Submitted:

19 December 2025

Posted:

23 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

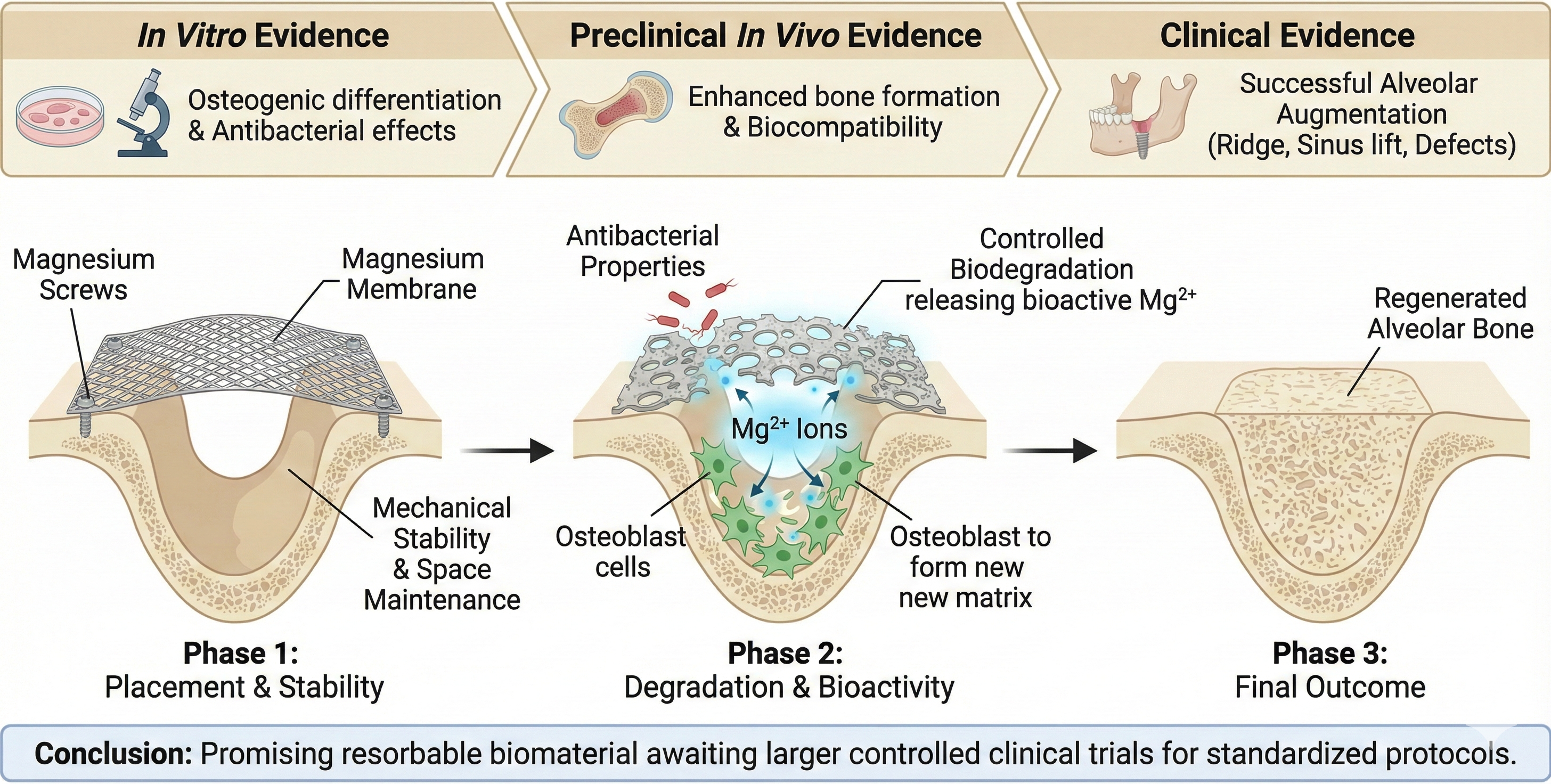

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

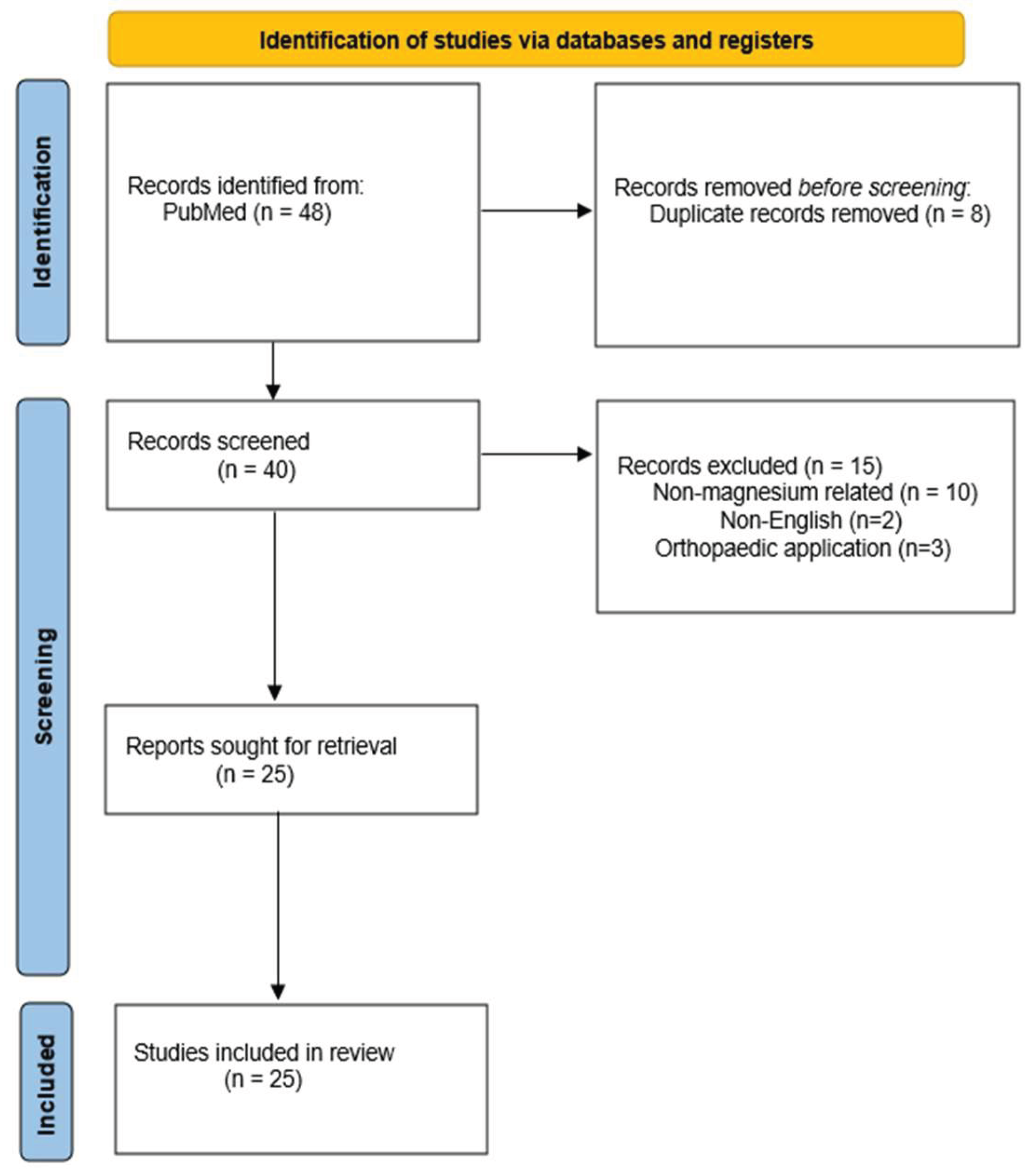

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol Development and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Studies involving the use of magnesium membranes.

- Publications in English.

- Clinical studies, case reports, case series, or preclinical in vivo studies (animal models) relevant to bone regeneration.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Studies not involving magnesium-based membranes.

- Studies focused solely on orthopedic, cardiovascular, or non-alveolar or cortical bone applications.

- Studies lacking relevant outcome measures for bone regeneration or clinical application.

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Selection Process

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Quality Assessment

- Level 1: Systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials.

- Level 2: Cohort studies, low-quality randomized controlled trials.

- Level 3: Case-control studies.

- Level 4: Case series, case reports, and poor-quality cohort/case-control studies.

- Level 5: Expert opinion, mechanism-based reasoning, and clinical guidelines.

2.7. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Evidence Quality Distribution (Oxford CEBM)

3.3. Study Characteristics

Discussion

Mechanical Strength, Handling, and Clinical Advantages

Performance of Magnesium Membranes and Fixation Screws in Bone Regeneration

Biological Activity and Effect of Magnesium Ion Release

Degradation Behavior and the Role of the Corrosion Process

Surface Modifications

Clinical Complications and Healing Outcomes

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GBR | Guided Bone Regeneration |

| e-PTFE | Expanded Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| HGF-1 | Human Gingival Fibroblast 1 |

| Mpa | Megapascal |

| Mg | Magnesium |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| PVD | Physical Vapor Deposition |

| ALP | Alkaline Phosphatase |

| MAO | Micro Arc Oxidation |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| Runx2 | Runt Related Transcription Factor 2 |

