1. Introduction

Urban public transport is one of the primary contributors to energy consumption in transportation worldwide [

1], even though it is more efficient than private vehicles in terms of passenger capacity and environmental impact [

2]. However, the use of petroleum-based fuels, derived from fossil sources, is also responsible for a significant increase in greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions and atmospheric pollutant emissions [

3]. Despite the technological progress in the energy system that has been observed with the use of renewable alternative sources, which are less and/or zero-polluting thus mitigating emissions, a complete transition to net-zero emissions requires decarbonization across all areas of energy production and usage, which requires rapid innovation in order to bring clean technologies that will be applied where emissions are most challenging to address, such as urban transportation [

4].

In this context, hydrogen fuel cell vehicle technology has potential benefits in terms of substantial efficiency gains and a moderate transition from fossil fuel-based to renewable energy sources [

5], playing an important role for the Climate Agenda, as a strategy to decarbonize various sectors, from industry to transportation [

6].Apart from the positive steps that have been taken regarding market-available innovations, there is still a need to evaluate the effectiveness of these technologies beyond the operational performance, also requiring a sustainable assessment [

4] through a life cycle approach [

7]. Therefore, the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) seems a valuable tool to provide a comprehensive assessment of the potential environmental impacts considering all the technology life cycle [

8]. Several studies have conducted a LCA of technological alternatives replacing fossil fuel use for urban buses, as observed in the review [

6,

7,

9,

10]. However, the objective of improving the robustness of the method by focusing on system boundaries definition, hydrogen pathways and public transport remains. This paper aims to review the scientific literature regarding LCAs of hydrogen fuel cell buses to provide a comprehensive overview for evidence-based environmental decision-making on urban public transportation. The decision to focus specifically on hydrogen fuel cell buses, despite the limited number of research papers in this area, is driven by the unique role urban buses play in public transportation systems and their potential to significantly reduce GHG emissions in densely populated areas.

By using explicit and systematic methods to minimize biases and provide reliable results, Systematic Literature Review (SLR) is a rigorous and structured method of analysis whose purpose is to identify, evaluate and synthesize all available evidence related to a specific research question [

11]. The process involves a comprehensive and organized search for relevant studies, a critical assessment of the methodological quality of these studies, and the synthesis of the results in order to draw evidence-based conclusions [

12]. Therefore, it contributes to the development not only of an integrated view of the state of the art but also to the identification of knowledge gaps and research opportunities [

13]. In this sense, the novelty of this study lies in its in-depth analysis of LCA methodologies applied to urban bus systems, with a particular focus on hydrogen (H₂) as a key energy carrier. By examining assumptions, functional units (FU), system boundaries, and impact categories, this work not only identifies critical gaps in current research but also highlights the untapped potential of H₂ to enhance sustainability in urban bus transportation. The findings thus provide a foundation for future studies to optimize LCA frameworks for H₂-powered buses and accelerate their adoption as a viable low-emission solution.

This study is structured as follows:

Section 1 presents a contextualization of the topic and the goal of the study;

Section 2 summarizes the methodology procedure defined for the collection and analysis of relevant studies;

Section 3 presents the results and discussion;

Section 4 provides final remarks.

2. Materials and Methods

This section outlines the methodology and procedures employed in this study, including the SLR process, the bibliometric analysis, and an overview of existing review articles. It also identifies the research gaps and formulates the research hypothesis to guide the study.

2.1. Methodology Procedure

The present study used a systematic review based on the stages of a Systematic Literature Review (SLR) according to the PRISMA protocol (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses). PRISMA is defined by a set of guidelines with the objective of improving the quality and transparency of reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses, providing a clear framework with essential items to be included in the review through a checklist, which ensures a comprehensive approach [

12,

14]. PRISMA check list is widely used in several areas besides engineering, such as health care and nature [

15,

16,

17].

Figure 1 shows the procedure of screening and selection of the research articles to be included in this review. This study is limited to analyze LCA studies published in peer-reviewed journals and whose content address technological alternatives for urban buses, including only those that conduct a comparative assessment with hydrogen fuel cell buses.

A broad search was conducted in Scopus, Web of Science (WoS) and Google Scholar [

18,

19]. Although it is known that Google Scholar is less reliable [

20], it was included in this study due to the limited number of specific studies available in this area. The structured keywords used for the literature search in these databases were 'life cycle assessment' and its acronym, 'hydrogen', 'bus', and 'public transport'. Initially, 119 studies were found, and BibText files resulting from the searches in the databases were imported into RStudio, converted and merged. Then, duplicates were removed, resulting in 85 records. Given that Scopus and WoS databases may contain the same documents in different forms, the existence of persistent duplicates is possible. Therefore, the records were exported to Excel and manually checked. Then, it was reduced to 62 after excluding documents that were not articles or conference papers. A total of 42 documents were deemed eligible after excluding studies irrelevant to the topic by reviewing the abstracts and contents of each study. These selected studies utilised the LCA methodology, allowing for the assessment of their objectives and scope. It should be noted that 2 more studies were included in the analysis because gaps in the literature review regarding the systematization of hydrogen production routes have been observed.

As bibliometric analyses can potentially offer a systematic and transparent review approach, grounded in the statistical measurement of science [

21], a bibliometric analysis was carried out considering the 52 studies from the screening phase. The results of this bibliometric analysis pointed out the distribution of publications and citations across time and space, the most productive and influential authors, institutions and countries, and the publications patterns and main topics. The Bibliometric package available on RStudio was used to investigate metadata, then Biblioshiny was deployed for data analysis

2.2. Overview of the Existing Review Articles

There are few studies dealing with LCA of technological alternatives to the use of fossil fuels for urban buses [

6,

7,

9,

10]. Noussam et al. [

6] conducted a systemic and strategic analysis of key aspects related to the implementation of an energy system based on green and blue hydrogen technologies, including market and geopolitical perspectives. They compared the pathways of green and blue hydrogen production by assessing their potential contributions to supporting a low-carbon energy system, especially in geographic regions where renewable energy capacity may be insufficient. Their results contribute to understand the complexity of the hydrogen value chain, which still faces significant challenges in energy efficiency, transportation and storage, underscoring the need for clear approaches and adaptive strategies to achieve acceptable costs. Deliali et al. [

7] investigated zero-emission bus (ZEB) implementations across the United States (USA) by taking primary data and key variables related to energy efficiency, operation and maintenance costs for driving public policies towards ZEB implementation. Liu et al. [

9] conducted a meta-analysis of 76 selected articles reviewing life cycle assessment (LCA) frameworks applied to alternative fuels (AFs) across various vehicle types (cars, buses, trucks, tractors, etc.). The authors identified critical emission points through simulations and operational conditions of these vehicles globally, while also assessing future research directions. However, they noted a lack of studies focusing on public transportation and developing countries, suggesting that future research should prioritize acquiring reliable data, developing comprehensive LCA frameworks for different AFs, conducting in-depth analysis of critical emission points and other impacts, and giving greater attention to regions with potential for AF development. Ally et al. [

10] analyzed trends and trajectories in energy use and emissions in the Australian road transport sector and concluded that, by 2032, the energy consumption by heavy vehicles is expected to surpass that of light vehicles. Finally, Wijayasekera et al. [

22] reviewed the role of hydrogen fuel cell buses (HFCBs) in the hydrogen economy, highlighting their potential as a key mode of sustainable, road-based public transport. The review summarized the most promising clean hydrogen production pathways and examined the latest techno-economic and socio-environmental research trends for HFCBs.

2.3. Work Gap and Research Hypothesis

It can be concluded from the available review articles relevant to the topic, that most works followed a general trend of dealing with energy use, atmospheric emissions, technical challenges, economic and geopolitical implications. On the contrary, this paper contributes to a novel systematic and specific discussion of key aspects for decision-making considering LCA methodology focused on urban public transportation by hydrogen fuel cell buses. This study attempts to capture the range of existing work in the mentioned area by answering the following research questions:

What is the significance of the topic? Which terms have emerged in relation to it over time?

