2.1. X-Ray Diffraction

In

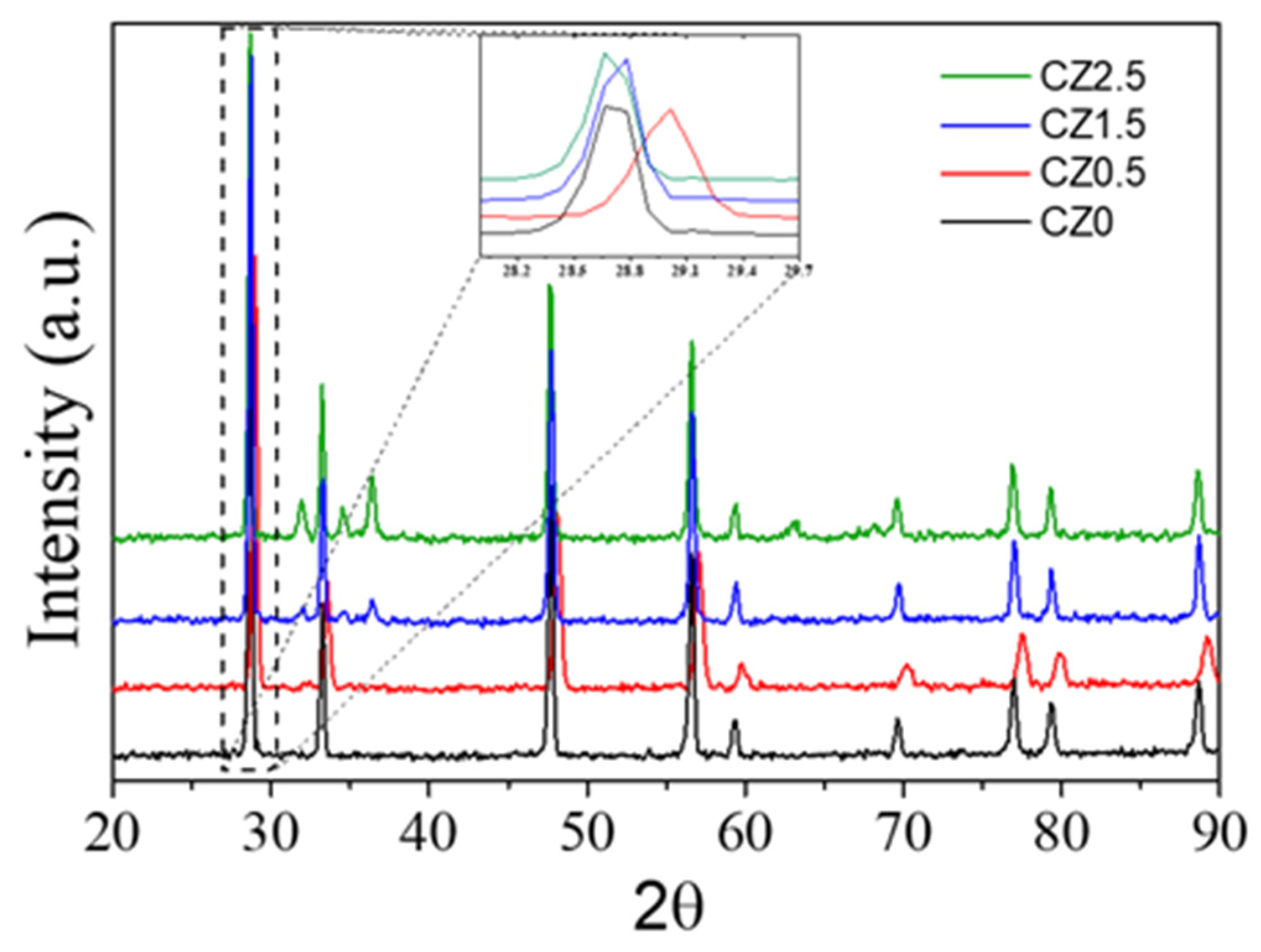

Figure 1 shows the diffraction patterns for the bare CZ0, CZ0.5, CZ1.5 and CZ2.5, the diffraction pattern of pure CeO

2 (CZO) shows well-defined peaks at 2θ ≈ 28.66°, 33.1°, 47.5°, 56.3°, 59.1°, 69.4°, 76.7°, and 79.1°, corresponding to the (111), (200), (220), (311), (222), (400), (331), and (420) planes, respectively, characteristic of the cubic fluorite structure of CeO

2 (JCPDS file No. 65-5923), [

39]. The high intensity and narrow width of the peaks indicate high crystallinity. A clear right-shift of the (111) peak is observed for the CZ0.5 sample (2θ = 28.90°) compared to CZO (2θ = 28.66°), as shown in the enlarged inset of

Figure 1. The calculated lattice parameter decreases from 5.3906 Å for CZO to 5.3467 Å for CZ0.5, representing a contraction of approximately 0.81%. This contraction is attributed to the partial substitution of Zn

2+ ions (0.74 Å, CN=6) for Ce

4+ (0.97 Å, CN=8) in the fluorite lattice, which generates oxygen vacancies for charge compensation and induces microstrain. This behavior is consistent with previous reports on Zn-doped CeO

2 systems, where peak shifts have been attributed to lattice contraction caused by the incorporation of smaller cations [Tulsi mediated green synthesis of zinc doped CeO2 for super capacitor and display applications]. For the CZ1.5 and CZ2.5 samples, the lattice parameter remains practically identical to that of CZO, indicating minimal Zn

2+ incorporation into the CeO

2 lattice at higher loadings. In contrast, these samples show additional reflections at 2θ ≈ 31.7°, 34.4°, and 36.2°, corresponding to the (100), (002), and (101) planes of the hexagonal wurtzite ZnO phase (JCPDS No. 36-1451), see

Figure 1. The appearance of these peaks confirms ZnO segregation at high ZnO contents. Consequently, at low Zn loadings, Zn

2+ is incorporated into the fluorite lattice, leading to a measurable contraction of the lattice parameter, whereas at higher loadings, ZnO crystallite segregation occurs, reducing the peak shift. These structural results are consistent with SEM/EDX analyses, which show an increase in Zn content with loading, and with BET data, where variations in surface area can be related to changes in particle stacking and the appearance of ZnO phases.

2.2. Nitrogen Physisorption

All samples exhibit type IV isotherms according to the IUPAC classification, characteristic of mesoporous materials with pore sizes in the 2–50 nm range, see

Figure 2. The incorporation of ZnO at 0.5, 1.5, and 2.5 wt% does not significantly modify the overall isotherm shape, indicating that the mesoporous nature of the CeO

2 matrix is preserved throughout the series. Regarding the hysteresis loop, all samples display an H3-type loop, commonly associated with slit-shaped pores. However, slight variations are observed: for CZ0.5, the slope of the adsorption branch in the high relative pressure region (P/P

0 > 0.8) is slightly steeper, suggesting a subtle increase in capillary condensation. In CZ1.5, this curvature becomes more pronounced, indicating greater mesopore accessibility. For CZ2.5, the behavior is very similar to CZ1.5, with only minor changes in slope and in the closure point of the loop. Although H3-type hysteresis is typically attributed to the stacking of plate-like particles, SEM images reveal semi-spherical particles without visible intraparticle porosity. This indicates that mesoporosity arises mainly from interparticle voids generated during particle packing, which behave as slit-like pores for N

2 adsorption.

Regarding the surface area calculated by the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller method, the values are reported in

Table 1. Compared to pure CeO

2, the BET surface area increased by approximately 3.5% for CZ0.5, reached a maximum enhancement of about 41% for CZ1.5, and decreased to ~15.5% for CZ2.5. This trend indicates that moderate ZnO incorporation optimizes the specific surface area, while excessive loading may lead to partial blockage. These changes are consistent with SEM observations, where variations in particle stacking are more evident at intermediate ZnO contents. With respect to pore volume and pore size obtained by the BJH method, the values are presented in

Table 1. The total pore volume remained in the range of 11–14 cm

3 g

−1, with a maximum increase of approximately 27% for CZ0.5 compared to pure CeO

2, indicating that ZnO incorporation does not significantly modify the total porosity. On the other hand, the average pore size showed a progressive decrease from 5.2 nm (CeO

2) to 4.1 nm (CZ2.5), representing a reduction of about 21%. This decrease indicates that at higher ZnO contents, the interparticle voids tend to become smaller due to changes in particle stacking, an effect also observed in the SEM analysis.

