Submitted:

21 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

Materials and Microstructure Analyses

Atmospheric Exposure

| Environmental parameter | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | °C | 13 |

| Relative humidity | % | 84 |

| Chloride deposition | mg. m-2 day-1 | 1000 |

| SO2 | µg.m-3 | <1 |

| Precipitation, yearly | mm | 1000 |

| Distance from the sea | m | 10 |

| Time of wetness | h. year-1 | 500 |

Analyses of Corrosion Products

3. Results

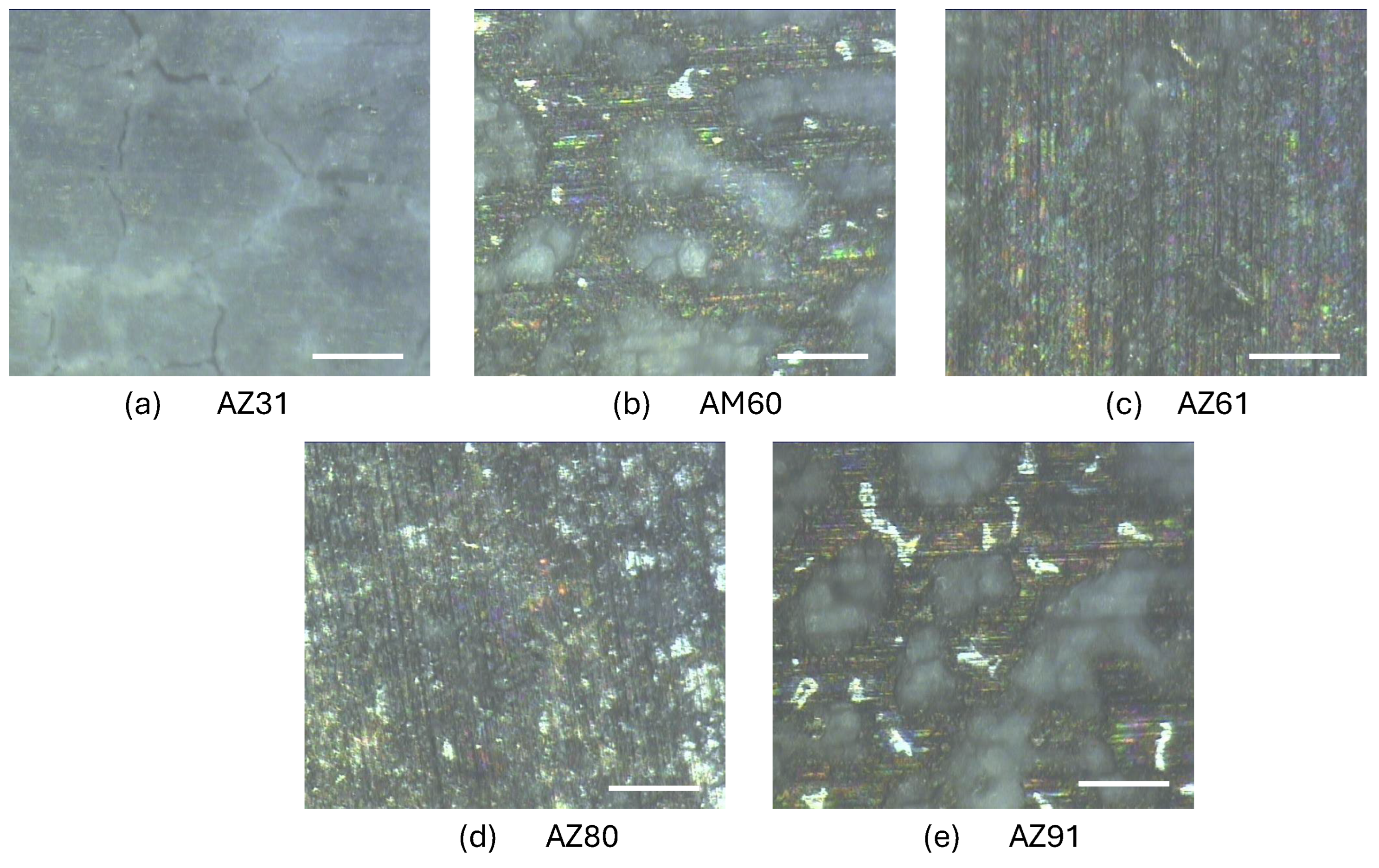

Microstructures of the Mg Alloys

| Alloy | Grain size, µm | Secondary phase, % | Main secondary phases |

|---|---|---|---|

| AZ31 | <20 and <50 | 1,5 | MnAl |

| AM60 | >100 | 2 | Al12Mg17 and AlMn |

| AZ61 | <20 | 2 | Al12Mg17 and AlMn |

| AZ80 | >25 | 2-3 | Al12Mg17 and AlMn |

| AZ91 | >200 | 12-15 | Al12Mg17, AlMn and Mg2Si |

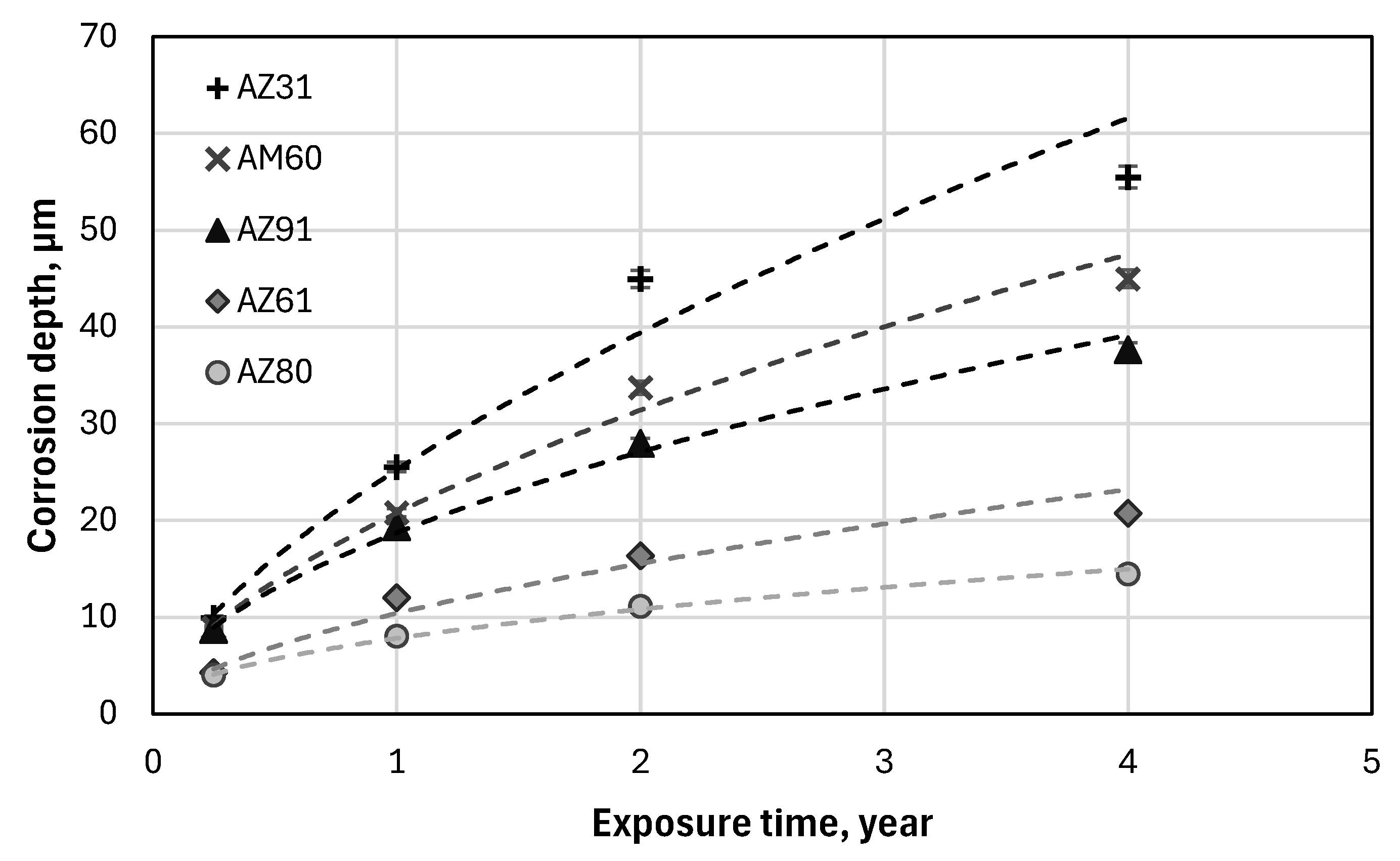

Atmospheric Corrosion Rate of the Mg Alloys