How have the vehicle life cycle and fuel life cycle been addressed in LCA studies on hydrogen cell buses?

Which environmental life cycle impact categories are most assessed? How is environmental performance linked with the other dimensions of sustainability (economic and social) for decision-making?

Which technologies for hydrogen production are frequently evaluated? What are the primary barriers affecting their feasibility?

Which technologies for urban buses are frequently compared to hydrogen cell buses? What are the main differences between them?

3. Results and Discussion

This section presents the findings of the bibliometric analysis and systematic review, focusing on the trends, methodologies, and technologies related to hydrogen fuel cell buses. It also discusses the environmental, economic, and social dimensions of these studies, identifying gaps and opportunities for future research.

3.1. Main Results from the Bibliometric Analysis

The analysis period covers 24 years of scientific production (2001–2024). Since 2018, an increase in the number of published articles has been observed. Besides, the number of scientific articles published in 2024 peaked at more than twice as many as all publications in 2019 (

Figure 2). This demonstrates the growing worldwide attention given to the subject in recent years. The articles came from 29 countries. Poland is the most productive country with 12 articles (8.7% of all articles), followed closely by Australia and the United States with 11 articles each. Most of the publications on the subject are concentrated in the European Continent and the Anglosphere, except for some honorable mentions such as Morocco (8 articles), China and Iran (7 articles each) and Brazil (6 articles). Another relevant information is the number of citations, as it helps measure the scientific impact of a study over time. For this reason, this indicator is usually adopted in bibliometric studies. Although Poland is the country with the most articles published on the subject, it is not the country with the highest number of citations. Italy ranks first in terms of total citations of articles published with 224 citations, as it has the most cited article [

6] with 168 citations. It is then followed by the US (182 citations), Australia (173 citations), Canada (113 citations), Portugal (108 citations), the UK (101) and Germany (96). It’s worth noting that most of the citations are concentrated in the European Continent and the Anglosphere, similarly to the situation verified for total scientific production.

Keywords are provided by authors to synthesize predominant ideas of an article, while keywords plus are extracted from titles of cited references, providing a conceptual base of the article [

23]. Terms such as life cycle, life-cycle assessment, hydrogen, and greenhouse gases have displayed a sharp growth since 2015, reflecting the intensification of research on environmental evaluation and decarbonization pathways in public transport (

Figure 3). Keywords related to environmental burdens - carbon dioxide - also present a steady upward trajectory, indicating their persistent centrality in the academic discourse. By contrast, terms such as buses have grown more gradually, suggesting that while they remain relevant, their conceptual contribution is often embedded in broader analytical frameworks. Overall, the cumulative trend highlights the increasing attention given to life cycle methodologies and hydrogen technologies, consolidating their role as dominant research themes in the transition toward sustainable urban mobility.

Another way to have a good comprehension about research themes and trends on the topic is through the Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA), that condenses complex data featuring multiple variables into a lower-dimensional space, typically a two-dimensional graph (

Figure 4). This graphic presents a biplot derived from a multivariate statistical analysis, likely correspondence analysis or principal component analysis, aimed at exploring the relationships among a set of terms associated with sustainable energy, fuel technologies, and environmental assessments. The horizontal axis, labeled Dim 1, accounts for 56.82% of the total variance in the dataset, while the vertical axis, Dim 2, represents 17.21% of the variance. Together, these two dimensions explain approximately 74% of the total variability, providing a meaningful two-dimensional representation of the data structure. Interpretation of the results hinges on the positions of points and their distribution across dimensions, whereby closer proximity indicates greater similarity [

23]. Terms located near each other tend to appear in similar contexts or exhibit semantic associations.

Cluster 1 (in red) encompasses a cluster containing 47 terms, including key concepts such as “life cycle assessment,” “fuel cell,” “hydrogen,” “greenhouse gases,” “electric buses,” and “carbon dioxide.” This grouping suggests a dominant thematic concentration on renewable energy technologies, hydrogen-based systems, emission reduction strategies, and sustainable public transport. The dense proximity of these terms indicates a high degree of co-occurrence or semantic association within the analyzed corpus, reflecting their frequent joint appearance in academic or technical publications related to environmental technologies.

Cluster 2 (in blue) includes 5 terms focusing on alternative fuels and on practical implementation within the bus transport sector, while emphasizing emission. The relative isolation and cohesive positioning of these terms imply a distinct thematic subset more closely linked to environmental regulatory frameworks, strategic fuel alternatives, and policy-oriented approaches to sustainable mobility.

3.2. Results of the Systematic Review

Considering that LCA studies can be expanded in order to include broader sustainability considerations beyond purely environmental impacts [

24].

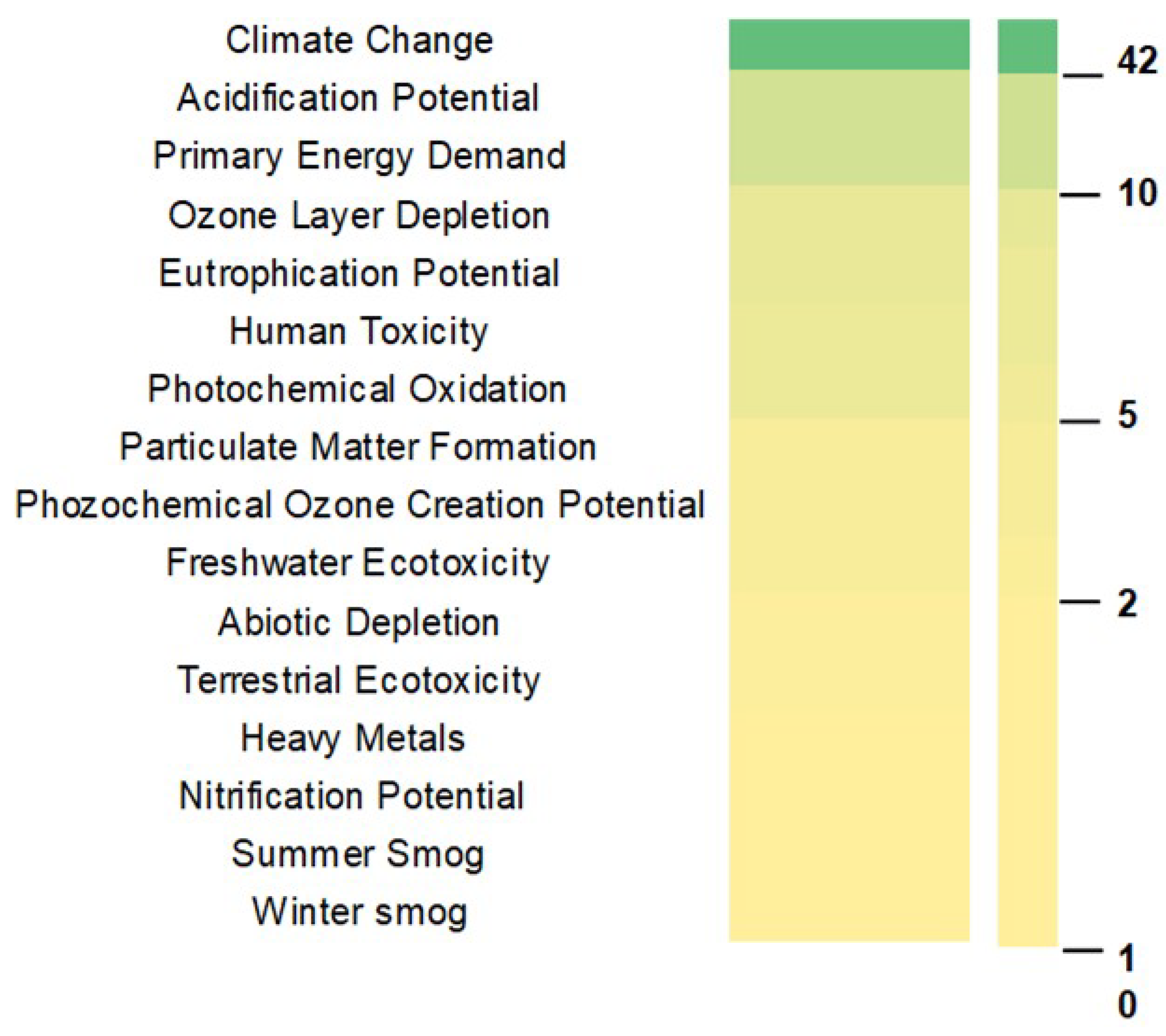

Table 1 summarizes the studies that applied LCA integrated with other economic and/or social indicators, emphasizing the importance of a comprehensive assessment that encompasses environmental, economic and social dimensions. In studies exclusively focused on Environmental Life Cycle Assessment (Env-LCA), it has been observed that all of them evaluated the impact of climate change. Additionally, ten articles examined the potential for acidification [

5,

8,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32], while seven studies investigated primary energy demand [

5,

28,

33,

38,

41,

43,

44]. In studies employing Env-LCA combined with economic analysis, three impact categories were identified: climate change, which was assessed in all studies; acidification potential; and photochemical oxidation [

24].