As to determination of the specific area by nitrogen adsorption desorption in the

Table 1 an typical isotherm type III its show by all catalysts further the absence of hysteresis is also observed due to size of pores which are in range of 2 to 6 nm, also an increase in the values surface area its observed as ZnO is increases, being the CZ1.5 catalyst the material with the largest specific area however an decrease its observed in the CZ2.5 material, it can be due to the particles of ZnO cover the surface of CeO

2 clogging the pores, also the crystal size is similar for the catalysts. By other sizes, values of similar band gap are observed by materials with ZnO, further a decrease in the value is observed with increase of load of ZnO, this behavior gives us the idea of the interaction between the two materials since less energy is required for the formation of the electro-hole pair.

2.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy

SEM images of the CeO

2 sample (CZ0,

Figure 3a) show aggregates of semi-spherical nanoparticles with sizes in the range of ~50–150 nm, forming densely stacked particle clusters. The surface appears relatively homogeneous, without visible intraparticle porosity, suggesting that the mesoporosity detected by N

2 physisorption originates mainly from voids between stacked particles.

The corresponding EDX spectrum (

Figure 3a) confirms the presence of Ce and O as the main elements, with no detectable Zn signal, as expected for the reference material. For the CZO0.5 sample (

Figure 3b), the morphology remains like pure CeO

2, with semi-spherical particles forming compact stacks. A slight tendency towards tighter particle stacking is observed, which could reduce the size of some interparticle voids. The EDX analysis reveals Zn peaks of low intensity, consistent with the nominal 0.5 wt% ZnO loading. In the CZO1.5 sample (

Figure 3c), the particles maintain a semi-spherical shape but appear more uniform in size distribution, and the stacking seems less compact in certain regions, creating slightly larger interparticle voids. The EDX spectrum shows a higher Zn signal compared to CZ0.5, confirming the increased ZnO content. The CZ2.5 sample (

Figure 3d) exhibits clusters of semi-spherical nanoparticles with a more irregular stacking arrangement, where some regions show open voids between aggregates. This loose stacking could facilitate the accessibility of mesopores formed between particles. The EDX spectrum displays the most intense Zn peaks among the series, in line with the highest nominal ZnO loading. ZnO incorporation does not significantly alter the particle shape but slightly influences particle stacking and the size of the voids between them. EDX analysis corroborates the expected chemical composition, with Zn signal intensity increasing proportionally to the nominal loading.

2.3. XPS Spectra of the Catalysts

The characterization by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed on a spectrophotometer XPS microprobe PHI 5000 VersaProbe-II. with a monochrome of Al Ka (hn=1486.7 eV). The spectra were calibrated with respect C 1s to 284.5 eV.

To obtain information about the chemical states, stoichiometry, and surface species of the photocatalysts, the XPS technique was used.

Figure 4 shows the survey spectra of the photocatalysts and confirms that they consist of the elements Ce, Zn, O, and C. No other elements were observed that could be correlated with impurities due to the precursors or the materials’ preparation method.

The deconvolution of the high-resolution XPS spectrum of core level (spin orbit coupling) of Ce 3d from the reference CZ0,in this is observed the doublet of the spin orbit coupling of Ce 3d

5/2 and Ce 3d

3/2 in wich 4 and 6 peaks were obtained, these are attributed to Ce

3+ y Ce

4+, respectively (see

Figure 5). The binding energy (BE) that corresponds to Ce

3+ are localized in 880.64 eV (Ce 3d

5/2, v

0), 899.24 eV (Ce 3d

3/2, u

0), 885.13 eV (v’) y 903.73 (u’). For Ce

4+ its BE are localized in 882.20 eV (Ce 3d

5/2, v), 888.28 eV (v’’), 897.82 eV (v’’’), 900.80 eV (Ce 3d

3/2, u), 906.88 eV (u’’) and 916.35 eV (u’’’)

The results obteined to according to the adjustmen and deconvolution of the spectrum of higt resolution of Ce 3d (CZ0), are similar to the has been reported in the literature, mention that the associated BE to v’’, v’’’, u’’ and u’’’ correspond to the satellites shake-up of the levels of the del núcleo de Ce

4+ 3d

5/2 y 3d

3/2. Las BE de los satelites shake up correspondientes a Ce

3+ 3d5/2 y 3d3/2 son v’ y u. The spin-orbit shift of Ce 3d

5/2 and 3d

3/2 is of 18.60 eV, for both species of Ce

3+ and Ce

4+. The reason for Ce

3+ content in CZ0, it was determined using the procedure and expression Ce

3+/(Ce

3+ + Ce

4+) as reported in the literature [

3,

39], the value obtained of Ce

3+ by CZ0 was 21.8%.

The relative reason of the Ce

3+ specie was calculated in the same way using the previous expression for CZn0.5, CZn1.5 y CZ2.5; the value obtained were: 22%, 20% and 17.2%. The incorporation of Zn Oto CeO

2 modifies the Ce

3+ ratio below 1% of ZnO. Howhever, by the material of 2.5% of ZnO, A new peak can be observed that can be associated with cerium nanoparticles with a non-stoichimetric composition of CeO

2-y, it’s correlated to the presence of oxygen vacancies and the formation of Ce

2O

3 due to the incorporation of ZnO [

3].

