1. Introduction

Climate change poses a significant global challenge affecting both individuals with pre-existing mental health issues and those without [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Rising temperatures, extreme weather events such as heat waves, floods, tornadoes, hurricanes, droughts, wildfires, and the degradation of forests can lead to various physical and psychological effects [

2,

5]. However, research regarding the psychiatric effects of climate change in Uganda remains limited. Mental health is a crucial component of overall well-being, encompassing an individual's capacity to realize their potential, cope with stressors, work productively, and contribute to their community [

6].

A mental health disorder (MHD) is characterised by a clinically significant disruptions in cognition, emotional regulation, or behaviour, often resulting in distress or functional impairment. These include a range of conditions such as depression, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), bipolar disorder, eating disorders, neurodevelopmental disorders, and substance abuse disorders [

7].

Climate sensitive events, including rising temperatures, frequent and intense heat waves, extreme precipitation with attendant flooding, prolonged droughts, and deteriorating air quality, are increasingly recognised as major contributors to both physical and mental health challenges [

1,

2,

4,

5]. These environmental stressors operate through various mechanisms; acute events such as floods may lead to PTSD, depression and anxiety through direct psychological trauma and displacement [

1]. Chronic exposures such as sustained heat, high humidity and degraded air quality operate through physiological stress due to sleep disruption, thermoregulatory strain, systemic inflammation and socio-economic stressors stemming from loss of income and food insecurity which elevate the risk of mood, anxiety and substance use disorders [

8,

9,

10].

Countries in Sub Saharan Africa (SSA) are particularly susceptible to the effects of climate change due to limited adaptive capacity, widespread poverty, governance challenges, and dependence on climate-sensitive livelihoods [

11,

12]. The burden due to climate change is estimated to be 34% of the disability-adjusted life years in SSA [

13]. Urban centres, however, face unique and escalating vulnerabilities related to climate change. Rapid, often unplanned urbanisation concentrates populations in flood prone informal settlements, intensifies the urban heat island effect, strains water and sanitation systems, and amplifies exposure to air pollution; all of which are linked to adverse mental health outcomes [

3,

11,

14].

Kampala, Uganda’s political and economic hub exemplifies these urban vulnerabilities. In the past two decades, the city has experienced an average surface temperature increase of about 1 °C, alongside more frequent intense rainfall events leading to flash floods, and episodic prolonged dry spells [

15,

16]. Factors driving climate change in Kampala include rapid industrialization, encroachment on wetlands, increased vehicle emissions, and significant population growth, with a daytime population of about two million [

14,

17] Flooding in informal settlements like Bwaise, Katanga damage infrastructure, disrupt livelihoods and contaminate water sources, precipitating acute stress reactions, depression and anxiety.

Despite the global increase in research on the intersection of climate change and mental health, few studies have specifically focused on urban settings in SSA, including Kampala. Residents of Kampala encounter numerous stressors, such as substandard housing, food insecurity, environmental risks, high unemployment rates, and restricted access to mental health services. These interconnected factors elevate the likelihood of mental distress and psychiatric disorders. This study, therefore, investigated the relationship between mental disorders and climate factors among residents of Kampala district receiving care at BNRMH from 2019 to 2023. Understanding the specific vulnerabilities of urban environments is crucial for developing effective, context-sensitive mental health interventions and policies in a rapidly urbanizing and climate-affected context.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Area

This study used ecological and cross-sectional designs that employed quantitative data collection methods. Data on mental disorders and climate factors were obtained from Butabika National Referral Mental Hospital [

18] and Uganda National Meteorological Authority [

19] respectively. Established in 1955 and located approximately 12 kilometers east of Kampala, BNRMH serves as Uganda’s national mental referral, teaching, and research facility, with a bed capacity of 550 but often housing between 850 and 1000 patients [

18]. UNMA is a semi-autonomous government institution under the Ministry of Water and Environment. It has a mandate to promote and monitor weather and climate as well as provide weather forecasts and advisories to Government and other stakeholders for use in sustainable development [

19].