Energy consumption was examined in four studies [

47,

48,

49,

50]. Regarding economic analyses, the following parameters were evaluated: Lifetime Operation Costs [

45,

46,

54], Total Life Cycle Cost [

45,

46,

49], Maintenance cost [

51], Cost of fuel production [

51,

52], and Levelized Cost of Driving [

50]. It was observed that the high cost and lack of refueling infrastructure are major barriers to the introduction of hydrogen in public transport [

33]. There’s still a need to minimize the costs associated with acquisition, operation and disposal [

34]. Consequently, it is important to assess hydrogen production methods, as they significantly influence operational costs [

35], along with other economic analyses such as the one conducted by Durango-Cohen and McKenzie [

34]. In their analysis, the "shadow price" approach was used in order to provide a monetary measurement to the evaluation of trade-offs between service levels and environmental impact. This approach can be applied to determine robust fleet scenarios (varied headways, number of trips, etc), ensuring configurations that are efficient in both service and environmental impact, thereby offering clearer insights for public transport decision-making.

The systematic categorization of 42 LCA studies on hydrogen fuel cell buses (HFCBs) reveals a predominant focus on environmental assessments (Env-LCA), with 74% (31 studies) exclusively evaluating ecological impacts. Only 24% (10 studies) integrate economic considerations alongside Env-LCA, while a mere 2% (1 study) adopt a holistic triple-bottom-line approach encompassing environmental, economic, and social dimensions. This imbalance underscores a critical gap in literature: the near absence of comprehensive sustainability assessments that align with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy).

There is a noticeable gap in knowledge concerning the social aspect. Only one study addressed the social dimension integrated to LCA, discussing the acceptance of hydrogen as a fuel for public transport, the community's readiness to bear the higher costs associated with this technology and the identification of influential factors affecting this acceptance. The results of [

63] pointed out that the technology issue remains inadequately comprehended as users are frequently disregarded as an option by decision-makers, who tend to place more emphasis on technology performance and the general design of the system rather than user acceptance.

Object and Scope Definition

The stages encompassed by LCA can be categorized as follows: Raw material extraction, entailing the acquisition of natural resources such as oil for diesel production; Infrastructure construction, usually for new developments such as electric vehicles and recharging stations (

Table 2). In the case of fossil fuel vehicles, this infrastructure is often already in place [

64] ; Vehicle manufacturing; Fuel production and preparation; Vehicle operation, representing the vehicle's usage phase; Vehicle maintenance and infrastructure; and End of Life, which involves disposal and recycling.

Fuel life cycle analyses, commonly known as "Well-to-Wheels" (WTW), highlight three key stages: raw material production, fuel refining and bus operations. These stages can be divided into two primary phases. Firstly, the "Well-to-Tank" (WtT) phase involves a range of processes, from raw material production to its transportation to the fuel production site. It encompasses activities along the entire route to the production site. The second phase focuses on fuel transportation, covering all activities from the production site to the bus tank, and it’s known as Tank-to-Wheels (TtW). This phase is crucial for understanding the operational aspects of buses throughout their lifespan [

8,

66,

67,

68].

The analysis of 42 LCA studies reveals a strong correlation between functional unit selection and life cycle phase coverage. For fuel cycle stages (WtT: 95.2%, n=40; TtW: 92.9%, n=39), mass-based functional units (kg Fuel/H₂) predominated, representing 38.5% (15/39) of TtW assessments. In contrast, distance-based units (VKT/p.VKT) were more prevalent in studies examining vehicle production (PROD: 40.5%, n=17), accounting for 64.7% (11/17) of these analyses. Notably, studies employing comprehensive system boundaries (covering ≥5 phases, n=6) showed a 66.7% preference for person-kilometer (p.VKT) units. Energy-based units (MJ/kWh) appeared exclusively in studies (n=4) that included both fuel and electricity infrastructure considerations. This systematic mapping reveals how functional unit selection often reflects study scope, with mass-based units dominating fuel-focused analyses and distance-based units prevailing in vehicle-oriented assessments.

ISO 14040 [

69] underscores the importance of establishing a functional unit (FU) within studies in order to shape the analytical approach, thereby ensuring that all subsequent analyses are relative to this unit. In the realm of comparative analyses, defining a FU is pivotal for meaningful comparisons. In the context of this review, there's a prevalent use of either 1 person-kilometer (p.km) or vehicle kilometer traveled (VKT), depending on the scope of LCA. In studies focusing on the operational phase of buses (TtW), there is a spotlight on fuel consumption, rendering the VKT as a more suitable FU for assessing the impacts of varying technologies. Conversely, in analyses solely concerning fuel production (WtT), there is a higher frequency of employing 1 kg or 1 MJ of fuel, facilitating the correlation of environmental impacts with production, transportation and storage of diverse fuels. Ultimately, differing FUs across studies may render comparative analyses between products and processes unfeasible [

32].

Only Luu et al. [

45] delve into the infrastructure construction phase, covering elements such as road building, operation and maintenance. They drew upon data from the Datasmart database and existing literature for their analysis. The limited detail in less discussed phases, such as vehicle end-of-life considerations, as seen in Lozanovski et al. [

63], is justified by their comparatively minor impact across the lifecycle [

57]. Hence, software databases are also utilized, streamlining data collection for common industrial processes. Moreover, the absence of certain phases from analysis is attributed to data unavailability or difficulty of access. Consequently, there's a clear preference for established and robust database platforms, namely the Ecoinvent database [

30], Simcenter Amesim software [

44] and DataSmart life cycle inventory [

45].

A total of eight softwares were observed in the studies for modelling: ADVISOR, which is a vehicle simulation software employed to optimize powertrain components[

58]; GaBi, which is a comprehensive LCA tool for evaluating environmental and cost impacts, supplying datasets on material and energy flows [

5,

25] ; Greenhouse Gases, Regulated Emissions and Energy Use (GREET), which is a tool for assessing total energy consumption, greenhouse gases emissions and atmospheric pollutant criteria, based on WtW analysis [

8,

31,

44,

48]; OpenLCA, a free LCA tool [

8,

28]; PV simulation software, which is a standard repository for modelling and analysing photovoltaic systems[

60]; SimaPro, a tool commonly featured in the studies, facilitating life cycle modelling, providing uncertainty calculations, insight into unit processes, allocation of multiple output processes, weak point analysis, and complex waste treatment [

26,

29,

31,

39,

45,

46,

47]; Simcenter Amesim, which is employed in vehicle modelling under real driving conditions [

44]; Brightway, an open-source Python-based LCA framework [

62].

The use of PV simulation and Simcenter Amesim software was noted exclusively for specific analysis purposes, such as photovoltaic system simulation [

70] and mechatronics [

71], respectively. Hence, any other software can be employed for economic and environmental impact analysis, depending on availability and ease of access, but with real-world databases to enhance reliability and accuracy. Adequate discussion on each system element is crucial to address complex real-world situations, which are challenging to predict due to software or database calculation idealization that may not faithfully represent actual conditions. Analyses based on real-life cases remain demanding and time-consuming. When comprehensively considering the stages and impacts, evaluating the difference between existing technologies and scenarios for replacing traditional fuels and technologies require careful consideration across key pillars such as environment, economy and society.