| OCN | Osteocalcin |

| COL1 | Collagen Type 1 |

| CBCT | Cone Beam Computed Tomography |

References

- Covani, U.; Giammarinaro, E.; Marconcini, S. Alveolar socket remodeling: The tug-of-war model. Med. Hypotheses 2020, 142, 109746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.G.; Dias, D.R.; Matarazzo, F. Anatomical characteristics of the alveolar process and basal bone that have an effect on socket healing. Periodontol. 2000, 2023(93), 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrotsos, J.A.; Parashis, A.O.; Theofanatos, G.D.; Smulow, J.B. Prevalence and distribution of bone defects in moderate and advanced adult periodontitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1999, 26, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollý, D.; Klein, M.; Mazreku, M.; Zamborský, R.; Polák, Š.; Danišovič, Ľ.; Csöbönyeiová, M. Stem Cells and Their Derivatives—Implications for Alveolar Bone Regeneration: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanauskaite, A.; Becker, K.; Kassira, H.C.; Becker, J.; Sader, R.; Schwarz, F. The dimensions of the facial alveolar bone at tooth sites with local pathologies: a retrospective cone-beam CT analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 1551–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milinkovic, I.; Cordaro, L. Are there specific indications for the different alveolar bone augmentation procedures for implant placement? A systematic review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 43, 606–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benic, G.I.; Hämmerle, C.H.F. Horizontal bone augmentation by means of guided bone regeneration. Periodontol 2000 2014, 66, 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retzepi, M.; Donos, N. Guided Bone Regeneration: biological principle and therapeutic applications. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2010, 21, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, S.; Emery, S.E.; Goldberg, V.M. Factors affecting bone graft incorporation. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1996, 324, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Su, Y.; Kucine, A.J.; Cheng, K.; Zhu, D. Guided Bone Regeneration Using Barrier Membrane in Dental Applications. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 5457–5478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.F.; Yan, X.Z. Periodontal Guided Tissue Regeneration Membranes: Limitations and Possible Solutions for the Bottleneck Analysis. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2023, 29, 532–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Zhao, L.; Huang, C.; Yin, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, P.; Gu, X.; Fan, Y. Recent Advances in the Development of Magnesium-Based Alloy Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR) Membrane. Metals 2022, 12, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rider, P.; Kačarević, Ž.P.; Elad, A.; Tadić, D.; Rothamel, D.; Sauer, G.; Bornert, F.; Windisch, P.; Hangyási, D.B.; Molnar, B.; Bortel, E.; Hesse, B.; Witte, F. Biodegradable magnesium barrier membrane used for guided bone regeneration in dental surgery. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 14, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Ruan, Y.C.; Yu, M.K.; O'Laughlin, M.; Wise, H.; Chen, D.; Tian, L.; Shi, D.; Wang, J.; et al. Implant-derived magnesium induces local neuronal production of CGRP to improve bone-fracture healing in rats. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 1160–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amberg, R.; Elad, A.; Rothamel, D.; Fienitz, T.; Szakacs, G.; Heilmann, S.; Witte, F. Design of a migration assay for human gingival fibroblasts on biodegradable magnesium surfaces. Acta Biomater. 2018, 79, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, B.; Thornton, H. The 2011 Oxford CEBM Levels of Evidence (Introductory Document). Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Available online: https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/ocebm-levels-of-evidence.