2.2. Data Source

BNRMH consists of the outpatient and inpatient departments. All cases that come to the facility are first seen at the outpatient department, where each patient is recorded in the Butabika Hospital outpatient medical register and assigned a unique patient number. Clinicians then assess each patient to determine whether they can be treated as outpatients or require inpatient care; those who are stable are managed as outpatients, while those who are unstable are admitted to the different wards in the hospital. The outpatient registers document the patient's number, name, age, sex, and residence. Diagnoses of mental disorders were extracted from patient files that were retrieved from the hospital data registry.

2.3. Study Participants, and Sampling Techniques

The study participants included all patient records of individuals aged 5-64 years from Kampala district who sought treatment at BNRMH between 2019 and 2023 for mental disorders such as anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, schizophrenia, and bipolar-related disorders. The study involved this age group because the impact of climate change on mental health affects all age groups, including children, adolescents, adults, and older people. Additionally, this age group is both susceptible and drastically impacted by mental disorders.

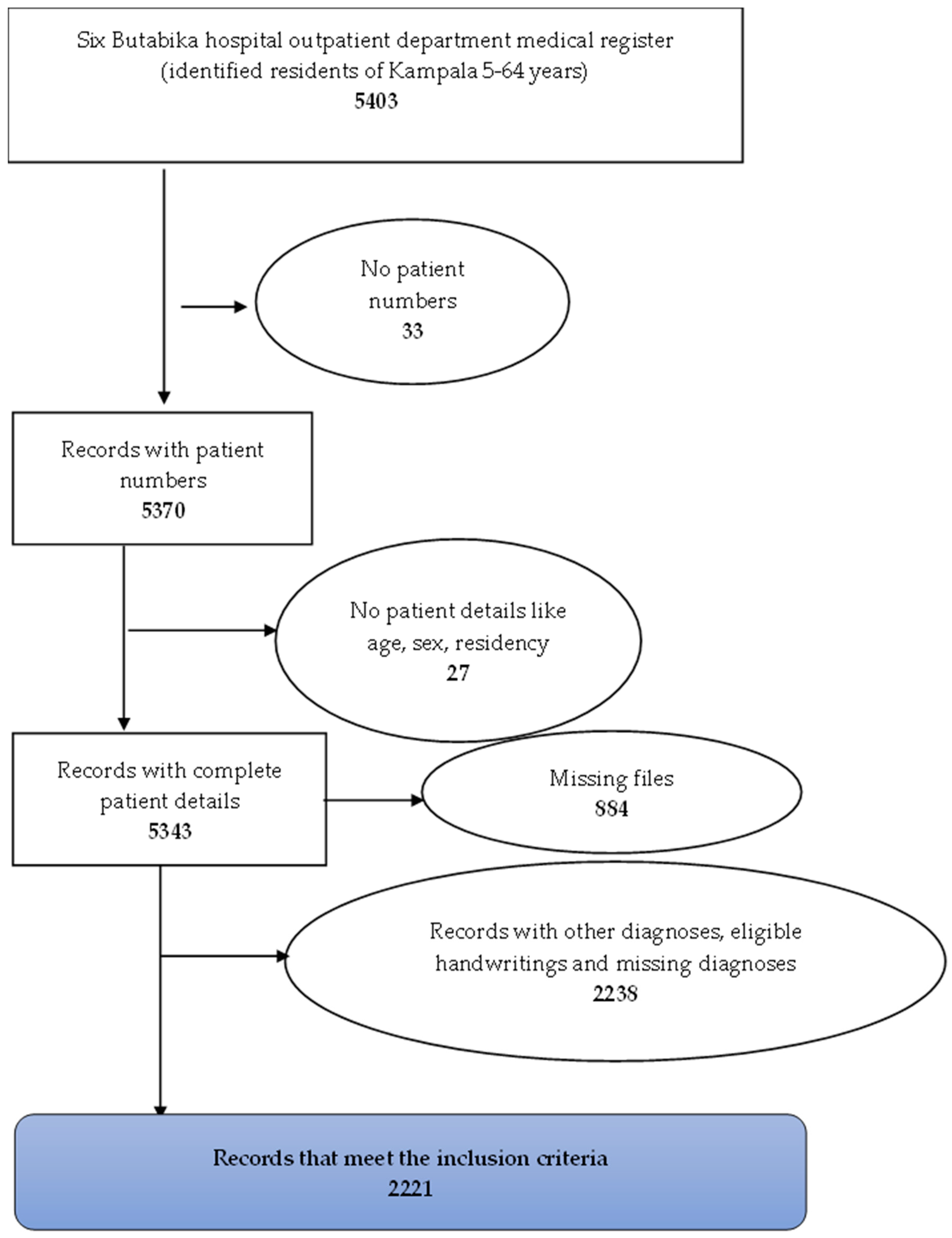

Data was gathered from six outpatient registers from BNRMH covering the years 2019 to 2023. With the assistance of six research assistants (RAs), 5403 records were identified for residents aged 5 to 64 years from Kampala district. Of these, 33 records were excluded due to the absence of patient numbers, preventing the retrieval of corresponding patient files for diagnosis. Therefore, 5370 records with patient numbers were retained, and of these, 27 did not have patient details such as age, sex, and residence. Efforts were made to recover the files of 5343 records with complete details from the data registry. Of these, 884 patient files were missing and 2238 files had illegible hand writings or did not have the diagnoses of interest. Ultimately, 2221 records over the 5-year period were used for this study. Error! Reference source not found.

2.4. Data Collection and Data Quality

Data collection took place between July and August 2024. Data was collected from the retrospective outpatient medical registers, and patient files using semi-structured questionnaires that captured patient diagnoses, age, sex and residency from 2019 to 2023. Six trained RAs utilized the Kobo Collect mobile data collection tool for these tasks. A separate tool was used to extract the climate data, including monthly rainfall in millimetres (mm), humidity in percentage (%), and ambient temperature (0C) for the reference period, sourced from UNMA. The climate data was availed at a fee. Mental health data missing key variables in the patient register, such as a diagnosis, age, sex and residency, and missing files were eliminated from data extraction; only data that was complete in the register was extracted. Additionally, before analysis, we checked for missing values and the completeness of the data. All the questionnaires were developed in English, and data collection was supervised by the principal investigator.

