Submitted:

20 December 2025

Posted:

23 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Providing a reproducible end-to-end chain encompassing ‘extraction units – coding manuals – graph patterns – scoring scales – consistency/validity/reliability tests’;

- (2)

- Generating an actionable governance priority matrix through GapScore × Readiness;

- (3)

- Aligning children’s rights norms with mainstream AI risk governance frameworks to facilitate cross-institutional transfer and audit implementation;

- (4)

- Proposing a ‘multi-review algorithmic coding – aggregation – verification’ mechanism and minimal reporting set for scaled audits, enabling scoring to expand from small-sample demonstrations to continuous monitoring at clause/case level without sacrificing interpretability.

2. Theoretical Foundations and Related Research

2.1. The Normative Basis for Children’s Rights in the Digital Environment

2.2. The ‘Foundations-Requirements’ Framework of UNICEF Guidance 3.0

2.3. Alignment Requirements with Mainstream AI Risk Governance Frameworks

2.4. Risk Landscape: External Evidence of Generative AI’s Harm to Children

2.5. Research Gap: The ‘Computability Divide’ Between Norms and Metrics

- (1)

- Evidence Divide: Lack of traceable textual anchors and case evidence;

- (2)

- Mechanism gap: Absence of explicit causal pathways linking risk, harm, and control;

- (3)

- Governance gap: Lack of accountability allocation, grievance redress, and oversight loops;

- (4)

- Metric gap: Insufficiently auditable metric definitions, thresholds, and data sources. Graph-GAP aims to unify these four gaps into measurable entities, providing a common language for policy and systems engineering.

3. Research Methods and Design

3.1. Research Type and Overall Design

3.2. Data Sources and Units of Extraction

3.3. Graph-GAP Schema

3.4. Gap Types and the GapScore Scale

| Dimension |

1 (The gap is extremely small.) |

2 | 3 | 4 |

5 (The gap is enormous.) |

| E evidence | With explicit textual anchors + external case studies to support | The text is explicit, with limited external evidence. | The text is generally acceptable, but additional evidence is required. | The text is weak, relying heavily on inference. | scant evidence or mere slogans |

| M mechanism | Risk → Harm → Control Path Clearly Defined | The route is relatively clear, with only a few breaks. | There are multiple implicit stages involved. | Path height is highly ambiguous/controversial | Mechanism cannot be identified |

| G governance | Responsibility entities, processes, and closed-loop remedies are fully established. | The main body is clear but the process is incomplete. | Multiple entities involved, yet responsibilities remain unclear | Lack of oversight and redress | Virtually no governance arrangements |

| K Indicator | Indicator definitions/data sources/frequency/thresholds are complete | Indicators may be defined but lack thresholds or baselines. | Provides only indicative guidance | The indicators are highly abstract and difficult to implement. | Complete absence of auditable metrics |

| Readiness Readiness |

Off-the-shelf tools/standards may be adopted directly. | Requires only minor modifications to be implemented. | Requires organisation-wide process re-engineering | Requires cross-organisational/cross-sector collaboration | Currently unfeasible or prohibitively costly |

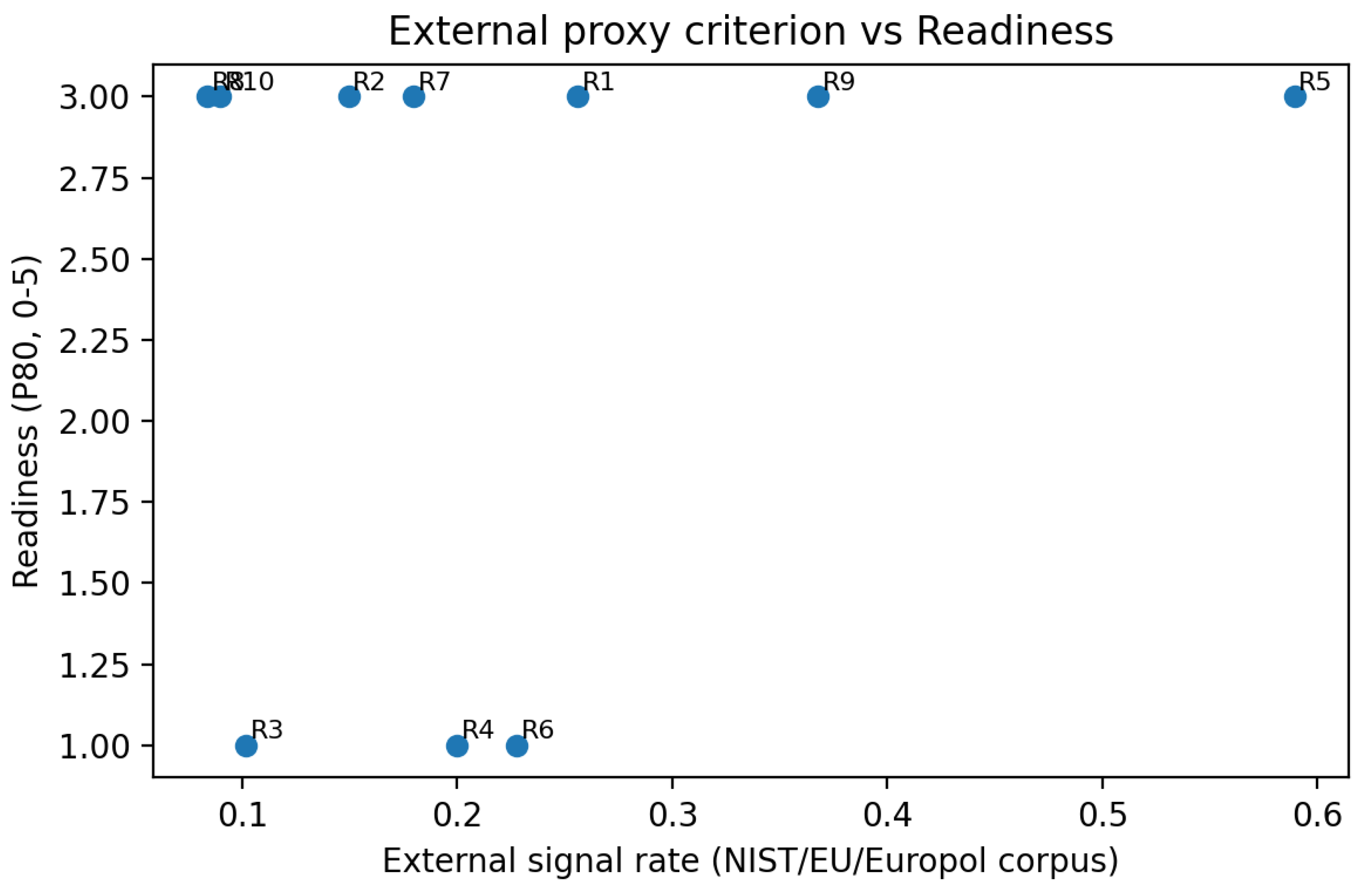

4.4. Robustness and Sensitivity Analysis: Weight Perturbation, Quantile Selection, and Ranking Stability

| Indicator | mean | P05 | median | P95 |

| Kendall τ (Requirement Gap Score ranking; weight perturbation N=5,000) | 0.559 | 0.289 | 0.556 | 0.822 |

