1. Introduction

Among all kinds of information that human sensory system can accept, visual information occupies a crucial position (about 83%) in the five main senses (vision, hearing, taste, smell, and touch). In the historical process, people’s increasing demands for visual information acquisition and processing technology, have promoted continuous updating and iteration of optical instruments. They gradually evolve from fixed focal-length system to tunable ones [

1].

At present, there are two common tunable methods for optical devices on the market. One is digital zoom, and the other is optical zoom. Digital zoom is based on software through the built-in graphics processor, which fills the entire picture with interpolation or other algorithms on some pixels of the image sensor, such as the charge coupled device (CCD), and complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS). Specific processing means are usually required to improve the serious loss of image quality, as far as possible to make up for the quality gap with the original image. Optical zoom is based on hardware or manual regulating mechanism [

2], the mechanical device may be utilized to adjust the relative position of lens groups, so that the focal-length adjustment of the system is achieved.

In some special scenarios where there are strict limits on the size of optical system, high quality and efficient capabilities are desired, such as in physical treatment [

3], robot vision, integrated circuit lithography machines and smart phones. Inspired by the tunable principle of human eyes, a new kind of soft lenses has gradually won researchers’ attention in recent years. Unlike traditional tunable system, such lenses generally do not need to use any mechanical moving parts. The focal length can be adjusted by changing the curvature shapes of the lens surfaces or the refractive index of medium material. This kind of bionic lenses has the characteristics of compact structure, low power consumption and fast response. They have huge market application value.

With the development of robot technology, intelligent robots are coming out, which interact with nature, adapt to complex environments independently and work cooperatively. One of the important application fields is human-machine interface (HMI) and interaction. At present, a variety of traditional robot interactions based on hard materials, have been developed for different needs. However, the field of interaction between soft machine and human, remains to be developed and deeply explored [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Human eye movements are divided into: ①saccade (the focus moving immediately from one point to another. ②Moving smoothly (observing the changing objects slowly. ③Compensating movement (keeping the focus relatively fixed). ④Divergent motion (moving to maintain stereoscopic vision). Living cells, tissues or organs are often accompanied by electrical changes. Bioelectrical signals typically have the characteristics of weak (ranging from microvolts to millivolts), low frequency (0.05‒100Hz), and easily disturbed. So far, Electroencephalogram (EEG) and Electrocardiogram (ECG) signals have been widely used in medical and scientific research [

9].

Similarly, measurable potential changes in eye movements are called electro-oculograms (EOG). EOG is the easiest of all bioelectrical signals to measure. Its signal amplitude is from 15 μV to 200 μV, and in the case of relatively fixed head position, eye signal interference is also small. Because the frequency difference between EOG signal and the noise is obvious, and the noise can be eliminated by a simple filtering method. EOG can be utilized to monitor eye movement up to 70º from the central point with an accuracy of 2º. EOG signals have been successfully applied to multi-degree-of-freedom motion control of wheelchairs and robots [

10,

11,

12].

In terms of soft tunable lens materials, the electroactive polymer (EAP) is more common. It is a collective name of new soft active material (SAM), and can efficiently convert electric field excitation into mechanical response. It is often referred to as ‘artificial muscle’ because of its good biocompatibility [

13,

14,

15]. According to the actuating principle, EAPs can be divided into two categories: ionic EAPs driven by ion migration or diffusion, and electronic EAPs driven by applied electric fields and electrostatic forces. On the one hand, ionic EAPs have lower driving voltages than electronic EAPs [

16]. On the other hand, electronic EAPs can produce greater strains than ionic EAPs. The dielectric elastomer (DE) as an electronic EAP, is the preparation material for common bionic devices [

17,

18].

In the deformation theory of the DE material, Suo [

19] developed the uniform field theory and established the dielectric elastic force-electric energy transformation model based on thermodynamic equilibrium state. And the model was applied to the analysis of vacuum (elastic dielectric with lost stiffness), incompressible materials, ideal DE, electro-constrictive materials, and nonlinear dielectric materials. The dissipative processes, such as viscoelasticity and dielectric relaxation, were studied by non-equilibrium thermodynamics. These models were recognized as the fundamental theory of DEs, and remained alive in continuous innovation.

Carpi et al. [

20] proposed a lens structure based on DE. Two radially pre-stretched DE films enclosed the liquid, then flexible chamber formed was a convex lens. The tunable function was realized by a circular DE actuator (DEA) around the lens. When the initial diameter of the lens was 7.6 mm, the driving voltages increased from 0 to 3.5 kV, and its focal length changed from 22.73 ~ 16.72 mm. However, because the electrode material was coated on the optical path, which displayed a challenge to the lens transparency. Wang et al. [

21] prepared an all-solid-state tunable soft lens, and water-based polyurethane (PEDOT) transparent electrodes. The experimental result showed that the focal‒length change achieved 209%. The lens was not disturbed by the vibration, and was insensitive to the placement direction.

Lau et al. [

22] designed a soft lens with a diameter of 8 mm, the DE film thickness was reduced with adopting stacked arrangement, which was benefit for reducing the actuating voltage. It realized focusing objects from 15~ 50 cm at the voltage range of 0 to 1.8 kV. Zhong et al. [

23] proposed a soft tunable lens based on ionically polyelectrolyte elastomer, it achieved the focal-length change of 46.4% under a voltage, superior to that of the human eye. Yin et al. [

24] presented a lens based on the DEA, and it was improved by origami mechanism with a modified Yoshimura tessellation structure. The focal length of the 10-mm-diameter solid lens showed a tunability of 17%. Current researches mostly focus on the design of soft lenses, while relevant theories and data on interaction technology are relatively rare.

In order to further expand and deepen the theory and application of soft lenses, combined with eye-control interaction technology, a more intelligent lens was designed for simulating a human-eye lens. The effects of DEA layout, lens size, eye movement signal, applied voltage on the adaptive interactive lens, were studied. Finally, experiments were conducted to verify the theoretical model.

2. Soft Lens Design and Eye Interactive Control

2.1. Soft Lens Design

Acrylate copolymers are one of the most well-studied DE materials, and these elastomers exhibit great driving strain, pressure, and energy density when high voltages are applied. However, most of these polymers have a certain amount of viscoelasticity, which causes them to respond slowly. The prestretching is the key parameter to help them achieve greater electro-induced strain and higher energy density. Electromechanical instability (EMI) could also induce thin films with low elastic modulus breakdown and slow response. Acrylic copolymer VHB 4905/4910 of 3M company was used to make soft lenses in this work. Electrocardiogram conductive paste (ionic gel) was as the flexible electrode.

The motion deformation of the bionic lens was controlled by EOG (Electroophthalmic sensor) signals, which reflected the changes in the potential difference between the cornea and the fundus (retina).