2.5. Study Variables

The primary outcome variable was a mental health disorder, divided into four categories according to DSM-V classification: 1) Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders 2) Bipolar related disorders 3) Depressive disorders 4) anxiety disorders [

20]. The diagnoses were obtained from individual patient files that were retrieved from the hospital data registry. Independent variables included: age measured as a continuous variable, Sex as a categorical variable in the categories of “Male” and “Female”, residency as a categorical variable, mean monthly temperature in (

0C), rainfall and millimetres (mm) and mean monthly Humidity was in percentage (%), all measured as continuous variables.

2.6. Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses utilising frequencies and percentages were used for categorical variables. Mean (standard deviation) or median (Inter-Quartile range/IQR) were used as descriptive statistics for numerical variables. Tables and graphs such as scatter plots were constructed to visually present the data. Correlation analysis was done by Spearman correlation since there was no linear relationship between the dependent and explanatory variables. Spearman coefficients, (rho) and P- values were obtained. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analysis was done using STATA version 14.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and Microsoft Excel 2019.

Time series analysis was conducted to identify trends and patterns in the cases of mental health disorders from 2019 to 2023. The analysis initially involved descriptive analysis, which consisted of constructing scatter plots of the raw data and exploring the dataset to identify any missing data; however, there was no missing data for the variables to be included in the times series model. The time series analysis was conducted using Poisson time series model since the outcome variable was a count; that is, the number of mental disorders recorded per month [

21]. Anxiety disorders were excluded from the statistical analysis as most months reported less than 5 cases.

3. Results

A total of 2221 participants was obtained.

Figure 1 The mean age of respondents was 31(±10) years. Half of the participants, 50.0% (1,111/2221) were males. Majority of the participants, 27.7% (616/2221) were from Nakawa division. Error! Reference source not found.

Table 1.

Background characteristics of participants.

Table 1.