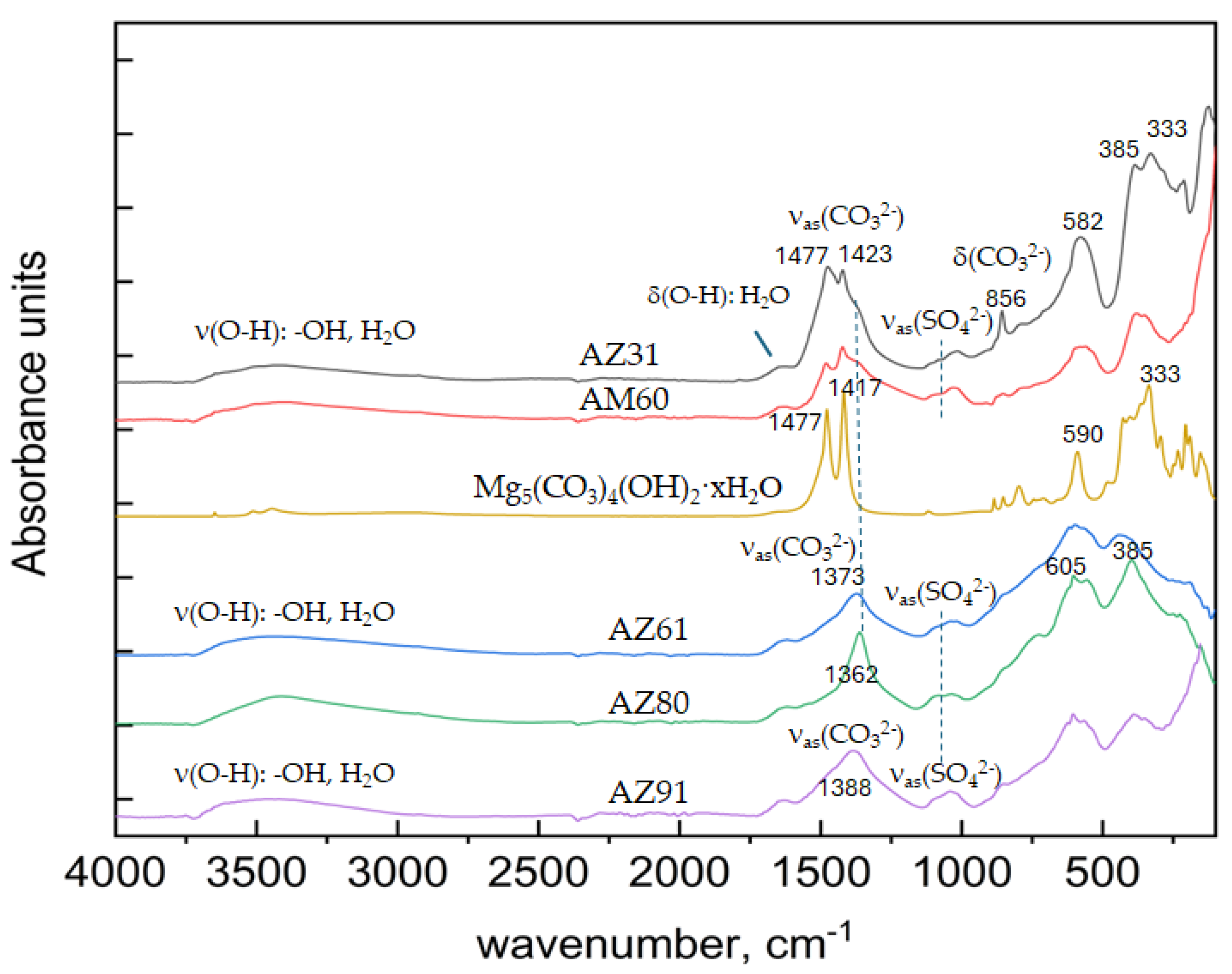

Corrosion Product Analysis

4. Discussion

Corrosion Rate of Mg Alloys

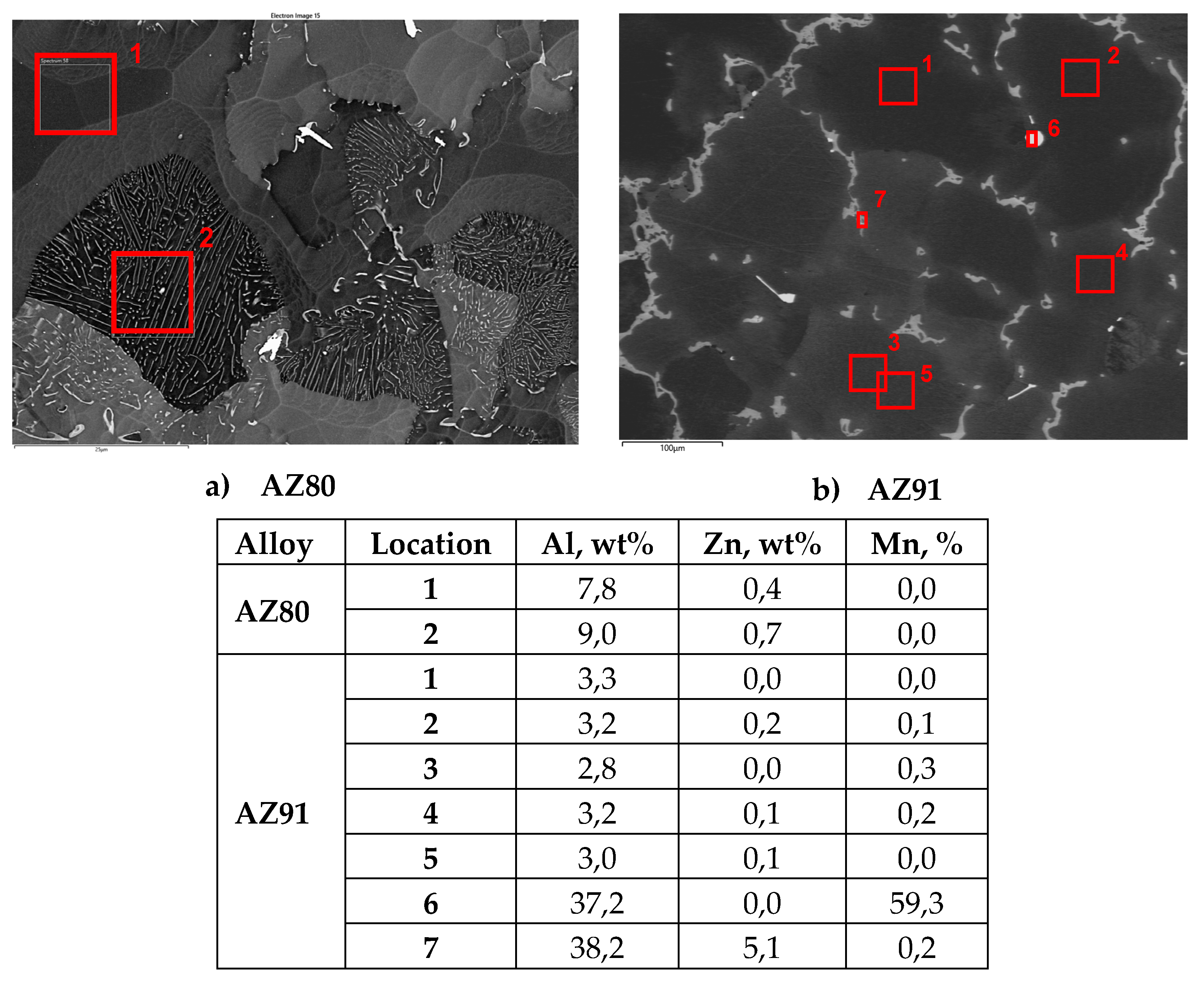

Influence of Microstructure

5. Conclusions

- The corrosion performance of the magnesium alloys under harsh marine conditions studied in this work increased in the following order: AZ31<AM60<AZ91<AZ61<AZ80. The ranking was similar at all exposure times ranging from 3 months to 4 years.

- The corrosion was highly localised during the first months of exposure and then became more generalised upon long exposure times.

- The kinetics of corrosion were rather similar for all magnesium alloys, and the corrosion loss followed a power law from which long term corrosion data can be extracted.

- Corrosion products for AZ61, AZ80 and AZ91 contained larger fractions of hydrotalcites whereas AZ31 and AM60 showed more formation of magnesium hydroxy carbonate