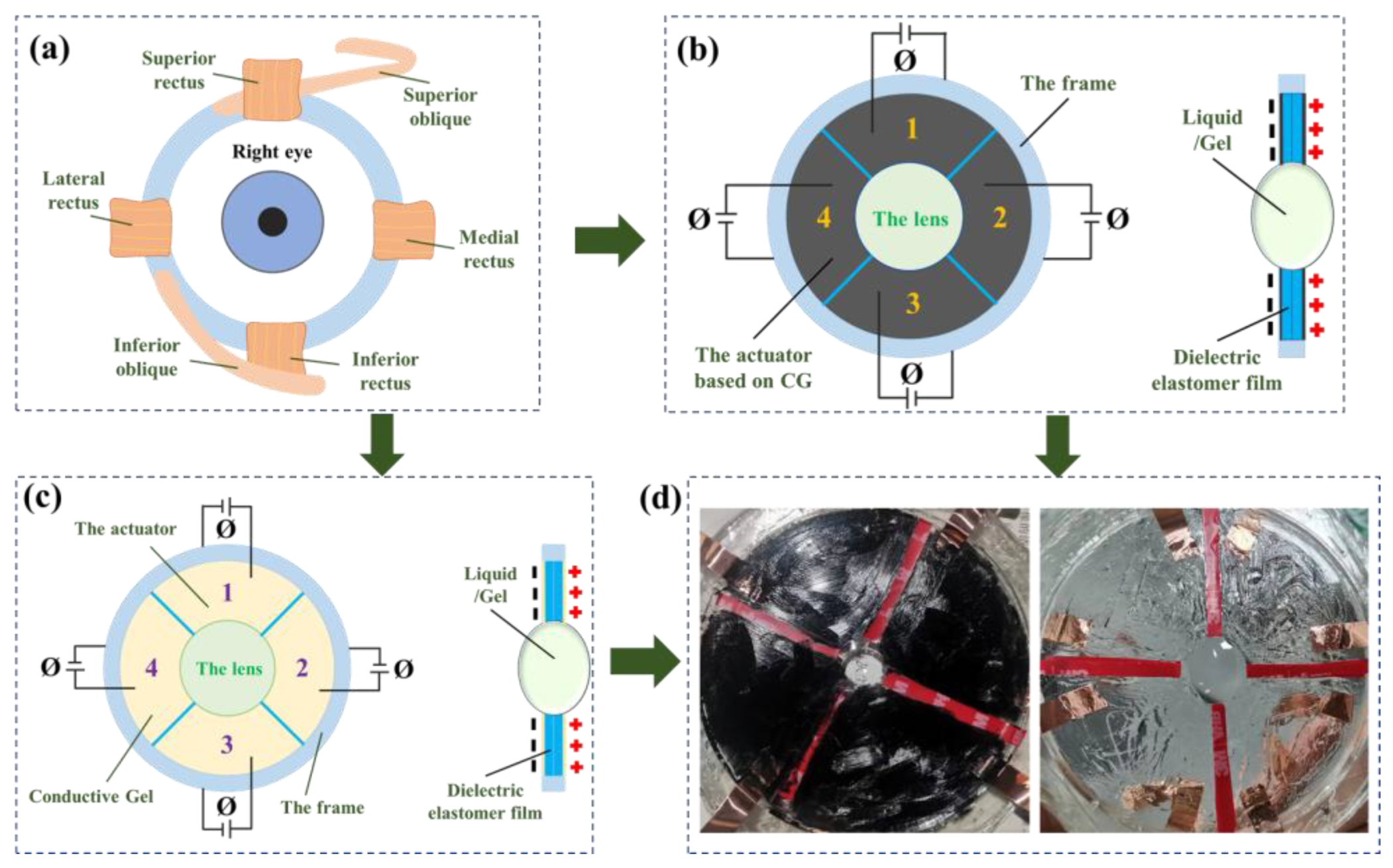

Figure 1(a)‒(c) are the schematic diagram. The human right eye is shown in

Figure 1a. The left and right sides of a human eye are the inner and outer rectus muscles. The upper and lower rectus muscles, oblique muscles are distributed in the eyeball.

Figure 1b is a bionic lens based on carbon grease electrodes. The DE film wraps the transparent medium (liquid/hydrogel). Four actuators are distributed around the lens, and the supporting frame is made of the hard acrylic sheet.

Figure 1c is the lens based on transparent hydrogel electrodes which are the conductive paste. The actual lens is shown in

Figure 1d, and the prestretching λ is 2.5 in the left picture, the diameter

d is 1 cm. The lens is sealed with water, and there are four carbon grease actuators distributed around it. In the right picture of

Figure 1d, λ is 2.5 and

d is 1.9 cm. Water encapsulates inside the lens, and four actuators with hydrogel electrodes are around it.

