1. Introduction

A composition of a positive integer

n is an ordered partition of

n or a sequence of positive integers that sum to

n. The summands are also called

parts and

n is the

weight of the composition. For example,

has four compositions:

and

. It is well known that there are

compositions of

n (see for example [

5,

7]).

Colored compositions are generalized compositions in which a part size may come in a prescribed number of types or colors, usually denoted by subscripts,

. In particular, an

n-color composition is a colored composition in which a part of size

m may come in

m colors:

,

1]. For example, there are eight

n-color compositions of 3, namely

The

n-color notion originated from a paper of Agarwal and Andrews [

2] that investigated combinatorial identities for “partitions with

n copies of

n”, that is,

n-color partitions. Subsequently Agarwal [

1] defined

n-color compositions and explored their enumeration and combinatorial properties. For instance, he proved that the number of

n-color compositions of a positive integer

is given by

, where the Fibonacci numbers are defined by

.

The

conjugate of a composition is given by the composition corresponding to the columns of its

zig-zag graph, read from left to right. For example, the zig-zag graph of

is shown in

Figure 1.

Thus the conjugate

, from

Figure 1, is

. Two further methods of obtaining

are mentioned below.

It appears that the

n-color compositions cannot all be conjugated like ordinary compositions! Brian Hopkins [

8] made a limited attempt by means of zig-zag graphs and concluded that only certain compositions with odd weights and parts not exceeding 3 may be conjugated. A year later, Collins et al. [

6] discussed the topic briefly using tilings of 1-by-

n boards with ternary sequences, and gave few instances. However, their technique was rather elusive, and no counting formula was provided. Alanazi et al. [

4] undertook a systematic investigation of the topic using

n-multicolor compositions with tilings of 1-by-

n boards and ternary sequences. They modeled their technique after an extension of MacMahon’s line graph conjugation method, and discovered a remarkably large set of conjugable

n-color compositions.

Theorem 1 (Alanazi et al. [

4]).

The number of conjugable n-color compositions of an integer is given by .

However, even in the latter model, a substantial number of objects still escaped conjugation. Note that for all .

Lastly, we refer to a significant 1997 paper of Agarwal and Balasubrananian [

3] where the conjugate of an

n-color partition

is defined as the

n-color partition

obtained by replacing each colored part

by

. The authors used this definition to establish an identity between “

n-color partitions where the weighted difference of each pair of parts is

” and “

n-color partitions such that in each pair of parts

(

)

b is the arithmetic mean of the subscripts

i and

j”, among other results.

One may apply this definition to n-color compositions and obtain the conjugate of every object! We will refer to this conjugation as color-complement or simply c-complement. For example, if , then the c-complement conjugate is given by .

Proposition 1. The number of c-complement self-conjugate n-color compositions of ν is given by .

Since

maps to

and

, self-conjugate parts are odd parts (

) with each part subscripted by its unique numerical index among increasing odd positive integers. The result then follows from the fact that compositions of

into odd parts are enumerated by

(see [

7,

11]). For example,

is c-complement self-conjugate.

Even though c-complement conjugation admits conjugation of every n-color composition C, the parts of C and remain rigidly the same, and it is not clear how can be found graphically. Nonetheless, the method holds independent interest and may be gainfully applied to any set of subscripted integer sequences.

This paper introduces a modified set of

n-color compositions in which every object has a conjugate in the classical tradition of Percy Alexander MacMahon (1854–1929) who pioneered the topic for ordinary compositions. Whereas standard

n-color compositions originated by extending to compositions the coloring scheme used for partitions (see [

1,

2]), our objects arise from coloring compositions directly. Such colored compositions share the essential property of

n-color compositions by requiring that a subscript associated with a part cannot exceed the part.

In

Section 2 we profile the new set of conjugable colored compositions with some immediate examples. Then in

Section 3 we give further details of three conjugation techniques gleaned from the conjugation of ordinary compositions.

Section 4 is devoted to the statement and proof of relvant enumeration formulas. Finally,

Section 5 contains additional enumeration results for objects with parts sizes bounded from below.