- Witte, F. The history of biodegradable magnesium implants: a review. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 1680–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elad, A.; Rider, P.; Rogge, S.; Witte, F.; Tadić, D.; Kačarević, Ž.P.; Steigmann, L. Application of Biodegradable Magnesium Membrane Shield Technique for Immediate Dentoalveolar Bone Regeneration. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frosecchi, M. Horizontal and Vertical Defect Management with a Novel Degradable Pure Magnesium Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR) Membrane-A Clinical Case. Medicina 2023, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palkovics, D.; Rider, P.; Rogge, S.; Kačarević, Ž.P.; Windisch, P. Possible Applications for a Biodegradable Magnesium Membrane in Alveolar Ridge Augmentation-Retrospective Case Report with Two Years of Follow-Up. Medicina 2023, 59, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, T.; Korzinskas, T. Guided Bone Regeneration in the Posterior Mandible Using a Resorbable Metal Magnesium Membrane and Fixation Screws: A Case Report. Case Rep. Dent. 2024, 2024, 2659893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaushu, G.; Reiser, V.; Rosenfeld, E.; Masri, D.; Chaushu, L.; Čandrlić, M.; Rider, P.; Kačarević, Ž.P. Use of a Resorbable Magnesium Membrane for Bone Regeneration After Large Radicular Cyst Removal: A Clinical Case Report. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elad, A.; Pul, L.; Rider, P.; Rogge, S.; Witte, F.; Tadić, D.; Mijiritsky, E.; Kačarević, Ž.P.; Steigmann, L. Resorbable magnesium metal membrane for sinus lift procedures: a case series. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Z.; Peng, B.; Ye, Y.; Xu, H.; Cai, X.; Liu, J.; Dai, J.; Bian, Y.; Wen, P.; Weng, X. Bolstered bone regeneration by multiscale customized magnesium scaffolds with hierarchical structures and tempered degradation. Bioact. Mater. 2025, 46, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hangyasi, D.B.; Körtvélyessy, G.; Blašković, M.; Rider, P.; Rogge, S.; Siber, S.; Kačarević, Ž.P.; Čandrlić, M. Regeneration of Intrabony Defects Using a Novel Magnesium Membrane. Medicina 2023, 59, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rider, P.; Kačarević, Ž.P.; Elad, A.; Rothamel, D.; Sauer, G.; Bornert, F.; Windisch, P.; Hangyási, D.; Molnar, B.; Hesse, B.; et al. Biodegradation of a Magnesium Alloy Fixation Screw Used in a Guided Bone Regeneration Model in Beagle Dogs. Materials 2022, 15, 4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blašković, M.; Butorac Prpić, I.; Aslan, S.; Gabrić, D.; Blašković, D.; Cvijanović Peloza, O.; Čandrlić, M.; Perić Kačarević, Ž. Magnesium Membrane Shield Technique for Alveolar Ridge Preservation: Step-by-Step Representative Case Report of Buccal Bone Wall Dehiscence with Clinical and Histological Evaluations. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blašković, M.; Butorac Prpić, I.; Blašković, D.; Rider, P.; Tomas, M.; Čandrlić, S.; Botond Hangyasi, D.; Čandrlić, M.; Perić Kačarević, Ž. Guided Bone Regeneration Using a Novel Magnesium Membrane: A Literature Review and a Report of Two Cases in Humans. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felice, P.; Lizio, G.; Marchetti, C.; Checchi, L.; Scarano, A. Magnesium-substituted hydroxyapatite grafting using the vertical inlay technique. Int. J. Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2013, 33, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.C.; Chaya, A.; Liu, K.; Verdelis, K.; Sfeir, C. The role of magnesium ions in bone regeneration involves the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. Acta Biomater. 2019, 98, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Chen, J.; Schmidt, F.; Dai, J.; Li, J.; Xu, S.; Li, A.; Yu, Z.; Witte, F. Magnesium-based barrier membrane for guided bone regeneration: From bedside to bench and back again. Biomaterials 2025, 328, 123783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Gong, N.; Wang, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhao, S.; Liu, Y.; Tan, F. Impact of Strontium, Magnesium, and Zinc Ions on the In Vitro Osteogenesis of Maxillary Sinus Membrane Stem Cells. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2025, 203, 1922–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malaiappan, S.; Harris, J. Osteogenic Potential of Magnesium Oxide Nanoparticles in Bone Regeneration: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e55502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rider, P.; Perić Kačarević, Ž.; Elad, A.; Rothamel, D.; Sauer, G.; Bornert, F.; Windisch, P.; Hangyási, D.; Molnar, B.; Hesse, B.; et al. Analysis of a Pure Magnesium Membrane Degradation Process and Its Functionality When Used in a Guided Bone Regeneration Model in Beagle Dogs. Materials 2022, 15, 3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbeck, M.; Kühnel, L.; Witte, F.; Pissarek, J.; Precht, C.; Xiong, X.; Krastev, R.; Wegner, N.; Walther, F.; Jung, O. Degradation, Bone Regeneration and Tissue Response of an Innovative Volume Stable Magnesium-Supported GBR/GTR Barrier Membrane. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, V.; Virtanen, S.; Boccaccini, A.R. Surface Treatment With Cell Culture Medium: A Biomimetic Approach to Enhance the Resistance to Biocorrosion in Mg and Mg-Based Alloys—A Review. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2025, 113, e35617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steigmann, L.; Jung, O.; Kieferle, W.; Stojanovic, S.; Proehl, A.; Görke, O.; Emmert, S.; Najman, S.; Barbeck, M.; Rothamel, D. Biocompatibility and Immune Response of a Newly Developed Volume-Stable Magnesium-Based Barrier Membrane in Combination with a PVD Coating for Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR). Biomedicines 2020, 8, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Xu, Y.; Kolawole, S.K.; Wen, L.; Qi, Z.; Xu, W.; Chen, J. Degradable Pure Magnesium Used as a Barrier Film for Oral Bone Regeneration. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabanella, G.; Rider, P.; Rogge, S.; Čandrlić, M.; Perić Kačarević, Ž. Open Wound Healing in Guided Bone Regeneration Using a Magnesium Membrane: A Paradigm Shift. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2025, 113, e35642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, A.S.; Correia, A.; Esteves, A.C. Bacterial collagenases—A review. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 42, 106–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Electronic database | Search term |

|---|---|

| PubMed | “Magnesium membrane for bone augmentation”, “NOVAMag membrane”, “Magnesium”. |

| Author | Title | Type of study | CEBM level | Sample size | Key findings | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barbeck et al. (2020) [36] | Tissue Response of an Innovative Volume Stable Magnesium-Supported GBR/GTR Barrier Membrane | Original research in vivo |