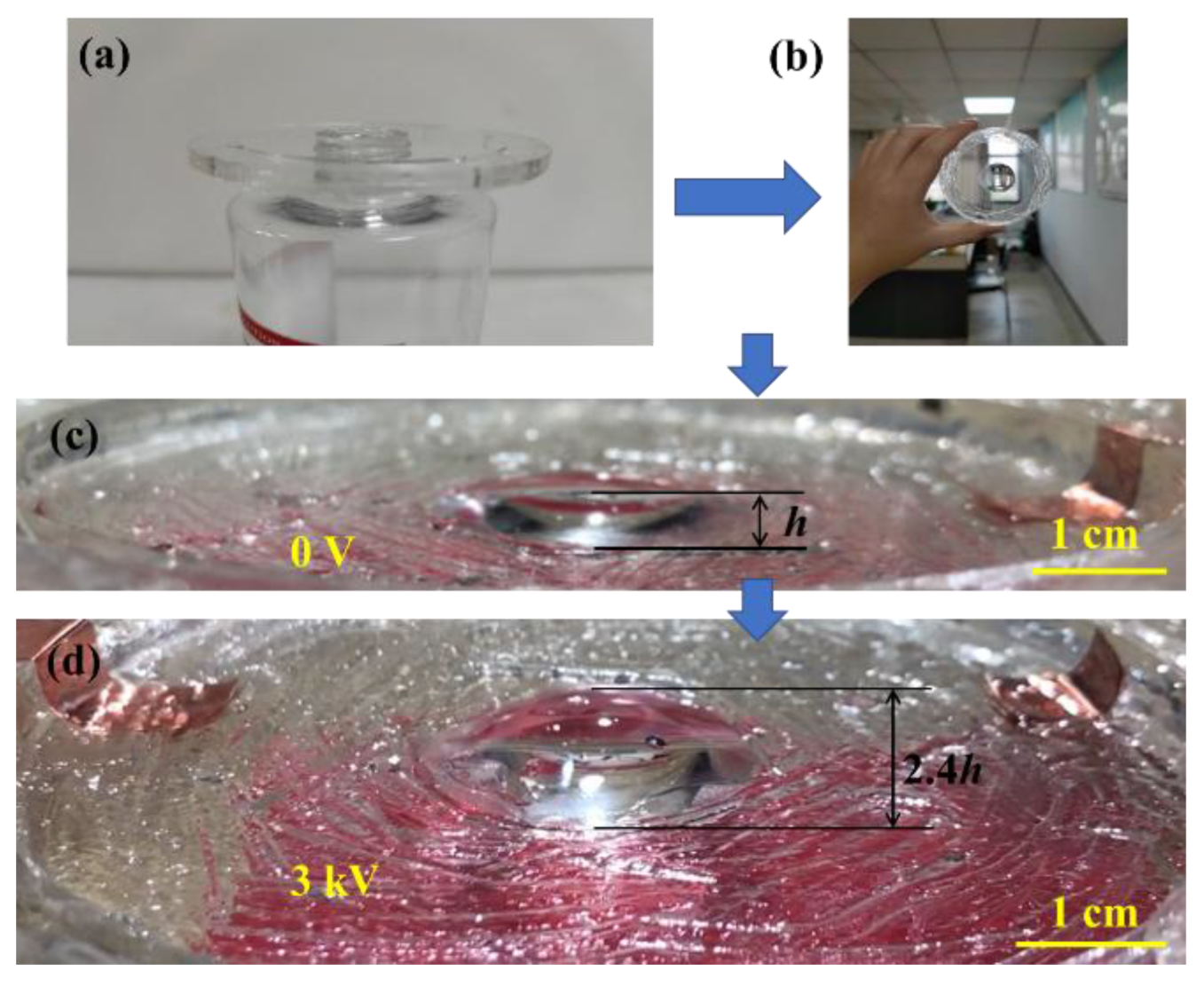

The negative‒pressure method is mainly used in the lens production. The convex lens is stable as shown in

Figure 2(a)‒(b). Using transparent conductive paste as the actuator electrodes and filling medium, the finished lens in the original state is displayed in

Figure 2c. No voltage is applied, the prestretching ratio

λ of the lens film can be set between 1and 4. The height of the lens is

h×2. In the actuated state, the overall height of the lens becomes 2.4

h×2 (FIG. 2d), and the voltage is 3 kV. The applied voltage range is from 0 to 6 kV in experiments.

20P15 model of Glassman FR Series is used for the high‒voltage power supply. The product receives PC instructions through the serial port, and returns its status information. LabVIEW software controls the high‒voltage power supply. Firstly, open the serial port and configure information, then send control instructions to the Glassman voltage amplifier, finally receive the feedback from the voltage amplifier, and close the serial port. The voltage control algorithm is completed in LabVIEW for the lens.

2.2. Eye Movement Interactive Control

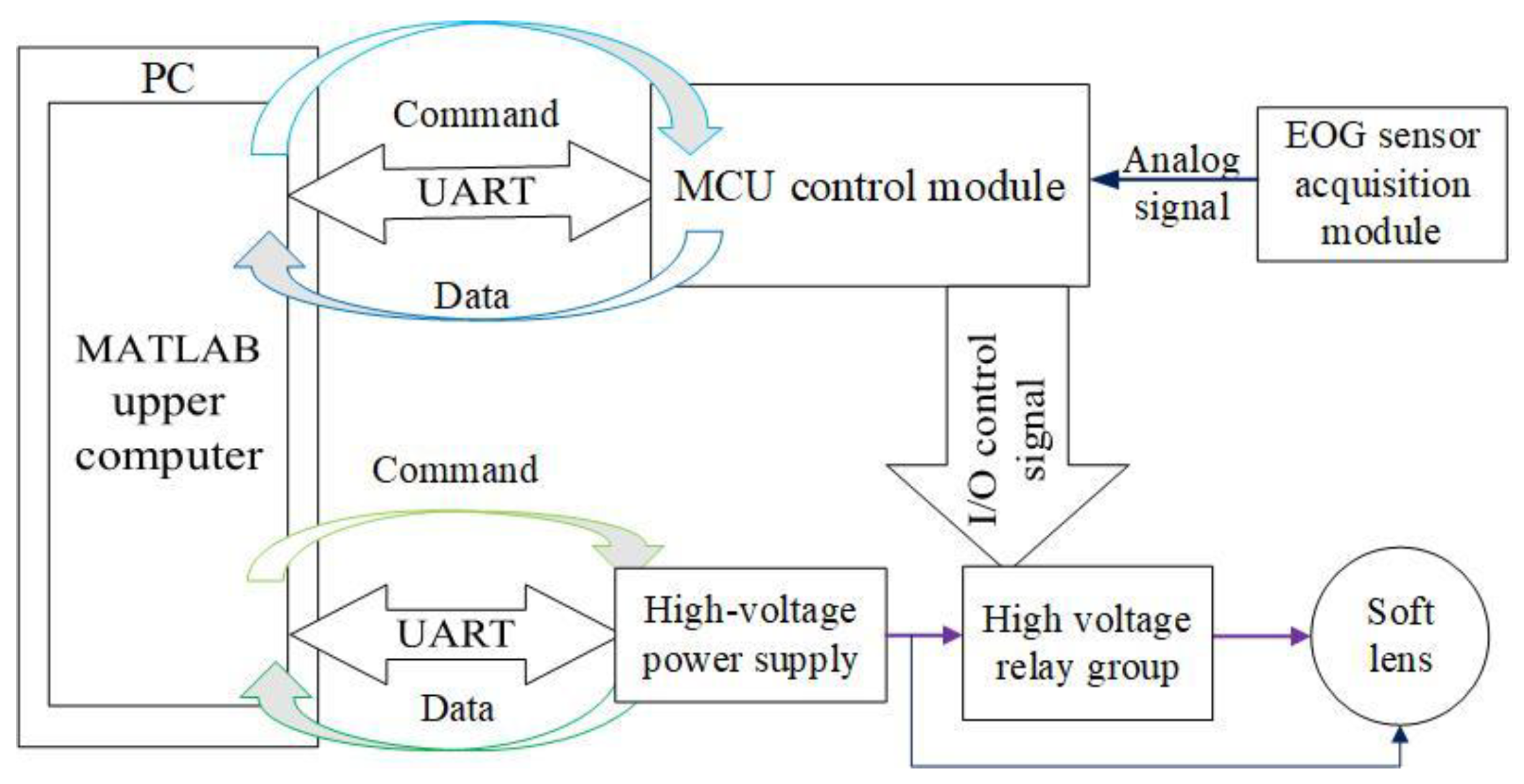

The eye‒movement interactive control design of the bionic lens is displayed in

Figure 3, which includes EOG sensor acquisition module, MCU control module, high voltage relay group, high‒voltage power supply, soft lens and upper computer analysis and processing module. The signal acquisition circuit is used to collect the epidermal electrical signals around the eyes. In order to reduce the offset and obtain a suitable resistance signal, the skin needs to be cleaned firstly. To measure the eyeball potential, electrodes are usually placed on the skin on the left and right sides of the eyes to measure horizontal motions. And they are placed on the upper and lower sides of the eyes to measure vertical movements. The ground electrode is placed on the forehead.