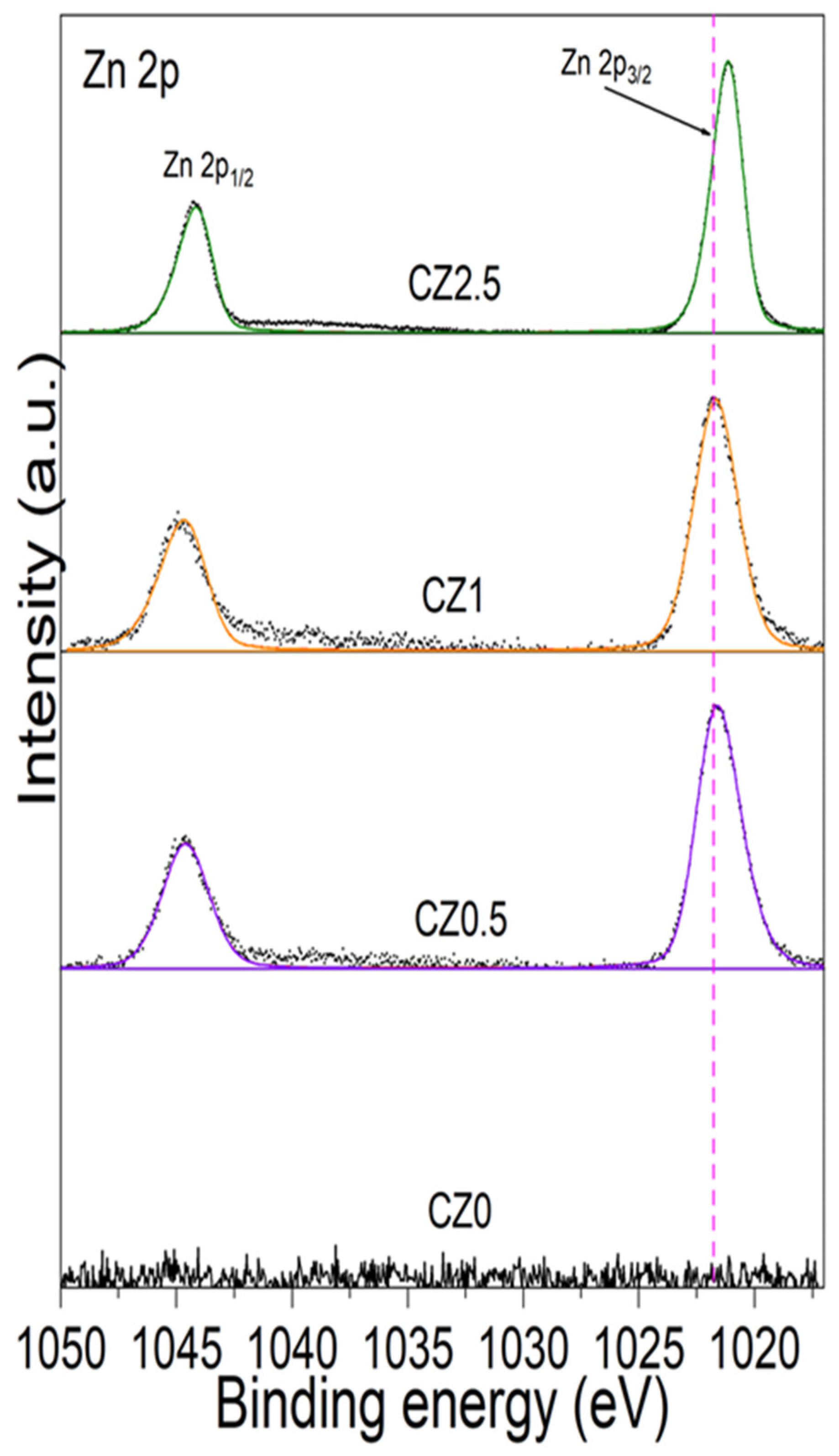

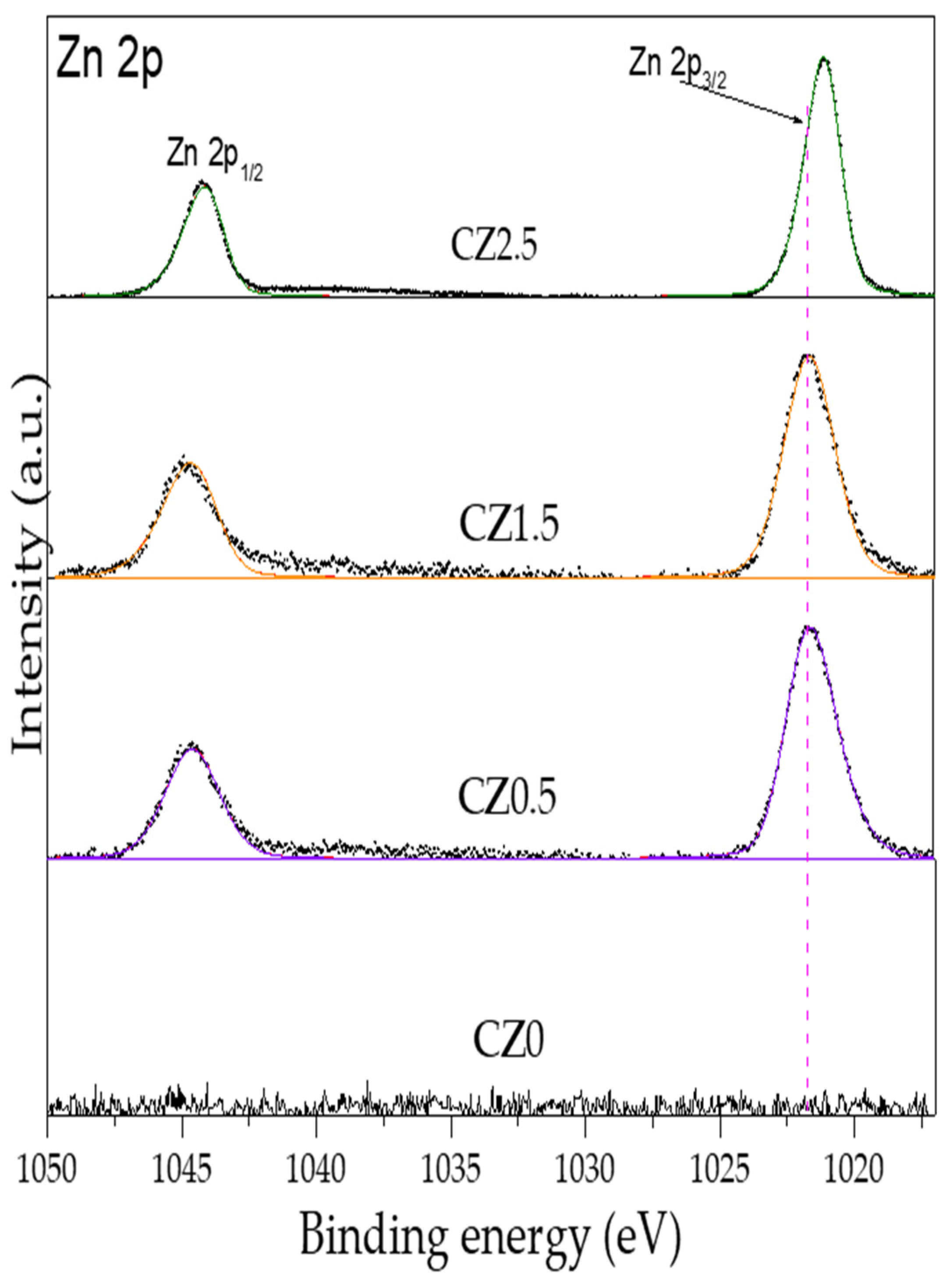

According to what has been reported in the literature by the spin-orbit coupling of Zn 2p

3/2 and Zn 2p

1/2 present a BE of 1021.7 and 1044.7 eV, correspond to Zn

2+ in the crystal lattice of ZnO [Ceramics International 2019]. In

Figure 6, high resolution spectra of Zn are shown by Zn 2p

3/2 and 2p

1/2 by the catalysts CZ0.5, CZ1.5 y CZ2.5, Subsequently, the afore mentioned BEs are taken as a reference for our analysis.

Figure 6 shows the dotted line associated with the BE as a ZnO reference (1021.7 eV) which corresponds to Zn

2+ in the structural network of ZnO. In the incorporation of Zinc to CeO

2 shows a slight shift at low energy by CZ05 (1021.60 eV), CZ1.5 (1021.67 eV) and for CZ2.5 the displacement is much greater (1021.15 eV). The low energy shift indicates that zinc is within the CeO

2 crystalline structure, causing the generation of oxygen vacancies and forming a heterojunction between both crystalline phases (CeO

2 and ZnO) in addition, in samples CZ0 and CZ2.5 CeO

2-y However, for sample CZ1.5 the opposite occurs, zinc is partially in the structure and outside the CeO

2 structure, since there is no significant change in its BE and the displacement of coupling spin-orbit of Zn 2p

2/3 and 2p

1/2 is 23 eV.

