Submitted:

20 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

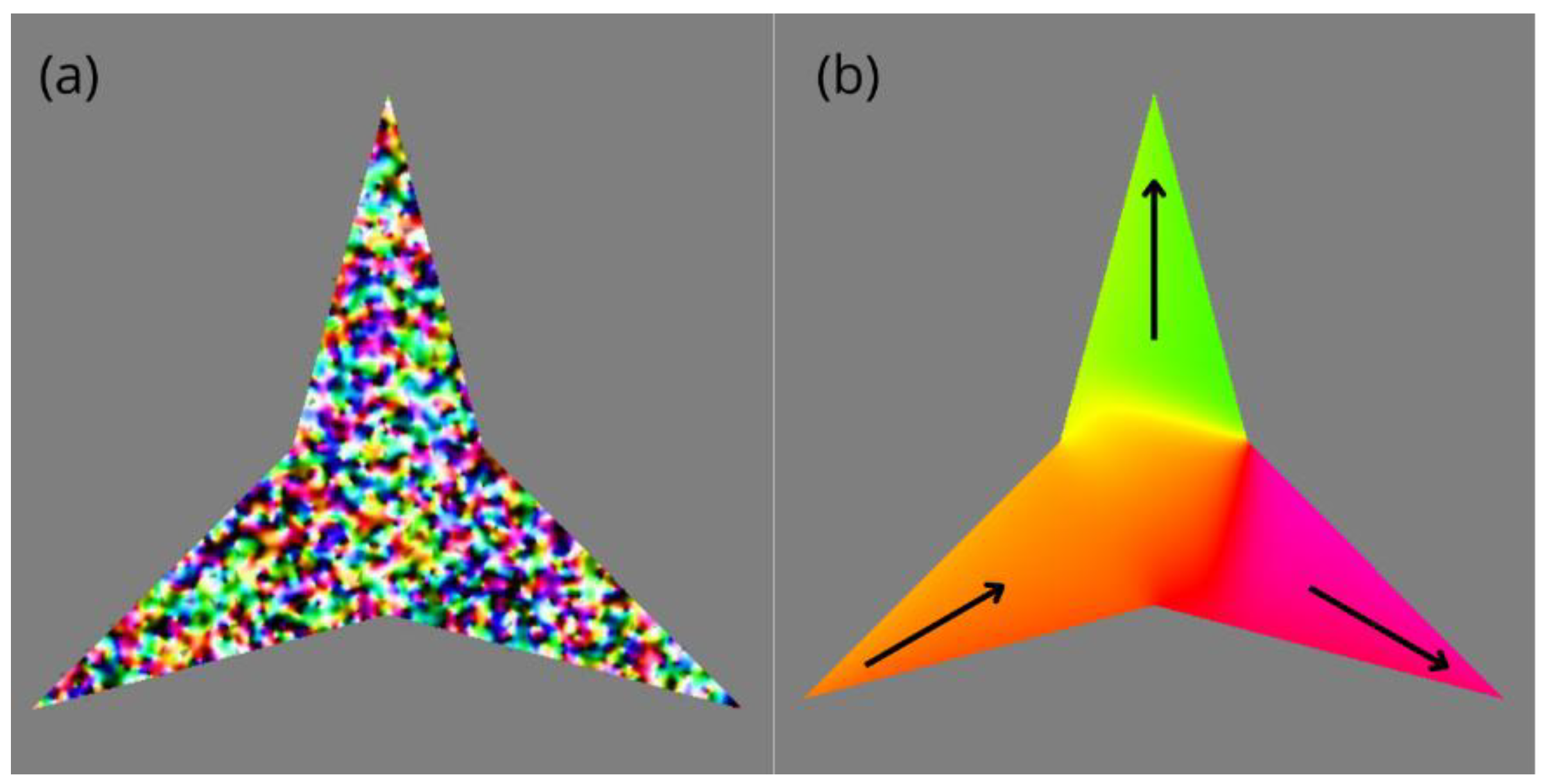

3.1. Non Biased Paths to Equilibrium States

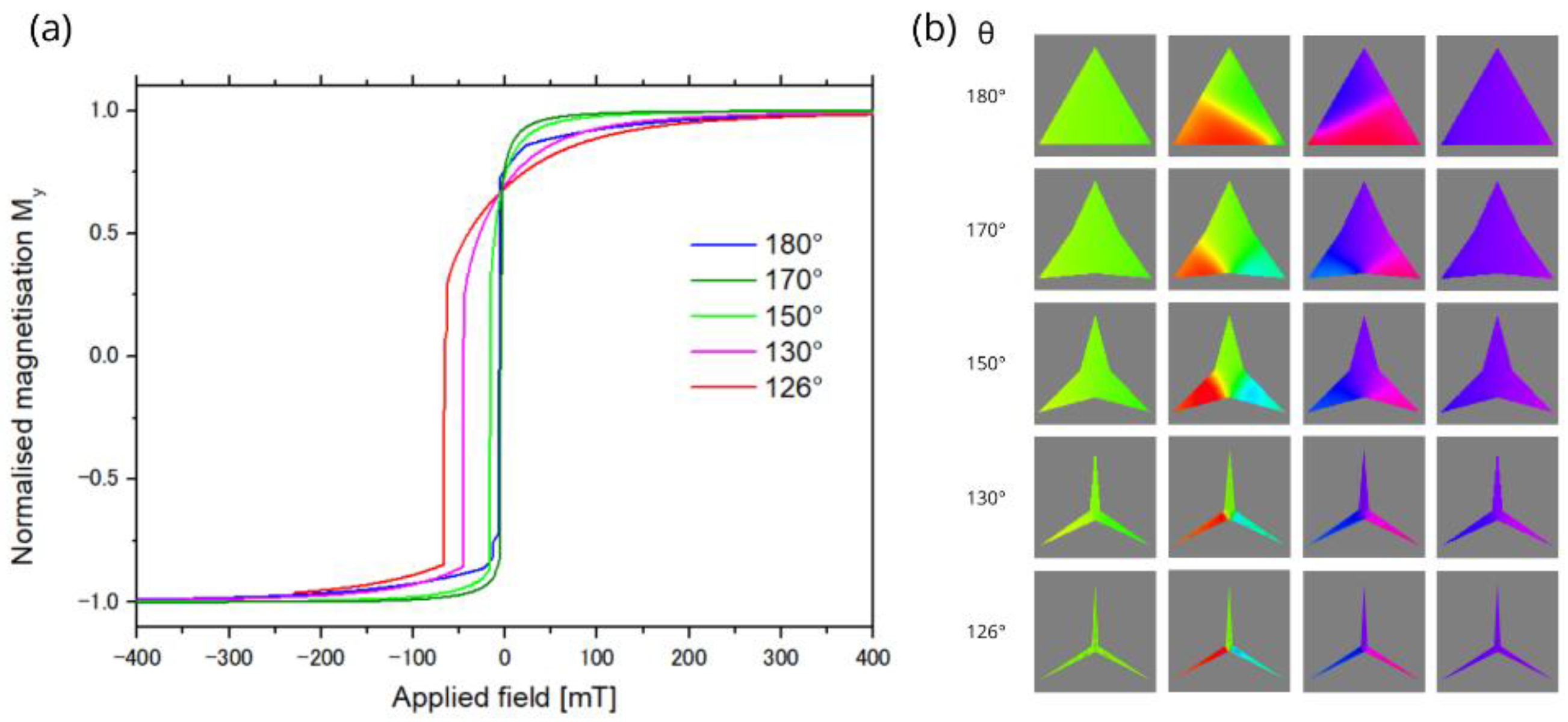

3.2. Switching Properties and Equilibrium States Under an External Field

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Z.; Lin, T.-Y.; Wei, X.; Matsunaga, M.; Doi, T.; Ochiai, Y.; Aoki, N.; Bird, J.P. The Magnetic Y-Branch Nanojunction: Domain-Wall Structure and Magneto-Resistance. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 101, 102403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currivan-Incorvia, J.A.; Siddiqui, S.; Dutta, S.; Evarts, E.R.; Zhang, J.; Bono, D.; Ross, C.A.; Baldo, M.A. Logic Circuit Prototypes for Three-Terminal Magnetic Tunnel Junctions with Mobile Domain Walls. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 10275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, V.; Gutzeit, M.; Rodríguez-Sota, A.; Haldar, S.; Zahner, F.; Wiesendanger, R.; Kubetzka, A.; Heinze, S.; Von Bergmann, K. Strain-Driven Domain Wall Network with Chiral Junctions in an Antiferromagnet. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 10808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamdar, M.; Leonard, T.; Cui, C.; Rimal, B.P.; Xue, L.; Akinola, O.G.; Patrick Xiao, T.; Friedman, J.S.; Bennett, C.H.; Marinella, M.J.; et al. Domain Wall-Magnetic Tunnel Junction Spin–Orbit Torque Devices and Circuits for in-Memory Computing. Applied Physics Letters 2021, 118, 112401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, P.; Barman, S. Three-Input Magnetic Logic Gates Using Magnetic Vortex Transistor. Physica Status Solidi (a) 2022, 219, 2200397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisul Haque, S.; Yamamoto, M.; Nakatani, R.; Endo, Y. Binary Logic Gates by Ferromagnetic Nanodots. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 2004, 282, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, I.; Josephson, L. Magnetic Nanoparticle Sensors. Sensors 2009, 9, 8130–8145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensing Magnetic Nanoparticles. In Magnetic Nanoparticles in Biosensing and Medicine; Darton, N.J., Ionescu, A., Llandro, J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press, 2019; pp. 172–227. ISBN 978-1-139-38122-2. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, F.; Xu, L.; Yan, W.; Wu, W.; Yu, Q.; Tian, X.; Dai, R.; Li, X. A Magnetic Relaxation Switch Aptasensor for the Rapid Detection of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Using Superparamagnetic Nanoparticles. Microchim Acta 2017, 184, 1539–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolikas, C.; Amelinckx, S. Phase transitions in ferroelastic lead orthovanadate as observed by means of electron microscopy and electron diffraction. I. Static observations. Phys. Stat. Sol. (a) 1980, 60, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulesteix, C.; Yangui, B. Star patterns and dissociation of interfaces without spontaneous strain compatibility between orientation domains in ferroelastic crystals. Case of a monoclinic rare earth sesquioxide. Phys. Stat. Sol. (a) 1983, 78, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curnoe, S.H.; Jacobs, A.E. Statics and Dynamics of Domain Patterns in Hexagonal-Orthorhombic Ferroelastics. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 63, 094110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupińska, A.; Burzyńska, B.; Kinzhybalo, V.; Dziuk, B.; Szklarz, P.; Kajewski, D.; Zaręba, J.K.; Drwęcka, A.; Zelewski, S.J.; Durlak, P.; et al. Ferroelectricity, Piezoelectricity, and Unprecedented Starry Ferroelastic Patterns in Organic–Inorganic (CH3 C(NH2 )2 )3 [Sb2 X9 ] (X = Cl/Br/I) Hybrids. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 64, 9639–9651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicens, J.; Delavignette, P. A Particular Domain Configuration Observed in a New Phase of the TaN System. Phys. Stat. Sol. (a) 1976, 33, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, P.; Barman, A.; Barman, S. Operation