Submitted:

16 September 2025

Posted:

17 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

2.2. Exposure Conditions

2.3. In Situ Infrared Reflection Absorption Spectroscopy

2.4. FTIR-ATR FPA Imaging

2.5. AFM-IR

2.6. Scanning Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy (SKPFM)

2.7. SEM-EDS

3. Results

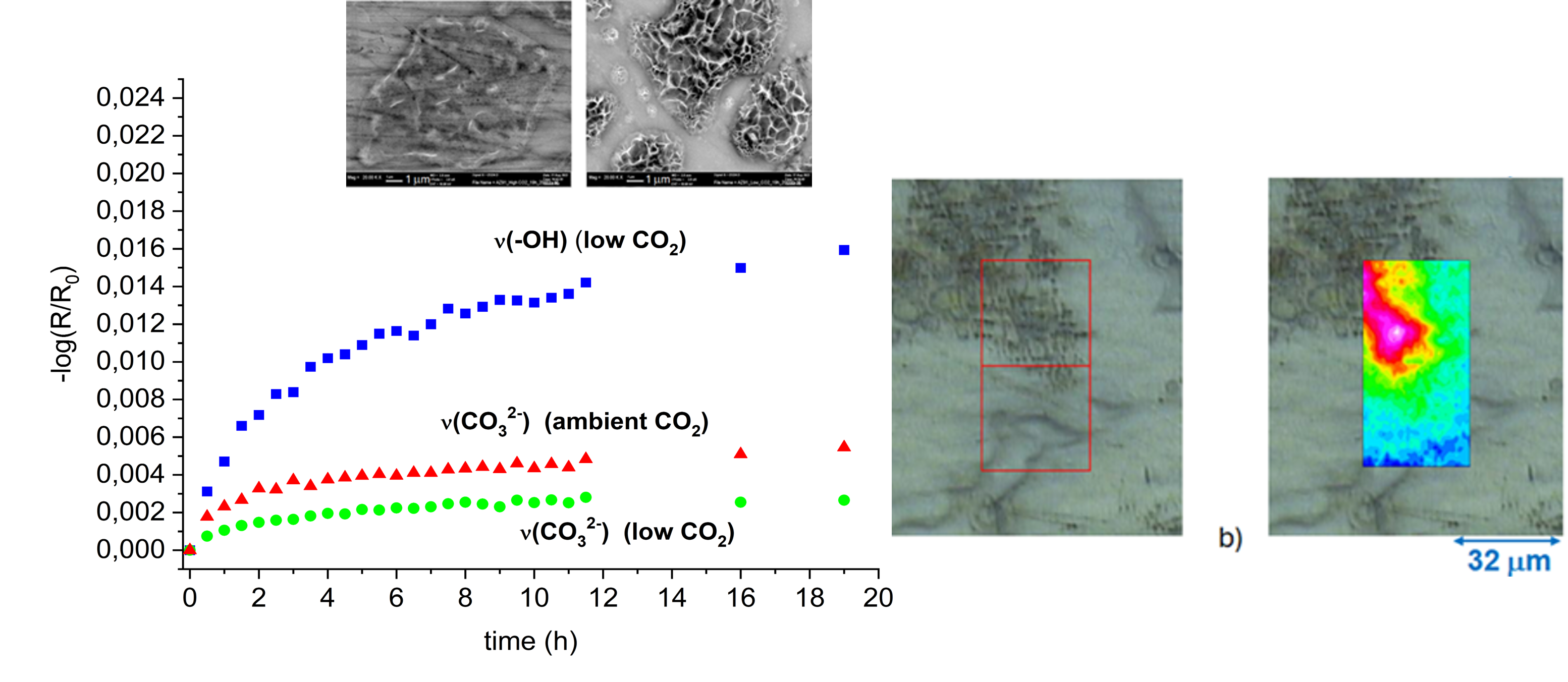

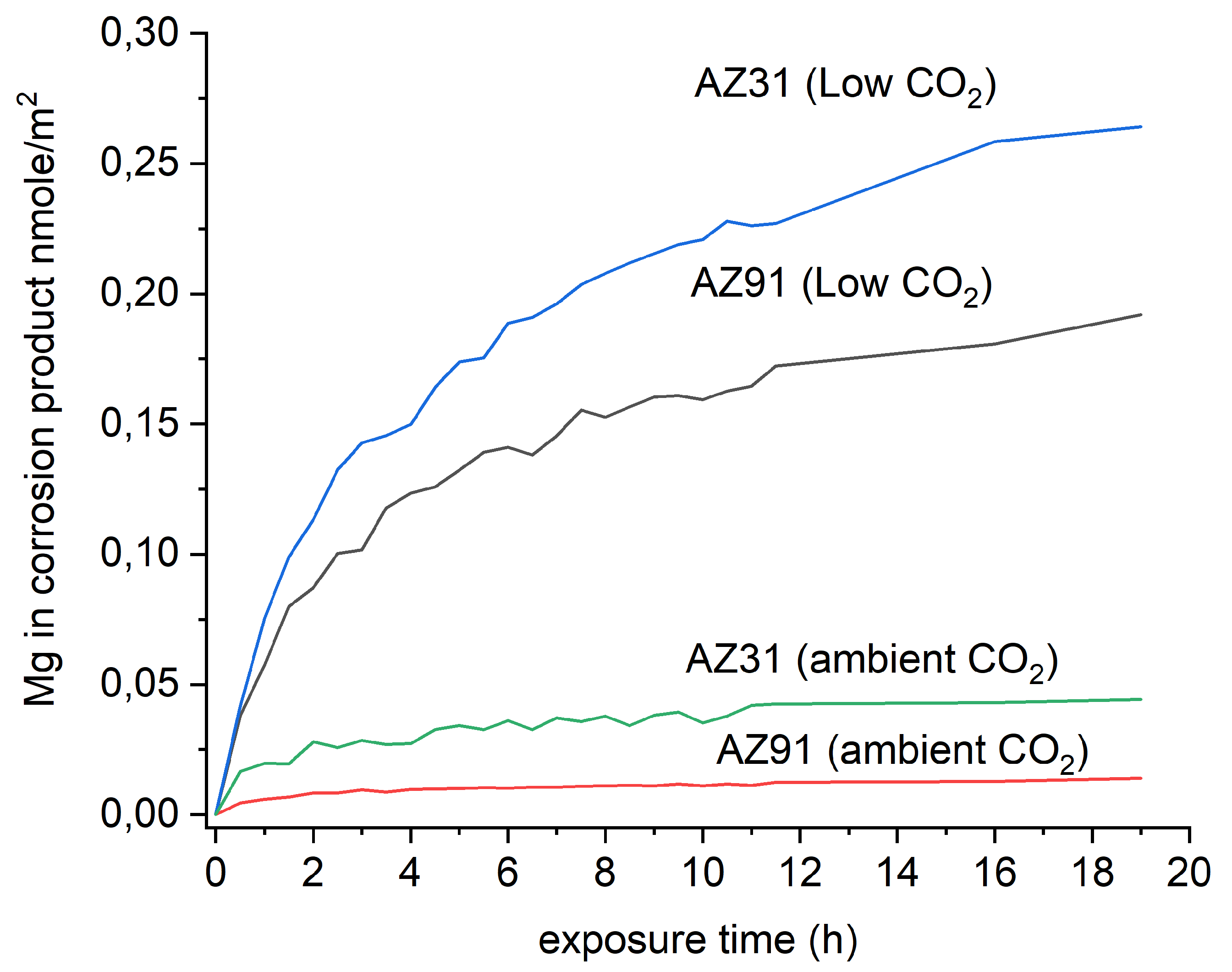

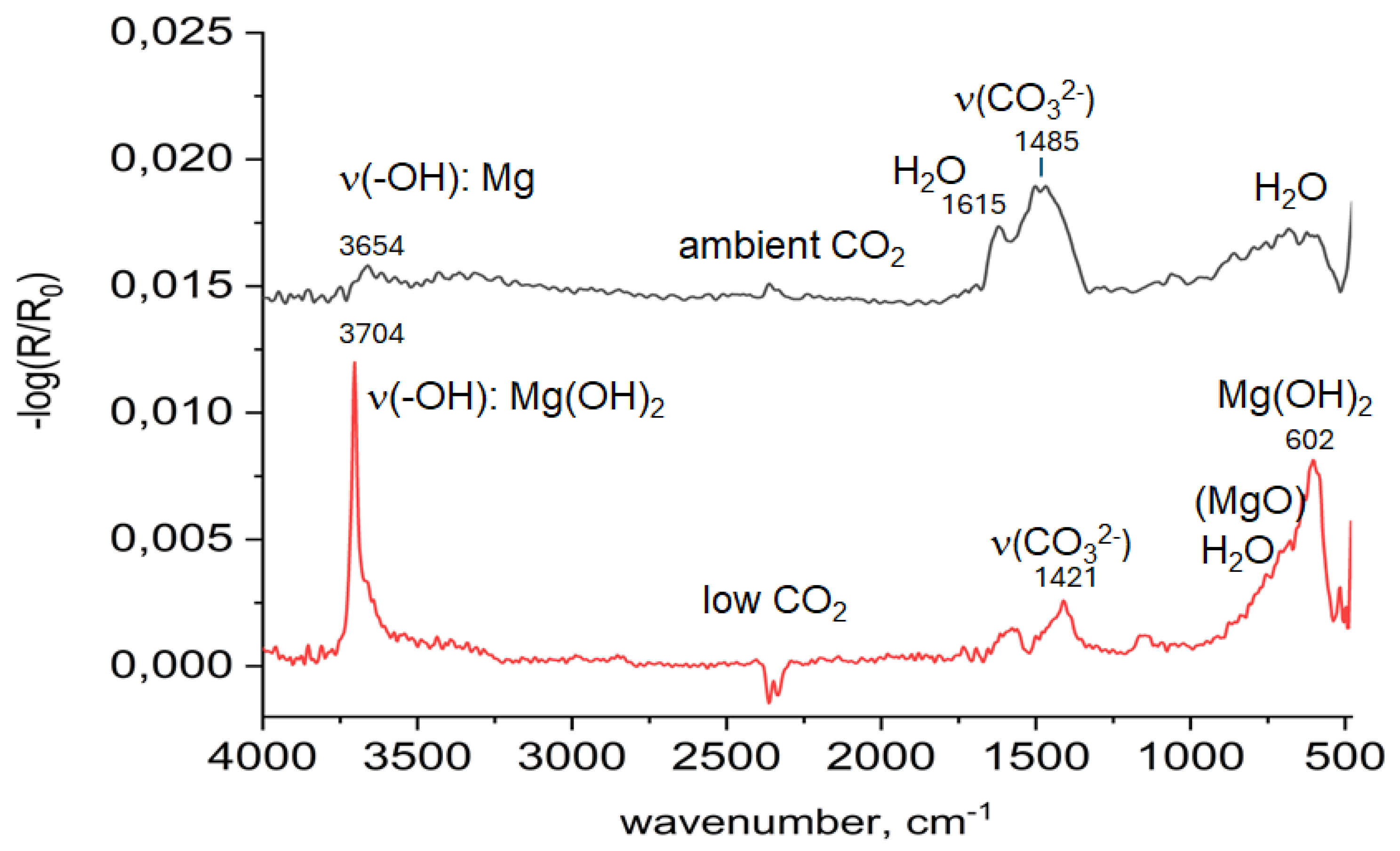

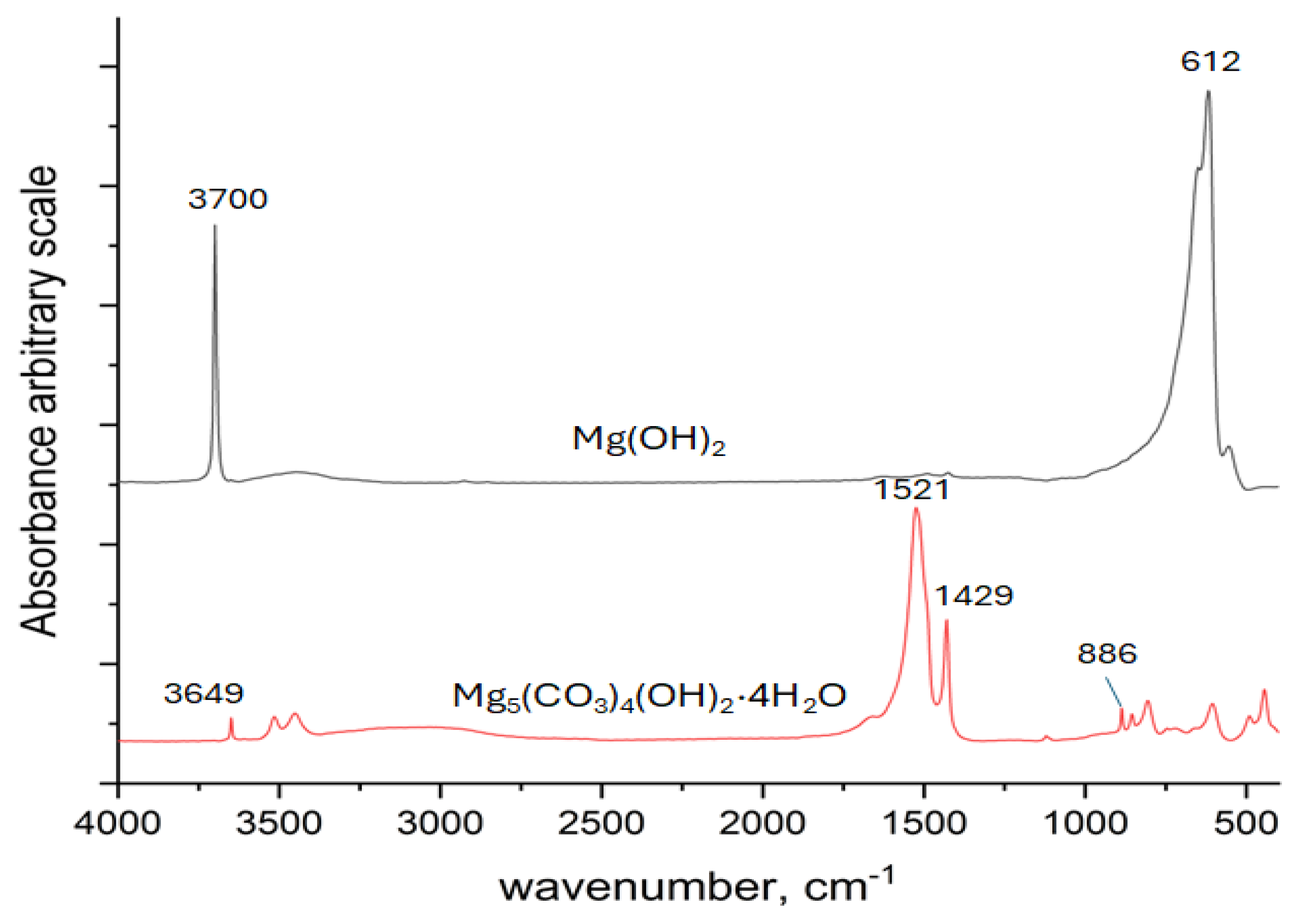

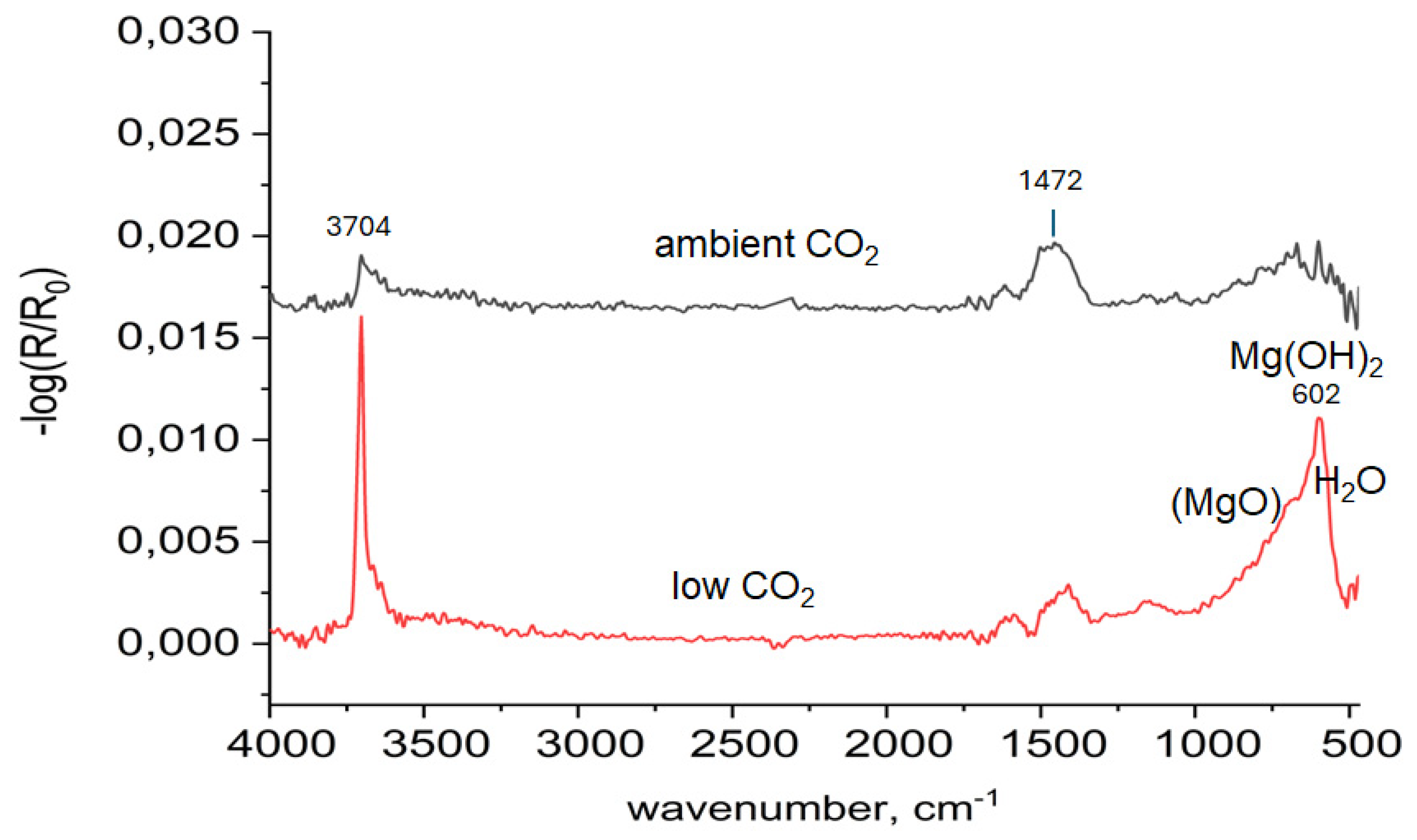

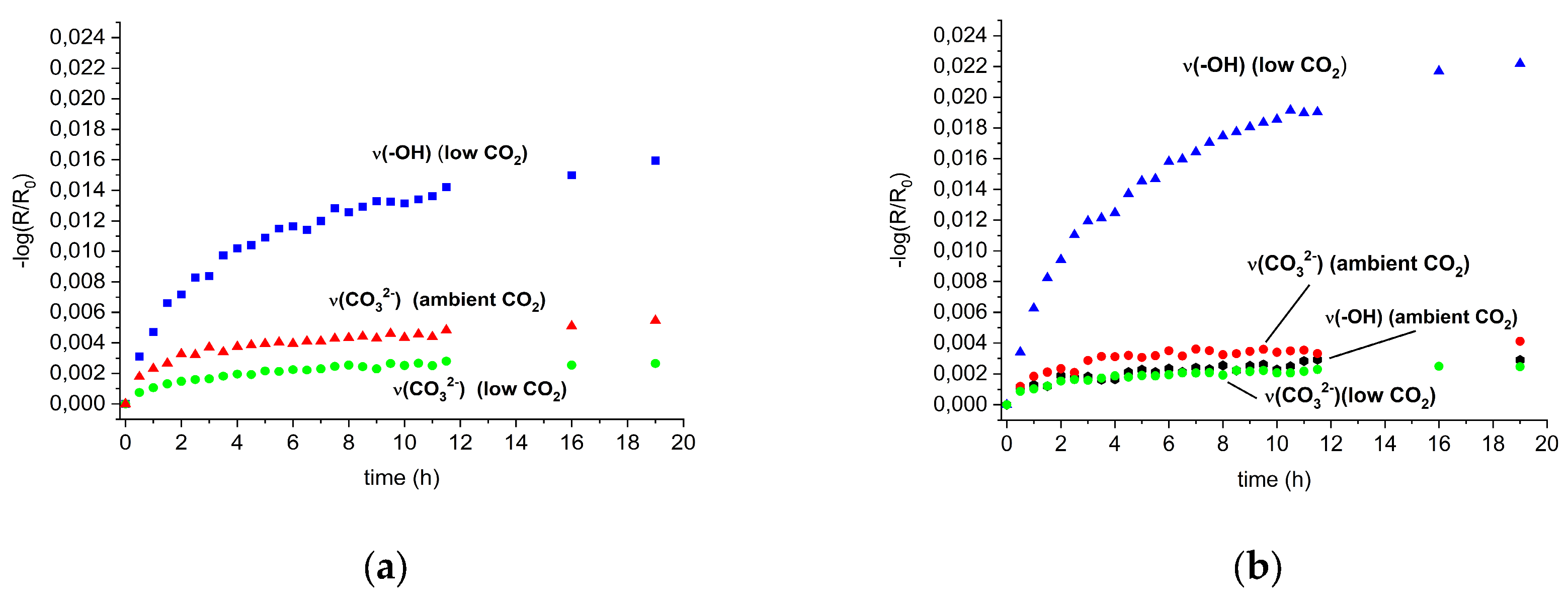

3.1. In Situ Infrared Reflection Absorption Spectroscopy

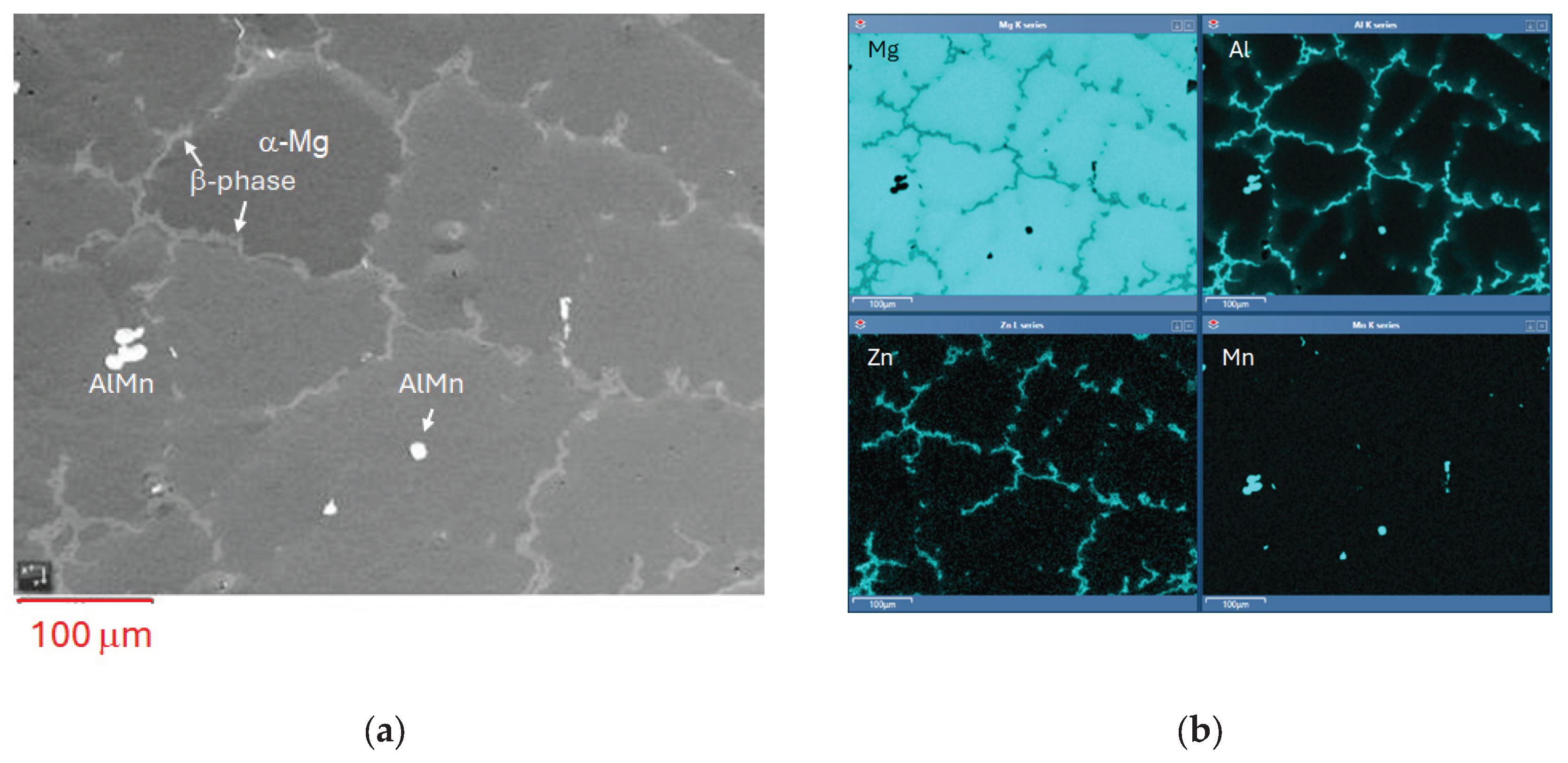