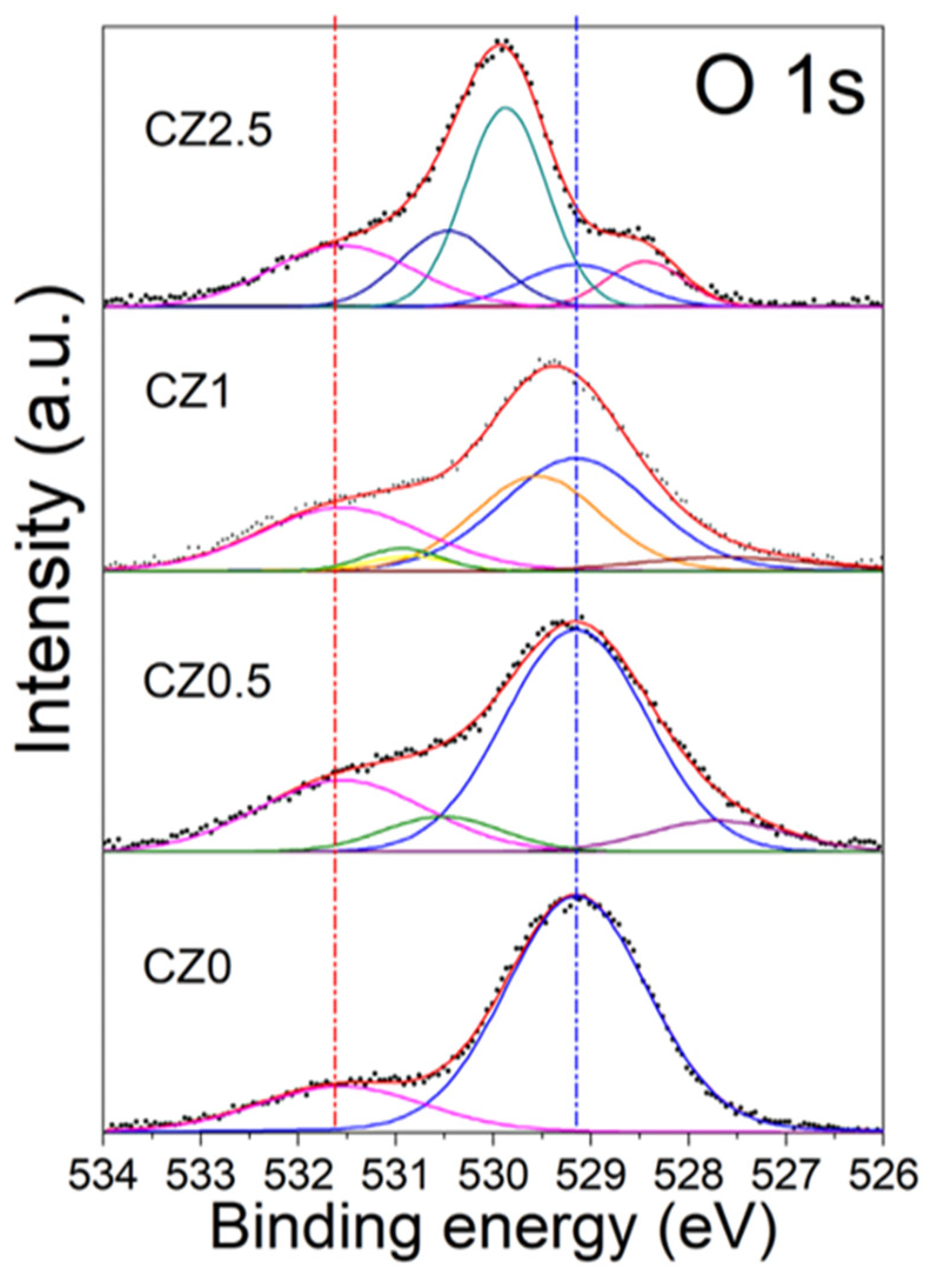

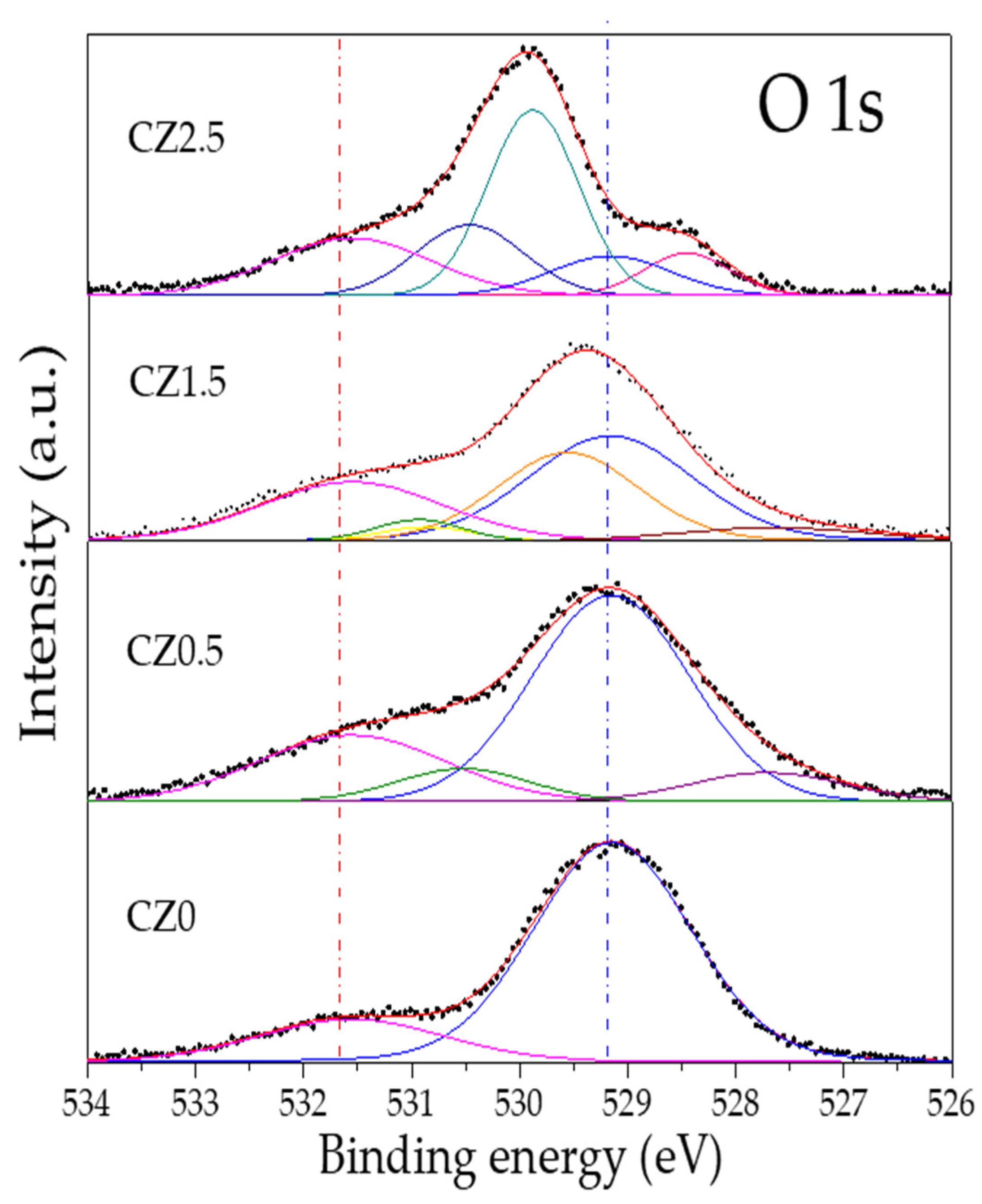

By other size the high-resolution O 1s spectrum of the different catalysts according to our analysis can be observed in

Figure 7. In the CZ0 sample, two peaks can be observed that are located at 529.15 eV and 531.55 eV, which are associated with oxygen in the structural network (blue dotted line) with 81.3% and with oxygen on the surface (red dotted line) as OH ions with 18.7% in CeO

2 [Ceramics international 2019]. The Zinc incorporation in the framework of CeO

2 generates new peaks (

Table 2 and

Figure 7).

The new oxygen species observed in CZ0.5 are located at 527.70 and 530.52 eV and can be assigned to the Zn-O-Ce interaction, which generates the vacancies, and Zn-OH-Ce on the surface. In the CZ1.5 material, it can be observed that there is a low-energy shift in the peaks associated with Zn-O-Ce and Zn-OH-Ce, and a peak located at 530.86 eV is generated, which can be associated with Zn-OH, since, as mentioned above, zinc is not completely contained in the CeO2 crystal structure. Finally, in CZ2.5, it is observed that there is a high energy shift which is associated with the strong interaction (heterojunction) of the species and substitution of Zn in the CeO2 network (Zn-O-Ce and Zn-OH-Ce) in addition to the formation of a non-stoichiometric species of CeO2-y, which is located at 529.87 eV.