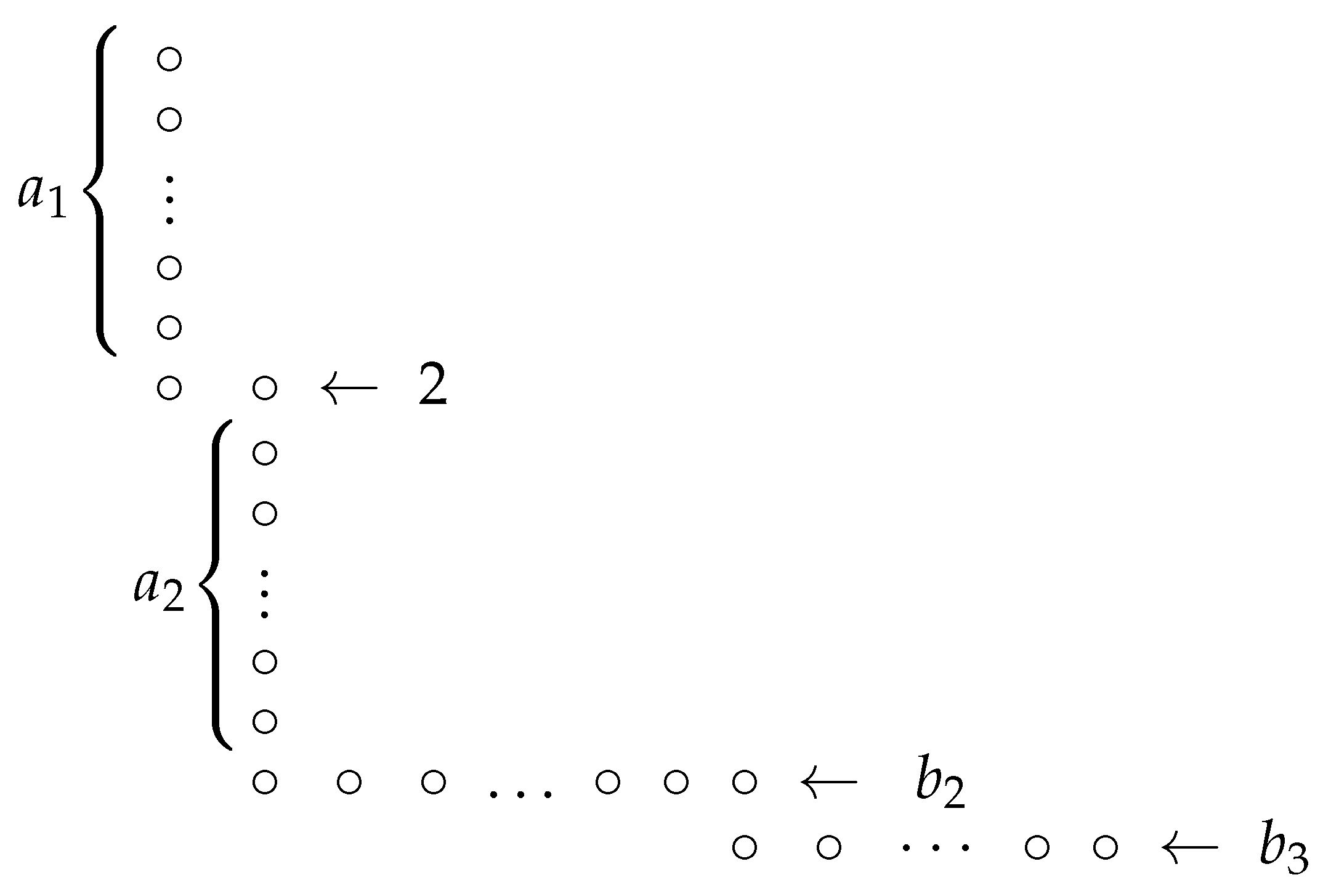

2. The n-Color Compositions of the Second Kind

It will be convenient to write compositions, symbolically, by representing a maximal string of 1’s of length

x by

, where two adjacent

big parts (i.e., parts

) are assumed to be separated by

. A general composition then has one of the following two forms:

where it is understood in each case that

C either ends in

or

for some

with

and

.

The first or last part of a composition C will also be referred to as a boundary part. Any other part of C is an interior part.

