Submitted:

21 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

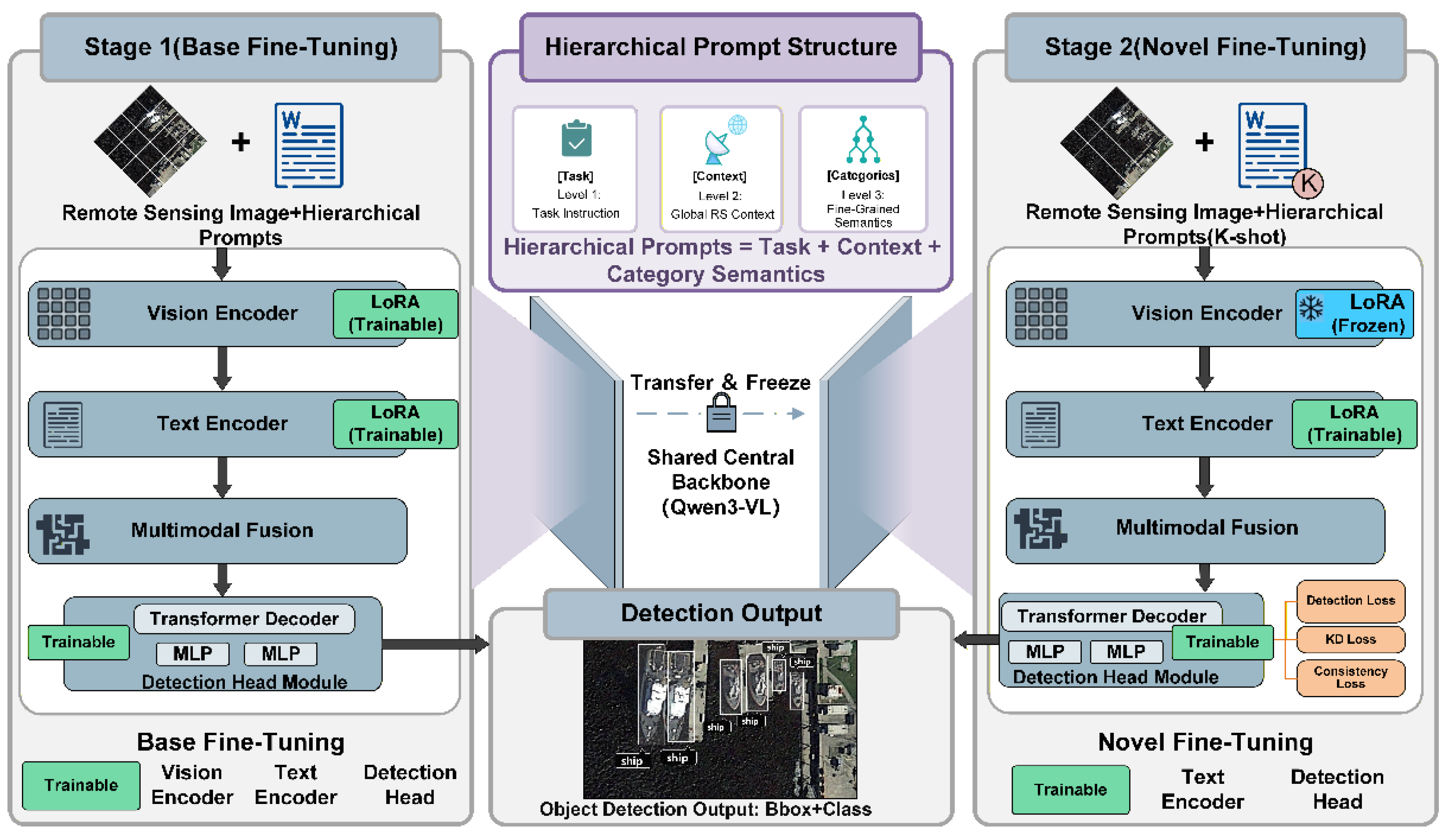

- We propose a novel LVLM-based framework for FSOD in RS imagery, which builds upon Qwen3-VL and employs parameter-efficient fine-tuning to adapt LVLMs to RS-FSOD under scarce annotations.

- We design a hierarchical prompting strategy that injects multi-level semantic priors—spanning task instructions, global RS context, and fine-grained category descriptions—into the detection pipeline, effectively compensating for limited visual supervision and mitigating confusion among visually similar categories.

- We develop a two-stage LoRA-based fine-tuning scheme that jointly optimizes vision and language branches on base classes and selectively adapts the text encoder and detection head for novel classes with distillation and semantic consistency constraints, thereby enhancing transferability to novel RS categories while mitigating catastrophic forgetting. Extensive experiments on DIOR and NWPU VHR-10.v2 demonstrate that the proposed method achieves competitive or superior performance compared with state-of-the-art FSOD approaches.

2. Related Work

2.1. Object Detection in Remote Sensing Imagery

2.2. Few-Shot Object Detection in Remote Sensing Imagery

3. Methods

3.1. Preliminary Knowledge

3.1.1. Problem Setting

- Base Training Phase: The model is trained on , which contains a large number of annotated instances for categories in .

- Fine-tuning Phase: The model is adapted using , which follows a -shot setting. For each category in , only annotated instances (e.g., ) are available.