5 | The study found that the magnesium-supported barrier membrane gradually degraded as intended, while simultaneously promoting bone regeneration beneath the membrane. Tissue response was favorable, with soft tissue healing occurring without excessive inflammation or adverse reactions. The membrane-maintained volume stability during the critical early healing phase, providing structural support while allowing controlled resorption, demonstrating a balance between mechanical integrity and bioresorbability. | The authors concluded that this innovative magnesium-based GBR/GTR* membrane shows significant promise for bone and tissue regeneration applications. Its combination of volume stability, controlled degradation, promotion of bone formation, and biocompatible tissue response suggests potential for future clinical translation. They emphasize that further studies, including larger animal models and eventual human trials, are needed to confirm its safety and effectiveness in clinical settings. | |

| Rider et al. (2021) [13] | Biodegradable magnesium barrier membrane used for guided bone regeneration in dental surgery |

Original research in vivo | 4 | 20 | A pure magnesium membrane effectively maintained barrier function and space during the early healing phase of guided bone regeneration, separating bone from soft tissue and retaining graft material. As it corroded, a protective corrosion layer and gas cavities extended its functional lifespan, and the membrane was gradually resorbed and replaced by new bone. Healing and tissue regeneration were comparable to resorbable collagen membranes, with no adverse tissue reactions observed. | biodegradable pure magnesium membranes possess all the necessary mechanical and biological properties for optimal GBR outcomes, demonstrating comparable efficacy and safety to conventional collagen membranes |

| Rider et al. (2022) [35] | Analysis of a Pure Magnesium Membrane Degradation Process and Its Functionality When Used in a Guided Bone Regeneration Model in Beagle Dogs |

Original research in vivo |

5 | 18 | Micro-CT** analysis showed that new bone formation under the magnesium membrane was comparable to that under collagen membranes at all time points. The magnesium membrane degraded most rapidly between weeks 1 and 8 and was nearly fully corroded by week 16. Early voids, likely from hydrogen gas release, and transient soft tissue reactions resolved over time without affecting bone regeneration, and no chronic inflammation or systemic adverse events were observed. | The authors conclude that the pure magnesium membrane is a viable, functional, and safe barrier membrane for GBR. It offers mechanical stability, degrades in a controlled manner over time, and yields bone regeneration outcomes comparable to those achieved with conventional collagen membranes, thus representing a promising alternative for GBR treatments. |

| Rider et al. (2022) [27] | Biodegradation of a Magnesium Alloy Fixation Screw Used in a Guided Bone Regeneration Model in Beagle Dogs |

Original research in vivo |

5 | 20 | Bone regeneration was similar between the magnesium and titanium groups, with no significant differences in new bone volume or soft tissue formation. The magnesium screws degraded gradually over time, with nearly complete resorption by 52 weeks. Early swelling and transient inflammation were observed in the magnesium group, and small voids from gas release occurred, but neither interfered with bone healing. By the end of the study, the regenerated bone quality and volume were comparable between groups. | Magnesium-alloy fixation screws provide sufficient stability for guided bone regeneration while gradually resorbing, eliminating the need for screw removal surgery. They represent a promising, resorbable alternative to titanium screws without compromising bone healing outcomes. |

| Amberg et al. (2018) [15] | Design of a migration assay for human gingival fibroblasts on biodegradable magnesium surfaces | In vitro study | 5 | The authors successfully established a reproducible migration assay adapted for magnesium biomaterials. They demonstrated that human gingival fibroblasts can attach to and migrate on biodegradable magnesium substrates, and that the assay allows quantitative evaluation of these behaviors. | The study concludes that the developed assay is a feasible and useful tool for systematically assessing cell–biomaterial interactions on magnesium surfaces, supporting future research and optimization of magnesium-based materials for dental and implant applications. | |

| Zhang et al. (2025) [33] | Impact of Strontium, Magnesium, and Zinc Ions on the In Vitro Osteogenesis of Maxillary Sinus Membrane Stem Cells |

in vitro study |

5 | Under osteogenic induction, moderate Mg+ concentrations enhanced sinus membrane stem cell differentiation, evidenced by increased ALP++ activity and staining, upregulated bone-related gene expression, greater osteocalcin production, and enhanced calcium nodule formation. However, higher Mg²⁺ levels reduced cell viability and osteogenic differentiation, indicating a concentration-dependent effect where excess magnesium can be detrimental. | Magnesium ions at an optimal concentration (1 mM in this study) significantly promote proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of human maxillary sinus membrane stem cells, boosting markers of bone formation (ALP, osteocalcin, mineral nodules). This suggests that Mg²⁺ has strong potential as a bioactive ion to enhance bone regeneration in sinus floor augmentation procedures | |

| Steigmann et al. (2020) [38] | Biocompatibility and Immune Response of a Newly Developed Volume-Stable Magnesium-Based Barrier Membrane in Combination with a PVD Coating for Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR) |