Background characteristics of participants.

| Variable |

Frequency, N = 2221 |

Proportion (%) |

| Age (years) |

|

|

| Mean (standard deviation) |

31(±10) |

|

| 11-20 |

318 |

14.3 |

| 21-30 |

976 |

43.9 |

| 31-40 |

576 |

25.9 |

| 41-50 |

226 |

10.2 |

| 51-60 |

106 |

4.8 |

| 61-70 |

19 |

0.9 |

| Sex |

|

|

| Male |

1,111 |

50.0 |

| Female |

1,110 |

50.0 |

| Residence |

|

|

| Central division |

78 |

3.5 |

| Kawempe division |

466 |

21.0 |

| Makindye division |

572 |

25.8 |

| Nakawa division |

616 |

27.7 |

| Rubaga division |

489 |

22.0 |

Nearly half of the participants, 47.3% (1054/2228) were diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders, and of these 44.4% (468/1045) had Schizophrenia. Less than half of the participants, 25.6% (570/2228), were diagnosed with bipolar-related disorders, and of these, the majority, 93.7% (534/570) had Bipolar I disorder. Error! Reference source not found.

Table 2.

Proportion of mental health disorders among residents of Kampala district between 2019-2023.

Table 2.

Proportion of mental health disorders among residents of Kampala district between 2019-2023.

| Mental disorders |

Frequency, N = 2228 |

Proportion (%) |

| Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders |

1,054 |

47.3 |

| Schizotypal disorder |

7 |

|

| Delusional disorder |

16 |

|

| Brief psychotic disorder |

238 |

|

| Schizophreniform disorder |

254 |

|

| Schizophrenia |

468 |

|

| Schizoaffective disorder |

70 |

|

| Bipolar related disorder |

570 |

25.6 |

| Bipolar I disorder |

534 |

|

| Bipolar II disorder |

36 |

|

| Depressive disorders |

526 |

23.6 |

| Major depressive disorders |

374 |

|

| Dysthymia |

13 |

|

| Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder |

139 |

|

| Anxiety disorders |

78 |

3.5 |

| Generalized Anxiety disorders |

71 |

|

| Panic disorders | |

3 |

|

| Panic attack specific |

4 |

|

The year, 2019 was the hottest with an annual anchor temperature of 23.1 0C, the year 2020 was the most humid with a mean relative humidity of 79.2%, and the year 2023 was the wettest, with an annual rainfall average of 170.3mm. Error! Reference source not found.

Table 3.

Climate factors in Kampala district between 2019 to 2023.

Table 3.

Climate factors in Kampala district between 2019 to 2023.