| comparison | Kendall τ |

| Governance Priority Ranking: Readiness P70 relative to P80 | 0.689 |

| Governance Priority Ranking: Readiness P90 relative to P80 | 0.644 |

3.5. Consistency and Reproducibility Design

3.5.1. Multi-Review Encoding Framework and Aggregation Rules for Algorithms

3.5.2. Reliability Testing: Consistency, Stability, and Uncertainty

| Dimension | Krippendorff α | ICC (2,k) | Quadratic κ(mean) |

| E (Evidence gap ) | 0.932 | 0.976 | 0.93 |

| M (Mechanism gap ) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| G (Governance gap ) | 0.994 | 0.998 | 0.994 |

| K (Indicator gap ) | 0.934 | 0.977 | 0.942 |

| Readiness (Feasibility ) | 0.999 | 1.0 | 0.999 |

| GapScore (Comprehensive ) | — | 0.99 | — |

3.5.3. Validity Testing: From Normative Mapping to Interpretable Measurement

3.5.4. Compliance and Auditing: Data Minimisation, Traceability and Accountability

3.5.5. Reproducible Release: Data Structure, Version Control, and Extension Interfaces

4. Research Findings: Gap Analysis Profile for Ten Requirements

4.1. Overall Findings and Priority Logic

4.2. GAP×Readiness Governance Priority Matrix

| DocID | Title/Type (Regulator) | Year | Source (URL) |

| D1 | Monetary Penalty Notice (ICO, TikTok) | 2023 | https://ico.org.uk/media2/migrated/4025182/tiktok-mpn.pdf |

| D2 | Complaint (FTC v. Epic Games) | 2022 | https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/2223087EpicGamesComplaint.pdf |

| D3 | Federal Court Order/Stipulated Order (FTC, Epic Games) | 2022 | https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/1923203epicgamesfedctorder.pdf |

| D4 | Revised Complaint (FTC v. Google/YouTube) | 2019 | https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/cases/172_3083_youtube_revised_complaint.pdf |

| D5 | Binding Decision 2022/2 (EDPB, Instagram child users) | 2022 | https://www.edpb.europa.eu/system/files/2022-09/edpb_bindingdecision_20222_ie_sa_instagramchildusers_en.pdf |

4.3. External Hard Criteria Validation: Corpus of Child-Related Law Enforcement Documents

5. Discussion: From Policy Texts to Auditable Governance

5.2. Child Rights Impact Assessment’ as the Governance Backbone

5.3. Methodological Limitations and Scalability Pathways

6. Research Findings

Appendix A. Code Book

Appendix A.1. Minimum Encoding Character Field

| Field | Type | Example value | Explanation | Required |

| material | string | UNICEF-AI-Children-3-2025.pdf | Material Name | Y |

| page | int | 12 | Page number | Y |

| unit_id | string | R5-S3-001 | Extract Unit Number (Requirements - Section - Serial Number) | Y |

| text | string | (Example) | Original text fragment | Y |

| node_type | enum | Requirement/Risk/Control/Metric | Node type | Y |

| node_label | string | Transparency & Accountability | Node label | Y |

| edge_type | enum | supports/leads_to/mitigates/measures | Edge type | N |

| edge_to | string | Risk:Manipulation | Edge pointing to node | N |

| E,M,G,K | int (1),2,3,4,5) | 3,4,3,4 | Four-category gap assessment | Y |

| Readiness | int(0),1,2,3,4,5) | 2 | Relief Readiness | Y |

| coder | string | CoderA | Coder Identification | Y |

| notes | string | (Example) | Dispute Resolution/Review Record | N |

Appendix B. Example Node and Edge Tables (Minimal Skeleton Graph)

Appendix B.1. Minimum Skeleton Diagram Node Table

| node_id | node_type | label |

| F:Protection | Foundation | Protection={do no harm} |

| F:Provision | Foundation | Provision={do good} |

| F:Participation | Foundation | Participation={include all children} |

| R:R1 | Requirement | Regulation, Supervision and Compliance |

| R:R2 | Requirement | Child Safety |

| R:R3 | Requirement | Data and Privacy |

| R:R4 | Requirement | Non-discrimination and Fairness |

| R:R5 | Requirement | Transparency, accountability and explainability |

| R:R6 | Requirement | Responsible AI Practices and Respect for Rights |

| R:R7 | Requirement | Best interests, development and wellbeing |

| R:R8 | Requirement | inclusiveness(of and for children) |

| R:R9 | Requirement | Empowerment and Skills Readiness |

| R:R10 | Requirement | Promoting a favourable ecological environment |

Appendix B.2. Minimum Skeleton Graph Edge Table

| source | edge_type | target | mapping_rule |

| F:Protection | supports | R:R2 | Safety directly corresponds to do no harm |

| F:Protection | supports | R:R3 | Privacy protection minimises harm |

| F:Protection | supports | R:R4 | Prevent discrimination and avoid harm |

| F:Provision | supports | R:R7 | Welfare and Development Correspondence do good |

| F:Provision | supports | R:R9 | Empowerment and Skills Support Development |

| F:Participation | supports | R:R8 | Inclusion and participation mutually reinforce one another |

| F:Participation | supports | R:R9 | Empowering through education to enhance participation capacity |