The division control designs of EOG sensor acquisition module, microprogrammed control unit (MCU) control module, and welding design of high‒voltage relay group, are as following. The EOG sensor acquisition module uses two AD8232 integrated to collect the up‒down and the left‒right eye‒movement signals, respectively. After internal amplification processing, the signal is mapped to the analog voltage of 0‒3.3V.

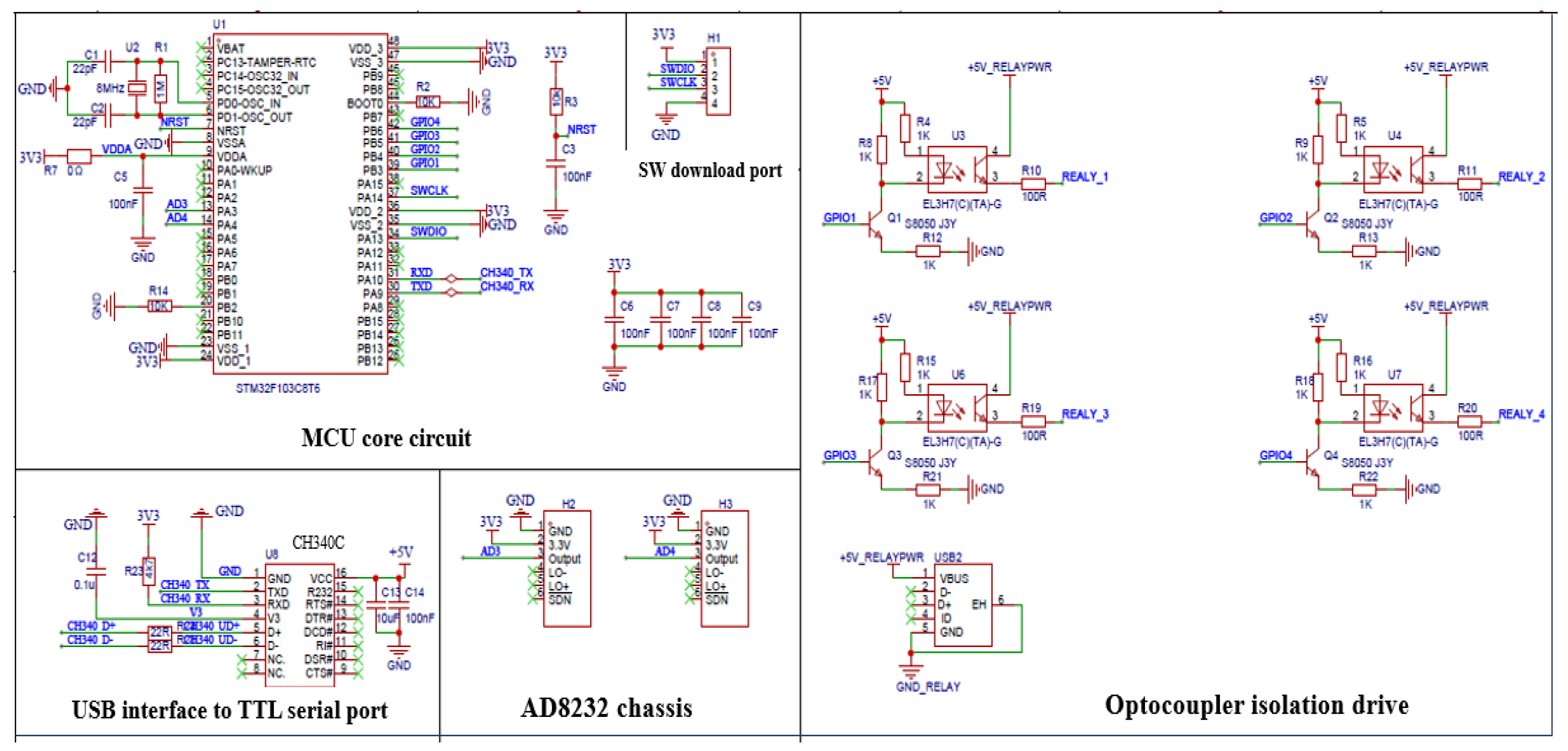

The MCU control module adopts STM32F103C8T6 as the main control chip, the GPIO pin of the chip is utilized to control the opening and closing of the high voltage relay group. The ADC pin converts the analog voltage signals from the AD8232 module into digital signals. The main control chip uses the serial port to receive the instructions of the upper computer, and send back the response data frame.

The instruction set and the format of the response data frame, are shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2. When the MCU receives the instruction to query the connection status of the lens, the instruction is to close the relay and disconnect the relay. They are all 0x00, such as the upper and lower channels, the left and right channels, and the timestamp data. When receiving the instruction to query EOG sensor data, the upper‒lower and the left‒right channel data are assigned to the analog-to-digital conversion. The timestamp data is assigned when the instruction is executed, and it is zero at the MCU power-on moment.

The high-voltage relay group module is composed of four relays (type: CRSTHV-5-1U-6k-9) and peripheral circuits. The low‒voltage control end of the relay is connected to the GPIO pin of the MCU. The high‒voltage control end has two normally open contacts, which are connected to the soft lens and the high‒voltage power device. When the GPIO pin outputs high voltage, the normally open contact of the relay closes. When its output is low, the normally open contact is disconnected. The circuit design of the control system is demonstrated in

Figure 4.

The four DEAs are around the bionic lens coated with electrodes, and the positive and negative terminals are extracted, respectively. The positive terminal is connected to the output of the relay group, and the negative one is connected to the power. When the normally open contact of the relay is closed, the high voltage is applied to the DEA. Then DE films deform to actuate the motion of the soft lens.

The upper‒computer analysis and processing module is designed based on the designer development platform of MATLAB software. Two serial ports are opened through API call, and they are used to communicate with the single-chip microcomputer module and the high-voltage power device, respectively. The host computer first opens the serial port to connect with the MCU module and the high-voltage power, sends the instruction of reading the EOG sensor data to the MCU with the set frequency, then receives the data frame sent back by the singlechip. It is analyzed according to the frame format definition. Then the upper, lower, left and right channels, and timestamp data are obtained. The signal waveforms of the two channels are reconstructed.