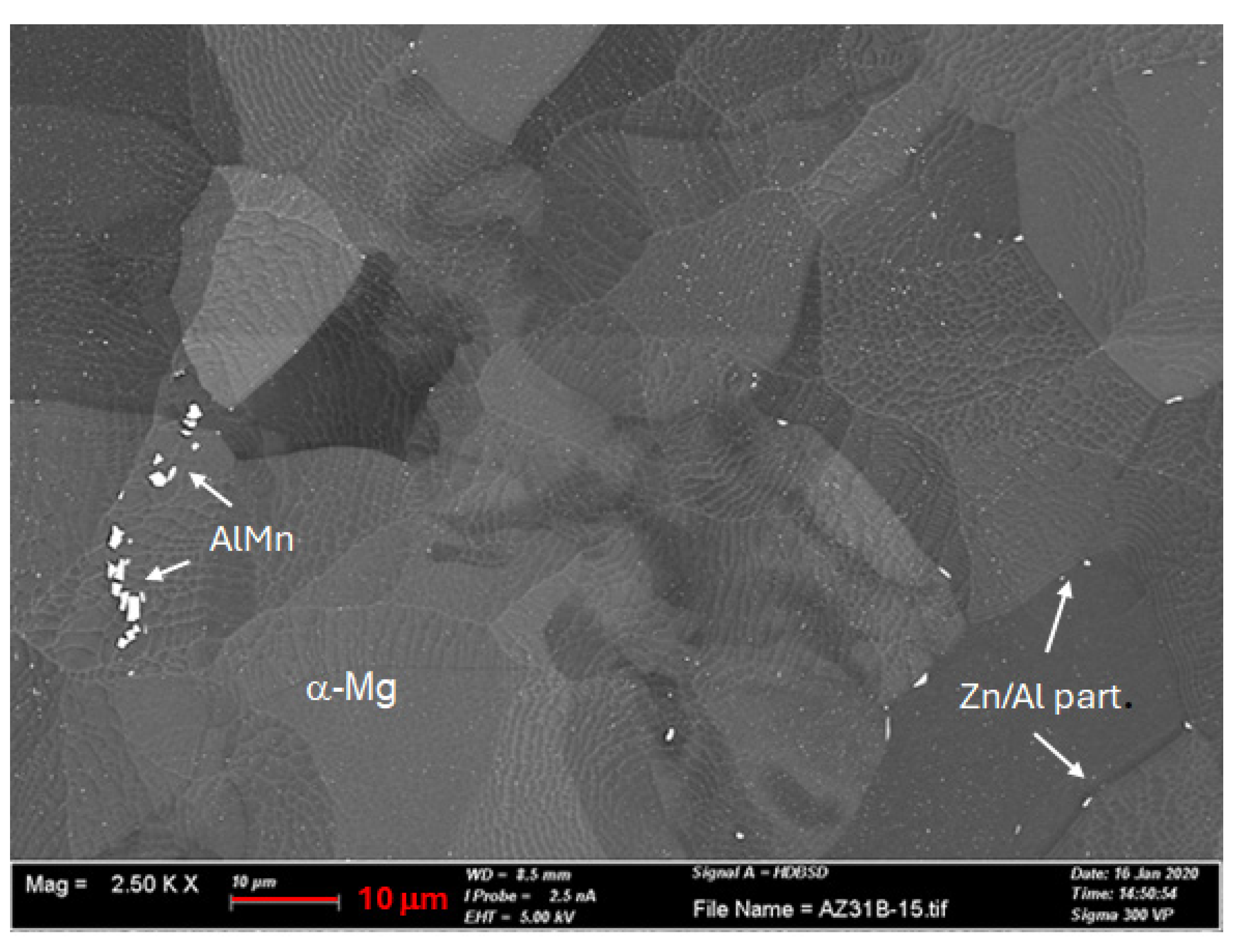

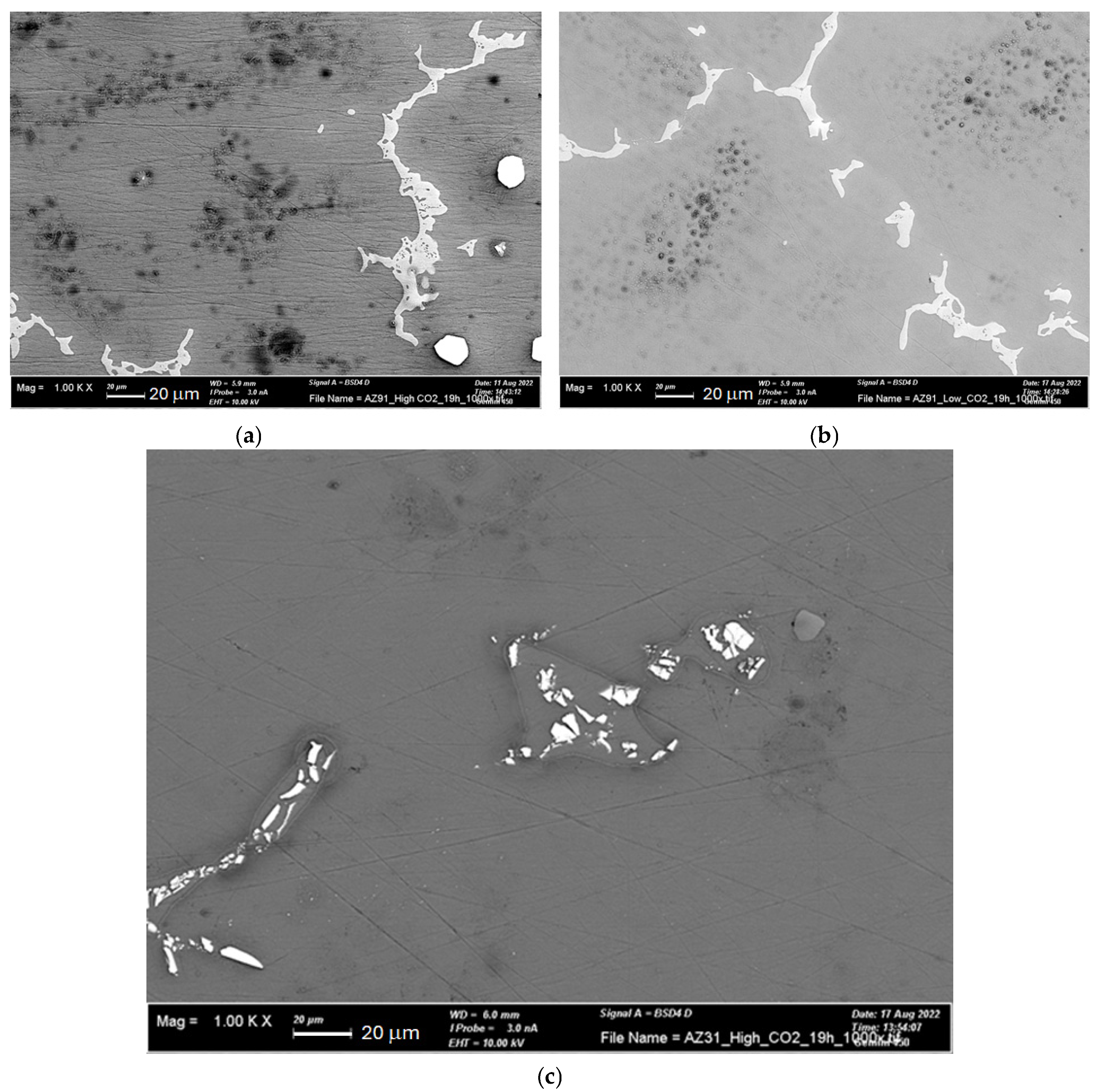

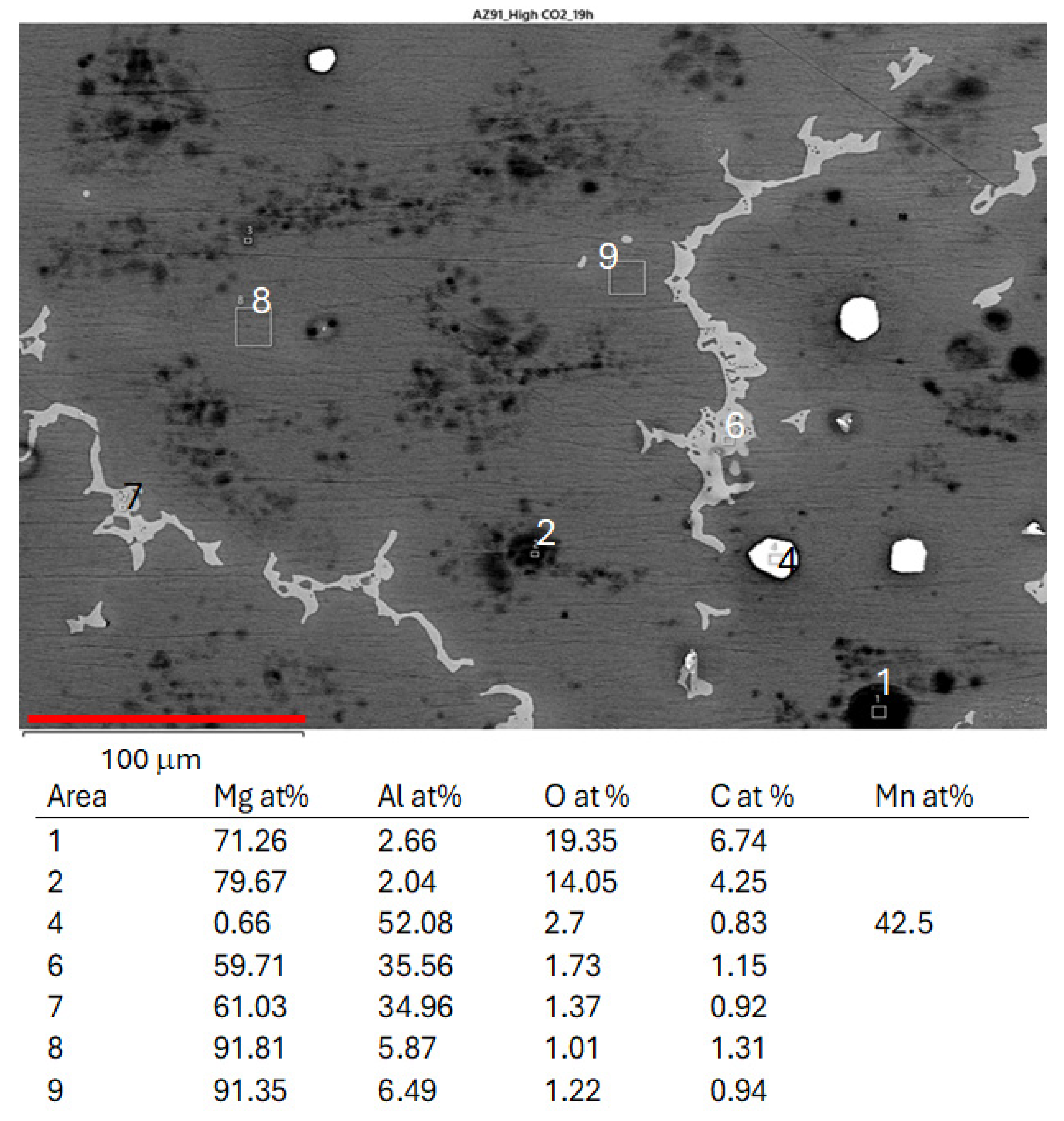

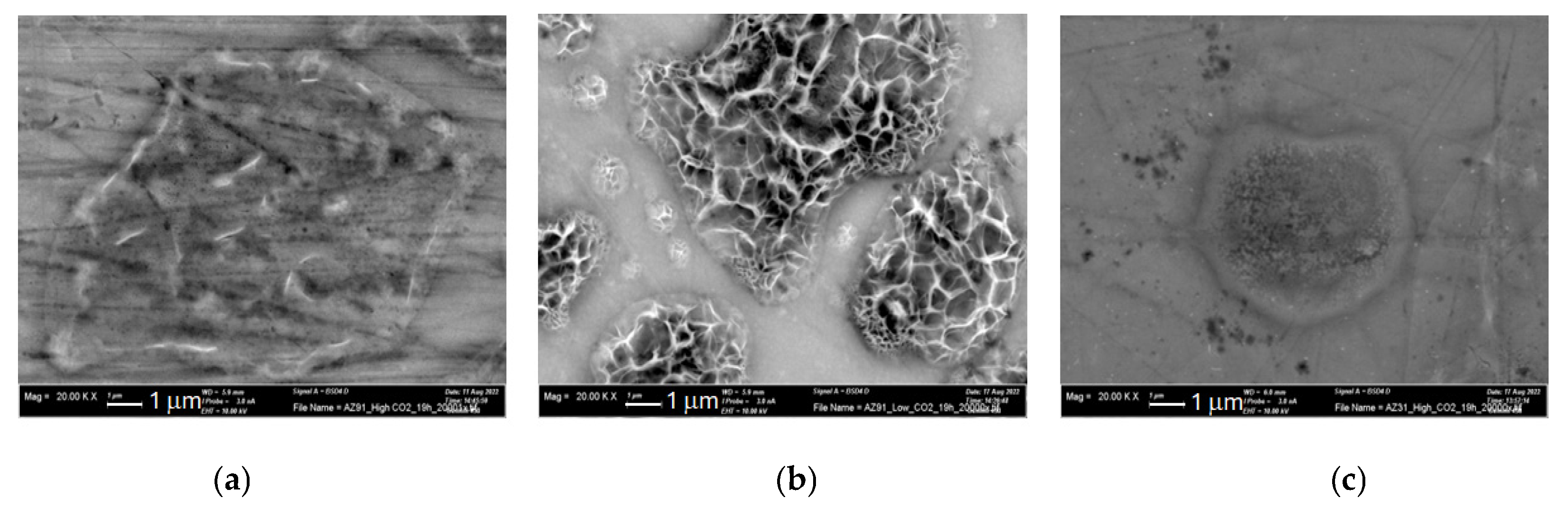

3.2. SEM-EDS

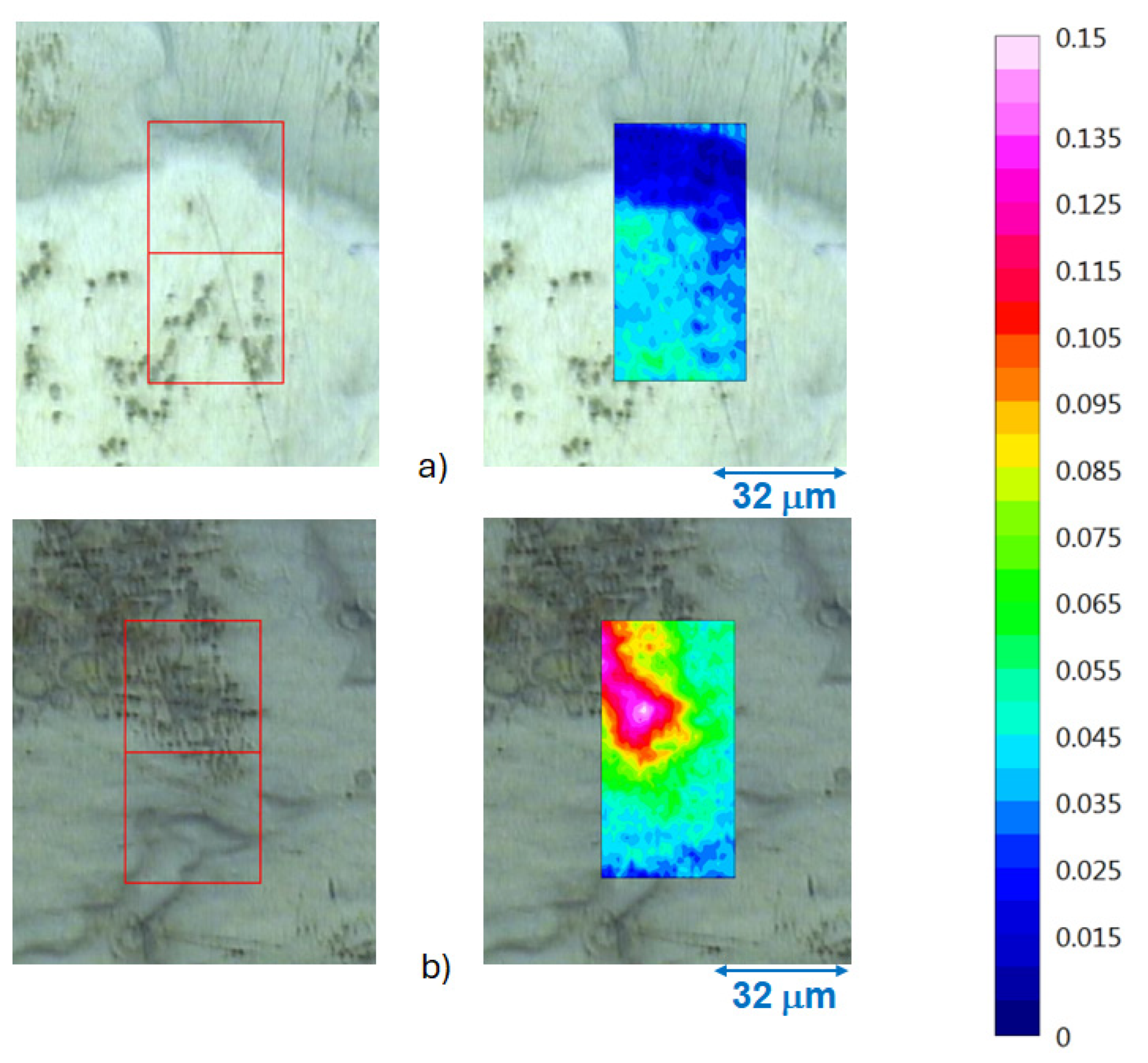

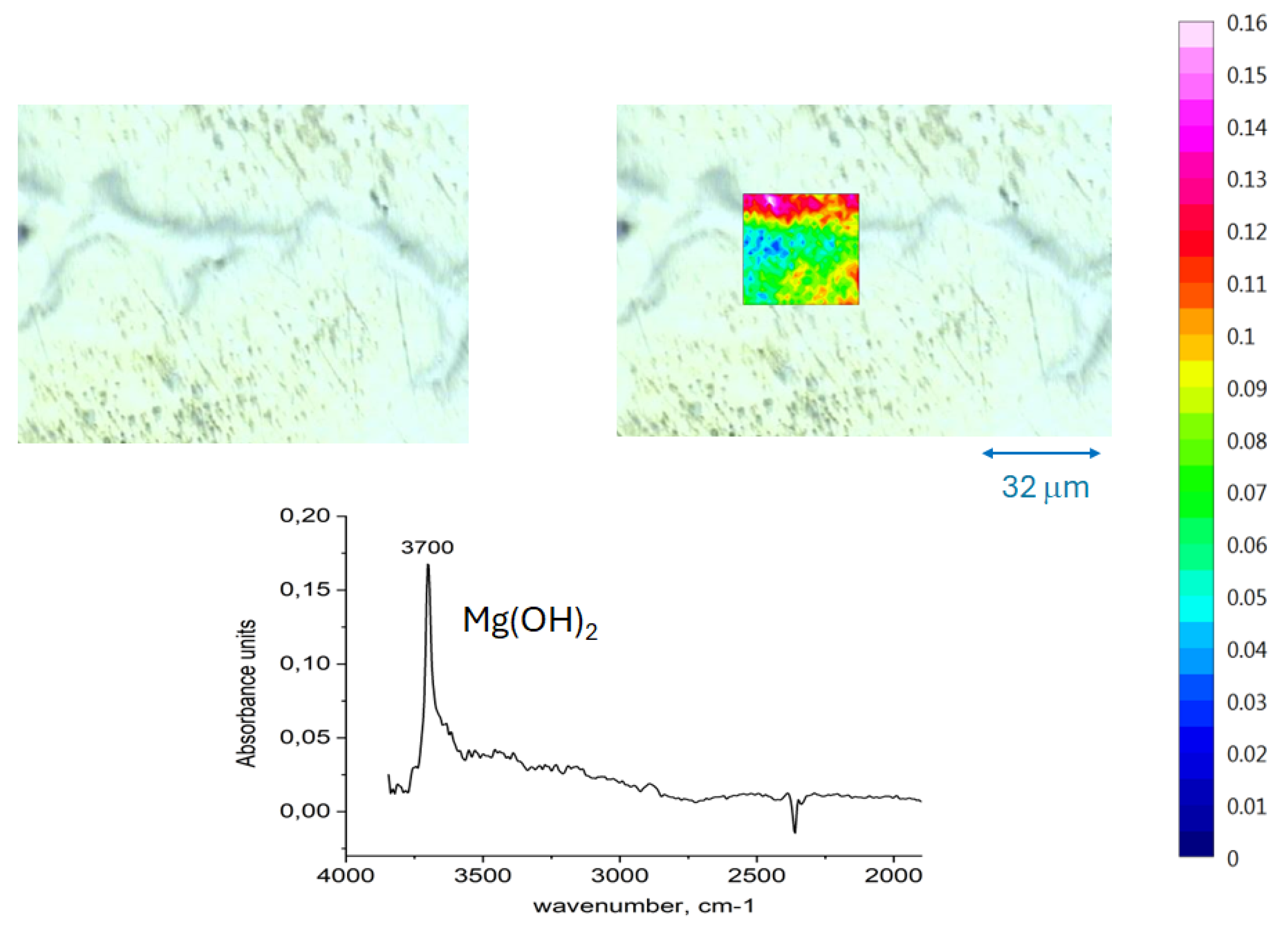

3.3. Infrared Spectroscopy Chemical Imaging

