Submitted:

22 December 2025

Posted:

23 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

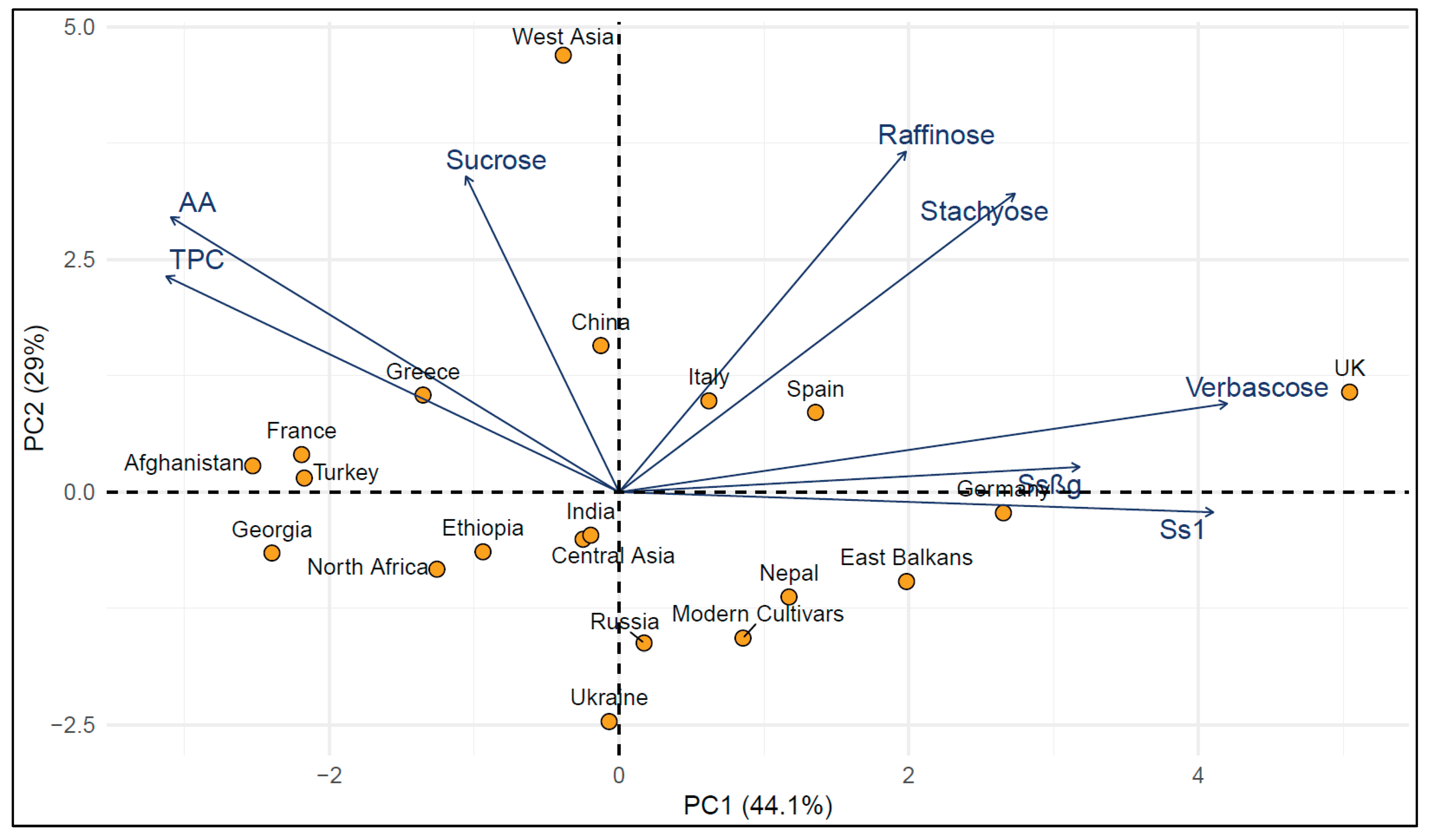

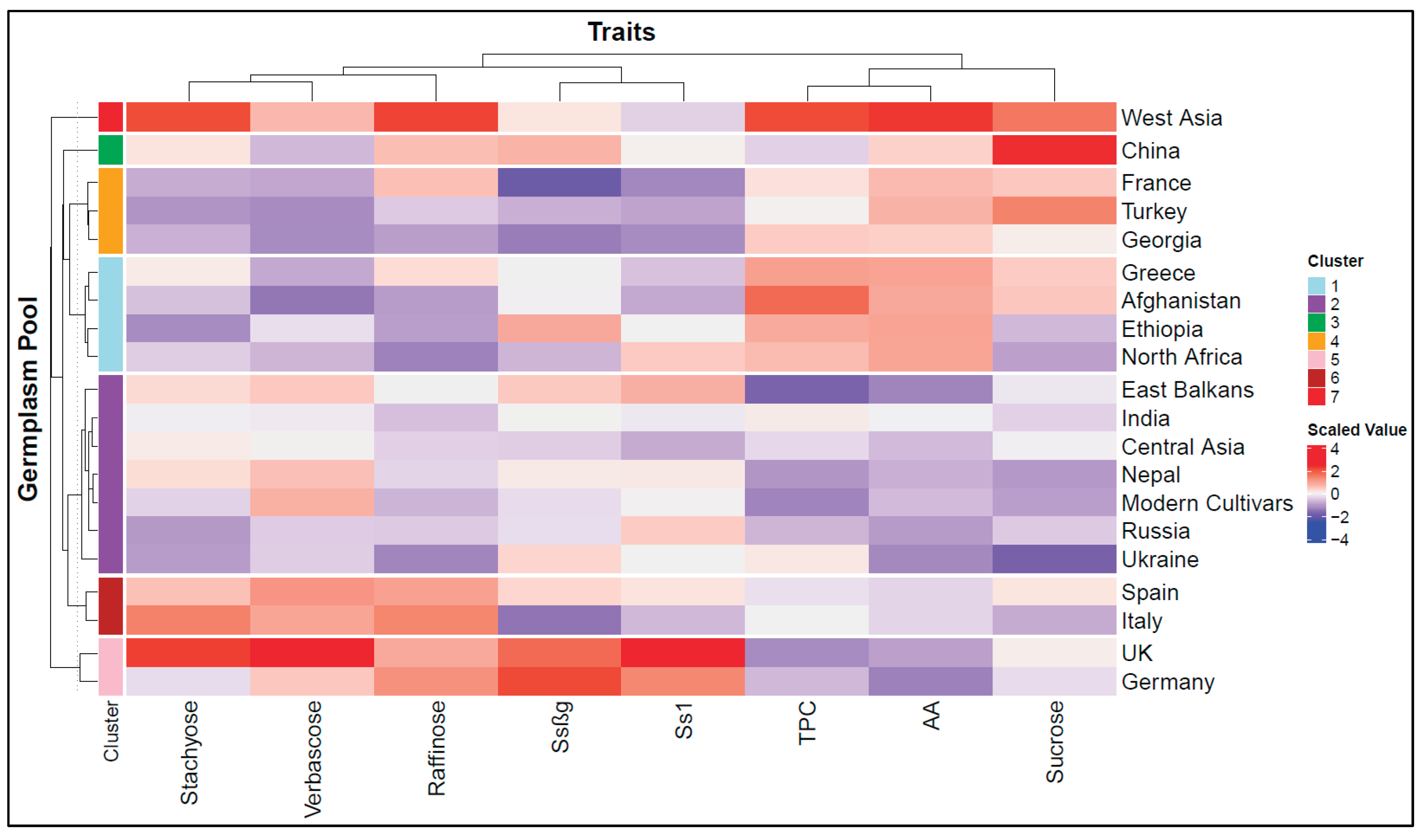

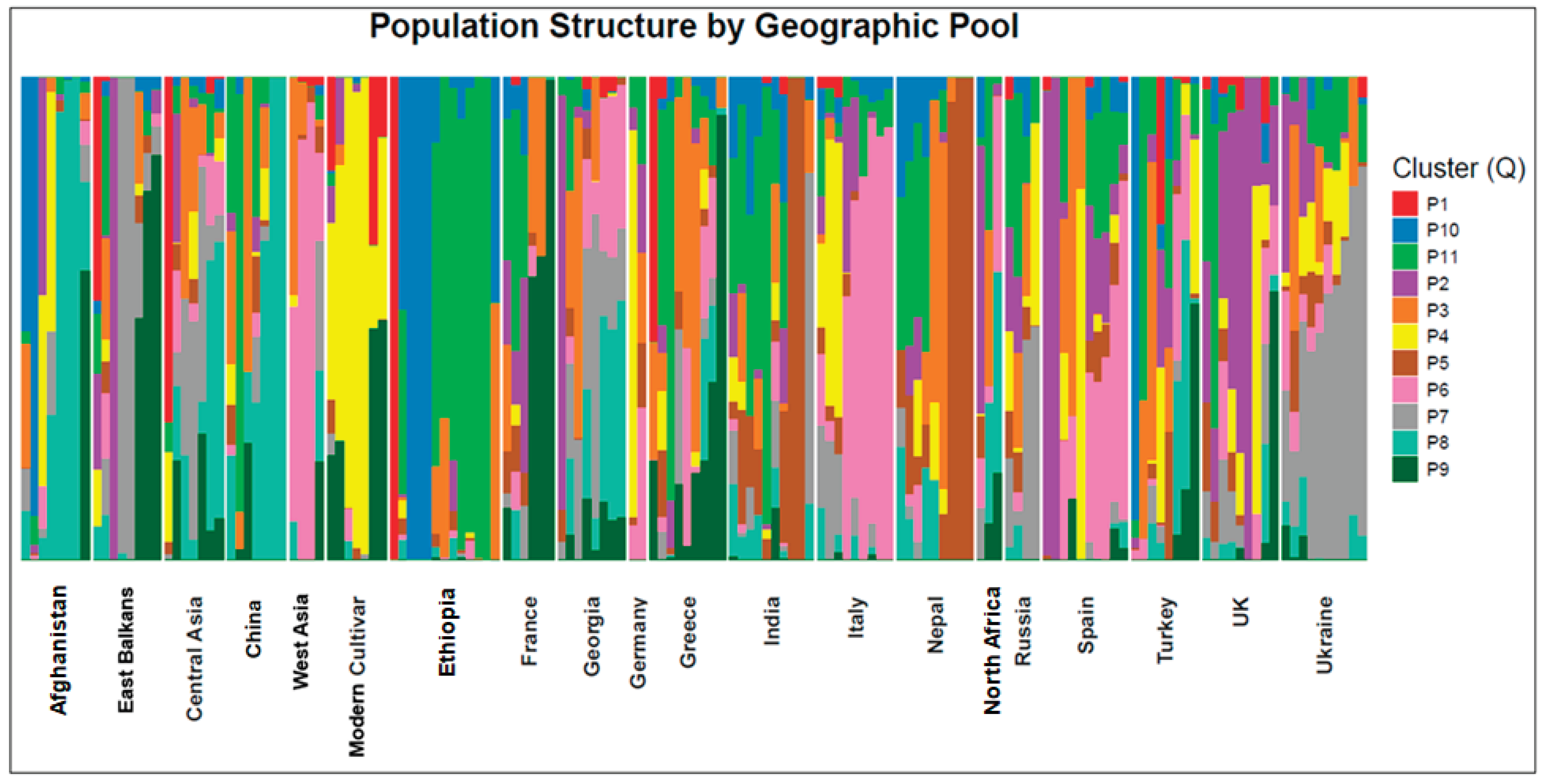

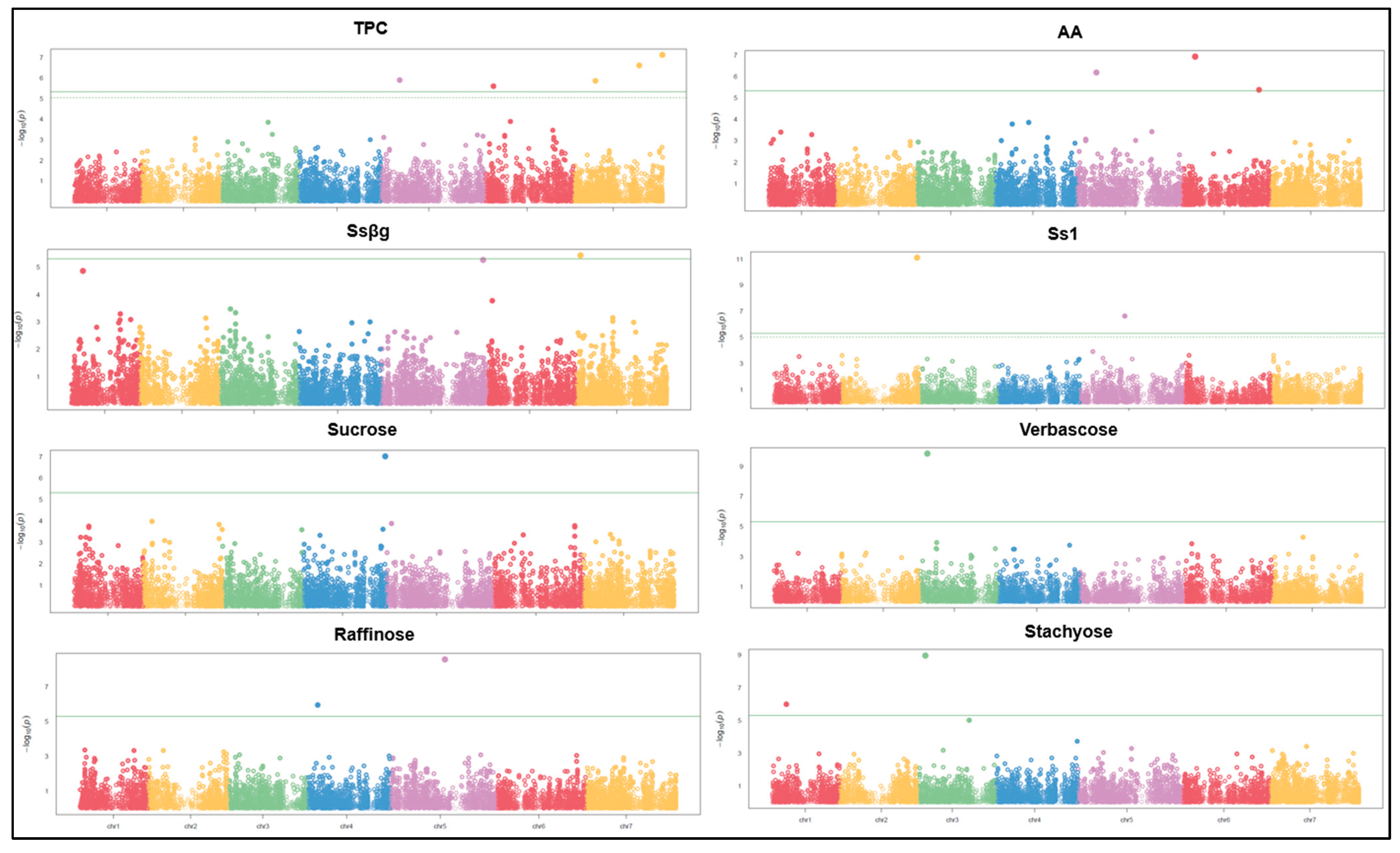

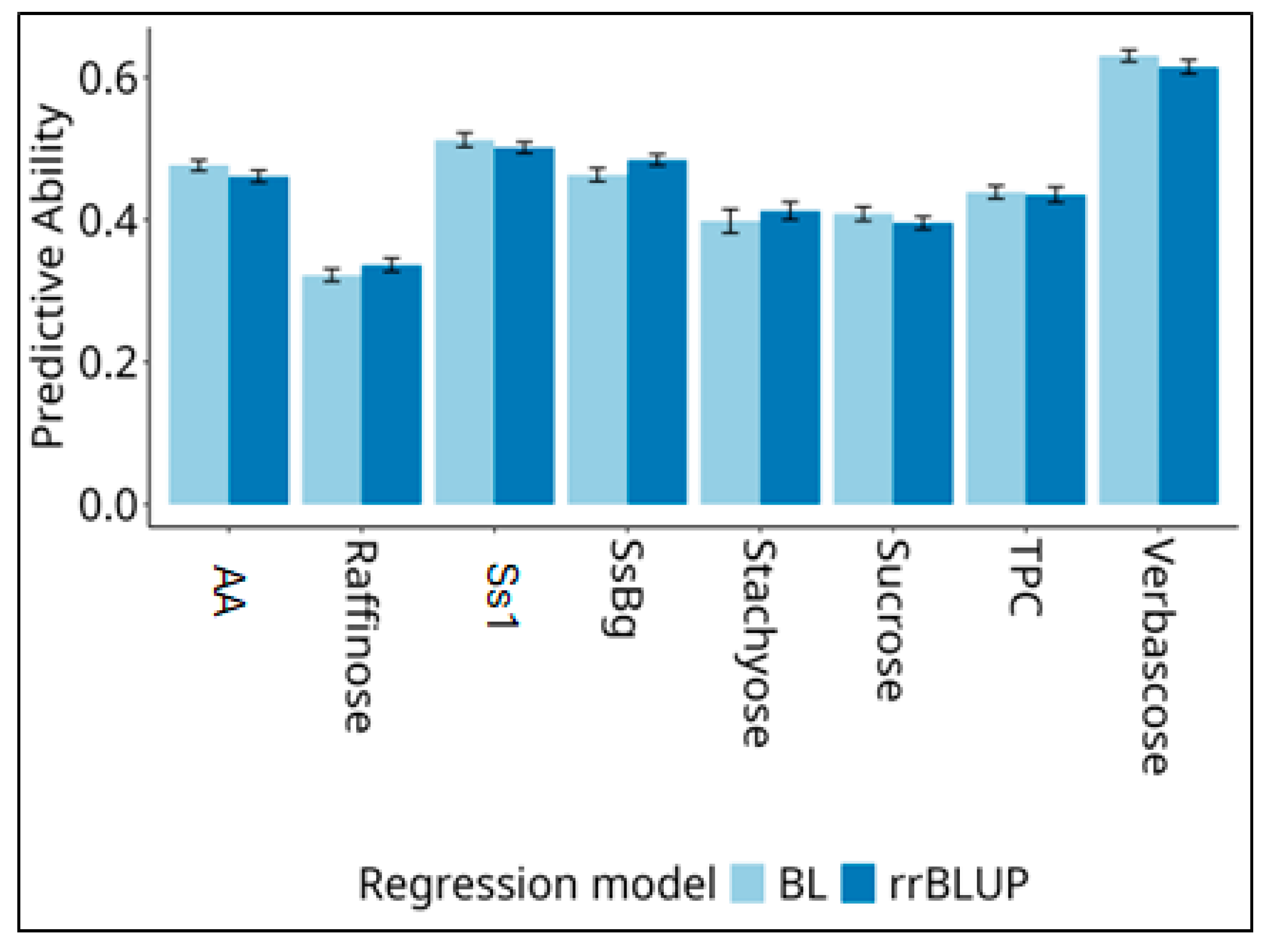

This study aimed to characterize the variation and genetic architecture of traits with nutritional and health relevance in 156 pea (Pisum sativum L.) accessions representing diverse geographic origins. The traits included total phenolic compounds (TPC), two saponins (Ssβg, Ss1), sucrose, three raffinose-family oligosaccharides (RFOs) and in vitro antioxidant activity (AA). Analysis of variance revealed significant effects of regional germplasm pools for all traits. Accessions from West Asia showed the highest TPC and AA levels, while those from the East Balkans and the UK displayed the lowest values. High saponin and RFO concentrations characterized accessions from Germany and the UK. Correlation and PCA analyses highlighted strong associations within compound classes and an overall negative relationship between TPC/AA and saponins/RFOs. Hierarchical clustering separated accessions into seven metabolically distinct groups partially reflecting their geographic origin. Linkage disequilibrium decayed rapidly (average 4.7 kb). GWAS with FarmCPU and BLINK identified 37 significant SNPs, 35 within annotated genes, associated with the metabolites. The polygenic genetic architecture supported the development of genomic prediction models, which showed moderately high predictive ability (> 0.40) for all traits except raffinose content. Our findings can support line selection and the identification of genetic resources with a desired level of secondary metabolites.