1. Introduction

Abdominal wall integrity is clinically central to hernia repair and abdominal wall reconstruction, where both prosthetic reinforcement and optimized closure strategies are employed to reduce failure and recurrence rates [

1,

2]. Biomechanical investigations have consistently highlighted the importance of native abdominal wall tissue properties in determining surgical outcomes. Within this complex anatomical system, the aponeurosis represents a dense, collagen-rich connective structure responsible for the transmission and redistribution of mechanical forces generated by the abdominal musculature. Its functional integrity is essential for maintaining abdominal wall stability, and its impairment plays a key role in the pathogenesis of primary and incisional hernias, as well as in postoperative failure following abdominal wall reconstruction [

3,

4,

5].

Over the past decades, the widespread adoption of tension-free repair techniques using synthetic meshes has led to a substantial reduction in recurrence rates in abdominal wall hernia surgery [

6,

7]. However, these advances have simultaneously brought attention to a new spectrum of clinical challenges, including seroma formation, chronic pain, impaired abdominal wall compliance, and mesh-related complications [

3,

8]. Increasing evidence indicates that such outcomes are influenced not only by surgical technique or prosthetic material selection, but also by the intrinsic biological and structural characteristics of the host tissue interacting with the implant [

9,

10]. In this context, the aponeurosis constitutes a critical, yet still insufficiently characterized, interface between native tissue and synthetic materials. From a biological standpoint, aponeurotic tissue is composed predominantly of highly organized collagen fibers embedded within an extracellular matrix that confers both tensile strength and controlled deformability [

11,

12]. This organization is inherently anisotropic, reflecting the directional mechanical demands imposed on the abdominal wall [

13,

14]. While macroscopic biomechanical testing has yielded valuable information regarding the tensile behavior of aponeurotic structures, such approaches are inherently limited in their ability to capture local heterogeneities in collagen organization, surface architecture, and interaction behavior that may be highly relevant for tissue–implant integration and long-term functional adaptation [

5,

15].

At the microscale, conventional optical microscopy provides valuable insight into overall tissue morphology and collagen fiber arrangement, offering essential structural context for higher-resolution investigations. Although optical techniques do not resolve nanoscale surface features or local interaction behavior, they allow visualization of global architectural patterns, fiber orientation, and structural heterogeneity that may influence nanoscale measurements. Integrating optical microscopy with AFM-based analysis therefore supports a multi-scale characterization approach, facilitating the correlation between microscale collagen architecture and nanoscale topographical and deflection-related features.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) has emerged as a powerful tool for investigating biological tissues at the micro- and nano-scale [

16,

17]. Unlike conventional imaging techniques, AFM allows simultaneous assessment of surface morphology and relative local mechanical response with high spatial resolution [

18]. Previous AFM studies of soft tissues have demonstrated that variations in collagen organization, fibrillar density, and extracellular matrix composition can markedly influence local mechanical behavior, even within macroscopically homogeneous samples [

15,

19]. Despite its clear clinical relevance, however, the nano-scale architecture and local mechanical heterogeneity of human aponeurotic tissue remain poorly documented in the literature. A detailed AFM-based characterization of aponeurotic tissue is therefore particularly relevant in the context of abdominal wall reconstruction, where synthetic meshes are implanted in direct contact with native connective tissue [

10,

15]. Establishing the baseline nano-structural organization and local interaction behavior of macroscopically intact aponeurosis is essential for meaningful comparisons with prosthetic materials and for the interpretation of tissue responses observed following implantation [

16,

20]. Such reference data may contribute to a better understanding of why certain tissue–mesh combinations result in favorable integration, whereas others are associated with excessive fibrosis, increased stiffness, or chronic postoperative complications.

The aim of the present study is to perform a comprehensive nano-structural characterization of human aponeurotic tissue using atomic force microscopy. By combining contact-mode AFM deflection imaging with two-dimensional and three-dimensional surface topography analysis, this work seeks to describe collagen fiber organization, surface morphology, and spatial heterogeneity in deflection and interaction contrast at the nano-scale. The findings are intended to establish a biological reference framework for future comparative investigations involving synthetic meshes and to contribute to a more nuanced understanding of tissue–implant interactions in abdominal wall surgery.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. AFM Instrumentation and Software

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) investigations were performed using an EasyScan 2 atomic force microscope (Nanosurf AG, Liestal, Switzerland). Image acquisition and data processing were carried out using Nanosurf EasyScan 2 image analysis software.

2.2. Tissue Samples

A total of seven human aponeurotic tissue samples were analyzed. Specimens were harvested intraoperatively from the linea alba of middle-aged adult patients (four males and three females) undergoing scheduled abdominal surgery for benign non–abdominal wall pathology, including colorectal and gynecological conditions. All patients had body mass index values ranging between 18.5 and 21 kg/m² and presented an intact abdominal wall, with no clinical or intraoperative evidence of abdominal wall defects, previous surgical remodeling of the abdominal wall, or local inflammatory changes at the sampling site. All samples were obtained from macroscopically normal linea alba tissue.

Immediately after excision, each aponeurotic tissue specimen was divided into two portions to allow parallel analyses. One portion was processed for conventional optical microscopy, while the second portion was prepared for atomic force microscopy. Tissue fragments intended for AFM analysis (sub-centimeter in size) were immersed in RNAlater® solution to preserve tissue integrity and minimize post-excision degradation. Prior to AFM preparation, samples were briefly rinsed with DPBS (1×, pH 7.0) to remove residual storage solution.