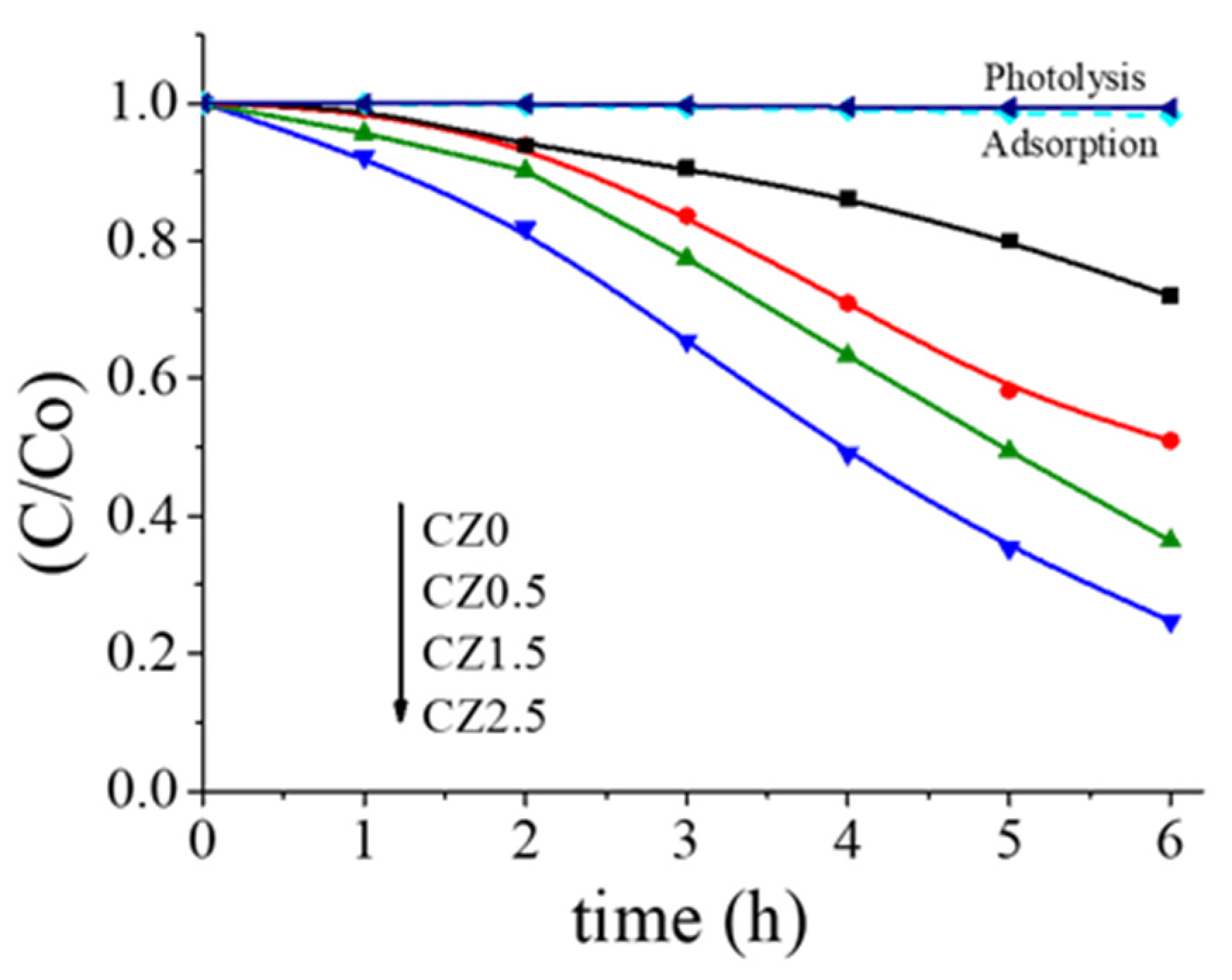

2.5. Study of Photodegradation Catalytic of 40ppm of 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid

Figure 9 shows the relative degradation rate of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) using CeO2–ZnO catalysts. A clear increase in photocatalytic activity is observed as the ZnO loading increases. Among the catalysts evaluated, CZ1.5 exhibits the best performance, achieving approximately 80% degradation of 2,4-D after 6 h, while pure CeO2 (CZ0) shows the lowest activity. This trend is confirmed by total organic carbon (TOC) analysis, which reveals mineralization degrees of 74%, 50%, 39%, and 28% for CZ1.5, CZ2.5, CZ0.5, and CZ0, respectively. It is noteworthy that the activity of CZ1.5 is approximately twice that of CZ0, highlighting the beneficial effect of ZnO in the photocatalytic process.

Figure 3.

SEM/EDX analysis of catalysts CZ0, CZ0.5, CZ1.5 and CZ2.5.

Figure 3.

SEM/EDX analysis of catalysts CZ0, CZ0.5, CZ1.5 and CZ2.5.

2.4. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy

By the other size the characterization by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed on a spectrophotometer XPS microprobe PHI 5000 VersaProbe-II. with a monochrome of Al Ka (hn=1486.7 eV). The spectra were calibrated with respect C 1s to 284.5 eV. To obtain information about the chemical states, stoichiometry, and surface species of the photocatalysts, the XPS technique was used. Figure 4 shows the survey spectra of the photocatalysts and confirms that they consist of the elements Ce, Zn, O, and C. No other elements were observed that could be correlated with impurities due to the precursors or the materials’ preparation method.

Figure 4.

Spectra survey XPS of photocatalysts CZ0, CZ0.5, CZ1.5, CZ2.5.

Figure 4.

Spectra survey XPS of photocatalysts CZ0, CZ0.5, CZ1.5, CZ2.5.

The deconvolution of the high-resolution XPS spectrum of core level (spin orbit coupling) of Ce 3d from the reference CZ0, in this is observed the doublet of the spin orbit coupling of Ce 3d

5/2 and Ce 3d

3/2 in wich 4 and 6 peaks were obtained, these are attributed to Ce

3+ y Ce

4+, respectively (ver Figure 5). The binding energy (BE) that corresponds to Ce

3+ are localized in 880.64 eV (Ce 3d

5/2, v

0), 899.24 eV (Ce 3d

3/2, u

0), 885.13 eV (v’) y 903.73 (u’). For Ce

4+ its BE are localized in 882.20 eV (Ce 3d

5/2, v), 888.28 eV (v’’), 897.82 eV (v’’’), 900.80 eV (Ce 3d

3/2, u), 906.88 eV (u’’) and 916.35 eV (u’’’). The results obteined to according to the adjustmen and deconvolution of the spectrum of higt resolution of Ce 3d (CZ0), are similar to the has been reported in the literature, Lazaro et.al, mention that the associated BE to v’’, v’’’, u’’ and u’’’ correspond to the satellites shake-up of the levels of the nucle of Ce

4+ 3d

5/2 y 3d

3/2. The BE of the satellites shake up correspondent to Ce

3+ 3d5/2 y 3d3/2 son v’ y u. The spin-orbit shift of Ce 3d

5/2 and 3d

3/2 is of 18.60 eV, for both species of Ce

3+ and Ce

4+. The reazon for Ce

3+ content in CZ0, it was determined using the procedure and expression Ce

3+/(Ce

3+ + Ce

4+) as reported in the literature [

3,

39], the value obtained of Ce

3+ by CZ0 was 21.8%.

The relative reason of the Ce3+ species was calculated in the same way using the previous expression for CZn0.5, CZn1.5 y CZ2.5; the value obtained were: 22%, 20% and 17.2%. The incorporation of Zn Oto CeO2 modifies the Ce3+ ratio below 1% of ZnO. Howhever, by the material of 2.5% of ZnO, A new peak can be observed that can be associated with cerium nanoparticles with a non-stoichimetric composition of CeO2-y, this is correlated to the presence of oxygen vacancies and the formation of Ce2O3 due to the incorporation of ZnO [2015 referencia]. According to what has been reported in the literature by the spin-orbit coupling of Zn 2p3/2 and Zn 2p1/2 present a BE of 1021.7 and 1044.7 eV, correspond to Zn2+ in the crystal lattice of ZnO [Ceramics International 2019]. In Figure 6, high resolution spectra of Zn are shown by Zn 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 by the catalysts CZ0.5, CZ1.5 y CZ2.5, Subsequently, the BEs are taken as a reference for our analysis.

Figure 5.

High-resolution spin-orbit doublet spectra of Ce 3d (Ce 3d5/2 and Ce 3d3/2) by the photocatalysts CZ0, CZ0.5, CZ1 y CZ2.5This is a figure. Schemes follow the same formatting.

Figure 5.

High-resolution spin-orbit doublet spectra of Ce 3d (Ce 3d5/2 and Ce 3d3/2) by the photocatalysts CZ0, CZ0.5, CZ1 y CZ2.5This is a figure. Schemes follow the same formatting.

Figure 6.

High-resolution spectra for Zn2p of the catalysts CZ0, CZ0.5, CZ1.5 y CZ2.5.

Figure 6.

High-resolution spectra for Zn2p of the catalysts CZ0, CZ0.5, CZ1.5 y CZ2.5.

Figure 6 shows the dotted line associated with the BE as a ZnO reference (1021.7 eV) which corresponds to Zn2+ in the structural network of ZnO. In the incorporation of Zinc to CeO2 shows a slight shift at low energy by CZ05 (1021.60 eV), CZ1.5 (1021.67 eV) and for CZ2.5 the displacement is much greater (1021.15 eV). The low energy shift indicates that zinc is within the CeO2 crystalline structure, causing the generation of oxygen vacancies and forming a heterojunction between both crystalline phases (CeO2 and ZnO) in addition, in samples CZ0 and CZ2.5 CeO2-y However, for sample CZ1.5 the opposite occurs, zinc is partially in the structure and outside the CeO2 structure, since there is no significant change in its BE and the displacement of coupling spin-orbit of Zn 2p2/3 and 2p1/2 is 23 eV.

By other size the high-resolution O 1s spectrum of the different catalysts according to our analysis can be observed in Figure 7. In the CZ0 sample, two peaks can be observed that are located at 529.15 eV and 531.55 eV, which are associated with oxygen in the structural network (blue dotted line) with 81.3% and with oxygen on the surface (red dotted line) as OH ions with 18.7% in CeO2 [Ceramics international 2019]. The Zinc incorporation in the framework of CeO2 generates new peaks (Table 2 and Figure 7).

Figure 7.

High resolution O 1s spectrum of catalysts CZ0, CZ0.5, CZ1.5 and CZ2.5.

Figure 7.

High resolution O 1s spectrum of catalysts CZ0, CZ0.5, CZ1.5 and CZ2.5.

Table 2.

Binding energies O 1s of the different samples prepared by impregnation.

Table 2.

Binding energies O 1s of the different samples prepared by impregnation.

| CZ0 |

CZ0.5 |

CZ1.5 |

CZ2.5 |

| O 1s |

O 1s |

O 1s |

O 1s |

Energy

(eV) |

Concen. Relative

(%) |

Energy

(eV) |

Concen

Relative

(%) |

Energy

(eV) |

Concen.