Cut-Off Criteria

Cut-off criteria refer to the rules and limits applied with the purpose of excluding elements from the initially defined system. Establishing cut-off criteria plays an important role in the reliability and robustness of the LCA study. For this reason, it is essential to provide a more thorough explanation of both the included and excluded criteria [

72]. In summary, the cut-off criteria should be clearly identified, described and justified. However, in the bulk of the studies reviewed, the exclusion of processes lacked both detail and justification. Consequently, there appears to be an absence of a clear conceptual definition and justified cut-off criteria, overlooking systematic nuances in defining the system boundary as a result. This lack of transparency in the selection of system boundaries and the inadequately detailed cut-off criteria may compromise knowledge construction in the field and hinder comparisons between studies.

Only five studies defined a clear system and justified the cut-off criteria employed in the investigated system, in which the inclusion and exclusion of processes were clearly outlined, and the rationale behind the choices was provided. For instance, [

73] pointed out that the percentage of process exclusion affecting the life cycle balance was less than 1% and provided an example stating that the fleet consumes a portion equivalent to one minute of the total refinery output of a diesel bus system, hence the construction and decommissioning of oil refineries are disregarded. Lombardi et al. [

27] exclude the production of materials that have a weight percentage of less than 1%; however, there are no further details provided for each of the excluded components. Wulf and Kaltschmitt [

36] exclude the process and emissions from the oxidation of organic matter, arguing that there is a compensation: while CO2 is emitted during oxidation, plants absorb this CO2 during their growth, thus suggesting it should be excluded from the analysis. Sanchez et al. [

37] omitted the construction and maintenance of infrastructure associated with vehicle mobility, such as roads, bridges, lighting systems etc. They suggested that this analysis should be incorporated when comparing different modes of transportation, rather than when comparing different technologies and fuels within a single mode of transportation, as was the focus of their study. It must be noticed that identical processes may be omitted in comparative LCAs, referring to those elements that share the same life cycle [

74].

Durango-Cohen and McKenzie [

34] omitted from their analysis the expenses related to maintaining a mixed fleet, including training of workforce, maintenance and infrastructure costs, with the justification that those expenses linked to infrastructure deployment, the heightened operational costs of running heterogeneous bus fleets and similar factors were deemed challenging to estimate accurately. In the study carried out by Logan et al. [

40], the costs linked to carbon emissions integrated into vehicles, including those pertaining to the decommissioning of vehicles out of circulation and manufacturing of new ones, are not directly tackled. As a consequence, their results do not encompass emissions throughout the lifespan of the energy generation cycle, since, in practice, the energy generated by vehicles is considered as part of the wider energy market, which undergoes fluctuations over time. In summary, three main cut-off criteria were identified: challenges in accessing data [

28,

32,

40,

42,

46]; minimal impact of a particular phase and/or component on the overall LCA scenario [

5,

27,

37,

57,

63]; identical processes [

28,

36].

Midpoint Impact Categories

All 42 studies reviewed considered the impact category of Climate Change. In fact, the transport sector is a large generator of GHG emissions into the atmosphere, and projections point out that these emissions could reach 21 billion metric tons in 2050 if substantial policy changes are not implemented [

75]. This number puts on evidence of the concerning situation the world is confronted with, thus underlining the global significance of this impact. In 13 articles, a comprehensive examination of primary energy demand was undertaken, encompassing sources inherently provided by nature. Notably, 2022 witnessed a substantial increase of approximately 45.6% in primary energy consumption, with a predominant share of about 80.5% attributed to non-renewable origins, notably oil, coal and natural gas [

76]. This underscores the urge to scrutinize alternative energy sources and their associated production pathways. Acidification potential and those life cycle categories related to toxicity, as human toxicity and ecotoxicity appeared as relevant environmental impact categories assessed in the reviewed studies (

Figure 5).

While the primary emphasis of this review pertains to LCA studies, thereby concentrating on the environmental facet of sustainability, certain investigations have compiled economic evaluations into the LCA framework, thus furnishing a comprehensive analysis of the sustainability of urban hydrogen transportation by buses. For instance, Lifetime Operation Costs (LOC) was addressed by the authors [

56,

57,

77], who aimed to provide a comprehensive operational expenditure of assets throughout their lifespan, covering maintenance, energy consumption and repairs. A broader approach was considered by the authors [

34,

56,

57] through the Total Life Cycle Cost (TLCC), encompassing the entirety of an asset's costs from procurement to disposal, incorporating operational outlays, maintenance and replacement. The overall expenses associated with vehicle ownership and operation over time, including fuel, maintenance and depreciation, typically on an annual basis, were addressed in the indicator Levelized Cost of Driving (LCD) [

60] . In addition, the Levelized Cost of Hydrogen (LCOH) has been used to determine the minimum average selling price of hydrogen for a supply chain to be profitable, considering factors like transportation and emissions [

62]. Considering that emerging technologies remain comparatively more expensive than their conventional counterparts, and that integrating an economic evaluation into LCA offers a nuanced understanding of their sustainable performance across economic and environmental dimensions, there is an urgent need to develop research dedicated to evaluating these technologies in an integrated and holistic manner. However, this area is still identified as a knowledge gap that requires further investigation.

Furthermore, it was noted that most impacts evaluated in the reviewed studies merely serve as an exposition of results, rather than as actionable insights for decision-making, which is the opposite to the intended purpose of the LCA methodology during its interpretation phase. In this sense, these studies primarily identify stakeholders without providing a comprehensive understanding of their roles, responsibilities and relevance: decision makers [

5,

26,

27,

32,

33,

49,

51,

52,

56,

62]; transport authorities and sector [

5,

45,

49]; managers [

5,

59]; bus industry [

5]; regulatory agencies and policy analysts [

38]; engineers and companies focusing on sustainability [

59]. It must be remarked that stakeholder participation is recognized as a key principle of sustainability in transport sector [

78], thus a proper identification of stakeholders, followed by prioritization, and relating them to sustainable targets and actions are crucial steps in order to achieve a successful stakeholder engagement towards sustainable public transportation.

3.3. Technologies Assessed

The internal combustion diesel bus remains widely used due to its established infrastructure, lower initial costs and greater autonomy compared to electric buses [

79]. Besides the continuous innovation in its combustion efficiency, a significant amount of energy loss still occurs during the vehicle operation, making it the least efficient technology overall [

37]. Cleaner and more efficient transport alternatives to diesel buses have been extensively discussed in scientific literature, and diversifying urban bus energy technologies plays a crucial role in enhancing the environmental sustainability in urban areas. Recent studies reinforce the significance of cleaner and more efficient transport alternatives in reducing harmful atmospheric pollutant emissions and enhancing air quality in cities [

80]. However, the implementation of new technologies for public transportation as alternative to diesel buses are still a challenge in terms of the logistics involved in energy distribution [

58], the production pathways of these energy alternatives, policies, roadmaps adapted to new knowledge and realities [

6], and the innovative infrastructures [

81].

A total of nine types of bus technology alternatives to conventional diesel buses were found in the reviewed studies: ultra-low-sulfur diesel (ULSD), internal combustion buses using biodiesel, natural gas, liquefied petroleum gas, biogas, battery-electric buses, plug-in hybrid fuel cell cell buses, hydrogen fuel electric buses and diesel-electric hybrid buses.

Some studies have demonstrated the feasibility and benefits of using ULSD [

5,

31,

34,

57] and biodiesel [

32], instead of conventional diesel. Ultra-low-sulfur diesel is distinguished by significantly lower sulfur content, which leads to reduced emissions of harmful atmospheric pollutants such as sulfur oxides and fine particles, thereby contributing to improving air quality and public health protection [

82]. Both ULSD and biodiesel represent significant advancements towards more sustainable and environmentally friendly fuel solutions. Certainly, each one with distinct characteristics and environmental benefits that can be strategically applied across different contexts and applications to foster cleaner and more sustainable transportation systems.