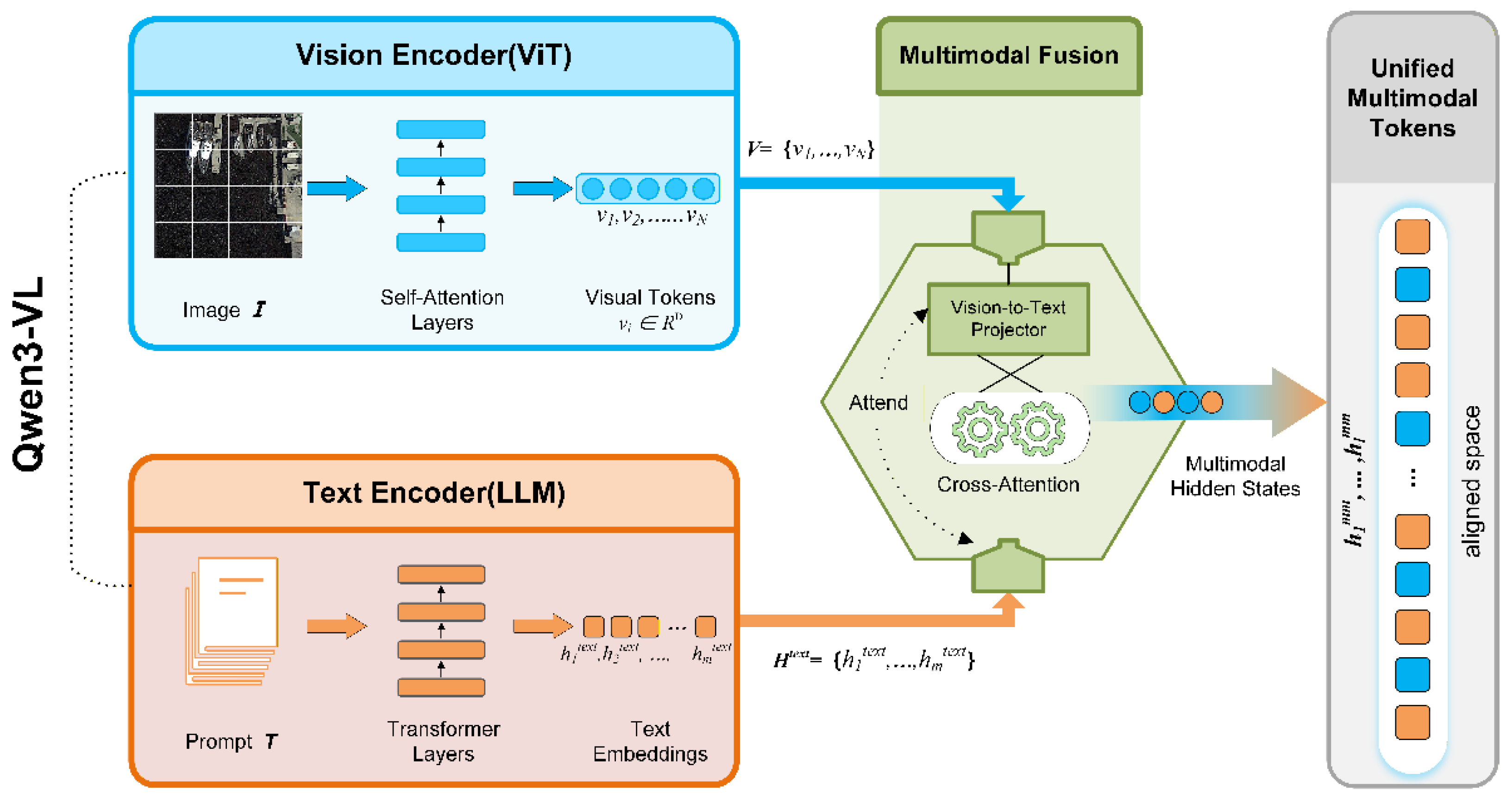

3.1.2. Base Model: Qwen3-VL

3.2. Overall Architecture

3.3. Hierarchical Prompting Mechanism

You are an expert in remote sensing object detection. Given an overhead image, detect all objects of interest and output their bounding boxes and category labels.

The image is an 800×800-pixel overhead view acquired by satellite or aerial sensors under varying ground sampling distances (approximately 0.5–30 m). Objects can be extremely multi-scale, densely packed, and arbitrarily oriented, with frequent background clutter, shadows, and repetitive textures. Scenes cover airports and airfields; expressways and highway facilities (service areas, toll stations, overpasses, bridges); ports and shorelines; large industrial zones (storage tanks, chimneys, windmills, dams); and urban or suburban districts with sports venues (baseball fields, basketball/tennis courts, golf courses, stadiums). Backgrounds can be cluttered and visually simi-lar, and discriminative cues often come from fine-grained shapes, markings, and spatial context.

- vehicle: Small man-made transport targets on roads/parking lots (cars, buses, trucks); compact rectangles with short shadows.

- expressway service area: Highway rest areas with large parking lots, gas pumps and service buildings; near ramps.

- expressway toll station: Toll plazas spanning multiple lanes with booths and canopies; strong lane markings at entries/exits.

- overpass: Elevated roadway segments crossing other roads/rails; ramps, pylons and cast shadows.

- bridge: Elevated linear structures spanning water or obstacles; approach ramps and structural shadows.