of Magnetic Vortex Transistor by Spin-Polarized Current: A Micromagnetic Approach. Physica Status Solidi (a) 2022, 219, 2100564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omari, K.A.; Hayward, T.J. Chirality-Based Vortex Domain-Wall Logic Gates. Phys. Rev. Applied 2014, 2, 044001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gypens, P.; Van Waeyenberge, B.; Di Ventra, M.; Leliaert, J.; Pinna, D. Nanomagnetic Self-Organizing Logic Gates. Phys. Rev. Applied 2021, 16, 024055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertel, R.; Gliga, S.; Fähnle, M.; Schneider, C.M. Ultrafast Nanomagnetic Toggle Switching of Vortex Cores. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 98, 117201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitano, Y.; Kifune, K.; Komura, Y. STAR-LISCLINATION IN A FERRO-ELASTIC MATERIAL B19 MgCd ALLOY. J. Phys. Colloques 1988, 49, C5-201–C5-206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobieszczyk, P.; Mroczek, M.; Kuźma, D.; Zieliński, P. Negative Mechanical Characteristics of Self-Similar Star-Like Hinged Grilles. Physica Status Solidi (b) 2024, 261, 2400399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuźma, D.; Pastukh, O.; Zieliński, P. Competing Magnetocrystalline and Shape Anisotropy in Thin Nanoparticles. Crystals 2024, 14, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, A.; Leliaert, J.; Dvornik, M.; Helsen, M.; Garcia-Sanchez, F.; Waeyenberge, B.V. The Design and Verification of MuMax3. AIP Advances 2014, 4, 107133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leliaert, J.; Dvornik, M.; Mulkers, J.; De Clercq, J.; Milošević, M.V.; Van Waeyenberge, B. Fast Micromagnetic Simulations on GPU—Recent Advances Made with $\mathsf{mumax}^3$. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2018, 51, 123002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreels, L.; Lateur, I.; De Gusem, D.; Mulkers, J.; Maes, J.; Milošević, M.V.; Leliaert, J.; Van Waeyenberge, B. Mumax+: Extensible GPU-Accelerated Micromagnetics and Beyond 2024.