Compressed and liquefied natural gas emerges as alternatives, with liquefied natural gas (LNG) being particularly suitable for buses [

83]. According to Ref. [

35], the use of LNG in buses offers advantages over diesel in terms of operational costs and pollutant emissions, since operational costs for LNG are lower than diesel. Moreover, the prices of LNG are more stable than diesel, which can bring advantages for public transport companies. In terms of Tank-to-Wheel (TtW) pollutant emissions, LNG has lower emissions compared to diesel. Briguglio et al. [

26] addressed biogas, highlighting its lower environmental impact compared to LNG, mainly due to its production from organic waste, resulting in significantly reduced GHG emissions. This supports efforts to decrease dependency on fossil fuels and encourage sustainable management of organic waste. For instance, in terms of Well-to-Wheel (WtW) emissions, biogas emits approximately 42.3% less CO2e than natural gas.

Hydrogen vehicles are recognized for their potential to mitigate GHG emissions by utilizing renewable sources such as solar, wind and hydroelectric power for hydrogen production [

46,

48]. Thus, they play a pivotal role in urban air quality improvement, thereby positively impacting public health [

46]. The versatility and reliability of hydrogen supply are bolstered by its availability from diverse sources including biomass, solar and natural gas [

48,

61]. Despite hydrogen being considered an efficient energy carrier via electrolysis with surplus renewable energy, enhancing its overall energy efficiency [

32], its production and utilization processes are perceived as less efficient than those of conventional energy sources due to its inherent energy conversion losses [

61]. Moreover, hydrogen production remains expensive relative to fossil fuels, primarily due to the high energy demand during electrolysis [

29,

35]. Also, the necessary infrastructure for hydrogen production, storage and distribution requires substantial investment, with safety concerns related to leakage and ignition, which demands careful attention [

29,

32]. Therefore, despite the numerous advantages offered by hydrogen vehicles, significant challenges persist in terms of feasibility and promotion needed for their widespread adoption as a viable alternative to diesel-powered vehicles.

Technologies such as battery electric buses and hydrogen fuel cell buses have emerged as promising zero-emission solutions, significantly contributing to the reduction of GHG emissions and local pollutants such as nitrogen oxides [

8,

84]. Moreover, the adoption of buses fueled by biofuels, namely biodiesel and biogas, presents a renewable alternative to fossil fuels, thereby reducing dependence on non-renewable resources and mitigating the environmental impacts associated with their extraction and combustion [

32,

38]. The diversification of energy technologies for urban buses not only aids in decreasing air pollution and GHG emissions but also fosters innovation and promotes sustainable development within the transportation sector, yielding substantial benefits for public health, the environment and urban quality of life [

85].

3.4. Hydrogen Production

This review identified 11 different alternatives of hydrogen production (

Table 3). There is growing attention towards hydrogen production through water electrolysis, particularly when coupled with renewable energy sources such as solar and wind, reflecting a push towards a more sustainable, low-carbon economy [

86]. However, natural gas steam reforming, a fossil fuel-based method, still appears with relevance in the literature due to the widespread availability of natural gas. Biomass Gasification involves converting organic materials into syngas, which is then reformed to produce hydrogen [

36,

41,

42,

45,

48]. In the Coal Gasification process, coal is converted into syngas, which is subsequently purified to obtain hydrogen [

36,

40,

46,

47,

48]. Chlor-alkali Electrolysis is conducted by passing an electric current through a solution of sodium chloride to produce hydrogen and chlorine [

30]. The copper-chlorine cycle uses chemical reactions to produce hydrogen from water and chlorine [

31]. Meanwhile, Dark Fermentation is a biological process in which microorganisms convert organic matter into hydrogen and carbon dioxide in an anaerobic environment [

29,

42]. Natural Gas Steam Reforming and Naphtha Steam Reforming involve the reaction of hydrocarbons with steam to produce hydrogen and carbon monoxide [

5,

56]. Photo fermentation is a biological process that utilizes microorganisms and sunlight to convert organic matter into hydrogen [

29,

42]. Pyro-reforming of glycerol, which combines pyrolysis and gasification, is a process involving the thermal decomposition of glycerol into gases, which are subsequently reformed to produce hydrogen [

36]. Ethanol Steam Reforming (ESR) is a process where ethanol reacts with steam to produce hydrogen and carbon dioxide [

51]. Lastly, Water Electrolysis is a process that requires the passage of an electric current through water to separate hydrogen and oxygen.

Undoubtedly, there is a growing interest in developing alternative processes for hydrogen production based on renewable energy sources. In this sense, certain alternatives are gaining prominence due to various factors. For instance, water electrolysis is increasingly recognized as a promising option, particularly when integrated with renewable energy sources such as solar and wind. This is attributed to its capability to generate carbon-free hydrogen, thereby facilitating the reduction of GHG emissions and fostering the transition towards a low-carbon economy. Biomass gasification and dark fermentation are also becoming increasingly significant for their capacity to produce hydrogen from organic residues, thereby contributing to reducing the dependence on fossil fuels and enhancing the valorization of agricultural and organic waste. These technologies directly address the concerns regarding environmental sustainability and the pursuit of more effective and cleaner energy solutions.

Nevertheless, despite the growing interest in these alternatives, several challenges remain, including high production costs, infrastructure limitations and scalability issues. In this context, steam reforming natural gas and steam reforming naphtha may play an important role in hydrogen production due to their efficiency and abundant feedstock availability. Consequently, while conventional methods currently dominate the sector, there is a huge shift towards cleaner and more sustainable technologies, marked by increasing adoption of hydrogen production approaches rooted in renewable and biological sources. This transition not only reinforces environmental global worries but also creates opportunities for innovation and technological advancements within the energy domain.

3.5. Environmental Aspects

There is broad agreement that FCEBs can cut use-phase GHG emissions relative to diesel fleets, especially in dense urban operation where tailpipe pollutants are also relevant [

29,

32,

46,

48,

51,

52,

53,

54]. The authors generally attribute this consensus to two mechanisms: the elimination of tailpipe emissions for fuel-cell electric powertrains and the potential to decarbonize upstream hydrogen via renewable sources, resulting in substantially lower WTW intensities compared to conventional fossil-based fuels. In addition, the authors highlighted additional improvements in air quality, such as reductions in NOx, CO, and particulate matter [

29,

53].

At the same time, the authors diverge on how large the life-cycle gains are once upstream hydrogen production is considered. Aydin and Dincer [

46], Chugh et al. [

48], Agostinho et al. [

32], and Bairrão et al. [

61] emphasize that the production pathway is the dominant factor shaping environmental outcomes. Renewable electrolysis, waste- or by-product hydrogen, and biomass-based routes generally outperform steam-methane reforming without carbon capture or coal-based options. According to François et al. [

54] and Chugh et al. [

48], electrolysis powered by carbon-heavy grids can substantially reduce the comparative GWP advantages of FCEBs relative to BEBs [

51]. In contrast, Agostinho et al. [

32], Padovan et al. [

51], and Gazda-Grzywacz et al. [

52] report that in high-renewables contexts or when using by-product hydrogen, FCEBs can achieve parity with or near-parity to BEBs in climate performance.

Finally, the literature converges on methodological needs and research gaps, emphasizing the importance of complete life-cycle scopes that include infrastructure, transparent region-specific inventories, explicit consideration of stack degradation and battery aging, and end-of-life recycling modeling, while also highlighting the need for scenario analyses that link policy interventions, such as renewable targets, CCS deployment, and regulatory recycling frameworks, to life-cycle outcomes

3.6. Economic Aspects

From an economic perspective, the reviewed literature broadly converges on the finding that FCEBs face significantly higher upfront capital and infrastructure costs than conventional diesel buses. Both McKenzie and Durango-Cohen [

57] and Barboza [

59] highlighted that the life-cycle cost of hydrogen buses is dominated by vehicle acquisition and refueling infrastructure, making projects unfeasible without subsidies or favorable financial structures. More recent studies reinforce this consensus, with François et al. [

54] demonstrating that fleets composed entirely of hydrogen vehicles entail a higher total cost of ownership compared to battery-electric or diesel alternatives.

