Submitted:

22 December 2025

Posted:

23 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Intermittency and Variability: Solar generation is dependent on weather conditions and diurnal cycles; Rapid fluctuations can cause voltage instability and frequency deviations; Limited predictability complicates real-time grid balancing;

- Grid Stability and Reliability: Reduced system inertia due to inverter-based solar generation; Increased risk of cascading failures during high solar penetration; Protection system miscoordination in distribution networks;

- Energy Storage Constraints: High costs and limited lifespan of battery energy storage systems (BESS); Challenges in optimal sizing and placement of storage; Environmental and supply-chain concerns related to battery materials;

- Infrastructure and Grid Flexibility: Legacy grid infrastructure not designed for bidirectional power flow; Congestion in transmission and distribution networks; Limited hosting capacity for distributed solar systems;

- Cybersecurity and Digitalization Risks: Increased reliance on digital monitoring and control systems; Vulnerability to cyber-attacks targeting smart inverters and grid communication networks; Data integrity and privacy concerns;

- Regulatory and Market Barriers: Lack of adaptive grid codes for high solar penetration; Inadequate market mechanisms to reward flexibility and ancillary services; Policy uncertainty affecting long-term investment;

- Strategy Development for Enhancing Energy Security and Resilience: Advanced Forecasting and Grid Management; Energy Storage and Hybrid Systems; Strategic deployment of grid-scale and distributed energy storage; Hybrid solar systems combining PV with wind, hydro, or thermal generation; Vehicle-to-grid (V2G) integration as a distributed storage resource; Smart Grid and Digital Technologies; Grid Infrastructure Modernization; Policy and Market Reforms; Resilience-Oriented Planning; Research Gaps and Future Directions.

2. State of Art

- A.

- Why Solar Integration Matters for Energy Security & Resilience?

- ●

- Solar photovoltaic (PV) power is increasingly central to clean energy transitions worldwide due to its scalability, low operating cost, and decarbonizing potential;

- ●

- Its expanded adoption contributes to energy security by diversifying generation sources, reducing dependence on imported fuels, and cushioning against fuel price volatility and supply disruptions;

- ●

- At the same time, integrating large amounts of solar capacity into existing grids poses challenges that require sophisticated strategies to maintain grid stability and resilience.

- ●

- Technical Challenges Driving Strategy Development – Effective strategies must address several technical hurdles:

- ●

- Variability and Intermittency: Solar output fluctuates with weather and time of day, making it difficult to match generation with demand predictably; Grid management must handle rapid power swings without causing frequency or voltage instability;

- ●

- Reduced System Inertia: Traditional synchronous generators provide mechanical inertia that stabilizes frequency. PV systems, connected via power electronics (inverters), lack this inherent inertia, increasing the grid’s sensitivity to disturbances and frequency excursions;

- ●

- Power Quality Issues: Integrating PV at scale can generate harmonics, voltage fluctuations (sags and swells), and reactive power imbalances unless advanced control and grid support technologies are deployed;

- ●

- Distribution Network Constraints: High distributed solar penetration can stress low-voltage networks with reverse power flows if not properly planned or controlled, necessitating adaptive network design and control logic.

- ●

- B. State-of-the-Art Strategic Approaches:

- ●

- Advanced Control & Forecasting Systems: Modern grid strategies go beyond static planning to include dynamic control architectures: Coordinated control of PV inverters, FACTS devices, and storage can significantly improve stability and fault response times while reducing harmonic distortion. Advanced controllers with AI and predictive forecasting (e.g., LSTM, reinforcement learning) are being explored to better anticipate solar variability and optimize control decisions: Machine learning and AI are increasingly used to enhance security assessments, operational planning, and real-time grid stability analysis, offering a proactive resilience posture against complex, unpredictable grid states;

- ●

- Smart Grid and Digitalization Strategies: To integrate solar effectively and resiliently, grids are being transformed into smart, responsive infrastructures: Deployment of smart sensors, automated control, and communication systems helps balance supply and demand and provides rapid detection and response to faults or fluctuations; Demand response, distributed control schemes, and real-time monitoring enable flexible load management to absorb solar variability efficiently;

- ●

- Energy Storage Integration: Energy storage (e.g., batteries, pumped hydro) is now a central pillar of strategic planning: Storage buffers solar intermittency by storing excess generation for use during low-generation periods, improving reliability and smoothing output curves; Hybrid PV + storage systems help reduce price volatility and enhance resilience during grid stress or extreme conditions;

- ●

- Microgrids and Distributed Energy Resources: Localized microgrids equipped with PV and storage offer resilience benefits: They can operate autonomously (island mode) during grid outages, maintaining service for critical loads and reducing recovery time after disturbances; Microgrid strategies incorporate threat and vulnerability assessments to strengthen resilience to both physical failures and cyber threats;

- ●

- Policy, Planning & Network Investment: Strategic success also depends on policy frameworks and infrastructure planning: Long-term grid planning and interconnection frameworks (e.g., EU sustainable grid conclusions) emphasize coordination across regional and national systems, enhancing supply security and decarbonization targets; National energy plans (e.g., Romania’s integrated energy and climate plan) promote storage development and flexible load initiatives to integrate more renewables effectively.

- ●

- C. Emerging Trends in Strategy Development:

- ●

- AI-Assisted Grid Management: Artificial intelligence is rapidly becoming integrated into operational and planning tools—supporting real-time stability analysis, risk prediction, and automated control patterns that adapt to changing conditions;

- ●

- Resilience Optimization via Reinforcement Learning: Reinforcement learning frameworks (e.g., Deep Q Networks) are being applied to optimize investment and operational decisions under extreme weather and uncertainty, improving both cost-efficiency and resilience outcomes;

- ●

- Hybrid Energy Systems: Integrating solar with other renewables (wind, hydro) and advanced power quality conditioners improves overall reliability and reduces dependency on any single generation source.

- ●

- Key Pillars for Strategic Success

- ●

- Flexibility & Storage – Function: Smooths variability; enhances operational stability;

- ●

- Smart Grid Technologies – Function: Enables real-time control and demand management;

- ●

- Advanced Forecasting & AI – Function: Predicts and adapts to variability;

- ●

- Policy & Planning Integration – Function: Aligns infrastructure investments with resilience goals;

- ●

- Microgrid and DER Deployment – Function: Provides localized backup and resilience.

2.1. The Current Situation of the Romanian Power System – SWOT Analysis

2.1.1. Strengths:

- Energy diversity: The National Energy System (SEN) relies on a relatively diversified energy mix, including hydro, nuclear, thermal (coal and gas), and renewable sources (wind, solar, biomass);

- Existing nuclear capacity: The Cernavodă Nuclear Power Plant provides a stable energy supply, contributing to system stability;

