Submitted:

19 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

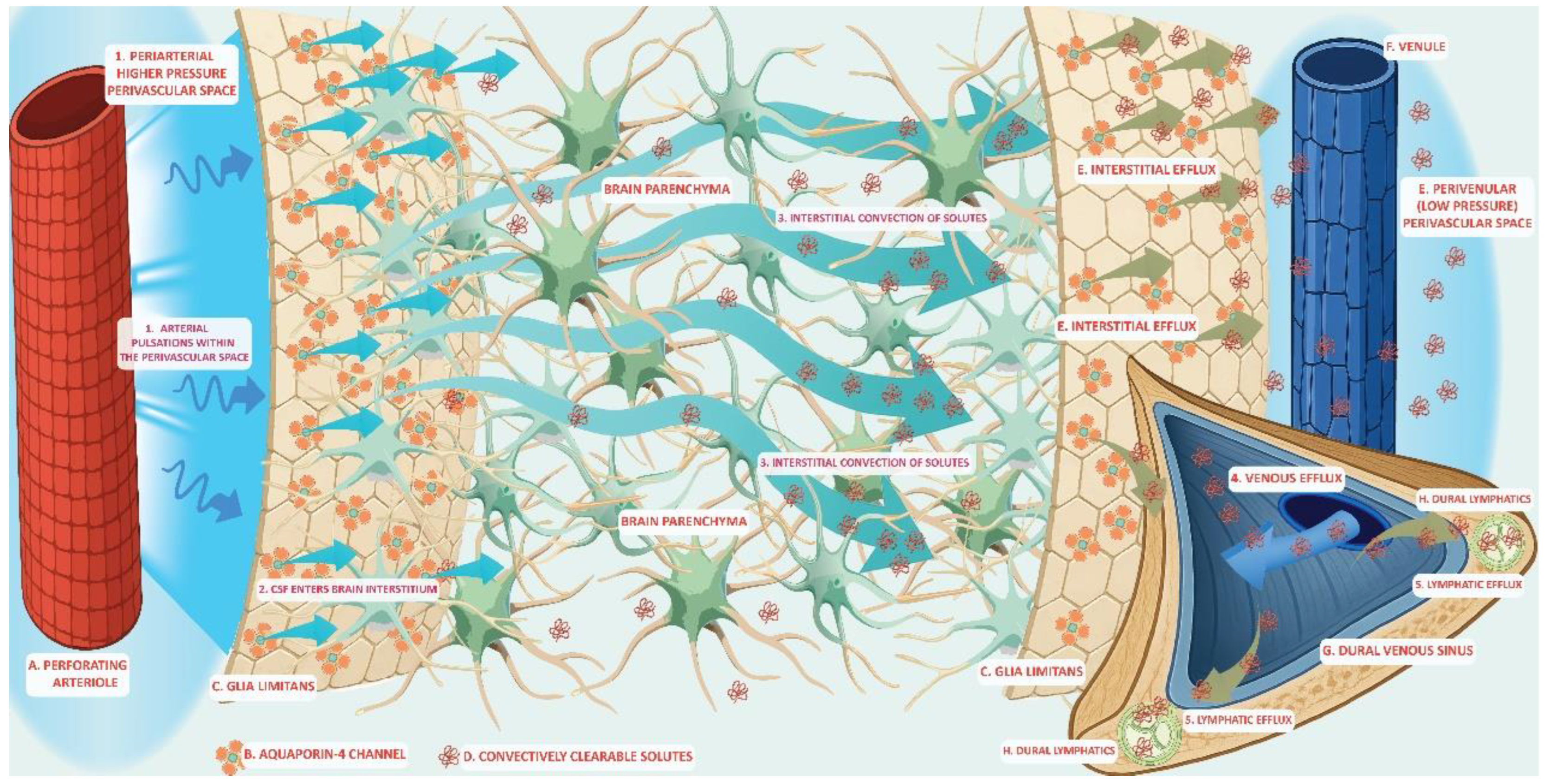

The glymphatic system is a fluid-transport framework in which cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) enters the brain along perivascular routes, exchanges with interstitial fluid (ISF), and exits toward venous, perineural, and meningeal lymphatic pathways enabling waste clearance. Recent studies have clarified the anatomical components that regulate solute movement. The perivascular astrocyte end feet, which is enriched in polarized aquaporin-4 (AQP4) expression, creates a high-permeability water interface that facilitates CSF–ISF exchange. Multiscale physical drivers such as cardiac pulsation, arteriolar vasomotion, and brain-state changes during sleep regulate timing and efficiency of the glymphatic transport. A broad spectrum of solutes is transported through this pathway, from small metabolites to extracellular proteins including amyloid-β and tau, as well as exogenous tracers and some lipid-associated species. Glymphatic redistribution may interface with other clearance systems including the brain-to-blood efflux via blood-brain barrier (BBB) transport, the intramural periarterial drainage (IPAD) that clears along vascular basement membranes and the meningeal lymphatic pathways that drain macromolecules to deep cervical lymph nodes. These different routes may be interconnected and represent a waste clearance network with complementary roles assigned to different mechanisms. Moreover, state dependence (notably sleep) and vascular health modulate glymphatic flux, offering plausible links between glymphatic system dysfunction to aging and