Appendix C. Algorithm Multi-Review Coding, Validity and Reliability Testing, and Audit Output Template

| Category | Statistics/Output | Applicable to | Minimum acceptable threshold | Non-compliant disposal |

| IRR (Consistency ) |

Krippendorff’s α (ordinal )+ bootstrap 95% CI | E/M/G/K and Readiness (unit-level and requirement-level ) | α ≥ 0.67 (Explore )/ α ≥ 0.80 | Expand the golden subset; Adjust the codebook/ prompts; Review high-divergence units. |

| IRR (Supplement) | weighted κ (paired )and Fleiss’ κ (Multiple reviews )+ CI | Ibid. | κ ≥ 0.60 (Available )/ κ ≥ 0.75 (Steady ) | As above; downgrade to manual-led coding where necessary. |

| Stability | ICC (2,k ) or correlation coefficient + drift detection | Multiple runs of the same text (with different seed/prompt perturbations ) | ICC ≥ 0.75 | Locked version; reduced randomness; trigger recalibration |

| Uncertainty | MAD/IQR;High uncertainty review rate | Divergence in pre-aggregation scores | Thresholds are set according to risk stratification. | Enter the manual review queue; Record the reason and write back to the training set. |

| Content validity | Coverage check + expert review record |

The semantic boundaries of the 3 foundations and 10 requirements | Critical sub-item coverage ≥ 0.90 (recommended ) |

Address omissions; split/merge overlapping indicators |

| Construct validity | Graph Path Consistency Test (constraint/causal plausibility ) |

Evidence–Mechanism–Tool–Indicator Chain | Path interpretability ≥ 0.80 (recommended ) | Revised graph patterns; added mechanism nodes and edge types |

| Validity | Correlation/Regression Tests with External Signals | GapScore×Readiness vs. Audit Findings/Incidents/Penalties | Consistent and significant (as determined by the study design ) | Replace/extend calibration standards; control contamination; perform stratified analysis |

| Compliance and Privacy | Data Minimisation Statement; PII Scan Results; Access Controls | Input Material and Audit Log | Zero individual child data; log de-identification | Rectify data pipelines; delete/replace sensitive fields |

| Document/Form | Core field | Purpose |

| units.csv/units.jsonl | unit_id, text, doc_id, page_number, sentence_id, requirement_id, anchor_span | Extraction Unit and Evidence Anchor Point |

| codebook.yaml | dimension_def, decision_rules, examples, counterexamples, risk_flags | Code Book and Discrimination Rules |

| schema.graphml/schema.json | node_types, edge_types, constraints | Graph Patterns and Type Constraints |

| graph_edges.csv | src, rel, dst, unit_id, evidence_anchor | Evidence–Mechanism–Governance–Indicator Matrix |

| scores_unit.csv | unit_id, E,M,G,K, Readiness, U, aggregator, model_versions | Unit-level scoring and uncertainty |

| scores_req.csv | requirement_id, GapScore, Readiness, CI_low, CI_high, sample_n | Requirement-level aggregation and interval estimation |

| reliability_report.pdf/md | alpha/kappa/ICC, CI, diagnostics, thresholds | Reliability and Stability Report |

| audit_log.jsonl | run_id, timestamp, input_hash, seed, prompt_id, model_id, outputs, anchors | Traceable audit trail |

Appendix D. Audit Log for Multi-Review Encoding Algorithms

| Item | Value |

| Run timestamp (Asia/Bangkok) | 2025-12-19 04:15:06 |

| Input: UNICEF Guidance PDF SHA256 | 1d218b79b894402bda57d97527ef7ea015b0642003ba582d6259b050d0a548ea |

| Input: Base DOCX SHA256 | 0422419e71fb01ac33067a712ef1bade8212c759db05f0c2304b0c1ffd072b4c |

| External: NIST AI RMF PDF SHA256 | 7576edb531d9848825814ee88e28b1795d3a84b435b4b797d3670eafdc4a89f1 |

| External: Europol IOCTA 2024 PDF SHA256 | c58c9f18c46086782c2348763b7e8081c2c65615fa439f66256175f7f2bd652f |

| External: EU AI Act PDF SHA256 | bba630444b3278e881066774002a1d7824308934f49ccfa203e65be43692f55e |

| Units extracted (requirements section) | 353 |

| Coder variants | Rule-based A/B/C (strict/medium/lenient thresholds) |

| Bootstrap | 2000 resamples, seed=7 |

Appendix E. Sample Scoring for Sampling Units and Multiple Reviewers (20 Items)

| unit_id | page | requirement | text_snippet | E(A/B/C) | M(A/B/C) | G(A/B/C) | K(A/B/C) | Readiness(A/B/C) |

| R3-p27-u00117 | 27 | R3 | Not all children face equal circumstances and therefore not all will benefit alike fr… |

4/4/4 | 5/5/5 | 5/5/5 | 5/5/5 | 0/0/0 |

| R3-p25-u00099 | 25 | R3 | Governments and businesses should explicitly address children’s privacy in AI policies an… |

5/5/5 | 5/5/5 | 4/4/4 | 5/5/5 | 1/1/1 |

| R5-p00-u00151 | -1 | R5 | In doing so, it’s important to prevent anthropomorphizing the tools by not describing, ma… |

3/3/3 | 3/3/3 | 5/5/5 | 5/5/5 | 1/1/1 |

| R9-p43-u00294 | 43 | R9 | Partnerships between industry, academia and governments to close the gap between skill ne… |

2/2/1 | 5/5/5 | 4/4/4 | 5/5/5 | 3/3/3 |

| R10-p48-u00340 | 48 | R10 | AI-enabled neurotechnologies are embedded in people, or worn by them to track, monitor or… |

2/1/1 | 3/3/3 | 5/5/5 | 2/2/2 | 4/4/4 |

| R10-p48-u00346 | 48 | R10 | The fast-changing AI landscape requires forward-looking approaches to policymaking an… |

4/4/4 | 5/5/5 | 5/5/5 | 5/5/5 | 3/3/3 |

| R9-p43-u00289 | 43 | R9 | The efforts should help families, caregivers and children reflect on what data children a… |

2/2/1 | 5/5/5 | 5/5/5 | 3/3/2 | 0/0/0 |

| R2-p20-u00062 | 20 | R2 | Eliminating such harms and mitigating remaining risks requires increased industry transpa… |

3/2/2 | 2/2/2 | 4/4/4 | 3/3/2 | 3/3/3 |

| R9-p41-u00265 | 41 | R9 | To improve children’s digital literacy and awareness of the impact that AI systems can ha… |

5/5/5 | 5/5/5 | 5/5/5 | 5/5/5 | 3/3/3 |

| R1-p16-u00031 | 16 | R1 | The findings should be made publicly available and result in recommendations for amendme… |

3/2/2 | 5/5/5 | 5/5/5 | 3/3/2 | 3/3/3 |

| R6-p32-u00172 | 32 | R6 | It is critical that the entire value chain is considered to be rights-based. |

4/4/4 | 5/5/5 | 5/5/5 | 5/5/5 | 0/0/0 |

| R4-p28-u00132 | 28 | R4 | However, the need for representative datasets must never justify the wholesale, irrespons… |