At the same time, several studies acknowledge that operational costs for hydrogen buses can be competitive or even favorable relative to diesel, especially under renewable hydrogen supply scenarios [

57,

60]. Another recurring outcome is the strong dependence of hydrogen bus economics on policy and financial support [

59,

61]. Without carbon credits, subsidies, or favorable financing, projects show negative net present values, whereas policy interventions can enable profitability. This reliance is reinforced by evidence that, although green hydrogen costs were around €5/kg in 2020, projected declines to €2/kg by 2030 could render FCEBs competitive under European Green Deal targets [

61].

The literature diverges on the long-term competitiveness of FCEBs relative to battery-electric buses: while some studies find BEBs more advantageous in the near term and hydrogen viable only under specific contexts [

54], others suggest that mixed fleets could balance costs, risks, and emissions, allowing hydrogen to reach economic viability earlier [

60]. Overall, disagreement centers on when and under what conditions hydrogen may achieve cost parity with electric alternatives.

Overall, the reviewed studies align in portraying hydrogen buses as economically constrained by high capital and infrastructure costs, while recognizing their operational competitiveness, especially when renewable hydrogen is used. They also converge on the critical role of subsidies, carbon pricing, and technological learning in improving feasibility.

3.7. Social Aspects

The literature emphasizes that acceptance of FCEBs is strongly linked to their perceived reliability, affordability, and environmental performance. However, dialogue with policymakers and stakeholders indicates that broader legitimacy depends primarily on two conditions: the use of genuinely low carbon ‘green’ hydrogen and cost reductions to competitive levels. In this regard, social sustainability is inseparable from environmental and economic dimensions: although citizens and stakeholders value cleaner air and climate benefits, these alone do not outweigh concerns about affordability and service quality. As Lozanovski et al. [

63] note, without addressing these economic barriers, the social legitimacy of FCEBs is likely to remain fragile. This highlights a key research gap: few studies integrate social acceptance with detailed economic and environmental trade-offs, leaving open the question of how policies and communication strategies can be designed to foster both societal trust and long-term sustainability.

4. Discussion

Over recent years, there has been a notable increase in interest in hydrogen-powered vehicles, driven by growing concerns over GHG emissions in the transportation sector. Since 2006, there has been a notable rise in scientific production on this subject, underscoring its importance over time. These studies highlight various advantages of hydrogen vehicles, such as reduced atmospheric emissions and enhanced energy efficiency, particularly when hydrogen is derived from renewable sources. However, substantial challenges persist, including higher production costs compared to fossil fuels, the necessity for specialized infrastructure, and safety considerations related to hydrogen storage and transport. Nevertheless, despite these challenges, the potential of hydrogen vehicles as an environmentally sustainable alternative for urban and long-distance transportation is widely acknowledged. This recognition is sustained by ongoing technological advancements and research investments aimed at overcoming these barriers. Considering these, hydrogen vehicles offer a promising pathway for mitigating GHG emissions and addressing environmental impacts associated with urban and long-distance transport, thereby positioning them as a strategic measure towards achieving a sustainable and decarbonized economy.

Despite their technical promise, HFCBs face significant adoption barriers. Current costs for fuel cells and renewable hydrogen remain prohibitively high compared to conventional fuels, though projections suggest potential cost parity within a decade if hydrogen prices fall. Crucially, economic viability also depends on infrastructure investments - a major hurdle for regions lacking hydrogen supply chains. Mixed fleets, combining HFCBs with BEB’s for optimized range and topography needs, could offer a transitional pathway. Social acceptance, while generally positive, is tempered by economic concerns among operators and policymakers, who prioritize affordability over environmental benefits. This highlights the need for targeted subsidies and workforce transition plans to address disruptions in traditional automotive sectors.

While current research is pertinent in addressing specific concerns, such as energy efficiency and costs associated with hydrogen vehicles, thereby making them more accessible and viable on large scale, hydrogen fuel cell buses still face primary challenges in terms of LCA methodological approach towards a reliable decision-making, including lack of data, uncertainties caused by variations in data sources, data quality and assumptions adopted, identifying stakeholders and considering their varied perspectives, as well as defining a clear FU that enables comparability, cut-offs for system boundary and system product. Therefore, future research should prioritize acquiring reliable and valid data, establishing a comprehensive LCA for different alternative fuels, and conducting detailed discussions and analyses of critical emission points and other impacts. Furthermore, it is imperative for future studies to incorporate strategic plans as integral components of their final analyses, such as roadmaps. Integrating these plans into urban bus evaluations not only offers a comprehensive perspective on available alternatives but also facilitates a more precise assessment of energy production pathways. This approach is indispensable for comprehending the potential environmental, social and economic impacts of various energy options, and for guiding policies and strategies towards sustainable development.

Moreover, incorporating these plans enables anticipation and adaptation to forthcoming technological and regulatory changes that will shape the future of urban public transport. By integrating strategic plans into our analyses, it is possible to ensure a seamless transition to more efficient, clean and resilient transportation systems that meet the evolving needs of urban communities. Through an integrated and collaborative partnership among governments, industry and the academic community, advancements towards a cleaner and sustainable future in transportation are achievable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C. Padovan and A.C.M. Angelo; methodology, C. Padovan; software, C. Padovan and P.J.P. Carneiro; validation, C. Padovan, A.C.M. Angelo and M.A. D’Agosto; formal analysis, C. Padovan; investigation, C. Padovan; resources, C. Padovan; writing—original draft preparation, C. Padovan, A.C.M. Angelo; writing—review and editing, C. Padovan and A.C.M. Angelo; supervision, A.C.M. Angelo and M.A. D’Agosto; project administration, M.A. D’Agosto. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding” or “This research was funded by NAME OF FUNDER, grant number XXX” and “The APC was funded by XXX”. Check carefully that the details given are accurate and use the standard spelling of funding agency names at https://search.crossref.org/funding. Any errors may affect your future funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Transport Engineering Program (PER/COPPE/UFRJ) for institutional support and the Laboratory of Cargo Transport (LTC) for valuable technical discussions. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Biblioshiny (Bibliometrix R package) to process metadata and generate bibliometric indicators, maps, and figures, and ChatGPT (GPT-5, OpenAI, 2025) for language refinement and text structuring. The authors have reviewed and edited all tool outputs and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AFs |

Alternative Fuels |

| CO2 |

Carbon Dioxide |

| Env-LCA |

Environmental Life Cycle Assessment |

| EoL |

End of Life |

| FU |

Functional Unit |

| GHG |

Greenhouse Gases |

| IC |

Infrastructure |

| LCA |

Life Cycle Assessment |

| LNG |

Liquefied Natural Gas |

| MAINT |

Vehicle and/or Road Maintenance |

| MCA |

Multiple Correspondence Analysis |

| MJ |

Mega Joules |

| p.km |

Person-Kilometer, Person-Kilometer |

| PRISMA |

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROD |

Vehicle Production |

| RE |

Resource Extraction |

| SLR |

Systematic Literature Review |

| TtW |

Tank-to-Wheel |

| ULSD |

Ultra-low-sulfur Diesel |

| VKT |

Vehicle Kilometer Traveled, Vehicle Kilometer Traveled |

| WoS |

Web of Science |

| WtT |

Well-to-Tank |

| ZEB |

Zero-Emission Bus |

References

- Letnik T, Marksel M, Luppino G, Bardi A, Božičnik S. Review of policies and measures for sustainable and energy efficient urban transport. Energy 2018;163:245–57. [CrossRef]

- Sudhakara Reddy B, Balachandra P. Urban mobility: A comparative analysis of megacities of India. Transp Policy (Oxf) 2012;21:152–64. [CrossRef]

- Sharma A, Strezov V. Life cycle environmental and economic impact assessment of alternative transport fuels and power-train technologies. Energy 2017;133:1132–41. [CrossRef]

- Energy Agency I. Global Energy and Climate Model Documentation 2023. 2023.