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Phenotypic Trait Variation

2.2. Analysis of Population Structure

2.3. Linkage Disequilibrium Decay and Genome-Wide Association Study

2.4. Genome-Enabled Prediction

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

4.2. Chemical Analyses

4.2.1. Total Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity

4.2.2. Saponins

4.2.3. HPLC Quantification of Sucrose and RFO for FT-IR Calibration

4.2.4. FT-IR-Based Modeling for Sucrose and RFO

4.3. Statistical Analyses

4.4. GBS, SNP Calling, Marker Filtering and Imputation

4.5. Linkage Disequilibrium, Population Genetic Structure and Genome Wide Association Study (GWAS)

4.6. Genomic Prediction

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | Antioxidant activity | ||

| ACN | Acetonitrile | ||

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance | ||

| BLUP | Best linear unbiased prediction | ||

| rrBLUP | Ridge regression best linear unbiased prediction | ||

| DPPH | 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical | ||

| FA | Formic acid | ||

| FT-IR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy | ||

| FWHM | Full width at half maximum | ||

| GAE | Gallic acid equivalents. | ||

| GBS | Genotyping-by-sequencing | ||

| (U) HPLC | (Ultra) High Performance Liquid Chromatography | ||

| ISTD | Internal standard | ||

| ITT | Ion transfer tube | ||

| LD | Linkage disequilibrium | ||

| MeOH | Methanol | ||

| MS | Mass spectrometry | ||

| MS2 | Tandem mass spectrometry (fragmentation) | ||

| NaOH | Sodium hydroxyde | ||

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene fluoride | ||

| QC | Quality control | ||

| RC | Regenerated cellulose | ||

| SNP | Single-nucleotide polymorphism | ||

| Ssβg | Soyasaponin βg | ||

| Ss1 | Soyasaponin I | ||

| TE | 6-Hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid (Trolox) Equivalents | ||

| TPC | Total Phenolic content | ||

| AA | Antioxidant activity | ||

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance | ||

| BLUP | Best linear unbiased prediction | ||

| rrBLUP | Ridge regression best linear unbiased prediction | ||

| DPPH | 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical | ||

| FT-IR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy | ||

| GAE | Gallic acid equivalents. | ||

| GBS | Genotyping-by-sequencing | ||

| HPLC | High Performance Liquid Chromatography | ||

| LD | Linkage disequilibrium | ||

| SNP | Single-nucleotide polymorphism | ||

| Ssβg | Soyasaponin βg | ||

| Ss1 | Soyasaponin I | ||

| TE | 6-Hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid (Trolox) equivalents | ||

| TPC | Total Phenolic compounds | ||

References

- Carrouée, B.; Crépon, K.; Peyronnet, C. Les protéagineux : intérêt dans les systèmes de production fourragers français et européens. 2003.