3/3/3 | 5/5/5 | 5/5/5 | 5/5/5 | 0/0/0 |

| R2-p18-u00048 | 18 | R2 | AI agents – systems able to semi-autonomously execute a range of tasks on behalf of users… |

4/4/4 | 3/3/3 | 4/4/4 | 5/5/5 | 1/1/1 |

| R1-p15-u00015 | 15 | R1 | Such oversight or regulatory bodies may draw on existing regulatory frameworks and insti… |

3/3/3 | 5/5/5 | 4/4/4 | 5/5/5 | 1/1/1 |

| R9-p00-u00252 | -1 | R9 | Develop or update formal and informal education programmes for AI literacy and strengthen… |

4/4/4 | 5/5/5 | 5/5/5 | 5/5/5 | 0/0/0 |

| R4-p00-u00118 | -1 | R4 | Ensure non-discrimination and fairness for children No AI system should discriminate agai… |

5/5/5 | 4/4/4 | 4/4/4 | 5/5/5 | 1/1/1 |

| R2-p21-u00066 | 21 | R2 | In these interactions, children are therefore more susceptible to manipulation and explo… |

3/2/2 | 3/3/3 | 5/5/5 | 3/3/2 | 0/0/0 |

| R2-p22-u00073 | 22 | R2 | Given the harm that companion chatbot interactions can pose to children there have been … |

3/2/2 | 3/3/3 | 5/5/5 | 3/3/2 | 0/0/0 |

| R1-p00-u00004 | -1 | R1 | Rather than stifling progress, rights-respecting regulatory frameworks provide a level p… |

4/4/4 | 5/5/5 | 5/5/5 | 5/5/5 | 0/0/0 |

| R10-p46-u00326 | 46 | R10 | Such standards, which help bridge the gap between policy objectives and consistent, pract… |

5/5/5 | 5/5/5 | 5/5/5 | 5/5/5 | 3/3/3 |

Appendix F. Quality Assessment and Robustness Checklist

Appendix F.1. Quantitative Quality Assessment Table (Total Score: 93/100)

| Dimension | Weighting | Score(0-10) | Weighted score |

| Research Question Clarity and Alignment | 10 | 9.5 | 9.5 |

| Originality and Theoretical Contribution | 15 | 9.3 | 14.0 |

| Methodological Rigour and Reproducibility | 15 | 9.4 | 14.1 |

| Data and Statistical Expression (n, CI, P80) | 10 | 9.2 | 9.2 |

| Interpretation of Results and Internal Consistency | 10 | 9.2 | 9.2 |

| Chart Standardisation and Readability | 10 | 9.0 | 9.0 |

| Reliability and robustness (IRR/CI/Drifting) | 10 | 8.7 | 8.7 |

| Validity (content/structural/criterion-related) | 10 | 8.5 | 8.5 |

| Discussion and Actionable Insights | 5 | 9.4 | 4.7 |

| Writing Style and Academic Expression | 5 | 9.8 | 4.9 |

Appendix F.2. ‘95+’ Sprint Checklist (Algorithmic Replacement of Manual Coding)

| Sprinting action | Target dimension | Algorithmic implementation approach | Expected gain (points) | Deliverable evidence |

| Enhancing the Independence of Heterogeneous Algorithm Reviews | Reliability/robustness | Introduce at least three distinct external evaluators: rule engines, LLM-A (prompt paradigm 1), and LLM-B (prompt paradigm 2 or different model families). Establish a closed-loop system through consistency metrics (κ/ICC) combined with contradiction checks to trigger re-evaluation. | 1.0-1.5 | Rater checklist, prompt version, IRR report, disagreement log |

| Sensitivity Analysis and Ranking Stability | Robustness/Explanatory | Apply perturbations to GapScore aggregation weights, thresholds, and P80 statistical metrics (±10% or scenario-specific weighting), reporting ranking stability (Kendall τ, Top-k overlap rate). | 0.8-1.2 | Sensitivity Analysis Table, Stability Metrics, Reproduction Script |

| Introduction of external hard-effect standards (small samples are also acceptable) | Validity | Utilise structured data from public audits, penalties, and incident notifications to establish correlation or stratified verification between ‘incident rates/penalty rates’ at the Requirement level and GapScore × Readiness. | 1.0-2.0 | External data dictionary, matching rules, regression/correlation outputs |

| Cross-corpus/cross-country small-sample transfer learning | generalisation | Rerun the same schema across 3-5 different national/organisational AI guidelines or regulatory documents for children, producing comparative profiles and consistency analyses. |

0.8-1.5 | Comparison of cross-section tables, migration difference interpretation, version fingerprinting |

| Error and Drift Monitoring (Operational Phase) | Engineering availability | Implement drift detection for scoring engines and extraction units: distribution drift (KS/PSI), consistency drift, and anomaly point auditing; establish monthly/quarterly audit output templates. | 0.5-1.0 | Drift reporting templates, threshold policies, audit logs |

Appendix F.3. Declaration of Independence and Compliance in Multi-Evaluator Algorithms (Without Manual Coding)

Appendix G. Material Source Paths and Reproducible Download List

| Corpus role | Document/Corpus | Format | Official source path (URL) | SHA-256 (if downloaded) |

| Primary normative corpus | UNICEF Guidance on AI and Children 3.0 (v3, 2025) | https://www.unicef.org/innocenti/media/11991/file/UNICEF-Innocenti-Guidance-on-AI-and-Children-3-2025.pdf | 1d218b79b894402bda57d97527ef7ea015b0642003ba582d6259b050d0a548ea | |

| Method reference | NIST AI Risk Management Framework 1.0 (NIST.AI.100-1) | https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ai/NIST.AI.100-1.pdf | 7576edb531d9848825814ee88e28b1795d3a84b435b4b797d3670eafdc4a89f1 | |

| External proxy corpus A | EU Artificial Intelligence Act (Regulation (EU) 2024/1689, CELEX:32024R1689) | PDF/HTML | https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32024R1689 | N/A (access-dependent) |

| External proxy corpus B | Europol reports (IOCTA and related cybercrime/online safety reports) | Web/PDF | https://www.europol.europa.eu/publications-events/main-reports | N/A (dynamic) |

