Submitted:

22 December 2025

Posted:

23 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Study Area

2.1. Geological Setting

2.2. Soils of the Petra Region

3. Materials and Methods

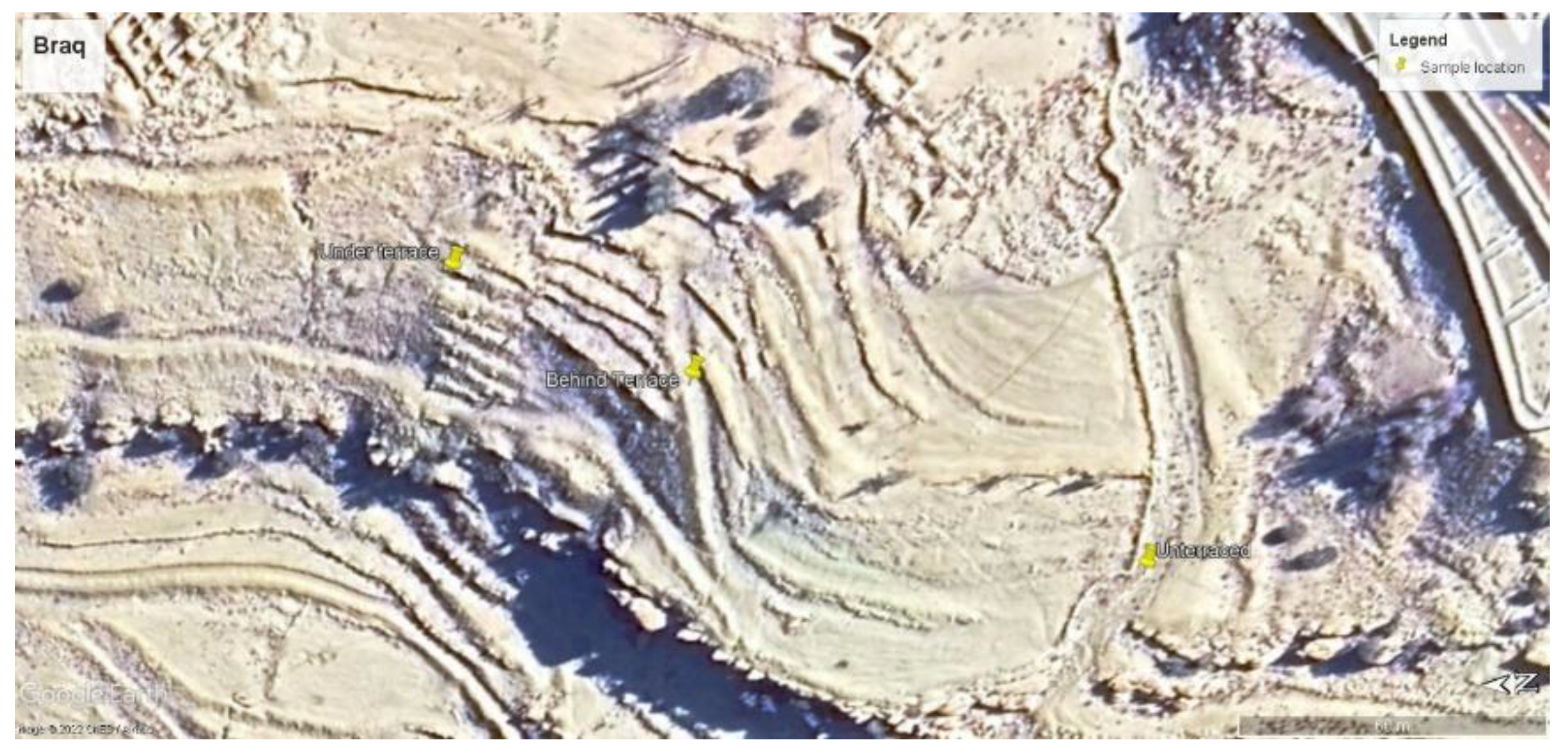

3.1. Study Sites

3.2. Soil Sampling Strategy

3.3. Soil Texture Analysis

3.3.1. Dry Sieving

3.3.2. Wet Sieving and Laser Diffraction

3.4. Aggregate (Ped) Stability Testing

3.5. Soil Chemical Analyses