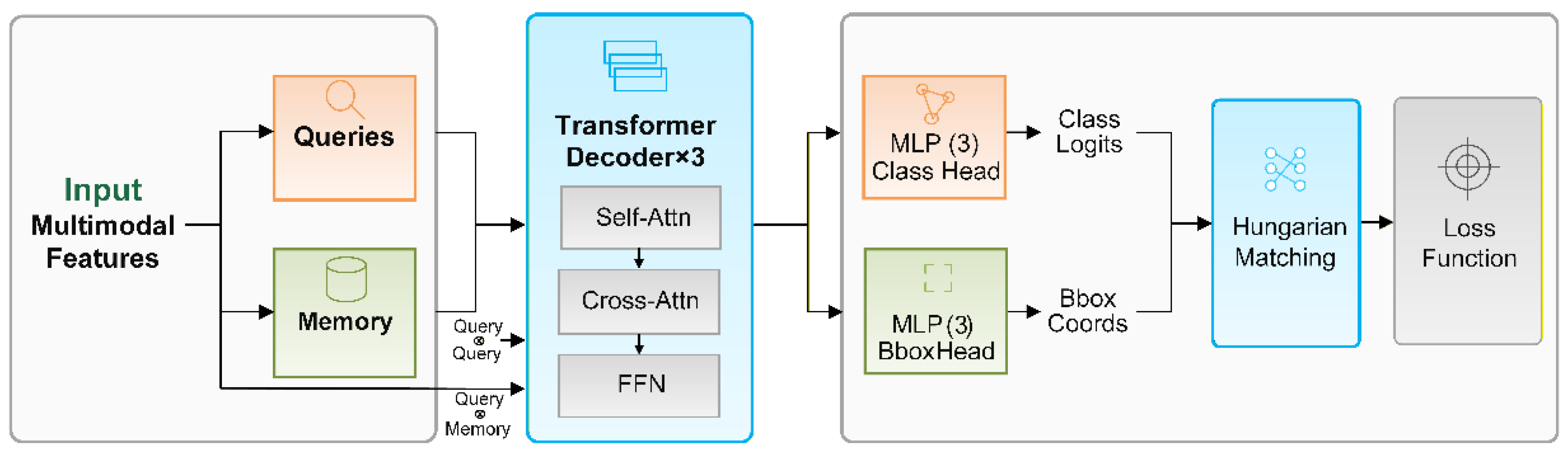

3.4. DETR-Style Detection Head

- A set of learnable object queries , which serve as input tokens to the decoder and are optimized jointly with the multimodal features , where denotes the hidden dimension.

- A Transformer decoder with layers that iteratively refines query representations through self-attention and cross-attention with the input multimodal features extracted from the vision-language encoder;

- Dual prediction heads that output class probabilities and bounding box coordinates in parallel. Specifically, for each query , the decoder produces an enhanced representation , which is subsequently fed into a three-layer multi-layer perceptron (MLP) for classification and a separate three-layer MLP for bounding box regression. The classification head predicts -dimensional logits (where for the DIOR dataset, with an additional background class), while the regression head outputs normalized bounding box parameters .

3.5. Two-Stage Fine-Tuning Strategy

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Datasets and Evaluation Metrics