In defining our new set of colored compositions, we will be guided by the conjugation model of P. A. MacMahon for ordinary compositions, that is, every composition C has a unique conjugate that satisfies the following conditions:

(i) is obtainable from C via symbolic algebra;

(ii) is obtainable from the line graph of ; and

(iii) is obtainable from the zig-zag graph of C.

For example, besides the zig-zag graph technique shown earlier, one may use symbolic algebra and the line graph to obtain as fo llows.

Firstly, the symbolic algebra conjugation of

is given by

Thus an interior part

conjugates to

. We will also refer to

as the number of interior units of

m. Note that 2 conjugates to

and so has 0 interior units.

For example,

has the conjugate

For the line graph we use circular nodes separated by bars (instead of line segments separated by dots). Thus we get

By deleting the bars and placing bars inside the gaps that previously had none, we obtain

from which we read off the conjugate as

.

More details about these conjugation techniques may be found in [

9,

12].

We now propose an

n-color-type scheme that satisfies the three conjugation conditions. Our most significant departure from standard

n-color compositions is a negation of the assignment of the color 1 to each part 1 in every maximal string

. It is known that an ordinary composition generates as many

n-color compositions as the product of its parts (see, for example, [

13]). For example,

generates the following 6 objects.

Indeed any composition of the form

generates exactly 6

n-color compositions.

The coloring scheme proposed here accounts for the fact that the number of colors of a part-size m is dominated by m. But we treat a string of m ones, , , as the single part m with respect to color assignment. This is informed by the conjugation of standard compositions in which strings of 1’s translate into big parts.

This makes sense because a boundary string conjugates into the boundary part (which is entitled to colors) while an interior string conjugates into the interior part (which is entitled to colors). We see that an assignment of just the single color 1 to , independent of the size of x, is not symmetrical.

This color assignment is also supported by the natural fact that the parts of a composition occur as an ordered sequence. Thus in the proposed model, a colored part occurs in a composition if and only if a corresponding string , occurs in the ordinary support composition if and only if a string of x colored parts , actually occur in . Thus, for instance, if is colored 2 in a composition, these will appear as or in the symbolic form .

Another seemingly unusual assignment is that when 2 occurs as an interior part it has no color (or empty color) denoted by . This is justified by the naturally derived conjugation principle:

“a big part bears a positive color if and only if it can be obtained via a symbolic transformation of a string of 1’s with a positive color by conjugation".

It is clear that 2 does not fulfill this condition because it is obtained by transforming a zero string of ones

under conjugation (see the paragraph immediately following (

3)).

Suppose C is a composition of . Let and denote the respective sets of possible colors of a boundary and interior big part , and let and denote the sets of possible colors of a boundary and interior string of ones .

Definition 1. Let C be an ordinary composition of ν. A conjugable n-Color Composition is any colored composition of ν obtained by applying the following color assignments to the parts of C.

If C is a trivial composition, that is, , then each symbolic part admits ν colors:

;

Otherwise,

- (i)

;

- (ii)

;

- (iii)

;

- (iv)

.

As with ordinary compositions, the LG nodes of a boundary part (or boundary string of 1’s) are read from left to right on the left boundary, and from right to left on the right boundary.

Remark 1.

Note that when standard n-color compositions are defined with respect to sets of colors assigned to the parts of an ordinary composition, we have

Using the line graph, colors will be assigned to interior units of interior big parts. Thus an interior part

represented by

b nodes in a line graph is assigned a color only at one of the interior nodes, that is, at one of the 2nd to the

th nodes:

Secondly, a left boundary part

is assigned a color only at one of the first

nodes (similarly for a right boundary part):

On the other hand, it is clear that 2 with the representation has no interior unit. So an interior part 2 bears the color 0. However, a boundary part 2, with a representation of the form or , clearly has one colorable node, on the left or on the right, respectively. Consequently, in a nontrivial conjugable n-color composition 2 always takes the boundary form and the interior form .

Finally, we remark that a string of 1’s, being already units, may be assigned a color at any of its nodes in a line graph.