2.3. Optical Microscopy

The human aponeurotic tissue samples were processed for conventional optical microscopy in order to obtain complementary morphological information and to provide microscale structural context for the AFM analysis. Tissue fragments were fixed in buffered formalin, routinely processed, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at standard thickness. The resulting sections were stained using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) according to standard histological protocols.

Optical microscopy was performed using a light microscope equipped with digital image acquisition. Representative images were captured at low, medium, and high magnifications (×4, ×10, and ×20) to evaluate overall tissue architecture, collagen fiber organization, cellular composition, and vascular features. Particular attention was paid to collagen bundle orientation, fiber parallelism, and the presence and distribution of resident connective tissue cells, including fibrocytes and fibroblasts.

Optical microscopy was employed as a qualitative, complementary technique to support the interpretation of AFM findings. The obtained micrographs were not subjected to quantitative histomorphometric analysis, but were used to facilitate the correlation between microscale structural organization and nanoscale surface topography and deflection-related features observed by atomic force microscopy.

2.4. Sample Preparation for AFM Analysis

To ensure stable tissue immobilization and reproducible tip–sample contact during scanning, aponeurotic tissue samples were fixed onto commercially available poly-L-lysine (PLL)–coated glass microscope slides, which promote electrostatic adhesion of biological specimens. Prior to tissue placement, the PLL-coated slides were equilibrated at room temperature. Small aponeurotic tissue fragments (approximately 3.0 × 3.0 × 1.0 mm) were placed onto the treated glass surface and gently pressed to ensure adequate contact without inducing mechanical deformation. The tissue–slide assemblies were incubated for 20–30 minutes at room temperature to allow stable electrostatic attachment.

Following immobilization, samples were transferred to phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS 1×, pH 7.0) for rinsing and short-term hydration. For AFM measurements conducted in air, samples were mounted immediately after removal from DPBS and imaging was initiated without delay to minimize dehydration-related artifacts. All AFM measurements were performed within 24 hours of tissue harvesting to minimize post-excision alterations of surface morphology. This preparation method provided sufficient mechanical stability for contact-mode AFM scanning while preserving the native nano-structural features of the aponeurotic surface.

2.5. AFM Probes

AFM imaging was performed using PPP–NCSTAuD probes (Nanosensors, Neuchâtel, Switzerland). The probes were gold-coated on the detector-facing side to enhance signal sensitivity. According to the manufacturer specifications, these highly doped silicon cantilevers have a length of 150 μm and a nominal spring constant of 7.4 N/m, with a typical tip radius < 7 nm.

2.6. Imaging Conditions

AFM measurements were conducted in air at room temperature. Surface imaging was performed in contact mode, ensuring continuous tip–sample interaction during scanning. Height and deflection channels were recorded simultaneously for all measurements. Localized AFM scans were acquired over micrometer-scale areas of 2 × 2 µm.

2.7. Deflection Imaging

AFM deflection imaging was used to assess relative spatial variations in the local tip–sample interaction during contact-mode scanning. In this mode, the deflection signal reflects cantilever bending induced by mechanical interaction with the tissue surface. Deflection contrast was interpreted qualitatively, in a comparative manner within and between scans, as an indicator of local heterogeneity in surface interaction properties. No absolute mechanical parameters were derived from deflection images.

2.8. Surface Topography and Roughness Analysis

Two-dimensional height images were acquired simultaneously with deflection data to characterize surface morphology and nano-architectural organization. Three-dimensional surface reconstructions were generated from height maps to visualize the spatial distribution of surface relief. Standard surface roughness parameters were calculated, including the arithmetic mean height (Sa), the root mean square roughness (Sq), the maximum peak height (Sp), the maximum valley depth (Sv), and the total height (Sy). These parameters were used to describe surface continuity, height distribution, and morphological heterogeneity.

2.9. Surface Profile Extraction

Surface profiles were extracted from selected regions of interest within the height maps to visualize local height variations and to correlate topographic depressions and elevations with structural features observed in AFM images. Profile analysis was performed along representative scan lines within the imaged areas.

2.10. Data Analysis

AFM data were analyzed descriptively. The analysis focused on the characterization of fibrillar organization, preferential structural orientation, surface continuity, spatial heterogeneity in deflection contrast, and nano-scale roughness features. No absolute mechanical parameters were calculated, and no inferential statistical analysis was performed.

3. Results

3.1. Optical Microscopy Findings

Optical microscopy of human aponeurotic tissue revealed a well-preserved connective architecture characterized by dense, predominantly parallel collagen fiber bundles forming an organized structural framework. At low magnification (×4), the aponeurotic fragments displayed a compact and continuous collagenous matrix with a clear preferential fiber orientation, consistent with the load-bearing function of the abdominal wall aponeurosis (

Figure 1).

At intermediate magnification (×10), the aponeurotic tissue exhibited a sparse cellular component embedded within the collagen matrix, consisting predominantly of fibrocytes with occasional elongated fibroblasts. The collagen bundles maintained a uniform and parallel arrangement, without evidence of structural disruption or pathological remodeling (

Figure 2).