| Environmental Variables |

Year |

Minimum |

Median |

Mean |

Maximum |

| Monthly mean Temperature (0C) |

2019 |

22.2 |

22.9 |

23.1 |

24.3 |

| 2020 |

21.8 |

22.9 |

22.8 |

23.3 |

| 2021 |

22.3 |

23.1 |

23.0 |

23.7 |

| 2022 |

22.3 |

22.5 |

22.8 |

23.6 |

| 2023 |

21.5 |

22.2 |

22.3 |

23.5 |

| Monthly mean relative humidity (%) |

2019 |

67.4 |

80.3 |

78.2 |

84.3 |

| 2020 |

73.9 |

79.6 |

79.2 |

81.1 |

| 2021 |

70.5 |

74.4 |

74.9 |

80.2 |

| 2022 |

68.2 |

73.1 |

73.4 |

78.8 |

| 2023 |

59.4 |

69.3 |

68.6 |

77.5 |

| Monthly mean rainfall (mm) |

2019 |

42.2 |

121.1 |

141.1 |

248.9 |

| 2020 |

33.7 |

158.2 |

165.3 |

282.9 |

| 2021 |

59.0 |

164.7 |

146.8 |

225.3 |

| 2022 |

23.0 |

163.1 |

147.7 |

223.1 |

| 2023 |

22.8 |

197.8 |

170.3 |

299.3 |

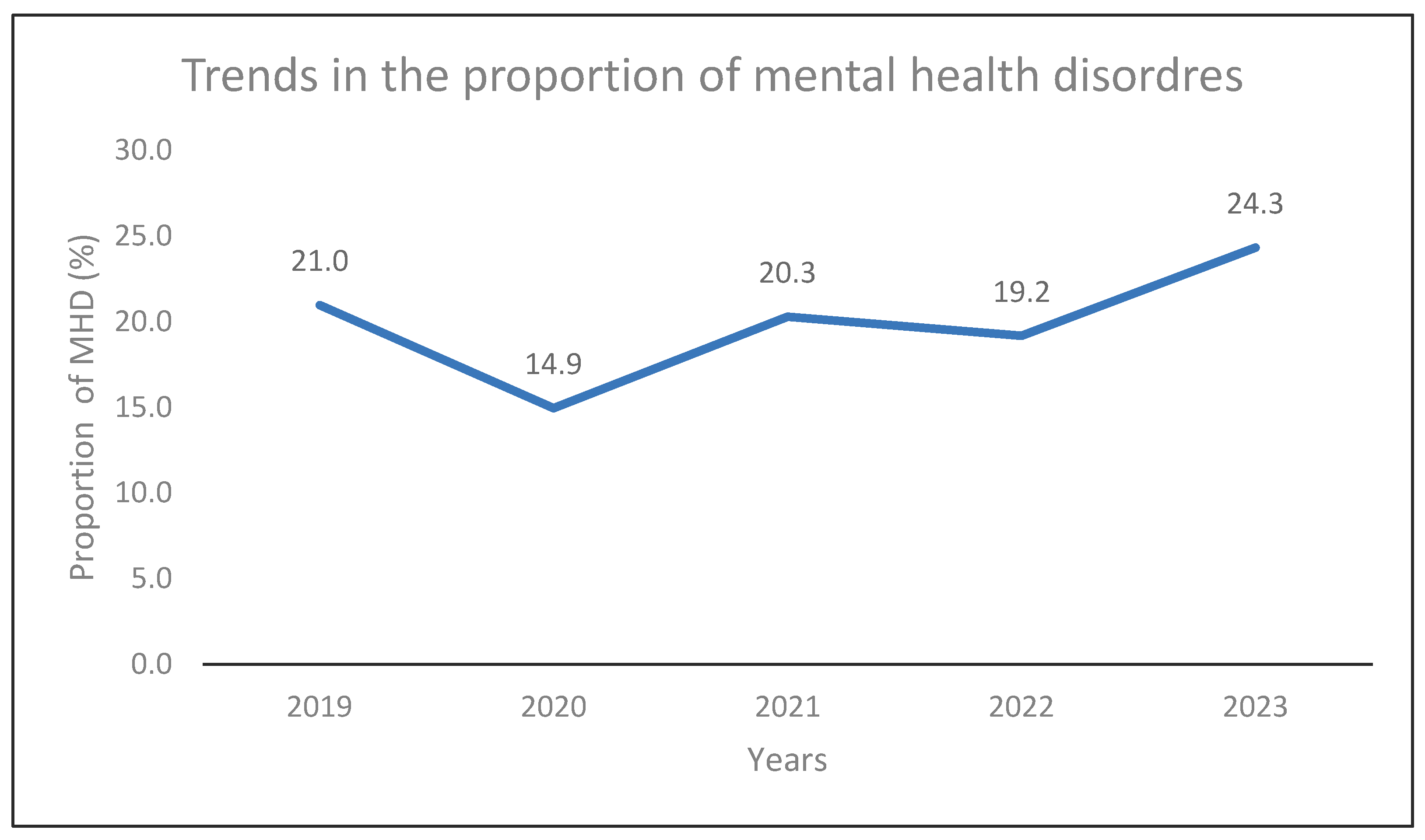

The year, 2023 reported the highest cases of mental health disorders, 24.3% (542/2228), and 2020 recorded the lowest cases of 14.9% (333/2228). Error! Reference source not found. Kendall’s tau-b showed a very weak positive correlation (τ = 0.20, p = 0.8065) between time and mental disorders over the 5-year period, but this trend was not statistically significant.

Table 4.

Correlation between mental disorders and climate factors.