Relative

(%) |

Energy

(eV) |

Concen. Relative

(%) |

| 529.15 |

81.3 |

527.70 |

8.2 |

527.63 |

5.4 |

528.45 |

8.7 |

| 531.55 |

18.7 |

529.15 |

60.8 |

529.15 |

39.1 |

529.15 |

11.3 |

| |

|

530.52 |

8 |

529.55 |

28.3 |

529.87 |

40.1 |

| |

|

531.55 |

23 |

530.86 |

2.8 |

530.46 |

18.1 |

| |

|

|

|

531.55 |

24.4 |

531.55 |

21.8 |

The new oxygen species observed in CZ0.5 are located at 527.70 and 530.52 eV and can be assigned to the Zn-O-Ce interaction, which generates the vacancies, and Zn-OH-Ce on the surface. In the CZ1.5 material, it can be observed that there is a low-energy shift in the peaks associated with Zn-O-Ce and Zn-OH-Ce, and a peak located at 530.86 eV is generated, which can be associated with Zn-OH, since, as mentioned above, zinc is not completely contained in the CeO2 crystal structure. Finally, in CZ2.5 it is observed that there is a high energy shift which is associated with the strong interaction (heterojunction) of the species and substitution of Zn in the CeO2 network (Zn-O-Ce and Zn-OH-Ce) in addition to the formation of a non-stoichiometric species of CeO2-y, which is located at 529.87 eV.

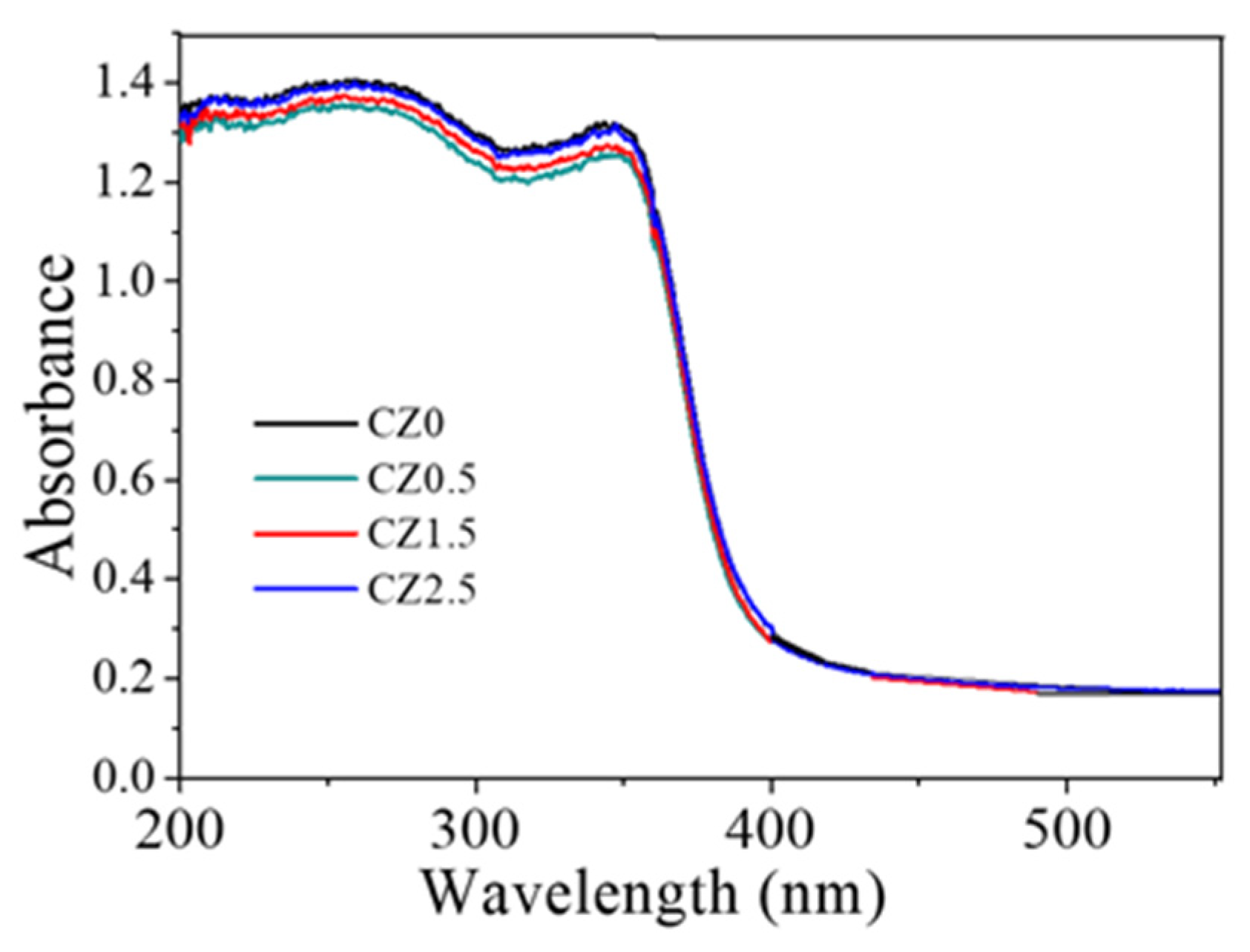

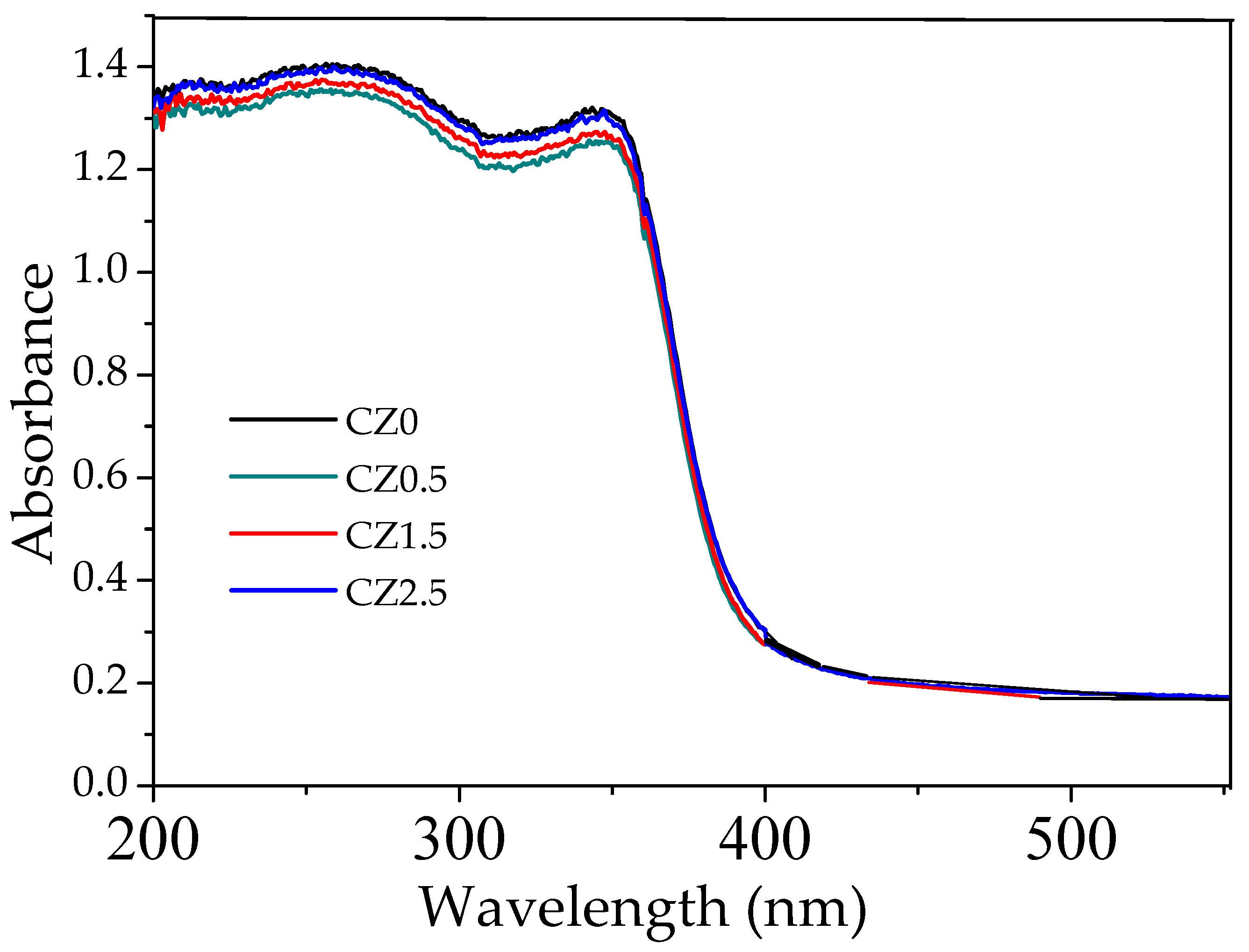

2.5. UV Spectra of Catalysts CZ0, CZ0.5, CZ1.5, CZ2.5

In the reference sample CZ0, the UV–Vis spectrum exhibits an absorption edge near 380 nm, with an estimated band gap of ~3.13 eV (

Table 1), a value consistent with that reported for CeO

2 pure with a cubic fluorite structure [Nanostructured CeO

2 photocatalysts: Optimizing surface chemistry, morphology, and visible-light absorption]. This result confirms that the employed synthesis method does not significantly alter the intrinsic electronic structure of the base material, see Figure 8.