Vascular structures were infrequently observed within the aponeurotic tissue and displayed preserved wall integrity, with discrete intraluminal stasis. No perivascular inflammatory infiltrate, endothelial damage, or pathological vascular remodeling was identified in the surrounding connective tissue (

Figure 3).

At high magnification (×20), optical microscopy highlighted physiological cellular heterogeneity within the aponeurotic connective tissue, characterized by the presence of fusiform, metabolically active fibroblasts alongside fibrocytes. These cells were distributed between collagen bundles without disrupting the overall structural continuity of the extracellular matrix or inducing local inflammatory changes (

Figure 4).

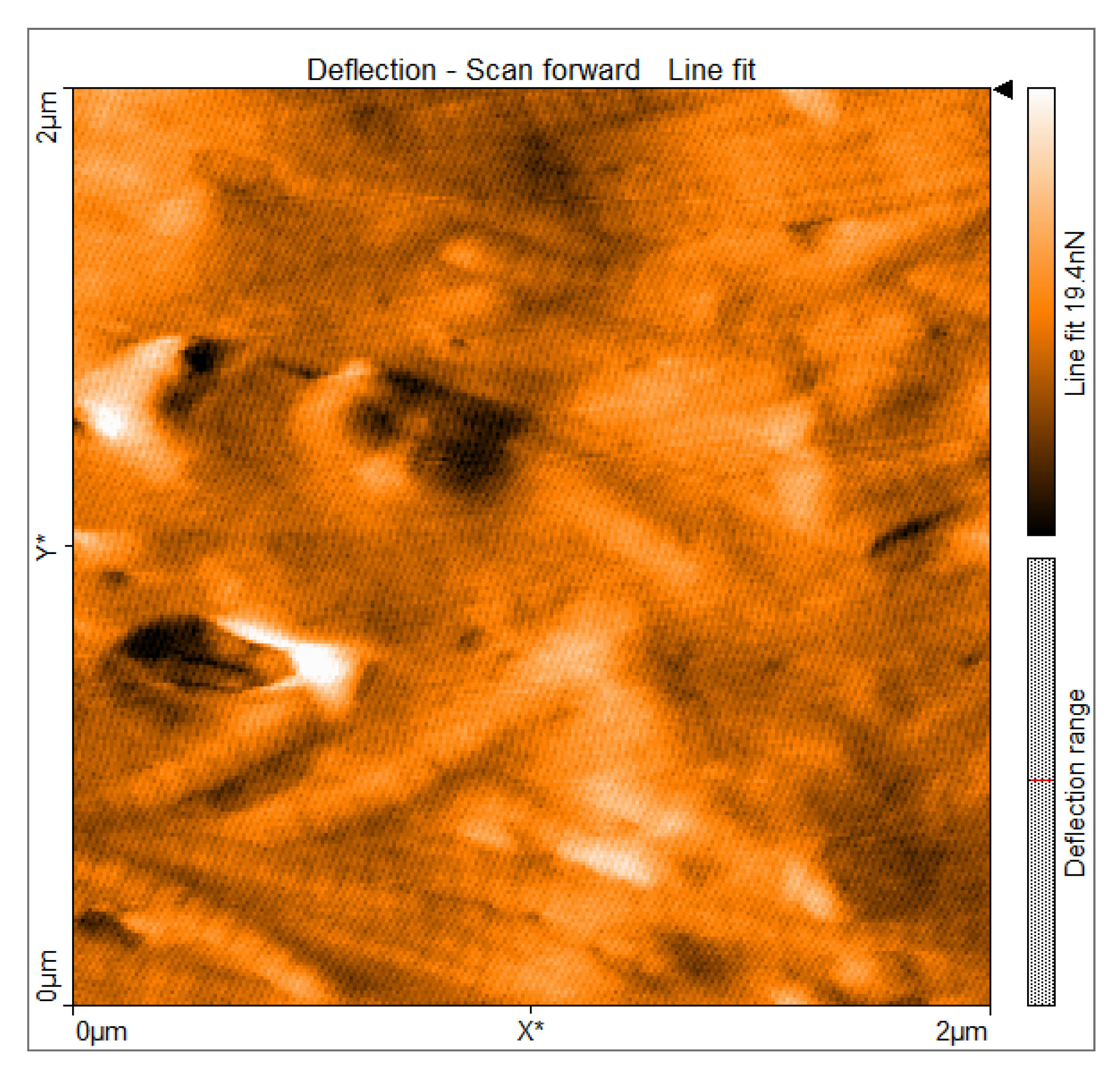

3.2. AFM Deflection Imaging of Aponeurotic Tissue

Atomic force microscopy deflection imaging revealed a well-organized fibrillar architecture of the aponeurotic tissue surface. At the scanned scale of 2 × 2 µm, elongated structures with a preferential orientation were consistently observed, forming an anisotropic surface pattern. The partial parallel alignment of these structures indicates a non-amorphous, anisotropic organization. The deflection contrast reveals marked spatial heterogeneity in the tip–sample interaction signal across the aponeurotic surface. Brighter regions correspond to areas with increased deflection contrast and spatially overlap with collagen-dense structures, whereas darker regions are associated with interfibrillar areas. These differences indicate nano-scale heterogeneity in the interaction signal across the scanned surface, reflecting the spatial organization of collagen fibers and extracellular matrix components (

Figure 5).