Preclinical in vivo and in vitro research | 5 | In vitro, both uncoated and PVD# -coated magnesium membranes showed poor cytocompatibility, with low cell viability and corrosion-related gas formation. In vivo, however, both membranes demonstrated acceptable biocompatibility, with tissue integration and healing comparable to collagen controls. The PVD coating did not reduce gas formation and was associated with fewer anti-inflammatory (M2) macrophages, suggesting a less favorable immune response, whereas the uncoated Mg membrane elicited an immune response similar to collagen, indicating satisfactory in vivo compatibility despite degradation. | The authors conclude that pure magnesium membranes (uncoated) represent a promising resorbable, volume-stable alternative to non-resorbable barrier materials for GBR/GTR therapy, as they meet biocompatibility and immune-response criteria comparable to established collagen membranes. The PVD-coated version, however, did not improve, and may even impair, tissue compatibility due to increased inflammatory response and persistent gas cavity formation, so the coating strategy in this case does not appear beneficial. | |

| Shan et al. (2022) [39] | Degradable Pure Magnesium Used as a Barrier Film for Oral Bone Regeneration |

preclinical in vivo and in vitro research |

5 | The MAO## coating slowed magnesium degradation, supported osteoblast viability and differentiation, and maintained structural stability. In rabbits, defects covered with MAO-Mg showed significantly more new bone formation than controls, comparable to titanium membranes by 8 weeks. | MAO-coated magnesium membranes are biocompatible, degrade at a controlled rate, and effectively support bone regeneration, offering a promising alternative to conventional barrier membranes without requiring removal. | |

| Lv et al. (2025) [25] | Bolstered bone regeneration by multiscale customized magnesium scaffolds with hierarchical structures and tempered degradation |

Preclinical in vivo and in vitro research | 5 | The scaffold maintained mechanical strength comparable to cancellous bone while supporting cell adhesion, proliferation, and osteogenic differentiation. In vivo, it promoted significantly more bone formation and bone mineral density than uncoated scaffolds, with controlled degradation preserving structural support during healing. | The multiscale, coated magnesium scaffold enables customizable, mechanically robust, and biologically active bone regeneration, making it a promising material for next-generation bone defect repair. | |

| Witte et al. (2010) [18] | The history of biodegradable magnesium implants: a review | Narrative review | 5 | The review outlines the historical development of magnesium-based implants, highlighting their biological and mechanical properties, as well as challenges such as corrosion, biocompatibility, and mechanical strength. It summarizes advances like alloying and surface treatments that address these issues. Evidence from in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrates benefits including biodegradability, biocompatibility, and avoidance of long-term foreign-body presence, while noting limitations that require further research. | The authors conclude that biodegradable magnesium implants hold promise as an alternative to permanent metallic implants, particularly in applications where gradual degradation and eventual replacement by natural tissue is desirable. However, they emphasize that further research, especially long-term in vivo and clinical studies, is needed to fully validate the safety, performance, and optimal design of magnesium-based implants before widespread clinical adoption. | |

| Chen et al (2022) [12] | Recent Advances in the Development of Magnesium-Based Alloy Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR) Membrane | Narrative review | 5 | The review outlines the advantages of magnesium-based membranes, including high mechanical strength, biodegradability, osteogenic stimulation, and antibacterial effects. It also identifies major limitations: rapid corrosion, hydrogen gas release, and stress-corrosion susceptibility, and describes strategies such as alloying and surface modification aimed at controlling degradation and improving performance. | The authors conclude that magnesium-based alloy membranes are promising next-generation GBR materials because they combine stability with bioactivity. However, achieving controlled and predictable degradation remains the primary challenge, requiring further materials-engineering research before widespread clinical adoption is feasible. | |

| Khalil et al. (2025) [37] | Surface Treatment With Cell Culture Medium: A Biomimetic Approach to Enhance the Resistance to Biocorrosion in Mg and Mg-Based Alloys-A Review | Narrative review | 5 | The review highlights that immersion in DMEM^ forms calcium phosphate–rich protective layers on Mg-based implants, enhancing corrosion resistance and supporting bone-like environments. Unlike synthetic buffers, which accelerate corrosion, and protein-rich media, which risk contamination, DMEM promotes hydroxyapatite crystallization and calcium phosphate deposition through electrostatic interactions and functionalized layers. Controlled fluid dynamics are important for layer stability, but long-term mechanical performance and in vivo effects such as immune responses and enzymatic activity remain unclear. | The authors conclude that DMEM-based biomimetic surface treatments represent a promising strategy to modulate the degradation behavior of Mg and Mg alloys for orthopedic applications. While these methods improve corrosion resistance and better replicate physiological conditions, further research is needed to evaluate long-term performance, mechanical stability, and behavior under realistic in vivo conditions before clinical translation. | |

| Li et al. (2025) [32] | Magnesium-based barrier membrane for guided bone regeneration: From bedside to bench and back again | Narrative review | 5 | Mg-based membranes demonstrate material properties that align with the clinical principles of GBR (PASS: primary wound closure, angiogenesis, space maintenance, stability). They provide an optimal balance between promoting bone regeneration and preventing bacterial infiltration, enhance clinical safety for less experienced surgeons, and may improve outcomes even in complications such as wound dehiscence. Their application has expanded beyond traditional GBR to broader clinical cases. | The review concludes that Mg-based barrier membranes hold substantial promise for regenerative dentistry and medicine. Continuous innovation and interdisciplinary research are essential to advance their clinical adoption, and successful translation from concept to practice highlights the potential of Mg-based materials to improve clinical outcomes and simplify dental procedures. | |

| Malaiappan et al. (2025) [34] | Osteogenic Potential of Magnesium Oxide Nanoparticles in Bone Regeneration: A Systematic Review |