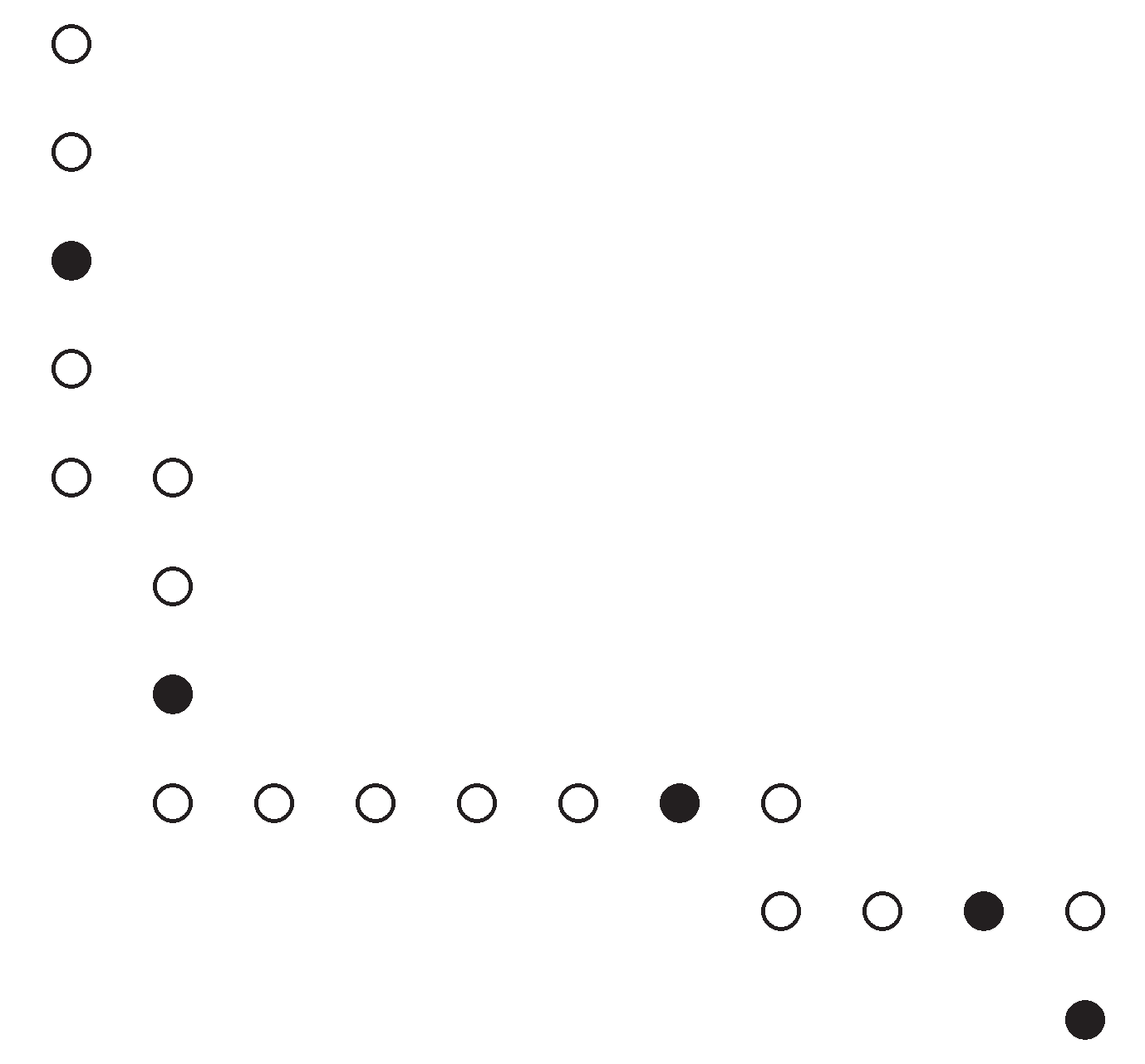

These facts may also be depicted using a zig-zag graph. For example, consider the composition

. From the zig-zag graph in

Figure 2, it is intuitively clear why any of the

(or

) nodes is colorable, why neither of the 2 interior nodes can be colored, why only the second to the

th nodes are colorable, and why only the last

nodes are colorable.

With these coloring rules observed, the conjugate of the resulting colored composition may be obtained by reading the diagram by columns, from left to right.