- Ally J, Pryor T. Life-cycle assessment of diesel, natural gas and hydrogen fuel cell bus transportation systems. J Power Sources 2007. [CrossRef]

- Noussan M, Raimondi PP, Scita R, Hafner M. The Role of Green and Blue Hydrogen in the Energy Transition—A Technological and Geopolitical Perspective. Sustainability 2020;13:298. [CrossRef]

- Deliali A, Chhan D, Oliver J, Sayess R, Godri Pollitt KJ, Christofa E. Transitioning to zero-emission bus fleets: state of practice of implementations in the United States. Transp Rev 2021;41:164–91. [CrossRef]

- Jelti F, Allouhi A, Al-Ghamdi SG, Saadani R, Jamil A, Rahmoune M. Environmental life cycle assessment of alternative fuels for city buses: A case study in Oujda city, Morocco. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2021;46:25308–19. [CrossRef]

- Liu F, Shafique M, Luo X. Literature review on life cycle assessment of transportation alternative fuels. Environ Technol Innov 2023;32:103343. [CrossRef]

- Ally J, Pryor T, Pigneri A. The role of hydrogen in Australia’s transport energy mix. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2015;40:4426–41. [CrossRef]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000100. [CrossRef]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. [CrossRef]

- Shoaib M, Lim MK, Wang C. An integrated framework to prioritize blockchain-based supply chain success factors. Industrial Management & Data Systems 2020;120:2103–31. [CrossRef]

- Paul J, Criado AR. The art of writing literature review: What do we know and what do we need to know? International Business Review 2020;29:101717. [CrossRef]

- Buchwald H, Buchwald JN, McGlennon TW. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Medium-Term Outcomes After Banded Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. Obes Surg 2014;24:1536–51. [CrossRef]

- Vieira LC, Amaral FG. Barriers and strategies applying Cleaner Production: a systematic review. J Clean Prod 2016;113:5–16. [CrossRef]

- Hori S, Shimizu Y. Designing methods of human interface for supervisory control systems. Control Eng Pract 1999;7:1413–9. [CrossRef]

- Belter CW, Seidel DJ. A bibliometric analysis of climate engineering research. WIREs Climate Change 2013;4:417–27. [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Lim MK, Lyons A. Twenty years of the International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications: a bibliometric overview. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications 2019;22:304–23. [CrossRef]

- Camarasa C, Nägeli C, Ostermeyer Y, Klippel M, Botzler S. Diffusion of energy efficiency technologies in European residential buildings: A bibliometric analysis. Energy Build 2019;202:109339. [CrossRef]

- Aria M, Cuccurullo C. bibliometrix : An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J Informetr 2017;11:959–75. [CrossRef]

- Wijayasekera SC, Hewage K, Razi F, Sadiq R. Fueling tomorrow’s commute: Current status and prospects of public bus transit fleets powered by sustainable hydrogen. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2024;66:170–84. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Yu Q, Zheng F, Long C, Lu Z, Duan Z. Comparing keywords plus of WOS and author keywords: A case study of patient adherence research. J Assoc Inf Sci Technol 2016;67:967–72. [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen A, Finkbeiner M, Jørgensen MS, Hauschild MZ. Defining the baseline in social life cycle assessment. Int J Life Cycle Assess 2010;15:376–84. [CrossRef]

- Binder M, Faltenbacher M, Fischer M. Hydrogen as fuel for urban transportation environmental footprint of different hydrogen production routes and the influence on the total life cycle of FC powered transportation systems - An LCA case study within CUTE. Materials Research Society Symposium Proceedings, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Briguglio N, Andaloro L, Ferraro M, Di Blasi A, Dispenza G, Matteucci F, et al. Renewable energy for hydrogen production and sustainable urban mobility. Int J Hydrogen Energy, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Lombardi L, Carnevale E, Corti A. Life cycle assessment of different hypotheses of hydrogen production for vehicle fuel cells fuelling. International Journal of Energy and Environmental Engineering 2011.

- Tahir S, Hussain M. Life Cycle Assessment of Hydrogen Fuelcell-Based Commercial and Heavy-Duty Vehicles. ASME 2020 Power Conference, American Society of Mechanical Engineers; 2020. [CrossRef]

- Aydin MI, Dincer I. A life cycle impact analysis of various hydrogen production methods for public transportation sector. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2022;47:39666–77. [CrossRef]

- Pederzoli DW, Carnevali C, Genova R, Mazzucchelli M, Del Borghi A, Gallo M, et al. Life cycle assessment of hydrogen-powered city buses in the High V.LO-City project: integrating vehicle operation and refuelling infrastructure. SN Appl Sci 2022;4:57. [CrossRef]

- Aydin MI, Dincer I, Ha H. Development of Oshawa hydrogen hub in Canada: A case study. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2021;46:23997–4010. [CrossRef]

- Agostinho F, Serafim Silva E, Silva CC da, Almeida CMVB, Giannetti BF. Environmental performance for hydrogen locally produced and used as an energy source in urban buses. J Clean Prod 2023;396:136435. [CrossRef]

- Cantono S, Heijungs R, Kleijn R. Environmental accounting of eco-innovations through environmental input-output analysis: The case of hydrogen and fuel cells buses. Economic Systems Research 2008. [CrossRef]

- Durango-Cohen PL, McKenzie EC. Trading off costs, environmental impact, and levels of service in the optimal design of transit bus fleets. Transportation Research Procedia 2017;23:1025–37. [CrossRef]

- Migliarese Caputi MV, Coccia R, Venturini P, Cedola L, Borello D. Assessment of Hydrogen and LNG buses adoption as sustainable alternatives to diesel fuel buses in public transportation: Applications to Italian perspective. E3S Web of Conferences 2022;334:09002. [CrossRef]

- Wulf C, Kaltschmitt M. Life cycle assessment of hydrogen supply chain with special attention on hydrogen refuelling stations. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2012;37:16711–21. [CrossRef]

- García Sánchez JA, López Martínez JM, Lumbreras Martín J, Flores Holgado MN, Aguilar Morales H. Impact of Spanish electricity mix, over the period 2008-2030, on the Life Cycle energy consumption and GHG emissions of Electric, Hybrid Diesel-Electric, Fuel Cell Hybrid and Diesel Bus of the Madrid Transportation System. Energy Convers Manag 2013. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Gbologah FE, Lee DY, Liu H, Rodgers MO, Guensler RL. Assessment of alternative fuel and powertrain transit bus options using real-world operations data: Life-cycle fuel and emissions modeling. Appl Energy 2015. [CrossRef]

- Chang CC, Liao YT, Chang YW. Life cycle assessment of carbon footprint in public transportation - A case study of bus route no. 2 in Tainan City, Taiwan. Procedia Manuf, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Logan KG, Nelson JD, Hastings A. Electric and hydrogen buses: Shifting from conventionally fuelled cars in the UK. Transp Res D Transp Environ 2020;85:102350. [CrossRef]

- Iannuzzi L, Hilbert JA, Silva Lora EE. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) for use on renewable sourced hydrogen fuel cell buses vs diesel engines buses in the city of Rosario, Argentina. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2021;46:29694–705. [CrossRef]

- Lui J, Sloan W, Paul MC, Flynn D, You S. Life cycle assessment of waste-to-hydrogen systems for fuel cell electric buses in Glasgow, Scotland. Bioresour Technol 2022;359:127464. [CrossRef]

- Chang C-C, Huang P-C. Carbon footprint of different fuels used in public transportation in Taiwan: a life cycle assessment. Environ Dev Sustain 2022;24:5811–25. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi P, Raeesi M, Changizian S, Teimouri A, Khoshnevisan A. Lifecycle assessment of diesel, diesel-electric and hydrogen fuel cell transit buses with fuel cell degradation and battery aging using machine learning techniques. Energy 2022;259:125003. [CrossRef]