Table 4.

Correlation between mental disorders and climate factors.

| Variable |

Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders |

Bipolar related disorders |

Depressive disorders |

Mental health cases |

| Temperature |

rho = -0.1821

P = 0.1637 |

rho = 0.0005

P = 0.9971 |

rho = 0.0837

P = 0.5249 |

rho = -0.0396

P = 0.7640 |

| Relative humidity |

rho = -0.2859

P = 0.0268* |

rho = -0.2161

P = 0.0973 |

rho = -0.3732

P = 0.0033* |

rho = -0.3620

P = 0.00458* |

| Rainfall |

rho = -0.0261

P = 0.8431 |

rho = -0.1339

P = 0.3078 |

rho = -0.1351

P = 0.3032 |

rho = -0.1407

P = 0.2835 |

Figure 2.

Proportion of mental health disorders over the period of 2019 to 2023.

Figure 2.

Proportion of mental health disorders over the period of 2019 to 2023.

Without controlling for seasonality and long-term trends, fitting a Poisson time series model for mental disorders with temperature as the only explanatory variable suggests that each unit increase in temperature is associated with a lower risk of mental disorders with a risk ratio (RR) of 0.951 (95% CI = 0.813-1.111, P = 0.529). Fitting the model with relative humidity as the only explanatory variable and no adjustment for seasonality and long-term trends suggests that each unit increase in relative humidity is associated with a lower risk of mental disorders; RR = 0.980 (95% CI = 0.966-0.994, P = 0.006).

After adjusting for seasonality and long-term trends using the Spline function, fitting a Poisson model for temperature and mental disorders suggests that the direction of the estimated effect does not change; RR = 0.963 (95% CI = 0.851-1.091, P = 0.560). Fitting the model for relative humidity and mental disorders, adjusting for seasonality and long-term trends suggests that the direction of the estimated effect reverses; RR = 0.979 (95% CI = 0.958-1.000, P = 0.057). The correlation between relative humidity and schizophrenia spectrum disorders was a weak negative one, and this was statistically significant (rho = -0.2859, P = 0.0268), the correlation between RH and depressive disorders was also a weak negative one, and this was statistically significant (rho = -0.3732, P = 0.0033).

4. Discussion

The fluctuations in the proportion of mental disorders observed during the study period; the lowest recorded in 2020 and highest in 2023, may reflect the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Limited access to mental health services during lockdowns likely contributed to underreporting in 2020, while post-pandemic effects like grief, job loss, and heightened awareness of mental health contributed to the subsequent rise [

22]. The availability of mental health professionals and specialized facilities, such as Butabika National Referral Hospital, in Kampala may explain the high prevalence recorded, as cases are more likely to be identified and managed. The increasing burden of mental health disorders underscores the growing burden on Uganda’s already strained mental health system, particularly in Kampala’s urban setting.

Humidity had a negative correlation with mental health disorders, implying that higher humidity levels might offer a degree of protection against mental illness. These findings contradict some of the existing literature on mental health and relative humidity [

8,

23,

24]. Ding and colleagues reported that when the weather is extremely humid, the harmful effect of increasing heat on distress is approximately doubled. In hot months, when the average maximum temperature rises above about 29°C, high humidity is associated with greater distress; but in cool months when the average maximum temperature is below 18°C, high humidity is associated with less distress [

8].

While our study found no correlation between temperature and mental health disorders, most studies that have been conducted on temperature and mental health found that temperature has a positive correlation with poor mental health outcomes [

2,

4,

25]. Studies have shown that persons with pre-existing mental health disorders are more vulnerable to the mental health impacts of heat stress. Heat waves exacerbate underlying mental illnesses and behavioural disorders [

26]; commonly among patients with schizophrenia and substance use disorders due to poor thermoregulation associated with psychotropic medication [

10,

27].

In-depth longitudinal studies using daily data should therefore be done to better understand the correlation between climate factors and mental health disorders. Daily averages capture acute extremes of climate indicators and also numbers of mental health disorders while monthly averages tend to mask these. Daily averages also provide more data points which enable one to analyse lagged effects hence detecting casual patterns and increasing statistical power. Our study reported the highest temperature of 24.30C while the lowest was 21.50C, with no extremes of temperature recorded during the five-year study period. This may explain why there was no statistical significance between the association of temperature and mental health disorders.