- Annicchiarico, P. Adaptation of Cool-Season Grain Legume Species across Climatically-Contrasting Environments of Southern Europe. Agron. J. 2008, 100, 1647–1654. [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.B.; Tar’an, B.; Diapari, M.; Warkentin, T.D. SNP Variation within Genes Associated with Amylose, Total Starch and Crude Protein Concentration in Field Pea. Euphytica 2015, 206, 459–471. [CrossRef]

- Annicchiarico, P.; Nazzicari, N.; Wei, Y.; Pecetti, L.; Brummer, E.C. Genotyping-by-Sequencing and Its Exploitation for Forage and Cool-Season Grain Legume Breeding. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8.

- Stagnari, F.; Maggio, A.; Galieni, A.; Pisante, M. Multiple Benefits of Legumes for Agriculture Sustainability: An Overview. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2017, 4, 2. [CrossRef]

- van Loon, M.P.; Alimagham, S.; Pronk, A.; Fodor, N.; Ion, V.; Kryvoshein, O.; Kryvobok, O.; Marrou, H.; Mihail, R.; Mínguez, M.I.; et al. Grain Legume Production in Europe for Food, Feed and Meat-Substitution. Glob. Food Secur. 2023, 39, 100723. [CrossRef]

- Visser, C.L.M. de; Schreuder, R.; Stoddard, F. The EU’s Dependency on Soya Bean Import for the Animal Feed Industry and Potential for EU Produced Alternatives. OCL 2014, 21, D407. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; Gupta, E.; Yadav, S.; Babulal, K.S.; Mishra, S. Plant-Based Food Industry: Overview and Trends. In The Future of Plant Protein: Innovations, Challenges, and Opportunities; Younis, K., Yousuf, O., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 73–97 ISBN 978-981-96-4190-1.