4.1.1. Datasets

4.1.2. Evaluation Metrics

4.2. Implementation Details

4.2.1. Environment and Pretraining

4.2.2. Hyperparameters

4.2.3. Training Details

4.3. Main Results

4.3.1. Results on DIOR

4.3.2. Results on NWPU VHR-10.v2

4.4. Ablation Studies

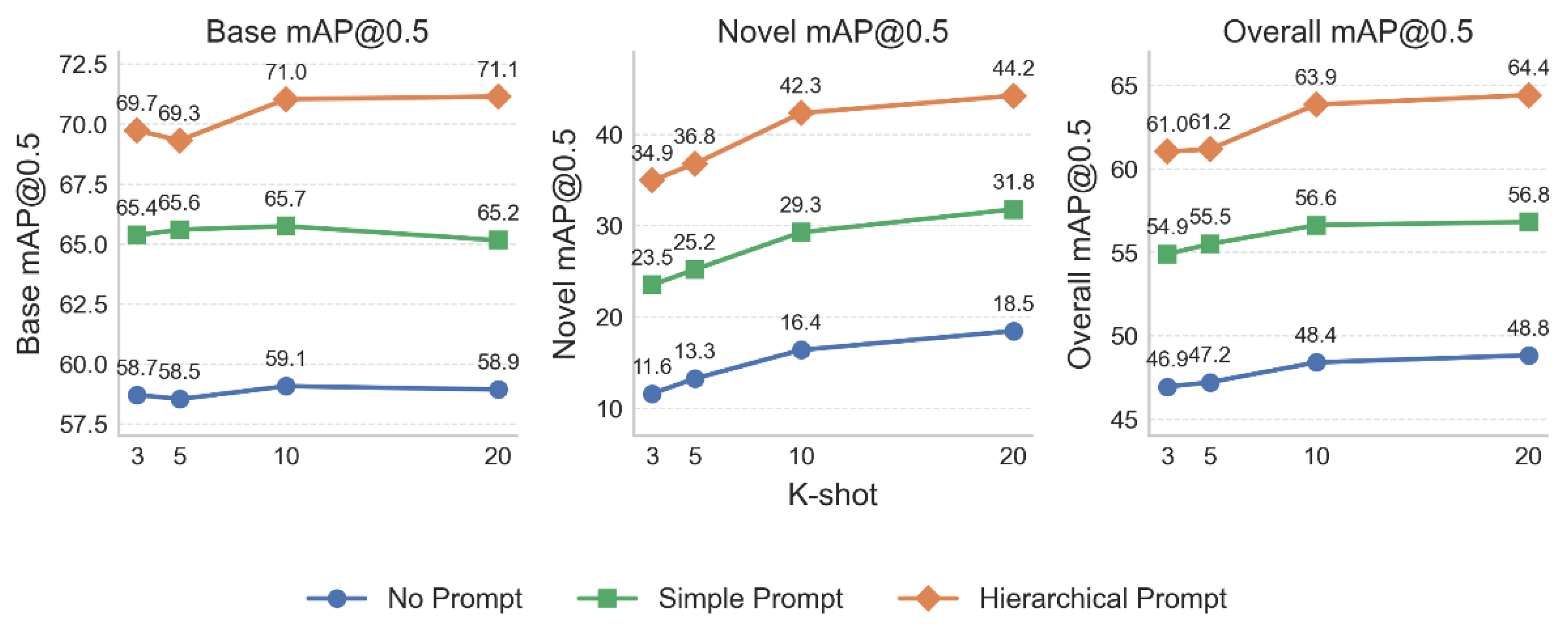

4.4.1. Effect of Hierarchical Prompting

4.4.2. Effect of Two-Stage Fine-Tuning Strategies

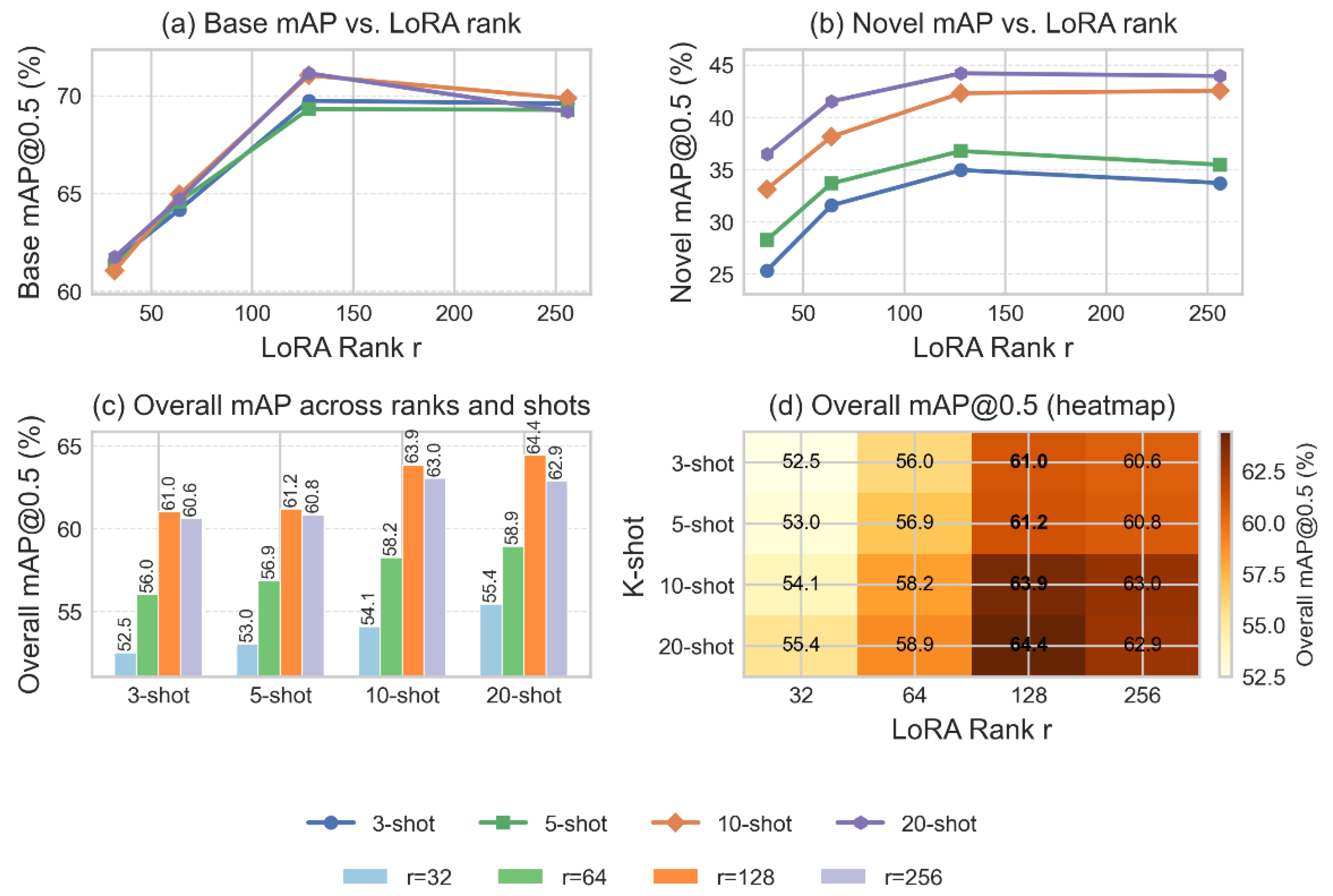

4.4.3. Effect of LoRA Rank

5. Discussion

5.1. Mechanism Analysis

5.2. Performance on Specific Classes

5.3. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RS | Remote sensing |

| FSOD | Few-shot object detection |

| RSOD | Remote sensing object detection |

| RS-FSOD | Remote sensing few-shot object detection |

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

| LVLM | Large vision-language model |

| LoRA | Low-rank adaptation |

| DETR | Detection Transformer |

| ViTs | Vision Transformers |

| RSAM | Remote sensing attention module |

| MLPs | Multilayer perceptrons |

| GIoU | Generalized Intersection over Union |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| mAP | Mean Average Precision |

