Background

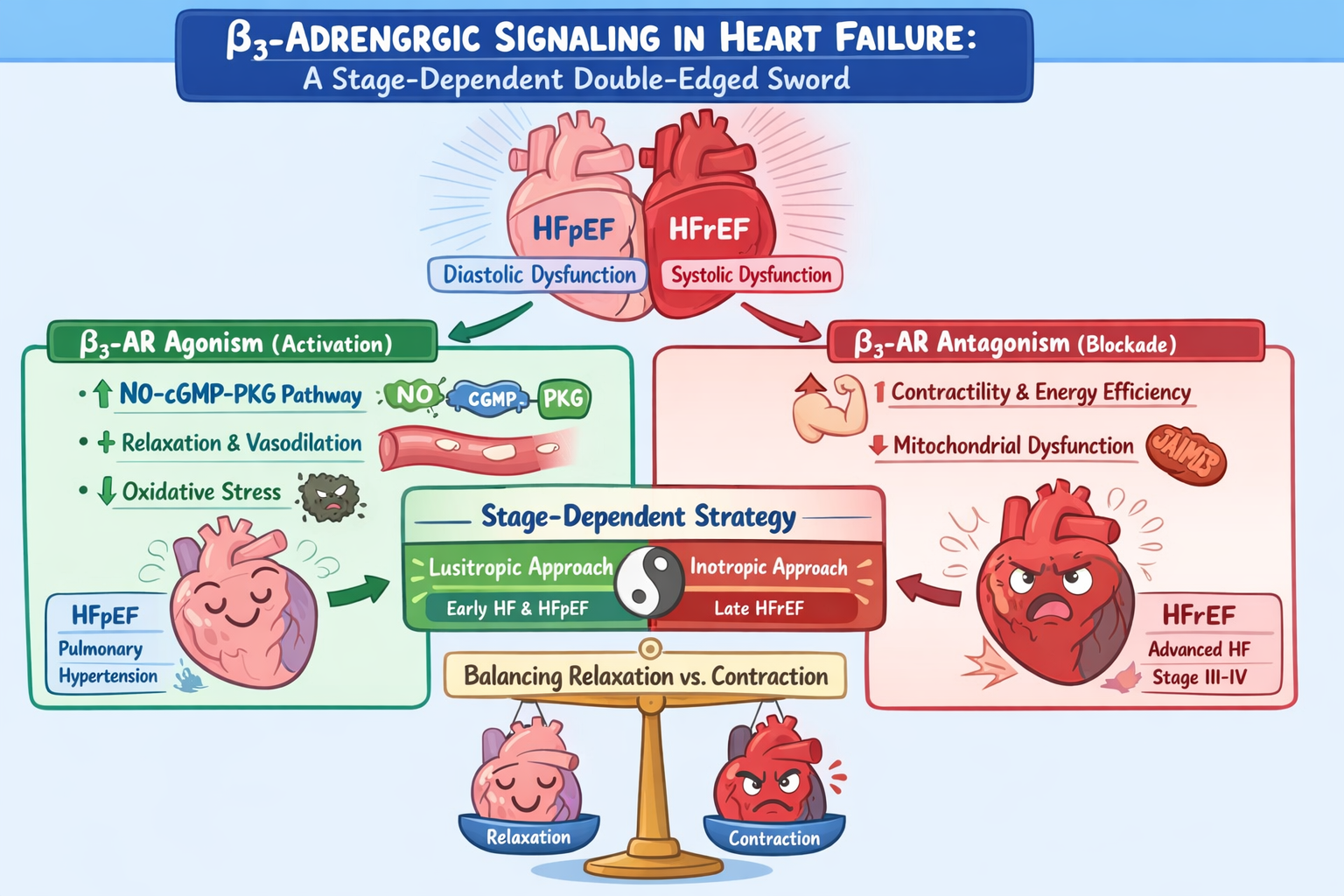

Heart failure (HF) is a heterogeneous clinical syndrome in which the relative contributions of impaired myocardial relaxation, reduced contractile performance, and maladaptive neurohormonal activation vary across disease phenotypes and stages. While reduced systolic function and low cardiac output dominate advanced heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), abnormalities of ventricular relaxation, compliance, and filling pressures are the principal determinants of symptoms in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) and in earlier or compensated stages of disease. These pathophysiological distinctions have important therapeutic implications, particularly with respect to the differential roles of lusitropic and inotropic interventions1.