- Venter de Villiers, M.; Cheng, J.; Truter, L. The Shift Towards Plant-Based Lifestyles: Factors Driving Young Consumers’ Decisions to Choose Plant-Based Food Products. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9022. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Bharali, P. The Rise of Plant-Based Meat Alternatives: Challenges and Perspectives. Food Biosci. 2025, 68, 106640. [CrossRef]

- Smýkal, P.; Kenicer, G.; Flavell, A.J.; Corander, J.; Kosterin, O.; Redden, R.J.; Ford, R.; Coyne, C.J.; Maxted, N.; Ambrose, M.J.; et al. Phylogeny, Phylogeography and Genetic Diversity of the Pisum Genus. Plant Genet. Resour. 2011, 9, 4–18. [CrossRef]

- Vaz Patto, M.C.; Amarowicz ,Ryszard; Aryee ,Alberta N. A.; Boye ,Joyce I.; Chung ,Hyun-Jung; Martín-Cabrejas ,Maria A.; and Domoney, C. Achievements and Challenges in Improving the Nutritional Quality of Food Legumes. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2015, 34, 105–143. [CrossRef]

- Lara, S.W.; Ryan, P. The Current State of Peas in the United Kingdom; Diversity, Heritage and Food Systems. PLANTS PEOPLE PLANET 2025, 7, 1235–1244. [CrossRef]

- Annicchiarico, P.; Romani, M.; Cabassi, G.; Ferrari, B. Diversity in a Pea (Pisum Sativum) World Collection for Key Agronomic Traits in a Rain-Fed Environment of Southern Europe. Euphytica 2017, 213, 245. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Holdsworth, W.; Ma, Y.; Coyne, C.J.; Mazourek, M.; Grusak, M.A.; Fuchs, S.; McGee, R.J. Association Mapping of Agronomic and Quality Traits in USDA Pea Single-Plant Collection. Mol. Breed. 2015, 35, 75. [CrossRef]

- Elango, D.; Rajendran, K.; Van der Laan, L.; Sebastiar, S.; Raigne, J.; Thaiparambil, N.A.; El Haddad, N.; Raja, B.; Wang, W.; Ferela, A.; et al. Raffinose Family Oligosaccharides: Friend or Foe for Human and Plant Health? Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Price, K.R.; Johnson, I.T.; Fenwick, G.R.; Malinow, M.R. The Chemistry and Biological Significance of Saponins in Foods and Feedingstuffs. C R C Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1987, 26, 27–135. [CrossRef]

- Bljahhina, A.; Pismennõi, D.; Kriščiunaite, T.; Kuhtinskaja, M.; Kobrin, E.-G. Quantitative Analysis of Oat (Avena Sativa L.) and Pea (Pisum Sativum L.) Saponins in Plant-Based Food Products by Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography Coupled with Mass Spectrometry. Foods 2023, 12, 991. [CrossRef]

- Heng, L.; Vincken, J.-P.; van Koningsveld, G.; Legger, A.; Gruppen, H.; van Boekel, T.; Roozen, J.; Voragen, F. Bitterness of Saponins and Their Content in Dry Peas. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2006, 86, 1225–1231. [CrossRef]

- Reim, V.; Rohn, S. Characterization of Saponins in Peas (Pisum Sativum L.) by HPTLC Coupled to Mass Spectrometry and a Hemolysis Assay. Food Res. Int. 2015, 76, 3–10. [CrossRef]

- Tanambell, H.; Bramsen, M.R.; Danielsen, M.; Nebel, C.; Møller, A.H.; Dalsgaard, T.K. Saponin and Hexanal in Pea (Pisum Sativum) Protein Isolates: A Comparative Study of Isoelectric Precipitation and Ultrafiltration. LWT 2025, 223, 117772. [CrossRef]

- Wink, M. Evolution of Secondary Metabolites in Legumes (Fabaceae). South Afr. J. Bot. 2013, 89, 164–175. [CrossRef]

- Oliete, B.; Lubbers, S.; Fournier, C.; Jeandroz, S.; Saurel, R. Effect of Biotic Stress on the Presence of Secondary Metabolites in Field Pea Grains. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, 102, 4942–4948. [CrossRef]

- Morita, M.; Shibuya, M.; Kushiro, T.; Masuda, K.; Ebizuka, Y. Molecular Cloning and Functional Expression of Triterpene Synthases from Pea (Pisum Sativum). Eur. J. Biochem. 2000, 267, 3453–3460. [CrossRef]

- Vernoud, V.; Lebeigle, L.; Munier, J.; Marais, J.; Sanchez, M.; Pertuit, D.; Rossin, N.; Darchy, B.; Aubert, G.; Le Signor, C.; et al. β-Amyrin Synthase1 Controls the Accumulation of the Major Saponins Present in Pea (Pisum Sativum). Plant Cell Physiol. 2021, 62, 784–797. [CrossRef]

- Hodgins, C.L.; Salama, E.M.; Kumar, R.; Zhao, Y.; Roth, S.A.; Cheung, I.Z.; Chen, J.; Arganosa, G.C.; Warkentin, T.D.; Bhowmik, P.; et al. Creating Saponin-Free Yellow Pea Seeds by CRISPR/Cas9-Enabled Mutagenesis on β-Amyrin Synthase. Plant Direct 2024, 8, e563. [CrossRef]

- Gawłowska, M.; Święcicki, W.; Lahuta, L.; Kaczmarek, Z. Raffinose Family Oligosaccharides in Seeds of Pisum Wild Taxa, Type Lines for Seed Genes, Domesticated and Advanced Breeding Materials. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2017, 64, 569–578. [CrossRef]

- Peterbauer, T.; Lahuta, L.B.; Blöchl, A.; Mucha, J.; Jones, D.A.; Hedley, C.L.; Gòrecki, R.J.; Richter, A. Analysis of the Raffinose Family Oligosaccharide Pathway in Pea Seeds with Contrasting Carbohydrate Composition. Plant Physiol. 2001, 127, 1764–1772. [CrossRef]

- Role of Phenols and Polyphenols in Plant Defense Response to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. In Biocontrol Agents and Secondary Metabolites; Woodhead Publishing, 2021; pp. 419–441.