The upper‒computer software utilizes the face‒detection feature extraction algorithm [

25] to process the features of unidirectional eye movements.

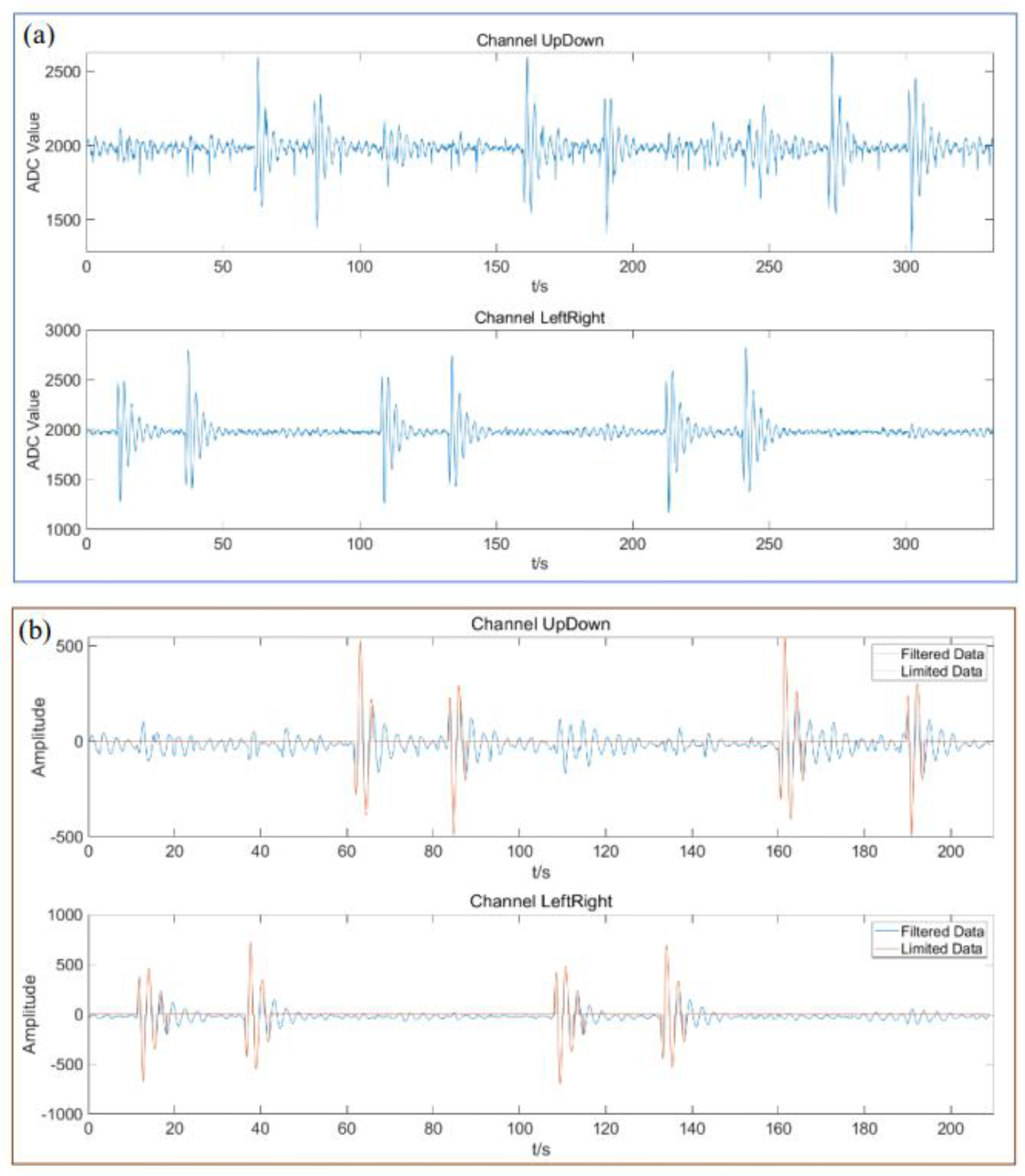

Figure 5a exhibits the original EOG signal of the subject in an experiment. Data in the range of 0‒210s are intercepted for analysis. After approximate zero averaging, five points of window width are selected for filtering and moving average. The blue curve in

Figure 5b is the waveform after moving average filtering. Set the limiting filter thresholds for the upper, lower, left, and right channels as orange curves shown. According to the results of limiting filter, the formula is taken as

. It is as the reference signal. Then the motion correlation coefficient is calculated from the results of limiting filter.