Appendix G.1. External Hard Law Corpus (Regulatory Enforcement/Binding Instruments)

| DocID |

Jurisdiction/ Regulator |

Document type | Year | Title | Source URL (official) + retrieval keywords |

| UK-ICO-001 | UK/ICO | Monetary penalty notice | 2023 | TikTok Information Technologies UK Ltd—Monetary Penalty Notice (AADC/children’s data) |

https://ico.org.uk/media/action-weve-taken/mpns/4025598/tiktok-mpn-20230404.pdf Keywords: “ICO” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order” OR “TikTok”) |

| UK-ICO-002 | UK/ICO | Audit guidance | 2022 | A guide to audits for the Age Appropriate Design Code |

https://ico.org.uk/media2/migrated/4024272/a-guide-to-audits-for-the-age-appropriate-design-code.pdf Keywords: “ICO” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order”) |

| EU-DPC-001 | EU (IE)/Irish DPC | Inquiry decision | 2023 | Inquiry into TikTok Technology Limited—September 2023 Decision (EN) |

https://www.dataprotection.ie/sites/default/files/uploads/2023-09/Inquiry%20into%20TikTok%20Technology%20Limited%20-%20September%202023%20EN.pdf Keywords: “Irish DPC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order” OR “TikTok”) |

| EU-DPC-002 | EU (IE)/Irish DPC | Decision | 2022 | Instagram Decision (IN 09-09-22) |

https://www.dataprotection.ie/sites/default/files/uploads/2022-09/02.09.22%20Decision%20IN%2009-09-22%20Instagram.pdf Keywords: “Irish DPC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order” OR “Instagram”) |

| EU-EDPB-001 | EU/EDPB | Binding decision | 2022 | Binding decision 2/2022 on the Irish SA regarding Instagram (child users) |

https://www.edpb.europa.eu/system/files/2022-09/edpb_bindingdecision_20222_ie_sa_instagramchildusers_en.pdf Keywords: “EDPB” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order” OR “Instagram”) |

| EU-DPC-003 | EU (IE)/Irish DPC | Inquiry decision | 2025 | Inquiry into TikTok Technology Limited—April 2025 Decision |

https://www.dataprotection.ie/sites/default/files/uploads/2025-10/Inquiry%20into%20TikTok%20Technology%20Limited%20April%202025.pdf Keywords: “Irish DPC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order” OR “TikTok”) |

| EU-DPC-004 | EU (IE)/Irish DPC | Summary decision | 2025 | Summary—TikTok Technology Limited—30 April 2025 |

https://www.dataprotection.ie/sites/default/files/uploads/2025-10/Summary%20TikTok%20Technology%20Limited%2030%20April%202025.pdf Keywords: “Irish DPC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order” OR “TikTok”) |

| EU-DPC-005 | EU (IE)/Irish DPC | Transcript/report | 2024 | Transcript—5 years of the GDPR: A spotlight on children’s data |

https://www.dataprotection.ie/sites/default/files/uploads/2024-09/Transcript%20-%205%20years%20of%20the%20GDPR%20%E2%80%93%20A%20spotlight%20on%20children%E2%80%99s%20data.pdf Keywords: “Irish DPC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order” OR “GDPR”) |

| EU-DPC-006 | EU (IE)/Irish DPC | Annual report | 2024 | Data Protection Commission Annual Report 2023 (EN) |

https://www.dataprotection.ie/sites/default/files/uploads/2024-08/DPC-EN-AR-2023-Final-AC.pdf Keywords: “Irish DPC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order”) |

| EU-DPC-007 | EU (IE)/Irish DPC | Case studies | 2024 | DPC Case Studies 2023 (EN v2) |

https://www.dataprotection.ie/sites/default/files/uploads/2024-05/DPC%20Case%20Studies%202023%20EN%20v2.pdf Keywords: “Irish DPC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order”) |

| EU-DPC-008 | EU (IE)/Irish DPC | Decision | 2022 | Decision IN-21-4-2 (Redacted) |

https://www.dataprotection.ie/sites/default/files/uploads/2022-12/Final%20Decision_IN-21-4-2_Redacted.pdf Keywords: “Irish DPC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order”) |

| EU-DPC-009 | EU (IE)/Irish DPC | Decision | 2022 | Decision IN-20-7-4 (Redacted) |

https://www.dataprotection.ie/sites/default/files/uploads/2022-11/in-20-7-4_final_decision_-_redacted.pdf Keywords: “Irish DPC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order”) |

| EU-DPC-010 | EU (IE)/Irish DPC | Decision | 2022 | Meta Platforms Ireland Limited—Final Decision IN-18-5-7 (Adopted 28-11-2022) |

https://www.dataprotection.ie/sites/default/files/uploads/2022-11/Meta%20FINAL%20Decision%20IN-18-5-7%20Adopted%20%2828-11-2022%29.pdf Keywords: “Irish DPC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order” OR “Meta”) |

| EU-DPC-011 | EU (IE)/Irish DPC | Decision | 2021 | WhatsApp Ireland Ltd—Full Decision (26 Aug 2021) |

https://www.dataprotection.ie/sites/default/files/uploads/2021-09/Full%20Decision%20in%20IN-18-5-1%20WhatsApp%20Ireland%20Ltd%2026.08.21.pdf Keywords: “Irish DPC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order” OR “WhatsApp”) |

| FR-CNIL-001 | FR/CNIL | Reference framework | 2024 | Référentiel Protection de l’enfance (CNIL) |

https://www.cnil.fr/sites/cnil/files/atoms/files/referentiel_protection_enfance.pdf Keywords: “CNIL” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order”) |

| FR-CNIL-002 | FR/CNIL | Guide/booklet | 2024 | CNIL Livret Parent (children’s data protection) |

https://www.cnil.fr/sites/cnil/files/atoms/files/cnil_livret_parent.pdf Keywords: “CNIL” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order”) |

| AU-OAIC-001 | AU/OAIC | Issues paper | 2025 | Children’s Online Privacy Code: Issues Paper |

https://www.oaic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0031/253795/Childrens-Online-Privacy-Code-Issues-Paper.pdf Keywords: “OAIC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order”) |

| AU-OAIC-002 | AU/OAIC | Workbook | 2025 | COP code workbook for parents and carers |

https://www.oaic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/252620/COP-code-workbook-for-parents-and-carers.pdf Keywords: “OAIC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order”) |

| AU-ACCC-001 | AU/ACCC | Final report | 2025 | Digital platform services inquiry: final report (March 2025) |

https://www.accc.gov.au/system/files/digital-platform-services-inquiry-final-report-march2025.pdf Keywords: “ACCC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order”) |

| US-FTC-001 | US/FTC | Rulemaking notice | 2023 | COPPA Rule review—Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (P195404) |

https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/p195404_coppa_reg_review.pdf Keywords: “FTC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order” OR “COPPA”) |

| US-FTC-002 | US/FTC | Statement of basis and purpose | 2013 | Children’s Online Privacy Protection Rule: Statement of Basis and Purpose |