Lusitropy refers to the ability of the myocardium to relax efficiently during diastole, a process that is critically dependent on coordinated calcium reuptake into the sarcoplasmic reticulum, reduced myofilament calcium sensitivity, and favorable ventricular–arterial coupling. In HFpEF and related phenotypes, impaired lusitropy leads to elevated diastolic filling pressures despite preserved systolic ejection fraction, resulting in pulmonary or systemic congestion, exercise intolerance, and reduced cardiac reserve. In these settings, therapies that enhance myocardial relaxation can improve ventricular filling at lower pressures and augment stroke volume without increasing contractile force or myocardial oxygen consumption. Importantly, many lusitropic mechanisms operate through nitric oxide (NO)–cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)–protein kinase G (PKG) signaling, which not only facilitates diastolic relaxation but also reduces myocardial stiffness, oxidative stress, and pathological remodeling2.

However, lusitropic signaling pathways are often associated with a mild and context-dependent negative inotropic effect. By reducing calcium sensitivity of the contractile apparatus and limiting excessive intracellular calcium accumulation, these pathways can modestly attenuate peak systolic force generation. In early or compensated heart failure states, this effect is generally protective, as it counterbalances chronic sympathetic overstimulation, reduces energetic demand, and mitigates catecholamine-induced myocardial injury. In contrast, in advanced HFrEF characterized by severely impaired contractile reserve and low cardiac output, even modest negative inotropy may further compromise forward flow and exacerbate end-organ hypoperfusion3.

Inotropic therapies, by contrast, directly enhance myocardial contractility through increased calcium availability, calcium sensitivity, or actin–myosin cross-bridge cycling. These interventions are most effective in advanced systolic heart failure, acute decompensated states, or cardiogenic shock, where the dominant physiological deficit is insufficient force generation rather than impaired relaxation. While inotropes can provide rapid hemodynamic improvement, their benefits are offset by increased myocardial oxygen consumption, arrhythmogenic potential, and adverse long-term outcomes, underscoring the need for careful patient selection and limited duration of use4.

The distinction between lusitropic and inotropic strategies therefore reflects a broader principle in heart failure management: therapies must be matched to the dominant physiological abnormality and disease stage. Interventions that enhance relaxation and reduce filling pressures are most effective when diastolic dysfunction predominates, whereas augmentation of contractility becomes necessary only when systolic failure and low output emerge as the primary drivers of clinical deterioration. This stage-dependent framework is particularly relevant to emerging therapies targeting the β₃-adrenergic receptor, whose signaling pathways intersect both lusitropic and inotropic domains. Understanding the nuanced balance between these effects is essential for defining the therapeutic potential and limitations of β₃-adrenergic modulation in heart failure and related cardiopulmonary disorders.

β₃-Adrenergic Receptor Blockade: Reversal of Contractile Depression and Energetic Failure

While β₃-AR activation may be adaptive in early disease states, accumulating evidence suggests that sustained or excessive β₃-AR signaling becomes maladaptive in advanced heart failure. Persistent activation of NO pathways—particularly through inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS)—can lead to excessive nitric oxide production, impaired excitation–contraction coupling, mitochondrial dysfunction, and depression of myocardial contractility. In this context, β₃-ARs may contribute directly to systolic dysfunction and reduced cardiac reserve 9.

Preclinical studies using the selective β₃-AR antagonist SR59230A have provided strong support for this concept. In rodent models of chronic heart failure, β₃-AR blockade resulted in improved left ventricular systolic performance, reduced ventricular dilation, and attenuation of maladaptive hypertrophy. Mechanistically, these benefits were linked to normalization of mitochondrial function, reduced expression of uncoupling protein-2 (UCP-2), preservation of myocardial ATP levels, and suppression of oxidative and nitrosative stress. Importantly, β₃-AR blockade restored β-adrenergic responsiveness without increasing heart rate or myocardial oxygen demand, distinguishing it from traditional inotropic therapies 10.