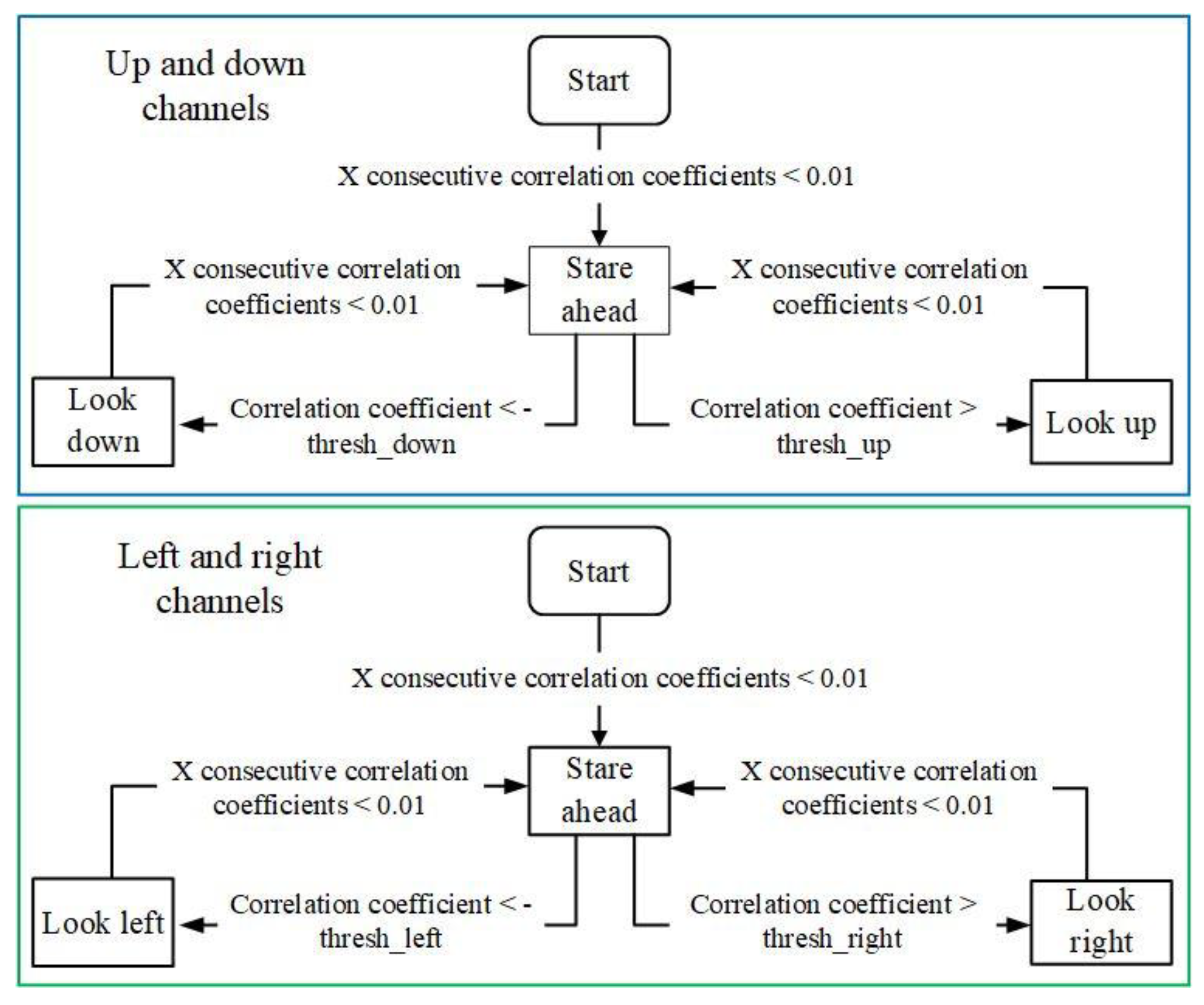

Furthermore, the state machine for feature extraction of unidirectional eye movement is designed in

Figure 6. By setting appropriate values for the variables

X, thresh_up, thresh_down, thresh_left, and thresh_right, the state machine can extract unidirectional eye‒movement features from the movement‒correlation coefficient curve when the movements occur and end. According to eye movements, the corresponding instructions are sent to the MCU module to control the relay group.

The soft lens moves to the same direction as the eye movement.

Table 3 records time when unidirectional eye movement occurs and ends in the waveform (

Figure 5a) including the results and errors of the state‒machine recognition (

Figure 6). The errors are also given in

Table 3, and the recognition results of the state machine are accurate.

3. Data Analysis and Result Discussion

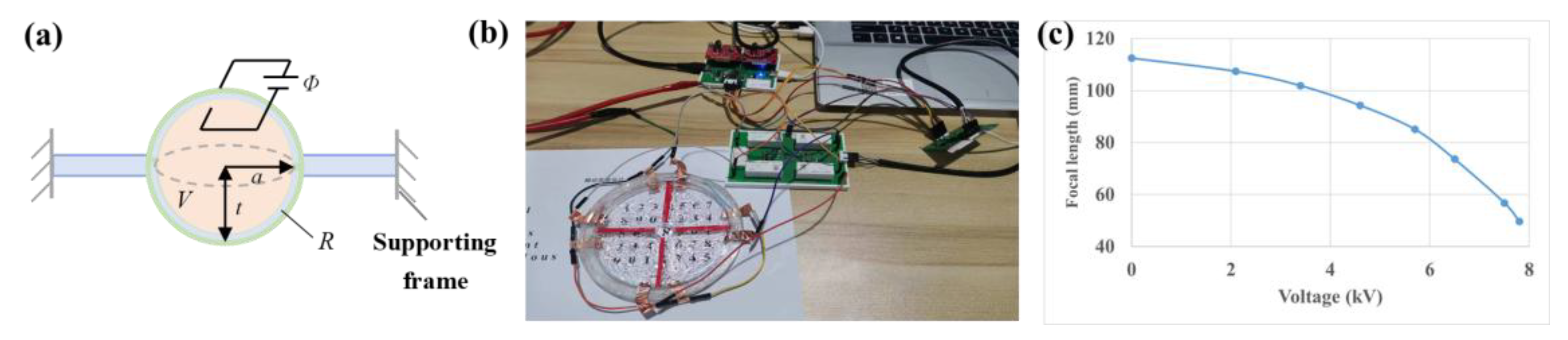

In the initial state, the lens radius is A, and the surface area is

. The shape of the lens is regarded as a sphere, and the curvature radius is

R. Its projection in the middle plane is a circle, the radius is a, and the distance between the sphere top and the middle plane is

t in

Figure 7a. Then the geometric relationship exists as

. The relationship between the curvature radius

R and the volume

V of the liquid in a spherical lens is

. It is deduced as

[

26,

27,

28]. The relation between the focal length and the curvature radius is

, where

n1 and

nm are the refractive indices of the lens and the filling medium, respectively. Because the lens works in air, so that

nm equals 1. The two curvature radii of a convex lens satisfy the equation

R2=

R1=

R.

To verify the established focal‒length model, a liquid lens based on DE was designed and fabricated as shown in

Figure 7b. According to the convex lens imaging law,

u is set as the distance from the object to the lens,

v is the distance from the image to the lens, and

f is the lens focal length. There is a relationship as

. The double focal‒length method (

u=2

f, inverted and equal-sized real image) was used to measure the focal‒length change before and after applying voltages.

Laboratory results have revealed that the larger the initial focal length, the area of coated electrodes, and the biaxial pre-stretching multiple are, the greater the focal‒length changes are [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. The experimental data records are illuminated in

Table 4, and the voltage‒focal length function is demonstrated in

Figure 7c. Perform equal biaxial fourfold prestretching on the VHB film (λ=4), and apply the voltage (7.8 kV), the focal length varies from 112.5 mm to 49.7 mm. The maximum focal-length change could achieve 58.9% in the range of 95.3~39.2mm.

The interactive movement is controlled by the interface button in real time. For example, the serial communication is responsible for receiving data from STM32, and the create and save buttons can execute instructions to create files and save ophthalmic data, respectively. The start and pause buttons control the experimental start and end in MATLAB software. The interface of the ophthalmic signal channel shows the signal acquisition and processing effect, which includes the double-channel ophthalmic signal after preprocessing, and the energy waveform of each frame after being split.