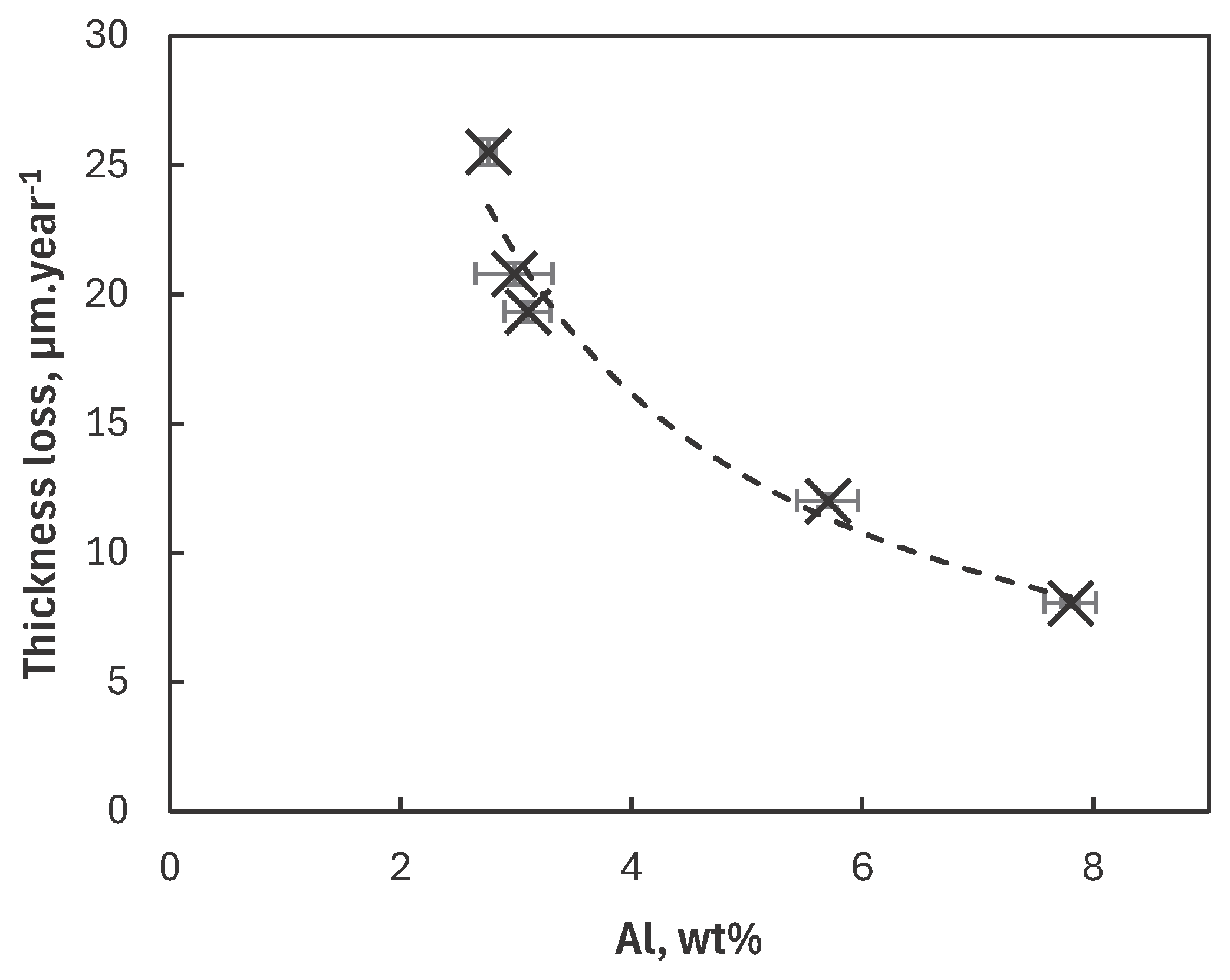

- A clear correlation between the Al content in the α-Mg phase and the corrosion loss was observed indicating that this parameter is strongly governing the corrosion rate of magnesium alloys under atmospheric corrosion conditions.

Acknowledgments

References

- Song, G.-L. Corrosion electrochemistry of magnesium (Mg) and its alloys. In Corrosion of Magnesium Alloys; Song, G.L., Ed.; Woodhead: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 3–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ghali, E. Activity and passivity of magnesium (Mg) and its alloys. In Corrosion of Magnesium Alloys; Song, G.L., Ed.; Woodhead: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 66–109. [Google Scholar]

- Atrens, A.; Liu, M.; Zainal Abidin, N.I.; Song, G.-L. Corrosion of magnesium alloys and metallurgical influence alloys. In Corrosion of Magnesium Alloys; Song, G.L., Ed.; Woodhead: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 117–161. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Song, G.-L.; Atrens, A.; Dargusch, M. What activates the Mg surface—A comparison of Mg dissolution mechanisms. J. Mat. Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.-L.; Atrens, A. Recently deepened insights regarding Mg corrosion and advanced engineering applications of Mg alloys. J. Magnes. Alloys 2023, 11, 3948–3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBozec, N.; Jönsson, M.; Thierry, D. Atmospheric corrosion of magnesium alloys: influence of temperature, relative humidity, and chloride deposition. Corrosion 2004, 60, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendahl, B; LeBozec, N. Assessment of corrosivity of global vehicle environment; Research Report Swerea KIMAB Stockholm: Sweden, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo, M.C. Merino, A.E. Coy, R. Arrabal, F. Viejo, E. Matykina, Corrosion behavior of magnesium/aluminum alloys in 3,5 wt% NaCl. Corrosion Sci. 2008, 50, 823–834. [CrossRef]