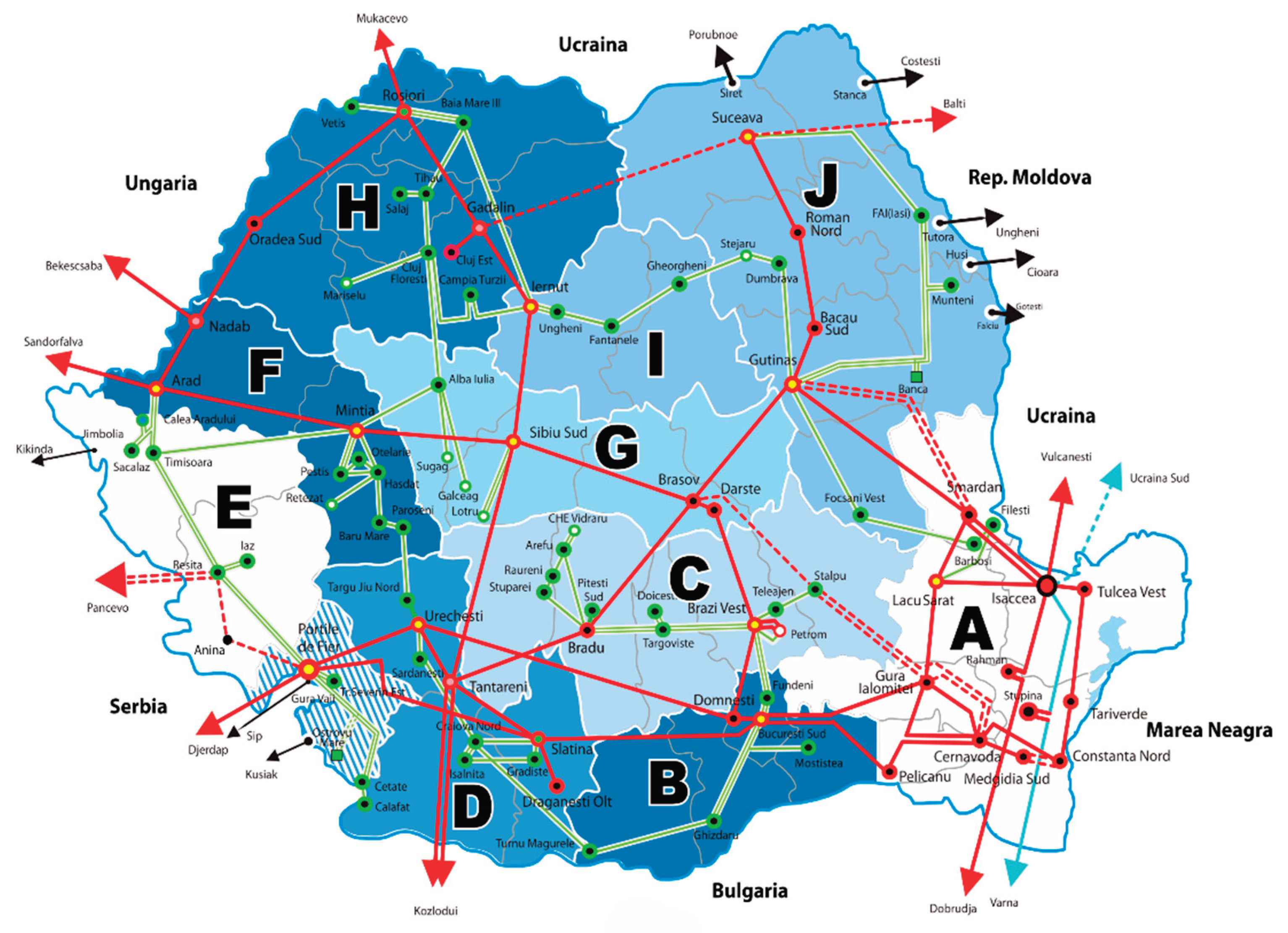

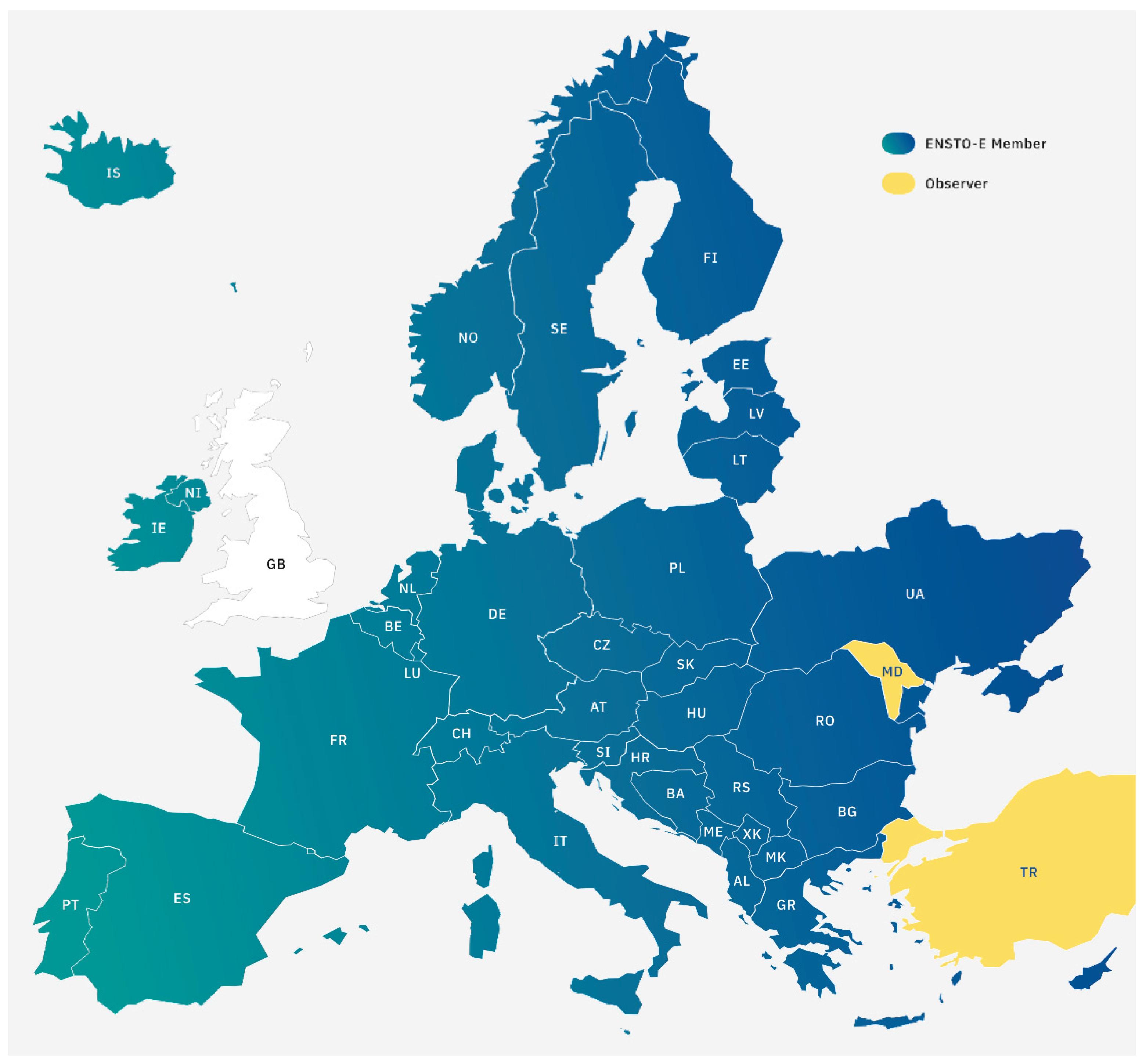

- Interconnected power grid: Romania is integrated into the European ENTSO-E network, facilitating energy trade and enhancing supply security;

- Local natural resources: The presence of hydropower plants and natural gas resources helps reduce dependence on external imports;

- Developing regulations and policies: National strategies for energy transition and energy efficiency are in place, aligned with EU directives.

2.1.2. Weaknesses:

- Aging infrastructure: Some coal-fired plants and power grids are technologically outdated, reducing efficiency and increasing maintenance costs;

- Dependence on fossil fuels: Although diversified, the SEN still relies significantly on coal and gas for energy production;

- Insufficient investment in renewables: Renewable energy production capacity is limited compared to potential and EU targets;

- Technological and cybersecurity risks: Modernization of the SEN’s digital infrastructure is ongoing, increasing vulnerability to cyberattacks;

- High energy costs: Energy prices can be volatile and influenced by external factors, affecting economic competitiveness.

2.1.3. Opportunities:

- Green energy transition: EU funds for green energy and energy efficiency can support SEN development;

- Renewable energy development: Exploiting wind and solar potential can reduce dependence on fossil fuels and carbon emissions;

- Digitalization and smart grids: Implementing smart grids can optimize energy distribution and consumption;

- Infrastructure investment and modernization: Upgrading old power plants and expanding energy storage capacity can enhance energy security;

- Regional cooperation: Interconnection with other European countries can enable production-consumption balancing and profitable energy trade.

2.1.4. Threats:

- Increasing energy demand: Rising consumption without infrastructure development may lead to system instability;

- Vulnerability to international crises: Dependence on gas and fossil fuel imports from geopolitically sensitive areas may pose major risks;

- Climate change: Extreme weather events (droughts, floods) can affect hydro and other energy production sources;

- Strict international regulations: Rapid adaptation to EU emission reduction standards can be costly;

2.2. The Current Situation of the European Power System – SWOT Analysis

2.2.1. Strengths:

- Continental integration and coordination: ENTSO-E brings together transmission system operators from 39 European countries, ensuring coordinated planning and operation of the cross-border energy system;

- Robust infrastructure: Well-developed electricity network with interconnections between countries, enabling energy exchanges and stability in case of local demand or shortages;

- Accelerated energy transition: Leader in integrating renewable energy sources, supporting the EU’s climate neutrality goals by 2050;

- Standardization and regulation: Development of European Network Codes that facilitate interoperability and safe operation of the electricity market;

- Advanced monitoring and data: Platforms like the ENTSO-E Transparency Platform provide real-time data on production, consumption, and energy transactions.

2.2.2. Weaknesses:

- Dependence on aging physical infrastructure: Some member countries rely on outdated power plants and transmission lines, with risks of outages or energy losses;

- Vulnerability to renewable fluctuations: Massive integration of wind and solar energy introduces instability, requiring advanced storage and flexibility solutions;

- Differences among member countries: Uneven levels of network development and technology create challenges for harmonized European-scale operation;

- Bureaucracy and slow processes: Strategic decisions and cross-border projects often involve lengthy timelines and complex negotiations.

2.2.3. Opportunities:

- Digitalization and smart grids: Implementation of smart grids and IoT solutions for demand management and distribution optimization;

- Energy storage and advanced batteries: Development of storage technologies can enhance system flexibility and renewable integration;

- Electrification of transport: Growing demand for electric mobility can be managed through integrated planning and grid balancing services;

- EU funding and Green Deal: Interconnection and grid modernization projects benefit from significant EU funding;

- Integration of hydrogen and new energy sources: Development of infrastructure for green hydrogen and other alternative fuels can reduce fossil fuel dependence.