Systematic review | 5 | The review of seven studies found that magnesium oxide nanoparticles enhance osteoblast proliferation, differentiation, and mineralization in vitro, increasing ALP activity and upregulating osteogenic genes such as Runx2^^, OCN×, and COL1××. In vivo, Magnesium oxide-containing scaffolds or coatings promoted new bone formation, increased bone density, and improved implant integration, demonstrating their bioactive role in stimulating bone regeneration. | The authors conclude that magnesium oxide nanoparticles have significant osteogenic potential and can enhance bone regeneration when incorporated into scaffolds, coatings, or graft materials. They highlight that while preclinical evidence is promising, further well-designed in vivo and clinical studies are needed to determine optimal dosages, long-term safety, and translational applicability. | |

| Blaskovic et al. (2023) [29] | Guided Bone Regeneration Using a Novel Magnesium Membrane: A Literature Review and a Report of Two Cases in Humans |

Literature review and clinical cases | 4 | 2 | literature shows that magnesium membranes offer favorable properties for guided bone regeneration, including mechanical strength, biocompatibility, degradability, and effective barrier function. In two human cases, the membranes were successfully shaped and fixed, graft material remained stable, and healing occurred without complications or adverse reactions. Radiographic follow-up confirmed satisfactory bone regeneration, with complete resorption of the membranes and screws. | The authors conclude that pure magnesium membranes with resorbable magnesium screws are promising biomaterials for GBR in humans. Their mechanical properties, degradability, handling ease, and successful clinical outcomes in the two cases support their use as viable alternatives to conventional membranes |

| Felice et al. (2013) [30] | Magnesium-substituted hydroxyapatite grafting using the vertical inlay technique |

Clinical case | 4 | 1 | After three months, vertical bone gain of 4.9 mm was achieved at implant placement. Histology showed that the grafted Mg-HA material was fully infiltrated by new bone, demonstrating integration into living tissue. Implants were restored with provisional and definitive prostheses at four and eight months, respectively, without complications. | The authors conclude that Mg-substituted hydroxyapatite, when used in a vertical inlay grafting procedure, can effectively support bone regeneration in severely atrophic posterior mandibles. The graft provided sufficient vertical augmentation and was integrated into newly formed bone, making it a viable grafting material in such challenging cases |

| Frossechi et al. (2023) [20] | Horizontal and Vertical Defect Management with a Novel Degradable Pure Magnesium Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR) Membrane-A Clinical Case |

Clinical case | 4 | 1 | Following extraction of an impacted canine and adjacent tooth, a complex horizontal and vertical defect was augmented with bovine bone graft, covered by a bent magnesium membrane forming a supportive “arch,” and a collagen membrane for soft tissue closure. Over eight months, the grafted volume was well maintained, healing occurred without soft tissue complications, and the magnesium membrane was fully resorbed. Two dental implants were successfully placed into the regenerated bone. | The authors conclude that the biodegradable magnesium membrane, when combined with a collagen pericardium membrane, may offer a viable, fully resorbable alternative to traditional non-resorbable titanium meshes or titanium-reinforced membranes in treating complex alveolar defects with both horizontal and vertical components. |

| Franke et al. (2024) [22] | Guided Bone Regeneration in the Posterior Mandible Using a Resorbable Metal Magnesium Membrane and Fixation Screws: A Case Report |

Clinical case | 5 | 1 | The membrane supported bone graft consolidation, and at 3 months, sufficient bone volume and quality were observed for implant placement. The membrane fully resorbed, and the augmented site healed without complications, despite minor transient soft-tissue effects. | Resorbable magnesium membranes with fixation screws can effectively support bone regeneration in large posterior mandibular defects, providing stability and eliminating the need for a second surgery, though further clinical studies are needed. |

| Blaskovic et al. (2024) [28] | Magnesium Membrane Shield Technique for Alveolar Ridge Preservation: Step-by-Step Representative Case Report of Buccal Bone Wall Dehiscence with Clinical and Histological Evaluations | Clinical case | 4 | 1 | After six months, sufficient bone volume allowed implant placement. Histology showed ~47% new bone, ~19% residual graft, and no inflammation, with active remodeling at the bone-biomaterial interface. Soft tissue healed well, and the final restoration achieved good esthetic and functional outcomes. | The magnesium membrane shield technique effectively supports alveolar ridge preservation in severe buccal defects, promoting bone regeneration and maturation without requiring membrane removal. |

| Chaushu et al. (2025) [23] | Use of a Resorbable Magnesium Membrane for Bone Regeneration After Large Radicular Cyst Removal: A Clinical Case Report |