| PEFT | Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning |

Appendix A. Hierarchical Prompting for the DIOR Dataset

Appendix B. Hierarchical Prompting for the NWPU VHR-10.v2 Dataset

References

- Sharifuzzaman, S.A.S.M.; Tanveer, J.; Chen, Y.; Chan, J.H.; Kim, H.S.; Kallu, K.D.; Ahmed, S. Bayes R-CNN: An Uncertainty-Aware Bayesian Approach to Object Detection in Remote Sensing Imagery for Enhanced Scene Interpretation. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2405. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Yan, B.; Shi, P.; Li, K.; Yao, X.; Guo, L.; Han, J. Prototype-CNN for Few-Shot Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tian, Y.; Xu, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Xiao, Y. MM-RCNN: Toward Few-Shot Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images With Meta Memory. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Xie, J.; Wang, Y.; Fu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, X. Optimized Data Distribution Learning for Enhancing Vision Transformer-Based Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. Photogramm. Rec. 2025, 40, e70004. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tian, P.; Song, R.; Xu, H.; Li, Y.; Du, Q. PCViT: A Pyramid Convolutional Vision Transformer Detector for Object Detection in Remote-Sensing Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Han, J.; Hou, X.; Zhou, D.; Liu, W.; Bi, F. FSDA-DETR: Few-Shot Domain-Adaptive Object Detection Transformer in Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, B.; Yuan, L. PR-Deformable DETR: DETR for Remote Sensing Object Detection. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Liang, K.; Zhang, W.; Li, F.; Jiang, Z.; Zuo, Z.; Tan, X. DETR-ORD: An Improved DETR Detector for Oriented Remote Sensing Object Detection with Feature Reconstruction and Dynamic Query. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3516. [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Shang, X.; Jia, S. Drone-DETR: Efficient Small Object Detection for Remote Sensing Image Using Enhanced RT-DETR Model. Sensors 2024, 24, 5496. [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Xu, Y.; Wang, H.; Wu, Z.; Wei, Z. Cde-Detr: A Real-Time End-to-End High-Resolution Remote Sensing Object Detection Method Based on Rt-Detr. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE INTERNATIONAL GEOSCIENCE AND REMOTE SENSING SYMPOSIUM (IGARSS 2024); IEEE: Athens, GREECE, 2024; pp. 8090–8094.

- Xu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wei, Z.; Zhan, T. Channel Self-Attention Based Multiscale Spatial-Frequency Domain Network for Oriented Object Detection in Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Bai, P.; Xia, Y.; Feng, J. Composite Perception and Multiscale Fusion Network for Arbitrary-Oriented Object Detection in Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Su, J.; Ju, Y.; Lam, K.-M.; Wang, Q. Efficient Inductive Vision Transformer for Oriented Object Detection in Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Sun, X.; Diao, W.; Zhao, L.; Fu, K.; Wang, H. FADA: Feature Aligned Domain Adaptive Object Detection in Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Pan, B.; Shi, Z. FIE-Net: Foreground Instance Enhancement Network for Domain Adaptation Object Detection in Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ji, Y.; Xu, H.; Cheng, K.; Song, R.; Du, Q. UAT: Exploring Latent Uncertainty for Semi-Supervised Object Detection in Remote-Sensing Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jiang, X.; Hu, Q.; Luo, H.; Zhong, S.; Tang, L.; Peng, J.; Fan, J. Enabling Near-Zero Cost Object Detection in Remote Sensing Imagery via Progressive Self-Training. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, T.E.; Darrell, T.; Gonzalez, J.E.; Yu, F. Frustratingly Simple Few-Shot Object Detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning; JMLR.org, July 13 2020; Vol. 119, pp. 9919–9928.

- Qiao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Z.; Qiu, X.; Wu, J.; Zhang, C. DeFRCN: Decoupled Faster R-CNN for Few-Shot Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); October 2021; pp. 8661–8670.

- Li, Y.; Hao, M.; Ma, J.; Temirbayev, A.; Li, Y.; Lu, S.; Shang, C.; Shen, Q. HPMF: Hypergraph-Guided Prototype Mining Framework for Few-Shot Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Mei, S.; Wang, Y.; Lian, J.; Han, Z.; Feng, Y. CAMCFormer: Cross-Attention and Multicorrelation Aided Transformer for Few-Shot Object Detection in Optical Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zou, X.; Yan, L.; Zhong, S.; Zhou, J. SNIDA: Unlocking Few-Shot Object Detection with Non-Linear Semantic Decoupling Augmentation. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Seattle, WA, USA, June 16 2024; pp. 12544–12553.

- Xie, J.; Wang, G.; Zhang, T.; Sun, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhuang, Y.; Li, J. LLaMA-Unidetector: An LLaMA-Based Universal Framework for Open-Vocabulary Object Detection in Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Pan, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, B. Multi-Modal Prototypes for Few-Shot Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4693. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Qin, J.; Zhan, T.; Wu, H.; Wei, Z.; Wu, Z. Few-Shot Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images via Dynamic Adversarial Contrastive-Driven Semantic-Visual Fusion. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Li, A.; Yang, B.; Zhang, B.; Hui, B.; Zheng, B.; Yu, B.; Gao, C.; Huang, C.; Lv, C.; et al. Qwen3 Technical Report 2025. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.09388. [CrossRef]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models 2021. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.09685. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Du, Q.; Wang, Q. ABNet: Adaptive Balanced Network for Multiscale Object Detection in Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Feng, H.; Zhao, T. Context Feature Integration and Balanced Sampling Strategy for Small Weak Object Detection in Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tian, P.; Song, R.; Xu, H.; Li, Y.; Du, Q. PCViT: A Pyramid Convolutional Vision Transformer Detector for Object Detection in Remote-Sensing Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lam, K.-M.; Wang, Q. CoF-Net: A Progressive Coarse-to-Fine Framework for Object Detection in Remote-Sensing Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Nautiyal, R.; Deshmukh, M. RS-TOD: Tiny Object Detection Model in Remote Sensing Imagery. Remote Sens. Appl.-Soc. Environ. 2025, 38, 101582. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, H. DCS-YOLOv8: A Lightweight Context-Aware Network for Small Object Detection in UAV Remote Sensing Imagery. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2989. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lei, J.; Xie, W.; Li, Y.; Yang, G.; Jia, X. Guided Hybrid Quantization for Object Detection in Remote Sensing Imagery via One-to-One Self-Teaching. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Long, T.; Zhang, Y.; Ribeiro, N.A.; Melgani, F. A Lightweight Normalization-Free Architecture for Object Detection in High-Spatial-Resolution Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 24491–24508. [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Li, Z. YOLOv8-SP: Ship Object Detection in Optical Remote Sensing Imagery. Mar. Geod. 2025, 48, 688–709. [CrossRef]