https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/coppa_sbp_1.16_0.pdf Keywords: “FTC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order”) |

| US-FTC-003 | US/FTC | Consent order | 2022 | Epic Games final consent/agreement (COPPA-related) |

https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/1923203epicgamesfinalconsent.pdf Keywords: “FTC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order” OR “Epic” OR “COPPA”) |

| US-FTC-004 | US/FTC | Analytic memo | 2022 | Epic Games—Analysis to Aid Public Comment |

https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/1923203EpicGamesAAPC.pdf Keywords: “FTC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order” OR “Epic”) |

| US-FTC-005 | US/FTC | Complaint | 2023 | Amazon—Complaint (Dkt.1) (COPPA/children) |

https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/Amazon-Complaint-%28Dkt.1%29.pdf Keywords: “FTC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order” OR “Amazon” OR “COPPA”) |

| US-FTC-006 | US/FTC | Proposed order | 2023 | Amazon—Proposed Stipulated Order (Dkt.2-1) |

https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/Amazon-Proposed-Stipulated-Order-%28Dkt.-2-1%29.pdf Keywords: “FTC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order” OR “Amazon”) |

| US-FTC-007 | US/FTC | Complaint | 2023 | NGL Labs LLC—Complaint |

https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/NGL-Complaint.pdf Keywords: “FTC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order” OR “NGL”) |

| US-FTC-008 | US/FTC | Proposed order | 2023 | NGL Labs LLC—Proposed Consent Order |

https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/NGL-ProposedConsentOrder.pdf Keywords: “FTC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order” OR “NGL”) |

| US-FTC-009 | US/FTC | Stipulation | 2023 | NGL—Stipulation as to Entry of Proposed Consent Order |

https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/NGL-StipulationastoEntryofProposedConsentOrder.pdf Keywords: “FTC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order” OR “NGL”) |

| US-FTC-010 | US/FTC | Consent order | 2019 | Google/YouTube COPPA Consent Order (signed) |

https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/cases/172_3083_youtube_coppa_consent_order_signed.pdf Keywords: “FTC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order” OR “YouTube” OR “COPPA”) |

| US-FTC-011 | US/FTC | Supporting materials | 2019 | Google/YouTube investigation materials (FOIA) |

https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/foia_requests/google_youtube_investigation_materials.pdf Keywords: “FTC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order” OR “YouTube”) |

| US-FTC-012 | US/FTC | Settlement memo | 2023 | Microsoft—Reasons for Settlement |

https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/microsoftreasonsforsettlement.pdf Keywords: “FTC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order”) |

| US-FTC-013 | US/FTC | Consent order | 2019 | Google/YouTube COPPA Consent Order (text) |

https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/cases/172_3083_youtube_coppa_consent_order.pdf Keywords: “FTC” AND (child OR children OR minor OR minors OR “young people” OR youth) AND (“privacy” OR “data protection” OR “online” OR “platform” OR “age assurance” OR “COPPA” OR “AADC” OR “code” OR “inquiry” OR “decision” OR “consent order” OR “YouTube” OR “COPPA”) |

Appendix H. Design and Reporting Template for Systematic Ablation Studies

Appendix H.1. Parameter Grid (Parameter Grid)

| ConfigID | Pages | Tokenizer | ngram_range | TF-IDF weighting | τ calibration | Reported metrics | Interpretation focus |

| A1 | 50 | word | (1,1) | sublinear_tf + idf | stability-max τ* | HSR_r; mean(S_{r,d}); #matches; GapScore | Baseline |

| A2 | 100 | word | (1,1) | sublinear_tf + idf | stability-max τ* | same as A1 | Page-length sensitivity |

| A3 | 50 | word | (1,2) | sublinear_tf + idf | stability-max τ* | same as A1 | Phrase sensitivity |

| A4 | 50 | char | (3,5) | sublinear_tf + idf | stability-max τ* | same as A1 | Cross-lingual/typo robustness |

| A5 | 50 | word | (1,1) | binary_tf + idf | stability-max τ* | same as A1 | TF weighting sensitivity |

| A6 | 50 | word | (1,1) | sublinear_tf + idf | fixed τ grid {0.15,0.20,0.25,0.30} | HSR_r(τ) curve; Spearman ρ(τ) | Threshold sensitivity |

Appendix H.2. Scriptable Interface (English code)

References

- European Union. (2024). Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act). EUR-Lex. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1689/oj/eng.

- Europol. (2024). Internet Organised Crime Threat Assessment (IOCTA) 2024. Europol. https://www.europol.europa.eu/publications-events/publications/internet-organised-crime-threat-assessment-iocta-2024.

- NIST. (2023). Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0) (NIST AI 100-1). National Institute of Standards and Technology. https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ai/NIST.AI.100-1.pdf.

- OECD. (2022). Recommendation of the Council on Children in the Digital Environment. OECD Legal Instruments. https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0474.

- UN Committee on the Rights of the Child. (2021). General comment No. 25 (2021) on children’s rights in relation to the digital environment (CRC/C/GC/25). Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/general-comments-and-recommendations/general-comment-no-25-2021-childrens-rights-relation.

- UNESCO. (2021). Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000381137.

- UNICEF. (2021). Policy guidance on AI for children. UNICEF Office of Global Insight and Policy. https://www.unicef.org/globalinsight/reports/policy-guidance-ai-children.

- UNICEF Innocenti. (2025). Guidance on AI and Children 3.0: Updated guidance for governments and businesses to create AI policies and systems that uphold children’s rights. UNICEF Innocenti – Global Office of Research and Foresight. https://www.unicef.org/innocenti/media/11991/file/UNICEF-Innocenti-Guidance-on-AI-and-Children-3-2025.pdf.

- Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37–46. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1968). Weighted kappa: Nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychological Bulletin, 70(4), 213–220. [CrossRef]

- Efron, B., & Tibshirani, R. J. (1993). An introduction to the bootstrap. Chapman & Hall/CRC. [CrossRef]

- Europol. (2024). Internet Organised Crime Threat Assessment (IOCTA) 2024. https://www.europol.europa.eu/cms/sites/default/files/documents/Internet%20Organised%20Crime%20Threat%20Assessment%20IOCTA%202024.pdf.

- European Union. (2024). Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act). Official Journal of the European Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ%3AL_202401689.