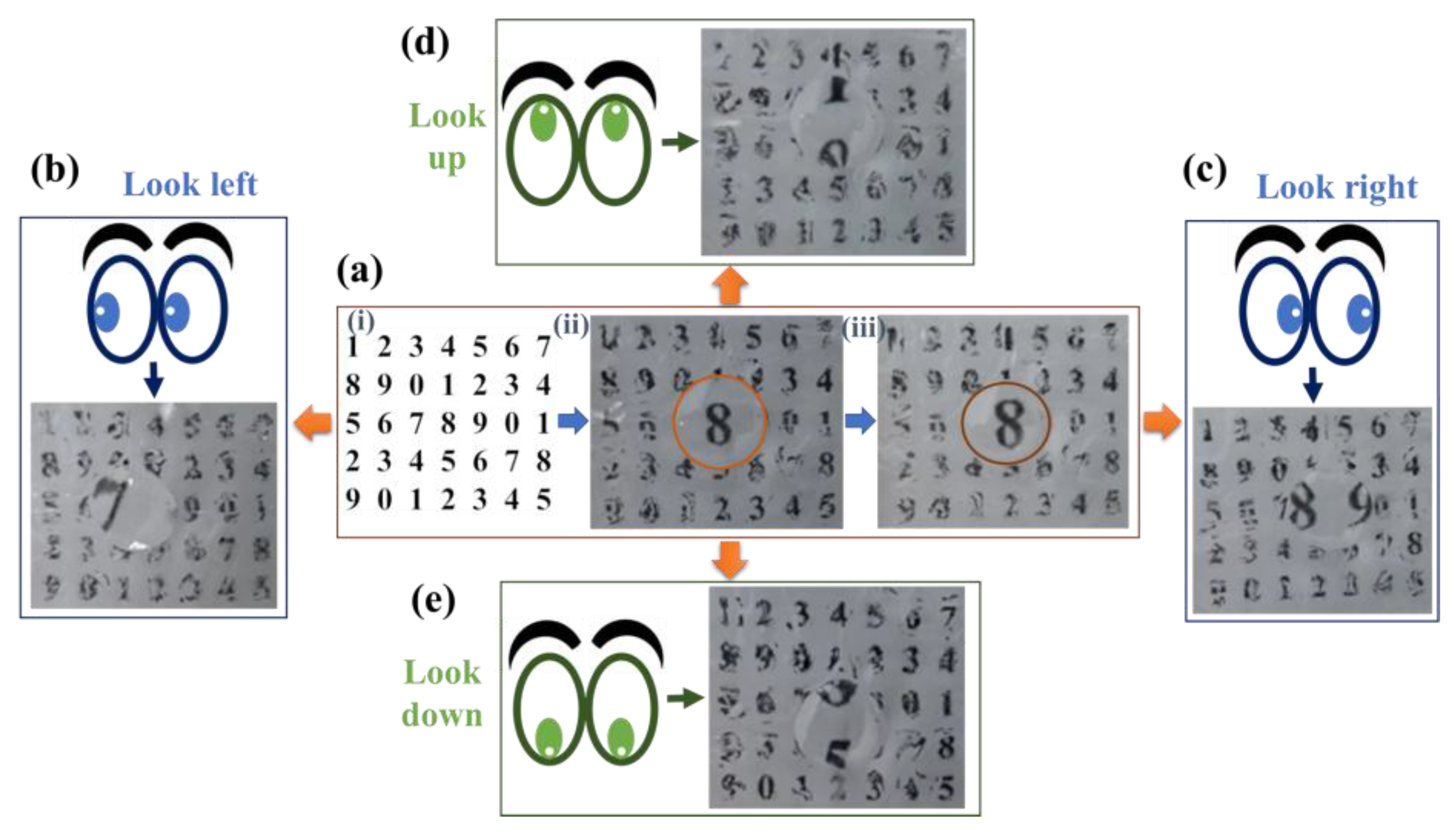

The results of hardware and software designs are verified through experiments in

Figure 8. The adaptive lens can recognize human‒eye movements and zoom-control signals successfully. Through the circuits and MATLAB control program, the function of synchronizing interaction between the soft lens and eye movements is realized. In the reference state, the driving voltage Φ is 0 kV, the lens is facing the number 8 in the center of

Figure 8a(i), and the distance of each number is about 4 mm. Observe the control effect of the lens in the up, down, left and right movements, specifically look at the data 7, 1, 9, 5 around the number 8 to calculate the lens moving distance in each direction (about 2 mm). In addition, for human strabismus such as oblique up or down and other directions, the efficiency of the recognition method is normally.

Furthermore, observe the size change of the number 8 to determine the zooming effect, the number 8 is significantly enlarged. The lens film in

Figure 8 is prestretched by 3, the diameter of the lens is 1.2 cm, and the actuating voltage is 4 kV. The soft lens can achieve a moving distance of 5 mm with the voltage. Since the distance between the number and the lens is less than the focal length

f, the resulting image is virtual. In short, the response time of the adaptive lens was less than 1s, and eye‒movement interaction efficiency was more than 93% during the experiments.

4. Conclusion

Based on the dielectric elastomer actuator, the lens structure and its focal-length change model were constructed. The ophthalmic signals were collected by bipolar electrode lead, and the control circuit was designed to amplify the signals transmitted to the upper computer. Meanwhile, the synchronous eye‒movement signals were controlled by the high-voltage relay group. The quadruple prestretched lens (λ=4) achieved controllable focal-length change of 58.9%.

The MATLAB software was utilized to amplify and filter ophthalmic signals. The recognition algorithm was designed based on the signals to identify eye movements, which completed the linear online interaction between human eyes and the bionic lens. Up and down, left and right, and zoom motions of the lens are controlled in real time. Comparing the previous interaction of soft devices, most of them were pre-controlled or manually controlled. The online interaction mode of the adaptive lens had a control delay of 0.8 s, and the eye-control efficiency is more than 93% during the experiments.