2.2.4. Threats:

- Geopolitical crises and energy dependence: International conflicts and reliance on imported gas and fossil fuels can affect system stability;

- Cybersecurity risks: Increased digitalization raises vulnerability to cyberattacks on critical networks;

- Extreme climate change events: Severe weather (storms, droughts) can impact energy production and distribution;

- Energy market volatility: Energy prices and divergent national policies can cause economic and operational instability;

2.3. Organizations and Experts Active in Energy Security and Resilience

2.3.1. Organizations

- Energy Watch Group (EWG): Coverage / Relevance: An international network of scientists and parliamentarians researching global developments in energy (fossil fuels, renewables, uranium) and scenarios for ensuring long-term secure energy supply;

- Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei (FEEM): Coverage / Relevance: An international think tank focused on environment, sustainable development, and global governance, with significant activity in energy and energy policy;

- Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) – “Energy and Security Programme”: Coverage / Relevance: Analyzes the connection between national security, geopolitics, and the energy transition; studies energy infrastructure vulnerabilities, geopolitical risks, and cyber threats;

- European Initiative for Energy Security (EIES): Coverage / Relevance: A recent initiative (2023) aimed at securing energy infrastructure, critical supply chains, and strategic coordination in the European context;

- International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) – Energy Department: Coverage / Relevance: Focuses on systems analysis, modeling, and scenarios related to energy, environment, and development — contributing to global perspectives on sustainability and energy security;

- Ifri – Center for Energy & Climate: Coverage / Relevance: Conducts research on energy geopolitics, global energy markets, the energy transition, and implications for security and climate.

2.3.2. Experts

- Fatih Birol – Economist and energy expert, Executive Director of the International Energy Agency (IEA). Globally influential on energy policies, supply security, and the transition to decarbonization;

- Claudia Kemfert – Member of the Scientific Advisory Board of the EWG; expert in energy economics and sustainability, active in European energy policies and clean energy scenarios;

- Wolfgang Kröger – Specialist in technical safety and risk analysis in energy systems and critical infrastructure; has studied the vulnerability and resilience of power grids;

- Keywan Riahi – Scientist at IIASA; focuses on energy modeling, sustainable development, and long-term scenarios for global energy security and climate change adaptation;

- Dan Marks – Researcher at RUSI, specializing in energy security and the links between energy, geopolitics, and national security; involved in analyses of energy transition risks;

- Susanne Nies – Energy and climate expert for Eastern Europe and the EU; involved in energy policy, transition, and supply security projects;

- Mycle Schneider – Nuclear consultant and critic of nuclear energy, with decades of experience in energy risk analysis, energy policy, and supply security;

- Isabelle Dupraz – Deputy Director at EIES, expert in European energy policies, energy supply chain security, and strategies to reduce critical dependencies;

- Mourad Debbabi – Professor at the Gina Cody School of Engineering & Computer Science, Concordia University (Canada). Fields: cyber threat intelligence, cyber-physical systems security, smart grid security, cybersecurity & privacy. Board member of the “Critical Energy Infrastructure (F4)” section;

- José Matas – Department of Electrical Engineering, Polytechnic University of Catalonia, Spain. Fields: power electronics, grid monitoring, smart energy systems, and microgrids. Section Editor-in-Chief for the “Smart Grids and Microgrids (A1)” section;

- Tapas Mallick – Environment & Sustainability Institute, University of Exeter, UK. Fields: renewable energy, energy integration, materials, sustainability; involved at board level in Energies;

- Carlos Henggeler Antunes – University of Naples “Federico II,” Italy. Fields: electric distributors/lines, power quality, smart grid, electric networks. Member of the Energies board;

- Christopher Dent – Edge Hill University, UK. Interests: energy security and the global economic system, renewable energy, sustainable development;

- Erik Gawel – Specialist in energy economics/policy; board member of the “Energy Economics and Policy (C)” section. Relevant fields: energy policies, sustainability, energy transition, influencing macro-level energy security;

- Mark Deinert – Dept. of Mechanical Engineering, University of Texas at Austin, USA. Board member of the “Energy Economics and Policy (C)” section. Fields: energy system analysis, policy, long-term planning.

3. Solar Power – Elements of Ensuring Energy and National Security

- A.

- Conceptual Framework: Energy Security & National Security

- ●

- Energy security broadly means reliable access to affordable and resilient energy;

- ●

- National security adds geopolitical stability, economic resilience, and defense readiness;

- ●

- Solar power influences these by: Reducing vulnerability to global fossil fuel price volatility; Lowering strategic risks from supply disruptions; Decentralizing generation (enhancing local resilience); Supporting critical infrastructure (hospitals, communication, defense) with distributed energy systems.

- ●

- B. Core Elements of Solar Power in National Energy Security

- ●

- Diversification of Energy Mix: Solar contributes to diversification by decreasing dependency on: Imported oil, gas, coal; Single sources of electricity generation. Diversified energy mix: Mitigates market and geopolitical shocks; Improves price stability; Enhances national control over energy provisioning; [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]

- ●

- Reliability & Resilience: Solar power can improve grid reliability through: Distributed generation (DG): localized solar systems reduce load on transmission infrastructure and vulnerabilities to central grid failure.s; Microgrids with solar + storage: resilient during extreme weather or attacks; Hybrid configurations: solar combined with wind, storage or conventional sources increases reliability. Resilience elements: Rapid recovery after outages; Protection of critical sectors.; Redundancy via multiple generation sites;

- ●

- Technological Independence & Supply Chain Security; Solar technologies require: Solar PV modules; Inverters and power electronics; Energy storage (batteries); Rare earth and semiconductor materials. Security considerations include: Supply chain diversification: avoiding overdependence on a single country or supplier; Local manufacturing capabilities: reduces geopolitical risks and trade vulnerabilities; Resource security: responsible sourcing of critical minerals;

- ●

- Economic Security: Solar power can enhance economic stability by: Reducing fuel import bills; Creating jobs in manufacturing, installation, maintenance; Stimulating innovation in clean technologies; Attracting investment in infrastructure and grid modernization; Lower energy costs also: Improve competitiveness of industries; Stabilize consumer prices;

- ●

- Environmental and Public Health Benefits: Solar reduces: Greenhouse gas emissions; Air pollution and related health costs; Environmental stability is linked to national security through: Reduced climate-related conflicts; Water conservation (solar PV uses minimal water vs. thermal power); Protecting agricultural productivity and infrastructure;

- ●

- C. Policy and Governance Dimensions

- ●

- Strategic Energy Policy: Effective national solar strategies often: Set renewable energy targets; Provide incentives (tax credits, feed-in tariffs); Support research and development;

- ●

- Regulatory and Institutional Frameworks: Strong governance requires: Clear interconnection standards; Grid access rules for distributed energy; Security standards for critical digital infrastructure in smart grids;

- ●

- International Cooperation: International agreements can secure: Technology exchange; Supply chain resilience; Joint R&D; Climate commitments (e.g., NDCs under the Paris Agreement).

- ●

- D. Technical and Operational Dimensions

- ●

- Integration with the Grid: Challenges and solutions: Intermittency: solar output fluctuates daily and seasonally; Storage systems: batteries, pumped hydro, thermal storage; Forecasting technologies: better resource planning;

- ●

- ●

- E. Case Studies & Best Practices (Generic Examples) - (Note: these are illustrative categories — real national examples may be explored for deep research):

- ●

- High-Penetration Solar Grids: Countries with high renewable shares (e.g., Germany, California/USA) manage integration with storage and demand response;

- ●

- Decentralized Solar in Remote Regions: Isolated communities use solar + storage for self-sufficiency, boosting resilience;

- ●

- Solar in Defense Infrastructure: Military bases use on-site solar with microgrids to ensure energy autonomy.

- ●

- F. Challenges and Limitations - Solar power also faces constraints:

- ●

- Technical – Challenges: Intermittency; storage costs;

- ●

- Economic – Challenges: Upfront capital costs; market design;

- ●

- Environmental – Challenges: Land use; material sourcing;

- ●

- Security – Challenges: Cyber threats; supply chain dependencies;

- ●

- Policy – Challenges: Regulatory barriers; inconsistent incentives.

4. Strategic Foundations for Improving Resilience

4.1. Theoretical Foundations

- Resilience theory: robustness, adaptability, recoverability;

- Complex networks theory: cascading failure modeling, topology optimization;

- Control theory: resilient control, fault-tolerant control, self-healing grids;

- Risk theory: probabilistic risk assessment, scenario analysis, stress testing;

4.2. Applied Approaches

- Hardening critical substations, transmission corridors, and ICT infrastructure;

- Implementing self-healing networks via automated switching and protection;

- Deploying predictive maintenance systems using AI;

- Expanding microgrids for emergency islanding and continuity of service;

- Strengthening cross-border interconnections for supply security;

4.3. Main Categories of Threats

4.3.1. Physical and Technical Threats:

- Aging infrastructure leading to equipment failures and cascading outages;

- Overloading of transmission lines during peak demand conditions;

- Insufficient redundancy in generation, transmission, or distribution networks;

- Natural disasters (storms, wildfires, floods, earthquakes) damaging equipment;

- Industrial accidents (transformer explosions, fires, chemical hazards);

- Grid instability due to variability of renewable sources without adequate storage.

4.3.2. Cybersecurity Threats:

- Cyberattacks on SCADA systems (malware, ransomware, remote intrusion);

- Manipulation of grid control algorithms causing instability or blackouts;

- Data breaches compromising operational security or strategic planning;

- Attacks on supply chain components (hardware and software vulnerabilities);

- IoT-based threats due to increased digitalization of grid assets.