3.5.1. Nutrients (N, P, K)

3.5.2. Soil pH and Salinity

4. Results

4.1. Soil Texture

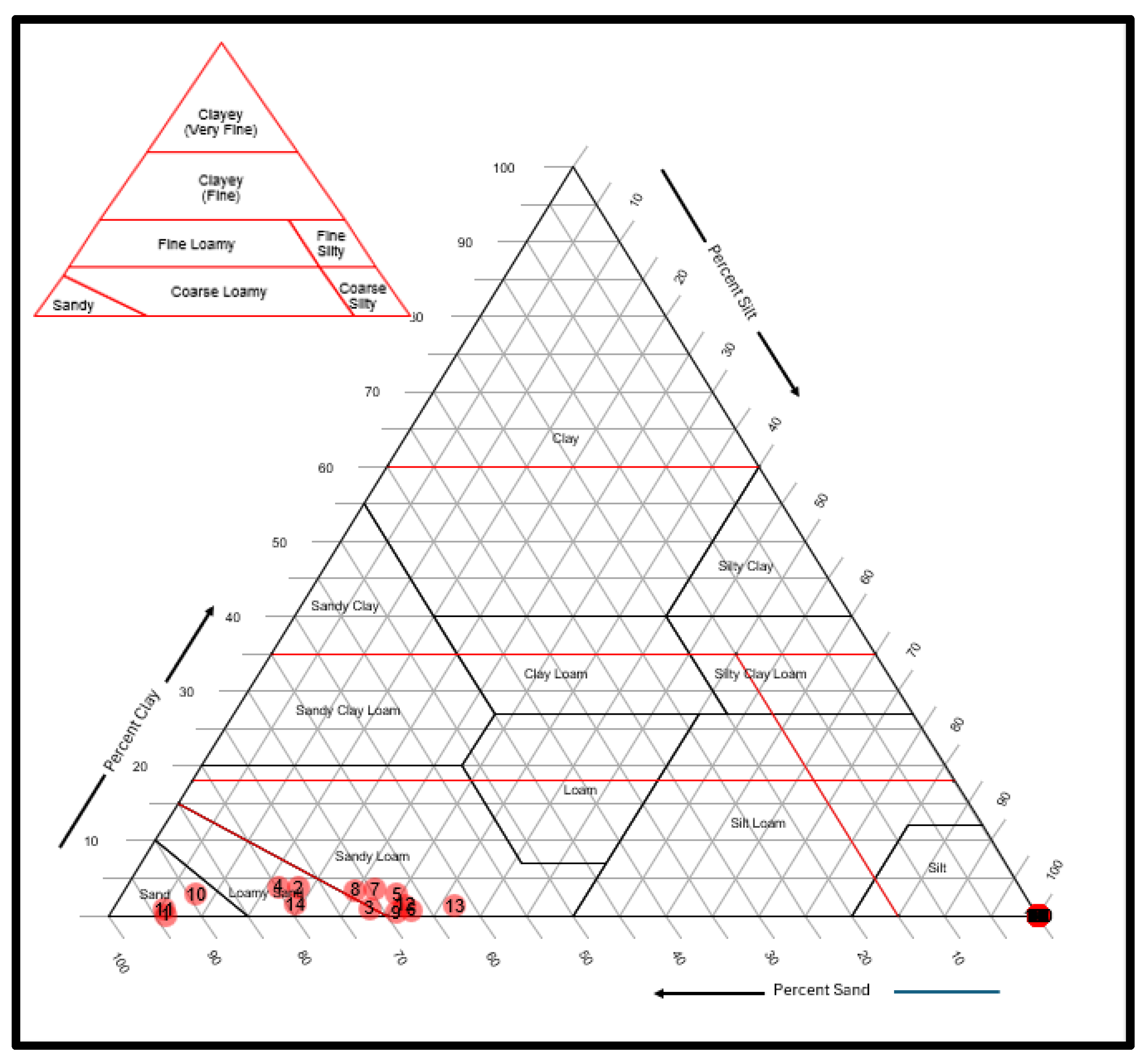

4.1.1. Dry Sieving Results

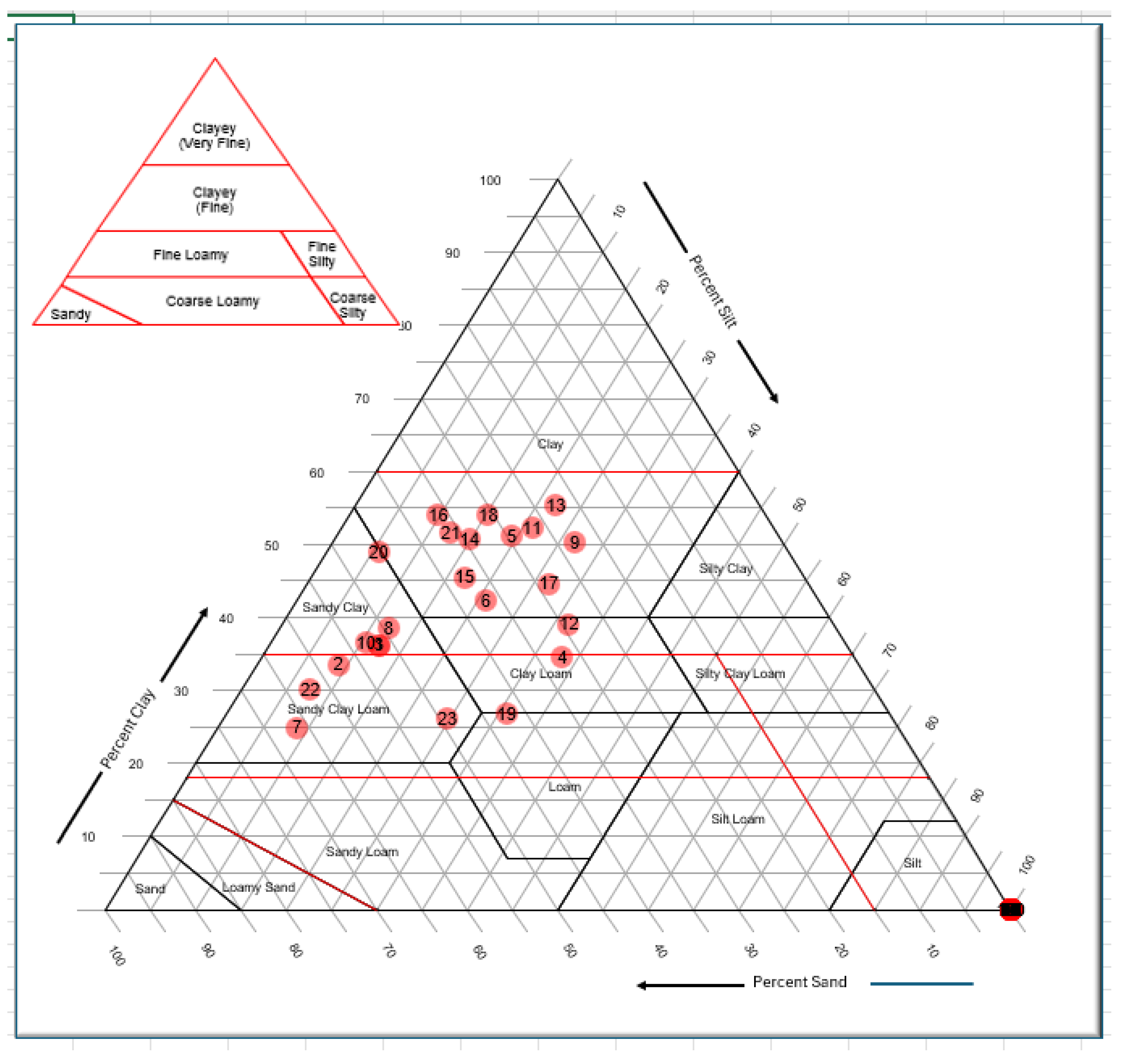

4.1.2. Wet Sieving Results

4.2. Comparison between Dry and Wet Sieving

4.3. Ped Stability

4.4. Soil Chemistry

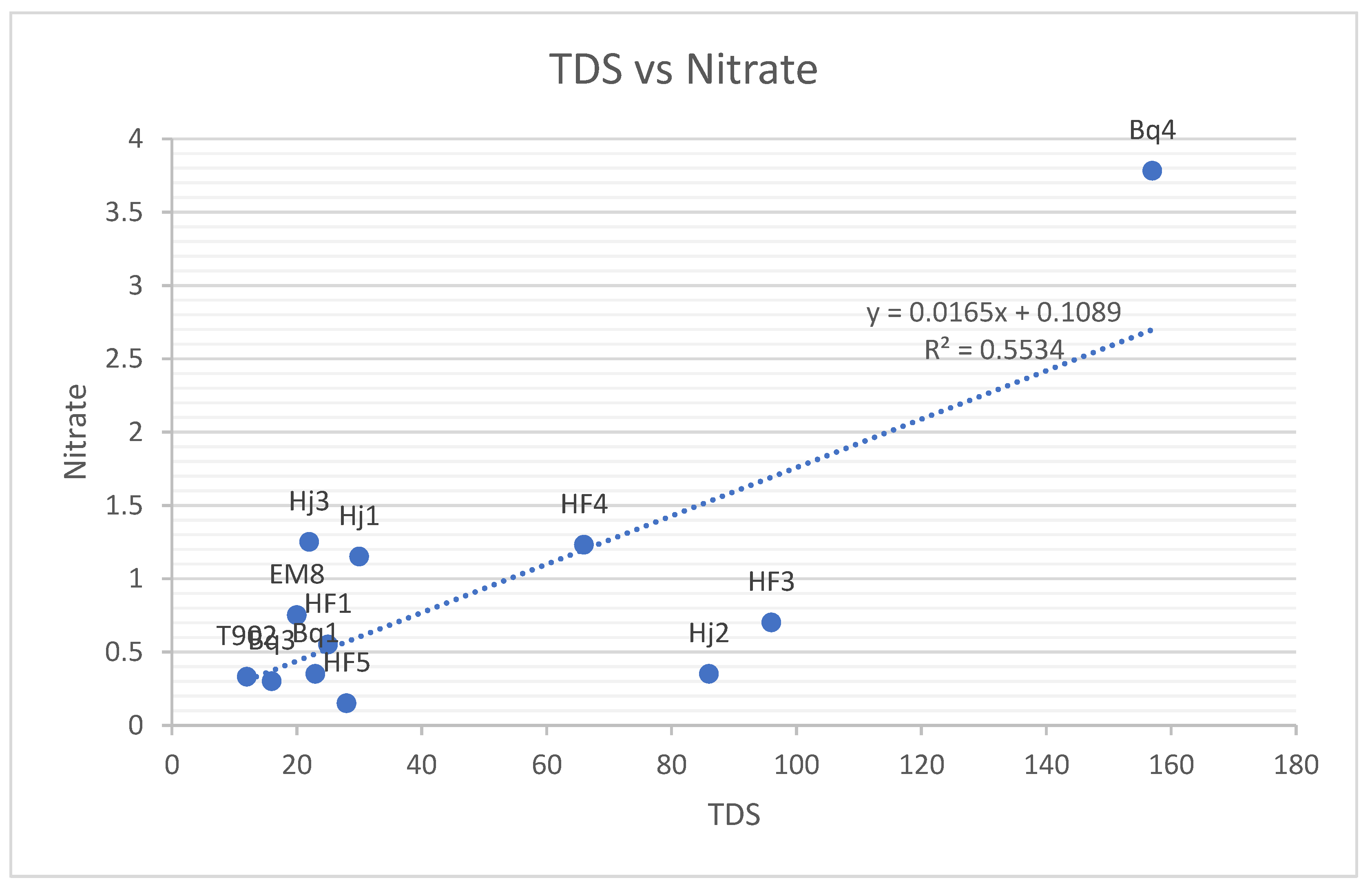

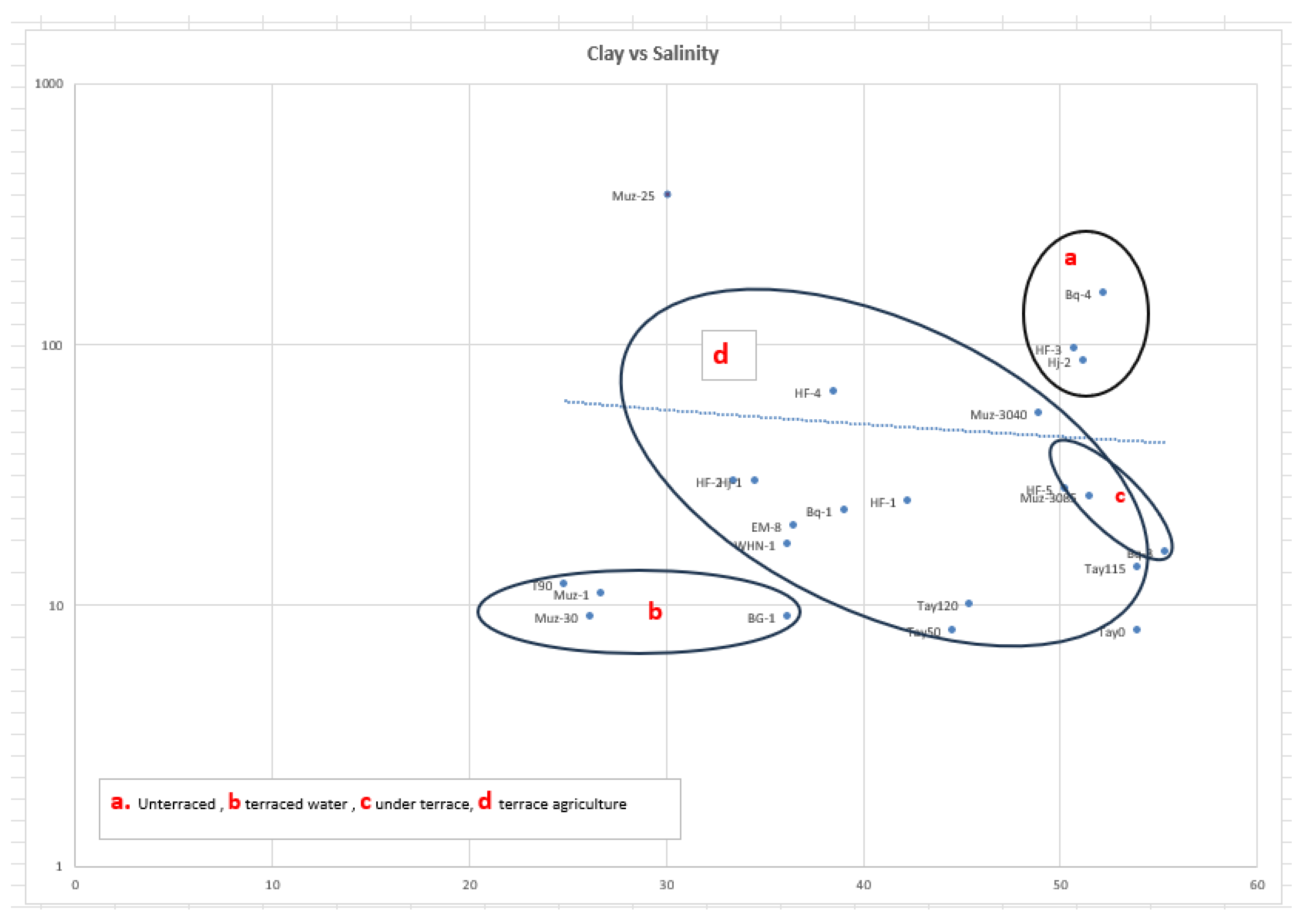

4.5. Soil Salinity

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdelal, Q.; Al-Rawabdeh, A.; Al Qudah, K.; Hamarneh, C.; Abu-Jaber, N. Hydrological assessment and management implications for the ancient Nabataean flood control system in Petra, Jordan. J. Hydrol. 2021, 601, 126583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Ajamieh, M.M.; Bender, F.K.; Eicher, R.N. Natural Resources in Jordan, Inventory, Evaluation, Development Program; Natural Resources Authority: Amman, Jordan, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Jaber, N.; Al Khasawneh, S.; Alqudah, M.; Hamarneh, C.; Al-Rawabdeh, A.; Murray, A. Lake Elji and a geological perspective on the evolution of Petra, Jordan. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2020, 557, 109904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Jaber, N.; Rambeau, C.; Hamarneh, C.; Lucke, B.; Inglis, R.; Alqudah, M. Development, distribution and palaeoenvironmental significance of terrestrial carbonates in the Petra region, southern Jordan. Quatern. Int. 2020, 545, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Jaber, N.; Hamarneh, C.; AlFarajat, M.; Al-Rawabdeh, A.; Al Khasawneh, S. Historic management of the dynamic landscape in the surroundings of Petra, Jordan. Jordan J. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 13, 232–241. [Google Scholar]