- Luu LQ, Riva Sanseverino E, Cellura M, Nguyen H-N, Tran H-P, Nguyen HA. Life Cycle Energy Consumption and Air Emissions Comparison of Alternative and Conventional Bus Fleets in Vietnam. Energies (Basel) 2022;15:7059. [CrossRef]

- Aydin MI, Dincer I. An assessment study on various clean hydrogen production methods. Energy 2022;245:123090. [CrossRef]

- Karaca AE, Dincer I, Nitefor M. Development and analysis of new pneumatic based powering options for transit buses: A comparative assessment. Energy Convers Manag 2022;256:115399. [CrossRef]

- Chugh S, Chaudhari C, Sharma A, Kapur GS, Ramakumar SSV. Comparing prospective hydrogen pathways with conventional fuels and grid electricity in India through well-to-tank assessment. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2022;47:18194–207. [CrossRef]

- Grazieschi G, Zubaryeva A, Sparber W. Energy and greenhouse gases life cycle assessment of electric and hydrogen buses: A real-world case study in Bolzano Italy. Energy Reports 2023;9:6295–310. [CrossRef]

- Lubecki A, Szczurowski J, Zarębska K. A comparative environmental Life Cycle Assessment study of hydrogen fuel, electricity and diesel fuel for public buses. Appl Energy 2023;350:121766. [CrossRef]

- Padovan C, Fagundes JAG, D’Agosto M de A, Angelo ACM, Carneiro PJP. Impact of Fuel Production Technologies on Energy Consumption and GHG Emissions from Diesel and Electric–Hydrogen Hybrid Buses in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Sustainability 2023;15:7400. [CrossRef]

- Gazda-Grzywacz M, Grzywacz P, Burmistrz P. Environmental Benefits of Hydrogen-Powered Buses: A Case Study of Coke Oven Gas. Energies (Basel) 2024;17:5155. [CrossRef]

- Syré AM, Shyposha P, Freisem L, Pollak A, Göhlich D. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Battery and Fuel Cell Electric Cars, Trucks, and Buses. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2024;15:114. [CrossRef]

- François A, Roche R, Grondin D, Winckel N, Benne M. Investigating the use of hydrogen and battery electric vehicles for public transport: A technical, economical and environmental assessment. Appl Energy 2024;375:124143. [CrossRef]

- Zhao C, Kobayashi LZ, Alquaity ABS, Monfort J-C, Cenker E, Miralles N, et al. Solutions for decarbonising urban bus transport: a life cycle case study in Saudi Arabia. Communications Engineering 2024;3:95. [CrossRef]

- Lee JY, Cha KH, Lim TW, Hur T. Eco-efficiency of H2 and fuel cell buses. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2011. [CrossRef]

- McKenzie EC, Durango-Cohen PL. Environmental life-cycle assessment of transit buses with alternative fuel technology. Transp Res D Transp Environ 2012. [CrossRef]

- Ribau JP, Silva CM, Sousa JMC. Efficiency, cost and life cycle CO2 optimization of fuel cell hybrid and plug-in hybrid urban buses. Appl Energy 2014. [CrossRef]

- Barboza C. Towards a Renewable Energy Decision Making Model. Procedia Comput Sci 2015;44:568–77. [CrossRef]

- Coppitters D, Verleysen K, De Paepe W, Contino F. How can renewable hydrogen compete with diesel in public transport? Robust design optimization of a hydrogen refueling station under techno-economic and environmental uncertainty. Appl Energy 2022;312:118694. [CrossRef]

- Bairrão D, Soares J, Almeida J, Franco JF, Vale Z. Green Hydrogen and Energy Transition: Current State and Prospects in Portugal. Energies (Basel) 2023;16:551. [CrossRef]

- Montignac F, Larrahondo Chavez D, Arpajou M-C, Ruby A. Assessment of hydrogen supply chains based on dynamic bi-objective optimization of costs and greenhouse gases emissions: Case study in the context of Balearic Islands. Energy 2024;308:132590. [CrossRef]

- Lozanovski A, Whitehouse N, Ko N, Whitehouse S. Sustainability Assessment of Fuel Cell Buses in Public Transport. Sustainability 2018;10:1480. [CrossRef]

- Cooney G, Hawkins TR, Marriott J. Life Cycle Assessment of Diesel and Electric Public Transportation Buses. J Ind Ecol 2013;17:689–99. [CrossRef]

- Pivac I, Šimunović J, Barbir F, Nižetić S. Reduction of greenhouse gases emissions by use of hydrogen produced in a refinery by water electrolysis. Energy 2024;296:131157. [CrossRef]

- Larsson M, Mohseni F, Wallmark C, Grönkvist S, Alvfors P. Energy system analysis of the implications of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles in the Swedish road transport system. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2015;40:11722–9. [CrossRef]

- Gao L. Well-to-Wheels Analysis of Energy Use and Greenhouse Gas Emissions for Alternative Fuels. Int J Appl Sci Technol 2011;1:1–8.

- Wang Q, Xue M, Lin B-L, Lei Z, Zhang Z. Well-to-wheel analysis of energy consumption, greenhouse gas and air pollutants emissions of hydrogen fuel cell vehicle in China. J Clean Prod 2020;275:123061. [CrossRef]

- ISO. 14040: Environmental management–life cycle assessment—Principles and framework. International Organization for Standardization 2006.

- SIEMENS. Simcenter Amesim software 2023. https://plm.sw.siemens.com/en-US/simcenter/systems-simulation/amesim/ (accessed June 21, 2024).

- PyPI. The Python Package Index (PyPI): pvlib 0.10.5 2023. https://pypi.org/project/pvlib/.

- Dubois-Iorgulescu A-M, Saraiva AKEB, Valle R, Rodrigues LM. How to define the system in social life cycle assessments? A critical review of the state of the art and identification of needed developments. Int J Life Cycle Assess 2018;23:507–18. [CrossRef]

- Ally J, Pryor T. Life-cycle assessment of diesel, natural gas and hydrogen fuel cell bus transportation systems. J Power Sources 2007;170:401–11. [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040. Environmental Management — Life Cycle Assessment — Principles and Framework, 2006.

- The International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT). Vision 2050: A strategy to decarbonize the global transport sector by mid-century. 2020.

- Energy Institute. 73rd Statistical Review of World Energy. 2024.

- Ribau JP, Silva CM, Sousa JMC. Efficiency, cost and life cycle CO2 optimization of fuel cell hybrid and plug-in hybrid urban buses. Appl Energy 2014. [CrossRef]

- Castillo H, Pitfield DE. ELASTIC – A methodological framework for identifying and selecting sustainable transport indicators. Transp Res D Transp Environ 2010;15:179–88. [CrossRef]

- Eufrásio A, Daniel J, Delgado O. Operational analysis of battery electric buses in São Paulo. 2023.

- IEA. Clean Energy Transitions Programme 2023. Paris: 2024.

- Carvalho L, Mingardo G, Van Haaren J. Green Urban Transport Policies and Cleantech Innovations: Evidence from Curitiba, Göteborg and Hamburg. European Planning Studies 2012;20:375–96. [CrossRef]

- Viornery-Portillo EA, Bravo-Díaz B, Mena-Cervantes VY. Life cycle assessment and emission analysis of waste cooking oil biodiesel blend and fossil diesel used in a power generator. Fuel 2020;281:118739. [CrossRef]

- Arteconi A, Brandoni C, Evangelista D, Polonara F. Life-cycle greenhouse gas analysis of LNG as a heavy vehicle fuel in Europe. Appl Energy 2010;87:2005–13. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz P, Franceschini EA, Levitan D, Rodriguez CR, Humana T, Correa Perelmuter G. Comparative analysis of cost, emissions and fuel consumption of diesel, natural gas, electric and hydrogen urban buses. Energy Convers Manag 2022;257:115412. [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak K, Pietrzak O. Environmental Effects of Electromobility in a Sustainable Urban Public Transport. Sustainability 2020;12:1052. [CrossRef]

- U.S Department of Energy. U.S. National Clean Hydrogen Strategy and Roadmap. 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).