For example, the conjugable

n-color composition

has the following zigzag graph representation:

| |

∘ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

• |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

∘ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

∘ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

∘ |

∘ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

∘ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

∘ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

• |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

∘ |

∘ |

• |

∘ |

∘ |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

∘ |

∘ |

• |

The conjugate is now obtained by reading the zig-zag graph by columns to give

. The corresponding line graph of

is

The line graph of

is obtained by swapping gaps and bars as with ordinary compositions:

Finally, the symbolic algebra technique matches that of ordinary compositions as one may verify by ignoring the colors. Precise details are provided in the next section.

These new colored compositions should be known as n-color compositions of the second kind or simply M-color compositions.

We recap the properties satisfied by an M-color composition based on an ordinary support composition C, as follows. The number of parts of C is denoted by .

A maximal string of ones of length u comes in u colors, always.

If C consists of a single part b, then b comes in b colors.

If , the part comes in one color (namely 1 or 0).

If and is the first or last part of C, then b comes in colors.

If is an interior part of C, it comes in colors.

The number of M-color compositions of will be denoted by .

3. The Conjugation Involution

We now give a full explanation of the symbolic algebra technique. The trivial compositions conjugate as follows, for any

:

We next convert the ordinary composition

C in (

1) into a conjugable

n-color composition

by assigning colors to the parts in accordance with the definition:

Since the conjugate of

C is given by

(see (

3)), we analogously obtain

Alternatively, (showing the occurrence of 2) let

where the color sizes are subject to the restrictions in (5). Then the conjugate is

Note that the colors in both

and

satisfy the stipulations in the definition since they immediately agree with (5). For example, in

we have

for all

i, and

which gives

for

, and so forth. Secondly, the conjugation of an interior 2 to

and vice-versa are given by convention. Hence the conjugates in (

6) and (

7) are well-defined.

It is clear that one may similarly assign colors to the parts of the support composition (

2) and obtain analogous symbolic conjugates.

We remark that an

M-color composition of

cannot be self-conjugate, a fact inherited from ordinary (support) compositions (see [

12]).

Example 1.

Consider . Then

Alternatively, we may use the line graph and obtain

which, by placing division bars only in gaps which previously had none, leads to

from which the conjugate is again seen to be .

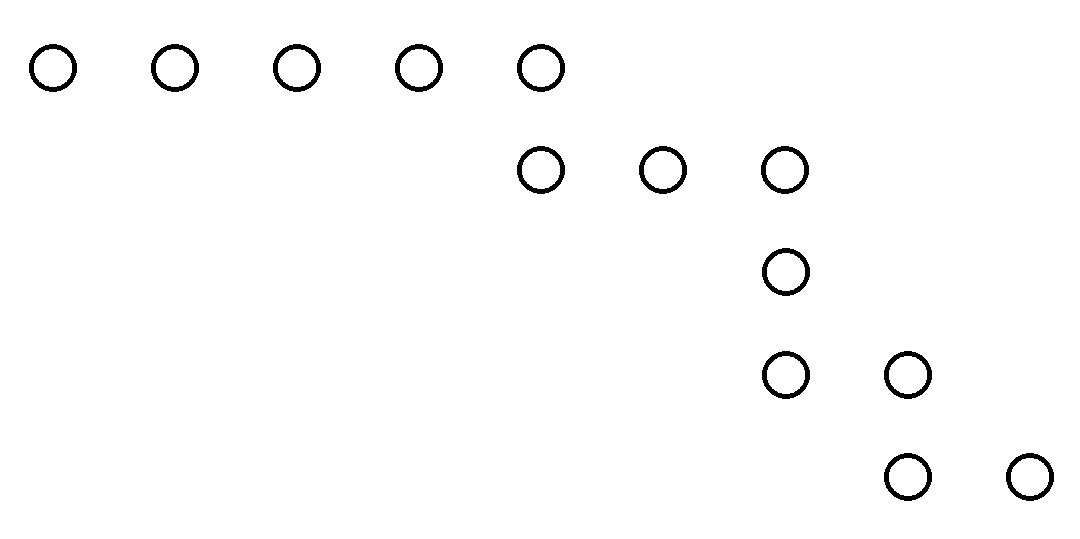

The final approach is to use the the zig-zag graph of as shown below, whence is obtained by reading the graph by columns.

Figure 3.

Zigzag graph of .

Figure 3.

Zigzag graph of .

Example 2.

If , then which enumerates the following objects (arranged in conjugate pairs):

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|