- Akasheh, T.S. Ancient and modern watershed management in Petra. Near East. Archaeol. 2002, 65, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Khasawneh, S.; Abu-Jaber, N.; Hamarneh, C.; Murray, A. Age determination of runoff terrace systems in Petra, Jordan, using rock surface luminescence dating. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2022, 14, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qudah, K.; Abdelal, Q.; Hamarneh, C.; Abu-Jaber, N. Taming the torrents: The hydrologic impacts of ancient terracing practices in Jordan. J. Hydrol. 2016, 542, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qudah, B. Soils of Jordan. In Soil Resources of Southern and Eastern Mediterranean Countries; Zdruli, P., Steduto, P., Lacirignola, C., Montanarella, L., Eds.; CIHEAM: Bari, Italy, 2001; Volume B, Études et Recherches, No. 34; pp. 127–141. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shabatat, A. Environmental Deterioration and Land Management in the Petra-Showbak Area, Jordan. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Arya, L.M.; Leij, F.J.; Shouse, P.J.; van Genuchten, M.T. Relationship between the hydraulic conductivity function and the particle-size distribution. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1999, 63, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barjous, M.O. The Geology of Petra and Wadi Al Lahyana Area: Map Sheets No. 3050-I and 3050-IV; Natural Resources Authority: Amman, Jordan, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Barjous, M.; Mikbel, S. Tectonic evolution of the Gulf of Aqaba-Dead Sea transform. Tectonophysics 1990, 180, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, B.; Schütt, B.; Tsukamoto, S.; Frechen, M. Age determination of Petra’s engineered landscape–optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) and radiocarbon ages of runoff terrace systems in the Eastern Highlands of Jordan. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2013, 40, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, N.C.; Weil, R.R. The Nature and Properties of Soils, 15th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brandão, A.R.A.; Schwamback, D.; Ballarin, A.S.; Ramirez-Avila, J.J.; Neto, J.G.V.; Oliveira, P.T.S. Toward a better understanding of curve number and initial abstraction ratio values from a large sample of watersheds perspective. J. Hydrol. 2025, 655, 132941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapuis, R.P. Predicting the saturated hydraulic conductivity of soils: A review. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2012, 71, 401–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronshey, R. Urban Hydrology for Small Watersheds; US Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service, Engineering Division: Washington, DC, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Hamarneh, C. Investigating Ancient Man-Made Terraces of Petra–Jordan. Ph.D. Dissertation, Kultur-, Sozial-und Bildungswissenschaftliche Fakultät, Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazen, A. Some Physical Properties of Sand and Gravel, with Special Reference to Their Use in Filtration; 24th Annual Report; Massachusetts State Board of Health: Boston, MA, USA, 1892; pp. 539–556. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.; Chen, C.; Chen, S.; Ling, H.; Mei, S.; Tang, Y. Permeability estimation of engineering-adapted clay–gravel mixture based on binary granular fabric. Water 2024, 16, 2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, S. Phosphorus. In Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 3. Chemical Methods; Sparks, D.L., Page, A.L., Helmke, P.A., Loeppert, R.H., Eds.; Soil Science Society of America, American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; pp. 869–920. [Google Scholar]

- Lucke, B.; Sandler, A.; Vanselow, K.A.; Bruins, H.J.; Abu-Jaber, N.; Bäumler, R.; Porat, N.; Kouki, P. Composition of modern dust and Holocene aeolian sediments in archaeological structures of the Southern Levant. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucke, B.; Roskin, J.; Vanselow, K.A.; Bruins, H.J.; Abu-Jaber, N.; Deckers, K.; Lindauer, S.; Porat, N.; Reimer, P.J.; Bäumler, R.; et al. Character, rates, and environmental significance of Holocene dust accumulation in archaeological hilltop ruins in the southern Levant. Geosciences 2019, 9, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouki, P. The Hinterland of a City: Rural Settlement and Land Use in the Petra Region from the Nabataean-Roman to the Early Islamic Period. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Odeh, I.; Brent, C.S.; Al-Khasawneh, A.S.; van der Sluijs, G.T.J. Soil and sediment dynamics in semi-arid landscapes of Jordan. Geoarchaeology 2015, 30, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, P.; Lopez-Sanchez, J.F.; Rauret, G. Relationships between phosphorus fractionation and major components in sediments using the SMT harmonised extraction procedure. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2003, 376, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlotto, C.; D’Agostino, V. Performance assessment of bench terraces through 2D modelling. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, J.H.; Moh’d, B.K. Evolution of Cretaceous to Eocene alluvial and carbonate platform sequences in central and south Jordan. GeoArabia 2011, 16, 29–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pla, I.; Nacci, S. Traditional compared to new systems for land management in vineyards of Catalonia (Spain). In Techniques Traditionnelles de GCES en Milieu Méditerranéen;Bulletin Réseau Erosion; Roose, E., Ed.; IRD: Marseille, France; ENFI: Salé, Morocco, 2003; Volume 21, pp. 213–223. [Google Scholar]