- Elessawy, F.M.; Vandenberg, A.; El-Aneed, A.; Purves, R.W. An Untargeted Metabolomics Approach for Correlating Pulse Crop Seed Coat Polyphenol Profiles with Antioxidant Capacity and Iron Chelation Ability. Molecules 2021, 26, 3833. [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Pan, Q.-H.; Shi, Y.; Duan, C.-Q. Biosynthesis and Genetic Regulation of Proanthocyanidins in Plants. Molecules 2008, 13, 2674–2703. [CrossRef]

- Elessawy, F.M.; Bazghaleh, N.; Vandenberg, A.; Purves, R.W. Polyphenol Profile Comparisons of Seed Coats of Five Pulse Crops Using a Semi-Quantitative Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometric Method. Phytochem. Anal. 2020, 31, 458–471. [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.B.; Purves, R.W.; Elessawy, F.M.; Zhang, H.; Vandenberg, A.; Warkentin, T.D. Polyphenolic Profile of Seed Components of White and Purple Flower Pea Lines. Crop Sci. 2019, 59, 2711–2719. [CrossRef]

- Hellens, R.P.; Moreau, C.; Lin-Wang, K.; Schwinn, K.E.; Thomson, S.J.; Fiers, M.W.E.J.; Frew, T.J.; Murray, S.R.; Hofer, J.M.I.; Jacobs, J.M.E.; et al. Identification of Mendel’s White Flower Character. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e13230. [CrossRef]

- Krajewski, P.; Bocianowski, J.; Gawłowska, M.; Kaczmarek, Z.; Pniewski, T.; Święcicki, W.; Wolko, B. QTL for Yield Components and Protein Content: A Multienvironment Study of Two Pea (Pisum Sativum L.) Populations. Euphytica 2012, 183, 323–336. [CrossRef]

- Gali, K.K.; Liu, Y.; Sindhu, A.; Diapari, M.; Shunmugam, A.S.K.; Arganosa, G.; Daba, K.; Caron, C.; Lachagari, R.V.B.; Tar’an, B.; et al. Construction of High-Density Linkage Maps for Mapping Quantitative Trait Loci for Multiple Traits in Field Pea (Pisum Sativum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 172. [CrossRef]

- Gali, K.K.; Sackville, A.; Tafesse, E.G.; Lachagari, V.B.R.; McPhee, K.; Hybl, M.; Mikić, A.; Smýkal, P.; McGee, R.; Burstin, J.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Mapping for Agronomic and Seed Quality Traits of Field Pea (Pisum Sativum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Crosta, M.; Nazzicari, N.; Ferrari, B.; Pecetti, L.; Russi, L.; Romani, M.; Cabassi, G.; Cavalli, D.; Marocco, A.; Annicchiarico, P. Pea Grain Protein Content Across Italian Environments: Genetic Relationship With Grain Yield, and Opportunities for Genome-Enabled Selection for Protein Yield. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12.

- Crosta, M.; Romani, M.; Nazzicari, N.; Ferrari, B.; Annicchiarico, P. Genomic Prediction and Allele Mining of Agronomic and Morphological Traits in Pea (Pisum Sativum) Germplasm Collections. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1320506. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Gali, K.K.; Jha, A.B.; Tar’an, B.; Warkentin, T.D. Identification of Quantitative Trait Loci Associated with Seed Protein Concentration in a Pea Recombinant Inbred Line Population. Genes 2022, 13, 1531. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wan, Z.; Gali, K.K.; Jha, A.B.; Nickerson, M.T.; House, J.D.; Tar’an, B.; Warkentin, T.D. Quantitative Trait Loci Associated with Amino Acid Concentration and in Vitro Protein Digestibility in Pea (Pisum Sativum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Meuwissen, T.H.E.; Hayes, B.J.; Goddard, M.E. Prediction of Total Genetic Value Using Genome-Wide Dense Marker Maps. Genetics 2001, 157, 1819–1829. [CrossRef]

- Crosta, M.; Nazzicari, N.; Pecetti, L.; Notario, T.; Romani, M.; Ferrari, B.; Cabassi, G.; Annicchiarico, P. Genomic Selection for Pea Grain Yield and Protein Content in Italian Environments for Target and Non-Target Genetic Bases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2991. [CrossRef]

- Heffner, E.L.; Sorrells, M.E.; Jannink, J.-L. Genomic Selection for Crop Improvement. Crop Sci. 2009, 49, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Akhov, L.; Ashe, P.; Lewis, C.; Deibert, L.; Irina Zaharia, L.; Forseille, L.; Xiang, D.; Datla, R.; Nosworthy, M.; et al. Comprehensive Compositional Assessment of Bioactive Compounds in Diverse Pea Accessions. Food Res. Int. 2023, 165, 112455. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-K.; Lin, H.-F.; Wang, X.; Yuan, Y.; Yin, J.-Y.; Song, X.-X. Comprehensive Analysis in the Nutritional Composition, Phenolic Species and in Vitro Antioxidant Activities of Different Pea Cultivars. Food Chem. X 2023, 17, 100599. [CrossRef]

- Vurro, F.; De Angelis, D.; Squeo, G.; Pavan, S.; Pasqualone, A.; Summo, C. Data on the Nutritional and Fatty Acid Composition, Bioactive Compounds, in Vitro Antioxidant Activity and Techno-Functional Properties of a Collection of Pea (Pisum Sativum L.). Data Brief 2025, 61, 111709. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Gao, J.; Wei, Z.; Shahidi, F. Effect of in Vitro Digestion on Phenolics and Antioxidant Activity of Red and Yellow Colored Pea Hulls. Food Chem. 2021, 337, 127606. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.; Basu, S.; Goswami, D.; Devi, M.; Shivhare, U.S.; Vishwakarma, R.K. Anti-Nutritional Compounds in Pulses: Implications and Alleviation Methods. Legume Sci. 2022, 4, e111. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Qi, Y.; Zheng, H. Dietary Polyphenol, Gut Microbiota, and Health Benefits. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1212. [CrossRef]

- Zeb, A. Concept, Mechanism, and Applications of Phenolic Antioxidants in Foods. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13394. [CrossRef]

- Rashmi, H.B.; Negi, P.S. Phytochemical Constituents and Anthelmintic Potential of Surinam Cherry (Eugenia Uniflora L.) at Different Fruit Developmental Stages. South Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 145, 512–521. [CrossRef]

- Pasqualone, A.; Delvecchio, L.N.; Mangini, G.; Taranto, F.; Blanco, A. Variability of Total Soluble Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in a Collection of Tetraploid Wheat. Agric. Food Sci. 2014, 23, 307–316. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.; Purves, R.W.; Paliocha, M.; Uhlen, A.K.; Zanotto, S. Multi-Environment Field Trials Indicate Strong Genetic Control of Seed Polyphenol Accumulation in Faba Bean. Euphytica 2025, 221, 47. [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Valverde, C.; Frias, J.; Hernández, A.; Martín-Alvarez, P.J.; Sierra, I.; Rodríguez, C.; Blazquez, I.; Vicente, G. Assessment of Nutritional Compounds and Antinutritional Factors in Pea (Pisum Sativum) Seeds. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2003, 83, 298–306. [CrossRef]