neurodegeneration. Methodological advances—from intrathecal contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to in vivo two-photon imaging and tracer-kinetic modeling—have provided new insights into the anatomical scaffold and kinetics of the glymphatic system. Advances in glymphatic anatomy, together with growing evidence implicating glymphatic dysfunction in neurodegeneration, make a unifying framework urgently needed. Our synthesis spans glymphatic structure, fluid routing, the repertoire of transported solutes, and links to complementary clearance routes, supporting a unified model in which glymphatic clearance represents a core mechanism of cerebral homeostasis. Understanding glymphatic dysfunction may guide the establishment of diagnostic imaging biomarkers that have the potential to assist in therapeutic modulation of neurodegenerative diseases.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Glymphatic System

3. The Anatomy and Composition of the Glymphatic System

3.1. Perivascular Spaces (PVS)

3.2. Astrocytic Endfeet and AQP4 Water Channels

4. Process of Glymphatic Flow

5. Interaction of Waste Clearance Systems

6. Spectrum of Transported Solutes

7. Conclusions and Clinical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Aβ | amyloid-β |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| ApoE | apolipoprotein E |

| AQP4 | aquaporin-4 |

| BBB | blood-brain barrier |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| CSF | cerebrospinal fluid |

| IPAD | intramural periarterial drainage |

| ISF | interstitial fluid |

| LRP1 | lipoprotein receptor–related protein-1 |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| PVS | perivascular spaces |