- Esmaily, M.; Svensson, J.E.; Fajardo, S.; Birbilis, N.; Frankel, G.S.; Virtanen, S.; Arrabal, R.; Thomas, S.; Johansson, L.G. Fundamentals and advances in magnesium alloy corrosion. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2017, 89, 92–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaily, M.; Blucher, D.B.; Svensson, J.E.; Halvarsson, M.; Johansson, L.G. New insight in the corrosion of magnesium alloys- The role of aluminum. Scr. Mater. 2016, 115, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliu, Jr; Maffiotte, C.; Galván, J.C.; Barranco, V. Corros. Sci. 2011, 53, 1865–1872. [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, M.; Persson, D. The influence of the microstructure on the atmospheric corrosion behaviour of magnesium alloys AZ91D and AM50. Corros. Sci. 2010, 52, 1077–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, M.C.; Pardo, A.; Arrabal, S.; Merino, S.; Casajús, P.; Mohedano, M. Influence of chloride ion concentration and temperature on the corrosion of Mg–Al alloys in salt fog. Corros. Sci. 2010, 52, 1696–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.-q.; Shan, D.-y.; Han, E.-h.; Ke, W. Influence of NaCl deposition on atmospheric corrosion behavior of AZ91 magnesium alloy. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2010, 20, 670–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Li, X.; Xiao, K.; Dong, C. Atmospheric corrosion of field-exposed AZ31magnesium in a tropical marine environment. Corrosion Sci. 2013, 76, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yang, L.; Wang, M.; Sun, C.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Li, J. Corrosion behavior of AZ91 magnesium alloys in harsh marine atmospheric environment in South China Sea. Journal of Material Research and Technology 2025, 35, 2477–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.H.; Cao, F.Y.; Zhao, C.; Yao, J.H.; Wang, J.J.; Wang, Z.M.; Zou, Z.W.; Zheng, D.J.; Cai, J.L.; Song, G.L. The marine atmospheric corrosion of pure Mg and Mg alloys in field exposure and lab simulation. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.S.; Hotta, M. Atmospheric corrosion behavior of field-exposed magnesium alloys: Influences of chemical composition and microstructure. Corros. Sci. 2015, 100, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Li, X.; Xiao, K.; Dong, C. Atmospheric corrosion of field-exposed AZ31 magnesium in a tropical marine environment. Corrosion Science 2013, 76, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, W.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Q.; Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yang, L. Research on Dynamic Marine Atmospheric Corrosion Behavior of AZ31 Magnesium Alloy. Metals 2022, 12(11), 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Cao, X.J.; Ning, S.Q.; Zhu, L.P. Influence of Different Environments on Atmospheric Corrosion of AZ61 Magnesium Alloy. China Surf. Eng. 2015, 28, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.W.; Dai, J.M.; Sun, S. A comparative study on the corrosion behaviour of AZ80 and EW75 Mg alloys in industrial atmospheric environment. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 38, 108263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wu, S.; Liu, H.; Yang, L.; Chen, T.; Wang, X; Li, Y. Research on Comparative Marine Atmospheric Corrosion Behavior of AZ31 Magnesium Alloy in South China Sea. Materials 2025, 18(15), 3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yang, L.; Liu, H.; Wang, X; Li, Y; Huang, Y. Recent Progress on Atmospheric Corrosion of Field-Exposed Magnesium Alloys. Metals 2024, 14(9), 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.H.; Cao, F.Y.; Zhao, C.; Yao, J.H.; Wang, J.J.; Wang, Z.M.; Zou, Z.W.; Zheng, D.J.; Cai, J.L.; Song, G.L. The marine atmospheric corrosion of pure Mg and Mg alloys in field exposure and lab simulation. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, M.; Persson, D.; Leygraf, C. Atmospheric corrosion of field-exposed magnesium alloys AZ91D. Corrosion Sci 2008, 50(5), 1406–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwell, C.R.; Alexander, A.L.; Hummer, C.W. Corrosion of metals in tropical environments-aluminium and magnesium. Mater. Perform. 1965, 4, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Corvo, F.; Perez, T.; Dzib, L.R.; Martin, Y.; Castaneda, A.; Gonzalez, E.; Perez, J. Outdoor–indoor corrosion of metals in tropical coastal atmospheres Corros. Sci. 2008, 50, 220–230. [Google Scholar]