The detrimental role of excessive β₃-AR signaling is further highlighted in inflammatory and stress-related cardiac dysfunction. In endotoxin-induced acute heart failure models, β₃-AR blockade significantly reduced mortality and preserved systolic function. These effects were attributed to suppression of iNOS expression, reduction of pathological NO overproduction, and stabilization of myocardial energy metabolism. Such findings emphasize the contribution of β₃-AR–mediated signaling to inflammatory cardiac depression and identify receptor blockade as a potential protective strategy in severe systemic illness11.

Translational efforts have led to the development of highly selective β₃-AR antagonists such as APD418, designed as “cardiac myotropes.” In animal models and early human studies, short-term intravenous infusion of APD418 improved left ventricular systolic function and ejection fraction without inducing tachycardia or hypotension. Although a phase-2 clinical trial was terminated for non-scientific reasons and definitive clinical outcomes remain unavailable, these results provide proof-of-concept that β₃-AR blockade can enhance myocardial performance while avoiding the hemodynamic penalties of conventional inotropes12.

Physiologic Stage dependent β₃-modulation in heart failure

Collectively, these observations support a stage-dependent and physiology-guided model of β₃-adrenergic modulation in heart failure. β₃-AR agonism aligns with clinical scenarios in which impaired relaxation and elevated filling pressures predominate, providing lusitropic benefit with mild, protective negative inotropy. Conversely, β₃-AR antagonism appears most advantageous in advanced systolic heart failure, where suppression of inhibitory β₃ signaling can unmask contractile reserve and improve cardiac output without the deleterious effects associated with traditional inotropes. Understanding this duality is essential for the rational integration of β₃-targeted therapies into future heart failure treatment paradigms13.

Conclusion

Heart failure represents a spectrum of pathophysiological states in which impaired myocardial relaxation and reduced contractile reserve contribute variably according to disease phenotype and stage. Therapeutic strategies must therefore be aligned with the dominant physiological abnormality rather than applied uniformly. Lusitropic interventions are most effective when diastolic dysfunction, ventricular stiffness, and elevated filling pressures predominate, whereas inotropic support is required in advanced systolic heart failure characterized by low cardiac output. β₃-adrenergic receptors occupy a unique position at the intersection of these domains. β₃-AR agonism activates nitric oxide–dependent signaling pathways that enhance myocardial relaxation, reduce oxidative stress, and limit maladaptive remodeling, providing benefit in early heart failure, HFpEF, and pulmonary hypertension, where mild negative inotropy is largely protective. In contrast, sustained β₃-AR activation in advanced HFrEF may contribute to contractile depression and energetic inefficiency. In this setting, selective β₃-AR antagonism emerges as a novel inotropic strategy, restoring myocardial performance by removing inhibitory signaling rather than increasing adrenergic drive. Together, these observations support a stage-dependent, physiology-guided model of β₃-adrenergic modulation. β₃ agonists and antagonists should be viewed as complementary tools, deployed according to disease stage and dominant pathophysiology, with future clinical studies needed to refine patient selection and therapeutic timing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AFA; Methodology, AFA, FM, FAM, MF, MA, NA, RG, RA, SA; software, AFA, FM, FAM, MF, MA, NA, RG, RA, SA; investigation, AFA, FM, FAM, MF, MA, NA, RG, RA, SA; resources, AFA, FM, FAM, MF, MA, NA, RG, RA, SA, data curation, AFA, FM, FAM, MF, MA, NA, RG, RA, SA; writing—original draft preparation, AFA, FM, FAM, MF, MA, NA, RG, RA, SA; writing—review and editing, AFA, FM, FAM, MF, MA, NA, RG, RA, SA; supervision, AFA; project administration, AFA; funding acquisition, (non-applicable). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable as this study is a hypothesis/Review article.