4.3.3. Energy Supply & Market Threats:

- Dependence on imported fuels (oil, gas, coal);

- Global price volatility affecting affordability and operational planning;

- Insufficient diversification of generation sources;

- Resource scarcity caused by geopolitical conflicts;

- Market manipulation or monopolistic behaviors impacting availability.

4.3.4. Geopolitical and Strategic Threats:

- Cross-border energy dependence creating strategic vulnerabilities;

- Hybrid warfare targeting critical energy infrastructure;

- Terrorism or sabotage of power plants, pipelines, or grid nodes;

- Political instability affecting international energy agreements.

4.3.5. Environmental and Climate Threats:

- Extreme weather events increasing in frequency and intensity;

- Heatwaves reducing generation efficiency and increasing load;

- Droughts affecting hydroelectric power availability;

- Pollution regulations forcing rapid technological changes;

- Long-term climate shifts requiring adaptation of infrastructure.

4.3.6. Technological and Operational Threats:

- Insufficient automation or outdated control systems;

- Poor maintenance practices leading to system degradation;

- Human error in system operation or emergency response;

- Inadequate forecasting for load, weather, and renewable output;

- Slow adoption of smart grid technologies.

4.3.7. Socioeconomic and Policy Threats:

- Lack of investment in grid modernization and resilience;

- Regulatory uncertainty disrupting project planning;

- Public opposition to new energy infrastructure (NIMBYism);

- Workforce shortages in engineering and technical fields;

- Inequitable energy access affecting national stability.

4.3.8. Emerging Global Threats:

- AI-driven attacks on grid-control systems;

- Energy storage system failures (battery fires, thermal runaway);

- Interdependencies with digital and telecom infrastructure;

4.4. Elements of Instability and Insecurity and Their Mode of Propagation

| Dysfunction/Deficiency/Non-compliance → | vulnerability → | risk → | threat → | Danger → | Aggression | |

| 1 |

Dysfunction:

Lack, precariousness or non-compliance with the activities of exploitation, maintenance and development of The Power Transmission Grid (PTG) ● lack, precariousness or non-compliance with exploitation procedures; ● lack, precariousness or non-compliance with maintenance procedures; ● lack, precariousness or non-compliance with development procedures. |

Poor management of the transmission operator activity (exploitation, maintenance and development) of the Power Transmission Grid installations. | Risk of technical incident (isolated/associated), disturbance or technical damage. | Technological threat. | Danger of technological instability (incident/damage) → blackout. | - |

| 2 |

Dysfunction:

Lack, precariousness or non-compliance with the activities of operative and operational management of the National Power System (NPS): ● lack, precariousness or non-compliance with dispatching procedures; |

Poor management of the system operator activity (operative and operational management of The National |

Risk of operative and/or operational incident.

|

Operative and operational threat. | Danger of operative and operational insecurity→ blackout. | - |

|

● lack or precariousness of investments in EMS/SCADA infrastructure;

● lack, precariousness or non-compliance with cybersecurity procedures. |

Power System). |

|

||||

| 3 |

Dysfunction:

Lack or precariousness of investments in the infrastructure of The Power Transmission Grid. |

Instability and insecurity of The National Power System caused by lack or precariousness of investments in the energy infrastructure. | Risk of partial or total disconnection of the NPS – blackout. | Threat of energy crisis. | Danger of national insecurity → lack of national welfare. | - |

| 4 |

Dysfunction:

Lack, precariousness or non-compliance with the cybersecurity activity within the National Power System: ● lack, precariousness or non-compliance with cybersecurity procedures; ● underperforming EMS/SCADA infrastructure. |

The precariousness of Cybersecurity activity. | Risk of cyberattack. | Cyber threat (terrorist). | Danger of cyber insecurity → blackout. | Cyberattack→ blackout. |

| 5 |

Dysfunction:

Lack, precariousness or non-compliance with Occupational Health and Safety activity within the jobs: ● lack, precariousness or non-compliance with Occupational Health and Safety procedures; ● lack, precariousness or non-compliance with the electrical safety procedures; ● lack, precariousness or non-compliance with the assessment and audit in terms of Occupational Health and Safety; ● lack, precariousness or non-compliance with the Prevention and Protection Plan. |

The precariousness of Occupational Health and Safety activity. | Risk of injury (electrocution) and/or occupational illness. | Threat of death. | Danger of human insecurity. (work accident). | Physical attack. |

| 6 |

Dysfunction:

Lack, precariousness or non-compliance with the activity of protection and security of critical infrastructures within the National Power System: ● lack, precariousness or non-compliance with Critical Infrastructure Protection procedures; ● lack, precariousness or non-compliance with the Security Plan at the Operator; ● lack, precariousness or non-compliance with physical security procedures; ● lack, precariousness or non-compliance with the strategy for the protection of national and european critical infrastructure on the Power Transmission Grid. |

The precariousness of the protection and security activity of critical infrastructures. | Risk of terrorist attack. | Terrorist threat. | Terrorist danger → blackout. | Terrorist attack: armed/bomb → blackout. |

| 7 |

Dysfunction:

Lack, precariousness or non-compliance with the development, safety and security strategies within the National Power System: ● lack, precariousness or non-compliance with the development strategy on the Power Transmission Grid; ● lack, precariousness or non-compliance with the protection and security strategy of critical infrastructures within the National Power System; ● lack, precariousness or non-compliance with the power safety strategy of The National Power System. |

Lack of strategies for the development of The Power Transmission Grid, critical infrastructure protection and cybersecurity of The National Power System. | Risk of partial or total disconnection of the NPS – blackout. | Threat of energy crisis. | Danger of energy crisis → national insecurity. | - |

| 8 |

Deficiency:

Removing coal-fired capacities from production and increasing consumption through energy aid provided for the Republic of Moldova and Ukraine |

Power deficit in The National Power System. | Risk of power shortage and purchasing import electricity → the unprofitability of The NPS. | Economic threat. | Danger of economic crisis → national insecurity. | - |

| 9 |

Deficiency:

Taking over energy produced from renewable resources. |

Deficit regarding the capacity of The National Power System. | Risk of non-symmetric and un-equilibrated loading of electricity → partial or total disconnection of The NPS – blackout. | Threat of energy crisis. | Danger of energy crisis → national insecurity. | - |

| 10 |

Deficiency:

A number of installations for the production, transmission and distribution of electricity are obsolete and technologically outdated, with high consumption and operating costs, causing very frequent faults, disturbances and damage. |

Deficit of high-performance energy installations in The Power Transmission Grid installations. | Major risk of associated technical incident and technical damage → blackout. | Threat of energy crisis. | Danger of energy crisis → national insecurity. | - |

| 11 |

Deficiency:

Energy prices do not reflect the security of energy supply depending on the position of the consumer/producer in the load curve. |

Deficit of incentives for investments in top-notch capacities. | Risk of energy insecurity. | Threat of energy crisis. | Danger of energy crisis → national insecurity. | - |

| 12 |

Deficiency: Lack of electricity storage elements |

Deficit of electricity storage infrastructures | Risk of energy insecurity. | Threat of energy crisis. | Danger of energy crisis → national insecurity. | - |

| 13 |

Deficiency:

Lack of infrastructures regarding the closure of the 400 kV ring |

Non-closure of the 400 kV ring in the N and S-W area of Romania. | Risk of partial or total disconnection of The NPS – blackout. | Threat of energy crisis. | Danger of energy crisis → national insecurity. | - |

| 14 |

Deficiency:

Lack of financial measures to support projects and programs to increase energy efficiency and lack of European funds for investments in a modern energy infrastructure. |

Deficit of financial resources. | Financial risk. | Financial threat. | Danger of financial crisis → economic insecurity. | - |

| 15 |

Deficiency:

Reduced research-development-dissemination capacity in the energy and mining sector. |

Deficit of research-development resources. | Risk of research-development deficit. | Threat of research-development crisis. | Danger of research-development crisis → energy insecurity | - |

| 16 |

Deficiency:

The intervention of the political factor or nepotism within the transmission company (top management, territorial transmission units, exploitation centers, power substations and dispatchers). |

Deficit of qualified and overqualified human resource. | Risk of qualified and overqualified human resources deficit → mistakes of the management, operative and dispatching personnel → blackout. | Threat of qualified and overqualified personnel crisis. | Danger of personnel crisis → energy insecurity. | - |

| 17 |

Deficiency:

Possible thefts and sabotage from own facilities |

Deficit of honest and serious human resources. | Risk of sabotage. | Threat of sabotage. | Danger of sabotage → energy insecurity. | Attack from the inside (theft/armed attack/cyberattack) → blackout |

| 18 |

Deficiency:

Political and legislative unpredictability. |

Deficit of political and legislative stability. | Political and legislative risk. | Political and legislative threat. | Danger of political and legislative crisis → national insecurity. | - |

| 19 |

Non-compliance:

Unexpected disconnection of protective equipment and devices within power substations. |

Precariousness and non-performance of energy equipment and appliances within The Power Transmission Grid | Risk of unexpected disconnection→ partial or total blackout. | Threat of energy crisis. | Danger of energy crisis → national insecurity. | - |

| 20 |

Non-compliance:

Poor condition of energy equipment and appliances. |

Lack of electricity – possible local, zonal, regional or national blackout. | Risk of energy crisis. | Threat of national collapse. | Danger of national collapse → lack of national welfare. | - |

| 21 |

Non-compliance:

Lack of electricity from national systems. |

The dependence of national systems on electricity. | Risk of energy crisis → national crisis → national insecurity → collapse | Threat of national collapse. | Danger of national collapse → lack of national welfare. | - |

| 22 | - | - | Natural risk. | Threat of natural disaster: | Danger of natural disaster. | Natural disasters attacks. |

| Nr. Crt. |

THE IDENTIFIED VULNERABILITY (generated by dysfunction, deficiency and/or non-compliance) |

GRAVITY ESTIMATION | IMPACT ESTIMATION | SCENARIO TYPE |

| 1. | Poor management of the transmission operator activity (exploitation, maintenance and development) of the Power Transmission Grid installations. | 5. Very high | 5. Very high | 1. The worst |

| 2. | Poor management of the system operator activity (operative and operational management of The National Power System). | 4. High | 4. High | 2. Plausible the worst |

| 3. | Instability and insecurity of The National Power System caused by lack or precariousness of investments in the energy infrastructure. | 5. Very high | 5. Very high | 1. The worst |

| 4. | The precariousness of Cybersecurity activity. | 5. Very high | 5. Very high | 1. The worst |

| 5. | The precariousness of Occupational Health and Safety activity. | 4. High | 4. High | 3. Moderate |

| 6. | The precariousness of the protection and security activity of critical infrastructures. | 5. Very high | 5. Very high | 2. Plausible the worst |

| 7. | Lack of strategies for the development of The Power Transmission Grid, critical infrastructure protection and cybersecurity of The National Power System. | 3. Medium | 3. Medium | 3. Moderate |

| 8. | Power deficit in The National Power System. | 5. Very high | 5. Very high | 2. Plausible the worst |

| 9. | Deficit regarding the capacity of The National Power System. | 5. Very high | 5. Very high | 2. Plausible the worst |

| 10. | Deficit of high-performance energy installations in The Power Transmission Grid installations. | 4. High | 4. High | 3. Moderate |

| 11. | Deficit of incentives for investments in top-notch capacities. | 4. High | 4. High | 3. Moderate |

| 12. | Deficit of electricity storage infrastructures | 3. Medium | 3. Medium | 3. Moderate |

| 13. | Non-closure of the 400 kV ring in the N and S-W area of Romania. | 5. Very high | 5. Very high | 2. Plausible the worst |

| 14. | Deficit of financial resources. | 4. High | 4. High | 3. Moderate |

| 15. | Deficit of research-development resources. | 4. High | 4. High | 3. Moderate |

| 16. | Deficit of qualified and overqualified human resource. | 5. Very high | 5. Very high | 2. Plausible the worst |

| 17. | Deficit of honest and serious human resources. | 5. Very high | 5. Very high | 2. Plausible the worst |

| 18. | Deficit of political and legislative stability. | 4. High | 4. High | 3. Moderate |

| 19. | Precariousness and non-performance of energy equipment and appliances within The Power Transmission Grid |

5. Very high | 5. Very high | 2. Plausible the worst |

| 20. | Lack of electricity – possible local, zonal, regional or national blackout. | 5. Very high | 5. Very high | 1. The worst |

| 21. | The dependence of national systems on electricity. | 5. Very high | 5. Very high | 1. The worst |

| Nr. Crt. |

IDENTIFIED INSTABILITY AND INSECURITY ELEMENT | TECHNICAL AND MANAGERIAL MEASURES REGARDING THE SAFETY AND SECURITY OF THE NATIONAL POWER SYSTEM |

| 1. | Poor management of the transmission operator activity (exploitation, maintenance and development) of the Power Transmission Grid installations. |

Technical measures: ● Continuous monitoring of functioning parameters (voltage, current, temperature, load); ● Implementation of SCADA systems and protection automation for rapid identification of faults; ● Preventive and predictive maintenance plans based on real wear data; ● Periodic checks of protection and automation equipment; ● Quality control of equipment and materials used in the works; ● Internal technical audits regarding the compliance of installations with The National Authority for Energy Regulations regulations and ENTSO-E standards. Organizational measures: ● Developing and updating standard operational procedures for exploitation and maintenance; ● Authorization and certification of personnel according to the level of competence (The National Authority for Energy Regulations, State Inspection for the Control of Boilers, Pressure Vessels, and Lifting Installations, etc.); ● Periodic training on working under voltage, fire prevention and emergency response in case of damage; ● Access control in facilities (badges, registers, video surveillance); ● Establishing a clear reporting structure and responsibilities for each hierarchical level; ● Implementation of an information security and safety management system (ISO 27001, ISO 45001). Physical and cyber security measures: ● Detection and alarm systems for fires, intrusions and dielectric oil leaks; ● Backup and redundancy for SCADA systems and dispatching servers; ● Cyber protection of industrial control systems (ICS/SCADA) through firewalls, network segmentation and regular updates; ● Cyber incident response plans and cooperation with energy security authorities. Prevention and emergency response measures: ● Developing emergency plans for damage, fires, extreme weather events or cyberattacks; ● Periodic simulations and exercises with the operative teams; ● Equipping intervention teams with safe equipment and means of communication; ● Interinstitutional cooperation with The Romanian General Inspectorate for Emergency Situations, The Police, The National Authority for Energy Regulations and Transelectrica. Corrective and continuous improvement measures: ● Periodic analysis of operational performance indicators; ● Implementing lessons learned from incidents and non-compliances; ● Annual review of the operational safety policy; ● Transparent reporting to authorities and the public (in accordance with energy transparency requirements). |

| 2. | Poor management of the system operator activity (operative and operational management of The National Power System). |

Strengthening the operative management of The National Energy Dispatcher: ● Implementation of a unified command and control center with real-time analysis capabilities; ● Modernization of the SCADA/EMS system with predictive functions based on AI and Big Data; ● Reorganizing decision flows for faster crisis responses. Increasing balancing capacity and system flexibility: ● Development of rapid reaction power plants (gas, hydro, batteries); ● Introducing dynamic balancing services markets; ● Promoting demand management and integrating prosumers. Strengthening the transmission and interconnection grid: ● Investments in 400 kV transmission lines and new interconnections with Hungary, Serbia, Bulgaria, Republic of Moldova; ● Smart Grid projects and synchronous monitoring through PMU (Phasor Measurement Units) grids; ● Increasing the degree of automation and differential protection in critical nodes. Cybersecurity and data protection: ● Periodic cybersecurity audits; ● Implementation of ISO 27001, NIST standards and NIS2 regulations; ● Segregation of operational (OT) networks from corporate IT networks. Preparation and training of operative personnel: ● Crisis simulations and regular training for dispatchers; ● Updating emergency procedures and operating manuals; ● Implementation of a continuous skills assessment system. Governance and decision-making transparency: ● Clarification of responsibilities between strategic and operative management; ● Introduction of performance indicators for operational safety; ● Increasing transparency through periodic public reporting on incidents. |

| 3. | Instability and insecurity of The National Power System caused by lack or precariousness of investments in the energy infrastructure. |

Investment and modernization measures: ● Rehabilitation and digitization of transmission and distribution grids; ● Modernization of existing power plants (hydro, thermal, nuclear) to increase efficiency; ● Investments in renewable sources (solar, wind, biomass, small hydro); ● Development of storage capacities (batteries, hydro-pumping, hydrogen); ● Interconnecting grids with neighboring countries' systems for regional flexibility. Institutional and regulatory measures: ● Legislative stability and predictability for investors; ● Long-term national energy development strategies; ● Improving the governance of state-owned companies in the energy sector; ● Implementation of competitive market mechanisms (trading, transparent bilateral contracts). Security measures: ● Strengthening cyber protection of SCADA systems and control centers; ● Creating strategic energy and fuel reserves; ● Periodic crisis simulations to test system resilience; ● Diversification of supply sources (gas, electricity, oil). Sustainability and efficiency measures: ● Promoting energy efficiency in industry, buildings and transport; ● Stimulating prosumers and energy communities; ● Implementation of smart technologies (smart grids, smart meters); ● Integrating green transition principles into investment plans. |

| 4. | The precariousness of Cybersecurity activity. |

Technical measures: ● Implementation of IDS/IPS systems dedicated to industrial environments; ● Segmentation of IT and OT (Operational Technology) networks; ● Use of certifications and multifactor authentication; ● Continuous monitoring and periodic security audits. Organizational measures: ● Creating and supporting internal incident response teams (CSIRTs); ● Implementation of cybersecurity policies across the entire organization; ● Periodic personnel training (trainings and simulations); ● Introducing cyber risk management into the business strategy. Strategic and legislative measures: ● Cooperation between The National Authority for Energy Regulations, The Romanian National Cyber Security Directorate, Ministry of Internal Affairs and private operators; ● Implementation of the NIS2 Directive regarding the cybersecurity of critical infrastructures; ● Funding research and innovation in the field of energy security; ● Creating an integrated national energy and cybersecurity coordination center. |

| 5. | The precariousness of Occupational Health and Safety activity. |

Organizational measures ● Integration of OHS into the overall energy security strategy; ● Periodic independent audits regarding the state of OHS; ● Creating a safety-oriented organizational culture. Technical measures: ● Digitization of risk monitoring processes (IoT, sensors, AI); ● Automation of high-risk installations; ● Predictive maintenance for critical equipment. Legislative and training measures: ● Alignment of national legislation with European standards (Directive 89/391/EEC); ● Continuous training programs for workers and OHS personnel; ● Implementation of international standards such as ISO 45001 (Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems). Collaboration and communication measures: ● Partnerships between companies, authorities and training institutions; ● Exchange of best practices and transparent incident reporting. |

| 6. | The precariousness of the protection and security activity of critical infrastructures. |