References

- Shokri-Kojori, E; Wang, GJ; Wiers, CE; Demiral, SB; Guo, M; Kim, SW; et al. beta-Amyloid accumulation in the human brain after one night of sleep deprivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115(17), 4483–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raichle, ME; Gusnard, DA. Appraising the brain's energy budget. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002, 99(16), 10237–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, J; Fahmy, LM; Davoodi-Bojd, E; Zhang, L; Ding, G; Hu, J; et al. Waste Clearance in the Brain. Front Neuroanat. 2021, 15, 665803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, R; O'Donnell, J; Ding, F; Nedergaard, M. Interstitial ions: A key regulator of state-dependent neural activity? Prog Neurobiol 2020, 193, 101802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kamouh, MR; Lenck, S; Lehericy, S; Benveniste, H; Thomas, JL. Fluid and Waste Clearance in Central Nervous System Health and Diseases. Neurodegener Dis. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, R; Yoshida, K; Toda, M. Current understanding of lymphatic vessels in the central nervous system. Neurosurg Rev. 2020, 43(4), 1055–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, NA; Munk, AS; Lundgaard, I; Nedergaard, M. The Glymphatic System: A Beginner's Guide. Neurochem Res. 2015, 40(12), 2583–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennels, ML; Gregory, TF; Blaumanis, OR; Fujimoto, K; Grady, PA. Evidence for a 'paravascular' fluid circulation in the mammalian central nervous system, provided by the rapid distribution of tracer protein throughout the brain from the subarachnoid space. Brain Res. 1985, 326(1), 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliff, JJ; Wang, M; Liao, Y; Plogg, BA; Peng, W; Gundersen, GA; et al. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid beta. Sci Transl Med. 2012, 4(147), 147ra11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L; Kang, H; Xu, Q; Chen, MJ; Liao, Y; Thiyagarajan, M; et al. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science 2013, 342(6156), 373–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestre, H; Tithof, J; Du, T; Song, W; Peng, W; Sweeney, AM; et al. Flow of cerebrospinal fluid is driven by arterial pulsations and is reduced in hypertension. Nat Commun. 2018, 9(1), 4878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kedarasetti, RT; Drew, PJ; Costanzo, F. Arterial pulsations drive oscillatory flow of CSF but not directional pumping. Sci Rep. 2020, 10(1), 10102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L; Kress, BT; Weber, HJ; Thiyagarajan, M; Wang, B; Deane, R; et al. Evaluating glymphatic pathway function utilizing clinically relevant intrathecal infusion of CSF tracer. J Transl Med. 2013, 11, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliff, JJ; Lee, H; Yu, M; Feng, T; Logan, J; Nedergaard, M; et al. Brain-wide pathway for waste clearance captured by contrast-enhanced MRI. J Clin Invest. 2013, 123(3), 1299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringstad, G; Valnes, LM; Dale, AM; Pripp, AH; Vatnehol, SS; Emblem, KE; et al. Brain-wide glymphatic enhancement and clearance in humans assessed with MRI. JCI Insight 2018, 3(13). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eide, PK; Vatnehol, SAS; Emblem, KE; Ringstad, G. Magnetic resonance imaging provides evidence of glymphatic drainage from human brain to cervical lymph nodes. Sci Rep. 2018, 8(1), 7194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klostranec, JM; Vucevic, D; Bhatia, KD; Kortman, HGJ; Krings, T; Murphy, KP; et al. Current Concepts in Intracranial Interstitial Fluid Transport and the Glymphatic System: Part I-Anatomy and Physiology. Radiology 2021, 301(3), 502–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringstad, G; Eide, PK. Cerebrospinal fluid tracer efflux to parasagittal dura in humans. Nat Commun. 2020, 11(1), 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louveau, A; Smirnov, I; Keyes, TJ; Eccles, JD; Rouhani, SJ; Peske, JD; et al. Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels. Nature 2015, 523(7560), 337–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troili, F; Cipollini, V; Moci, M; Morena, E; Palotai, M; Rinaldi, V; et al. Perivascular Unit: This Must Be the Place. The Anatomical Crossroad Between the Immune, Vascular and Nervous System. Front Neuroanat. 