- Azeem, A.; Li, Z.; Siddique, A.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, D. Memory-Augmented Detection Transformer for Few-Shot Object Detection in Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Bian, M.; Fan, F.; Kuang, H.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, T.; Zhang, R. Vision-Language Guided Semantic Diffusion Sampling for Small Object Detection in Remote Sensing Imagery. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3203. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Deng, J.; Fang, Y. Few-Shot Object Detection on Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Qin, D.; Hou, D.; Zhang, J.; Deng, M.; Sun, G. Multiscale Object Contrastive Learning-Derived Few-Shot Object Detection in VHR Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; You, Y.; Liu, F. Discriminative Prototype Learning for Few-Shot Object Detection in Remote-Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhou, J.; Li, X.; Cao, Y.; Jin, G.; Zhang, X. InfRS: Incremental Few-Shot Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, P.; Jia, X.; Tang, X.; Jiao, L. Generalized Few-Shot Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 195, 353–364. [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Cheng, G.; Lang, C.; Huang, Z.; Han, J. Global-Integrated and Drift-Rectified Imprinting for Few-Shot Remote Sensing Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Guirguis, K.; Meier, J.; Eskandar, G.; Kayser, M.; Yang, B.; Beyerer, J. NIFF: Alleviating Forgetting in Generalized Few-Shot Object Detection via Neural Instance Feature Forging. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Vancouver, BC, Canada, June 2023; pp. 24193–24202.

- Chen, J.; Guo, Y.; Qin, D.; Zhu, J.; Gou, Z.; Sun, G. Multiscale Feature Knowledge Distillation and Implicit Object Discovery for Few-Shot Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Diao, W.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.; Sun, X.; Fu, K. Few-Shot Incremental Object Detection in Aerial Imagery via Dual-Frequency Prompt. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Xu, X.; Celik, T.; Gan, Z.; Li, H.-C. Transformation-Invariant Network for Few-Shot Object Detection in Remote-Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, S.; Huang, D.; Wang, Y. Multi-Scale Positive Sample Refinement for Few-Shot Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.09384. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, P.; Diao, W.; Yang, J.; Kong, L.; Wang, H.; Sun, X. Balancing Attention to Base and Novel Categories for Few-Shot Object Detection in Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Mei, S.; Wang, Y.; Lian, J.; Han, Z.; Chen, X. Few-Shot Object Detection With Multilevel Information Interaction for Optical Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yao, X.; Wang, X.; Hong, D.; Cheng, G.; Han, J. Robust Few-Shot Aerial Image Object Detection via Unbiased Proposals Filtration. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Pan, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, G.; Hu, Y.; Ye, Q. Few-Shot Object Detection in Remote-Sensing Images via Label-Consistent Classifier and Gradual Regression. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Wang, Q.; Feng, J.; Zhang, G.; Yin, J. Balanced Orthogonal Subspace Separation Detector for Few-Shot Object Detection in Aerial Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Shi, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Zhu, X.X. Few-Shot Object Detection in Remote Sensing: Lifting the Curse of Incompletely Annotated Novel Objects. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Hou, B.; Wu, Z.; Li, Z.; Guo, X.; Ren, B.; Jiao, L. Automatic Aug-Aware Contrastive Proposal Encoding for Few-Shot Object Detection of Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, W.; Cao, Y.; Cai, H.; Huang, T.; Xia, G.-S.; Li, X. Few-Shot Oriented Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images via Memorable Contrastive Learning. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Azeem, A.; Li, Z.; Siddique, A.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. Prototype-Guided Multilayer Alignment Network for Few-Shot Object Detection in Remote Sensing. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Huai, L.; Qiu, X.; Shangguan, Z.; Liu, T.; Fu, Y.; Van Gool, L.; Jiang, X. Cross-Domain Few-Shot Object Detection via Enhanced Open-Set Object Detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision – ECCV 2024; Leonardis, A., Ricci, E., Roth, S., Russakovsky, O., Sattler, T., Varol, G., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2025; pp. 247–264.

- Gao, Y.; Lin, K.-Y.; Yan, J.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, W.-S. AsyFOD: An Asymmetric Adaptation Paradigm for Few-Shot Domain Adaptive Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Vancouver, BC, Canada, June 2023; pp. 3261–3271.

- Liu, T.; Zhou, S.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Guan, J. Semantic Prototyping With CLIP for Few-Shot Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Jia, Y.; Han, H.; Li, Q.; Wang, Q. A Semantic-Guided Framework for Few-Shot Remote Sensing Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhuang, Y.; Wang, G.; Chen, H.; Wang, H.; Li, L.; Li, J. Controllable Generative Knowledge-Driven Few-Shot Object Detection From Optical Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, G.; Chen, H.; Bi, F. Advancing Controllable Diffusion Model for Few-Shot Object Detection in Optical Remote Sensing Imagery. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE INTERNATIONAL GEOSCIENCE AND REMOTE SENSING SYMPOSIUM (IGARSS 2024); IEEE: Athens, GREECE, 2024; pp. 7600–7603.

- Zhang, R.; Yang, B.; Xu, L.; Huang, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, Y. A Benchmark and Frequency Compression Method for Infrared Few-Shot Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ma, G.; Sui, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y. Few-Shot Object Detection in Remote Sensing Imagery via Fuse Context Dependencies and Global Features. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3462. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hong, Z.; Chen, X.; Li, Y. Few-Shot Object Detection for Remote Sensing Imagery Using Segmentation Assistance and Triplet Head. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3630. [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Gao, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.Q. Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning for Large Models: A Comprehensive Survey 2024. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.14608. [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wan, G.; Cheng, G.; Meng, L.; Han, J. Object Detection in Optical Remote Sensing Images: A Survey and a New Benchmark. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 159, 296–307. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Han, J.; Zhou, P.; Guo, L. Multi-Class Geospatial Object Detection and Geographic Image Classification Based on Collection of Part Detectors. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 98, 119–132. [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Chen, Z.; Xu, A.; Wang, X.; Liang, X.; Lin, L. Meta R-CNN: Towards General Solver for Instance-Level Low-Shot Learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); IEEE: Seoul, Korea (South), October 2019; pp. 9576–9585.