Figure 8.

UV spectra for catalysts CZ0, CZ0.5, CZ1.5 and CZ2.5.

Figure 8.

UV spectra for catalysts CZ0, CZ0.5, CZ1.5 and CZ2.5.

Upon incorporating ZnO, the spectra of all samples display similar absorption edges, with no significant changes in Eg, indicating that the partial substitution of Ce4+ by Zn2+ and the formation of heterojunctions do not substantially affect the fundamental transition of the semiconductors. Therefore, the observed improvement in photocatalytic activity cannot be attributed to a reduction in Eg, but rather to structural and interfacial factors such as the increase in oxygen vacancies, the presence of Ce3+ species, and the efficient charge separation in a possible S-scheme heterojunction.

2.6. Study of Photodegradation Catalytic of 40ppm oc Acid 2,4 Dichlorophenoxyacetic

Figure 9 shows the relative degradation rate of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) using CeO2–ZnO catalysts, in addition the photolysis and adsorption reactions are observed. A clear increase in photocatalytic activity is observed as the ZnO loading increases. Among the catalysts evaluated, CZ1.5 exhibits the best performance, achieving approximately 80% degradation of 2,4-D after 6 h, while pure CeO2 (CZ0) shows the lowest activity. This trend is confirmed by total organic carbon (TOC) analysis, which reveals mineralization degrees of 74%, 50%, 39%, and 28% for CZ1.5, CZ2.5, CZ0.5, and CZ0, respectively. It is noteworthy that the activity of CZ1.5 is approximately twice that of CZ0, highlighting the beneficial effect of ZnO in the photocatalytic process. Furthermore Table 2 shows the band gap values, as well as the results of the kinetic calculation of the photodegradation reaction of 2,4-d acid, and the TOC values.

Figure 9.

Graph of relative degradation rate of 40ppm of 2,4-D.

Figure 9.

Graph of relative degradation rate of 40ppm of 2,4-D.

Table 2.

Shows the band Gap values, kapp values, half lifetime and %TOC degradation.

Table 2.

Shows the band Gap values, kapp values, half lifetime and %TOC degradation.

| Catalysts |

Band gap

(eV) |

Kapp |

t1/2

h |

TOC % Degradation |

| CZ0 |

3.18 |

0.047 |

14.6 |

28 |

| CZ0.5 |

3.44 |

0.085 |

8.1 |

39 |

| CZ1.5 |

3.35 |

0.24 |

3.8 |

74 |

| CZ2.5 |

3.30 |

0.11 |

6.0 |

50 |

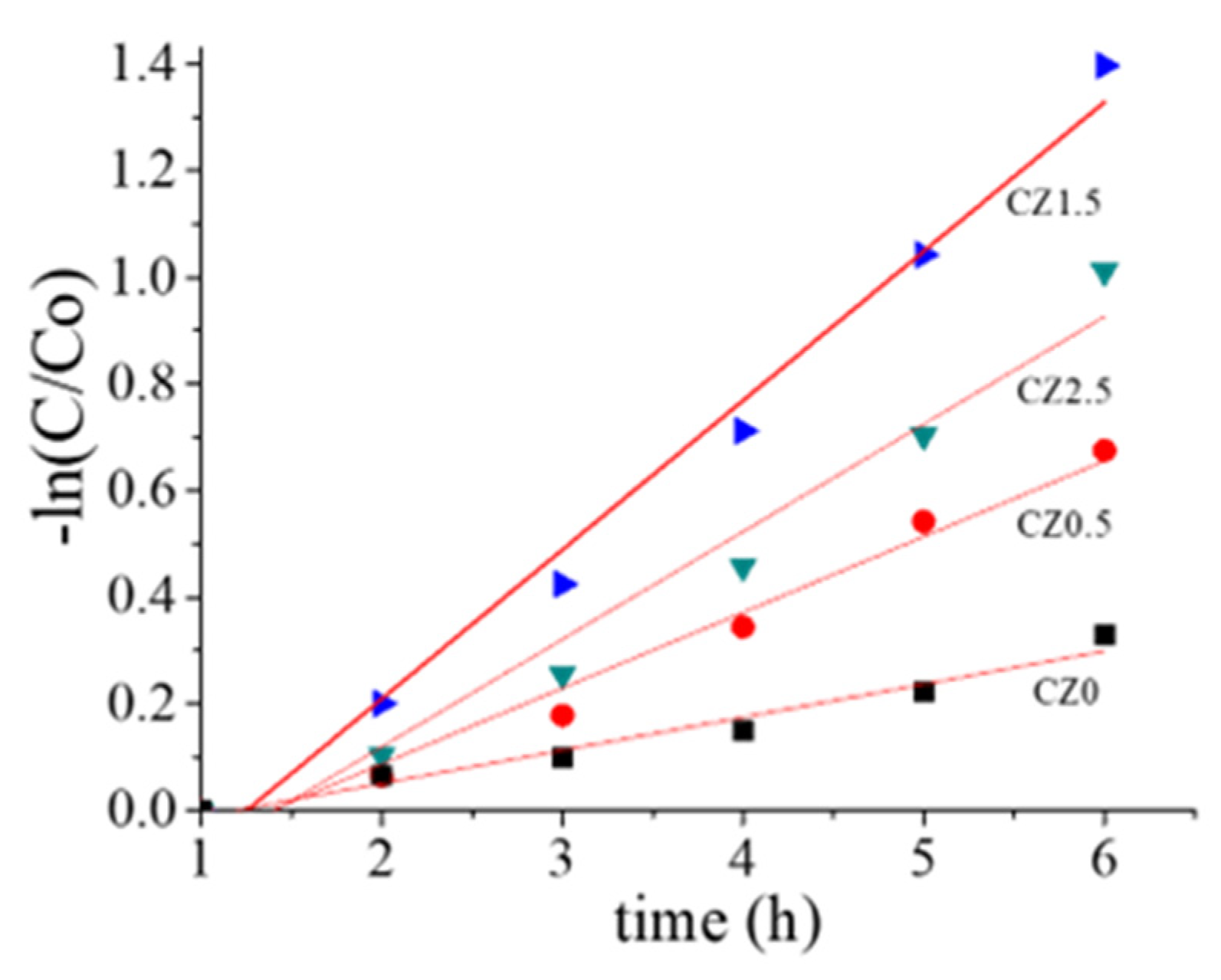

The kinetic data (Figure 10) fits well to a pseudo-first-order model, indicating that the reaction rate is mainly governed by the availability of active surface sites and the efficiency of photon absorption. The outstanding performance of CZ1.5 can be attributed to an optimal balance between ZnO content, surface area, and the formation of heterojunctions, which promote efficient charge separation and minimize electron–hole recombination.

Figure 10.

Kinetic graph of degradation of 40ppm of 2,4-D.

Figure 10.

Kinetic graph of degradation of 40ppm of 2,4-D.