- DelaFuente, D.; Otero-Huerta, E.; Morcillo, M. Studies of long-term weathering of aluminium in the atmosphere. Corrosion Science 2007, 49, 3134–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natesan, M.; Venkatachari, G.; Palaniswamy, N. Kinetics of atmospheric corrosion of mild steel, zinc, galvanized iron and aluminium at 10 exposure stations in India. Corrosion Science 2006, 48, 3584–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafuente, B.; Downs, R. T.; Yang, H.; Stone, N. The power of databases: the RRUFF project. In Highlights in Mineralogical Crystallography; Armbruster, T, Danisi, R M, Eds.; W. De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, R.L.; Spratt, H.J.; Palmer, S.J. Infrared and near-infrared spectroscopic study of synthetic hydrotalcites with variable divalent/trivalent cationic ratios. Spectrochim. Acta A 2009, 72, 984–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, D.; Wärnheim, A.; Le Bozec, N.; Thierry, D. Studies of Initial Atmospheric Corrosion of Magnesium Alloys AZ91 and AZ31 with Infrared Spectroscopy Techniques. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2025, 6(4), 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrabal, R.; Pardo, A.; Merino, M.C.; Merino, S.; Mohedano, M.; Casajús, P. Corrosion behaviour of Mg/Al alloys in high humidity atmospheres. Mater. Corros. 2011, 62, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunder O; Lein J.E. ; Aune T. Kr.; Nisancioglu K., The rôle of Mg1>Al12 phase in the corrosion of magnesium alloy AZ91. Corrosion 1989, 45, 741. [CrossRef]

- Warner, T.J.; Thorne, N.A.; Nussbaum, G.; Stobbs, W.M. A cross-sectional TEM study in corrosion initiation in rapidly solidified Mg-based ribbons. Surf. Interf. Anal 1992, 19, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.K.; Uan, J.Y. Formation of Mg,Al-hydrotalcite conversion coating on Mg alloy in aqueous HCO3-/CO3 2- and corresponding protection against corrosion by the coating. Corrosion Science 2009, 51, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element in wt% | |||||||

| Material | Al | Zn | Mn | Si | Cu | Fe | Ni |

| AZ31 | 3.28 | 0.98 | 0.29 | 0.0089 | 0.0085 | 0.0024 | 0.00067 |

| AM60 | 6.08 | 0.041 | 0.362 | 0.0123 | 0.0003 | 0.0005 | 0.0006 |

| AZ61 | 6.85 | 0.98 | 0.33 | 0.023 | 0.0023 | 0.0025 | 0.00076 |

| AZ80 | 8.6 | 0.51 | 0.22 | 0.01 | <0.0005 | 0.005 | 0.0005 |

| AZ91 | 8.97 | 0.82 | 0.0087 | 0.008 | 0.0079 | 0.0058 | 0.00067 |

| Alloy | Corrosion products |

|---|---|

| AZ31 | Mg5(CO3)4(OH)2·xH2O, Mg6Al2CO3(OH)16·4H2O, Mg/Al-SO42- |

| AM60 | Mg5(CO3)4(OH)2·xH2O, Mg6Al2CO3(OH)16·4H2O, Mg/Al-SO42- |

| AZ61 | Mg6Al2CO3(OH)16·4H2O, Mg/Al-SO42- |

| AZ80 | Mg6Al2CO3(OH)16·4H2O, Mg/Al-SO42- |

| AZ91 | Mg6Al2CO3(OH)16·4H2O, Mg/Al-SO42- (Mg5(CO3)4(OH)2·xH2O) |

| Alloy | 3 months | 1 year | 2 years | 4 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AZ31 | 50 | 120 | 150 | 180 |

| AM60 | 40 | 100 | 120 | 150 |

| AZ61 | 15 | 35 | 45 | 55 |

| AZ80 | 10 | 30 | 35 | 45 |

| AZ91 | 30 | 90 | 100 | 120 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.