- Fleiss, J. L. (1971). Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychological Bulletin, 76(5), 378–382. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F., & Krippendorff, K. (2007). Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Communication Methods and Measures, 1(1), 77–89. [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. (2019). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (4th ed.). SAGE Publications. [CrossRef]

- MENG, WEI, 2025, “Assessing Computable Gaps in AI Governance for Children: Evidence-Mechanism-Governance-Indicator Modelling of UNICEF’s Guidance on Artificial Intelligence and Children 3.0 Using the Graph-GAP Framework Dataset”, Harvard Dataverse, V1, UNF:6:XcPOugC6JtIbzqkfhxr4RQ== [fileUNF]. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. (2023). Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0) (NIST AI 100-1). https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ai/nist.ai.100-1.pdf.

- O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19. [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P. E., & Fleiss, J. L. (1979). Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin, 86(2), 420–428. [CrossRef]

- Zapf, A., Castell, S., Morawietz, L., & Karch, A. (2016). Measuring inter-rater reliability for nominal data—Which coefficients and confidence intervals are appropriate? BMC Medical Research Methodology, 16, 93. [CrossRef]

- European Data Protection Board. (2022). Binding decision 2/2022 on the dispute submitted by the Irish supervisory authority regarding the processing of personal data of child users by Instagram (Art. 65 GDPR). https://www.edpb.europa.eu/system/files/2022-09/edpb_bindingdecision_20222_ie_sa_instagramchildusers_en.pdf.

- Federal Trade Commission. (2019). Revised complaint: United States v. Google LLC and YouTube, LLC (COPPA case). https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/cases/172_3083_youtube_revised_complaint.pdf.

- Federal Trade Commission. (2022). Complaint: United States v. Epic Games, Inc. https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/2223087EpicGamesComplaint.pdf.

- Federal Trade Commission. (2022). Stipulated order for permanent injunction and monetary judgment: United States v. Epic Games, Inc. https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/1923203epicgamesfedctorder.pdf.

- Information Commissioner’s Office. (2023). TikTok Inc monetary penalty notice. https://ico.org.uk/media2/migrated/4025182/tiktok-mpn.pdf.

- UNICEF Innocenti. (2025). Guidance on AI and children (Version 3.0). https://www.unicef.org/innocenti/media/11991/file/UNICEF-Innocenti-Guidance-on-AI-and-Children-3-2025.pdf.

| Element type | Node/Edge Name | Definition (Operationalisation) | Minimum Evidence Requirement |

| node | Foundation | 3P Fundamentals: Protection/Provision/Participation;and age-appropriate constraints |

Source Anchor + Definition |

| node | Requirement | UNICEF’s Ten Demands (R1–R10) | Source Anchor |

| node | Risk | Types of risks that may be amplified by AI (such as privacy violations, discrimination, manipulation, and exploitation) | Textual or external report evidence |

| node | Harm | Specific harm to children’s rights (psychological/social/physical/developmental, etc.) | The text explicitly points to |

| node | Control | Governance or engineering controls (assessment, audit, default security, appeal and redress, etc.) | Executable description |

| node | Metric | Auditable Metrics (Definition + Data Source + Frequency + Threshold/Benchmark) | Indicator quadruplet |

| Edge |

supports/constrains | Foundation→Requirement(Foundation support/restraint requirements) | Mapping Rules |

| Edge | mitigates | Control→Risk(Control and mitigate risks) | Control and Risk Co-domain |

| Edge | measures | Metric→Control(Indicators for Measuring Control Effectiveness) | Indicator-directed control |

| Edge | leads_to | Risk→Harm(Risk leads to injury) | Mechanism Chain Evidence |

| Requirements | Theme | E | M | G | K | GapScore | Readiness |

| R1 | Regulation, Supervision and Compliance | 3.58 | 4.32 | 4.19 | 4.55 | 4.16 | 3.0 |

| R2 | Child Safety | 3.18 | 3.22 | 4.34 | 3.88 | 3.66 | 3.0 |

| R3 | Data and Privacy | 3.17 | 4.19 | 4.67 | 4.56 | 4.15 | 1.0 |

| R4 | Non-discrimination and Fairness | 3.52 | 4.3 | 4.87 | 4.83 | 4.38 | 1.0 |

| R5 | Transparency, accountability and explainability | 4.2 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 4.5 | 3.0 |

| R6 | Responsible AI Practices and Respect for Rights | 3.81 | 4.22 | 4.19 | 4.5 | 4.18 | 1.0 |

| R7 | Best interests, development and wellbeing | 3.56 | 4.56 | 4.74 | 4.07 | 4.23 | 3.0 |

| R8 | inclusiveness(of and for children) | 3.57 | 4.7 | 4.87 | 4.48 | 4.4 | 3.0 |

| R9 | Empowerment and Skills Readiness | 3.74 | 4.57 | 4.87 | 4.67 | 4.46 | 3.0 |

| R10 | Fostering a favourable ecological environment | 3.54 | 4.58 | 4.79 | 4.6 | 4.38 | 3.0 |