- Baud, S.; Guyon, V.; Kronenberger, J.; Wuillème, S.; Miquel, M.; Caboche, M.; Lepiniec, L.; Rochat, C. Multifunctional Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase 1 Is Essential for Very Long Chain Fatty Acid Elongation and Embryo Development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2003, 33, 75–86. [CrossRef]

- Molendijk, A.J.; Ruperti, B.; Singh, M.K.; Dovzhenko, A.; Ditengou, F.A.; Milia, M.; Westphal, L.; Rosahl, S.; Soellick, T.-R.; Uhrig, J.; et al. A Cysteine-Rich Receptor-like Kinase NCRK and a Pathogen-Induced Protein Kinase RBK1 Are Rop GTPase Interactors. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2008, 53, 909–923. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Feng, J.; Wang, R.; Liu, H.; Yang, H.; Rodriguez, P.L.; Qin, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, D. HRS1 Acts as a Negative Regulator of Abscisic Acid Signaling to Promote Timely Germination of Arabidopsis Seeds. PloS One 2012, 7, e35764. [CrossRef]

- Gangl, R.; Tenhaken, R. Raffinose Family Oligosaccharides Act As Galactose Stores in Seeds and Are Required for Rapid Germination of Arabidopsis in the Dark. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; Liu, Y.; Dirk, L.M.A.; Goodman, J.; Downie, A.B.; Wang, J.; Wang, G.; Zhao, T. Regulation of Seed Vigor by Manipulation of Raffinose Family Oligosaccharides in Maize and Arabidopsis Thaliana. Mol. Plant 2017, 10, 1540–1555. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Xu, C. Genomic Selection Methods for Crop Improvement: Current Status and Prospects. Crop J. 2018, 6, 330–340. [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.; Houtin, H.; Rond-Coissieux, C.; Naudet-Huart, M.; Touratier, M.; Marget, P.; Burstin, J. Meta-Analysis of QTL Reveals the Genetic Control of Yield-Related Traits and Seed Protein Content in Pea. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15925. [CrossRef]

- Franguelli, N.; Cavalli, D.; Nazzicari, N.; Pecetti, L.; Notario, T.; Annicchiarico, P. Genetic Variation and Genome-Enabled Prediction of White Lupin Frost Resistance in Different Reference Populations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10224. [CrossRef]

- Osuna-Caballero, S.; Rubiales, D.; Annicchiarico, P.; Nazzicari, N.; Rispail, N. Genomic Prediction for Rust Resistance in Pea. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Vurro, F.; Anelli, P.; Zocchi, D.M.; De Bellis, P.; Pieroni, A.; Pasqualone, A. Bessarabian Wild Hop Sourdough: Microbial Characterization and Effect on the Physicochemical Properties and Flavor of the Bread. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2025, 42, 101377. [CrossRef]

- Marcotuli, I.; Vurro, F.; Mores, A.; Pasqualone, A.; Colasuonno, P.; Cabas-Lühmann, P.; Schwember, A.R.; Gadaleta, A. Genetic Study of Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity Traits in Tetraploid Wheat via Genome-Wide Association Mapping. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1048. [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Maechler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Lme4: Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using “Eigen” and S4 2003, 1.1-38.

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR : An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25. [CrossRef]

- Maechler, M.; Rousseeuw, P.; Struyf, A.; Hubert, M. Cluster: “Finding Groups in Data”: Cluster Analysis Extended Rousseeuw et Al. 1999, 2.1.8.1.

- Gu, Z.; Hübschmann, D. Make Interactive Complex Heatmaps in R. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 1460–1462. [CrossRef]

- Pavan, S.; Delvento, C.; Nazzicari, N.; Ferrari, B.; D’Agostino, N.; Taranto, F.; Lotti, C.; Ricciardi, L.; Annicchiarico, P. Merging Genotyping-by-Sequencing Data from Two Ex Situ Collections Provides Insights on the Pea Evolutionary History. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhab062. [CrossRef]

- Nazzicari, N.; Franguelli, N.; Ferrari, B.; Pecetti, L.; Annicchiarico, P. The Effect of Genome Parametrization and SNP Marker Subsetting on Genomic Selection in Autotetraploid Alfalfa. Genes 2024, 15, 449. [CrossRef]

- Kreplak, J.; Madoui, M.-A.; Cápal, P.; Novák, P.; Labadie, K.; Aubert, G.; Bayer, P.E.; Gali, K.K.; Syme, R.A.; Main, D.; et al. A Reference Genome for Pea Provides Insight into Legume Genome Evolution. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 1411–1422. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, N.; Pégard, M.; Solis, I.; Sokolovic, D.; Lloyd, D.; Howarth, C.; Torres, A.M. Genome-Wide Association Study for Yield-Related Traits in Faba Bean (Vicia Faba L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Frichot, E.; François, O. LEA: An R Package for Landscape and Ecological Association Studies. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015, 6, 925–929. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Z. GAPIT Version 3: Boosting Power and Accuracy for Genomic Association and Prediction. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 2021, 19, 629–640. [CrossRef]

- Endelman, J.B. Ridge Regression and Other Kernels for Genomic Selection with R Package rrBLUP. Plant Genome 2011, 4. [CrossRef]

- Park, T.; Casella, G. The Bayesian Lasso. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2008, 103, 681–686. [CrossRef]