| Dataset | Split | Novel | Base | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIOR | 1 | Baseball field | Basketball court | Bridge | Chimney | Ship | others |

| 2 | Airplane | Airport | Expressway toll station | Harbor | Ground track field | others | |

| 3 | Dam | Golf course | Storage tank | Tennis court | Vehicle | others | |

| 4 | Express service area | Overpass | Stadium | Train station | Windmill | others | |

| Dataset | Split | Novel | Base | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NWPU VHR-10.v2 | 1 | Airplane | Baseball diamond | Tennis court | others |

| 2 | Basketball | Ground track field | Vehicle | others | |

| Split | Method | 3-shot | 5-shot | 10-shot | 20-shot | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | Novel | All | Base | Novel | All | Base | Novel | All | Base | Novel | All | ||

| 1 | Meta-RCNN [71] | 60.62 | 12.02 | 48.47 | 62.01 | 13.09 | 49.78 | 61.55 | 14.07 | 49.68 | 63.21 | 14.45 | 51.02 |

| P-CNN [2] | 47.00 | 18.00 | 39.80 | 48.40 | 22.80 | 42.00 | 50.90 | 27.60 | 45.10 | 52.20 | 29.60 | 46.80 | |

| G-FSDet [43] | 68.94 | 27.57 | 58.61 | 69.52 | 30.42 | 59.72 | 69.03 | 37.46 | 61.16 | 69.80 | 39.83 | 62.31 | |

| TPG-FSOD [61] | 62.70 | 34.20 | 55.58 | 62.70 | 35.60 | 55.93 | 64.40 | 40.20 | 58.35 | 65.50 | 43.00 | 59.88 | |

| RIFR [50] | 70.22 | 28.51 | 59.79 | 70.81 | 32.34 | 61.19 | 69.72 | 37.74 | 61.73 | 70.96 | 41.32 | 63.55 | |

| GIDR [44] | - | 33.80 | - | - | 35.90 | - | - | 40.10 | - | - | 43.80 | - | |

| Ours | 69.73 | 34.94 | 61.03 | 69.31 | 36.76 | 61.17 | 71.03 | 42.31 | 63.85 | 71.14 | 44.21 | 64.41 | |

| 2 | Meta-RCNN [71] | 62.55 | 8.84 | 49.12 | 63.14 | 10.88 | 50.07 | 63.28 | 14.90 | 51.18 | 63.86 | 16.71 | 52.07 |

| P-CNN [2] | 48.90 | 14.50 | 40.30 | 49.10 | 14.90 | 40.60 | 52.50 | 18.90 | 44.10 | 51.60 | 22.80 | 44.4 | |

| G-FSDet [43] | 69.20 | 14.13 | 55.43 | 69.25 | 15.84 | 55.87 | 68.71 | 20.70 | 56.70 | 68.18 | 22.69 | 56.86 | |

| TPG-FSOD [61] | 61.30 | 14.30 | 49.55 | 61.80 | 19.00 | 51.1 | 63.00 | 24.80 | 53.45 | 63.30 | 25.60 | 53.88 | |

| RIFR [50] | 70.83 | 15.11 | 56.90 | 71.11 | 18.75 | 58.02 | 70.77 | 21.93 | 58.56 | 71.70 | 24.10 | 59.80 | |

| GIDR [44] | - | 16.20 | - | - | 18.70 | - | - | 22.10 | - | - | 24.40 | - | |

| Ours | 71.63 | 19.31 | 58.55 | 70.05 | 21.55 | 57.93 | 70.14 | 25.68 | 59.03 | 71.89 | 27.24 | 60.73 | |

| 3 | Meta-RCNN [71] | 61.93 | 9.10 | 48.72 | 63.44 | 12.29 | 50.66 | 62.57 | 11.96 | 49.92 | 65.53 | 16.14 | 53.18 |

| P-CNN [2] | 49.50 | 16.50 | 41.30 | 49.90 | 18.80 | 42.10 | 52.10 | 23.30 | 44.90 | 53.10 | 28.80 | 47.00 | |

| G-FSDet [43] | 71.10 | 16.03 | 57.34 | 70.18 | 23.25 | 58.43 | 71.08 | 26.24 | 59.87 | 71.26 | 32.05 | 61.46 | |

| TPG-FSOD [61] | 65.60 | 20.10 | 54.23 | 65.10 | 23.10 | 54.60 | 66.40 | 28.90 | 57.03 | 65.90 | 32.60 | 57.58 | |

| RIFR [50] | 72.16 | 17.78 | 58.57 | 73.91 | 24.15 | 61.47 | 70.15 | 26.46 | 59.23 | 72.13 | 29.76 | 61.54 | |

| GIDR [44] | - | 19.80 | - | - | 25.40 | - | - | 28.70 | - | - | 32.40 | - | |

| Ours | 70.06 | 21.31 | 57.87 | 70.26 | 25.68 | 59.12 | 69.28 | 28.15 | 59.00 | 69.76 | 34.69 | 60.99 | |

| 4 | Meta-RCNN [71] | 61.73 | 13.94 | 49.78 | 62.60 | 15.84 | 50.91 | 62.23 | 15.07 | 50.44 | 63.24 | 18.17 | 51.98 |

| P-CNN [2] | 49.80 | 15.20 | 41.20 | 49.90 | 17.50 | 41.80 | 51.70 | 18.90 | 43.50 | 52.30 | 25.70 | 45.70 | |

| G-FSDet [43] | 69.01 | 16.74 | 55.95 | 67.96 | 21.03 | 56.30 | 68.55 | 25.84 | 57.87 | 67.73 | 31.78 | 58.75 | |