2020, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y; Wang, M; Luan, M; Song, X; Wang, Y; Xu, L; et al. Enlarged Perivascular Spaces and Age-Related Clinical Diseases. Clin Interv Aging 2023, 18, 855–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barisano, G; Lynch, KM; Sibilia, F; Lan, H; Shih, NC; Sepehrband, F; et al. Imaging perivascular space structure and function using brain MRI. Neuroimage 2022, 257, 119329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bojarskaite, L; Nafari, S; Ravnanger, AK; Frey, MM; Skauli, N; Abjorsbraten, KS; et al. Role of aquaporin-4 polarization in extracellular solute clearance. Fluids Barriers CNS 2024, 21(1), 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdul Hamid, H; Hambali, A; Okon, U; Che Mohd Nassir, CMN; Mehat, MZ; Norazit, A; et al. Is cerebral small vessel disease a central nervous system interstitial fluidopathy? IBRO Neurosci Rep. 2024, 16, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z; Fan, X; Zhang, Y; Yao, M; Wang, G; Dong, Y; et al. The glymphatic system: a new perspective on brain diseases. Front Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1179988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louveau, A; Herz, J; Alme, MN; Salvador, AF; Dong, MQ; Viar, KE; et al. CNS lymphatic drainage and neuroinflammation are regulated by meningeal lymphatic vasculature. Nat Neurosci. 2018, 21(10), 1380–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melloni, A; Liu, L; Kashinath, V; Abdi, R; Shah, K. Meningeal lymphatics and their role in CNS disorder treatment: moving past misconceptions. Front Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1184049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menze, I; Bernal, J; Kaya, P; Aki, C; Pfister, M; Geisendorfer, J; et al. Perivascular space enlargement accelerates in ageing and Alzheimer's disease pathology: evidence from a three-year longitudinal multicentre study. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2024, 16(1), 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, J; Sinclair, B; Schwartz, DL; Silbert, LC; O'Brien, TJ; Law, M; et al. Perivascular spaces as a marker of disease severity and neurodegeneration in patients with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Front Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1003522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardlaw, JM; Benveniste, H; Nedergaard, M; Zlokovic, BV; Mestre, H; Lee, H; et al. Perivascular spaces in the brain: anatomy, physiology and pathology. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020, 16(3), 137–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhratsky, A; Pivoriunas, A. Astroglia support, regulate and reinforce brain barriers. Neurobiol Dis. 2023, 179, 106054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salman, MM; Kitchen, P; Halsey, A; Wang, MX; Tornroth-Horsefield, S; Conner, AC; et al. Emerging roles for dynamic aquaporin-4 subcellular relocalization in CNS water homeostasis. Brain 2022, 145(1), 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mestre, H; Hablitz, LM; Xavier, AL; Feng, W; Zou, W; Pu, T; et al. Aquaporin-4-dependent glymphatic solute transport in the rodent brain. Elife 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagelhus, EA; Ottersen, OP. Physiological roles of aquaporin-4 in brain. Physiol Rev. 2013, 93(4), 1543–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, DM; Wells, JA; Ma, D; Wallis, L; Park, D; Llewellyn, SK; et al. Glymphatic inhibition exacerbates tau propagation in an Alzheimer's disease model. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2024, 16(1), 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, TJ; Keil, SA; Han, W; Wang, MX; Iliff, JJ. The effect of aquaporin-4 mis-localization on Abeta deposition in mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2023, 181, 106100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H; Lin, L; Wu, T; Wu, C; Zhou, L; Li, G; et al. Phosphorylation of AQP4 by LRRK2 R1441G impairs glymphatic clearance of IFNgamma and aggravates dopaminergic neurodegeneration. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2024, 10(1), 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y; Yu, Q; Zhi, H; Peng, H; Xie, M; Li, R; et al. Advances in the study of the glymphatic system and aging. CNS Neurosci Ther 2024, 30(6), e14803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogensen, FL; Delle, C; Nedergaard, M. The Glymphatic System (En)during Inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22(14). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapshina, KV; Ekimova, IV. Aquaporin-4 and Parkinson's Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, IF; Ismail, O; Machhada, A; Colgan, N; Ohene, Y; Nahavandi, P; et al. Impaired glymphatic function and clearance of tau in an Alzheimer's disease model. Brain 2020, 143(8), 2576–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z; Xiao, N; Chen, Y; Huang, H; Marshall, C; Gao, J; et al. Deletion of aquaporin-4 in APP/PS1 mice exacerbates brain Abeta accumulation and memory deficits. Mol Neurodegener 2015, 10, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iliff, JJ; Chen, MJ; Plog, BA; Zeppenfeld, DM; Soltero, M; Yang, L; et al. Impairment of glymphatic pathway function promotes tau pathology after traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci. 2014, 34(49), 16180–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y; Zhang, C; He, XZ; Li, ZH; Meng, JC; Mao, RT; et al. Interaction Between the Glymphatic System and alpha-Synuclein in Parkinson's Disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2023, 60(4), 2209–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lun, MP; Monuki, ES; Lehtinen, MK. Development and functions of the choroid plexus-cerebrospinal fluid system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015, 16(8), 445–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichmann, TO; Damkier, HH; Pedersen, M. A Brief Overview of the Cerebrospinal Fluid System and Its Implications for Brain and Spinal Cord Diseases. Front Hum Neurosci. 2021, 15, 737217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacAulay, N; Toft-Bertelsen, TL. Dual function of the choroid plexus: Cerebrospinal fluid production and control of brain ion homeostasis. Cell Calcium 2023, 116, 102797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olstad, EW; Ringers, C; Hansen, JN; Wens, A; Brandt, C; Wachten, D; et al. Ciliary Beating Compartmentalizes Cerebrospinal Fluid Flow in the Brain and Regulates Ventricular Development. Curr Biol. 2019, 29(2), 229–41 e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J; Hua, Y; Xi, G; Keep, RF. Mechanisms of cerebrospinal fluid and brain interstitial fluid production. Neurobiol Dis. 2023, 183, 106159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y; Hayakawa, Y; Kamagata, K; Kikuta, J; Mita, T; Andica, C; et al. Glymphatic system impairment in sleep disruption: diffusion tensor image analysis along the perivascular space (DTI-ALPS). Jpn J Radiol 2023, 41(12), 1335–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreha-Kulaczewski, S; Joseph, AA; Merboldt, KD; Ludwig, HC; Gartner, J; Frahm, J. Inspiration is the major regulator of human CSF flow. J Neurosci. 2015, 35(6), 2485–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veluw, SJ; Hou, SS; Calvo-Rodriguez, M; Arbel-Ornath, M; Snyder, AC; Frosch, MP; et al. Vasomotion as a Driving Force for Paravascular Clearance in the Awake Mouse Brain. Neuron 2020, 105(3), 549–61 e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fultz, NE; Bonmassar, G; Setsompop, K; Stickgold, RA; Rosen, BR; Polimeni, JR; et al. Coupled electrophysiological, hemodynamic, and cerebrospinal fluid oscillations in human sleep. Science 2019, 366(6465), 628–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauglund, NL; Andersen, M; Tokarska, K; Radovanovic, T; Kjaerby, C; Sorensen, FL; et al. Norepinephrine-mediated slow vasomotion drives glymphatic clearance during sleep. Cell. 2025, 188(3), 606–22 e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, DD; Yang, G; Huang, YL; Zhang, T; Sui, AR; Li, N; et al. AQP4-A25Q Point Mutation in Mice Depolymerizes Orthogonal Arrays of Particles and Decreases Polarized Expression of AQP4 Protein in Astrocytic Endfeet at the Blood-Brain Barrier. J Neurosci. 2022, 42(43), 8169–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achariyar, TM; Li, B; Peng, W; Verghese, PB; Shi, Y; McConnell, E; et al. Erratum to: Glymphatic distribution of CSF-derived apoE into brain is isoform specific and suppressed during sleep deprivation. Mol Neurodegener. 2017, 12(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspelund, A; Antila, S; Proulx, ST; Karlsen, TV; Karaman, S; Detmar, M; et al. A dural lymphatic vascular system that drains brain interstitial fluid and macromolecules. J Exp Med. 2015, 212(7), 991–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayram, MS; Smith, G; Tufan, F; Tuna, IS; Bostanciklioglu, M; Zile, M; et al. Non-invasive MR imaging of human brain lymphatic networks with connections to cervical lymph nodes. Nat Commun. 2022, 13(1), 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, BT; Iliff, JJ; Xia, M; Wang, M; Wei, HS; Zeppenfeld, D; et al. Impairment of paravascular clearance pathways in the aging brain. Ann Neurol. 