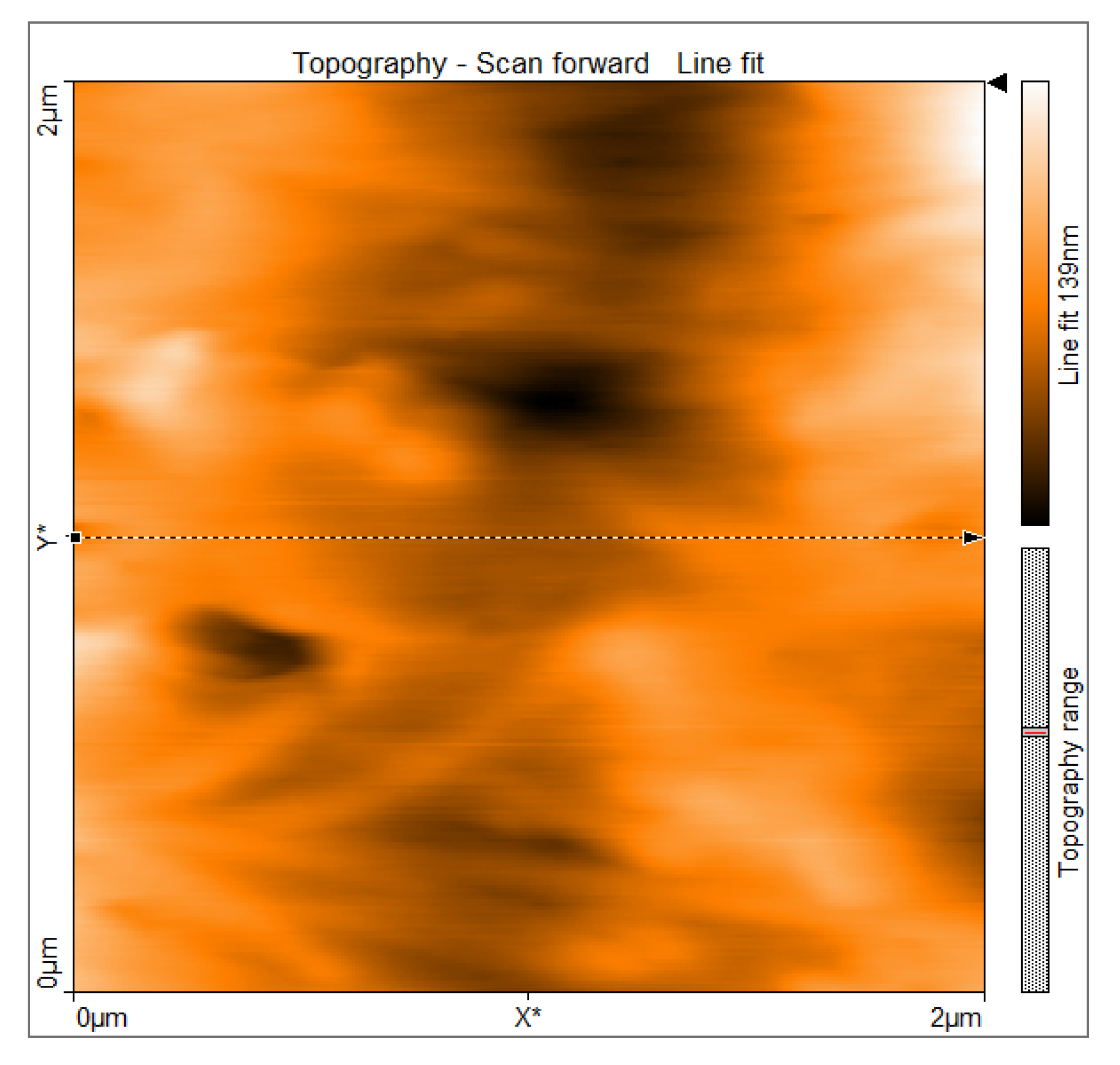

3.3. Two-Dimensional Surface Topography

Two-dimensional AFM topography demonstrated a continuous surface morphology with moderate height variations and smooth transitions between surface features. Within the scanned regions, no abrupt discontinuities, sharp edges, or well-defined pores were observed, supporting preservation of the imaged tissue architecture. The surface exhibited elongated, gently undulating structures oriented preferentially along a dominant direction. Gradual transitions between ridges and valleys were evident and corresponded to collagen fiber fascicles embedded within the extracellular matrix. This topographic organization is consistent with the anisotropic structural arrangement of aponeurotic tissue and its role in directional force transmission (

Figure 6).