Technical measures: ● Modernization of energy equipment and infrastructures; ● Implementation of international security standards (e.g. ISO 27001, NIS2); ● Redundancy and diversification in energy and transmission sources; ● Controlled and protected digitization (cyber resilience); ● Periodic security audits. Organizational and legislative measures: ● Clarification of responsibilities between authorities (Ministry of Internal Affairs, Romanian Intelligence Service, The National Authority for Energy Regulations, operators); ● Implementation of the National Strategy for Critical Infrastructure Protection; ● Creation of rapid response centers (CERT-Energy); ● Continuity and recovery plans in case of incident; ● Training programs and crisis simulations. Geopolitical and economic measures: ● Diversification of energy sources (renewable, nuclear, liquefied gas); ● Interconnection with European power grids; ● Creating strategic energy reserves; ● Stimulating private and public investments in infrastructure. |

| 7. | Lack of strategies for the development of The Power Transmission Grid, critical infrastructure protection and cybersecurity of The National Power System. |

Technical and operational measures (priority, non-detailed): A. Immediate measures (0–12 months): ● Complete inventory of assets (IT & OT) + critical dependencies map; ● Network segmentation & access control: logical/physical separation of control networks (SCADA/PLC) from corporate networks; role-based access and MFA for network operators; ● Patch & release management for OT/firmware (controlled process, testing in isolated environments before production); ● Early detection and monitoring (SIEM/IDS for OT): centralized collection of relevant telemetry, alerting and response playbooks; ● Continuity plan and red-team / tabletop exercises with authorities and critical operators. B. Medium-term measures (1–3 years): ● Implementation of industrial security standards (IEC 62443) at product and process level; certification for critical equipment; ● Strict supply chain management processes: supplier due diligence, security requirements in contracts, SCRM (supply-chain risk management) assessments; ● Strengthening incident response: sectoral CSIRT/CERT, links with CERT-RO/ENISA and reporting mechanisms according to NIS2; ● Investments in flexibility: storage systems (BESS), demand-side flexibility, interconnections to increase regional resilience. C. Long-term measures (3–7+ years): ● Major PTG modernization projects: new routes, cross-border interconnections, "energy highways" to reduce regional bottlenecks (a measure that the EU promotes); ● Resilient architectures & decentralization of control: microgrids for critical nodes (hospitals, communication centers), autonomous capabilities for isolated operation; ● Sustainable investments in skills: university programs, practical OT cyber training, large-scale incident simulations. Regulatory, governance and financing measures: ● National Strategy for the PTG and energy security – document with clear objectives (5/10/20 years), budget allocation and financing mechanisms (PPP, EU funds, regulated tariffs for investments); ● Framework of cybersecurity obligations for operators (e.g. minimum requirements, audits, sanctions), aligned with NIS2 and ENTSO-E network codes; ● Interinstitutional coordination mechanism (energy minister, transmission operator, ANCOM-like authority, national CERT, army/police for major physical incidents); ● Mechanisms for sharing information between the public-private sector (threat-sharing, anonymized compromise indicators). |

| 8. | Power deficit in The National Power System. |

Measures regarding increasing production capacities and modernizing existing ones: ● Investments in flexible natural gas power plants (e.g. Turceni, Iernut, Mintia); ● Nuclear energy expansion (Cernavodă Units 3 and 4) and Doicești SMR; ● Modernization of hydro power plants and exploitation of micro hydro power plants. Measures regarding the development of storage capacities: ● Implementation of high-capacity batteries and pumped storage hydro power plants (e.g. Tarnița-Lăpuștești); ● Stimulating decentralized storage for prosumers and businesses. Measures to increase system flexibility: ● Introduction of demand management mechanisms (DSM – Demand Side Management); ● Integration of smart technologies into distribution grids (smart grid, smart metering). Measures regarding the diversification of energy sources and supply routes: ● Cross-border interconnections (Romania–Hungary, Romania–Serbia, Romania–Bulgaria, Romania – Republic of Moldova); ● Development of decentralized production (community photovoltaic parks). Measures regarding legislative and strategic framework: ● Implementation of the Energy Strategy of Romania 2025–2035, focusing on security and green transition; ● Tax incentives for investments in clean and efficient sources. |

| 9. | Deficit regarding the capacity of The National Power System. |

Technical and infrastructure measures: ● Modernization and retechnologization of existing power plants (hydro, gas, transitional coal with CCS – carbon capture and storage); ● Development of new production capacities: ➢ Natural gas power plants (flexible, balancing); ➢ Small Modular Reactor (SMR) – new nuclear projects (e.g. Doicești); ➢ Expansion of renewable energy (solar, offshore and onshore wind). ● Investments in energy storage: ➢ Large stationary batteries; ➢ Modernization of pumped storage hydro power plants (Tarnița-Lăpuștești). ● Strengthening transmission and distribution grids – increasing resilience through digitization and automation (smart grids – Smart Grid); ● Regional interconnections with neighbouring countries (Hungary, Bulgaria, Serbia, Republic of Moldova) for rapid balancing. Institutional and market measures: ● Integrated strategic planning – update of the National Integrated Energy-Climate Plan (PNIESC 2030-2050); ● Stimulating private investments through support schemes (CfD - Contracts for Difference, PPAs, European funds); ● Capacity mechanisms – rewarding producers for reserve availability; ● Promoting energy efficiency in industry, buildings and transport; ● Diversification of gas and fuel supply sources (Southern Corridor, LNG). Short-term measures: ● Increasing temporary imports from ENTSO-E networks; ● Flexible operation of hydro power plants; ● Implementation of consumption management systems (DSM – Demand Side Management) to flatten load peaks; ● Ensuring the capacity reserve for balancing the system. |

| 10. | Deficit of high-performance energy installations in The Power Transmission Grid installations. |

Measures regarding the modernization of the physical infrastructure: ● Replacing old equipment with: ➢ Low-loss transformers; ➢ Vacuum or SF₆ circuit breakers with digital control; ➢ High voltage lines (400 kV) with high performance conductors (HTLS – High Temperature Low Sag). ● Expansion and automation of key substations (Gutinaș, Gura Ialomiței, Smârdan, etc.). Measures regarding the digitization of the power system: ● Implementation of a state-of-the-art SCADA/EMS system; ● Use of IoT and smart sensors for equipment monitoring; ● Creating an integrated data analysis center (big data, AI for predictive diagnosis). Cybersecurity measures: ● Application of NIS2 and ISO/IEC 27001 standards; ● Segmentation of OT/IT networks and use of industrial firewalls; ● Periodic security audits and training for personnel. Measures regarding the integration of new technologies: ● Energy storage (Li-ion batteries, hydrogen) for balancing; ● FACTS (Flexible AC Transmission Systems) – STATCOM, SVC, TCSC – for voltage regulation and power flow control; ● HVDC (High Voltage Direct Current) – efficient long-distance interconnections and cross-border integration. Measures to increase regional interconnectivity: ● Strengthening cross-border links (with Hungary, Bulgaria, Serbia, the Republic of Moldova, Ukraine); Active participation in the European energy market (ENTSO-E). Measures regarding the institutional and financial reform: ● Multiannual investment plans (Transelectrica – PTG Development Plan 2025–2034); ● Accessing European funds: Recovery and Resilience Mechanism, Modernization Fund; ● Public-private partnerships for the rapid implementation of advanced technologies. |

| 11. | Deficit of incentives for investments in top-notch capacities. |

Economic and market measures: ● Introduction of a capacity mechanism (Capacity Remuneration Mechanism) - paying producers for their availability to supply energy during peak periods. Examples: UK, Poland, France; ● Flexibility contracts (Flexibility Markets) – remuneration for balancing services provided by batteries, hydro power plants or DSRs (Demand Side Response); ● Tax incentives for investments in storage and flexible plants – accelerated depreciation deductions, income tax exemptions for the first 5–10 years of operation; ● Establishing PPA (Power Purchase Agreements) schemes adapted to flexible capacities, not just to renewables. Technical and infrastructural measures: ● Modernizing grids and increasing regional interconnectivity – allows rapid import/export of energy in imbalance situations; ● Investments in storage (batteries, storage hydro, green hydrogen) – support through grants or non-reimbursable financing (Recovery and Resilience Mechanism, Fund for Modernization); ● Digitization and implementation of smart systems (smart grids) – for better management of demand and supply. Public policy and regulatory measures: ● National strategy for peak capacities and energy flexibility – with clear investment targets by 2030; ● Clarification and stabilization of the National Authority for Energy Regulations / Ministry of Energy regulatory framework – predictability for investors; ● Integrating energy security criteria into national energy planning – for example, in the National Integrated Energy–Climate Change Plan; ● Promoting public-private partnerships (PPP) – for strategic storage projects or backup power plants. Measures for diversifying sources: ● Development of high-efficiency gas/biomethane cogeneration capacities; ● Piloting modular nuclear technologies (SMR) for flexible base production; ● Supporting distributed production and prosumers that can contribute to local balancing. |