| TPG-FSOD [61] | 60.10 | 13.10 | 48.35 | 62.30 | 22.00 | 52.23 | 60.70 | 26.90 | 52.25 | 60.60 | 31.00 | 53.20 | |

| RIFR [50] | 69.10 | 18.22 | 56.38 | 69.05 | 22.87 | 57.51 | 69.22 | 28.49 | 59.03 | 68.78 | 32.12 | 59.62 | |

| GIDR [44] | - | 21.90 | - | - | 25.10 | - | - | 32.20 | - | - | 37.70 | - | |

| Ours | 69.95 | 21.68 | 57.88 | 70.79 | 23.77 | 59.04 | 70.58 | 30.62 | 60.59 | 70.24 | 35.21 | 61.48 | |

| Split | Method | 3-shot | 5-shot | 10-shot | 20-shot | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | Novel | All | Base | Novel | All | Base | Novel | All | Base | Novel | All | ||

| 1 | Meta-RCNN [71] | 87.00 | 20.51 | 67.05 | 85.74 | 21.77 | 66.55 | 87.01 | 26.98 | 69.00 | 87.29 | 28.24 | 69.57 |

| P-CNN [2] | 82.84 | 41.80 | 70.53 | 82.89 | 49.17 | 72.79 | 83.05 | 63.29 | 78.11 | 83.59 | 66.83 | 78.55 | |

| G-FSDet [43] | 89.11 | 49.05 | 77.01 | 88.37 | 56.10 | 78.64 | 88.40 | 71.82 | 83.43 | 89.73 | 75.41 | 85.44 | |

| TPG-FSOD [61] | 89.40 | 56.10 | 79.41 | 89.80 | 64.70 | 82.27 | 89.20 | 75.60 | 85.12 | 88.90 | 75.90 | 85.00 | |

| RIFR [50] | 94.64 | 53.17 | 82.20 | 95.26 | 62.39 | 85.40 | 96.23 | 72.29 | 89.04 | 95.38 | 79.46 | 90.61 | |

| GIDR [44] | - | 67.30 | - | - | 73.00 | - | - | 78.10 | - | - | 86.00 | - | |

| Ours | 96.67 | 67.51 | 87.92 | 96.84 | 69.49 | 88.64 | 96.54 | 75.63 | 90.27 | 96.61 | 86.74 | 93.65 | |

| 2 | Meta-RCNN [71] | 86.86 | 21.41 | 67.23 | 87.38 | 35.34 | 71.77 | 87.56 | 37.14 | 72.43 | 87.26 | 39.47 | 72.92 |

| P-CNN [2] | 81.03 | 39.32 | 68.52 | 81.18 | 46.10 | 70.70 | 80.93 | 55.90 | 73.41 | 81.21 | 58.37 | 75.50 | |

| G-FSDet [43] | 89.99 | 50.09 | 78.02 | 90.52 | 58.75 | 80.99 | 89.23 | 67.00 | 82.56 | 90.61 | 75.86 | 86.13 | |

| TPG-FSOD [61] | 90.10 | 48.70 | 77.68 | 89.80 | 63.50 | 81.91 | 89.30 | 69.40 | 83.33 | 90.20 | 75.90 | 85.91 | |

| RIFR [50] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| GIDR [44] | - | 50.90 | - | - | 58.50 | - | - | 68.30 | - | - | 76.40 | - | |

| Ours | 91.62 | 51.48 | 79.58 | 91.51 | 59.68 | 81.96 | 91.27 | 70.19 | 84.95 | 91.02 | 78.47 | 87.26 | |

| Split | Prompt | 3-shot | 5-shot | 10-shot | 20-shot | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | Novel | All | Base | Novel | All | Base | Novel | All | Base | Novel | All | ||

| 1 | No | 58.71 | 11.62 | 46.94 | 58.53 | 13.25 | 47.21 | 59.07 | 16.39 | 48.40 | 58.93 | 18.47 | 48.82 |

| Simple | 65.35 | 23.51 | 54.89 | 65.59 | 25.19 | 55.49 | 65.74 | 29.27 | 56.62 | 65.15 | 31.78 | 56.81 | |

| Hierarchical | 69.73 | 34.94 | 61.03 | 69.31 | 36.76 | 61.17 | 71.03 | 42.31 | 63.85 | 71.14 | 44.21 | 64.41 | |

| Split | Fine-Tuning Strategies | 3-shot | 5-shot | 10-shot | 20-shot | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | Novel | All | Base | Novel | All | Base | Novel | All | Base | Novel | All | ||

| 1 | Joint | 69.17 | 25.17 | 58.17 | 68.82 | 26.58 | 58.26 | 69.57 | 34.89 | 60.90 | 69.35 | 39.17 | 61.81 |

| Two-Stage | 69.73 | 34.94 | 61.03 | 69.31 | 36.76 | 61.17 | 71.03 | 42.31 | 63.85 | 71.14 | 44.21 | 64.41 | |

| Split | LoRA rank | 3-shot | 5-shot | 10-shot | 20-shot | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | Novel | All | Base | Novel | All | Base | Novel | All | Base | Novel | All | ||

| 1 | 32 | 61.54 | 25.32 | 52.49 | 61.29 | 28.25 | 53.03 | 61.05 | 33.12 | 54.07 | 61.74 | 36.46 | 55.42 |

| 64 | 64.17 | 31.56 | 56.02 | 64.59 | 33.67 | 56.86 | 64.94 | 38.14 | 58.24 | 64.72 | 41.52 | 58.92 | |

| 128 | 69.73 | 34.94 | 61.03 | 69.31 | 36.76 | 61.17 | 71.03 | 42.31 | 63.85 | 71.14 | 44.21 | 64.41 | |

| 256 | 69.59 | 33.71 | 60.62 | 69.27 | 35.46 | 60.82 | 69.86 | 42.53 | 63.03 | 69.17 | 43.95 | 62.87 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.