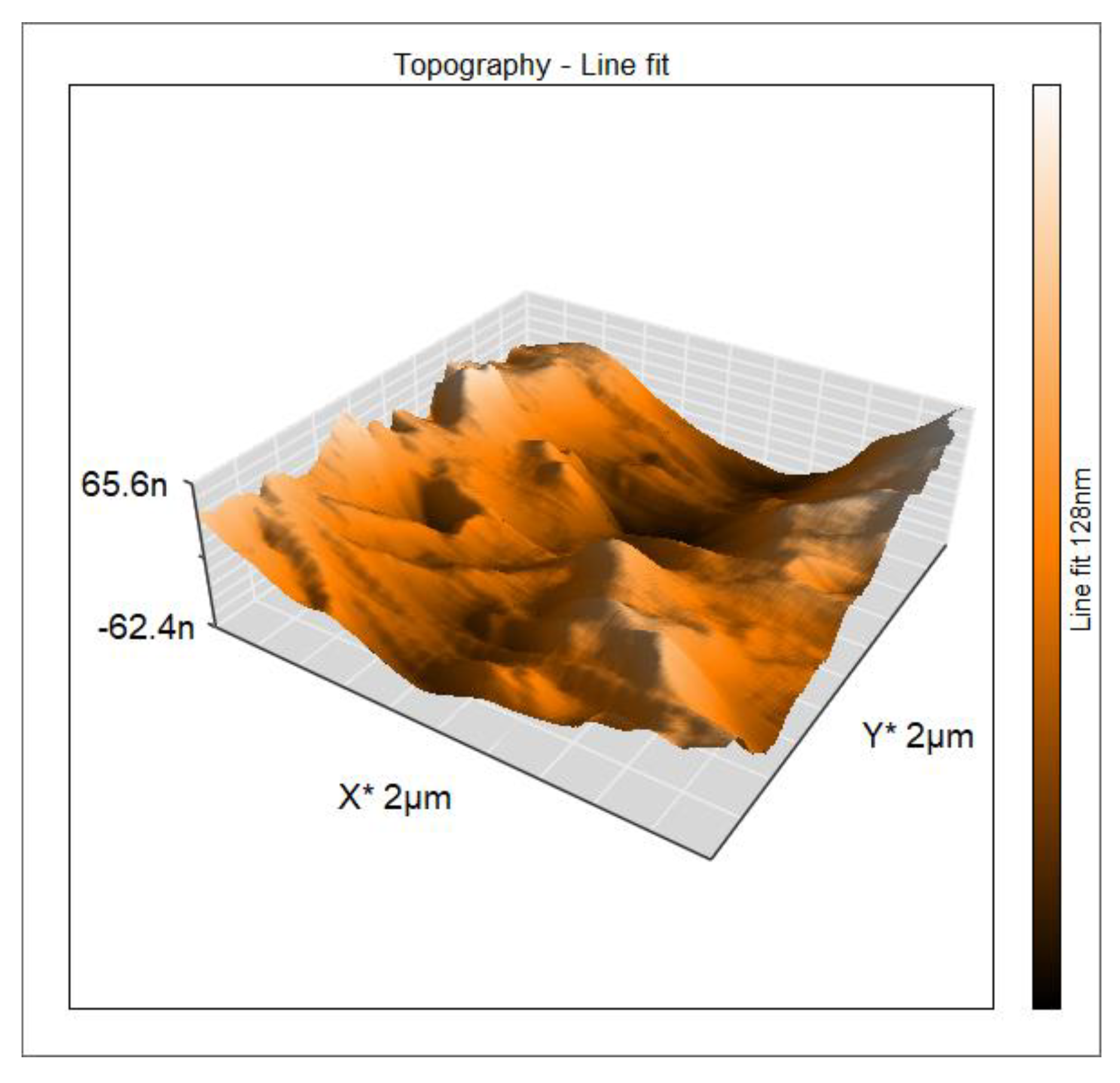

3.4. Three-Dimensional AFM Topography

Three-dimensional reconstruction of the AFM topography provided enhanced visualization of the spatial distribution of surface relief. The surface appeared continuous and compact, with an undulating morphology and gradual height variations. The Z-range after line fitting was approximately ±60–70 nm, indicating a moderate surface relief compatible with a dense extracellular matrix rather than a granular or degraded surface. The three-dimensional representation emphasized the preferential orientation of elongated ridges and valleys corresponding to anisotropically arranged collagen fiber bundles. This anisotropy was more clearly evident in the three-dimensional projection than in the two-dimensional images, reinforcing the structural specialization of the aponeurosis for directional mechanical load transmission (

Figure 7).

3.5. Surface Roughness Parameters

Quantitative roughness analysis revealed moderate values of the arithmetic mean height (Sa), consistent with a compact and structurally intact extracellular matrix. The values reported in

Table 1 are derived from representative 2 × 2 µm AFM scan areas and reflect the overall organization of collagen fibers rather than the presence of pronounced surface asperities or morphological degradation. Similar roughness characteristics were observed across all analyzed samples.

The root mean square roughness (Sq) exceeded Sa, indicating a non-uniform distribution of surface heights with localized variations. This relationship suggests spatial heterogeneity related to differences in fibrillar density and interfibrillar spacing, without evidence of chaotic or irregular surface features. Comparable surface patterns were consistently identified across the scanned regions of all seven samples. The ratio between maximum peak height and maximum valley depth (Sp/|Sv|) was close to unity, indicating that surface peaks and valleys were of comparable magnitude and lacked isolated extreme features. The total height parameter (Sy) measured approximately 143 nm in the representative scan, reflecting a moderate height difference between surface peaks and valleys and showing no features suggestive of fissures, pores, or structural ruptures within the analyzed areas (

Table 1).