Clinical case | 4 | 1 | At 16 months post-treatment, CBCT† imaging showed significant bone regeneration: the palatal bone wall contour was restored and well-corticated, indicating new cortical bone formation. Clinically, the treated teeth remained asymptomatic, with normal mobility and healthy soft-tissue healing. The magnesium membrane provided structural support bridging the bony discontinuity, supported graft stability, and being resorbable, eliminated the need for membrane removal surgery | The authors conclude that using a resorbable magnesium membrane in GBR after large cyst removal can be a promising strategy for restoring bone in large periapical defects, combining mechanical strength with complete resorption, though larger studies are needed to verify long-term outcomes and generalizability. |

| Palkovics et al. (2023) [21] | Possible Applications for a Biodegradable Magnesium Membrane in Alveolar Ridge Augmentation–Retrospective Case Report with Two Years of Follow-Up |

Retrospective case report | 4 | 2 | In Case #1, alveolar ridge augmentation with the magnesium membrane achieved a volumetric bone gain of 0.12 cm³, while Case #2 showed a gain of 0.36 cm³, with both horizontal and vertical improvements. At two-year follow-up, hard tissue volume remained stable with no peri-implant bone loss. The membrane’s rigidity supported space maintenance and bone regeneration in defects that would be challenging for conventional resorbable collagen membranes. | The authors conclude that the use of a rigid, resorbable magnesium membrane for alveolar ridge augmentation appears promising: in these two cases, successful bone gain and stable long-term hard tissue outcomes were achieved without the need for membrane removal |

| Elad et al. (2023) [19] | Application of Biodegradable Magnesium Membrane Shield Technique for Immediate Dentoalveolar Bone Regeneration |

Case series | 4 | 4 | All cases demonstrated successful bone regeneration and soft-tissue healing, with follow-up imaging showing thick cortical bone formation in some sites. The membrane was adaptable to defect shape and could be applied as a single or double layer for mechanical support. Its biodegradable nature eliminated the need for secondary removal surgery. | The magnesium membrane shield technique proved to be a viable method for immediate dentoalveolar bone regeneration |

| Elad et al. (2023) [24] | Resorbable magnesium metal membrane for sinus lift procedures: a case series |

Case series | 4 | 4 | In all four cases, the magnesium membrane was used to repair or replace the sinus membrane and support bone grafts in the sinus cavity. Healing resulted in newly formed alveolar bone with height gains of 10-20 mm, and the magnesium membrane was fully resorbed. Vertical and horizontal bone augmentation remained stable, providing sufficient regenerated bone to support dental implants. | The authors conclude that, within the limits of this small case series, a resorbable magnesium membrane can be a viable material for sinus-lift procedures and repair of Schneiderian membrane perforations. The results show successful healing, effective new bone formation, and reliable separation between the oral cavity and maxillary sinus, suggesting that magnesium membranes may offer a promising alternative to conventional resorbable membranes or non-resorbable materials for sinus augmentation |

| Hangyasi et al. (2023) [26] | Regeneration of Intrabony Defects Using a Novel Magnesium Membrane |

Case series | 4 | 3 | In all three cases, the magnesium membrane could be easily shaped into customized forms (strip, T-shape, M-shape) to adapt to the specific morphology of each intrabony defect. After 4-6 months of healing, radiological analysis demonstrated bone regeneration and periodontal probing depth (PPD) reduction by an average of 1.66 ± 0.29 mm, indicating a gain in bone support. Soft-tissue healing was favorable, and no major complications were reported during the healing period. | The authors conclude that the use of a resorbable magnesium membrane represents a viable and promising approach for the treatment of intrabony periodontal defects, offering the benefits of mechanical stability, ease of shaping, effective bone regeneration, and satisfactory functional and esthetic outcomes |

| Tabanella et al. (2025) [40] |

Open Wound Healing in Guided Bone Regeneration Using a Magnesium Membrane: A Paradigm Shift |

Case series | 4 | 4 | Despite membrane exposure in all cases, from small to large, none of the patients experienced pain, infection, or other clinical complications. Implant placement was carried out as planned, and importantly, there was no significant bone loss observed despite exposure. The resorbable magnesium membrane maintained its barrier function and preserved the augmented bone volume, even under open-wound healing conditions. | The authors propose that using a magnesium membrane for GBR may allow for a “paradigm shift” in how wound exposures and dehiscences are managed, membrane exposure does not necessarily lead to failure or bone loss. They suggest the magnesium membrane’s resilience and resorbable nature can make open-wound healing a viable outcome rather than a complication, though they note that larger studies are needed to confirm these findings. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).