- Nazzicari, N.; Biscarini, F. Stacked Kinship CNN vs. GBLUP for Genomic Predictions of Additive and Complex Continuous Phenotypes. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19889. [CrossRef]

| Germplasm pool | Total phenolic compounds (mg GAE/g) | Antioxidant activity (µmol TE/g) | Ssβg saponin µg/g | Ss1 saponin µg/g | Sucrose mg/g | Raffinose mg/g | Stachyose mg/g | Verbascose mg/g | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 0.80 (0.55-1.00) | 1.35 (0.43-2.34) | 500.14 (240.39-712.70) | 21.40 (10.86-34.10) | 6.36 (4.44-8.79) | 2.16 (1.49-2.77) | 6.44 (5.34-7.87) | 6.73 (3.72-9.86) | |

| Central Asia | 0.65 (0.52-0.72) | 0.83 (0.53-1.29) | 466.33 (263.76-754.24) | 21.62 (16.17-29.40) | 5.87 (4.32-10.02) | 2.35 (1.77-3.47) | 6.79 (5.93-8.85) | 8.54 (6.24-10.42) | |

| China | 0.65 (0.57-0.74) | 1.17 (0.85-1.37) | 571.29 (382.44-718.51) | 27.13 (14.31-41.41) | 8.08 (4.71-10.49) | 2.66 (2.00-3.34) | 6.84 (5.99-8.91) | 7.70 (4.59-9.78) | |

| East Balkans | 0.54 (0.35-0.72) | 0.62 (0.16-1.13) | 546.45 (307.77-749.58) | 32.29 (13.15-53.82) | 5.80 (4.09-8.85) | 2.47 (1.52-3.61) | 6.89 (4.89-8.97) | 9.13 (6.75-12.57) | |

| Ethiopia | 0.74 (0.48-0.83) | 1.37 (0.85-2.14) | 584.16 (273.64-961.84) | 26.89 (11.16-36.96) | 5.32 (2.38-7.99) | 2.17 (1.60-2.64) | 6.08 (5.02-7.09) | 8.29 (6.10-10.19) | |

| France | 0.69 (0.49-0.84) | 1.27 (0.70-1.60) | 331.71 (212.75-553.76) | 18.71 (10.44-31.08) | 6.35 (3.75-11.71) | 2.66 (1.88-4.22) | 6.31 (5.41-7.88) | 7.45 (5.46-10.59) | |

| Georgia | 0.70 (0.56-0.85) | 1.18 (0.55-1.93) | 381.46 (154.07-624.52) | 19.05 (9.40-30.31) | 5.92 (2.57-8.38) | 2.17 (1.47-2.82) | 6.33 (4.94-7.67) | 7.04 (3.55-9.99) | |

| Germany | 0.62 (0.60-0.65) | 0.60 (0.49-0.71) | 696.49 (690.52-702.45) | 36.11 (34.29-37.93) | 5.70 (4.91-6.49) | 2.85 (2.72-2.99) | 6.62 (6.49-6.76) | 9.15 (8.56-9.73) | |

| Greece | 0.75 (0.53-1.07) | 1.37 (0.86-2.10) | 501.21 (155.63-801.31) | 23.37 (6.56-35.96) | 6.29 (3.79-10.72) | 2.55 (1.77-3.85) | 6.79 (5.94-8.32) | 7.48 (2.79-10.70) | |

| India | 0.68 (0.46-0.83) | 1.03 (0.34-2.14) | 503.40 (290.07-677.81) | 26.30 (12.37-49.00) | 5.59 (4.09-8.76) | 2.29 (1.86-3.01) | 6.72 (5.75-7.43) | 8.42 (6.34-10.69) | |

| Italy | 0.67 (0.57-0.80) | 0.93 (0.69-1.16) | 373.08 (124.09-741.41) | 22.59 (9.59-34.47) | 5.19 (2.94-9.10) | 2.91 (1.87-4.12) | 7.56 (5.87-10.53) | 9.70 (6.18-12.82) | |

| Nepal | 0.59 (0.43-0.90) | 0.79 (0.38-1.83) | 512.76 (340.36-919.02) | 27.65 (19.61-43.62) | 4.98 (4.09-7.66) | 2.37 (1.80-3.23) | 6.88 (5.24-8.06) | 9.26 (8.02-10.12) | |

| North Africa | 0.72 (0.59-0.81) | 1.36 (0.88-1.74) | 440.92 (404.28-476.63) | 29.94 (20.49-42.84) | 5.06 (4.22-5.78) | 2.06 (1.76-2.22) | 6.52 (5.59-7.30) | 7.65 (7.52-7.73) | |

| Russia | 0.62 (0.50-0.70) | 0.71 (0.61-0.87) | 484.80 (370.24-564.36) | 29.78 (23.36-37.18) | 5.51 (4.14-6.13) | 2.33 (2.02-2.55) | 6.18 (5.32-6.92) | 8.00 (6.74-10.60) | |

| Spain | 0.66 (0.48-0.76) | 0.94 (0.42-1.98) | 531.94 (43.86-768.24) | 28.05 (1.97-44.66) | 6.04 (2.48-10.08) | 2.79 (1.85-3.62) | 7.07 (5.34-9.56) | 10.00 (8.57-14.16) | |

| Turkey | 0.67 (0.52-0.83) | 1.30 (0.71-2.03) | 436.67 (101.36-819.71) | 20.99 (6.69-41.93) | 7.20 (4.93-11.27) | 2.33 (1.84-3.41) | 6.14 (4.77-7.41) | 7.06 (1.47-10.78) | |

| UK | 0.58 (0.49-0.71) | 0.73 (0.16-1.56) | 658.75 (284.57-1007.77) | 47.31 (27.90-83.16) | 5.97 (3.79-9.45) | 2.75 (2.01-3.81) | 7.99 (5.10-10.32) | 11.74 (6.28-16.53) | |

| Ukraine | 0.68 (0.57-0.98) | 0.63 (0.34-1.42) | 532.82 (358.13-754.10) | 26.85 (13.95-40.49) | 4.33 (2.98-6.13) | 2.07 (1.51-2.56) | 6.19 (5.57-7.51) | 8.02 (6.23-10.07) | |

| Modern cultivars | 0.57 (0.42-0.79) | 0.83 (0.44-1.67) | 483.32 (367.77-579.40) | 26.97 (18.20-40.45) | 5.04 (3.43-6.05) | 2.25 (1.97-2.52) | 6.55 (6.31-7.03) | 9.53 (8.19-10.31) | |

| ANOVA | 3.04** | 4.75** | 1.66* | 3.45** | 1.72* | 2.22** | 1.91* | 3.40** | |

| TPC | AA | Ssβg | Ss1 | Sucrose | Verbascose | Raffinose | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | 0.63** | ||||||

| Ssβg | -0.08 | -0.27** | |||||

| Ss1 | -0.17* | -0.34** | 0.80** | ||||

| Sucrose | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.06 | |||

| Verbascose | -0.25** | -0.45** | 0.47** | 0.58** | 0.16 | ||

| Raffinose | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.23** | 0.55** | 0.39** | |

| Stachyose | 0.07 | -0.11 | 0.27** | 0.39** | 0.41** | 0.64** | 0.72** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).