- Aharoni, A. Introduction to the Theory of Ferromagnetism, 2. ed., repr.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2007; ISBN 978-0-19-850809-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bouwmeester, H.; Dougherty, A.; Knyazev, A.V. Nonsymmetric Preconditioning for Conjugate Gradient and Steepest Descent Methods 1. Procedia Computer Science 2015, 51, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joos, J.J.; Bassirian, P.; Gypens, P.; Mulkers, J.; Litzius, K.; Van Waeyenberge, B.; Leliaert, J. Tutorial: Simulating Modern Magnetic Material Systems in Mumax3. Journal of Applied Physics 2023, 134, 171101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifshitz, E.M.; Pitaevskii, L.P.; Pitaevskii, L.P. Statistical Physics: Theory of the Condensed State; Course of Theoretical Physics, 3rd ed.; Elsevier Science: Saint Louis, 2013; ISBN 978-0-7506-2636-1. [Google Scholar]

- Nahrwold, G.; Scholtyssek, J.M.; Motl-Ziegler, S.; Albrecht, O.; Merkt, U.; Meier, G. Structural, Magnetic, and Transport Properties of Permalloy for Spintronic Experiments. Journal of Applied Physics 2010, 108, 013907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.M.; Cottam, M.G.; Liu, H.Y.; Wang, Z.K.; Ng, S.C.; Kuok, M.H.; Lockwood, D.J.; Nielsch, K.; Gösele, U. Spin Waves in Permalloy Nanowires: The Importance of Easy-Plane Anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 73, 140402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.; Kim, B.; Kim, S.-K. From Trochoidal Symmetry to Chaotic Vortex-Core Reversal in Magnetic Nanostructures. npj Spintronics 2025, 3, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guslienko, K.Yu.; Han, X.F.; Keavney, D.J.; Divan, R.; Bader, S.D. Magnetic Vortex Core Dynamics in Cylindrical Ferromagnetic Dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 067205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gypens, P.; Leliaert, J.; Schütz, G.; Van Waeyenberge, B. Commensurate Vortex-Core Switching in Magnetic Nanodisks at Gigahertz Frequencies. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 094420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Waeyenberge, B.; Puzic, A.; Stoll, H.; Chou, K.W.; Tyliszczak, T.; Hertel, R.; Fähnle, M.; Brückl, H.; Rott, K.; Reiss, G.; et al. Magnetic Vortex Core Reversal by Excitation with Short Bursts of an Alternating Field. Nature 2006, 444, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuźma, D.; Laskowski, Ł.; Kłos, J.W.; Zieliński, P. Effects of Shape on Magnetization Switching in Systems of Magnetic Elongated Nanoparticles. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 2022, 545, 168685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuźma, D.; Pastukh, O.; Zieliński, P. Spacing Dependent Mechanisms of Remagnetization in 1D System of Elongated Diamond Shaped Thin Magnetic Particles. Magnetochemistry 2022, 8, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Kostylev, M.; Adeyeye, A.O. Realization of a Mesoscopic Reprogrammable Magnetic Logic Based on a Nanoscale Reconfigurable Magnonic Crystal. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 100, 073114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlov, A.; Imre, A.; Csaba, G.; Ji, L.; Porod, W.; Bernstein, G.H. Magnetic Quantum-Dot Cellular Automata: Recent Developments and Prospects. Journal of Nanoelectronics and Optoelectronics 2008, 3, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordquist, K. Process Development of Sub-0.5 Μm Nonvolatile Magnetoresistive Random Access Memory Arrays. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 1997, 15, 2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Jubert, P.-O.; Berman, D.; Imaino, W.; Nelson, A.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, S.; Sun, S. Monolayer Assembly of Ferrimagnetic Co x Fe 3– x O 4 Nanocubes for Magnetic Recording. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 3395–3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Barman, S.; Barman, A. Magnetic Vortex Based Transistor Operations. Sci Rep 2014, 4, 4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