| 12. | Deficit of electricity storage infrastructures |

Measures – Policies and regulations: ● Introducing a clear legal framework that recognizes energy storage as a distinct activity (not just production/consumption); ● Support mechanisms (subsidies, green credits, regulated tariffs for balancing services); ● Integrating storage into national energy and climate plans (NECPs). Measures – Investments and infrastructure: ● Building grid-scale batteries (grid-scale storage); ● Modernization of storage hydro power plants; ● Creating microgrids with local storage; ● Integration of electric vehicles as distributed storage sources (Vehicle-to-Grid, V2G). Measures – Innovation and digitization: ● Using artificial intelligence for demand and production forecasting; ● Development of intelligent platforms for energy flow management; ● Implementing blockchain technologies for decentralized energy transactions. Measures – Diversification and resilience: ● Combining multiple types of storage for different time horizons: ➢ batteries (seconds – hours); ➢ hydrogen (days – months); ➢ storage hydro (weeks - months). ● Developing a regional interconnected grid for energy import/export in case of deficit. |

| 13. | Non-closure of the 400 kV ring in the N and S-W area of Romania. |

Measures: ● The construction of the 400 kV Gădălin — Suceava OHL (~260 km) will close the northern bus and it is considered a complex project, with difficult mountainous terrain; it involves new substations (Suceava, possibly Botoșani) and a connection for interconnection with the Republic of Moldova (Suceava–Bălți). The project includes EU funds for modernization; ● The completion of the Iron Gates – Reșița – Timișoara – Săcălaz – Arad axis requires: the construction or retechnologization of some 400 kV segments (220→400 kV conversions where applicable), substations reconnection, and the possible installation of conductors in tunnels/sensitive areas; this corridor was targeted in previous stages by Transelectrica to close the ring in the west. |

| 14. | Deficit of financial resources. |

Immediate measures (0–12 months) — financial and operative stabilization: ● Transparently managed temporary liquidity fund (bridge fund) – to cover current obligations of operators (suppliers, transmission/distribution) without blocking investments, conditioned by recovery plans. (actors: Government + Ministry of Energy + the National Authority for Energy Regulations); ● Recipe towards the gradual elimination of generalist capping measures and the transition to targeted support for the vulnerable – thus restoring the price signal and reducing the budgetary burden (this issue has generated substantial costs in the past); ● State guarantee /coordinated banking facilities for key projects (grids, storage, flexibility) so as to reduce the cost of capital in the short term. (actors: Ministry of Finance + EIB/EBRD/Commercial banks). Medium-term measures (1–5 years) — market mechanisms and infrastructure: ● Implementation/improvement of a capacity mechanism /availability payments to ensure the remuneration of the essential capacity (including storage and flexible plants) – maintains security in critical periods and stimulates investment in flexibility. (Transelectrica has recently published rules for capacity auctions); ● Regulatory reforms for predictability and network access (faster licensing, clarification of network pricing, co-financing mechanisms for network back-up); ● Accelerated grid modernization and digitization program (smart-grid, loss reduction, active demand management). Prioritization on critical areas. (investment needs in the strategy are very high); ● Efficiency reward packages and large-scale energy efficiency programs for industrial consumers and household customers (reduces maximum demand and peak pressure); ● Just transition funds & managed withdrawal mechanisms for vulnerable fossil capacities – avoids unexpected costs (compensation, litigation) and allows for financial planning of closures. Long-term measures (5–15+ years) — structural transformation: ● Massive mobilization of private capital through bankable projects (PPP, project bonds, green bonds) for wind/offshore parks, transitional gas, nuclear if decided, massive storage and cross-border grids; ● Widespread use of EU instruments (Renewables Financing Mechanisms, InvestEU, CEF, RRF/NextGeneration) to co-finance priority projects and provide grant+loan blend; ● Creating a project development ecosystem (Project Development Facility) at the national level to prepare investable projects (standardization of contracts, studies, authorizations) — reduces the risk perceived by investors. |

| 15. | Deficit of research-development resources. |

Strategic measures: ● Developing a National Energy Research Strategy 2030–2050, correlated with the National Integrated Energy-Climate Plan; ● Creation of a National Energy Innovation Fund, financed from emission taxes and European funds; ● Encouraging public-private partnerships between institutes, universities and energy companies; ● Tax incentives for companies investing in energy research and digitization. Technological measures: ● Implementation of smart grids and energy storage systems (batteries, hydrogen); ● Digitization of the power system (IoT, AI, Big Data for monitoring and prediction); ● Research in green hydrogen technologies, microgrids and modular nuclear power plants (SMR); ● Modernization of transmission and distribution infrastructure in order to increase resilience. Educational and institutional measures: ● Training new skills in digital energy, efficiency and risk management; ● Creating university hubs for energy innovation (in collaboration with companies in the field); ● Attracting Romanian researchers from the diaspora through grants and reintegration facilities; ● Simplifying access to European funds for energy R&D projects. |

| 16. | Deficit of qualified and overqualified human resource. |

Immediate measures (1-3 years): ● Accelerated training programs: ➢ Certified courses (The National Authority for Energy Regulations, technical universities, companies) for the retraining of technicians and engineers; ➢ Partnerships with universities (technical): Petroșani, Bucharest, Cluj, Iași, Timișoara, Craiova, etc.. ● Retention programs: ➢ Performance bonuses and loyalty packages for critical personnel; ➢ Flexibility in working hours and non-financial benefits (company housing, internal mobility). ● Public-private partnerships for dual training: ➢ Involvement of companies (Transelectrica, Hidroelectrica, Nuclearelectrica, E-Distribuție) in dual vocational education. ● Digitization of operational processes: ➢ Automating monitoring and maintenance tasks to reduce pressure on human personnel. Medium-term measures (3-7 years): ● Creating a “National Energy Academy” ➢ National platform for continuous training in conventional and renewable energy; ➢ Accredited at European level (EURELECTRIC, ENTSO-E). ● Programs to attract the technical diaspora: ➢ Repatriation through temporary projects, consultancy and university partnerships. ● Integrating digital and cybersecurity skills into all training programs; ● Innovation and international partnerships: ➢ Training internships in European companies for the NPS personnel. Long-term measures (7-15 years): ● Reform of technical education: ➢ Updating the curricula of technological high schools and universities to integrate renewable energy, hydrogen, AI and IoT. ● National strategic planning of human resources in energy: ➢ Creating a national register of skills and deficits by fields (production, transmission, distribution, IT, security). ● Integrating artificial intelligence and digital twins: ➢ For grid simulations, fault prediction, predictive planning; ➢ Reduces pressure on human personnel and increases system stability. |

| 17. | Deficit of honest and serious human resources. |

Immediate measures (0-12 months) Integrity and competence audit: ● What: external audit for key positions: network operators, dispatch, procurement, critical maintenance; ● Purpose: integrity + skills assessment, identification of operational risks and conflicts of interest; ● Indicator: % of positions audited; number of vulnerabilities identified and remediated. Policy on transparency and declaration of interests: ● What: public obligation (online platform) to declare interests, gifts, contracts for middle and senior management; ● Purpose: reducing the risk of corruption through public exposure and verification; ● Indicator: % of employees/office holders who made statements; number of conflicts resolved. Whistleblowers protection: ● What: secure, anonymous channel, legal protection and non-retaliation guarantees; ● Purpose: to encourage reporting of violations and ethics issues; ● Indicator: number of reports received and percentage remedied. Selectie publică și transparentă pentru posturi-cheie: ● Ce: concursuri cu comisii mixte (reprezentanți tehnici, societate civilă, experți independenți). Toate etapele publice; ● Indicator: % posturi-cheie ocupate prin proceduri publice; timp mediu de vacanță. Public and transparent selection for key positions: ● What: competitions with mixed committees (technical representatives, civil society, independent experts). All public stages; ● Indicator: % of key positions filled through public procedures; average vacation time. Medium-term measures (1–3 years) Compensation package & benefits for critical positions: ● What: competitive salaries + performance related bonuses (safety, network availability, efficiency), non-financial benefits (training, relocation); ● Purpose: retention of qualified personnel and reduction of exodus to the private/external sector; ● Indicator: annual turnover in critical positions; average tenure. National training and certification program: ● What: standardized curriculum (network operators, dispatch, cybersec), academies/simulation centers (damage simulation, security scenarios). Partnerships with universities and technical centers; ● Purpose: talent hub and skills upgrading; ● Indicator: no. of certified persons/year; reduction of operational errors. Performance management and clear sanctions: ● What: Transparent operational KPIs (Key Performance Indicator) (response time, availability, incidents) contractually linked to bonuses/sanctions. Clear disciplinary procedures, consistently applied; ● Indicator: % KPI achievement; number of sanctions applied (if applicable). Digitization for audit and traceability: ● What: Integrated ERP/SCADA systems with audit logging, access control, configuration change monitoring. Immutable logs for critical decisions (what, when, who); ● Purpose: operational fraud reduction and incident response capacity; ● Indicator: digital process coverage; anomaly detection time. Long-term measures (3–7 years) Reform of institutional governance: ● What: clarification of roles within energy entities; separation of powers (independent supervisory board, executive CEO), fixed mandate, strict revocation criteria; ● Purpose: managerial stability and protection against political interference; ● Indicator: frequency of changes at top level; perceived level of independence (surveys/polls). Organizational culture and ethics: ● What: permanent ethics programs, leadership, decision-making transparency; mandatory anti-corruption training; updated code of conduct; ● Purpose: lasting cultural change; ● Indicator: organizational climate survey results; ethical cases reported vs. resolved. International cooperation and expert mobility: ● What: exchange programs with EU operators/TSOs/DSOs, temporary secondments of foreign experts for know-how transfer; ● Purpose: technical acceleration and consolidation of good governance practices; ● Indicator: no. of programs/foreign experts, impact measurable in procedures/projects. Specific measures to combat "dishonest/unserious resources" (unsuitable employees, political influence): ● Incompatibility lists for sensitive positions (e.g.: direct commercial links with suppliers); ● Prohibition to contract/manage trade relations for those with proven direct links (determined period); ● Periodic rotation of personnel in sensitive positions to reduce the risk of local capture (job rotation); ● Psychological assessment & ethical testing upon employment for critical positions. |