Most of the studies that have been carried out on the effect of temperature or relative humidity on mental health combined the two climate factors, and the positive correlation of relative humidity and poor mental health outcomes was reported when temperatures exceeded 30

0C [

8,

10,

23,

27]. Even though our study reported RH greater than 70% during some months, no extremes of temperature were recorded throughout the study period. This may explain the inconsistency in our findings and those reported by previous studies.

The negative correlation reported by this study may reflect an adaptation or threshold effect, where mild increases in climatic stressors like temperature or humidity may not necessarily induce psychological distress, and in some cases, could be perceived as less discomforting compared to extremes. For instance, moderately warm temperatures might alleviate certain depressive symptoms exacerbated by colder conditions. In addition, behavioural patterns during adverse weather conditions might alter exposure risks. During particularly humid or rainy periods, individuals may remain indoors more frequently, thereby avoiding environmental stimuli or social stressors that could worsen psychiatric symptoms. This reduced exposure may lead to a temporary reduction in symptom exacerbation or even fewer hospital visits.

Although associations have been shown globally between climate change and mental ill health elsewhere, there has been a gap in this area in Africa [

28], including Uganda even though it is among global hotspots for high vulnerability to climate change. This study therefore contributes significant information to the body of research which provides baseline information from which future studies can be based.

A critical limitation encountered in this study was the poor state of medical records, particularly in terms of completeness and consistency. Missing variables such as patient numbers, diagnosis, and patient demographics, were common, resulting in the exclusion of a significant number of cases from data extraction and the final analysis reducing the precision and power of the study. This undermines the reliability and utility of routine health information for research and planning purposes. The absence of standardized electronic medical records (EMRs) in many facilities further exacerbates this challenge. In institutions where EMRs are partially implemented, inconsistent data entry, lack of real-time updates, and limited integration across departments reduce the potential benefits of digital health information systems. The transition to a fully functional EMR system, with mandatory fields, standardized templates, and regular staff training, is essential to improve data quality.

5. Conclusions

This study revealed a rising trend in mental health disorders in Kampala between 2019 and 2023. The analysis of climate variables showed that temperature, relative humidity, and rainfall had weak or no correlation with mental disorder trends, with only relative humidity exhibiting a statistically significant weak negative association. These findings indicate that meteorological factors alone do not sufficiently explain the observed trends in mental health disorders. Future research should consider longitudinal methods to better understand complex, multi-causal pathways through which climate change affects mental health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, OA, RN and JBI.; methodology, OA, RN and JBI.; software, OA.; validation, RN, JBI and LA.; formal analysis, OA; investigation, OA.; resources, OA; data curation, OA.; writing—original draft preparation, OA.; writing—review and editing, RN, JBI and LA.; visualization, RN, JBI and LA.; supervision, RN, JBI and LA.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of Makerere University School of Public Health (protocol number: 472) on 2nd July 2024. Administrative clearance was obtained from Butabika Hospital before accessing the hospital registers or the patient files.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of climate factors data. Data were obtained from UNMA and are available from the corresponding author with the permission of UNMA. The raw data on mental disorders supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express sincere gratitude to staff and administrators of Butabika National Referral Mental Hospital, and Uganda National Metrological authority for availing the data that was used in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BNRMH |

Butabika National Referral Mental Hospital |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| DSM |