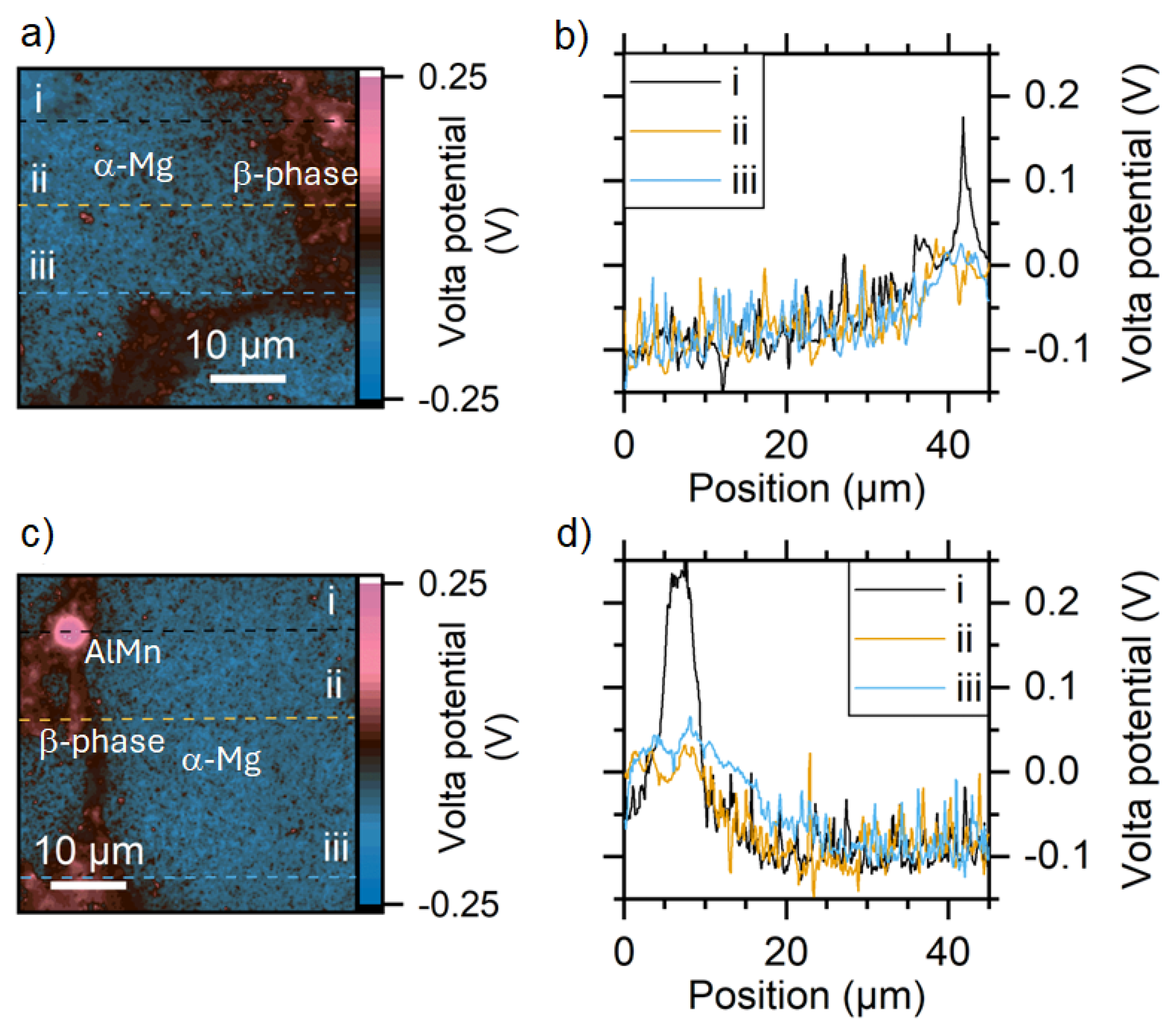

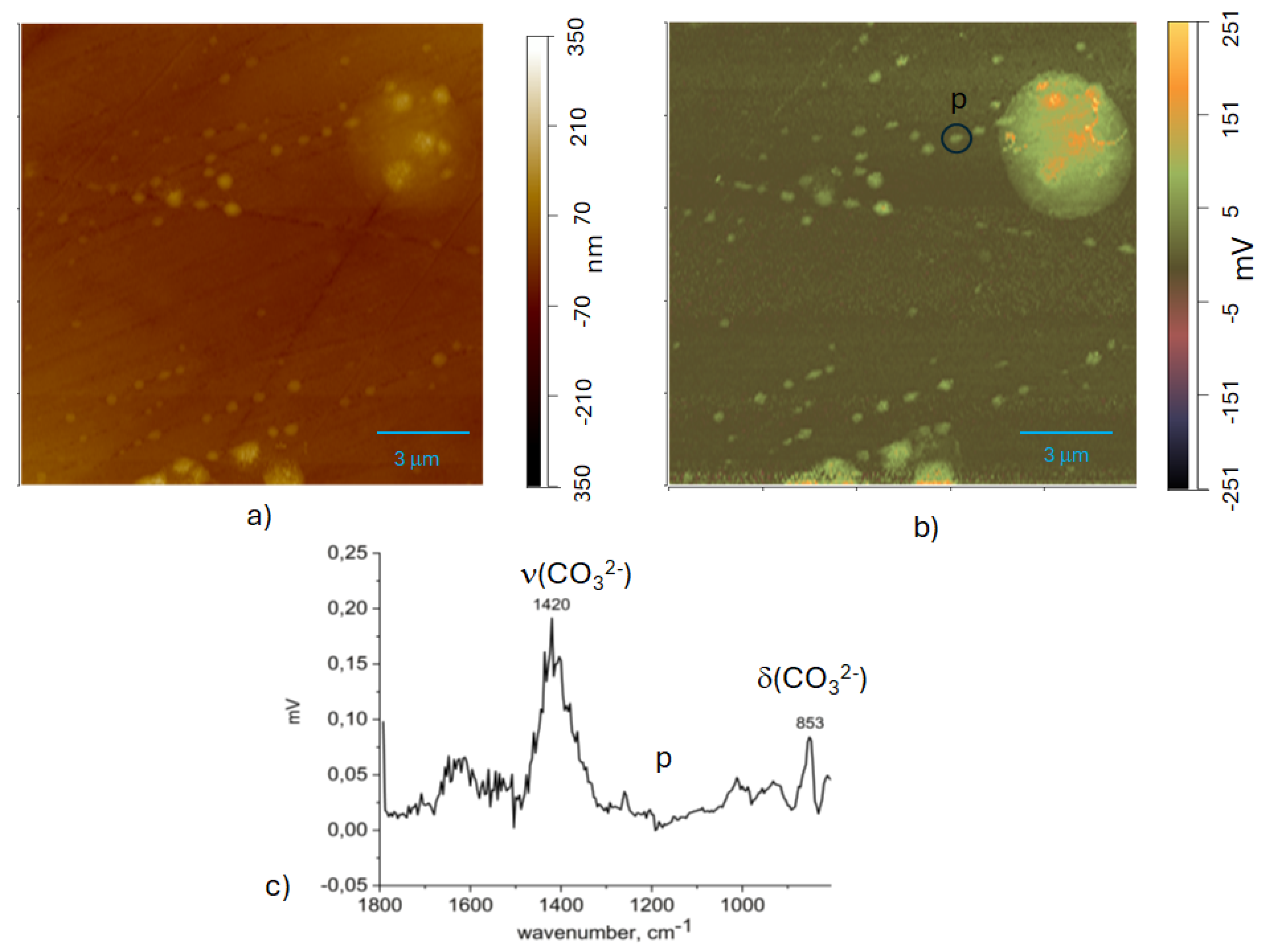

3.4. Scanning Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy Measurements

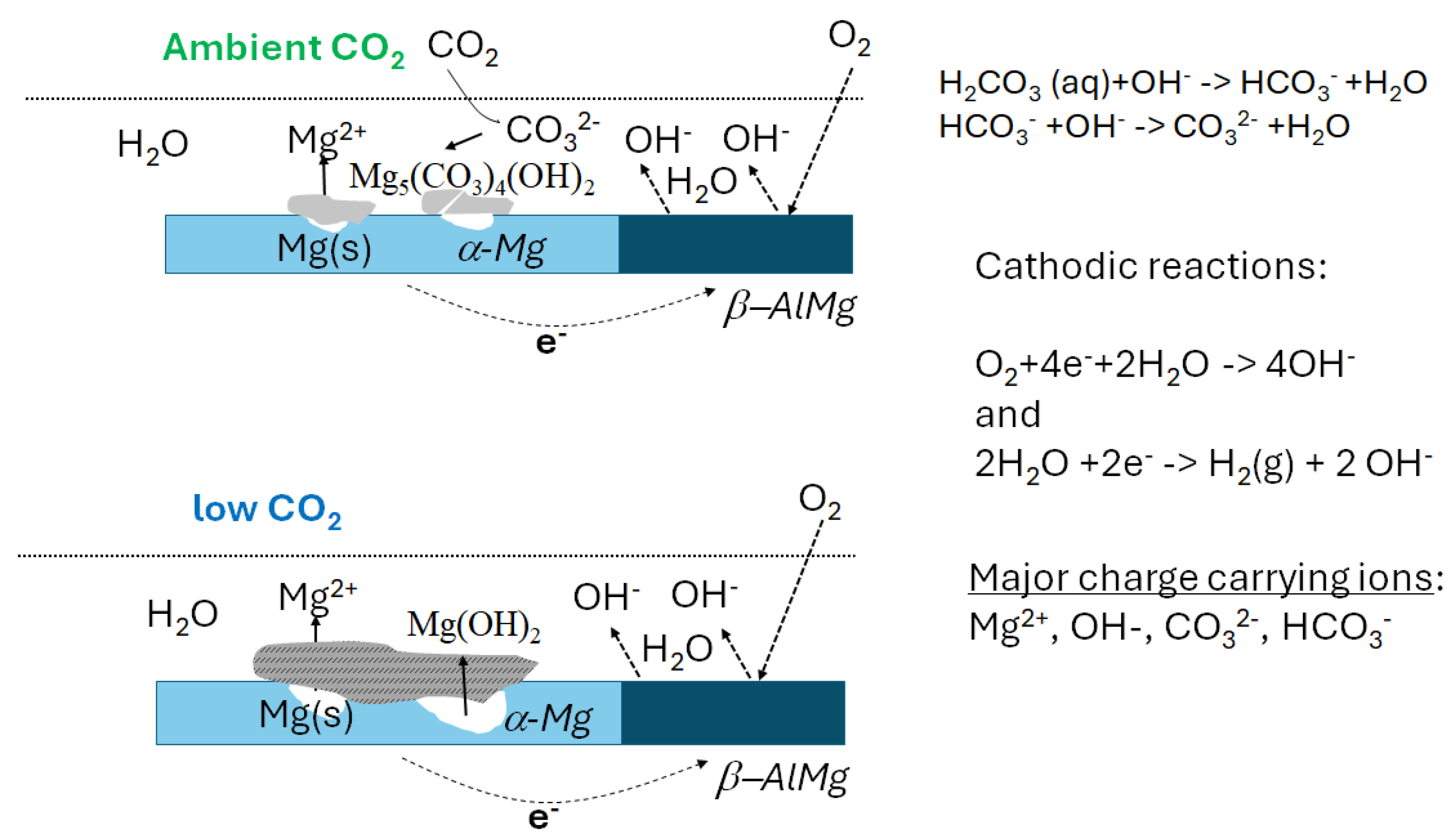

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- L. Zhan, C. Kong, C. Zhao, X. Cui, L. Zhang, Y. Song, Y. Lu, L. Xia, K. Ma, H. Yang , S. Shu, B. Dong, F. Qiu, Q. Jiang, Recent advances on magnesium alloys for automotive cabin components: Materials, applications, and challenges, J. Mater. Res. Technol., 2025, 36, 9924–9961. [CrossRef]

- M. N. Ashraf, Z. Guo, R. Wu, W. Jhiao, M. X. Chun, and A. A. Khan Gorar, Historical Progress in Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Effectiveness of Conventional Mg Alloys Leading to Mg-Li-Based Alloys: A Review, Adv. Eng. Mater., 2023, 25 2300732. [CrossRef]

- G.-L. Song, Corrosion electrochemistry of magnesium (Mg) and its alloys in: G.L. Song (Ed.), Corrosion of Magnesium Alloys, Woodhead, Cambridge, 2011, pp. 3–65.

- E. Ghali, Activity and passivity of magnesium (Mg) and its alloys in: G.L. Song (Ed.), Corrosion of Magnesium Alloys, Woodhead, Cambridge, 2011, pp. 66–109.

- A. Atrens, M.Liu, N.I. Zainal Abidin, G.-L. Song, Corrosion of magnesium alloys and metallurgical influence alloys in: G.L. Song (Ed.), Corrosion of Magnesium Alloys, Woodhead, Cambridge, 2011, pp. 117-1 61.