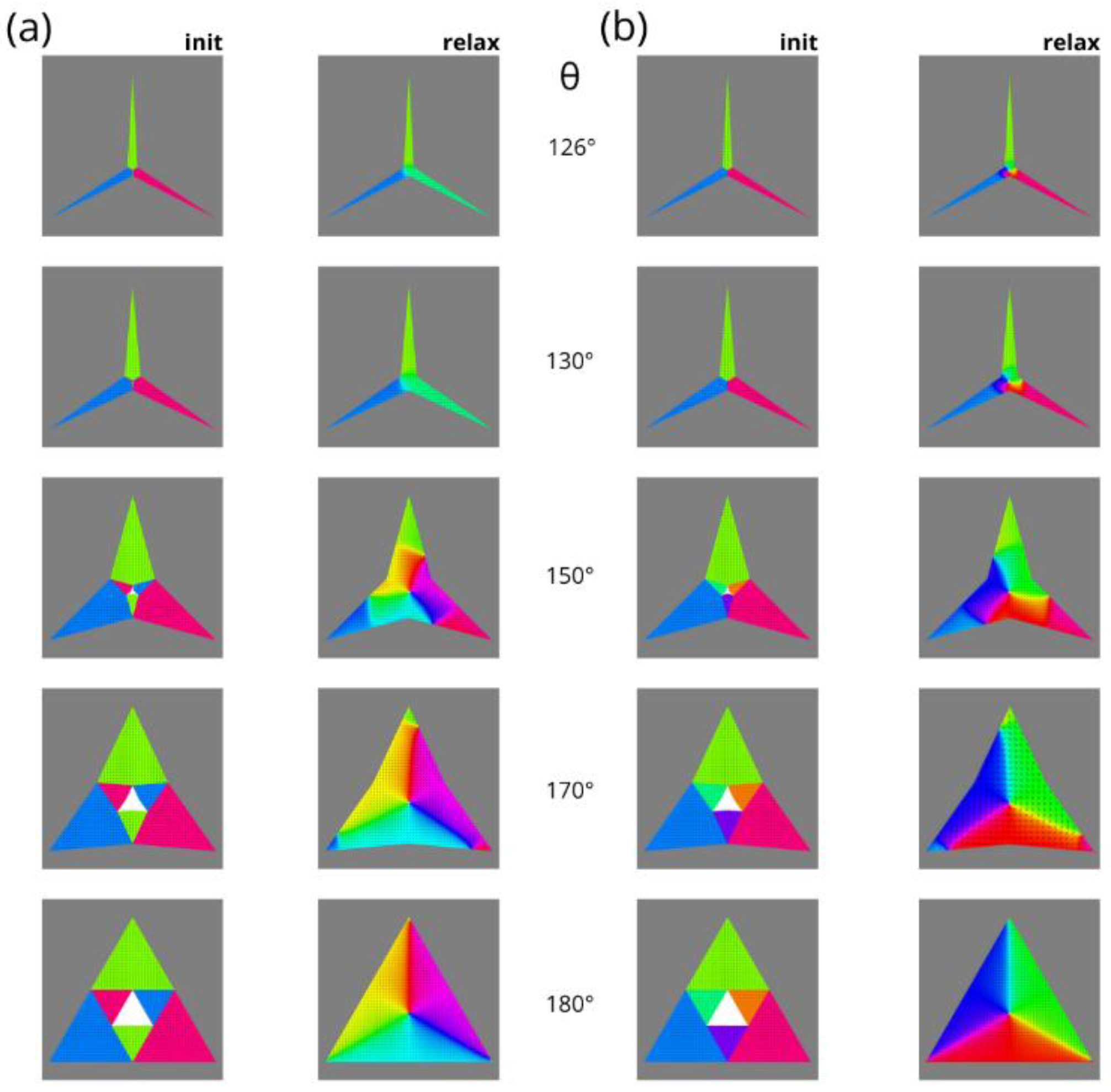

| Etot [10-5 pJ] | 3-domain | 6-domain | hysteresis | random |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 180° | 2.5278681* | 2.5278681* | 1.0451257 | - |

| 170° | 2.9810302* | 2.981451* | 0.8581696 | - |

| 150° | 2.9240302* | 2.924786* | 0.49729887 | 0.8465562 |

| 130° | 0.6808681 | 1.792714* | 0.18028585 | - |

| 126° | 0.51189704 | 1.3600054* | 0.51109695 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).