- Puchades, R.; Llopis, A.; Raigón, M.D.; Peris-Tortajada, M.; Maquieira, A. A simplified method for the extraction and analysis of available nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium in soils. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 1994, 25, 2543–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qashou, M.; AlQura’an, S. Design of Flood Control System in Petra, Jordan, Using Ancient Technologies. Bachelor’s Thesis, Department of Water and Environmental Engineering, German Jordanian University, Amman, Jordan, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, M.C.; Cots-Folch, R.; Martínez-Casasnovas, J.A. Sustainability of modern land terracing for vineyard plantation in a Mediterranean mountain environment–the case of the Priorat region (NE Spain). Geomorphology 2007, 86, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, K.S.; Singh, S.K. Estimation of surface runoff from semi-arid ungauged agricultural watershed using SCS-CN method and earth observation data sets. Water Conserv. Sci. Eng. 2017, 1, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.W.; Santamarina, J.C. The hydraulic conductivity of sediments: A pore size perspective. Eng. Geol. 2018, 233, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, J.; Duarte, A.; Fabres, S.; Quintela, A.; Serpa, D. Influence of DEM resolution on the hydrological responses of a terraced catchment: An exploratory modelling approach. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, F.; Newman, S.; Nicosia, C.; Plekhov, D. Assembling Petra’s rural landscapes. Antiquity 2020, 94, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, A.M. Geoarchaeology in semi-arid environments: Terrace and wadi sediment studies. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2012, 39, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, R.G. Correlations of permeability and grain size. Ground Water 1989, 27, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Soil Survey Staff. Soil Taxonomy: A Basic System of Soil Classification for Making and Interpreting Soil Surveys, 2nd ed.; USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Viets, F.G., Jr. Animal wastes and fertilizers as potential sources of nitrate pollution of water. In Effects of Agricultural Production on Nitrates in Food and Water with Particular Reference to Isotope Studies; Proc. panel of experts organized by joint FAO/IAEA Div. Atomic Energy in Food and Agriculture: Vienna, Austria, 1974; pp. 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wuenscher, R.; Unterfrauner, H.; Peticzka, R.; Zehetner, F. A comparison of 14 soil phosphorus extraction methods applied to 50 agricultural soils from Central Europe. Plant Soil Environ. 2015, 61, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample ID | Sample description | Elevation | Coordinates | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Easting (m E) | Northing (m N) | |||

| T90 | Hremiyyeh behind terrace | 1100 | 736335.00 | 3355685.00 |

| HF1 | Muderej farm Unterraced | 1576 | 741296.87 | 3362940.35 |

| HF2 | Muderej Farm wall outside | 1576 | 741277.63 | 3362929.34 |

| HF3 | Muderej Unterraced | 1584 | 741296.87 | 3362940.35 |

| HF4 | Muderej Behind the terrace C | 1575 | 741304.61 | 3362916.46 |

| HF5 | Muderej Under the terrace B wall. | 1576 | 741292.97 | 3362873.38 |

| EM8 | Beidha Behind the terrace | 1022 | 736261.00 | 3359814.00 |

| Hj1 | Hujaim Behind the terrace | 1351 | 739186.98 | 3353882.08 |

| Hj2 | Hujaim Unterraced flood plain | 1349 | 739204.29 | 3353887.00 |

| Bq1 | Braq Behind terrace wall | 1288 | 736829.09 | 3355500.18 |

| Bq3 | Braq under terrace wall | 1286 | 736850.00 | 3355545.00 |

| Bq4 | Braq Unterraced | 1283 | 736792.82 | 3355414.99 |

| WHN-1 | Muderej terrace near the highway | 1587 | 741393.63 | 3362659.59 |

| BG-1 | Beqa’a behind terrace | 1406 | 739908.49 | 3356242.48 |

| Tay0 | Taybeh Surface | 1361 | 737020.23 | 3349107.16 |

| Tay-120 | Taybeh behind terrace 2 at depth 120cm | 1350 | 736868.00 | 3349005.00 |

| y-50 | Taybeh behind terrace 1 depth 50cm | 1347 | 736878.00 | 3349010.00 |

| Tay-115 | Taybeh behind terrace 1 depth 115cm | 1347 | 736878.00 | 3349010.00 |

| Muz-1 | Muzera’a behind First low terrace W of the Wadi | 1158 | 738379.00 | 3358437.00 |

| Muz-3040 | Muzera’a behind central segment terrace N. 30 at depth 40 cm | 1190 | 738550.00 | 3358701.00 |

| Muz-3085 | Muzera’a behind central segment terrace N. 30 at depth 85 cm | 1190 | 738550.00 | 3358701.00 |

| Muz-25 | Muzera’a central segment terrace N. 25 under terrace | 1187 | 738554.00 | 3358695.00 |

| Muz-30 | Behind central segment terrace N. 30 at the surface | 1190 | 738550.00 | 3358701.00 |

| Sample ID | Sample location | Gravel (%) | Sand (%) | Fine (%) | Silt (%) | Clay (%) | Texture (Dry) | Sand (%) | Silt (%) | Clay (%) | Texture (Wet) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHN-1 | Wall near highway | 6 | 93.9 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.08 | Sand | 51.71 | 12.09 | 36.20 | Clay |

| HF-2 | Farm N wall outside | 17.2 | 77.8 | 4.7 | 0.99 | 3.71 | Loamy sand | 57.55 | 8.95 | 33.50 | Sandy clay loam |