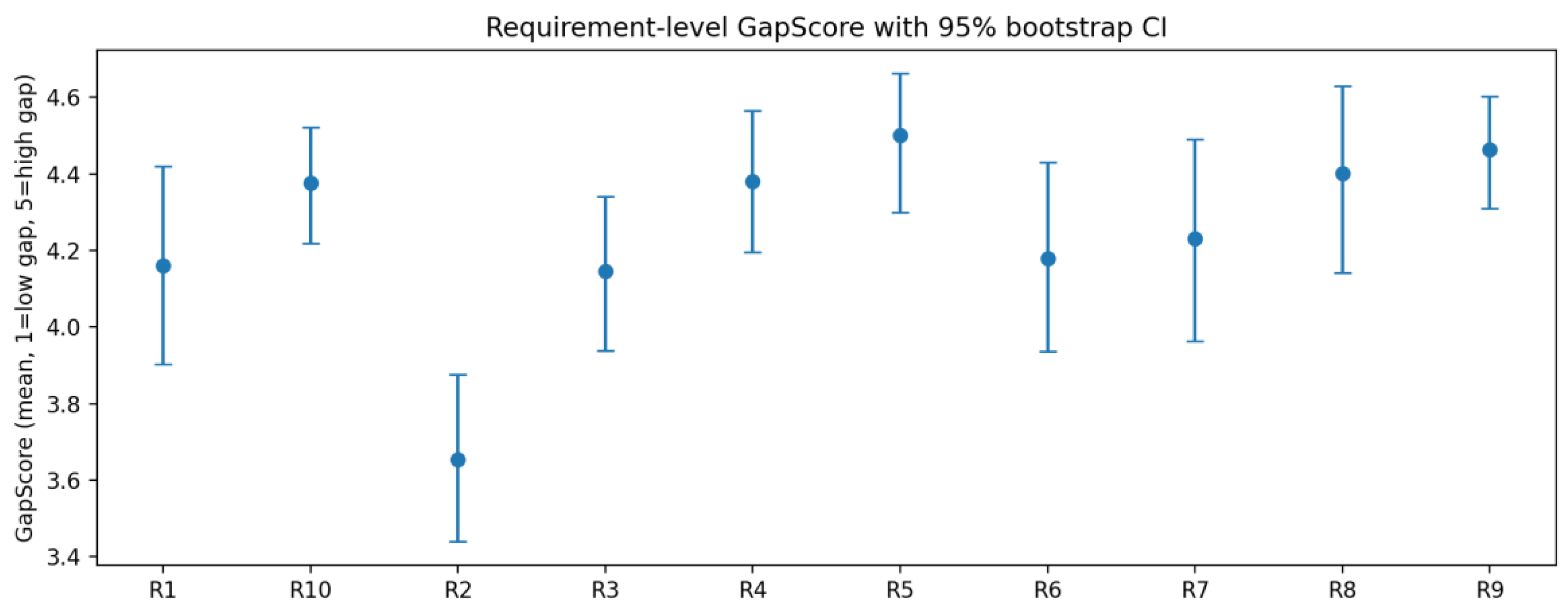

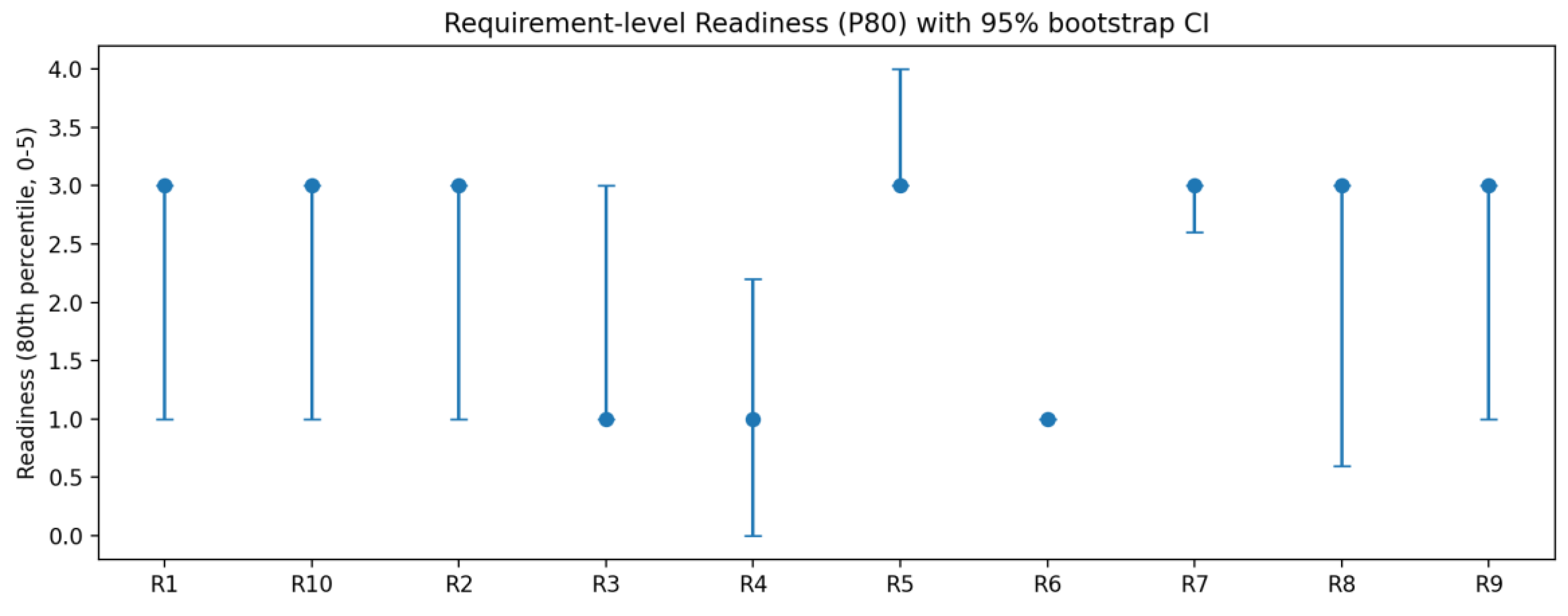

| Requirement | n | GapScore_mean |

GapScore_ 95%CI |

Readiness_P80 |

Readiness_ 95%CI(P80) |

Share (Readiness≥3) |

| R1 | 31 | 4.16 | [3.90, 4.42] | 3.0 | [1.0, 3.0] | 0.23 |

| R10 | 57 | 4.38 | [4.22, 4.52] | 3.0 | [1.0, 3.0] | 0.28 |

| R2 | 50 | 3.66 | [3.44, 3.88] | 3.0 | [1.0, 3.0] | 0.3 |

| R3 | 36 | 4.15 | [3.94, 4.34] | 1.0 | [1.0, 3.0] | 0.11 |

| R4 | 23 | 4.38 | [4.20, 4.57] | 1.0 | [0.0, 2.2] | 0.09 |

| R5 | 20 | 4.5 | [4.30, 4.66] | 3.0 | [3.0, 4.0] | 0.5 |

| R6 | 32 | 4.18 | [3.94, 4.43] | 1.0 | [1.0, 1.0] | 0.09 |

| R7 | 27 | 4.23 | [3.96, 4.49] | 3.0 | [2.6, 3.0] | 0.41 |

| R8 | 23 | 4.4 | [4.14, 4.63] | 3.0 | [0.6, 3.0] | 0.26 |

| R9 | 54 | 4.46 | [4.31, 4.60] | 3.0 | [1.0, 3.0] | 0.28 |

| Category | Determination Rules | Corresponding Requirements | Action Pack (Summary) |

| P1 Proceed without delay | GapScore≥3.50 and Readiness≥3 | R2, R4 | Building upon existing standards/processes: rapid implementation of risk mapping, red-line use cases, and audit and appeal mechanisms. |

| P2 Key challenges | GapScore≥3.50 and Readiness≤2 | R5, R6, R7, R8, R10 | Filling gaps in the indicator system and mechanism chain: Child well-being indicators, Explanatory stratification requirements, Responsibility allocation and cross-agency coordination. |

| P3 Steady-state maintenance | GapScore<3.00 and Readiness≥3 | R1, R3, R9 | Maintaining compliance and pursuing continuous improvement: data minimisation, age appropriateness, education and digital literacy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).