2014, 76(6), 845–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, JH; Cho, H; Kim, JH; Kim, SH; Ham, JS; Park, I; et al. Meningeal lymphatic vessels at the skull base drain cerebrospinal fluid. Nature 2019, 572(7767), 62–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheggen, ICM; Van Boxtel, MPJ; Verhey, FRJ; Jansen, JFA; Backes, WH. Interaction between blood-brain barrier and glymphatic system in solute clearance. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018, 90, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manu, DR; Slevin, M; Barcutean, L; Forro, T; Boghitoiu, T; Balasa, R. Astrocyte Involvement in Blood-Brain Barrier Function: A Critical Update Highlighting Novel, Complex, Neurovascular Interactions. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24(24). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storck, SE; Meister, S; Nahrath, J; Meissner, JN; Schubert, N; Di Spiezio, A; et al. Endothelial LRP1 transports amyloid-beta(1-42) across the blood-brain barrier. J Clin Invest. 2016, 126(1), 123–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirrito, JR; Deane, R; Fagan, AM; Spinner, ML; Parsadanian, M; Finn, MB; et al. P-glycoprotein deficiency at the blood-brain barrier increases amyloid-beta deposition in an Alzheimer disease mouse model. J Clin Invest. 2005, 115(11), 3285–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, OC; van der Werf, YD. The Sleeping Brain: Harnessing the Power of the Glymphatic System through Lifestyle Choices. Brain Sci. 2020, 10(11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasoff-Conway, JM; Carare, RO; Osorio, RS; Glodzik, L; Butler, T; Fieremans, E; et al. Clearance systems in the brain-implications for Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015, 11(8), 457–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldea, R; Weller, RO; Wilcock, DM; Carare, RO; Richardson, G. Cerebrovascular Smooth Muscle Cells as the Drivers of Intramural Periarterial Drainage of the Brain. Front Aging Neurosci 2019, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carare, RO; Bernardes-Silva, M; Newman, TA; Page, AM; Nicoll, JA; Perry, VH; et al. Solutes, but not cells, drain from the brain parenchyma along basement membranes of capillaries and arteries: significance for cerebral amyloid angiopathy and neuroimmunology. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2008, 34(2), 131–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, AW; Sharp, MM; Albargothy, NJ; Fernandes, R; Hawkes, CA; Verma, A; et al. Vascular basement membranes as pathways for the passage of fluid into and out of the brain. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131(5), 725–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y; Liu, E; Pei, Y; Yao, Q; Ma, H; Mu, Y; et al. The impairment of intramural periarterial drainage in brain after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2022, 10(1), 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, AWK; Abdelmonem, A; Taheri, MR. Arachnoid granulations: Dynamic nature and review. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol 2025, 54(2), 265–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, T; Leurgans, SE; Mehta, RI; Yang, J; Galloway, CA; de Mesy Bentley, KL; et al. Arachnoid granulations are lymphatic conduits that communicate with bone marrow and dura-arachnoid stroma. J Exp Med. 2023, 220(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proulx, ST. Cerebrospinal fluid outflow: a review of the historical and contemporary evidence for arachnoid villi, perineural routes, and dural lymphatics. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021, 78(6), 2429–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwata, N; Tsubuki, S; Takaki, Y; Shirotani, K; Lu, B; Gerard, NP; et al. Metabolic regulation of brain Abeta by neprilysin. Science 2001, 292(5521), 1550–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marr, RA; Rockenstein, E; Mukherjee, A; Kindy, MS; Hersh, LB; Gage, FH; et al. Neprilysin gene transfer reduces human amyloid pathology in transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2003, 23(6), 1992–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farris, W; Mansourian, S; Chang, Y; Lindsley, L; Eckman, EA; Frosch, MP; et al. Insulin-degrading enzyme regulates the levels of insulin, amyloid beta-protein, and the beta-amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100(7), 4162–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquet, RG; Gonzalez Ibanez, F; Picard, K; Funes, L; Khakpour, M; Gouras, GK; et al. Microglia degrade Alzheimer's amyloid-beta deposits extracellularly via digestive exophagy. Cell Rep. 2024, 43(12), 115052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoya, M; Takata, F; Iwao, T; Matsumoto, J; Tanaka, Y; Aridome, H; et al. alpha-Synuclein Degradation in Brain Pericytes Is Mediated via Akt, ERK, and p38 MAPK Signaling Pathways. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgaard, I; Lu, ML; Yang, E; Peng, W; Mestre, H; Hitomi, E; et al. Glymphatic clearance controls state-dependent changes in brain lactate concentration. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2017, 37(6), 2112–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgaard, I; Li, B; Xie, L; Kang, H; Sanggaard, S; Haswell, JD; et al. Direct neuronal glucose uptake heralds activity-dependent increases in cerebral metabolism. Nat Commun. 2015, 6, 6807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M; Wang, MX; Ismail, O; Braun, M; Schindler, AG; Reemmer, J; et al. Loss of perivascular aquaporin-4 localization impairs glymphatic exchange and promotes amyloid beta plaque formation in mice. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2022, 14(1), 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, K; Yamada, K; Nishiyama, R; Hashimoto, T; Nishida, I; Abe, Y; et al. Glymphatic system clears extracellular tau and protects from tau aggregation and neurodegeneration. J Exp Med. 2022, 219(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pla, V; Bork, P; Harnpramukkul, A; Olveda, G; Ladron-de-Guevara, A; Giannetto, MJ; et al. A real-time in vivo clearance assay for quantification of glymphatic efflux. Cell Rep. 2022, 40(11), 111320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fertan, E; Hung, C; Danial, JSH; Lam, JYL; Preman, P; Albertini, G; et al. Clearance of beta-amyloid and tau aggregates is size dependent and altered by an inflammatory challenge. Brain Commun. 2025, 7(1), fcae454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H; Wang, W; Zheng, X; Xia, D; Liu, H; Qin, C; et al. Decreased AQP4 Expression Aggravates a-Synuclein Pathology in Parkinson's Disease Mice, Possibly via Impaired Glymphatic Clearance. J Mol Neurosci. 2021, 71(12), 2500–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangroo Thrane, V; Thrane, AS; Plog, BA; Thiyagarajan, M; Iliff, JJ; Deane, R; et al. Paravascular microcirculation facilitates rapid lipid transport and astrocyte signaling in the brain. Sci Rep. 2013, 3, 2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, X; Liu, Z; Gan, Z; Yan, Q; Tong, L; Qiu, L; et al. Targeting the glymphatic system to promote alpha-synuclein clearance: a novel therapeutic strategy for Parkinson's disease. Neural Regen Res. 2026, 21(1), 233–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazic, A; Balint, V; Stanisavljevic Ninkovic, D; Peric, M; Stevanovic, M. Reactive and Senescent Astroglial Phenotypes as Hallmarks of Brain Pathologies. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G; Cao, Y; Tang, X; Huang, J; Cai, L; Zhou, L. The meningeal lymphatic vessels and the glymphatic system: Potential therapeutic targets in neurological disorders. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2022, 42(8), 1364–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louveau, A; Plog, BA; Antila, S; Alitalo, K; Nedergaard, M; Kipnis, J. Understanding the functions and relationships of the glymphatic system and meningeal lymphatics. J Clin Invest. 2017, 127(9), 3210–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohr, T; Hjorth, PG; Holst, SC; Hrabetova, S; Kiviniemi, V; Lilius, T; et al. The glymphatic system: Current understanding and modeling. iScience 2022, 25(9), 104987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munk, AS; Wang, W; Bechet, NB; Eltanahy, AM; Cheng, AX; Sigurdsson, B; et al. PDGF-B Is Required for Development of the Glymphatic System. Cell Rep. 2019, 26(11), 2955–69 e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayyappan, K; Unger, L; Kitchen, P; Bill, RM; Salman, MM. Measuring glymphatic function: Assessing the toolkit. Neural Regen Res. 2026, 21(2), 534–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paris, J; Angeli, E; Bousquet, G. The Pharmacology of Xenobiotics after Intracerebro Spinal Fluid Administration: Implications for the Treatment of Brain Tumors. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, ED; Kaur, J; Ding, G; Chopp, M; Jiang, Q. Clinical magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of glymphatic function. NMR Biomed. 2024, 37(8), e5132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).