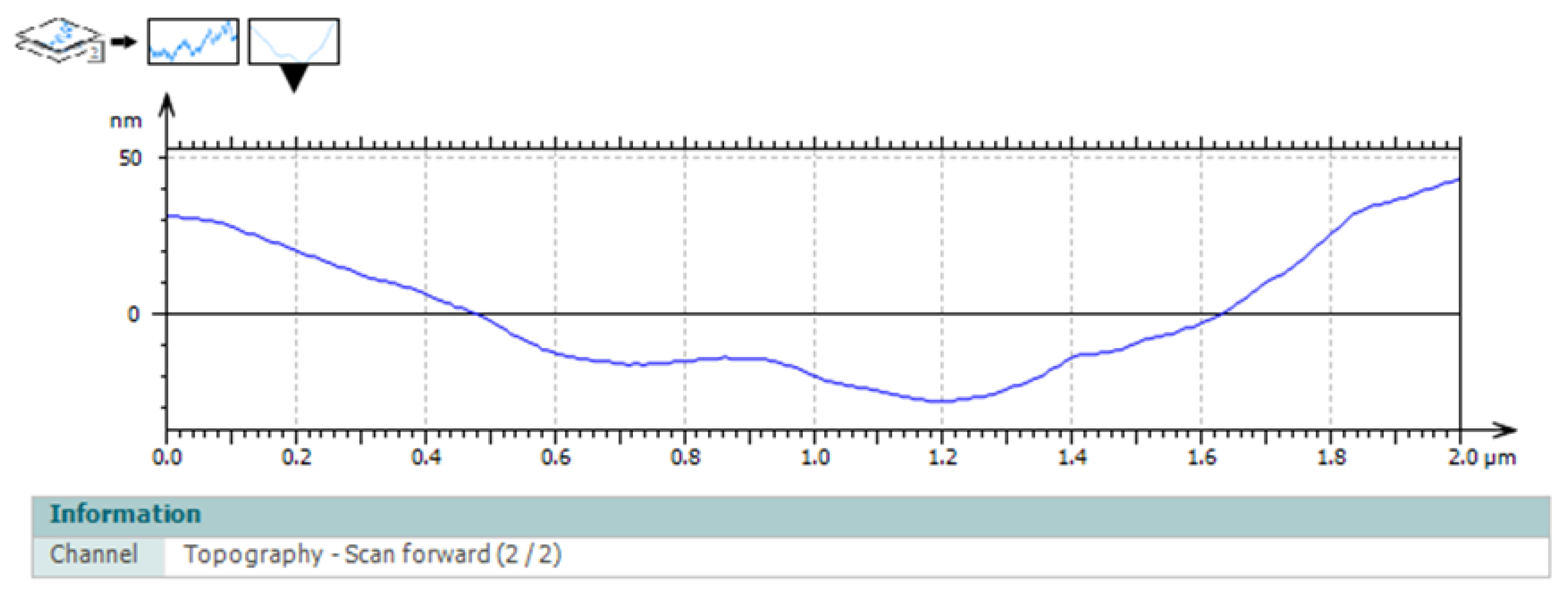

3.6. Surface Profile Analysis

Surface profile analysis extracted from representative regions revealed a central depression flanked by elevated areas. The central region exhibited a lower height profile, while the lateral elevations spatially overlapped with collagen-rich structures displaying increased topographic prominence. The surface profile findings were consistent with the spatial heterogeneity observed in both deflection imaging and topographic maps, illustrating variations in surface organization across the aponeurotic tissue. Height variations occurred smoothly along the profile, without abrupt transitions, further supporting the integrity and organized architecture of the tissue (

Figure 8).

4. Discussion

4.1. Nano-Scale Architecture of Normal Aponeurotic Tissue

The present study provides a detailed nano-scale characterization of human aponeurotic tissue using atomic force microscopy, with a focus on surface morphology, fibrillar organization, and spatial heterogeneity in deflection contrast during contact-mode imaging. By combining deflection imaging with two-dimensional and three-dimensional topographic analysis, the findings offer a high-resolution description of the aponeurotic surface architecture without relying on absolute mechanical measurements.

AFM deflection imaging revealed a well-organized fibrillar surface with a clear preferential orientation, reflecting the collagen-dominated composition of aponeurotic tissue. The elongated and partially parallel structures observed at the micro- and nano-scale correspond to collagen fiber bundles and are indicative of the intrinsic anisotropy of the aponeurosis. This anisotropic organization represents a defining structural feature of dense connective tissues involved in directional force transmission and has been previously documented using histological and biomechanical approaches [

21,

22,

23]. The present results demonstrate that this structural anisotropy is preserved and readily detectable at the nano-scale.

4.2. Spatial Heterogeneity and Deflection Contrast

Pronounced spatial heterogeneity in deflection contrast was observed across the aponeurotic surface. Regions of increased deflection signal spatially overlapped with collagen-dense bundles, whereas lower-intensity regions corresponded to interfibrillar areas. Similar patterns of spatial heterogeneity have been described in AFM studies of collagen-based biological tissues, where local variations in deflection contrast are closely associated with differences in fibrillar density, orientation, and packing [

21,

24]. Importantly, the observed heterogeneity in the present study reflects the normal structural complexity of functional aponeurotic tissue rather than pathological alteration.

Two-dimensional AFM topography demonstrated a continuous, non-porous surface characterized by moderate height variations and smooth transitions between ridges and valleys. The absence of abrupt discontinuities, sharp edges, or well-defined pores suggests preservation of native biological architecture and minimal influence of preparation-related artifacts. Comparable surface continuity has been reported for intact connective tissues and contrasts with the irregular or disrupted patterns described in altered tissue states or in certain mesh–tissue interaction contexts [

4,

15,

18]. The elongated topographic features and their preferential orientation further support the dominant role of collagen fascicles in shaping aponeurotic surface morphology.

