gupta, V.K.; Peng, W.; Lam, S.S.; Tabatabaei, M.; Aghbashlo, M. Driving Sustainable Circular Economy in Electronics: A Comprehensive Review on Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of e-Waste Recycling. Environmental Pollution 2024, 342, 123081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popowicz, M.; Katzer, N.J.; Kettele, M.; Schöggl, J.-P.; Baumgartner, R.J. Digital Technologies for Life Cycle Assessment: A Review and Integrated Combination Framework. Int J Life Cycle Assess 2025, 30, 405–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Regulation /Standard |

Key Requirement | Industrial Implication | Current Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

|

PPWR 2025 [131] |

≥ 80% glass recycling by 2030; promotion of reuse and DRS schemes | Need for harmonised collection, colour sorting, high-purity cullet streams | Strong regional variability in collection rates; inconsistent cullet quality |

| SPI 2024 / Digital Product Passport [134] | Batch-level traceability of cullet origin, composition, and energy source | Integration of AI monitoring, data-sharing platforms, ISO 22095 compliance | Limited industrial deployment; lack of unified traceability infrastructure |

|

BREF 2022 (BAT) [133] |

Low-NOₓ and energy-efficient melting | Hybrid/oxy-fuel furnaces, improved insulation, heat recovery | Electrical grid capacity, refractory constraints, high investment thresholds |

|

ISO 14040/44 and ISO 14067 [129,132] |

Transparent LCA and carbon-footprint reporting | Standardised CO2 accounting; certification of low-carbon batches | Lack of harmonised datasets for certain compositions; no LCA data for functional glasses |

| EC 1935/2004; EN 1183; ISO 4802; USP <660> [68,122,123] | Migration limits and hydrolytic resistance for food/pharma use | Material validation, compositional control, surface-quality assurance | Not applicable to functional/electronic glasses; no parallel standards |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).