| BG-1 | Beqa’a | 27.1 | 71.5 | 1.4 | 0.39 | 1.01 | Loamy sand | 51.71 | 12.09 | 36.20 | Sandy clay |

| Hj-1 | Hujaim village, top horizon | 10.9 | 79.9 | 7.5 | 3.67 | 3.83 | Loamy sand | 32.29 | 33.19 | 34.52 | Clay loam |

| Hj-2 | Hujaim village, floodplain | 27.8 | 67.6 | 3.8 | 0.99 | 2.81 | Sandy loam | 29.51 | 19.28 | 51.21 | Clay |

| HF-1 | South side wadi upstream | 31.3 | 67.1 | 1.1 | 0.36 | 0.74 | Sandy loam | 36.83 | 20.83 | 42.34 | Clay |

| T90 | Hremiyyeh | 22.2 | 69.6 | 4.8 | 1.25 | 3.55 | Sandy loam | 66.42 | 8.71 | 24.87 | Sandy clay loam |

| EM-8 | Beidha | 6.1 | 89.2 | 3.7 | 0.83 | 2.87 | Sand | 53.01 | 10.50 | 36.49 | Sandy clay |

| Sample | H2O (mL g−1) | HCl (mL g−1) |

|---|---|---|

| Taybeh | 1.02 | 0.63 |

| Muz-1 | 1.83 | 0.73 |

| Hj-1 | 0.98 | 1.03 |

| HF-5 | 2.13 | 1.42 |

| EM-8 | 2.8 | 3.6 |

| BG-1 | 2.4 | 2.0 |

| Braq | 5.0 | 4.5 |

| T90 | ND a | ND a |

| Sample ID | NO3–N (mg g−1 soil) | Total P (mg g−1) | Inorganic P (mg g−1) | Organic P (mg g−1)a | pH | K (mg g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T90 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.055 | 0.315 | 9.92 | 2.05 |

| HF1 | 0.55 | 0.25 | 0.095 | 0.155 | 10.28 | 1.10 |

| HF3 | 0.70 | 0.17 | 0.075 | 0.095 | 10.22 | 0.85 |

| HF4 | 1.23 | 0.125 | 0.060 | 0.065 | 8.66 | 1.50 |

| HF5 | 0.15 | 0.195 | 0.075 | 0.120 | 9.91 | 1.10 |

| Hj1 | 1.15 | 0.145 | 0.115 | 0.030 | 8.72 | 3.90 |

| Hj2 | 0.35 | 0.095 | 0.095 | 0.000 | 8.66 | 1.60 |

| Hj3 | 1.25 | 0.165 | 0.075 | 0.090 | 9.02 | 0.80 |

| Bq1 | 0.30 | 0.140 | 0.085 | 0.055 | 10.28 | 3.45 |

| Bq3 | 0.35 | 0.070 | 0.040 | 0.030 | 10.29 | 3.05 |

| Bq4 | 3.78 | 0.080 | 0.035 | 0.045 | 10.20 | 2.10 |

| EM-8 | 0.75 | 0.120 | 0.050 | 0.070 | 10.13 | 1.40 |

| Sample ID | Sample location | TDS (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|

| T90 | Hremiyyeh behind terrace | 12 |

| HF1 | S side wadi upstream near al-Muderej | 25 |

| HF3 | N. side of wadi upstream al-Muderej | 96 |

| HF4 | al-Muderej behind terrace C | 66 |

| HF5 | Under terrace B al-Muderej Farm | 28 |

| Hj1 | Hujaim Village behind terrace | 30 |

| Hj2 | Hujaim Village floodplain horizon | 86 |

| Hj3 | Hujaim under terrace wall | 22 |

| Bq3 | Soil under Braq terrace | 16 |

| Bq1 | Braq behind terrace wall | 23 |

| Bq4 | Braq unterraced | 157 |

| EM8 | Beidha | 20 |

| WNH-1 | Terrace near highway | 17 |

| BG-1 | Beqa’a | 9 |

| Muz30 | Muzera’a near surface | 9 |

| Muz3040 | Muzera’a terrace 30 depth 40 | 54 |

| Muz3085 | Muzera’a terrace 30 depth 85 | 26 |

| Muz 25 | Behind the wall | 376 |

| Muz 1 | Muzera’a behind First low terrace W of the Wadi | 11 |

| Tay115 | Taybeh depth 115 | 14 |

| TayS0 | Taybeh Surface | 8 |

| Tay120 | Taybeh depth 120 | 10 |

| Tay50 | Taybeh depth 50 | 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).