- J.Huang, G.-L. Song, A. Atrens, M. Dargusch, What activates the Mg surface—A comparison of Mg dissolution mechanisms, J. Mat. Sci. Technol., 2020, 57,204–220. [CrossRef]

- G.-L. Song, A. Atrens, Recently deepened insights regarding Mg corrosion and advanced engineering applications of Mg alloys, J. Magnes. Alloys, 2023, 11, 3948–3991. [CrossRef]

- M. Esmaily, J.E. Svensson, S. Fajardo, N. Birbilis, G.S. Frankel, S. Virtanen, R. Arrabal, S. Thomas, L.G. Johansson, Fundamentals and advances in magnesium alloy corrosion, Prog. in Mater. Sci., V89 2017, V89, 92-1 93.

- H.Liu, F. Cao, G.-L. Song, D. Zheng, Z. Shi, M.S. Dargush and A. Atrens, Review of the atmospheric corrosion of magnesium alloys, J. Mat. Sci. Technol., 2019, 35, 2003–2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Luo, L. Liu, H. Wang, T. Liu, H. Li, B. Tan, Y. Pan, A Liu, J. Cheng, Research progress on the corrosion behavior of magnesium alloys in natural environments, Materials Today Communications 2025, 48, 113433. [CrossRef]

- M. Wang, L. Yang, H. Liu, X. Wang, Y. Li, and Y. Huang, Recent Progress on Atmospheric Corrosion of Field-Exposed Magnesium Alloys, Metals 2024,14, 1000. [CrossRef]

- R. Arrabal, A. Pardo, M. C. Merino, S. Merino, M. Mohedano and P. Casaju’s, Corrosion behaviour of Mg/Al alloys in high humidity atmospheres, Mater. Corros. 2011,62, 326-334. [CrossRef]

- M. Shahabi-Navid, Y. Cao, J. E. Svensson, A. Allanore, N. Birbilis, L. G. Johansson, M. Esmaily, On the early stages of localised atmospheric corrosion of magnesium–aluminium alloys, Sci. Rep. 2020 10, 10:20972. [CrossRef]

- S. Feliu Jr, A. Pardo, M.C. Merino, A.E. Coy, F. Viejo, R. Arrabal, Correlation between the surface chemistry and the atmospheric corrosion of AZ31, AZ80 and AZ91D magnesium alloys, Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 255, 4102–4108. [CrossRef]

- R. Lindstrom, L.-G. Johansson, G. E. Thompson, P. Skeldon, J.-E. Svensson, Corrosion of magnesium in humid air, Corros. Sci. 46 2004, 46 1141–1158. [CrossRef]

- M. C.Zhao, M. Liu, G. Song, A. Atrens, Influence of the β-phase morphology on the corrosion of the Mg alloy AZ91, Corrosion Science 50 (2008) 1939–1953.

- M. Jönsson and D. Persson, The influence of the microstructure on the atmospheric corrosion behaviour of magnesium alloys AZ91D and AM50, Corros. Sci. 52 (2010) 1077-1 085. [CrossRef]

- M. Esmaily, D.B. Blücher , J.E. Svensson, M. Halvarsson, L.G. Johansson, New insights into the corrosion of magnesium alloys — The role of aluminum, Scr. Mater, 115 2016, 115 91–95.

- M. Danaie, R. M. Asmussen, P. Jakupi, D. W. Shoesmith, G. A. Botton, The role of aluminum distribution on the local corrosion resistance of the microstructure in a sand-cast AM50 alloy, Corros. Sci. 2013 77 (151–163. [CrossRef]

- T. M. Schwarz, N. Birbilis, B. Gault, I McCarroll, Understanding the Al diffusion pathway during atmospheric corrosion of a Mg-Al alloy using atom probe tomography, Corros. Sci. 2025, 252, 112951. [CrossRef]

- D. Persson and C.Leygraf, In Situ Infrared Reflection Absorption Spectroscopy for Studies of Atmospheric Corrosion, J. Electrochem. Soc. 140 1993, 140, 1256. [CrossRef]

- D. Persson, D. Thierry, N. LeBozec, T. Prosek, In situ infrared reflection spectroscopy studies of the initial atmospheric corrosion of Zn–Al–Mg coated steel, Corros. Sci., 2013,72, 54-63.

- D. Persson, D. Thierry, N. LeBozec, The Effect of Microstructure on Local Corrosion Product Formation during Initial SO2-Induced Atmospheric Corrosion of ZnAlMg Coating Studied by FTIR-ATR FPA Chemical Imaging, Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2023, 4 503-515. [CrossRef]

- J. Mathurin, A. Deniset-Besseau, D. Bazin, E. Dartois, M. Wagner and A. Dazzi, Photothermal AFM-IR spectroscopy and imaging: Status, challenges, and trends, J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 131, 010901. [CrossRef]

- V.C. Farmer, ed., The Infrared spectra of minerals, Mineralogical society, London (1974).

- M. Jönsson, D. Persson, D.Thierry, Corrosion product formation during NaCl induced atmospheric corrosion of magnesium alloy AZ1D, Corr. Sci., 2007, 49,1540-1 558. [CrossRef]

- C. Fotea, J. Callaway and M.R. Alexander, Characterisation of the surface chemistry of magnesium exposed to the ambient atmosphere, Surf. Interface Anal. 2006, 38, 1363–1371.

- L. Harms, I. Brand, Application of PM IRRAS to study structural changes of the magnesium surface in corrosive environments, Vib. Spectrosc., 2018, 97 106–113. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Hofmeister, E. Keppel and A. K. Speck, Absorption and reflection infrared spectra of MgO and other diatomic compounds, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2003,345 16–38.

- B. Harbecke, B. Heinz, and P. Grosse, Optical Properties of Thin Films and the Berreman Effect, Appl. Phys. A 1985, 38, 263-267.

- S. A. Francis and A. H. Ellison, Infrared Spectra of Monolayers on Metal Mirrors, J. Opt. Soc. Am., 1959, 49, 131-1 38. [CrossRef]

- H.He, J. Cao, N. Duan, Defects and their behaviors in mineral dissolution under water environment: A review, Sci. Total Environ., 2019, 651 2208–2217.

- Kangli Wang and Beate Paulus, Cluster Formation Effect of Water on Pristine and Defective MoS2, Monolayers, Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 229. [CrossRef]

- M. Liu, S. Zanna, H. Ardelean, I. Frateur, P. Schmutz, G. Song, A. Atrens, P. Marcus, A first quantitative XPS study of the surface films formed, by exposure to water, on Mg and on the Mg–Al intermetallics: Al3Mg2 and Mg17Al12, Corros. Sci. 2009, 51 1115–1127.

- M. Jönsson, D.Thierry, N. Lebozec, The influence of microstructure on the corrosion behaviour of AZ91D studied by scanning Kelvin probe force microscopy and scanning Kelvin probe, Corr. Sci., 2006, 48 1193-1 208.

- M. Jönsson, D. Persson and R. Gubner, The Initial Steps of Atmospheric Corrosion on Magnesium Alloy AZ91D, J. Electrochem. Soc. 2007, 154, C684. [CrossRef]

- M. Altmaier,V. Metz, V. Neck, R. Müller, Fanghänel, Solid-liquid equilibria of Mg(OH)2(cr) and Mg2(OH)3Cl·4H2O(cr) in the system Mg-Na-H-OH-Cl-H2O at 25°C, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2003, 67, 3595-3601. [CrossRef]

- Q. Gautier, P. Benezeth, V. Mavromatis, J. Schott, Hydromagnesite solubility product and growth kinetics in aqueous solution from 25 to 75 ºC, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2014, 138, 1–20.

- M. Strebl and S. Virtanen, Real-Time Monitoring of Atmospheric Magnesium Alloy Corrosion, J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, C3001-C3009.

- M. Strebl, M. Bruns, and S. Virtanen, Editors’ Choice—Respirometric in Situ Methods for Real-Time Monitoring of Corrosion Rates: Part I. Atmospheric Corrosion, J. Electrochem. Soc., 2020, 167, 021510.

- E. Silva, S.V. Lamaka, D. Mei, M. Zheludkevich, The Reduction of Dissolved Oxygen During Magnesium Corrosion, ChemistryOpen 2018, 7, 664 – 668. [CrossRef]

- C.Wang, K. Q. Yulong Wu, D. Mei, C. Chu, F. Xue, J. Bai, M. L. Zheludkevich, S. V. Lamaka, Consistent high rate oxygen reduction reaction during corrosion of Mg-Ag Alloy, Corros. Sci., 2024, 229, 111893. [CrossRef]

| material | Al | Zn | Mn | Si | Cu | Fe | Ni |

| AZ 31 | 3.1 | 0.73 | 0.25 | 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.006 | <0.001 |

| AZ 91 | 8.8 | 0.68 | 0.3 | 0.001 | 0.0 | 0.004 | <0.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).