Informed Consent Statement

not applicable as this study is a viewpoint/editorial

Data Availability Statement

All data is made available within the manuscript and are owned by the authors.

Acknowledgement

To our families, who see beyond our limits—and by believing in us, give us the courage to reach the skies above.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The manuscript is submitted under Creative Commons Licensing CC-BY-NC-ND. A large language model has been used to proofread the article.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation |

Full term |

| HF |

Heart Failure |

| HFrEF |

Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction |

| HFpEF |

Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction |

| β₃-AR |

Beta-3 Adrenergic Receptor |

| β₁-AR |

Beta-1 Adrenergic Receptor |

| β₂-AR |

Beta-2 Adrenergic Receptor |

| NO |

Nitric Oxide |

| cGMP |

Cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate |

| PKG |

Protein Kinase G |

| PI3K |

Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase |

| Akt |

Protein Kinase B |

| eNOS |

Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| iNOS |

Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| PH |

Pulmonary Hypertension |

| RV |

Right Ventricle / Right Ventricular |

| ATP |

Adenosine Triphosphate |

| UCP-2 |

Uncoupling Protein 2 |

| LV |

Left Ventricle / Left Ventricular |

References

- Aitken-Buck, HM; Babakr, AA; Fomison-Nurse, IC; et al. Inotropic and lusitropic, but not arrhythmogenic, effects of adipocytokine resistin on human atrial myocardium. Am J Physiol Metab 2020, 319(3), E540–E547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AbdelMassih, AF; Ramadan, B; ElDemerdash, JT; et al. Repurposing Cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate Pathway Medications, from Vasodilation toward Changing the Face of Heart Failure. Hear Views 2024, 25(4), 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddox, TM; Januzzi, JL; Allen, LA; et al. 2024 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway for Treatment of Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2024, 83(15), 1444–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viđak, M; Kursar, J; Bodrožić Džakić Poljak, T; et al. Heart Failure with Mid-Range or Mildly Reduced Ejection Fraction in the Era of Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporter 2 Inhibitors: Do We Now Provide Better Care for the “Middle Child of HF”? Real-World Experience from a Single Clinical Centre. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2024, 11(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schena, G; Caplan, MJ. Everything You Always Wanted to Know about β3-AR * (* But Were Afraid to Ask). Cells 2019, 8(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q; Wu, T-G; Jiang, Z-F; et al. Effect of β-Blockers on β3-Adrenoceptor Expression in Chronic Heart Failure. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2007, 21(2), 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elrosasy, A; Zeid, MA; Samha, R; et al. Efficacy And Safety Of β;3 Agonist Mirabegron In Patients With Heart Failure; Systematic Review And Meta-analysis. J Card Fail 2025, 31(1), 254–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundgaard, H; Axelsson, A; Hartvig Thomsen, J; et al. The first-in-man randomized trial of a beta3 adrenoceptor agonist in chronic heart failure: the BEAT-HF trial. Eur J Heart Fail 2017, 19(4), 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaguchi, S; Okada, M; Ijiri, E; et al. β3-Adrenergic receptor blockade reduces mortality in endotoxin-induced heart failure by suppressing induced nitric oxide synthase and saving cardiac metabolism. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2020, 318(2), H283–H294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabbah, HN; Zhang, K; Gupta, RC; et al. Intravenous Infusion of the β3-Adrenergic Receptor Antagonist APD418 Improves Left Ventricular Systolic Function in Dogs With Systolic Heart Failure. J Card Fail 2021, 27(2), 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaza, A; Rocchetti, M. Development of Small-molecule SERCA2a Stimulators: A Novel Class of Ino-lusitropic Agents. Eur Cardiol Rev 2025, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriques, A; Liu, G; Katchman, A; et al. Probing the CaV1.2 interactome in heart failure identifies a positive modulator of inotropy and lusitropy. bioRxiv Prepr Serv Biol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rødland, L; Rønning, L; Kildal, AB; et al. The β3 Adrenergic Receptor Antagonist L-748,337 Attenuates Dobutamine-Induced Cardiac Inefficiency While Preserving Inotropy in Anesthetized Pigs. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 2021, 26(6), 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).