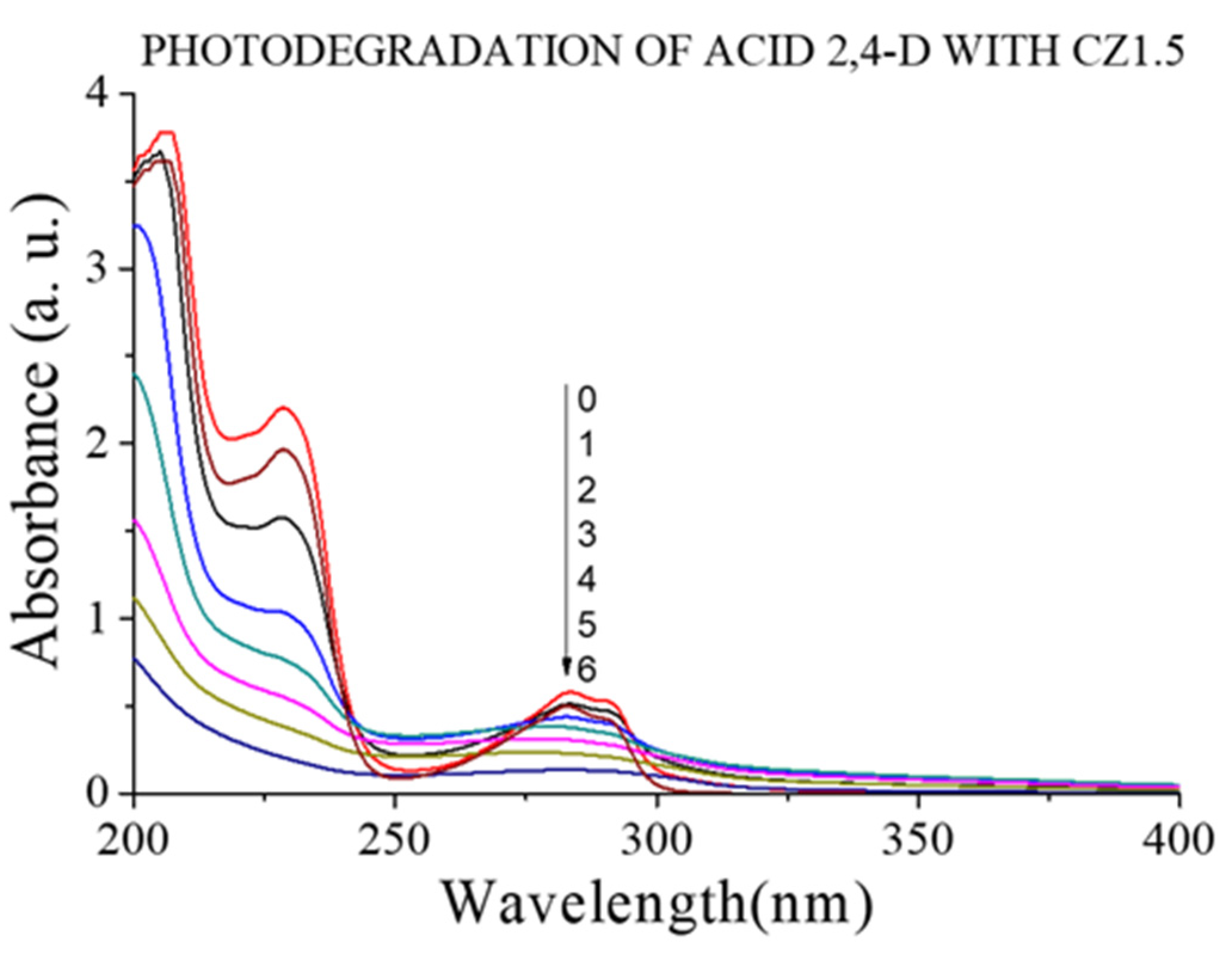

Figure 11 shows the photodegradation spectrum for the CZ1.5 catalyst. In this figure, it can be observed that the catalyst not only degrades the representative part of 2,4-D, but also the degradation of the aromatic part in the range of approximately 200 to 250 nm.

Figure 11.

UV spectra of the 2,4-D photodegradation with CZ1.5 catalysts.

Figure 11.

UV spectra of the 2,4-D photodegradation with CZ1.5 catalysts.

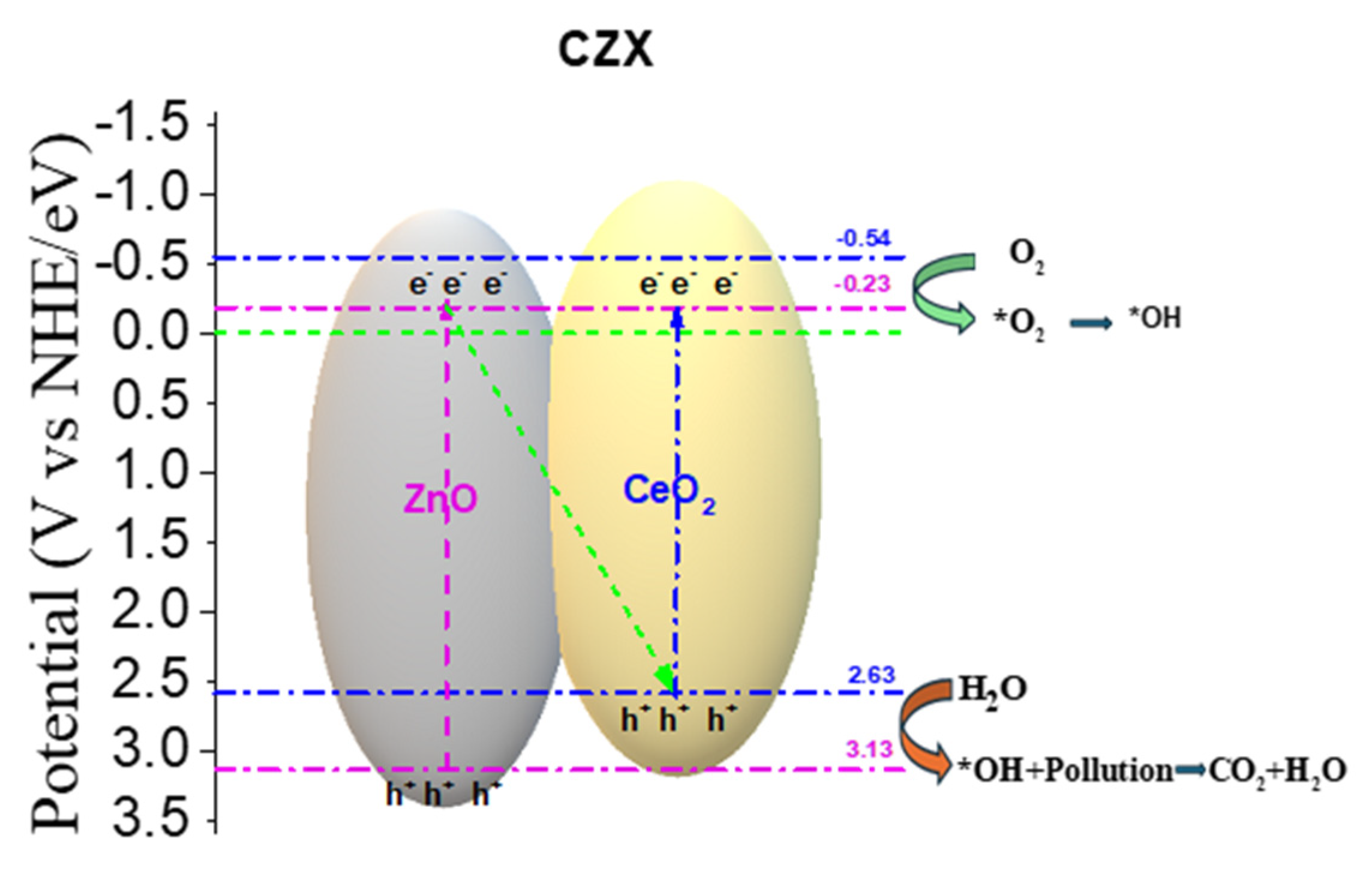

The band edge values obtained by XPS for ZnO and CeO2 (Figure 5 and Figure 6) allow the construction of the actual energy diagram of the system, which shows that the conduction band (CB) of ZnO is located at a more negative potential (−0.23 eV vs. NHE) than that of CeO2 (−0.54 eV), while the valence band (VB) of CeO2 (2.63 eV) is less positive than that of ZnO (3.13 eV). This configuration suggests that, under UV irradiation, both semiconductors generate electron–hole (e−/h+) pairs independently.

In a conventional type-II heterojunction, electrons from the CB of the semiconductor with the more negative CB (ZnO) would migrate to the CB of the semiconductor with the more positive CB (CeO

2), while holes from the VB of CeO

2 would move to the VB of ZnO. However, this mechanism leads to the accumulation of electrons and holes with less extreme redox potential, thereby reducing their oxidative and reductive capabilities [

37].

In contrast, the analysis of our structural (XRD) and surface chemistry (XPS) results, along with the high efficiency in the generation of •OH and O2•− inferred from the photocatalytic activity, indicates that the CeO2–ZnO system operates via an S-scheme mechanism. In this model, after simultaneous excitation of both semiconductors, electrons from the CB of CeO2 recombine with holes from the VB of ZnO at the interfacial contact region. As a result, high-energy electrons are preserved in the CB of ZnO (E_CB = −0.23 eV) and highly oxidative holes remain in the VB of CeO2 (E_VB = 2.63 eV), see Figure 12.

Figure 12.

S-Scheme of the CZ1.5 catalyst.

Figure 12.

S-Scheme of the CZ1.5 catalyst.

This charge separation retains the strong reducing power of electrons in the CB of ZnO, sufficient to reduce O2 to O2•−, and the strong oxidizing potential of holes in the VB of CeO2, capable of oxidizing H2O or OH− to generate •OH. Both radicals are key species in the degradation of 2,4-D, which explains the superior photocatalytic activity observed for the CZ1.5 catalyst.

Furthermore, the evidence of oxygen vacancies and the presence of Ce3+ detected by XPS support the S-scheme model, as these defects act as charge traps that promote the directional migration of electrons and holes, minimizing non-radiative recombination.