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders |

| EMR |

Electronic Medical Records |

| KCCA |

Kampala capital City Authority |

| MHD |

Mental Health Disorder |

| PTSD |

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder |

| R.A |

Research Assistants |

| R.H |

Relative Humidity |

| RR |

Risk Ratio |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| SSA |

Sub Saharan Africa |

| UNMA |

Uganda National Metrological Authority |

References

- Berry, H.L.; Bowen, K.; Kjellstrom, T. Climate change and mental health: a causal pathways framework. International journal of public health 2010, 55, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlson, F.; Ali, S.; Benmarhnia, T.; Pearl, M.; Massazza, A.; Augustinavicius, J.; Scott, J.G. Climate change and mental health: a scoping review. International journal of environmental research and public health 2021, 18, 4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianconi, P.; Betrò, S.; Janiri, L. The impact of climate change on mental health: a systematic descriptive review. Frontiers in psychiatry 2020, 11, 490206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Wong, M. Global climate change and mental health. Current Opinion in Psychology 2020, 32, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.-T.; Lin, P.-H.; Guo, Y.-L.L. Long-term exposure to high temperature associated with the incidence of major depressive disorder. Science of the total environment 2019, 659, 1016–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.; Funk, M.; Chisholm, D. Comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2020. EMHJ-Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 2015, 21, 461–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Fact sheet: Mental Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders (accessed on 8 June 2024).

- Ding, N.; Berry, H.L.; Bennett, C.M. The importance of humidity in the relationship between heat and population mental health: Evidence from Australia. PloS one 2016, 11, e0164190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, L.A.; Hajat, S.; Kovats, R.S.; Howard, L.M. Temperature-related deaths in people with psychosis, dementia and substance misuse. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2012, 200, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vida, S.; Durocher, M.; Ouarda, T.B.; Gosselin, P. Relationship between ambient temperature and humidity and visits to mental health emergency departments in Québec. Psychiatric Services 2012, 63, 1150–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D.C.; Tignor, M.; Poloczanska, E.; Mintenbeck, K.; Alegría, A.; Craig, M.; Langsdorf, S.; Löschke, S.; Möller, V. IPPC 2022: Climate Change 2022: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: working group II contribution to the sith assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Mental health and climate change: Policy brief; WHO, Ed.; World Health Organization, 2022; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Opoku, S.K.; Filho, W.L.; Hubert, F.; Adejumo, O. Climate change and health preparedness in Africa: analysing trends in six African countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodman, D.; Hayward, B.; Pelling, M.; Castán Broto, V.; Chow, W.; Chu, E.; Dawson, R.; Khirfan, L.; McPhearson, T.; Prakash, A. Cities, settlements and key infrastructure; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Aid, I. Uganda Climate Action Report for 2016; 2017; pp. 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- KCCA. Kampala Climate Change Action Strategy. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UBOS. The National Population and Housing Census 2024. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- BNRMH. Butabika Hospital. Available online: https://www.butabikahospital.go.ug/ (accessed on 20 Febuary 2024).

- UNMA. Available online: https://unma.go.ug/about/who-we-are (accessed on 6th May 2024).

-

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition ed.; Arlington, V., Ed.; American Psychiatric Pub: Washington DC, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskaran, K.; Gasparrini, A.; Hajat, S.; Smeeth, L.; Armstrong, B. Time series regression studies in environmental epidemiology. International Journal of Epidemiology 2013, 42, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; North, C.S. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. New England journal of medicine 2020, 383, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florido Ngu, F.; Kelman, I.; Chambers, J.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S. Correlating heatwaves and relative humidity with suicide (fatal intentional self-harm). Scientific reports 2021, 11, 22175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razjouyan, J.; Lee, H.; Gilligan, B.; Lindberg, C.; Nguyen, H.; Canada, K.; Burton, A.; Sharafkhaneh, A.; Srinivasan, K.; Currim, F. Wellbuilt for wellbeing: Controlling relative humidity in the workplace matters for our health. Indoor air 2020, 30, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotgé, J.-Y.; Fossati, P.; Lemogne, C. Climate and prevalence of mood disorders: A cross-national correlation study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2014, 75, 2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodland, L.; Ratwatte, P.; Phalkey, R.; Gillingham, E.L. Investigating the health impacts of climate change among people with pre-existing mental health problems: a scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 5563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmeltz, M.T.; Gamble, J.L. Risk characterization of hospitalizations for mental illness and/or behavioral disorders with concurrent heat-related illness. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0186509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwoli, L.; Muhia, J.; Merali, Z. Mental health and climate change in Africa. BJPsych international 2022, 19, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).