| 18. | Deficit of political and legislative stability. |

Measures to increase energy stability and security Legislative stability and predictability: 1. Long-term legislative framework: ● Developing a 10-15 year national energy strategy, with clear objectives regarding the energy mix, emission reduction and investments; ● Protecting legislation from frequent changes through gradual transition mechanisms. 2. Harmonization with EU regulations: ● Implementation of the European directive on energy markets and renewable energy; ● Ensuring compliance with EU safety and environmental standards. 3. Transparency and predictability in tariffs: ● Establishing transparent mechanisms for setting energy tariffs; ● Avoiding discretionary subsidies that can destabilize the market. Strengthening the energy infrastructure: 1. Upgrading grids in order to increase efficiency and reduce losses; 2. Diversification of energy sources: ● Investments in renewables (solar, wind, hydro); ● Development of nuclear energy and energy storage. 3. Regional interconnections: ● Increasing connectivity with EU grids to ensure security of supply. Risk management and governance: 1. Creation of an independent energy regulatory authority, with control over political and economic decisions; 2. Continuity and crisis plans: ● Scenarios for interruptions in supply; ● Strategic fuel reserves and buffer production capacities. Stimulating private investment: 1. Public-private partnerships (PPPs) for infrastructure projects; 2. Tax incentives and guarantee of minimum returns for long-term investments; 3. Reducing bureaucracy and digitizing procedures for authorizations and licenses. |

| 19. | Precariousness and non-performance of energy equipment and appliances within The Power Transmission Grid |

Measures Infrastructure modernization: ● Replacing old transformers, switches and cables; ● Implementation of high-performance and overload-resistant equipment; ● Development of redundant transmission lines to prevent interruptions. Predictive maintenance and monitoring: ● SCADA and Smart Grid systems for real-time monitoring; ● Vibration, temperature and insulation analysis of equipment; ● Preventive and planned maintenance program, based on real functioning data. Advanced automation and protection: ● Implementation of intelligent protection relays; ● Automation of grid reconfiguration in case of fault; ● Automatic control systems for voltage and frequency regulation. Integration of renewable sources and demand flexibility: ● Development of energy storage systems (batteries, hydro pumps); ● Demand management to reduce overload in peak hours. Energy security and resilience plans: ● Periodic assessment of the PTG risks and vulnerabilities; ● Developing emergency plans and blackout simulations; ● Cyber protection for critical control and monitoring systems. |

| 20. | Lack of electricity – possible local, zonal, regional or national blackout. |

Technical measures: ● Modernization of power grids: ➢ Implementation of smart systems (smart grids) for real-time monitoring and control; ➢ Grid automation for rapid failure isolation. ● Increasing redundancy and diversifying sources: ➢ Connecting multiple energy sources (hydro, wind, photovoltaic, thermal power plants); ➢ Development of alternative transmission lines and backup systems. ● Energy storage: ➢ Large capacity batteries and pumped storage plants; ➢ Implementation of storage systems to balance consumption peaks. ● Maintenance and modernization: ➢ Periodic inspections and revisions of equipment and transmission lines; ➢ Replacing old or technologically outdated equipment. Operational measures: ● Emergency plans and civil protection: ➢ Rapid alerting systems and blackout response procedures; ➢ Evacuation or informing the population in real time. ● Demand management: ➢ Campaigns for voluntary reduction of consumption in critical periods; ➢ Implementation of dynamic pricing systems (higher prices during peak consumption). ● Testing crisis scenarios: ➢ Blackout simulation exercises at local, zonal and national level; ➢ Identifying vulnerabilities and correcting them. Long-term strategic measures: ● Diversification of the energy mix: ➢ Reducing dependence on a single source or imports; ➢ Investments in renewable energies and new technologies (hydrogen, advanced nuclear energy). ● Regional cooperation and interconnections: ➢ Connections with neighboring countries' power grids for mutual support; ➢ Possibility of rapid energy import in case of domestic deficit. ● Legislation and regulation: ➢ Standardization and strict security rules for network operators; ➢ Requirements for strategic energy reserves. Measures (recommendations) for consumers: ● Own backup systems (generators, UPS, solar batteries); ● Saving energy in times of crisis; ● Training of personnel and families for blackout situations. |

| Nr. Crt. |

IDENTIFIED INSTABILITY AND INSECURITY ELEMENTS | MEASURES TO INCREASE THE RESILIENCE OF THE NATIONAL POWER SYSTEM |

| 1. |

Technical and infrastructure factors: ● Outdated infrastructure (transmission and distribution grids, old power substations and power plants); ● Insufficient production capacities during peak periods; ● Imbalance between renewable and conventional energy sources; ● Lack of energy storage capacities. |

● Modernization of transmission and distribution grids (digitization, automation, intelligent control); ● Investments in storage capacities (batteries, hydroaccumulation, hydrogen); ● Development of decentralized production – microgrids, prosumers, energy communities; ● Increasing regional interconnectivity with the power systems of neighboring countries; ● Predictive maintenance and grid management systems based on AI/IoT. |

| 2. |

Economic and market factors: ● Volatility of energy and fuel prices; ● Dependence on imports (gas, oil, uranium, equipment); ● Lack of predictable investments and coherent support schemes. |

● Diversification of supply sources (liquefied natural gas, renewable energy, nuclear); ● Stimulating private investment through clear support mechanisms (contracts for difference, PPA schemes, feed-in tariffs); ● Creating a national energy resilience fund for rapid financing of crisis interventions; ● Promoting energy efficiency in industry, buildings and transport. |

| 3. |

Geopolitical, protection and security factors: ● Vulnerability to regional crises (conflicts, embargoes, sabotage); ● Cyber risks to critical infrastructure; ● Energy dependence on external actors. |

● Strengthening EU and NATO energy partnerships; ● Active participation in cross-border interconnection projects (high-capacity power substations and lines); ● Diversification of energy routes and suppliers; ● Active energy diplomacy for securing resources and technologies; ● Implementation of cybersecurity standards for critical energy infrastructure; ● Creation of a national energy incident response center (CERT-Energy); ● Periodic simulations and exercises for managing energy crisis situations; ● Strengthening the physical protection of strategic installations. |

| 4. |

Climate, environmental, social and sustainability factors: ● Increase of the frequency of extreme weather events; ● Reduced social acceptance for certain projects (e.g., gas, nuclear); ● The need for accelerated green transition imposed by EU policies. |

● Increasing the share of renewable energy in the national mix; ● Integrating environmental, social and governance criteria into energy strategies; ● Education and awareness programs on responsible energy consumption; ● Investments in green technologies – green hydrogen, carbon capture, advanced biomass. |

| 5. |

Institutional and governance factors: ● Institutional instability and poor communication between state institutions; ● Instability regarding the governance. |

● Developing a National Energy Resilience Strategy; ● Interinstitutional coordination between ministries, The National Authority for Energy Regulations, Transelectrica, operators and local authorities; ● Creating a system for real-time monitoring and reporting of energy risks and vulnerabilities; ● Periodic updating of the National Integrated Energy-Environment Plan according to risk scenarios; ● The resilience of the National Power System depends on: ➢ diversification; ➢ digitization; ➢ decarbonization; ➢ efficient institutional coordination. ● An integrated approach – technical, economic, geopolitical and ecological – is essential for ensuring long-term energy security. |

5. Energy Security Strategy for Resilience of the Romanian Power System – Developed Example

5.1. Executive Summary

5.2. Strategic Objectives

- Ensure secure, continuous, and affordable electricity supply under normal and crisis conditions;