In the future, deep learning algorithms can be introduced to mark and train the electrical signals generated by various eye movements to improve the recognition accuracy. In brief, with the continuous update and iteration of optical instrument technologies, soft adaptive lenses will have broad application prospects in the fields of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV), optical communication, medical diagnosis, robot vision, consumer electronics and wearable augmented reality (AR)/virtual reality (VR) devices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H. Z.; Methodology and Validation, Z. J. X. and Z.S. Z.; Writing—original draft, H. Z.; Review and editing, J. X. Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Youth Foundation (Grant No. 52405304).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhao, Z. Z.; Kuang, F. L.; Zhang, N. H.; Li, L. Adaptive liquid lens with tunable aperture. IEEE Photonics Technology Letters 2021, 33(23), 1297–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Qin, J. G.; Gao, Y.; Cao, L. L.; Liu, X. J.; Zhu, Z. C. Soft lenses with large focal length tuning range based on stacked PVC gel actuators. Smart Materials and Structures 2024, 33(9), 095002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yue, S.; Tian, Z.; Zhu, Z. J.; Li, Y. J.; Chen, X. Y.; Wang, Z. L.; Yu, Z. Z.; Yang, D. Self-Powered and Self-Healable Extraocular-Muscle-Like Actuator Based on Dielectric Elastomer Actuator and Triboelectric Nanogenerator. Advanced Materials 2024, 36(7), 2309893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. X.; Wen, H.; Fan, Y. Y.; Yang, X. L.; Zhang, H.; Wu, W. Y.; Zhou, Y. J.; Hu, H. B. Recent advances in gas and environmental sensing: from micro/nano to the era of self-powered and artificial intelligent (AI)-enabled device. Microchemical Journal 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G. R.; Chen, X. P.; Zhou, F. H.; Liang, Y. M.; Xiao, Y. H.; Cao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, M. Q.; Wu, B. S.; et al. Self-powered soft robot in the Mariana Trench. Nature 2021, 591, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirbu, I. D.; Moretti, G.; Bortolotti, G.; Bolignari, M.; Diré, S.; Fambri, L.; Vertechy, R.; Fontana, M. Electrostatic bellow muscle actuators and energy harvesters that stack up. Science Robotics 2021, 6(51), eaaz5796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Zheng, S.; Tan, J.; Cheng, J. Z.; Cai, J. C.; Xu, Z. S.; Shiju, E. An Integrated Charge Excitation Alternative Current Dielectric Elastomer Generator for Joint Motion Energy Harvesting. Advanced Materials Technologies 2024, 9(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaconescu, A.; Deaconescu, T. Compliant Parallel Asymmetrical Gripper System. Technologies 2025, 13(86), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, S.; Dai, Y.; Gao, S. An Eye Tracking and Brain–Computer Interface-Based Human–Environment Interactive System for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Patients. IEEE Sensors Journal 2023, 23(20), 24095–24106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. R.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L. W.; Xu, S.; Liu, Y. J.; Leng, J. S.; Cai, S. Q. A biomimetic soft lens controlled by electrooculographic signal. Advanced Functional Materials 2019, 29(36), 1903762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A. Wheelchair control for disabled patients using EMG/EOG based human machine interface: a review. Journal of medical engineering & technology 2021, 45(1), 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ileri, R.; Latifolu, F.; Demirci, E. A novel approach for detection of dyslexia using convolutional neural network with EOG signals. Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing 2022, 60(11), 3041–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q. S.; Yin, G. X.; Vokoun, D.; Shen, Q.; Lu, J.; Liu, X.; Xu, X.; Yu, M.; Dai, Z. Review on improvement, modeling, and application of ionic polymer metal composite artificial muscle. Journal of Bionic Engineering 2022, 19(2), 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, M. R.; Sessions, D.; Arora, N.; Chen, V. W.; Juhl, A.; Huff, G. H.; Rudykh, S.; Shepherd, R. F.; Buskohl, P. R. Dielectric Elastomer Architectures with Strain‒Tunable Permittivity. Advanced Materials Technologies 2022, 7(11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomori, H.; Hiyoshi, K.; Kimura, S.; Ishiguri, N.; Iwata, T. A Self-Deformation Robot Design Incorporating Bending-Type Pneumatic Artificial Muscles. Technologies 2019, 7(51), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T. F.; Li, G. R.; Liang, Y. M.; Cheng, T. Y.; Dai, J.; Yang, X.; Liu, B. Y.; Zeng, Z. D.; Huang, Z. L.; Luo, Y. W.; Xie, T.; Yang, W. Fast-moving soft electronic fish. Science Advances 2017, 3(4), e1602045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Wen, H.; Zhang, H.; Huang, P. L.; Liu, L.; Hu, H. Y. Recent advances in biodegradable electronics- from fundament to the next-generation multi-functional, medical and environmental device. Sustainable Materials and Technologies 2023, 35, e00530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.; Yun, S.; Yoon, J. W.; Park, S.; Park, S. K.; Mun, S.; Park, B.; Kyung, K. U. A robust soft lens for tunable camera application using dielectric elastomer actuators. Soft Robotics 2018, 5(6), 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suo, Z. G. Theory of dielectric elastomers. Acta Mechanica Solida Sinica 2010, 23(6), 549–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpi, F.; Frediani, G.; Turco, S.; Rossi, D. D. Bioinspired tunable lens with muscle-like electroactive elastomers. Advanced Functional Materials 2011, 21(21), 4152–4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Z.; Li, P.; Gupta, U.; Ouyang, J.; Zhu, J. Tunable soft lens of large focal length change. Soft Robotics 2022, 9(4), 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, G. K.; La, T. G.; Shiau, L. L.; Tan, A. W. Y. Challenges of using dielectric elastomer actuators to tune liquid lens. Proceedings of SPIE-The International Society for Optical Engineering 2014, 9056, 90561J. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, H.; Xue, Q.; Li, J. M.; He, Y.; Xie, Y.; Yang, C. Stretchable transparent polyelectrolyte elastomers for all-Solid tunable lenses of excellent stability based on electro–mechano–optical coupling. Advanced Materials Technologies 2022, 8(3), 2200947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X. C.; Zhou, P. Y.; Wen, S.; Zhang, J. T. Origami improved dielectric elastomer actuation for tunable lens. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2022, 71, 7502709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Huo, H.; Liu, J. Facial expression recognition based on multi-channel fusion and lightweight neural network. Soft Computing‒A Fusion of Foundations, Methodologies & Applications 2023, 27(24). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Xia, Z. J.; Zhang, Z. S.; Zhu, J. X. Miniature and tunable high voltage-driven soft electroactive biconvex lenses for optical visual identification. Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering 2022, 32(6), 064004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Cao, Y. J.; Wang, Y. N.; Liu, J.; Xie, Y. X. A computational model of bio-inspired tunable lenses. Mechanics based design of structures and machines 2018, 46(6), 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, M.; Lagomarsini, C.; De Rossi, D.; Carpi, F. Electrically tunable soft solid lens inspired by reptile and bird accommodation. Bioinspiration&Biomimetics 2016, 11(6), 065003. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Sun, B.; Xi, M.; Zhan, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, Y. Flexible electronics in humanoid five senses for the era of artificial intelligence of things (AIoT). Materials Today 2025, 88, 1066–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Yang, Y.; Xi, M.; Ji, S.; Jia, L.; Hu, T. The next-generation digital twin: from advanced sensing towards artificial intelligence-assisted physical-virtual system. Journal of Industrial Information Integration 2025, 100942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xia, Z. J.; Zhang, Z. S. Focus-tunable imaging analyses of the liquid lens based on dielectric elastomer actuator. Bulletin of Materials Science 2021, 44(2), 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, J. X.; Wen, H. Y.; Xia, Z. J.; Zhang, Z. S. Biomimetic human eyes in adaptive lenses with conductive gels. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials 2023, 139, 105689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Hong, J.; Zhu, J.; Duan, S.; Xia, M.; Chen, J.; Sun, B.; Xi, M.; Gao, F.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, F.; Cai, B.; Zhan, Y.; Xie, X.; Shi, Q.; Wu, J.; Lee, C. Humanoid electronic-skin technology for the era of artificial intelligence of things (AIoT). Matter 2025, 50, 428–438. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).