4.3. Three-Dimensional Organization and Surface Roughness

Three-dimensional surface reconstruction enhanced visualization of the spatial arrangement of topographic features and further highlighted the anisotropic organization of ridges and valleys. The moderate Z-range observed is consistent with a compact extracellular matrix rather than a granular or degraded structure. Previous AFM investigations have demonstrated that three-dimensional visualization is particularly valuable for identifying directional organization and spatial heterogeneity in fibrous tissues, which may be underestimated in two-dimensional projections alone [

25,

26,

27]. In the case of aponeurotic tissue, this anisotropy underlies its capacity to transmit and redistribute mechanical loads generated by the abdominal musculature.

Quantitative roughness analysis supported the interpretation of a structurally intact and organized surface. Moderate arithmetic mean height (Sa) values, together with higher root mean square roughness (Sq), indicate a non-uniform height distribution with localized variations related to differences in fibrillar density and interfibrillar spacing. Similar roughness profiles have been reported for collagen-based biological surfaces and are considered characteristic of functional fibrous tissues rather than disorganized or pathological matrices [

21,

26,

28]. The Sp/Sv ratio close to unity and the moderate total height (Sy) value indicate the absence of isolated peaks, deep valleys, fissures, or pores, reinforcing the interpretation of a uniform and biologically coherent surface architecture.

Surface profile analysis further revealed smooth height variations with gradual transitions between elevated and depressed regions, corresponding to differences in surface organization observed in the topographic maps. Such profiles are consistent with the composite nature of aponeurotic tissue, in which collagen fibers and extracellular matrix components interact to generate a continuous yet heterogeneous structural arrangement [

29,

30,

31]. Comparable profile characteristics have been described in AFM studies of fascia and tendon [

32].

4.4. Correlation with Microscale Morphology

The nano-scale AFM findings are consistent with the preserved microscale architecture observed by optical microscopy in the present study, which demonstrated parallel collagen fiber bundles, sparse cellularity, and the absence of inflammatory or degenerative changes. Together, these observations support the interpretation that the AFM-derived heterogeneity reflects inherent structural organization rather than processing-related artifacts or pathological remodeling. The integration of optical microscopy and AFM therefore enables a multi-scale structural framework, linking collagen architecture at the microscale with surface morphology and interaction heterogeneity at the nano-scale.

4.5. Clinical Relevance and Implications for Abdominal Wall Reconstruction

From a clinical perspective, defining a nano-scale reference profile for macroscopically normal aponeurotic tissue is highly relevant for abdominal wall reconstruction. Synthetic meshes are implanted in direct contact with the aponeurosis, and their integration depends not only on bulk material properties but also on surface topography and local structural compatibility. Variations in tissue–implant interactions have been associated with excessive fibrosis, increased stiffness, chronic pain, and impaired functional outcomes [

3]. The present findings provide a biological benchmark against which the nano-structural characteristics of prosthetic materials can be compared in future investigations.

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations should be acknowledged. The present analysis was descriptive and did not include absolute mechanical measurements or viscoelastic modeling, and surface characterization was limited to relatively small scan areas, which may not capture all aspects of large-scale tissue heterogeneity. Nevertheless, AFM offers unique insights into local surface organization that complement macroscopic biomechanical testing and conventional histological assessment. Future studies integrating quantitative nanomechanical mapping and comparative analyses with prosthetic materials may further elucidate the mechanobiological basis of tissue–implant interactions in abdominal wall surgery.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that atomic force microscopy provides detailed nano-scale insight into the surface architecture of human aponeurotic tissue. By combining deflection imaging with two-dimensional and three-dimensional topographic analysis, a well-organized fibrillar structure with preferential orientation and moderate surface roughness was identified, consistent with the collagen-dominated composition of functional aponeurosis.

The findings reveal pronounced local heterogeneity in the deflection contrast across the tissue surface, correlated with differences in fibrillar density and interfibrillar organization. This heterogeneity represents a physiological characteristic of aponeurotic tissue rather than a pathological alteration and highlights the composite nature of its extracellular matrix.

Quantitative roughness parameters and surface profile analysis further support the presence of a continuous, non-porous, and structurally intact surface, without features suggestive of degradation or architectural disruption. The anisotropic nano-structural organization observed across multiple imaging modalities underscores the role of aponeurosis in directional force transmission within the abdominal wall.

Collectively, these results establish a nano-scale reference profile for macroscopically normal human aponeurotic tissue. This reference may serve as a baseline for future comparative investigations involving synthetic meshes and contribute to a more refined understanding of tissue–implant interactions in abdominal wall reconstruction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T. and C.D.L.; methodology, A.T. and Ș.L.T.; investigation, A.T., C.A.D.G. and Ș.L.T.; data curation, A.T., B.M.C., B.G. and R.-V.L.; formal analysis, A.T.; writing—original draft preparation, A.T. and A.L.; writing—review and editing, C.D.L., V.B., R.-V.L., C.A.D.G. and Ș.O.G.; supervision, C.D.L., Ș.L.T. and Ș.O.G.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the “Grigore T. Popa” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iași, Romania (approval no. 420/31.03.2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Muysoms, F.E.; Jairam, A.; López-Cano, M.; et al. European Hernia Society guidelines on the closure of abdominal wall incisions. Hernia 2022, 26, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deerenberg, E.B.; Timmermans, L.; Hogerzeil, D.P.; et al. A systematic review of the surgical treatment of large incisional hernia. Hernia 2015, 19, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farr, N.; Novitsky, Y.W.; et al. Mechanobiological mismatch in abdominal wall reconstruction. Ann. Surg. 2023, 278, e202–e210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratzl, P.; Weinkamer, R. Nature’s hierarchical materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2020, 114, 100627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeken, C.R.; Lake, S.P. Mechanical properties of the abdominal wall and biomaterials used for hernia repair. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2017, 74, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, J.W.A.; Luijendijk, R.W.; Hop, W.C.J.; et al. Long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of suture versus mesh repair of incisional hernia. Ann. Surg. 2004, 240, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinge, U.; Klosterhalfen, B. Mesh-related complications after hernia repair: Classification, clinical relevance, and prevention. Hernia 2018, 22, 193–206. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb, W.S.; Warren, J.A.; Ewing, J.A.; Burnikel, A.; Merchant, M.; Carbonell, A.M. Open retromuscular mesh repair: Outcomes and the role of tissue quality. Hernia 2020, 24, 267–275. [Google Scholar]

- Klinge, U.; Klosterhalfen, B. Mesh–tissue interaction and biocompatibility: Definitions, clinical relevance, and future perspectives. Hernia 2012, 16, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, J.D.; Schwartz, M.A.; Tellides, G.; Milewicz, D.M. Role of extracellular matrix in vascular and connective tissue mechanics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 563–583. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, K.L.; Holmes, D.F.; Lu, C.; et al. Molecular orientation and microstructural effects on the mechanical properties of type I collagen fibrils. J. R. Soc. Interface 2018, 15, 20180163. [Google Scholar]

- Holzapfel, G.A.; Ogden, R.W. Biomechanical modelling of soft tissue anisotropy. Proc. R. Soc. A 2020, 476, 20190736. [Google Scholar]

- Pogoda, K.; Janmey, P.A. Biomechanical properties of tissues. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 508–527. [Google Scholar]

- Dufrêne, Y.F.; Ando, T.; Garcia, R.; et al. Atomic force microscopy in biology: New challenges and opportunities. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 667–682. [Google Scholar]

- Schillers, H.; Medalsy, I.; Hu, S.; et al. PeakForce Tapping enables high-resolution nanomechanical mapping of biological samples. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2193, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufrêne, Y.F.; Persat, A. Mechanomicrobiology at the nanoscale using atomic force microscopy. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 649–663. [Google Scholar]

- Sokolov, I.; Iyer, S.; Subba-Rao, V. Local mechanical properties of biological tissues measured by atomic force microscopy. Acta Biomater. 2016, 29, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeken, C.R.; Matthews, B.D. Biomechanical properties of abdominal wall tissues and implications for mesh–tissue interaction. Surg. Endosc. 2012, 26, 2492–2499. [Google Scholar]

- Pogoda, K.; Bucki, R.; Byfield, F.J.; Cruz, K.; Lee, T.; Marcinkiewicz, C.; Janmey, P.A. Soft substrates containing hyaluronan mimic the effects of increased stiffness on morphology, motility, and proliferation of glioma cells. Biomaterials 2017, 128, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, H.-J.; Cappella, B.; Kappl, M. Force measurements with the atomic force microscope: Technique, interpretation and applications. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2005, 59, 1–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handsfield, G.G.; Slane, L.C.; Screen, H.R.C. Nanoscale mechanics and collagen fibril alignment in load-bearing connective tissues. Acta Biomater. 2016, 38, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Screen, H.R.C.; Berkoff, D.J.; Swain, M.V. Mechanical anisotropy of collagenous tissues: From microstructure to function. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 118, 104444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stecco, C.; Macchi, V.; Porzionato, A.; et al. The fascia: The forgotten structure. Ital. J. Anat. Embryol. 2011, 116, 127–138. [Google Scholar]

- Ando, T.; Uchihashi, T.; Kodera, N. High-speed AFM and its application to biomolecular systems. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2014, 43, 373–390. [Google Scholar]

- Lekka, M.; Pogoda, K.; Gostek, J.; et al. Cancer cell mechanics measured by atomic force microscopy. Methods 2012, 60, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, C.J.; Venkataraman, S.; Retterer, S.T.; et al. Mapping the nanomechanical properties of collagen fibrils by atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 2010, 98, 1303–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsteens, D.; Dague, E.; Rouxhet, P.G.; Baulard, A.R.; Dufrêne, Y.F. Nanoscale imaging of biological surfaces using atomic force microscopy. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012, 905, 141–152. [Google Scholar]

- Holsapple, E.; Krishnan, R. Multiscale structure–function relationships in collagenous tissues. Acta Biomater. 2020, 113, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoulders, M.D.; Raines, R.T. Collagen structure and stability. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009, 78, 929–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezakhaniha, R.; Agianniotis, A.; Schrauwen, J.T.C.; et al. Experimental investigation of collagen waviness and orientation in connective tissues. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2020, 19, 1789–1803. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, J.D.; Dufresne, E.R.; Schwartz, M.A. Mechanotransduction and extracellular matrix homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 802–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stylianou, A. Assessing collagen D-band periodicity with atomic force microscopy. Materials 2022, 15, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).